Introduction

Sequestration is the automatic reduction (i.e., cancellation) of certain federal spending, generally by a uniform percentage.1 The sequester is a budget enforcement tool that Congress established in the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (BBEDCA, also known as the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act; P.L. 99-177, as amended) intended to encourage compromise and action, rather than actually being implemented (also known as triggered).2 Generally, this budget enforcement tool has been incorporated into laws to either discourage or encourage certain budget objectives or goals. When these goals are not met, either through the enactment of a law or lack thereof, a sequester is triggered and certain federal spending is reduced.

Sequestration is of recent interest due to its current use as an enforcement mechanism for three budget enforcement rules created by the Statutory Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2010 (Statutory PAYGO; P.L. 111-139) and the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25). Currently, only the BCA mandatory sequester has been triggered and is in effect. However, the Statutory PAYGO sequester and the BCA discretionary sequester are current law and can be triggered if the budget enforcement rules are broken.

Medicare, which is a federal program that pays for covered health care services of qualified beneficiaries,3 is subject to a reduction in federal spending associated with the implementation of these three sequesters, although special rules limit the extent to which it is impacted.

This report begins with an overview of budget sequestration and Medicare before discussing how budget sequestration has been implemented across the different parts of the Medicare program. Additionally, this report provides appendixes that include references to additional Congressional Research Service (CRS) resources related to this report and budget terminology definitions, as defined by BBEDCA.

Budget Sequestration

Under current law, sequestration is a budget enforcement tool that occurs because certain budgetary goals have not been met. When a sequester is triggered, all applicable budget accounts, unless exempted by law, are reduced by a certain percentage amount for a fiscal year.4 The percentage reduction varies between and within budget accounts depending on the categories of funding, as described below, contained within each budget account.

After identifying each category of funding within a budget account, sequestration reductions are spread evenly across all budget account subcomponents referenced in committee reports, budget justifications, and/or Presidential Detailed Budget Estimates – also known as programs, projects or activities.5 For budget accounts that contain only one category of funding, all sequestrable funds are reduced by the same corresponding percentage. For accounts that contain multiple categories of funding, the total amount of each category of sequestrable funds is reduced by its corresponding percentage. The reduced budget resources are usually permanently cancelled.6

As currently used, a sequester applies to either discretionary or mandatory spending. Discretionary spending is associated with most funds provided by annual appropriations acts. While all discretionary spending is subject to the annual appropriations process, only a portion of mandatory spending is provided in appropriations acts.7 Mandatory spending is generally provided by permanent laws, such as the Social Security Act which made indefinite budget authority permanently available for Medicare benefit payments.8 Some federal programs, such as Medicare, can receive both discretionary and mandatory funding.

In the event that a sequester is triggered, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is responsible for calculating the across-the-board percentage reductions, and calculates separate percentages for Medicare, other nondefense, and defense funding.9 Due to sequestration rules, which are covered later in this report, mandatory Medicare benefit payments receive a specific percentage reduction different from other types of federal spending.

The methodologies used to calculate these percentages and the sequestered amounts are published in a report produced by OMB. Once the President issues a sequestration order, the associated report is made available to the public and transmitted to Congress.10

Budget Enforcement Rules

Currently, there are three budget enforcement rules that can trigger sequestration. Two were established by the BCA and one was established by Statutory PAYGO. The three rules and their corresponding sequesters can be summarized as follows (and are presented in Table 1):

Budget Control Act

The BCA established a bipartisan Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction (Joint Committee), which was responsible for developing legislation that would reduce the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion from FY2012 to FY2021.11 However, the Joint Committee was unable to achieve this goal; therefore, Congress and the President were unable to enact corresponding deficit reduction legislation by a date specified in the law. As a result, two types of spending reductions were automatically triggered.12

One automatic spending reduction involved the sequestration of certain mandatory spending from FY2013 to FY2021. Through subsequent legislation, including, most recently, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA 2019; P.L. 116-37), Congress extended this reduction through FY2029.13 (This reduction is referred to in this report as the "BCA mandatory sequester".)

Additionally, the BCA established statutory limits on discretionary spending for FY2012-FY2021.14 These discretionary spending limits (discretionary caps) restrict the amount of spending permitted through the annual appropriations process for defense and nondefense programs. Any breach of these discretionary caps results in the sequestration of nonexempt discretionary funding. (This reduction is referred to in this report as the "BCA discretionary sequester".) This was triggered once in FY2013,15 and can be triggered again if discretionary caps are breached in any fiscal year through FY2021 and Congress does not take action to raise these caps. Most recently, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123) increased the discretionary spending caps for FY2018 and FY2019 so they would not be breached, and BBA 2019 increased the caps for FY2020 and FY2021.

Statutory PAYGO

The Statutory PAYGO Act established a budget enforcement mechanism generally requiring that legislation affecting direct (mandatory) spending and revenues does not have the effect of increasing the deficit over a 5- and/or 10-year period. If such legislation were to become law, a sequester of certain mandatory spending would be required. This budget enforcement rule does not have a sunset date and therefore remains in effect under current law. (This reduction is referred to in this report as Statutory PAYGO sequester.)

Although Congress has passed legislation that has been estimated to increase the deficit since the law went into effect, the Statutory PAYGO sequester has never been triggered, as Congress has voted to prohibit the effects of specific legislation from being counted under the normal operations of the Statutory PAYGO Act. A recent example of this is BBA 2019,16 which included language to reduce the "scorecards" tallying the total impact of legislation on the deficit to zero.

|

Funding Types |

Medicare Programs |

Sequester |

Enforcement Rule |

Sequester Percentage Cap |

Current Status |

|

Mandatory |

Parts A, B, C, and D Benefits; MIP HCFAC; Non-MIP HCFAC; Administration |

Statutory PAYGO |

If revenue and/or mandatory spending legislation that projects to increase the deficit over a 5 and/or 10-year period is enacted, a sequester of certain mandatory spending would be ordered. |

4% for benefit payments and MIP HCFAC. None for other spending. |

Current law but not triggered. |

|

BCA Mandatory Sequester |

If the Joint Select Committee was unsuccessful at reducing the federal deficit by $1.2 trillion from FY2012-FY2021, mandatory sequestration would be implemented and discretionary limits would be established (with any breaches enforced through sequestration). |

2% for benefit payments and MIP HCFAC. None for other spending.a |

Currently triggered and in effect through FY2029.b |

||

|

Discretionary |

Non-MIP HCFAC; Administration |

BCA Discretionary Sequester |

None. |

Discretionary limits currently in place through FY2021 but spending levels not expected to violate limits (caps) and sequester not currently triggered.c |

Source: CRS.

Notes: Programs that appear in both categories are funded using mandatory and discretionary spending authority. In addition to the Medicare sequestration cap, other sequestration rules prohibit sequestration effects from being included in the determination of adjustments to Medicare payment rates, and explicitly exempt Part D low-income subsidies, Part D catastrophic subsidies (reinsurance) and Qualified Individual premiums from sequestration. BCA refers to Budget Control Act. Discretionary Administration includes amounts for payments to contractors to process providers' claims, beneficiary outreach and education, and maintenance of Medicare's information technology infrastructure. HCFAC refers to the Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program, which is responsible for activities that fight health care fraud and waste and is funded through discretionary and mandatory resources. Mandatory Administration includes, among other things, amounts for quality improvement organizations. Medicare Benefit Payments are defined by BBEDCA as all payments for programs and activities under Title XVIII of Social Security Act, including the Medicare Integrity Program. MIP HCFAC refers to the Medicare Integrity Program, which focuses on combating fraud in Medicare. Non-MIP HCFAC refers to all HCFAC spending other than MIP.

a. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA 2019; P.L. 116-37) specifies that the non-administrative Medicare sequester percentage cap under the BCA mandatory sequester will be 4% during the first six months of the FY2029 sequestration order and 0% for the next six months of the order. See BBEDCA §251A(6)(C).

b. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; P.L. 113-67) extended the BCA mandatory sequester through FY2023. A law modifying the cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) for certain military retirees (P.L. 113-82) extended the sequester through FY2024. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74) extended the sequester through FY2025. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123) extended the sequester through FY2027, and BBA 2019 extended the sequester through FY2029.

c. Several laws established new caps that were adhered to, thus not requiring any sequestration in the relevant years. These include BBA 2013 for FY2014 and FY2015: BBA 2015 for FY2016 and FY2017: BBA 2018 for FY2018 and FY2019, and BBA 2019 for FY2020 and FY2021.

For more information on budget sequestration, see CRS Report R42050, Budget "Sequestration" and Selected Program Exemptions and Special Rules, CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, and CRS Report R45941, The Annual Sequester of Mandatory Spending through FY2029.

Medicare Overview

Medicare, which is a federal program that pays for certain health care services of qualified beneficiaries, is subject to sequestration, although special rules limit the extent to which it is impacted. Due to the varying payment structures of the four parts of the program, sequestration is applied differently across Medicare.

Medicare was established in 1965 under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act to provide hospital and supplementary medical insurance to Americans aged 65 and older. Over time, the program has been expanded to also include certain disabled persons, including those with end-stage renal disease. In FY2019, the program covered an estimated 61 million persons (52 million aged and 9 million disabled).17

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that total Medicare spending will be about $772 billion in FY2019 and will increase to about $1,500 billion in FY2029.18 Almost all Medicare spending is mandatory spending that is primarily used to cover benefit payments (i.e., payments to health care providers for their services), administration, and the Medicare Integrity Program (MIP). The remaining Medicare outlays are discretionary and used almost entirely for other administrative activities that are described in more detail later in this report.

Medicare consists of four distinct parts:

- 1. Part A (Hospital Insurance, or HI) covers inpatient hospital services, skilled nursing care, hospice care, and some home health services. Most persons aged 65 and older are automatically entitled to premium-free Part A because they or their spouse paid Medicare payroll taxes for at least 40 quarters (10 years) on earnings covered by either the Social Security or the Railroad Retirement systems. Part A services are paid for out of the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, which is mainly funded by a dedicated 2.9% payroll tax on earnings of current workers, shared equally between employers and workers.

- 2. Part B (Supplementary Medical Insurance, or SMI) covers a broad range of medical services, including physician services, laboratory services, durable medical equipment, and outpatient hospital services. Enrollment in Part B is optional, but most beneficiaries with Part A also enroll in Part B. Part B benefits are paid for out of the Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund, which is primarily funded through beneficiary premiums and federal general revenues.

- 3. Part C (Medicare Advantage, or MA) is a private plan option that covers all Parts A and B services, except hospice. Individuals choosing to enroll in Part C must be enrolled in Parts A and B. About one-third of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in MA. Part C is funded through both the HI and SMI trust funds.

- 4. Part D is a private plan option that covers outpatient prescription drug benefits. This portion of the program is optional. About three-quarters of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in Medicare Part D or have coverage through an employer retiree plan subsidized by Medicare. Part D benefits are also paid for out of the Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund, which is primarily funded through beneficiary premiums, federal general revenues, and state transfer payments.

For more information on the Medicare program, see CRS Report R40425, Medicare Primer.

Beneficiary Costs

Beneficiaries are responsible for paying Medicare Parts B and D premiums, as well as other out-of-pocket costs, such as deductibles and coinsurance,19 for services provided under all parts of the Medicare program.20 Under Medicare Parts A, B and D, there is no limit on beneficiary out-of-pocket spending, and most beneficiaries have some form of supplemental insurance through private Medigap plans, employer-sponsored retiree plans, or Medicaid to help cover a portion of their Medicare premiums and/or deductibles and coinsurance. Medicare Advantage has limits on out-of-pocket spending.

Provider and Plan Payments

Under Medicare Parts A and B, the government generally pays providers directly for services on a fee-for-service basis using different prospective payment systems and fee schedules.21 Under Parts C and D, Medicare pays private insurers a monthly capitated per person amount to provide coverage to enrollees, regardless of the amount of services used. The capitated payments are adjusted to reflect differences in the relative cost of sicker beneficiaries with different risk factors including age, disability, or end-stage renal disease.

Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program

The Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program (HCFAC) was established by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA; P.L. 104-191) and is responsible for activities that fight health care fraud and waste. HCFAC is funded using both mandatory and discretionary funds and consists of three programs: (1) the HCFAC program, which finances the investigative and enforcement activities undertaken by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the HHS Office of Office of Inspector General, the Department of Justice, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, (2) Medicaid Oversight, and (3) MIP.

Historically, MIP has focused on combating fee-for-service fraud in Medicare Parts A and B. However, increases in private Medicare enrollment—Parts C and D—have expanded program integrity efforts into capitated payment systems as well.

While HCFAC is not a part of the Medicare program, MIP is authorized by the same title of the Social Security Act as Medicare and focuses entirely on the program. As a result, this portion of HCFAC is treated as a part of Medicare benefit payments under a sequestration order and is subject to the Medicare mandatory sequestration percentage limits.22

Administrative Spending

The administration of Medicare is funded through a combination of discretionary and mandatory resources that are subject to reductions under a discretionary or mandatory sequestration order, respectively. Discretionary administration funding includes amounts for payments to contractors to process providers' claims, beneficiary outreach and education, and maintenance of Medicare's information technology infrastructure. Mandatory administration funding includes amounts for quality improvement organizations and Part B premium payments for Qualifying Individuals (QI).23

Medicare Sequestration Rules

Special rules limit the total effect of budget sequestration on Medicare (see Table 1). Most notably, BBEDCA, as amended by the BCA, prohibits Medicare benefit payments from being reduced by more than 2% under a BCA mandatory sequestration order. Similarly, Statutory PAYGO prohibits Medicare benefit payments from being reduced by more than 4% under a Statutory PAYGO sequestration order.24 The cap does not apply to Medicare mandatory and discretionary administrative spending, which is subject to the unrestricted percentage reduction under both BCA and Statutory PAYGO sequestration orders.

Under the current mandatory sequestration order triggered by the BCA, the Medicare sequestration percentage is capped at 2%.25 Therefore, as OMB determines the percentage reductions for each budget category through FY2029, Medicare benefit payments cannot be reduced by more than 2%; as such, another budget category may be subject to a higher percentage reduction in order to achieve the necessary amount of savings.

More specifically, if OMB determines that total nonexempt, nondefense mandatory funds need to be reduced by a percentage larger than 2% in order to achieve necessary savings under a BCA sequestration order for a given year, then a 2% reduction would be made to Medicare benefit spending, and the uniform reduction percentage for the remaining non-Medicare benefit, nonexempt, nondefense mandatory programs would be recalculated and increased by an amount to achieve the necessary level of reductions. If the uniform percentage reduction needed to achieve the total amount of savings is less than 2%, then the determined percentage would be applied to Medicare as well as to all other nonexempt non-Medicare nondefense mandatory spending. Of note, if a mandatory sequestration order were triggered by Statutory PAYGO, the process would be the same, but the reduction of payments for Medicare benefits would be capped at 4%.26

In addition to these percentage caps, BBEDCA also prohibits Statutory PAYGO and BCA mandatory sequestration effects from being included in the determination of annual adjustments to Medicare payment rates established under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act.27 (See "Reductions in Benefit Spending".)

Finally, certain Medicare programs and activities are explicitly exempted from Statutory PAYGO and BCA sequestration orders. Specifically, Part D low-income subsidies,28 Part D catastrophic subsidies (reinsurance),29 and QI premiums cannot be reduced under a mandatory sequestration order.30

Medicare Sequester Execution

Timing

Once a sequester is triggered, OMB issues a sequestration order for, at most, one fiscal year, and subsequent orders are reissued for each fiscal year, as necessary. These orders can be issued either before or during the fiscal year in which they apply, depending on the trigger.

Reductions in budget resources are to be made during the effective period of a sequestration order; however special rules differentiate when a sequestration order is implemented for benefit payments. As a result, sequestration orders are applied to Medicare benefit payments on a different timeline than other mandatory and discretionary Medicare funds (i.e., Medicare administration and HCFAC).

Once OMB issues a sequestration order, Medicare benefit payments are sequestered beginning on the first date of the following month and remain in effect for all services furnished during the following one-year period.31 In the event that a subsequent sequester order is issued prior to the completion of the first order, the subsequent order begins on the first day after the initial order has been completed.

As an example, the first BCA mandatory sequester order (FY2013) was issued on March 1, 2013, and took effect April 1, 2013. It remained in effect through March 31, 2014. The FY2014 order was issued on April 10, 2013, (corrected on May 20, 2013) and was in effect from April 1, 2014, to March 31, 2015.32

All other sequestrable funding is reduced only during the fiscal year associated with the sequester report. Using the same example, the first BCA mandatory sequester order (FY2013) reduced appropriate administrative spending from March 1, 2013, to September 30, 2013. The second order for FY2014 sequestered funds from October 1, 2013, to September 30, 2014.

While OMB uses current law to determine the amount of funds available to be sequestered and corresponding percentage reductions, actual Medicare outlays will not be known until after the end of the fiscal year. Since sequestration orders are issued either before or during the fiscal year in which they are applicable, OMB estimates the total sequestrable budget authority for Medicare, and other accounts with indefinite budget authority, in order to determine necessary sequestration percentages.33

If Medicare outlays exceed the estimated amount included in a sequestration order for that fiscal year, the additional outlays are sequestered at the established percentage for that fiscal year. If Medicare outlays are determined to be less than the estimated amount, no adjustments are made to the sequestration order. In other words, OMB does not adjust sequestration percentages for any category of budget authority once actuals are realized for accounts with indefinite budget authority. Similarly, OMB does not adjust future orders to account for any previous discrepancies between estimates and actuals.

Reductions in Benefit Spending

Parts A and B

Under Medicare Parts A and B, participating providers, such as hospitals and physicians, are paid by the federal government on a fee-for-service basis for services provided to a beneficiary. According to guidance issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), any sequestration reductions are to be made to claims after determining coinsurance, deductibles, and any applicable Medicare Secondary Payment adjustments.34 Therefore, sequestration applies only to the portion of the payment paid to providers by Medicare; the beneficiary cost-sharing amounts and amounts paid by other insurance are not reduced.

As an example, if the total allowed payment for a particular service is $100 and the beneficiary has a 20% co-insurance, the beneficiary would be responsible for paying the provider the full $20 in co-insurance. The remaining 80% that is paid by Medicare would be reduced by 2% under the FY2018 sequestration order, or $1.60 in this example, resulting in a total Medicare payment of $78.40. In total, the provider would receive a payment of $98.40. This reduced payment is considered payment in full and the Medicare beneficiary is not expected to pay higher copayments to make up for the reduced Medicare payment.35

Part A inpatient services are considered to be furnished on the date of the individual's discharge from the inpatient facility. For services paid on a reasonable cost basis,36 the reduction is to be applied to payments for such services incurred at any time during the sequestration period for the portion of the cost reporting period that occurs during the effective period of the order. For Part B services provided under assignment,37 the reduced payment is to be considered payment in full and the Medicare beneficiary will not pay higher copayments to make up for the reduced amount.38

Medicare non-participating providers, which are providers that do not elect to accept Medicare payments on all claims in a given year, are not subject to the same rules. Medicare non-participating providers receive a lower reimbursement rate from Medicare on all services provided and may charge beneficiaries a limited amount more (balance bill charge) than the fee schedule amount on non-assigned claims.39 In these instances, instead of the Medicare check being sent to the provider, a check that incorporates the 2% reduction is mailed to the patient. The patient must then pay the provider an amount that incorporates the sequestered amount. More specifically, as payment, the beneficiary is responsible for paying the provider the amount listed on the check, any cost sharing, balance bill charges, and the sequestered amounts taken out of the provider check.40

Annual adjustments to Medicare payment rates are determined without incorporating sequestration.41 However, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission does incorporate the effects of sequestration when assessing the adequacy of provider payments.42 The commission uses these annual assessments to develop payment adjustment recommendations to the HHS Secretary and/or Congress.

Part C

Under Medicare Advantage, private health plans are paid a per person monthly amount to provide all Medicare-covered benefits, except hospice, to beneficiaries who enroll in their plan. These capitated monthly payments are made to MA plans regardless of how many or how few services beneficiaries actually use. The plan is at risk if costs for all of its enrollees exceed program payments and beneficiary cost sharing; conversely, the plan can generally retain savings if aggregate enrollee costs are less than program payments and cost sharing.

With respect to sequestration, reductions are uniformly made to the monthly capitated payments to the private plans administering Medicare Advantage (Medicare Advantage Organizations or MAOs). These fixed payments are determined every year with CMS approval through an annual "bid process" and the amounts can vary depending on the private plan.43

In general, CMS payments to MAOs are generally comprised of amounts to cover medical costs, administrative expenses, private plan profits, risk adjustments, and plan rebates to beneficiaries.44 MAOs have discretion to distribute any sequestration cut across these different components but must still adhere to their legal obligations.45

Some MAOs have attempted to pass the reduction in their capitation rates onto providers through lower reimbursement rates; however MAOs may be limited in their ability to do so.46 CMS provided instructions regarding the treatment of contract and non-contract providers that provide services under Part C. Specifically, "whether and how sequestration might affect an MAO's payments to its contracted providers are governed by the terms of the contract between the MAO and the provider."47 Therefore, in order for MAOs to reduce provider payments by the sequestered amount, specific language within a contract must allow the reduction or the contract would need to be renegotiated.

In certain instances, such as when beneficiaries receive emergency out-of-network care, MAOs need to reimburse the non-contracted providers; in such cases, the MAOs are required to pay at least the rate providers would have received if the beneficiaries had been enrolled in original Medicare. However, MAOs have the discretion of whether or not to incorporate sequestration cuts into payments to non-contracted providers for those services.48 Non-contracted providers must accept any payments reduced by the sequestration percentage as payment in full.

In addition, regulations in the annual bid process restrict MAO's potential responses to sequestration. Specifically, MAOs are limited to "reasonable" revenue margins and a set Medicare/non-Medicare profit margin discrepancy, among other requirements.49 Furthermore, MAOs are restricted from allowing sequestration to impact a beneficiary's plan benefits or liabilities,50 so it becomes difficult for MAOs to pass an entire sequestration cut onto beneficiaries through higher premiums or seek to offset lost revenue by increasing non-Medicare profits.

As HHS computes annual adjustments to Medicare payment rates, the Secretary cannot take into account any reductions in payment amounts under sequestration for the Part C growth percentage.51 In other words, plan payment updates are to be determined as if the reductions under sequestration have not taken place. This results in larger annual adjustments compared to baselines that incorporate sequestration cuts.

Part D

Under Medicare Part D, each plan receives a base capitated monthly payment, called a direct subsidy, which is adjusted to incorporate three risk-sharing mechanisms (low-income subsidies, individual reinsurance, and risk corridor payments). While each plan receives the same direct subsidy amount for each enrollee regardless of how many benefits an enrollee actually uses, plans receive different risk-sharing adjustments in their monthly payments. With respect to sequestration, reductions are made only to the direct subsidy amounts. Part D risk-sharing adjustments are exempt from sequestration and are therefore not reduced.52

Part D also contains a Retiree Drug Subsidy Program, which pays subsidies to qualified employers and union groups that provide prescription drug insurance to Medicare-eligible, retired workers. Instead of a capitated monthly payment, each sponsor receives a federal subsidy at the end of the year to cover a portion of gross prescription drug costs for each retiree during that year. Under this program, sequestration reductions are applied to the annual subsidy amount.53

Similar to Part C, the HHS Secretary is prohibited from taking into account any reductions in payment amounts under sequestration for purposes of computing the Part D annual growth rate.54

Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program

As noted, the HCFAC program is not part of Medicare but does receive mandatory and discretionary funds to ensure the programmatic integrity of the Medicare program. Under a BCA sequestration order of mandatory funds, MIP funds are treated as a part of Medicare benefit payments and are therefore subject to the Medicare 2% sequester limit. HCFAC mandatory funding that does not exclusively address Medicare is reduced by the nondefense mandatory sequester rate (5.9% in 2020), when applicable.

Administrative Expenses

Under either a mandatory or discretionary sequestration order, administrative spending within nonexempt Medicare and HCFAC programs is reduced by the nondefense rate determined by OMB (5.9% in 2020).

Medicare and the BCA Mandatory Sequester

Since the first BCA mandatory sequester order issued in FY2013, Medicare benefit payments have been subject to the 2% annual reduction limit established by the BCA. Nondefense mandatory budget authority reductions, which have applied to mandatory Medicare administrative spending, have fluctuated between 5.1% and 7.3% from FY2013 through FY2020. (See Table 2.)

Table 2. Mandatory Percentage Reductions Under Budget Control Act Sequestration Orders

(FY2013–FY2020)

|

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

|

|

Medicare |

2.0% |

2.0% |

2.0% |

2.0% |

2.0% |

2.0% |

2.0% |

2.0% |

|

Nondefense Mandatory (Medicare administrative spending and non-MIP HCFAC) |

5.1% |

7.2% |

7.3% |

6.8% |

6.9% |

6.6% |

6.2% |

5.9% |

|

Defense Mandatory |

7.9% |

9.8% |

9.5% |

9.3% |

9.1% |

8.9% |

8.7% |

8.6% |

Source: OMB Reports to Congress on the Joint Committee Sequestration for FY2013 to FY2020.

Notes: Defense Mandatory is any funding coded with a budget function of 050. Medicare Benefit Payments are defined by BBEDCA as all payments for programs and activities under Title XVIII of Social Security Act. The Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program (HCFAC) is responsible for activities that fight health care fraud and waste. Nondefense Mandatory includes all other government spending not defined as Medicare or Defense Mandatory. MIP refers to the Medicare Integrity Program, which is under HCFAC and focuses on combating fraud in Medicare.

In the FY2020 sequestration order, mandatory Medicare administrative expenses will be sequestered by the nondefense mandatory percentage, 5.9% in FY2020. The total reduction in Medicare administration budget authority, however, cannot be identified from the data presented in the OMB sequestration report.55

In total, Medicare benefit payments (not including administration) are estimated to account for 91% of all Medicare and non-Medicare resources available to be sequestered (sequestrable budget authority) under the FY2020 BCA mandatory sequester.56 Of the funds that are sequestered, Medicare benefit payments are estimated to account for 74% of the combined mandatory defense and nondefense sequestered funds.57

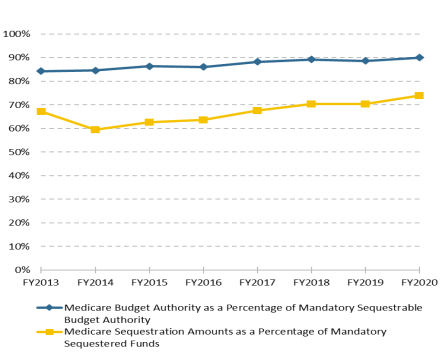

Traditionally, Medicare benefit payments comprise the largest single source of sequestered funds in a given mandatory sequestration order. In FY2020, Medicare benefit payments are estimated to account for the largest share of sequestrable budget authority and sequestered funds since the first BCA sequestration order was issued for FY2013, as shown in Figure 1.58

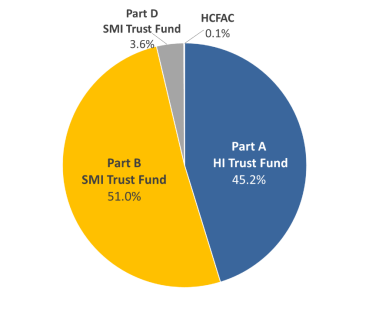

Figure 2 shows how the FY2020 BCA sequestration order is estimated to apply to the various parts of Medicare. It is worth noting that although Medicare Part C is sequestered, OMB sequestration orders delineate at the trust fund level and do not distinguish each Medicare part. Part C is funded out of both the Part A and Part B trust funds and is included in these totals. For reference, in FY2018, Medicare Advantage accounted for 30% of all HI Trust Fund benefit payments and 29% of all SMI Trust Fund benefit payments.59 These ratios could change in FY2020 based on actual spending.

CBO estimates that Medicare benefit payment outlays will increase 95% from FY2019 to FY2029 (from $761 billion to $1,483 billion), the last year of BCA mandatory sequestration.60 Most of this expected increase is due to an aging population and rising health care costs per person.61 Most of this increase would be subject to sequestration.

For more information on the Budget Control Act, see CRS Report R41965, The Budget Control Act of 2011, and CRS Report R42506, The Budget Control Act of 2011 as Amended: Budgetary Effects.

Appendix A. Additional CRS Resources

To gain a deeper understanding of the topics covered in this report, readers may also wish to consult the following CRS reports:

CRS Report R40425, Medicare Primer

CRS Report R43122, Medicare Financial Status: In Brief

CRS Report R45494, Medicare Advantage (MA)–Proposed Benchmark Update and Other Adjustments for CY2020: In Brief

CRS Report R40611, Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit

CRS Report 98-721, Introduction to the Federal Budget Process

CRS Report R41965, The Budget Control Act of 2011

CRS Report R42506, The Budget Control Act of 2011 as Amended: Budgetary Effects

CRS Report RL34424, The Budget Control Act and Trends in Discretionary Spending

CRS Insight IN11148, The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019: Changes to the BCA and Debt Limit

CRS Report R42050, Budget "Sequestration" and Selected Program Exemptions and Special Rules

CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions

CRS Report R45941, The Annual Sequester of Mandatory Spending through FY2029

CRS In Focus IF11332, FY2020 Mandatory Sequester Reduces Medicare $15.3 Billion, Other Mandatory Spending $5.39 Billion

CRS Report R41157, The Statutory Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2010: Summary and Legislative History

CRS Report R41510, Budget Enforcement Procedures: House Pay-As-You-Go (PAYGO) Rule

Appendix B. Budget Terminology Definitions

As defined by Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (BBEDCA; P.L. 99-177, as amended) and simplified where appropriate:

Budget Authority—Authority provided by federal law to enter into financial obligations that will result in immediate or future outlays involving federal government funds.

Budgetary Resources—An amount available to enter into new obligations and to liquidate them. Budgetary resources are made up of new budget authority (including direct spending authority provided in existing statute and obligation limitations) and unobligated balances of budget authority provided in previous years.

Discretionary Appropriations—Budgetary resources (except to fund direct-spending programs) provided in appropriation Acts.

Mandatory Spending—Also known as direct spending, refers to budget authority that is provided in laws other than appropriation acts, entitlement authority, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Medicare Benefit Payments—All payments for programs and activities under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act.

Revised Nonsecurity Category—Discretionary appropriations other than in budget function 050, often referred to as nondefense category.

Revised Security Category—Discretionary appropriations in budget function 050, often referred to as defense category.

Sequestration—The cancellation of budgetary resources provided by discretionary appropriations or direct spending laws.

For definitions of other budget terms mentioned in this report but not defined by BBEDCA, see U.S. Government Accountability Office, A Glossary of Terms Used in the Federal Budget Process, GAO-05-734SP, September 1, 2005, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/80/76911.pdf.