The Federal Budget: Overview and Issues for FY2018 and Beyond

The federal budget is a central component of the congressional “power of the purse.” Each fiscal year, Congress and the President engage in a number of practices that influence short- and long-run revenue and expenditure trends. This report offers context for the current budget debate and tracks legislative events related to the federal budget.

In recent years, policies enacted to decrease spending along with a stronger economy have led to reduced budget deficits. The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25) implemented several measures intended to reduce the deficit from FY2012 through FY2021. The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; P.L. 113-67), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74) increased the discretionary budget authority levels permitted under the BCA for FY2013 through FY2017. Various deficit reduction measures were included to offset the costs of the changes to spending levels in that legislation.

The BCA will continue to affect spending limits in FY2018 and beyond, and Congress may debate enacting further modifications. The annual appropriations process, the statutory debt limit, and “tax extenders” each may draw congressional attention in FY2018. Additionally, Congress may choose to debate structural changes to the federal tax system, including reforms proposed by the House Committee on Ways and Means and the Trump Administration. Though federal budget deficits have stabilized in recent years, they remain well above their historical average.

The Trump Administration released its FY2018 budget on May 23, 2017. Proposed policy changes in the budget included reductions in individual and corporate income tax rates, increases in discretionary defense spending, and large decreases in mandatory spending other than Social Security and Medicare (with the largest budgetary effects resulting from decreases in Medicaid spending) and in nondefense discretionary programs.

Following passage of full-year FY2017 appropriations, Congress has turned its attention to the FY2018 budget. The Budget Committees in the House and Senate each develop a budget resolution as they receive information and testimony from a number of sources, including the Administration, the Congressional Budget Office, and congressional committees with jurisdiction over spending and revenues.

Trends resulting from current federal fiscal policies are generally thought by economists to be unsustainable in the long term. Projections suggest that achieving a sustainable long-term trajectory for the federal budget would require deficit reduction. Reductions in deficits could be accomplished through revenue increases, spending reductions, or some combination of the two.

The Federal Budget: Overview and Issues for FY2018 and Beyond

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview

- Budget Cycle

- Budget Baseline Projections

- Spending and Revenue Trends

- Federal Spending

- Size of Federal Spending Components Relative to Each Other

- Federal Revenue

- Deficits, Debt, and Interest

- Budget Deficits

- Federal Debt and Debt Limit

- Net Interest

- Recent Budget Policy Legislation and Events

- Deficit Reduction Legislation: the Budget Control Act of 2011 and Later Amendments

- Tax Reform: the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 and Tax Extenders Legislation

- Appropriations and Debt Limit Legislation

- Budget for FY2018

- Trump Administration's FY2018 Budget

- Deficit Projections in the President's FY2018 Budget

- FY2018 Congressional Budget Activity

- Considerations for Congress

- Ongoing Budget Issues

- Long-Term Considerations

Figures

- Figure 1. Total Outlays and Revenues, FY1947-FY2016

- Figure 2. Outlays by Major Category, FY1947-FY2027

- Figure 3. Revenues by Major Category, FY1947-FY2027

- Figure 4. Budgetary Effects of Proposals in President's FY2018 Budget

- Figure 5. Budget Deficit Projections, FY2017-FY2027

- Figure 6. Discretionary Cap Changes in the FY2018 President's Budget Proposal

Tables

Appendixes

Summary

The federal budget is a central component of the congressional "power of the purse." Each fiscal year, Congress and the President engage in a number of practices that influence short- and long-run revenue and expenditure trends. This report offers context for the current budget debate and tracks legislative events related to the federal budget.

In recent years, policies enacted to decrease spending along with a stronger economy have led to reduced budget deficits. The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25) implemented several measures intended to reduce the deficit from FY2012 through FY2021. The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; P.L. 113-67), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74) increased the discretionary budget authority levels permitted under the BCA for FY2013 through FY2017. Various deficit reduction measures were included to offset the costs of the changes to spending levels in that legislation.

The BCA will continue to affect spending limits in FY2018 and beyond, and Congress may debate enacting further modifications. The annual appropriations process, the statutory debt limit, and "tax extenders" each may draw congressional attention in FY2018. Additionally, Congress may choose to debate structural changes to the federal tax system, including reforms proposed by the House Committee on Ways and Means and the Trump Administration. Though federal budget deficits have stabilized in recent years, they remain well above their historical average.

The Trump Administration released its FY2018 budget on May 23, 2017. Proposed policy changes in the budget included reductions in individual and corporate income tax rates, increases in discretionary defense spending, and large decreases in mandatory spending other than Social Security and Medicare (with the largest budgetary effects resulting from decreases in Medicaid spending) and in nondefense discretionary programs.

Following passage of full-year FY2017 appropriations, Congress has turned its attention to the FY2018 budget. The Budget Committees in the House and Senate each develop a budget resolution as they receive information and testimony from a number of sources, including the Administration, the Congressional Budget Office, and congressional committees with jurisdiction over spending and revenues.

Trends resulting from current federal fiscal policies are generally thought by economists to be unsustainable in the long term. Projections suggest that achieving a sustainable long-term trajectory for the federal budget would require deficit reduction. Reductions in deficits could be accomplished through revenue increases, spending reductions, or some combination of the two.

Federal budget decisions express the priorities of Congress and reinforce its influence on federal policies. Making budgetary decisions for the federal government is a complex process and requires the balance of competing goals.1 The recent economic recession adversely affected federal budget outcomes through revenue declines and spending increases. The federal budget recorded a deficit of 9.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) in FY2009, the largest value since World War II. Subsequent improvement of the economy and implementation of policies designed to lower spending have improved the short-term budget outlook. In FY2016, the federal budget recorded a deficit of 3.2% of GDP, which was still significantly higher than the average deficit since FY1947 (2.0% of GDP).

Over the next several years, projections of a continued decline in discretionary spending are more than offset by increases in both mandatory spending and net interest payments, leading to a rise in federal deficits. Increases in the long-term cost of federal retirement and health care programs and debt servicing costs each contribute to upward pressure on federal spending levels. Operating these programs in their current form may pass on substantial economic burdens to future generations. Congress and the President may consider proposals for deficit reduction if fiscal issues remain a key item on the legislative agenda.

This report summarizes issues surrounding the federal budget, examines policy changes relevant to the budget framework for FY2018, and discusses recent major policy proposals included in the President's FY2018 budget. It concludes by addressing major short- and long-term fiscal challenges facing the federal government.

Overview

Each fiscal year, Congress and the President engage in a number of practices that influence short- and long-run revenue and expenditure trends. This section describes the budget cycle and explains how budget baselines are constructed. Budget baselines are used to measure how legislative changes affect the budget outlook and are integral to evaluating these policy choices.

Budget Cycle2

Action on a given year's federal budget, from initial formation by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) until final audit, typically spans four calendar years.3 The executive agencies begin the budget process by compiling detailed budget requests, overseen by OMB. Agencies work on their budget requests in the calendar year before the budget submission, often during the spring and summer (about a year and a half before the fiscal year begins). The President usually submits the budget to Congress around the first Monday in February, or about eight months before the beginning of the fiscal year, although submissions are often later in the first year of an Administration.4

Congress typically begins formal consideration of a budget resolution once the President submits the budget request. The budget resolution is a plan, agreed to by the House and Senate, which establishes the framework for subsequent budgetary legislation. Because the budget resolution is a concurrent resolution, it is not sent to the President for approval.5 If the House of Representatives and Senate cannot agree on a budget resolution, a substitute measure known as a "deeming resolution" may be implemented by each chamber.6

House and Senate Appropriations Committees and their subcommittees usually begin reporting discretionary spending bills after the budget resolution is agreed upon. Appropriations Committees review agency funding requests and propose levels of budget authority (BA).7 Appropriations acts passed by Congress set the amount of BA available for specific programs and activities. Authorizing committees, which control mandatory spending, and committees with jurisdiction over revenues also play important roles in budget decision-making.8

During the fiscal year, Congress and OMB oversee the execution of the budget.9 Once the fiscal year ends on the following September 30, the Department of the Treasury and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) begin year-end audits.

Budget Baseline Projections

Budget baseline projections are used to project the future impact of current laws and measure the effect of future legislation on spending and revenues. They are not meant to predict future budget outcomes. Baseline projections are included in both the President's budget and the congressional budget resolution. It is important to understand the assumptions and components included in budget baselines. In some cases, slight changes in the underlying models or assumptions can lead to large effects on projected deficits, receipts, or expenditures.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) computes current-law baseline projections using assumptions set out in budget enforcement legislation.10 Since Congress and the President have resolved certain questions related to expiring tax policy and have enacted specific policies set to control discretionary spending over the next decade, there are fewer policy uncertainties affecting the baseline levels under current law. On the revenue side of the budget, the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240; see additional discussion below) permanently set into law many individual tax rates and tax policy provisions. On the spending side, baseline discretionary spending levels are largely constrained by the caps and automatic spending reductions enacted as part of the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25) and further modified by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; P.L. 113-67) and Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74).11

The CBO baseline also incorporates policy provisions in current law that have historically been revised before the subsequent policies actually take effect. Specifically, the CBO baseline assumes that discretionary budget authority from FY2018 through FY2021 will be restricted by the caps as created by the BCA, and that certain expiring tax provisions will not be extended.12 This leads to baseline projections of lower spending and higher revenue levels relative to what some consider likely based on previous policy actions.

In addition to these elements of current law, macroeconomic assumptions, including those related to GDP growth, inflation, and interest rates, will also affect the baseline estimates and projections. Minor changes in the economic or technical assumptions that are used to project the baseline also could result in significant changes in future deficit levels.13

CBO's current baseline projections, released in June 2017, show rising budget deficits over the next several years.14 Such a trend represents a reversal from the significant declines in inflation-adjusted deficits experienced in the past few fiscal years.15 Those declines were primarily due to continued increases in employment (which increased revenues collected from income and payroll taxes) and reductions in discretionary spending. While the baseline projections include continued declines in discretionary outlays, those reductions are more than offset by increases in mandatory spending, which are largely due to the rising cost of Social Security and Medicare programs.

Baseline projections also include increases in debt held by the public throughout the 10-year budget window. Debt held by the public finances budget deficits and federal loan activity, and is a function of three things: (1) the size of existing debt, (2) economic growth, and (3) interest rates.16 Debt held by the public increased in FY2016 for the eighth time in the last nine fiscal years. Debt held by the public was 77.0% of GDP at the end of FY2016, and is projected to be 91.2% of GDP at the end of FY2027.

|

FY2016 (actual) |

FY2017 |

FY2022 |

FY2027 |

|

|

Budget Deficit |

3.2 |

3.6 |

4.5 |

5.2 |

|

Debt Held by the Public |

77.0 |

76.7 |

82.9 |

91.2 |

Source: Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, January 2017, Table 1-1.

CBO also provides projections based on alternative policy assumptions, which illustrate levels of spending and revenue if current policies continue rather than expire as scheduled under current law. If discretionary spending caps established by the BCA are lifted and expiring tax provisions are extended, CBO projects an increase in the budget deficit of more than $1.0 trillion relative to the current-law baseline, exclusive of debt servicing costs, over the FY2018 to FY2027 period. Beyond the 10-year forecast window, federal deficits are expected to grow unless major policy changes are made. This is a result of increased outlays largely attributable to rising health care and retirement costs.

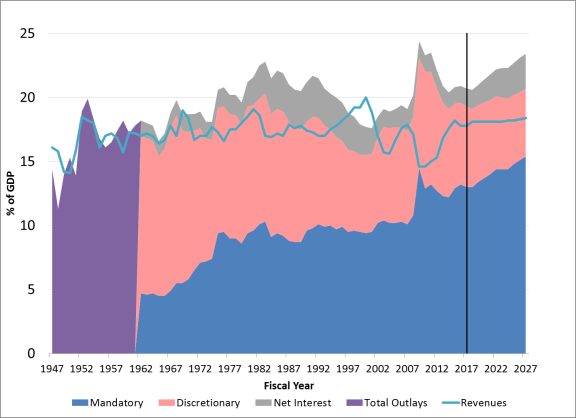

Spending and Revenue Trends

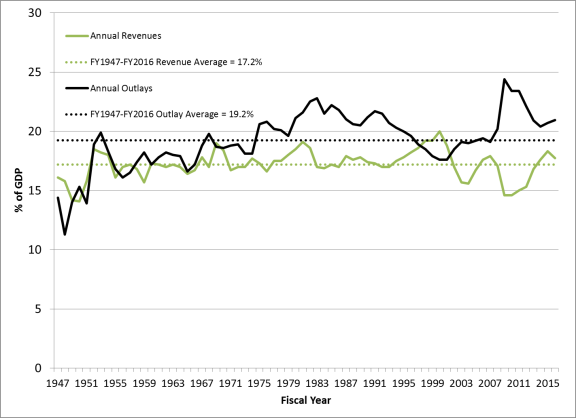

Over the last seven decades, federal spending has accounted for an average of 19.2% of the economy (as measured by GDP), while federal revenues averaged roughly 17.2% of GDP. Spending has exceeded revenues in each fiscal year since FY2002, resulting in annual budget deficits. Between FY2009 and FY2012, spending and revenue deviated significantly from historical averages, primarily as a result of the economic downturn and policies enacted in response to financial turmoil. In FY2016, the U.S. government spent $3.85 trillion and collected $3.27 trillion in revenue. The resulting deficit of $0.58 trillion, or 3.2% of GDP, was higher than the average deficit from FY1947 and FY2016 of 2.0% of GDP. The trends in revenues and outlays between FY1947 and FY2016 are shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1. Total Outlays and Revenues, FY1947-FY2016 (as a % of GDP) |

|

|

Source: Congressional Budget Office and Office of Management and Budget. CRS calculations. |

Federal Spending

Federal outlays are often divided into three categories: discretionary spending, mandatory spending, and net interest.17 Discretionary spending is controlled by the annual appropriations acts. Mandatory spending encompasses spending on entitlement programs and spending controlled by laws other than annual appropriations acts.18 Entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid make up the bulk of mandatory spending. Congress sets eligibility requirements and benefits for entitlement programs, rather than appropriating a fixed sum each year. Therefore, if the eligibility requirements are met for a specific mandatory program, outlays are made without further congressional action. Net interest comprises the government's interest payments on the debt held by the public, offset by small amounts of interest income the government receives from certain loans and investments.19

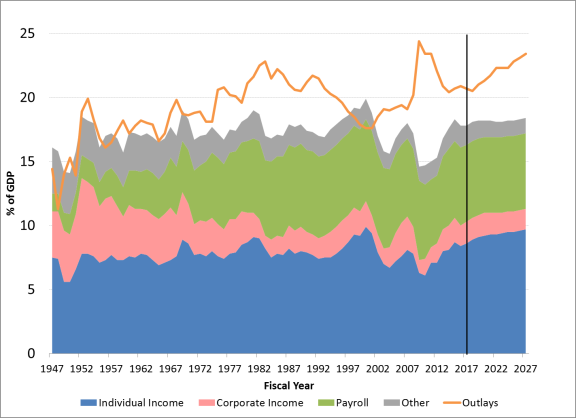

Federal Spending Relative to the Size of the Economy (GDP)

In FY2000, total outlays equaled 17.6% of GDP, the lowest recorded level since FY1966. In FY2009, outlays peaked at 24.4% of GDP. Outlays then fell steadily for the next few years, equaling 20.3% of GDP in FY2014, before rising to 20.9% of GDP in FY2016. Under the CBO baseline, total outlays are projected to continue rising and will reach 23.6% of GDP in FY2027. Figure 2 provides historical data and CBO projections of federal spending between FY1947 and FY2027.

When the modern definitions of discretionary and mandatory spending were created in FY1962, discretionary spending was consistently the largest source of federal outlays, peaking at 13.1% of GDP in FY1968. In the ensuing decades discretionary spending as a share of the economy underwent a gradual decline, and totaled 6.1% of GDP in FY2000. Discretionary spending increased in most years between FY2000 and FY2010, largely as a result of increases in security spending20 and federal interventions designed to stimulate the economy. Discretionary spending peaked in FY2010 at 9.1% of GDP. Since FY2010, discretionary spending has fallen, due to both the wind down of stimulus programs and the implementation of restrictions established by the BCA. In FY2016, discretionary spending totaled 6.4% of GDP. Baseline projections show continuing declines through the 10-year budget window. By FY2021, discretionary spending is projected to fall to 5.9% of GDP, which would be its lowest level ever; discretionary spending is projected to total 5.4% of GDP by FY2027. The projected decline in discretionary spending in the baseline over the next decade is largely due to the reductions under current law contained in the BCA.21

Figure 2 also shows mandatory spending as a share of GDP. Mandatory spending was a much smaller source of outlays than discretionary spending in earlier years, totaling just 4.7% of GDP in FY1962. Over time the share of mandatory spending has consistently grown, initially due to the increase in subscription in large mandatory programs such as Social Security and Medicare and then due to demographic and economic shifts that further increased the sizes of those programs. Mandatory spending totaled 13.2% of GDP in FY2016, up from 9.4% of GDP in FY2000. Mandatory spending peaked in FY2009 at 14.5% of GDP. Mandatory spending levels during the FY2009-FY2012 period were elevated mainly because of increases in outlays for income security programs as a result of the recession. The continuing economic recovery has resulted in lower mandatory spending on certain programs. However, mandatory spending is projected to continue its upward trend towards the end of the budget window due to growth in certain entitlement programs. As a result, under current law, CBO projects that mandatory spending will total 15.4% of GDP in FY2027, greater than the FY2009 level.

Size of Federal Spending Components Relative to Each Other

It is also possible to evaluate trends in the share of total spending devoted to each component. In FY2016, mandatory spending amounted to 63.0% of total outlays, discretionary spending reached 30.8% of total outlays, and net interest comprised 6.2% of total outlays. The largest mandatory programs, Social Security, Medicare, and the federal share of Medicaid, constituted 48.4% of all federal spending in FY2016. By FY2027, mandatory and net interest spending are projected to increase, while the share of outlays devoted to discretionary spending is projected to decline. Mandatory spending is projected to rise to 65.0% of total outlays while discretionary spending's share is projected to fall to 22.7% in that year. Net interest spending is projected to rise to 12.4% of total outlays in FY2027.

Discretionary spending currently represents less than one-third of total federal outlays. Some budget experts contend that to achieve significant reductions in federal spending, reductions in mandatory spending are needed.22 Budget and social policy experts have also stated that cuts in mandatory spending may cause substantial disruption to many households, because mandatory spending comprises important parts of the social safety net.23 Even though the budget deficit has recently been declining, future projections of increasing deficits and resulting high debt levels may warrant further action to address fiscal health over the long term.24

Federal Revenue

In FY2016, federal revenue collections totaled 17.8% of GDP, higher than the historical average since FY1947 (17.2% of GDP). Real federal revenues have increased in recent years, due primarily to an improving economy. Between FY2009 and FY2013, revenue collection was depressed as the result of the economic downturn and certain tax relief provisions. In FY2009 and FY2010, revenue collections totaled 14.6% of GDP.

ATRA (P.L. 112-240) increased the certainty of the revenue outlook. ATRA permanently extended reduced tax rates for most income groups, while raising tax rates for upper-income households beginning in calendar year 2013.25 Revenues are projected to total 18.4% of GDP in FY2027 under the CBO baseline.

Figure 3 shows revenue collections between FY1947 and FY2027, as projected in the CBO baseline. Individual income taxes have long been the largest source of federal revenues, followed by social insurance (payroll) and corporate income taxes.26 In FY2016, individual income tax revenues totaled 8.4% of GDP. While individual income taxes as a share of the economy have remained relatively constant since the end of World War II, the share of federal revenues devoted to social insurance programs has increased from 1.4% of GDP in FY1947 to 6.1% of GDP in FY2016. That increase is largely attributable to growth in taxes that fund large entitlement programs. Shares devoted to corporate income and other outlays have declined, from 3.6% of GDP each in FY1947 to 1.6% of GDP and 1.7% of GDP, respectively, in FY2016.

Deficits, Debt, and Interest

The annual difference between revenue (i.e., taxes and fees) that the government collects and outlays (i.e., spending) results in either a budget deficit or surplus.27 Annual budget deficits or surpluses determine, over time, the level of publicly held federal debt and affect the level of interest payments to finance the debt.

Budget Deficits

Between FY2009 and FY2012, annual budgets as a percentage of GDP were higher than deficits in any four-year period since FY1945.28 The unified budget deficit in FY2016 was $585 billion, or 3.2% of GDP. The unified deficit, according to some budget experts, gives an incomplete view of the government's fiscal conditions because it includes off-budget surpluses.29 Excluding off-budget items (i.e., Social Security benefits paid net of Social Security payroll taxes collected and the U.S. Postal Service's net balance), the on-budget FY2016 federal deficit was $620 billion.

Budget Deficit for FY2017

The June 2017 CBO baseline estimated the FY2017 budget deficit at $693 billion, or 3.6% of GDP. The rise in the estimated budget deficit for FY2017 is the result of decreases in real revenues and a small increase in real spending. FY2017 outlays are projected to increase to 21.0% of GDP from 20.9% of GDP in FY2016; revenues are projected to be 17.3% of GDP in FY2017, down from 17.8% of GDP in FY2016.

Federal Debt and Debt Limit

Gross federal debt is composed of debt held by the public and intragovernmental debt. Intragovernmental debt is the amount owed by the federal government to other federal agencies, to be paid by the Department of the Treasury, which mostly consists of money contained in trust funds. Debt held by the public is the total amount the federal government has borrowed from the public and remains outstanding. This measure is generally considered to be the most relevant in macroeconomic terms because it is the debt sold in credit markets. Changes in debt held by the public generally track the movements of the annual unified deficits and surpluses.30

Historically, Congress has set a ceiling on federal debt through a legislatively established limit. The debt limit also imposes a type of fiscal accountability that compels Congress (in the form of a vote authorizing a debt limit increase) and the President (by signing the legislation) to take visible action to allow further federal borrowing when nearing the statutory limit.

The debt limit by itself has no effect on the borrowing needs of the government.31 The debt limit, however, can hinder the Treasury's ability to manage the federal government's finances when the amount of federal debt approaches this ceiling. In those instances, the Treasury has had to take extraordinary measures to meet federal obligations, leading to inconvenience and uncertainty in Treasury operations at times.32

A binding debt limit would prevent the Treasury from selling additional debt and could prevent timely payment on federal obligations, resulting in default. Possible consequences of a binding debt limit include (1) a reduced ability of Treasury to borrow funds on advantageous terms, resulting in further debt increases; (2) negative outcomes in global economies and financial markets; and (3) acquisition of penalties or fines from the failure to make timely payments. More broadly, a binding debt limit may also affect the perceived credit risk of federal government borrowing. Consequently, the fiscal space available to the federal government could decline.

Net Interest

In FY2016, the United States spent $240 billion, or 1.3% of GDP, on net interest payments on the debt. What the government pays in interest depends on market interest rates as well as the size and composition of the federal debt. Currently, low interest rates have held net interest payments as a percentage of GDP below the historical average despite increases in borrowing to finance the debt.33 Some economists, however, have expressed concern that federal interest costs could rise once the economy fully recovers, resulting in future strain on the budget. Interest rates are projected to gradually rise in the CBO baseline, resulting in net interest payments of $818 billion (2.9% of GDP) in FY2027. If interest costs rise to this level, they would be higher than the historical average.34

Recent Budget Policy Legislation and Events35

Congress has enacted several pieces of legislation in recent years with significant ramifications for the federal budget. The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25) increased the debt limit and required deficit reduction (ultimately implemented through across-the-board spending cuts) and caps on discretionary budget authority. Subsequent revisions to the spending reductions established in the BCA were enacted through the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; P.L. 113-67), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74). ATRA also made several changes to the federal tax code, making some previously temporary reductions in individual income tax rates permanent, allowing some tax cuts to expire, and making other changes. Meanwhile, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113) made a number of changes to a group of tax provisions known as "tax extenders," permanently incorporating some provisions into the tax code and temporarily extending others through the 2016 or 2019 tax years. Finally, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31) provided continuing appropriations for the remainder of FY2017, while BBA 2015 allowed for reinstatement of the statutory debt limit in March 2017.

Deficit Reduction Legislation: the Budget Control Act of 201136 and Later Amendments

The BCA was enacted on August 2, 2011. The law contained a variety of measures intended to reduce the deficit by at least $2.1 trillion over the FY2012-FY2021 period, along with a mechanism to increase the debt limit. Deficit reduction provisions included $917 billion in savings from statutory caps on discretionary spending and the establishment of a Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction (Joint Committee) to identify further budgetary savings of at least $1.2 trillion over 10 years. As the Joint Committee was unable to reach an agreement, an automatic spending reduction process was triggered to begin in FY2013. This automatic process was intended to reduce spending levels further in the absence of other legislation to implement these changes. The process consisted of lowering annual caps on discretionary defense and nondefense budget authority and automatic reductions for certain types of mandatory spending, which were initially effective from FY2013 through FY2021.

The deficit reduction measures established by the BCA were subsequently amended on a number of occasions. The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240) made significant modifications to the tax code (see below), but also postponed and raised (or allowed for more spending under) the caps on defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority in FY2013. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; P.L. 113-67) raised the caps on defense and nondefense budget authority by a combined $45 billion in FY2014 and $18 billion in FY2015, and extended automatic mandatory spending reduction measures through FY2023. Finally, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74) raised the caps on defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority by a combined $50 billion in FY2016 and $30 billion in FY2017, and extended automatic mandatory spending reduction measures through FY2025. The budgetary effects of these amendments to the BCA were each offset by other changes in spending and revenue unrelated to the BCA. Moreover, each amendment to the caps on discretionary budget authority included equal adjustments to the defense and nondefense categories. Table 2 shows how the discretionary caps from FY2014 through FY2021 have changed since enactment of the BCA.

Table 2. Discretionary Caps on Budget Authority Established by the BCA as Amended

(in billions of dollars)

|

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

FY2021 |

|

|

Original limits established by the BCA |

||||||||

|

Defense |

556 |

566 |

577 |

590 |

603 |

616 |

630 |

644 |

|

Nondefense |

510 |

520 |

530 |

541 |

553 |

566 |

578 |

590 |

|

Total |

1,066 |

1,086 |

1,107 |

1,131 |

1,156 |

1,182 |

1,208 |

1,234 |

|

Revised limits following a lack of agreement from the Joint Committee |

||||||||

|

Defense |

501 |

511 |

522 |

535 |

548 |

561 |

575 |

589 |

|

Nondefense |

472 |

482 |

493 |

505 |

517 |

532 |

545 |

558 |

|

Total |

973 |

994 |

1,016 |

1,040 |

1,066 |

1,093 |

1,120 |

1,147 |

|

Current limits following legislative changes and revised projections |

||||||||

|

Defense |

520 |

521 |

548 |

551 |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

|

Nondefense |

492 |

492 |

518 |

519 |

516 |

529 |

542 |

555 |

|

Total |

1,012 |

1,014 |

1,066 |

1,070 |

1,065 |

1,091 |

1,118 |

1,145 |

Source: CBO, Sequestration Update Report: August 2012, Table 2; and OMB, OMB Sequestration Preview Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2018, Table 2.

Notes: Limits in 2012 and 2013 were assigned to Security and Nonsecurity categories. Totals may not sum due to rounding. Legislative changes were enacted in ATRA, BBA 2013, and BBA 2015. The BCA requires CBO and OMB to periodically revise future discretionary limits to ensure that the deficit reduction targets established by the BCA as amended are reached.

Tax Reform: the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 201237 and Tax Extenders Legislation

In addition to the deficit reduction measures discussed above, the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240) made a variety of changes to tax policy. Included among those changes were the permanent extension of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts on both ordinary income and capital gains and dividends for taxpayers with taxable income below $400,000 ($450,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly). For taxpayers with taxable income above those thresholds, the marginal tax rate on ordinary income rose from 35% to 39.6% on the portion of their income above these thresholds, and the top tax rate on long-term capital gains and dividends rose from 15% to 20%. ATRA also reinstated the personal exemption phase-out (PEP) and limitation on itemized deductions (Pease) for taxpayers with adjusted gross income (AGI) above $250,000 ($300,000 for married couples filing jointly), allowing these limitations to expire for those with AGI below these thresholds. ATRA also extended the tax changes to a variety of tax credits, provided marriage tax penalty relief, and modified certain education-related tax incentives. ATRA also included a permanent "patch" for the alternative minimum tax and provided permanent estate and gift tax rules.

There has also been activity on a set of tax provisions that expired or were due to expire several times in recent years and extended on each occasion, known as "tax extenders." Most recently, the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015 (PATH Act) was enacted as Division Q of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113). The PATH Act extended 56 tax provisions that expired at the end of tax year 2014, and which had been extended several times in recent years. The PATH Act included three types of extensions: 30 tax preferences were extended for two years, through tax year 2016; four provisions were extended for five years, through tax year 2019; and 22 provisions were made permanent. No subsequent legislation on these provisions has been enacted, including provisions that expired at the end of tax year 2016.

Appropriations and Debt Limit Legislation

Each year Congress enacts a set of laws providing for discretionary appropriations, which provides federal agencies the authority to incur obligations. Appropriations acts typically provide authority for a single fiscal year, and may come in the form of regular appropriations (providing authority for the next fiscal year), supplemental appropriations (providing additional authority for the current fiscal year), or continuing appropriations (providing stop-gap authority for agencies without a regular appropriation).38 Most recently, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31) was passed on May 5, 2017, providing continuing appropriations for all federal agencies without a regular appropriation through the end of FY2017 (which ends September 30, 2017). Time periods for which no or incomplete appropriations are provided are known as funding lapses, and may result in partial or full shutdown of federal operations; the last such period occurred in October 2013. 39

Recent legislation has also modified the statutory debt limit. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74) suspended the debt limit until March 15, 2017, and dictated that the debt limit be increased upon reinstatement as needed to exactly accommodate any additional federal borrowing undertaken up to that point.40 On March 16, 2017, the debt limit was reinstated at $19.809 trillion. As of April 30, 2017, federal debt subject to limit was approximately $19.809 trillion, of which $14.279 trillion was held by the public.41 On March 8, 2017, Secretary Mnuchin sent a letter to congressional leadership stating Treasury's intent to undertake extraordinary measures upon debt limit reinstatement, and requested that the debt limit be raised.42

Budget for FY2018

The Trump Administration submitted its FY2018 budget to Congress on May 23, 2017. The President's budget lays out the Administration's views on national priorities and policy initiatives. Congress has also begun consideration of the FY2018 budget.

Trump Administration's FY2018 Budget

President Trump presented his policy agenda in the Administration's FY2018 budget submission. If the policies are fully implemented, the Administration estimates that total FY2018 outlays would be $4,094 billion (20.5% of GDP) and revenues would be $3,654 billion (18.3% of GDP), resulting in a budget deficit of $440 billion (2.2% of GDP). Deficits under the proposed budget decline over the course of the budget window, with the significance of the decline varying with what baseline is being considered and how certain macroeconomic effects are applied to the forecast.

|

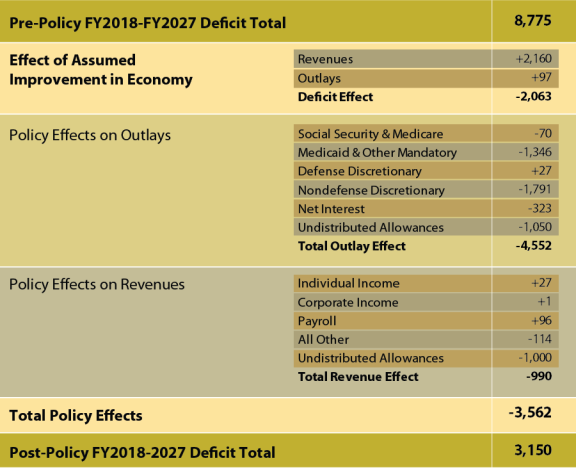

Figure 4. Budgetary Effects of Proposals in President's FY2018 Budget (in billions of dollars) |

|

|

Source: OMB, Budget of the U.S. Government Fiscal Year 2018, Tables S-1 through S-3. Notes: For past budgets CBO has provided an independent analysis of proposals in the President's budget. That information has not yet been released. The budget incorporates economic improvements before individual policy budget effects are measured, though the policy proposals appear to cause such improvements; further discussion of this process is provided in the text. Undistributed allowances reflect changes made to policies related to the Affordable Care Act (P.L. 111-5) and to infrastructure programs. |

A summary of the total deficit effects of the budget's proposed changes is presented in Figure 4. On the spending side, the budget proposes reforms that would reduce several types of outlays. The largest spending cut proposals are to: (1) nondefense discretionary programs, with an outlay reduction of $1.79 trillion from FY2018 through FY2027; (2) Medicaid and other mandatory programs (including Children's Health Insurance and welfare), with $1.35 trillion in FY2018-FY2027 outlay reductions; (3) cuts attributable to repeal and replacement of the Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-48), with $1.25 trillion in FY2018-FY2027 outlay reductions; and (4) net interest spending, with $323 billion in FY2018-FY2027 outlay reductions. The budget proposes an increase in infrastructure spending, which would result in total outlays increasing by $200 billion over the FY2018-FY2027 period. Finally, the budget proposes mostly offsetting changes to the defense budget, with increases in "base" defense spending and decreases in Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) spending resulting in an increase in discretionary defense outlays of $27 billion over the FY2018-FY2027 period.

The President's budget does not include an explicit policy proposal for federal tax reform, but lists a number of "core principles," which include (1) reduced individual and corporate income tax rates; (2) a switch to a territorial corporate income tax system; (3) large modifications to individual and corporate income tax deductions; and (4) repeal of the estate tax and 3.8% surtax on capital gains earnings. The Administration expressed a desire to makes those reforms deficit-neutral. Finally, the budget includes an allowance for a repeal of ACA-related taxes, which accounts for a revenue reduction of $1.00 trillion over the FY2018 to FY2027 window.

The President's budget uses economic projections in its calculations that differ from those used in congressional budget operations. The budget projects that the real economic growth rate (measured as the percentage change in GDP) will rise from 1.6% in FY2016 to 3.0% per year over the FY2021 through FY2027 period. That total is higher than the assumptions included in CBO's June 2017 forecast, which includes real economic growth projections of 1.9% per year from FY2021 through FY2027. Previous iterations of the President's budget have also included differences in economic projections with those produced by CBO, though such differences have typically been smaller than the current projection gap.43 The United States last experienced real economic growth of greater than 3.0% in FY2005.44 The increased growth accounts for improved economic outcomes under the President's budget, reducing deficits by $2.06 trillion over the FY2018 to FY2027 window.

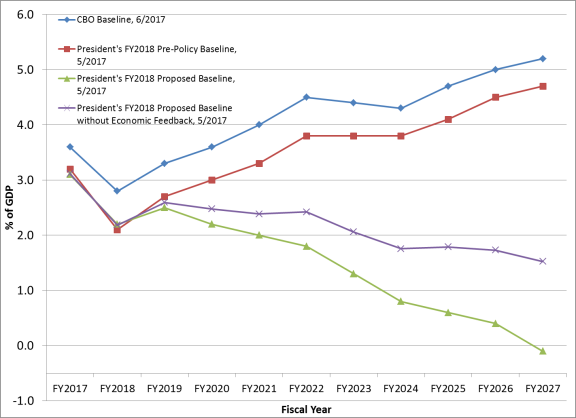

Deficit Projections in the President's FY2018 Budget

The Trump Administration provided two deficit projections in its FY2018 budget.45 First, OMB projected a Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act (BBEDCA) baseline as required by statute. The BBEDCA baseline, or "pre-policy" baseline, assumes that discretionary spending remains constant in real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) terms and revenue and mandatory (or direct) spending continue as under current law.46 Under this scenario, the FY2018 deficit is projected to total $413 billion, the FY2027 deficit is projected to be $1.34 trillion, and cumulative deficits are projected to be $8.78 trillion over the FY2018-FY2027 period.

The other deficit projection, the proposed budget, illustrates the impact on the budget outlook if all of the policies proposed in the budget are implemented. In FY2018, the Administration projects that the deficit will reach $440 billion, or 2.2% of GDP. Under the proposed budget, deficits would steadily decrease from FY2019 through FY2026, and produce a budget surplus of $16 billion (0.1% of GDP) in FY2027. The net budget deficit from FY2018-FY2027 totals $3.15 trillion in the proposed budget.47

The deficits under the proposed baseline in the President's budget incorporate economic effects in a manner that has attracted considerable attention. The President's budget includes a line item for the effects of economic feedback separate from other policies in its list of proposals.48 However, in the budget publication, it states that,

The Administration projects a permanently higher trend growth rate as a result of its productivity-enhancing policies, such as tax reform, infrastructure investments, reductions in regulation, and a greatly improved fiscal outlook.49

Some outside analysts, including former Secretary of the Treasury and National Economic Council Director Lawrence Summers, contend that the Administration therefore double-counted the deficit reduction attributable to its economic growth, using it both to make policies such as tax reform deficit neutral and then again as a separate line-item.50 If economic feedbacks are removed as a separate line item from the President's budget, the proposed budget would project a deficit of $442 billion (2.2% of GDP) in FY2018. Deficits under that scenario would then gradually decline from $550 billion (2.6% of GDP) in FY2019 to $480 billion (1.5% of GDP) in FY2027.

Figure 5 illustrates how the levels in the President's proposed budget with and without separate economic feedback effects included compare to current law (CBO baseline) and the Administration's pre-policy baseline over the next decade.51 The proposals in the President's budget are projected to result in deficit reductions of $5.63 trillion over the next decade relative to the pre-policy baseline.52 If the economic feedback effects assumed to be separate from the policy-specific budget estimates are removed, the proposed budget reduces deficits by $3.56 trillion over the FY2018-FY2027 period relative to the pre-policy baseline.

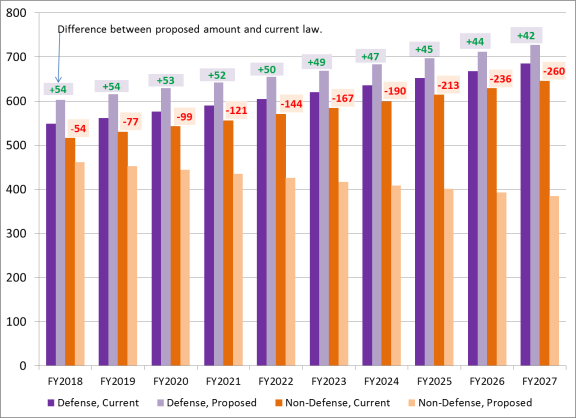

Adjustments to BCA Discretionary Caps

The President's budget proposes to adjust the caps on discretionary spending as originally established by the Budget Control Act (BCA). In August 2011, the BCA placed limits on discretionary budget authority and included provisions for additional spending cuts to be implemented through an automatic process. Since enactment of the BCA, Congress and the President have modified the BCA several times, primarily to allow increases in discretionary spending (for more information, see the section titled "Recent Budget Policy Legislation and Events").

A summary of the changes to the discretionary caps in the President's budget is presented in Figure 6. In FY2018, the President's budget would increase the cap (or allow for greater spending) on discretionary defense spending by $54 billion and decrease the discretionary nondefense spending cap by the same amount. The increases to the defense spending caps slowly decline in future years, while the decreases to nondefense spending caps increase over that time period. In FY2021, the last year that the caps are scheduled to be effective under current law, the President's budget proposes to increase the defense cap by $52 billion and decrease the nondefense cap by $121 billion.53 Under the assumption that the BCA caps are extended through FY2027 at rates which match growth in current services, the President's budget would increase the defense cap by $42 billion and decrease the nondefense cap by $260 billion in FY2027.

FY2018 Congressional Budget Activity

Following passage of full-year FY2017 appropriations, Congress has turned its attention to the FY2018 budget. The budget committees in the House and Senate each may develop a budget resolution as they receive information and testimony from a number of sources, including the Administration, the CBO, and congressional committees with jurisdiction over spending and revenues. Absent legislative action, the limits on discretionary budget authority for FY2018 are scheduled to be $549 billion for defense activities and $515 billion for nondefense activities, which is a combined $5 billion lower than the limits in FY2017.54

Considerations for Congress

Ongoing budgetary challenges remain, which may result in congressional action. Issues related to deficit reduction and the long-term budget outlook may continue to dominate the policy debate. Increased spending on entitlement programs, as currently structured, will likely contribute to rising deficits and debt, placing ever-increasing focus on how to achieve fiscal sustainability over the long term.

Ongoing Budget Issues

Various budget issues may feature prominently in near-term congressional debates. Discussions over FY2018 discretionary appropriations legislation may be held in advance of the beginning of the fiscal year (or afterwards in the case of supplemental or continuing appropriations). Congress may also choose to revisit the deficit reduction measures imposed by the BCA, as amended, ahead of FY2018, which include discretionary caps on defense and nondefense budget authority through FY2021 and spending reduction measures on certain mandatory programs through FY2025. Congress elected to lift the discretionary caps (allow for more spending) in each year from FY2013 through FY2017 relative to their values established in the BCA. Each of those modifications increased annual caps on defense and nondefense spending by equal measures, which is sometimes described as the "parity principle."55

Congress may also choose to modify the statutory debt limit. Treasury is currently implementing extraordinary measures to stay under the debt limit, which was reinstated in March 2017. Extraordinary measures were previously adopted in March 2015. Coupled with short-run budget surpluses in March and April of that year (which result primarily from the receipt of annual income tax returns), those measures were estimated to be exhausted in early November 2015, or shortly after the most recent debt limit suspension.56 The latest CBO budget forecast projects a larger nominal budget deficit in FY2017 ($559 billion) than the federal deficit in FY2015 ($466 billion). Such an increase may reduce the length of time extraordinary measures would postpone a binding debt limit relative to what was experienced in 2015.

Long-Term Considerations

The federal government faces long-term budget challenges. Occasional budget deficits are not necessarily problematic. Deficit spending can allow governments to smooth outlays and revenues to shield taxpayers and program beneficiaries from abrupt economic shocks in the short term, while also temporarily boosting GDP when the economy is underperforming. Persistent deficits, however, lead to growing levels of federal debt that may lead to higher interest payments and may also have adverse macroeconomic consequences in the long term, including slowing investment and lowering economic growth. Since the debt cannot grow faster than GDP indefinitely, large deficits will eventually need to be reduced through increases in taxes, reductions in spending, or both.

Some measures of fiscal solvency in the long term indicate that, under current policy, the United State faces major future imbalance, specifically as it relates to rising retirement and health care costs and the likely impact on government-financed health care spending. Existing deficit reduction policies like the BCA have improved recent and near-term deficits but do not make significant changes to the parts of the budget that are projected to grow the fastest in the long-run. Therefore, many budget analysts believe that additional deficit reduction is required to put the budget on a sustainable path over the long term. CBO's current law baseline projects inflation-adjusted deficits that are greater than the postwar average in each year of their most recent 10-year baseline.

CBO, GAO, and the Trump Administration agree that the current mix of federal fiscal policies is unsustainable in the long term. The nation's aging population, combined with rising health care costs per beneficiary, may keep federal health costs rising faster than per capita GDP. CBO projected in March 2017 that under current policy, federal spending on health programs (including Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, and exchange subsidies) would grow from 5.5% of GDP in FY2017 to 8.8% of GDP in FY2047.57 A 2017 GAO report on fiscal health also cited health spending as a source of concern.58 Though these forecasts are highly uncertain, it seems probable that spending on these programs will rise as a share of GDP over time.

In addition, growing debt and rising interest rates are projected to cause interest payments to consume a greater share of future federal spending. CBO projects that under current law, spending to service the federal debt (net interest payments) will grow rapidly, from 1.4% of GDP in FY2017 to 5.2% of GDP in FY2047.59 GAO's recent long-term fiscal simulations, under an alternative policy scenario, projected that debt held by the public as a share of GDP would exceed the post-World War II historical high in the next 15 to 25 years.60

Keeping future federal outlays at 20% of GDP, or approximately at its historical average, and leaving fiscal policies unchanged, according to CBO projections, would require drastic reductions in all spending other than that for Medicare, Social Security, and Medicaid, or reining in the costs of these programs. Under CBO's extended baseline, maintaining the debt-to-GDP ratio at today's level (77%) in FY2047 would require an immediate and permanent cut in non-interest spending, increase in revenues, or some combination of the two in the amount of 1.9% of GDP (or about $380 billion in FY2018 alone) in each year. Maintaining this debt-to-GDP ratio beyond FY2047 would require additional deficit reduction. If policymakers wanted to lower future debt levels relative to today, the annual spending reductions or revenue increases would have to be larger. For example, in order to bring debt as a percentage of GDP in FY2046 down to its historical average over the past 50 years (40% of GDP), spending reductions or revenue increases or some combination of the two would need to generate net savings of roughly 3.1% of GDP (or $620 billion in FY2018 alone) in each year.61

The alternative to decreased spending as a means of deficit reduction is to increase revenues through modifications to the federal tax system. Recently discussed reforms include the "A Better Way Proposal" 62 released by House Speaker Paul Ryan in June 2016 and recent tax reform goals published by the Trump Administration.63 Congressional scorekeepers have not yet evaluated the budgetary effects of those proposals, though in each case the authors have expressed a desire for the reforms to be "revenue neutral," or to keep total revenue projections unchanged over the 10-year budget window.64 While tax reform proposals may intend to address other policy goals, those that are revenue neutral are therefore unlikely to significantly alter the long-run budgetary outlook.

In the long-run, increases in federal debt are constrained by the amount of remaining "fiscal space," or the amount of government borrowing that creditors are willing to finance. The amount of fiscal space available depends on both the current size of the debt and how fast it is increasing relative to GDP. The latter depends on the size of deficits, the government's borrowing rate, and how quickly the economy is growing. With continuously increasing debt levels, at some point debt would become so large that investors would no longer be willing to finance deficits and fiscal space would be exhausted. There is great uncertainty about when investors would stop financing federal borrowing. Because interest rates are presently lower than their historical averages, there is little concern that the federal government is in danger of running out of fiscal space in the short run.65

Appendix. Budget Documents

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) provides data and analysis to Congress throughout the budget and appropriations process. Each January, CBO issues a Budget and Economic Outlook that contains current-law baseline estimates of outlays and revenues. In March, CBO typically issues an analysis of the President's budget submission with revised baseline estimates and projections. These documents can be delayed as a result of the legislative agenda or if the President's budget is off schedule. In late summer, CBO issues an updated Budget and Economic Outlook with new baseline projections.

In these documents, CBO sets a current-law baseline as a benchmark to evaluate whether legislative proposals would increase or decrease outlays and revenue collection. Baseline estimates are not intended to predict likely future outcomes, but to show what spending and revenues would be if current law remained in effect. CBO typically evaluates the budgetary consequences of most legislative proposals and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) evaluates the consequences of revenue proposals.

CBO also releases other periodic publications focusing on the future fiscal health of the United States. In its publication The Long-Term Budget Outlook, CBO makes projections on the state of the federal budget over the next 75 years. CBO discusses spending and revenue levels and the related issues that it expects will arise under different policy assumptions. In its Budget Options volumes, CBO provides specific policy options and the impact they will have on spending and revenues over a 10-year budget window. CBO also provides arguments for and against enacting each policy.

The President's budget contains five major volumes: (1) The Budget, (2) Historical Tables, (3) Analytical Perspectives, (4) Appendix, and (5) Supplemental Materials.66 These documents lay out the Administration's projections of the fiscal outlook for the country, along with spending levels proposed for each of the federal government's departments and programs. The Historical Tables volume also provides significant amounts of budget data, much of which extend back to 1962 or earlier. Along with the Administration's budget documents, the Department of the Treasury also releases its Green Book, which provides further detail on the revenue proposals that are contained in the budget.67

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For more information, see CRS Report 98-721, Introduction to the Federal Budget Process, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 2. |

This section provides an outline for the formulation and execution of a budget and appropriations cycle for a fiscal year. However, this timetable is not fixed and often varies by year. |

| 3. |

CRS Report 98-325, The Federal Fiscal Year, by [author name scrubbed] |

| 4. |

The contents of the presidential budget submission are governed by 31 U.S.C. §1105. For reasons why the budget may be delayed, see CRS Report RS20179, The Role of the President in Budget Development, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 5. |

For more information, see CRS Report RL30297, Congressional Budget Resolutions: Historical Information, by [author name scrubbed] |

| 6. |

For information on deeming resolutions, see CRS Report R44296, Deeming Resolutions: Budget Enforcement in the Absence of a Budget Resolution, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 7. |

Budget authority represents the amounts appropriated for a program, or the funds that may legally be spent. Outlays represent the disbursed federal funds. There is generally a lag between when budget authority is appropriated and outlays occur, sometimes across fiscal years. |

| 8. |

For more information on the appropriations and authorization process, see CRS Report R42388, The Congressional Appropriations Process: An Introduction, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 9. |

The fiscal year runs from October through September: FY2017 began on October 1, 2016, and ends on September 30, 2017. |

| 10. |

Many of the rules governing the baseline contained in Section 257 of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act, as amended, were extended or modified as part of the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25). |

| 11. |

The BCA allows for discretionary spending to be adjusted for war funding, disaster, emergency, and program integrity spending. |

| 12. |

The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015 (PATH Act), passed as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113; see additional discussion below), modified most of the previously expired tax provisions that had been extended several times by past Congresses. The PATH Act made many of those provisions permanent, while others were extended through the 2016 or 2019 tax year. Provisions that were not made permanent are assumed to expire as scheduled under the CBO baseline. |

| 13. |

CBO, An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, June 2017. |

| 14. |

Unless otherwise noted, budget data in this report are taken from tables in CBO, An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, June 2017. |

| 15. |

Except where otherwise noted, all deficit and debt figures are expressed as a percentage of GDP, in order to account for inflation and business cycle effects. |

| 16. |

For more information on the interaction of deficits and debt, see CRS Report R44383, Deficits and Debt: Economic Effects and Other Issues, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 17. |

Although both types of spending had previously existed, historical data distinguishing between discretionary and mandatory spending in the federal budget were first collected in FY1962. |

| 18. |

For more information on trends in discretionary and mandatory spending, see CRS Report RL34424, The Budget Control Act and Trends in Discretionary Spending, by [author name scrubbed], and CRS Report RL33074, Mandatory Spending Since 1962, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 19. |

Net interest is discussed in further detail in the section "Deficits, Debt, and Interest." |

| 20. |

The definition of security spending has varied over time. The Obama Administration defined security spending as funding for the Department of Defense – Military, the Department of Energy's National Nuclear Security Administration, International Affairs (budget function 150), the Department of Homeland Security, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Security spending has defense and nondefense components. |

| 21. |

The caps on discretionary spending contained in the BCA expire after FY2021. Beginning in FY2022, the baseline assumes that discretionary spending will grow at the rate of inflation, which is generally less than the projected growth of nominal GDP. Therefore, discretionary spending continues to fall, as a percentage of GDP, throughout the budget window. |

| 22. |

Net interest payments are a function of the existing stock of publicly held debt, which is the product of past federal budget outcomes, and prevailing interest rates, which are determined by economic conditions. Congress's ability to influence the level of short-term net interest payments is limited. |

| 23. |

For more information, see CRS Report R41970, Addressing the Long-Run Budget Deficit: A Comparison of Approaches, by [author name scrubbed], and CRS Insight IN10623, The Federal Budget Deficit and the Business Cycle, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 24. |

In various reports, the Congressional Budget Office, the Government Accountability Office, and the Trump Administration agree that the federal government's budget is on an unsustainable path. For more information, see the section of this report titled "Long-Term Considerations." |

| 25. |

For more information on ATRA's tax provisions, see CRS Report R42894, An Overview of the Tax Provisions in the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 26. |

For more information, see CRS Report RL32808, Overview of the Federal Tax System, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 27. |

Unlike many state and local governments, the federal government has no statutory balanced-budget requirement or a separate budget for capital spending. |

| 28. |

The budget deficit peaked at 9.8% of GDP in FY2009. |

| 29. |

From an overall budget perspective, these surpluses are used to offset other federal spending, thereby decreasing the current budget deficit while increasing the amount of Treasury securities held in the Social Security Trust Funds. Off-budget surpluses have historically been large. However, declining surpluses in the Social Security program will lead to off-budget deficits beginning in FY2017 according to the CBO baseline. |

| 30. |

For more information on the components of federal debt, see CRS Report R44383, Deficits and Debt: Economic Effects and Other Issues, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 31. |

The need to raise (or lower) the limit during a session of Congress is driven by previous decisions regarding revenues and spending stemming from legislation enacted earlier in the session or in prior years. The consideration of debt limit legislation often is viewed as an opportunity to reexamine fiscal and budgetary policy. |

| 32. |

For more information, see CRS Report R41633, Reaching the Debt Limit: Background and Potential Effects on Government Operations, by [author name scrubbed] et al., and U.S. Government Accountability Office, Delays Create Debt Management Challenges and Increase Uncertainty in the Treasury Market, GAO-11-203, February 2011. |

| 33. |

Since FY1970, the United States has spent an average of 2.1% of GDP on net interest payments. |

| 34. |

For more information on the relationship between federal borrowing and net interest payments, see CRS Report R44383, Deficits and Debt: Economic Effects and Other Issues, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 35. |

This section is not meant to address all recently enacted changes in budget policy, but rather to highlight some of the major legislative actions and events. For more information on budget-related legislation in 2017, see CRS Report R44799, Budget Actions in 2017, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 36. |

For more information, see CRS Report R42506, The Budget Control Act of 2011 as Amended: Budgetary Effects, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 37. |

For more information, see CRS Report R42894, An Overview of the Tax Provisions in the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 38. |

For more information on the annual appropriations process, see CRS Report 98-721, Introduction to the Federal Budget Process, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 39. |

For more information on lapses of appropriations, see CRS Report RL34680, Shutdown of the Federal Government: Causes, Processes, and Effects, coordinated by [author name scrubbed], and CRS Report RS20348, Federal Funding Gaps: A Brief Overview, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 40. |

For more information on recent debt limit events, see CRS Report R43389, The Debt Limit Since 2011, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 41. |

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Monthly Statement of the Public Debt of the United States, April 30, 2017, May 2017, available at https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/mspd/2017/opds042017.pdf. |

| 42. |

U.S. Treasury, "Secretary Mnuchin Sends Debt Limit Letter to Congress," March 8, 2017, available at https://www.treasury.gov/initiatives/Documents/DL_SLGS_20170308_Ryan.pdf. |

| 43. |

For example, the first budget issued by the Obama Administration (released in 2009) included real economic growth assumptions of 2.6% per year in FY2016 through FY2019, as compared with 2.3% growth over the same period issued by CBO. Congressional Budget Office, A Preliminary Analysis of the President's Budget and an Update of CBO's Budget and Economic Outlook, Table 2-6, March 2009, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/111th-congress-2009-2010/reports/03-20-presidentbudget.pdf. |

| 44. |

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Table 1.1.1, May 2017. |

| 45. |

For details of these projections, see U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government Fiscal Year 2018, Tables S-1 through S-10. |

| 46. |

For a description of the policies included in the various baselines, see U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government Fiscal Year 2018, Analytical Perspectives. |

| 47. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government Fiscal Year 2018, Table S-1. |

| 48. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government Fiscal Year 2018, Tables S-2. |

| 49. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the U.S. Government Fiscal Year 2018, May 2017, p. 12. |

| 50. |

Summers, Lawrence, "A warning on Trump's budget," Financial Times, May 23, 2017, http://blogs.ft.com/larry-summers/2017/05/23/a-budget-warning/. |

| 51. |

Structural variation in economic modeling typically accounts for a small difference between baseline produced by CBO and the President's pre-policy baseline. |

| 52. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government Fiscal Year 2018, Table S-2. |

| 53. |

The Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act, as amended by the BCA, allows the discretionary caps to be adjusted for specific types of spending, including spending designated for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), Global War on Terrorism, disaster relief, and emergency requirements. |

| 54. |

For more information on FY2018 budget activity, see CRS Report R44799, Budget Actions in 2017, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 55. |

For more information on the parity principle and recent budget agreements, see CRS In Focus IF10657, Budgetary Effects of the BCA as Amended: The "Parity Principle", by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 56. |

More information on seasonal changes in budget outcomes may be found in CRS In Focus IF10292, The Debt Limit, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 57. |

Congressional Budget Office, The 2017 Long-Term Budget Outlook, March 2017. |

| 58. |

Government Accountability Office, The Nation's Fiscal Health: Action is Needed to Address the Federal Government's Fiscal Future, January 2017. |

| 59. |

Congressional Budget Office, The 2017 Long-Term Budget Outlook, March 2017. |

| 60. |

Government Accountability Office, The Nation's Fiscal Health: Action is Needed to Address the Federal Government's Fiscal Future, January 2017. |

| 61. |

Congressional Budget Office, The 2017 Long-Term Budget Outlook, March 2017. |

| 62. |

"A Better Way: Our Vision for a Confident America – Tax," June 24, 2016, available at https://abetterway.speaker.gov/_assets/pdf/ABetterWay-Tax-PolicyPaper.pdf. |

| 63. |

"2017 Tax Reform for Economic Growth and American Jobs," April 2017, available at http://taxprof.typepad.com/files/trump-tax-plan.pdf. |

| 64. |

Outside analysts have estimated that given the present levels of public detail provided for the "A Better Way" plan and the Trump Administration proposals, each plan would reduce federal revenues and thereby increase federal deficits over the 10-year budget window. For more information on recent tax reform proposals, see CRS Report R44771, An Overview of Recent Tax Reform Proposals, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 65. |

For more information on fiscal space, see CRS Insight IN10624, "Fiscal Space" and the Federal Budget, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 66. |

The President's budget proposals can be found on the OMB website at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/. The Supplemental Materials include the Federal Credit Supplement, the Object Class Analysis, the Balances of Budget Authority, and the Public Budget Database. |

| 67. |

The FY2018 Green Book has not yet been made available. For the FY2017 version, see U.S. Department of the Treasury, General Explanations of the Administration's Fiscal Year 2017 Revenue Proposals, February 2016, available at http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Pages/general_explanation.aspx. |