Sri Lanka: Background, Reform, Reconciliation, and Geopolitical Context

Sri Lanka is a nation of geopolitical importance despite its relatively small size. Strategically positioned near key maritime sea lanes that transit the Indian Ocean and link Asia with Europe and Africa, Sri Lanka’s external orientation, in particular its ties to China, are of great interest to nearby India. Some observers view China’s involvement in the Sri Lankan port at Hanbantota to be part of Beijing’s strategy to secure sea lanes through the Indian Ocean.

United States-Sri Lanka relations are expanding significantly, creating new opportunities for Congress to play a role in shaping the bilateral relationship. For example, the United States is increasing its foreign assistance to Sri Lanka while seeking to further develop trade between the two countries. The total foreign assistance request in the FY2017 Congressional Budget Justification for Congress for Foreign Operations is $39,797,000 compared with actual foreign assistance provided in 2015 of $3,927,000. In February 2016, the United States and Sri Lanka held their inaugural Partnership Dialogue, while in April 2016, the governments held their 12th Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) talks. The United States is Sri Lanka’s major export destination. Recent U.S.-Sri Lankan engagement has been prompted in part by a fundamental shift in Sri Lanka’s domestic politics since early 2015. This shift has occurred against the backdrop of the more reconciliatory and reform-oriented approach of President Maithripala Sirisena of the Sri Lankan Freedom party (SLFP) and the “National Unity Government” he formed with Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe of the United National Party (UNP).

Under Sirisena’s predecessor, former President Mahinda Rajapaksa (2005-2015), U.S.-Sri Lankan relations deteriorated, especially during the closing phase of Sri Lanka’s civil war between government troops and the forces of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Ealam (LTTE). The war ended in 2009 after 26 years, having claimed over 70,000 lives. Disagreements between the United States and Sri Lanka stemmed from human rights concerns about how the Sri Lankan government fought the LTTE, particularly at the end of the war.

In presidential and parliamentary elections of January and August 2015, respectively, voters ousted the Rajapaksa regime and brought President Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe to power in what the two major parties call a National Unity Government. Some observers assert that this significant reorientation of the Sri Lankan government has created opportunities for Colombo to restore and enhance the country’s democracy through constitutional and political reform and achieve reconciliation with the Tamil minority. President Sirisena’s government has also sought to rebalance its relationship with China.

Human rights concerns remain, especially those related to implementing United Nations-supported transitional justice measures. Progress has been made in a number of areas including, for example, measures to create an office of missing persons and freedom of information legislation, but some observers indicate that more needs to be done to achieve lasting reconciliation with the Tamil minority. They deem such reconciliation to be necessary if Sri Lanka is to attain long-term peace and stability.

As Congress considers legislation and exercises oversight of policy related to Sri Lanka, Members and committees may consider a number of questions. Is Sri Lanka’s strategic significance such that the United States has an interest in developing stronger bilateral ties with Colombo? What is the nature of Sri Lanka’s political and constitutional reform process? Should the U.S. continue to provide democracy assistance? If so, how can it be most effectively structured? Is the Sirisena government’s progress on ethnic reconciliation sufficient to justify enhanced collaboration and increase U.S. foreign assistance, or should such assistance be withheld pending further improvement in this area? Is there a danger that by pushing Colombo too hard on ethnic reconciliation the U.S. and the international community could unintentionally limit the Sirisena government’s political room for maneuver to achieve moderate efforts of reconciliation or political reform? What are China’s strategic interests in Sri Lanka and the Indian Ocean region? Are these potentially a challenge to United States interests?

Sri Lanka: Background, Reform, Reconciliation, and Geopolitical Context

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview

- Background

- Historical Setting

- Civil War and Aftermath

- Domestic Politics

- Structure of Government

- Political Dynamics

- Main Political Parties

- Sinhalese-Buddhist Ideology

- Reform Process and the Constitutional Assembly

- Human Rights, Reconciliation, and Transnational Justice

- The United Nations, Sri Lanka, and Human Rights

- Transitional Justice and Reconciliation

- Environment and Natural Disasters

- Economy

- Geopolitical Context

- Sri Lanka's Relations with India

- Sri Lanka's Relations with China

- U.S.-Sri Lanka Ties

- Foreign Assistance

- Democracy Assistance

- Bilateral Military Ties

- Questions for Congress

Tables

- Table 1. Sri Lankan Political Parties and Their Electoral Performance in 2015

- Table 2. U.S. Foreign Assistance to Sri Lanka

- Table A-1. Recent Sri Lankan Presidential Elections

- Table A-2. Sri Lanka Parties and Their Electoral Performance in 2015

- Table A-3. Sri Lanka Parties and Their Electoral Performance in 2010

- Table A-4. Sri Lanka Parties and Their Electoral Performance in 2004

- Table A-5. Sri Lanka Parties and Their Electoral Performance in 2001

Summary

Sri Lanka is a nation of geopolitical importance despite its relatively small size. Strategically positioned near key maritime sea lanes that transit the Indian Ocean and link Asia with Europe and Africa, Sri Lanka's external orientation, in particular its ties to China, are of great interest to nearby India. Some observers view China's involvement in the Sri Lankan port at Hanbantota to be part of Beijing's strategy to secure sea lanes through the Indian Ocean.

United States-Sri Lanka relations are expanding significantly, creating new opportunities for Congress to play a role in shaping the bilateral relationship. For example, the United States is increasing its foreign assistance to Sri Lanka while seeking to further develop trade between the two countries. The total foreign assistance request in the FY2017 Congressional Budget Justification for Congress for Foreign Operations is $39,797,000 compared with actual foreign assistance provided in 2015 of $3,927,000. In February 2016, the United States and Sri Lanka held their inaugural Partnership Dialogue, while in April 2016, the governments held their 12th Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) talks. The United States is Sri Lanka's major export destination. Recent U.S.-Sri Lankan engagement has been prompted in part by a fundamental shift in Sri Lanka's domestic politics since early 2015. This shift has occurred against the backdrop of the more reconciliatory and reform-oriented approach of President Maithripala Sirisena of the Sri Lankan Freedom party (SLFP) and the "National Unity Government" he formed with Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe of the United National Party (UNP).

Under Sirisena's predecessor, former President Mahinda Rajapaksa (2005-2015), U.S.-Sri Lankan relations deteriorated, especially during the closing phase of Sri Lanka's civil war between government troops and the forces of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Ealam (LTTE). The war ended in 2009 after 26 years, having claimed over 70,000 lives. Disagreements between the United States and Sri Lanka stemmed from human rights concerns about how the Sri Lankan government fought the LTTE, particularly at the end of the war.

In presidential and parliamentary elections of January and August 2015, respectively, voters ousted the Rajapaksa regime and brought President Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe to power in what the two major parties call a National Unity Government. Some observers assert that this significant reorientation of the Sri Lankan government has created opportunities for Colombo to restore and enhance the country's democracy through constitutional and political reform and achieve reconciliation with the Tamil minority. President Sirisena's government has also sought to rebalance its relationship with China.

Human rights concerns remain, especially those related to implementing United Nations-supported transitional justice measures. Progress has been made in a number of areas including, for example, measures to create an office of missing persons and freedom of information legislation, but some observers indicate that more needs to be done to achieve lasting reconciliation with the Tamil minority. They deem such reconciliation to be necessary if Sri Lanka is to attain long-term peace and stability.

As Congress considers legislation and exercises oversight of policy related to Sri Lanka, Members and committees may consider a number of questions. Is Sri Lanka's strategic significance such that the United States has an interest in developing stronger bilateral ties with Colombo? What is the nature of Sri Lanka's political and constitutional reform process? Should the U.S. continue to provide democracy assistance? If so, how can it be most effectively structured? Is the Sirisena government's progress on ethnic reconciliation sufficient to justify enhanced collaboration and increase U.S. foreign assistance, or should such assistance be withheld pending further improvement in this area? Is there a danger that by pushing Colombo too hard on ethnic reconciliation the U.S. and the international community could unintentionally limit the Sirisena government's political room for maneuver to achieve moderate efforts of reconciliation or political reform? What are China's strategic interests in Sri Lanka and the Indian Ocean region? Are these potentially a challenge to United States interests?

Overview

Congress's role in the United States' relationship with Sri Lanka is not limited exclusively to oversight of the Administration's policy. Congress's role also includes decisions on a range of legislative issues including foreign assistance funding for democracy promotion, good governance, ethnic and religious reconciliation, demining, foreign military financing, and other measures. In this context, Sri Lanka may be of increasing interest to Members as the country's progress on constitutional and democratic reforms and ethnic reconciliation unfolds in the year ahead. One question that may trigger increased congressional interest, for example, is whether what some observers may see as inadequate progress in furthering ethnic reconciliation should inhibit the United States' further developing bilateral relations, especially at a time when China has been seeking to develop and expand its trade, investment, and geopolitical influence in Sri Lanka and the broader Indian Ocean region. This report provides the context within which Congress will make both programmatic and oversight decisions, covering questions such as: What is the nature and direction of Sri Lanka's political landscape and democratic reform process? What is Sri Lanka's geopolitical position in the Indian Ocean region? What are the primary considerations Congress should have in mind as it addresses decisions related to Sri Lanka? Should Congress place requirements on the new Administration as it develops its policy toward Sri Lanka?

|

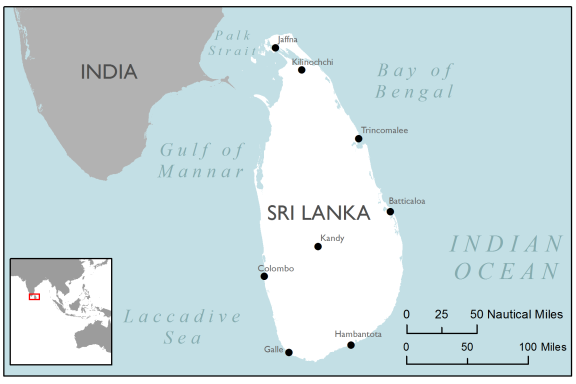

|

Source: Map graphic created by CRS. Map information generated by Hannah Fischer using data from Department of State (2015) and Esri (2014). |

Background1

Historical Setting

The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, known as Ceylon until 1972, is a constitutional democracy in South Asia with relatively high levels of development. It is an island nation located in the Indian Ocean off the southeastern tip of India's Deccan Peninsula. Sri Lanka was settled by successive waves of migration from India beginning in the 5th century BC. Indo-Aryans from northern India established Sinhalese Buddhist kingdoms in the central part of the island. Tamil Hindus from southern India also settled in northeastern coastal areas and established a kingdom on the Jaffna Peninsula. Beginning in the 16th century, Sri Lanka was colonized in succession by the Portuguese, Dutch, and English.

Although Ceylon gained its independence from Britain peacefully in 1948, succeeding decades were marred by ethnic conflict between the country's Sinhalese majority, clustered in the densely populated south and west, and a largely Hindu Tamil minority living in the northern and eastern provinces. Following independence, the Tamils increasingly found themselves as objects of discrimination by the Sinhalese-dominated government, which made Sinhala the sole official language and gave preferences to Sinhalese in university admissions and government jobs. The Sinhalese, who had deeply resented British favoritism toward the Tamils,2 saw themselves not only as a domestic majority, however, but also as a minority in a larger geographic context that includes over 60 million Tamils across the Palk Strait in India's southern state of Tamil Nadu and elsewhere in India.3

Civil War and Aftermath

From 1983 to 2009, Sri Lanka's political, social, and economic development was constrained by ethnic conflict and war between the government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), also known as the Tamil Tigers. The war claimed over an estimated 70,000 lives.4 The LTTE rebels had sought to establish a separate state or internal self-rule in the Tamil-dominated areas of the islands' north and east, and the United States designated the LTTE as a Foreign Terrorist Organization in 1997.

After a violent end to the civil war in May 2009, when the military crushed LTTE forces and precipitated a humanitarian emergency in Sri Lanka's Tamil-dominated north, significant international attention turned to whether the government had the ability and intention to build a stable peace in Sri Lanka.5

|

Sri Lanka at a Glance Capital: Colombo Head of State: President Maithripala Sirisena, elected January 2015 Natural hazards: Tsunami Area: 25,332mi2 (slightly larger than West Virginia) Ethnic groups: Sinhalese 74.9%, Sri Lankan Tamils 11.2%, Moors 9.2%, Indian Tamils 4.2% (2012) est. Religion:. Buddhist 70.2%, Hindu 12.6%, Muslim 9.7%, Christian 6.1% (2012) est. Per Capita GDP: $12,154 in purchasing power parity terms (2016) est. Sources: CIA World Factbook, Economist Intelligence Unit, and media reports. |

President Mahinda Rajapaksa, elected in 2005, faced criticism for what political opponents deemed to be an insufficient response to reported war crimes, a nepotistic and ethnically biased government, increasing restrictions on media, and uneven economic development.6 In January 2015 presidential elections he was challenged from within his own party and defeated by now President Maithripala Sirisena. This result was affirmed in parliamentary elections later in 2015 that led to the formation of the National Unity Government. (See below for more information on political parties.) President Sirisena has pledged to reduce the authority of the executive presidency and has ushered in a period of constitutional and political reform.

Domestic Politics

Structure of Government

Sri Lanka ("the resplendent island" in Sanskrit) has an executive presidency with a unicameral 225-member parliament. Members of Parliament (MPs) are elected for five-year terms under a modified proportional electoral system. The next parliamentary and presidential elections are due in 2020. The president is elected for a five-year term by universal suffrage.7 The president may serve a maximum of two terms. The president may also dissolve parliament four-and-a-half years after the start of the current parliamentary session. The 13th amendment to the constitution, passed in 1987, calls for devolution of central powers to nine directly elected provincial councils. This amendment, which was designed to meet Tamil demands for autonomy, has not been fully implemented.8

Political Dynamics

Sri Lanka is in the midst of a constitutional reform process that has the potential to transform its political system and reinvigorate its democracy. Freedom House, a U.S.-based nongovernmental organization focused on democracy and human rights, noted in 2016 improved civil liberties and political rights. It gave Sri Lanka an upward trend arrow "due to generally free and fair elections for president in January and parliament in August [2015], and improved conditions for freedom of expression, religious freedom, civil society, and judicial independence under the new administration."9

Main Political Parties

|

President Maithripala Sirisena Maithripala Sirisena was born in 1951 in the village of Yagoda north of Colombo. He is a member of the Buddhist Sinhalese community and was elected to parliament in 1989. Sirisena became General Secretary of the SLFP in 2001 and Leader of the House of Parliament in 2004. He was elected President in 2015 with 51.28% of the vote. Sirisena was Health Minister in the Rajapaksa government before running against Rajapaksa. He has described himself as a Socialist. He campaigned against corruption and nepotism and has pledged himself to limit the powers of the presidency and to promote and strengthen parliament and the judiciary.10 |

Sri Lankan politics is dominated by the right-of-center United National Party (UNP) and the socialist Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP).11 The current government is a national unity government of Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe's UNP and President Sirisena's SLFP.12 The SLFP is expected to split, as a rival faction within the party loyal to former President Rajapaksa has formed the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (Sri Lanka People's Front).13 Observers expect this development to place strains on the coalition and weaken the president.14

The Tamil National Alliance (TNA) is the main umbrella political organization representing Tamil interests, and favors greater devolution of power to the provinces.15 The People's Liberation Front, or Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), is a Marxist-Leninist party, and the smaller Sri Lanka Muslim Congress party represents Sri Lankan Muslims who are generally located in the country's east. The United Peoples Freedom Alliance (UPFA) is a political alliance that includes the SLFP and a number of smaller political parties. The national unity government was initially declared in 2015 for a period of two years, but in July 2016 this was extended to the full five-year term.16

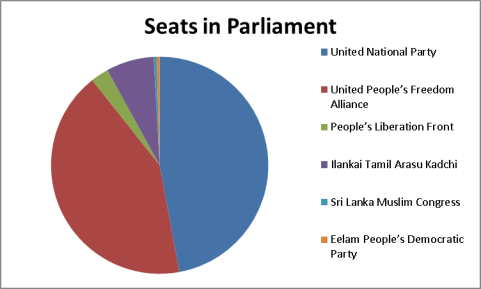

Some observers see a high likelihood that, over the next year, political tensions will rise over a lack of devolution of power to the provinces.17 Figure 2 and Table 1 identify the vote received and parliamentary seats for each party.

|

|

Source: International Foundation for Electoral Systems Election guide http://www.electionguide.org. |

|

Party |

Percentage of Vote |

Seats in Parliament |

|

United National Party |

45.66% |

106 |

|

United People's Freedom Alliance |

42.38% |

95 |

|

People's Liberation Front |

4.98% |

6 |

|

Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kadchi |

4.62% |

16 |

|

Sri Lanka Muslim Congress |

0.4% |

1 |

|

Eelam People's Democratic Party |

0.3% |

1 |

Source: International Foundation for Electoral Systems Election guide, http://www.electionguide.org/elections/id/2871/.

Sinhalese-Buddhist Ideology

Buddhist religious and Sinhalese ethnic identity are key components of political ideology in Sri Lanka: "Buddhism was highlighted as the essence of the Sinhala identity by the ideologues of the [Buddhist] revival" of the mid-19th century. According to this ideology, all of Sri Lanka is considered the homeland of the Sinhalese Buddhists.18 The ideology, according to one prominent analyst, emphasizes "the need to guard Sinhalese people and Buddhism against alien forces."19

Today, Buddhist-Sinhalese nationalism remains a powerful political force in Sri Lanka.20 While many Sinhalese "are amenable to sharing power with the minorities, nationalistic forces within the community continue to subsume moderate voices."21 Many observers in the West, whose understanding of Buddhism may be shaped at least in part by exposure to the teachings of Buddhist leaders such as the Dalai Lama among others, may be unfamiliar with ethno-nationalistic, and at times militant, forms of Buddhism that are used as a mobilizing ideology in Sri Lanka among other places.22

Contemporary Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalist groups, such as Sinha Le ("Lion's Blood") and Bodu Bala Sena (BBS "Buddhist Power Force"), continue to exert political influence in Sri Lanka. This is of importance to the current political scene, as the presence of such groups may make it more difficult to achieve reconciliation with the Tamil community. Sinha Le reportedly plays on fears in the Sinhalese community that Sinhalese-Buddhist culture is under threat and that the Tamil agenda represents an existential threat to Sri Lanka.23 In the words of one analyst,

[I]t is imprudent, perhaps even dangerous, to ignore Sinha Le's appeal among some within Sri Lanka's Sinhala-Buddhist majority. Sinha Le's burst of popularity, combined with BBS's outspokenness on a range of concerns, speak to an undercurrent of ethnic tension that, if left unheeded, may present a greater obstacle to Sri Lanka's tenuous road to reconciliation and the government's transitional justice commitments. This tension becomes apparent when considering the contentious subject of power sharing or devolution in Sri Lanka's post war environment and the government's reconciliation agenda.24

Within this context, Congress may consider the view of some observers that applying pressure on Sri Lanka for rapid accommodation of Tamil demands as part of the transitional justice agenda may prove to be counterproductive by undermining political support for the Sirisena government from within the Sinhalese community. From this perspective, such a situation might open the way for another government that could prove to be less open to ethnic reconciliation or political reform.

Reform Process and the Constitutional Assembly

President Sirisena campaigned on a promise of reducing the powers of the executive presidency and returning Sri Lanka to a parliamentary democracy.25 In April 2015, the Sri Lankan parliament passed the 19th amendment to the Constitution, which reduces the powers of the executive presidency. The amendment reduces the terms of office for the president and parliament to five years, from six previously. It also reintroduces the two-term limit for president and allows the president to dissolve parliament only after four-and-a-half years instead of after one year, as was previously the case. The amendment also revives the Constitutional Council and allows the establishment of independent commissions. The Constitutional Council appoints members to the independent commissions.26 Sirisena has indicated he favors further devolution of presidential powers to the parliament.27

In March 2016, the Parliament adopted a resolution to take on the role of Constitutional Assembly to draft a new constitution. It is considering a number of reforms, including the abolition of the executive presidency.28 The Prevention of Terrorism Act, under which police can detain suspects for extended periods without filing charges against them, is also under review.29 The Tamil National Alliance is looking for a "federal solution within an undivided Sri Lanka based on a merger of the north and eastern provinces."30 Opposition to the constitutional resolution led to the removal of a preamble that discussed providing a constitutional resolution of the Tamil question.31

In June 2016, Parliament passed the Right to Information Bill, which gives citizens access to public information in Sri Lanka. This increased transparency in government has been a key objective of civil society and the media for many years. Many observers hope it will aid in the fight against corruption. Passage of the bill was also one of President Sirisena's 2015 campaign pledges.32

In August 2016, the Sri Lankan Parliament passed legislation to allow the creation of an Office of Missing Persons. This step is viewed by many observers as one of the key pillars of transitional justice in Sri Lanka.33 According to one report, there may be as many as 16,000 to 22,000 people who went missing during the civil war and its aftermath.34 Reportedly there was a campaign to block passage of the missing persons bill, with former President Rajapaksa reportedly stating that those who support the legislation would betray the armed forces of the country.35

By the end of 2016, it appeared that Tamil reconciliation measures and the abolition of the executive presidency remained politically contentious. The Constitutional Assembly (CA) will consider reports from the six CA subcommittees on Fundamental Rights, Judiciary, Finance, Public Service, Law and Order, and Centre-Periphery Relations.36 The subcommittee on center-periphery relations proposed on November 22, 2016, that land and police powers should be devolved to the provinces in the new constitution.37 This recommendation, which is consistent with the 13th amendment, would likely be supported by the Tamil minority as an effort toward reconciliation. Despite this, it is not clear if the measure has sufficient political support to be included in the final draft of the constitution, which must be passed by a two-thirds majority in parliament and be approved in a national referendum to be adopted. Some observers believe the UNP could opt to retain some aspects of the executive presidency in the new constitution.38

While some reforms have been achieved, some analysts have observed that "the moderate consensus" to effect further reforms "remains deeply vulnerable."39 Former President Rajapaksa, who continues to have a strong following among SLFP Members of Parliament, remains a divisive figure. For some, he is seen as the leader who brought victory over the Tamil insurgency, while others consider him leader of a corrupt and nepotistic government that committed human rights abuses.40 Future constitutional reforms require a two-thirds majority vote in Parliament as well as passage in referendum. According to one analyst, the Rajapaksa faction "cannot be ignored in matters of state because of its parliamentary strength and thus its potential ability to stall the implementation of basic reforms in constitutional governance."41

Human Rights, Reconciliation, and Transnational Justice

The United Nations, Sri Lanka, and Human Rights

Sri Lanka cosponsored a U.N. Human Rights Council resolution on accountability for human rights abuses during the Sri Lanka civil war that was adopted in October 2015. The resolution followed the September 2015 publication of the Report of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Investigation on Sri Lanka, which undertook an investigation into alleged serious violations and abuses of human rights and related crimes by both parties in Sri Lanka, and was viewed by many observers as a positive step to advance justice in Sri Lanka.

|

U.N. Report: End of War Atrocities "The report has shown that during the last phases of the armed conflict, the intense shelling by the armed forces caused great suffering and loss of life among the civilian population in the Vanni. Witnesses gave harrowing descriptions to OISL of the carnage, bloodshed and psychological trauma of bombardments in which entire families were killed. Lack of food, water and medical treatment because of strict controls of supplies allowed into the Vanni by the Government further impacted on their well-being and undoubtedly caused additional deaths. The LTTE caused further distress by forcing adults and children to join their ranks and fight on the front lines. The fact that the civilians were forced to remain in the conflict area by the LTTE and suffered reprisals if they tried to leave added to the trauma that they lived through." Source: Report of the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL), United Nations Human Rights Council, September 16, 2015. |

Since the adoption of the resolution, President Sirisena has appeared to back away from what seemed to be his earlier support for the involvement of international judges in a special judicial mechanism to prosecute war crimes. He reportedly has stated that, "This investigation should be internal.... I believe in the judicial system ... we have more than enough specialists, experts and knowledgeable people in our country to solve our internal issues."42 According to Human Rights Watch, however, "While the proposed resolution does not specifically call for a hybrid national-international justice mechanism, if fully implemented it offers a greater hope for justice than past failed promises by the Sri Lankan government on justice for human rights abuses."43 In June 2016, High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein noted steps taken by Sri Lanka, as mentioned above, but also called for a transitional justice mechanism to deal with past human rights abuses.44

Transitional Justice and Reconciliation45

The civil war left a great rift in Sri Lankan society, and the previous Rajapaksa regime did little to heal the wounds left by the war. The Sirisena government has done more, such as allowing the national anthem to be sung in Tamil,46 returning some lands taken from Tamils during the war, lifting a ban on Tamil groups, and creating an office of missing persons. Tamil groups, however, are demanding more.

Many observers believe long-term peace and harmony between the Sinhalese majority and the Tamil minority necessitates a reconciliation of grievances. In a general sense, the Tamil community seeks recognition of its place within Sri Lankan society. Many Tamils would like increased autonomy, implementation of the 13th amendment (which would devolve power to the provinces), the return of all Tamil lands taken during the civil war, an inquiry into human rights abuses by the government during the war, and expanded government assistance with missing persons. While observers have credited the Sirisena government with opening up political debate, ending the authoritarian rule that pervaded under Rajapaksa, and limiting some presidential powers, one source notes that "... the depths of nationalist sentiment and party politics have put sharp limits on what they [the Sirisena government] have been willing to do to address key matters, including the concerns of Sri Lankan Tamils and Muslims."47

The United Nations, the international nongovernmental organization community, and the international media have focused considerable attention on obtaining international participation in a war crimes tribunal process. U.S assistance to Sri Lanka seeks to assist the government of Sri Lanka in its efforts to "broaden and accelerate economic growth, develop democratic institutions, and promote the reconciliation of multi-ethnic and religious communities in Sri Lanka."48

Environment and Natural Disasters

The challenges facing Sri Lanka today are not limited to the political realm. Deforestation has been a serious problem with negative implications for global climate change and biodiversity.49 Deforestation is responsible for an estimated 10%-12% of all global warming emissions.50 According to one source, Sri Lanka's forest cover was depleted from 31.2% of the island in 1999 to 29.7% in 2010 with actual rates of forest depletion slowing to 0.23% of forest cover annually.51 The Forest Department has set a goal of 35% forest cover for Sri Lanka by 2020.52 Sri Lanka is one of the most biologically diverse nations in Asia, and an estimated one-quarter of tourists visiting the country visit one of Sri Lanka's national parks.53 Sri Lanka instituted a ban on logging of natural forests in 1990.54

Sri Lanka also was devastated by the December 26, 2004, tsunami caused by a 9.1 magnitude earthquake off Sumatra that affected 14 countries in the Indian Ocean region. As many as 40,000 people may have died in Sri Lanka as a result of the tsunami.55 The economic damage and loss to Sri Lanka was estimated to be as much as $1.45 billion, and an estimated 400,000 workers in Sri Lanka lost their means of livelihood as fishing boats as well as banana, rice, and mango plantations, and houses and infrastructure were destroyed.56

Economy

The Sri Lankan economy is on less solid footing in 2016 than it was previously. Sri Lanka experienced high rates of economic growth in the immediate post-war period due to increased investment and high rates of remittances from Sri Lankans working abroad. Interest payments on government debt accounted for 35% of government revenue and the budget deficit widened to 7.4% of GDP in 2015. Government debt was also 76% of GDP in 2015.57 GDP growth is projected to be 5.1% in 2016 and average an annual rate of 5.2% for the period 2016-2020.58

The government's policies of increasing salaries and pensions for public servants and cutting taxes despite a slowing economy contributed to the balance of payments crisis. Sri Lanka requested IMF support and received an IMF bailout package of $1.5 billion in March 2016. This package will require the government to increase tax revenues and cut the budget deficit.59 In June 2016, it was reported that the government will seek to raise the tax-to-GDP ratio from 10.8% in 2014 to 15% by 2020 through a new Inland Revenue Act, reform of the value added tax, and the customs code.60 Remittances are a significant part of Sri Lanka's economy. Remittance growth declined from 9.5% in 2014 to 0.8% in November 2015. One possible explanation for this was optimism for investment immediately following the end of the war. An estimated 55% of Sri Lanka's $3.8 billion in remittances in 2014 came from the Middle East. Approximately one-quarter of Sri Lanka's total migrant workers are employed in Saudi Arabia.61

Geopolitical Context

Sri Lanka is situated near strategically important sea lanes that transit the Indian Ocean. These sea lanes link the energy-rich Persian Gulf with the economies of Asia. The inaugural United States Sri Lanka Partnership Dialogue in February 2016 discussed Sri Lanka's "pivotal geo-strategic location within the Indian Ocean region and how to strengthen cooperation on issues of regional importance."62 More than 60,000 ships carrying 66% of the world's oil and 50% of the world's container shipments transit the sea lanes near Sri Lanka and the Maldives each year.63

Sri Lanka's Relations with India

Sri Lanka and India share close, long-standing historical, cultural, and religious ties. India became entangled in the counterinsurgency against the LTTE following the signing of the Indo-Sri Lanka Agreement of 1987. Between 1987 and 1990, India, which originally intended to operate in a peacekeeping role, lost over 1,200 soldiers in this conflict. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was later killed by a LTTE suicide bomber in 1991.

The Sri Lanka-India relationship was strengthened by President Sirisena's February 2015 visit to New Delhi, his first foreign visit as President, and also by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's March 2015 visit to Colombo, the first by an Indian prime minister in 29 years. During his visit, Modi articulated his government's desire that the Tamil community in Sri Lanka have a just and dignified life in a unified Sri Lanka. Modi also pledged India's help to Sri Lanka in its efforts to develop an oil-shipping hub and construct a power plant, and to provide access to $300 million in funding to improve railways. India's native Tamil populations feel kinship with Sri Lanka's Tamils. India, along with the United States, has been an active voice for reconciliation and fair elections. India has also played host to large numbers of Tamil refugees both during and after the Sri Lankan civil war. Some observers in India have expressed concern over Sri Lanka's relationship with China, including past Chinese submarine visits to Sri Lanka.64

Sri Lanka's Relations with China

Sri Lanka and China issued a joint statement at the conclusion of Prime Minister Wickremesinghe's April 2016 visit to China. In the statement, the two nations declared their commitment to "mutually beneficial cooperation" and expressed their "willingness to maintain close relations between the two countries in the area of defense." Sri Lanka also "reiterated its active participation in the Belt and Road initiative put forward by China."65

China's activities in Sri Lanka are considered to be part of what it calls its 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, which is part of its One Belt One Road initiative, aimed in part at gaining access to ports in the Indian Ocean to help secure China's interests along vital sea lanes.66 For its part, Sri Lanka seeks to become a key Indian Ocean regional economic hub. The scale of Sri Lanka's indebtedness to China may give China a degree of leverage over Sri Lanka that could translate into support for Chinese foreign policy initiatives. Such support will likely be balanced against Indian and Western concerns.67

China's relations with former President Rajapaksa deepened in the final years of the civil war as Sri Lanka's relationship with India and the West became strained. One analyst argued, "China's weapons support to Sri Lanka was critical to the government's defeat of the LTTE when Western countries and India refused to supply arms."68 China supplied ammunition and ordinance, as well as six F-7 jet fighters, antiaircraft guns, a radar system, and other assistance.69

This bilateral relationship continued to grow under President Rajapaksa in the post-war period. The visit by Chinese submarines in 2014 to Colombo raised concerns in New Delhi. The submarines reportedly docked at a terminal designed and operated by the Chinese.70

The Rajapaksa regime had relied heavily on China for investment and military equipment. During the Rajapaksa years, China became Sri Lanka's biggest donor, provided fighter jets, weapons, and radars to the Sri Lankan military, invested in a major $1.4 billion Port City Project in Colombo, and pledged to invest $1 billion to develop the port at Hambantota. Sri Lanka's willingness to allow Chinese submarines to dock at Colombo's port twice in late 2014 alarmed Indian officials, who are wary of China's increasing influence in its backyard. India fears that Chinese investment in South Asian ports not only serves Chinese commercial interests, but also facilitates Chinese military goals.71

Upon coming to office, the Sirisena government sought to rebalance Sri Lanka's relations with India and China. His government suspended the Chinese-backed Colombo Port City project. After the government's review, the project is now going ahead with some modification. The $1.5 billion Port City project is to be built on 583 acres of reclaimed land in Colombo harbor. In the original deal China was to be granted 20 hectares as freehold land. Under the revised agreement, the land will all be leased by China on a 99-year basis.72 Of the reason for the resumption of the project, Sri Lankan Cabinet Spokesman Rajitha Senaratne stated, "who else is going to bring us money, given tight conditions in the West?"73

Chinese investment in Sri Lanka, in particular for development of the port at Hambantota, has been substantial. China reportedly has loaned Sri Lanka approximately $5 billion, as compared with $1.7 billion by India, over the past decade.74 By some estimates, one-third of Sri Lanka's revenue goes to service this debt. Indian analysts have observed that difficulty in repaying such loans may provide China with an opportunity to turn loans into equity, "making them part owners of vital projects and granting China a new strategic outpost in the Indian Ocean."75

Given these developments in the China–Sri Lanka relationship, Congress may assess the implications of China's influence in Sri Lanka. Is China primarily motivated by economic or strategic goals or both? What is Sri Lanka's place in China's larger One Belt One Road (OBOR) strategy? Should the United States be concerned over rising Chinese influence in Sri Lanka and the Indian Ocean more generally or are these developments to be viewed as a legitimate expression of China's rise and its desire to secure its own sea lines of communication in the region? According to some observers, one possible response to these questions is that, while China's trade and investment activities in Sri Lanka are not a direct threat to American interests, it is not in America's interest to have its, or its friends' and allies', influence marginalized to the point of irrelevance in Sri Lanka given Sri Lanka's strategic position near critical sea lanes. Others are less concerned about these developments.

U.S.-Sri Lanka Ties

Members of Congress and their staff have a range of interests related to Sri Lanka, both general and specific. Generally, Members' interests may include consideration of foreign operations budget requests related to Sri Lanka; potential hearings on bilateral relations, democratic reforms, and trade and investment; the House Democracy Partnership with Sri Lanka; the Congressional Caucus for Ethnic and Religious Freedom in Sri Lanka; ambassadorial confirmation hearings; and meetings with Sri Lankan delegations. More specifically, Congress may be interested in exercising oversight in a number of areas including the Administration's policy toward Sri Lanka with regard to support for democratic reform, ethnic reconciliation, human rights and transitional justice, geopolitics related to India and China in the Indian Ocean region, trade and investment, military-to-military relations, and the environment.

The United States has indicated its support for Sri Lanka's "unity, territorial integrity and democratic institutions" and is a "strong supporter of ethnic reconciliation."76 The United States has also provided over $2 billion in development assistance to Sri Lanka since 1948. The State Department described Sri Lanka's 2015 presidential election as having "ushered in a new political era and opportunity for renewed U.S. diplomatic and development engagement." Secretary of State John Kerry visited Colombo in May 2015 and congratulated Sri Lanka for continuing steps toward reconciliation at the U.S.-Sri Lanka Partnership Dialogue in February 2016.77 During his visit, Secretary of State John Kerry stated

... true peace is more than the absence of war. True and lasting peace, especially after a civil conflict, requires policies that foster reconciliation, not resentment. It demands that all citizens of the nation be treated with equal respect and equal rights, and that no one be made to feel excluded or subjugated.78

In August 2016, United States Ambassador to Sri Lanka Atul Keshap noted the positive steps taken in a number of other areas:

We applaud the establishment in law of an Office of Missing Persons to help families who still grieve and seek answers. We know the government has committed to establish truth and reconciliation and judicial mechanisms to investigate war crimes; to replace the Prevention of Terrorism Act; to charge or release the remaining security-related detainees; dismantle the culture of surveillance; end discrimination against minorities; return more land; boost an open and free society for journalists and civil society; and promote reconciliation and forge a reconciled, united, peaceful, prosperous Sri Lanka.79

Through its aid and diplomacy the United States has indicated that it supports initiatives that "increase accountability and transparency; protect human rights and fundamental freedoms; strengthen rule of law and democratic institutions; increase security and stability; promote reconciliation, interfaith harmony, and interethnic understanding; and bolster good governance and economic growth."80

The United States and Sri Lanka have a strong trade relationship. The United States is Sri Lanka's single largest market with approximately 25% of the nation's exports reaching the United States. Sri Lanka's largest exports are garments, tea, spices, rubber, gems and jewelry, refined petroleum, fish, and coconuts/coconut products. Other large trading partners include neighboring India and several European Union nations.81 While China is not one of Sri Lanka's largest trade partners, it is a growing investment partner.

In December 2015, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) Board of Directors selected Sri Lanka as eligible to develop a threshold program. MCC threshold program assistance supports government efforts at reform. The United States and Sri Lanka adopted a Joint Action Plan to boost bilateral trade at the 12th U.S.-Sri Lanka Trade and Investment Framework (TIFA) meeting in April 2016. U.S. goods exports to Sri Lanka increased 4.7% from 2014 to 2015 and were valued at $372 million.82

The Obama Administration has sought to broaden and deepen the U.S. relationship with Sri Lanka, and the inaugural U.S.-Sri Lanka Partnership Dialogue was held in Washington, DC, in February 2016. The dialogue discussed Sri Lanka's pivotal geostrategic location within the Indian Ocean region as well as economic cooperation, governance, development, and people-to-people ties. The United States expressed its support for Sri Lanka's "plans for constitutional and legislative reform including public consultations on a new constitution and the repeal of the Prevention of Terrorism Act."83

In considering how sensitive U.S. policy should be concerning the Sinhalese Buddhist majority's insecurities relative to Tamil demands for greater autonomy, Congress may assess the possibility, according to some observers, that Western pressure could create opportunities for political factions from within the Sinhalese Buddhist community that would be less likely to adopt reconciliation measures with the Tamil minority should they come to power. On the other hand, it is also argued that without Western pressure the prospects for true ethnic reconciliation are diminished.

Foreign Assistance

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has maintained a presence in Sri Lanka since 1948. The FY2017 Foreign Operations request for United States assistance to Sri Lanka would represent a significant increase over previous funding. U.S. assistance seeks to "support the new Sri Lanka government's reconciliation, reform, and accountability agenda with increased resources and programming to achieve historic advancements in human rights, economic equality, and stability that were inconceivable a year ago."84 Key objectives highlighted in the FY2017 Congressional Budget Justification for Sri Lanka include the following:

- Sri Lanka accelerates reconciliation between the majority population and ethnic and religious minorities with the assistance of U.S. programs.

- With U.S. help and projection of U.S. democratic values, Sri Lanka improves respect for and application of just and democratic governance, human rights, and freedom of expression principles.

- Through U.S. engagement and training Sri Lanka enhances regional security.

- The North, East, and surrounding conflict-affected areas experience accelerated and more equitable economic growth.

- Sri Lanka improves its business climate with greater transparency of government transactions and adherence to macroeconomic principles.

|

FY2015 Actual |

FY2017 Request |

Increase/Decrease |

||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|||

|

Development Assistance |

|

|

|

|||

|

Economic Support Fund |

|

|

|

|||

|

Foreign Military Financing |

|

|

|

|||

|

International Military Education and Training |

|

|

|

|||

|

International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement |

|

|

|

|||

|

Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining and Related Programs |

|

|

|

Source: Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification, Foreign Operations, Appendix 3, FY2017, p. 341. Data for 2016 not available.

Democracy Assistance

In September 2016, the U.S. House Democracy Partnership and the Sri Lankan Parliament launched a collaborative agreement to strengthen partnership between the two legislatures. The collaboration between the legislatures is based on the exchange of information on legislative systems, consultations on legislative management, and training programs for Members and staff.85 USAID programs are aimed at supporting Sri Lanka's democratic process in a number of ways:

USAID programming strengthens the rule of law, builds a robust civil society and promotes reconciliation—all of which are prerequisites for long-term stability and prosperity. USAID ensures greater access to justice for all citizens by building the capacity of local civil society and professional legal organizations, providing legal education to professionals, connecting universities and local organizations to develop policy and legal reforms that respond to citizens' needs, and assisting marginalized groups with legal assistance. USAID provides management support, organizational development, financial and project management, and monitoring and evaluation training to local organizations to extend much-needed services to citizens, advocate for their needs and sustain vital services long after donor resources phase out of the country. USAID programs also provide technical assistance to key democratic institutions, including to the Sri Lankan Parliament to improve legislative processes and practices and to the Election Commission to ensure continued free and fair elections.86

Bilateral Military Ties

Previous military trade restrictions on Sri Lanka were eased in 2016. The U.S. Department of State's Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC) announced on May 4, 2016, that licensing restrictions on defense exports to Sri Lanka were lifted and that it would review future license applications on a case-by-case basis under usual International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR). The previous restrictions on defense exports to Sri Lanka had been removed from the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016.87

U.S.-Sri Lankan military-to-military ties are expanding as part of the overall improvement in bilateral ties. During the July 2016 naval visit of the USS New Orleans, with its embarked 13th Marine Expeditionary Unit, U.S. Ambassador to Sri Lanka Keshap stated "the 21st century is in many ways the Indo-Pacific century, and Sri Lanka is well-positioned to take advantage of its strategic location.... [T]he United States looks forward to working with the Sri Lankan navy as a force for maritime security and stability."88 U.S. Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus visited the Sri Lankan navy dockyard in Trincomalee to view ongoing bilateral training between the U.S. and Sri Lankan navies in August 2016.89 Operation Pacific Angel, a Pacific Command-led multinational humanitarian assistance operation, provided medical care for 4,000 people and renovated six schools in August 2016 as well.90

Questions for Congress

Looking forward, Congress may consider a number of questions as it considers legislation and exercises oversight of policy related to Sri Lanka:

- Does Sri Lanka's strategic significance merit stronger bilateral ties with Colombo?

- What is the nature of Sri Lanka's political and constitutional reform process? Should the United States continue to provide democracy assistance?

- How sensitive should U.S. policy be to the Sinhalese Buddhist majority's insecurities relative to Tamil demands for greater autonomy? What are the policy implications of the Sirisena government's level of sensitivity?

- Is the Sirisena government's progress on ethnic reconciliation sufficient to justify enhanced collaboration and increase U.S. foreign assistance or should such assistance be diminished pending further improvement in this area?

- Is there a danger that by pushing Colombo too hard on ethnic reconciliation the United States and the international community could unintentionally limit the Sirisena government's political room for maneuver to achieve moderate efforts of reconciliation?

- What are China's strategic interests in Sri Lanka and the Indian Ocean region? Are these potentially a threat to U.S. interests? How do they relate to India's strategic interests?

Congress may choose to reevaluate U.S. assistance programs toward Sri Lanka as the new Administration develops its policy and as events unfold in Sri Lanka. The new Administration may, or may not, seek funding for policy objectives which may differ with current policy objectives. Events in Sri Lanka may also affect congressional decisionmakers' attitudes toward funding decisions as progress is, or is not, made in a number of areas of importance to Members.

Chronology91

|

5th century BC |

Migrants from India establish the Sinhalese in Sri Lanka. |

|

3rd century BC |

Beginning of Tamil migration from India. |

|

1505 |

Portuguese influence in Ceylon begins. |

|

1658 |

Dutch displace the Portuguese and establish control over coastal regions. |

|

1796 |

British influence begins. |

|

1815 |

British take Kandy and bring Tamil laborers from India to work on plantations. |

|

1833 |

British consolidate their administration. |

|

1948 |

Ceylon gains full independence. |

|

1949 |

Indian Tamil plantation workers disenfranchised, many deprived of citizenship. |

|

1956 |

Solomon Bandaranaike elected on wave of Sinhalese nationalism. Sinhala made sole official language. More than 100 Tamils killed in widespread violence. |

|

1958 |

Anti-Tamil riots kill over 200. |

|

1971 |

Sinhalese Marxist uprising led by students and activists. |

|

1972 |

Ceylon changes its name to Sri Lanka. Buddhism given primary place. |

|

1976 |

Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) formed. |

|

1983 |

Anti-Tamil riots lead to the deaths of several hundred Tamils and conflict. |

|

1987 |

Indo-Sri Lanka Accord, Indian peacekeeping force deployed. |

|

1988 |

Left-wing Sinhalese JVP begins campaign against Indo-Sri Lankan agreement. |

|

1990 |

Indian troops leave and conflict with Tamils resumes. |

|

1991 |

LTTE implicated in assassination of Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. |

|

1993 |

President Premadasa killed in LTTE bombing. |

|

1994 |

President Kumaratunga comes to power pledging to end war. Peace talks opened. |

|

1995-2001 |

War continues in north and east. |

|

2002 |

Government and Tamil Tiger rebels sign a Norwegian-mediated cease-fire. |

|

2003 |

Tigers pull out of talks. |

|

2004 |

More than 30,000 people are killed by a tsunami. |

|

2005 |

Mahinda Rajapaksa wins presidential elections. |

|

2006 |

Conflict escalates. |

|

2009 |

Government troops capture the northern town of Kilinochchi. International concern mounts as thousands of civilians are trapped by the fighting. United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay accuses both sides of war crimes. Tamil Tigers are defeated and LTTE leader Prabhakaran is killed. |

|

2010 |

Rajapaksa wins presidential election and his coalition wins a landslide victory in parliamentary elections. Parliament approves a constitutional change allowing President Rajapaksa to seek unlimited number of terms. |

|

2011 |

The U.N. asserts both government and LTTE forces committed atrocities and calls for an international investigation into possible war crimes. |

|

2012 |

UNHRC resolution urges Sri Lanka to investigate war crimes allegedly committed during the final phase of the war. |

|

2014 |

Rajapaksa says a U.N. team will not be allowed to enter Sri Lanka. |

|

2015 |

Maithripala Sirisena becomes president. |

Appendix. Presidential and Parliamentary Election Results

|

Year |

Party |

President |

Percentage of Vote |

|

2015 |

United National Party |

Maithripala Sirisena |

51.28% |

|

2010 |

United People's Freedom Alliance |

Mahinda Rajapaksha |

57.88% |

|

2005 |

United People's Freedom Alliance |

Mahinda Rajapaksha |

50.29% |

|

1999 |

People's Alliance |

Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga |

51.12% |

Source: "Election Guide Democracy Assistance and Elections News," Washington DC, 2016, http://www.electionguide.org/elections/id/2813/.

|

Party |

Percentage of Vote |

Seats in Parliament |

|

United National Party |

45.66% |

106 |

|

United People's Freedom Alliance |

42.38% |

95 |

|

People's Liberation Front |

4.98% |

6 |

|

Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kadchi |

4.62% |

16 |

|

Sri Lanka Muslim Congress |

0.4% |

1 |

|

Eelam People's Democratic Party |

0.3% |

1 |

|

Party |

Percentage of Vote |

Seats in Parliament |

|

United People's Freedom Alliance |

60.66% |

144 |

|

United National Party |

29.50% |

60 |

|

Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna |

5.52% |

7 |

|

Tamil National Alliance |

2.92% |

14 |

|

Party |

Percentage of Vote |

Seats in Parliament |

|

United People's Freedom Alliance |

45.60% |

105 |

|

United National Party |

37.83% |

82 |

|

Tamil National Alliance |

6.84% |

22 |

|

National Heritage Party |

5.97 |

9 |

|

Sri Lanka Muslim Congress |

2.02 |

5 |

|

Up Country Peoples Front |

0.54% |

1 |

|

Eelam People's Democratic Party |

0.27 |

1 |

|

Party |

Percentage of Vote |

Seats in Parliament |

|

United National Party |

45.60% |

109 |

|

People's Alliance |

37.20% |

77 |

|

People's Liberation Front |

9.10% |

16 |

|

Tamil United Liberation Front |

3.90% |

15 |

|

Sri Lankan Muslim Congress |

1.2% |

5 |

|

Eelam People's Democratic Party |

0.8% |

2 |

|

Democratic People's Liberation Front |

0.2% |

1 |

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

See also CRS In Focus IF10213, Sri Lanka, by Bruce Vaughn. |

| 2. |

J. Bajoria, "The Sri Lankan Conflict," Council on Foreign Relations, May 18, 2009. |

| 3. |

S. Nanayakkara, "Transformations in Sinhala Nationalism," Economic and Political Weekly, June 4, 2016. |

| 4. |

"Shattered Lives: Sri Lanka's Bloody Civil War," The Economist, November 12, 2014. |

| 5. |

Tens of thousands of Tamil civilians died in the last months of the civil war. Lydia Polgreen, "Sri Lanka Forces Blamed for Most Civilian Deaths," The New York Times, May 16, 2010. |

| 6. |

Taylor Dibbert, "After the Shake Up: Rhetoric vs. Reform in Sri Lanka," World Affairs, Winter 2016. |

| 7. |

K.T. Rajasingham, "Cabinet Reshuffle Is Likely with Dy PM for SLFP, Pressure on President for Equality in Ministerial Berths," Asian Tribune, October 21, 2016. |

| 8. |

"Sri Lanka: Country Report," The Economist Intelligence Unit, July 28, 2016. |

| 9. |

"Sri Lanka," Freedom in the World 2016, https://freedomhouse.org. |

| 10. |

"Introducing Maithripala Sirisena," http://www.dw.com, and "Honorable Maithripala Sirisena," http://www.president.gov.lk. |

| 11. |

Neil DeVotta, "A Win for Democracy in Sri Lanka," Journal of Democracy, January, 2016. |

| 12. |

G. Sen, "The Rajapaksa Factor," Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, http://www.idsa.in/idsacomments. |

| 13. |

"Trouble Ahead for the Government," The Economist Intelligence Unit, December 22, 2016. |

| 14. |

"Party Split Puts President Under Pressure," The Economist Intelligence Unit, November 23, 2016. |

| 15. |

D. Bastians, "Tamil Lawmaker to Lead Opposition," The New York Times, September 3, 2015. |

| 16. |

"Lanka Main Parties Vow to Extend Unity Government," Press Trust of India, July 21, 2016. |

| 17. |

"Sri Lanka Risk: Political Stability Risk," Economist Intelligence Unit, July 7, 2016. |

| 18. |

Rohini Mohan, "Sri Lanka's Violent Buddhists," New York Times, January 2, 2015. |

| 19. |

S. Nanayakkara, "Transformations in Sinhala Nationalism," Economic and Political Weekly, June 4, 2016. |

| 20. |

The Mahavamsa is a key text in Sri Lankan Buddhism. Some observers view the Mahavamsa as playing a role in introducing "a vein of intolerant chauvinism" into Sri Lankan Buddhism. The epic Dutugemumu, which purports to recount events that took place in the late second-century BCE, is found in the Mahavamsa. According to one historian, "[T]he story continues to resonate for many contemporary Sinhalas, who find the defeat or subjugation of the island's Tamils an important dimension, for some paradigmatic, of their social and political identities ... the story symbolizes the prototypical encounter between the Sinhala and Tamil peoples, with Dutugemunu—the arch defender of Buddhism—defeating the Tamil king Elara and his armies to establish Sinhala hegemony for the sake of the religion's well-being." John Clifford Holt, The Sri Lanka Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), p. 30. "How Beijing Won Sri Lanka's Civil War," The Independent, May 22, 2010, http://www.independent.co.uk. |

| 21. |

"Dynamics of Sinhala Buddhist Ethno-nationalism in Post War Sri Lanka," Centre for Policy Alternatives, April 20, 2016, http://www.cpalanka.org. |

| 22. |

There are a number of different classifications of schools of Buddhist thought. Some classify the various schools as falling within the two major schools of Mahayana and Theravada Buddhism. Others add Vajrayana Buddhism, which is associated with Tibetan Buddhism, as a third major school. Theravada Buddhism predominates in Sri Lanka. Barbara O'Brien, "Guide to Major Schools of Buddhism," http://buddhism.about.com. |

| 23. |

Zachary Walko, "Lion's Blood: Behind Sri Lanka's Sinha Le Movement," The Diplomat, June 29, 2016. |

| 24. |

Ibid. |

| 25. |

See, for example, Ellen Barry, "Groundswell Chooses Democracy in Sri Lanka," The New York Times, January 11, 2015. |

| 26. |

"Sri Lanka Constitutional Council Holds Inaugural Meeting," Constitution net, July 6, 2015, http://www.constitutionnet.org. |

| 27. |

Disna Mudalige, "Constitution Making a Collective Effort," Daily News, March 30, 2016. T. Ramakrishnan, "Sri Lanka Adopts the 19th Amendment," The Hindu, April 29, 2015. |

| 28. |

"Governability in the Absence of a Powerful Executive Presidency," Daily FT, January 27, 2016. |

| 29. |

"PTA Reforms," Daily FT, April 21, 2016. |

| 30. |

"Sri Lanka Tamils Look for Federal Solution," Press Trust of India, April 17, 2016. |

| 31. |

T. Ramakrishnan, "Resolution Passed to Convert Sri Lanka Parliament into Constitutional Assembly, The Hindu, March 9, 2016. |

| 32. |

"Parliament Passes Right to Information Bill," Economist Intelligence Unit, June 29, 2016. |

| 33. |

Taylor Dibbert, Sri Lanka will Create an Office of Missing Persons," The Diplomat, August 16, 2016. |

| 34. |

"Sri Lanka Probes UN Claims of Ongoing Police Torture," Agence France Presse, May 11, 2016. |

| 35. |

Raisa Wickrematunge, "The Road to the OMP," Groundviews, August 31, 2016. |

| 36. |

Disna Mudalige, "SLFP, JVP Asked to State Positions Clear," Daily News, January 2, 2017. |

| 37. |

"Constitutional Reforms Come into the Spotlight," The Economist Intelligence Unit, November 24, 2016. |

| 38. |

"Trouble Ahead for the Government," The Economist Intelligence Unit, December 22, 2016. |

| 39. |

G. Anand and D. Bastians, "Can a New President Lead Sri Lanka into an Era of Peace?" The New York Times, May 12, 2016. |

| 40. |

"Sri Lanka: Rajapaksa Legacy of Abuse," Human Rights Watch, January 29, 2015. |

| 41. |

G. Sen, "The Rajapaksa Factor," Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, http://www.idsa.in/idsacomments. Economist Intelligence Unit, Sri Lanka Country Report, April 25, 2016. |

| 42. |

Azzam Ameen, "Sri Lankan President Wants Internal War Crimes Court," BBC News, January 21, 2016. |

| 43. |

"Sri Lanka: UN Resolution Could Advance Justice," Human Rights Watch, September 28, 2015. |

| 44. |

United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner, "Statement by Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, United Nations High Commissioner Human Rights, on the Situation on Sri Lanka and Burma, http://www.ohchr.org. |

| 45. |

The United Nations defines Transitional Justice as "... the full range of processes and mechanisms associated with a society's attempt to come to terms with a legacy of large-scale past abuses, in order to ensure accountability, serve justice and achieve reconciliation." The United Nations also defines key components of Transitional Justice. These are (1) prosecution initiatives, (2) facilitating initiatives in respect of the right to truth, (3) delivering reparations, (4) institutional reform, and (5) national consultations. Guidance Note of the Secretary-General: United Nations Approach to Transitional Justice, United Nations, March 2010. |

| 46. |

"Sri Lanka Celebrates I-Day by Rendering National Anthem in Tamil Too," The Hindu, February 4, 2016. |

| 47. |

"Sri Lanka Between the Elections," International Crisis Group, August 12, 2015. |

| 48. |

U.S. Department of State, Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs, "U.S. Relations with Sri Lanka," April 6, 2016. |

| 49. |

"Forest restoration and sustainable forest management are important measures for mitigating climate change. They also have many additional benefits, including biodiversity conservation, the provision of other ecosystem services, and the alleviation of poverty." "Tropical Forests and Climate Change," International Tropical Timber Organization, September 2008. |

| 50. |

Union of Concerned Scientists, "Tropical Deforestation and Global Warming," http://www.ucsusa.org/global_warming/solutions/stop-deforestation/, and "The Role of Tropical Forests in Climate Change Mitigation," Harvard Project on Climate Change Agreements, April 2013. |

| 51. |

Sri Lanka's Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2014, Ministry of the Environment and Renewable Energy, 2014. Other sources vary slightly "Sri Lanka," Mongabay.com, http://rainforest.mongabay.com/deforestation/archive. |

| 52. |

Johann Rebert, "Deforestation Now Urgent Concern in Post-War Sri Lanka," Asia Foundation, March 16, 2016. |

| 53. |

Sri Lanka's Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2014, Ministry of the Environment and Renewable Energy, 2014. |

| 54. |

"Sri Lanka Destroys Huge Ivory Haul," Agence France Presse, January 26, 2016. |

| 55. |

Hannah Osbourne, "2004 Indian Ocean Earthquake and Tsunami," December 22, 2014, http://www. ibtimes.co.uk. |

| 56. |

Loy Rego, "Social and Economic Impact of December 2004 Tsunami," Asian Disaster Preparedness Center. |

| 57. |

"IMF's US$1.5 bn Loan to Ease Lanka's Liquidity Pressures," Daily News, May 6, 2016. |

| 58. |

"Sri Lanka Country Report," The Economist Intelligence Unit, July 28, 2016. |

| 59. |

"Sri Lanka Secures $1.5bn IMF Loan to Avert Crisis," Financial Times, April 29, 2016. |

| 60. |

"IMF Agrees $1.5 bn Bailout for Sri Lanka," Enterprise, June 30, 2016. |

| 61. |

"Worker Remittances Likely to Slow in 2016," Mirror Business, January 4, 2016. |

| 62. |

"Joint Statement from the U.S. Department of State and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Sri Lanka on the Inaugural U.S.–Sri Lanka Partnership Dialogue," U.S. Department of State, February 29, 2016. |

| 63. |

"Sri Lanka Seeks Chinese Largesse Again," Daily FT, April 9, 2016. |

| 64. |

Ameen Izzadeen, "Listen to the Indian Ocean, Undercurrents of a Submarine War," Daily Mirror, May 6, 2016. |

| 65. |

"Sri Lanka, China Agree to Work for an 'All-Weather Friendship," April 11, 2016, http://www.security-risks.com. |

| 66. |

"Prospects and Challenges on China's 'One Belt, One Road': A Risk Assessment Report," The Economist Intelligence Unit, http://www.eiu.com. |

| 67. |

"Sri Lanka: Prime Minister Visits China," Economist Intelligence Unit, http://country.eiu.com. |

| 68. |

Nilanthi Samaranayake, The Long Littoral Project: Bay of Bengal, A Maritime Perspective on Indo-Pacific Security, Center for Naval Analysis, September 2012. |

| 69. |

Jeff Smith, "China's Investment in Sri Lanka," Foreign Affairs, May 23, 2016. |

| 70. |

Ameen Izzadeen, "Listen to the Indian Ocean, Undercurrents of a Submarine War," Daily Mirror, May 6, 2016. |

| 71. |

Lisa Curtis, "Sri Lanka's Democratic Transition: A New Era for the U.S.-Sri Lanka Relationship," Testimony Before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific, June 9, 2016. |

| 72. |

"Sri Lankan PM Addresses India's Security Concerns," April 11, 2016, http://www.security-risks.com. |

| 73. |

"Short of Options Sri Lanka Turns Back to Beijing's Embrace," Daily Mirror, February 12, 2016. |

| 74. |

Lisa Curtis, "Sri Lanka's Democratic Transition: A New Era for U.S.-Sri Lanka Relationship," Testimony Before the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific, June 9, 2016. |

| 75. |

Jeff Smith, "China's Investment in Sri Lanka," Foreign Affairs, May 23, 2016. |

| 76. |

"U.S. Relations with Sri Lanka," Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs, U.S. Department of State, April 6, 2016. |

| 77. |

Secretary of State John Kerry, "Remarks with the Sri Lankan Foreign Minister Mangala," U.S. Department of State, February 25, 2016. |

| 78. |

John Kerry, Secretary of State, "Strengthening the US-Sri Lanka Partnership for Human Rights and Lasting Peace," Colombo, Sri Lanka, May 2, 2015. |

| 79. |

United States Ambassador Atul Keshap, "Remarks at Jetwing Hotel, Jaffna," United States Department of State, August 15, 2016, http://srilanka.usembassy.gov. |

| 80. |

Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification, Foreign Operations, Appendix 3, FY2017. |

| 81. |

"Sri Lanka," CIA World Factbook, https://www.cia.gov. |

| 82. |

U.S. Department of State, Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs, "U.S. Relations with Sri Lanka," April 6, 2016. |

| 83. |

Joint Statement From the US Department of State and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Sri Lanka on the Inaugural US-Sri Lanka Partnership Dialogue," February 29, 2016. |

| 84. |

Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification, Foreign Operations, Appendix 3, FY2017. |

| 85. |

"Collaboration Agreement Launched Between Sri Lanka and the United States House Democracy Partnership," Daily News (SL), September 17, 2016. |

| 86. |

USAID, "Democracy, Human Rights and Governance," March 15, 2016. |

| 87. |

Jon Grevatt, "US Eases Military trade Restrictions on Sri Lanka," Janes Defence Weekly, June 5, 2016. |

| 88. |

U.S. Embassy, "USS New Orleans Visits Colombo July 24, 2016," press release, http://srilanka.usembassy.gov. |

| 89. |

"Secretary of the Navy Visits Sri Lanka Navy Dockyard in Trincomalee," August 24, 2016, http://www.security-risks.com. |

| 90. |

"US Pacific Command Concludes Operation Pacific Angel in Northern Sri Lanka," August 24, 2016, http://www.security-risks.com. |

| 91. |

Adapted from various sources including "Sri Lanka: Profile-Timeline," BBC News, January 9, 2015. |