College and University Endowments: Overview and Tax Policy Options

Colleges and universities maintain endowments to directly support their activities as institutions of higher education. Endowments are typically investment funds, but may also consist of cash or property. Current tax law benefits endowments and the accumulation of endowment assets. Generally, endowment fund earnings are exempt from federal income tax. The 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97), however, imposes a new 1.4% excise tax on the net investment earnings of certain college and university endowments. Taxpayers making contributions to college and university endowment funds may be able to deduct the value of their contribution from income subject to tax. The purpose of this report is to provide background information on college and university endowments, and discuss various options for changing their tax treatment.

This report uses data from the U.S. Department of Education, the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) and Commonfund Institute, and the Internal Revenue Service to provide background information on college and university endowments. Key statistics, as discussed further within, include the following:

In 2017, college and university endowment assets were $566.8 billion. Endowment assets have been growing, in real terms, since 2009. Endowment asset values fell during the 2007-2008 financial crisis, and took several years to fully recover.

Endowment assets are concentrated, with 12% of institutions holding 75% of all endowment assets in 2017. Institutions with the largest endowments (Yale, Princeton, Harvard, and Stanford) each hold more than 4% of total endowment assets.

The average spending (payout) rate from endowments in 2017 was 4.4%. Between 1998 and 2017, average payout rates have fluctuated between 4.2% and 5.1%. In recent years, institutions with larger endowments have tended to have higher payout rates.

In 2017, endowment assets earned a rate of return of 12.2%, on average. Larger institutions tended to earn higher returns. Larger institutions also tended to have a larger share of assets invested in alternative strategies, including hedge funds and private equity.

Changing the tax treatment of college and university endowments could be used to further various policy objectives. Current-law tax treatment could be modified to increase federal revenues. The tax treatment of college and university endowments could also be changed to encourage additional spending from endowments on specific purposes (tuition assistance, for example).

Policy options discussed in this report include (1) a payout requirement, possibly similar to that imposed on private foundations, requiring a certain percentage of funds be paid out annually in support of charitable activities; (2) modifying the excise tax on endowment investment earnings; (3) a limitation on the charitable deduction for certain gifts to endowments; and (4) a change to the tax treatment of certain debt-financed investments in strategies often employed by endowments.

College and University Endowments: Overview and Tax Policy Options

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- What Is an Endowment?

- Tax Treatment of College and University Endowments

- Excise Tax on Net Investment Income of Certain Institutions

- Comparing the Tax Treatment of Endowments and Private Foundations

- College and University Endowments: Data Overview

- Endowment Balances

- College and University Endowments: FY2017

- Largest Private College and University Endowments

- Payouts from College and University Endowments

- Endowment Fund Investments

- Returns on Endowment Fund Investments

- Where Are Endowment Funds Invested?

- Policy Considerations and Options

- Modify Tax on Endowment Net Investment Income

- Impose a Payout Requirement

- Tax Endowments or Impose Additional Taxes on Endowment Earnings

- Limit or Enhance Charitable Deductions for Gifts to Endowments

- Change Policies for Certain Offshore Investments

- Increase Data Reporting

Figures

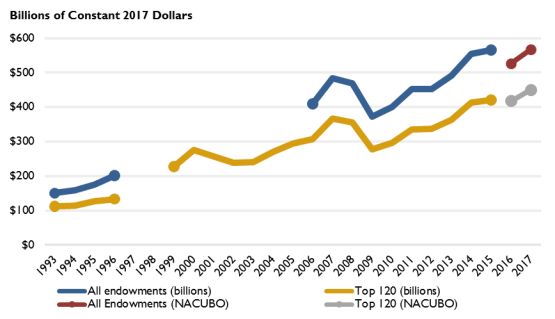

- Figure 1. Endowment Balances, 1993- 2017

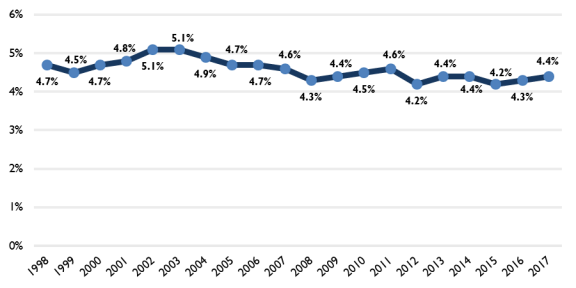

- Figure 2. Average Annual Effective Spending (Payout) Rate, 1998-2017

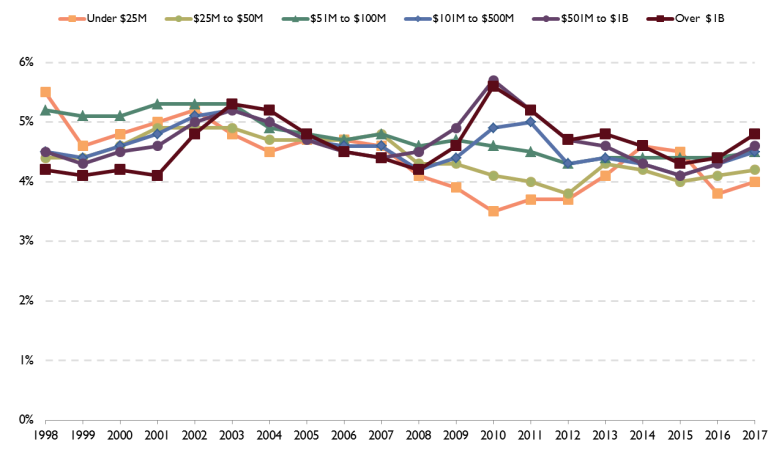

- Figure 3. Average Annual Effective Spending (Payout) Rate by Endowment Size, FY1998 - FY2017

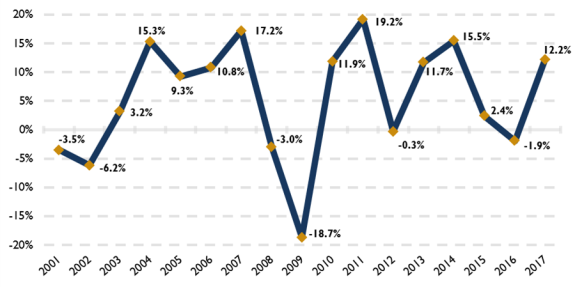

- Figure 4. Average Net Returns, FY2001 - FY2017

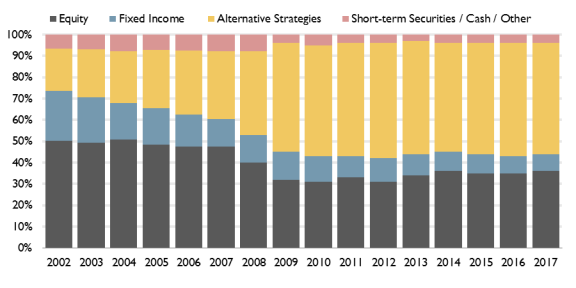

- Figure 5. Asset Allocations for U.S. College and University Endowments, FY2002 – FY2017

Tables

- Table 1. Endowments and Institutions by Endowment Size, FY2017

- Table 2. Private Institutions with Endowments of at Least $500,000 per Student and 500 Students

- Table 3. Endowment Value Per Full-Time Equivalent Student, FY2017

- Table 4. Endowment Characteristics by Size of Endowment, FY2017

- Table 5. Rate of Return by Endowment Size and Time Period

- Table A-1. Endowments of 501(c)(3) Higher Education Institutions, 2011-2014

- Table A-2. Endowment Payouts of 501(c)(3) Higher Education Institutions, 2014

- Table B-1. Top 100 College and University Endowments, FY2017

- Table C-1. Top 25 Private Institutions by Endowment Assets per Student

Summary

Colleges and universities maintain endowments to directly support their activities as institutions of higher education. Endowments are typically investment funds, but may also consist of cash or property. Current tax law benefits endowments and the accumulation of endowment assets. Generally, endowment fund earnings are exempt from federal income tax. The 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97), however, imposes a new 1.4% excise tax on the net investment earnings of certain college and university endowments. Taxpayers making contributions to college and university endowment funds may be able to deduct the value of their contribution from income subject to tax. The purpose of this report is to provide background information on college and university endowments, and discuss various options for changing their tax treatment.

This report uses data from the U.S. Department of Education, the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) and Commonfund Institute, and the Internal Revenue Service to provide background information on college and university endowments. Key statistics, as discussed further within, include the following:

- In 2017, college and university endowment assets were $566.8 billion. Endowment assets have been growing, in real terms, since 2009. Endowment asset values fell during the 2007-2008 financial crisis, and took several years to fully recover.

- Endowment assets are concentrated, with 12% of institutions holding 75% of all endowment assets in 2017. Institutions with the largest endowments (Yale, Princeton, Harvard, and Stanford) each hold more than 4% of total endowment assets.

- The average spending (payout) rate from endowments in 2017 was 4.4%. Between 1998 and 2017, average payout rates have fluctuated between 4.2% and 5.1%. In recent years, institutions with larger endowments have tended to have higher payout rates.

- In 2017, endowment assets earned a rate of return of 12.2%, on average. Larger institutions tended to earn higher returns. Larger institutions also tended to have a larger share of assets invested in alternative strategies, including hedge funds and private equity.

Changing the tax treatment of college and university endowments could be used to further various policy objectives. Current-law tax treatment could be modified to increase federal revenues. The tax treatment of college and university endowments could also be changed to encourage additional spending from endowments on specific purposes (tuition assistance, for example).

Policy options discussed in this report include (1) a payout requirement, possibly similar to that imposed on private foundations, requiring a certain percentage of funds be paid out annually in support of charitable activities; (2) modifying the excise tax on endowment investment earnings; (3) a limitation on the charitable deduction for certain gifts to endowments; and (4) a change to the tax treatment of certain debt-financed investments in strategies often employed by endowments.

Over the past decade, the size and growth of college and university endowments has attracted the attention of academicians and policymakers.1 In 2008, Senator Chuck Grassley and Representative Peter Welch convened a roundtable discussion entitled "Maximizing the Use of Endowment Funds and Making Higher Education More Affordable."2 More recently, discussion of endowments featured heavily in a House Ways and Means Committee hearing on "The Rising Costs of Higher Education and Tax Policy."3 In 2016, the House Committee on Ways and Means held a hearing focusing exclusively on tax-exempt college and university endowments.4 The 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97) included a new excise tax on the net investment income of certain college and university endowments.5

At the end of FY2017, endowment balances for the 809 institutions included in the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO)-Commonfund Study of Endowments totaled $566.8 billion.6 In inflation-adjusted terms, endowment balances trended upwards through most of the 1990s and 2000s. Endowment balances declined sharply during the financial crisis that began in 2008, but subsequently recovered. Strong investment returns have contributed to this growth in endowment balances. For 2017, endowments earned an average return of 12.2%. Over time, an increasing proportion of endowment funds have been invested in "alternative strategies," including private equity and hedge funds. Large endowments are more likely than smaller endowments to have their funds invested in alternative strategies.

Spending, or payouts, from endowments supports various higher education activities. The spending rate, or payout rate, has fluctuated over time. For 2017, the payout rate for NACUBO institutions was 4.4%. On average, in recent years, institutions with the largest endowments have tended to have payout rates that exceeded average payout rates for institutions with smaller endowments.

This report begins by providing background information on college and university endowments, and discussing their current-law tax treatment. The report then reviews available data and trends related to endowment balances, payout rates, and investment returns. The report concludes with a discussion of several policy options to change the current tax treatment of college and university endowments.

What Is an Endowment?

A college or university's endowment fund—often referred to simply as an endowment—is an investment fund maintained for the benefit of the educational institution. Endowments may also hold cash or property. Income from the endowment is used to cover the cost of the college or university's operations and capital expenditures, to fund special projects, or for reinvestment. Typically, a college or university endowment includes hundreds, if not thousands, of individual funds that are the result of various agreements between donors and the recipient institution.

There are several types of endowment funds. Donors may give funds to a true endowment, or permanent endowment. Oftentimes, donors impose restrictions on the institutions spending the principal balance of true endowments. Donors may also impose restrictions on the use of income earned on true endowments. True endowments may contain funds that the donors have dedicated to scholarships or faculty support, for example.

A term endowment is an endowment where funds may be restricted by the donor for some period of time. After the set period of time has passed, unused funds or principal may become unrestricted.

Institutions may also put other unrestricted funds, such as those from general gifts or bequests, in the institution's endowment. These funds are typically referred to as a quasi-endowment. Typically, when looking at the total value of an institution's endowments, true endowments, term endowments, and quasi-endowments are included.

Of the $566.8 billion in endowment assets reported to NACUBO in 2017, $255.3 billion (45%) was in a true endowment, while $135.4 billion (24%) was in a quasi-endowment.7 Of the true endowment balance, $233.3 billion was donor restricted (41% of total endowment market value). The reported term endowment balance was $12.3 billion (2%).8

Tax Treatment of College and University Endowments

Endowments are tax-exempt for one of two reasons. Either they are part of a university which is tax-exempt as a 501(c)(3) organization or a government entity (public universities), or the endowment itself has 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status.9 Contributions to 501(c)(3)s and government entities are generally tax deductible to the contributor under Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 170. Another benefit of an endowment's tax-exempt status is that, except for the recent excise tax on the net investment income of endowments at certain institutions, the investment earnings are tax free.10

The 501(c)(3) status of colleges and universities—and by extension their endowments—is a result of them being organized and operated exclusively for purposes listed in Section 501(c)(3), specifically charitable and educational purposes.

If the return from endowments of colleges and universities were taxed currently at 35%, the revenue gain is estimated at $15.3 billion; taxed at the new corporate rate of 21%, the amount would be $9.9 billion.11 If only private universities and colleges were subject to a tax, the gain would be estimated at $10.4 billion at a 35% rate and $6.4 billion at a 21% rate, since public institutions are responsible for 32% of assets.12 This figure can be compared with the estimated value of other tax provisions that directly benefit educational institutions. These include the deduction for charitable contributions to educational institutions, estimated to reduce revenues by $10.5 billion in FY2017 (while the deduction is claimed by individuals and corporations, the benefit also accrues to institutions of higher education); private activity tax-exempt bonds for nonprofit educational institutions, estimated at $3.8 billion; and the share of general obligation tax exempt bonds benefits that accrue to public institutions of higher education, which are estimated at around $1.4 billion.13 These benefits total approximately $15.7 billion.14 Beginning in 2018, the value of these provisions would be expected to be somewhat smaller under the new tax rules.15

Excise Tax on Net Investment Income of Certain Institutions

A 1.4% tax on net investment income is imposed annually on certain private colleges and universities beginning in tax years after December 31, 2017.16 For the purposes of the tax, net investment income is gross investment income and net capital gain, less expenses associated with earning that income. Gross investment income includes income from interest, dividends, rents, and royalties.

To be subject to the tax, private colleges and universities must meet the following criteria:

- 1. have at least 500 tuition-paying full-time equivalent (FTE) students in the previous tax year (with more than 50% of these students located in the United States);17 and

- 2. have assets of at least $500,000 per student (excluding assets that are used directly in carrying out the institution's exempt educational purpose).18

Institutions that are subject to the tax and meet the above criteria are referred to as "applicable educational institution[s]."

IRC Section 4968 is a new provision. Per the Conference Report accompanying P.L. 115-97, it is

intended that the Secretary promulgate regulations to carry out the intent of the provision, including regulations that describe: (1) assets that are used directly in carrying out the educational institution's exempt purpose; (2) the computation of net investment income; and (3) assets that are intended or available for the use or benefit of the educational institution.19

The IRS has not yet released any guidance or regulations related to the new excise tax under IRC Section 4968.

The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that the excise tax on net investment income of private colleges and universities with endowments of at least $500,000 per student would raise $1.8 billion in revenue over the 2018 through 2027 budget window.20 Annually, the tax is estimated to raise about $0.2 billion.21

Comparing the Tax Treatment of Endowments and Private Foundations

Comparisons are often drawn between private foundations and college endowments, particularly when considering certain policy options (payout requirements, for example). Unlike private foundations, college endowments are not subject to a payout requirement. Private foundations are differentiated from tax-exempt public charities by their narrow bases of control and financial support.22 In order to limit accumulation of tax-exempt funds by foundations, Congress chose to require private foundations (and only private foundations) to pay out at least 5% of their fund every year under Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 4942.23

Private foundations are also subject to an excise tax on net investment income.24 The tax rate is 2%, but is reduced to 1% if the foundation's qualifying distributions exceed a historical average.

When the tax on investment income of private foundations was enacted, Congress stated that the purpose of the tax was to have private foundations share in the cost of government oversight of the sector.25 Revenues from the tax, however, go to the general fund and are not earmarked for any specific purpose.

College and University Endowments: Data Overview

Endowment Balances

There are several sources of data on endowment balances. Specifically, data on endowments can be obtained from the following sources:

- U.S. Department of Education: The U.S. Department of Education publishes data on endowment funds. Generally, information is provided on total endowment funds for all public and private colleges and universities and separately for the top 120 institutions. At the end of FY2015 (June 30, 2015), all institutions reported endowment funds of $547.2 billion.26 The 120 institutions with the largest endowments held $406.4 billion, or 74.3% of the total.

- National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO): NACUBO regularly gathers endowment data from a large number of public and private colleges and universities and affiliated foundations.27 At the end of FY2017 (June 30, 2017), 809 institutions reported $566.8 billion in endowment assets.28 The NACUBO survey provides the most up-to-date information on endowments, although it may not include the same institutions included in the U.S. Department of Education data.

- Internal Revenue Service: Data on endowments of 501(c)(3) (private) universities and colleges are reported on Schedule D of IRS Form 990 informational returns. IRS data representing 1,782 501(c)(3) higher education institutions reported $390.2 billion in endowment assets for 2014.29

Historically, the aggregate endowment values reported in the NACUBO survey have closely tracked the endowments data published by the Department of Education. While the Department of Education data includes all Title IV institutions, the NACUBO survey gathers information on endowments from some affiliated foundations in their survey.30

There have been fluctuations in endowment balances over time. Overall, endowment balances have increased substantially since the early 1990s, both in nominal and real (inflation-adjusted) terms (Figure 1 shows trends in endowment balances since 1993, in inflation-adjusted terms). In 1993, endowment balances were $150.8 billion (inflation-adjusted to 2017 dollars). By 2015, endowment balances were $565.9 billion (inflation-adjusted). While the Department of Education has not yet released data for 2017, data from the NACUBO survey, which closely tracks Department of Education statistics on endowments, reported endowment assets of $566.8 billion for 2017. The share of endowments held by the top 120 institutions (the Department of Education regularly reports data on endowments held by the top 120 institutions) has remained roughly the same over time, at around 75%.

Endowment values decreased substantially during the 2007-2008 financial crisis, and took several years to recover to precrisis levels. In 2007, endowments were valued at $484.4 billion (in inflation-adjusted 2017 dollars). Balances had declined to $372.0 billion (inflation-adjusted) by 2009. By 2013, inflation-adjusted endowment balances had reached $491.1 billion, before increasing further to $565.9 billion in 2015.

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of Department of Education and NACUBO data. Notes: Data are inflation adjusted using the Consumer Price Index (CPI-U). Data from 1993 through 2015 are from the National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, various years. Endowment data for all institutions are not available for 1997 through 2005. From 1993 through 1996 and again from 1999 through 2015, the National Center for Education Statistics reported endowment values for the top 120 institutions. Between 1999 and 2005, the Digest of Education Statistics reported data on the endowments of the top 120 institutions, with their source for the data being NACUBO. The data points for 2016 and 2017 are endowment values from the NACUBO survey. |

College and University Endowments: FY2017

For the fiscal year ending June 30, 2017, data gathered by NACUBO from 809 universities and colleges reported total endowment assets of $566.8 billion. As illustrated in Table 1, endowment balances are heavily concentrated in a small share of institutions, with 12% of institutions holding 75% of endowments. Private nonprofit universities (classified as "independent" in Table 1) have a slightly higher share of endowments (68%) relative to their share of institutions (63%).

|

Endowment Size in 2017 |

Share of Institutions (%) |

Share of Endowments (%) |

||||

|

Over $1 billion |

|

|

||||

|

$0.5 billion - $1.0 billion |

|

|

||||

|

$0.1 billion - $0.5 billion |

|

|

||||

|

$0.05 billion - $0.1 billion |

|

|

||||

|

$0.025 billion - $0.05 billion |

|

|

||||

|

Under $0.025 billion |

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Public |

|

|

||||

|

Independent |

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Full Sample (Equal Weighted) |

|

|

Source: NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowment, 2017, publicly available data at https://www.nacubo.org/Research/2009/Public-NCSE-Tables.

Notes: Data collected from 809 institutions holding $566.8 billion of endowment assets. Canadian institutions were not included.

Largest Private College and University Endowments

In FY2017, according to NACUBO data, there were 31 private colleges and universities with endowments of at least $500,000 per student and 500 students (see Table 2).31 A list of the 100 largest college and university endowments, including public institutions can be found in Appendix B. A list of the 25 private institutions with the largest endowment per student, including institutions with less than 500 students, can be found in Appendix C.

Harvard University had the largest endowment in FY2017, totaling more than $36.0 billion. On a per-student basis, Harvard's endowment was $1.5 million in FY2017. A total of five institutions had total endowment assets of $15.0 million or more, and a per-student endowment of at least $1.3 million (Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Princeton, and MIT). Endowment wealth is highly concentrated in these top institutions, with Harvard holding 6.4% of all endowment assets reported to NACUBO in FY2017. Yale held 4.8% of endowment assets in that same year, with Princeton holding 4.2% of endowment assets.

Table 2. Private Institutions with Endowments of at Least $500,000

per Student and 500 Students

End of FY2017 Endowment Assets and Fall 2016 Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) Students

|

Institution |

FY2017 Endowment Assets ($ billions) |

Share of Total Endowment Assets |

Endowment Value per Student |

|||||

|

Princeton University |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Yale University |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Princeton Theological Seminary |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Stanford University |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Harvard University |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Pomona College |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Amherst College |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Swarthmore College |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Williams College |

|

|

|

|||||

|

California Institute of Technology |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Grinnell College |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Rice University |

|

|

|

|||||

|

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Wellesley College |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Bowdoin College |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Dartmouth College |

|

|

|

|||||

|

University of Notre Dame |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Baylor College of Medicine |

|

|

|

|||||

|

The Medical College of Wisconsin Inc. |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Washington and Lee University |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Berea Collegea |

|

|

|

|||||

|

University of Richmond |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Smith College |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Claremont McKenna College |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Northwestern University |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Washington University in St. Louis |

|

|

|

|||||

|

University of Pennsylvania |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Bryn Mawr College |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Duke University |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Trinity University |

|

|

|

Source: NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowment, 2017, publicly available data at https://www.nacubo.org/Research/2009/Public-NCSE-Tables.

Notes: This table is not intended to represent a list of institutions subject to the net investment income tax. The NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments includes data as voluntarily reported by participating institutions, which may not reflect endowment values as reported to the IRS. Additionally, under the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, the net investment income tax is not applicable to institutions with fewer than 500 tuition-paying students.

Endowment assets are concentrated in private doctoral-granting universities. In FY2017, the average endowment per student at private doctoral-granting universities was $360,787 (the median was $74,767) (see Table 3). The average endowment per student at public doctoral-granting universities was $27,092 (with a median of $23,012).

|

Doctoral |

Master's |

Bachelor's |

||||

|

Private, Nonprofit, 4-Year Institutions |

|

|

|

|||

|

Mean |

|

|

|

|||

|

Median |

|

|

|

|||

|

Public, 4-Year Institutions |

|

|

|

|||

|

Mean |

|

|

|

|||

|

Median |

|

|

|

Source: CRS calculations using NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments 2017, publicly available data at https://www.nacubo.org/Research/2009/Endowment-Market-Values-and-Investment-Rates-of-Return.

Notes: Values reflect endowment assets as of June 30, 2017. Enrollment data reflect Fall 2016 FTE enrollment. Full-time equivalent (FTE) enrollment is self-reported by the institutions.

Payouts from College and University Endowments

Spending from the endowment includes expenditures on student financial aid, faculty research, maintenance of facilities, and other campus operations. The spending rate, or payout rate, is this spending divided by the market value of the endowment at the beginning of the year (net of administrative expenses). Most institutions have a spending policy, where the payout rate is tied to a moving average of endowment value.32 Colleges and universities may deviate from predetermined spending policies, particularly in the face of negative financial shocks like the 2008-2009 financial crisis.33

NACUBO publishes data on average annual effective spending rates from endowment funds, or payouts. Since 1998, the average annual effective spending rate, or average payout rate, has fluctuated within a one-percentage-point band, hitting a period high of 5.1% in 2003 and period low of 4.2% in 2012 (see Figure 2). In 2017, the average payout rate was 4.4%.

|

Figure 2. Average Annual Effective Spending (Payout) Rate, 1998-2017 |

|

|

Source: NACUBO and Commonfund Institute, NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowment, years 2007-2017, publicly available data at https://www.nacubo.org/Research/2009/Public-NCSE-Tables. Notes: Average annual effective spending rates are calculated as endowment spending on student financial aid, faculty research, maintenance of facilities, and other campus operations, divided by endowment value at the beginning of the fiscal year. Average payout rates are equal-weighted across institutions. |

Spending (payout) rates also varied across different types of institutions in FY2017. Data presented in Table 4 show that the average payout rate was higher for private institutions (4.6%) when compared to public institutions (4.1%). The NACUBO data indicate that average payout rates in 2017 tended to increase with endowment size. The average payout rate was 4.8% for endowments with assets above $1 billion, with lower payout rates for smaller endowment size classes.

Data on endowments of 501(c)(3) colleges and universities collected by the IRS can also be used to examine payout behavior. IRS data from 2014 indicate the average payout for 501(c)(3) institutions was 4.3% (see Table A-2). For institutions with large endowments (more than $1 billion in 2014), roughly half had payout rates between 3.8% and 4.9% in 2014. There is a wider distribution of payout rates across institutions with smaller endowments.

|

Size of Endowment, 2017 |

Spending (Payout) Rate |

||

|

Over $1 billion |

|

||

|

$0.5 billion - $1.0 billion |

|

||

|

$0.1 billion - $0.5 billion |

|

||

|

$0.05 billion - $0.1 billion |

|

||

|

$0.025 billion - $0.05 billion |

|

||

|

Under $0.025 billion |

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

Type of Institution |

|

||

|

All Public Institutions |

|

||

|

All Private Colleges and Universities |

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

Average (All Institutions) |

|

Source: NACUBO and Commonfund Institute, NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowment, years 2007-2017, publicly available data at https://www.nacubo.org/Research/2009/Public-NCSE-Tables.

Notes: Average annual effective spending rates calculated as endowment spending on student financial aid, faculty research, maintenance of facilities, and other campus operations, divided by endowment value at the beginning of the fiscal year. Average payout rates are equal-weighted across institutions.

Trends in payout rates over time have differed for institutions with large endowments as opposed to smaller endowments (see Figure 3). Payout rates generally trended downward between 2003 and 2008 (the average payout rate was 5.1% in 2003, as opposed to 4.3% in 2008). While average payouts trended upwards from 2008 through 2011, during that time, a gap developed between the average payout rate of institutions with endowments of $0.5 billion or more, and those with smaller endowments of less than $0.05 billion. In 2010, the average payout rate for institutions with endowments between $0.5 billion and $1 billion, and those with average endowments above $1 billion, was 5.7% and 5.6%, respectively. The average payout rate for institutions with an endowment between $0.025 billion and $0.05 billion was 4.1% in 2010, while the average payout rate for institutions with endowments of less than $0.025 billion was 3.5%.

These trends suggest that during and in the period immediately following the Great Recession, institutions with larger endowments tended to increase payout rates. Institutions with large endowments, where spending from endowments funds a significant portion of operating expenses, tend to base payouts on average endowment values in recent years (often over a three-year period).34 Thus, payout rates tend to increase when endowments decline. Where payout rates tended to decline during and immediately following the Great Recession was among institutions with smaller endowments. As the economy has recovered, payout rates for institutions with large and smaller endowments have again converged and are close to the average across all institutions (4.4%).

|

Figure 3. Average Annual Effective Spending (Payout) Rate by Endowment Size, FY1998 - FY2017 |

|

|

Source: NACUBO and Commonfund Institute, NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowment, years 2007-2017, publicly available data at https://www.nacubo.org/Research/2009/Public-NCSE-Tables. Notes: Average annual effective spending rates are calculated as endowment spending on student financial aid, faculty research, maintenance of facilities, and other campus operations, divided by endowment value at the beginning of the fiscal year. Average payout rates are equal-weighted across institutions within endowment size category. |

Endowment Fund Investments

In recent years, on the whole, invested endowment assets have yielded strong returns. In FY2017, endowment assets included in the NACUBO survey earned a return of 12.2% on average, resulting in income of $64 billion.35

Returns have fluctuated over time (see Figure 4). In some years, FY2016 being the most recent example, average net returns have been negative.

|

|

Source: NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments, Public NCSE Tables, Average and Median Annual Net Investment Returns, 2017 and 2010 tables, publicly accessible at https://www.nacubo.org/Research/2009/Public-NCSE-Tables. |

Returns on Endowment Fund Investments

Endowment returns vary across different types of institutions and over time. In FY2017, institutions with larger endowments tended to earn higher returns.36 This pattern tends to hold when looking at returns over longer periods of time (3-, 5-, or 10-year average rates of return). Returns of public and private nonprofit (independent) institutions are similar (when looking at equal-weighted figures).

Table 5 also provides information on the share of assets invested in alternative strategies (which includes hedge funds and private equity).37 Institutions with larger endowments tend to have a higher share of their endowment assets invested in alternative strategies. Institutions with smaller endowments tend to have most of their endowment assets invested in domestic equities, fixed income, or international equities. Trends in where endowment funds are invested over time are examined further below.

|

Endowment Size in 2017 |

1-Year |

3-Year |

5-Year |

10-Year |

Assets in Alternative Strategies (%)a |

||||||||||

|

Over $1 billion |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

$0.5 billion - $1.0 billion |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

$0.1 billion - $0.5 billion |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

$0.05 billion - $0.1 billion |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

$0.025 billion - $0.05 billion |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Under $0.025 billion |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Public |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Independent |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Full Sample (Equal Weighted) |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments, 2017.

Notes: Averages are equal-weighted, unless otherwise specified.

a. NACUBO does not report decimal places in their asset allocation tables. Data on asset allocations, or the percentage of assets invested in alternative strategies, are dollar-weighted.

b. The 29.7% full-sample estimate of assets invested in alternative strategies is the equal-weighted estimate. This increases to 52% when a dollar-weighted average is used.

Where Are Endowment Funds Invested?

|

Investment Strategy Definitions Equity Investments: The investor has an ownership interest in a company, often through the purchase of stock in the company, which can be traded on a public market. Income is generally derived from dividends (payments to shareholders out of the company's profits), or the realization of capital gains upon the sale of the stock. Fixed Income Investments: The investor lends money to a corporation (or government) borrower who pays a fixed amount of interest on a regular basis until a predetermined date. At that date the borrower also pays back the principal to the investor. Fixed income investments include U.S Treasuries, money market instruments, mortgage and asset backed securities, and bonds. Alternative Investment Strategies: These investment strategies include any investment not considered traditional. Often traditional investments include stocks (i.e., equities) and bonds (i.e., fixed income). Alternative strategies include private equity, venture capital, hedge funds, distressed (or private) debt, and "real assets" (like real estate, or oil and natural gas). |

There has been a shift in where endowment assets are invested in recent years. Between 2002 and 2010, the share of endowment assets invested in equities declined from 50% to 31%. Since 2010, the share of endowment assets invested in equities increased to 36% (see Figure 5). The percentage of assets invested in fixed income declined from 23% to 8% over the 2002 to 2017 period. While the proportion of assets being invested in equity and fixed income declined, the share of assets invested in alternative strategies increased. The share of assets invested in alternative strategies, which includes hedge funds and private equity, increased from 20% in 2002 to 51% 2009. In 2017, the share of endowment assets invested in alternative strategies was 52%.

Empirical research has explored why the asset allocation of university endowments has shifted towards alternative investments. Competition is one possible reason. There is evidence that institutions tend to increase the share of endowment holdings invested in hedge funds to "catch up" with schools that are competitors.38 Other research has observed that endowment managers are more likely to invest in alternative assets when institutions have higher and less variable background income.39 These institutions may be willing to take on the greater risk associated with alternative strategies investments.

|

Figure 5. Asset Allocations for U.S. College and University Endowments, |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of NACUBO data. Notes: Asset allocations are dollar-weighted. |

The shaded text box below provides additional background and information on UBIT and the use of blocker corporations to avoid UBIT. The increasing share of endowment assets invested or held in alternative strategies has raised concerns among some policymakers regarding the use of offshore "blocker" corporations to avoid the unrelated business income tax (UBIT) on hedge fund investments.40 This issue was the topic of a 2007 Senate Committee on Finance hearing41 and has continued to receive media attention.42

|

Investing Endowments in Hedge Funds: The Unrelated Business Income Tax (UBIT) and "Blocker" Corporations The Unrelated Business Income Tax (UBIT) The unrelated business income tax (UBIT) is effectively the corporate income tax applied to a tax-exempt organization's unrelated business income. Unrelated business income is any income from a trade or business that is regularly conducted by the organization and is not substantially related to the organization's exempt purpose.43 For example, if a university operates a gym facility that is used by students for physical education classes and is also open to members of the public who pay a fee, the fees collected from the public may be subject to UBIT.44 While investment income (e.g., dividends and interest) is generally exempt from UBIT, such income is subject to UBIT if it is derived from debt-financed property.45 Furthermore, if a tax-exempt organization invests in a pass-through entity, such as a partnership, that invests using borrowed funds, then income from that debt-financed investment will flow through to the exempt organization and be subject to UBIT.46 A different result occurs if the tax-exempt organization invests in a corporation, rather than a pass-through entity. When a corporation pays out a dividend to tax-exempt shareholders, the dividend is not subject to UBIT even if the corporation had debt-financed investments.47 Hedge Funds and UBIT Hedge funds are typically structured as partnerships and use borrowed funds for investing. Therefore, investments by tax-exempt organizations in hedge funds often give rise to UBIT as income derived from debt-financed property. Blocker Corporations to Avoid UBIT A method by which tax-exempt organizations can legally avoid paying UBIT on hedge fund investments is through the use of a blocker corporation. While there are various ways in which the blocker corporation can be set up, the basic structure is that the blocker corporation is established between the hedge fund and the tax-exempt organization so that any investment income the tax-exempt organization receives is in the form of a dividend from the blocker corporation, rather than income flowing directly from the hedge fund. Since it is a corporate dividend, there are no UBIT consequences—in other words, the use of the corporation essentially "blocks" any income subject to UBIT from flowing through the hedge fund to the tax-exempt investor. In order to avoid tax consequences for the blocker corporation, these entities are generally established in low or zero tax countries, like the Cayman Islands. The blocker corporation will then owe little or no tax to its home country, and it will typically have minimal or no U.S. tax liability since it is a foreign corporation operating outside the United States.48 |

Policy Considerations and Options

There are a number of policy options related to the tax treatment of endowments, should there be a desire to change the status quo. Policy options considered may depend on the overarching policy objective. For example, is the goal of the policy to encourage colleges and universities to use endowment funds for a specific purpose? Or is the objective of the policy to carve back or restrict the tax exemption currently provided to endowments? Or is the objective to look at endowments as a source of federal revenue? Identifying the goals of endowment-related tax policies may help inform the analysis of specific policy options. Leaving current-law tax treatment of endowments unchanged is also an option.

Modify Tax on Endowment Net Investment Income

Soon after the 1.4% excise tax on private college and university endowment's net investment income was enacted, legislation was introduced that would repeal the tax.49 Repeal of the tax is one option.

Other policy options include those that would reduce or eliminate the tax in certain situations. For example, the tax could be reduced or eliminated for institutions that devote a certain portion of endowment returns to financial aid for low- and middle-income students.50 Alternatively, the tax could be waived for institutions that meet a fixed payout objective (discussed further below) or as part of a policy requiring increased reporting related to endowments and uses of endowment funds (discussed further below). Another option would be to repeal the tax, but require that some portion of endowment assets be managed by minority- and women-owned asset management firms.51

Options to modify or redesign the tax could also be considered. For example, the tax could be expanded to apply to more institutions, or the cut-off points (either the per-student or assets per FTE thresholds) changed. The tax could also be modified to be more punitive in nature. For example, Representative Reed has suggested an approach that would require institutions with endowment assets in excess of $1 billion to use at least 25% of investment gains to reduce the cost of attendance for lower- and middle-income students.52 Institutions not meeting this target would face a tax of 30% of net investment income, with the tax increasing for institutions that do not use endowments to reduce cost of attendance as stipulated over time.

Taxing the net investment income of private college and university endowments had been proposed as part of an earlier tax reform effort. The Tax Reform Act of 2014 (H.R. 1), a tax reform proposal introduced in the 113th Congress by then Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp, proposed a flat excise tax for foundations and extended it to net investment earnings of private universities and colleges. Under this proposal, private colleges and universities with endowments in excess of $100,000 per student would be subject to a 1% excise tax.53 The tax on net investment returns of private college and university endowments enacted in the 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97) applies to institutions with endowments in excess of $500,000 per student, at a rate of 1.4%. Additionally, the tax only applies to institutions with at least 500 students.

Impose a Payout Requirement

Some policymakers have proposed requiring endowments to pay out a minimum amount every year to prevent "an unreasonable accumulation of taxpayer-subsidized funds."54 One option would be to require that endowments have a minimum 5% payout rate, similar to that required of private foundations. In the face of rising tuition, it has been suggested that to achieve their charitable and educational objectives, colleges and universities should use a greater portion of their endowments to reduce college prices and make a college education more accessible and affordable for students.55

There are a number of policy design choices that could be considered when imposing a payout requirement. While a payout requirement of 5%—the payout requirement for private nonoperating foundations—is one option, some other level (higher or lower) could be chosen. The payout requirement could be restricted to certain endowments, such as those that exceed a certain threshold, either in absolute terms ($500 million, for example) or on a per-student basis. Payout requirements could be tied to investment earnings, or capped to not exceed investment earnings in down years. Payout requirements could also be determined on a rolling basis (5% over a 3-year period, for example). Payouts requirements could also be tied to tuition levels, metrics on student need (Pell grant recipients, for example), or students' receipt of federal student aid.56

Additional nuances could complicate various policy design choices. For example, if payout requirements were to be imposed in institutions with endowments per student above some predetermined level, what measure of students would be used (e.g., would the measure of students include graduate students; would the measure of students be fall enrollment, the 12-month unduplicated headcount, full-time equivalents, or some other measure?).

Opponents of a payout requirement for endowments say the approach is misguided, and have been critical of various aspects of different payout policy options. When considering payout policies that target institutions with large endowments, some have suggested that these institutions may be more likely to offer robust financial aid and perhaps more likely to have modest tuition increases over time.57 In recent years, institutions with larger endowments have tended to have higher average payouts than institutions with smaller endowments. Thus, a payout requirement applied to all institutions regardless of endowment size could impose a greater burden on institutions with smaller endowments. Some have also questioned whether the 5% payout rate that currently applies to nonoperating foundations would be appropriate for endowments, noting that operating foundations often have lower effective payout rates.58 Finally, there are concerns that imposing a payout requirement might serve as a ceiling rather than a floor, leading institutions that would have paid out more than 5% (or whatever rate is required) to make payouts that meet the requirement but no more.59

One issue raised by university representatives is restrictions on endowments imposed by donors (i.e., donor-restricted funds, discussed earlier).60 Donor restrictions come in two forms (which often appear simultaneously): a requirement that the principal not be spent (so as to preserve the fund permanently) and a requirement that funds be spent for specified purposes. Mary Frances McCourt, representing NACUBO at a recent hearing, indicated that, in FY2014, colleges received $7.7 billion in new financial contributions to their endowments. Of those new gifts, 90% were restricted for a specific purpose by the donors.61 Since most endowments have grown over time, and proposed payout rates tend to be below earnings over time, restrictions on not spending principal could likely be designed to be manageable for most institutions.

If a payout were to be required, payouts might come from quasi-endowments, as opposed to donor-restricted funds. As noted earlier in this report (see the "What Is an Endowment?" section), in 2017, 24% of all endowment funds were reportedly held in quasi-endowments, and 25% of endowment funds in a nondefined "other" category. Thus, across endowments as a whole, it could be possible to meet a payout requirement even if a sizable portion of endowment funds is restricted. What is not clear is how a payout requirement might affect specific institutions, where the proportion of restricted endowment funds may be higher.

Restrictions on purposes are unlikely to impose a constraint to increased payouts, either for increasing spending generally or for the purpose of slowing tuition increases, because of the fungibility of money. That is, if some endowment funds are limited to specific purposes and increased spending for those purposes is not feasible (e.g., supporting an endowed chair), increased payouts from other endowments without restrictions or endowments that are devoted to student aid can be used to meet a payout requirement. Providing aid to students is one of the most common restrictions.

Nevertheless, any legislation requiring a payout or a payout tied to a particular purpose might need a "safe harbor" so that colleges and universities would not be caught between legal restrictions on donations and payout requirements. Protections from fluctuations in asset values might also be addressed by requiring minimum payout averaged over several years.

Tax Endowments or Impose Additional Taxes on Endowment Earnings

Another option would be to impose a tax on the value of endowments or impose additional taxes on endowment earnings. As is the case with the payout option, there are a number of different ways such a policy could be designed. For example, the tax could only be applied to endowments of a certain size, or to institutions with "large" endowments that have increased tuition at a certain rate (more than the rate of inflation, for example).62

Endowment earnings could also be subject to tax. One option would be to impose a tax similar to the current maximum rate of 21% already imposed on tax-exempt entities for earnings from activities not related to their exempt purpose (the unrelated business income tax, UBIT).

A tax on endowments or an additional tax on endowment earnings would generate additional federal revenues. These revenues could be earmarked to provide student aid across all colleges and universities, or could be treated as general fund revenues or used for other purposes. Whether a tax on endowments encourages universities to spend more is unclear: saving via the endowment becomes more expensive (as the after-tax return is lower) which would encourage payouts relative to endowment savings and accumulation. However, with lower after-tax returns, more saving may be needed to meet future endowment accumulation goals.

Limit or Enhance Charitable Deductions for Gifts to Endowments

Donors making contributions to endowments can claim the charitable deduction at the time the gift is made, even if the gift is not immediately used for charitable purposes. Gifts to endowments are often spent out over long periods of time. Reducing the value of the charitable deduction for gifts that are spent out over time, or are not immediately used for charitable purposes, could change incentives for giving donations that are related to endowments.

Limiting the charitable deduction for restricted gifts to endowments or term endowments would reduce the tax incentive for making this kind of contribution. Taxpayers might choose instead to make nonrestricted contributions, substituting one form of giving for another. Since limiting the deduction would reduce the tax incentive for giving to endowments, overall contributions may fall.

One option for implementing this approach could be to limit the deduction based on when the contribution is expected to be spent.63 For example, if the contribution is expected to support educational activities for 10 years, some adjustment could be made to reflect the fact that a dollar spent in the future is worth less than a dollar spent today, as a result of inflation. Since this type of adjustment could become complex, it could be limited to gifts of a certain size.

Another option would be to provide an enhanced charitable deduction for certain types of gifts. For example, taxpayers making charitable donations of funds that would be used to offset tuition for lower- and middle-income students could receive an enhanced charitable deduction for such contributions.

Change Policies for Certain Offshore Investments

As discussed above, some have noted that the increased share of endowment assets being invested in alternative strategies, particularly hedge funds, raises concerns about the use of offshore blocker corporations to avoid UBIT. The ability to use offshore blocker corporations to avoid UBIT creates disparate tax treatment between debt-financed investments made domestically and those made offshore.64 Some have also expressed concern that current law creates an incentive to borrow to increase the level of the endowment, which could force spending cutbacks in a downturn.65

In 2007, then Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee Charles Rangel introduced a bill, H.R. 3970, which addressed the disparate tax treatment of domestic and offshore investments by exempting partnership income from the UBIT.66 Following hearings by the Senate Finance Committee in 2007,67 a draft proposal by Senators Grassley and Wyden circulated in August 2008 proposed instead to disallow the use of offshore blocker corporations by providing look-through rules to determine the source of earnings.68 Others have suggested that Congress could disallow the use of blocker corporations and expand the scope of UBIT rules covering debt-financed investment to apply to all forms of leveraged investment.69 Another option would be to repeal debt-financed UBIT rules, eliminating the incentive created under current law to use offshore blocker corporations.70

Increase Data Reporting

In 2016, the Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Finance and the House Committee on Ways and Means, along with the Ways and Means Oversight Subcommittee Chairman, sent a letter to 56 colleges and universities requesting information regarding the operations and status of the institution's endowments.71 Others have suggested that the IRS Form 990 be modified to collect additional information on endowment funds.72

If endowment spending on financial aid and low- and moderate-income students is an issue of interest, it might be useful to collect additional information on spending on grants and scholarships. Another area of potential concern is administrative expenses associated with managing the endowment, including fees paid to third parties. It might also be helpful to policymakers to have additional information on the types of endowments held. For example, are endowments composed of quasi-endowments? Or is the use of assets otherwise restricted? Policymakers might also seek information on endowment holdings of real property.

Collecting additional information on college and university endowments could increase transparency, while also being useful for policymakers in both policy and oversight capacities. A potential trade-off associated with collecting additional information is increased administrative burden.

Appendix A. Endowment Data Reported to the IRS by 501(c)(3) Institutions

Data on endowments of 501(c)(3) universities and colleges are reported on Schedule D of IRS Form 990 informational returns.73 The IRS makes available data files that contain a sample of information reported on the Form 990s.74 The most recent year for which IRS microdata files are available is 2014. Public universities and colleges are not required to file 990s and thus information on nonfiling institutions' endowments is not included in the IRS data.

The IRS SOI 990 sample contains 1,048 observations of higher education entities, including colleges, universities, two-year colleges, and graduate and professional schools.75 Since the IRS SOI file is a sample, and not all smaller institutions are included, the sample weights can be used to estimate the population. Overall, this sample represents an estimated 1,782 institutions. For 2014, these institutions reported total endowments of $390.2 billion.76

In addition to collecting data on endowment balances, the IRS collects data on endowment contributions; net investment earnings, gains, and losses; grants and scholarships; other expenditures for facilities and programs; and administrative expenses. Contributions and positive net investment earnings increase endowment balances. Grants and scholarships, expenditures for facilities and programs, and administrative expenses reduce endowment balances.

In 2014, $11.3 billion was reported in contributions to 501(c)(3) higher education endowments (see Table A-1). This amount is equal to 3.0% of the endowment balances reported at the beginning of 2014. Net investment earnings on endowment funds were reported to be $20.3 billion in 2012, or 5.4% of total endowment funds.

The largest category of endowment spending in 2014 was for facilities and programs, $12.0 billion, or 3.2% of total endowment funds. Grants and scholarships were $4.2 billion in 2014, or 1.1% of endowment funds. Administrative costs were $1.0 billion, or 0.3% of endowment funds.

|

|

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

||||||||||||

|

Beginning of Year Balance |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

End of Year Balance |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Total |

As a % of Beginning of Year Balance |

Total |

As a % of Beginning of Year Balance |

Total |

As a % of Beginning of Year Balance |

Total |

As a % of Beginning of Year Balance |

|||||||||

|

Contributions |

$6.88 |

2.26% |

$9.48 |

3.14% |

$9.62 |

3.04% |

$11.28 |

3.00% |

||||||||

|

Net Investment Earnings, Gains, and Losses |

$5.11 |

1.68% |

$34.82 |

11.53% |

$49.97 |

15.78% |

$20.35 |

5.41% |

||||||||

|

Grants or Scholarshipsa |

$3.42 |

1.12% |

$3.55 |

1.18% |

$3.73 |

1.18% |

$4.16 |

1.11% |

||||||||

|

Other Expenditures for Facilities and Programsa |

$10.57 |

3.47% |

$11.09 |

3.67% |

$10.86 |

3.43% |

$12.04 |

3.20% |

||||||||

|

Administrative Expensesa |

$0.84 |

0.28% |

$0.92 |

0.30% |

$0.97 |

0.31% |

$1.04 |

0.28% |

||||||||

Source: CRS analysis of the IRS SOI public use file for tax-exempt organizations.

a. Some institutions report certain expenditures as positive, while others report these expenditures as negative. Since the three expenditure categories would reasonably be expected to be expenditures from endowments, the analysis here looks at them in absolute value terms.

Data reported by 501(c)(3) universities and colleges on their IRS Form 990 can be used to calculate payout rates. Following NACUBO, effective spending rates, or payout rates, are calculated as distribution for spending (spending on grants or scholarships and other expenditures for facilities and programs) divided by the beginning of year endowment value, net of administrative expenses. Payout rates for different endowment size classes are reported in Table A-2, in both dollar-weighted and equal-weighted terms.

Analysis of the distribution of payout rate for 501(c)(3) higher education institutions reveals a couple of trends. First, median payouts tend to be higher for institutions with larger endowments.77 Second, payout rates for larger institutions are more concentrated. The difference between the payout rate for institutions at the 25th percentile and those at the 50th percentile is greater for institutions with smaller endowments.

|

Dollar Weighted |

Equal Weighted |

||||||||||||||||

|

Endowment Size |

Number of Institutions |

Average Payout |

Average Payout |

Payout at 25th Percentile |

Median Payout (50th Percentile) |

Payout at 75th Percentile |

|||||||||||

|

Over $1 billion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

$0.5 billion - $1.0 billion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

$0.1 billion - $0.5 billion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

$0.05 billion - $0.1 billion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

$0.025 billion - $0.05 billion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Under $0.025 billion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

Source: CRS analysis of the IRS SOI public use file for tax-exempt organizations.

Notes: The 25th percentile corresponds to the point in the distribution of payouts where 25% of institutions in the endowment size class have payouts below the payout rate at the 25th percentile, and 75% of institutions have payouts above that rate. Institutions with zero endowment net of administrative costs were excluded when calculating equal weighted payouts rates.

Appendix B. Top 100 College and University Endowments

Table B-1 lists the top 100 U.S. college and university endowments reported to NACUBO as of FY2017, including both public and private institutions. Harvard University has the largest endowment, at $36.0 billion. Harvard held 6.4% of all endowment assets reported to NACUBO as of FY2017. The second-largest endowment was held by the Yale University system, at $27.2 billion, or 4.8% of all endowment assets. Taken together, the top 100 institutions listed in Table B-1 held 76.2% of endowment assets as of FY2017.

|

Institution |

Endowment ($ billions) |

Share of Endowment Assets |

Cumulative Share |

||||||

|

Harvard University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Yale University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The University of Texas System |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Stanford University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Princeton University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Pennsylvania |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The Texas A&M University System |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Michigan |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Northwestern University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Columbia University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The University of California |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Notre Dame |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Duke University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Washington University in St. Louis |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The University of Chicago |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Emory University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Cornell University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Virginia |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Rice University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Southern California |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Dartmouth College |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The Ohio State University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Vanderbilt University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

New York University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The Pennsylvania State University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Pittsburgh |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Johns Hopkins University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Minnesota & Foundation |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Brown University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Foundations |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Wisconsin Foundation |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Michigan State University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

California Institute of Technology |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Illinois & Foundation |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Washington |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The President and Trustees of Williams College |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Purdue University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Richmond |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Trustees of Boston College |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Amherst College |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Indiana University and Foundation |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Pomona College |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Carnegie Mellon University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Rochester |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The UCLA Foundation |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The Rockefeller University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Georgia Institute of Technology and related Foundations |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Trustees of Boston University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Swarthmore College |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Wellesley College |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Trustees of Grinnell College |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Virginia Commonwealth University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Case Western Reserve University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of California Berkeley Foundation |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Smith College |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Tufts University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The George Washington University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Georgetown University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Oklahoma |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Nebraska Board of Regents |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The Kansas University Endowment Association |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Florida Foundation Inc. |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Missouri System |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Washington and Lee University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Texas Christian University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Southern Methodist University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Bowdoin College |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Iowa & Foundation |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Delaware |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The University of Alabama System |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of California San Francisco Foundation |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Liberty University Inc. |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Tulane University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Kentucky |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Cincinnati |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Lehigh University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Texas Tech University System |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Syracuse University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Baylor University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Rutgers the State University of New Jersey |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Colorado Foundation |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The University of Tennessee |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Wake Forest University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Trinity University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Baylor College of Medicine |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The University of Georgia and Related Foundations |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Berea College |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Saint Louis University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The University of Utah |

|

|

|

||||||

|

NC State University and Related Foundations |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The University System of Maryland Foundation, Inc. |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Middlebury College |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Princeton Theological Seminary |

|

|

|

||||||

|

The University of Tulsa |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Vassar College |

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Arkansas - Fayetteville |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Virginia Tech Foundation |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Brandeis University |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Washington State University |

|

|

|

Source: NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowment, 2017, publicly available data at https://www.nacubo.org/Research/2009/Public-NCSE-Tables.

Appendix C. Top 25 Private Institutions Ranked by Endowment Assets per Student

Table C-1 includes the top 25 private institutions, ranked according to endowment assets per student.

Table C-1. Top 25 Private Institutions by Endowment Assets per Student

End of FY2017 Endowment assets and Fall 2016 Full-Time Equivalent Students

|

Institution |

FY2017 Endowment Assets |

Share of total Endowment Assets |

Endowment Value per Student |

Fall 2016 Full-Time Equivalent Students |

||||||

|

The Rockefeller University |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Princeton University |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Yale University |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Princeton Theological Seminary |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Stanford University |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Harvard University |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

The Principia Corporation |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Pomona College |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Amherst College |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Swarthmore College |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

The President and Trustees of Williams College |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

California Institute of Technology |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Trustees of Grinnell College |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Christian Theological Seminary |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Columbia Theological Seminary |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Rice University |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

McCormick Theological Seminary |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Wellesley College |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Bowdoin College |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Dartmouth College |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

University of Notre Dame |

|

|

|

|

Source: NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowment, 2017, publicly available data at https://www.nacubo.org/Research/2009/Public-NCSE-Tables.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

[author name scrubbed], Section Research Manager of the Education and Labor Section; [author name scrubbed], Specialist in Labor Economics; and [author name scrubbed], Legislative Attorney, provided helpful comments on an earlier version of this report. Jamie L. Hutchinson, Visual Information Specialist, provided graphics support on an earlier version of this report. Jeff Stupak was a co-author on an earlier version of this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

See, for example, Josh Lerner, Antoinette Schoar, and Jialan Wang, "Secrets of the Academy: The Drivers of University Endowment Success," Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 22, no. 3 (Summer 2008), pp. 207-222; and Jeffrey R. Brown, Stephen G. Dimmock, Jin-Koo Kang, et al., "How University Endowments Respond to Financial Market Shocks: Evidence and Implications," American Economic Review, vol. 104, no. 3 (2014), pp. 931-962. The Higher Education Opportunity Act (P.L. 110-315) required the Comptroller General to conduct a study on college and university endowments. This study was published as U.S. Government Accountability Office, Postsecondary Education: College and University Endowments Have Shown Long-Term Growth, While Size, Restrictions, and Distributions Vary, GAO-10-393, February 2010, available at: http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-10-393. |

| 2. |

Senator Grassley's opening statement and a video of the roundtable are available at http://www.finance.senate.gov/newsroom/ranking/release/?id=38a762b5-0fc7-4a9c-a130-3ddf23812279. |

| 3. |

More information on the hearing and links to hearing testimony can be found at http://waysandmeans.house.gov/event/39840295/. |

| 4. |

More information on the hearing and links to hearing testimony can be found at https://waysandmeans.house.gov/event/hearing-tax-exempt-college-university-endowments/. |

| 5. |