U.S. Foreign Aid to the Middle East and North Africa: The President’s FY2018 Request

As the largest regional recipient of U.S. economic and security assistance, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is perennially a major focus for Congress.

|

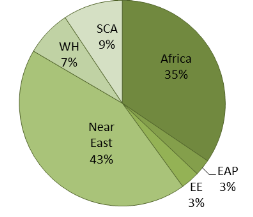

Figure 1. FY2018 Foreign Operations Request, by Region |

|

|

Source: Data for this figure is from FY2018 budget roll-out documents provided by the State Department. It does not include administrative funds, MCC, humanitarian assistance, or food aid. Note: WH = Western Hemisphere; SCA = South Central Asia; EE = Europe and Eurasia; EAP = East Asia and Pacific. |

For FY2018, the Trump Administration proposes to cut 12% of overall bilateral aid to the Middle East and North Africa (from FY2016 enacted levels), primarily by ending Foreign Military Financing (FMF) grants to Bahrain, Iraq, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, and Tunisia. However, these countries may continue to receive grant or loan aid from a proposed $200 million FMF "global fund," possibly convert from FMF grants to FMF loans beginning in FY2018, or receive no FMF assistance at all. U.S. security assistance to MENA countries could also be channeled through Defense Department appropriations accounts rather than through State Department and Foreign Operations appropriations.

If enacted, the Administration's FY2018 proposed cuts to FMF for the region would make the traditional recipients of FMF grants (Israel, Egypt, and Jordan) account for 100% of all regional FMF grant aid and 92% of all global grant FMF aid.

While the President's FY2018 budget request claims that FMF loans will allow recipients to "purchase more American-made defense equipment and related services than they would receive with the same amount of grant funding," some lawmakers argue that converting FMF grants to loans would "require poorer countries to reimburse the United States (which past experience has shown they are unable to do) for assistance that is in our security interest to provide to them."

|

FMF Grants and Loans As President Trump's FY2018 budget request proposes converting more FMF grants to loans, it is worth noting that throughout the decades following World War II, U.S. foreign military aid has generally fluctuated between grant aid and loans. In general, following World War II, most U.S. military aid to foreign recipients was provided as grant assistance. In the early 1970s, Congress began to shift grant aid to loans. In the mid to late 1980s, as more loan recipients had difficulty meeting their debt obligations to the United States due to high interest rates on their Foreign Military Sales (FMS) credits, Congress began a program of debt forgiveness and returned to making FMF grants instead of loans. Following Egypt's participation in the U.S.-led multinational coalition against Iraq in 1990-1991, Congress passed P.L. 101-513, the Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 1991. That law included Section 592 which laid out the conditions authorizing the President to forgive Egypt's military debt, which it had accrued throughout the 1980s. Over time, some Members of Congress have argued that if vital U.S. security interests are at stake, then the United States should be prepared to provide grant assistance, while others have sought to ensure that U.S. partners capable of paying for U.S. support do so. The 2017 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 115-31) includes a reporting requirement assessing the potential impact of transitioning FMF assistance from grants to loans, including "the budgetary and diplomatic impacts, and the extent to which such transition would affect the foreign policy interest of the United States." |

The FY2018 budget would provide Israel with $3.1 billion in FMF, which the Congressional Budget Justification notes marks the final year of the U.S. commitment to Israel under the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) covering FY2009-FY2018. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31) appropriated $75 million in FMF for Israel in FY2017 beyond the $3.1 billion identified for FY2017 in the MOU, and there is some uncertainty over the status of this "extra" FMF to Israel. During negotiations over a new MOU covering FY2019-FY2028, the Obama Administration and the Israeli government reportedly reached an understanding that Israel would "return" to the U.S. government any FMF appropriated beyond the MOU amounts specified for FY2017 or FY2018. Some lawmakers have argued that since foreign assistance is subject to the approval of Congress, the MOU is nonbinding, and it is possible that Members may appropriate FMF to Israel beyond the FY2018 request.

Like Israel, Jordan also has a bilateral MOU on U.S. assistance, except that in Jordan's case the current MOU expires in FY2018, and no new deal has been reached. The FY2018 total request for Jordan is $1 billion (in military and economic aid), which, according to the Department of State and USAID's Budget Overview, "demonstrates U.S. commitment to Jordan by providing ongoing support consistent with the previous FY 2015-FY 20I7 Memorandum of Understanding level of $1 billion per year."

Under the President's FY2018 request, total U.S. bilateral aid to Iraq (channeled through the State Department) would drop 14% from FY2016 enacted levels due primarily to the absence of a request for FMF to Iraq. In FY2016, Iraq received $250 million in FMF, which was applied to the subsidy cost for a $2.7 billion FMF loan. P.L. 115-31, the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2017, also provided $250 million in FMF to Iraq. Iraq also receives substantial security assistance from the Department of Defense-administered Iraq Train and Equip Fund (ITEF)/Counter-ISIL Train and Equip Fund (CTEF).

The President does seek to more than double ESF to Iraq ($300 million requested in FY2018/$122.5 million enacted in FY2016) for postconflict stabilization in areas liberated from the Islamic State. Iraq also may receive a substantial amount of FY2017 ESF appropriated in either P.L. 114-254, the Further Continuing and Security Assistance Appropriations Act, 2017 (which provided $1.03 billion in ESF in bilateral aid to various countries and for programs to counter ISIL) or P.L. 115-31, the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2017.

Table 1. U.S. Bilateral Aid to MENA Countries: FY2016-FY2018 Request

|

Country |

FY2016 Obligated |

FY2017 Supplemental (P.L. 114-254) |

FY2017 Omnibus (P.L. 115-31) |

FY2018 Request |

|

Israel |

3,100.000 |

— |

3,175.000 |

3,100.000 |

|

Egypt |

1,448.950 |

— |

1,419.300 |

1,381.300 |

|

Jordan |

1,274.933 |

ESF/FMF authorized |

1,279.950 |

1,000.000 |

|

Iraq |

405.353 |

ESF authorized (and other accounts) |

250.000 (+ amounts unspecified) |

347.860 |

|

West Bank/Gaza |

261.341 |

— |

60.000 (+ amounts unspecified) |

251.000 |

|

Lebanon |

213.457 |

— |

2.000 (+ amounts unspecified) |

103.820 |

|

Yemen |

203.397 |

— |

— |

35.000 |

|

Syria |

177.144 |

ESF authorized (and other accounts) |

25.000 (+ amounts unspecified) |

191.500 |

|

Tunisia |

141.850 |

ESF/FMF authorized |

165.4000 |

54.600 |

|

Morocco |

31.735 |

— |

38.500 |

16.000 |

|

Libya |

18.500 |

— |

31.000 |

|

|

Bahrain |

5.816 |

— |

— |

.800 |

|

Oman |

5.416 |

— |

— |

3.500 |

|

Algeria |

2.591 |

— |

— |

1.800 |

Notes: Countries may still receive funding not specified in appropriations laws through the allocation process as defined in Section 653a of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 as amended.

Source: Congressional Budget Justification FY2018 State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs and Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying P.L. 115-31.