Federal Reserve: Recent Repo Market Intervention

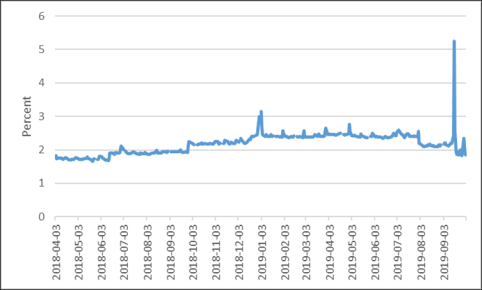

This Insight examines the Federal Reserve's (Fed's) recent intervention in the repo (repurchase agreement) market in response to a sudden and brief spike in repo rates to almost 10% (see Figure 1).

|

2018-2019 |

|

|

Source: St. Louis Fed, FRED. Note: As measured by the Secured Overnight Financing Rate. |

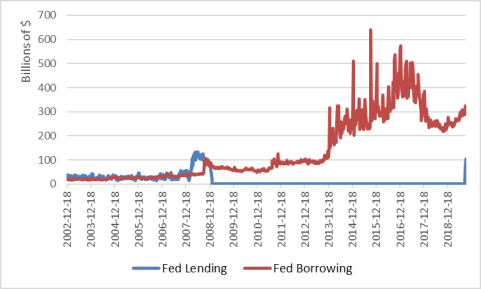

After a short blip, the Fed stabilized financial conditions by offering up to $250 billion in repo markets. This was the first time it has lent in repo markets—although it has regularly borrowed in repo markets—since the financial crisis (see Figure 2).

Background

In a repo, one party sells a security (such as a Treasury security) and then repurchases it at a higher price on a pre-specified date. Repos are an important source of short-term liquidity for financial institutions and are economically equivalent to collateralized loans. For depository institutions (such as banks), another important source of short-term liquidity is the federal funds market, where they borrow and lend each other bank reserves. The interest rate in this market, the federal funds rate (FFR), is the Fed's primary target for monetary policy. Because these private markets are similar, their rates are typically very close.

Although any individual bank chooses how many reserves it will hold, the Fed, counterintuitively, controls the overall level of bank reserves. Before the 2007-2009 financial crisis, the Fed kept the level of bank reserves relatively low and targeted the FFR through open market operations—primarily by using repos (see Figure 2). When it wanted to increase reserves and put downward pressure on the FFR, the Fed lent cash in the repo market. When it wanted to do the opposite, it borrowed cash in the repo market. Because demand for reserves shifts frequently, the Fed continually adjusted its repo activity to keep the FFR stable.

|

2002-2019 |

|

|

Source: St. Louis Fed, FRED. |

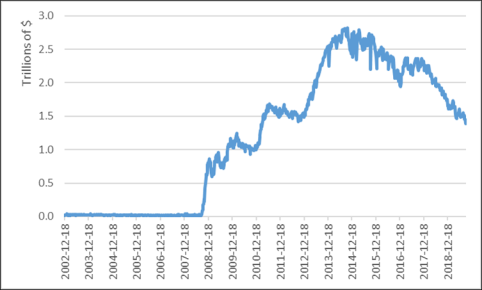

The Fed's method of targeting the FFR changed after the financial crisis. As a result of crisis-response programs, such as quantitative easing, the Fed expanded the level of bank reserves from less than $50 billion to as high as $2.7 trillion (see Figure 3). The Fed could no longer target the FFR using repos because reserves were so abundant there was little need to borrow them, so the market clearing interest rate was zero. Instead, the Fed began paying banks interest on reserves to target the FFR.

|

Figure 3. Bank Reserves Held at the Fed 2002-2019 |

|

|

Source: St. Louis Fed, FRED. |

In 2014, the Fed began to "normalize" monetary policy, including gradually reducing bank reserves from over $2.5 trillion to around $1.5 trillion. Instead of returning to the precrisis model of scarce reserves, it aimed to keep reserves just abundant enough that repos would not be needed to target the FFR. Because of the many changes in market conditions and regulation since the crisis, it was uncertain what level of reserves was "just enough." Events in September suggest that, in unusual circumstances, the current level of reserves is not high enough to preclude the need for open market operations.

What Caused the Recent Spike?

There is no indication that the recent spike in repo rates was caused by a panic; instead, it was caused by a temporary increase in demand for cash and decrease in supply of bank reserves. First, federal tax payments were due on September 15. When taxes are paid, money is initially transferred out of the reserve account of the taxpayer's bank into the Treasury's account at the Fed. Second, relatively large Treasury debt issuance at that time similarly transferred money out of the reserve account of banks (who purchased the securities for themselves or customers) and into the Treasury's account. Finally, financial reporting requirements at the end of the third quarter made banks temporarily less willing to lend in the repo market.

Policy Issues

These events highlight several issues stemming from post-crisis monetary policy and financial regulatory changes.

For monetary policy, the Fed has three options to ensure FFR stability:

- 1. It can use ad hoc repo interventions (like the recent ones) as needed.

- 2. It can purchase assets to increase bank reserves to the point where the supply of reserves always exceeds demand and repos are unnecessary.

- 3. It can create a standing repo facility, where financial firms can borrow cash on demand, setting a rate on the facility that would put a ceiling on repo rates. (During the normalization process, it created a similar facility that puts a floor on repo rates called the Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreement Facility, where financial firms can lend the Fed cash on demand.) Many foreign central banks operate this type of facility.

All three approaches—which are not mutually exclusive—have advantages and disadvantages.

Some view recent events as suboptimal, although such ad hoc interventions were widely accepted as the standard way to conduct monetary policy before the crisis. Monetary policy, by nature, involves some form of market intervention. A drawback to this approach is greater volatility in interest rates than under options two and three; while this is undesirable for affected financial firms, it is less obviously problematic for the broader economy.

A larger level of reserves means that the Fed would hold a larger share of the federal debt on its balance sheet and pay more interest to banks on reserves, which some see as undesirable. Furthermore, the rate of interest that the Fed paid to banks was unavoidably higher relative to the FFR when bank reserves were higher, which some have characterized as a subsidy to banks. Finally, abundant reserves have reduced activity in the federal funds market, reducing the economic significance of the FFR.

Creating a standing repo facility would take the guesswork out of FFR targeting, thereby allowing the Fed to maintain a lower level of reserves while experiencing less interest rate volatility. However, this would have a greater impact on how that private market functions, and it could create private borrower dependence on the Fed. It is questionable why such a facility would be desirable when the Fed has discouraged banks from borrowing at its discount window, whose purpose is also to allow banks to avoid reserve shortfalls.

For regulation, post-crisis reforms may have made large banks less willing to lend in short-term markets. For example, the Liquidity Coverage Ratio requires banks to hold a minimum level of liquid assets, including reserves. Less willingness to lend could result in greater rate volatility. In this sense, such reforms could make banks safer while making financial markets more fragile. But fragility in repo markets can be contained as long as the Fed is willing to intervene.