Endangered Species Act Litigation Regarding Columbia Basin Salmon and Steelhead

The decline of salmon and steelhead populations in the Columbia Basin began in the second half of the 19th Century. Activities such as logging, farming, mining, irrigation, and commercial fishing all contributed to the decline, and populations further declined since the construction and operation of the Federal Columbia River Power System (FCRPS) in the mid-1900s. In 1991, the Snake River sockeye became the first Pacific salmon stock identified as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). There are now 13 salmon and steelhead stocks that are listed as either threatened or endangered.

FCRPS operations have been analyzed through an ESA process intended to address the impact of operations on protected species. The ESA requires the federal operators of the FCRPS—the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), and the Army Corps of Engineers (Corps)—to consult with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) of the Department of Commerce on how the FCRPS may impact listed species. At the end of the consultation, NMFS issues a biological opinion (BiOp) addressing whether the FCRPS action would jeopardize the continued existence of a listed species or damage its critical habitat. If jeopardy is found, NMFS is required to develop reasonable and prudent alternatives (RPAs) to the proposed action in order to avoid jeopardy.

NMFS can recommend mitigation measures to avoid jeopardy, but protective measures for fish often come at a cost in terms of energy generation or irrigation supply from FCRPS. This tension between natural resources and energy production and irrigation is at the heart of conflict in the Columbia Basin.

Beginning in 1992, NMFS issued a series of BiOps, nearly every one of which courts have found inconsistent with the ESA. Since 2000, federal courts have rejected all or part of NMFS’s four prior BiOps and their supplements. While courts have consistently demanded changes to the BiOps, they also allowed portions of each BiOp to stay in place so that FCRPS operations could continue while the federal agencies attempted to remedy the BiOps.

Most recently, in May 2016, the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon held that NMFS’s 2014 supplemental BiOp (2014 Supplement) did not comply with the ESA. The court cited flaws in NMFS’s conclusion that protected species could be “trending toward recovery” even if the overall population levels remained critically low. The court also called NMFS’s habitat improvement data “too uncertain” and found that NMFS did not properly analyze the effects of climate change.

The district court also held that the FCRPS action agencies (the Corps, BPA, and Reclamation) violated the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) by failing to prepare an environmental impact statement in connection with their proposals for operation of the FCRPS. Although it found the 2014 Supplement to be arbitrary and capricious, the court did not vacate the BiOp. Instead, it remanded for further consultation to be completed by March 1, 2018, and ordered NMFS to keep the 2014 Supplement in place in the interim.

Endangered Species Act Litigation Regarding Columbia Basin Salmon and Steelhead

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Background

- Salmon and Steelhead Listing History

- Consultation and Biological Opinions

- Columbia Basin Salmon Decline

- The First "H": Habitat

- The Second "H": Harvest

- The Third "H": Hatcheries

- The Fourth "H": Hydrosystems

- BiOp Litigation

- 1992 BiOps—No Jeopardy

- 1993 BiOp—No Jeopardy

- 1994 BiOp—No Jeopardy

- 1995 BiOp—Jeopardy and RPAs

- 2000 BiOp—Jeopardy, RPAs, and Offsite Mitigation Actions

- 2004 BiOp—No Jeopardy

- 2005 Snake River BiOp

- The "Fish Accords": Settlement Agreements with States and Tribes

- 2008 BiOp and 2010 Supplement—Avoiding Jeopardy Through the Fish Accords and RPAs

- 2014 Supplement—Avoiding Jeopardy Through RPAs

- Non-BiOp Litigation

- Critical Habitat Determination

- Hatchery Listing Policy

- Litigation over Authorization to Euthanize California Sea Lions

Summary

The decline of salmon and steelhead populations in the Columbia Basin began in the second half of the 19th Century. Activities such as logging, farming, mining, irrigation, and commercial fishing all contributed to the decline, and populations further declined since the construction and operation of the Federal Columbia River Power System (FCRPS) in the mid-1900s. In 1991, the Snake River sockeye became the first Pacific salmon stock identified as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). There are now 13 salmon and steelhead stocks that are listed as either threatened or endangered.

FCRPS operations have been analyzed through an ESA process intended to address the impact of operations on protected species. The ESA requires the federal operators of the FCRPS—the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), and the Army Corps of Engineers (Corps)—to consult with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) of the Department of Commerce on how the FCRPS may impact listed species. At the end of the consultation, NMFS issues a biological opinion (BiOp) addressing whether the FCRPS action would jeopardize the continued existence of a listed species or damage its critical habitat. If jeopardy is found, NMFS is required to develop reasonable and prudent alternatives (RPAs) to the proposed action in order to avoid jeopardy.

NMFS can recommend mitigation measures to avoid jeopardy, but protective measures for fish often come at a cost in terms of energy generation or irrigation supply from FCRPS. This tension between natural resources and energy production and irrigation is at the heart of conflict in the Columbia Basin.

Beginning in 1992, NMFS issued a series of BiOps, nearly every one of which courts have found inconsistent with the ESA. Since 2000, federal courts have rejected all or part of NMFS's four prior BiOps and their supplements. While courts have consistently demanded changes to the BiOps, they also allowed portions of each BiOp to stay in place so that FCRPS operations could continue while the federal agencies attempted to remedy the BiOps.

Most recently, in May 2016, the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon held that NMFS's 2014 supplemental BiOp (2014 Supplement) did not comply with the ESA. The court cited flaws in NMFS's conclusion that protected species could be "trending toward recovery" even if the overall population levels remained critically low. The court also called NMFS's habitat improvement data "too uncertain" and found that NMFS did not properly analyze the effects of climate change.

The district court also held that the FCRPS action agencies (the Corps, BPA, and Reclamation) violated the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) by failing to prepare an environmental impact statement in connection with their proposals for operation of the FCRPS. Although it found the 2014 Supplement to be arbitrary and capricious, the court did not vacate the BiOp. Instead, it remanded for further consultation to be completed by March 1, 2018, and ordered NMFS to keep the 2014 Supplement in place in the interim.

Background

Salmon and Steelhead Listing History

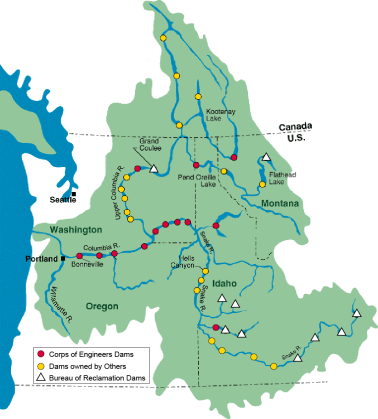

Salmon and steelhead are anadromous fish, meaning they are born in freshwater, migrate to the ocean to mature, and return to their place of birth to spawn.1 Dams and their operations make the migrations treacherous both up and downstream.2 Federal dams have had an effect on salmon and steelhead populations in the Columbia Basin since the 1938 construction of Bonneville Dam, the first dam in the Federal Columbia River Power System (FCRPS).3 FCRPS now includes federal hydropower dams in the Columbia Basin that are operated by either the Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) or Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation).4 (See Figure 1.) Electric power from these projects is marketed by Bonneville Power Administration (BPA).5

|

|

Source: U.S. Army Corps of Eng'rs, http://www.nwd-wc.usace.army.mil/PB/pic/COLMapProj.jpg. |

Currently, eight evolutionarily significant units (ESUs) of salmon and five distinct populations segments (DPSs) of steelhead6 in the Columbia Basin are listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).7 The ESA-protected fish in the Colombia River Basin are

- Snake River sockeye salmon (endangered);

- Snake River spring/summer-run Chinook salmon (threatened);

- Snake River fall-run Chinook salmon (threatened);

- Snake River basin steelhead (threatened);

- Upper Columbia River spring-run Chinook salmon (endangered);

- Upper Columbia River steelhead (threatened);

- Middle Columbia River steelhead (threatened);

- Lower Columbia River Chinook salmon (threatened);

- Lower Columbia River coho salmon (threatened);

- Lower Columbia River steelhead (threatened);

- Columbia River Chum salmon; (threatened);

- Upper Willamette River Chinook salmon (threatened); and

- Upper Willamette River steelhead (threatened).

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS)8 of the Department of Commerce has found that the estimated "current annual salmon and steelhead production in the Columbia River Basin is more than 10 million fish below historical levels, with 8 million of this annual loss attributable to hydropower development and operation."9 Additionally, timber management and grazing have decreased habitat from "approximately 21,000 miles (33,600 km), historically, to approximately 16,000 miles (25,600 km) in 1990, largely due to management practices on U.S. Forest Service (USFS) land."10

Today salmon and steelhead trout in the Columbia River Basin are a mixture of wild fish and those produced in fish hatcheries. Experiments with artificial propagation of salmon to bolster faltering wild stocks began in the late 1800s. Dozens of federal- and state-managed salmon and steelhead trout hatcheries in the Columbia River basin produce more fish annually than do wild stocks.

Consultation and Biological Opinions

The ESA requires federal actions, such as FCRPS operations, to be reviewed to determine whether they are likely to jeopardize the continued existence of threatened and endangered species or damage the species' critical habitat.11 This process is called consultation.12

By statute, the Secretary of the Interior administers the consultation process,13 but it has delegated its authority to either NMFS14 or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) (in the Department of the Interior15).16 With regard to protected anadromous salmon and steelhead in the Columbia Basin, NMFS has administrative authority over the consultation process.17 Thus, if the actions of a federal agency might adversely affect listed salmon or steelhead, they must engage in the consultation process with NMFS.18

The Corps, Reclamation, and BPA are the action agencies for purposes of operating the FCRPS and the consultation process under the ESA.19 Formal consultation is initiated when an action agency submits a biological assessment to NMFS describing the proposed action and its impact on listed species.20 ESA consultation may be triggered by new ESA listings or new or changed federal actions.21 In the case of salmon and steelhead, NMFS considers the biological assessment and the proposed federal action and then issues a biological opinion (BiOp) indicating whether the action would jeopardize protected species.22

In developing a BiOp, NMFS must determine whether the action agencies' conduct will likely jeopardize a listed species or destroy or adversely modify its critical habitat.23 If jeopardy is found, NMFS is required to include reasonable and prudent alternatives (RPAs) to the proposed action in order to avoid jeopardy, provided such alternatives are possible.24

In those cases where NMFS concludes that the action agencies' conduct as originally proposed or as modified by RPAs is not likely to result in jeopardy or adverse modification or destruction of critical habitat, NMFS will issue an Incidental Take Statement to the action agencies.25 The Incidental Take Statement excuses any takes (killing or harming) of listed species for operations covered in the BiOp so long as the action agency complies with the terms and conditions of the statement.26 Without the BiOp and the Incidental Take Statement, the action agency risks violating (and being prosecuted under) the ESA.27

In addition to BiOps for FCRPS operations, NMFS issues salmonid28 BiOps for Upper Snake River29 activities and harvest operations (fishing).30

Columbia Basin Salmon Decline

The configuration and operation of the FCRPS dams can be a polarizing issue for proponents of hydropower development, irrigation, and river navigation and those who support commercial, sport, and tribal fishing as well as environmental conservation.31 Commentators note that Columbia Basin salmon populations have declined due to a number of human actions besides FCRPS operations, including fishing, predation by native and invasive species, water pollution, reduced habitat, and water withdrawals for irrigation.32 Many also assert that these populations will be subject to increasing stress from factors related to climate change such as higher water temperatures, changes in ocean conditions, and lower river flows.33 Actions intended to aid the recovery of these stocks generally fall into one of four categories, known as "the 4-H's": habitat, harvest, hatchery, and hydrosystem.34

The First "H": Habitat

Habitat actions focus on access to, and improvement of, habitat suitable for rearing juvenile salmon and spawning by returning adults. Historically, many parts of the Columbia River watershed have been degraded by logging, mining, farming, and development. Although legitimate economic activities, they have often caused unintended negative consequences for salmon populations. Salmon habitat has been fragmented and degraded by water diversions, obstacles to habitat by structures such as culverts and dams, and loss of vegetation adjacent to rivers and in watersheds. The RPAs specify actions related to upriver habitat where salmon spawn and down-river estuary habitat where salmon transition to their ocean phase.35 Actions to improve habitat include increasing stream flows, reducing water temperature, removing barriers to habitat, and increasing pools, spawning gravels, and side channel habitats.36

Other habitat actions include efforts to remove the salmon's predators, including California sea lions.37 Sea lions generally prey on the salmon congregating at the fish passage facilities, although it is suspected that they also consume salmon in other parts of the Lower Columbia River.38 In 2015, the Corps' monitoring program estimated that sea lions at the Bonneville Dam consumed 10,859 salmonids between January 1 and May 31, 2015, which accounts for 4.3% of the adult salmonid passage.39 To reduce predation on upstream migrating adult salmon, NMFS authorized Washington, Idaho, and Oregon to lethally take (i.e., kill) California sea lions that gather seasonally below Bonneville Dam.40 Individuals and animal rights groups challenged the take authorization in multiple lawsuits, but NMFS's latest authorization from 2012 survived the most recent court challenge, which has led to ongoing efforts to capture and euthanize California sea lions.41

Other predators include the pikeminnow, which feed on juvenile salmon and steelhead. BPA sponsors a program that pays for each pikeminnow caught in the Columbia River. For 2016, there is a reward of $5 to $8 per pikeminnow of at least 9 inches and a $500 reward per tagged fish.42 According to BPA, since the program started, over 4.2 million pikeminnow have been caught, reducing their predation on juvenile salmonids by 40%.43

The Second "H": Harvest

Historically, salmon harvest was one of the main factors that contributed to the decline of Columbia Basin salmonid populations. Commercial and recreational fisheries in the Columbia River are co-managed by the states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, four treaty tribes, and other tribes that traditionally fished these waters.44 All fisheries are subject to review by NMFS for compliance with the ESA. Generally, managers have attempted to minimize the harvest of wild fish, especially listed populations, through a variety of actions. Harvest actions focus on limiting harvest or harm to listed species by requiring selective fishing gear or timing harvest periods to focus fishing on hatchery stocks.45 In mark-selective fisheries, the adipose fins are clipped on hatchery juveniles so fishermen can differentiate returning hatchery fish from wild adults.46

The Third "H": Hatcheries

Hatchery efforts are intended to increase the number of fish through artificial propagation. Some assert that hatchery production reduces predator and harvest pressures on wild fish, while others are concerned that hatchery fish compete with wild salmon and steelhead for food and habitat. Hatcheries also may alter the genetic diversity of specific stocks.

According to the Hatchery Scientific Review Group, a congressionally funded scientific review panel, hatchery management alone will not lead to the recovery of the endangered salmon and steelhead in the Pacific Northwest, but must be done as part of a broader strategy that incorporates actions affecting habitat, harvest rates, water allocation, and other components of the human environment.47 According to the NMFS Hatchery Listing Policy, under certain circumstances hatchery fish may be considered when estimating the populations of fish for listing determinations (i.e., when deciding whether an ESU might be threatened or endangered).48

The Fourth "H": Hydrosystems

Finally, hydrosystem actions that promote species recovery have concentrated on improving the survival of juvenile and adult salmon and steelhead as they migrate past dams and through reservoirs. Hydrosystem actions include structural and operational changes at the dams, such as the addition of juvenile bypass systems and surface-oriented passage routes; the collection and transportation of juveniles in barges and trucks past the dams; the installation of structures to guide fish toward safer passage routes; and water releases either to speed travel down the river or provide safer passage past a dam. Although some federal salmon and steelhead protection measures have been in place for nearly 70 years—Bonneville Dam was constructed in 1938 with a fish ladder to allow upstream passage of returning adult salmon49—the Pacific Northwest Electric Power Planning and Conservation Act (Northwest Power Act) codified a fish protection program to mitigate losses associated with the FCRPS.50

Four options are available to allow downstream migration of fish at a hydropower dam: spill over the dams; pass through the turbines; bypass the dams via a barge or truck; or bypass back into the river.51 Some actions intended to benefit salmon, such as spilling water to help juveniles pass safely downstream, come at a cost in terms of energy production. Such actions may significantly increase power rates in the region.52 Additionally, spill can increase juvenile fish mortality due to injury or disorientation caused by gas bubble disease, making fish susceptible to predation. Although gas bubble disease may occur when fish are exposed to gas supersaturation, especially during vulnerable or sensitive life stages, research suggests that harm to migratory juvenile or adult salmonids depends on characteristics of the site or reach adjacent to the dam.53

Often migration can be assisted by "fish ladders" that allow the fish to pass upstream around the dams or bypasses that allow juveniles to avoid passing through turbines. However, dams also may change the ecology of rivers including food webs and physical conditions, especially in cases where large reservoirs are created. Although fish may be successful in passing around dams, reservoirs decrease the river's flow and may delay fish movement, expose fish to more predation, and increase water temperature to potentially lethal levels. Reservoirs also may inundate spawning and shoreline areas that were formerly productive spawning and rearing habitat.54

As an alternative to altering dam operations to make them more favorable to salmon, some parties advocate partially or entirely removing four dams on the Lower Snake River in Washington. They believe this is the only way to ensure survival of the Snake River salmon and steelhead populations. Dam removal could also result in economic benefits to various fishing and recreation interests. Proponents of dam removal argue that the four Lower Snake River dams do not produce a significant amount of power and assert that these dams cause significant harm to listed species. They claim that removal of the Snake River dams would reduce federal expenditures and revitalize local economies.55 Opponents note that dam removal would only benefit four of the 13 listed salmon and steelhead populations in the Columbia Basin, and the federal agencies should focus on all of the basin's listed salmonids. According to BPA, the Lower Snake River dams are an important part of the Northwest's power supply.56 Additionally, dam removal would preclude downstream barge transport of wheat from Idaho.

Dam removal, especially for older dams, may become an economic necessity if dam relicensing by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission requires expensive modifications to provide for fish passage. The removal of Condit Dam on the White Salmon River, a Columbia River tributary above Bonneville Dam, began with initial breaching on October 26, 2011, and its complete removal the following year.57 Removal of Condit dam has reopened habitat above the former dam to steelhead and salmon for the first time in nearly 100 years. Reportedly, Chinook salmon and steelhead have spawned in areas above the removed structure.58 Many uncertainties remain, and long-term monitoring and adaptive management of the newly accessible habitat are recommended.

BiOp Litigation

More than 20 years of ESA litigation has tracked each BiOp covering the FCRPS, and legal challenges have frequently altered those operations.59 As referenced above, when agencies' planned operations may jeopardize listed species, NMFS may offer reasonable and prudent alternatives (RPAs) to the action agencies' proposal.60 In the FCRPS context, these alternatives can include habitat protection, flow alterations, and fish passage systems, such as ladders or trucks.61 Since the early 1990s, states, conservation organizations, fishing and sporting groups, users of FCRPS-generated energy, and others have challenged NMFS's jeopardy conclusions and RPAs in each BiOp for the FCRPS under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA).62

The APA authorizes reviewing courts to "hold unlawful and set aside agency actions, findings, and conclusions found to be arbitrary, capricious, [or] an abuse of discretion.... "63 To satisfy the arbitrary and capricious standard and survive an APA challenge, a federal agency must show that it "examine[d] the relevant data and articulate[d] a satisfactory explanation for its action, including a 'rational connection between the facts found and the choice made.'"64 A central question raised in the ESA litigation related to the FCRPS was whether NMFS and the action agencies could meet the APA's arbitrary and capricious standard.

A summary of major ESA actions and litigation is presented in the Appendix and discussed below.

1992 BiOps—No Jeopardy

On April 10, 1992, NMFS issued its first BiOp for FCRPS, finding the operations did not jeopardize the continued existence of ESA-protected fish or detrimentally alter its critical habitat.65 NMFS issued additional BiOps later that year (1992 BiOps) in which it found no jeopardy to protected salmonids in the Columbia Basin as a result of ocean fisheries and in-river fisheries.66

Several high volume users of FCRPS-generated energy filed suit challenging the 1992 BiOps.67 Among other legal theories, they asserted that the FCRPS consultation led to restricted hydroelectric operations which caused increased electricity rates.68 The U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon dismissed those claims on the grounds that the energy users lacked standing due to an inherent conflict between the their desire for lower power rates and the ESA's objective of protecting listed salmonids.69 It likened the plaintiffs to a fox guarding a chicken coop: "sure, [the fox] has an interest in seeing that the chickens are well fed, but its [sic] just not the same interest the farmer has, nor is it an interest shared by the chickens."70

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit disagreed with the chicken coop analogy and the ruling on standing,71 but it affirmed the district court's alternative basis for dismissal that the case was moot in light of the fact that NMFS issued a revised BiOp in 1993.72

1993 BiOp—No Jeopardy

On May 26, 1993, NMFS issued a second "no jeopardy" BiOp for FCRPS (1993 BiOp), which was challenged in the District of Oregon in Idaho Department of Fish & Game v. National Marine Fisheries Service.73 There, the district court found the 1993 BiOp was "arbitrary and capricious" because NMFS relied on improper data in calculating the baseline number of protected salmonids in the Columbia Basin.74 According to the court, NMFS used five drought years in which the number of fish were atypically low as a baseline to evaluate the future effect of FCRPS operations on protected species.75 In the 1992 BiOp, by comparison, NMFS used a 15-year range of data from 1975 to 1990 for its baseline.76

The district court also called the overall process used to create FCRPS BiOps "significantly flawed," and it remarked that "the situation literally cries out for a major overhaul. Instead of looking for what can be done to protect the species from jeopardy, NMFS and the action agencies have narrowly focused their attention on what the establishment is capable of handling with minimal disruption."77

The district court directed NMFS to consult with the action agencies and revise the 1993 BiOp, but it did not enjoin FCRPS operations.78 One year later, the Ninth Circuit vacated the district court's decision as moot after the 1993 BiOp expired by its own terms, and NMFS released subsequent BiOps governing FCRPS operations.79

1994 BiOp—No Jeopardy

In March 1994, NMFS issued a BiOp (1994 BiOp) covering FCRPS operations for 1994-1998.80 The 1994 BiOp concluded that FCRPS would not jeopardize protected species or adversely modify the designated critical habitat;81 however, NMFS relied on the same baseline methodology in reaching that conclusion that the district court criticized in the 1993 BiOp.82 NMFS informed the district court in Idaho Department of Fish & Game of the carry-over issue,83 and, because the 1993 BiOp was set to expire, the court directed NMFS and the action agencies to correct the 1994 BiOp rather than the 1993 BiOp.84

In a separate lawsuit, American Rivers v. National Marine Fisheries Services, a group of environmental and commercial fishing organizations challenged the 1994 BiOp, but the court stayed the case while NMFS revised the 1994 BiOp in an attempt to comply with the ruling in Idaho Department of Fish and Game.85

1995 BiOp—Jeopardy and RPAs

In March 1995, NMFS issued a new biological opinion (1995 BiOp), which superseded the 1994 BiOp and concluded that operation of FCRPS jeopardized the continued existence of protected species and adversely modified their critical habitat.86 Given this finding, NMFS proposed RPAs, including a program in which juvenile salmonids would bypass the dam system while being transported in tanker trucks or barges.87

The American Rivers plaintiffs renewed their challenge and argued that the ESA did not permit such a long-term transportation program, but the Ninth Circuit dismissed the suit as non-justiciable.88 Although the Ninth Circuit affirmed earlier dismissals as moot in light of superseding BiOps, it found the American Rivers challenge to the 1995 BiOp to be premature given that the salmonid transportation program was not certain to be implemented.89 "Consideration of long-term salmon transportation as a possible future option is not a final agency action" subject to judicial review, the court concluded.90

In a second lawsuit related to the 1995 BiOp, a group of hydroelectric power users challenged BPA's decision to adopt the jeopardy opinion and to propose RPAs.91 The power users claimed the proposed RPAs were based on inappropriate data and failed to balance salmon protection with the production of hydroelectric power.92 The Ninth Circuit held that, although there was scientific uncertainty regarding the salmon decline, that uncertainty was not so great as to vacate the 1995 BiOp on the grounds that it was arbitrary and capricious.93

2000 BiOp—Jeopardy, RPAs, and Offsite Mitigation Actions

In a BiOp issued in December 2000 (2000 BiOp), NMFS again found that the action agencies' operation of the FCRPS would jeopardize protected salmonid species.94 NMFS proposed RPAs to alleviate the effect of FCRPS operations, but found that, even after implementing RPAs, jeopardy would not be avoided. 95 Consequently, NMFS assessed whether the impact of offsite activities that were unrelated to FCRPS operations would avoid jeopardy when coupled with RPAs.96 The 2000 BiOp concluded the cumulative effect of RPAs and offsite activity was sufficient to avoid jeopardy.97

In the first iteration of a case that is still ongoing after 15 years—National Wildlife Federation v. National Marine Fisheries Service—a group of plaintiffs challenged whether the 2000 BiOp complied with the ESA.98 The matter was assigned to Judge James Redden of the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon, who would continue to oversee the matter for a decade. In his first decision (commonly called NMFS I), Judge Redden found the 2000 BiOp to be inconsistent with the ESA, in large part due to his conclusion that the "offsite activities" which NMFS relied upon were dependent on the actions of states, tribes, and third parties that were not reasonably certain to occur. 99 Judge Redden remanded the case to the agency level to revise the 2000 BiOp to conform to his decision.100

2004 BiOp—No Jeopardy

Rather than revise the 2000 BiOp to address the NMFS I court's concerns on remand, NMFS issued "an entirely new biological opinion" in 2004 (2004 BiOp).101 The 2004 BiOp employed what the Ninth Circuit called a "novel approach"102 in which NMFS excluded the effect of "each of the dams [that] already exists" from its evaluation because those dams' "existence is beyond the scope of the present discretion of the Corps and [Reclamation] to reverse."103 Rather than evaluate the aggregate impact of the FCRPS on the protected species, NMFS only evaluated the discretionary elements of the FCRPS operations.104 In revising its analyses in this way, the 2004 BiOp reached a no-jeopardy conclusion.105

Judge Redden found this approach to be incompatible with the ESA, and, after identifying four fundamental flaws in the 2004 BiOp,106 he issued a preliminary injunction requiring the action agencies to modify the FCRPS operations proposed in the 2004 BiOp.107 On an expedited appeal, the Ninth Circuit largely affirmed the district court's preliminary injunction award without addressing the merits of whether the 2004 BiOp complied with the ESA.108

Following remand by the Ninth Circuit, Judge Redden ordered NMFS to reengage in consultation and produce a new BiOp.109 Although NMFS argued that it was inappropriate for the court to supervise an interagency consultation, Judge Redden monitored the agencies' progress and provided detailed instructions on activities he required to take place during the consultation process.110 Two months later, the district court partially granted another motion for preliminary injunction, modifying a portion of the FCRPS' dam operations during the spring and summer of 2006.111

On April 7, 2007, two and a half years after NMFS issued the 2004 BiOp, the Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court's decision that the 2004 BiOp was structurally flawed.112 Among other issues, the Ninth Circuit criticized NMFS for limiting its evaluation to a study of whether the effects of the proposed FCRPS' operations were "appreciably" worse than baseline conditions.113 According to the Ninth Circuit, this approach failed to take into account the severely degraded baseline conditions, which, even if appreciably improved, could result in a "slow slide into oblivion" in which a "listed species could be gradually destroyed, so long as each step on the path to destruction is sufficiently modest."114

2005 Snake River BiOp

In 2005, NMFS issued a BiOp separately addressing the effects of Reclamation's proposed operations on a portion of the Snake River (2005 Snake River BiOp).115 This BiOp was also challenged in the District of Oregon in a case before Judge Redden.116 Although Judge Redden rejected the argument that the Snake River must be included in the FCRPS BiOp, he still found the 2005 Snake River BiOp to be arbitrary and capricious because it utilized the same methodology as in the 2004 BiOp for the FCRPS that the Court held to be flawed.117 Judge Redden remanded the 2005 Snake River BiOp to the agency level, and NMFS issued a revised BiOp on May 5, 2008.118

The "Fish Accords": Settlement Agreements with States and Tribes

In 2008, BPA, the Corps, and Reclamation entered into 10-year agreements with the Columbia Basin tribes and states of Idaho, Montana, and Washington.119 In what has come to be known as the "Fish Accords," the parties agreed upon the terms of a BiOp for the FCRPS, and BPA committed to funding up to $933 million in mitigation projects in exchange for the state and tribal parties' commitment to support the BiOp in litigation.120 Environmental groups, fishing interests, and the state of Oregon, who have also acted as plaintiffs, were not parties to the Fish Accords.

2008 BiOp and 2010 Supplement—Avoiding Jeopardy Through the Fish Accords and RPAs

In May 2008, NMFS issued a new FCRPS BiOp (2008 BiOp) in which it used the Fish Accords as the foundation for its habitat restoration and mitigation plans.121 Relying on RPAs and the proposed actions in the Fish Accords, NMFS concluded that FCRPS operations would not jeopardize listed species through 2018.122 NMFS supplemented the 2008 BiOp in December 2010 (2010 Supplement) in order to address concerns expressed by Judge Redden and incorporate its latest agreements with Columbia Basin states and tribes.123

In a continuation of the case before Judge Redden that began with the 2000 BiOp, a group of environmental organizations, anglers, energy conservationists, and the state of Oregon challenged the 2008 BiOp and 2010 Supplement (collectively, the 2008/2010 BiOp).

For the first time since 1995, the court ruled that a portion of NMFS's BiOp complied with the ESA. Specifically, Judge Redden found that the section of the 2008/2010 BiOp addressing FCRPS operations through the end of 2013 identified "specific and beneficial mitigation measures" which were lawful and could remain in place.124

For the portion of the BiOP addressing operations between 2014 and 2018, however, the court ruled that NMFS relied on "habitat mitigation measures that are neither reasonably specific nor reasonable certain to occur, and in some cases not even identified."125 Judge Redden remanded the 2008/2010 BiOp for further consultation on post-2013 operations, and he ordered NMFS to produce a supplement by January 1, 2014, that considers "whether more aggressive action, such as dam removal and/or additional flow augmentation and reservoir modifications are necessary to avoid jeopardy."126

2014 Supplement—Avoiding Jeopardy Through RPAs

In January 2014, NMFS issued a second supplement to the 2008 BiOp.127 In this most recent BiOp (2014 Supplement), NMFS did not reverse its finding from 2008 that jeopardy could be avoided through RPAs.128 The plaintiffs challenged the 2014 Supplement, and, on May 6, 2016, the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon again concluded that NMFS did not satisfy the ESA.129

Through a newly assigned judge, Judge Michael H. Simon, the court cited flaws in NMFS's conclusion that protected species could be "trending toward recovery" even if the overall population levels remained critically low, called NMFS's habitat improvement data "too uncertain," and found that NMFS did not properly analyze the effects of climate change.130 Although the court found the 2014 Supplement to be arbitrary and capricious, it did not vacate the BiOp. Instead, it remanded for further consultation to be completed by March 1, 2018, and ordered NMFS to keep the 2014 Supplement in place in the interim.131

The challengers to the 2014 Supplement also successfully asserted a new claim that the action agencies (the Corps and Reclamation) violated the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 ("NEPA")132 because they did not prepare an environmental impact statement (EIS) in connection with the RPAs in the 2014 Supplement.133 NEPA requires certain agencies to complete an environmental impact statement in connection with any "major Federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the human environment."134 The court found the Corps and Reclamation relied upon environmental impact statements that were either "too stale" or too "narrowly focused," and it asked for additional briefing from regarding a timeline in which the EIS should be completed.135 NMFS, the Corps, and Reclamation have requested five years to prepare the EIS.136

Non-BiOp Litigation

Critical Habitat Determination

Other litigation has affected the way in which the ESA has been applied to Columbia River anadromous fish. When the U.S Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit ruled that the FWS's method of determining critical habitat under the ESA was flawed,137 NMFS agreed to settle a suit that challenged its critical habitat determination for the Columbia River.138 NMFS had used a methodology similar to FWS in determining how economic factors were used in its determination of critical habitat.139

Hatchery Listing Policy

Litigants have also challenged whether hatchery-raised salmon and steelhead should be listed as threatened under the ESA under NMFS's Hatchery Listing Policy (HLP). Issued as interim policy in 1993, the HLP provides guidance on how NMFS treats stocks of hatchery salmon and steelhead when deciding which species should be listed as protected under the ESA.140 In the interim policy, NMFS concluded that certain hatchery fish could be included in the same evolutionary significant unit (ESU) as wild fish, which were listed, but it nevertheless excluded stocks of hatchery fish in its listing.141 A federal court found this approach violated the ESA by listing distinctions below the species level.142 If hatchery and wild salmon were in the same ESU, the court reasoned, they should have the same listing status.143

NMFS revised the interim policy and issued a final HLP in 2005.144 When determining whether to list a species as threatened or endangered, the final HLP requires NMFS to consider the status of the ESU as a whole rather than the status of only the wild fish.145 It also states that an entire ESU would be listed, rather than just the wild fish.146 This revised approach resulted in a downlisting of certain fish, such as steelhead trout, from endangered to threatened.147

Two suits were filed in two federal district courts challenging the final HLP. A suit in the Western District of Washington addressed the HLP's application to steelhead (the "steelhead case"),148 and a suit in the District of Oregon challenged its effect on salmon (the "salmon case").149

In the steelhead case, a diverse set of plaintiffs150 challenged both sides of the hatchery argument: one group argued that hatchery steelhead should be considered distinct from wild steelhead, while another argued that NMFS should make no distinction between places of origin.151 The district court concluded NMFS erred in downlisting steelhead based on the condition of the entire ESU—both hatchery and wild—rather than focusing on the "benchmark of naturally self-sustaining populations that is required under the ESA[.]"152

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit reversed that portion of the district court's ruling and concluded that the final HLP complied with the ESA.153 The Ninth Circuit gave discretion to NMFS's analysis and concluded that the downlisting was based on "substantial ... scientific data, and not mere speculation[.]"154

In the salmon case, NMFS distinguished between hatchery stocks of salmon and wild or "natural" salmon. The U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon rejected the plaintiffs' argument that the ESA required hatchery salmon and wild salmon to be treated equally for listing purposes when they are included in the same ESU,155 and the Ninth Circuit affirmed.156

Litigation over Authorization to Euthanize California Sea Lions

To reduce predation on upstream migrating adult salmon, NMFS authorized Washington and Oregon in March 2008157 to lethally take California sea lions that gather below the Bonneville Dam.158 The authorization was revoked in November 2010, following a Ninth Circuit decision that the permit for lethal removal was contrary to law.159 The court found that NMFS could not justify killing California sea lions when their take of the salmon was shown to be no larger than that of commercial fishing; NMFS had described the effect of commercial fishing as "minor" and "minimal" in past statements.160

In May 2011, NMFS authorized states to euthanize up to 85 California sea lions, but withdrew that authorization in July 2011,161 in response to a lawsuit.162 Following a second application process, NMFS reissued Letters of Authorization in March 2012 to Washington, Oregon, and Idaho allowing the states to remove up to 92 animals.163

A group of plaintiffs, including the Humane Society, challenged the 2012 authorization in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia arguing that it did not comply with the Ninth Circuit's decision.164 On review (and after the case was transferred to the District of Oregon), the Ninth Circuit sided with NMFS in this legal bout, finding that, although the plaintiffs raised "valid concerns," the 2011 authorization was sufficiently grounded in scientific data to explain the need to euthanize.165

With the legal challenge resolved, states have since lethally removed sea lions under the 2012 authorization.166 Between 2008 and 2015, the Departments of Fish and Wildlife for the states of Oregon and Washington have removed 102 California sea lions.167 Of those removed, 15 were placed in a zoo or aquarium, 87 were euthanized by lethal injection, and seven died in captivity.168

The 2012 letter of authorization expired on June 30, 2016, and, on January 27, 2016, Washington, Oregon, and Idaho submitted an application for a five-year extension.169 NMFS agreed that the states' applications showed "sufficient evidence of the [predation] problem[,]"170 and it issued a new letter of authorization on June 30, 2016.171

Appendix. Chronology of Major ESA Actions and Litigation

Table A-1. Chronology of Major ESA Actions and Litigation on

Columbia Basin Pacific Salmon and Steelhead Trout

(cases are in bold)

|

Date |

Action or Court Decision |

Citation or Link |

|

November 20, 1991 |

NMFS published determination that Snake River sockeye salmon were endangered. |

56 Fed. Reg. 58,619 |

|

January 3, 1992 |

FWS published notice that Snake River sockeye salmon had been listed as endangered. |

57 Fed. Reg. 212 |

|

April 10, 1992 |

NMFS issued its first BiOp for operation of the FCRPS, the 1992 BiOp, finding no jeopardy. |

|

|

April 22, 1992 |

NMFS published determinations that Snake River spring/summer-run Chinook salmon and Snake River fall-run Chinook salmon were threatened. |

57 Fed. Reg. 14,653 |

|

May 1, 1992 |

NMFS issued no jeopardy BiOp for harvests by Pacific Ocean Fisheries. |

|

|

June 3, 1992 |

NMFS published a correction of its determination that Snake River spring/summer-run Chinook salmon and Snake River fall-run Chinook salmon were threatened. In its correction, NMFS clarified that the ESU includes populations in the Clearwater River. |

57 Fed. Reg. 23,458 |

|

June 12, 1992 |

NMFS issued no jeopardy BiOp for harvest for Columbia River Fisheries Management Plan. |

|

|

April 1, 1993 |

District court held that power users lacked standing to challenge three BiOps of 1992. |

Pacific Northwest Generating Cooperative v. Brown, 822 F. Supp. 1479 (D.D.C. 1993) |

|

May 26, 1993 |

NMFS issued its second BiOp for operation of the FCRPS, the 1993 BiOp, finding no jeopardy. |

|

|

October 25, 1993 |

District Court held that the Forest Service violated the ESA for failing to consult on Wallowa-Whitman & Umatilla National Forest land management plan's impacts on salmon. |

PRC v. Robertson, No. 92-1322-MA (D. Or. October 25, 1993) |

|

December 2, 1993 |

The Corps, Reclamation, and BPA forwarded a biological assessment to NMFS with a request for consultation on the 1994-1998 operation of the FCRPS. |

|

|

December 28, 1993 |

NMFS published critical habitat (CH) designations for Snake River sockeye salmon, Snake River spring/summer-run Chinook salmon, and Snake River fall-run Chinook salmon. |

58 Fed. Reg. 68,543 |

|

March 16, 1994 |

NMFS issued "Section 7 Consultation, BiOp, Reinitiation of Consultation on 1994-1998 Operation of the Federal Columbia River Power System and Juvenile Transportation Program in 1995 and future years," a.k.a 1994 BiOp, finding no jeopardy. |

|

|

March 28, 1994 |

District court held that the 1993 BiOp was held arbitrary and capricious, in part for using a baseline of 1984-1990 for data, even though 1986-90 were drought years, rather than the 1975-90 baseline typically used. The court found the BiOp did not include structural improvements to dams when it included dams in the baseline. |

Idaho Dept. of Fish and Game v. NMFS, 850 F. Supp. 2d 886 (D. Or. 1994), vacated as moot by 56 F.3d 1071 (9th Cir. 1995) |

|

August 18, 1994 |

NMFS published an emergency interim rule wherein NMFS determined that Snake River spring/summer-run Chinook salmon and Snake River fall-run Chinook salmon warranted reclassification from threatened to endangered. |

59 Fed. Reg. 42,529 |

|

September 28, 1994 |

Power users challenged three 1992 BiOps—FCRPS, and two harvest BiOps. The challenge to the FCRPS BiOp was declared moot due to 1993 consultation. |

Pacific Northwest Generating Cooperative v. Brown, 38 F.3d 1058 (9th Cir. 1944), amending and superseding 25 F.3d 1443 (1994) |

|

March 2, 1995 |

NMFS issued a revised BiOp for the 1994-1998 FCRPS operations, a.k.a 1995 BiOp, finding jeopardy. |

|

|

April 14, 1995 |

District court rejected claim that transporting juveniles as part of RPA within 1995 BiOp violated ESA. |

American Rivers v. NMFS, No. 94-940-MA (D. Or. April 14, 1995) |

|

April 2, 1997 |

Court held that suit based on 1994 BiOp was moot because the 1995 BiOp had already replaced it. |

American Rivers v. NMFS, 109 F.3d 1484 (9th Cir. 1997); amended by 126 F.3d 1118 (9th Cir. 1997) |

|

August 18, 1997 |

NMFS published determinations that Upper Columbia River steelhead trout were endangered and the Snake River Basin steelhead trout were threatened. NMFS extended the deadline for a final listing determination for Lower Columbia River steelhead trout. |

62 Fed. Reg. 43,937 and 43,974 |

|

January 12, 1998 |

NMFS, citing improvements in the status of the ESUs, withdrew its proposed rule to reclassify Snake River spring/summer-run Chinook salmon and Snake River fall-run Chinook salmon from threatened to endangered. |

63 Fed. Reg. 1807 |

|

January 21, 1998 |

Action agencies (Corps, BPA, and Reclamation) transmitted their Biological Assessment for 1998 and Future Operation of the Federal Columbia River Power System, Upper Columbia and Lower Snake River Steelhead to NMFS. |

|

|

March 19, 1998 |

NMFS published a determination that Lower Columbia River steelhead trout were threatened. |

63 Fed. Reg. 13,347 |

|

May 14, 1998 |

NMFS issued its Supplemental BiOp to the 1995 BiOp. |

|

|

February 5, 1999 |

NMFS proposed CH for endangered Upper Columbia River steelhead trout as well as threatened Snake River Basin, Lower Columbia River, Upper Willamette River, and Middle Columbia River steelhead trout. |

64 Fed Reg. 5740 |

|

March 24, 1999 |

NMFS published determinations that Lower Columbia River and Upper Willamette River Chinook salmon were threatened, and that the Upper Columbia River spring-run Chinook salmon were endangered. |

64 Fed. Reg. 14,308 |

|

March 25, 1999 |

NMFS published a determination that Columbia River chum salmon were threatened. NMFS published determinations that Middle Columbia River and Upper Willamette River steelhead trout were threatened. |

64 Fed. Reg. 14508 and 14517 |

|

May 10, 1999 |

Industrial users of BPA energy challenged changes imposed by the NMFS BiOp for Snake River sockeye and spring/summer and fall Chinook salmon. The court found BPA was not arbitrary in adopting the RPAs in NMFS jeopardy opinion. |

Aluminum Co. of America v. Bonneville Power Admin., 175 F.3d 1156 (9th Cir. 1999), cert. denied, 528 U.S. 1138 (2000) |

|

August 2, 1999 |

FWS published a notice listing Lower Columbia River and Upper Willamette spring-run Chinook salmon, Columbia River chum salmon, and Middle Columbia River and Upper Willamette River steelhead trout as threatened, and listing Upper Columbia River spring-run Chinook salmon as endangered. |

64 Fed. Reg. 41,835 |

|

February 16, 2000 |

NMFS published CH designations for Lower Columbia River, Upper Willamette River, and Upper Columbia River spring-run Chinook salmon; Columbia River chum salmon; and Upper Columbia River, Snake River Basin, Lower Columbia River, Upper Willamette River, and Middle Columbia River steelhead trout. |

65 Fed. Reg. 7764 |

|

July 10, 2000 |

NMFS published Section 4(d) rule to regulate activities affecting threatened species for Snake River Basin, Lower Columbia River, Middle Columbia River, and Upper Willamette River steelhead trout; and for Snake River spring/summer-run, Snake River fall-run, Lower Columbia River and Upper Willamette River Chinook salmon, and Columbia River chum salmon. |

65 Fed. Reg. 42,422 |

|

December 21, 2000 |

NMFS issued 2000 BiOp for FCRPS impacts on salmon and steelhead. |

Available onlinea |

|

April 30, 2002 |

District court accepted the consent order that vacated the CH designations for salmon and steelhead, pursuant to 10th Circuit decision finding FWS did not use economic factors correctly. [New Mexico Cattlegrowers' Association v. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 248 F.3d 1277 (10th Cir. 2001).] NMFS had used a similar method for the Columbia River. |

National Association of Home Builders, Inc. v. Evans, 2002 WL 1205743 (D.D.C. April 30, 2002) |

|

May 7, 2003 |

District court invalidated the 2000 BiOp and remanded it to NMFS, finding the no jeopardy determination was arbitrary and capricious because NMFS limited the scope to mainstems of Columbia and Snake, and relied on nonfederal mitigation. |

National Wildlife Federation v. NMFS, 254 F. Supp. 2d 1196 (D. Or. 2003) |

|

September 29, 2003 |

In response to the April 30, 2002 court order, NMFS removed CH designations for Lower Columbia River, Upper Willamette River, and Upper Columbia River spring-run Chinook salmon; Columbia River chum salmon; and Upper Columbia River, Snake River Basin, Lower Columbia River, Upper Willamette River, and Middle Columbia River steelhead trout. |

68 Fed. Reg. 55,900 |

|

June 14, 2004 |

NMFS proposed relisting Upper Willamette River, Lower Columbia River, Middle Columbia River, Snake River Basin, and Upper Columbia steelhead trout; Upper Willamette River, Lower Columbia River, Snake River fall-run and Snake River spring/summer-run Chinook salmon; and Columbia River chum salmon as threatened as well as Snake River sockeye salmon and Upper Columbia River spring-run Chinook salmon as endangered (to reflect how the inclusion of certain hatchery stocks might influence listing determinations). In addition, Lower Columbia River coho salmon were proposed to be listed as threatened. |

69 Fed. Reg. 33,102 |

|

August 10, 2004 |

Plaintiffs challenged the March 1999 listing of four salmon. The court stayed the listing of Upper spring-run salmon, Puget Sound, Lower Columbia River, and Upper Willamette spring-run salmon, pending final hatchery policy (due June 14, 2005). |

Common Sense Salmon Recovery v. Evans, 329 F. Supp. 2d 96 (D.D.C. 2004) |

|

November 30, 2004 |

NMFS issued 2004 BiOp on FCRPS operations' impact on salmon and steelhead, finding no jeopardy. |

Available onlineb |

|

March 31, 2005 |

FWS issued a BiOp (2005 Upper Snake River BiOp) on operations and maintenance of the Reclamation Upper Snake River Basin Projects above Brownlee Reservoir. |

Available onlinec |

|

May 26, 2005 |

District court issued a preliminary injunction blocking implementation of the 2004 BiOp, and ordering summer water through spillgates rather than through turbines at certain dams. |

National Wildlife Federation v. NMFS, 2005 WL 1278878 (D. Or. May 26, 2005) |

|

June 28, 2005 |

NMFS relisted Upper Columbia River spring-run Chinook salmon and Snake River sockeye salmon as endangered as well as Lower Columbia River/Southwest Washington coho salmon, Snake River fall-run, Snake River spring/summer-run, Lower Columbia River, and Upper Willamette River Chinook salmon, and Columbia River chum salmon as threatened. |

70 Fed Reg. 37,160 |

|

September 1, 2005 |

Appellate court affirmed the district court opinion of May 26, 2005, that the 2004 BiOp for FCRPS was flawed. The Ninth Circuit found no abuse of discretion in district court injunction, and remanded the issue of whether the district court's preliminary injunction was narrowly tailored. [District court decision: 2005 WL 1278878 (D. Or. May 26, 2005).] |

National Wildlife Federation v. NMFS, 422 F.3d. 782 (9th Cir. 2005) |

|

October 7, 2005 |

District court remanded the 2004 BiOp to NMFS, directing NMFS and action agencies to comply with ESA, and to complete new BiOp within one year. The decision kept the 2004 BiOp in place while new one was being drafted. |

National Wildlife Federation v. NMFS, 2005 WL 2488247 (D. Or. October 7, 2005) |

|

January 5, 2006 |

NMFS relisted Snake River basin steelhead trout, Lower Columbia River steelhead trout, Upper Willamette River steelhead trout, and Middle Columbia River steelhead trout as threatened. |

71 Fed. Reg. 834 |

|

May 23, 2006 |

District court rejected the 2005 Upper Snake BiOp for using a comparative approach to determine jeopardy, saying the NMFS should have aggregated the effects. The court found NMFS failed to consider combined effects from proposed action and existing baseline. The court clarified that NMFS did not abuse its discretion in separating Upper Snake from rest of Columbia, but that a more cohesive strategy would occur if BiOp considered them both. |

American Rivers v. NOAA-Fisheries, 2006 WL 1455629 (D. Or. May 23, 2006) |

|

September 26, 2006 |

The court remanded the 2005 Upper Snake BiOp but left it in place while NMFS prepared new one. |

American Rivers v. NOAA-Fisheries, 2006 WL 2792675 (D. Or. September 26, 2006) |

|

April 9, 2007 |

The Ninth Circuit affirmed the October 7, 2005, district court decision, rejecting the 2004 BiOp for failing to consider nondiscretionary projects' impacts, failing to incorporate degraded baseline, and inadequately evaluating impacts of dams. The court criticized the use of comparative approach rather than aggregate. |

National Wildlife Federation v. NMFS, 481 F.3d 1224 (9th Cir. 2007) |

|

June 13, 2007 |

District court in Washington found that NMFS's downlisting of Columbia River steelhead due to hatchery listing policy (HLP) violated the ESA, and set aside the HLP. |

Trout Unlimited v. Lohn, 2007 WL 1795036 (W.D. Wash. June 13, 2007) |

|

August 14, 2007 |

District court upheld NMFS listing (even though entire ESU is given same listing status, NMFS considered effects on hatchery & wild salmon separately). |

Alsea Valley Alliance v. Lautenbacher, No. 06 6093 HO (D. Or. August 14, 2007) |

|

August 21, 2007 |

Action agencies issued a biological assessment for effects of the FCRPS. |

Available onlined |

|

Reclamation issued a biological assessment on operations and maintenance of Upper Snake River Basin Projects above Brownlee Reservoir. |

Available onlinee |

|

|

October 31, 2007 |

NMFS released a draft revised BiOp on operation of the FCRPS and Upper Snake projects for salmon and steelhead. |

Superseded by the final BiOp on operation of the FCRPS, Upper Snake projects, and harvest of salmon and steelhead, issued May 5, 2008 |

|

February 25, 2008 |

The court ordered that the FCRPS would be operated pursuant to the 2008 Fish Operations Plan until the 2008 BiOp was finished in August, 2008. |

National Wildlife Federation v. NMFS, No. 01-640-RE (D. Or. February 25, 2008) |

|

March 24, 2008 |

NMFS authorized Washington, Oregon, and Idaho to use lethal force on no more than 85 California sea lions identified as preying on migrating salmonids. |

73 Fed. Reg. 15,483 |

|

April 24, 2008 |

Ninth Circuit amended its April 2007 decision to clarify that the Supreme Court decision in Nat'l Ass'n of Homebuilders v. Defenders of Wildlife, 127 S. Ct. 2581 (2007), did not alter its ruling. |

National Wildlife Federation v. NMFS, 524 F.3d 917 (9th Cir. 2008) |

|

May 2, 2008 |

Action agencies reach memoranda of understanding with Columbia Basin tribes and the states of Idaho and Montana |

Available onlinef |

|

May 5, 2008 |

NMFS released the final BiOp on operation of the FCRPS, Upper Snake projects, and harvest of salmon and steelhead. |

Available onlineg |

|

March 16, 2009 |

Ninth Circuit reversed lower court by upholding NMFS hatchery listing policy regarding steelhead, including downlisting the fish. Hatchery and natural fish can be same ESU but still considered separately for listing purposes. Ninth Circuit affirmed that NMFS policy rightly distinguished between hatchery and natural salmon in the listing process. |

Trout Unlimited v. Lohn, 559 F.3d 946 (9th Cir. 2009); Alsea Valley Alliance v. Lautenbacher, 319 Fed. Appx. 588 (9th Cir. 2009) |

|

August 24, 2009 |

NMFS reclassified Upper Columbia River steelhead trout as threatened in response to March 16, 2009, court decision. |

74 Fed. Reg. 42605 |

|

September 16, 2009 |

Action agencies execute memorandum of understanding with the state of Washington |

Available onlineh |

|

May 20, 2010 |

NMFS submitted Supplemental Biological Opinion to 2008 BiOp. |

Available onlinei |

|

November 23, 2010 |

Ninth Circuit rejected NMFS authorization for Washington and Oregon to take up to 85 sea lions. |

Humane Society of the United States v. Locke, 626 F.3d 1040 (9th Cir. 2010) |

|

May 18, 2011 |

NMFS issued Letter of Authorization to Washington and Oregon for lethal takes of up to 85 California sea lions. |

76 Fed. Reg. 28,733h |

|

July 22, 2011 |

NMFS notified Washington and Oregon that Letter of Authorization to use lethal force against California sea lions is revoked effective July 27, 2011. |

Available onlinej |

|

August 2, 2011 |

District court rejected 2010 Supplemental Biological Opinion to 2008 BiOp. |

National Wildlife Federation v. NMFS, No. 01-640-RE (D. Or. August 2, 2011) |

|

September 12, 2011 |

NMFS announced receipt of application by Washington, Oregon, and Idaho to take California sea lions near the Bonneville Dam. |

76 Fed. Reg. 56,167 |

|

March 15, 2012 |

NMFS announces Letter of Authorization for Idaho, Oregon, and Washington to use lethal force against California sea lions through May 2016. |

Available onlinek |

|

January 17, 2014 |

NMFS submitted second Supplemental Biological Opinion to 2008 BiOp. |

Available onlinem |

|

January 27, 2016 |

Idaho, Oregon, and Washington seek five-year extension of NMFS authorization to lethally remove California sea lions. |

Available onlinen |

|

May 4, 2016 |

District court rejected 2014 Supplement to the 2008 BiOp. |

National Wildlife Federation v. NMFS, No. 3:01-cv-00640, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 59195 (D. Or. May 4, 2016) |

|

June 30, 2016 |

NMFS approves the states' request for a five-year extension of a letter of authorization to lethally remove California sea lions. |

81 Fed. Reg. 44,298 |

Source: Congressional Research Service, based on sources cited below and in Figure 1.

a. https://pcts.nmfs.noaa.gov/pls/pcts-pub/sxn7.pcts_upload.summary_list_biop?p_id=12342.

b. http://www.bpa.gov/corporate/pubs/rods/2005/EFW/BPA_Decision_Document_BiOp.pdf.

c. http://www.fws.gov/idaho/publications/BOs/Final.pdf.

d. http://www.salmonrecovery.gov/Files/BiologicalOpinions/BA_MAIN_TEXT_FINAL_08-20-07_Updated_08-27.pdf.

e. http://www.usbr.gov/pn/programs/UpperSnake/index.html.

f. http://www.salmonrecovery.gov/Partners/FishAccords.aspx.

g. http://www.nwr.noaa.gov/Salmon-Hydropower/Columbia-Snake-Basin/final-BOs.cfm.

h. http://www.salmonrecovery.gov/Files/Partners/Estuary%20Habitat%20MOA%209-16-09.pdf.

i. http://www.nwr.noaa.gov/Salmon-Hydropower/Columbia-Snake-Basin/final-BOs.cfm.

j. http://www.nwr.noaa.gov/Marine-Mammals/Seals-and-Sea-Lions/upload/Sec-120-LOA-withdraw.pdf.

k. http://www.nwr.noaa.gov/Newsroom/Current/upload/03-15-2012.pdf.

l. http://www.nwr.noaa.gov/Marine-Mammals/Seals-and-Sea-Lions/upload/Sec-120-LOA-withdraw.pdf.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Retired CRS specialist Gene Buck made important contributions to this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

Idaho ex rel. Evans v. Oregon, 462 U.S. 1017, 1019-20 (1983). |

| 2. |

See id. at 1020 ("Since 1938, the already arduous voyages of these fish have been complicated by the construction of eight dams on the Columbia and Snake Rivers.") |

| 3. |

See id. |

| 4. |

See Federal Columbia River Power System (FCRPS), Bonneville Power Admin, http://www.bpa.gov/power/pgf/hydrPNW.shtml (providing background on FCRPS). |

| 5. |

See id; see also Aluminum Co. of Am. v. Bonneville Power Admin., 175 F.3d 1156, 1158 (9th Cir. 1999). |

| 6. |

Salmon stocks are described in terms of evolutionarily significant units, or ESUs. NMFS defines an ESU as a population or group of populations that is considered distinct for purposes of conservation under the ESA. To qualify as an ESU, a population must (1) be reproductively isolated from other populations within the same species, and (2) represent an important component in the evolutionary legacy of the species. See Policy of Applying the Definition of Species under the Endangered Species Act to Pacific Salmon, 56 Fed. Reg. 58,612 (November 20, 1991). Steelhead stocks are described in terms of distinct population segments (DPSs). The definition of a species in the ESA includes any subspecies of fish or wildlife or plants, or any DPS of any species of vertebrate fish or wildlife which interbreeds when mature. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service DPS policy is provided at 61 Fed. Reg. 4722 (February 7, 1996). |

| 7. |

See National Marine Fisheries Service, West Coast Salmon Recovery Planning & Implementation, available at http://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/protected_species/salmon_steelhead/recovery_planning_and_implementation/. There are other ESA-listed species in the Columbia River Basin, such as lamprey, sturgeon, and stellar sea lions, that are not addressed in this report. |

| 8. |

NMFS, also known as NOAA Fisheries, is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). |

| 9. |

Nat'l Marine Fisheries Serv., Factors for Decline: A Supplement to the Notice of Determination for Snake River Fall Salmon under the Endangered Species Act 3 (June 1991) (referencing a 1987 study by the Northwest Power Planning Council) (hereinafter Fall Salmon Decline 1991 Supplement). |

| 10. |

See id. at 5. |

| 11. |

See 16 U.S.C. §1536(a). The ESA is codified in 16 U.S.C. §§1531-1544. For more information on the ESA generally, see CRS Report RL31654, The Endangered Species Act: A Primer, by M. Lynne Corn. |

| 12. |

See 16 U.S.C. §1536(a)(2); see also Nat'l Ass'n of Home Builders v. Defs. of Wildlife, 551 U.S. 644, 652 (2007) (discussing the consultation process); Paul Boudreaux, Understanding "Take" in the Endangered Species Act, 34 Ariz. St. L.J. 733, 735 (2002) ("[T]he ESA ... requires that federal agencies 'insure' that their actions are not likely to 'jeopardize' the continued existence of ESA-protected species. The insurance is created primarily through required 'consultation' with expert federal wildlife agencies[.]"). The ESA's implementing regulations, which define the consultation process, are set forth in 50 C.F.R. §§402.10-402.16. |

| 13. |

See 16 U.S.C. §1536(a)(2) (requiring federal agencies to consult with the Secretary of the Interior to ensure their actions are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered or threated species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of habitat). |

| 14. |

Anglers Conservation Network v. Pritzker, 809 F.3d 664, 666 (D.C. Cir. 2016). |

| 15. |

Andrus v. Sierra Club, 442 U.S. 347, 352 (1979). |

| 16. |

See 50 C.F.R. §402.01(b) (dividing administrative authority under the ESA between FWS and NMFS). |

| 17. |

See Aluminum Co. of Am. v. Bonneville Power Admin., 175 F.3d 1156, 1158 (9th Cir. 1999); see also Endangered and Threatened Marine Species Under NMFS' Jurisdiction, Nat'l Marine Fisheries Serv., June 30, 2016, http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/esa/listed.htm#mammals. |

| 18. |

See Aluminum Co. of Am., 175 F.3d at 1158-59; see also 16 U.S.C. §1536(a)(2) ("Each Federal agency shall, in consultation with and with the assistance of the Secretary, insure that any action authorized, funded, or carried out by such agency ... is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered species or threatened species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of habitat of such species[.]"). |

| 19. |

See Nat'l Wildlife Fed'n v. Nat'l Marine Fisheries Serv., No. 3:01-cv-00640, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 59195, at *41-42 (D. Or. May 4, 2016). |

| 20. |

See 16 U.S.C. §1536(c); see also 50 C.F.R. §402.02 (defining biological assessment). |

| 21. |

See 50 C.F.R. §402.16(b)-(d). |

| 22. |

See 16 U.S.C. §1536(b)(3)(A) ("Promptly after conclusion of consultation ... the Secretary shall provide to the Federal agency and the applicant, if any, a written statement setting forth the Secretary's opinion, and a summary of the information on which the opinion is based, detailing how the agency action affects the species or its critical habitat."); see also sources cited supra note 17 (discussing the delegation of authority by the Secretary of the Interior to NMFS). |

| 23. |

See 16 U.S.C. §1536(b)(3)(A) (requiring the BiOp to "detail[] how the agency actions affects the species or its critical habitat"); 50 C.F.R. §402.14(h) ("The biological opinion shall include ... [t]he Service's opinion on whether the action is likely to jeopardize the continued existence of a listed species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat (a 'jeopardy biological opinion'); or, the action is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of a listed species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat (a 'no jeopardy' biological opinion)."). |

| 24. |

See 16 U.S.C. §1536(b)(3)(A) ("If jeopardy or adverse modification is found, the Secretary shall suggest those reasonable and prudent alternatives which he believes would not [jeopardize the listed species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of habitat] and can be taken by the [action] agency or applicant in implementing the agency action."); 50 C.F.R. §402.14(h)(3) ("A 'jeopardy' biological opinion shall include reasonable and prudent alternatives, if any."). |

| 25. |

See 16 U.S.C. §1536(b)(4); 50 C.F.R. §402.14(i). See also Bennett v. Spear, 520 U.S. 154, 158 (1997) (explaining that the written statement required under 16 U.S.C. §1536(b)(4) is known as an "Incidental Take Statement"). |

| 26. |

See Bennett, 520 U.S. at 170 ("[T]he Biological Opinion's Incidental Take Statement constitutes a permit authorizing the action agency to 'take' the endangered or threatened species so long as it respects the Service's 'terms and conditions.'"). |

| 27. |

See id. ("'[A]ny person' who knowingly 'takes' an endangered or threatened species is subject to substantial civil and criminal penalties[.]") (quoting 16 U.S.C. §1540); San Luis & Delta-Mendota Water Auth. v. Locke, 776 F.3d 971, 988 (9th Cir. 2014) ("[T]he BiOp ... [and] incidental take statement ... permit[] the action agency to harm listed species ... without violating the ESA[.]") (citing 50 C.F.R. §402.02). |

| 28. |

A "salmonid" is a soft-finned, elongated fish with an upturned final vertebrae. Marsh v. Or. Nat'l Resources Council, 490 U.S. 360, 366 n.6 (1989) (citing Webster's Third International Dictionary 2004 (1981)). Salmon and trout are two common salmonids. Id. |

| 29. |

See infra "2005 Snake River BiOp" |

| 30. |

Nat'l Marine Fisheries Serv., Endangered Species Act Section 7(a)(2) Consultation Biological Opinion and Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act Essential Fish Habitat Consultation (May. 5, 2008), available at https://pcts.nmfs.noaa.gov/pcts-web/dispatcher/trackable/NWR-2008-2406?overrideUserGroup=PUBLIC&referer=/pcts-web/publicAdvancedQuery.pcts?searchAction=SESSION_SEARCH. |

| 31. |

See Nw. Res. Info. Ctr. v. Nw. Power Planning Council, 35 F.3d 1371, 1375 (9th Cir. 1994) (describing the competing interests in the Columbia River Basin as a "classic struggle between environmental and energy interests" in "what has been outed as the world's largest program of biological restoration"), cert denied, 568 U.S. 806 (1995); Pac. Nw. Generating Coop. v. Brown, 38 F.3d 1058, 1060 (9th Cir. 1994) ("Salmon and waterpower, the two great natural resources of the Columbia River Basin, have been in tension with each other for over half a century as they have been put to use by human hands and mouths."). |

| 32. |

Robert T. Lackey et al., Policy Options to Reverse the Decline of Wild Pacific Salmon, Fisheries, July 2006, at 344-351. |

| 33. |

See Lisa Crozier, Impacts of Climate Change on Salmon in the Pacific Northwest, A Review of Scientific Literature Published in 2014 (2015), available at https://www.nwfsc.noaa.gov/assets/4/8466_12112015_134746_Literature_Review_%20Impacts_of_Climate_Change_on_Salmon_2014.pdf. |

| 34. |

Conservation of Columbia Basin Fish, Final Basinwide Salmon Recovery Strategy (December 2000), available at http://www.salmonrecovery.gov/Files/BiologicalOpinions/2000/2000_Final_Strategy_Vol_1.pdf; see also Brown, 38 F.3d at 1066 (describing "[w]hat may be called 'the 4-H's'"). |

| 35. |

Nat'l Marine Fisheries Serv., Endangered Species Act Section 7(a)(2) Supplemental Biological Opinion, Consultation on Remand for Operation of the Federal Columbia River Power System 36 (January 14, 2014) [hereinafter "2014 Supplement"], available at http://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/publications/hydropower/fcrps/2014_supplemental_fcrps_biop_final.pdf. |

| 36. |

Id. at 36. |

| 37. |

Stellar sea lions also are found in the area and consume salmon, but generally in smaller numbers. No authorization for their removal has been proposed. |

| 38. |

Predation on Salmon and Steelhead Below Bonneville Dam: January-May, Wash. Dep't of Fish & Wildlife, http://wdfw.wa.gov/conservation/sealions/predation.html (last visited July 19, 2016). |

| 39. |

Fish Field Unit, U.S. Army Corps of Eng'rs, 2015 Field Report: Evaluation of Pinniped Predation on Adult Salmonids and Other Fish in the Bonneville Dam Tailrace 2 (March 2016), available at http://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/publications/protected_species/marine_mammals/pinnipeds/sea_lion_removals/2015__coe_field_rpt.pdf. |

| 40. |

See infra "Litigation over Authorization to Euthanize California Sea Lions." Section 120 of the Marine Mammal Protection Act allows a state to seek authorization from the Secretary of NOAA for the lethal taking of sea lions (or other pinnipeds) which have a significant negative impact on the decline or recovery of salmonid fishery stocks that have been listed as threatened or endangered under the ESA. See 16 U.S.C. §1389(b)(1). Pinnipeds are aquatic carnivorous mammals with fins, and include sea lions, walruses, and seals. See Humane Soc'y v. Bryson, 924 F. Supp. 2d 1228, 1232 (D. Or. 2013), aff'd, Humane Soc'y v. Pritzker, 548 Fed. Appx. 355 (2013). |

| 41. |

See infra "Litigation over Authorization to Euthanize California Sea Lions." |

| 42. |

Pikeminnow Sport-Reward Program, 2016 Northern Pikeminnow Sport-Reward Program, http://www.pikeminnow.org/ (last visited August 4, 2016). |

| 43. |

Id. |

| 44. |

NMFS manages the ocean salmon fishery that is composed of a mixture of salmon from different systems including the Columbia Basin. |

| 45. |

Or. Dep't of Fish and Wildlife & Wash. Dep't of Fish and Wildlife, 2016 Non-Indian Columbia River Summer/Fall Fishery Allocation Agreement (May 31, 2016), available at http://wdfw.wa.gov/fishing/northfalcon/2016/2016_allocation_agreement.pdf. |

| 46. |

Columbia River Working Gp., Wash. Dep't of Fish and Wildlife, Selective Fisheries (October 2008), available at https://www.co.clatsop.or.us/sites/default/files/fileattachments/fisheries/page/521/selective_fishingoct08.pdf. |

| 47. |

See Hatchery Sci. Review Group, Report to Congress on the Science of Hatcheries: An Updated Perspective on the Role of Hatcheries in Salmon and Steelhead Management in the Pacific Northwest 2 (June 2014), available at http://www.hatcheryreform.us/hrp/reports/hatcheries/downloads/Report%20to%20Congress%20on%20Hatchery%20Science_HSRG_June%202014.pdf. |

| 48. |

Nat'l Oceanic and Atmospheric Admin., Dep't of Commerce, Policy on the Consideration of Hatchery-Origin Fish in Endangered Species Act Listing Determinations for Pacific Salmon and Steelhead: Final Policy, 70 Fed Reg. 37,204 (June 28, 2005). |

| 49. |

See John Harrison, Fish Passage at Dams, Northwest Power and Conservation Council (October 31, 2008), http://www.nwcouncil.org/history/FishPassage.asp. |

| 50. |

See Pacific Northwest Electric Power Planning and Conservation Act, P.L. 96-501, 94 Stat. 2697 (1980) (codified at 16 U.S.C. §839). |

| 51. |

See Am. Rivers v. Nat'l Marine Fisheries Serv., 126 F.3d 1118, 1120 (9th Cir. 1997). |

| 52. |

In 1992, it was estimated that overflow operations increased costs of BPA power supply by $60 million. Pac. Nw. Generating Coop. v. Brown, 822 F. Supp. 1479, 1485 (D. Or. 1993). |

| 53. |

See K.E. McGrath, E. M. Dawley, & D.R. Geist, Total Dissolved Gas Effects on Fishes of the Lower Columbia River 10 (2006), available at http://www.pnl.gov/main/publications/external/technical_reports/PNNL-15525.pdf. |

| 54. |

John Harrison, Dams: Impacts on Salmon and Steelhead, Northwest Power and Conservation Council, (October 31, 2008), http://www.nwcouncil.org/history/damsimpacts. |

| 55. |

See Save Our Wild Salmon Coalition, Revenue Stream, An Economic Analysis of the Costs and Benefits of Removing the Four Dams on the Lower Snake River 3-12 (2009), available at http://www.wildsalmon.org/facts-and-information/the-solutions/revenue-stream.html. |

| 56. |

Bonneville Power Admin., Fact Sheet, Power Benefits of the Lower Snake River Dams 1 (January 2009), available at https://www.bpa.gov/news/pubs/FactSheets/fs200901-Power%20benefits%20of%20the%20lower%20Snake%20River%20dams.pdf. |

| 57. |

Condit, Project Overview, Pacifcorp.com, http://www.pacificorp.com/condit# (last visited July 15, 2016). |

| 58. |

M. Brady Allen, et al., Salmon and Steelhead in the White Salmon River after the Removal of Condit Dam - Planning Efforts and Recolonization Results, Fisheries (April 2016), at 190-203. |

| 59. |

See infra pp. 9-16. |

| 60. |

See supra "Consultation and Biological Opinions." |

| 61. |

See, e.g., 2014 Supplement, supra note 35, §3 (describing proposed RPAs for FCRPS operations through 2018). |

| 62. |

See 5 U.S.C. §441, et seq. |

| 63. |

5 U.S.C. §706(2)(A). |

| 64. |

Motor Vehicle Mfrs. Ass'n of U.S. v. State Farm Mut. Auto Ins. Co., 463 U.S. 29, 43 (1983) (quoting Burlington Truck Lines, Inc. v. United States 371 U.S. 156, 168 (1962)). |