Child Welfare: Oversight of Psychotropic Medication for Children in Foster Care

Children in foster care are children that the state has removed from their homes and placed in another setting designed to provide round-the-clock care (e.g., foster family home, group home, child care institution). The large majority of children enter foster care because of neglect or abuse at the hands of their parents. Maltreatment by a caregiver is often traumatic for children, and may lead to children having challenges regulating their emotions and interpreting cues and communication from others, among other problem behaviors. Children in foster care are more likely to have mental health care needs than children generally.

Children in foster care who have mental health needs may receive psychosocial services such as individual or group counseling and case management to improve their health. Alternatively, or in addition, a medical professional may prescribe psychotropic medications. These are prescribed drugs that affect the brain chemicals related to mood and behavior. They are used to treat a variety of mental health conditions including attention disorders, depression, anxiety, conduct disorders, and others. While psychotropic medication alone is not necessarily advised, children in foster care may more readily receive psychotropics to treat their mental health needs due to the complexity of their symptoms and the lack of appropriate screening and assessment and/or the limited availability of health care professionals trained to provide effective therapies (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy).

Between 16% and 33% of children in out-of-home care may be using psychotropic medication on any given day, although the rate of use varies significantly based on certain factors, including the child’s age, placement setting, and length of involvement with the child welfare agency. Among children generally, about 6% are taking psychotropic medications at some point during a given year. Some of the difference in prevalence of use may be explained by the higher levels of mental health risk factors among children in foster care.

The use of psychotropics by children in foster care has come under increased scrutiny by policymakers and stakeholders in the child welfare field. Little research has been conducted to show whether psychotropics are effective and safe for children who need mental health services. Despite these concerns, some children may benefit from specific psychotropic medication for managing mental and behavioral symptoms associated with their exposure to traumatic events. President Obama’s FY2017 budget proposed a five-year initiative to reduce reliance on psychotropic medications for children in foster care by encouraging the use of evidence-based screening, assessment, and treatment of trauma and mental health disorders. Congress has also taken a strong interest in oversight of prescription medications used by children in care, addressing the issue in oversight hearings and other fact-finding forums.

Further, federal law (Title IV-B, Subpart 1 of the Social Security Act) requires states and other jurisdictions to describe their oversight of prescription medications for children in foster care, including specific protocols used with regard to psychotropic medication. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has issued guidance about these provisions and requires jurisdictions to submit annual reports to the department that describe this oversight.

Child Welfare: Oversight of Psychotropic Medication for Children in Foster Care

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Children in Foster Care

- Mental Health Needs of Children in Foster Care

- Mental Health Services and Treatments for Children in Foster Care

- Use of Psychotropic Drugs by Children in Foster Care

- Variations by State and Over Time

- Findings from the Second National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW)

- Living at Home vs. Living Out of Home

- Placement Setting

- Concurrent Use of Psychotropic Medications

- Age of Children in Foster Care

- Prescribing Patterns: "Too Many, Too Much, and Too Young"

- Weighing the Benefits of Psychotropics

- Congressional Oversight

- Executive Branch Actions

- Current Federal Provisions Related to the Oversight of Health Care for Children in Foster Care

- Federal Interagency Working Group Established

- State Interagency Cooperation and Collaboration Promoted

- Other Actions

- ACF

- SAMHSA

- CMS

- Joint Guidance

- FY2017 Request: Demonstration to Address "Over-Prescription" of Psychotropic Medication for Children in Foster Care

- State Oversight Efforts

Figures

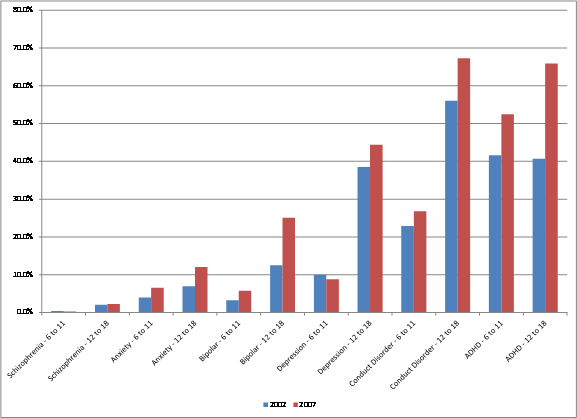

- Figure 1. Rates of Major Mental Health Diagnoses Among Medicaid-Enrolled Children in Foster Care by Age (6 to 11 years and 12 to 18 years), 2002 and 2007

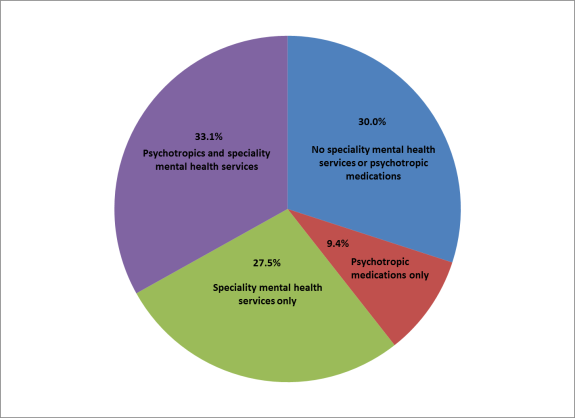

- Figure 2. Share of Children in Foster Care (Ages 16 Months to19 Years Old Who Met Clinical Criteria for a Mental Health Need) and Their Use of Psychotropics and Specialty Mental Health Services

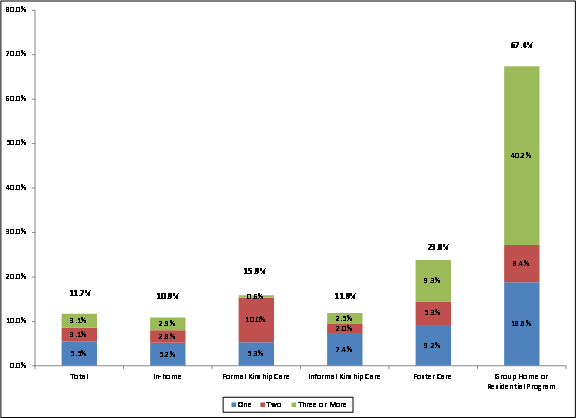

- Figure 3. Use of Psychotropic Medication by All Children Who Come Into Contact with Child Welfare Services, by Placement Type, and Number of Psychotropic Medications

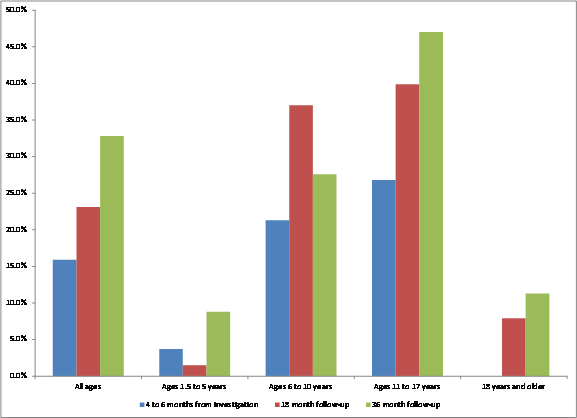

- Figure 4. Use of Psychotropic Medication by All Children Who Come Into Contact with Child Welfare Services, by Age and Time From Initial Investigation

Summary

Children in foster care are children that the state has removed from their homes and placed in another setting designed to provide round-the-clock care (e.g., foster family home, group home, child care institution). The large majority of children enter foster care because of neglect or abuse at the hands of their parents. Maltreatment by a caregiver is often traumatic for children, and may lead to children having challenges regulating their emotions and interpreting cues and communication from others, among other problem behaviors. Children in foster care are more likely to have mental health care needs than children generally.

Children in foster care who have mental health needs may receive psychosocial services such as individual or group counseling and case management to improve their health. Alternatively, or in addition, a medical professional may prescribe psychotropic medications. These are prescribed drugs that affect the brain chemicals related to mood and behavior. They are used to treat a variety of mental health conditions including attention disorders, depression, anxiety, conduct disorders, and others. While psychotropic medication alone is not necessarily advised, children in foster care may more readily receive psychotropics to treat their mental health needs due to the complexity of their symptoms and the lack of appropriate screening and assessment and/or the limited availability of health care professionals trained to provide effective therapies (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy).

Between 16% and 33% of children in out-of-home care may be using psychotropic medication on any given day, although the rate of use varies significantly based on certain factors, including the child's age, placement setting, and length of involvement with the child welfare agency. Among children generally, about 6% are taking psychotropic medications at some point during a given year. Some of the difference in prevalence of use may be explained by the higher levels of mental health risk factors among children in foster care.

The use of psychotropics by children in foster care has come under increased scrutiny by policymakers and stakeholders in the child welfare field. Little research has been conducted to show whether psychotropics are effective and safe for children who need mental health services. Despite these concerns, some children may benefit from specific psychotropic medication for managing mental and behavioral symptoms associated with their exposure to traumatic events. President Obama's FY2017 budget proposed a five-year initiative to reduce reliance on psychotropic medications for children in foster care by encouraging the use of evidence-based screening, assessment, and treatment of trauma and mental health disorders. Congress has also taken a strong interest in oversight of prescription medications used by children in care, addressing the issue in oversight hearings and other fact-finding forums.

Further, federal law (Title IV-B, Subpart 1 of the Social Security Act) requires states and other jurisdictions to describe their oversight of prescription medications for children in foster care, including specific protocols used with regard to psychotropic medication. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has issued guidance about these provisions and requires jurisdictions to submit annual reports to the department that describe this oversight.

Introduction

Children in foster care are more likely to have mental health care needs than children generally. They are also more likely than other children to receive psychotropic medications, which are prescribed drugs that affect the brain chemicals related to mood and behavior.1 Psychotropic medications are used to treat a variety of mental health conditions including attention disorders, depression, anxiety, conduct disorders, and others. On the one hand, prescription of psychotropic medication for foster children may be appropriate, given their mental health needs. Still, the evidence on the safety and efficacy of psychotropics in children is limited. Congress has taken a strong interest in how states are monitoring and regulating use of these medications. Federal child welfare law requires states to have a plan for overseeing prescription drug use among children in foster care, including the use of psychotropic medications.

This report first provides background on the mental health needs of children in foster care, and the prevalence of psychotropic medication use among these children. The next section of the report discusses congressional oversight of psychotropic medication, and efforts by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to provide assistance to states in ensuring appropriate use of psychotropic medications for children in care. Following this is a brief discussion of state monitoring of the use of these medications for foster children.

Children in Foster Care

Child welfare agencies become involved with families when investigating abuse or neglect of children by their parents or guardians. Some children may remain in their homes following the investigation, while some are removed from their homes into foster care. Children in foster care are placed in another setting that is designed to provide round-the-clock care (e.g., foster family home, group home, child care institution). Placement in foster care means that a judge has determined that the child's removal from his or her home was necessary because the home was "contrary to the welfare" of the child and, accordingly, the judge has given responsibility for the child's "care and placement" to the state child welfare agency.2 Most children enter foster care because of neglect or abuse experienced at the hands of their parents, although a child's behavior problem may also be a factor in foster care placement. This is especially true for children entering care at an older age.3 Foster care is intended to be a temporary placement until a child can be reunited with his or her parent(s), or when this is not possible, until a permanent placement with relatives, an adopted family, or a legal guardian can be found. While working to find them permanent homes, states must attend to the safety and well-being of children in foster care, including their physical and mental health.

During FY2015, some 671,000 children spent at least one day (24 hours) in foster care and 243,000 left the system, resulting in nearly 428,000 of those children remaining in care on the last day of that fiscal year. Although there is variation at the state level, the national foster care caseload has generally been in decline for more than a decade. Across the nation, there were about 77,000 fewer children in foster care on the last day of FY2015 as compared to the last day of FY2006 (when 505,000 were in care).4

Mental Health Needs of Children in Foster Care

Children in foster care have higher mental health service needs than children generally.5 The abuse or neglect children experience before entering foster care can have serious mental health outcomes. Maltreatment by a parent or other caregiver is stressful for children and may alter how their brains develop in ways that lead them to have more difficulty regulating their emotions and interpreting cues and communication from others. This negatively affects their socialization and may result in a tendency to violence or aggression towards others, among other problem behaviors.6

In a national survey conducted in 2008 and 2009, more than 4 in 10 (43%-46%) children (aged 18 months to 17 years) who were placed in a foster family home following an investigation of alleged child abuse and neglect in their families were found at risk of a behavioral or emotional problem and potentially in need of mental health services. Among children of that same age group who were placed in a foster care group home or institution, as many as 7 in 10 (61%-70%) were at such risk.7 These rates are much higher than those found in the general population. In separate surveys, about 7% to 11% of all children (in roughly the same age range) were identified as having emotional and behavioral problems.8

In recent years, children whose Medicaid eligibility is based on their "foster care" status9 have been increasingly more likely to be given mental health diagnoses.10 This is also true of children generally.11 Such diagnoses include attention disorders, anxiety, autism, bipolar disorders, conduct disorders, depression, and schizophrenia.12 Nearly all children who are in foster care are eligible for health care services funded via Medicaid, which is a means-tested entitlement program administered by the federal government in partnership with the states and authorized under Title XIX of the Social Security Act (and discussed further in the next section).13 From 2002 to 2007, the share of children whose Medicaid eligibility is based on their "foster care" status who were diagnosed with mental health disorders increased for most of these conditions. The most common diagnoses varied by age and older children were more likely to be given one of these diagnoses. In 2007, children ages 3 to 5 were most likely to have diagnoses of conduct disorder (7.4%) and attention disorders (6.7%); children ages 6 to 11 were most likely to be diagnosed with attention disorders (52.5%) and conduct disorders (26.8%); and children ages 12 to 18 years old were most likely to be diagnosed with conduct disorders (67.3%) and depression (44.4%).14

Figure 1 (below) shows, for 2002 and 2007, rates of major mental health diagnoses by age group (6 to 11 years and 12 to 18 years) among children whose Medicaid eligibility is based on their "foster care" status. The figure indicates that these rates went up across all diagnoses for both age groups, except for depression among children ages 6 to 11 and schizophrenia among both age groups.

|

Figure 1. Rates of Major Mental Health Diagnoses Among Medicaid-Enrolled |

|

|

Source: Figure prepared by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) based on data from David Rubin et al., "Interstate Variation in Trends of Psychotropic Medication Use Among Medicaid-enrolled Children in Foster Care," Child and Youth Services Review, Vol. 34, No. 8, 2012, p. 1492. Notes: "ADHD" stands for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The report does not define ADHD or other health conditions that were studied. The American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) is the standard classification of mental disorders used by mental health professionals, and defines these terms. For further information, see American Psychiatric Association, "DSM," https://psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm. Nearly all children in foster care qualify for Medicaid through a designated pathway for this population or through other pathways. The study by Rubin et al., included children as in "foster care" if, in a given year (FY2002 or FY2007), the child had at least one month of Medicaid eligibility under the "foster care child" eligibility pathway. For Medicaid reporting purposes, this includes some (but not all) children in foster care, many children who are adopted from foster care, and certain children who have aged out of foster care. For further information, see CRS Report R42378, Child Welfare: Health Care Needs of Children in Foster Care and Related Federal Issues. |

Mental Health Services and Treatments for Children in Foster Care

National standards for mental health care developed by leading child welfare and pediatric organizations propose that all children should receive a mental health screening when placed into foster care, a subsequent comprehensive mental health assessment by a mental health professional within a month of being placed into care, and a coordinated approach to delivery of services to meet the children's ongoing mental health needs.15 Such diagnostic and treatment services should currently be available to children in foster care through Medicaid. Under Medicaid, each state designs a plan for provision of medical assistance in its own state, including primary and acute medical services, as well as long-term care. The plan must be consistent with federal requirements and, if approved by HHS, entitles the state to federal reimbursement for a part of the cost of providing that medical assistance to each eligible individual in the state.

Most, if not all, children in foster care are eligible for Medicaid and are generally entitled to the same set of "traditional" Medicaid state plan services available to other children enrolled in a given state's Medicaid program.16 Central among these benefits is a provision in the law requiring that children receive all medically necessary services authorized in federal statute through the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) program.17 The EPSDT program covers health screenings and services, including assessments of each child's physical and mental health development; laboratory tests (including lead blood level assessment); appropriate immunizations; health education; and vision, dental, and hearing services. The screenings and services must be provided at regular intervals that meet "reasonable" medical or dental practice standards. Under EPSDT, states are required to provide treatment to meet children's identified health needs, including mental health needs.18 Medicaid financing may be used to provide services to meet children's behavioral health needs, including case management or services provided by psychiatrists, psychologists, or clinical social workers. It may also be used to pay for prescription drugs.19

In general, children who have mental health challenges may benefit from health care services that could include psychosocial treatment, such as counseling and case management from mental health professionals. There is a growing body of evidence on practices for responding to mental disorders in children through the use of psychosocial treatment. For example, certain psychosocial treatment interventions (i.e., behavioral and cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]; family-focused and group-based treatment; and treatments with multiple types of interventions) have been found to be moderately effective for children or parents of children with antisocial-related and disruptive behaviors.20 In addition, CBT—such as activities that include anger management, conflict resolution, and social skills training—has been found to be effective for children who experience trauma (defined as actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others).21

A medical professional may prescribe psychotropic medications to children in foster care when psychosocial treatment alone is not effective or when pharmaceutical or combination treatment has been demonstrated to be more effective than psychosocial treatment.22 Nonetheless, psychotropics may still be prescribed without accompanying psychosocial therapies because medical professionals and other stakeholders may not have resources and support readily available to address the complex mental health needs of children in care.23 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which administers the Medicaid program, has said that "an over-reliance on medication [for children in care] may reflect a lack of timely access to effective behavioral health care for Medicaid enrollees in some states, as well as fewer evidence-based psychosocial therapies for children than for adults."24 There is not a standard for what constitutes evidence-based therapies; however, HHS's Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) has rated treatments based on the evidence of their effectiveness.25

Analysis of data from a national survey of children who come into contact with child welfare agencies due to investigation of alleged child abuse or neglect found that children entering foster care were more likely to receive supports (i.e., mental health screening, a follow-up mental health assessment by a mental health professional, and referral to services) than were children with mental health needs who remained in their own homes following such an investigation.26 Similarly, research on Medicaid claims data for children in 20 states whose "foster care" status27 makes them eligible for Medicaid shows an increased use of psychosocial mental health interventions among those taking antipsychotic medication, from 58.0% to 65.5% between 2009 and 2011.28 This is compared to about 28.0% to 29.0% of non-foster children in Medicaid in both 2009 and 2011.

Other studies have shown that children in foster care who need mental health services do not always receive them.29 A national survey that collected data between 2008 and 2010 found that among children who had been in foster care for approximately 18 months or less, and who met clinical criteria for a mental health need, 3 out of 10 did not receive any specialty mental health services (e.g., counseling or residential or outpatient treatments) or psychotropics, and 9% received psychotropics without any such services.30 (See Figure 2.)

Use of Psychotropic Drugs by Children in Foster Care

Between 16% and 33% of children in out-of-home care may be using psychotropic medication on any given day, although the rate of use varies significantly based on certain factors, including the child's age, placement setting, and length of involvement with the child welfare agency.31 Rates of psychotropic medication use among children in foster care far exceed the rates among children generally, which is about 6%.32 Children whose Medicaid eligibility is based on their foster care status have been found to receive psychotropic medication at three to nine times the rate of all other children served by Medicaid,33 and at a level that is somewhat comparable to (but still higher than) older children (ages 13 to 18) with a diagnosed mental disorder or neurodevelopmental disorder.34 At the same time, research based on a national study of the use of outpatient mental health services found that children living in non-relative foster family homes were no more likely than child-welfare involved children living in their own homes to be prescribed psychotropic medication. (Importantly, this study does not include children in foster care group settings or residential treatment facilities, who tend to have higher rates of psychotropic use.35)

Variations by State and Over Time

Rates of psychotropic medication use among children involved with the child welfare system, including those in foster care, vary by state and over time. Research from the early 2000s found great variation in prescription of psychotropic medication for children involved with the child welfare system, including those in foster care. Closer analysis of the differences across states led the researchers to conclude that differences in risk for mental health services was not the primary factor leading to variation, suggesting the importance of state practices in prescribing psychotropic medication.36

A separate study of Medicaid claims data from 2002 to 2007 showed variation in psychotropic medication use among children whose eligibility for Medicaid was based on their "foster care" status.37 The study found an initial increase in the use of psychotropic medications followed by some decline in most states. However, across this same time frame the study found an increase in the use of antipsychotic medications—which are a subset of psychotropic drugs generally used to treat schizophrenia and sometimes bipolar disorder—among children whose Medicaid eligibility was based on their "foster care" status. Specifically, it found that 45 states experienced a relative increase in the use of these medications from 2002 to 2007, two states experienced a relative decrease, and one state experienced no change over the period. In 2007, the annual rate of antipsychotic medication use among children in foster care ranged from 2.8% to 21.7% in each state.38

A more recent review examined trends in 20 states of Medicaid claims data for children whose eligibility was based on their "foster care" status. The analysis showed increases in the use of antipsychotics over the period from 2005 (8.7%) to 2008 (9.3%) and then a slight decrease by 2010 (8.9%). The study further found that non-foster care children with Medicaid coverage and children with private insurance had much lower levels of antipsychotic use; however, for privately insured children the share of those using antipsychotics increased from 2005 (0.62%) to 2009 (0.77%) and remained at a steady level through 2013 (0.75%).39

Findings from the Second National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW)

This section uses data primarily from the second National Survey on Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW II) to provide a more detailed discussion of psychotropic medication use among children in foster care. NSCAW was funded and administered by HHS.

NSCAW II examined the outcomes of a national sample of 5,872 children who came into contact with the child welfare system through an investigation of child abuse or neglect in their homes, including the extent to which these children were prescribed psychotropic medications.40 The survey captured the experiences of children in this sample who remained in their homes following the investigation (including those children who stayed with their biological or adoptive parents and those who lived informally with relatives) and those who were removed from their homes and placed in foster care (including children who were placed in a non-relative foster family home, those placed formally with relatives, and those who went to live in a group home or a residential program). At the time of the initial NSCAW II Survey, 4 to 6 months after the initial investigation (in 2008-2009), these children's ages ranged from 2 months to 17.5 years. At the time of the 18-month follow-up (in 2009-2011), they were 16 months to 19 years; and at the 36-month follow-up (2011-2012), they were ages 34 months to 20 years old.41 Children in the sample were not necessarily in foster care for the entire 18- or 36-month period. They may have entered and re-entered care, or they could have entered care after a subsequent investigation.

As discussed in the following sections, the NSCAW II data show that children living with their own parents following an investigation of child abuse or neglect were less likely to be using psychotropic medication than those living in foster care at that time. Among children who were in foster care, living in a congregate care and being school age forecast a greater chance that a child in foster care was taking psychotropic medications.42

Living at Home vs. Living Out of Home

Among children in the NSCAW II study, there was not a statistically significant difference in the use of psychotropic medications among those who, at four to six months following the investigation, were placed in foster care (15.9%) and those who had remained in their homes (11.6%). However, at 18 months following the investigation, children in foster care were significantly more likely to be taking psychotropic medications than those who remained in their homes (23.1% vs. 10.9%). At the 36-month follow-up, about one out of three children in care (32.8%) was taking psychotropics, compared to 12.9% of children who remained in their homes. (For more information, see Appendix A.43)

Placement Setting

Among children placed in foster care, psychotropic medication use was significantly greater for those who lived in foster group homes or residential treatment programs than among those in foster family homes and formal kin care. Prevalence among children in group foster care settings was close to one-half (48.2%) for children who had been in care for six months or less after the initial investigation of child abuse or neglect. This is compared to 11.8% to 19.5% of children in the foster care settings.44

Figure 3 shows the rate of psychotropic medication use by whether children lived out of home, or for children in foster care, all placement settings approximately 18 months after the initial investigation of child abuse or neglect.45 As with the earlier wave (six months or less after the investigation), those in group settings were most likely to be prescribed psychotropics (67.4%), compared to less than a quarter of children in other foster care settings (15.9% to 23.8%), children who remained in their own homes (10.9%), and informal kin care (11.9%). This pattern held true 36 months after the investigation for child abuse and neglect (not shown in the figure). Just over half of children in group settings were taking psychotropics (52%). The rate of use was 16.5% to 36.1% among children in other types of foster care settings; 12.5% for children who remained in their own homes; and 16.5% for those who were in informal kin care.46

Concurrent Use of Psychotropic Medications

Figure 3 also displays the frequency with which children involved in the child welfare system were taking more than one psychotropic medication, by placement setting, approximately 18 months after the initial investigation. Compared to children in other placement settings, children in foster care group homes or residential settings were most likely to be taking more than one psychotropic medication. About half of foster children in group settings (48.6%) who were prescribed psychotropics were taking two or more drugs, whereas the rate of children in other child welfare settings taking two or more drugs was 5.7% to 14.6%.47

At 36 months following the initial investigation (not shown in the figure), about 4 of 10 children in group settings were taking two or more psychotropic medications, followed by children in foster care (18.2%), formal kin care (11.1%), informal kin care (8.8%), and those who remained in their own homes (7.2%). Children in group settings were significantly more likely to be using three or more psychotropic medications at 36 months following the investigation than children in all other settings.48

Age of Children in Foster Care

In general, children in foster care were more likely to be using psychotropic medication if they were of elementary and secondary school age. Figure 4 shows that at each wave (4 to 6 months after investigation, 18-month follow-up, and 36-month follow-up), youth ages 11 to 17 were most likely to be using psychotropics. This is followed by youth ages 6 to 10, youth ages 18 and older, and youth ages 1.5 to 5 years. Notably, the oldest youth, those ages 18 and older, were not as likely to be taking psychotropic medications as children ages 6 through 17.

Prescribing Patterns: "Too Many, Too Much, and Too Young"

The research literature has characterized patterns of prescribing psychotropic drugs to foster children as "too many, too much, and too young."49 "Too many" refers to children taking multiple psychotropic medications at a time. An analysis of national Medicaid claims data from 2002 through 2007 found that polypharmacy—defined in the analysis as concurrent use of three or more psychotropic medication classes for at least 30 days during a one-year period—was fairly consistent over that period, at about 5.2% to 5.9%, annually, among all children whose eligibility for Medicaid was based on their "foster care" status.50 An analysis of Medicaid claims data for 20 states shows polypharmacy with three or more antipsychotic drugs of at least 90 days in 2011 to have been comparable for children with "foster care" status (2.8%) and non-foster care status (3.1%).51 Data from the NSCAW II study indicate that for children in foster care who were prescribed psychotropics, the average number of psychotropics per child was 1.9 on a given day.52

As discussed previously, Figure 3 illustrates the percentage of children who were prescribed one, two, or three or more psychotropic medications. The difference between the shares of children in group or residential settings who are prescribed three or more psychotropics is statistically significant when compared to the other groups of children. Concerns have been raised about using certain classes of psychotropics, such as antipsychotics, concurrently. Antipsychotic polypharmacy (i.e., use of multiple antipsychotic medications) has not been well researched and has typically demonstrated "greater adverse effects with only marginal benefits."53

Further, "too much" refers to the prescriptions for foster children in dosages that exceed recommendations. This is of particular concern because, as discussed above, studies on the safety and efficacy of these medications for children are limited. Finally, "too young" refers to concerns that very young children are prescribed psychotropics. The NSCAW II study found that 2.2% of children under the age of 6 in out-of-home care (foster care, formal kinship care, or group home and residential programs) were prescribed psychotropics. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) examined Medicaid data from 2008 to glean insight on the use of psychotropic drugs among foster children in five states.54 They found that in each of these states 0.3% to 2.1% of children under age 1 were prescribed psychotropics, compared to a lower rate (0.1% to 1.2%) of infants of the same age who were not in foster care. Other research found that prescribing rates for ADHD medication and antipsychotic medication increased with each year of age among children ages 3 and 6 in foster care.55 Health experts have raised concerns that there are no established mental health indications for the use of psychotropic drugs in infants, and that psychotropics use by infants and young children can lead to serious health effects.56

Weighing the Benefits of Psychotropics

Because children in foster care tend to have greater mental health service needs than other children, they may be more likely to benefit from psychotropic medications. Still, as mentioned previously, psychotropic medications may not be effective in treating the mental health needs of some individuals.

Children in care may more readily receive psychotropics due to the paucity of psychosocial services available. This lack of services could be due to a number of factors, including a shortage of mental health providers generally and of those who have clinical understanding of the complex trauma many children in foster care may have experienced and/or who specialize in therapies that have proven to be effective.57 While the rate of prescribing psychotropics has decreased in recent years, the use of certain classes of these drugs—namely antipsychotics, used for the off-label treatment58 of children who have bipolar disorders and schizophrenia, and used to treat certain other behavioral conditions—has steadily grown. As discussed, the share of children in foster care prescribed antipsychotic medication increased from 2005 (8.7%) to 2008 (9.3%), with a slight decrease to 9.0% in 2010 among children in Medicaid with "foster care" status.59 This overall upward trend could be due to a number of factors, including more research (albeit limited) on the efficacy of these medications in children and the role of pharmaceutical companies marketing drugs to prescribers and consumers.60 Further, children generally have increasingly been prescribed certain psychotropic medications in recent years.61

The use of psychotropics by children in foster care has come under growing scrutiny by policymakers and stakeholders in the child welfare field. Although there is an expanding body of research on psychotropic use among children with mental health disorders, few studies show that they are safe and effective for this population. A review by HHS of research on one class of psychotropics, antipsychotics, found that most studies had insufficient evidence to draw a conclusion about the safety of these drugs in addressing child mental health disorders generally—not just those occurring among foster youth. Further, little to no evidence was available for certain conditions such as disruptive behavior disorders, obsessive compulsive disorders, or eating disorders (i.e., anorexia nervosa). According to the analysis, the median study duration of eight weeks was insufficient to evaluate some long-term outcomes. The analysis also found that most of the studies had a high risk of bias because missing data were not handled and reported properly, study participants were not randomly assigned to the treatment groups, and/or the studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies that manufacture the psychotropic medication.62 Other research has shown that antipsychotics are associated with harmful health outcomes in some children, including high cholesterol levels, weight gain, and type-2 diabetes.63

Despite these concerns, some children in foster care may benefit from psychotropic medication for managing symptoms and issues associated with mental health and behavior concerns stemming from their exposure to complex trauma, particularly if this treatment is coupled with psychosocial services.64 Stimulants for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a common childhood disorder, appear to be among the best researched of the antipsychotic classes. Multiple studies with research methodologies that used randomized control trials have found that some stimulants are very effective at reducing the core symptoms of ADHD, including hyperactivity, impulsivity, inattention, and aggression.65

Further, children in foster care are more likely to have a mental health diagnosis than children generally, including children who are low income. A 2011 GAO report on psychotropic medication use by children in foster care cited statements from state officials and child psychiatrists that higher levels of psychotropic drug use may be appropriate to deal with the increased prevalence and greater severity of mental health conditions among this population. In addition, multiple foster care placements and inconsistent state oversight practices for managing their care may contribute to the likelihood that psychotropics are used to respond to the mental health needs of these children.66

Congressional Oversight

Congress has taken an interest in oversight of prescription medications used by children in foster care. In 2005, the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Human Resources held a hearing to examine the enrollment of children in foster care in clinical drug trials. The hearing followed media reports concerning use of foster children in clinical AIDS drug trials and addressed the extent to which states properly oversee prescription drug use by children in foster care.67 As part of the Child and Family Services Improvement Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-288), Congress required state child welfare agencies, as a condition of receiving certain child welfare funding, to describe how they actively consulted with physicians or other medical professionals in assessing the health and well-being of children in foster care and in determining appropriate medical treatment for them.68

The issue of oversight of psychotropic medication use for children in foster care in particular was briefly discussed at a 2007 congressional hearing on health care oversight for children in foster care, and it was the sole topic of a 2008 hearing. Both hearings were held by the Ways and Means Subcommittee on Income Security and Family Support.69 Subsequently, as part of the Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-351), Congress expanded on the requirement that states consult with medical professionals on the health and well-being of children in foster care. Specifically, states are required through their child welfare and Medicaid agencies, and in consultation with appropriate medical professionals, to develop a coordinated strategy and oversight plan to ensure access to health care, including mental health services for each child in foster care. The 2008 law directed states to ensure this coordinated strategy provided for oversight of drugs prescribed to children in foster care. In October 2011, the Child and Family Services Improvement and Innovation Act (P.L. 112-34) amended this provision to further stipulate that the coordinated strategy must include protocols for use of psychotropic medication for children in foster care.

In December 2011, the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Subcommittee on Federal Financial Management, Government Information, Federal Services and International Security held an oversight hearing that focused on the results and recommendations of the aforementioned study by the Government Accountability Office.70 GAO reviewed state policies and regulations for oversight of prescribing psychotropic medications in six states.71 The study compared state policies against best practice guidelines for prescribing psychotropics for foster children and other vulnerable child populations. These best practice guidelines were developed by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) with support and funding from HHS's SAMHSA.72 Overall, GAO found that each of the six state programs fell short of providing comprehensive oversight as defined by AACAP. For example, though all six states implemented some practices consistent with the guidelines for consent procedures, only one state (Texas) fully implemented these procedures. According to the report, states that do not incorporate consent procedures similar to AACAP's guidelines may increase the likelihood that caregivers are not fully aware of the risks and benefits associated with the decision to use psychotropic medications. GAO made recommendations that HHS consider endorsing guidance to state Medicaid and child welfare agencies on best practices for monitoring psychotropic medications for children in foster care. According to GAO, this recommendation was implemented (see next section on executive branch actions).73

Witnesses at the hearing spoke about the role of HHS and the state Medicaid programs in increasing cooperation and communication between the agencies and discussed how HHS could increase the guidance on best practices to assist states in preparing plans for psychotropic medication oversight. Further, a 12-year-old former foster youth described being given multiple mental health diagnoses and side effects he experienced from multiple psychotropic medications that were prescribed to him while in foster care. He also testified that a therapist that he saw with his adoptive parents was most helpful to him.

Additionally, in April 2013 the Senate Finance Committee convened a roundtable discussion with Senate staff and child welfare stakeholders to address issues associated with the prescription of psychotropic medications for children in foster care and to highlight alternative strategies to effectively respond to trauma experienced by children and youth in foster care. At the roundtable, current and former foster youth shared their experiences with psychotropic medication and some noted that therapy ultimately helped them transition from psychotropic medications. The youths' stories sometimes highlighted the importance of an invested caregiver or other knowledgeable professional in ensuring that appropriate mental health treatment is identified and provided. Child welfare stakeholders discussed the prevalence of psychotropic medication use among subpopulations of youth; the role of the federal government in promoting alternatives to psychotropics; tools for determining whether youth should be prescribed medications; and the roles of schools, the mental health system, and foster parents in engaging with youth on whether psychotropic medications should be prescribed.

In May 2014 the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Human Resources held a hearing on the use of psychotropic medications among children in foster care and the efforts of states and the federal government to ensure that such medications are used appropriately. Witnesses included the Associate Commissioner of HHS's Children's Bureau; GAO; a researcher who focuses on psychotropic medication use among children in care; and Dr. Phil McGraw, who has sought to bring greater awareness to the issue.74

At the May 2014 hearing, staff from GAO focused remarks on the agency's work from 2011 to 2014 related to psychotropic medication prescription among children in care. Following their December 2011 Senate hearing testimony and report, GAO examined prescribing rates among children in foster care in five states, including the extent to which documentation supported the use of psychotropics among a sample of 24 children in care. GAO contracted with two child psychiatrists who conduct mental health research and work on issues related to foster care to examine the sample of cases. These experts found varying quality in the documentation supporting the use of psychotropics. For example, experts found that in most cases medical pediatric exams were mostly supported by documentation; however, they found that documentation was partially supported for about half to slightly more than half of the cases examined with regard to the dosage amount of medications and concurrent use of multiple medications.75 GAO recommended that HHS issue guidance to states regarding oversight of medication to third-party managed care organizations (MCOs), which increasingly are administering Medicaid benefits (including prescription benefits) for children in foster care. As noted in the subsequent section, HHS has since issued guidance to state child welfare and Medicaid agencies on oversight of psychotropic medication use among children in care. According to GAO, this guidance has not addressed the role of third-party MCOs in oversight of psychotropic use among foster children.76

GAO subsequently issued a report in January 2017 that examined how child welfare agencies and Medicaid agencies in seven states monitor psychotropic use among children in care and the results of these state efforts.77 State officials reported to GAO that they developed a variety of practices to better support the appropriate mental health diagnoses and treatment for children in foster care, including initial mental health screenings and monitoring children after they are prescribed medications. For example, all seven states developed guidelines on prescribing psychotropic medications and on promoting the use of psychosocial services (e.g., requiring or recommending psychosocial services prior to or concurrently with psychotropic medication). Officials in all seven states reported that several factors—strong collaboration among child welfare, Medicaid, or other partnering agencies; state outreach to stakeholders such as physicians about the requirements; and gradual rollout of new practices—were critical in implementing their oversight work.

GAO did not examine the effectiveness of state practices, state compliance with state or federal policies, or whether there are controls in place to ensure that required practices are followed. State officials reported to GAO that they use a variety of measures to gauge the results of their efforts, including physician prescribing practices (e.g., type and amount prescribed); state oversight practices (e.g., reviewing case and health records); and monitoring child outcomes (e.g., placement disruptions for children on psychotropic medications).

GAO also looked into the ways that HHS has supported states in their oversight work since 2014, noting that HHS has not convened meetings with stakeholders engaged in state oversight of psychotropic medication use for children in care. (Some of these efforts are described in the next section.) GAO recommended that HHS consider cost-effective ways to convene state stakeholders to share information and collaborate on psychotropic medication oversight.

Executive Branch Actions

HHS has implemented the federal requirements that states have protocols in place for monitoring psychotropic medication use. In addition, several federal agencies have worked both together and independently to help gain a better understanding of psychotropic medication use among children (especially children in foster care). As part of their efforts to promote interagency cooperation, they have publicized best practices and successful state strategies related to the oversight of psychotropic medication use for children and the development of alternative strategies for children with mental health needs. For multiple years, the Obama Administration proposed expanding funding for oversight of psychotropic medications as part of its annual budgets, including for FY2017 (as of the date of this report, a final FY2017 appropriations law has not been enacted).

Current Federal Provisions Related to the Oversight of Health Care for Children in Foster Care

As noted previously, under the Stephanie Tubbs Jones Child Welfare Services Program (Title IV-B, Subpart 1 of the Social Security Act) states must develop a coordinated strategy and oversight plan to ensure access to health care, including mental health services and dental care, for all children in foster care. This coordinated strategy and oversight plan must be developed via a collaborative effort between the state child welfare agency and the state agency that administers Medicaid, in consultation with pediatric and other health care experts, as well as experts in, or recipients of, child welfare services.78 The coordinated strategy must outline

- a schedule for initial and follow-up health screenings that meet reasonable standards of medical practice;

- how health needs identified through screenings, including emotional trauma associated with a child's maltreatment and removal from home, will be monitored and treated;

- how medical information for children in care will be updated and appropriately shared, which may include the development and implementation of an electronic health record;79

- steps to ensure continuity of health care services, which may include the establishment of a medical home for every child in care;80

- the oversight of prescription medicines, including protocols for the appropriate use and monitoring of psychotropic medications (italics added for emphasis);

- how the state actively consults with and involves physicians or other appropriate medical or nonmedical professionals in assessing the health and well-being of children in foster care and in determining appropriate medical treatment for the children; and

- steps to ensure that the components of the transition plan development process related to the health care needs of children aging out of foster care are met.

Additionally, federal child welfare law requires that the state child welfare agency have a written plan for each child in foster care, including certain health-related records. These records must include the names and addresses of the child's health providers, a record of the child's immunizations, information about the child's medication, and any other relevant health information concerning the child.81 These records must be reviewed, updated, and supplied to a child's foster care parent or provider at the time of each foster care placement. Additionally, a copy of the record must be provided to a youth at the time he/she leaves care due to age.82

States and other jurisdictions report to HHS on their policies about oversight of psychotropic medications through the five-year Child and Family Services Plan (CFSP) and annual updates to the plan known as Annual Progress and Services Reports, or APSRs. The reports are required each year for jurisdictions seeking federal funds under a number of child welfare programs, including the Stephanie Tubbs Jones Child Welfare Services Program.83 Jurisdictions were first required to submit information about psychotropic oversight for the FY2013 APSR, following the 2011 enactment of the law (the Child and Family Services Improvement and Innovation Act, P.L. 112-34) on these requirements.84 As shown in the text box, the APSR instructions directed that state oversight protocols must address screening and evaluation to identify mental health needs; consent and assent to treatment and ongoing communication; medication monitoring; availability of mental health expertise; and mechanisms for sharing current information and education materials. Subsequent program instructions have not been as detailed. The most recent five-year CFSP is for FY2015-FY2019. Jurisdictions were asked to report in the CFSP on "the oversight of prescription medicines, including protocols for the appropriate use and monitoring of psychotropic medications."85

|

Program Instructions for the Annual Progress and Services Report for FY2013 States must submit information to HHS on their plans to provide child and family services by June 30 of each year. The report to be submitted for June 2012 (describing plans for FY2013) was the first in which states were required to provide their protocols for oversight of psychotropic medication use among children in foster care. According to HHS, these protocols were developed from guidelines put forth by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the Reach Institute, among others. They include the following:

Source: Title IV-B Child and Family Services Plan; Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment State Plan; Chafee Foster Care Independence Program; Educational Training Vouchers Program, ACYF-CB-PI-12-05, April 11, 2012. |

Federal Interagency Working Group Established

In the summer of 2011, HHS convened an interagency working group to address emerging research on the use of psychotropic medication among children in foster care and to support state efforts in implementing the requirements on psychotropics in P.L. 112-34. The working group developed a plan to expand the use of evidence-based screening, diagnosis, and interventions; strengthen the oversight and monitoring of psychotropic medications; and expand the research evidence regarding medications and psychosocial treatments for children in foster care.86

The working group is led by the Administration for Children and Families (ACF), which administers child welfare programs, and includes representatives from other HHS agencies, including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). CMS administers Medicaid, which offers states a way to finance screenings, assessments, behavioral health services, therapy, case management for children with complex trauma needs (many of these services are mandatory for eligible children); and prescription drugs. SAMHSA administers block grant funding that may support non-Medicaid covered treatment services, and it supports other technical assistance and projects related to understanding trauma experienced by children and providing evidence-based and effective treatment.

State Interagency Cooperation and Collaboration Promoted

In November 2011, three agencies in the working group—ACF, SAMHSA, and CMS—released a letter addressed to the directors of each state child welfare, Medicaid, and mental health agency. The letter addressed actions being taken at the three federal agencies to "support effective management" of prescription medication use for children in foster care.87 According to the letter, "State Medicaid/CHIP agencies and mental health authorities play a significant role in providing continuous access to and receipt of quality mental health services for children in out-of-home care. Therefore it is essential that State child welfare, Medicaid, and mental health authorities collaborate in any efforts to improve health, including medication use and prescription monitoring structures in particular." The letter further discussed other steps the agencies would take to raise awareness about psychotropic use among children in foster care.

ACF, SAMHSA, and CMS (in partnership with their training and technical assistance providers) subsequently took steps to provide guidance to states and other stakeholders on oversight of psychotropics through a series of webinars and information memoranda. In January and February 2012, they held webinars for child welfare and other stakeholders that presented data, research, and practices for monitoring and oversight of psychotropic medication use among children in foster care.88 In addition, the three agencies held a series of question and answer discussion sessions in March through June 2012 for state child welfare and mental health leaders who are working together on plans to enhance oversight and monitoring.89

In August 2012, HHS (ACF, SAMHSA, and CMS) convened state directors of child welfare, Medicaid, and mental health agencies to address the use of psychotropic medications for children in foster care and the mental health needs of children who have experienced trauma. The summit, "Because Minds Matter," was intended to provide an opportunity for state leaders to enhance their collaboration on the appropriate use of psychotropic medications.90 They were asked to examine what aspects of oversight needed improvement and the steps needed to implement changes. States were also asked to outline the activities they would undertake to meet their goals, the anticipated challenges, the necessary partners, and a timeline for implementation.91 The summit included multiple presentations from HHS staff, researchers, and selected state teams about a range of psychotropic oversight and related topics.92

Other Actions

Since the "Because Minds Matter" summit, HHS has furthered its work on oversight of psychotropic medications. This section discusses selected steps taken by ACF, SAMHSA, and CMS.

ACF

In April 2012, ACF provided guidance to state child welfare agencies on implementing protocols to monitor the use of psychotropic medication. As part of this guidance, HHS synthesized information about use of psychotropics based on guidelines issued by child welfare and medical professionals.93 These elements address coordinated planning, informed and shared decision-making, medication monitoring, mental health expertise and consultation, and mechanisms for sharing accurate and up-to-date information.94 (As discussed in a subsequent section, HHS requires that states report on the extent to which these elements are in place as part of their monitoring of psychotropic drug use for children in foster care.) ACF also issued separate guidance in April 2012 to state child welfare agencies about the ways they can focus on improving the behavioral and social-emotional outcomes for children who have experienced abuse and/or neglect. The guidance discussed the emerging evidence on the impact of maltreatment in terms of its effect on brain development as it affects a child's social and emotional development.95 ACF has also published two guides, one on tools to help youth in foster care ask questions about medications as they meet with physicians and another for child welfare staff and foster parents on mental health issues, the impact of trauma, and psychotropic medications.96

Separately, ACF awarded FY2012 funds to nine entities (state and county child welfare agencies, universities, and a children's hospital) to support projects intended to provide assistance to youth in child welfare who have mental and behavioral health needs using evidence-based intervention models.97 ACF also awarded FY2013 funds to six entities (state child welfare agencies, universities, and a children's organization) to promote well-being after children experience trauma.98

SAMHSA

As noted, SAMHSA provided partial funding to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in developing guidelines on prescribing medications.99 The recommendations are focused on clinical practice, psychotropic medication monitoring and oversight, and research. The guidelines pertain to children and youth generally. SAMHSA also funds a medical director position through a contract with the Technical Assistance Network at the University of Maryland's School of Social Work. The medical director works with 55 child and adolescent psychiatrists in state and county governments to address issues regarding psychotropic medications. The network uses a community listerv to disseminate best practices to the psychiatrists and has developed webinars on medication oversight, including for children on Medicaid.100

CMS

The CMS Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services issued an informational bulletin in August 2012 to make states aware of resources and opportunities to address the use of psychotropic medication in vulnerable populations, including children in foster care. The informational bulletin noted that all states are required to have Drug Utilization Review programs in place to oversee the prescribing of drugs for Medicaid beneficiaries and provided examples of the way some states have used this review to provide oversight of psychotropic medication use.101 For example, automated system "edit checks" may be used to ensure prescriptions are consistent with accepted medical practice (e.g., special authorization must be granted for prescriptions of children younger than a given age). The bulletin alternatively noted that some states have multidisciplinary teams (drawing from public and private entities) to review cases and ensure appropriate prescription of psychotropics.102

In 2015, CMS helped a working group of eight state Medicaid agencies and their partners to improve appropriate use of antipsychotic medications for children who receive Medicaid. CMS also added a measure to core measures that can voluntarily be used by states to help them in improving health care delivery to children receiving Medicaid (the new measure also applies to the State Children's Health Insurance Program, a program for children and pregnant women in families that have annual income above Medicaid eligibility but have no health insurance).103

Joint Guidance

CMS, ACF, and SAMHSA issued joint guidance in July 2013 to convey the importance of making psychosocial interventions available to children who have experienced "complex trauma"—described in the guidance as "children's exposure to multiple or prolonged traumatic events, which are often invasive and interpersonal in nature"—and to highlight how states may use existing federal funding and authority to provide those interventions. The guidance noted that children in foster care may be more likely to receive psychotropic medication, and may not be prescribed psychotropics properly, because of the complexity of their symptoms and the lack of appropriate screening, assessment, and treatment. The guidance promoted the use of functional assessments (periodic evaluation of a child's well-being using standardized, valid, and reliable measurement tools), trauma screening (brief evaluation of potential trauma symptoms and/or history), mental health assessment (in-depth clinical evaluation of an individual's mental health status), and outcome measurement and progress monitoring (measuring success by tracking child-level well-being outcomes to ensure treatment services are achieving desired improvements in children's health and functioning).104

FY2017 Request: Demonstration to Address "Over-Prescription" of Psychotropic Medication for Children in Foster Care105

President Obama's FY2017 budget proposed a five-year joint initiative between CMS and ACF to reduce reliance on psychotropic medications for children in foster care and improve their well-being. This would be accomplished by providing performance-based incentive payments to state Medicaid agencies (total of $500 million in incentive funding across five years, FY2017-FY2021) that meet certain outcomes or other requirements related to improved care coordination and delivery of evidence-based psychosocial interventions to Medicaid-eligible children who are also served by child welfare agencies. Incentive payments would be paid annually out of the Medicaid program (Title XIX of the Social Security Act) over the five-year period.106

States could also apply, through the state child welfare agency, for competitive grant funding under the Title IV-E Foster Care program (total of $250 million across five years, FY2017-FY2021) to build state capacity and infrastructure to implement alternative psychosocial interventions. ACF would support activities that include child welfare funding for building the capacity to provide evidence-based psychosocial intervention for children in care and ensuring fidelity to these models, while also evaluating this work.107

State Oversight Efforts

The research literature has focused on the role of states in overseeing the use of psychotropic medication for children in foster care. For example, some research has addressed the issue of obtaining consent for using psychotropics or examining how certain states are carrying out their monitoring procedures.108 Researchers have also conducted surveys of states to learn about their policies related to the oversight of psychotropic medications. Some of these surveys predate the specific requirement for oversight of prescription medications and others have been conducted since then; however, none of these surveys address how states have responded to the federal provision (added to the law in September 2011) on oversight of psychotropic medications specifically.

In 2009 and 2010, researchers surveyed states to learn about the status of policies and guidelines for overseeing the use of psychotropic medication by children in foster care, as well as related challenges and solutions that were identified by states. Researchers collected information from 48 states, including the District of Columbia. Of the states surveyed, more than half (58.7%) rated psychotropic medication use to be of high concern (a rating of 8 to 10 on a scale of 1 to 10). About a quarter of the states rated the issue of moderate concern (a rating of 5 to 7), and about 13% rated it of low concern (a rating of 1 to 4).

At the time of the survey, 26 of the 48 states had a written policy or guideline regarding psychotropic medication use; 13 states were currently developing a policy or guideline; and 9 states had no policy or guideline. Slightly more than half of states used at least a "red flag" marker to identify problems with the safety and quality of psychotropic drug use. Red flags that states described using included the use of psychotropic medications in young children, the use of multiple medications before the use of a single medication, use of multiple psychotropic medications simultaneously, use of multiple medications within the same class for longer than 30 days, and dosage exceeding current maximum recommendations. Researchers concluded that states were implementing a wide variety of approaches, and that there was little evidence that these approaches were being implemented or studied in a systematic way to identify which approaches helped improve outcomes for children in foster care.109

Researchers have more recently raised concerns about the availability of policies and procedures that respond to psychotropic medication use. As reported in a 2014 study, researchers reviewed the statutes, rules, and statements of policies on oversight of psychotropic drug use among children in care from 16 states (which have 72% of all children in care nationally). They were unable to locate many of the policies that had been reported in other studies, and when they did exist, the policies were "extremely underdeveloped and failed to include many of the 'red flag' criteria that both experts and states identified as essential to protecting children, such as the use of psychotropic medication for young children, dosage level, and whether multiple psychotropic medications were prescribed simultaneously."110

Still, states have taken steps to more systematically address oversight of psychotropic medication use among children in foster care. As noted, state representatives from child welfare, Medicaid, and mental health agencies convened working groups as part of an HHS summit. Further, some states are working collaboratively to improve oversight. For example, the Center for Health Care Strategies, a policy organization, worked with six states from 2012 to 2015 as part of the Psychotropic Medication Quality Improvement Collaborative. This collaborative included representatives of state child welfare, mental health, and Medicaid agencies. They worked together to define common terms and common measures on data about the utilization of psychotropic medication among foster youth, including sub-groups of foster youth. They also developed best practices in psychotropic medication oversight and monitoring, with each state establishing a set of individual goals. The states have implemented protocols in four areas: gaining consent, obtaining real-time data on psychotropic utilization, developing a protocol for reviewing "red flags," and developing monitoring processes that are tailored to the needs of localities. With support from SAMSHA, the Center for Health Care Strategies is providing technical assistance to states generally on oversight of psychotropic medications.111

Appendix A. Use of Psychotropics Among Children in Families Investigated for Abuse or Neglect

The National Survey of Child and Adolescent Wellbeing (NSCAW) II looked at rates of psychotropic medication use among a sample of children (5,873) who came into contact with the child welfare agency because of an investigation of child abuse or neglect in their families. Initial (baseline) survey data were collected in 2008-2009 approximately four to six months after that investigation. With regard to use of psychotropic medication, data cover children who at the time of the initial survey were at least 18 months of age and up to 17 years old. A follow-up survey looked at psychotropic medication use among these same children at approximately 18 months after the investigation of abuse or neglect, and a third survey looked at those children at 36 months following the investigation. (Some of the children followed had reached age 18 or older by the second or third collection of data.)

Table A-1 shows psychotropic medication use by age, and whether or not the child was in a foster care setting for the initial survey and for the follow-up at 18 months and 36 months. For purposes of this analysis, a foster care setting includes children who were placed in a non-relative foster family home, children placed with kin on a formal basis, and children placed in a group or residential setting. By contrast, children included in the "in home" category includes children living with their biological or adoptive parents, as well as children who were in informal kinship care settings.

Statistical Significance

The percentage differences shown by the initial survey in use of psychotropic medication (between children in foster care and those who were not in foster care) were not statistically significant overall or for any specific age group shown in Table A-1. However, the differences shown for these groups at the 18-month and 36-month follow-up were statistically significant, with children in foster care more likely to be using psychotropic medications.

For children under age 6, there was no statistical significance found in the percentage differences shown for children in foster care versus those living at home in any of the surveys (initial, 18-month or 36-month). For children ages 6 to 10, the percentage difference shown between the in-home and foster care groups at the 18-month follow-up was found to be statistically significant but not those shown at the initial survey or at the 36-month follow-up. For children ages 11 through 17 years, there was not statistical significance found between the in-home and foster care groups at the initial survey but the differences shown at the 18-month and 36-month follow-up were significant.

Table A-1. Use of Psychotropic Medication Among Children in Families Investigated for Child Abuse or Neglect

Percentages based on caregiver report at time of interview or youth self-report for those 18 or older

|

Age at Time of Survey and Placement Status of Children |

4 to 6 Months Following Investigation |

18- Month Follow-Up |

36- Month Follow-Up |

|

TOTAL (18 months or older) |

|||

|

Foster Care |

15.9% |

23.1%a |

32.8%a |

|

In-home |

11.6% |

11.0% |

12.9% |

|

Ages 18 months to 5 yearsb |

|||

|

Foster Care |

3.7% |

1.5% |

8.8% |

|

In-home |

1.4% |

1.6% |

1.6% |

|

Ages 6-10 years |

|||

|

Foster Care |

21.3% |

37.0%a |

27.6% |

|

In-home |

19.5% |

19.2% |

16.1% |

|

Ages 11-17 years |

|||

|

Foster Care |

26.8% |

39.9%a |

47.0%a |

|

In-home |

15.7% |

13.8% |

16.5% |

|

Age 18 or older |

|||

|

Include all youth age 18 or older regardless of where they lived. |

NA |

7.9% |

11.3% |

Source: Congressional Research Service, based on data from NSCAW II as received from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning Research and Evaluation (OPRE), January 2014.

Note: Interviews were conducted with caregivers and youth (where applicable) at three periods after the investigation of child abuse or neglect that brought the child to the attention of the child welfare agency. These investigations occurred between February 2008 and April 2009. Children in the sample were not necessarily in foster care for each period. They may have entered and re-entered care during this time, or they could have entered care after a subsequent investigation. Children in foster care include those who were living in a non-relative foster family home, formal kinship care, or a group home/residential program. Those shown as living "in-home" were those who remained with their biological or adoptive parents or those who were living informally in kinship care.

a. Indicates that children in this group of foster care children were significantly more likely to be taking psychotropic medication than the comparable group of children who were living in their own homes during the same point in time.

b. The overall NSCAW sample included children as young as two months at the beginning of the study. The data on psychotropic use includes children in the sample who were 18 months and older. Some children in the sample were not yet 18 months old at the initial survey, and later aged into the sample at the 18-month follow-up. This led to an increase in the overall number of children in the sample at 18 months and 36 months.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Psychotropic drug classes include those for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), antianxiety, antidepressants, antipsychotics, hypnotics, and mood stabilizers. For further information, see Table 1 of U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Foster Children: HHS Guidance Could Help States Improve Oversight of Psychotropic Prescriptions, GAO-12-201, December 2011, http://gao.gov/products/GAO-12-201. (Hereinafter, GAO, Foster Children: HHS Guidance Could Help States Improve Oversight of Psychotropic Prescriptions.) |

| 2. |

A small percentage of children nationwide enter foster care via "voluntary placement agreements." In these situations a parent or guardian signs over certain care and placement responsibility to the state child welfare agency and, after six months, a judge may be asked to determine if this placement continues to be in the "best interest" of the child. |

| 3. |

"Neglect" was associated with removal and entry to foster care of more than two-thirds (67%) of children entering care at age 12 or younger and 38% of those entering at ages 13 through 17. By contrast, a "child's behavior problem" was associated with removal of about 2% of children entering care at age 12 or younger and close to 43% of those children entering care at age 13 through 17 years of age. Based on state data reported via the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis Reporting System (AFCARS) for FY2014 and provided to CRS by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Administration for Children and Families (ACF), Administration for Children, Youth and Families (ACYF), Children's Bureau. Each child could have one or more reasons associated with his or her removal from the home and entry to foster care. |

| 4. |

HHS, ACF, ACYF, Children's Bureau, Trends in Foster Care and Adoption: FY 2006-FY 2015, based on AFCARS data reported by states as of June 8, 2016. |

| 5. |

John Landsverk, Barbara Burns, Leyla Stambaugh, and Jennifer A. Rolls Reutz, Mental Health Care for Children and Adolescents in Foster Care: Review of Research Literature, prepared for Casey Family Programs, February 2006. |

| 6. |