The American Opportunity Tax Credit: Overview, Analysis, and Policy Options

The American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC)—originally enacted on a temporary basis by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA; P.L. 111-5) and made permanent by the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act (PATH; Division Q of P.L. 114-113)—is a partially refundable tax credit that provides financial assistance to taxpayers (or their children) who are pursuing a higher education. The credit, worth up to $2,500 per student, can be claimed for a student’s qualifying expenses incurred during the first four years of post-secondary education. In addition, 40% of the credit (up to $1,000) can be received as a refund by taxpayers with little or no tax liability. The credit phases out for taxpayers with income between $80,000 and $90,000 ($160,000 and $180,000 for married couples filing jointly) and thus is unavailable to taxpayers with income above $90,000 ($180,000 for married couples filing jointly). There are a variety of other eligibility requirements associated with the AOTC, including the type of degree the student is pursuing, the number of courses the student is taking, and the type of expenses which qualify.

Before enactment of the AOTC, there were two permanent education tax credits, the Hope Credit and the Lifetime Learning Credit. The AOTC replaced the Hope Credit (the Lifetime Learning Credit remains unchanged). A comparison of these two credits indicates that the AOTC is both larger—on a per capita and aggregate basis—and more widely available in comparison to the Hope Credit. Data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) indicate that enactment of the AOTC contributed to an increase in both the aggregate value of education credits claimed by taxpayers and the number of taxpayers claiming these credits.

Education tax credits were intended to provide federal financial assistance to students from middle-income families, who may not benefit from other forms of traditional student aid, like Pell Grants. The enactment of the AOTC reflected a desire to continue to provide substantial financial assistance to students from middle-income families, while also expanding the credit to certain lower- and upper-income students. A distributional analysis of the AOTC highlights that this benefit is targeted to the middle class, with approximately half (46.6%) of the estimated $17 billion of AOTCs in 2015 going to taxpayers with income between $30,000 and $100,000.

One of the primary goals of education tax credits, including the AOTC, is to increase attendance at higher education institutions (for brevity, referred to as “college attendance”). Studies analyzing the impact education tax incentives have had on college attendance are mixed. Recent research that has focused broadly on education tax incentives that lower tuition costs and have been in effect for several years, including the Hope and Lifetime Learning Credits, found that while these credits did increase attendance by approximately 7%, 93% of credit recipients would have attended college in their absence. Even though the AOTC differs from the Hope Credit in key ways, there are a variety of factors that suggest this provision may also have a limited impact on increasing college attendance. In addition, a recent report from the Treasury Department’s Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) identified several compliance issues with the AOTC.

There are a variety of policy options Congress may consider regarding the AOTC. (The credit was not modified or changed in the recent tax law enacted at the end of 2017, P.L. 115-97.) Alternatively, Congress may want to examine alternative ways to reduce the cost of higher education. This report discusses these issues and concludes with an overview of selected proposals to modify the AOTC.

The American Opportunity Tax Credit: Overview, Analysis, and Policy Options

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Did P.L. 115-97 Modify the AOTC?

- Current Law

- Calculating the Credit

- Eligibility Requirements

- Qualifying Student

- Qualifying Education Expenses

- Identification Requirements of the Taxpayer, Student, and Educational Institution

- Disallowance of the Credit Due to Fraud or Reckless Disregard of the Rules

- Legislative History

- Analysis

- Who Benefits from the AOTC?

- Does the AOTC Increase Attendance at Post-Secondary Educational Institutions?

- Are Ineligible Taxpayers Erroneously Claiming the AOTC?

- Policy Options

- Modify the AOTC

- Consolidate the AOTC with Other Education Tax Benefits

- Alternative Policies to Reduce the Cost of Higher Education

Figures

Tables

Summary

The American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC)—originally enacted on a temporary basis by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA; P.L. 111-5) and made permanent by the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act (PATH; Division Q of P.L. 114-113)—is a partially refundable tax credit that provides financial assistance to taxpayers (or their children) who are pursuing a higher education. The credit, worth up to $2,500 per student, can be claimed for a student's qualifying expenses incurred during the first four years of post-secondary education. In addition, 40% of the credit (up to $1,000) can be received as a refund by taxpayers with little or no tax liability. The credit phases out for taxpayers with income between $80,000 and $90,000 ($160,000 and $180,000 for married couples filing jointly) and thus is unavailable to taxpayers with income above $90,000 ($180,000 for married couples filing jointly). There are a variety of other eligibility requirements associated with the AOTC, including the type of degree the student is pursuing, the number of courses the student is taking, and the type of expenses which qualify.

Before enactment of the AOTC, there were two permanent education tax credits, the Hope Credit and the Lifetime Learning Credit. The AOTC replaced the Hope Credit (the Lifetime Learning Credit remains unchanged). A comparison of these two credits indicates that the AOTC is both larger—on a per capita and aggregate basis—and more widely available in comparison to the Hope Credit. Data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) indicate that enactment of the AOTC contributed to an increase in both the aggregate value of education credits claimed by taxpayers and the number of taxpayers claiming these credits.

Education tax credits were intended to provide federal financial assistance to students from middle-income families, who may not benefit from other forms of traditional student aid, like Pell Grants. The enactment of the AOTC reflected a desire to continue to provide substantial financial assistance to students from middle-income families, while also expanding the credit to certain lower- and upper-income students. A distributional analysis of the AOTC highlights that this benefit is targeted to the middle class, with approximately half (46.6%) of the estimated $17 billion of AOTCs in 2015 going to taxpayers with income between $30,000 and $100,000.

One of the primary goals of education tax credits, including the AOTC, is to increase attendance at higher education institutions (for brevity, referred to as "college attendance"). Studies analyzing the impact education tax incentives have had on college attendance are mixed. Recent research that has focused broadly on education tax incentives that lower tuition costs and have been in effect for several years, including the Hope and Lifetime Learning Credits, found that while these credits did increase attendance by approximately 7%, 93% of credit recipients would have attended college in their absence. Even though the AOTC differs from the Hope Credit in key ways, there are a variety of factors that suggest this provision may also have a limited impact on increasing college attendance. In addition, a recent report from the Treasury Department's Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) identified several compliance issues with the AOTC.

There are a variety of policy options Congress may consider regarding the AOTC. (The credit was not modified or changed in the recent tax law enacted at the end of 2017, P.L. 115-97.) Alternatively, Congress may want to examine alternative ways to reduce the cost of higher education. This report discusses these issues and concludes with an overview of selected proposals to modify the AOTC.

Introduction

Did P.L. 115-97 Modify the AOTC?At the end of 2017, President Trump signed into law P.L. 115-971 which made numerous changes to the federal income tax for individuals and businesses.2 The final law did not change the AOTC. For an overview of education tax benefits that were changed by the law, see CRS Report R41967, Higher Education Tax Benefits: Brief Overview and Budgetary Effects, by [author name scrubbed]. However, other changes in the law could indirectly impact the value of the AOTC for certain taxpayers. As discussed in this report, up to $1,000 of the AOTC can be received a as refund and up to $1,500 can be received as a nonrefundable credit. Insofar as the law lowers a taxpayer's income tax liability, the taxpayer may also receive a smaller amount of the nonrefundable portion of the AOTC since this nonrefundable portion cannot exceed income tax liability. |

The American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC) provides financial assistance to taxpayers whose children (or who themselves) are pursuing post-secondary education. This report examines how the AOTC works, its impact on encouraging attendance at higher education institutions, and issues with administering the credit. This report provides both an in-depth description of this tax credit and an analysis of its economic impact. This report is organized to first provide an overview of the AOTC, followed by a legislative history that highlights the evolution of education tax credits from proposals in the 1960s through the recent permanent extension of the AOTC at the end of 2015. This report then analyzes the credit by looking at who claims the credit, the effect education tax credits have on increasing attendance at higher education institutions, and administrative issues with the AOTC. Finally, this report concludes with a brief overview of various policy options.

Current Law

The American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC) allows eligible taxpayers to reduce their federal income taxes by up to $2,500 per eligible student. The credit was enacted as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5), temporarily replacing the Hope Credit for 2009 and 2010. The Hope Credit was originally enacted in 1997 as part of the Taxpayer Relief Act (P.L. 105-34). As outlined in Table 1, the AOTC modified several parameters of the Hope Credit. The AOTC was extended for 2011 and 2012 by the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-312). Subsequently, the AOTC was extended for five more years, through the end of 2017, by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-240; ATRA). The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes (PATH) Act (Division Q of P.L. 114-113), made the AOTC permanent, effectively eliminating the Hope Credit.3

|

Parameter |

AOTC |

Hope Credit |

|

Maximum Value per Student |

$2,500 |

$1,800a |

|

Credit Formula |

100% of the first $2,000 in qualifying expenses + 25% of the next $2,000 in qualifying expenses. |

100% of the first $1,200 in qualifying expenses + 50% of the next $1,200 in qualifying expenses.a |

|

Income Phase-out Range |

$80,000-$90,000 The phase-out levels are not indexed for inflation. |

$48,000-$58,000a The phase-out levels were indexed for inflation. |

|

Refundability of Credit |

40% of the credit is refundable. Eligible taxpayers can receive up to $1,000 as a refund. |

Nonrefundable |

|

Qualifying Expenses |

Tuition and required enrollment fees Required course materials |

Tuition and required enrollment fees |

|

Qualifying Education Level |

First 4 years of post-secondary education |

First 2 years of post-secondary education |

|

Type of Degree Required |

Student must be pursuing a degree or other recognized education credential. |

Same as AOTC |

|

Number of Required Courses |

Student must be enrolled at least half-time for one academic period which begins in the applicable tax year. |

Same as AOTC |

|

Ineligibility Based on Felony Drug Conviction |

Students with a felony drug conviction on their record are ineligible for the credit. |

Same as AOTC |

Source: Internal Revenue Service, Publication 970: Tax Benefits for Education 2017 and Internal Revenue Service, Publication 970: Tax Benefits for Education 2008, and Internal Revenue Code Section 25A.

Notes:

a. The numeric parameters for the Hope Credit reflect the values as of 2008, the last year for which the credit was in effect.

Calculating the Credit

The AOTC is calculated as 100% of the first $2,000 of qualifying education expenses plus 25% of the next $2,000 of qualifying education expenses for each eligible student. Hence, to claim the maximum value of the credit, an eligible student will need to have incurred at least $4,000 in qualifying education expenses. The AOTC phases out for taxpayers with income4 above certain thresholds. Specifically, the AOTC begins to phase out when income exceeds $80,000 ($160,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly)5 and is completely phased out when income exceeds $90,000 ($180,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly). Thus, taxpayers with income over $90,000 ($180,000 or more for married taxpayers filing jointly) are ineligible for the AOTC.

The AOTC is a refundable credit, meaning taxpayers with little to no tax liability may still be able to benefit from this tax provision. A tax credit is refundable if, in cases where the credit is larger than the taxpayer's tax liability, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) refunds all or part of the difference. The refundable portion of the AOTC is calculated as 40% of the value of the credit the taxpayer is eligible for based on qualifying education expenses. Therefore, if the taxpayer was eligible for $2,500 of the AOTC, but had no tax liability, they could still receive $1,000 (40% of $2,500) as a refund. For an example on how to calculate the AOTC, see Appendix B.

Eligibility Requirements

There are a variety of limitations concerning who can claim the AOTC and what expenses can be used to claim the credit. These provisions are outlined below.

Qualifying Student

A qualifying student is either the taxpayer, the taxpayer's spouse, or an individual whom a taxpayer can claim as a dependent6 (in many cases, the taxpayer's child). Other requirements include the following:

- Years of Postsecondary Education: The student must be in their first four years of post-secondary education, which for most students is the first four years of undergraduate education.7

- Number of Years Credit Can Be Claimed per Student: For a given eligible student, the AOTC is only available for four years (including any years the Hope credit was claimed).

- Type of Degree: The student must be enrolled in a program that results in a degree or certificate. The credit cannot be claimed for courses that do not result in a degree or certificate. For example, it cannot be used for coursework that is used to improve jobs skills.

- Number of Courses: The student must be enrolled at least half time for at least one academic period (e.g., semester, trimester, quarter, or other period of study like a summer school session), which began in the tax year in which the credit is claimed. (Note that for most taxpayers tax years are equivalent to calendar years for the purposes of federal individual income taxes.)

- Felony Drug Conviction: The student must not have been convicted of any state or federal felony offense for possessing or distributing a controlled substance when they claim the credit.

Qualifying Education Expenses

Qualifying education expenses are tuition and certain expenses required for enrollment at a higher education institution, including the cost of course materials needed for a student's studies.

A variety of common higher education expenses do not qualify for the AOTC (even if the educational institution requires such payments for attendance), including

- room and board;

- insurance;

- medical expenses (including student health fees);

- transportation; and

- similar personal, living, or family expenses.

There are a variety of other requirements for education expenses used to claim the AOTC. First, qualifying education expenses used to claim the AOTC cannot generally be used to claim other education tax benefits.8 Second, qualifying education expenses must be reduced by the entire amount of tax-free education assistance, if that assistance can be used to pay for expenses that qualify for the AOTC.9 For example, if a taxpayer has $2,000 in qualifying tuition payments, but receives $500 in tax-free veterans' educational assistance, their qualifying education expenses for the AOTC are $1,500.10 Importantly, to the extent that the taxpayer chooses to report an otherwise tax-free grant, scholarship, or fellowship on their tax return (and hence it is subject to taxation), they may not need to reduce their education expenses by the amount of the award included in income.11 Third, qualifying expenses that are claimed in a given tax year must be incurred in that tax year. Those expenses must be for an academic period that begins either in the tax year for which the credit is claimed, or for an academic period that begins in the first three months of the following year.12 Finally, if any of the expenses used to calculate the credit value are refunded to the eligible student or taxpayer, even if they are refunded after the taxpayer files a tax return, the taxpayer must recalculate the value of the credit.

Expenses Paid By Dependents

In cases where the student is claimed as a dependent by the taxpayer, any qualifying expenses paid by the dependent are to be treated as if they were paid by the taxpayer.13 If a taxpayer does not claim an exemption for their dependent (even if entitled to the exemption), and the dependent is a qualifying student, then the qualifying student can claim the credit based on the expenses they have paid.14 At the end of 2017, President Trump signed into law P.L. 115-9715 which made numerous changes to the federal income tax for individuals and businesses, including setting the amount of the dependent exemption equal to zero from 2018 through the end of 2025. However, this does not affect the credit.16

Identification Requirements of the Taxpayer, Student, and Educational Institution

To claim the credit, the taxpayer and student (if different) must provide their name and taxpayer identification number.17 For most taxpayers, their taxpayer ID number is their social security number (SSN). Other taxpayers may use their individual taxpayer identification number (ITIN).18 For the taxpayer and the student (if different), the taxpayer ID number must have been issued before the due date of the return on which they are claiming the AOTC. Hence, if a taxpayer did not have a taxpayer ID by the due date for filing 2017 federal income tax returns for individuals (April 17, 2018), they could not claim the AOTC on their 2017 income tax return. In addition, if a ITIN is issued after the due date of the return, the taxpayer cannot amend their return and claim the credit.

The taxpayer must also provide the employer identification number (EIN) of any institution to which qualified expenses were paid for the qualifying student. As with the ID requirements for the taxpayer and student, failure to provide the EIN may lead to the taxpayer being denied the AOTC.

Disallowance of the Credit Due to Fraud or Reckless Disregard of the Rules

A tax filer is barred from claiming the AOTC for a period of 10 years after the IRS makes a final determination to reduce or disallow a tax filer's AOTC because that individual made a fraudulent AOTC claim. A tax filer is barred from claiming the AOTC for a period of two years after the IRS determines that the individual made an AOTC claim "due to reckless and intentional disregard of the rules" of the AOTC, but that disregard was not found to be due to fraud.19

Legislative History

Higher education tax credits—first enacted in 1997 by the Taxpayer Relief Act (P.L. 105-34)—originated decades earlier in the 1960s when Congress was considering federal financial support for higher education. During consideration of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA; P.L. 89-329)—which provided financial assistance to low-income Americans in the form of grants, work study, and loans20—"college tuition credits evolved as an alternative to financial aid programs."21 The Johnson Administration opposed tuition credits, believing that they would result in reduced revenues that could have otherwise been used for financial aid programs for the lowest-income Americans.22 They also believed the credit would have a limited impact in influencing whether a student did or did not attend college. According to media reports, then-Treasury Secretary Stanley Surrey stated that

a tax credit for higher education "would not result in even a single additional student going to college." The $1 billion or so that the Treasury would lose in revenue by providing a credit or several hundred dollars annually to the parents of college students can be put to better use in the form of direct financial assistance to young people who would not otherwise get to college at all.23

In the late 1970s, Congress again considered higher education tax credits.24 At the time, college costs had risen sharply and many middle-class families were not eligible for federal financial aid programs to mitigate these costs. Ultimately, Congress did not enact higher education tax credits and instead expanded existing federal student aid programs, raising the income limits so that more middle-income families would qualify.25

Nearly two decades later, in a 1996 commencement address at Princeton University, President Clinton outlined a proposal that would later become the Hope Credit, stressing that additional education beyond high school was the key to prosperity for Americans. President Clinton believed that it was essential to make the 13th and 14th years of education as universal as the first 12 years. To make these first two years of higher education affordable, President Clinton proposed the creation of the Hope Credit. The credit would be structured so that "if you work hard and earn a B average in high school, we [the federal government] will give you a tax credit to pay the cost of two years of tuition at the average community college."26 This credit was modeled on and took its name from Georgia's Help Outstanding Pupils Educationally (HOPE) Scholarship, which entitles students in Georgia with at least a B average in high school to a scholarship that covers tuition expenses at state universities and colleges.27 (The Georgia Hope Scholarship is not a tax credit—it is a direct spending program that is not tied to Georgia's state tax system.) Some experts voiced concerns that the main purpose of education tax credits was to provide a tax cut that would be popular with voters, rather than actually increase college attendance.28

Ultimately, the Hope Credit was enacted as part of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-34), a law that included numerous other tax-cutting provisions. The Hope Credit (the key parameters of this provision are outlined in Table 1) provided eligible taxpayers with up to a $1,500 credit (adjusted for inflation) for tuition expenses for the first two years of higher education. Notably, the requirement that students maintain a B average in high school for eligibility was dropped. Beyond those first two years of higher education, the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 also created the Lifetime Learning Credit (see Appendix A for more information on this credit)—but for many taxpayers the value of the Lifetime Learning Credit was less than the Hope Credit.29

In 2008, then-candidate Barack Obama proposed replacing the Hope and Lifetime Learning Credits with the American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC). As originally proposed during the presidential campaign, the AOTC would be a credit equal to up to $4,000 (100% of the first $4,000 of qualifying higher education expenses) annually.30 Crucially, the proposed credit was fully refundable, meaning that certain taxpayers with no tax liability—which includes many low-income Americans—would be able to benefit from this provision and receive up to $4,000 as a refund. In addition, the proposed credit would be computed by the IRS using a taxpayer's previous year tax data and provided directly to the higher education institution, not the taxpayer. Students who benefited from the credit would be required to perform 100 hours of community service when they had completed their education.31

On a per capita basis, the value of the AOTC, as enacted ($2,500) as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA; P.L. 111-5), was not as large as originally proposed ($4,000), but it was a larger tax benefit than the Hope Credit ($1,800), which it replaced for 2009 and 2010. (The AOTC replaced the Hope Credit, but does not affect the Lifetime Learning Credit.) For more information on key parameters of the AOTC, see Table 1. The AOTC as enacted had a maximum value of $2,500 and was partially refundable. Taxpayers with little or no tax liability were eligible to receive a part of the credit—40% of its value—as a refund. In addition, unlike the Obama-proposed AOTC, the actual credit did not go directly to educational institutions but instead was claimed by eligible households based on their qualifying education expenses. Finally, the community service requirement was not included as a provision of the final credit. The AOTC was extended for 2011 and 2012 by the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-312). At the end of 2012, the AOTC was extended for five additional years, through the end of 2017, by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-240; ATRA). The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes (PATH) Act (Division Q of P.L. 114-113), made the AOTC permanent, effectively eliminating the Hope Credit.32 The PATH Act also included a number of provisions intended to reduce improper payments of the AOTC. These provisions included the disallowance of the credit due to fraud or a reckless disregard of the credit's rules and the ID requirements for the taxpayer, student, and educational institution.

Analysis

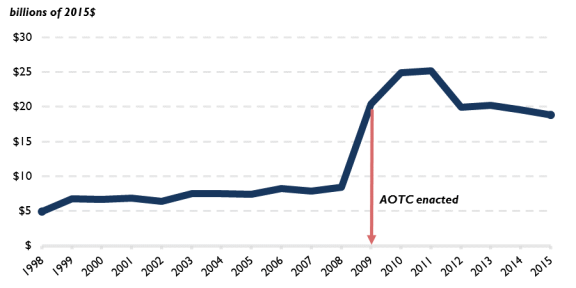

The enactment of the AOTC has resulted in a substantial increase in the amount of education credits claimed by taxpayers, as illustrated in Figure 1. The increase in education tax credits underscores a broader trend, which began in 1997, of providing federal financial assistance for higher education through the tax code.33 In light of the budgetary implications of the AOTC, Congress may be interested in understanding the economic impact of this provision.

The following sections provide an economic analysis of the AOTC. They include an examination of who claims the credit, its effectiveness in boosting college attendance, and a discussion of administrative issues concerning the AOTC. Analysis of who claims the AOTC indicates that it tends to provide the greatest benefit to middle-income and upper-middle-income taxpayers. From an economic standpoint, the AOTC is an effective tax policy if it causes individuals to engage in a desired behavior—in this case attaining a post-secondary education. Research suggests that the presence of the AOTC is not a major factor in increasing attendance at post-secondary institutions, especially for middle- and upper-middle-income taxpayers who are its primary beneficiaries. Hence, this credit may not be influencing behavior for many recipients and instead may be largely going to many taxpayers that would have pursued a higher education or sent their children to an institution of higher education absent the credit. In addition, the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) has identified administrative issues with the AOTC and its predecessor, the Hope Credit.

Who Benefits from the AOTC?

When education tax credits were first enacted in 1997, they were expressly intended to provide financial assistance to middle-income taxpayers.34 Data confirm that the AOTC primarily benefits middle-income taxpayers, although lower-income taxpayers and upper-middle income taxpayers also receive the credit.

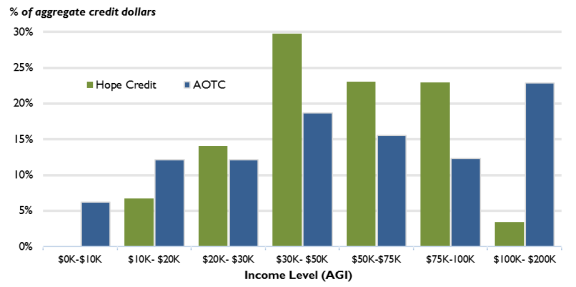

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of the AOTC by adjusted gross income (AGI) level, underscoring that this tax credit provides the majority of its benefits to taxpayers with income between $30,000 and $100,000. Specifically, in 2015, approximately 46.6% of AOTC dollars were claimed by taxpayers with income between $30,000 and $100,000. Two components of the AOTC make the credit available to certain low- and upper-income taxpayers.35

|

|

Source: CRS Calculations using IRS Statistics of Income (SOI), Table 3.3 and additional data provided by the IRS available to congressional clients upon request. Note: No credit dollars are claimed by taxpayers with AGI over $200,000 due to the phase-out parameters of the credit. |

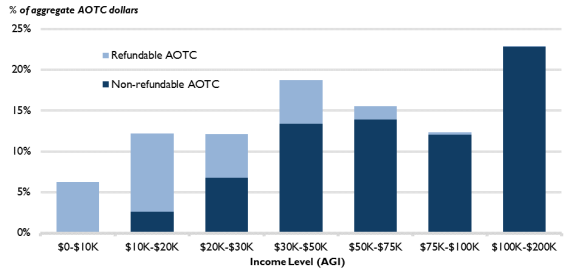

The first component of the AOTC that expanded its availability beyond middle-income taxpayers—in this case to low-income taxpayers—is its refundability.36 Tax credits reduce tax liability dollar for dollar of the value of the credit, but by definition cannot reduce tax liability below zero. Hence, to benefit from the credit, a taxpayer must have sufficient income to owe taxes. The AOTC is refundable such that taxpayers can receive up to 40% of the value of their AOTC—a maximum of $1,000 per qualifying student—as a refund, even if they have no tax liability. In 2015, taxpayers with income under $10,000 received 6.2% of AOTC benefits, while taxpayers with income between $10,000 and $20,000 received 12.2% of AOTC benefits. In both cases, the majority of the value of the credit was the AOTC's refundable portion.

As further underscored in Table 2, refundability of the tax credit benefits certain low-income taxpayers. For example, more than half (an estimated 55.3%) of the refundable portion of the AOTC is claimed by taxpayers with less than $20,000 of income. In contrast, a little over a twentieth (an estimated 7.1%) of the refundable portion of the AOTC is claimed by taxpayers with incomes between $50,000 and $200,000.

The second component of the AOTC that expanded its availability beyond middle-income taxpayers—in this case to higher-income taxpayers—is the income level at which the credit phases out. As illustrated in Table 1, the AOTC is available to taxpayers with income up to $90,000 ($180,000 for married joint filers). According to estimates provided in Table 2, in 2015 taxpayers with income between $100,000 and $200,000 claimed an estimated $3.8 billion of the credit (22.9% of the total amount of the AOTC).

|

Nonrefundable AOTC |

Refundable AOTC |

Total AOTC |

Total Income Tax Liability |

|||||

|

Income (AGI) |

Amount (millions) |

% of Total |

Amount (millions) |

% of Total |

Amount (millions) |

% of Total |

Amount (millions) |

% of Total |

|

$0-$10K |

$6 |

0.1% |

$1,039 |

21.8% |

$1,045 |

6.2% |

$2,547 |

0.2% |

|

$10K-$20K |

$442 |

3.7% |

$1,600 |

33.5% |

$2,042 |

12.2% |

$7,435 |

0.5% |

|

$20K-$30K |

$1,137 |

9.5% |

$902 |

18.9% |

$2,039 |

12.1% |

$17,833 |

1.2% |

|

$30K-$50K |

$2,253 |

18.7% |

$892 |

18.7% |

$3,145 |

18.7% |

$64,338 |

4.2% |

|

$50K-$75K |

$2,333 |

19.4% |

$272 |

5.7% |

$2,605 |

15.5% |

$107,583 |

7.0% |

|

$75K-$100K |

$2,022 |

16.8% |

$50 |

1.0% |

$2,072 |

12.3% |

$112,620 |

7.4% |

|

$100K-$200K |

$3,831 |

31.9% |

$15 |

0.3% |

$3,846 |

22.9% |

$331,550 |

21.7% |

|

$200K+ |

$0 |

0.0% |

$0 |

0.0% |

$0 |

0.0% |

$885,656 |

57.9% |

|

Total |

$12,025 |

100.0% |

$4,770 |

100.0% |

$16,795 |

100.0% |

$1,529,562 |

100.0% |

Source: CRS Calculations using IRS Statistics of Income (SOI), Table 3.3 and additional data provided by the IRS available to congressional clients upon request.

Notes: Items may not sum due to rounding.

In comparison to its predecessor—the Hope Credit—the AOTC has shifted more of its benefits to higher-income taxpayers, as illustrated in Figure 3. For example, approximately one-fifth (18.4%) of AOTC dollars was claimed by taxpayers with income under $20,000, almost three times the share of Hope Credit dollars (6.8%) claimed by taxpayers in this income class. In contrast, more than a fifth (22.9%) of AOTC dollars was claimed by taxpayers with income between $100,000 and $200,000, more than six times the share of Hope Credit dollars (3.4%) claimed by taxpayers in this income class. Notably, these gains were accompanied by the reduction in the share of AOTC dollars (in comparison to the Hope Credit) that went to taxpayers with income between $20,000 and $100,000. Specifically, 89.8% of Hope Credit dollars was claimed by taxpayers in this income range, in comparison to 58.7% of AOTC dollars.

Given that children of taxpayers at the upper end of the income scale are more likely to attend a post-secondary educational institution than their lower-income counterparts,37 providing education incentives to these taxpayers may not increase enrollment at higher education institutions, but instead reward behavior that would have occurred absent the incentive.

Does the AOTC Increase Attendance at Post-Secondary Educational Institutions?

One of the primary goals38 of the AOTC is to increase attendance at post-secondary educational institutions.39 (For brevity, this report may refer to institution of higher education as "college," although the AOTC is available for students attending eligible colleges, universities, and trade schools.40) Increased college attendance may not only lead to benefits for individuals in terms of higher wages, but also may provide societal benefits including increased productivity and innovation.41,42 There are a variety of factors that may determine whether a student attends an institution of higher education, including family socioeconomic level, student educational aspirations, peer support, academic performance, and the cost of college.43

The AOTC, like other forms of traditional student aid and other forms of tax-based financial aid, subsidizes some of the costs associated with higher education and thus reduces its cost. The effect that a cost reduction has on post-secondary attendance will depend on how sensitive a student's (and his family's) decision to attend college is to price.44 Some students will be very sensitive to price and insofar as the AOTC reduces cost, this tax benefit would be expected to induce them to attend college. On the other hand, certain students will attend college irrespective of price. In this case, the AOTC rewards students and their families for an action—attending college—that they would have made regardless of the credit's availability, and the credit is simply a windfall gain to certain taxpayers.

Historically, studies analyzing the effect of education tax incentives on college attendance were mixed. Because of the limited amount of data available concerning the AOTC, research instead focused more broadly on education tax incentives that lower tuition costs and that have been in effect for several years—namely the Hope Credit, the Lifetime Learning Credit, and the above-the-line tuition and fees deduction (see Appendix A for more information on these tax benefits).45 Analysis by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) conducted two years after the Hope and Lifetime Learning Credits were enacted concluded that "tax credits are unlikely to cause substantial increases in college enrollment."46 A later study echoed the CBO's conclusion, finding that the Hope and Lifetime Learning Credits had no impact on college enrollment, although there were possible limitations with the analysis.47

More recent research48 has found that while tax-based aid did have an impact on college attendance, a significant proportion of recipients—93%—would have attended college in the absence of these benefits.49 One study noted which included analysis of the AOTC found that education credits had "a meager effect on college-going."50 Another succinctly states that "the tax credit and tax deduction [the tuition and fees deduction, see Table A-1], which account for most of the tax expenditures for postsecondary education, do not affect school decisions."51

Based on the available research and current data on who receives the AOTC, there may be several factors that limit the AOTC's impact on college attendance.

- Income Level of Beneficiaries: Research indicates that students from lower-income households are more sensitive to the price of college when deciding whether to attend college, in comparison to their higher-income counterparts.52 Policies that reduce the price of college, like the AOTC, would then be expected to increase enrollment if they were targeted towards lower-income students. However, as previously discussed, the AOTC primarily benefits middle-income taxpayers, and hence may result in a windfall to many of these taxpayers.

- Timing of Tax Benefit: Unlike aid and loans received before or at the time of attendance, the AOTC, like other education tax benefits (e.g., the Lifetime Learning Credit and tuition and fees deductions, see Appendix A) may be received up to 15 months after education expenses are incurred.53 For families who have limited resources to pay education expenses up front (e.g., they have insufficient savings to pay for college costs), tax credits will provide little benefit in financing their college costs and so will play an insignificant role in whether they attend college or not.54,55 However, the AOTC may enable families that do receive loans to ultimately reduce their loan balances by applying the credit amounts to loan balances.

- Complexity of Benefit: There are a variety of tax benefits that students or their families can claim when they file their taxes, including the AOTC, the Lifetime Learning Credit, and the tuition and fees deduction. These tax preferences differ in a variety of ways including eligibility criteria, benefit levels, and income phase-outs (see Table 1 and Appendix A). The value of the tax benefit may also depend on the amount of student aid taxpayers or their children receive. Given these numerous factors, taxpayers may not know which tax preference provides the most benefit until they file their taxes—and calculating the tax benefit of each provision can "place substantial demands on the knowledge and skills of millions of students and families."56 This complexity may result in some taxpayers choosing not to claim a tax benefit like the AOTC, or not claiming the tax provision that provides the greatest benefit. Studies have found that between 27%57 and 37%58 of taxpayers failed to claim eligible education tax benefits. In addition, uncertainty in the amount of the credit they may receive may result in many families excluding the credit when making decisions about college attendance.59

- Institutional Response: Some experts have expressed a concern that colleges and universities—especially those with tuition below the maximum amount subsidized by education tax credits—may respond to the availability of education tax credits like the AOTC by increasing their tuition.60 This would lessen the ability of education tax credits to lower the after-tax price of college. For example, if a student is eligible for a $2,000 credit, but their college increases tuition by $2,000, the price of college will effectively be unchanged and the credit will entirely benefit the college. If the college raises tuition for all students, irrespective of whether they are eligible for the credit, some students may actually see the cost of college rise. Studies of the Hope and Lifetime Learning Credits have found little evidence that they resulted in tuition increases.61 More recent research has also found no evidence of this effect.62

While there are a variety of factors that may limit the ability of the AOTC to increase college attendance, research indicates that other forms of student aid including Pell Grants may have a similar impact as the AOTC on college attendance.63 Hence, some of the limitations of the AOTC in increasing college attendance may apply more broadly to other forms of federal financial assistance.64

Finally, federal financial assistance for higher education may reduce the after-tax price of college, but cost is just one factor that influences college attendance. Other factors, like college preparedness, may also influence not only whether students attend college, but whether they graduate.65 Research indicates that college preparedness tends to be correlated with income, with lower-income students less prepared for college than their higher-income counterparts.66 Thus, other societal factors that exist prior to college may limit the impact aid has on increasing college attendance, especially among needier students.67

Are Ineligible Taxpayers Erroneously Claiming the AOTC?

Taxpayers are more likely to claim tax benefits when they are simple and straightforward to claim. However, the trade-off for ease in claiming tax benefits is that it may result in increased errors—both intentional and unintentional—as illustrated in a 2015 Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) report on the AOTC.68

The 2015 TIGTA report examined 2012 income tax returns that claimed this credit and identified 3.6 million taxpayers who received more than $5.8 billion in AOTC credits that appeared to be erroneous. Of these potentially erroneous credits, the majority ($3.2 billion) were a result of the IRS being unable to confirm that the students claimed on the taxpayers' tax returns attended a college or university.69 In addition, the TIGTA report found that $1.3 billion in potentially erroneously claimed credits could be attributed to students not attending an eligible educational institution (i.e., they were not certified by the Department of Educations to receive federal student aid funding). One way the IRS could verify that a student attended a college or university would be to match information returns provided by colleges and universities—the 1098-T—with information provided on a tax return. The 1098-T provides the name and taxpayer identification number of the student and the name and employer identification number (EIN) of the college or university. On a federal income tax return, the taxpayer must fill out Form 8863 which also includes the name and taxpayer ID of the student and the name and EIN of the college or university. A discrepancy between these two forms could indicate an erroneous claim for the credit. However, as TIGTA noted in its report, the IRS does not always receive the 1098-T at the time tax returns are filed. For example, colleges and universities are required to file the form 1098-T electronically by March 31. The deadline for most taxpayers to file their federal income tax return is April 15, and many file earlier. Tax filing season generally begins at the end of January. TIGTA proposed the introduction of legislation to require that 1098-Ts be filed no later than January 31. To date, this proposal has not been enacted into law.

TIGTA also suggested the IRS use Department of Education databases on education institutions to verify that a college or university listed on a Form 8863 is a qualifying institution for the credit. While the IRS does not currently have statutory authority to use these databases to verify AOTC claims and deny the credit before a refund is issued, TIGTA recommended using these databases in post-refund examinations of tax returns that claimed the AOTC.

Reducing erroneous claims of the AOTC may require higher that education institutions provide information to the IRS before tax returns are filed. It may also necessitate that the IRS improve its compliance checks, perhaps by coordinating with the Department of Education to share additional information that can be used by the IRS to flag questionable returns for audit. However, as TIGTA highlights "the IRS does not have the audit resources it needs to make any significant reduction in the loss of funds to the Government resulting from paying erroneous claims."70 Hence even with better data, the IRS may still be limited in recovering erroneously claimed credits. While it may be more beneficial to use third-party data to verify taxpayer eligibility for the AOTC during the filing season, the IRS does not currently have the authority to do so. Legislation would be needed to provide the IRS with the authority to use databases—like those at the Department of Education—during tax filing so that erroneous claims are denied before tax refunds are issued.

Policy Options

Congress may also want to consider modifying the AOTC, or consolidating the AOTC with other education tax benefits. Finally, Congress may want to consider federal financial aid for higher education holistically, which could include alternative ways to reduce the cost of higher education.

Modify the AOTC

Policymakers may choose to modify the AOTC. The AOTC could be modified in a variety of ways. Policymakers may choose to either expand or limit certain parameters of the credit, for example, by using a different credit formula, changing the amount of qualifying expenses that can be used to claim the credit, adjusting the portion of the credit (currently 40%) that is refundable, modifying the income level at which the credit phases out, allowing taxpayers to claim the credit for either more or less than four years of post-secondary education, changing the definition of qualifying expenses (for example to include room and board), and providing nondegree-seeking students (such as students in job-training programs) eligibility for the credit.

If desired, certain changes to the AOTC may expand the credit's availability to lower-income recipients. For example, policymakers could make a greater percentage of the credit refundable. They could also modify the credit such that a lower level of expenses would be necessary to claim the maximum credit (for example, the formula could be 100% of the first $2,500 of qualifying expenses). In contrast, other modifications, like increasing the income level at which the credit phases out, may expand the credit to additional upper-income taxpayers. These changes may increase confusion among taxpayers, especially when trying to determine which higher education tax credit (or the above-the-line deduction for tuition and fees) provides the greatest benefit.

Consolidate the AOTC with Other Education Tax Benefits

Policymakers may instead choose to consolidate the AOTC with other education tax incentives that reduce tuition costs—the Lifetime Learning Credit and tuition and fees deduction. Prior to enactment of the AOTC, there have been several legislative proposals to consolidate these tax benefits. For example, in the 109th Congress, Senator Baucus introduced the Education Competitiveness Act of 2006 (S. 3902), which repealed the Hope and Lifetime Learning Credits and replaced them with a fully refundable $2,000 higher education tax credit. In the 110th Congress, the bipartisan Universal Higher Education and Lifetime Learning Act of 2007 (H.R. 2458) consolidated the Hope and Lifetime Learning Credits and the tuition and fees deduction into one partially refundable credit with a maximum value of $3,000 (50% or up to $1,500 was available as a refund). In addition, this legislation set a lifetime limit of $12,000 per student for the credit (the credit could be claimed for no more than two years of graduate education). More recently, the House-passed version of H.R. 1 (the version of the bill which passed the House as amended on November 16, 2017) would have eliminated the Lifetime Learning Credit while simultaneously expanding the AOTC to a five-year credit, with a smaller credit in the fifth year. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that this change would have cost $17.8 billion between 2017 and 2028. (Policymakers could, however, consolidate and modify education tax credits in such a way that would increase revenue, decrease revenue, or remain revenue neutral.) Ultimately, this change was not included in the final bill, which was signed into law on December 22, 2017.

Alternative Policies to Reduce the Cost of Higher Education

The AOTC is one of a variety of policies designed to lower the cost of education to students and their families and hence increase accessibility to higher education. Policymakers may pursue several options concerning the AOTC. Alternatively, they may choose to reevaluate the federal government's role in higher education financing more broadly by considering education tax incentives like the AOTC in context with other forms of federal financial aid to develop a broader higher education financing policy. For example, policymakers could expand the types of expenses that would qualify for the AOTC such that a low-income student who uses a Pell Grant to pay for most or all of their tuition could still benefit from the AOTC.71 Or policymakers may choose to reformulate the federal government's role in higher education financing entirely by encouraging alternative financing mechanisms like human capital contracts,72 which allow a student to repay an investor a percentage of future earnings for a fixed period of time. Although there may be shortfalls with this particular proposal,73 approaching higher education policy holistically—instead of tax policy versus traditional financial aid—may provide more benefit to low- and middle-income students.

Appendix A. Other Tax Provisions for Current-Year Higher Education Expenses

Under current law, there are a variety of benefits available to taxpayers for current-year higher education expenses. A complete list can be found in CRS Report R41967, Higher Education Tax Benefits: Brief Overview and Budgetary Effects, by [author name scrubbed].

Of these benefits, the AOTC, the Hope Credit, the Lifetime Learning Credit, and the above-the-line deduction for tuition and fees74 are often discussed together as the main tax benefits for current-year higher education expenses (under current law, the tuition and fees deduction is scheduled to expire at the end of 2017). A taxpayer cannot claim both the deduction and an education credit (Lifetime Learning or AOTC) for the same student in the same year. Details on the Lifetime Learning Credit and the tuition and fees deduction are provided below.

|

Lifetime Learning Credit |

Tuition and Fees Deduction |

|

|

Type of Benefit |

Tax credit |

Above-the-line deduction from gross income |

|

Maximum Value |

$2,000 credit per taxpayer |

$4,000 deduction per student |

|

Credit Formula |

20% of first $10,000 of expenses |

Not applicable |

|

Income Phase-out Range |

$57,000-$67,000 ($114,000-$134,000 for married joint filers) in 2017 |

$65,000-$80,000 ($130,000-$160,000 for married joint filers) |

|

Refundability |

Nonrefundable |

Not applicable |

|

Qualifying Expenses |

Tuition and required enrollment fees |

Same |

|

Qualifying Education Level |

Post-secondary education, including coursework to acquire or improve job skills. The credit is available for an unlimited number of years. |

Post-secondary education |

|

Type of Degree Required |

No degree requirement |

Undergraduate or graduate degree |

|

Number of Required Courses |

No requirement |

No requirement |

Source: Table compiled by CRS using information from the Internal Revenue Code and IRS Publication 970: Tax Benefits for Educations, 2017.

Appendix B. Calculating the AOTC: A Stylized Example

The Smiths pay $8,000 of college expenses for Sarah. Of the $8,000 in expenses, $6,000 are for tuition and are considered qualifying expenses, while $2,000 are for room and board expenses, which are not qualifying expenses.

The Smiths' daughter Sarah attends University X in the same year her parents incur the $8,000 in college expenses. The Smiths file their tax return as married joint filers. They have a combined income of $100,000, which is below the level at which the credit begins to phase out ($160,000).

To help pay for these costs, the university gives Sarah a $4,000 tax-free scholarship (i.e., none of the scholarship is subject to taxation), which can be used to pay for any part of Sarah's university expenses. The remainder of the cost is paid for with student loans. Sarah is a first-year undergraduate at University X enrolled full-time in a degree program and is eligible to claim the AOTC. She is claimed as a dependent by the Smiths.

Step 1. Qualifying Expenses: Sarah has $6,000 in qualifying expenses that are reduced by the entire value of her tax-free scholarship. Importantly, even though the tax-free scholarship can be used for expenses aside from tuition and fees, because it is tax-free, she must reduce her qualifying expenses by the total value of the award. If she had used the $4,000 award to pay for room and board (not a qualifying expense) and she had also reported it on her (or her parent's income tax return), she would not need to reduce her qualifying expenses by the value of the award. However, because the award is entirely tax-free, her $6,000 in qualifying expenses are reduced by $4,000 and she has $2,000 in qualifying expenses.

Step 2. Calculating the AOTC: Because Sarah has $2,000 in qualifying expenses, her parents can claim a $2,000 AOTC (100% x first $2,000 of qualifying expenses).

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

The original title of the law, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, was stricken before final passage because it violated what is known as the Byrd rule, a procedural rule that can be raised in the Senate when bills, like the tax bill, are considered under the process of reconciliation. The actual title of the law is "To provide for reconciliation pursuant to titles II and V of the concurrent resolution on the budget for fiscal year 2018." For more information on the Byrd rule, see CRS Report RL30862, The Budget Reconciliation Process: The Senate's "Byrd Rule," by [author name scrubbed] |

| 2. |

For more information on the changes made to the tax code by P.L. 115-97 see CRS Report R45092, The 2017 Tax Revision (P.L. 115-97): Comparison to 2017 Tax Law, coordinated by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 3. |

The Tax Technical Corrections Act of 2018, included as part of P.L. 115-141, made numerous technical corrections to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), including modifying the text of IRC Section 25A to eliminate text that references the Hope credit. |

| 4. |

Income is, for the purposes of the AOTC, Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI), which is adjusted gross income (AGI) modified by adding back the value of (if applicable) the foreign earned income exclusion, the foreign housing exclusion, the foreign housing deduction, and the exclusion of income by bona fide residents of American Samoa or Puerto Rico. |

| 5. |

Taxpayers who file their tax returns as "married filing separately" cannot claim the AOTC. |

| 6. |

Taxpayers must claim an exemption on their tax returns for dependents who are eligible students in order to claim the credit. |

| 7. |

In addition, a taxpayer can only claim the AOTC for four calendar years per student, even if it takes the student more than four calendar years to complete their undergraduate education. |

| 8. |

Specifically, (1) the above-the-line tuition and fees deduction; (2) the Lifetime Learning Credit; (3) the tax-free distributions from 529 qualified tuition plans (QTPs) and Coverdell Education Savings Accounts; and (4) other deductions for higher education expenses on a taxpayer's income tax return, for example, as a business expense. |

| 9. |

Tax-free education assistance includes tax-free scholarships and fellowships, Pell Grants, employer-provided educational assistance, or veterans' educational assistance. Taxpayers do not need to reduce qualified expenses if part or all of them are paid for by a loan, a gift, an inheritance, or a withdrawal from the student's personal savings. |

| 10. |

IRC Section 25A(g)(8) states that the credit is disallowed if the taxpayer does not receive a statement which contains information detailing both expenses incurred as well as the amount of tax-free educational assistance provided on behalf of the student. The statement used for this purpose is IRS Form 1098-T, which includes information on both amounts billed and payments received for qualifying expenses, and thus enables taxpayers to calculate the amount of out of pocket qualifying education expenses they can use to claim the AOTC. This requirement was included in Section 804 of P.L. 114-27. The law also provides the IRS with the authority to create exceptions to this requirement. Of note, in IRS Publication 970 for 2017, the IRS states: "However, for tax year 2017, a taxpayer may claim the credit if the student doesn't receive a Form 1098-T because the student's educational institution isn't required to send a Form 1098-T to the student under existing rules (for example, if the student is a nonresident alien, has qualified education expenses paid entirely with scholarships, has qualified education expenses paid under a formal billing arrangement, or is enrolled in courses for which no academic credit is awarded)." Internal Revenue Service, Tax Benefits for Education, Publication 970, 2017, p. 9, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p970.pdf. If a student's educational institution isn't required to provide a Form 1098-T to the student, a taxpayer may claim the credit without a Form 1098-T if the taxpayer otherwise qualifies, can demonstrate that the taxpayer (or a dependent) was enrolled at an eligible educational institution, and can substantiate the payment of qualified tuition and related expenses. |

| 11. |

Among other conditions, the terms of the grant, scholarship, or fellowship must allow its use for nonqualified expenses. Whether it makes sense for the taxpayer to include the amounts in income will depend on that taxpayer's specific circumstances. |

| 12. |

For example, if in December 2011 a taxpayer pays $3,000 of qualified tuition for their child's spring 2012 semester which begins in February 2012, they can use that $3,000 worth of expenses to claim the AOTC on their 2011 tax return. |

| 13. |

See IRC Section 25A(g)(3). This provision was originally included as part of the Hope Credit, created by P.L. 105-34. |

| 14. |

See IRC Section 25A(g)(3); Internal Revenue Service, Tax Benefits for Education, Publication 970, 2017, p. 19, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p970.pdf. |

| 15. |

The original title of the law, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, was stricken before final passage because it violated what is known as the Byrd rule, a procedural rule that can be raised in the Senate when bills, like the tax bill, are considered under the process of reconciliation. The actual title of the law is "To provide for reconciliation pursuant to titles II and V of the concurrent resolution on the budget for fiscal year 2018." For more information on the Byrd rule, see CRS Report RL30862, The Budget Reconciliation Process: The Senate's "Byrd Rule," by [author name scrubbed] |

| 16. |

IRC Section 152(d)(5)(B). For more information on the changes made to the tax code by P.L. 115-97, see CRS Report R45092, The 2017 Tax Revision (P.L. 115-97): Comparison to 2017 Tax Law, coordinated by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 17. |

IRC Section 25A(g)(1). |

| 18. |

For more information on ITINs, see CRS Report R43840, Federal Income Taxes and Noncitizens: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 19. |

See IRC Section 25A(b)(4). |

| 20. |

For more information on the Higher Education Act, see CRS Report RL34214, A Primer on the Higher Education Act (HEA), by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 21. |

Benjamin Rue Silliman, "Federal Tax Policy in the Making: 32 Year to Enact College Tuition Tax Credits," Review of Business, vol. 23, no. 1 (Winter 2002), pp. 38-44. |

| 22. |

"Scholarships Featured in College Aid Bill," CQ Almanac 1965, 21st ed., pp. 294-305, http://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/cqal65-1259145. |

| 23. |

Eileen Shanahan, "Tax Withholding May Be Revised: Administration Studies Plan to Reduce Underpayments—Aid Unlikely This Year," The New York Times, March 8, 1965, p. 1. |

| 24. |

For example, see in the 95th Congress, H.R. 12050, the Tuition Tax Relief Act; H.R. 11746, the College Tuition Tax Credit Act; and S. 2142, the Tuition Tax Credit Act. |

| 25. |

See Benjamin Rue Silliman, "Federal Tax Policy in the Making: 32 Year to Enact College Tuition Tax Credits," Review of Business, vol. 23, no. 1 (Winter 2002), pp. 38-44. |

| 26. |

Princeton University, "President William J. Clinton Commencement Address," June 4, 1996, http://www.clintonlibrary.gov/assets/storage/Research%20-%20Digital%20Library/Reed-Education/91/647429-hope-scholarships-2.pdf. |

| 27. |

For more information, see Joint Committee on Taxation, Analysis of Proposed Tax Incentives for Higher Education, Prepared for March 5 Hearing by House Ways and Means Committee, March 4, 1997, JCS-3-97. |

| 28. |

Douglas Lederman, "The Politicking and Policy Making Behind a $40-Billion Windfall," Chronicle of Higher Education, vol. 44, no. 14 (November 28, 1997). |

| 29. |

The Lifetime Learning Credit provides a nonrefundable tax credit for tuition and required fees that is equal to 20% of the first $10,000 in qualified tuition and related expenses per taxpayer (unlike the Hope Credit which is calculated per student). Between 1998 and 2002, the credit was equal to 20% of the first $5,000 of qualified tuition and related expenses. Hence between 1998 and 2002, the maximum value of the Lifetime Learning Credit was $1,000 per taxpayer, whereas the maximum value of the Hope Credit was $1,500 per student. The maximum amount of qualified tuition and related expenses used to calculate the Lifetime Learning Credit is not indexed for inflation, whereas the level of expenses used to calculate the Hope Credit is indexed for inflation. In 2008, the last year both the Hope Credit and the Lifetime Learning Credit were in effect, the maximum value of the Hope Credit was $1,800 per student and the maximum value of the Lifetime Learning Credit was $2,000 per taxpayer. In 2008, if total qualified education expenses were less than $9,000, most taxpayers would benefit more from the Hope Credit. |

| 30. |

For more information, see "Obama Says Tax Plan Offers More Tax Cuts; Some Analysts Question Revenue Estimates," Bloomberg BNA Daily Tax Report, August 29, 2008 and http://www.finaid.org/educators/presidentialcandidates.phtml. In 2008 presidential campaign documents, then-candidate Obama did not indicate the duration of the credit. According to a 2007 speech, candidate Obama stated: "I'll create a new and fully refundable tax credit worth $4,000 for tuition and fees every year, which will cover two-thirds of the tuition at the average public college or university." For more information, see Obama for America, "In Major Policy Speech, Obama Announces Plan to Reclaim the American Dream, Bettendorf IA," press release, November 7, 2007, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=93290#axzz1x7TOkCk9. |

| 31. |

"Obama Says Tax Plan Offers More Tax Cuts; Some Analysts Question Revenue Estimates," BNA Daily Tax Report, August 29, 2008. |

| 32. |

The Tax Technical Corrections Act of 2018, included as part of P.L. 115-141, made numerous technical corrections to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), including modifying the text of IRC Section 25A to eliminate text that references the Hope credit. |

| 33. |

For more information, see Elaine Maag, David Mundel, and Lois Rice, et al., Subsidizing Higher Education through Tax and Spending Programs, Tax Policy Center, Tax Policy Issues and Options No.18, May 2007. |

| 34. |

Douglas Lederman, "The Politicking and Policy Making Behind a $40-Billion Windfall," Chronicle of Higher Education, vol. 44, no. 14 (November 28, 1997), p. A28. |

| 35. |

Notably, one parameter of the AOTC still limits its availability to lower-income taxpayers (and which remains unchanged from the Hope Credit). Specifically, the AOTC must be reduced by tax-free educational assistance, including Pell Grants, which generally benefit low-income students and their families. Since the value of the credit depends on the total amount of qualifying expenses, then all else being equal, reducing the amount of qualifying expenses reduces the value of the credit amount for taxpayers who receive tax-free educational assistance. As discussed earlier, taxpayers may choose in certain circumstances to be taxed on otherwise tax-free grants and scholarships, which may limit the reduction in the AOTC. |

| 36. |

Dynarski and Scott-Clayton also argue that the expansion of the AOTC to more types of expenses, specifically required course materials, increased the amount of expenses that low-income taxpayers could use to calculate their credit amount, potentially resulting in a larger credit for some taxpayers. For more information, see Susan Dynarski and Judith Scott-Clayton, "Tax Benefits for College Attendance," NBER Working Paper No. 22127, March 2016. |

| 37. |

For more information, see Elaine Maag and Katie Fitzpatrick, "Federal Financial Aid for Higher Education: Programs and Prospects," The Urban Institute, January 1, 2004, pp. 5-6, http://www.urban.org/uploadedPDF/410996_federal_financial_aid.pdf. In addition, research from the U.S. Department of Education indicates that "Differences in immediate college enrollment rates by family income, race/ethnicity, and sex were observed over time. In every year between 1975 and 2009, the immediate college enrollment rates of high school completers from low- and middle-income families were lower than those of high school completers from high-income families. Most recently, in 2009, the immediate college enrollment rate of high school completers from low-income families was 55 percent, 29 percentage points lower than the rate of high school completers from high-income families (84 percent). The immediate college enrollment rate of high school completers from middle-income families (67 percent) also trailed the rate of their peers from high-income families by 17 percentage points." U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2011). The Condition of Education 2011 (NCES 2011-033), Indicator 21, http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=51. |

| 38. |

The AOTC may have other policy objectives. For example, the AOTC, like other forms of financial aid for higher education, may also enable students to be more selective in choosing the college they will attend, allowing them to attend a more expensive institution. The credit may also increase the time a student spends in school. Finally, the AOTC may enable students or their families to take on less debt to finance their education. Studies that have evaluated education tax incentives have not focused on these potential aspects of higher education tax credits, so they are not the focus of this report. |

| 39. |

Most studies have focused on the impact of tax credits on college attendance, but have not focused more broadly on college completion. While people who receive some college education generally earn more even if they do not graduate, the size of this effect is still being debated. |

| 40. |

For a comprehensive assessment on the impact of a wide variety of education benefits (including tax credits) on student behavior, see Susan Dynarski and Judith Scott-Clayton, "Tax Benefits for College Attendance," NBER Working Paper No. 22127, March 2016. |

| 41. |

This economic rationale may be referred to as the "positive externality" rationale for government interventions in higher education. Broadly, an externality is a cost or benefit associated with a transaction that is not reflected in market prices borne by the buyer or seller. In the case of a positive externality associated with education, the positive benefit to society in terms of increased productivity and innovation is greater than the benefit to the individual, which may result in under-investment in education from a social perspective. In addition to the positive social benefits discussed, increased education is also correlated with reduced reliance on government assistance programs, less crime, and greater civic participation. For more information, see Elaine Maag and Katie Fitzpatrick, "Federal Financial Aid for Higher Education: Programs and Prospects," The Urban Institute, January 1, 2004, http://www.urban.org/publications/410996.html. |

| 42. |

While one economic rationale for federal financial aid for college attendance is the "positive externality" rationale, there are other rationales for government intervention in higher education financing. First, private capital markets may be unwilling to lend to students to finance their higher education. Many students do not have sufficient savings to finance their education. And since students often lack property to pledge as collateral for student loans, private lenders must charge high interest rates to reflect the losses they would incur (and could not recover) if the student defaults. To rectify this problem, the federal government guarantees student loans which effectively absorbs private lenders default risk. A second reason the government may provide financial assistance for higher education is to expand access to college, and since college-educated workers earn more than those with a high-school diploma, to ultimately mitigate income inequality. |

| 43. |

Jacqueline E. King, "Improving the Odds: Factors that Increase the Likelihood of Four-Year College Attendance Among High School Seniors," College Board Report No. 96-2, 1996, http://professionals.collegeboard.com/profdownload/pdf/RR%2096-2.PDF. |

| 44. |

For estimates of the AOTC, Hope and Lifetime Learning credits' effects on the type of college attended, the resources experienced in college, tuition paid, and financial aid received, see George B. Bulman and Caroline M. Hoxby, "The Returns to the Federal Tax Credits for Higher Education," NBER Working Paper No. 20833, January 2015. |

| 45. |

For more information on the Lifetime Learning Credit and the tuition and fees deduction, see CRS Report R41967, Higher Education Tax Benefits: Brief Overview and Budgetary Effects, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 46. |

Congressional Budget Office, An Economic Analysis of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997, CBO Paper, April 2000, p. 20, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/12200. |

| 47. |

Bridget T. Long, "The Impact of Federal Tax Credits for Higher Education Expenses," National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2004, p. 137. According to the Government Accountability Office, there were a variety of limitations to the study by Bridget Long, including that "the study measured eligibility for the credits rather than the receipt of tax credits. Measuring eligibility rather the receipt of credits tends to underestimate the effects of credits on attendance because many tax filers who appear to be eligible for the credits do not claim them." See U.S. Government Accountability Office, Student Aid and Postsecondary Tax Preferences: Limited Research Exists on Effectiveness of Tools to Assist Students and Families through Title IV Student Aid and Tax Preferences, GAO-05-684, July 2005, p. 30. |

| 48. |

Nicholas Turner, "The Effect of Tax-Based Federal Student Aid on College Enrollment," National Tax Journal, vol. 64, no. 3 (September 2011), pp. 839-862. |

| 49. |

Specifically, the 2011 study by Turner found that three tax benefits (the Hope Tax Credit, the Lifetime Learning Credit, and the Tuition and Fees Above-the-Line Deduction) "increases full-time enrollment in the first two years of college by about…6.7 percent." This "7 percent enrollment increase implied that 93% of tax-based aid recipients would have enrolled without the tax-based subsidy." See Nicholas Turner, "The Effect of Tax-Based Federal Student Aid on College Enrollment," National Tax Journal, vol. 64, no. 3 (September 2011), pp. 840 and 852. |

| 50. |

George B. Bulman and Caroline M. Hoxby, "The Returns to the Federal Tax Credits for Higher Education," National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 20833 2015, p. 30, http://www.nber.org/papers/w20833.pdf. |

| 51. |

Susan Dynarski and Judith Scott-Clayton, "Tax Benefits for College Attendance," NBER Working Paper No. 22127, March 2016, p. 24. |

| 52. |

According to CBO, "empirical research indicates that tuition levels had little effect on enrollment rates of students from middle and high-income families, but they can affect students from low-income families." Congressional Budget Office, An Economic Analysis of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997, CBO Paper, April 2000, p. 20. |

| 53. |

Taxpayers could, in anticipation of receiving the tax benefit, adjust the amount of tax withheld from their pay. However, there is little evidence that taxpayers do this, likely because it increases the complexity of paying taxes. |

| 54. |

For more information, see Nicholas Turner, "The Effect of Tax-Based Federal Student Aid on College Enrollment," National Tax Journal, vol. 64, no. 3 (September 2011), p. 845; Bridget T, Long, "The Impact of Federal Tax Credits for Higher Education Expenses," National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2004, pp. 104 and 132; and Government Accountability Office, Student Aid and Postsecondary Tax Preferences: Limited Research Exists on Effectiveness of Tools to Assist Students and Families through Title IV Student Aid and Tax Preferences, GAO-05-684, July 2005, p. 30. |

| 55. |

George B. Bulman and Caroline M. Hoxby, "The Returns to the Federal Tax Credits for Higher Education," NBER Working Paper No. 20833, January 2015. |

| 56. |

Government Accountability Office, Student Aid and Postsecondary Tax Preferences: Limited Research Exists on Effectiveness of Tools to Assist Students and Families through Title IV Student Aid and Tax Preferences, GAO-05-684, July 2005, p. 23. |

| 57. |

Government Accountability Office, Student Aid and Postsecondary Tax Preferences: Limited Research Exists on Effectiveness of Tools to Assist Students and Families through Title IV Student Aid and Tax Preferences, GAO-05-684, July 2005, p. 21. |

| 58. |

Nicholas Turner, "The Effect of Tax-Based Federal Student Aid on College Enrollment," National Tax Journal, vol. 64, no. 3 (September 2011), p. 844. In addition, one analysis found that 26% of eligible students did not claim the Hope Credit. See Leonard Burman, Elaine Maag, and Peter Orszag, et al., "The Distributional Consequences of Federal Assistance for Higher Education: The Intersection of Tax and Spending Programs," Tax Policy Center, August 2005, p. 15. |

| 59. |

For more information, see Susan Dynarski and Judith Scott-Clayton, "Tax Benefits for College Attendance," NBER Working Paper No. 22127, March 2016. |

| 60. |

The AOTC subsidizes the first $4,000 of tuition expenses—subsidizing 100% of the first $2,000 in tuition expenses and 25% of the next $2,000 in expenses. For a college that charges less than $2,000, they can increase tuition to $2,000 without increasing the after-tax tuition cost to taxpayers. Increasing tuition above $2,000 would lead students to face higher after-tax tuition costs. |

| 61. |

For more information, see Elaine Maag, David Mundel, and Lois Rice, et al., Subsidizing Higher Education through Tax and Spending Programs, Tax Policy Center, Tax Policy Issues and Options No.18, May 2007. |

| 62. |

See George B. Bulman and Caroline M. Hoxby, "The Returns to the Federal Tax Credits for Higher Education," NBER Working Paper No. 20833, January 2015. |

| 63. |

For example, one study found that increases in Pell Grants increased enrollment by 5.3% for low-income students at low-cost institutions. See Bradley Curs, Larry Singell, and Glen Waddell, "Money for Nothing? The Impact of Changes in the Pell Grant Program on Institutional Revenues and the Placement of Need Students," Education Finance and Policy, vol. 2, no. 3 (2007), p. 231. |

| 64. |

Of note, certain types of technical assistance, like help with filling out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and the assistance of a guidance counselor were found to be more effective at increasing college attendance. Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, Lauren Bauer, and Audrey Breitwieser, Eight Economic Facts on Higher Education, The Hamilton Project, April 2017. |

| 65. |

See Martha J. Bailey and Susan M. Dynarski, "Gains and Gaps: Changing Inequality in the U.S. College Entry and Completion," NBER Working Paper No. 17633, December 2011, http://www.nber.org/papers/w17633. |

| 66. |