What’s on Television? The Intersection of Communications and Copyright Policies

In the 1940s and 1950s, watching television meant tuning into one of a few broadcast television stations, with the help of an antenna, to watch a program at a prescheduled time. Over subsequent decades, cable and satellite operators emerged to enable households unable to receive over-the-air signals to watch the retransmitted signals of broadcast television stations. More recently, some viewers have taken to watching TV programming on their computers, tablets, mobile phones, and other Internet-connected devices at times of their own choosing, dispensing with television stations and cable and satellite operators altogether.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Congress, and the courts have overseen this evolution by applying a combination of communications and copyright laws to regulate the distribution of television programming. These laws are intended to achieve three policy goals:

protecting the property rights of content owners to encourage the production of television programs;

promoting competition among distributors of video programming; and

enabling broadcast television stations to serve the local communities to which they are licensed by the FCC.

The regulatory structure intended to accomplish these goals was established in copyright and communications laws and regulations adopted by Congress and the FCC in the 1970s. These laws and regulations grant broadcast stations exclusive rights to carry programming under certain conditions; allow content owners to control the use of copyrighted content except in certain circumstances; and assign cable and satellite operators both obligations and rights with respect to the stations whose signals they retransmit.

This structure has come under increasing stress as firms offer alternative ways to watch television programming, upsetting established relationships and raising questions about whether the key public policy goals defined by Congress can still be achieved. In particular, firms offering television programming to consumers over the Internet, known as online video distributors (OVDs), are not covered by some of the laws and regulations governing video distribution by providers that rely on their own facilities, such as cable and satellite operators. Station owners, meanwhile, are concerned that relationships between OVDs and broadcast networks could adversely affect stations’ revenues.

Both the House Judiciary Committee and the House Energy and Commerce Committee have announced plans to review and update copyright and communications laws, respectively, while the FCC is considering how and whether to apply its regulations governing the distribution of television signals to a new era. At the same time, federal courts have reached conflicting conclusions as to how copyright laws apply to video programming in the new world of online video distribution. Because of the intertwined relationship between copyright and communications laws, major reform of the regulatory structure governing the distribution of television signals is likely to require Congress or the courts to consider how these two bodies of law intersect.

What's on Television? The Intersection of Communications and Copyright Policies

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- How the Industry Operates

- Changes in Consumer Behavior and Industry Structure

- Exclusivity, Carriage, and Agreements

- Geographic Exclusivity

- FCC Licensing and Localism

- Television Communities vs. Local Television Markets

- Time Exclusivity

- Traditional Linear Programming

- On-Demand Programming

- Online Linear Programming

- FCC Exclusivity Rules

- Network Programming Exclusivity Rules

- Broadcast Television Stations

- Cable Operators

- Satellite Operators

- Syndicated Programming Exclusivity Rules

- Broadcast Television Stations

- Cable Operators

- Satellite Operators

- Statutory Copyright Licenses

- Overview of Statutory Television Copyright Licenses

- Cable Operators

- Small and Medium Systems

- Large Systems

- Satellite Operators

- Distribution of Fees

- Broadcast Signal Carriage Rules and Laws

- Must-Carry and Copyright Laws

- Retransmission Consent and Copyright Laws

- Cable Operators

- Satellite Operators

- Good Faith Negotiations

- Trends in Retransmission Consent Negotiations

- Legal and Policy Developments

- Exclusivity Rules

- Good Faith Negotiations

- Defining OVDs as MVPDs

- FCC Actions

- Court Actions

Summary

In the 1940s and 1950s, watching television meant tuning into one of a few broadcast television stations, with the help of an antenna, to watch a program at a prescheduled time. Over subsequent decades, cable and satellite operators emerged to enable households unable to receive over-the-air signals to watch the retransmitted signals of broadcast television stations. More recently, some viewers have taken to watching TV programming on their computers, tablets, mobile phones, and other Internet-connected devices at times of their own choosing, dispensing with television stations and cable and satellite operators altogether.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Congress, and the courts have overseen this evolution by applying a combination of communications and copyright laws to regulate the distribution of television programming. These laws are intended to achieve three policy goals:

- 1. protecting the property rights of content owners to encourage the production of television programs;

- 2. promoting competition among distributors of video programming; and

- 3. enabling broadcast television stations to serve the local communities to which they are licensed by the FCC.

The regulatory structure intended to accomplish these goals was established in copyright and communications laws and regulations adopted by Congress and the FCC in the 1970s. These laws and regulations grant broadcast stations exclusive rights to carry programming under certain conditions; allow content owners to control the use of copyrighted content except in certain circumstances; and assign cable and satellite operators both obligations and rights with respect to the stations whose signals they retransmit.

This structure has come under increasing stress as firms offer alternative ways to watch television programming, upsetting established relationships and raising questions about whether the key public policy goals defined by Congress can still be achieved. In particular, firms offering television programming to consumers over the Internet, known as online video distributors (OVDs), are not covered by some of the laws and regulations governing video distribution by providers that rely on their own facilities, such as cable and satellite operators. Station owners, meanwhile, are concerned that relationships between OVDs and broadcast networks could adversely affect stations' revenues.

Both the House Judiciary Committee and the House Energy and Commerce Committee have announced plans to review and update copyright and communications laws, respectively, while the FCC is considering how and whether to apply its regulations governing the distribution of television signals to a new era. At the same time, federal courts have reached conflicting conclusions as to how copyright laws apply to video programming in the new world of online video distribution. Because of the intertwined relationship between copyright and communications laws, major reform of the regulatory structure governing the distribution of television signals is likely to require Congress or the courts to consider how these two bodies of law intersect.

Introduction

Watching television used to mean tuning into one of a few broadcast television stations with the help of an antenna. People living in areas with trees or mountains that interfered with these signals could receive broadcast signals retransmitted by cable television systems, which began operating in the 1940s.1 The emergence of satellite technology in the 1970s enabled television networks and some broadcast stations (known as "superstations") to deliver signals to cable systems from great distances, providing viewers with dozens of alternatives to their local broadcast television stations.2 People living in areas where broadcast reception was poor and cable systems were unavailable installed their own backyard satellite dishes to intercept satellite signals, enabling them to watch programming at home.3 More recently, viewers have taken to watching TV programming on their computers, tablets, mobile phones, and other Internet-connected devices, dispensing with television stations, and cable and satellite operators altogether.

Technological innovation has made this possible, but behind the scenes a thicket of laws and federal regulations govern how television programs make their way to viewers. With each innovation in the distribution of television, Congress, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and the courts have applied a combination of communications and copyright laws to regulate the conditions under which cable and satellite operators may retransmit the signals of television stations.

Three key public policies are intertwined:

- 1. protecting the property rights of the copyright owners to encourage the production of television programs;

- 2. promoting competition among distributors of video programming; and

- 3. enabling broadcast television stations to serve the local communities to which they are licensed by the FCC.

The Copyright Act, as amended in 1976 (with respect to cable operators) and in later years (with respect to satellite operators), governs the rights of owners of copyrights to programming carried in retransmitted broadcast television signals. Based on the Copyright Act, the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB), which is composed of three administrative judges appointed by the Librarian of Congress,4 sets the rates cable and satellite operators pay copyright owners for this programming. A combination of communications statutes and FCC regulations govern the retransmission of broadcast television signals by cable and satellite operators.

This regulatory and legal structure has come under increasing stress as firms offer alternative ways to watch television programming, upsetting established relationships and raising questions about whether the key public policy goals defined by Congress can still be achieved. In particular, firms offering television programming to consumers over the Internet, known as online video distributors (OVDs), are not covered by some of the laws and regulations governing video distribution by providers that rely on their own facilities, such as cable and satellite operators.

Both cable and satellite operators have special, technology-specific copyright exemptions with respect to programming contained within retransmitted broadcast television signals. Federal courts have reached conflicting conclusions about the extent to which some OVD services are covered by existing copyright laws.

The FCC is proposing to modify its regulations governing the retransmission of broadcast television signals by cable and satellite operators to cover certain OVDs in order to promote competition among distributors of video programming. Due to the disparity between copyright laws applying to OVDs and MVPDs, however, creating legal and economic parity between them is not a matter entirely within the FCC's jurisdiction.

In addition, the FCC suggests that some of its existing regulations may no longer be necessary to enable broadcast television stations to serve their local communities.

Both the House Judiciary Committee and the House Energy and Commerce Committee have announced plans to review copyright and communications laws, respectively.5 Because of the intertwined relationship between copyright and communications laws, major reform of the regulatory structure is likely to require Congress or the courts to consider how copyright and communications laws intersect.

How the Industry Operates

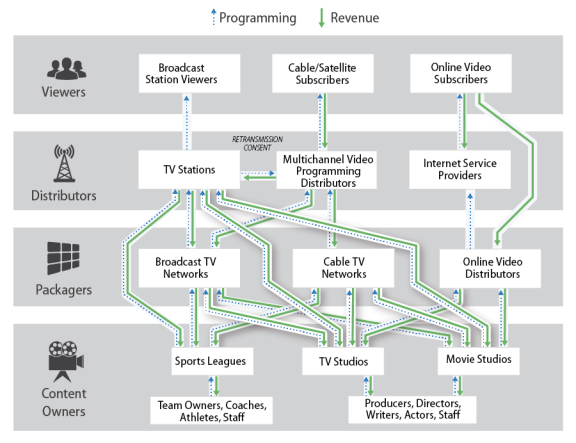

The television industry comprises many players. While the terms describing the roles of the players are not standardized, the following framework offers a way to understand the relationships among industry participants. Individual corporations may operate in one or more of the following categories:

- Content owners hold the copyrights to television programs, movies, and sporting events. Content owners may create the content themselves, or pay producers to create the content for them. Generally, content owners license or sell the copyrights to television programs to television networks or broadcast television stations. Examples of content owners include television studios, movie studios, and sports teams. In addition, television networks and broadcast stations may own the copyrights to programs they produce themselves.

- Packagers assemble various television series, movies, and sporting events. Generally, packagers license content from content owners and resell it to cable operators, satellite operators, broadcast television stations, and OVDs. They may also sell packages of programs directly to consumers. Examples of packagers include cable networks, broadcast networks, and certain types of online distributors of video programming. Broadcast stations, by assembling programming from broadcast television networks, studios, sports leagues, and their own news departments, also operate as packagers.

- Distributors deliver television programs to consumers over their own facilities. They purchase from packagers the rights to "publicly perform" television programming, as defined in copyright law, and to retransmit that programing to viewers. Congress has defined a class of distributors, multichannel video programming distributors (MVPDs), that have certain rights and obligations under copyright and communications laws. These include the right and/or obligation to retransmit the signals of broadcast television stations. MVPDs distribute programs, including the retransmitted signals of broadcast stations, via cables, telephone lines, or satellite dishes on the viewer's premises. Thus, MVPDs comprise cable operators and satellite operators. Because broadcast television stations can deliver programming directly to viewers via over-the-air broadcast signals, they also act as distributors, but are not MVPDs.

The Big Bang Theory, a popular television series, illustrates these industry interactions. Chuck Lorre Productions hires writers, directors, actors, and staff to produce episodes of the show under a contract with Warner Brothers Television Studio (Warner Brothers), which acquires the copyright to the content.6 Warner Brothers, in turn, has sold the Columbia Broadcasting System (the CBS broadcast network), a packager, the exclusive right to offer the episodes produced for the current broadcast season. Separately, Warner Brothers licenses the right to show past seasons of The Big Bang Theory to the Turner Broadcasting System (TBS), a cable network with the same corporate parent, and to local broadcast television stations owned and operated by 21st Century Fox.7 Thus, TBS and broadcast television stations airing The Big Bang Theory also act as packagers. The CBS network's broadcast station affiliates, the TBS cable network, and the local broadcast stations that have licensed rights to past seasons all rely on MVPDs to distribute their programs to the MVPDs' subscribers. TBS and many of the broadcast stations receive payment from the MVPDs. Viewers who do not subscribe to MVPDs may receive The Big Bang Theory directly from broadcast television stations via over-the-air reception.

Figure 1 depicts the complex relationships within the television industry in simplified form.

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. Note: Many companies fall into multiple categories, or have multiple operations within a category. |

Changes in Consumer Behavior and Industry Structure

Most of the 116 million U.S. television households continue to rely on broadcast television stations or MVPDs to receive television programming. Approximately 86% of U.S. television households subscribe to an MVPD service. About 11% of U.S. television households receive broadcast signals "over the air" from a television station. The remaining 3% rely exclusively on an Internet connection to watch television programming.8

|

Number of Households (Millions) |

Percentage of Television Households |

Percentage of MVPD Subscribers |

|

|

Cable |

52.0 |

44.6% |

52.1% |

|

Direct broadcast satellite |

34.5 |

29.7% |

34.5% |

|

Telco Television (primarily Verizon FiOS and AT&T U-Verse) |

13.4 |

11.5% |

13.4% |

|

Over the air |

13.1 |

11.2% |

|

|

Broadband (Internet service provider) only |

3.9 |

3.3% |

|

|

Total television households |

116.4 |

100% |

Source: CRS analysis of data from the Nielsen Company. The Nielsen Company, The Total Audience Report Q4 2015, March 2016, p. 26; The Nielsen Company, Nielsen Estimates 116.4 Million TV Homes in the U.S. for the 2015-16 Television Season, August 28, 2015, http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2015/nielsen-estimates-116-4-million-tv-homes-in-the-us-for-the-2015-16-tv-season.html.

Notes: Numbers are approximate due to rounding; some households may subscribe to multiple services.

Since Congress enacted the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992 (1992 Cable Act; P.L. 102-385) to foster competition in the delivery of video programming services, the number of cable subscribers has declined. In 1993, the FCC reported that 60% of U.S. television households, about 57.4 million, subscribed to cable.9 As of the fourth quarter of 2015, the Nielsen Company estimated that 45% of U.S. television households, about 52 million, subscribed to cable.10 Within the last 22 years, the emergence of alternative distributors of television programming, including satellite operators, has increased competition.

Mergers between MVPDs have nonetheless increased concentration among video programming distributors, enabling some operators to reach large numbers of customers. The reach of these larger MVPDs has increased their bargaining power with respect to negotiating distribution agreements with television stations, television networks, and copyright owners. Consolidation among broadcast stations, television networks, and copyright owners has increased their bargaining power as well. On both sides of these video distribution negotiations, large companies have leverage over smaller companies.

As described in Table 2, many leading companies in the television industry are engaged in multiple aspects of television production, packaging, and distribution. Companies are in frequent negotiation with one another for the right to transmit cable network programming or to retransmit broadcast signals. In some cases, these negotiations are governed directly by communications and copyright laws, as when MVPDs negotiate with broadcast television stations for the right to carry broadcast signals.11 In other instances, negotiations over the right to broadcast or resell programming are based more on market forces and reciprocal relationships, with fewer government-imposed strictures.

|

CBS |

Comcast |

Disney |

21st Century Fox |

Time Warner Entertainment |

|

|

DISTRIBUTORS |

|||||

|

Broadcast stations |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

MVPD |

— |

X |

— |

— |

— |

|

Retail Internet service providers (broadband access) |

— |

X |

— |

— |

— |

|

PACKAGERS |

|||||

|

Broadcast network(s) |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

National cable networks |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Online video distributor(s) |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

CONTENT OWNERS |

|||||

|

Television studio(s) |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Movie studio(s) |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Sports team(s) |

— |

X |

X |

— |

— |

Sources: Company annual reports and websites; Federal Communications Commission, "Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition in the Market for the Delivery of Video Programming, Sixteenth Report," 30 FCC Record 3417-3431, April 2, 2015.

Notes: Properties of CBS include those of Viacom Inc. The FCC considers the two companies to be commonly owned.

Exclusivity, Carriage, and Agreements

Television programs are distributed to viewers in multiple formats and versions. A key concept underlying agreements between the various players in the television industry is "exclusivity." Exclusivity—that is, unique rights to show programing to viewers—is delineated by both time and geography. Distinct time periods of viewing are called "windows."12 Distinct geographical zones of exclusivity are called "local television markets." Copyright laws, by giving content owners control over the distribution of their content, enable content owners to enforce window and market exclusivity. However, the copyright laws contain limitations with respect to the geographic exclusivity of broadcast signals retransmitted by MVPDs.

Geographic exclusivity is reinforced by communications laws and regulations administered by the FCC. In general, these laws and regulations are intended to protect broadcast stations' exclusive rights to distribute television programming within local television markets. One of the policy goals is to enable stations to generate sufficient revenue to cover the costs of producing local news that meets the needs of the viewers in their communities.

Geographic Exclusivity

FCC Licensing and Localism

The FCC licenses broadcast television station owners for eight-year terms to use the public airwaves, or spectrum, in exchange for operating stations in "the public interest, convenience and necessity," pursuant to Section 310(d) of the Communications Act.13

In 1952, the FCC formally allocated television broadcast frequencies among local communities.14 The basic purpose of the allocation plan was to provide as many communities as possible with sufficient spectrum to permit one or more local television stations "to serve as media for local self-expression."15 The allocations made in 1952 are still in use, and formed the basis of the assignment of digital channels to local communities in 2009.

Beginning in July 1952, FCC initially processed applications under a priority designed to bring broadcast television quickly to major cities and surrounding areas without television service.16 Once the FCC felt it met this goal in 1953, it gave priority consideration to cities that had no local television stations of their own.17 In practice, this meant that the first broadcast television networks, CBS and the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), chose affiliates from among the first television stations that went on the air in large cities.

Television Communities vs. Local Television Markets

Up until the mid-1960s, television audience research firms Nielsen and Arbitron Inc. (which has since exited the business) restricted their measurement of television station viewership to the major metropolitan areas that were the first to receive broadcast television stations.18 The estimated number of viewers a station attracts is important in determining the prices that television stations can charge advertisers, and thus plays a significant role in a station's ability to generate revenue. After hearings in the House of Representatives produced accusations that stations licensed to large cities were pressuring the rating services not to measure audiences of stations licensed to smaller cities,19 Arbitron, and subsequently Nielsen, assigned each U.S. county to a unique geographic television market in which they could measure viewing habits.20 Nielsen's construct, known as Designated Market Areas (DMAs), has been widely used to define local television markets since the late 1960s.21

Today, Nielsen measures television audiences in 210 DMAs. A single DMA may overlap multiple states. Although the FCC has assigned television frequencies to 825 separate communities, the 210 DMAs generally define the geographic zones of exclusivity for the transmission of broadcast television programming over the air and retransmission via cable and satellite operators. Carriage and copyright laws also use DMAs to define geographic markets. The policy rationale is that protecting broadcast stations' rights to geographic exclusivity enables them to invest in local programming that is responsive to viewers living within the stations' communities of license. In some instances, however, FCC regulations adopted in the 1950s and 1970s (some of which still form the basis of copyright regulations) rely on the stations' communities of license, rather than DMAs, to define geographic exclusivity.

Time Exclusivity

Traditional Linear Programming

The 1934 Communications Act, as amended by the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984 (P.L. 98-549), defines "video programming" as "programming provided by, or generally considered comparable to programming provided by, a television broadcast station."22 Both broadcast television stations and MVPDs distribute video programming at prescheduled times. MVPDs transmit prescheduled programming from cable networks and retransmit prescheduled programming from broadcast television stations. The FCC refers to this type of video programming distribution as "linear."23

Broadcast stations' contractual agreements with television networks give them the exclusive rights to the initial linear airing (also known as the "first run") of network television broadcasts in their geographic markets. Traditionally, studios have negotiated with cable networks and broadcast television station groups for the right to air broadcast television programs on a linear basis years after their initial air dates. This window of distribution is known as "syndication."

On-Demand Programming

OVDs became significant in 2005, when ABC and NBC reached agreements with Apple Inc. to permit Apple's iTunes store to sell individual episodes of current season broadcast network programs the day after their initial air date. Since then, networks have negotiated directly with OVDs and MVPDs to make their programs available on an on-demand basis.24

OVDs use a variety of business models. The largest OVDs, including Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, and Hulu, allow viewers to watch unlimited content by purchasing a subscription. Another group of OVDs, including Apple's iTunes, Amazon Video,25 Google Play, and Microsoft Movies and TV, allows customers to pay for specific content, either for a single viewing or for a period of time. A third type of OVDs allows viewers to watch a limited number of programs on request in exchange for watching advertisements. Examples include Sony's Crackle and Disney's ABC Go.26

The ability of networks to license their programs to these OVDs depends on the agreements they reach with the studios that own the copyrights to the programs. To facilitate the process, broadcast networks are increasingly airing programs created by studios owned by their corporate parents.27

Licensing from third-party studios may give networks less control over the distribution of programs after their initial broadcast. For example, in March 2016, Warner Brothers and the ABC broadcast network reached an agreement that gives ABC "in-season stacking rights"—that is, the exclusive right to distribute the current season's episodes—to television programs produced by the studio, but Warner Brothers retains the ability to sell distribution rights after each season is completed and to license individual programs to online retailers such as iTunes.28

At the same time, networks have expressed a desire to license on-demand availability of their programming to MVPDs rather than OVDs such as Netflix. The networks' ability to sell advertising and retain control over their own brands when their programs are distributed by MVPDs, in combination with the fees MVPDs pay them, makes MVPD distribution more valuable to them in the long term than OVD distribution.29

Not all involved in the creation of television programs agree with this strategy. In 2015 the cast and producers of the television series Bones, which is produced by 20th Century Fox Television Studios and airs on the FOX television network, sued the parent company of both, 21st Century Fox, Inc. In the lawsuit, the plaintiffs alleged that they received "tens of millions" of fewer dollars than they otherwise would have, as a result of the studio making "sweetheart" distribution deals with its commonly owned network (FOX), television stations, and OVD (Hulu).30 For example, the plaintiffs alleged that because 21st Century Fox sold in-season stacking rights to Hulu, Netflix paid less for older seasons of the program than it would have otherwise.

Networks' ability to offer MVPDs online and on-demand rights is also a key issue in negotiations between broadcast networks and their affiliates.31 According to the vice president of Broadcast Markets for Media General, Inc., "Exclusivity to our business partnership is important to local stations and there are more and more opportunities these days for that exclusivity to be challenged."32

Online Linear Programming

Broadcast stations' network affiliation agreements give them the exclusive rights to the initial linear airing of network television broadcasts within their DMAs. For example, under its network affiliation agreement with CBS, KTVO in Kirksville, MO, has exclusive rights to linear broadcasts one day before and seven days after CBS delivers the program to the station.33

These arrangements have been challenged as OVDs have offered programming on a prescheduled basis. The FCC refers to these as "subscription linear" services. To date, OVDs have offered linear programming from broadcast networks only in DMAs in which those networks own their affiliates. For example, in February 2016, Sling TV, a service offered by DISH Network, a satellite distributor, began to offer programming from the ABC network, but only in selected markets in which ABC owns and operates its affiliated broadcast stations.34 Similarly, in April 2016, Sling TV began to offer programming from the FOX network in DMAs in which FOX owns and operates its affiliated broadcast stations.35

The agreements between broadcast networks and local television affiliates make it difficult for OVDs to offer linear broadcasting on a nationwide basis. There appears to be disagreement between broadcast networks and affiliate stations about which entity may negotiate with subscription linear OVDs and about how the entities will split the money the OVDs pay to license their programming.36 Stations, which have the legal rights to negotiate directly with cable and satellite and satellite operators for the retransmission of their signals (see "Broadcast Signal Carriage Rules and Laws") do not wish to cede this option with respect to linear Internet transmission of broadcast network programs.

FCC Exclusivity Rules

Federal regulations enable broadcast television stations to enforce contractual provisions that make them the exclusive distributors of linear programming within geographic zones based on their communities of license. Specifically, the FCC's exclusivity rules provide broadcast stations with a means of enforcing contractual exclusivity provisions between stations and program suppliers, including both broadcast networks and studios that license syndicated programming.

These rules apply to television stations as well as cable and satellite distributors. In general, they respond to congressional concern about the availability of local news, weather, emergency, and community-oriented programming. The FCC has consistently taken the view that the importation of distant television signals carrying the same programming as a local station could divert the local station's audience, diminishing the station's advertising revenues and threatening its ability to serve the local community.37

The geographic zones in which broadcast stations may exercise their exclusivity rights vary, depending on the distribution technology. When the FCC first adopted exclusivity rules in the 1940s with respect to broadcast stations, the zones coincided with the station's communities of licenses. When the FCC adopted exclusivity rules with respect to cable operators in the 1970s and subsequently extended them to satellite operators, it based the zones on a 35-mile radius from a designated center of the stations' communities of license.

Network Programming Exclusivity Rules

Broadcast Television Stations

FCC rules enable a broadcast network affiliate to prevent another station licensed to the same community from affiliating with that network.38 The FCC first adopted these "territorial exclusivity" rules with respect to broadcast television in November 1945 without analysis or comment, and amended them in 1955 to redefine the geographic zone of exclusivity.39 Of the FCC's six exclusivity rules, this is the only one with a geographic zone contiguous with the boundaries of the station's city of license.

Cable Operators

In 1975, the FCC applied the concept of exclusivity to network programs redistributed by cable operators.40 Since 1988, the exclusivity protection has pertained to any time period specified in the contractual agreement between the network and the affiliate.41 These are known as network non-duplication rules.

The rules require cable operators to black out broadcast network programming from television stations imported by a cable operator into a local station's "zone of protection." The zone of protection extends 35 miles from a station's city of license in the 100 largest markets and 55 miles in smaller markets.42 If an affiliate and a broadcast network agree to a smaller zone of protection, that zone applies. The 35-mile radius is based on specified reference points in each designated community. These reference points, which define boundaries of television markets, are listed in the FCC's rules at 47 C.F.R. §76.53.

Satellite Operators

The non-duplication rules applicable to satellite operators differ from those applicable to cable operators. The satellite network non-duplication rules apply only to "nationally distributed superstations."43 These superstations, of which there are now five, are broadcast stations not affiliated with ABC, CBS, FOX, or NBC, and delivered nationally to MVPDs via satellite.44 With limited exceptions, satellite operators cannot import distant network broadcast stations where local stations are available, either over the air or via satellite operators.45 Thus, if a satellite operator were to carry a superstation, it would need to black out network programming carried by that superstation if the programming is also carried by a local station. The geographic zone of protection for broadcast stations applicable to satellite operators is the same as that applicable to cable operators (i.e., 35 miles).46

Syndicated Programming Exclusivity Rules

Broadcast Television Stations

FCC rules enable a broadcast station to prevent another station licensed to the same community from airing the same syndicated programming.47 After first adopting these rules in 1973, the FCC increased the zone of exclusivity in 1974 to 35 miles.48 This is greater than the "city of license" geographic zone the FCC uses for the network exclusivity rules with respect to broadcast television stations.49 Similar to the network exclusivity rules that apply to cable and satellite operators, the 35-mile radius is based on specified reference points in each designated community in a television market. In 1988, the FCC modified the rule to allow stations to purchase the rights to air syndicated programming on a national basis, thereby allowing superstations to exercise exclusivity rights.50

Cable Operators

Like the network non-duplication rules for cable, the FCC's syndicated exclusivity rules for cable allow a local commercial broadcast television station to protect its exclusive distribution rights within a 35-mile zone surrounding its city of license.51 This zone may not exceed the zone defined in the exclusivity contract between the station and syndicator. Thus, if a cable operator were to import the signal of a distant station carrying a syndicated program, it would have to black out the program to subscribers living within 35 miles of the designated reference point in the city of the local station with rights to carry the same program. The cable operator could provide substitute programming during that time slot. Unlike the network non-duplication rule, the zone of protection is the same for all markets.

Satellite Operators

The Satellite Home Viewer Improvement Act (SHVIA; P.L. 106-113) directed the FCC to apply its cable syndicated exclusivity rules for satellite operators only with respect to the retransmission of nationally distributed broadcast superstations. The FCC issued a parallel but distinct set of syndicated exclusivity rules for satellite operators.52 The FCC uses the same geographic zone as it does for its cable syndicated exclusivity rules (i.e., 35 miles from the television station's city of license).53

Statutory Copyright Licenses54

When the FCC first established exclusivity rules with respect to cable operators in 1972, its action, under the authority of the Communications Act of 1934, was closely related to a parallel debate about the applicability of copyright law to cable operators.55 As the FCC later explained, "cable television systems [at that time] operated outside of the traditional program supply markets as a result of the operation of the Copyright Act of 1909, creating what was viewed as unfair competition between cable television systems and television broadcast stations."56

According to Senator John McClellan, who in the early 1970s was chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Patents, Trade-Marks, and Copyrights, the question of copyright liability for cable operators was "the only significant obstacle faced to final action by the Congress on a [new] copyright bill" to update the original Copyright Act from 1909.57 After several copyright updates proposed in Congress failed to pass, Clay J. Whitehead, the director of the Office of Telecommunications Policy in the White House under President Richard M. Nixon, proposed a "take it or leave it" compromise in 1971. This compromise, endorsed by then FCC Chairman Dean Burch and Senator McClellan, provided for (1) exclusivity rules to be adopted by the FCC and (2) a commitment on the part of broadcast stations, cable operators, and studios to support separate copyright legislation providing for compulsory licensing.58 This 1971 compromise is still cited as a reason why the FCC should not repeal its current exclusivity rules absent Congress's repeal of statutory copyright licensing.59

Overview of Statutory Television Copyright Licenses

Generally, copyright owners have the exclusive legal right to publicly "perform"60 their works, and, as is the case with online distribution of their programs, to license their works to distributors in marketplace negotiations.61 The Copyright Act, as amended in 1976 (with respect to cable operators) and in later years (with respect to satellite operators), limits these rights for owners of programming contained in retransmitted broadcast television signals. Cable operators and satellite operators are guaranteed the right to publicly perform the copyrighted broadcast television programming, as long as they abide by FCC regulations and pay royalties to content owners at rates set and administered by the government. In some instances cable and satellite operators need not pay content owners at all, because Congress set a rate of $0.

The Copyright Act contains three statutory copyright licenses governing the retransmission of distant and local television broadcast station signals:

- 1. The cable statutory license, codified in Section 111, permits cable operators to retransmit both local and distant television station signals.62 This license relies in part on former and current FCC rules and regulations as the basis upon which a cable operator may transmit distant broadcast signals.

- 2. The local satellite statutory license, codified in Section 122, permits satellite operators to retransmit local signals on a royalty-free basis. To use this license, satellite operators must comply with the rules, regulations, and authorizations established by the FCC governing the carriage of local television signals.

- 3. The distant satellite statutory license, codified in Section 119, permits satellite operators to retransmit distant broadcast television signals. Congress has renewed this provision in five-year intervals. In 2004, Congress inserted a "no distant if local" provision, which prohibits satellite operators from importing distant signals into television markets where viewers can receive the signals of broadcast network affiliates over the air. Section 119 sunsets on December 31, 2019.63

Under the statutory license, cable and satellite operators make royalty payments every six months to the U.S. Copyright Office, an agency of the Library of Congress. The head of this office, the Register of Copyrights, places the money in an escrow account and maintains the "Statement of Account" that each operator files. The Copyright Royalty Board (CRB), which is composed of three administrative judges appointed by the Librarian of Congress,64 is charged with distributing the royalties to copyright claimants. It also has the task of adjusting the rates at five-year intervals, and annually in response to inflation.

Cable Operators

Congress established the statutory licensing regime for cable operators as part of the Copyright Act of 1976.65 The compulsory license became effective on January 1, 1978. The law divides cable operators into three classes: small, medium, and large, depending upon how much money they earn from video subscriptions. Each class pays a different rate. The CRB may periodically adjust the benchmarks used to determine a cable operator's size to reflect inflation or the prices cable systems charge subscribers.66

Small and Medium Systems

Both small and medium cable systems pay a fixed percentage of their revenues, based on a formula specified in the Copyright Act.67 According to the House Judiciary Committee report, smaller systems are likely to be located in regions unable to receive broadcast signals over the air, thereby requiring them to rely to a greater extent on the importation of distant signals. In addition, they may be less able than larger systems to afford copyright payments.68 Small and medium systems incur their full liability under the compulsory license with the first broadcast television signal they retransmit.69

Large Systems

The fees paid by large cable systems differ from those paid by small and medium systems in several ways:

- 1. Rather than paying a percentage of their revenues, large systems pay royalties based on the number and type of "distant broadcast signals" retransmitted. Distant signals are defined as signals retransmitted by a cable system, in whole or in part, outside the local service area of the primary transmitter.70

- 2. Even if they carry no distant signals, large systems must pay "for the privilege of further transmitting any nonnetwork programming."71 This fee may be applied against the system's distant signal liability.

In calculating the prices owed by large cable operators, Congress made two key distinctions: (1) local versus distant signals and (2) network versus nonnetwork programming. Cable operators do not pay content owners fees for programming contained in retransmitted local signals or for network programming contained in retransmitted distant signals. They do, however, pay content owners of nonnetwork programming contained in retransmitted distant broadcast signal.72

The 1976 Copyright Act stipulated that the Copyright Royalty Tribunal (now the CRB) may adjust the royalty rates in the event that after April 1976, the FCC

- 1. permitted cable operators to import additional distant television signals, and/or

- 2. amended its syndicated exclusivity rules.73

In 1980, the FCC repealed both its quotas on the number of distant signals cable operators could import and its syndicated exclusivity rules.74 After the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld the FCC's decision,75 the FCC's new rules became effective on June 25, 1981. The Copyright Royalty Tribunal adjusted the rates, effective January 1983.76 Although the FCC reinstated a modified version of the syndicated exclusivity rules in 1988,77 the Copyright Royalty Tribunal's 1983 adjustments remain in effect.78

As stipulated in the Copyright Act, when a cable operator retransmits the broadcast station's signal within the station's DMA, it does not pay the content owners for the right to publicly "perform" their programs. However, if the cable operator retransmits the station's signal outside the station's DMA, it pays the content owners a government-set rate based in part on the station's estimated amount of syndicated and other nonnetwork programming.79

Satellite Operators

Congress established a statutory licensing regime for satellite operators with respect to the importation of distant broadcast signals in 1988 on a temporary basis,80 and with respect to retransmission of local broadcast signals in 1999 on a permanent basis.81 Since its inception in 1988, Congress has reauthorized the compulsory licensing regime for distant signals retransmitted by satellite operators five times: in 1994, 1999, 2004, 2010, and 2014.82

Similar to large cable operators, satellite operators retransmitting local stations need not pay a fee to the content owners. In order to be eligible for this local compulsory license, however, the satellite operators must comply with FCC rules.83 The conference committee report specified that the required compliance may extend to programming exclusivity rules.84

In 2015, the CRB announced that based on its interpretation of the congressional intent behind the enactment of the Satellite Television Extension and Localism Act Reauthorization in 2014 (STELAR; P.L. 113-200), a proceeding to determine rates for the statutory license covering the period 2015-2019 was not necessary.85 The rates will only be subject to an annual adjustment to reflect inflation. For the year 2016, satellite operators pay a rate of $0.27 per month for each residential subscriber in an area that is unable to receive the over-the-air signals of broadcast network affiliate. A portion of those fees accrue to owners of the copyrights on the programs that are retransmitted.

Distribution of Fees

Every six months, cable and satellite operators must file statements of account with the Copyright Office and pay royalty fees. The operators must identify the broadcast signals they have retransmitted. The Copyright Office collects the royalty fees and invests them in government securities until the fees are allocated and paid to the copyright owners. The CRB is charged with authorizing the distribution of royalty fees and resolving royalty claim disputes.

Copyright owners of any work included in a distant, nonnetwork secondary broadcast retransmission86 may form groups to negotiate and allocate royalties. Copyright owners have organized themselves into claimant groups based upon content categories. For programming retransmitted by both cable and satellite, the categories have traditionally been (1) movies and syndicated television series, (2) sports programming, (3) commercial broadcaster-owned programming, (4) religious programming, and (5) music.87

Allocation of the royalties collected occurs either through a negotiated settlement among the parties or, if the claimants do not reach an agreement, through a CRB proceeding. In Phase I of a cable or satellite royalty distribution proceeding, the CRB allocates royalties among certain categories of broadcast programming that have been retransmitted by the operators. In Phase II, the CRB allocates royalties among claimants within each of the Phase I categories. The Copyright Act grants claimants immunity from the antitrust laws in connection with any agreement among themselves as to the division and distribution of royalties from cable operators.88

Broadcast Signal Carriage Rules and Laws

From the 1960s through the late 1980s, a centerpiece of the FCC's regulation of cable operators was the requirement that cable operators carry any broadcast television signal considered to be "local" upon the station's request.89 Neither Congress nor the FCC gave broadcast television stations the right to negotiate for carriage. The courts voided the FCC's "must-carry" rules in 1985.90 Thus, from 1985 to 1992, cable operators paid neither copyright holders nor broadcast television stations for the right to retransmit local broadcast signals. In 1989, the FCC recommended that Congress reexamine the compulsory license with a view toward replacing it with a regime of full copyright liability for retransmission of both distant and local signals.91

Instead, Congress retained the statutory licensing regime of the Copyright Act, and addressed broadcast stations' control over the retransmission of their signals in the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992 (1992 Cable Act; P.L. 102-385), which amended the Communications Act. Under this law, MVPDs may not redistribute a broadcast signal to their customers unless they have obtained the permission of the broadcast station that originated the signal. When granting permission, commercial stations have two options:

- "Must-carry" gives a station the right to require carriage by cable operators, and to a more limited extent, satellite operators, serving subscribers located within the DMA served by the station. Commercial stations airing programming from religious broadcasters or other programming that may appeal to a specialized audience often choose this option, because they believe MVPDs might not be willing to pay significant amounts to retransmit their programming.92

- "Retransmission consent" gives a station the right to negotiate for payment in exchange for carriage by cable and satellite operators serving subscribers located within the station's DMA. By choosing this option, a station runs the risk of failing to reach an agreement with the cable or satellite carrier and therefore not being carried.

In determining which stations were local, Congress decided that a third-party commercial research service, rather than a government agency, should define the boundaries of a station's local market. A television station was entitled to must-carry status on all cable systems located in the same market.93

Must-Carry and Copyright Laws

Whether a station is local or distant for copyright purposes can affect whether a station is entitled to mandatory carriage. Section 614 of the Communications Act of 1934 provides that a station that would be considered distant under Section 111 of the Copyright Act is not considered local unless the station agrees to indemnify the cable operator for any copyright liability resulting from carriage on that system.94

Between 1992 and 1994, when the statutory copyright laws still relied on the mileage-based definitions of local market, several stations petitioned the FCC to be considered local for copyright purposes. Section 3(b) of the Satellite Home Viewer Act of 1994 (SHVA; P.L. 103-369) amended statutory license markets to conform to FCC's definition of markets for the purposes of implementing must carry. These geographic zones determine the statutory copyright rates that MVPDs must pay content owners for the programming contained in retransmitted broadcast signals. In 1996, the FCC ruled that it would use the DMAs demarcated by the Nielsen Company to define local markets, beginning in 1999.95

The Satellite Home Viewer Improvement Act (SHVIA; P.L. 106-113), enacted in 1999, increased the parity between satellite and cable services. It created a permanent legal and regulatory framework permitting satellite operators to retransmit local broadcast signals ("local-into-local" service). In contrast to the blanket must-carry provisions applying to cable operators, SHVIA applied must-carry provisions to satellite operators on a case-by-case basis. If a satellite operator chooses to carry one station, it generally must carry all qualified stations in the same DMA.96 At the same time it imposed new broadcast carriage requirements on satellite operators, SHVIA also limited their copyright liability. 97 If the FCC modifies a market to include additional counties for the purposes of implementing its must-carry/retransmission consent rules, then the modified market would be applicable for compulsory licensing.

Retransmission Consent and Copyright Laws

Cable Operators

Prior to the 1992 Cable Act, with the brief exception of a four-year period between 1968 and 1972, cable operators were not required to seek the permission of broadcast television stations before retransmitting their signals, nor were they required to compensate broadcasters for the right to retransmit their signals. In its report accompanying the 1992 Cable Act, the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation stated that "It is the Committee's intention to establish a marketplace for the disposition of the rights to retransmit broadcast signals; it is not the Committee's intention ... to dictate the outcome of the ensuring marketplace negotiations."98

Satellite Operators

In 1999, in conjunction with allowing satellite operators to retransmit local signals for the first time, SHVIA required the operators to seek broadcasters' permission to retransmit those signals. According to the accompanying conference report, this provision, combined with the permanent statutory license for transmitting local signals, "create[s] parity and enhanced competition between the satellite and cable industries in the provision of local television broadcast stations" while striking a balance between the communications law policy of localism and the copyright law emphasis on property rights.99

Good Faith Negotiations

SHVIA also required broadcast stations to negotiate with both cable and satellite operators in "good faith," subject to marketplace conditions. This good faith obligation expired after five years. In 2004, the Satellite Home Viewer Extension and Reauthorization Act (SHVERA; P.L. 108-447) made the good faith bargaining requirements between MVPDs and broadcasters reciprocal, and extended them for another five years. Congress extended the temporary good faith requirements two more times: in 2010 (P.L. 111-175), and most recently in 2014, in the Satellite Television Extension and Localism Act Reauthorization (STELAR; P.L. 113-200) until January 1, 2020.

Per Se Violations

Beginning in 2000, the FCC implemented the good faith negotiation statutory provisions through a two-part framework.100 First, the FCC initially established a list of seven (subsequently nine) good faith negotiation standards, the violation of which is considered a per se breach of the good faith negotiation obligation.101 In March 2014, the FCC, in a separate proceeding regarding retransmission consent, adopted an order strengthening its retransmission consent rules. Under the rules FCC adopted, joint negotiation by stations that are not commonly owned and are ranked among the top four stations in a market as measured by audience share constitutes a per se violation of the good faith negotiation requirement.102 Through Section 103 of STELAR, Congress subsequently revised Section 325 of the 1934 Communications Act to require the FCC to amend its rules governing the exercise of retransmission consent rights to

prohibit a television broadcast station from coordinating negotiations or negotiating on a joint basis with another television broadcast station in the same local market ... to grant retransmission consent under this section to a[n MVPD], unless such stations are directly or indirectly under common de jure control permitted under the regulations of the Commission.103

The FCC adopted new rules implementing this provision, replacing the previous rule regarding joint negotiation with language consistent with the new statute.104

In addition, Section 103 revised Section 325 of the 1934 Communications Act to require the FCC to amend its rules governing the exercise of retransmission consent rights to "prohibit a television broadcast station from limiting the ability of a[n MVPD] to carry into the local market ... of such station a television signal that has been deemed significantly viewed ... unless such stations are directly or indirectly under common de jure control permitted by the [FCC]."105

The FCC implemented this provision by adding a ninth per se good faith negotiation standard to its rules.106

Totality of Circumstances

Even if MVPDs or broadcast stations do not violate the per se standards, the FCC may determine that based on the "totality of circumstances," a party has failed to negotiate retransmission consent in good faith. Under this standard, a party may present facts to the FCC that, given the totality of circumstances, reflect an absence of a sincere desire to reach an agreement that is acceptable to both parties and thus constitute a failure to negotiate in good faith.

Trends in Retransmission Consent Negotiations

More competition among MVPDs has increased the negotiating leverage of broadcast television stations in retransmission consent negotiations since 1993. At that time, large MVPDs refused to pay broadcast stations for retransmission rights.107 Instead, several broadcast networks negotiated on behalf of their affiliates to gain carriage of new cable networks, and split the proceeds.

As satellite operators and other MVPDs entered the market in competition with cable operators, broadcast stations could encourage the cable subscribers to switch, and vice versa. Broadcast stations began to demand cash in exchange for carriage. For example, in 2005, Nexstar Broadcasting Group, Inc., which negotiated retransmission consent on behalf of its own stations as well as those of Mission Broadcasting, pulled its television signals from cable operators in four television markets. After prolonged negotiations, the cable operators agreed to pay Nexstar for its consent to retransmission.108

Broadcast Networks and Affiliates

Larger cash payments from MVPDs to broadcast stations have changed the relationship between stations and networks. Traditionally, broadcast networks paid affiliates to air network programming. In recent years, however, the networks have instead required that stations pay them "reverse compensation" or "reverse retrans fees" by passing through some of the retransmission consent revenues the stations receive from MVPDs.109 In 2011, CBS President/CEO (and current Chairman) Leslie Moonves stated the following:

We think it's very important we get paid for reverse compensation, and we will. Obviously the network deserves to get paid from the affiliate body. The reason the affiliates are getting compensation is primarily because of primetime [network entertainment programming aired during the evenings] and football. That should be part of the equation.110

According to research firm SNL Kagan, broadcast networks may ask stations to pay them a fixed amount per MVPD subscriber with access to the station's programming, rather than a percentage of retransmission consent payments.111 Several networks, as part of their affiliation agreements, specify that stations pay fees to help them defray the costs of paying copyright holders for their content.112 Thus, although pursuant to the copyright laws, MVPDs do not pay content owners directly for retransmitted broadcast programming, they may pay the content owners indirectly via the payments affiliates make to networks that have licensed the content.

Signal Blackouts

Due to consolidation among both MVPDs and broadcast television station owners, a single retransmission consent negotiation often covers stations and cable systems in many markets. SNL Kagan estimates that negotiations for retransmission consent agreements have grown increasingly contentious, in part because the terms of agreements have become more complex.113 For example, in 2013 CBS pulled the signals of its owned and operated television stations from Time Warner Cable (TWC), reportedly because the cable operator refused to pay CBS extra fees for the right to make CBS programming available to subscribers on an on-demand basis on a variety of devices.114 In addition, TWC reportedly wanted to limit CBS's ability to license programming to Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon, preferring to be the exclusive licensee of in-season stacking rights for CBS programming. After a monthlong standoff, during which CBS limited the ability of TWC's Internet subscribers to view CBS programming online, the parties reached a five-year agreement that included expanded on-demand rights to CBS programming.115 Table 3 illustrates the increasing frequency of blackouts during retransmission consent negotiations.

|

Year |

Number of Retransmission Consent Agreements |

Number of Blackouts |

|

1993 |

2 |

0 |

|

1999 |

2 |

0 |

|

2000 |

26 |

3 |

|

2002 |

1 |

0 |

|

2003 |

4 |

1 |

|

2004 |

3 |

1 |

|

2005 |

21 |

4 |

|

2006 |

9 |

1 |

|

2007 |

14 |

1 |

|

2008 |

27 |

7 |

|

2009 |

28 |

4 |

|

2010 |

21 |

4 |

|

2011 |

45 |

11 |

|

2012 |

79 |

21 |

|

2013 |

40 |

17 |

|

2014 |

76 |

13 |

|

2015 |

45 |

27 |

Source: CRS analysis of data from SNL Kagan.

Notes: The list, based on publicly available data, is not comprehensive. Excludes disputes resolved in 2016.

Legal and Policy Developments

Both the House Judiciary Committee and the House Energy and Commerce Committee have announced plans to review and potentially modernize copyright and communications laws, respectively, in light of technological developments. In the meantime, developments in the television industry, including the emergence of "virtual" cable and satellite operators, have prompted the FCC and courts to reexamine their interpretation of these laws.

Exclusivity Rules

In 2014, the FCC proposed eliminating or modifying its exclusivity rules with respect to satellite and cable operators.116 FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler has noted that since Congress adopted compulsory copyright provisions for cable operators in 1976, Congress passed retransmission consent legislation in 1992 giving broadcasters the right to negotiate with cable and satellite operators for the right to retransmit their signals. Furthermore, he stated that "the presence of the exclusivity rules prohibits the market from operating in a fair and efficient manner and aggravates the harm to consumers during retransmission consent disputes," while their elimination would not trigger any harm, because network affiliation contracts already contain exclusivity provisions.117

The following are among the numerous questions on which the FCC sought comment:

- Would elimination of the exclusivity rules be inconsistent with the intent of the 1992 Cable Act?

- Would elimination of the exclusivity rules go beyond the FCC's statutory authority?

- How would the elimination of the exclusivity rules affect the policy goal of "localism"?

- To what extent do existing network/affiliate agreements prohibit a local broadcaster from allowing its signal to be imported by a distant cable operator without reference to an FCC prohibition?

- To what extent do program suppliers "dilute" broadcasters' exclusivity by making their programming available via alternative outlets (e.g., by licensing programs to cable networks and broadcast stations simultaneously, or to OVDs)?

- How would the rules' elimination affect retransmission consent negotiations?

Good Faith Negotiations

STELAR directed the FCC to update the "totality of circumstances" test in its "good faith negotiations" rules (47 U.S.C. §325(b)(3)(C)). In September 2015, the FCC sought comment on specific practices that it could identify as evidence of bad faith under this test.118 Some of those potentially prohibited practices are those raised by Mediacom Communications Corporation (Mediacom) in a petition for an FCC rulemaking, 119 and other MVPDs and broadcasters who responded to Mediacom's petition. These include the following:

- Broadcast stations' and/or networks' blocking online access to their programing during retransmission consent disputes. In its committee report, the Senate Commerce Committee also directed the FCC to examine the role "digital rights and online video programming have begun to play in retransmission consent negotiations."120

- Broadcast stations' relinquishing to third parties, including broadcast networks and stations located in separate geographic television markets, their right to grant retransmission consent.

- Broadcast stations' bundling of their signals with those of other broadcast stations or cable networks, including networks that have not yet launched. The FCC stated that if a broadcast station requires an MVPD to purchase less popular programming in order to purchase more desired programming, the MVPDs may be forced to pay for programming they do not want and may in turn pass those costs onto consumers.121

The FCC sought comment on 25 additional practices identified that might be inconsistent with the obligation to negotiate in good faith.

Defining OVDs as MVPDs

FCC Actions

In December 2014, the FCC proposed new rules that would expand its definition of an "MVPD" to include OVDs that offer linear programming.122 In singling out these types of OVDs for inclusion, the FCC cites the definition of "video programming" in the 1934 Communications Act.123 The FCC stated that "such an approach will ensure that both incumbent providers will continue to be subject to ... regulations that apply to MVPDs as they transition [the delivery of] their services to the Internet, and that nascent, Internet-based video programming service will have access to the tools they need to compete with established providers."124

Among the questions on which the FCC sought comment are the following:

- whether the FCC should consider the exemption or waiver of certain FCC regulations, if allowed under the statute;

- how expanding the definition of "MVPD" would affect the retransmission consent negotiation process, including requirements to negotiate in good faith;

- how network affiliation agreements affect the carriage of broadcast stations on Internet-based MVPDs;

- how the FCC's expansion of its MVPD definition would interrelate with copyright law.

The FCC noted that even if an OVD qualified as an MVPD under the FCC's rules, it would not be subject to a number of regulations and statutory requirements specifically applicable to cable and satellite operators unless it also qualified as one of those services.125 Among those requirements are the network non-duplication rules and must-carry requirements.

Court Actions

The issue of whether an online distributor of video programming that retransmits the signals of broadcast television stations meets the statutory definition of a "cable system," and is thereby entitled to statutory copyright licensing under 17 U.S.C. §111, has split federal judges over the last two years. Circuit courts in Washington, DC,126 and New York,127 and a district court in Illinois,128 have said online video distributors cannot use the statutory license. A U.S. district court in California, however, ruled that OVDs can use the statutory license.129

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Michael O'Connor, "Mediated," in Ted Turner: a Biography (Santa Barbara: Greenwood Press, 2010), p. 49. |

| 2. |

Home Box Office (HBO) became the first such network in 1975. Erik Gregersen, "Home Box Office, Inc.," Encyclopedia Britannica, last update, September 20, 2015, http://www.britannica.com/topic/HBO. |

| 3. |

Deborah Mesce, "Satellites Offer New Option in TV Viewing," Associated Press, October 26, 1980. |

| 4. |

In 1976 Congress also created a tribunal (consisting of five commissioners appointed by the President) to adjust the royalty rates after 1978 (P.L. 94-553, §§801-810). After replacing the tribunal with an arbitration panel in 1993, Congress established the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB) in 2004 (Copyright Royalty and Distribution Reform Act of 2004, P.L. 108-419, codified at 17 U.S.C. §§801-805). See also Copyright Royalty Tribunal Reform Act of 1993, P.L. 103-198. Congress placed the tribunal, the arbitration panel, and the CRB in the legislative branch. |

| 5. |

House Judiciary Committee, "House Judiciary Committee Announces Next Step in Copyright Review," press release, July 22, 2015, https://judiciary.house.gov/press-release/house-judiciary-committee-announces-next-step-in-copyright-review/. House Energy and Commerce Committee, #CommActUpdate, https://energycommerce.house.gov/commactupdate. |

| 6. |

Leslie Goldberg, "Chuck Lorre, WBTV Ink 4-Year Deal That Includes Film, Cable Components," Hollywood Reporter, September 5, 2012, http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/live-feed/chuck-lorre-warner-bros-television-overall-deal-film-cable-drama-368132. |

| 7. |

Cynthia Littleton, "TBS, Fox Get 'Big Bang,'" Variety, May 10, 2010, http://variety.com/2010/tv/news/tbs-fox-get-big-bang-1118019393/. |

| 8. |

For additional information about the role of Internet service providers in distributing video programming, see CRS Report R44122, Charter-Time Warner Cable-Bright House Networks Mergers: Overview and Issues, by Dana A. Scherer. |

| 9. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition in the Market for the Delivery of Video Programming, First Report, FCC 94-235," 9 FCC Record 7442, 7548-7549, September 27, 1994. This was the first time the FCC published the congressionally mandated annual report. |

| 10. |

The Nielsen Company, The Total Audience Report, December 10, 2015, pp. 21-22. http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/reports/2015/the-total-audience-report-q3-2015.html. |

| 11. |

See CRS Report R43490, Reauthorization of the Satellite Television Extension and Localism Act (STELA), by Dana A. Scherer. |

| 12. |

For a detailed description of the concept of "windowing," see Jeffrey C. Ulin, The Business of Media Distribution: Monetizing Film, TV, and Video Content in an Online World (Burlington, MA: The Taylor & Francis Group, 2014). |

| 13. |

47 U.S.C. §310(d). |

| 14. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Rules Governing Television Broadcast Stations, Sixth Report and Order," 17 Federal Register 3905, 3912-3914, May 2, 1952. |

| 15. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, Regulation of Community Antenna Systems, committee print, 89th Cong., 2nd sess., June 17, 1966, 1635, p. 7. |

| 16. |

Ibid., p. 110. |

| 17. |

Federal Communications Commission, Twentieth Annual Report to Congress for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1954, 1955, p. 90. |

| 18. |

Karen S. Buzzard, Chains of Gold: Marketing the Ratings and Rating the Markets (Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1990), pp. 121-122 (Buzzard). |

| 19. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, Special Subcommittee on Investigations, The Methodology, Accuracy, and Use of Ratings in Broadcasting, 106th Cong., 1st sess., March 7, 1963 (Washington: GPO, 1963), pp. 203-228. |

| 20. |

Buzzard, pp. 128-133. See also "Slicing the Demographic Pie," Sponsor, February 27, 1967, pp. 27, 29. |

| 21. |

John S. Armstrong, "Constructing Television Communities: The FCC, Signals, and Cities, 1948 - 1957," Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, March 2007. |

| 22. |

47 U.S.C. §522(20). |

| 23. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Promoting Innovation and Competition in the Provision of Multichannel Video Programming Distribution Services," 29 FCC Record 15995, 16001, nn. 26-67, December 19, 2014 (2014 FCC MVPD Definition NPRM). |

| 24. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition in the Market for Delivery of Video Programming, Fourteenth Report," 27 FCC Record 8610, 8779-8780, July 19, 2012 (FCC 14th Annual Video Competition Report). For background information about the launch of MVPDs' "TV Everywhere" initiatives designed to compete with OVDs, see Ronald Grover, Tom Lawry, and Cliff Edwards, "Revenge of the Cable Guys," Bloomberg Businessweek, March 22, 2010, http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/magazine/content/10_12/b4171038593210.htm#p3. |

| 25. |

Amazon.com Inc. operates both a subscription OVD service, Amazon Prime Video, and a transactional OVD service, Amazon Video. |

| 26. |

Categories of OVDs derived from 2014 FCC MVPD Definition NPRM, p. 16001, and FCC Fourteenth Annual Report, pp. 8722, 8726. See also Chris Roberts and Vince Muscarella, Defining Over-the-Top Digital Distribution, Digital Electronic Merchants Association, 2015, http://www.entmerch.org/digitalema/white-papers/defining-digital-distributi.pdf. |

| 27. |

Joe Flint, "Broadcasters Shop at Home for Shows," Wall Street Journal, May 27, 2015. Typically, major sports leagues retain online distribution rights for games, offering desktop and mobile access directly to consumers. SNL Kagan, The State of Online Video Delivery, 2015 Edition, Charlottesville, VA, 2012, pp. 18-19. |

| 28. |

Cynthia Littleton, "ABC, Warner Bros. TV Group Set Broad Agreement for In-Season Stacking Rights to Shows," Variety, March 16, 2016, http://variety.com/2016/tv/news/abc-warner-bros-stacking-rights-shows-on-demand-1201732797/. |

| 29. |

Peter Kafka, "Can the TV Guys Put the Netflix Genie Back in the Bottle?," re/code, October 3, 2015, http://recode.net/2015/11/03/can-the-tv-guys-put-the-netflix-genie-back-in-the-bottle/. |

| 30. |

Shalini Ramachandran, "Bones' Cast and Producers Take on Fox Over Fees," Dow Jones Institutional News, December 1, 2015. See also Austin Siegemund-Broka and Matthew Belloni, "'Bones' Stars file New Lawsuit for 'Tens of Millions' in Fox Profits," Hollywood Reporter, November 30, 2015. Other producers have expressed similar concerns with respect to networks offering Hulu stacking rights. Shalini Ramachandran, "Streaming Era Sets Off Battle Over TV Rights," Wall Street Journal, November 28, 2015. Hulu is a joint venture of 21st Century Fox (FOX), Disney (ABC), and Comcast's NBCUniversal (NBC). |

| 31. |

SNL Kagan, Economics of Broadcast TV Retransmission Consent Revenue, 2014 Edition, Charlottesville, VA, 2014, p. 25. |

| 32. |

Adam Buckman, "Nets Hold Upper Hand in Affiliate Relations," TVNewscheck, January 7, 2015, http://www.tvnewscheck.com/article/82002/nets-hold-upper-hand-in-affiliate-relations. |

| 33. |

See Affiliation Agreement between CBS Affiliate Relations, a Unit of CBS Corporation (CBS), and Barrington Kirksville LLC, dated May 1, 2010, https://stations.fcc.gov/collect/files/21251/Ownership%20Reports/CBS%20Affiliate%20Agreement%20%2814038180730340%29.pdf. |

| 34. |

Sarah Perez, "Cord Cutting Service Sling TV Gets Its First Broadcast Channel with Addition of ABC," TechCrunch, February 19, 2016, http://techcrunch.com/2016/02/19/cord-cutting-service-sling-tv-gets-its-first-broadcast-channel-with-addition-of-abc/. |

| 35. |

Todd Spangler, "Dish's Sling TV Launches Multi-Stream Plan Stocked With Fox Nets, but Without ESPN," Variety, April 13, 2016, http://variety.com/2016/digital/news/dish-sling-tv-fox-multistream-espn-1201752423/. |

| 36. |

Keach Hagey, "Local TV Creates Hurdle to Streaming," Wall Street Journal, September 3, 2015. |

| 37. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Amendment of the Commission's Rules Related to Retransmission Consent, Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking," 29 FCC Record 3351, 3386, March 31, 2014. |

| 38. |

47 C.F.R. §73.658(b). |

| 39. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Rules Governing Broadcast Television Stations," 11 Federal Register 33, 37 January 1, 1946. Federal Communications Commission, "Amendment of Television 'Territorial Exclusivity Rules,'" 12 Pike and Fischer Radio Regulation 1537-1538, 1541, 1543, June 24, 1955. The original rule read, "No license shall be granted to a television station having any contract, arrangement, or understanding, express or implied, with a network organization ... which prevents or hinders another broadcast station serving a substantially different area [emphasis added] from broadcasting any program of the network organization." |

| 40. |

Federal Communications Commission, "Amendment of Subpart F of Part 76 of the Commission's Rules and Regulations with Respect to Network Program Exclusivity Protection by Cable Systems," 52 FCC Reports, Second Series 519, April 14, 1975. |

| 41. |