Additional Troops for Afghanistan? Considerations for Congress

The Trump Administration is reportedly considering proposals to deploy additional ground forces to Afghanistan and somewhat broaden their mission. These forces would likely be part of the Resolute Support Mission (RSM), the ongoing NATO mission to train and support Afghan security forces. In testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee on February 9, 2017, General John Nicholson, Commander U.S. Forces–Afghanistan, noted based on a mission review that he had adequate forces for the U.S. counterterrorism mission but there was “a shortfall of a few thousand troops” for RSM if a “stalemate” with the Taliban-led insurgency is to be broken. Especially in light of recent Afghan National Defense and Security Force (ANDSF) shortcomings, notably the Taliban gains in Helmand Province and the April 21, 2017, attack on an Afghan Army installation near Mazar-i-Sharif, some observers maintain additional forces are necessary to shore up the ANDSF.

There is no consensus as to the best way to determine the suitability, size, and mission profile of the ground elements of any military campaign. This short report is designed to assist Congress as it evaluates various proposals to introduce more ground forces for RSM.

Additional Troops for Afghanistan? Considerations for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Why This Issue Is Important to Congress

- Background

- Past U.S. Troop Levels in Afghanistan and Their Missions

- U.S. Force Levels in Afghanistan Since 2001

- The Missions

- Current Request for Additional U.S. Troops

- Potential Considerations for Congress

- What Is the Overall Strategy for Afghanistan, and How Do U.S. Forces Fit into It?

- How Will Additional U.S. Troops Be Employed?

- What Other Nations Might Provide Additional Forces?

- What Might Be the Impact on Readiness and Availability of U.S. Forces for Other Missions?

- What Might Be the Impact on Long-Term Strategy for Afghanistan?

Summary

The Trump Administration is reportedly considering proposals to deploy additional ground forces to Afghanistan and somewhat broaden their mission. These forces would likely be part of the Resolute Support Mission (RSM), the ongoing NATO mission to train and support Afghan security forces. In testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee on February 9, 2017, General John Nicholson, Commander U.S. Forces–Afghanistan, noted based on a mission review that he had adequate forces for the U.S. counterterrorism mission but there was "a shortfall of a few thousand troops" for RSM if a "stalemate" with the Taliban-led insurgency is to be broken. Especially in light of recent Afghan National Defense and Security Force (ANDSF) shortcomings, notably the Taliban gains in Helmand Province and the April 21, 2017, attack on an Afghan Army installation near Mazar-i-Sharif, some observers maintain additional forces are necessary to shore up the ANDSF.

There is no consensus as to the best way to determine the suitability, size, and mission profile of the ground elements of any military campaign. This short report is designed to assist Congress as it evaluates various proposals to introduce more ground forces for RSM.

Why This Issue Is Important to Congress

Through its oversight, authorization, and appropriations roles, Congress will likely play a central role in helping implement any decision to increase U.S. troop levels in Afghanistan, as well as any change in their mission. Beyond committing additional forces to Afghanistan, Congress will also likely need to address how sending additional forces to Afghanistan will affect the overall readiness of the U.S. military, the availability of forces in the event of a crisis elsewhere, and what additional resources will be required to support this potential long-term commitment of additional U.S. troops.

Background1

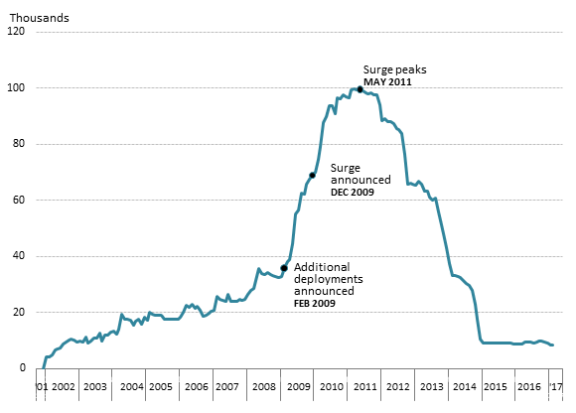

Today, the Afghanistan War—approaching 16 years—is the longest armed conflict in U.S. history. U.S. military forces entered Afghanistan in late 2001 in response to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks (see Figure 1). The United States and allies initially drove the Taliban from power and largely destroyed al Qaeda's ability to plan and execute terrorist attacks from Afghanistan. By October 2006, the United States and NATO had assumed responsibility for security across the whole of Afghanistan. In September 2008, President Bush deployed an extra 4,500 U.S. troops as part of what was described as a "quiet surge." In February 2009, the United States announced the deployment of 17,000 additional troops and NATO pledged to increase its military commitment to Afghanistan. In March 2009, President Obama decided to deploy an additional 4,000 personnel to train and advise the Afghan military and police, as well as support the development of Afghan government agencies. In December 2009, President Obama increased U.S. troop numbers by 30,000—bringing the total of U.S. troops to 100,000—and announced that the United States would begin withdrawing its forces by 2011. At the NATO Summit in Lisbon, Portugal, in November 2010, NATO agreed to hand control of security to Afghan forces by the end of 2014. In December of 2014, NATO formally ended its combat mission in Afghanistan and handed it over to Afghan forces. In January 2015, the NATO-led mission "Resolute Support" commenced, with the separate mission to train and advise and assist Afghan security forces. In October 2015, President Obama announced that 9,800 U.S. troops would remain in Afghanistan until the end of 2016, which differed from an earlier pledge to pull out all but about 1,000 U.S. troops from Afghanistan. In July 2016, at the NATO Warsaw Summit, in light of what he called "a precarious security situation," President Obama said that 8,400 U.S. troops would remain in Afghanistan. Also at the Summit, NATO agreed to maintain its troop levels and funding until 2020.

Past U.S. Troop Levels in Afghanistan and Their Missions

U.S. Force Levels in Afghanistan Since 2001

The Missions

Since the late 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, coalition troops have undertaken three basic missions, often simultaneously. The first mission, characterized as counterterrorism, primarily revolves around U.S. efforts to kill al Qaeda terrorists and destroy their networks. It is a mission that continues today. The second mission—conducted unilaterally or in conjunction with allied and Afghan forces—involved direct combat against Taliban insurgents attempting to reassert their control over Afghanistan. As previously noted, this mission ended for U.S. and NATO forces in December 2014. The third mission, which began early in the campaign and is the focus of the Resolute Support Mission (RSM) today, primarily involves working with allies to train and advise the Afghan military and police, as well as support the development of Afghan government agencies such as, for example, the Ministry of Defense. As part of RSM, U.S. advisors are not supposed to participate in direct combat unless it is in self-defense, but under certain circumstances, U.S. air support may be provided to Afghan security forces.

Current Request for Additional U.S. Troops

Recent press articles suggest that the Administration is considering proposals to deploy additional ground forces to Afghanistan.2 These forces would likely be part of the Resolute Support Mission, the ongoing NATO mission to train and support Afghan security forces. In testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee on February 9, 2017, General John Nicholson, Commander U.S. Forces–Afghanistan noted, based on a mission review, that he had adequate forces for the U.S. counterterrorism mission but there was "a shortfall of a few thousand troops" for RSM if what he described as a "stalemate" with the Taliban-led insurgency were to be broken.3 Recently, in April, about 300 U.S. Marines were deployed to Helmand Province to advise and assist Afghan forces in the region.4

The current Pentagon request reportedly under consideration, which requires presidential approval, is said to call for expanding the U.S. military role as part of a broader effort to compel the resurgent Taliban back to the negotiating table.5 As part of this expanding role, the Pentagon is reportedly considering deploying an additional 3,000 to 5,000 U.S. troops to Afghanistan, as well as asking for greater latitude in setting overall troop levels, determining how they might be used, at what level advisors might be assigned (battalion or company level), and providing military commanders greater authority for employing airstrikes.6

Potential Considerations for Congress

What Is the Overall Strategy for Afghanistan, and How Do U.S. Forces Fit into It?

Since the post-9/11 invasion of Afghanistan, the United States and its allies have pursued a variety of different strategic objectives. Within the military campaign alone, those objectives are, at times, in tension with each other. The initial goals for Afghanistan included the elimination of al Qaeda, and in the process, overthrowing the Taliban and installing a new, legitimate government in Kabul. Over time, however, these goals gave way to the more ambitious project of assisting the Afghan government as it extended its reach across the country—an inherently political undertaking—utilizing both civilian and military means to do so. This has led to considerable debate in Washington and around the world about the overall objectives for U.S. and international engagement there. Successive U.S. administrations have sought to synchronize the counterterrorism and nation-building missions, arguing that their operations are mutually reinforcing. In practice, however, their respective operations sometimes undermine each other. As one scholar notes, "the United States might be able to maintain an open-ended military presence in Afghanistan or stabilize the country, but not both."7

A recent example of these campaign tensions is the use of a GBU 43/B Massive Ordnance Air Blast (MOAB) munition to strike a cave complex used by the Islamic State affiliate in Afghanistan known as Islamic State- Khorasan Province (ISIL-K or ISKP). General Nicholson maintains the MOAB was the "right weapon against the right target," and that it dealt a devastating blow to ISKP.8 Other observers, however, note while General Nicholson is probably right about the tactical efficacy of the weapon, it has created an opportunity for opposition forces to foment further dissatisfaction among Afghans toward both their legitimate government in Kabul, as well as a continued U.S. presence in the country.9 Former Afghan President Karzai, for example, described the attack as the use of a weapon of mass destruction by the United States on Afghan soil, and an "immense atrocity against the Afghan people." The use of the MOAB, in his judgment, should be a clear signal to the Afghan people that they should stop the United States.10

In addition to the issue of different campaign elements sometimes working at cross-purposes, some observers question the overall feasibility of achieving stability in Afghanistan. According to the Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction, territory controlled by the Afghan government has receded by nearly 12% since November 2015, to approximately 60% of the country today.11 Complicating matters, U.S. commanders and other observers have noted other actors, such as Russia, might be supplying Taliban fighters, frustrating U.S. efforts on the ground.12

Accordingly, most scholars and practitioners note that the military elements of the campaign are necessary, but not sufficient, to deliver lasting stability in the region. In the first instance, building the conditions that might lead to a lasting peace settlement with the Taliban—the main opposing force to the Afghan government—is generally thought to require a broader strategy that addresses political, diplomatic, development, and governance building challenges.13 To date, the United States has yet to develop and implement a joint strategy with the Afghans for bringing the war to a successful conclusion.14 Second, as some note, the U.S. focus on countering terror threats such as those posed by Al Qaeda and the Islamic State rather than the Taliban has created a mismatch between Afghan and coalition objectives; the Afghan government itself is far more concerned with the Taliban.15 Finally, most scholars note the need to deal with Pakistan, which is generally believed to conduct activities that undermine U.S. and Afghan advances. In all of these respects, it is generally unclear how additional U.S. forces will help resolve these underlying campaign issues.

Others take the view that despite these difficulties, allowing Afghanistan to once again descend into chaos would ultimately harm U.S. national security.16 Such a vacuum might enable terrorist groups—including, but not limited to al Qaeda and the Islamic State—to plan and launch attacks against the United States and its allies. An influx of additional forces might therefore be better able to monitor, if not manage, terrorist groups and other threats using Afghanistan and the region as a safe haven.

How Will Additional U.S. Troops Be Employed?

In testimony, General Nicholson noted he had adequate forces for the U.S. counterterrorism mission but there was "a shortfall of a few thousand troops" for RSM.17 He suggested additional troops were needed to bolster the training and advising of Afghan units, increase advisory efforts across Afghan ministries, and provide more advisory capacity at brigade level. General Nicholson suggested the additional troops could also be provided by NATO partners (more below). DOD's reported current request supposedly will give military officials greater latitude in determining how U.S. troops may be employed, which suggests they could be used not only in ongoing counterterrorism operations but in a combat role as well.

In order to gain a better understanding of how the Pentagon plans to use these additional troops, policymakers might benefit from a detailed breakdown of what types of troops are required and where and how they will be employed. Will these additional troops be used primarily in a training and advisory capacity, or can they also be involved in combat operations independent of or in support of Afghan security forces? Also, if additional U.S. forces are to take on an enhanced role, does this mean that the current RSM-dedicated U.S. troops in Afghanistan will also be permitted to operate in a manner that is outside their current training and advisory mandate? If missions for U.S. forces are enhanced or changed, will this require changes to existing Rules of Engagement (ROE)18 and, if so, will new ROEs conflict with those employed by non-U.S. NATO and coalition forces in Afghanistan?

What Other Nations Might Provide Additional Forces?

According to NATO, as of February 2017, there were 13,459 troops deployed from 39 nations to support RSM, including 6,941 U.S. troops.19 There are also an unspecified number of U.S. troops in Afghanistan dedicated to the U.S. counterterrorism mission, which could account for the 8,400 overall U.S. troop level cited in congressional testimony20 and in press reports. Reportedly, the United States has asked NATO partners and other nations for additional troops21 and any additional non-U.S. troops could help to meet General Nicholson's requirement for "a few thousand more troops" to assist in advisory and training activities. According to one report, NATO is currently considering the U.S request for additional troops but any NATO troops provided would not participate in direct combat missions.22

Depending on the possible contributions of troops from other nations, the United States could send anywhere from a few hundred to 5,000 troops to Afghanistan. Because troop-contributing nations in the past have placed "caveats" on where and how their troops may be employed, additional U.S. forces might be required to assume a greater burden and conduct missions that other countries are unable to because of caveats. If additional non-U.S. forces are made available, policymakers might decide to examine how they will be employed and if there are associated caveats as to their use and how these caveats might affect the employment of U.S. forces.

What Might Be the Impact on Readiness and Availability of U.S. Forces for Other Missions?

While an additional commitment of U.S. troops could prove to be modest, ongoing operations in Iraq, Syria, Eastern Europe, and the unpredictable threat from North Korea could create a demand for additional U.S. forces that is not currently forecasted. Ultimately, any troops that are deployed to Afghanistan, as well as those training to replace them, will be taken out of the "pool" of forces available and ready to respond to other possible contingencies.

The potential commitment of additional Army forces to Afghanistan also has implications for Army readiness. When units are sent on Train, Advise and Assist (TAA) missions, typically only officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) are required in great numbers, meaning these individuals are "stripped" from existing units. The remaining junior officers, NCOs, and enlisted soldiers in those units are unable to train fully because they lack senior leadership. To address this problem, the Army is planning to establish six Security Force Assistance Brigades (SFABs)—four in the Active Component and two in the Army National Guard—comprising approximately 500 officers and NCOs each, to be used for such missions instead of stripping Brigade Combat Teams of their leadership and degrading readiness.23 These SFABs will not be available initially; plans call for the first SFAB to be available for deployment by the end of 2018 and that all brigades be established by 2022.24

From a joint force perspective, policymakers might decide to examine how committing additional forces to Afghanistan—possibly raising the level to over 10,000 U.S. troops—affects the force pool and overall force readiness. The possible addition of 3,000 to 5,000 U.S. troops and the resulting nonavailability of those units designated to take their place carries with it an element of risk to U.S. national security that policymakers might consider.

What Might Be the Impact on Long-Term Strategy for Afghanistan?

As noted above, the military campaign in Afghanistan has evolved over the past 16 years, as have U.S. strategic goals for the region. At present, it is difficult to discern an overall, coherent strategy for Afghanistan, although this may be resolved by the Trump Administration's review of U.S. activities in that region. Absent clear and coherent guidance, some observers question whether the key objective for the United States is primarily enabling a coalition withdrawal by building a capable and credible Afghan security force, or whether the United States is instead more concerned with maintaining a long-term counterterrorism presence in the country or avoiding major territorial gains by the Taliban.25 Still others wonder what an influx of several thousand additional forces might realistically do to "break the stalemate," and thereby force the Taliban to accept a political settlement. Skeptics note that the coalition was unable to achieve that objective earlier in the campaign when over 100,000 troops were in theater; however, it is not clear whether this was a result of strategy or execution issues, or both.26 Given the complexity of the campaign, along with the imprecise nature of U.S. goals for the region and absent a definitive statement from the Trump Administration regarding its priorities, it is currently difficult to evaluate the likely impact that additional forces may have.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Information in this section is taken from CRS Report RL30588, Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 2. |

Lolita C. Baldor, "New Afghanistan Troop Plan Goes to White House Next Week," Associated Press, May 4, 2017. |

| 3. |

Dan Lamothe, "Top U.S. Commander in Afghanistan Opens Door to a 'Few Thousand' More Troops Deploying There," Washington Post, February 9, 2017. |

| 4. |

Jeff Schogol, "Back in Afghanistan: Exposed to Some Danger Commander Says," Marine Corps Times, May 3, 2017. |

| 5. |

Missy Ryan and Greg Jaffe, "U.S. Poised to Expand Military Effort Against Taliban in Afghanistan," Washington Post, May 8, 2017. |

| 6. |

Ibid. |

| 7. |

Barnett Rubin, "It's Much Bigger Than Afghanistan: U.S. Strategy for a Transformed Region," War on the Rocks, April 25, 2015, https://warontherocks.com/2017/04/its-much-bigger-than-afghanistan-u-s-strategy-for-a-transformed-region/. |

| 8. |

NATO Resolute Support Mission, "Transcripts: Remarks by Gen. Nicholson: Strike by U.S. Forces Against ISIS-K Complex in Nangahar Province," April 13, 2017, http://www.rs.nato.int/article/transcripts/opening-remarks-by-general-john-nicholson-commander-u.s.-forces-afghanistan-regarding-april-13.html. |

| 9. |

Al Jazeera, "MOAB Attack: Condemnation, Praise Over Massive Bombing," April 14, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/04/hamid-karzai-condemns-mother-bombs-170414124459611.html. |

| 10. |

Interview with Hamid Karzai, "Hamid Karzai Condemns U.S. MOAB Strike on Afghanistan," The Daily Telegraph, April 17, 2017, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/04/17/hamid-karzai-condemns-us-moab-strike-afghanistan/; https://twitter.com/KarzaiH/status/852607272035524609. |

| 11. |

Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction, "April 2017 Quarterly Report," April 30, 2017, pp. 87-88, https://sigar.mil/pdf/quarterlyreports/2017-04-30qr-section3-security.pdf. The same report notes that 65.6% of the Afghan population falls under Afghan Government control. |

| 12. |

Phil Stewart and Idrees Ali, "Russia May Be Helping Supply Taliban Insurgents: U.S. General," Reuters, May 23, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-afghanistan-russia-idUSKBN16U234. |

| 13. |

Michael G. Waltz, "The American Legacy in Afghanistan does not have to be Defeat," War on the Rocks, May 12, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/05/no-retreat-the-american-legacy-in-afghanistan-does-not-have-to-be-defeat/. |

| 14. |

Christopher Kolenda, "Seven Questions Congress should Ask about Trump's Mini-Surge in Afghanistan," The Hill, May 11, 2017. Available at http://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/defense/332928-seven-questions-congress-should-ask-about-trumps-mini-surge-in. |

| 15. |

Stephen Tankel, "Back to First Principles: Four Fundamental Questions about Afghanistan," War on the Rocks, May 15, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/05/back-to-first-principles-four-fundamental-questions-about-afghanistan/. |

| 16. |

Ronald Neumann, David Petraeus and Earl Anthony Wayne, "An Afghanistan Strategy for Trump, " The National Interest, April 16, 2017, http://nationalinterest.org/feature/strategy-trump-afghanistan-20189. |

| 17. |

Dan Lamothe, "Top U.S. Commander in Afghanistan Opens Door to a 'Few Thousand' More Troops Deploying There," Washington Post, February 9, 2017. |

| 18. |

Rules of engagement (ROE) are defined as "military directives meant to describe the circumstances under which ground, naval, and air forces will enter into and continue combat with opposing forces. Formally, rules of engagement refer to the orders issued by a competent military authority that delineate when, where, how, and against whom military force may be used, and they have implications for what actions soldiers may take on their own authority and what directives may be issued by a commanding officer. Rules of engagement are part of a general recognition that procedures and standards are essential to the conduct and effectiveness of civilized warfare," https://www.britannica.com/topic/rules-of-engagement-military-directives, accessed May 19, 2017. |

| 19. |

http://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2015_02/20150227_1502-RSM-Placemat.pdf, accessed May 10, 2017. |

| 20. |

NATO Resolute Support Mission, "Transcripts: Remarks by Gen. Nicholson: Strike by U.S. Forces Against ISIS-K Complex in Nangahar Province," April 13, 2017. http://www.rs.nato.int/article/transcripts/opening-remarks-by-general-john-nicholson-commander-u.s.-forces-afghanistan-regarding-april-13.html. |

| 21. |

Ibid. |

| 22. |

"Stoltenberg: NATO May Send Many More Troops to Afghanistan," Associated Press, May 10, 2017. |

| 23. |

U.S. Army Public Affairs, "Army Creates Security Force Assistance Brigade and Military Advisor Training Academy at Fort Benning," February 16, 2017. |

| 24. |

Lolita C. Baldor, "Army OKs $5K Bonus to Woo Troops into a New Training Brigade," Army Times, May 4, 2017. |

| 25. |

Stephen Tankel, "Back to First Principles: Four Fundamental Questions about Afghanistan," War on the Rocks, May 15, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/05/back-to-first-principles-four-fundamental-questions-about-afghanistan/. |

| 26. |

Douglas Wissing, "Trump Wants a New Afghan Surge. That's a Terrible Idea," Politico, May 6, 2017, http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/05/06/trump-wants-a-new-afghan-surge-thats-a-terrible-idea-215107. |