The Section 199 Production Activities Deduction: Background and Analysis

In 2004, Congress added the Section 199 domestic production activities deduction to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). The deduction was intended to achieve a number of policy goals, including compensating for repeal of the extraterritorial income (ETI) export-subsidy provisions, supporting the domestic manufacturing sector, and reducing effective corporate tax rates.

Under current law, qualified activities are eligible for a deduction equal to 9% of the lesser of taxable income derived from qualified production activities, or taxable income. Eligible income includes that derived from the production of property that was manufactured, produced, grown, or extracted within the United States. Electricity, natural gas, and potable water production is also eligible, as is film production. Domestic construction projects, as well as engineering and architectural services associated with such projects, also qualify. Certain oil- and gas-related activities also qualify for the deduction, but at a reduced rate of 6%. Overall, more than one-third of corporate taxable income qualifies for the deduction.

In 2013, 66% of corporate claims of the Section 199 deduction were attributable to the manufacturing sector. Another 16% of the value of corporate claims came from the information sector, while 3% were attributable to the mining sector. Other large sectors of the economy, such as finance and insurance, as well as wholesale and retail trade, had few Section 199 claims, relative to their contributions toward economic activity.

In practice, the Section 199 deduction reduces corporate tax rates for certain selected industries. Providing a tax break for certain industries can distort the allocation of capital in the economy, reducing economic efficiency and total economic output. Economic efficiency may be enhanced by repealing the Section 199 deduction and using the additional revenues to offset the cost of reducing corporate tax rates. Repealing the Section 199 deduction could allow for a revenue-neutral corporate tax rate reduction of an estimated 1.4 percentage points.

For companies currently claiming the Section 199 deduction, repeal of the deduction in exchange for a reduced corporate tax rate could lead to increased effective tax rates. Under current law, activities eligible for the deduction receive a tax break equal to 3.15 percentage points. Further, the deduction can currently be claimed by pass-through entities, including S corporations and partnerships. If the Section 199 deduction were repealed for all businesses, but rate cuts were confined to the corporate sector, the result could be higher effective tax rates on pass-through entities. Repealing the Section 199 deduction only for the corporate tax could allow for a revenue-neutral corporate tax rate reduction of an estimated 1.0 percentage points.

Recent tax reform proposals include repeal of the Section 199 deduction as part of base broadening, providing additional revenue to offset the revenue loss associated with rate reduction. Specifically, both the Tax Reform Act of 2014 (H.R. 1) in the 113th Congress and the House Republican “Better Way” tax reform blueprint from 2016 include repeal of the Section 199 deduction.

The Section 199 Production Activities Deduction: Background and Analysis

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Legislative History and Background

- The Deduction: Applying the Deduction to Qualified Activities

- Tax Expenditure Estimates

- Economic Issues

- Economic Efficiency

- Evaluating Economic Efficiency in the Tax Code: The Effective Tax Rate Approach

- Deduction Versus Rate Reduction: Firms' Perspective

- Administrative Complexity

- Distribution of Benefits Across Major Industries

- Policy Options and Concluding Remarks

Figures

- Figure 1. Distribution of Business Assets, Receipts, and Profits Relative to Distribution of Section 199 Deduction

- Figure 2. Oil and Gas Sector Distribution of Business Assets, Receipts, and Profits Relative to Distribution of Section 199 Deduction

- Figure 3. Share of Business Receipts by Sector: Corporate Verses Noncorporate

Summary

In 2004, Congress added the Section 199 domestic production activities deduction to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). The deduction was intended to achieve a number of policy goals, including compensating for repeal of the extraterritorial income (ETI) export-subsidy provisions, supporting the domestic manufacturing sector, and reducing effective corporate tax rates.

Under current law, qualified activities are eligible for a deduction equal to 9% of the lesser of taxable income derived from qualified production activities, or taxable income. Eligible income includes that derived from the production of property that was manufactured, produced, grown, or extracted within the United States. Electricity, natural gas, and potable water production is also eligible, as is film production. Domestic construction projects, as well as engineering and architectural services associated with such projects, also qualify. Certain oil- and gas-related activities also qualify for the deduction, but at a reduced rate of 6%. Overall, more than one-third of corporate taxable income qualifies for the deduction.

In 2013, 66% of corporate claims of the Section 199 deduction were attributable to the manufacturing sector. Another 16% of the value of corporate claims came from the information sector, while 3% were attributable to the mining sector. Other large sectors of the economy, such as finance and insurance, as well as wholesale and retail trade, had few Section 199 claims, relative to their contributions toward economic activity.

In practice, the Section 199 deduction reduces corporate tax rates for certain selected industries. Providing a tax break for certain industries can distort the allocation of capital in the economy, reducing economic efficiency and total economic output. Economic efficiency may be enhanced by repealing the Section 199 deduction and using the additional revenues to offset the cost of reducing corporate tax rates. Repealing the Section 199 deduction could allow for a revenue-neutral corporate tax rate reduction of an estimated 1.4 percentage points.

For companies currently claiming the Section 199 deduction, repeal of the deduction in exchange for a reduced corporate tax rate could lead to increased effective tax rates. Under current law, activities eligible for the deduction receive a tax break equal to 3.15 percentage points. Further, the deduction can currently be claimed by pass-through entities, including S corporations and partnerships. If the Section 199 deduction were repealed for all businesses, but rate cuts were confined to the corporate sector, the result could be higher effective tax rates on pass-through entities. Repealing the Section 199 deduction only for the corporate tax could allow for a revenue-neutral corporate tax rate reduction of an estimated 1.0 percentage points.

Recent tax reform proposals include repeal of the Section 199 deduction as part of base broadening, providing additional revenue to offset the revenue loss associated with rate reduction. Specifically, both the Tax Reform Act of 2014 (H.R. 1) in the 113th Congress and the House Republican "Better Way" tax reform blueprint from 2016 include repeal of the Section 199 deduction.

The Section 199 domestic production activities deduction reduces tax rates on certain types of activities, primarily domestic manufacturing activities.1 While a policy objective of the provision was to reduce taxes for domestic manufacturing, in practice, a number of firms in other industries benefit. Many economists and policymakers believe that corporate tax reform could result in a tax code with a broader base and lower rates that could promote economic activity and growth. Arguably, provisions such as the Section 199 deduction that favor certain economic sectors may be inconsistent with this broad-base, low-rate objective.

The Section 199 deduction was enacted in 2004 to address a number of policy concerns. In part, the deduction was designed to compensate for the repeal of the extraterritorial income (ETI) provision that had been found to be a prohibited export subsidy by the World Trade Organization (WTO). The deduction was also designed to support the domestic manufacturing sector and reduce effective corporate tax rates. As adopted, the definition of eligible domestic production activities extends beyond the manufacturing sector, reducing effective tax rates across a number of economic sectors.

From an economic perspective, providing a deduction for selected domestic manufacturing activities is less efficient than an across-the-board cut in tax rates. By allowing only certain sectors to qualify for this deduction, the tax code creates an added incentive for capital investment in activities that would have produced lower pretax rates of return. This incentive distorts the allocation of capital. Targeted tax incentives may be inefficient, as they can drive capital away from its most productive use, reducing overall economic output. Such efficiency concerns are central to economic arguments in support of a broader tax base, with lower tax rates.

Repeal of the Section 199 production activities deduction has been included in recent tax reform proposals. In 2010, both the Fiscal Commission and the Debt Reduction Task Force recommended eliminating Section 199, along with most other corporate tax expenditures, in exchange for a reduced corporate tax rate.2 The Tax Reform Act of 2014 (H.R. 1) introduced in the 113th Congress also proposed eliminating various corporate tax expenditures as part of corporate tax reform that would result in lower tax rates.3 The House Republican "Better Way" blueprint released in June 2016 during the 114th Congress proposed eliminating Section 199 and most other tax expenditures while lowering the corporate tax rate to 20%.4 As Congress looks at options for reducing the corporate tax rate, possibly such that the reduction is revenue-neutral, eliminating the production activities deduction might be considered. Eliminating the deduction would allow for approximately a 1.4 percentage point reduction in the corporate tax rate.

A targeted repeal or reform of the Section 199 deduction has also been considered. One common theme is to evaluate the eligibility of certain types of activities, notably those related to oil and gas. Already, the deduction for oil and gas is limited. Since 2007, Congress has voted numerous times on measures that would limit or repeal the Section 199 deduction for oil- and gas-related activities. However, in 2015, Congress passed legislation expanding the Section 199 deduction for certain domestic oil refineries.

Currently, Section 199 allows a deduction equal to 9% of taxable income derived from qualified production activities. Qualified production activities are defined to include manufacturing, mining, electricity and water production, film production, and domestic construction. For oil- and gas-related activities, the deduction is permanently limited to 6%. Across all sectors, the deduction cannot exceed 50% of W-2 wages paid by the taxpayer for qualifying activities.

This report provides a legislative history of the Section 199 deduction, details on how the deduction works in practice, an economic evaluation of the deduction, and analysis of the various economic sectors benefitting from the provision. A number of policy options related to the Section 199 deduction conclude this report.

Legislative History and Background

The Section 199 domestic production activities deduction was added to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) as part of the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 (AJCA; P.L. 108-357). The Section 199 deduction was designed, in part, to replace an incentive that had been found to be a prohibited export subsidy by the WTO.5

From 1971 through 2000, the United States attempted to promote exports through a variety of tax benefits that were found to violate export-subsidy agreements under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and later the WTO.6 The ETI provisions were the last in this series of export-related tax benefits.7 The ETI provisions exempted certain export income and a limited amount of income from foreign operations from U.S. tax.

|

A Brief History of U.S. Export Subsidies In 1971, the Domestic International Sales Corporation (DISC) provisions were enacted as part of a broader economic package designed to address a number of perceived economic problems, including a deteriorating balance of payments.8 DISC was originally proposed during an era of fixed exchange rates, as a policy option for improving the balance of payments, among other goals. The DISC provisions created an incentive for U.S. multinationals to produce domestically for export, rather than locating production abroad. The provisions allowed U.S.-based manufacturing firms to set up a DISC subsidiary, through which it sold exports. Export income could then be allocated to this DISC. DISCs as entities were tax-exempt. Income allocated to the DISC could be deferred and would not be subject to tax until it was remitted to the U.S. parent corporation. In effect, the DISC provisions allowed firms to indefinitely defer taxes on an estimated 16% to 33% of their export income.9 Several European countries objected to the DISC provisions, complaining that they constituted a prohibited export subsidy under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT, predecessor to the WTO). In 1984, the United States replaced the DISC provisions with Foreign Sales Corporation (FSC) provisions, in an attempt to achieve GATT legality. FSCs were similar to DISCs, in that both allowed exporters to obtain tax benefits by selling exports through tax-preferred subsidiary corporations. In contrast to DISCs, FSCs were not allowed to be located in the United States, and were required to conduct certain management activities abroad. Under the FSC provisions, the total tax exemption was an estimated 15% to 30% of export income, slightly less that what had been available under DISC.10 Ultimately, the FSC provisions were found to violate export-subsidy obligations under the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures. In 2000, Congress moved to repeal FSC, establishing the ETI provisions as a replacement.11 The ETI provisions attempted to address WTO-legality concerns by providing a tax benefit that included exports, but was not "export contingent." The ETI provisions exempted extraterritorial income from U.S. tax. Extraterritorial income was defined to provide an exemption for certain export income and a limited amount of income from foreign operations. Despite the attempt to make the ETI provisions not export contingent, the WTO still found that the ETI provisions were, in practice, an export subsidy. Congress moved to phase out the ETI provisions under AJCA and ultimately repealed the transition rules, fully eliminating the ETI provisions, as part of the Tax Increase Prevention and Reconciliation Act of 2005 (TIPRA; P.L. 109-222). |

There were other policy motivations behind the Section 199 deduction, in addition to compensating for ETI repeal. Congress noted that the Section 199 deduction helped reduce U.S. corporate tax rates, address challenges imposed on the manufacturing sector during the economic slowdown of the early 2000s, and promote international competitiveness.12

As enacted, the estimated revenue loss over 10 years associated with enactment of the deduction was more than 1.5 times the revenues gained from repealing ETI.13 Over the 2005 through 2014 budget window, repeal of the ETI provisions was estimated to generate $49.2 billion in additional revenues. Over the same time period, revenue losses associated with enactment of Section 199 were estimated at $76.5 billion, for a net revenue loss of $27.3 billion.

Since being enacted in 2004, the Section 199 deduction has undergone a number of minor modifications. TIPRA clarified that wages for the purpose of the deduction limit were those relating to domestic production activities. The Tax Relief and Healthcare Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-432) added the benefit for Puerto Rico, on a temporary basis. The temporary provisions allowing the deduction for qualifying activities in Puerto Rico have subsequently been extended as part of "tax extenders."14

Additional changes were made to the Section 199 deduction as part of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (EESA; P.L. 110-343). Under EESA, oil-related qualifying production activities, including but not limited to oil and gas extraction, were limited to a 6% deduction for tax years starting after 2009.

The Section 199 deduction was also modified under EESA to take into consideration domestic film industry operations.15 Specifically, W-2 wage limitation restrictions were modified for the film industry, as was the application of the Section 199 deduction to partnerships and S corporations in the film industry.

The Section 199 deduction was enhanced for crude oil refiners that are not a major integrated oil company as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113). Specifically, the provision limited the amount of transportation costs to be taken into account when determining taxable income for the purposes of the Section 199 deduction to 25%. The result is higher income for the purposes of calculating the deduction, and thus a larger deduction. This provision was enacted on a temporary basis to provide support for independent refiners following changes in crude oil export policy, and is set to expire at the end of 2021.16

The Deduction: Applying the Deduction to Qualified Activities

The production activities deduction allows taxpayers a deduction based on the lesser of taxable income derived from qualified production activities (qualified production activity income; QPAI) or taxable income.17 A taxpayer's QPAI is equal to the taxpayer's domestic production gross receipts (DPGR), reduced by (1) the cost of goods sold that is allocable to those receipts; and (2) other deductions, expenses, and losses that are properly allocable to those receipts.

Eligible income includes that derived from production property that was manufactured, produced, grown, or extracted within the United States. Electricity, natural gas, and potable water production is also eligible. As noted above, film production also qualifies. Construction performed within the United States may also qualify for the deduction, as can engineering and architectural services associated with domestic construction projects. In 2012, more than one-third of corporate taxable income was eligible for the Section 199 deduction.18

The Section 199 production activities deduction, as enacted in 2004, was phased in such that the full deduction rate of 9% was reached starting in 2010. During 2005 and 2006, eligible taxpayers could claim a tax deduction equal to 3% of the lesser of taxable income or QPAI. For tax years 2007, 2008, and 2009 the deduction rate was 6%.

When Section 199 was added to the code in 2004, the Treasury was granted broad authority to prescribe regulations necessary to carry out the purposes of the legislation. The Treasury defined qualified activities that were "manufactured, produced, grown, or extracted" to include minerals mining and refining activities.19 Oil refining is explicitly used as an example in the Treasury regulations as a qualified activity.20 The Treasury regulations also clarified that construction activities related to drilling of oil and gas wells were qualified activities for the Section 199 deduction.

The deduction is permanently limited to 6% for oil-related qualified production activities.21 For the purposes of limiting the Section 199 deduction, EESA defined oil-related production activities as being related to the production, refining, processing, transportation, or distribution of oil, gas, or any primary product thereof. A primary product from oil includes crude oil, and all products derived from the destructive distillation of crude oil, such as motor fuel.

The deduction cannot exceed 50% of the W-2 wages paid by the taxpayer during the year. The wage limitation effectively prevents sole proprietorships without employees from claiming the credit. Only wages allocable to qualifying domestic production activities qualify. Limiting the deduction according to wages paid for qualifying domestic production activities helps ensure that taxpayers claiming the deduction are paying wages to domestic employees.

The Section 199 production activities deduction serves to reduce the effective tax rate—the actual rate of taxes paid relative to income—on qualified activities. Generally, tax liability is calculated as follows:

Taxes = [(Income – Expenses)(1 – p) × t] – Tax Credits,

where t is the statutory tax rate and p is the production activities deduction rate. For income that does not qualify for the production activities deduction, p is zero.

For businesses, the primary component of income is revenues from the sale of goods and services. Other income sources include investment income, royalties, rents, and capital gains.

Once income has been determined, expenses allowed by the tax code are deducted.22 Businesses can deduct expenses, including salaries and wages, purchased materials and inputs, advertising costs, charitable contributions, insurance premiums, legal fees, and various other items.23 Interest payments are also deductible, as are deductions for depreciation allowances.24 Theoretically, taxes are levied on profits, rather than gross income.

When the production activities deduction applies, the tax rate is the statutory tax rate (generally, 35%) multiplied by (1-p).25 For example, when p = 0.09, the effective tax rate becomes 31.85% (35% × 0.91). When p = 0.06, as is currently the case for the oil- and gas-related activities, the effective tax rate becomes 32.9% (35% × 0.94).

|

Calculating the Domestic Production Activities Deduction: Examples The following examples illustrate hypothetical calculations of the Section 199 production activities deduction. Company 1 Company 1 is a manufacturing corporation operating exclusively within the United States. In 2010, Company 1's activities generated $1 million in QPAI. During 2010, Company 1 paid W-2 wages of $500,000. Company 1 also had a net operation loss (NOL) carry forward of $300,000. Since Company 1 had a NOL carry forward, taxable income was less than QPAI (taxable income in this case is assumed to be $1 million less the $300,000 NOL carry forward, or $700,000). Applying the 9% deduction rate, Company 1's deduction is $63,000. Since W-2 wages were $500,000 in 2010, Company 1's deduction was not reduced by the wage limitation. Assuming a corporate tax rate of 35%, this $63,000 deduction reduces Company 1's tax liability by $22,050. Company 2 Company 2 is a manufacturing company with operations in the United States and abroad. Company 2 generated a total of $1 million in production activities income. One-half of that income, or $500,000, was generated in the United States. Company 2 paid $250,000 in W-2 wages to U.S. workers for domestic production activities. Applying the 9% deduction rate to Company 2's domestic production activities income, Company 2's deduction is $45,000. Company 2's deduction was not reduced by the wage limitation. If Company 2 had earned all of its manufacturing income in the United States, the deduction would have been twice as large. Assuming a corporate tax rate of 35%, this $45,000 deduction reduces Company 2's tax liability by $15,750. Company 3 Company 3 is a U.S. firm engaged in oil-related qualified production activities. For 2010, Company 3's activities generated $500,000 in oil-related QPAI. During 2010, Company 3 paid W-2 wages of $50,000. Since Company 3's QPAI is from oil-related activities, Company 3's deduction rate is limited to 6%. The 50% of W-2 wages limitation limits Company 3's Section 199 deduction to $25,000 (50% of Company 3's $50,000 W-2 wages paid). In the absence of the W-2 wage limitation, Company 3's deduction would have been $30,000 (6% of $500,000 in QPAI). Assuming a corporate tax rate of 35%, this $25,000 deduction reduces Company 3's tax liability by $8,750. |

Tax Expenditure Estimates

During 2016, the production activities deduction is expected to have resulted in $20.0 billion in foregone federal revenues ($14.5 billion for corporations, $5.5 billion for individuals) (see Table 1).

|

Deduction Rate |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

3% |

6% |

9%a |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Noncorporate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), Tax Expenditure Estimates, various editions, available at http://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=select&id=5.

Notes: Annual tax expenditure estimates are projections, and reflect estimated rather than actual federal revenue losses.

a. For years after 2009, oil- and gas-related activities are limited to a 6% deduction.

Estimated revenue losses have steadily increased since the provision was first enacted in 2005. Large increases were observed in years when the deduction rate increased. By 2010, the deduction was fully phased in, set at 9% for qualified domestic manufacturing activities (or 6% for oil- and gas-related activities). Since 2010, the tax expenditure estimate associated with the provision has doubled. This increase could reflect both (1) an increase in qualifying activities, and (2) an increase in firms' ability to benefit from the incentive. The Great Recession and associated corporate losses in 2010 likely prevented firms from claiming the deduction in the 2010 tax year, as well as future tax years, to the extent that losses were carried forward.

Between 2016 and 2020, JCT estimates suggest that approximately 72% of the revenue losses resulting from the Section 199 deduction will be attributable to the corporate sector. The remaining revenue losses stem from deductions taken by S corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships.26 When the Section 199 deduction was enacted in 2004, JCT estimated that in 2005, 75% of the associated revenue losses would be attributable to C corporations, 12% associated with S corporations and cooperatives, 9% with partnerships, and 4% with sole proprietorships.27

All else being equal, repealing the deduction would generate additional revenues. These revenues could be used to offset the cost of a tax rate reduction. Eliminating the deduction for all businesses would generate enough additional revenue to offset the cost of approximately a 1.4 percentage point reduction in the corporate tax rate.28 If the deduction were eliminated for corporations only, it could offset the cost associated with approximately a 1.0-percentage-point corporate rate reduction.

Economic Issues

A tax code that is economically efficient is an often cited goal of tax reform. For economists, when resources are put to their best use, economic efficiency is maximized. The following sections outline the concepts of economic efficiency and discuss the Section 199 deduction in this framework.

Economic Efficiency29

Economic efficiency is maximized when resources (capital and labor) are employed in their most productive use. When economic efficiency is maximized, so too is economic output. In a well-functioning free market, the return to various investments should adjust to ensure capital is allocated efficiently. When the return to an investment in one sector of the economy is higher than the return in another, this differential sends a signal that capital is valued more highly in that first sector. Capital will tend to flow out of the low-return sector into the higher-return sector, until the returns to capital across sectors are equalized.

Tax policy can be used to enhance economic efficiency when markets fail to direct resources to their most productive uses.30 Alternatively, tax policy can also reduce economic efficiency. When taxpayers respond to tax incentives and distort resource allocation, economic output may not be maximized, as resources are not directed to their most productive uses.

The Section 199 production activities deduction increases the after-tax return to particular investments by lowering the effective tax rate in certain industries, and thus may distort the allocation of capital. This effect could reduce economic efficiency and total economic output by directing capital away from its most productive use. A 2017 Treasury report on business tax reform noted that "[t]he domestic production activities deduction is difficult to justify without clear evidence that it provides offsetting social benefits of some kind. Without such a social benefit, then to the extent that it is targeted to particular industries or activities it could inefficiently encourage such activities over others that do not benefit."31

Part of the policy rationale behind adopting the Section 199 deduction was to provide support to the manufacturing sector.32 Specifically, there were concerns regarding the impact of competition from foreign producers on U.S. manufacturers.33 In practice, however, the decline in manufacturing employment since 2000 can also be explained by increases in productivity.34 Increased productivity is generally associated with strong economic growth. If increased productivity is the reason behind declines in manufacturing sector employment, tax policies designed to promote manufacturing employment could reduce economic efficiency, as such tax policies are not correcting for a market failure. That said, the manufacturing sector continues to be important for innovation and export growth, policy objectives that support having targeted tax benefits for manufacturing.35

The Section 199 deduction could serve to counter other economic inefficiencies created by the tax code. The tax-favored status of investments financed using debt rather than equity may lead to various economic distortions.36 The Section 199 deduction, by reducing tax rates in the corporate sector, may help reduce debt-equity distortions. These distortions could also be reduced, however, through reduced corporate tax rates for all sectors, rather than reduced rates provided through a deduction that is only available to certain economic sectors. These distortions could also be reduced by eliminating the preference for debt over equity in the tax code.37

Evaluating Economic Efficiency in the Tax Code: The Effective Tax Rate Approach

As discussed above, the Section 199 production activities deduction likely contributes to economic distortions by promoting capital investment in selected industries and activities. One method for evaluating tax-induced economic distortions is to use an effective tax rate approach. Mathematically, an effective tax rate is the before-tax return to capital less the after-tax return to capital, divided by the before-tax return to capital.

In other words, the effective tax rate is the taxation-induced percentage increase in the pretax return to capital. The lower the effective tax rate, the more a specific type of investment is preferred in the tax code. Effective tax rates can be negative, if firms have an incentive to invest more when taxed than in the absence of taxes. Overall, the larger the difference between the before- and after-tax returns to capital, the greater the potential for loss in economic efficiency.

Effective tax rates are influenced by many different provisions in the tax code. As discussed above, a 9% production activities deduction reduces the corporate effective tax rate on qualifying activities from 35% to 31.85%. Varying depreciation rules also lead to differences in effective tax rates across sectors.38 While a full analysis of effective tax rates is beyond the scope of this report, it is important to note that the Section 199 deduction can create even further distortions in sectors already potentially benefitting from favorable depreciation schedules or various other tax incentives. Moving toward a more neutral taxation of businesses will require consideration and evaluation of the wide array of tax-induced distortions, which often cannot be fully evaluated in isolation.

Deduction Versus Rate Reduction: Firms' Perspective

There are several reasons why the Section 199 production activities deduction may have been structured as a targeted deduction, rather than an across-the-board rate reduction. While an across-the-board rate reduction may have been a more economically efficient alternative, certain firms may have had various reasons for preferring the deduction as opposed to reduced rates. Industries eligible for the Section 199 deduction might prefer the deduction to a revenue-neutral rate cut available to all industries, since the benefit of the deduction is larger for eligible industries.

Noncorporate entities also benefit from having Section 199 structured as a deduction rather than having a cut in the corporate tax rate. Noncorporate entities paying taxes in the individual income tax system as pass-through entities are able to benefit from a deduction, while they would not benefit from a corporate rate cut.39

Administrative Complexity

The Section 199 deduction and the associated regulations have increased complexity in the tax code. Both taxpayers and the government face an added administrative burden. To claim the deduction, taxpayers must allocate costs and jobs devoted to activities performed in the United States to determine both receipts associated with the qualified activities and associated costs. The complexity associated with determining what qualifies for the deduction may increase the record-keeping and accounting burden on firms. The largely fixed-cost nature of these burdens would likely favor larger firms over smaller firms, potentially driving average firm size above the productivity-maximizing level.40 Further, given that production activities are tax favored, firms have an incentive to shift profits among divisions, and characterize income as being related to domestic production activities, where possible.41 This incentive may stress limited enforcement resources for the IRS. To the extent that Section 199 deduction claims are a point of contention, IRS enforcement efforts are allocated here rather than to other areas of the code.

Distribution of Benefits Across Major Industries

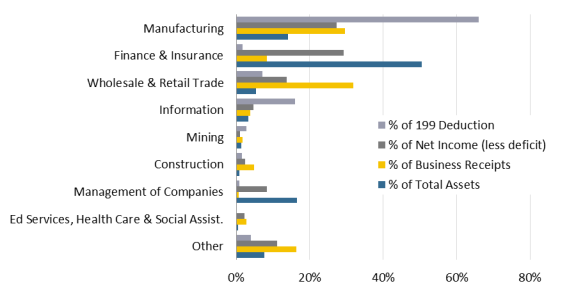

As was noted above, one policy rationale for the Section 199 deduction was to support the domestic manufacturing sector. In practice, the majority of the benefits received by corporations go to those involved in manufacturing (66% in 2013; see Figure 1).42 A number of industries with primary designations other than manufacturing also benefit from the Section 199 deduction.

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of Section 199 claims made by corporations across industrial sectors, relative to the distribution of total corporate assets, total corporate business receipts, and total corporate profits (net income less deficit) for 2013.43,44 As noted above, in 2013, 66% of corporate claims of the Section 199 deduction were made by firms in the manufacturing sector. As expected, the share of manufacturing claims of the Section 199 deduction is high relative to the size of the manufacturing sector. The manufacturing sector is responsible for generating 27% of corporate profits and 30% of corporate receipts, and holds 14% of corporate assets.45

The information sector's and the mining sector's shares of Section 199 claims also exceed their respective shares of corporate profits, corporate receipts, and corporate assets.46 Nearly 16% of corporate Section 199 deductions are claimed by firms in the information sector, while this sector is responsible for 5% of corporate profits, 4% of corporate receipts, and 3% of corporate assets. The mining sector claims 3% of corporate Section 199 deductions, while earning 1% of corporate profits and less than 2% of corporate receipts, and holding 1% of corporate assets.

Finance and insurance, and other service-oriented sectors such as educational services, health care, and social assistance, receive little benefit from the Section 199 deduction. While the finance and insurance sector earned 29% of corporate profits and 8% of corporate receipts, and held 51% of corporate assets in 2013, the sector's share of Section 199 deduction claims was less than 2%. Corporate claims of the Section 199 deduction were also small for the education services, health care, and social assistance sectors. The corporate sector of these industries, as measured by profits, receipts, and total assets, is also relatively small.

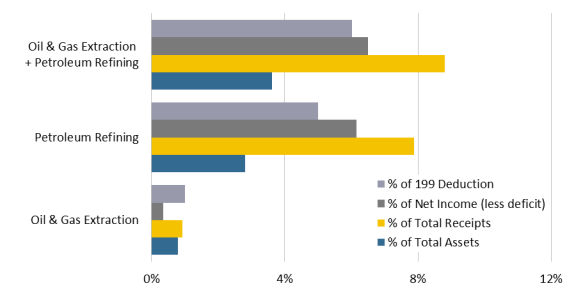

In past Congresses, there has been legislative activity related to the Section 199 deduction and the oil and gas sector.47 The IRS SOI data can be used to provide some insight into oil and gas sector Section 199 deduction claims. Deduction claims in the sector, however, may vary over time, as income tends to fluctuate with oil prices. While the industry data do not explicitly identify oil- and gas-related activities qualifying for the Section 199 deduction, much of this activity is likely captured in the data for the oil and gas extraction and the petroleum refineries (including integrated) sectors. Note that the oil and gas sector is restricted to the 6% reduced rate.

Of the $33.9 billion in Section 199 deductions claimed in 2013 by C corporations, 1% was claimed by firms classified as being in the oil and gas extracting sector (see Figure 2).48 Another 5% was claimed by petroleum refineries (including integrated petroleum refineries).49 In the manufacturing and mining sectors as a whole, the share of Section 199 deductions being claimed by the sector exceeded the share of net income (less deficit), or corporate profits, attributable to the sector. The same is not true for subsectors of oil and gas extraction and petroleum refining. The share of profits attributable to these sectors is roughly the same as the share of Section 199 deductions being claimed by these sectors. The two sectors combined reported approximately 6% of corporate profits, while also claiming roughly 6% of Section 199 deductions. As was the case with the manufacturing and mining sectors generally, the share of Section 199 deductions attributable to the oil and gas extracting and petroleum refining sectors is greater than the sector's respective shares of corporate assets. However, the petroleum refining sector's share of business receipts exceeds its share of Section 199 deductions (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

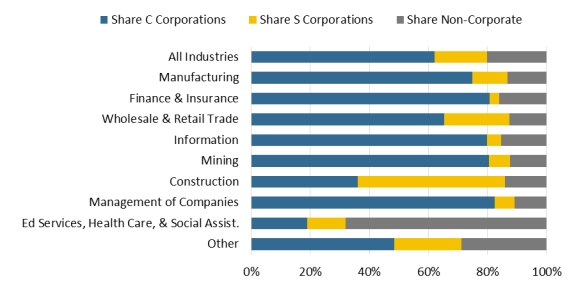

The analysis of the distribution of Section 199 claims across industries has, so far, focused on the corporate sector. But, some of the benefits of the Section 199 deduction flow through S corporations or partnerships and are claimed on individuals' income tax returns. In 2016, an estimated 73% of the revenue loss associated with the production activities deduction was attributable to the corporate sector, with the remainder claimed by pass-through businesses on individual income tax returns (Table 1 above).

There is variation across industries in the amount of economic activity that takes place in the corporate sector. Data from the 2012 Economic Census can be used to identify receipts received by C corporations, S corporations, and other business types, by industrial sector. Across all industrial sectors, 66% of business receipts are received by C corporations.50 Relative to other industries, economic activity in the manufacturing sector tends to be concentrated among C corporations. Roughly 75% of manufacturing business receipts were earned by C corporations in 2012. The finance and insurance, information, mining, and management of companies sectors also tend to have business receipts concentrated in C corporations.

Not all industrial sectors that tend to benefit from the Section 199 deduction have economic activity concentrated in C corporations. Benefits from the Section 199 deduction to sectors that tend to have a higher proportion of business activity in S corporations or the noncorporate sector are not reflected in the SOI data in Figure 1. In the construction sector, for example, 36% (see Figure 3) of business receipts are earned by C corporations. Most of the taxable income and tax benefits for this sector flow through to individuals. This share can have potentially important implications for tax reform. For example, if the Section 199 deduction is repealed in exchange for a revenue-neutral lower corporate tax rate, the construction sector stands to potentially lose relative to other sectors. All businesses in the construction sector that were previously eligible for the Section 199 deduction would see their effective corporate tax rates rise. If the revenues generated from repealing the Section 199 deduction are used only to reduce tax rates for C corporations, a large portion of activity in the construction sector would not benefit from the rate reduction.51

Policy Options and Concluding Remarks

Repeal of the Section 199 deduction has been considered as part of some comprehensive tax reform packages.52 Broadening the tax base by repealing the Section 199 deduction, using the revenue generated to reduce tax rates, would remove an existing distortion in the tax system and could enhance economic efficiency. The Tax Reform Act of 2014 (H.R. 1, 113th Congress) proposed repealing the Section 199 deduction for all activities.53 The deduction would have been phased out over a two-year period, being reduced to 6% in the first year, and 3% in the second year, before being repealed. The House Republican 2016 "Better Way" Tax Reform Blueprint also proposed to repeal Section 199 as part of a comprehensive tax reform that would repeal tax expenditures and lower tax rates. The Blueprint expresses concern for how provisions in the tax code that favor specific activities may slow economic growth, add complexity, and contribute to perceptions of unfairness. It argues, "section 199 is highly complex, often frustrating both those businesses that fail to qualify as well as businesses that do qualify but only after navigating a substantial paperwork burden. By cutting the corporate rate to 20 percent, and by cutting the top rate on the active business income of pass-through entities to 25 percent, the Blueprint makes section 199 unnecessary."54

Repealing the Section 199 deduction is not without trade-offs. In isolation, repealing the Section 199 deduction and providing a revenue-neutral reduction in tax rates could increase the effective tax rates of taxpayers previously qualifying for the deduction. In addition, if the deduction is repealed for all businesses, but the revenues are used only to reduce corporate tax rates, the effective tax rate on pass-through entities could increase. The issues raised by these trade-offs, however, may be addressed with other changes included in a broader tax reform proposal.

Another policy option related to the Section 199 deduction would be to modify the deduction to address economic efficiency concerns. One way this could be achieved would be to allow the deduction for activities that tend to be associated with positive externalities, or tend to generate external benefits that are not reflected in market prices, and are therefore underprovided by the market. The Obama Administration's 2016 "Framework for Business Tax Reform" included a proposal to increase the Section 199 deduction, but to focus the deduction more on manufacturing activity.55 The result would be a lower effective tax rate for the manufacturing sector.

Others have proposed increasing the Section 199 deduction for research and development (R&D) activities.56 If policymakers are looking to focus the Section 199 deduction on certain activities, R&D is often believed to generate positive externalities, for which firms are not compensated and which are therefore underprovided in the market. It is not clear, however, that an added deduction for R&D would enhance efficiency if enacted alongside current tax incentives for R&D, or address many of the policy concerns with the currently available incentives for R&D.57 Furthermore, it remains possible that the deduction could continue to distort economic activity if it remains available for activities that do not generate positive external effects.

The Section 199 deduction could also be modified to address concerns over cross-border capital flows. If one purpose of the deduction is to reduce U.S. corporate tax rates for the purpose of attracting capital, limiting the deduction to industries where cross-border capital flows are more likely to occur could help achieve this objective. For example, if capital in the corporate manufacturing sector is more likely to flow abroad than capital in the noncorporate sector, or capital in the mining and construction sectors, limiting the deduction to those in the corporate manufacturing sector could serve to attract mobile capital into the United States. Limiting the deduction would reduce revenue losses associated with the deduction.

Repealing the Section 199 deduction for certain sectors, such as the fossil fuel sector, may help eliminate tax-induced distortions that might lead to overinvestment in those sectors while generating additional revenues. For example, the Obama Administration's FY2017 budget proposed to repeal the Section 199 deduction for fossil-fuels-related activities. This proposal was part of a broader objective to "phase out subsidies for fossil fuels" that encouraged "more investment in the fossil fuels sector than would occur under a neutral system."58 Repealing the deduction for certain sectors, or for certain types of firms, does not, however, address the remaining distortions. Even if the Section 199 deduction were repealed for the fossil fuel sector, the deduction would continue to create economic distortions by continuing to promote investment in other targeted activities.

Finally, part of the intent of the Section 199 deduction was to support the domestic manufacturing sector. While economists sometimes question whether there is an economic rationale for supporting the domestic manufacturing sector, there may be other policy motivations for writing tax policies that favor domestic manufacturing. Should Congress decide to reevaluate the current tax treatment of the U.S. manufacturing sector, the impact of the myriad of incentives benefitting the sector, including depreciation schedules and expensing allowances, investment tax policies, incentives for R&D, and the potential interactions of such policies, may be considered.

Appendix. Legislative Efforts to Modify the Section 199 Deduction for Oil and Gas

Following legislation enacted in the 110th Congress, the Section 199 deduction is limited to 6% for oil- and gas-related activities. At various times, Congress has considered other measures to modify or repeal the Section 199 deduction for the oil and gas sector, as discussed in this appendix.

110th Congress

Early in the 110th Congress, the "Energy Independence Day" initiative (H.R. 3221) was announced, which included several energy-related bills. The energy tax bill, the Renewable Energy and Energy Conservation Tax Act of (H.R. 2776), contained a provision that would have repealed the Section 199 deduction for oil and gas. The Senate Finance Committee-approved energy tax package would have prevented major integrated oil companies from claiming the Section 199 deduction. However, the Senate failed to invoke cloture on the broader package of energy bills when the tax title was included. Ultimately, the Senate-passed version of the comprehensive energy legislation (H.R. 6) did not include a repeal of the Section 199 deduction for oil and gas.59 The compromise energy bill that was ultimately signed into law on December 19, 2007, the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-140), did not modify the Section 199 deduction for oil and gas.

Legislative efforts to repeal the Section 199 deduction for oil and gas continued in 2008. The Comprehensive American Energy Security and Consumer Protection Act (H.R. 6899) proposed to repeal the Section 199 deduction for major integrated oil companies, and to restrict the deduction to 6% for oil- and gas-related activities.60 The legislation also sought to repeal the deduction for state-owned oil companies.61 Legislation containing this provision was approved by the House on September 16, 2008. Similar legislation was offered in the Senate (S. 3478). Ultimately, provisions limiting the Section 199 deduction to 6% for oil-related activities were approved by the Senate as part of a package combining financial sector rescue with tax extenders.62 A limitation of the Section 199 production activities deduction for oil-related activities was signed into law as part of the Energy Tax Title in the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act (EESA; P.L. 110-343).

111th Congress

During the 111th Congress, the Senate considered measures that would have repealed the Section 199 deduction for oil and gas. S.Amdt. 4318 to the American Jobs and Closing Tax Loopholes Act (H.R. 4213) would have repealed the Section 199 deduction for oil and gas. This measure was defeated on June 15, 2010. During 2010, the Senate also voted on a measure that would have eliminated the Section 199 deduction for major integrated oil companies, as part of an amendment to provide exemptions from the 1099 information reporting requirements (S.Amdt. 4595 to H.R. 5297).63 The amendment was withdrawn on September 15, 2010, after cloture was not invoked.

112th Congress

Early in the 112th Congress, legislation seeking to repeal, among other oil- and gas-related tax provisions, the Section 199 deduction for oil and gas was again considered. Specifically, the Close Big Oil Tax Loopholes Act (S. 940) would have repealed the Section 199 deduction, and other oil- and gas-related tax provisions, for major integrated oil companies. On May 17, 2011, the Senate did not invoke cloture on S. 940.

113th Congress

The 113th Congress did not vote on any measures to modify the Section 199 deduction for the oil and gas sector.

114th Congress

The Section 199 deduction was modified in late 2015 as part of an effort to address concerns that some U.S. refiners would be disadvantaged should there be a change in crude export policy.64 A temporary provision increasing the Section 199 tax benefit for independent oil refiners was signed into law as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 114-113).65

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Benjamin G. Stutts, intern, made valuable contributions in updating this product. Jamie Hutchinson, Visual Information Specialist, provided graphics support.

Footnotes

| 1. |

Section 199 refers to the deduction's section in the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). |

| 2. |

The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (Fiscal Commission or Simpson-Bowles) was created by executive order in 2010. The Debt Reduction Task Force (or Domenici-Rivlin) was a bipartisan task force housed at the Bipartisan Policy Center. For additional information on tax policy options for deficit reduction, see CRS Report R41641, Reducing the Budget Deficit: Tax Policy Options, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 3. |

For additional information, see CRS Report R44771, An Overview of Recent Tax Reform Proposals, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 4. |

House Republican Tax Reform Task Force Blueprint, A Better Way: Our Vision for a Confident America: Tax, June 2016, http://abetterway.speaker.gov/_assets/pdf/ABetterWay-Tax-PolicyPaper.pdf. For an analysis of this proposal, see CRS Report R44823, The "Better Way" House Tax Plan: An Economic Analysis, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 5. |

The conference report on AJCA noted that AJCA was "crafted to repeal an export benefit that was deemed inconsistent with obligations of the United State under the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures and other international trade agreements." The report went on to state that the AJCA "replaces" export tax relief with a reduced tax rate for U.S.-based manufacturers. See U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, American Jobs Creation Act of 2004, Conference Report to Accompany H.R. 4520, 108th Cong., 2nd sess., October 7, 2004, H.Rept. 108-755, p. 275. |

| 6. |

There are other provisions in the tax code that may be viewed as export subsidies. For example, the tax code's rules governing the source of inventory sales serve to increase the after-tax return on investment in exporting (i.e., subsidize exports). The so-called "title passage" rule effectively allows companies to source their inventory sales abroad. For more information, see U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Budget, Tax Expenditures: Compendium of Background Material on Individual Provisions, committee print, prepared by Congressional Research Service, 114th Cong., December 2016, S. Prt. 114-31, pp. 57-60. |

| 7. |

For a concise history of U.S. export tax subsidies, see the text box, "A Brief History of U.S. Export Subsidies." A more complete history of export-related tax benefits can be found in CRS Report RL31660, A History of the Extraterritorial Income (ETI) and Foreign Sales Corporation (FSC) Export Tax-Benefit Controversy. |

| 8. |

See the Revenue Act of 1971 (P.L. 92-178). The DISC provisions went into effect on January 1, 1972. |

| 9. |

See CRS Report RL31660, A History of the Extraterritorial Income (ETI) and Foreign Sales Corporation (FSC) Export Tax-Benefit Controversy. |

| 10. |

See CRS Report RL31660, A History of the Extraterritorial Income (ETI) and Foreign Sales Corporation (FSC) Export Tax-Benefit Controversy. |

| 11. |

See the FSC Repeal and Extraterritorial Income Exclusion Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-519). |

| 12. |

See U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, American Jobs Creation Act of 2004, Conference Report to Accompany H.R. 4520, 108th Cong., 2nd sess., October 7, 2004, H.Rept. 108-755, p. 275. |

| 13. |

See U.S. Congress, Joint Committee on Taxation, General Explanation of Tax Legislation Enacted in the 108th Congress, committee print, 108th Cong., May 2005, JCS-5-05, p. 546. |

| 14. |

CRS Report R44677, Tax Provisions Expiring in 2016 ("Tax Extenders"), by [author name scrubbed]. The Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-312) extended the benefits for Puerto Rico through 2011. The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-240) extended the benefits for Puerto Rico through 2013. The Tax Increase Prevention Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-295) extended the benefits for Puerto Rico through 2014. The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes ("PATH") Act of 2015 (Division Q of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016; P.L. 114-113) extended the benefits for Puerto Rico through 2016. |

| 15. |

Congress believed domestic film production to be important to the U.S. economy. See U.S. Congress, Joint Committee on Taxation, General Explanation of Tax Legislation Enacted in the 110th Congress, committee print, 110th Cong., March 2009, JCS-1-09, pp. 447-449. |

| 16. |

See CRS Report R44403, Crude Oil Exports and Related Provisions in P.L. 114-113: In Brief, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 17. |

For individual taxpayers, the deduction is limited to the lesser of QPAI or adjusted gross income (AGI). |

| 18. |

Rebecca Lester and Ralph Rector, "What Companies Use the Domestic Production Activities Deduction?" Tax Notes, August 29, 2016, pp. 1269-1292. |

| 19. |

U.S. Congress, Joint Committee on Taxation, General Explanation of Tax Legislation Enacted in the 110th Congress, committee print, 110th Cong., March 2009, JCS-1-09, pp. 354-355. |

| 20. |

Ibid. |

| 21. |

Oil-related production activities include the production, refining, processing, and transportation of oil and gas. |

| 22. |

Deductions reduce tax liability according to the corporation's marginal tax rate. For example, if a corporation in the 35% tax bracket has a qualifying deduction of $100,000, the corporation's tax liability is reduced by $35,000 (= $100,000 × 35%). |

| 23. |

Business may also deduct net operating losses (NOLs) carried forward from previous tax years, or carried back to past tax years. The presence of NOLs can make it such that QPAI is different from taxable income, which can have implications for calculating the Section 199 deduction, as illustrated in the example for "Company 1" below. |

| 24. |

Depreciation allowances account for the decline in value of tangible capital. When corporations purchase capital assets, such as buildings and equipment, it is expected that these capital assets will be used in the production process for many years. The tax code requires that businesses capitalize such investments, and take depreciation deductions over time. Oftentimes, depreciation deductions are allowed at a rate that approximates the rate at which the capital investment loses value. Other times, depreciation allowances are accelerated, providing additional deductions early-on, increasing the value of the stream of deductions to the taxpayer. Accelerated depreciation allowances can compensate taxpayers for depreciation systems that are not indexed to inflation, and thus do not compensate taxpayers for price changes over time. Thus, when assessing the value of depreciation allowances, a present value methodology should be employed. |

| 25. |

In calculating the tax liability for activities that do not qualify for the Section 199 deduction, p = 0. |

| 26. |

For additional background on these different types of organizations, see CRS Report R43104, A Brief Overview of Business Types and Their Tax Treatment, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 27. |

Letter from George K. Yin, Joint Committee on Taxation, to Mark Prater and Patrick Heck, Senate Finance Committee, Revenue Estimate Request, September 22, 2004. |

| 28. |

Calculations completed following the method described in CRS Report R41743, International Corporate Tax Rate Comparisons and Policy Implications, by [author name scrubbed]. Estimates rely on 2017 tax expenditure estimates, the 2017 CBO corporate tax baseline, and 2013 Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Statistics of Income (SOI) corporate tax revenues before tax credits and after tax credits. |

| 29. |

A discussion of economic efficiency issues with the Section 199 production activities deduction can also be found in [author name scrubbed], "The 2004 Corporate Tax Revisions as a Spaghetti Western: Good, Bad, and Ugly," National Tax Journal, vol. 58, no. 3 (September 2005), pp. 347-365. |

| 30. |

Market failures such as externalities may lead to circumstances under which tax policies can be used to enhance economic efficiency. For example, increasing the tax on activities that generate negative externalities—or indirect costs not reflected in market prices—can reduce the equilibrium amount of the taxed activity, simultaneously enhancing economic efficiency. |

| 31. |

U.S. Department of the Treasury's Office of Tax Policy, The Case for Responsible Business Tax Reform, January 2017, p. 17, https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Documents/Report-Responsible-Business-Tax-Reform-2017.pdf#page=17. |

| 32. |

See U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, American Jobs Creation Act of 2004, Conference Report to Accompany H.R. 4520, 108th Cong., 2nd sess., October 7, 2004, H.Rept. 108-755, p. 275. |

| 33. |

Ibid. |

| 34. |

See Congressional Budget Office, Factors Underlying the Decline in Manufacturing Employment Since 2000, Economic and Budget Issue Brief, Washington, DC, December 23, 2008. |

| 35. |

CRS Report R42742, Federal Tax Benefits for Manufacturing: Current Law and Arguments For and Against, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 36. |

Interest payments on debt used to finance capital investments is deductible. For further discussion, see Rudd A. de Mooij, Tax Biases to Debt Finance: Assessing the Problem, Finding Solutions, International Monetary Fund, IMF Staff Discussion Note, May 3, 2011. |

| 37. |

For additional background, see U.S. Congress, Joint Committee on Taxation, Present Law and Background Relating to Tax Treatment of Business Debt, committee print, prepared by Joint Committee on Taxation, 112th Cong., July 11, 2011, JCX-41-11. |

| 38. |

Generally, within the corporate sector, depreciation schedules tend to generate lower effective tax rates for investments in equipment relative to investments in structures. Bonus depreciation provisions reduce the effective tax rates for investments in equipment even further. For a full analysis of corporate effective tax rates across types of assets and business sectors, see CRS Report RL34229, Corporate Tax Reform: Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. The report provides estimates of effective tax rates across different asset classes with and without the Section 199 production activities deduction. |

| 39. |

This underscores challenges associated with a "corporate only" or "business only" tax reform. For more, see CRS Report R44220, Issues in a Tax Reform Limited to Corporations and Businesses, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 40. |

For various reasons, most of the Section 199 deduction is claimed by large multi-national firms. See Rebecca Lester and Ralph Rector, What Companies Use the Domestic Production Activities Deduction, Tax Notes, August 29, 2016, p. 1269-1292. |

| 41. |

See Kimberly A. Clausing, The American Jobs Creation Act of 2004: Creating Jobs for Accountants and Lawyers, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, Washington, DC, December 2004, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/UploadedPDF/311122_AmericanJobsAct.pdf. |

| 42. |

For analysis of specific companies benefitting from the Section 199 deduction, see Elizabeth Karasmeighan, Domestic Production Deduction: The Impact of Repeal, Bloomberg Government, Washington, DC, January 26, 2012. |

| 43. |

Business receipts are generally gross operating receipts of the corporation, reduced by the cost of returned goods and allowances. Generally, business receipts include all corporate receipts except investment and incidental income. |

| 44. |

Figure 1 includes data for all active corporations, including C corporations, S corporations, U.S. income tax returns for foreign corporations, insurance corporations, regulated investment companies, and real estate investment trusts (IRS Forms 1120, 1120-F, 1120S, 1120-L, 1120-PC, 1120-RIC, 1120-REIT, and 1120-A). Data on Section 199 claims is only reported by C corporations and not S corporations. |

| 45. |

Note that the Section 199 deduction is limited to domestic production activities, while profits, receipts, and assets reported by U.S. taxpayers may be associated with foreign activities. |

| 46. |

The information sector includes publishing industries, motion picture and sound recording industries, broadcasting, telecommunications, and data processing. |

| 47. |

See the Appendix for more information. |

| 48. |

In Figure 1 above, oil and gas extraction is included in the mining sector. |

| 49. |

In Figure 1 above, petroleum refineries are included in the manufacturing sector. |

| 50. |

Previous versions of this report also included the share of profits earned by C corporations in various industrial sectors. The IRS SOI data series upon which this information was based is not available for years after 2008. Thus, the information is no longer included in the report. |

| 51. |

The construction sector may also face challenges if there are substantial losses in the sector. Firms with zero net income for tax purposes cannot benefit from the deduction. |

| 52. |

As previously discussed, the Obama Administration's business tax reform proposed expanding the production activity deduction. The President's Fiscal Commission and the Debt Reduction Task Force in 2010, Sens. Wyden and Coats' tax reform bill in 2011, the House GOP Tax Reform Task Force in 2016, and President Trump's 2016 campaign tax plan all proposed repeal of corporate tax expenditures, including the Section 199 deduction. |

| 53. |

The Tax Reform Act of 2014 proposed to repeal the Section 199 deduction as part of a comprehensive tax reform that repealed various tax expenditures to lower the corporate tax rate and top individual tax rate to 25%. However, it included a 10% surtax on individual income over $400,000 (single; $450,000 joint), excluding "qualified domestic manufacturing income," that resulted in a top rate of 35% on nonmanufacturing individual income. The proposal is similar to repealing Section 199 for corporations but enhancing Section 199 for pass-through businesses from a 9% (or 6% for oil and gas) to a 28.6% deduction. Increasing the gap in the effective tax rates on pass-through income between qualified activity could distort the allocation of capital, impeding economic efficiency. The "qualified domestic manufacturing income" exclusion from the surtax might retain the high compliance costs associated with the complexity of identifying what income derives qualifying activities, at least for pass-through businesses. The proposal could also distort how businesses choose to organize (i.e., incorporate or not) based on the classification of their production activities. |

| 54. |

House Republican Tax Reform Task Force Blueprint, A Better Way: Our Vision for a Confident America: Tax, June 2016, http://abetterway.speaker.gov/_assets/pdf/ABetterWay-Tax-PolicyPaper.pdf. |

| 55. |

The White House and the Department of the Treasury, The President's Framework for Business Tax Reform: An Update, April 2016, https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Documents/The-Presidents-Framework-for-Business-Tax-Reform-An-Update-04-04-2016.pdf. |

| 56. |

For example, The 21st Century Investment Act of 2017 (H.R. 2671) proposes to increase the Section 199 deduction for activities in which the associated research and development occurred within the United States. |

| 57. |

For a discussion of the current research and experimentation credit, including policy concerns, see CRS Report RL31181, Research Tax Credit: Current Law and Policy Issues for the 114th Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 58. |

Department of the Treasury, General Explanations of the Administration's Fiscal Year 2017 Revenue Proposals, February 2016, p. 94, https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Documents/General-Explanations-FY2017.pdf. |

| 59. |

The Bush Administration released a statement on December 6, 2007, opposing repeal of the Section 199 deduction for the oil and gas sector. See The White House, "Statement of Administration Policy: H.R. 6—Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007," press release, December 6, 2007. |

| 60. |

In 2008, the deduction was set at 6% for all eligible activities, but was scheduled to increase to 9% after 2009. |

| 61. |

This provision was intended to repeal the Section 199 deduction for foreign-owned oil companies, such as CITGO, which is owned by the government of Venezuela. |

| 62. |

H.R. 1424 passed a Senate vote on October 1, 2008. |

| 63. |

For additional background, see CRS Report R41400, Economic Analysis of the Enhanced Form 1099 Information Reporting Requirements, by [author name scrubbed]; and CRS Report R41782, 1099 Information Reporting Requirements and Penalties: Recent Legislative Activity, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 64. |

CRS Report R44403, Crude Oil Exports and Related Provisions in P.L. 114-113: In Brief, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 65. |

For background, including reporting on alternative policy proposals considered, see Brian Wingfield and Jonathan N. Crawford, "Lawmakers Consider Tax Break for Oil Refiners," Bloomberg BNA Daily Tax Report, December 11, 2015. |