Terrorism in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is home to more than 625 million people and around 15% of the world’s Muslim population. The region has faced the threat of terrorism for decades, but threats in Southeast Asia have never been considered as great as threats in some other regions. However, the rise of the Islamic State poses new, heightened challenges for Southeast Asian governments and for U.S. policy towards the region.

Southeast Asia has numerous dynamic economies and three Muslim-majority states, including the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation, Indonesia, which also is the world’s third largest democracy (by population) after India and the United States. Although the mainstream of Islamic practice across the region is comparatively tolerant of other religions, Southeast Asia is also home to several longstanding and sometimes violent separatist movements and pockets of Islamist radicalism, which have led to instances of violence over the past 30 years. These were particularly acute during the 2000s, when several attacks in Indonesia killed hundreds of Indonesians and dozens of Westerners. The threat seemingly eased in the late 2000s-early 2010s, with the success of some Southeast Asian governments’ efforts to combat violent militancy and degrade some of the region’s foremost terrorist groups.

Several Southeast Asian governments, including Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, have intensified counterterror efforts since 2014, outlawing calls for support of the Islamic State and strengthening policing and border-control efforts. Nevertheless, the challenges that governments in the region face were exemplified in January 2016 by a violent attack in Jakarta, Indonesia, that killed eight people, including four civilians.

There are several factors that characterize the terrorism threat in Southeast Asia. The region’s largest Muslim-majority nations, Indonesia and Malaysia, have long been known for moderate forms of Islam and the protection of religious diversity—policies that have widespread popular support but which raise resentments among small numbers of conservative actors. In other Southeast Asian countries with substantial Muslim populations, including the Philippines and Thailand, simmering resentments in Muslim-majority regions have been fed by perceived cultural and economic repression, leading to separatist movements that have posed threats to domestic groups—and in the case of the Philippines, to Western targets.

Threats are evolving with the rise of the Islamic State, which has conducted extensive recruitment in Indonesia’s national language (called “Bahasa Indonesia”) and in the Malay language widely spoken in the region. Though the number of Southeast Asians who have traveled to the Middle East to fight with the Islamic State is considerably lower than numbers from other regions, such as Europe, North Africa, and South Asia, observers estimate that hundreds of Southeast Asians have joined the fight, raising concerns that battle-trained individuals may return to the region and conduct attacks. Southeast Asia’s borders are comparatively porous, raising concerns about trans-border threats that may lead to attacks in third-party states, such as Singapore. This raises the issue of border controls, an important factor for addressing terrorism. Governments in the region have sought better coordination and intelligence sharing—efforts that have been supported by the United States.

The Trump Administration has indicated that combatting terrorism broadly, and IS specifically, is among its highest foreign-policy priorities. This has implications for numerous other U.S. interests, as U.S. policy towards the Asia-Pacific region balances a wide range of security and economic goals. The United States has offered counterterrorism assistance to several Southeast Asian nations. These include helping Indonesia create a centralized antiterrorism unit and providing U.S. troops on the Southern Philippine island of Basilan to help the Armed Forces of the Philippines combat violent groups in the country’s deep South. Congress may wish to evaluate the effectiveness of such assistance, and examine funding levels for counterterrorism assistance. Congress may also wish to consider the relationship between counterterrorism assistance and other U.S. goals in the region, including the development of human rights and civil society in Southeast Asia.

This report will be updated periodically.

Terrorism in Southeast Asia

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview

- Historical Context and the Rise of the Islamic State

- U.S. Interests and Policy Responses

- Country-Level Issues

- Indonesia

- Primary Groups

- State Responses

- Counterterrorism Cooperation with the United States and the Region

- Philippines

- Primary Groups

- State Responses

- Counterterrorism Cooperation with the United States and the Region

- Malaysia

- Primary Groups

- State Responses

- Counterterrorism Cooperation with the United States and the Region

- Thailand

- Primary Groups

- State Responses

- Counterterrorism Cooperation with the United States and the Region

- Australia

- Primary Groups

- State Responses

- Counterterrorism Cooperation with the United States and the Region

- Singapore

- Primary Groups

- State Responses

- Counterterrorism Cooperation with the United States and the Region

- Outlook

Figures

Summary

Southeast Asia is home to more than 625 million people and around 15% of the world's Muslim population. The region has faced the threat of terrorism for decades, but threats in Southeast Asia have never been considered as great as threats in some other regions. However, the rise of the Islamic State poses new, heightened challenges for Southeast Asian governments and for U.S. policy towards the region.

Southeast Asia has numerous dynamic economies and three Muslim-majority states, including the world's largest Muslim-majority nation, Indonesia, which also is the world's third largest democracy (by population) after India and the United States. Although the mainstream of Islamic practice across the region is comparatively tolerant of other religions, Southeast Asia is also home to several longstanding and sometimes violent separatist movements and pockets of Islamist radicalism, which have led to instances of violence over the past 30 years. These were particularly acute during the 2000s, when several attacks in Indonesia killed hundreds of Indonesians and dozens of Westerners. The threat seemingly eased in the late 2000s-early 2010s, with the success of some Southeast Asian governments' efforts to combat violent militancy and degrade some of the region's foremost terrorist groups.

Several Southeast Asian governments, including Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, have intensified counterterror efforts since 2014, outlawing calls for support of the Islamic State and strengthening policing and border-control efforts. Nevertheless, the challenges that governments in the region face were exemplified in January 2016 by a violent attack in Jakarta, Indonesia, that killed eight people, including four civilians.

There are several factors that characterize the terrorism threat in Southeast Asia. The region's largest Muslim-majority nations, Indonesia and Malaysia, have long been known for moderate forms of Islam and the protection of religious diversity—policies that have widespread popular support but which raise resentments among small numbers of conservative actors. In other Southeast Asian countries with substantial Muslim populations, including the Philippines and Thailand, simmering resentments in Muslim-majority regions have been fed by perceived cultural and economic repression, leading to separatist movements that have posed threats to domestic groups—and in the case of the Philippines, to Western targets.

Threats are evolving with the rise of the Islamic State, which has conducted extensive recruitment in Indonesia's national language (called "Bahasa Indonesia") and in the Malay language widely spoken in the region. Though the number of Southeast Asians who have traveled to the Middle East to fight with the Islamic State is considerably lower than numbers from other regions, such as Europe, North Africa, and South Asia, observers estimate that hundreds of Southeast Asians have joined the fight, raising concerns that battle-trained individuals may return to the region and conduct attacks. Southeast Asia's borders are comparatively porous, raising concerns about trans-border threats that may lead to attacks in third-party states, such as Singapore. This raises the issue of border controls, an important factor for addressing terrorism. Governments in the region have sought better coordination and intelligence sharing—efforts that have been supported by the United States.

The Trump Administration has indicated that combatting terrorism broadly, and IS specifically, is among its highest foreign-policy priorities. This has implications for numerous other U.S. interests, as U.S. policy towards the Asia-Pacific region balances a wide range of security and economic goals. The United States has offered counterterrorism assistance to several Southeast Asian nations. These include helping Indonesia create a centralized antiterrorism unit and providing U.S. troops on the Southern Philippine island of Basilan to help the Armed Forces of the Philippines combat violent groups in the country's deep South. Congress may wish to evaluate the effectiveness of such assistance, and examine funding levels for counterterrorism assistance. Congress may also wish to consider the relationship between counterterrorism assistance and other U.S. goals in the region, including the development of human rights and civil society in Southeast Asia.

This report will be updated periodically.

Overview

Militant Islamist groups have operated in Southeast Asia for decades. The region, home to more than 625 million people, has numerous countries with large Muslim populations, including Indonesia, the world's most populous Muslim-majority nation and the world's third most populous democracy (after India and the United States). The region is home to several longstanding and sometimes violent separatist movements, as well as pockets of Islamist radicalism, which have led to instances of violence over the past 30 years, particularly during the 2000s.

Many observers have noted the success of some Southeast Asian governments' efforts combatting violent militancy and degrading some of the region's foremost terrorist groups, including the pan-regional, but largely Indonesian based, Jemaah Islamiyah and the Philippines' Abu Sayyaf. The United States has offered considerable counterterrorism assistance to Southeast Asian governments, particularly since the September 11, 2001, attacks. These include helping Indonesia create a centralized antiterrorism unit and providing U.S. advisory troops on the Southern Philippine island of Basilan to help the Armed Forces of the Philippines combat violent groups in the country's deep South.

The rise of the Islamic State (IS) in Iraq and Syria1 since 2014, however, has raised the possibility of new and heightened terrorism risks in Southeast Asia. A January 2016 terrorist attack in Jakarta, Indonesia, that killed eight individuals, four of them civilians, demonstrated that militants in the region are seeking support or inspiration from the Islamic State, increasing the risks of terrorism in Southeast Asia—risks that could harm United States citizens or adversely affect U.S. security interests in the region.2 The State Department's 2015 Country Reports on Terrorism stated that, "countries in the East Asia and Pacific region faced the threat of terrorist attacks, flows of foreign terrorist fighters to and from Iraq and Syria, and groups and individuals espousing support for the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)."3

The Trump Administration has indicated that combatting IS is one of its highest priorities. A January 2017 foreign policy statement posted on the White House website stated that, "Defeating ISIS and other radical Islamic terror groups will be our highest priority.... [T]he Trump Administration will work with international partners to cut off funding for terrorist groups, to expand intelligence sharing, and to engage in cyberwarfare to disrupt and disable propaganda and recruiting." 4

In Southeast Asia, despite perceptions among analysts that risks are growing, the region generally has not been seen as a front-line threat on par with some other parts of the world, such as the Middle East or northern Africa. As Congress considers U.S. policy towards Southeast Asia, it may wish to consider several questions:

- What is the nature and extent of radicalization in Southeast Asia, and does it constitute a threat to U.S. interests in the region? If so, how, and to what extent?

- What is the nature of threats to U.S. security interests that radicalism poses in Southeast Asia, and how acute are they?

- Are these threats increasing in significance? Are threat levels affected by the rise of the Islamic State? If so, in what ways?

- How effective are Southeast Asian governments' capabilities to monitor and combat the threat of terrorism in their homelands, and to coordinate efforts when those threats spread across borders? Where these capabilities are insufficient, could U.S. assistance help address capability gaps? If so, then what are the most effective legislative and oversight tools that Congress has at its disposal to ensure that U.S. assistance is used effectively towards these ends?

- What priority should policymakers place on supporting counterterrorism efforts in Southeast Asia, compared with other U.S. security, diplomatic and economic goals? What are the most effective legislative and oversight tools that Congress has at its disposal to help shape the development and ordering of those priorities?

- What tools does Congress have at its disposal to ensure that U.S. support for Southeast Asian counterterrorism efforts does not encourage and enable countries to unduly curtail human rights and the rule of law? Congress may wish to consider, for example, conditionalities on assistance, and the implementation of existing vetting procedures and requirements.

- What lessons might be drawn from Southeast Asian efforts to degrade terrorist groups and de-radicalize individuals harboring militant views, and is the Administration effectively evaluating such lessons? Are these lessons applicable in other parts of the world as well?

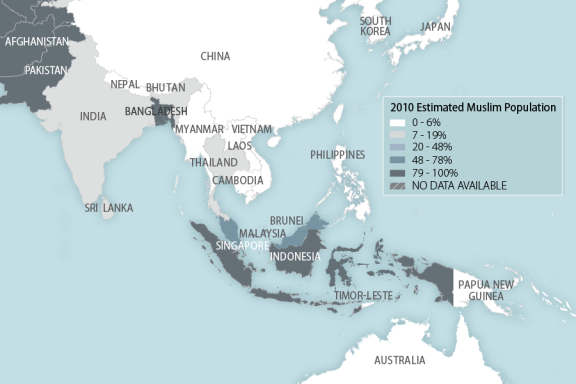

Historical Context and the Rise of the Islamic State

Southeast Asia is home to large Sunni Muslim populations—around 240 million people region- wide, or 40% of Southeast Asia's overall population and over 15% of the world's estimated Muslim population – making it one of the primary demographic centers of the Islamic world.5 The vast majority of Southeast Asian Muslims have traditionally subscribed to moderate, syncretic forms of the religion. More conservative Sunni communities, however, have grown with support from donors in the Arab Gulf states since the late 20th century and small pockets of radicalism have been active for decades.

Militant Islamist groups in Southeast Asia have widely different origins. Longstanding separatist movements in parts of the Indonesian archipelago, particularly in Aceh, have also created safe havens for violent groups. The Philippines and Thailand—dominated, respectively, by Catholic and Buddhist majorities—have fought separatist movements in their Muslim-majority southern regions for decades, and grievances in those regions have led to extremism and violence. Islam played a role in anti-U.S. insurgency in the Philippines from the earliest stages of U.S. colonial involvement in the Philippines in the late 19th century.6 Malaysia, another Muslim-majority nation, has not had a strong indigenous terrorist movement, but like the other nations in the region, its porous borders have allowed terrorists to operate from its shores. Some observers also believe Malaysia has been an active source and transit point for terrorist financing.

With the notable exception of the Jemaah Islamiyah network in the early 2000s, the linkages among violent Southeast Asian groups, and links between them and groups centered in the Middle East, traditionally have been weak. Most Southeast Asian militant groups have operated only in their own country or islands, and focused on domestic issues such as promoting the adoption of Islamic law (sharia) and seeking independence from central government control.

However, the war in Afghanistan and the rise of globalized social media contributed to the radicalization of Islam in Southeast Asia, and Jemaah Islamiyah was widely linked to Al Qaeda, and to the Abu Sayyaf Group in the Philippines. Likewise, over the past two years, the rise of the Islamic State has led to a new phase of Islamist militancy in Southeast Asia, as in the Middle East and across the Muslim world. Terrorism experts say IS offers inspiration, and the potential for training and material support, for militants in Southeast Asia. IS has conducted online recruitment efforts in Indonesia's national language (called "Bahasa Indonesia") and in the Malay language. Analysts estimate that hundreds of Southeast Asians have travelled to the Middle East to fight with IS—just as some did in the late 1990s in Afghanistan with Al Qaeda. Terrorism experts describe a Southeast Asian "military arm" of the Islamic State known as Katibah Nusantara, made up of Indonesians, Malaysians and others, operating in Syria.7

|

|

Source: Pew Research, "Interactive Data Table: World Muslim Population by Region," http://www.pewforum.org. |

Several Southeast Asian governments, including Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, have intensified counterterror efforts since 2014, outlawing calls for support of IS and strengthening policing and border-control efforts.8 It is difficult to estimate with precision how many individuals from the region have traveled to the Middle East to join the Islamic State fight, or how much financial support the group has derived from Southeast Asia. Authorities in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore, however, have all expressed concerns that the return of battle-trained militants from the Middle East who could conduct attacks in-country or train others to do so poses a threat.9

Some analysts have noted that Southeast Asian counterterrorism efforts in the 2000s and early 2010s largely broke up or weakened large terrorist groups in the region such as JI and Abu Sayyaf. However, many observers argue that this has led to a dangerous situation in which small splinter groups that have survived may now have incentives to use violence to demonstrate their effectiveness and bolster their legitimacy. In so doing, they have sought to attract material support from IS (or other outside groups such as Al Qaeda), and to recruit new members. One other potential concern is that terrorist activity may increase as competition grows between the Islamic State and Al Qaeda over the leadership, definition, and goals of the global community of jihadist-Salafist Sunni Muslims. Some argue this rivalry has created "a rift within the region's Islamist fraternity by dividing them into Al-Qaeda loyalists and Islamic State followers."10

Some officials in the region are concerned that in this new phase, militants may shift strategy and tactics. New attacks may seek to emulate the November 2015 Paris attacks to attack soft targets. There is a potentially larger pool of battle-hardened fighters that could return home from Syria or Iraq to carry out such attacks or to spread radicalism to others. There appears to be increasing use of social media as a recruitment tool that can inspire lone-wolf attacks and draw converts to the IS cause. While it is too early to draw conclusions, the January 2016 Jakarta attack, which targeted a Starbucks and a large shopping mall in addition to a police station, may also point to a return to focusing on Western targets in the region. The Islamic State may also be expanding its activities into Southeast Asia and elsewhere as a way of internationalizing its struggle and compensating for losses in Syria and Iraq. It may also seek to gain the allegiance of existing Islamist groups as a way of expanding its regional network.

U.S. Interests and Policy Responses

The threat of terrorism in or emanating from Southeast Asia has implications for numerous U.S. interests. From the late 2000s, the region gained growing prominence in U.S. foreign-policy initiatives under the Obama Administration's "strategic rebalance" or "pivot" to the Asia-Pacific region. U.S. security relations with several Southeast Asian countries have deepened against the backdrop of rising strategic competition with China. It is unclear at this point whether these developments will continue under the Trump Administration. Rising Islamist militancy could impact stability and threaten U.S. interests in the region, and beyond, in several ways:

- It could lead to a direct attack against U.S. citizens or interests in the region, as well as against the United States.11

- It could also act as a catalyst for recruitment for terrorist activity in Southeast Asian countries, increasing risks for both local and Western governments.

- It could serve as an inspiration for those people thinking of joining terrorist fighters in Iraq, Syria, or elsewhere.

- It could provide cells that help finance terrorist causes in-country, in the Middle East, and beyond.12

- It could heighten the threat of attack by Islamist militants against U.S. partners and allies in Southeast Asia, which in turn could limit the ways and extent to which they support U.S.-led coalition activities against the Islamic State and al Qaeda.

- Terrorist attacks have the potential to exacerbate regional tensions, and distract Southeast Asian governments from other initiatives the United States supports.

- An increased U.S. military presence in the region could become a propaganda or physical target for militants.

- The return of foreign terrorist fighters from Iraq and Syria, and the spread of the Islamic State's ideology through social media, could lead to further attacks and threaten partners, allies, and U.S. security interests.

To address terrorist threats emanating from Southeast Asia, the United States has pursued a variety of efforts to enhance cooperation and build capacity with nations in the region. The United States has coordinated, participated in, or advised a number of global and regional counterterrorism-related policymaking or information exchange bodies in which Asian governments participate:

- The Global Counterterrorism Forum is a multilateral body launched in 2011, whose goal is to reduce the vulnerability of people to terrorism by effectively preventing, combating, and prosecuting terrorist acts and countering incitement and recruitment to terrorism;

- The ASEAN Defense Ministers' Meeting Plus (ADMM Plus) Experts' Working Group on Counterterrorism focuses on strengthening security and defense cooperation in the region;

- The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Terrorism Prevention Branch is responsible for providing assistance to countries toward ratification and implementation of legal instruments against terrorism;

- The Association of Southeast Asian Nations Regional Forum (ARF) fosters dialogue and consultation on political and security issues, including regional counterterrorism activities;

- The U.S. Department of State's Regional Strategic Initiative has supported Ambassadors and their Country Teams in developing regional approaches to counterterrorism;

- The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is an international policymaking and standard-setting body dedicated to combating money laundering and terrorist financing; FATF-style regional bodies bring together governments in the region to conduct mutual self-assessments and promote best practices;

- Malaysia and Singapore are members of the Global Coalition to Counter ISIL, an informal grouping that grew out of U.N.-centered efforts to combat IS.

U.S. counterterrorism assistance has generally been welcomed by Southeast Asian governments. In 2015 testimony before Congress, then-commander of the U.S. Pacific Command, Admiral Samuel Locklear, noted that Southeast Asian perceptions that the region faces heightened risks from the potential return of fighters from the Middle East led some governments in the region to have a greater appetite for assistance:

... the numbers that are coming back, we don't have good fidelity on that at this point in time. But what it has done, it has opened up our information-sharing with all the countries in the region that are concerned about this problem, which all of them are. And this isn't just a mil-to-mil [military-to-military], this is a whole government agency, FBI, those types of agencies.13

Many analysts argue that strategic counterterror responses need to address the root causes behind Islamist discontent in order to diminish the grievances that may help fuel radicalization.14 These root causes have global, regional, national and local components. Tactically, many argue for a focus on enhancing regional counterterror capabilities and networks, tracking released militants, keeping prisons from becoming centers for militant networking and recruitment, controlling porous borders, and contesting social media spaces inhabited by militants.

At times in the past, some Southeast Asian governments have appeared to be ambivalent or even resistant to U.S. pressure to be more aggressive in their pursuit of terrorists, in part to avoid alienating both mainstream Islamic and secular nationalist groups. However, Southeast Asian responses have become more assertive as governments over the years have come to view terrorism and militancy as threats to their own stability. At a November 2015 summit, leaders of the East Asia Summit expressed "grave concern about the spread of violent extremism and terrorism that undermines local communities and threatens peace and security, including in the Asia-Pacific region."15

The Obama Administration placed emphasis on programs that support Combatting Violent Extremism (CVE) in U.S. counterterrorism assistance strategy, seeking to address root causes that draw individuals towards violent radicalism. The United States hosted a Summit on Countering Violent Extremism in Washington DC in February 2015, and the State Department renamed the Bureau of Counterterrorism in February 2016 to the Bureau of Counterterrorism and Countering Violent Extremism, seeking greater funding for such programs.

The Trump Administration's focus may differ from that of the Obama Administration. In February 2017, several media reports indicated that the Administration would review and possibly revamp U.S. CVE programs, focusing them on countering what the Administration determines to be "radical Islamic terrorism."16 Some observers, including some Members of Congress, have criticized such a shift, arguing that it could harm the credibility of U.S. counterterrorism programs with U.S. partners overseas.17

The U.S. government provides Anti-Terrorism Assistance (ATA) out of the Nonproliferation, Anti-Terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs (NADR) foreign assistance account for Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand. In Indonesia, NADR-ATA programs provide training and equipment to police officers to build their capacity to deter, detect, and respond to terrorist threats. Anti-terrorism assistance to Malaysia focuses on training and border security to prevent foreign terrorists from entering or transiting through Malaysia. In the Philippines, U.S. assistance includes programs to "enhance the strategic and tactical skills, as well as the investigative capabilities, of regional civilian security forces, particularly in Mindanao." NADR-ATA funding for Thailand aims to help strengthen border controls, train police in hostage negotiation, and bolster explosive ordnance detection capabilities. Other NADR funding for these countries supports combating weapons of mass destruction.18 (See Table 1.)

In addition to these NADR programs, the Administration's FY2017 request states that Economic Support Funding "will be used to expand CVE's counter-narrative and counter-messaging programming to delegitimize the ideology, narratives, tactics, and recruitment efforts of ISIL and other violent extremist groups, targeting in particular communities in the Levant, Gulf, North Africa, Western Balkans and Southeast Asia that are significant sources of foreign fighters."19

|

Indonesia |

Malaysia |

Philippines |

Thailand |

|

|

FY2015 NADR total |

5,550 |

1,270 |

6,100 |

1,320 |

|

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

FY2016 NADR total |

5,550 |

1,270 |

3,590 |

1,320 |

|

4,600 |

800 |

3,000 |

650 |

|

FY2017 NADR total (requested) |

5,450 |

1,270 |

3,590 |

1,270 |

|

4,500 |

800 |

3,000 |

600 |

Source: Department of State, Congressional Budget Justifications for Foreign Operations, FY2015-17.

Country-Level Issues

Southeast Asia is a diverse region, comprising three Muslim-majority states (Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei), and several countries with substantial Muslim minorities (the Philippines, Thailand, Singapore, and Burma). This section will discuss specific issues in Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia, the three Southeast Asian countries where observers consider terrorism risks that span borders or are directed at Western targets to be highest. It will also discuss Australia, a nation where the threat of terrorism is at least partly derived from its open immigration policies and links to Southeast Asia. Thailand and Singapore will also be discussed.

Indonesia

Indonesia is Southeast Asia's most populous nation, and the world's largest Muslim-majority state. It is also the world's third most populous democracy after India and the United States. It has dealt with violent militancy for decades, particularly since the 1940s, when Islamist groups were among the most active forces fighting Dutch colonial troops. Separatist movements in parts of the country, particularly Aceh, have created safe havens for militant groups to operate and recruit.

Some 87% of Indonesia's 253 million people are Sunni Muslims, with the vast majority subscribing to moderate, syncretic forms of the religion. Religious diversity is enshrined in the constitution. However, Indonesia has been the site of several of the region's deadliest terrorist attacks: Several bombings in Jakarta and tourist center Bali hit Western targets in the 2000s, and the January 2016 attack in Jakarta was a signal event for many, demonstrating that the rise of the Islamic State has inspired some militants to conduct attacks in Indonesia.

|

|

Source: Graphic created by CRS. Map boundaries and information generated by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed] using Department of State Boundaries (2011); Esri (2014); Global Administrative Areas (2012); DeLorme (2014); WHO (2005); and NGA (1994). |

The Jakarta attack highlighted both strengths and weaknesses in Indonesia's counterterrorism capabilities, observers note, and also offered a window to the heightened risks that the country now faces. Immediately after the attack, Indonesian police officials blamed an Indonesian/Malaysian military arm of IS operating in Syria called Katibah Nusantara, which they said had worked with IS supporters in Indonesia to plan the attacks.20 Other experts later called that link tenuous, arguing that the attack had been planned and carried out locally, by a group seeking to prove itself to the Islamic State.21 The conflicting reports highlighted Indonesia's difficulty in tracking militant groups that have splintered from larger groups that were active in the 2000s, particularly Jemaah Islamiyah. Some observers noted, however, that the attacks, although lethal, caused comparatively little damage, demonstrating that Indonesia's efforts to weaken the capability of militants may have prevented deeper violence. Observers have noted that other recent militant attacks in Indonesia have been decidedly low-tech and ineffective in causing considerable damage. Others said the response by President Joko Widodo, who condemned the attacks but said "the people should not be afraid and should not be defeated by these terrorist attacks," set a reassuring tone that diminished their overall effect.22

Primary Groups

Virtually all the primary militant groups operating in Indonesia bear links to Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), which experts believe has been substantially degraded since the early 2000s, when it cooperated with Al Qaeda, carried out attacks in Indonesia that killed hundreds, and at one time triggered concerns that it could emerge as a destabilizing regional force. The arrest or killing of numerous JI leaders since 2002 has created a series of smaller, less organized splinter groups. Some terrorism experts argue that such smaller splinter groups may be highly incentivized to undertake future attacks. As one report stated, "Leaders of Indonesia's tiny pro-ISIS camp are competing to prove their fighting credentials."23 Abu Bakar Baasyir, JI's imprisoned intellectual figurehead who had deep Al Qaeda links, made a public declaration of allegiance to IS from prison in July 2014.

Indonesian counterterrorism officials may face an increasingly complex task in identifying and disrupting recruitment networks that are different from the ones they have known over recent years. Some analysts believe that Indonesia's prisons are among the nation's most important centers of terrorist recruitment. According to one report, there were 270 convicted terrorists housed in 26 Indonesian prisons as of January 2015, with another 90 terrorism suspects under detention or awaiting trial at a paramilitary police detention center in suburban Jakarta.24 According to this report, Indonesian prison authorities have improved their supervision of radical prison inmates in recent years to keep them from forming prison networks. The fact that Baasyir and 23 other prisoners nevertheless were able to publicly pledge loyalty to the Islamic State while under incarceration indicates that the challenges facing Indonesian authorities could be considerable.

Experts generally believe it is difficult to accurately map JI splinter groups and other active groups, given rapidly shifting loyalties. The Jakarta attack appears to have been carried out by members of a group known as Partisans of the Caliphate (Jamaah Anshar Khilafah, JAK), whose ideological leader is detained cleric Aman Abdurrahman, a former JI leader.25 Other groups are active in Java, Maluku, Aceh, and elsewhere. One loosely-organized Aceh-based group, known as Jamaah Ansharut Tauhid (JAT), gained prominence in the late 2000s, but was weakened after the Indonesian police raided their training camp in Aceh in February 2010.

Another prominent group that originated from sectarian violence in Maluku was Mujahedin Indonesia Timur (Mujahidin of Eastern Indonesia, or MIT), which held territory near Poso, Sulawesi, for several years until 2016, when its leader, Santoso, alias Abu Wardah, was killed by Indonesian security forces. The organization reportedly attracted recruits from outside Indonesia, including ethnic Uyghurs (also spelled Uighurs) originally from the People's Republic of China.

In the past, militant recruitment in Indonesia was inspired largely by events at home. International Islamist conflicts, however, have more recently become a source of inspiration for Indonesian militants. Analysts believe the present weakness of Indonesia's largest terror networks is a driver of this development, as weakened militant groups seek to remain relevant. According to some experts, networks that have played roles in recruiting for domestic militant causes are taking on new roles, recruiting and facilitating individuals' travel to Syria via European destinations to fight alongside the IS.26 As an illustration of how loyalties can morph, according to one expert on militant groups in Indonesia, JI is "... reburnishing its reputation as a jihadi organization through its channels to Syrian Islamist rebels."27

State Responses

Indonesia has taken numerous steps to counter the rise of militant groups since 2014, when the Islamic State began to attract greater attention. It has outlawed any public expression of support for IS and blocked numerous websites related to the Islamic State. Indonesia's counterterrorism efforts are police-led, with Detachment 88 (Densus 88)—the elite counterterrorism unit of the police—leading operations and investigations. Counterterrorism units from the Indonesian military are sometimes called upon to support domestic counterterrorism operations and responses.28

One key debate underway in Indonesia is whether the nation's current antiterrorism laws give the national police sufficient ability to monitor and address perceived terrorist threats. President Widodo's government has drafted amendments to the current Anti-Terrorism Law, which dates to 2003, the year after the first Bali bombings. The new legislation could broaden definitions of terrorism and allow police to proactively detain suspected terrorists for up to 90 days without charge or access to legal representation and for longer periods after that. It would also reportedly broaden definitions of criminal support for terrorism, and allow the prosecution of those who travel to the Middle East and are suspected of supporting IS.29

Observers note that Indonesia's largest Muslim organization, Nahdlatul Ulama, has supported a strengthening of counterterrorism laws, which is a departure from its posture when Indonesia drafted its current counterterrorism laws in 2003, and possibly a sign that the mainstream of Indonesian Islamic leaders may now support such measures. However, human rights concerns remain. Human Rights Watch has called on Indonesia to reject amendments to the laws that are "unnecessarily broad and vague," and that would "unjustifiably restrict freedom of expression."30

Counterterrorism Cooperation with the United States and the Region

The United States and Australia have supported the development of Indonesia's counterterrorism capabilities, including helping Indonesia develop the elite counterterrorism unit Detachment 88, responsible for coordinating counterterrorism policy and enforcing Indonesia's antiterrorism laws. The United States has offered training to the leadership and members of the unit, as well as other military and national police personnel. U.S.-Indonesian counterterror capacity-building programs from the outset have also included financial intelligence unit training to strengthen anti-money laundering, counterterror intelligence analysts training, an analyst exchange program with the Treasury Department, and training and assistance to establish a border security system as part of the Terrorist Interdiction Program.31

Indonesia participates in counterterrorism efforts through several international, multilateral, and regional fora including the U.N., the Global Counterterrorism Forum (GCTF), ASEAN, APEC, and others. In August 2014, with co-chair Australia, Indonesia launched the GCTF's new Working Group on Detention and Reintegration. Indonesia has also participated in the Regional Defense Counter Terrorism Fellowship Program, which includes intelligence cooperation, civil-military cooperation in combating terrorism, and maritime security. Indonesia has also participated in the Theater Security Cooperation Program with the U.S. Pacific Command. This participation began over a decade ago by involving Indonesia in counterterrorism seminars promoting cooperation on security as well as subject matter expert exchanges.32

Philippines

Muslim separatist movements, communist rebels, and Islamist terrorist groups have battled Philippine military forces for over four decades. In 2016, the predominantly Catholic Philippines was ranked 12th out of 130 countries on the Global Terrorism Index, which measures terrorist incidents and related fatalities, injuries, and property damages.33 In addition to indigenous Islamist terrorist groups, Al Qaeda operated a cell in Manila that was particularly active in the early to mid-1990s, and Jemaah Islamiyah was known to be active in the country in the 1990s and early 2000s. After 2001, when the Bush Administration designated the Philippines as a front-line state in the global war on terrorism, joint Philippine-U.S. efforts significantly reduced Islamist terrorist threats in the Philippines. Although weakened, an increase in activity by the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) since 2014 and the rise of the Islamic State in the Middle East have raised concerns about possible resurgent terrorist threats in the Philippines. The Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) continues to militarily engage Islamist terrorist organizations such as the ASG and splinter groups of two separatist insurgencies, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF).

Primary Groups

The most established, indigenous terrorist organization with ties to jihadist networks is the Abu Sayyaf Group, based in Sulu in the southern Philippines. The United States listed the ASG as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) in 1997.34 At its peak in the mid-2000s, the ASG posed a significant terrorist threat and maintained ties with Jemaah Islamiyah and factions of the MILF. The ASG has carried out hostage-takings for ransom, killings, and bombings since the early 1990s and provided sanctuary for Jemaah Islamiyah. Members of the ASG and JI are believed to have maintained tenuous links with Al Qaeda.35 The February 2004 bombing of a ferry in Manila Bay, which killed over 100 people, was found to be the work of Abu Sayyaf and the Rajah Solaiman Movement (RSM), another extremist organization based in the southern Philippines. In February 2005, the ASG and RSM carried out simultaneous bombings in three cities, which killed 16 people, while the Philippine government uncovered plots to carry out additional attacks in Manila, including one targeting the United States Embassy.

Over time, the ASG has become more of a criminal organization rather than an ideological one, funded by kidnappings for ransom, extortion, and drug trafficking. Its membership decreased from 1,000-2,000 in 2002 to about 300-400 members, according to various estimates.36 Since 2014, however, the ASG has stepped up its criminal activities, pledged allegiance to IS, and vowed to unite Islamist extremist groups in the Philippines. 37

Other organizations that have expressed support for the Islamic State include splinter groups of the MILF and MNLF, such as the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), which do not support a peace agreement through which Muslims in Mindanao would gain substantial autonomy but not independence. Another group, Ansarul Khilafah Philippines (Supporters of the Caliphate in the Philippines or AKP), based in southern Mindanao, is believed to include former MILF commanders and to be linked to both the BIFF and Jemaah Islamiyah. The AKP reportedly pledged allegiance to the Islamic State and warned of attacks on civilian targets, although some Philippine military officials view it largely as a criminal gang with little military power and "no proven links" to the Islamic State.38 The Maute group, a radical Islamist organization based in southwestern Mindanao, is suspected of carrying out one major attack and planning another in 2016.

In 2014, the government of then-President Benigno Aquino and the MILF signed a peace agreement, the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro. The resulting Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL) provided for substantial political and economic autonomy for the Muslim Moros in portions of Mindanao and Sulu. According to many observers, the BBL also brought hope of greater security and economic development in areas that have been a breeding ground for insurgent and extremist groups. The agreement was not implemented due to opposition in the Philippine Congress. Some experts argue the rejection of the BBL may fuel local recruitment to Islamist extremist groups.39 President Rodrigo Duterte, who entered office in July 2016, stated that he wants to start negotiations on a new Bangsamoro agreement in 2017.40

Many experts argue that after a period of decline, terrorist threats in the Philippines are growing. The ASG has demonstrated a renewed capacity to engage in acts of violence, including bombings, ambushes on military forces and government property, and beheadings of captives.41 The ASG's hostage-takings for ransom, numbering about 20 per year, including of foreign tourists, fishermen, and sailors, have increased.42 Ransom money reportedly has enabled the ASG to obtain arms and ammunition, pay off local communities, and bribe security officials.43

Analysts have expressed concern about three developments: the rise of the Islamic State as an inspiration; the aim of various terrorist groups in the Philippines to join forces; and the international dispersion of IS fighters. Meanwhile, however, the Philippine military continues to pursue Islamist extremist groups aggressively and with some success, and terrorist attacks have been confined to the south.44 Some analysts state that the ASG and other groups potentially may commit "sympathy attacks" or offer safe haven to pan-Islamist groups or individuals from Southeast Asia and elsewhere who have ties to IS. Some terrorist organizations are believed to be uniting under an umbrella body, Dawlatul Islamiyah Waliyatul Masrik (DIWM).45

In the past year, some experts have expressed concern that as the Islamic State loses ground in the Middle East, it may seek to expand in Southeast Asia, and its Southeast Asian recruits may return to the region, particularly to the Philippines, to set up terrorist cells.46 Roughly 10 foreign IS fighters from Southeast Asia and the Middle East and several foreign jihadist cells are alleged to be training with indigenous terrorist groups in the Philippines, according to some reports; Philippine military officials, however, claim that there is no confirmed evidence of operational links or direct collaboration between the Islamic State and Islamist groups in the Philippines.47 Although there have been reports of Filipino Muslims among IS forces in Syria, some experts say that it is more likely that some Filipino overseas workers residing in the Middle East, rather than Filipino Muslims from Mindanao, have joined the Islamic State.48

Since President Duterte took office, at least three major terrorist incidents have occurred. In September 2016, a bomb attack in Davao, where Duterte formerly served as mayor, killed 15 people. In November 2016, a home-made bomb was found near the U.S. Embassy in Manila.49 The Maute group, an Islamist organization that has pledged allegiance to IS, is suspected in both cases. One day after the discovery of the bomb in Manila, the car of members of Duterte's advance security team was hit by an explosive device as they traveled to Marawi, a city in Mindanao, resulting in injuries to nine people.50

|

|

Source: Graphic created by CRS. Map boundaries and information generated by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed] using Department of State Boundaries (2011); Esri (2014); Global Administrative Areas (2012); DeLorme (2014); and NGA (2006). |

State Responses

The Philippine government's counterterrorism efforts include military, political, economic, and ideological components. The Anti-Terrorism Council (ATC), created in 2007, is the lead agency charged with carrying out the Human Security Act of 2007, the principal national terrorism law. Coordination among bureaucratic agencies and between military and law enforcement organizations, overlapping jurisdictions, and lack of equipment reportedly remain problems.51

In January 2017, the Duterte Administration launched the Development Support and Security Plan (DSSP) to succeed the Internal Peace and Security Plan (IPSP). The IPSP (2011-2016) was credited for "significantly clearing" communist militants in 71 out of 76 provinces.52 Although AFP officials have not provided details about their military strategy, as part of the DSSP, the government reportedly has deployed 51 battalions in western and central Mindanao and aims to "significantly reduce the strength of terrorist groups" in the Philippines within six months.53 From July 2016 through December 2016, government forces reportedly launched hundreds of raids resulting in the deaths of over 150 ASG militants.54 The AFP also has targeted BIFF, AKP, and the Maute Group, and has killed several of their top leaders.55

The central government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) have been cooperating on counterterrorism efforts. The Anti-Terrorism Council has worked with the MILF on programs to counter extremism in Islamic schools. In 2016, the MILF formed a task force to counter IS recruitment activities in Mindanao.56 The MILF also signed an agreement with the Duterte Administration in support of the President's controversial campaign against the illegal drug trade, which has helped to fund extremist groups in the south.57

The Philippines cooperates with countries and organizations in Southeast Asia on counterterrorism efforts. In 2016, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia agreed to jointly patrol the Sulu Sea and surrounding waters in order to fight piracy and kidnappings by Islamist extremist groups.58 The Philippines is a member of the Asia-Pacific Group on Money Laundering. The Thailand-based multilateral organization is committed to the implementation and enforcement of international standards to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing.59 In 2015, the 10 nations of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), of which the Philippines is a member, adopted the Langkawi Declaration on the Global Movement of Moderates, "Recognizing that moderation is a core value in the pursuit of long-lasting peace and a tool to diffuse tensions, negate radicalism and counter extremism in all forms and manifestations." The parties to the Declaration agreed to "Promote moderation as an ASEAN value that promotes peace, security and development."60

A lack of economic opportunities continues to help foster a breeding ground for extremist ideologies, groups, and recruitment as well as corruption and criminal activities, particularly in the southern Philippines, according to many experts.61 The Philippine government has been "one of the leading adopters of community-based development in conflict-affected areas."62 The government's Resilient Communities in Conflict Affected Communities program (PAMANA) supports health and education efforts, assistance with land claims, and local government capacity-building in conflict-affected areas, including programs for former combatants and counter-radicalization programs for captured ASG and BIFF fighters.63

Counterterrorism Cooperation with the United States and the Region

|

Joint Special Operations Task Force–Philippines (JSOTF-P) Based in temporary facilities in western Mindanao and Jolo, JSOTF-P advised and assisted two Philippine Regional Combatant Commands at a cost of about $50 million annually. The mission had four main counter insurgency and counterterrorism objectives: deny insurgent/terrorist sanctuary; deny insurgent/terrorist mobility; deny insurgent/terrorist access to resources; and separate the population from the insurgent/terrorist. Related activities included military training, intelligence operations, casualty evacuation and care, and humanitarian and development assistance. Some JSOTF-P personnel supported relief efforts in Leyte province following Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) in November 2013. |

Between 2002 and 2014, the U.S. Joint Special Operations Task Force–Philippines (JSOTF-P), a rotating force of roughly 500 U.S. military personnel, assisted the AFP in its fight against the Abu Sayyaf Group. Philippine-U.S. counterterrorism cooperation, including both military and humanitarian efforts, helped to reduce the membership, potency, and ideological influence of the ASG. JSOTF-P forces began to withdraw in 2014, due to several factors: the weakening of the Abu Sayyaf Group; the improving capabilities of Philippine military forces; and the peace agreement between the Government of the Philippines and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front. However, since 2014, the ASG has increased its activity, the government has been slow to implement a plan to replace military with police forces to maintain security, and the peace process has stalled.

Roughly 100 U.S. Special Operations personnel remain in Mindanao on a rotational basis to provide advice and assistance to the Philippine military in counterterrorism operations. President Duterte in November 2016 expressed a desire to remove U.S. military forces from the Philippines by the time he leaves office in 2022.64 However, Philippine National Defense officials in November 2016 subsequently stated that U.S.-AFP counterterrorism cooperation would continue for the time being.65

The United States provides other support for counterterrorism efforts in the Philippines. U.S. foreign assistance to the Philippines places a high priority on "addressing the root causes of terrorism in Mindanao." Program areas include promoting good governance and the delivery of basic social and economic services; the participation of civil society; basic education; and public health services.66 In addition, the Department of State administers programs that aim to strengthen the ability of Philippine law enforcement to engage local communities, identify youth with the potential of becoming radicalized, and support community efforts to build inter-ethnic harmony.67 Antiterrorism assistance includes training police, including maritime law enforcement personnel, in investigative techniques as well as helping them to track and interdict criminal and terrorist organizations.68 In 2016 and 2017, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) received $33 million and $9.6 million, respectively, in Department of Defense counterterrorism assistance.69 The U.S. government also works with the Philippine Anti-Terrorism Council to pursue cases involving terrorist finance.70

The Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA), finalized between the two governments in April 2014 and sanctioned by the Philippine Supreme Court in January 2016, allows for the increased presence of U.S. military forces, ships, aircraft, and equipment in the Philippines on a rotational basis and U.S. access to Philippine military bases. Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, inaugurated as President in June 2016 after EDCA was finalized, has expressed skepticism about numerous aspects of his country's reliance on the United States, but has also stated that he will stand by the EDCA agreement. The Philippines has offered five military bases for U.S. access under EDCA, including Lumbia Air Base in southern Mindanao. The inclusion of Lumbia reportedly reflected concerns about terrorism and efforts by IS to influence local militants in that region.71

Malaysia

Unlike many of its neighbors in Southeast Asia, Malaysia does not appear to have well established indigenous separatist groups or insurgents that engage in terrorist activities. Violent Islamist extremist groups have held meetings in or channeled funds and supplies through Malaysia in scattered instances over the past 25 years, but Malaysian law enforcement appears to have been largely successful in preventing those groups from gaining a foothold in the country.72 However, Malaysia is not immune to the consequences of the Islamic State's rise.

Primary Groups

Malaysia faces terrorist threats on several levels: fighters returning from conflict zones, strengthening of regional terrorist groups, radicalization of individuals (including, for example, the possibility of "lone wolf" attacks) and potential further inroads by the IS and/or Al Qaeda.

|

|

Source: Graphic created by CRS. Map boundaries and information generated by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed] using Department of State Boundaries (2011); Esri (2014); Global Administrative Areas (2012); DeLorme (2014); and NGA (2007). |

Some Malaysians reportedly have provided funds to some insurgent and terrorist groups in Iraq and Syria, have facilitated others' support of these groups, and some have traveled to Iraq and Syria to fight or serve on the front lines. Verifiable figures are not available, but most news reports cite estimates of 100 or more Malaysians actively working with the Islamic State or rebel groups in the Middle East.73 Some Malaysians have provided small-scale financial support to insurgent and terrorist groups in the Middle East. According to police reports, most financial transfers that support or potentially support militant groups are conducted with cash or through the hawala informal value transfer system,74 making it difficult to completely stop funding of terrorist groups.75

Recent arrests in Malaysia may indicate increased international terror linkages with elements in Malaysia. Malaysian police arrested seven men, both foreign and Malaysian, who are believed to have links with the IS and Al Qaeda in late 2016. These men are believed to have been involved in a number of terrorist contexts. One was reportedly gathering information about an international school in Kuala Lumpur while another tried to smuggle weapons to Poso, Sulawesi, in Indonesia and attempted to infiltrate Burma to launch attacks there. Another individual was reportedly planning an attack on entertainment spots in Kulala Lumpur.76 At least one of the suspects is thought to have coordinated his activities with a Malaysian in Syria. In further police action, four members of an IS linked terrorist cell were arrested in Sabah in January 2017. The group included a Malaysian, a Filipino, and two Bangladeshis. The cell is thought to be commanded by Malaysian Mahmud Ahmad and to have links with Abu Sayyaf in the Philippines.77 The IS's only successful attack thus far in Malaysia was at the Movida nightclub in Puchong, Selangor, on June 28, 2016, which injured eight people.78 It was reported that the Movida attack was ordered by IS member Muhamad Wanndy Mohamad Jedi from Malacca, who is based in Syria.79 Police action following the Movida attack reportedly broke up planned attacks against targets in Putrajaya and Johor.80

The practice of Islam in Malaysia is generally regarded by many observers as relatively moderate.81 Nevertheless, the Islamic State, as well as websites and social media pages supportive of it, has drawn support from some extremists and elicited fascination in Malaysian youth. Malaysian IS supporters and sympathizers are active online and, some argue, create a fertile environment for recruitment and further radicalization.82 According to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in spring 2015, 67% of Malaysian Muslims have an unfavorable opinion of IS, but 12% have a favorable opinion.83 The opposition Pan-Malaysia Islamic Party (known by its Malay acronym PAS) publicly disavowed support for IS, but in 2014 senior PAS figures had praised the "sacrifice" of a former PAS youth leader who died fighting in Syria.84 Muslim Brotherhood leader Ismail Faruqui has been described as a mentor of opposition political leader Anwar Ibrahim, formerly Malaysia's Deputy Prime Minister and now an opposition leader. The two were reportedly among the founders of the International Institute for Islamic Thought (IIIT).85

State Responses

Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak and other senior government officials have denounced the Islamic State and have urged Malaysians to withhold support for it and related groups. It was not until September 2014 that the Malaysian government began to freeze assets and funds belonging to individuals or groups involved with the Islamic State. The National Fatwa Council ruled in October 2014 that the participation of Malaysian Muslims in militant groups in Iraq and Syria is contrary to Islamic law and their deaths are not categorized as martyrdom.86 Malaysia, then a member of the Security Council, fully supported U.N. Security Council Resolution 2178, which aims to galvanize international action to combat terrorism in general and the problems posed by foreign terrorist fighters in particular.87 At the same time, the Malaysian government urged the United States and European countries to address the underlying factors that produce terrorism and to win "hearts and minds" rather than solely using force to counter terrorism. In a speech to the U.N. General Assembly in 2014, Najib promoted Malaysia's model of moderate Islam and encouraged individuals, religious leaders, and nations "to advocate for Islamic principles within a framework of tolerance, understanding and peace."88

The emerging danger of terrorists connected to the Islamic State and similar groups has prompted Malaysian law enforcement authorities to be more vigilant. Along with many other South and Southeast Asian countries, Malaysia fears that experienced and radicalized jihadists will return from Syria and Iraq to carry out attacks in their home country; Malaysian officials have raised the possibility of a "Paris-style" attack. The head of the police counterterrorism unit said that IS veterans are "also planning to carry out attacks in Malaysia against the Malaysian government, because for them Malaysia is not an Islamic government; it is OK to topple Malaysia through armed struggle."89 Police have apprehended several Malaysian militants returning from Syria and have arrested dozens of other Malaysians who allegedly intended to emigrate from Malaysia to join terrorist groups in the Middle East. As of mid-March 2016, Malaysian authorities had detained over 160 people connected to the Islamic State.90

Malaysia, like others, faces the threat that IS ideology will inspire individuals to carry out their own attacks and/or form militant groups in the country, even without connections to existing terrorist groups. In August 2014, Malaysian police arrested 19 people involved with a group plotting what officials called "amateurish" bombings against domestic targets and arrested another 17 suspects on similar charges in April 2015.91 According to the Malaysian government, a group inspired by the Islamic State plotted to kidnap Prime Minister Najib and other senior figures, but the police foiled the plan.92 Malaysian authorities are particularly concerned that the territories of Sabah and Sarawak could become a haven for terrorist groups or come under threat from rejuvenated militant groups in nearby areas of the Philippines and Indonesia. Malaysia's 2015 defense budget indicates a shift of attention and resources to Sabah, including two new battalions and new police and military outposts there.93

In response to intensified concerns about terrorism in Malaysia, the Najib government secured passage of new anti-terrorism legislation, the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA), in April 2015. This new law provides sweeping powers to law enforcement authorities to detain suspects without trial for up to 60 days, extendable indefinitely with approval from a Prevention of Terrorism panel. The POTA is especially controversial because the Malaysian government gained these enhanced police powers at a time when many see a growing crackdown on political dissent.94 Many observers inside and outside of Malaysia, including the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, have raised serious concerns about the institution of indefinite detention without trial and the potential for abuse.95 Malaysian officials assert that POTA provides law enforcement measures that are necessary for countering the more dangerous terrorist threat.

Malaysia launched the integrated National Special Operations Force (NSOF) in late 2016. The NSOF will be the first responders to terror threats and attacks in Malaysia. Its personnel will be drawn from the army, navy, coast guard and police. This quick reaction force will comprise 170 personnel and will be based near Kuala Lumpur.96

Counterterrorism Cooperation with the United States and the Region

In response to the increased risks of terrorism threats in the region, in 2014 Malaysia stepped up its counterterrorism cooperation with other Southeast Asian countries and with the United States. The Malaysian Minister of Defense emphasized the need for greater intelligence sharing with Australia, Middle Eastern countries, Indonesia, and the Philippines.97 The Malaysian Home Minister traveled to the United States in October 2014 to meet with officials in the FBI and Department of Homeland Security, stating, "We exchange information about the involvement of Malaysians who are suspected of being terrorists and foreign terrorists who allegedly used Malaysia as a transit to move to other countries."98 In September 2015, Malaysia agreed to join the U.S.-led Global Coalition to Counter ISIL and participate in the coalition's counter-messaging group. Malaysia established a Regional Digital Counter-Messaging Communication Center in 2016 to counter IS messages on social media and to present more appealing alternatives. Reportedly, China is considering providing support to the new center.99 Malaysia already hosts the Southeast Asia Regional Center for Counterterrorism (SEARCCT), which conducts counterterrorism training workshops for officials in the region.

Malaysia established its Advanced Passenger Screening System in 2014. In 2015, Malaysia signed the U.S. Homeland Security Presidential Directive No. 6 and a bilateral agreement for Preventing and Combating Serious Crime, which provide for the exchange of information (even biometric and DNA data) on suspected terrorists between U.S. and Malaysian law enforcement authorities.100 The Malaysian Home Minister stated in March 2016 that the Immigration Department had fulfilled the condition to transmit reports within 24 hours to Interpol on any loss or theft of Malaysian passports.101

Thailand

Thailand is at risk of terrorism for several reasons: a homegrown separatist insurgency in its majority-Muslim southern provinces, relatively open and long borders that allow for international transit of transnational actors and a proliferation of human trafficking networks, and a central government consumed with its own political challenges.102 A U.S. treaty ally since 1954, Thailand has been shaken by extensive political turmoil and two military coups in the past nine years. Since the May 2014 coup, former Army Commander Prayuth Chan-ocha has served as Prime Minister and head of the military junta known as the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO). Although Prayuth declared an end to martial law on April 1, 2015, the junta retains authoritarian powers under a special security measure in the interim constitution. Although the NCPO initially promised that elections would be held in mid-2017, polls have been delayed into 2018, and many observers think that the junta is unwilling to relinquish power even if the polls are held. After the death of Thailand's king in October 2016, the transition to a new king and his demands for changes to the constitution cast further uncertainty about Thailand's political situation.

Primary Groups

Thailand has endured a persistent separatist insurgency in its Muslim-majority southern provinces since the 1940s. The conflict has been particularly active in the last decade; since 2004, violence involving insurgents and security forces has left over 6,700 people dead and over 12,000 wounded, according to local NGOs.103 In 2016, a series of attacks in areas popular with foreign tourists drew concern that the insurgency was expanding beyond the southernmost three provinces. Experts consider the goals of the militant groups active in the area to be mostly separatist rather than jihadist or anti-Western.104 Many observers stress that there is no convincing evidence of serious Jemaah Islamiyah involvement in the attacks, and that the overall long-term goal of the movement in the south remains the creation of an independent state with Islamic governance. Some of the older insurgent organizations, which previously were linked to JI, reportedly have received financial support from foreign Islamic groups, and have leaders who have trained in camps in Libya and Afghanistan.105 The insurgency has, at times, heightened tensions between Thailand and Malaysia, since many of the insurgents' leaders are thought to cross the border fairly easily. Despite these links, foreign elements do not appear to have engaged significantly in the violence.106

Terrorist threats to Thailand are not limited to the southern provinces. On August 17, 2015, a bomb exploded in a busy Bangkok shopping area, killing 20 and wounding over 120. Two Chinese nationals allegedly linked to the Uyghur militant groups were arrested for involvement in the attack. Uyghurs are an ethnic group living primarily in northwestern China that that have been subjected to "severe official repression" by Beijing, according to the State Department's Human Rights Report. Thai authorities claim that the attack was motivated by the repatriation of a large group of ethnic Uyghurs to China weeks before and Bangkok's dismantling of a human trafficking ring.

State Responses

Successive governments in Bangkok—consumed by the political turmoil in Bangkok for the past decade—have struggled to contain the conflict in the South. As the current military government remains preoccupied with its steps toward restoring democratic rule, its strategy to contain conflict in the South has yielded some success, with violence initially declining after picking up again in 2016. The efforts included training local leaders to help protect and patrol their communities from insurgents and participating in peace talks with an umbrella organization of six separatist groups brokered by Malaysia. However, if a pattern of targeting tourist areas or Bangkok develops, the central government may consider unleashing a more aggressive offensive on the militants.

Counterterrorism Cooperation with the United States and the Region

The United States and Thailand have had strong intelligence cooperation, but it is unclear if the tension between the countries due to the military coups has prompted a downgrade of that aspect of the relationship. After the September 11, 2001, attacks on the United States, the two countries' intelligence agencies reportedly shared facilities and information daily.107 The most public result of enhanced coordination was the arrest of suspected Jemaah Islamiyah leader Hambali outside of Bangkok in August 2003. The CIA also maintained at least one black site—where terrorist suspects can be held beyond U.S. jurisdiction—in Thailand.108 It is unclear whether this degree of cooperation has continued as Bangkok has reacted to criticism from the United States about Thailand's suspension of democratic rule. It remains unclear whether the Trump Administration will emphasize intelligence sharing with Thailand or other powers in the region. Many analysts note that Thailand's geographical position and relatively open borders that cater to the large tourism industry mean that intelligence sharing with Bangkok could be a valuable resource in tracking the movement of transnational operatives.

Australia

By most estimates, Muslim radicals represent an extremely small part of Australia's minority Islamic population. Australia has approximately half a million Muslims out of a total population of approximately 23.5 million.109 While Afghan camaleers were among the first Muslims in Australia, many of Australia's Muslims today are of Lebanese, Turkish, Bosnian, Syrian, or other descent. According to one report, 60% of those embracing radicalism in Australia are of Lebanese heritage.110 Analysts observe that the vast majority of Australia's Muslims reportedly are moderate in their beliefs. By one estimate Islamist radicals represent 0.2% of the Muslim population of Australia.111 Others in Australia emphasize that "radicalisation and terrorism are two different phenomena" and that counter-radicalization is but one of many counterterror policy options.112 The history of radical Islamist inspired attacks in Australia can be traced to 1915 when two men of Afghan and Pakistani background attacked a train near Broken Hill, New South Wales, killing four and wounding seven. The attack was motivated by religious grievances over the prohibition of halal slaughter and political allegiance to the Ottoman Sultan, with whom Australia as a part of the British Empire was then at war.113

Primary Groups

Terrorist activity in Australia appears to have increased in recent years due to the effects the Islamic State has had on Islamist militants. The increase in militant activity takes the form of recruitment of those who would fight for the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, the provision of financial or other support to those fighting with the Islamic State in the Middle East, and domestic terrorist attacks carried out by individuals and groups who have followed the Islamic State on social media or possibly have been influenced at Islamic centers in Australia.

Other radical Islamist militant groups originating outside Australia have also been active in Australia or called on jihadists to target Australia. Examples of such activity include an unsuccessful Al Qaeda and Indonesia-based Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) directed plot to attack Jewish and Israeli targets in Sydney during the 2000 Olympics, a Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) plot that was foiled in 2003,114 and a similarly thwarted 2009 Al Shabab associated plot to attack the Holsworthy Army Barracks in Sydney.115 Al Qaeda has also mentioned Australia when calling for attacks against the United States and its allies.116

Terrorists also have targeted Australians in neighboring Indonesia. Two of the largest attacks in Indonesia, both attributed to JI, were centered on Australian targets: An October 12, 2002, bombing of two crowded nightclubs in Bali killed 88 Australians and seven Americans, and JI carried out a bombing of the Australian Embassy in Jakarta in September 2004. (JI also carried out attacks on other Western targets, both in Jakarta and Bali.) Some within JI at that time reportedly set as their goal the establishment of an Islamic state that would encompass Indonesia, Malaysia, the southern Philippines, and Northern Australia.

The Lowy Institute, known as Australia's most prominent think tank, estimated in February 2015 that "around 90 Australians were fighting for Jihadist groups in Syria and Iraq, that up to 30 have returned, and that over 20 have died."117 Between December 2014 and October 2015, Australian authorities reportedly charged 24 people with terrorism-related crimes as a result of nine counterterrorism operations. This total constituted more than a third of all terrorism-related arrests since 2001.118

The Al Risalah Salafist Centre in Sydney, a center closely associated with radicalism and recruitment of IS fighters, was among those sites raided by police in September 2014 in Operation Appleby. The Appleby counterterrorism operation in Sydney and Brisbane was the largest in Australian history involving 800 officers and is thought to have disrupted planned demonstration executions. 119 Afghan-born Baryalei was reported to have possibly been killed in October 2014, shortly after the Appleby raids.

The taking of 17 hostages by self-styled Sheikh Man Haron Monis at the Lindt Cafe at Martin Place in central Sydney in December 2014 did much to reinforce Australian's views of the severity of the terrorist threat from Islamist radicalism. During the 16-hour siege, Monis, who had converted from Shia to Sunni Islam, asked for an IS flag. Police stormed the cafe after Monis killed one of the hostages. As the police stormed the cafe, Monis and another hostage were killed. Monis used Facebook to pledge his allegiance to the "Caliph of the Muslims" six days prior to taking hostages. Reportedly, he had also been under investigation by the Australian Secret Intelligence Organization (ASIO).120

There has not been a major terrorist attack in Australia since the Lindt Cafe attack in 2014. That said, a number of plots reportedly have been foiled, including a January 2017 plot to attack a train station and a cathedral in Melbourne. An electrician was also arrested in February 2017 for allegedly designing a device to warn against incoming guided munitions used by coalition forces in Iraq and Syria and for designing and modeling systems to help IS develop a long range guided missile capability.121 There have been a number of smaller incidents including a stabbing in September 2016. These actions have reportedly led to 57 arrests.122 An estimated 70 Australians have been killed while fighting with IS in Syria and Iraq. Analysts estimate that approximately 100 Australians are fighting with IS and that this represents a decrease from a previous peak of 120.123

State Responses

Australia has undertaken a number of measures to improve its ability to counter Islamist militancy within Australia. Australia has enacted new security laws including enhanced data retention capabilities and has increased funding for intelligence agencies and police.124 In 2014, Prime Minister Abbott amended counterterror legislation to grant intelligence agencies "greater powers to monitor citizens suspected of participating in or otherwise supporting jihadist violence and made it easier to prosecute people promoting extremist propaganda."125 Former Prime Minister Abbott named Ambassador Greg Moriarty National Counterterrorism Coordinator and head of the then newly-formed Counterterrorism Coordination Office.126 More recently, a new National Terrorism Threat Advisory System was put in place in November 2015.127 Following a 2015 attack on police by a 15-year-old, legislation was enacted that lowered the age of control orders for monitoring suspects from 16 to 14.128