Preserving Homeownership: Foreclosure Prevention Initiatives

The home mortgage foreclosure rate began to rise rapidly in the United States beginning around the middle of 2006 and remained elevated for several years thereafter. Losing a home to foreclosure can harm households in many ways; for example, those who have been through a foreclosure may have difficulty finding a new place to live or obtaining a loan in the future. Furthermore, concentrated foreclosures can negatively impact nearby home prices, and large numbers of abandoned properties can negatively affect communities. Finally, elevated levels of foreclosures can destabilize housing markets, which can in turn negatively impact the economy as a whole.

In the years that followed the increase in foreclosure rates, there was a broad consensus that there are many negative consequences associated with high numbers of foreclosures. There was less consensus over whether the federal government should have a role in preventing foreclosures and, if so, what that role should be. Nevertheless, in the years after the foreclosure rate began to rise, Congress and both the Bush and Obama Administrations created a variety of temporary initiatives aimed at preventing further increases in foreclosures and helping more families preserve homeownership. These efforts included several initiatives that remained active through 2016 or beyond, including

the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP),

the Home Affordable Refinance Program (HARP),

the Hardest Hit Fund,

the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) Short Refinance Program, and

the National Foreclosure Mitigation Counseling Program (NFMCP).

Two other initiatives, Hope for Homeowners and the Emergency Homeowners Loan Program (EHLP), expired at the end of FY2011.

Some of these federal foreclosure prevention initiatives were criticized as being ineffective or less effective than had been hoped. This led some policymakers to suggest that changes should be made to these initiatives to try to make them more effective, while other policymakers argued that some of these initiatives should be eliminated entirely. For example, in the 112th Congress, the House of Representatives passed a series of bills that, if enacted, would have terminated several foreclosure prevention initiatives (including HAMP and the FHA Short Refinance Program) prior to their intended end dates. However, these bills were not considered by the Senate.

While many observers agreed that slowing the pace of foreclosures was an important policy goal, several challenges have complicated such efforts. These challenges have included implementation issues, such as deciding who has the authority to make mortgage modifications, developing the capacity to complete widespread modifications, and assessing the possibility that homeowners with modified loans might default again in the future. Other challenges have been related to the perception of unfairness in providing help to one set of homeowners over others, the possibility of inadvertently providing incentives for borrowers to default, and the possibility of setting an unwanted precedent for future mortgage lending.

Preserving Homeownership: Foreclosure Prevention Initiatives

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background on Home Mortgage Foreclosures

- Foreclosure Trends

- Impacts of Foreclosure

- Why Might a Household Find Itself Facing Foreclosure?

- Types of Loan Workouts

- Federal Response to Increased Foreclosure Rates

- Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP)

- Program Description

- Basic Eligibility Criteria

- HAMP Funding

- HAMP Results to Date

- Related HAMP Programs

- Selected HAMP Issues

- Home Affordable Refinance Program (HARP)

- Program Description

- Basic Eligibility Criteria

- HARP Results to Date

- Hardest Hit Fund

- HHF Funding: Rounds One through Four

- HHF Funding: Round Five

- State Funding Allocations

- State Hardest Hit Fund Programs

- FHA Short Refinance Program

- Foreclosure Counseling Funding for NeighborWorks America

- Issues and Challenges Associated with Preventing Foreclosures

- Who Has the Authority to Modify Mortgages?

- Volume of Delinquencies and Foreclosures

- Servicer Incentives

- Possibility of Redefault

- Possibility of Distorting Borrower Incentives

- Fairness Issues

- Precedent

- Debate Over the Use of Principal Reduction in Mortgage Modifications

Tables

Summary

The home mortgage foreclosure rate began to rise rapidly in the United States beginning around the middle of 2006 and remained elevated for several years thereafter. Losing a home to foreclosure can harm households in many ways; for example, those who have been through a foreclosure may have difficulty finding a new place to live or obtaining a loan in the future. Furthermore, concentrated foreclosures can negatively impact nearby home prices, and large numbers of abandoned properties can negatively affect communities. Finally, elevated levels of foreclosures can destabilize housing markets, which can in turn negatively impact the economy as a whole.

In the years that followed the increase in foreclosure rates, there was a broad consensus that there are many negative consequences associated with high numbers of foreclosures. There was less consensus over whether the federal government should have a role in preventing foreclosures and, if so, what that role should be. Nevertheless, in the years after the foreclosure rate began to rise, Congress and both the Bush and Obama Administrations created a variety of temporary initiatives aimed at preventing further increases in foreclosures and helping more families preserve homeownership. These efforts included several initiatives that remained active through 2016 or beyond, including

- the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP),

- the Home Affordable Refinance Program (HARP),

- the Hardest Hit Fund,

- the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) Short Refinance Program, and

- the National Foreclosure Mitigation Counseling Program (NFMCP).

Two other initiatives, Hope for Homeowners and the Emergency Homeowners Loan Program (EHLP), expired at the end of FY2011.

Some of these federal foreclosure prevention initiatives were criticized as being ineffective or less effective than had been hoped. This led some policymakers to suggest that changes should be made to these initiatives to try to make them more effective, while other policymakers argued that some of these initiatives should be eliminated entirely. For example, in the 112th Congress, the House of Representatives passed a series of bills that, if enacted, would have terminated several foreclosure prevention initiatives (including HAMP and the FHA Short Refinance Program) prior to their intended end dates. However, these bills were not considered by the Senate.

While many observers agreed that slowing the pace of foreclosures was an important policy goal, several challenges have complicated such efforts. These challenges have included implementation issues, such as deciding who has the authority to make mortgage modifications, developing the capacity to complete widespread modifications, and assessing the possibility that homeowners with modified loans might default again in the future. Other challenges have been related to the perception of unfairness in providing help to one set of homeowners over others, the possibility of inadvertently providing incentives for borrowers to default, and the possibility of setting an unwanted precedent for future mortgage lending.

Introduction

The home mortgage foreclosure rate in the United States began to rise rapidly around the middle of 2006 and remained elevated for several years thereafter. The large increase in home foreclosures negatively impacted some individual households, local communities, and the economy as a whole. Consequently, an issue before Congress was whether to use federal resources and authority to help prevent some home foreclosures and, if so, how to best accomplish that objective. This report provides background on the increase in foreclosure rates in the years following 2006, describes temporary initiatives intended to preserve homeownership that were implemented by the federal government and remained active through at least 2016, and briefly outlines some of the challenges inherent in designing foreclosure prevention initiatives. Additional foreclosure prevention initiatives that were established in 2007 or after but ended prior to the end of 2016 are described in the Appendix.

Foreclosure refers to formal legal proceedings initiated by a mortgage lender against a homeowner after the homeowner has missed a certain number of payments on his or her mortgage. When a foreclosure is completed, the homeowner loses his or her home, which is either repossessed by the lender or sold at auction to repay the outstanding debt. In general, the term "foreclosure" can refer to the foreclosure process or the completion of a foreclosure. This report deals primarily with preventing foreclosure completions.

In order for the foreclosure process to begin, two things must happen: a homeowner must fail to make a certain number of payments on his or her mortgage, and the mortgage holder or mortgage servicer must decide to initiate foreclosure proceedings rather than pursue other options, such as offering a repayment plan or a loan modification. (See the nearby text box explaining the role of mortgage servicers.) A borrower that misses one or more payments is usually referred to as being delinquent on a loan; when a borrower has missed three or more payments, he is generally considered to be in default. Servicers can generally begin foreclosure proceedings after a homeowner defaults on his mortgage, although servicers vary in how quickly they begin foreclosure proceedings after a borrower goes into default. Furthermore, the foreclosure process is governed by state law. Therefore, the foreclosure process and the length of time the process takes vary by state.

|

Mortgage Servicers Mortgage lenders are the organizations that make mortgage loans to individuals. Usually, the mortgage is managed by a company known as a mortgage servicer. Servicers usually have the most contact with the borrower, and are responsible for actions such as collecting mortgage payments, communicating with troubled borrowers, and initiating foreclosures. The servicer can be an affiliate of the original mortgage lender or can be a separate company. Many mortgages are repackaged into mortgage-backed securities (MBS) that are sold to institutional investors. Servicers are subject to contracts with mortgage lenders or MBS investors that obligate them to act in the best interest of the lender or investor, and these contracts may limit servicers' ability to undertake some loan workouts or modifications. The scope of such contracts and the obligations that servicers must meet vary. |

Background on Home Mortgage Foreclosures

Foreclosure Trends

|

Prime, Subprime, and Alt-A Mortgages Prime mortgages are mortgages made to the most creditworthy borrowers who qualify for the best available interest rates. Subprime mortgages are made to borrowers who are considered to be riskier than prime borrowers, and carry higher interest rates to compensate lenders for the increased risk. There is no standard definition of subprime mortgages, and the term is defined differently in different contexts. However, they are often defined as mortgages made to borrowers with credit scores below a certain threshold. Subprime mortgages are also more likely than prime mortgages to include certain nontraditional features. Alt-A mortgages refer to mortgages that are closer to prime but for various reasons do not qualify for prime rates. For example, an Alt-A loan might be made to a borrower with a good credit history, but factors such as the debt-to-income ratio or the level of income and asset documentation prevent the mortgage from being considered prime. |

Home prices began to rise rapidly throughout some regions of the United States beginning in the early 2000s. Housing has traditionally been seen as a safe investment that can offer an opportunity for high returns, and rapidly rising home prices reinforced this view. During this housing "boom," many people decided to buy homes or take out second mortgages in order to access their increasing home equity. Furthermore, rising home prices and low interest rates contributed to a sharp increase in people refinancing their mortgages. Some refinanced to access lower interest rates and lower their mortgage payments, while many also used the refinancing process to take out larger mortgages in order to access their home equity. For example, between 2000 and 2003, the number of refinanced mortgage loans jumped from 2.5 million to over 15 million, and the Federal Reserve estimated that 45% of refinances included households taking equity out of their homes.1 Around the same time, subprime lending also began to increase, reaching a peak between 2004 and 2006.2 (See the nearby text box for a description of prime and subprime mortgages.)

Beginning in 2006 and 2007, home sales started to decline and home prices stopped rising and began to fall in many regions. The rates of homeowners becoming delinquent on their mortgages began to increase, and the percentage of home loans in the foreclosure process in the United States began to rise rapidly beginning around the middle of 2006. Although not all homes in the foreclosure process will end in a foreclosure completion, an increase in the number of loans in the foreclosure process is generally accompanied by an increase in the number of homes on which a foreclosure is completed. According to the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA), an industry group, about 1% of all home loans were in the foreclosure process in the second quarter of 2006. By the fourth quarter of 2009, the rate had more than quadrupled to over 4.5%, and it peaked in the fourth quarter of 2010 at about 4.6%. Since then, the percentage of mortgages in the foreclosure process has decreased, but as of the end of 2016 remained slightly higher than historical standards. In the fourth quarter of 2016, the rate of loans in the foreclosure process was about 1.5%.

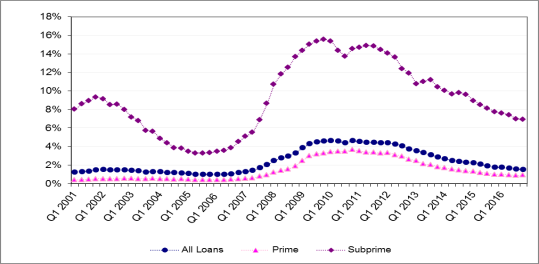

Figure 1 illustrates the trends in the rates of all mortgages, subprime mortgages, and prime mortgages in the foreclosure process between 2001 and 2016.

The foreclosure rate for subprime loans has always been higher than the foreclosure rate for prime loans. For example, in the second quarter of 2006, just over 3.5% of subprime loans were in the foreclosure process compared to less than 0.5% of prime loans. However, both prime and subprime loans saw increases in foreclosure rates in the years following 2006. Like the foreclosure rate for all loans combined, the foreclosure rates for prime and subprime loans both more than quadrupled after 2006, with the rate of subprime loans in the foreclosure process increasing to over 15.5% in the fourth quarter of 2009 and the rate of prime loans in the foreclosure process increasing to more than 3% over the same time period. As of the fourth quarter of 2016, the rate of subprime loans in the foreclosure process was just under 7%, while the rate of prime loans in the foreclosure process was less than 1%.

In addition to mortgages that were in the foreclosure process, an additional 1.6% of all mortgages were 90 or more days delinquent but not yet in foreclosure in the fourth quarter of 2016. These are mortgages that are in default, but for one reason or another, the mortgage servicer has not started the foreclosure process yet. Such reasons could include the volume of delinquent loans that the servicer is handling, delays due to efforts to modify the mortgage before beginning foreclosure, or voluntary pauses in foreclosure activity put in place by the servicer. Considering mortgages that are 90 or more days delinquent but not yet in foreclosure, as well as mortgages that are actively in the foreclosure process, may give a more complete picture of the number of mortgages that are in danger of ultimately resulting in foreclosure completions.

Impacts of Foreclosure

Losing a home to foreclosure can have a number of negative effects on a household. For many families, losing a home can mean losing the household's largest store of wealth. Furthermore, foreclosure can negatively impact a borrower's creditworthiness, making it more difficult for him or her to buy a home in the future. Finally, losing a home to foreclosure can also mean that a household loses many of the less tangible benefits of owning a home. Research has shown that these benefits might include increased civic engagement that results from having a stake in the community, and better health, school, and behavioral outcomes for children.3

Some homeowners might have difficulty finding a place to live after losing their homes to foreclosure. Many will become renters. However, some landlords may be unwilling to rent to families whose credit has been damaged by foreclosure, limiting the options open to these families. There can also be spillover effects from foreclosures on current renters. Renters living in buildings where the landlord is facing foreclosure may be required to move, sometimes on very short notice, even if they are current on their rent payments.4 As more homeowners become renters and as more current renters are displaced when their landlords face foreclosure, pressure on local rental markets may increase, and more families may have difficulty finding affordable rental housing. Some observers have also raised the concern that high numbers of foreclosures can contribute to homelessness, either because families who lose their homes have trouble finding new places to live or because the increased demand for rental housing makes it more difficult for families to find adequate, affordable units. However, researchers have noted that a lack of data makes it difficult to measure the extent to which foreclosures contribute to homelessness.5

If foreclosures are concentrated, they can also have negative impacts on communities. Many foreclosures in a single neighborhood may depress surrounding home values.6 If foreclosed homes stand vacant for long periods of time, they can attract crime and blight, especially if they are not well-maintained. Concentrated foreclosures also place pressure on local governments, which can lose property tax revenue and may have to step in to maintain vacant foreclosed properties.

Why Might a Household Find Itself Facing Foreclosure?

There are many reasons that a household might become delinquent on its mortgage payments. Some borrowers may have simply taken out loans on homes that they could not afford. However, many homeowners who believed they were acting responsibly when they took out a mortgage nonetheless find themselves facing foreclosure. Factors that can contribute to a household having difficulty making its mortgage payments include changes in personal circumstances, which can be exacerbated by macroeconomic conditions, and features of the mortgages themselves.

Changes in Household Circumstances

Changes in a household's circumstances can affect its ability to pay its mortgage. For example, a number of events can leave a household with a lower income than it anticipated when it bought its home. Such changes in circumstances can include a lost job, an illness, or a change in family structure due to divorce or death. Families that expected to maintain a certain level of income may struggle to make payments if a household member loses a job or faces a cut in pay, or if a two-earner household becomes a single-earner household. Unexpected medical bills or other unforeseen expenses can also make it difficult for a family to stay current on its mortgage.

Furthermore, sometimes a change in circumstances means that a home no longer meets a family's needs, and the household needs to sell the home. These changes can include having to relocate for a job or needing a bigger house to accommodate a new child or an aging parent. Traditionally, households that needed to move, or who experienced a decline in income, could usually sell their existing homes. However, the home price declines in many communities nationwide left many households in a negative equity position, or "underwater," meaning that they owed more on their mortgages than the houses were currently worth.7 This limits homeowners' ability to sell their homes for enough money to pay off their mortgages if they have to move; many of these families are effectively trapped in their current homes and mortgages because they cannot afford to sell their homes at a loss.

The risks presented by changing personal circumstances have always existed for anyone who took out a loan, but deteriorating macroeconomic conditions in the years following 2006, such as falling home prices and increasing unemployment, made families especially vulnerable to losing their homes for such reasons. The fall in home values that left some homeowners owing more than the value of their homes made it difficult for homeowners to sell their homes in order to avoid a foreclosure if they experienced a change in circumstances, and it may have increased the incentive for homeowners to walk away from their homes if they could no longer afford their mortgage payments. Along with the fall in home values, another macroeconomic trend accompanying the increase in foreclosures was high unemployment. More households experiencing job loss and the resultant income loss made it difficult for many families to keep up with their monthly mortgage payments.

Mortgage Features

Borrowers might also find themselves having difficulty staying current on their loan payments due in part to features of their mortgages. In the years preceding the sharp increase in foreclosure rates, there had been an increase in the use of alternative mortgage products whose terms differ significantly from the traditional 30-year, fixed interest rate mortgage model.8 While borrowers with traditional mortgages are not immune to delinquency and foreclosure, many of these alternative mortgage features seem to have increased the risk that a homeowner might have trouble staying current on his or her mortgage. Many of these loans were structured to have low monthly payments in the early stages and then adjust to higher monthly payments depending on prevailing market interest rates and/or the length of time the borrower held the mortgage. Furthermore, many of these mortgage features made it more difficult for homeowners to quickly build equity in their homes. Some examples of the features of these alternative mortgage products are listed below.

- Adjustable Rate Mortgages (ARMs): With an adjustable-rate mortgage, a borrower's interest rate can change at predetermined intervals, often based on changes in an index. The new interest rate can be higher or lower than the initial interest rate, and monthly payments can also be higher or lower based on both the new interest rate and any interest rate or payment caps.9 Some ARMs also include an initial low interest rate known as a teaser rate. After the initial low-interest period ends and the new interest rate kicks in, the monthly payments that the borrower must make may increase, possibly by a significant amount.

ARMs make financial sense for some borrowers, especially if interest rates are expected to stay the same or go down in the future or if the gap between short-term and long-term rates gets very wide (the interest rate on ARMs tends to follow short-term interest rates in the economy). The lower initial interest rate on ARMs can help people own a home sooner than they may have been able to otherwise, or can make sense for borrowers who cannot afford a high loan payment in the present but expect a significant increase in income in the future that would allow them to afford higher monthly payments. Further, in markets with rising property values, borrowers with ARMs may be able to refinance their mortgages before the mortgage resets in order to avoid higher interest rates or large increases in monthly payments. However, ARMs can become problematic if borrowers are not prepared for increases in monthly payments that can accompany higher interest rates. If home prices fall, refinancing the mortgage or selling the home to pay off the debt may not be feasible, leaving the homeowner with higher mortgage payments if interest rates rise. - Zero- or Low-Down-Payment Loans: As the name suggests, zero-down-payment and low-down-payment loans require either no down payment or a significantly lower down payment than has traditionally been required. These types of loans can make it easier for certain creditworthy homebuyers who do not have the funds to make a large down payment to purchase a home. This type of loan may be especially useful in areas where home prices are rising more rapidly than income, because it allows borrowers without enough cash for a large down payment to enter markets they could not otherwise afford. However, a low- or no-down-payment loan also means that families have little or no equity in their homes in the early phases of the mortgage, making it difficult to sell the home or refinance the mortgage in response to a change in circumstances if home prices are not increasing. Such loans may also mean that a homeowner takes out a larger mortgage than he or she would otherwise.

- Interest-Only Loans: With an interest-only loan, borrowers pay only the interest on a mortgage—but no part of the principal—for a set period of time. This option increases the homeowner's monthly payments in the future, after the interest-only period ends and the principal amortizes. These types of loans limit a household's ability to build equity in the home, making it difficult to sell or refinance the home in response to a change in circumstances if home prices are not increasing.

- Negative Amortization Loans: With a negative amortization loan, borrowers have the option to pay less than the full amount of the interest due for a set period of time. The loan "negatively amortizes" as the remaining interest is added to the outstanding loan balance. Like interest-only loans, this option increases future monthly mortgage payments when the principal and the balance of the interest amortizes. These types of loans can be useful in markets where property values are rising rapidly, because borrowers can enter the market and then use the equity gained from rising home prices to refinance into loans with better terms before payments increase. They can also make sense for borrowers who currently have low incomes but expect a significant increase in income in the future. However, when home prices stagnate or fall, interest-only loans and negative amortization loans can leave borrowers with negative equity, making it difficult to refinance or sell the home to pay the mortgage debt.

- Low- or No-Documentation Loans: As the name suggests, these types of loans do not require the full range of income and asset documentation that is usually required to obtain a mortgage. Traditionally, these types of loans were made to borrowers with good credit scores and, usually, high incomes or large amounts of personal wealth, but they began to be used more widely in the years preceding the increase in foreclosure rates. Low- or no-documentation loans may be useful for borrowers with income that is difficult to document, such as those who are self-employed or work on commission. However, because a lender does not have full income information, these loans may not be underwritten as rigorously as other types of mortgages. Furthermore, they have the potential to allow for more fraudulent activity on the part of both borrowers and lenders.

While all of these types of loans can make sense for certain borrowers in certain circumstances, many of these loan features began to be used more widely and may have played a role in the increase in foreclosure rates. Some homeowners were current on their mortgages before their monthly payments increased due to interest rate resets or the end of option periods. Some built up little equity in their homes because they were not paying down the principal balance of their loan or because they had not made a down payment. Borrowers without sufficient equity find it difficult to take advantage of options such as refinancing into a more traditional mortgage if monthly payments become too high or selling the home if their personal circumstances change. Stagnant or falling home prices in many regions also hampered borrowers' ability to build equity in their homes, and mortgage payment increases combined with house price declines resulted in limited options for some troubled borrowers.

Types of Loan Workouts

When a household falls behind on its mortgage, there are options that lenders or mortgage servicers may be able to employ as an alternative to beginning foreclosure proceedings. Some of these options, such as a short sale and a deed-in-lieu of foreclosure,10 allow a homeowner to avoid the foreclosure process but still result in a household losing its home. This section describes methods of avoiding foreclosure that allow homeowners to keep their homes; these options generally take the form of repayment plans or loan modifications.

Many types of loan modifications, in particular, are costly for lenders or mortgage investors because they generally reduce the amount that is repaid—either through reducing principal or interest payments—or change the timing of the repayment. However, foreclosure is also costly for lenders or mortgage investors; there are costs associated with the foreclosure process itself, and the sales price of a foreclosure is generally less than the amount that was owed on the mortgage. Therefore, in some circumstances, loan modifications may be less costly than a foreclosure.

Repayment Plans

A repayment plan allows a delinquent borrower to regain current status on his loan by paying back the payments he or she has missed, along with any accrued late fees. This is different from a loan modification, which changes one or more of the terms of the loan (such as the interest rate). Under a repayment plan, the missed payments and late fees may be paid back after the rest of the loan is paid off, or they may be added to the existing monthly payments. The first option increases the time that it will take for a borrower to pay back the loan, but his or her monthly payments will remain the same. The second option results in an increase in monthly payments. Repayment plans may be a good option for homeowners who experienced a temporary loss of income but are now financially stable. However, since they do not generally make payments more affordable, repayment plans are unlikely to help homeowners with unaffordable loans avoid foreclosure in the long term.

Interest Rate Reductions

One form of a loan modification is when the lender voluntarily lowers the interest rate on a mortgage. This is different from a refinance, in which a borrower takes out a new mortgage with a lower interest rate and uses the proceeds from the new loan to pay off the old loan. Unlike refinancing, a borrower does not have to pay closing costs or qualify for a new loan to get a mortgage modification with an interest rate reduction, which can make interest rate reductions a good option for troubled borrowers who owe more on their mortgages than their homes are worth. The interest rate can be reduced permanently, or it can be reduced for a period of time before increasing again to a certain fixed point. Lenders can also freeze interest rates at their current level in order to avoid impending interest rate resets on adjustable rate mortgages. Interest rate modifications are relatively costly to the lender or mortgage investor because they reduce the amount of interest income that the lender or investor will receive, but they can be effective at reducing monthly payments to a more affordable level.

Extended Loan Term/Extended Amortization

Another type of loan modification that can lower monthly mortgage payments is extending the amount of time over which the loan is paid back. While extending the loan term increases the total cost of the mortgage for the borrower because more interest will accrue, it allows monthly payments to be smaller because they are paid over a longer period of time. Most mortgages in the United States have an initial loan term of 30 years; extending the loan term from 30 to 40 years, for example, could result in a lower monthly mortgage payment for the borrower.

Principal Forbearance

Principal forbearance means that a lender or servicer removes part of the principal from the portion of the loan balance that is subject to interest, thereby lowering borrowers' monthly payments by reducing the amount of interest owed. The portion of the principal that is subject to forbearance still needs to be repaid by the borrower in full, usually after the interest-bearing part of the loan is paid off or when the home is sold. Because principal forbearance does not actually change any of the loan terms, it resembles a repayment plan more than a loan modification.

Principal Forgiveness

Principal forgiveness, also called principal reduction or a principal write-down, is a type of mortgage modification that lowers borrowers' monthly payments by forgiving a portion of the loan's principal balance. The forgiven portion of the principal never needs to be repaid. Because the borrower now owes less, his or her monthly payment will be smaller. This option is costly for lenders or mortgage investors, but it can help borrowers achieve affordable monthly payments, as well as increase the equity that borrowers have in their homes and therefore potentially increase their desire to stay current on the mortgage and avoid foreclosure.11

Federal Response to Increased Foreclosure Rates

As foreclosure rates began to increase rapidly in the years after 2006, there was broad bipartisan consensus that the rapid rise in foreclosures had negative consequences on households and communities.12 However, there was less agreement among policymakers about how much the federal government should do to prevent foreclosures. Proponents of enacting government policies and using government resources to prevent foreclosures argued that, in addition to assisting households experiencing hardship, such action may prevent further damage to home values and communities that can be caused by concentrated foreclosures. Supporters also suggested that preventing foreclosures could help stabilize the economy as a whole.

Opponents of government foreclosure prevention programs argued that foreclosure prevention should be worked out between lenders and borrowers without government interference. Opponents expressed concern that people who did not really need help, or who were not perceived to deserve help, could unfairly take advantage of government foreclosure prevention programs. They argued that taxpayers' money should not be used to help people who could still afford their loans but wanted to get more favorable mortgage terms, people who may be seeking to pass their losses on to the lender or the taxpayer, or people who knowingly took on mortgages that they could not afford.

Despite the concerns surrounding foreclosure prevention programs, and disagreement over the proper role of the government in preserving homeownership, the federal government implemented a variety of temporary initiatives to attempt to address the high rates of residential mortgage foreclosures.13 Some of these initiatives were enacted by Congress, while others were created administratively by the George W. Bush and Obama Administrations. Several of these initiatives remained active through at least 2016, including the following:

- the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP), which provided financial incentives to mortgage servicers to modify certain mortgages;

- the Home Affordable Refinance Program (HARP), which allows certain homeowners with little or no equity in their homes to refinance their mortgages;

- the Hardest Hit Fund, which provides funding to certain states to use for locally tailored foreclosure prevention programs;

- the FHA Short Refinance Program, which allowed certain borrowers to refinance their mortgages into new loans insured by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) while reducing the principal amount of the loan; and

- additional funding for housing counseling to assist people in danger of foreclosure.

In addition to federal efforts to address mortgage foreclosures, many state and local governments also implemented a range of initiatives to reduce the number of foreclosures in recent years. The private sector also pursued foreclosure prevention efforts, including creating the HOPE NOW Alliance, a voluntary alliance of mortgage servicers, lenders, investors, counseling agencies, and others that formed in October 2007 with the encouragement of the federal government to engage in active outreach efforts to troubled borrowers.14 While many private lenders and mortgage servicers participate in federal foreclosure prevention initiatives, many also have their own programs or procedures in place to work with borrowers who are having difficulty making their mortgage payments. This report focuses on federal efforts to prevent foreclosure, and does not address these state, local, and private sector efforts.

The following sections describe federal foreclosure prevention initiatives that remained active through at least 2016. The Appendix describes certain additional federal foreclosure prevention initiatives that were implemented in response to the increase in foreclosure rates but ended prior to 2016.

Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP)

On February 18, 2009, President Obama announced the Making Home Affordable (MHA) initiative.15 Making Home Affordable included separate programs to (1) help certain troubled borrowers obtain affordable loan modifications and (2) make it easier for certain homeowners with little or no equity in their homes to refinance their mortgages. These initiatives were known as the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP) and the Home Affordable Refinance Program (HARP), respectively. This section describes HAMP, while a later section describes HARP.16

The deadline to apply for HAMP was December 30, 2016.17 In the past, Treasury extended the program expiration date multiple times,18 but the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113) put the December 31, 2016, expiration date in statute.19 HAMP applications received prior to December 30, 2016, can still be considered for modifications, and modifications that have already been made through HAMP remain in effect.

HAMP was primarily administered by the Department of the Treasury. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac each issued their own HAMP requirements for the mortgages that they owned or guaranteed.20

Program Description

Through HAMP, the government provided financial incentives to participating mortgage servicers who modified eligible troubled borrowers' mortgages in order to reduce the borrowers' monthly mortgage payments to no more than 31% of their monthly income. HAMP was voluntary for mortgage servicers,21 but once a servicer signed an agreement with Treasury to participate in the program, that servicer was bound by the rules of the program and was required to modify eligible mortgages that it serviced according to the program guidelines.

For mortgages that were modified under HAMP, servicers reduced borrowers' payments by reducing the interest rate, extending the loan term, and forbearing principal, in that order, as necessary to reach the target payment ratio of 31% of monthly income. (Servicers were permitted to reduce mortgage principal as part of a HAMP modification, but were not required to do so.) Servicers could reduce interest rates to as low as 2%. The new interest rate is required to remain in place for five years; after five years, if the interest rate is below the market rate at the time the modification agreement was completed, the interest rate can rise by one percentage point per year until it reaches that market rate. (For more information on these interest rate adjustments, see the "Interest Rate Adjustments" subsection later in this report.) Borrowers were required to make modified payments on time during a three-month trial period before the modification could be converted to permanent status.

The government provides financial incentives to servicers, investors, and borrowers for participation. Although the deadline to apply for HAMP has passed, Treasury can continue to pay incentives related to existing modifications (or modifications on mortgages where the application was received prior to the deadline) for several years into the future.

- Servicers received an upfront incentive payment for each successful permanent loan modification and can receive a "pay-for-success" payment for up to three years if the borrower remains current after the modification and the mortgage payment was reduced by at least 6%.

- The borrower can also receive a "pay-for-success" incentive payment (in the form of principal reduction) for up to five years if he or she remains current on the mortgage after the modification is finalized, as well as an additional principal reduction payment at the end of the sixth year after modification if the loan is in good standing.

- Investors received a payment cost-share incentive: after the investor bore the cost of reducing the monthly payment to 38% of monthly income, the government paid half the cost of further reducing the monthly mortgage payment from 38% to 31% of monthly income. Investors could also receive incentive payments for loans modified before a borrower became delinquent and for modifications in areas with declining home prices ("Home Price Decline Protection" incentives), provided that the borrower's monthly mortgage payment was reduced by at least 6%.22

Treasury made a number of changes to the rules governing HAMP in the years after the program was introduced. Some of these changes were relatively minor, while others were more significant. Treasury communicated changes to the HAMP requirements to servicers in documents called Supplemental Directives.23 In addition, Treasury implemented several additional HAMP-related programs to attempt to assist certain groups, such as unemployed borrowers or borrowers with negative equity, which are described in the "Related HAMP Programs" section of this report.

Basic Eligibility Criteria

Borrowers seeking a HAMP modification applied through their mortgage servicer. The requirements governing HAMP were complex, and a number of factors could impact whether or not a specific borrower qualified for the program. However, there were several basic eligibility criteria that a borrower had to meet in order to qualify for a standard HAMP modification, including the following:

- a borrower had to have a mortgage on a single-family (one-to-four unit) property that was originated on or before January 1, 2009,

- the borrower had to live in the home as his or her primary residence (this criterion did not necessarily have to be met to qualify for a certain type of HAMP modification called "HAMP Tier 2," described further below),

- the unpaid principal balance on the mortgage could not be greater than $729,750 for a one-unit property,

- the borrower had to be paying more than 31% of his monthly gross income toward mortgage payments,

- the borrower had to be experiencing a financial hardship that made it difficult to remain current on the mortgage. Borrowers did not need to already be in default on their mortgages in order to qualify, but default had to be "reasonably foreseeable," and

- the estimated net present value of a modification had to result in greater value for the mortgage investor than the net present value of pursuing a foreclosure (this "net present value test" is described in more detail below).

More detailed eligibility criteria and program requirements were included in Treasury's Making Home Affordable Handbook and related policy directives.24 Treasury's requirements governed mortgages that were not backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac; Fannie and Freddie issued their own program requirements for the mortgages that they owned or guaranteed.

Servicers participating in HAMP conducted a "net present value test" (NPV test) on eligible mortgages that compared the expected financial returns to investors from doing a loan modification to the expected financial returns from pursuing a foreclosure.25 If the expected returns from a loan modification were greater than those from foreclosure, servicers were required to reduce borrowers' payments to no more than 38% of monthly income. The government then shared half the cost of reducing borrowers' payments from 38% of monthly income to 31% of monthly income. Servicers were not required to modify mortgages with negative net present value results.

HAMP Tier 2 Eligibility

In early 2012, Treasury announced an expanded version of HAMP, referred to as HAMP Tier 2, for some borrowers who were not eligible for a standard HAMP modification.26 HAMP Tier 2 represented an alternative to the standard HAMP modification (thereafter referred to as HAMP Tier 1), rather than a replacement of the standard HAMP modification.

Under HAMP Tier 2, borrowers still had to meet many of the basic HAMP eligibility criteria, including having a mortgage on a single-family property that was originated on or before January 1, 2009, experiencing a documented hardship, and having an unpaid principal balance below specified thresholds. However, borrowers might have been able to qualify even if they did not meet other requirements to qualify for a standard HAMP modification, such as if they had a mortgage payment-to-income ratio that was already below 31% or if they did not live in the home as a primary residence. In order for a mortgage secured by a rental property to be eligible for HAMP Tier 2, the borrower had to be delinquent on the mortgage (mortgages in "imminent default" were not eligible), the property had to be currently occupied by a tenant or be vacant, and the borrower had to certify that he or she intended to rent the property for at least five years (although at any point in that five-year period the borrower could sell the home or choose to occupy it as a principal residence).

In addition to the eligibility requirements being different for HAMP Tier 2, the way in which servicers modified mortgages and the incentive payment structure also differed. Only mortgages that were not backed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac were eligible for HAMP Tier 2.27

HAMP Funding

The Administration originally estimated that HAMP would cost $75 billion. Of this amount, $50 billion was to come from Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) funds,28 and $25 billion was to come from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac for the costs of modifying mortgages that those entities owned or guaranteed.29

Treasury later revised its estimate of the amount of TARP funds that would be used for HAMP, and used some of the $50 billion originally allocated to HAMP to help pay for other foreclosure-related programs (the Hardest Hit Fund and the FHA Refinance program, both described in later sections of this report). Ultimately, Treasury committed about $38 billion of TARP funds to its foreclosure prevention programs, rather than the initial $50 billion. Of this amount, nearly $28 billion was committed to HAMP and its related programs, $9.6 billion was committed to the Hardest Hit Fund, and just over $100 million was committed to the FHA Short Refinance Program.30

As of December 31, 2016, $16 billion of the $28 billion allocated for HAMP and its related programs had been disbursed.31 In addition, another nearly $8 billion was committed for the payment of future financial incentives associated with existing modifications.32 These amounts did not include any funds that might be committed in the future for modifications of mortgages where the borrower's application had been received prior to the December 30, 2016, application deadline, but where the modification had not yet been finalized.

HAMP Results to Date

The Treasury Department releases quarterly reports detailing the program's progress.33 These reports offer a variety of information, including the number of overall trial and permanent modifications made under HAMP and the number of each that are currently active, the number of trial and permanent modifications made by individual servicers, and the number of trial and permanent modifications underway in each state.34 (As noted earlier, borrowers must successfully complete a three-month trial period before the modification is converted to permanent status.)

The Administration originally estimated that HAMP could eventually help up to between 3 million and 4 million homeowners. As of the fourth quarter of 2016, about 1 million HAMP modifications were active. Of these, about 38,000 were active trial modifications and about 962,000 were active permanent modifications.35 Table 1 shows the total number of HAMP trial and permanent modifications that had started since the program began, along with the number of each that were currently active as of the fourth quarter of 2016.36

|

Trial Modifications |

Permanent Modifications |

Total |

|

|

All Started |

2,511,344 |

1,683,112 |

N/A |

|

Currently Active |

37,680 |

962,209 |

999,889 |

Source: Making Home Affordable Program Performance Report through the Fourth Quarter of 2016.

Note: Includes HAMP Tier 2 modifications.

According to Treasury, the median HAMP modification resulted in a decrease of nearly $500 per month in a borrower's monthly mortgage payment, prior to the impact of any future interest rate adjustments (discussed further in the "Interest Rate Adjustments" section).37

Related HAMP Programs

Treasury also established a number of additional components or subprograms that operated under HAMP. These subprograms generally targeted certain perceived barriers to modifications and/or certain populations of borrowers. Like HAMP, the deadline to apply for these programs was generally December 30, 2016, or in some cases earlier.38 The subprograms that operated under HAMP included the following:39

Second Lien Modification Program (2MP)

Many borrowers have second mortgages on their homes. A mortgage involves a claim, or lien, on the property that gives the lender a security interest in the home in the event that the borrower does not repay the loan. The lien that secures a second mortgage is referred to as a "second lien" because it is second in priority after the lien that secures the first mortgage.

Second liens have the potential to make loan modifications more difficult because (1) modifying the first lien may not reduce households' total monthly mortgage payments to an affordable level if the second mortgage remains unmodified, and (2) holders of primary mortgages may be hesitant to modify the mortgage if the second mortgage holder does not agree to re-subordinate the second mortgage to the first mortgage or to modify the second mortgage as well.

The Second Lien Modification Program was aimed at addressing second liens on properties where the first mortgage was modified through HAMP. If the servicer of the second lien was participating in 2MP, then that servicer had to agree either to modify the second lien in accordance with program guidelines, or to extinguish the second lien entirely in exchange for a lump sum payment, when a borrower's first mortgage was modified under HAMP. (Servicers signed up to participate in 2MP separately from signing up to participate in HAMP.)

Participating servicers and investors could receive financial incentives for modifying or extinguishing second liens under 2MP, and borrowers who remain current on both their HAMP modification and 2MP modification can receive "pay-for-success" incentive payments for up to five years.

2MP was first announced in August 2009. Treasury reported that about 79,000 second-lien modifications were active under 2MP as of the fourth quarter of 2016.40

Home Affordable Foreclosure Alternatives Program (HAFA)

Through the Home Affordable Foreclosure Alternatives (HAFA) program, when a borrower met the basic eligibility criteria for HAMP, but did not ultimately qualify for a modification, did not successfully complete the trial period, or defaulted on a HAMP modification, participating servicers could receive incentive payments for completing a short sale or a deed-in-lieu of foreclosure as an alternative to foreclosure.41 Servicers could receive financial incentive payments for each short sale or deed-in-lieu that was successfully executed, and borrowers could receive financial incentive payments to help with relocation expenses. Investors could receive partial reimbursement if they agreed to share a portion of the proceeds of the short sale with any subordinate lienholders.42 (The subordinate lienholders, in turn, had to release their liens on the property and waive all claims against the borrower for the unpaid balance of the subordinate mortgages.) In order to attempt to streamline the process of short sales and deeds-in-lieu of foreclosure under HAFA, Treasury provided standardized documentation and processes for participating servicers to use.

HAFA went into effect on April 5, 2010, although servicers had the option to begin implementing the program before this date. Treasury reported that about 454,000 HAFA transactions had been completed as of the fourth quarter of 2016.43 Most of these transactions were short sales (390,000) rather than deeds-in-lieu of foreclosure (64,000).

Home Affordable Unemployment Program (UP)

The Home Affordable Unemployment Program (UP) targeted borrowers who were unemployed. Under UP, participating servicers were required to offer forbearance periods to unemployed borrowers who applied for HAMP and met the UP eligibility criteria before evaluating those borrowers for HAMP. The forbearance period lasted for a minimum of 12 months, or until the borrower became re-employed, whichever occurred sooner.44 Borrowers' mortgage payments were lowered to 31% or less of their monthly income through principal forbearance during this time period.

After the forbearance period ended, some borrowers may have regained employment and not needed further assistance. Other borrowers, such as those who were re-employed but at a lower salary, may have been able to qualify for a regular HAMP modification. Still other borrowers may have qualified for a foreclosure alternative such as a short sale or a deed-in-lieu of foreclosure, and some borrowers ultimately may not have been able to avoid foreclosure.

UP went into effect on July 1, 2010, although servicers could choose to implement the program earlier.45 Treasury reported that about 46,000 UP forbearance plans had been started as of the fourth quarter of 2016.46

Principal Reduction Alternative (PRA)

Under the Principal Reduction Alternative (PRA), participating servicers were required to consider reducing principal balances as part of HAMP modifications for homeowners who owed at least 115% of the value of their home. This applied to mortgages that were not backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Fannie's and Freddie's regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), generally does not allow principal reduction for mortgages that Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac own or guarantee. (See the "Debate Over the Use of Principal Reduction in Mortgage Modifications" section later in this report for more information on Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and principal reduction.)

Under PRA, servicers ran two net present value tests for borrowers who owed at least 115% of the value of their homes: the first was the standard NPV test, and the second included principal reduction. If the net present value of the modification was higher under the test that included principal reduction, servicers had the option to reduce principal. However, they were not required to do so. If the principal was reduced, the amount of the principal reduction was initially treated as principal forbearance; the forbearance amount would be forgiven in three equal amounts over three years as long as the borrower remained current on his or her mortgage payments. Treasury offered additional financial incentives to investors when principal was reduced under PRA.

The PRA went into effect on October 1, 2010.47 According to Treasury, about 164,000 permanent PRA modifications were active as of the fourth quarter of 2016. In addition, there were about 37,000 active HAMP modifications that included principal reduction outside of PRA.48

Selected HAMP Issues

In the years after HAMP was created, a number of concerns were raised related to its implementation and effectiveness.49 This section briefly discusses three issues that were raised: interest rate adjustments on HAMP modifications; conversions of trial modifications to permanent status; and assessments of mortgage servicers' performance in implementing HAMP.

Interest Rate Adjustments

Under HAMP, one of the ways in which mortgages were modified to achieve a 31% mortgage payment-to-income ratio was by reducing the interest rate on the mortgage to as low as 2%. The modified interest rate remains in effect for five years from the date of the modification, at which point the interest rate can rise by up to one percentage point per year until it reaches the market interest rate that was in effect at the time of the modification. For example, say a borrower had an interest rate of 6% on his original mortgage, that the interest rate was reduced to 3% under a modification, and that the market interest rate in effect at the time of the modification was 4.5%. After five years, the modified interest rate would increase to 4% from 3%, and the year after that it would increase to 4.5% from 4%. At that point there would be no further interest rate increases for this particular borrower. (Average market interest rates fluctuate over the course of a year, but the average annual interest rates for the years between 2009 and 2016 range from under 4% to just over 5%.)50

The first interest rate increases began in the later quarters of 2014. Treasury estimates that 80% of borrowers who received a standard HAMP modification (i.e., not a "Tier 2" modification) will experience interest rate increases, with a median total monthly payment increase of just over $200 after all of the interest rate increases go into effect.51 However, expected average payment increases vary by state.52

Some housing advocates have expressed concerns that the interest rate increases and resulting payment increases could make it difficult for some borrowers to continue making their mortgage payments. In December 2014, Treasury announced that homeowners who remain current on their payments under HAMP through six years will be eligible for an additional financial incentive of $5,000 in the form of principal reduction. (Borrowers were already eligible for up to $1,000 per year in the form of principal reduction for each of the first five years of the modification if they remained current on their modified mortgages.) The additional financial incentive may, in part, be intended to mitigate the impact of the interest rate increases on borrowers.

Conversion of Trial Modifications to Permanent Status

After HAMP had been in place for several months, many observers began to express concern at the high number of trial modifications that were being canceled rather than converting to permanent status and the length of time that it was taking for trial modifications to become permanent. In response to these concerns, Treasury took a number of steps to attempt to facilitate the conversion of trial modifications to permanent modifications, including outreach efforts to borrowers to help them understand and meet the program's documentation requirements and increased reporting requirements and monitoring of servicers.53 Most notably, since June 1, 2010, Treasury has required servicers to have documented income information from borrowers before offering a trial modification and to verify that information before a borrower can be approved for a trial period plan.54

Prior to June 2010, Treasury had allowed servicers to approve borrowers for trial modifications on the basis of stated income information in order to get trial modifications started more quickly, but the servicers had to verify this information before a modification could become permanent. In cases where the borrowers' stated income information differed from the documented information, servicers often had to re-evaluate borrowers for the program (for example, by running a new NPV test), which sometimes took additional time or resulted in borrowers who had been approved for a trial modification being denied for a permanent modification.

Requiring verified information before a trial modification could begin was expected to result in more trial modifications converting to permanent modifications going forward. As of the fourth quarter of 2016, Treasury reported that about 116,000 trial modifications had been canceled since the requirement for servicers to verify income upfront had gone into effect in June 2010. This is compared to about 675,000 trial modifications that were canceled prior to June 2010.55

Treasury's Assessments of Servicer Performance

Over the years, some have questioned whether mortgage servicers have been implementing HAMP properly. Concerns have been raised that in some cases servicers have wrongly denied eligible borrowers for modifications, repeatedly lost borrowers' paperwork, or otherwise did not evaluate borrowers for HAMP according to program requirements.56

Since April 2011, Treasury has released results of examinations of the performance of the largest servicers participating in HAMP on a quarterly basis. As a result of the first servicer examination, Treasury announced that it would be withholding incentive payments to three of the largest participating servicers due to findings that the servicers' performance under the program was not meeting Treasury's standards. The servicers, Bank of America, JP Morgan Chase, and Wells Fargo, were all found to need "substantial" improvement in several areas.57 Treasury said that it would reinstate the incentive payments when the servicers' performance improved and was no longer found to need substantial improvement. The remaining 6 of the 10 largest servicers were found to need moderate improvement, but Treasury did not withhold incentive payments from those servicers.58

Treasury's subsequent assessments of servicer performance generally showed improvement. As of the fourth quarter of 2016, seven servicers were included in the assessment. In that quarter, one servicer was found to need substantial improvement, one was found to need moderate improvement, and five were found to need minor improvement.59 Although Treasury's assessments have shown improvements in servicer performance, many have continued to raise concerns about servicers' implementation of HAMP and the extent to which some eligible borrowers may have been wrongly denied modifications or may have their modifications terminated without good cause.60

Home Affordable Refinance Program (HARP)

HARP is the refinancing component of the Making Home Affordable initiative. It applies to mortgages backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and the program requirements are set by those entities and their regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA).

HARP was originally scheduled to end on June 10, 2010, but has been extended multiple times.61 HARP is currently scheduled to be available until September 30, 2017. FHFA has announced that it will be implementing a new refinancing option for Fannie Mae- and Freddie Mac-backed loans with high loan-to-value ratios in October 2017. HARP was most recently extended so that it will remain available until the new program is in place.62

Program Description

HARP allows certain homeowners with mortgages owned or guaranteed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac63 to refinance their mortgages in order to benefit from lower interest rates, even if the amount owed on the mortgage exceeds 80% of the value of the home. Generally, borrowers who owe more than 80% of the value of their homes have difficulty refinancing their mortgages, and therefore benefitting from lower interest rates, because they do not have enough equity in their homes. By allowing borrowers who owe more than 80% of the value of their homes to refinance their mortgages, HARP is meant to help qualified borrowers lower their monthly mortgage payments to a level that is more affordable. Rather than targeting homeowners who are behind on their mortgage payments, HARP targets homeowners who have kept up with their payments but have lost equity in their homes due to falling home prices.

Originally, qualified borrowers were eligible to refinance through HARP if they owed up to 105% of the value of their homes (that is, if the loan-to-value ratio, or LTV, was at or below 105%). In July 2009, the program was expanded to include borrowers who owe up to 125% of the value of their homes. In October 2011, as part of a broader package of changes to HARP, the cap on the loan-to-value ratio was removed entirely.

The broader package of changes to HARP that was announced in October 2011 was intended to allow more people to qualify for the program and is commonly referred to as "HARP 2.0."64 In addition to removing the LTV cap, other changes included eliminating or reducing certain fees paid by borrowers who refinance through HARP, waiving certain representations and warranties made by lenders on the original loans (intended to make lenders more likely to participate in HARP by releasing them from some responsibility for any defects in the original loan), and encouraging greater use of automated valuation models instead of property appraisals in order to streamline the refinancing process.65

Basic Eligibility Criteria

Mortgages must meet a variety of requirements in order to be eligible for HARP.66 Some of the key eligibility criteria include the following:

- the original mortgage must be owned or guaranteed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac (limiting the program to mortgages that are already backed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac ensures that these entities do not take on any new risk by backing the refinanced mortgages),

- the mortgage must be for a single-family home,

- the original mortgage must have closed on or before May 31, 2009,67 and

- the borrower must be current on the mortgage payments.

HARP is voluntary, and lenders are not required to refinance mortgages through the program even if the mortgages meet all of the eligibility criteria. Because HARP is a refinancing program, which involves taking out a new mortgage, borrowers can shop around to different lenders to refinance through HARP.

HARP Results to Date

The Administration originally estimated that HARP could help up to between 4 million and 5 million homeowners. According to the Federal Housing Finance Agency, about 3.4 million loans with loan-to-value ratios above 80% had refinanced through HARP as of December 2016.68 The majority of these mortgages (2.4 million) had loan-to-value ratios between 80% and 105%, while about 590,000 mortgages had loan-to-value ratios above 105% up to 125% and about 433,000 mortgages had loan-to-value ratios above 125%. Table 2 shows the number of HARP refinances completed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac since the program began.

|

Fannie Mae |

Freddie Mac |

Total |

|

|

LTV over 80% up to 105% |

1,454,154 |

970,343 |

2,424,497 |

|

LTV over 105% up to 125% |

329,181 |

261,149 |

590,330 |

|

LTV over 125% |

257,273 |

175,571 |

432,844 |

|

Total |

2,040,608 |

1,407,063 |

3,447,671 |

Source: Federal Housing Finance Agency, Refinance Report, Fourth Quarter 2016, https://www.fhfa.gov/AboutUs/Reports/Pages/Refinance-Report-Fourth-Quarter-2016.aspx.

Hardest Hit Fund

Another temporary program created by Treasury is the Hardest Hit Fund (HHF). The HHF provides funds to selected states to use to create foreclosure prevention programs that fit local conditions. Ultimately, 18 states plus the District of Columbia were selected to receive funds through the HHF through several rounds of funding. The funding comes from the TARP funds that Treasury initially set aside for HAMP. Therefore, all Hardest Hit Fund funding must be used in ways that comply with the law that authorized TARP, the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-343), and state HHF programs must be approved by Treasury.

States originally had until December 31, 2017, to use their funds. In 2016, Treasury extended the deadline to December 31, 2020.69

HHF Funding: Rounds One through Four

Initially, there were four rounds of funding through the Hardest Hit Fund. Each round of funding made funds available to certain state housing finance agencies (HFAs) based on certain state characteristics. The Administration set maximum allocations for each state based on a formula, and the HFAs of those states were required to submit their plans for the funds to Treasury for approval in order to receive funds through the program.

The first four rounds of funding were as follows:

- First Round: On February 19, 2010, the Obama Administration announced that it would make up to a total of $1.5 billion available to the HFAs of five states that had experienced the greatest declines in home prices.70 The five states are California, Arizona, Florida, Nevada, and Michigan. The participating states can use the funding for a variety of programs that address foreclosures and are tailored to specific areas, including programs to help unemployed homeowners, programs to help homeowners who owe more than their homes are worth, or programs to address the challenges that second liens pose to mortgage modifications.

- Second Round: On March 29, 2010, a second round of funding made up to a total of $600 million available to five states that had large proportions of their populations living in areas of economic distress, defined as counties with unemployment rates above 12% in 2009 (the five states that received funding in the first round were not eligible). The five states that received funding through this second round are North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, and South Carolina. These states can use the funds to support the same types of programs eligible under the first round of funding, and are subject to the same requirements.71

- Third Round: On August 11, 2010, a third round of funding made a total of up to $2 billion available to 18 states and the District of Columbia, all of which had unemployment rates higher than the national average over the previous year.72 Nine of the states that received funds through the third round of funding also received funding in one of the previous two rounds of Hardest Hit Fund funding.73 The states that received funding in the third round but not in either of the previous two rounds are Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, New Jersey, Tennessee, and the District of Columbia. Like the first two rounds of funding, states had to submit plans for the funds for Treasury's approval. Unlike the first two rounds of funding, states have to use funds from the third round specifically for foreclosure prevention programs that target the unemployed.

- Fourth Round: In September 2010, Treasury announced an additional $3.5 billion of funding to be distributed to the 18 states (and the District of Columbia) that were receiving funding through earlier rounds, bringing the total amount of funding allocated to the HHF to $7.6 billion.

HHF Funding: Round Five

Treasury's authority to make additional commitments of TARP funds expired on October 3, 2010, meaning that Treasury could no longer allocate additional TARP funds to the HHF after that time. However, in December 2015 the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113) authorized Treasury to make up to an additional $2 billion in unused TARP funds available to the HHF. In February 2016, Treasury announced that it was allocating an additional $2 billion to the states participating in the HHF.

The $2 billion was allocated in two phases.74 First, $1 billion was allocated to participating states based on population and utilization of previous HHF funds. States must have used at least 50% of their previous HHF funds to be eligible for this funding.75 Each participating state except for Alabama received additional HHF funding in this first phase of Round Five. Second, an additional $1 billion was allocated competitively among participating states. All but six participating states received additional HHF funding in this second phase of Round Five. Five states did not apply for funding in Phase Two (Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Nevada, and South Carolina), and one state applied but was not awarded funding (Georgia).76

The additional funding brings the total amount committed to the HHF to $9.6 billion.

State Funding Allocations

Table 3 shows the total funding that each participating state has received through the Hardest Hit Fund. In addition to the total, it shows the aggregate amount that each state received in Rounds 1 through 4, and the amount received through each of the phases of Round 5.

|

Total Funding Allocated, All Rounds |

Funds Allocated in Rounds 1-4 |

Funds Allocated in Round 5, Phase 1 |

Funds Allocated in Round 5, Phase 2 |

|

|

Alabama |

$162.5 |

$162.5 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Arizona |

$296.0 |

$267.8 |

$28.3 |

N/A |

|

California |

$2,358.6 |

$1,975.3 |

$213.5 |

$169.8 |

|

Florida |

$1,135.7 |

$1,057.8 |

$77.9 |

N/A |

|

Georgia |

$370.1 |

$339.3 |

$30.9 |

N/A |

|

Illinois |

$715.1 |

$445.6 |

$118.2 |

$151.3 |

|

Indiana |

$283.7 |

$221.7 |

$28.6 |

$33.5 |

|

Kentucky |

$207.0 |

$148.9 |

$30.1 |

$28.0 |

|

Michigan |

$761.2 |

$498.6 |

$74.5 |

$188.1 |

|

Mississippi |

$144.3 |

$101.9 |

$19.3 |

$23.1 |

|

Nevada |

$202.9 |

$194.0 |

$8.9 |

N/A |

|

New Jersey |

$415.1 |

$300.5 |

$69.2 |

$45.4 |

|

North Carolina |

$706.5 |

$482.8 |

$78.0 |

$145.7 |

|

Ohio |

$762.3 |

$570.4 |

$97.6 |

$94.3 |

|

Oregon |

$314.6 |

$220.0 |

$36.4 |

$58.1 |

|

Rhode Island |

$116.0 |

$79.4 |

$9.7 |

$26.9 |

|

South Carolina |

$317.5 |

$295.4 |

$22.0 |

N/A |

|

Tennessee |

$302.1 |

$217.3 |

$51.9 |

$32.8 |

|

Washington, DC |

$28.7 |

$20.7 |

$4.9 |

$3.1 |

|

Total |

$9,600.0 |

$7,600.0 |

$1,000.0 |

$1,000.0 |

Source: Treasury's Hardest Hit Fund website at https://www.treasury.gov/initiatives/financial-stability/TARP-Programs/housing/Pages/Program-Documents.aspx and Department of the Treasury, "Treasury Announces Allocation of Final $1 Billion Among Hardest Hit Fund States," press release, April 20, 2016, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl0434.aspx.

As of the end of December 2016, over $7 billion, or more than 70%, of HHF funds had been drawn down by states. (Funds that have been drawn down by states may or may not have actually been spent by the states to date.77 In order to draw down additional amounts from Treasury, a state may not have more than 5% of its total allocation on hand.) The percentages of their allocations that individual states have drawn from Treasury range from a low of 35% (Alabama) to a high of 89% (Oregon), with most states falling somewhere in between.78 These percentages take into account all HHF funds, including those allocated through Round Five.

State Hardest Hit Fund Programs

As described, states had flexibility to design different types of programs using their Hardest Hit Fund allocations, as long as their programs met the purposes of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act and were approved by Treasury. State HFAs may operate one or more programs with their HHF funds. (States that received funding in the third round are required to use those funds to assist unemployed homeowners.) In general, the types of programs that states have implemented fall under a few broad categories: standard mortgage modification programs, principal reduction programs, mortgage reinstatement programs (to help borrowers pay arrearages and late fees to bring a mortgage current again), programs to help unemployed homeowners with mortgage payments, programs to address second liens, programs to facilitate short sales or deeds-in-lieu of foreclosure, and, more recently, blight elimination programs (programs for demolishing vacant or abandoned homes that are contributing to blight) and down payment assistance programs (intended to help prevent foreclosures by encouraging home buying activity).79 Some states have also used HHF funds for other types of programs to help prevent foreclosures, such as assisting homeowners with reverse mortgages or helping to pay tax liens on properties.

According to Treasury, as of the fourth quarter of 2016 there were more than 80 Hardest Hit Fund programs operating in the 18 states (plus DC) that received Hardest Hit Fund allocations, and these programs had assisted over 290,000 borrowers. 80 States have continued to add or make changes to their Hardest Hit Fund programs.81

FHA Short Refinance Program