Introduction

This report provides background information and analysis on the following topics:

- Turkey's strategic orientation—including toward the United States and Russia—as affected by ongoing regional developments, the U.S./NATO presence in Turkey, and Turkish defense procurement decisions such as the purchase of a Russian S-400 surface-to-air defense system;

- points of tension between the United States and Turkey, including specific issues of U.S. concern and sanctions or other measures against Turkey;

- Turkey's efforts to manage threats and influence outcomes in Syria, including its occupation of some northern Syrian areas to thwart Syrian Kurds partnering with the U.S. military from gaining autonomy; and

- domestic Turkish political and economic developments under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's largely authoritarian and polarizing rule, including those connected to the global COVID-19 outbreak.

For additional information, see CRS Report R41368, Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas. See Figure A-1 for a map and key facts and figures about Turkey.

Turkey's Strategic Orientation

Overview

Numerous points of tension have raised questions within the United States and Turkey about the two countries' alliance, as well as Turkey's commitment to NATO and its Western orientation. Nevertheless, U.S. and Turkish officials maintain that bilateral cooperation on a number of issues—including regional security and counterterrorism—remains mutually important.1

Concerns among Turkish leaders that U.S. policy might hinder Turkey's security date back at least to the 1991 Gulf War,2 but the following developments have fueled them since 2010:

- Close U.S. military cooperation against the Islamic State with Syrian Kurdish forces linked to the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), a U.S.-designated terrorist organization that has waged an on-and-off insurgency against the Turkish government since the 1980s while using safe havens in both Syria and Iraq.

- Turkey's view that the United States supported or acquiesced to events during post-2011 turmoil in Egypt and Syria that undermined Sunni Islamist figures tied to Turkey.

- Many Western leaders' criticism of President Erdogan for ruling in a largely authoritarian manner. Erdogan's sensitivity to Western concerns was exacerbated by a 2016 coup attempt that Erdogan blames on Fethullah Gulen, a former Turkish imam who leads a worldwide socioreligious movement and lives in the United States.

Turkey has arguably sought a more independent course than at any time since joining NATO in 1952, driven partly by geopolitical and economic considerations. Traditionally, Turkey has relied closely on the United States and NATO for defense cooperation, European countries for trade and investment, and Russia and Iran for energy imports. Turkish leaders' interest in reducing their dependence on the West for defense and discouraging Western influence over their domestic politics may partly explain their willingness to coordinate some actions with Russia in Syria and purchase a Russian S-400 surface-to-air defense system.3 Nevertheless, Turkey retains significant differences with Russia—with which it has a long history of discord—including over political outcomes in Syria and Libya. While Turkey-Russia cooperation on some issues may not reflect a general Turkish realignment toward Russia, Russia may be content with helping weaken Turkey's ties with the United States, NATO, and the European Union (EU) to reduce obstacles to Russian actions and ambitions.4

Turkish leaders appear to compartmentalize their partnerships and rivalries with other global powers as each situation dictates, partly in an attempt to reduce Turkey's dependence on and maintain its leverage with these actors.5 While this approach may to some extent reflect President Erdogan's efforts to consolidate control domestically, it also has precedent in Turkish foreign policy from before Turkey's Cold War alignment with the West.6 Additionally, Turkey's history as both a regional power and an object of great power aggression translates into wide domestic popularity for nationalistic political actions and discourse.

U.S./NATO Presence7

Turkey's location near several global hotspots has made the continuing availability of its territory for the stationing and transport of arms, cargo, and personnel valuable for the United States and NATO. From Turkey's perspective, NATO's traditional value has been to mitigate its concerns about encroachment by neighbors. Turkey initially turned to the West largely as a reaction to aggressive post-World War II posturing by the Soviet Union. In addition to Incirlik Air Base near the southern Turkish city of Adana, other key U.S./NATO sites include an early warning missile defense radar in eastern Turkey and a NATO ground forces command in Izmir (see Figure A-2). Turkey also controls access to and from the Black Sea through its straits pursuant to the Montreux Convention of 1936.

Tensions between Turkey and other NATO members have fueled internal U.S./NATO discussions about the continued use of Turkish bases. As a result of the tensions and questions about the safety and utility of Turkish territory for U.S. and NATO assets, some observers have advocated exploring alternative basing arrangements in the region.8 Some reports suggest that expanded or potentially expanded U.S. military presences in places such as Greece, Cyprus, and Jordan might be connected with concerns about Turkey.9 Several open source media outlets have speculated about whether U.S. tactical nuclear weapons may be based at Incirlik Air Base, and if so, whether U.S. officials might consider taking them out of Turkey.10 A bill introduced in the Senate in October 2019 (S. 2644) would, among other provisions, require the President to provide an interagency report to Congress "assessing viable alternative military installations or other locations to host personnel and assets of the United States Armed Forces currently stationed at Incirlik Air Base in Turkey."

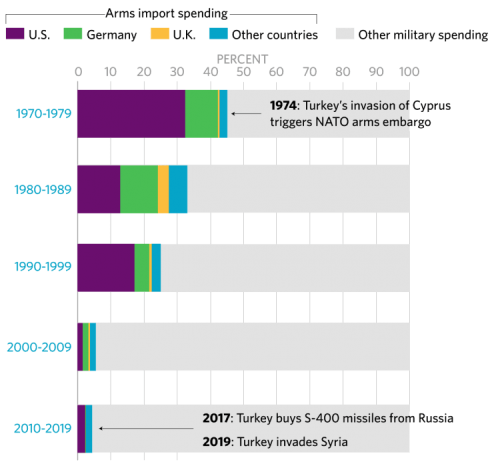

There are historical precedents for such actions. On a number of occasions, the United States has withdrawn military assets from Turkey or Turkey has restricted U.S. use of its territory or airspace. Most prominently, Turkey closed most U.S. defense and intelligence installations in Turkey during the 1975-1978 U.S. arms embargo that Congress imposed in response to Turkey's military intervention in Cyprus.

Assessing costs and benefits to the United States of a U.S./NATO presence in Turkey, and of potential changes in U.S./NATO posture, largely revolves around two questions:

- To what extent does the United States rely on direct use of Turkish territory or airspace to secure and protect U.S. interests?

- How important is U.S./NATO support to Turkey's external defense and internal stability, and to what extent does that support serve U.S. interests?

Turkish Defense Procurement

Background

Turkish goals to become more self-sufficient on national security matters and increase Turkey's arms exports affect the country's procurement decisions. After the 1975-1978 U.S. arms embargo over Cyprus significantly hampered Turkish arms acquisitions, Turkey sought to decrease dependence on foreign sources by building up its domestic defense industry (see Figure A-3).11 Over time, Turkish companies have supplied an increased percentage of Turkey's defense needs, on equipment ranging from armored personnel carriers and naval vessels to drone aircraft. For key items that Turkey cannot produce itself, its leaders generally seek deals with foreign suppliers that allow for greater co-production and technology sharing.12

Procurement and Turkey's Relationships: S-400, F-35, Patriot

How Turkey procures key weapons systems affects its partnerships with major powers. For decades, Turkey has relied on important U.S.-origin equipment such as aircraft, helicopters, missiles, and other munitions to maintain military strength.13 Turkey's purchase of a Russian S-400 surface-to-air defense system and its exploration of possibly acquiring Russian Sukhoi fighter aircraft may raise the question: If Turkey transitions to major Russian weapons platforms with multi-decade lifespans, how can it stay closely integrated with NATO on defense matters?

A number of factors may have influenced Turkey's decision to purchase the S-400 instead of the U.S.-origin Patriot system. One is Turkey's apparent desire to diversify its foreign arms sources.14 Another is Erdogan's possible interest in defending against U.S.-origin aircraft such as those used by Turkish military personnel in the 2016 coup attempt.15

Turkey's general interest (discussed above) in procurement deals that feature technology sharing and co-production also may have affected its S-400 decision. Lack of agreement between the United States and Turkey on technology sharing regarding the Patriot system over a number of years possibly contributed to Turkey's interest in considering other options.16 While Turkey's S-400 purchase reportedly does not feature technology sharing,17 Turkish officials express hope that a future deal with Russia involving technology sharing and co-production might be possible to address Turkey's longer-term air defense needs, with another potential option being Turkish co-development of a system with European partners.18

In response to the beginning of S-400 deliveries to Turkey, the Trump Administration announced in July 2019 that it was removing Turkey from participation in the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program.19 Additionally, Section 1245 of the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 116-92) prohibits the use of U.S. funds to transfer F-35s to Turkey unless the Secretaries of Defense and State certify that Turkey no longer possesses the S-400. Turkey had planned to purchase at least 100 U.S.-origin F-35s and was one of eight original consortium partners in the development and industrial production of the aircraft.20 According to U.S. officials, most of the supply chain handled by Turkish companies was due to move elsewhere by March 2020, with a few contracts in Turkey continuing until later in the year.21 The cost of shifting the supply chain, beyond some production delays,22 was estimated in July 2019 to be between $500 million and $600 million.23

|

U.S. Concerns About Possible F-35 Proximity to the S-400 In explaining the U.S. decision to remove Turkey from the F-35 program, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment Ellen Lord said, "Turkey cannot field a Russian intelligence collection platform [within the S-400 system] in proximity to where the F-35 program makes, repairs and houses the F-35. Much of the F-35's strength lies in its stealth capabilities, so the ability to detect those capabilities would jeopardize the long-term security of the F-35 program."24 A security concern regarding the F-35 could compromise its global marketability and effectiveness.25 While some Russian radars in Syria may have already monitored Israeli-operated F-35s,26 intermittent passes at long ranges reportedly might not yield data on the aircraft as conclusive as the more voluminous data available if an S-400 in Turkey could routinely monitor F-35s.27 One U.S.-based analyst has said that U.S. concerns are "overblown" and that Russian tracking of F-35s in Turkey would not significantly differ from monitoring elsewhere.28 |

Turkey has continued on-and-off discussions with the Administration—including amid Turkey-Russia tensions in Syria in early 2020—about possibly having the United States deploy or sell Patriot surface-to-air defense systems to Turkey.29 Reportedly, U.S. officials seek to condition the use of U.S. Patriot systems in Turkey on Turkish steps to return the S-400 to Russia or to limit its use.30 Since 2013, various NATO countries have stationed air defense batteries in southern Turkey as a means of assisting Turkey during Syria's civil war. The United States removed its contribution of Patriot batteries from Turkey in 2015, explaining the action in terms of its global missile defense priorities but contributing to doubts among Turkish leaders about the U.S. commitment to their security.31 As of April 2020, Spain operates a Patriot system in the Turkish city of Adana under NATO auspices (see Figure A-2).

U.S.-Turkey Tension Points

Issues of U.S. Concern

The following issues involving Turkey raise concerns among U.S. officials and many Members of Congress:

Russia and the S-400 (as discussed above). How the United States responds to Turkey's acquisition of the S-400 air defense system from Russia could affect U.S. arms sales and sanctions with respect to Turkey, as well as other key partners who have purchased or may purchase advanced weapons platforms from Russia—including India, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar.32

Syria and the YPG (see "Syria" below). U.S. concerns regarding Turkish actions in Syria have largely focused on Turkish military operations against the People's Protection Units (Kurdish acronym YPG). The PKK-linked YPG is the leading element in the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which has been the main ground force partner in Syria for the U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State organization (IS, or ISIS/ISIL).

Halkbank and alleged Iran sanctions evasion. In October 2019, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York announced a six-count indictment against Halkbank (a large Turkish bank that is majority-owned by the government) for "fraud, money laundering, and sanctions offenses related to the bank's participation in a multibillion-dollar scheme to evade U.S. sanctions on Iran."33 Halkbank pled "not guilty" in March 2020. The Halkbank indictment is based partly on evidence from the 2017-2018 criminal trial of a Halkbank officer in a U.S. federal court, as well as underlying documents that President Erdogan claimed (while serving as prime minister) were used by the Gulen movement to undermine his government in a 2013-2014 corruption probe in Turkey. Testimony from the trial implicated Erdogan in the sanctions-evasion scheme.34 Some observers have speculated that Turkey's prosecution of three Turkish nationals employed by U.S. consulates may be an effort by Erdogan to gain leverage with the United States in the Halkbank matter.35

Democracy and rule of law in Turkey. Many domestic and international observers allege that Erdogan and other Turkish officials are undermining democracy and the rule of law by unduly influencing elections, improperly controlling the media, exploiting Turkey's legal system to punish political opponents, suppressing civil liberties, and unfairly targeting or repressing Turkey's Kurds and other ethnic and religious minorities.36

Regional rivalries: Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. Turkey's regional ambitions have contributed to difficulties with some of its neighbors that are (like Turkey) U.S. allies or partners. Turkey's dispute with the Republic of Cyprus over Eastern Mediterranean energy exploration arguably has brought the Republic of Cyprus, Greece, Israel, and Egypt closer together.37 The dispute also has prompted Western criticism of Turkey and some EU sanctions against Turkish individuals aimed at discouraging Turkish drilling near Cyprus.38 Turkey, for its part, has called on the Republic of Cyprus to agree to share prospective energy revenue with a Turkey-supported de facto government that administers the northern one-third of the island where Turkish Cypriots form a majority. In late 2019, Turkey signed an agreement with Libya's Government of National Accord (GNA) on maritime boundaries that complicates the political-legal picture in the Eastern Mediterranean—possibly discouraging private sector involvement in Eastern Mediterranean energy exploration and pipelines, and raising difficulties for regional security.39

In the Middle East, Sunni Arab states like Saudi Arabia and Egypt regard Turkey with suspicion, largely because of the Turkish government's Islamist sympathies and close relationship with Qatar.40 One sign of Turkey's rivalry with these Arab states is their support for opposing sides in Libya's civil war.41 Another is the maritime facilities that Turkey has or plans to have in Qatar, Somalia, Sudan, and northern Cyprus.42

Israel and Hamas. Turkey maintains relations with Israel, but previously close ties have become more distant and—at times—contentious during Erdogan's time as prime minister and president. Also, Erdogan's Islamist sympathies have contributed to close Turkish relations with the Palestinian Sunni Islamist militant group Hamas (a U.S.-designated terrorist organization). Some reports claim that some Hamas operatives are located in Turkey and involved in planning attacks on Israeli targets.43 In September 2019, the Treasury Department designated an individual and an entity based in Turkey—under existing U.S. counterterrorism sanctions authorities—for providing material support to Hamas.44

Possible Sanctions and Other Measures

Some U.S. concerns have led to sanctions and other measures against Turkey, and could lead to more in the future. This could, in turn, affect U.S.-Turkey relations more broadly.

Sanctions' effect on Turkish behavior may be difficult to gauge. One financial strategist said in October 2019 that measures constraining Turkish banks from transacting in dollars could particularly affect Turkey's financial system.45 While negative effects on Turkey's economy could lead to domestic pressure to change Turkish policies,46 they also could increase popular support for the government. While Turkey has long-standing, deeply rooted ties with the West, some sanctions could potentially create incentives for Turkey to increase trade, investment, and arms dealings with non-Western actors.47 President Erdogan has stated that U.S. actions against Turkey could lead to the ejection of U.S. military personnel and assets from Turkey.48

Relevant U.S. measures affecting or potentially affecting Turkey include:

CAATSA sanctions in response to the S-400 acquisition. The Turkey-Russia S-400 transaction could trigger the imposition of U.S. sanctions under the Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (CRIEEA, title II of the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, or CAATSA; P.L. 115-44; 22 U.S.C. 9525). Under Section 231 of CAATSA, the President is required to impose sanctions on any party that he determines has knowingly engaged in "a significant transaction with a person that is part of, or operates for or on behalf of, the defense or intelligence sectors of the Government of the Russian Federation."

In July 2019, President Trump reportedly asked a group of Senators for flexibility on sanctions implementation regarding Turkey. He supposedly told the Senators that he was exploring a deal that could allow Turkey to remain in the F-35 program if it (1) agreed not to use the S-400 and (2) acquired a U.S. Patriot surface-to-air defense system.49 At the time, some analysts and former U.S. officials said that Turkey's S-400 acquisition may not be final, or that a verifiable arrangement that prevents S-400 data gathering on the F-35 could allow the two systems to coexist in Turkey.50

If Turkey makes its S-400 batteries operational by April 2020, as President Erdogan has said it would, doing so could trigger further debate or action in Congress. Some Members have insisted that the Administration should already have imposed sanctions under CAATSA.51 In a December 3, 2019, Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing, Christopher Ford, the Assistant Secretary of State for International Security and Nonproliferation, said that the Administration's deliberative process regarding possible CAATSA sanctions against Turkey is underway. Assistant Secretary Ford noted that the United States imposed CAATSA sanctions against China in 2018, roughly eight months after it took possession of Russian S-400-related components and fighter aircraft.52

Sanctions related to Syria. In October 2019, the Trump Administration imposed sanctions on some Turkish cabinet ministries and ministers in response to Turkey's armed incursion against the YPG/SDF in Syria, but lifted them later that same month.53 The sanctions came pursuant to Executive Order (E.O.) 13984, which President Trump signed on October 14 and which remains in effect.54 According to the President, E.O. 13984 authorizes "a broad range of consequences, including financial sanctions, the blocking of property, and barring entry into the United States."55

In late 2019, Congress considered a number of sanctions bills in response to Turkey's incursion into Syria, with the House passing the Protect Against Conflict by Turkey Act (H.R. 4695) on October 29. If Turkey mounts significant future military action against the YPG/SDF in Syria, such a development could fuel more debate in Congress on sanctions against Turkey.

End of arms embargo against Cyprus. Section 1250A of the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 116-92), enacted in December 2019, lifted a 32-year-old arms embargo on U.S. arms sales to the Republic of Cyprus, amid the Turkey-Cyprus tensions over Eastern Mediterranean energy exploration described above.

Reduced U.S.-Turkey cooperation against the PKK. One media report citing U.S. and Turkish officials stated that in response to Turkey's October 2019 military operations against the YPG, the U.S. military stopped drone flights that had been sharing intelligence to help Turkey target PKK locations in northern Iraq for more than a decade.56 According to sources cited in the media report, recent Turkish advances in drone technology had reduced its reliance on the U.S. intelligence sharing effort.57

- House and Senate 2019 resolutions on Armenians. After Turkey's October 2019 military operations, the House and Senate passed nonbinding resolutions (H.Res. 296 in October 2019 and S.Res. 150 in December 2019) characterizing as genocide the killing of approximately 1.5 million Armenians by the Ottoman Empire (Turkey's predecessor state) from 1915 to 1923.58 Turkish officials roundly criticized both resolutions, but did not announce any changes in U.S.-Turkey defense cooperation, despite having threatened to do so in years past in connection with similar proposed resolutions.

Syria59

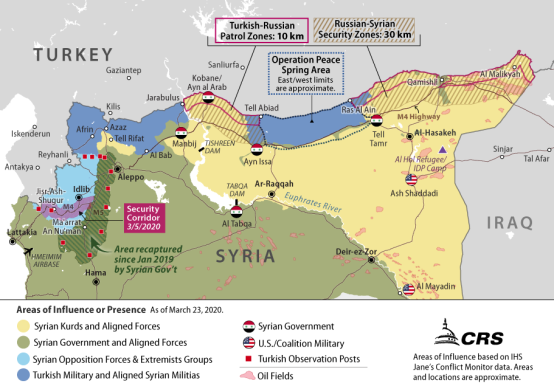

In Syria's ongoing conflict, Turkey seeks to manage and reduce threats to itself and to influence political and security outcomes (see Appendix B for a timeline of Turkey's involvement). Turkish-led forces have occupied and administered parts of northern Syria since 2016 (see Figure A-4). Turkey's chief objective has been to thwart the PKK-linked Syrian Kurdish YPG from establishing an autonomous area along Syria's northern border with Turkey. Turkish-led military operations to that end have included Operation Euphrates Shield (August 2016-March 2017) against an IS-controlled area in northern Syria, and Operation Olive Branch in early 2018 directly against the Kurdish enclave of Afrin.

Turkey has considered the YPG and its political counterpart, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), to be a top threat to Turkish security because of Turkish concerns that YPG/PYD gains have emboldened the PKK in Turkey.60 The YPG/PYD has a leading role within the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—an umbrella group including Arabs and other non-Kurdish elements that became the main U.S. ground force partner against the Islamic State in 2015. Shortly after the YPG/PYD and SDF began achieving military and political success, Turkey-PKK peace talks broke down, tensions increased, and occasional violence resumed within Turkey.

In October 2019, Turkey's military attacked some SDF-controlled areas in northeastern Syria after President Trump ordered a pullback of U.S. Special Forces following a call with President Erdogan.61 The declared aims of what Turkey called Operation Peace Spring (OPS) were to target "terrorists"—both the YPG and the Islamic State—and create a "safe zone" for the possible return of some of the approximately 3.6 million Syrian refugees in Turkey.62 The ground component of the Turkish operation—as during previous Turkish operations in Syria—was carried out to a major extent by Syrian militia forces comprised largely of Sunni Arab opponents of the Syrian government.

Turkey's capture of territory from the SDF during OPS separated the two most significant Kurdish-majority enclaves in northern Syria, complicating Syrian Kurdish aspirations for autonomy. Turkey then reached agreements with the United States and Russia that ended the fighting, created a buffer zone between Turkey and the YPG, and allowed Turkey to directly monitor some areas over the border (see Figure A-4).63

Ultimate Turkish and YPG objectives regarding the northern Syrian areas in question remain unclear. U.S. officials have continued partnering with SDF forces against the Islamic State in some areas of Syria south of the zones from which YPG personnel were cleared,64 while the SDF has made some arrangements for its own protection by Syrian government forces. Reports of some violence targeting areas under Turkish control suggest the possibility of continued YPG-led action there.65

|

Syrian Refugees in Turkey In addition to its ongoing military activities in Syria, Turkey hosts about 3.6 million registered Syrian refugees—more than any other country. Turkey has largely closed its border to additional refugee influxes since 2016, though it also assists thousands of displaced Syrians in makeshift camps near the border.66 President Erdogan claimed in 2019 that Turkey had spent $40 billion on refugee assistance,67 though one source estimated in November 2019 that the amount could be closer to $24 billion.68 Turkey closed several refugee camps in 2019 and encouraged Syrians in those camps to integrate into Turkish society while resolution of their long-term status is pending. Economic competition—particularly at a time of general economic uncertainty in Turkey—may fuel some tensions between refugees and Turkish citizens.69 While a July 2019 study indicated that 84% of refugee households had at least one member working, most Syrians' jobs are in the informal sector, where wages are below the legal minimum and workers can face exploitation and unsafe working conditions.70 The United Nations estimates that 64% of Syrian refugees in Turkish cities (where the vast majority reside) live below the poverty line. The return of refugees to Syria is a sensitive issue. Some reports claim that, in light of domestic pressure,71 Turkey may have forcibly returned thousands of Syrian refugees to Syria,72 though Turkish officials deny these claims.73 Although Erdogan presented a plan to U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres in November 2019 for facilitating the return of one million refugees to areas of Syria that Turkey captured during OPS, the plan's viability is unclear. |

The Turkish military remains in a standoff with Russia and the Syrian government over the future of Syria's Idlib province, where the main remnants of Sunni Arab opposition to the regime of Bashar al Asad reside. Turkey seeks to protect Idlib's population from the Asad regime, partly because of domestic concerns about additional refugee influxes. However, Russian willingness to back Syrian operations in Idlib perhaps stems in part from Turkey's unwillingness or inability to enforce a 2018 Turkey-Russia agreement by removing heavy weapons and "radical terrorist groups" from the province.74

In early 2020, a Russian-aided Syrian offensive in Idlib led to several Turkish casualties, displaced hundreds of thousands of Syrian civilians, and opened highway access for Syrian forces through the province to other parts of the country (see Figure A-4). During the fighting, Turkish officials apparently sought to pressure the EU into revising a 2016 deal on refugees by facilitating the passage of some over Turkey's border with Greece.75 Any pressure that resulted was relatively light given robust Greek border controls and reportedly little interest in leaving Turkey among Syrian refugees who live there.76 The United States announced in March 2020 that it would provide ammunition for the Turkish military, as well as $108 million in humanitarian assistance for U.N. programs aiding Syrian civilians.77

Domestic Turkish Developments

Political Developments Under Erdogan's Rule

President Erdogan has ruled Turkey since becoming prime minister in 2003. After Erdogan became president in August 2014 via Turkey's first-ever popular presidential election, he claimed a mandate for increasing his power and pursuing a "presidential system" of governance, which he achieved in a 2017 referendum and 2018 presidential and parliamentary elections. Some allegations of voter fraud and manipulation surfaced in both elections.78 Since the July 2016 coup attempt, Erdogan and his Islamist-leaning Justice and Development Party (Turkish acronym AKP) have adopted more nationalistic policy approaches, partly because of their reliance on parliamentary support from the Nationalist Movement Party (Turkish acronym MHP).

Erdogan is generally seen as a polarizing figure, with about half the country supporting his rule, and half the country opposing it. The AKP maintained the largest share of votes in 2019 local elections, but lost some key municipalities, including Istanbul, to opposition candidates. It remains unclear to what extent, if at all, these losses pose a threat to Erdogan's rule. Since the local elections, former Erdogan colleagues and senior officials Ahmet Davutoglu and Ali Babacan each have established new political parties that could weaken Erdogan's political base.

U.S. and EU officials have expressed a number of concerns about authoritarian governance and erosion of rule of law and civil liberties in Turkey.79 In the government's massive response to the 2016 coup attempt, it detained tens of thousands, enacted sweeping changes to the military and civilian agencies, and took over or closed various businesses, schools, and media outlets.80

|

COVID-19 in Turkey and Government Response As of early April 2020, Turkey had the ninth-most reported COVID-19 cases in the world. After the outbreak became apparent in March, Turkey started suspending public gatherings and international travel, and limiting its residents' movements. Additionally, in March, 410 people were reportedly arrested for spreading "unrest" related to COVID-19 via social media.81 Looking ahead, Turkey faces challenges regarding the capacity of its health care system and potential outbreaks among concentrated refugee populations. To address the economic slowdown from COVID-19, President Erdogan announced a $15 billion response package on March 18. If the impact to Turkey's economy—including its tourism sector and exports—significantly delays recovery, further government efforts may be difficult given Turkey's existing economic vulnerabilities and questions about its foreign exchange reserves.82 |

Economic Status

Since 2018, Turkey has confronted economic problems that have fueled speculation about potential crises that could affect Erdogan's status and domestic political stability. The government and an increasingly less independent central bank intervene periodically to stimulate the economy, but concerns persist about rule of law; significant corporate debt and external financing needs;83 and the possibility of U.S. sanctions in relation to the S-400 purchase, Syria, or the Halkbank case.

The global COVID-19 outbreak and accompanying economic slowdown are having a major impact on Turkey's economy. As of early April 2020, the value of Turkey's currency had sharply declined amid the pandemic, but longer-term outcomes are unclear.84

Appendix A. Maps, Facts, and Figures

|

|

Geography |

Area: 783,562 sq km (302,535 sq. miles), slightly larger than Texas |

|

People |

Population: 82,017,514 (2020) Most populous cities: Istanbul 14.8 mil, Ankara 5.3 mil, Izmir 4.2 mil, Bursa 2.9 mil, Antalya 2.3 mil (2016) % of Population 14 or Younger: 23.4% Ethnic Groups: Turks 70%-75%; Kurds 19%; Other minorities 7%-12% (2016) Religion: Muslim 99.8% (mostly Sunni), Others (mainly Christian and Jewish) 0.2% Literacy: 96.2% (male 98.8%, female 93.5%) (2017) |

|

Economy |

GDP Per Capita (at purchasing power parity): $29,693 Real GDP Growth: 0.2% Inflation: 13.5% Unemployment: 13.8% Budget Deficit as % of GDP: 3.4% Public Debt as % of GDP: 30.4% Current Account Surplus as % of GDP: 0.2% International reserves: $106 billion |

Sources: Graphic created by CRS. Map boundaries and information generated by Hannah Fischer using Department of State boundaries (2011); Esri (2014); ArcWorld (2014); DeLorme (2014). Fact information (2019 estimates unless otherwise specified) from International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database; Turkish Statistical Institute; Economist Intelligence Unit; and Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook.

|

Figure A-2. Map of U.S. and NATO Military Presence in Turkey |

|

|

Sources: Department of Defense, NATO, and various media outlets; adapted by CRS. Notes: All locations are approximate. |

|

Figure A-3. Arms Imports as a Share of Turkish Military Spending |

|

|

Sources: Stratfor, based on information from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute Arms Traders Database. |

|

|

Source: CRS, using area of influence data from IHS Jane's Conflict Monitor. All areas of influence approximate and subject to change. Other sources include U.N. OCHA, Esri, and social media reports. Note: This map does not depict all U.S. bases in Syria. |

Appendix B. Timeline of Turkey's Involvement in Syria (2011-2020)

|

2011 |

Though the two leaders once closely corresponded, then-Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan calls for Syrian President Bashar al Asad to step down as protests and violence escalate; Turkey begins support for Sunni Arab-led opposition groups in cooperation with the United States and some Arab Gulf states |

|

2012-2014 |

As conflict escalates in Syria and involves more external actors, Turkey begins facing cross-border fire and jihadist terrorist attacks in border areas and urban centers; as well as allegations of Turkish government permissiveness with jihadist groups that oppose the Asad government |

|

Turkey unsuccessfully calls for U.S. and NATO assistance to establish safe zones in northern Syria as places to train opposition forces and gather refugees and IDPs |

|

|

At Turkey's request, a few NATO countries (including the United States) station air defense batteries in Turkey near Syrian border |

|

|

2014 |

The Islamic State obtains control of large swath of northern Syria |

|

IS attack on Kurdish-majority Syrian border town of Kobane unchallenged by Turkish military but repulsed by YPG-led Syrian Kurds (and some non-YPG Kurds from Iraq permitted to transit Turkish territory) with air support from U.S.-led coalition, marking the beginning of joint anti-IS efforts between the United States and YPG-led forces (including non-Kurdish elements) that (in 2015) become the SDF through U.S. train-and-equip initiatives |

|

|

Turkey, with Erdogan now president, begins allowing anti-IS coalition aircraft to use its territory for reconnaissance purposes |

|

|

2015 |

Turkey begins permitting anti-IS coalition aircraft to conduct airstrikes from its territory |

|

As YPG-led forces find success in taking over IS-controlled areas with U.S.-led coalition support, a Turkey-PKK peace process (ongoing since 2013) breaks down and violence resumes in Turkey; Turkish officials' protests intensify in opposition to U.S. partnership with SDF in Syria |

|

|

U.S. military withdraws Patriot air defense battery from Turkey; some other NATO countries continue operating air defense batteries on Turkey's behalf |

|

|

In September, Russia expands its military involvement in Syria and begins helping Asad regain control over much of the country In November, a Turkish aircraft shoots down a Russian aircraft based in Syria under disputed circumstances; Russia responds with punitive economic measures against Turkey |

|

|

2016 |

After failed coup attempt in Turkey in July, Turkey partners in August with Syrian opposition forces on its first military operation in Syria (Operation Euphrates Shield), an effort to eject IS fighters from and occupy an area between SDF-controlled enclaves |

|

2017 |

Turkey begins Astana peace process on Syria with Russia and Iran |

|

In preparation for the campaign against the final major IS-held urban center in Raqqah, U.S. officials decide in May to arm YPG personnel directly, insisting to protesting Turkish officials that the arms will be taken back after the defeat of the Islamic State |

|

|

2018 |

Turkey and its Syrian opposition partners militarily occupy the Kurdish enclave of Afrin (Operation Olive Branch); significant Kurdish displacements prompt humanitarian and human rights concerns In September, Turkey and Russia agree on parameters for Idlib province, including a demilitarized zone |

|

2019 |

Erdogan insists on a safe zone in Syria to prevent opportunities for YPG attacks in Turkey or collaboration with Turkey-based PKK forces, and to resettle Syrian refugees; U.S. officials try to prevent conflict and to get coalition assistance to patrol border areas in northeastern Syria |

|

In October, President Trump announces highly controversial pullback of U.S. Special Forces from SDF-controlled border areas; to date, the United States had not recovered U.S.-origin arms from YPG personnel Turkey launches Operation Peace Spring (OPS), with Turkish-led forces obtaining control of various border areas and key transport corridors in northeastern Syria; reports of civilian casualties and displacement take place amid general humanitarian and human rights concerns Turkey reaches agreements with United States and Russia that end OPS and create a buffer zone between Turkey and the YPG |

|

|

2020 |

A Russian-aided Syrian offensive in Idlib province leads to several Turkish and Syrian casualties, displaces hundreds of thousands of Sunni Arabs, and opens access for Syrian forces through the province to other parts of the country |

Sources: Various open sources.