The Terrorist Screening Database: Background Information

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI, the Bureau) has acknowledged that it had been investigating the shooter who killed 49 people at an Orlando nightclub on June 12, 2016. The gunman has been identified as Omar Mateen, a 29-year-old security guard in Florida who was born in New York. Reportedly, Mateen was watchlisted while under FBI investigation. This report provides background information on the watchlisting process.

The Terrorist Screening Database (TSDB, commonly referred to as the Terrorist Watchlist) lies at the heart of federal efforts to identify and share information about identified people who may pose terrorism-related threats to the United States. It is managed by the Terrorist Screening Center (TSC) and includes biographic identifiers for those known to have or those suspected of having ties to terrorism. It stores hundreds of thousands of unique identities. Portions of the TSDB are exported to data systems in federal agencies that perform screening activities such as background checks, reviewing the records of passport and visa applicants, and official encounters with travelers at U.S. border crossings.

The TSC, a multi-agency organization administered by the FBI, maintains the TSDB. The TSC was created by Presidential Directive in 2003 in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Before the TSC consolidated federal watchlisting efforts, numerous separate watchlists were maintained by different federal agencies. The information in these lists was not necessarily shared or compared.

The efforts that surround the federal watchlisting regimen can be divided into three broad processes centered on the TSDB:

Nomination, which involves the identification of known or suspected terrorists via intelligence collection or law enforcement investigations. The U.S. government has a formal watchlist nomination process.

Verification of identities for the TSDB and export of data to screening systems, which involves the creation and maintenance of the TSDB, as well as the compiling and export of special TSDB subsets for various intelligence or law enforcement end users (screeners).

Screening, which involves end users—screeners—checking individuals or identities they encounter against information from the TSDB that is exported to screening databases.

The Terrorist Screening Database: Background Information

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

Summary

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI, the Bureau) has acknowledged that it had been investigating the shooter who killed 49 people at an Orlando nightclub on June 12, 2016. The gunman has been identified as Omar Mateen, a 29-year-old security guard in Florida who was born in New York. Reportedly, Mateen was watchlisted while under FBI investigation. This report provides background information on the watchlisting process.

The Terrorist Screening Database (TSDB, commonly referred to as the Terrorist Watchlist) lies at the heart of federal efforts to identify and share information about identified people who may pose terrorism-related threats to the United States. It is managed by the Terrorist Screening Center (TSC) and includes biographic identifiers for those known to have or those suspected of having ties to terrorism. It stores hundreds of thousands of unique identities. Portions of the TSDB are exported to data systems in federal agencies that perform screening activities such as background checks, reviewing the records of passport and visa applicants, and official encounters with travelers at U.S. border crossings.

The TSC, a multi-agency organization administered by the FBI, maintains the TSDB. The TSC was created by Presidential Directive in 2003 in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Before the TSC consolidated federal watchlisting efforts, numerous separate watchlists were maintained by different federal agencies. The information in these lists was not necessarily shared or compared.

The efforts that surround the federal watchlisting regimen can be divided into three broad processes centered on the TSDB:

- Nomination, which involves the identification of known or suspected terrorists via intelligence collection or law enforcement investigations. The U.S. government has a formal watchlist nomination process.

- Verification of identities for the TSDB and export of data to screening systems, which involves the creation and maintenance of the TSDB, as well as the compiling and export of special TSDB subsets for various intelligence or law enforcement end users (screeners).

- Screening, which involves end users—screeners—checking individuals or identities they encounter against information from the TSDB that is exported to screening databases.

The Terrorist Screening Database (TSDB, commonly referred to as the Terrorist Watchlist) lies at the heart of federal efforts to identify and share information about identified people who may pose terrorism-related threats to the United States.1 It is managed by the Terrorist Screening Center (TSC) and includes biographic identifiers for those known to have or those suspected of having ties to terrorism.2 It stores hundreds of thousands of unique identities.3 Portions of the TSDB are exported to data systems in federal agencies that perform screening activities such as background checks, reviewing the records of passport and visa applicants, and official encounters with travelers at U.S. border crossings.4

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI, the Bureau) has acknowledged that it had been investigating the shooter who killed 49 people at an Orlando nightclub on June 12, 2016. The gunman has been identified as Omar Mateen, a 29-year-old security guard in Florida who was born in New York. Reportedly, Mateen was watchlisted while under FBI investigation. This report provides background information on the watchlisting process.

The Terrorist Screening Center, the Hub of Watchlisting

The TSC, a multi-agency organization administered by the FBI, maintains the TSDB.5 The TSC was created by Presidential Directive in 2003 in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.6 Before the TSC consolidated federal watchlisting efforts, numerous separate watchlists were maintained by different federal agencies. The information in these lists was not necessarily shared or compared.7

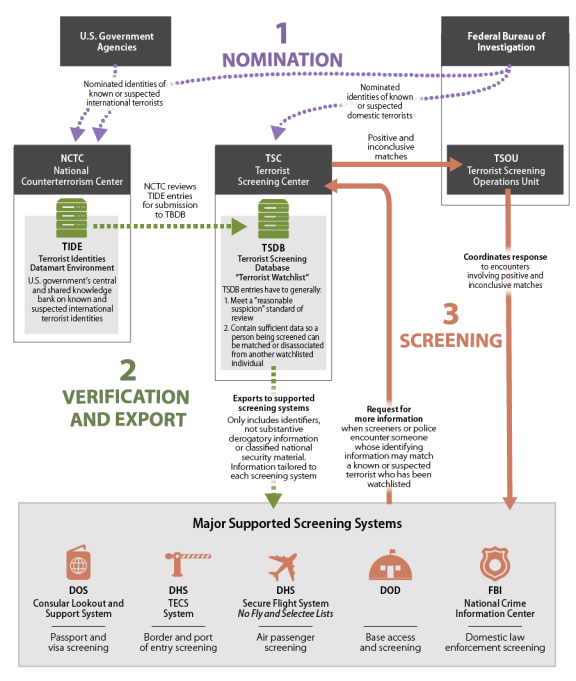

The efforts that surround the federal watchlisting regimen can be divided into three broad processes centered on the TSDB:

- Nomination, which involves the identification of known or suspected terrorists via intelligence collection or law enforcement investigations. The U.S. government has a formal watchlist nomination process.8

- Verification of identities for the TSDB and export of data to screening systems, which involves the creation and maintenance of the TSDB, as well as the compiling and export of special TSDB subsets for various intelligence or law enforcement end users (screeners).

- Screening, which involves end users—screeners—checking individuals or identities they encounter against information from the TSDB that is exported to screening databases.9 The No Fly List10 is one such database. (In FY2011, screeners reported "more than 1.2 billion queries against [the TSDB]."11) The screening process can also yield more information on particular subjects that may be fed back into the TSDB.

(See Figure 1 for a visual depiction of the federal agencies involved in watchlisting.)

|

|

Source: Based on CRS analysis of Federal Bureau of Investigation, "Terrorist Screening Center: Frequently Asked Questions," September 25, 2015; Christopher M. Piehota, Director, Terrorist Screening Center, Federal Bureau of Investigation, statement before the House Homeland Security Committee, Subcommittee on Transportation Security, Hearing: "Safeguarding Privacy and Civil Liberties While Keeping our Skies Safe," September 18, 2014; National Counterterrorism Center, "Terrorist Identities Datamart Environment (TIDE)," August 1, 2014; Department of Justice, Office of Inspector General, "Audit of the Federal Bureau of Investigation's Management of Terrorist Watchlist Nominations," March 2014. |

Nominations

In their daily work poring over raw information or case files, professionals at U.S. government agencies—dubbed "originators" in the watchlisting process—uncover the possible identities of people suspected of involvement in terrorist activity. Such identities can be nominated for addition to the TSDB. Originators can work in places such as intelligence and law enforcement agencies or U.S embassies and consulates. The nominations they initiate include people who are classed together in the watchlisting regimen as "known or suspected terrorists" (KSTs).

For the federal government's watchlisting regimen, a "known terrorist" is

an individual whom the U.S. government knows is engaged, has been engaged, or who intends to engage in terrorism and/or terrorist activity, including an individual (a) who has been charged, arrested, indicted, or convicted for a crime related to terrorism by U.S. government or foreign government authorities; or (b) identified as a terrorist or member of a designated foreign terrorist organization pursuant to statute, Executive Order, or international legal obligation pursuant to a United Nations Security Council Resolution.12

A "suspected terrorist" is

An individual who is reasonably suspected to be, or has been, engaged in conduct constituting, in preparation for, in aid of, or related to terrorism and/or terrorist activities based on an articulable and reasonable suspicion.13

Verification of Identities for the TSDB and Export to Federal Data Systems

All nominated identities of known or suspected terrorists for the TSDB are vetted by analysts at either the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) or the FBI and then undergo verification at the TSC.14

NCTC handles the nominations of all international terrorists (including purely international suspects submitted by the FBI). In this process, NCTC maintains a classified database known as the Terrorist Identities Datamart Environment (TIDE). TIDE is the U.S. government's "central repository of information on international terrorist identities."15 TIDE includes:

to the extent permitted by law, all information the [U.S. government] possesses related to the identities of individuals known or appropriately suspected to be or to have been involved in activities constituting, in preparation for, in aid of, or related to terrorism (with the exception of purely domestic terrorism information).16

In late 2013, TIDE contained the identities of approximately 1.1 million people. Of this number, about 25,000 were U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents linked to international terrorist organizations.17 Not all of the entries in TIDE get into the TSDB, which according to the FBI held approximately 800,000 people in November 2014.18 Every day, NCTC analysts work on updating identities in TIDE, and NCTC exports a subset of its TIDE data holdings for the TSDB.19 Analysts at the TSC perform a final verification of identities before they become a part of the TSDB. (For more about the concepts involved, see "Making the TSDB Cut.") Finally, on its own, TIDE is an important resource used by counterterrorism professionals throughout the U.S. Intelligence Community20 in daily counterterrorism analytical work.

FBI analysts in the Bureau's Terrorist Review and Examination Unit process FBI nominations to the TSDB.21 These nominations often spring from FBI investigative work. The unit forwards international nominations to NCTC for inclusion in TIDE, where the data in the nomination is reviewed before release to the TSC.22 The Bureau also forwards nominations of purely domestic terrorists as well as "domestic terrorists that may have connections to international terrorism" directly to the TSC for review.23

Making the TSDB Cut

To make it into the TSDB, a nomination vetted by either NCTC or the FBI has (1) to meet the "reasonable suspicion watchlisting standard" and (2) have sufficient identifiers. TSC personnel verify that each nomination that makes it into the TSDB meets both of these criteria.24 The TSDB is a sensitive but unclassified dataset, and each record created by TSC personnel for the TSDB includes only an individual's identifiers and no "substantive derogatory information or classified national security" material.25

Reasonable Suspicion

Articulable facts form the building blocks of the reasonable suspicion standard undergirding the nomination of suspected terrorists. Sometimes, on their own, the facts involved in identifying an individual as a possible terrorist are not enough to develop a solid foundation for a nomination. In such cases, investigators and intelligence analysts make rational inferences regarding potential nominees.26 The TSC vets all nominations, and when the facts, bound with rational inferences, hold together to form a reasonable determination that the person is suspected of having ties to terrorist activity, the person is included in the TSDB.27 In the nomination process, guesses or hunches alone cannot add up to reasonable suspicion. Likewise, one cannot be designated a known or suspected terrorist based solely on activity protected by the First Amendment or race, ethnicity, national origin, and religious affiliation.28

Identifiers

Once the reasonable suspicion standard is met, analysts must have the ability to distinguish a specific terrorist's identity from others. Thus, minimum biographic criteria must exist. At the very least, for inclusion in the TSDB, a record must have a last name "and at least one additional piece of identifying information (for example a first name or date of birth)."29

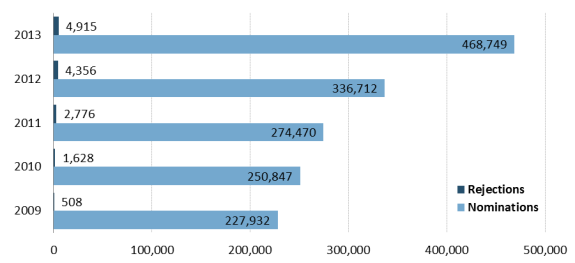

Most nominations appear to make the TSDB cut. From FY2009 to FY2013, 1.6 million individuals were nominated. About 1% (just over 14,000) were rejected. (See Figure 2.)

Export

The TSC routinely exports watchlist information to federal agencies authorized to conduct terrorist screening. According to the TSC, this occurs as the information is processed, "seconds later, it shows up with our partners so they can do near-real-time screening.... "30 According to the TSC, "five major U.S. Government agencies" receive TSDB exports (subsets of the entire watchlist).31 Each of the agencies gets a different portion of the TSDB, "tailored to [its] mission, legal authorities, and information technology requirements."32 The agencies and examples of some of the screening systems that ingest TSDB information include the following:

- The Department of State, whose consular officers draw on TSDB information in the Consular Lookout and Support System that is used for passport and visa screening.

- The Transportation Security Administration, which uses information from the TSDB for aviation security screening. The No Fly List, the Selectee List, and the Expanded Selectee List are parts of what is known as the Secure Flight program. The No Fly List includes identities of individuals who may present a threat to civil aviation and national security. Listed individuals are not allowed to board a commercial aircraft "flying into, out of, over, or within United States airspace; this also includes point-to-point international flights operated by U.S. carriers."33 The selectee list includes individuals who must undergo additional security screening before being allowed to board a commercial aircraft. The minimum derogatory information requirements that form the basis for including an identity in the No Fly List and the Selectee List are "more stringent than the TSDB's known or reasonably suspected standard."34 This makes these lists much smaller than the TSDB. In 2014, there were approximately 800,000 identities in the TSDB according to the FBI, double the figure in 2008.35 In 2014, about 8% of the TSDB identities—around 64,000—were on the No Fly List and about 3%—roughly 24,000—were on the Selectee List.36 As an extra security measure developed in response to a failed attempt to trigger an explosive by a foreign terrorist on board a U.S.-bound flight on December 25, 2009, the Expanded Selectee List was created. It screens against all TSDB records that include a person's first and last name and date of birth that are not already on the No Fly or Selectee Lists.37

- Customs and Border Protection (CBP) owns and uses TECS (not an acronym), the main system that CBP officers employ at the border and elsewhere to screen arriving travelers and determine their admissibility. 38 TECS accepts "nearly all" records from the TSDB.39 CBP also uses the Automated Targeting System (ATS), which is "a decision support tool that compares traveler, cargo, and conveyance information against law enforcement, intelligence, and other enforcement data using risk-based targeting scenarios and assessments."40 As one of its functions, ATS "compares information about travelers and cargo arriving in, transiting through, or exiting the country, against law enforcement and intelligence databases" including information from the TSDB.41 As its name suggests, Automated Targeting System-Passenger (ATS-P) is the portion of ATS focused on passengers, "for the identification of potential terrorists, transnational criminals, and, in some cases, other persons who pose a higher risk of violating U.S. law"42 and is used by CBP personnel at the border and ports of entry as well as elsewhere.43

- The FBI runs the National Crime Information Center's (NCIC) database, which has been described by the Bureau as "an electronic clearinghouse of crime data that can be tapped into by virtually every criminal justice agency nationwide, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year."44 The NCIC includes 21 files. One of them, the "Known or Appropriately Suspected Terrorist File" includes TSDB records. The NCIC database is used for domestic law enforcement screening.45

- The Department of Defense uses TSDB information to help screen people trying to enter military bases.46

Screening

|

Rules-Based Screening—Looking for Potential Threats without Relying on Identities Of course, the federal government is not aware of all the identities of people with ties to terrorist groups who may threaten the United States. Thus, a watchlisting regimen founded on identities is inherently incomplete. In a push for a more complete sense of threat, CBP and TSA have established systems that assess the risk of particular travelers based on rules—"patterns identified as requiring additional scrutiny."47 CBP's ATS includes such rules. CBP establishes "rules" for ATS "based on CBP officer experience, analysis of trends of suspicious activity, law enforcement cases and raw intelligence" and looks for travelers or cargo hewing to such patterns.48 Additionally, TSA works with CBP data and also establishes its own rules based on intelligence analysis to create two watchlists within TSA's Secure Flight Program. These have not been publicly named.49 |

Employees from U.S. federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies who perform screening activities (screeners) check the identities of individuals they encounter in their daily work against specific subsets of the TSDB. Such queries happen either in-person or via submitted official (electronic or paper) forms. Examples include instances when

- foreign visitors and returning U.S. citizens enter the United States at a port of entry and are screened by CBP officers;

- state or local police regularly pull over vehicles for moving violations and interact with drivers and passengers; and

- foreign applicants submit visa applications which are reviewed by Department of State officials.50

Likely, every year, screeners make more than a billion queries against information in the TSDB.51 Queries that yield possible matches between the identifying information provided by individuals and TSDB holdings are known as "encounters."52 Screeners receive notification of possible matches via their specific screening databases.53

When a query produces an encounter, screeners are directed to contact the TSC. Employees in the TSC's 24-hour operations center perform additional research to track down any information that "may assist in making a conclusive identification."54 (Screeners only have access to the identifying information available in the TSDB, while TSC analysts can search through additional datasets and intelligence to clarify a possible match.) If a positive match is made or if the TSC analysis is inconclusive, the FBI's Terrorist Screening Operations Unit coordinates how the government responds. "For example, [the unit] may deploy agents to interview and possibly apprehend the subject."55 Any new information collected from an encounter is forwarded to the TSC to enhance any related existing TSDB entry.56

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Christopher M. Piehota, Director, Terrorist Screening Center, Federal Bureau of Investigation, statement before the House Homeland Security Committee, Subcommittee on Transportation Security, Hearing: "Safeguarding Privacy and Civil Liberties While Keeping our Skies Safe," September 18, 2014. Hereinafter: Piehota, Testimony. |

| 2. |

Timothy J. Healy, (former) Director, Terrorist Screening Center, Federal Bureau of Investigation, statement before the House Committee on the Judiciary, Hearing, "Sharing and Analyzing Information to Prevent Terrorism," March 24, 2010. According to media reporting, in 2013. |

| 3. |

Department of Justice, Office of Inspector General, "Audit of the Federal Bureau of Investigation's Management of Terrorist Watchlist Nominations," March 2014, footnote 10, p. 2. Hereinafter: Department of Justice, Office of Inspector General, "Audit." |

| 4. |

Ibid. p. 4. |

| 5. |

See https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/nsb/tsc/about-the-terrorist-screening-center. |

| 6. |

Ibid. |

| 7. |

Federal Bureau of Investigation, "Ten Years After: The FBI since 9/11, Terrorist Screening Center," (2011). |

| 8. |

Federal Bureau of Investigation, "Terrorist Screening Center: Frequently Asked Questions," September 25, 2015. |

| 9. |

Department of Justice, Office of Inspector General, "Audit," p. 1. |

| 10. |

For a brief discussion of such databases see the "Export" section of this report. |

| 11. |

Ibid., p. 2. |

| 12. |

Federal Bureau of Investigation, "Terrorist Screening Center: Frequently Asked Questions," September 25, 2015. See also Piehota, Testimony. |

| 13. |

Ibid. |

| 14. |

Federal Bureau of Investigation, "Terrorist Screening Center: Frequently Asked Questions," September 25, 2015; Department of Justice, Office of Inspector General, "Audit," p. 3. The nomination process is governed by watchlist procedures described in "Watchlisting Guidance" developed by the "watchlisting community." The community includes the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, the National Reconnaissance Office, the Department of Justice, the Department of Defense, the Department of State, the Department of the Treasury, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Department of Energy. |

| 15. |

TIDE is the "central and shared knowledge bank on known and suspected terrorists and international terror groups" mandated by the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, P.L. 108-458. See National Counterterrorism Center, "Terrorist Identities Datamart Environment (TIDE)," August 1, 2014. |

| 16. |

Ibid. |

| 17. |

Ibid. |

| 18. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittee on Transportation Security, Safeguarding Privacy and Civil Liberties while Keeping Our Skies Safe, Hearing Transcript, 113th Cong., 2nd sess., September 18, 2014, p. 25. In 2013, there were 700,000. See Jeremy Scahill, Ryan Devereaux, "Watch Commander: Barak Obama's Secret Terrorist-Tracking System, by the Numbers," The Intercept, August 5, 2014. Hereinafter: Scahill and Devereaux, "Watch Commander." |

| 19. |

Ibid. |

| 20. |

For a description see http://www.dni.gov/index.php. |

| 21. |

Department of Justice, Office of Inspector General, "Audit," pp. 3-8. |

| 22. |

Ibid, p. 9. |

| 23. |

Piehota, Testimony. |

| 24. |

Federal Bureau of Investigation, "Terrorist Screening Center: Frequently Asked Questions," September 25, 2015. |

| 25. |

Piehota, Testimony. |

| 26. |

Exceptions to the reasonable suspicion threshold exist, and some people are placed in the TSDB "to support immigration and border screening by the Department of State and the Department of Homeland Security." See Piehota, Testimony. Presumably, an example of this was the reported watchlisting of the father of one of the shooters implicated in the San Bernardino shooting incident in December 2015. See also Paula Mejia, "Here's How You End up on the U.S. Watchlist for Terrorists," Newsweek, July 25, 2014. The FBI "generally requires" that subjects of closed terrorism investigations be removed from the TSDB. Limited exceptions exist. Department of Justice, Office of Inspector General, "Audit," p. 10. |

| 27. |

Meaning that the individual is suspected of engaging in conduct constituting, preparing for, aiding in, or related to terrorism and/or terrorist activities. |

| 28. |

There are "limited exceptions to the reasonable suspicion requirement, which exist to support immigration and border screening by the Department of State and Department of Homeland Security." See Piehota, Testimony. |

| 29. |

Department of Justice, Office of Inspector General, "Audit," p. 3. |

| 30. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittee on Transportation Security, Safeguarding Privacy and Civil Liberties while Keeping Our Skies Safe, Hearing Transcript, 113th Cong., 2nd sess., September 18, 2014, p. 24. |

| 31. |

Federal Bureau of Investigation, "Terrorist Screening Center: Frequently Asked Questions," September 25, 2015; Department of Justice, Office of Inspector General, "Audit," p. 9. |

| 32. |

Piehota, Testimony. |

| 33. |

See "Terrorist Screening Center: Frequently Asked Questions," September 25, 2015. |

| 34. |

Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General, Role of the No-Fly and Selectee Lists in Securing Commercial Aviation, (redacted), July 2009, p. 9. |

| 35. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittee on Transportation Security, Safeguarding Privacy and Civil Liberties while Keeping Our Skies Safe, Hearing Transcript, 113th Cong., 2nd sess., September 18, 2014, p. 25. According to media reporting, in 2013, there were about 700,000 people on the watchlist. See Scahill and Devereaux, "Watch Commander." See also Rick Kopel, (then) Principal Deputy Director, Terrorist Screening Center, Federal Bureau of Investigation, written statement before the House Homeland Security Committee, Subcommittee on Transportation Security and Infrastructure Protection, September 9, 2008. |

| 36. |

Piehota, Testimony. |

| 37. |

The Expanded Selectee List is not an official subset of the TSDB, however. See Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General, Implementation and Coordination of TSA's Secure Flight Program, (redacted), July 2012, p. 6; Government Accountability Office, Secure Flight, p. 14. |

| 38. |

Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General, Role of the No-Fly and Selectee Lists in Securing Commercial Aviation, (redacted), July 2009, p. 14. |

| 39. |

Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General, Implementation and Coordination of TSA's Secure Flight Program, (redacted), July 2012, p. 6. |

| 40. |

Department of Homeland Security, Automated Targeting System—TSA/CBO Common Operating Picture, Phase II, Privacy Impact Assessment Update, September 16, 2014, p. 1. |

| 41. |

Ibid. |

| 42. |

Department of Homeland Security, Automated Targeting System, Privacy Impact Assessment, June 1, 2012, p. 6. |

| 43. |

Ibid., pp. 2-7. |

| 44. |

See https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ncic. The FBI describes how NCIC is used by noting that "criminal justice agencies enter records into NCIC that are accessible to law enforcement agencies nationwide. For example, a law enforcement officer can search NCIC during a traffic stop to determine if the vehicle in question is stolen or if the driver is wanted by law enforcement. The system responds instantly. However, a positive response from NCIC is not probable cause for an officer to take action. NCIC policy requires the inquiring agency to make contact with the entering agency to verify the information is accurate and up-to-date. Once the record is confirmed, the inquiring agency may take action to arrest a fugitive, return a missing person, charge a subject with violation of a protection order, or recover stolen property." |

| 45. |

Ibid. See "Terrorist Screening Center: Frequently Asked Questions," September 25, 2015. |

| 46. |

"Terrorist Screening Center: Frequently Asked Questions," September 25, 2015. TSDB information is also shared with some foreign allies. |

| 47. |

Department of Homeland Security, Automated Targeting System, Privacy Impact Assessment, June 1, 2012, p. 2. |

| 48. |

Ibid. |

| 49. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Secure Flight: TSA Should Take Additional Steps to Determine Program Effectiveness, GAO-14-531, September 2014, pp. 12-13. Hereinafter: Government Accountability Office, Secure Flight. |

| 50. |

Examples suggested in Department of Justice, Office of Inspector General, "Audit," p. 1. |

| 51. |

Ibid, p. 2. In FY2011, more than 1.2 billion such queries occurred. |

| 52. |

Ibid. |

| 53. |

Department of Justice, Office of Inspector General, "Audit," p. 4. |

| 54. |

Ibid., pp. 4-5 |

| 55. |

Ibid., p. 5. |

| 56. |

Ibid. People seeking to have their names removed from the TSDB because of "difficulties experienced during travel screening at transportation hubs, such as airports, seaports, train stations, or U.S. border crossings," can use DHS's Traveler Redress Inquiry Program (DHS TRIP). See "Terrorist Screening Center: Frequently Asked Questions," September 25, 2015. For more information on DHS TRIP, see https://www.dhs.gov/dhs-trip. |