Overview

On February 29, 2020, after more than a year of talks between U.S. and Taliban negotiators, the two sides concluded an agreement laying the groundwork for the withdrawal of U.S. armed forces from Afghanistan, and for talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban.

As a prelude, U.S. and Taliban negotiators agreed to a seven-day nationwide "reduction in violence," including attacks against Afghan forces. U.S. military commanders assessed that the truce, which began February 22, largely held, leading to the formal U.S.-Taliban agreement on February 29. As part of the agreement, the United States is to draw down its forces from 13,000 to 8,600 within 135 days (with proportionate decreases in allied force levels) and withdraw all of its forces within 14 months. That withdrawal is under way as of March 2020. Other U.S. commitments include working to facilitate a prisoner exchange between the Taliban and the Afghan government and removing U.S. sanctions on Taliban members by August 27, 2020.

In exchange, the Taliban have committed to not allow its members or other groups, including Al Qaeda, to use Afghan soil to threaten the United States or its allies, including by preventing recruiting, training, and fundraising for such activities. The agreement also says the Taliban "will start intra-Afghan negotiations" on March 10, 2020. It remains unclear to what extent the U.S. withdrawal is contingent upon, or otherwise related to, the Taliban holding talks with Kabul or the outcome of such talks. As of March 11, 2020, the State Department says "preparations for intra-Afghan negotiations are underway," though obstacles, namely continued Taliban attacks and a dispute over a potential prisoner exchange, remain.

Further complicating the situation is the February 18, 2020, announcement of President Ghani's victory in the September 2019 presidential election; his opponents reject the narrow result and have sought to establish themselves as a separate government. This has led to fears of a repeat of the circumstances surrounding the 2014 presidential election, which prompted a dispute between the same two candidates that nearly led to violence and required intensive U.S. diplomacy to broker a fragile power-sharing agreement.

The U.S.-Taliban agreement comes after another violent year in Afghanistan: the United Nations reports that over 10,000 civilians were killed or injured in fighting in 2019, down slightly from 2018. U.S. operations also intensified in 2019, by some measures: the United States dropped more munitions in Afghanistan in 2019 than any other year since at least 2010 and U.S. forces conducted strikes in 31 of Afghanistan's 34 provinces between July and October 2019.1 By some measures, insurgents are in control of or contesting more territory today than at any point since 2001. The conflict also involves an array of other armed groups, including active affiliates of both Al Qaeda (AQ) and the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIS, ISIL, or Da'esh).

The United States has appropriated approximately $137 billion in various forms of reconstruction aid to Afghanistan over the past 18 years, from building up and sustaining the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) to economic development. This assistance has increased Afghan government capacity, but prospects for stability in Afghanistan appear distant. Afghanistan's largely underdeveloped natural resources and/or geographic position at the crossroads of future global trade routes could improve the economic life of the country, and, by extension, its social and political dynamics. Nevertheless, Afghanistan's economic and political outlook remains uncertain, if not negative, in light of ongoing hostilities.

U.S.-Taliban Agreement

On February 29, 2020, after more than a year of official negotiations between U.S. and Taliban representatives, the two sides concluded an agreement laying the groundwork for the withdrawal of U.S. armed forces from Afghanistan, and for talks between Kabul and the Taliban. Subsequent developments, including increased violence and continued gridlock on potential Taliban-Afghan government talks, have raised questions about the agreement and broader U.S. policy in Afghanistan going forward.

Background: U.S.-Taliban Negotiations

In President Donald Trump's August 2017 speech laying out a revised strategy for Afghanistan, he referred to a "political settlement" as an outcome of an "effective military effort," but did not elaborate on what U.S. goals or conditions might be as part of this putative political process. Less than one year later, the Trump Administration decided to enter into direct negotiations with the Taliban, without the participation of Afghan government representatives. With little to no progress on the battlefield, the Trump Administration reversed the long-standing U.S. position supporting an "Afghan-led, Afghan-owned reconciliation process," and the first high-level, direct U.S.-Taliban talks occurred in Doha, Qatar, in July 2018.2 The September 2018 appointment by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo of Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad, the Afghan-born former U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan under President George W. Bush, as Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation added momentum to this effort.

For almost a year, Khalilzad held a near-continuous series of meetings with Taliban representatives in Doha, Qatar, along with consultations with the Afghan, Pakistani, and other regional governments. In late January 2019, Khalilzad stated that, "The Taliban have committed, to our satisfaction, to do what is necessary that would prevent Afghanistan from ever becoming a platform for international terrorist groups or individuals," in return for which U.S. forces would eventually fully withdraw from the country.3 After a longer series of talks that ended in March 2019, Khalilzad announced that an agreement "in draft" had been reached on counterterrorism assurances and U.S. troop withdrawal. He noted that after the agreement was finalized, "the Taliban and other Afghans, including the government, will begin intra-Afghan negotiations on a political settlement and comprehensive ceasefire."4

By August 2019, the process appeared to be reaching its conclusion, with multiple reports detailing the outlines of an emerging U.S.-Taliban arrangement.5 However, on September 7, 2019, President Trump announced that he had "immediately…called off peace negotiations" because of a Taliban attack in Kabul that killed several people, including a U.S. soldier.6 In interviews the following day, Secretary Pompeo said that "we were close," but "the Taliban failed to live up to a series of commitments they had made," leading President Trump to walk away from the deal.7 Taliban officials responded to President Trump by warning that the United States would "regret" abandoning talks while maintaining that "our doors are open for negotiations."8

Within a month, news reports indicated that unofficial talks between Khalilzad and Taliban representatives in Pakistan had begun.9 Momentum was strengthened by Afghan President Ashraf Ghani's November 12 announcement of the planned release of three high-profile Taliban prisoners from Afghan government custody in exchange for an American and an Australian held by the Haqqani Network (a U.S.-designated terrorist organization and semi-autonomous component of the Taliban).10 Ghani stated that the release was aimed at "facilitating face-to-face talks with the Taliban."11 On December 4, the State Department announced Khalilzad would "rejoin talks with the Taliban to discuss steps that could lead to intra-Afghan negotiations and a peaceful settlement of the war, specifically a reduction in violence that leads to a ceasefire."12

Prelude: Reduction in Violence (RiV)

On February 14, 2020, a senior U.S. official revealed that U.S. and Taliban negotiators in Doha had reached a "very specific" agreement to reduce violence across the country, including attacks against Afghan forces, after which, if U.S. military commanders assessed that the truce held, the United States and Taliban would sign a formal agreement. U.S. officials called the reduction in violence (sometimes referred to as "RiV") a test of the Taliban's intentions and of the group's control over its forces, given the possibility for spoilers to upend the negotiation process. In advance of the agreement, Khalilzad reportedly "briefed [U.S.] senators that if violence doesn't abate, the troop withdrawals will stop."13

The reduction in violence went into effect on February 22, 2020. U.S. commander General Scott Miller said that he was "satisfied that the Taliban made a good-faith effort," describing episodes of violence as "sporadic."14 On February 26, Miller made a rare public appearance in Kabul, walking through crowded streets without body armor and mingling with Afghans to demonstrate the reduced threat of violence. According to U.S. and Afghan officials, attacks were down significantly across the country, by as much as 80 percent.15

U.S.-Taliban Agreement

After the weeklong reduction in violence held, Special Representative Khalilzad signed the formal U.S.-Taliban agreement with Taliban deputy political leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar on February 29, 2020, in front of a number of international observers, including Secretary of State Pompeo, in Doha. On the same day in Kabul, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper met with President Ghani to issue a joint U.S.-Afghan declaration reaffirming U.S. support for the Afghan government and reiterating the Afghan government's longstanding willingness to negotiate with the Taliban without preconditions.

As part of the U.S.-Taliban agreement, which is about three and a half pages, the United States is to draw down its forces from 13,000 to 8,600 within 135 days (with proportionate decreases in allied force levels) and withdraw all of its forces within 14 months. Other U.S. commitments include working to facilitate a prisoner exchange between the Taliban and the Afghan government (more below) and removing U.S. sanctions on Taliban members by August 27, 2020. The sanctions removal is contingent upon the start of intra-Afghan negotiations. In exchange, the Taliban has committed to not allow members or other groups, including Al Qaeda, to use Afghan soil to threaten the U.S. or its allies, including by preventing recruiting, training, and fundraising for such activities. The agreement does not appear to formally commit the Taliban to "work alongside of us to destroy" Al Qaeda, as Secretary Pompeo asserted in a March 1, 2020, interview.

The peace agreement also states that the Taliban "will start intra-Afghan negotiations" on March 10, 2020. It remains unclear to what extent the U.S. withdrawal is contingent upon, or otherwise related to, the Taliban holding talks with Kabul or the outcome of such talks. In a February 27 briefing ahead of the agreement signing, one unnamed senior U.S. official said, "if the political settlement fails, if the talks fail, there is nothing that obliges the United States to withdraw troops," while another said, "the withdrawal timeline is related to counterterrorism, not political outcomes."16 The deputy U.S. negotiator Molly Phee said on February 18, "We will not prejudge the outcome of intra-Afghan negotiations, but we are prepared to support whatever consensus the Afghans are able to reach about their future political and governing arrangements."17

According to Time, President Ghani told Members of Congress that the agreement contains "secret annexes" regarding the continued presence of U.S. counterterrorism forces, the Taliban disavowal of Al Qaeda, monitoring mechanisms, and CIA operations in Taliban-controlled areas. U.S. officials have said that "there are parts of this agreement that aren't going to be public, but those parts don't contain any additional commitments by the United States whatsoever," describing the annexes as "confidential procedures for implementation and verification."18 Secretary Pompeo has said "every member of Congress will get a chance to see them," though some Members have raised questions about the necessity of classifying these annexes.19

Potential Obstacles to Intra-Afghan Talks: Prisoner Exchange, Renewed Violence, and Political Disputes

A planned prisoner exchange has emerged as perhaps the most prominent obstacle to the intra-Afghan talks that are necessary to resolve the war in Afghanistan. Some experts point out that "the United States [used] different language in separate documents it agreed with the Taliban and the Afghan government."20 Specifically, the U.S.-Taliban agreement reads that "up to" 5,000 Taliban prisoners and 1,000 Afghan forces held by the Taliban "will be released by March 10, 2020," while the U.S.-Afghan government joint declaration states that the Afghan government "will participate in a U.S.-facilitated discussion" with the Taliban on "the feasibility of releasing significant numbers of prisoners on both sides." President Ghani signed a decree on March 11, 2020, that would release 1,500 prisoners within 15 days as long as they provide written assurances to remain off the battlefield, with further releases of 500 prisoners every two weeks as long as the Taliban engage in talks and reduce violence.21 A Taliban spokesman rejected any conditions-based prisoner release as "against the peace accord that we signed" and insisted that 5,000 prisoners be released before any intra-Afghan talks.22

Another potential barrier to intra-Afghan talks is the resumption of nationwide violence since the U.S.-Taliban agreement. According to Afghan officials, the Taliban carried out at least 76 attacks across 24 of Afghanistan's 34 provinces in the four days after the agreement was signed, a number of attacks similar to the weeks before the reduction in violence.23 A U.S. military spokesman said that the Taliban conducted 43 attacks against Afghan forces in Helmand province on March 3 alone, in response to which the United States conducted its first airstrike in Afghanistan in 11 days.24 A Taliban leader reportedly said that U.S. airstrikes do not violate the agreement as long as they are retaliation against Taliban attacks against Afghan forces and not offensive attacks against Taliban forces.25 However, the Afghan government reported 11 Taliban attacks on March 4 and three Taliban attacks on March 5, making any interpretation of longer term trends difficult. The Taliban denied responsibility for a large-scale attack that killed at least 32 at a memorial for a prominent Shia leader in Kabul on March 6; an attack on the same event last year was claimed by the Islamic State.26

Military officials have given differing interpretations of Taliban attacks. Secretary of Defense Esper said in a March 2 media availability that "our expectation is that the reduction in violence will continue, it [will] taper off until we get intra-Afghan negotiations."27 It is not clear what the basis for that "expectation" is; there is no provision in the U.S.-Taliban agreement committing the Taliban to continue to refrain from attacking Afghan forces. In March 4 testimony, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley described Taliban violence since the agreement signing as "small, lower level attacks" that were "all beaten back."28 CENTCOM Commander General Frank McKenzie said on March 10 that "Taliban attacks are higher than we believe are consistent with an idea to actually carry out" the U.S.-Taliban agreement.29

Further potentially complicating the situation is the February 18, 2020, announcement of President Ghani's victory in the September 2019 presidential election over former Chief Executive Officer Abdullah Abdullah. Abdullah and his supporters reject the narrow result as fraudulent and have sought to establish themselves as a separate government.30 This has led to fears of a repeat of the circumstances surrounding the 2014 presidential election, which prompted a dispute between the same two candidates that nearly led to violence and required intensive U.S. diplomacy to broker a fragile power-sharing agreement. Despite Special Representative Khalilzad's attempts to mediate, Ghani and Abdullah held separate inauguration ceremonies on March 9, 2020. The presence of Khalilzad, along with other senior U.S. and foreign officials, at Ghani's ceremony indicates at least a measure of international recognition for Ghani. It is unclear what kind of governing arrangement could satisfy Abdullah and his supporters, who argue that Ghani did not uphold the previous power-sharing agreement. Ghani abolished the office of the Chief Executive in a March 11, 2020, decree, arguing that his inauguration as president made the position obsolete. The two sides have also disagreed over the size and composition of the prospective negotiating team to meet with the Taliban.

It remains unclear what kind of political arrangement could satisfy both Kabul and the Taliban to the extent that the latter abandons its armed struggle. Afghan President Ghani has promised that his government will not accept any settlement that limits Afghans' rights and has warned that any agreement to withdraw U.S. forces that did not include Kabul's participation could lead to "catastrophe," pointing to the 1990s-era civil strife following the fall of the Soviet-backed government that led to the rise of the Taliban.31 Afghans opposed to the Taliban doubt the group's trustworthiness, and express concern that, in the absence of U.S. military pressure, the group will have little incentive to comply with the terms of an agreement, the most crucial aspect of which would arguably be concluding a comprehensive political settlement with the Afghan government.32 The Taliban have given contradictory signs, and generally do not describe in detail their vision for post-settlement Afghan governance beyond referring to it as a subject for intra-Afghan negotiations.33 While many Afghans, especially women, who remember Taliban rule and oppose the group's policies and beliefs remain wary,34 a December 2019 survey reported that a "significant majority" of Afghans are both aware of (77%) and strongly or somewhat support (89%) efforts to negotiate a peace agreement with the Taliban.35

Military and Security Situation

As of March 2020, there are approximately 12,000 U.S. forces in Afghanistan. 8,000 of these are part of the NATO-led mission in Afghanistan of 16,600 troops, known as Resolute Support Mission (RSM). RSM has trained, advised, and assisted Afghan government forces since its inception in early 2015, when Afghan forces assumed responsibility for security nationwide. Combat operations by U.S. forces also continue and have increased in number since 2017. These two "complementary missions" comprise Operation Freedom's Sentinel.36

As mentioned above, the United States has committed to withdrawing all U.S. forces within 14 months, a long-stated goal of President Trump, who has publicly declared his frustration with how long U.S. forces have been in Afghanistan and his intention to withdraw them from the country. President Trump's desire to withdraw U.S. forces reportedly stems at least in part from frustration with the state of the conflict, which U.S. military officials have assessed as a "strategic stalemate" since at least early 2017.37

Arguably complicating that assessment, the U.S. government has withheld many once-public metrics of military progress. Notably, the U.S. military is "no longer producing its district-level stability assessments of Afghan government and insurgent control and influence."38 This information, which was in every previous Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) quarterly report going back to January 2016, estimated the extent of Taliban control and influence in terms of both territory and population; SIGAR reports it was told by the U.S. military that the assessment is no longer being produced because it "was of limited decision-making value to the [U.S.] Commander."39 The last reported metrics from SIGAR in its January 30, 2019, report, illustrated that the share of districts under government control or influence fell to 53.8%, as of October 2018. This figure, which marked a slight decline from previous reports, was the lowest recorded by SIGAR since tracking began in November 2015; 12% of districts were under insurgent control or influence, with the remaining 34% contested.

|

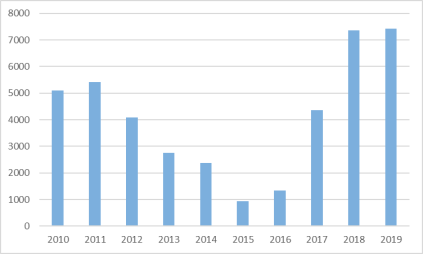

Figure 1. Number of Weapons Released (Manned and Remotely Piloted Aircraft strike assets) by year |

|

|

Source: Combined Forces Air Component Commander 2013-2019 Airpower Statistics. |

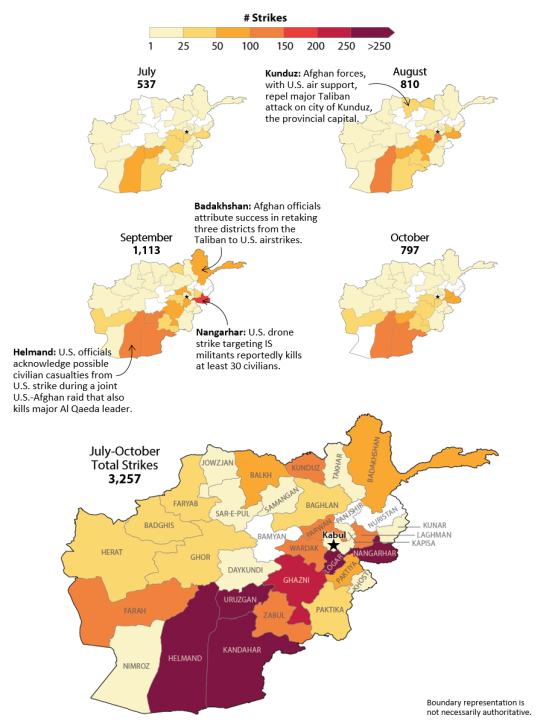

At the same time, U.S. air operations have escalated considerably under the Trump Administration, as measured by the number of munitions released; the U.S. dropped more munitions in Afghanistan in 2019 than any other year since at least 2010 (see Figure 1). These operations have reportedly contributed to a sharp rise in civilian casualties; the U.N. reported that the third quarter of 2019 saw the highest quarterly civilian casualty toll since tracking began in 2009, with over 4,300 civilians killed or injured from July 1 to September 30.40 Though the majority of civilian casualties are attributed to anti-government forces, the U.N. reported in October that civilian casualties from air operations (885 killed or injured) set a record in the first nine months of 2019, with 74% of those casualties resulting from operations by international forces. Between July and October 2019, U.S. forces conducted 3,257 strikes in 31 of Afghanistan's 34 provinces (see Appendix).41

U.S. Adversaries: The Taliban and Islamic State

The leader of the Taliban is Haibatullah Akhundzada, who is known as emir al-mu'minin, or commander of the faithful; the Taliban style themselves as the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. Haibatullah succeeded Mullah Mansoor, who was killed in a 2016 U.S. airstrike in Pakistan; Mansoor had succeeded Taliban founder Mullah Omar, who died of natural causes in April 2013. Formerly a figure in Taliban religious courts, Haibatullah is generally regarded as "more of an Islamic scholar than a military tactician."42 Still, under his leadership the Taliban have achieved some notable military successes and the group is seen as more cohesive and less susceptible to fragmentation than in the past.43 There are an estimated 60,000 full-time Taliban fighters.

The Taliban retain the ability to conduct high-profile urban attacks while also demonstrating considerable tactical capabilities; SIGAR reported in January 2020 that the number of enemy attacks in the fourth quarter of 2019 "exceeded same-period levels in every year since recording began in 2010."44 Reports indicate that ANDSF fatalities have averaged 30-40 a day in recent months, and President Ghani stated in January 2019 that over 45,000 security personnel had paid "the ultimate sacrifice" since he took office in September 2014.45 Insider attacks on U.S. and coalition forces by Afghan nationals are a sporadic, but persistent, problem.

Beyond the Taliban, a significant share of U.S. operations have been aimed at the local Islamic State affiliate, known as Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP, also known as ISIS-K). Estimates of ISKP strength generally ranged from 2,000 to 4,000 fighters until ISKP "collapsed" in late 2019 due to offensives by U.S. and Afghan forces and, separately, the Taliban.46 Special Representative Khalilzad recognized the Taliban's role in progress against ISKP, while warning that ISKP "hasn't been eliminated."47 ISKP and Taliban forces have sometimes fought over control of territory or because of political or other differences.48 Some U.S. officials have stated that ISKP aspires to conduct attacks in the West, though there is reportedly disagreement within the U.S. government about the nature of the threat.49 ISKP also has claimed responsibility for a number of large-scale attacks, many targeting Afghanistan's Shia minority. Some raise the prospect of Taliban hardliners defecting to ISKP in the event that Taliban leaders agree to a political settlement or to a continued U.S. counterterrorism presence.50 The United Nations reported in January 2020 that Al Qaeda leaders were "concerned" by U.S.-Taliban talks, but that relations between Al Qaeda and the Taliban "continue to be close and mutually beneficial, with [Al Qaeda] supplying resources and training in exchange for protection."51

ANDSF Development and Deployment

The effectiveness of the ANDSF is key to the security of Afghanistan. Congress appropriated at least $86.4 billion for Afghan security assistance between FY2002 and FY2019, according to SIGAR.52 Since 2014, the United States generally has provided around 75% of the estimated $5 billion to $6 billion a year required to fund the ANDSF, with the balance coming from U.S. partners ($1 billion annually) and the Afghan government ($500 million).

Concerns about the ANDSF raised by SIGAR, the Department of Defense, and others include absenteeism, the fact that about 35% of the force does not reenlist each year, and the potential for rapid recruitment to dilute the force's quality; widespread illiteracy within the force; credible allegations of child sexual abuse and other potential human rights abuses;53 and casualty rates often described as unsustainable.

Total ANDSF strength was reported at about 273,000 as of October 2019, up 19,000 from the previous quarter. The U.S. military attributed the increase to changes in enrollment verification processes and added that "quarter-to-quarter changes in ANDSF assigned strength do not solely reflect changes to the number of personnel actually serving in the ANDSF."54 Other metrics related to ANDSF performance, including casualty and attrition rates, have been classified by U.S. Forces-Afghanistan (USFOR-A) starting with the October 2017 SIGAR quarterly report, citing a request from the Afghan government, although SIGAR had previously published those metrics as part of its quarterly reports.55 In both legislation and public statements, some Members of Congress have expressed concern over the decline in the types and amount of information made public by the executive branch.

Regional Dynamics: Pakistan and Other Neighbors

Regional dynamics, and the involvement of outside powers, are central to the conflict in Afghanistan. The neighboring state widely considered most important in this regard is Pakistan, which has played an active, and by many accounts negative, role in Afghan affairs for decades. Pakistan's security services maintain ties to Afghan insurgent groups, most notably the Haqqani Network.56 Afghan leaders, along with U.S. military commanders, attribute much of the insurgency's power and longevity either directly or indirectly to Pakistani support; President Trump has accused Pakistan of "housing the very terrorists that we are fighting."57 U.S. officials have long identified militant safe havens in Pakistan as a threat to security in Afghanistan, though some Pakistani officials dispute that charge and note the Taliban's increased territorial control within Afghanistan itself.58

Pakistan may view a weak and destabilized Afghanistan as preferable to a strong, unified Afghan state (particularly one led by an ethnic Pashtun-dominated government in Kabul; Pakistan has a large and restive Pashtun minority).59 However, instability in Afghanistan could rebound to Pakistan's detriment; Pakistan has struggled with indigenous Islamist militants of its own. Afghanistan-Pakistan relations are further complicated by the presence of over a million Afghan refugees in Pakistan, as well a long-running and ethnically tinged dispute over their shared 1,600-mile border.60 Pakistan's security establishment, fearful of strategic encirclement by India, apparently continues to view the Afghan Taliban as a relatively friendly and reliably anti-India element in Afghanistan. India's diplomatic and commercial presence in Afghanistan—and U.S. rhetorical support for it—exacerbates Pakistani fears of encirclement. Indian interest in Afghanistan stems largely from India's broader regional rivalry with Pakistan, which impedes Indian efforts to establish stronger and more direct commercial and political relations with Central Asia. India has been the largest regional contributor to Afghan reconstruction, but New Delhi has not shown an inclination to pursue a deeper defense relationship with Kabul.

Since late 2018, the Trump Administration has been seeking Islamabad's assistance in facilitating U.S. talks with the Taliban. One important action taken by Pakistan was the October 2018 release of Taliban co-founder Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, who was captured in Karachi in a joint U.S.-Pakistani operation in 2010. Khalilzad said in February 2019 that Baradar's release "was my request," and later thanked Pakistan for facilitating the travel of Taliban figures to talks in Doha.61 Baradar went on to sign the U.S.-Taliban agreement alongside Khalilzad. A biannual Department of Defense report on Afghanistan released in January 2020 asserted that "Pakistan is supporting the Afghan reconciliation," describing Pakistan's role as "constructive but limited."62

Afghanistan largely maintains cordial ties with its other neighbors, notably the post-Soviet states of Central Asia, whose role in Afghanistan has been relatively limited but could increase.63 In the past two years, multiple U.S. commanders have warned of increased levels of assistance, and perhaps even material support, for the Taliban from Russia and Iran, both of which cite IS presence in Afghanistan to justify their activities.64 Both nations were opposed to the Taliban government of the late 1990s, but reportedly see the Taliban as a useful point of leverage vis-a-vis the United States. Afghanistan may also represent a growing priority for China in the context of broader Chinese aspirations in Asia and globally.65

Economy and U.S. Aid

Economic development is pivotal to Afghanistan's long-term stability, though indicators of future growth are mixed. Decades of war have stunted the development of most domestic industries, including mining.66 The economy has also been hurt by a steep decrease in the amount of aid provided by international donors. Afghanistan's gross domestic product (GDP) has grown an average of 7% per year since 2003, but growth rates averaged between 2% and 3% in recent years. Social conditions in Afghanistan remain equally mixed. On issues ranging from human trafficking to religious freedom to women's rights, Afghanistan has, by some accounts, made significant progress since 2001, but future prospects in these areas remain uncertain.

Congress has appropriated nearly $137 billion in aid for Afghanistan since FY2002, with about 63% for security and 26% for development (with the remainder for civilian operations and humanitarian aid).67 The Administration's FY2021 budget requests $4 billion for the ANDSF, $250 million in Economic Support Funds, and smaller amounts to help the Afghan government with other tasks like counternarcotics.68 These figures represent a decrease from both the FY2020 request, as well as FY2019 enacted levels. Other than ANDSF funding and other DOD contributions, these figures are not included in the cost of U.S. combat operations (including related regional support activities), which was estimated at a total of $776 billion since FY2002 as of September 2019, according to the DOD's Cost of War report. In its FY2021 budget request, the Pentagon included $14 billion in direct war costs in Afghanistan (down from the FY2020 request of $18.6 billion), as well as $32.5 billion in "enduring requirements" and $16 billion in Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding for "base requirements;" it is unclear how much of the latter two figures is for Afghanistan versus other theaters.

Outlook

The February 29, 2020, signing of the U.S.-Taliban agreement represents a significant moment for Afghanistan and U.S. policy there. Still, U.S. officials caution that the agreement is "just a first step," and shifts in political and/or security dynamics may alter the will of various parties to abide by the agreement.69 In any event, while the U.S.-Taliban agreement envisions intra-Afghan talks that nearly all observers describe as essential to bringing lasting peace to Afghanistan, concrete progress towards those talks remain elusive.

U.S. officials generally say that the Taliban do not pose an existential threat to the Afghan government, given the current military balance. That dynamic could change if the United States alters the level or nature of its troop deployments in Afghanistan (per the U.S.-Taliban agreement) or reduces funding for the ANDSF. President Ghani has said, "[W]e will not be able to support our army for six months without U.S. [financial] support."70 Notwithstanding direct U.S. support, Afghan political dynamics, particularly the willingness of political actors to directly challenge the legitimacy and authority of the central government, even by extralegal means, may pose a serious threat to Afghan stability in 2020 and beyond, regardless of Taliban military capabilities. Increased political instability, fueled by questions about the central government's competence, continued divisions among Afghan elites, and rising ethnic tensions, may pose as serious a threat to Afghanistan's future as the Taliban does.

A potential collapse of the Afghan military and/or the government that commands it could have significant implications for the United States, particularly given the nature of negotiated security arrangements. Regardless of how likely the Taliban would be to gain full control over all, or even most, of the country, the breakdown of social order and the fracturing of the country into fiefdoms controlled by paramilitary commanders and their respective militias may be plausible, even probable. Afghanistan experienced a similar situation nearly 30 years ago. Though Soviet troops withdrew from Afghanistan by February 1989, Soviet aid continued, sustaining the communist government in Kabul for nearly three years. However, the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991 ended that aid, and a coalition of mujahedin forces overturned the government in April 1992.71 Almost immediately, mujahedin commanders turned against each other, leading to a complex civil war during which the Taliban was founded, grew, and took control of most of the country, eventually offering sanctuary to Al Qaeda. While the Taliban and Al Qaeda are still closely aligned, Taliban forces have clashed repeatedly with the Afghan Islamic State affiliate. Under a more unstable future scenario, alliances and relationships among these and other groups could evolve, offering new opportunities to transnational terrorist groups.

The Trump Administration has described U.S. policy in Afghanistan as "grounded in the fundamental objective of preventing any further attacks on the United States by terrorists enjoying safe haven or support in Afghanistan."72 For years, some analysts have challenged that line of reasoning, describing it as a strategic "myth" and arguing that "the safe haven fallacy is an argument for endless war based on unwarranted worst-case scenario assumptions."73 Some of these analysts and others dismiss what they see as a disproportionate focus on the military effort, arguing that U.S. policy goals like countering narcotics and safeguarding human rights are "not objectives that the U.S. military…is well suited to addressing."74

Core issues for Congress in Afghanistan include Congress's role in authorizing, appropriating funds for, and overseeing U.S. military activities, aid, and regional policy implementation. Additionally, Members of Congress may examine how the United States can leverage its assets, influence, and experience in Afghanistan, as well as those of Afghanistan's neighbors and international organizations, to encourage more equal, inclusive, and effective governance. Congress also could seek to help shape the U.S. approach to talks with the Taliban, or to potential negotiations aimed at altering the Afghan political system, through oversight, legislation, and public statements.

In light of the U.S.-Taliban agreement, Members of Congress and other U.S. policymakers may reassess notions of what success in Afghanistan looks like, examining how potential outcomes might harm or benefit U.S. interests, and the relative levels of U.S. engagement and investment required to attain them.75 The Washington Post's December 2019 publication of the "Afghanistan Papers" (largely records of SIGAR interviews conducted as part of a lessons learned project) ignited debate, including reactions from some Members of Congress, on these very issues (for more, see CRS Report R46197, The Washington Post's "Afghanistan Papers" and U.S. Policy: Main Points and Possible Questions for Congress, by Clayton Thomas).

How Afghanistan fits into broader U.S. strategy is another issue on which Members might engage, especially given the Administration's focus on strategic competition with other great powers.76 Some analysts recognize fatigue over "endless wars" like that in Afghanistan but argue against a potential U.S. retrenchment that could create a vacuum Russia or China might fill.77 Others describe the U.S. military effort in Afghanistan as a "peripheral war," and suggest that "the billions being spent on overseas contingency operation funding would be better spent on force modernization and training for future contingencies."78

Appendix. U.S. Strikes by Month, July-October 2019

|

|

Source: Created by CRS. Data from NATO Resolute Support Strike Summaries; boundaries from GADM. Note: According to Resolute Support, summaries include "all strikes conducted by fighter, attack, bomber, rotary-wing, or remotely piloted aircraft, rocket-propelled artillery and ground-based tactical artillery." Resolute Support defines a strike as "one or more kinetic engagements that occur in roughly the same geographic location to produce a single, sometimes cumulative effect in that location" against the Taliban and other armed groups. |