Introduction

Concurrent receipt in the military and veterans context typically means simultaneously receiving two types of federal monetary benefits: military retired pay from the Department of Defense (DOD) and disability compensation from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). With several separate programs, varying eligibility criteria, and several eligibility dates, some observers find the subject complex and somewhat confusing. However, concurrent receipt is applicable only to persons who are both (1) military retirees and (2) eligible for VA disability compensation. This report addresses the two primary components of the concurrent receipt program: Combat-Related Special Compensation (CRSC) and Concurrent Retirement and Disability Payments (CRDP). It reviews the possible legislative expansion of the program to additional populations and provides several potential options for Congress to consider.

Background

In 1891, Congress first prohibited payment of both military retired pay and a disability pension under the premise that it represented dual or overlapping compensation for the same purpose. Congress modified that law in 1941, and in 1944 adopted a system of offsetting military retired pay with VA disability compensation. Under this system, retired military personnel were required to waive a portion of their retired pay equal to the amount of VA disability compensation, a dollar-for-dollar offset.1 If, for example, a military retiree received $1,500 a month in retired pay and was rated by the VA as 70% disabled (and therefore entitled to approximately $1,000 per month in disability compensation), the offset would operate to pay $500 monthly in retired pay and $1,000 in disability compensation. Thus, the retiree still received a total of $1,500 per month, but the advantage for the retiree was that the VA disability compensation portion was not taxable. For many years some military retirees and advocacy groups sought a change in law to permit receipt of all, or some, of both payments without offset. Opponents of concurrent receipt frequently referred to it as double dipping, maintaining that it represented two payments for the same condition. Supporters of concurrent receipt argued that the two payments were for different purposes: retired pay was deferred compensation for a career of service, while disability compensation was to account for loss future earning power.

In the FY2003 NDAA, Congress created a benefit known as Combat Related Special Compensation (CRSC).2 For certain disabled retirees whose disability is combat-related, CRSC provides a cash benefit financially identical to what concurrent receipt would provide them. The FY2004 NDAA authorized, for the first time, the phase-in of actual concurrent receipt (now referred to as Concurrent Retirement and Disability Payments or CRDP) for certain retirees, along with a greatly expanded CRSC program.3 The FY2005 NDAA further liberalized the concurrent receipt rules contained in the FY2004 NDAA and authorized immediate concurrent receipt for those with VA disability ratings totaling 100%.4 In 2007, as part of the FY2008 NDAA, Congress expanded concurrent receipt eligibility to include those who are 100% disabled due to unemployability and provided CRSC to those who were medically retired or retired prematurely due to force reduction programs prior to completing 20 years of service.5 The CRDP phase-in was fully implemented by 2014, and currently allows retirees with a VA disability rated at 50% or greater to receive both full retired pay and full VA disability compensation without any offset.

Military Retirement and VA Disability Compensation

An understanding of military retirement, VA disability compensation, and the interaction of these two benefits is helpful when discussing concurrent receipt.

Military Retirement

An active duty servicemember becomes entitled to retired pay, an event frequently referred to as vesting, upon completion of 20 years of service, regardless of age. A member who retires is immediately paid a monthly annuity based on a percentage of their final base pay or the average of their high three years of base pay, depending on when they entered active duty.6 Retired pay accrues at the rate of 2.5% per year of service for those who have entered the service prior to January 1, 2018, and 2.0% for those entering service on or after that date.7

Reserve Retirement

Reserve component servicemembers also become eligible for retirement upon completion of 20 years of qualifying service, regardless of age. However, their retired pay calculation is based on a point system that results in a number of equivalent years of service.8 In addition, a reserve component retiree does not usually begin receiving retired pay until reaching age 60.9 Those reservists who have retired from service but do not yet receive retired pay are sometimes called gray-area retirees.

Disability Retirement

While retired pay eligibility at 20 years of service is the norm for active component members and age 60 for reserve component members, earlier eligibility is possible under some circumstances. Servicemembers found to be unfit for continued service due to physical disability may be retired if the condition is permanent and stable and the disability is rated by DOD as 30% or greater.10 These retirees are generally referred to as Chapter 61 retirees, a reference to Chapter 61 of Title 10, which covers disability retirement. As a result, some disability retirees are retired before becoming eligible for longevity retirement while others have completed 20 or more years of service.

A servicemember retired for disability may select one of two available options for calculating their monthly retired pay:

- 1. Longevity Formula. Retired pay is computed by multiplying the years of service times 2.5% or 2.0% (based on a date of entry into service before or after Jan 1, 2018), then multiplying that result by the pay base.

Monthly Retired Pay= (years of service x 2.5% or 2.0%) x (pay base)

- 2. Disability Formula. Retired pay is computed by multiplying the DOD disability percentage by the pay base.11

Monthly Retired Pay= disability % x (pay base)

The maximum retired pay calculation under the disability formula cannot exceed 75% of base pay.12 Since the disability percentage method usually results in higher retired pay, it is most commonly selected. Generally, military retired pay based on longevity is taxable. Retired pay computed under the disability formula is also fully taxed unless the disability is the result of a combat-related injury.

Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA)

Personnel retired due to force management requirements and before completing 20 years of service are generally referred to as "TERA retirees" because the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1993 granted Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA) as a force-sizing tool to entice voluntary retirements during the drawdown of the early 1990s.13 TERA retired pay is calculated in the same way as longevity retirement, but there is a retired pay reduction of 1% for every year of service below 20.

VA Disability Compensation

To qualify for VA disability compensation, the VA must make a determination that the veteran sustained a particular injury or disease, or had a preexisting condition that was aggravated, while serving in the Armed Forces.14 Some exceptions exist for certain conditions that may not have been apparent during military service but which are presumed to be service-connected. The VA has a scale of 10 ratings, from 10% to 100%, although there is no direct arithmetical relationship between the benefits paid at each step. Each percentage rating entitles the veteran to a specific level of disability compensation.15 In a major difference from the DOD disability retirement system, a veteran receiving VA disability compensation can ask for a medical reexamination at any time (or a veteran who does not receive disability compensation upon separation or retirement from service can be examined or reexamined later). All VA disability compensation is tax-free, which makes receipt of VA compensation desirable, even with the operation of the offset.

Interaction of DOD and VA Disability Benefits

As veterans, military retirees can apply to the VA for disability compensation. A retiree may (1) apply for VA compensation any time after leaving the service and (2) have his or her degree of disability changed by the VA as the result of a later medical reevaluation, as noted above. Many retirees seek benefits from the VA years after retirement for a condition that may have been incurred during military service but that does not manifest itself until many years later. Typical examples include hearing loss, some cardiovascular problems, and conditions related to exposure to Agent Orange.

The DOD and VA disability rating systems have much in common, but there are also significant differences. DOD makes a determination of eligibility for disability retirement only once, at the time the individual separates from the service. Although DOD uses the VA rating schedule to determine the percentage of disability, DOD measures disability, or lack thereof, against the extent to which the individual can or cannot perform military duties. Military disability retired pay, unlike VA disability compensation, is usually taxable unless related to a combat disability.

As a result of the current disability process, a retiree can have both a DOD and a VA disability rating, but these ratings will not necessarily be the same percentage. The percentage determined by DOD is used to determine fitness for duty and may result in the medical separation or disability retirement of the servicemember. The VA rating, on the other hand, was designed to reflect the average loss of earning power. Two major studies published in 2007 recommended a single, comprehensive medical examination that would establish a disability rating that could be used by both DOD and the VA.16

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2008 required a joint DOD and VA report on the feasibility of consolidating disability evaluation systems to eliminate duplication by having one medical examination and a single-source disability rating.17 As a result, DOD and the VA initiated a one-year pilot program, now called the Integrated Disability Evaluation System (IDES), at two military bases. The program was expanded to other sites in 2009 and 2010, and since September 2011 all new disability retirement cases at facilities worldwide have been processed through IDES.18

As IDES was designed to streamline the disability evaluation process, DOD and VA now focus on trying to improve health care data and records sharing, a process deemed "vital to Service members who are leaving the DOD system with complex medical issues and ongoing health care needs."19 In September 2018, DOD and VA issued a joint statement indicating their commitment to implement an integrated electronic health system in an effort to allow for seamless sharing of health care data between both departments and aid the disability rating process.20

Combat-Related Special Compensation (CRSC)

The FY2003 NDAA,21 as amended by the FY2004 NDAA,22 authorized Combat-Related Special Compensation (CRSC). Military retirees with at least 20 years of service and who meet either of the following two criteria are eligible for CRSC:

- A disability that is "attributable to an injury for which the member was awarded the Purple Heart," and is not rated as less than a 10% disability by the VA; or

- A disability rating resulting from involvement in "armed conflict," "hazardous service," "duty simulating war," or "through an instrumentality of war."23

This definition of combat-related encompasses disabilities associated with any kind of hostile force; hazardous duty such as diving, parachuting, or using dangerous materials such as explosives; and individual training and unit training and exercises and maneuvers in the field. Instrumentalities of war include vehicles, vessels, or devices designed primarily for military service, for example combat vehicles, Navy ships, and military aircraft. Injuries associated with instrumentalities of war may also be those associated with, for example, munitions explosions or inhalation of gases or vapors in combat training.

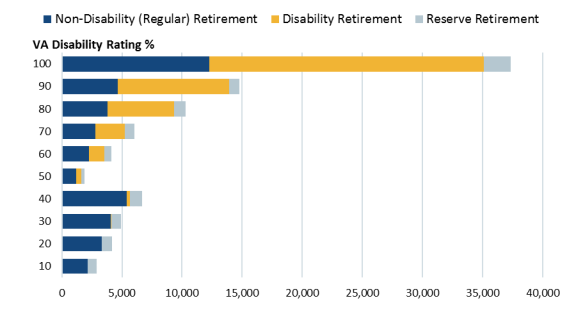

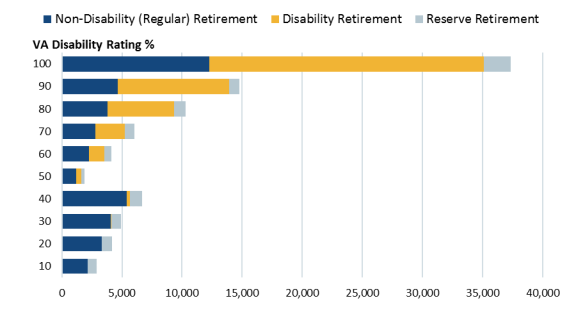

Retirees must apply for CRSC to their parent service, and the parent service is responsible for verifying that the disability is combat-related. This process is not automatic; it is application-driven. CRSC payments will generally be equal to the amount of VA disability compensation that has been determined to be combat-related. The legislation does not end the requirement that the retiree's military retired pay be reduced by the amount of the total VA disability compensation the retiree receives. Instead, CRSC beneficiaries are to receive the financial equivalent of concurrent receipt as "special compensation," but the statute states explicitly that it is not retired pay per se. CRSC payments are paid from the DOD Military Retirement Fund.24 As of September 2018, a total of 93,106 retirees were receiving CRSC (see Figure 2).25

|

Figure 2. Current CRSC Recipients by Disability Rating

Number of recipients as of September 30, 2018

|

|

|

Source: DOD Office of the Actuary, FY2018 Statistical Report on the Military Retirement System: Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 2018, May 2019, p. 196.

Note: Data do not include 50 individuals with an unknown VA disability rating.

|

CRSC for Military Disability (Chapter 61) and TERA Retirees

Servicemembers with a permanent DOD disability rating of 30% or greater may be retired and receive retired pay prior to completing 20 years of service. These retirees are generally referred to as "Chapter 61" retirees, a reference to Chapter 61, Title 10, which governs disability retirement. In addition to the Chapter 61 retirees with less than 20 years of service, those who voluntarily retired under the Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA). The original CRSC legislation excluded those active duty members who retired with less than 20 years of service.

The FY2008 NDAA expanded CRSC to include Chapter 61 and active duty TERA retirees effective January 1, 2008.26 Eligibility no longer requires a minimum number of years of service or a minimum disability rating (other than the 30% noted above for disability retirement); a 10% VA rating may qualify if it is combat-related. Eligible retirees must still apply to their parent service to validate that the disability is combat-related.

The FY2008 NDAA included almost all reserve disability retirees in the eligible CRSC population except those retired under 10 U.S.C. 12731b, a special provision which allows reservists with a physical disability not incurred in the line of duty to retire with between 15 and 19 creditable years of service.

The Special Rule for Disability Retirees

As noted earlier, an individual generally cannot receive two separate lifelong government annuities from federal agencies for the same purpose or qualifying event, for example, disability retired pay and VA disability compensation. To preclude this, there is a special rule for Chapter 61 disability retirees. Application of the special rule caps the CRSC at the level to which the retiree could have qualified based solely on years of service or longevity. In some instances, the special rule could limit or completely eliminate the concurrent receipt payment. In other instances, application of the rule may not result in any changes. Each situation is unique (rank, years of service, DOD and VA disability ratings, and the disability percentage attributable to combat) and requires independent calculations.

Those most likely to see a reduction of CRSC due to the special rule are active duty servicemembers with a disability retirement who have significantly less than 20 years of service and a high VA disability rating. Reserve members with little active duty could also be impacted.

CRSC for Reserve Retirees

When CRSC was originally enacted in 2002, it required all applicants to have at least 20 years of service creditable for computation of retired pay. As a result, reserve retirees had to have at least 7,200 reserve retirement points (which converts to 20 years of equivalent service) to be eligible for CRSC. As noted earlier, a reservist receives a certain number of retirement points for varying levels of participation in the reserves, or active duty military service. The 7,200-point figure could only have been attained by a reservist who had many years of active duty military service in addition to a long reserve career. Initially this law, as enacted, effectively denied CRSC to almost all reservists.

However, a provision in the FY2004 NDAA revised the service requirement for reserve component personnel. It specified that personnel who qualify for reserve retirement by having at least 20 years of duty creditable for reserve retirement are eligible for CRSC. While eligible for CRSC, reserve retirees must be drawing retired pay (generally at age 60) to actually receive the CRSC payment.

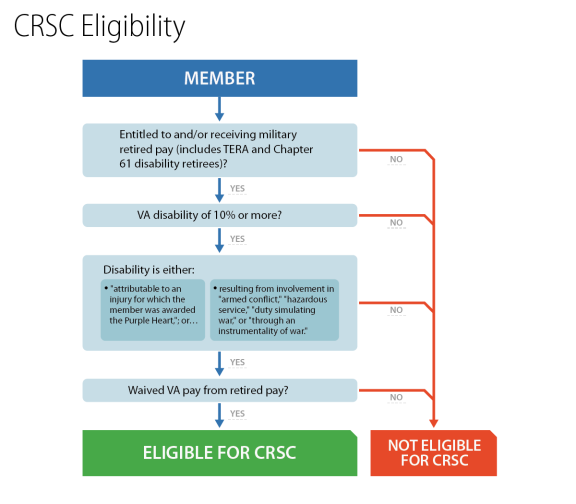

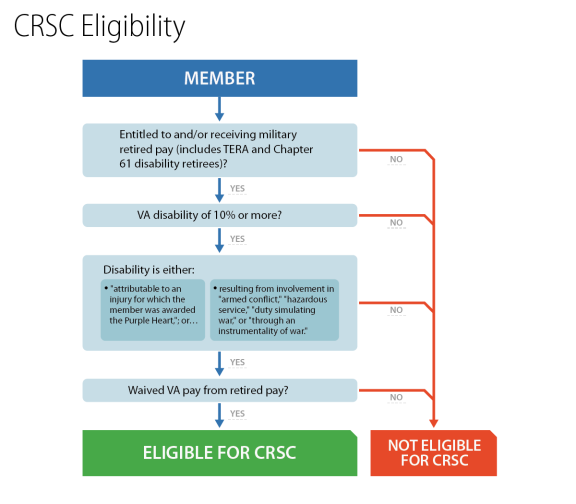

CRSC Eligibility Summary

Essentially all military retirees who have combat-related disabilities compensable by the VA are eligible for CRSC (see Figure 3). Military retirees with service-connected disabilities which are not combat-related as defined by the statute are not eligible for CRSC, but may be eligible for CRDP as discussed below.

|

Figure 3. CRSC Eligibility

|

|

|

Source: CRS, Title 10 of the United States Code.

Notes: Member refers to a retired member of the Armed Forces. Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA) retirees are those retired with less than 20 years of service due to force management requirements. Disability ratings are awarded in 10% increments. VA pay is veteran disability compensation.

|

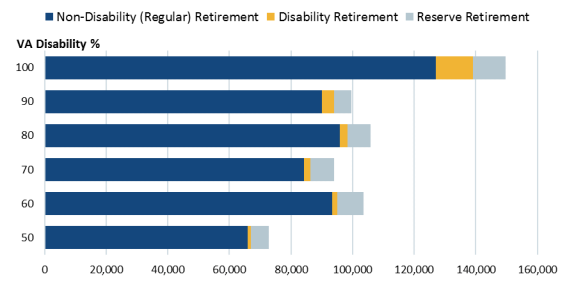

Concurrent Retirement and Disability Payments (CRDP)

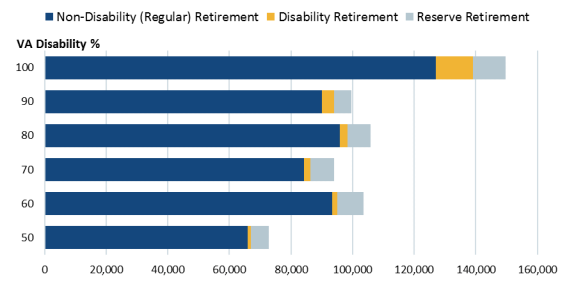

The FY2004 NDAA authorized, for the first time, actual concurrent receipt of retired pay and veteran disability compensation for retirees with at least a 50% disability, regardless of the cause of disability.27 The amount of concurrent receipt was phased in over a 10-year period, from 2004 to 2013, except for 100% disabled retirees, who became entitled to immediate concurrent receipt effective January 1, 2005. Depending on the degree of disability, the initial amount of retired pay that the retiree could have restored would vary from $100 to $750 per month, or the actual amount of the offset, whichever was less. In 2014, all offsets ended; military retirees with at least a 50% disability became eligible to receive their entire military retired pay and VA disability compensation. In FY2018 there were 625,765 retirees receiving CRDP.28

|

Figure 4. Current CRDP Recipients by Disability Rating

Recipients as of September 30, 2018

|

|

|

Source: DOD Office of the Actuary, FY2018 Statistical Report on the Military Retirement System: Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 2018, May 2019, p. 196.

Notes: Disability retirees generally must have over 20 years of service to qualify for CRDP. Data do not include 283 individuals with an unknown VA disability rating.

|

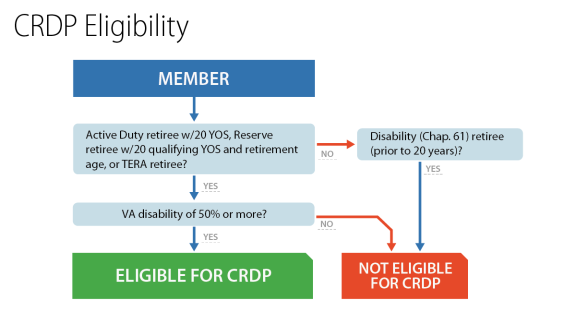

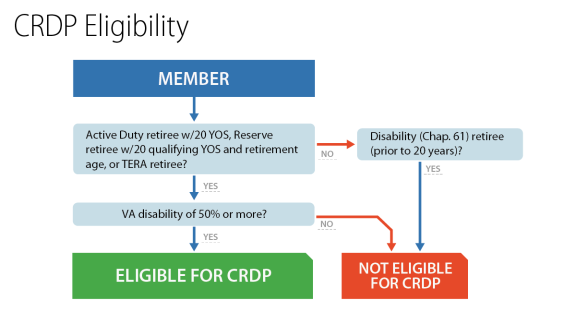

A retiree cannot receive both CRSC and CRDP benefits. The retiree may choose whichever is more financially advantageous to him or her and may change the type of benefit to be received during an annual open season to maximize the payments received. There are currently two groups of retirees who are not eligible for CRDP benefits (see Figure 5). The first group is nondisability military retirees with service-connected disabilities that have been rated by the VA at 40% or less. The second group includes Chapter 61 disability retirees with service-connected disabilities and less than 20 years of service.

|

Figure 5. CRDP Eligibility

|

|

|

Source: CRS, Title 10 of the United States Code.

Notes: "Member" refers to a retired member of the Armed Forces. Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA) retirees are those retired with less than 20 years of service due to force management requirements. Disability ratings are awarded in 10% increments.

|

CRDP for Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA) Retirees

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1993 granted temporary authority for the services to offer early retirements to personnel with more than 15 but less than 20 years of service.29 This authority was extended in subsequent authorization bills. TERA was used as a force-sizing tool to entice voluntary retirements during the post-Cold War drawdown. TERA retired pay was calculated in the usual way except that there is an additional reduction of 1% for every year of service below 20. Part or all of this latter reduction could be restored if the retiree worked in specified public service jobs (such as law enforcement, firefighting, and education) during the period immediately following retirement, until the point at which the retiree would have reached the 20-year mark if he or she had remained in the service.

TERA retirees are eligible for CRSC and CRDP even though they have less than 20 years of service. The special rule for disability retirees (see "The Special Rule for Disability Retirees") does not apply to TERA retirees since TERA is not a disability retirement, but rather a regular retirement but for those with less than 20 years of service.

Concurrent Receipt and Blended Retirement System Lump Sum Payments

The Blended Retirement System (BRS), effective for all servicemembers joining on or after January 1, 2018, offers servicemembers the option to select a lump sum payment of a portion of their military retired pay in lieu of a monthly annuity.30 If a member retiring under the BRS is eligible for CRDP and elects the lump sum payment of retired pay, the individual is to continue to receive a monthly VA disability payment. If the member electing the lump sum payment is not eligible for CRDP (i.e., the retired pay offset applies), the VA is to withhold disability payments until the sum of the amount withheld over time equals the gross amount of the lump sum payment.31 If the member is eligible for CRSC, the procedures for withholding VA disability payments relate to the combat-related portion of the total VA entitlement.32

CRSC and CRDP Comparisons and Costs

CRSC and CRDP share some common elements, but are unique benefits. Table 1 summarizes some of the similarities and differences between CRSC and CRDP.

Table 1. Comparison of CRSC and CRDP

|

|

CRSC

|

CRDP

|

|

Classification

|

Special compensation

|

Military retired pay

|

|

Qualified disabilities

|

Combat-related disabilities

|

Service-connected disabilities

|

|

Enrollment

|

Must apply to parent service for verification that disability is combat-related

|

Automatic, initiated by DFAS

|

|

Type of Compensation

|

Special compensation (not retired pay)

|

Restored retired pay

|

|

Tax Liability

|

Nontaxable

|

Taxable

|

|

Subject to Division with a Former Spouse

|

No

|

Yes (longevity retired pay portion only)a

|

|

Subject to Garnishment for Alimony and/or Child Support

|

Yes

|

Yes (longevity retired pay portion only)

|

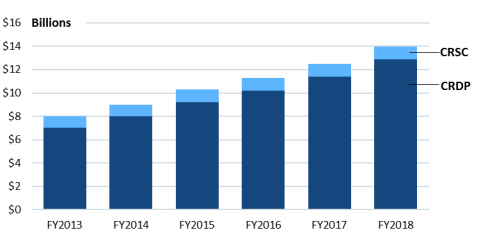

CRDP and CRSC are paid from the DOD Military Retirement Fund.33 Costs have been rising every year as a consequence of the phased implementation and a rise in the number of eligible recipients.34 As of September 2018, 36% of all military retirees collecting retired pay were receiving either CRDP or CRSC.35

Table 2. Number of Concurrent Pay Recipients and Estimated Annual Payments

FY2009-FY2018

|

Fiscal Year

|

CRDP

|

CRSC

|

|

|

|

Number of Recipients

|

Annual Payments (billions)

|

Number of Recipients

|

Annual Payments (billions)

|

% of Total Retirees Receiving CRDP or CRSC

|

|

FY2018

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FY2017

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FY2016

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FY2015

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FY2014

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FY2013

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FY2012

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FY2011

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FY2010

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FY2009

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: DOD Office of the Actuary Statistical Reports on the Military Retirement System.

Notes: Some retirees may be eligible for both CRSC and CRDP but can only receive one or the other. Annual payments are made from the DOD Military Retirement Fund. The phase-in period for full CRDP was complete on December 31, 2013.

Other Compensation for Injuries or Deaths Related to Military Service

Another way that deceased or disabled servicemembers or their families could potentially obtain government compensation would be by suing the government in court. However, the United States has sovereign immunity, which prevents private citizens from suing it in court unless the government consents to the suit.36

Claims Brought by Veterans

Congress has waived the United States' sovereign immunity in certain circumstances, including for some tort claims for injuries or deaths caused by negligent or wrongful acts of federal employees.37 Subject to various exceptions and conditions, the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) of 1946 generally authorizes plaintiffs to bring civil lawsuits:

- against the United States;

- for money damages;

- for injury to or loss of property, or personal injury or death;

- caused by a federal employee's negligent or wrongful act or omission;

- while acting within the scope of his or her office or employment;

- under circumstances where the United States, if a private person, would be liable to the plaintiff in accordance with the law of the place where the act or omission occurred.38

The FTCA thus authorizes veterans39 in certain circumstances to sue the United States for the negligent or wrongful acts of federal employees. Most relevant to the disability context, such lawsuits can include suits involving VA medical personnel acting within the scope of their employment.40

While a court may award a plaintiff money damages in an FTCA suit for medical malpractice or other injuries caused by the VA, Congress specifically provided that such FTCA judgments would postpone VA disability benefits until the amount of forestalled benefits equals the amount of the judgment.41 In other words, a veteran who wins or settles a medical malpractice lawsuit is to have benefits withheld in the same amount of the award.42 For example, if a veteran suffered an injury at a VA hospital that resulted in a disability that entitled her to $1,000 per month, but he or she sued the VA under the FTCA and was awarded $50,000 in damages, his or her disability benefits would be withheld for four years and two months (i.e., 50 months) following that award. For very large awards, the veteran might not receive any further monthly benefits because the cumulative withheld benefits would never exceed the full amount of the award.

Claims Brought by Active Servicemembers

Congress specifically excluded claims arising out of wartime military combatant activities from the FTCA,43 meaning that wartime active-duty servicemembers who were injured or died as a result of combatant activities could not sue the federal government for compensation.

In 1950, the Supreme Court determined that the United States was more broadly immune from suit for injuries to active-duty servicemembers whenever the injuries arise out of, or occur during, activities related to military service.44 Unlike the explicit statutory bar on lawsuits arising out of combatant activities, the bar on lawsuits arising out of military service activities is a judicially created exception to the FTCA without any explicit textual basis.45 This exception came to be known as the Feres doctrine, named for the Supreme Court case dismissing claims brought by or on behalf of several servicemembers who sustained injuries due to alleged negligence of others in the armed forces.46 The Supreme Court has routinely declined invitations to revisit or alter the Feres doctrine in subsequent years.47

The FY2020 NDAA, however, newly authorizes the Secretary of Defense to allow, settle, and pay an administrative claim against the United States for personal injury or death of a servicemember caused by a DOD health care provider's medical malpractice.48 Similar provisions had been introduced in both houses as the SFC Richard Stayskal Military Medical Accountability Act,49 named for a Purple Heart recipient whose misdiagnosis while he was on active duty allegedly allowed a cancer to spread until it became terminal.50 The standalone bills would have allowed lawsuits in federal court rather than directing claims to a DOD administrative proceeding.51

The provision in the FY2020 NDAA thus circumscribed the Feres doctrine for cases alleging medical malpractice by DOD health care providers. Although it does not allow lawsuits in federal court (and thus does not technically alter the Feres doctrine), it does provide an avenue by which some servicemembers may settle a claim for compensation for an injury or disability—conceivably, for the same injury or disability that might entitle them to disability retired pay or VA disability compensation.

It is unclear whether payments under this administrative process will require the Secretary to withhold retired pay or disability benefits in the amount of any settlement or award. Generally, administrative adjustment of claims under 28 U.S.C. § 267252 are subject to the same withholding of veterans benefits in the amount of the award as court judgments.53 However, § 2733a may only be used to settle claims "not allowed to be settled and paid under any other provision of law," so it seems to exclude claims that could be settled under the FTCA's administrative process.54

Other Options for Congress

Veteran advocacy groups continue to lobby for changes to the concurrent receipt programs that would expand benefits to a larger population of retirees. Other groups have pressed Congress to offset or streamline duplicative benefits, contending that the dual receipt of VA and DOD payments amounts to double-dipping, or in some cases triple-dipping for those veterans also eligible for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) from the Social Security Administration.55

Some of the factors that Congress might consider regarding potential changes include program costs, program efficiencies, individual eligibility requirements, and interaction with other servicemembers' and veterans' benefits and programs. Below are some options to change concurrent receipt programs that have been proposed or considered.

Eliminate or Sunset Concurrent Receipt Programs

The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that eliminating the CRDP would save the government $139 billion between 2018 and 2026.56 While achieving significant cost savings, eliminating or sunsetting CRDP, CRSC, or both could be unpopular among servicemembers, veterans, and their families. Some previous efforts to reduce benefits to servicemembers have included a grandfather clause that would allow all current servicemembers and retirees to maintain existing benefits while the law would only apply to those who would have joined the service after a specific date.

Allow Concurrent Receipt for Combat-related Disabilities Only

One option could be to eliminate concurrent receipt for noncombat-related disabilities. This option would essentially repeal CRDP and expand CRSC to allow for any retired member to receive concurrent DOD and VA payments, but only for the amount of the disability determined to be combat-related under existing law or other defined criteria. A member could continue to receive VA disability payments and retired pay, but the offset would be applied to the portion of VA disability compensation not related to combat. This would have the effect of reducing or eliminating the concurrent benefit for some military retirees with rated disabilities of 50% or greater that are not related to combat.

Extend CRDP to All Chapter 61 Disability Retirees

As previously discussed, the FY2008 NDAA extended CRSC eligibility to Chapter 61 retirees who retired due to combat-related physical disability prior to completing 20 years of service. However, Chapter 61 retirees with service-connected disabilities rated less than 50% or with less than 20 years of service are not eligible for CRDP. Congress could expand the CRDP provision to include this cohort. Some observers may note that eliminating or modifying the special rule would result in paying for the same disability twice, by DOD and by VA.

Modify or Eliminate the Special Rule

With the extension of CRSC to Chapter 61 disability retirees, the special rule factors significantly into the concurrent receipt calculations. For those whose CRSC payment is limited or eliminated by the special rule, there may be a perceived inequity between CRSC recipients with 20 or more years of service (longevity retirees) and Chapter 61 (disability retirees who generally have less than 20 years of service) retirees.

To resolve this potential issue, Congress could modify or eliminate the special rule or limit its application to specific military operations. Again, eliminating or modifying the special rule would result in a situation that could be perceived as paying for the same disability twice, by DOD and by VA.

Split Compensation by Agency for Longevity and Disability

Another option would be to completely overhaul the military retirement and disability system whereby DOD would only compensate for years of service and the VA would only compensate for disability, as recommended by the Dole-Shalala commission in 2007.57 This commission recommended that in all cases DOD annuity payments should be "based solely on rank and length of service," while the VA should "assume all responsibility for establishing disability ratings and for all disability compensation and benefits programs." Under this scenario, Chapter 61 retirees would not have eligibility to have DOD retired pay calculated under the disability formula. This could make the calculation of retired pay and disability compensation for these retirees less complex.

Extend CRDP to Those with a 40% or Less VA Disability Rating

At present, those military retirees with service-connected disabilities rated at 50% or greater are eligible for CRDP. Congress could revise the concurrent receipt legislation to include the entire population of military retirees with service-connected disabilities. In 2014, CBO estimated that to extend benefits to all veterans who would be eligible for both disability benefits and military retired pay would cost $30 billion from 2015 to 2024.58