Overview

The Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (CFO Act) requires annual financial audits of federal agencies' financial statements to "assure the issuance of reliable financial information ... deter fraud, waste and abuse of Government resources ... [and assist] the executive branch ... and Congress in the financing, management, and evaluation of Federal programs."1 Agency inspectors general (IGs) are responsible for the audits and may contract with one or more external auditors.

The Department of Defense (DOD) completed its first agency-wide financial audit in FY2018 and recently completed its FY2019 audit. Comprehensive data for the FY2019 audit are not currently available. Therefore, this report focuses on DOD's FY2018 audit. Congressional interest in DOD's audits is particularly acute because DOD accounts for about half of federal discretionary expenditures2 and 15% of total federal expenditures.3

The Department of Defense Inspector General (DOD IG) contracted with nine Independent Public Accounting firms (IPAs) to conduct the FY2018 and FY2019 audit. The IPAs conducted 24 separate audits within DOD (see Table 1 for each of the component-level audit opinions).4

In both FY2018 and FY2019 audits, the DOD IG issued the overall agency-wide opinion of disclaimer of opinion—meaning auditors could not express an opinion on the financial statements because the financial information was not sufficiently reliable. DOD components that received a disclaimer of opinion represent approximately 56% of the reported DOD assets and 90% of the reported DOD budgetary resources.5

|

Types of Audit Opinion Although many entities in the federal government usually receive an unmodified opinion, auditors may express other types of opinions based on the circumstances. There are four types of audit opinions: Unmodified Opinion. An unmodified opinion (clean opinion) states that the financial statements present fairly, in all material respects, the consolidated balance sheets, related consolidated statements of net cost and changes in net position, combined statements of budgetary resources, and related notes to the consolidated financial statements in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). This opinion is expressed in a standard report. In certain circumstances, explanatory language might be added to the auditor's standard report, which does not affect the unmodified opinion. Modified Opinion. A modified opinion states that, except for the effects of the matter(s) identified in the opinion, the financial statements present fairly in all material respects in conformity with GAAP. Disclaimer of Opinion. A disclaimer of opinion states that the auditor does not express an opinion on the financial statements. The auditor's report should give all of the substantive reasons for the disclaimer. Some of the possible reasons for a disclaimer of opinion include financial statements not conforming to GAAP and financial management systems that are unable to provide sufficient evidence for the auditor to express an opinion. Adverse Opinion. An adverse opinion states that the financial statements do not present fairly in accordance with GAAP. The auditor concludes that misstatements in the financial statements are both material and significant to the financial statements. |

|

Audit Component |

Audit Opinion |

|

Army, General Fund |

Disclaimer |

|

Army, Working Capital Fund |

Disclaimer |

|

Navy, General Fund |

Disclaimer |

|

Navy, Working Capital Fund |

Disclaimer |

|

Marine Corps, General Fund |

Disclaimer |

|

Air Force, General Fund |

Disclaimer |

|

Air Force, Working Capital Fund |

Disclaimer |

|

Army Corps of Engineers-Civil Works |

Unmodified |

|

Military Retirement Fund |

Unmodified |

|

Defense Health Agency-Contract Resource Management |

Unmodified |

|

Defense Health Program |

Disclaimer |

|

Defense Logistics Agency, General Fund |

Disclaimer |

|

Defense Logistics Agency, Working Capital Fund |

Disclaimer |

|

Defense Logistics Agency Strategic Materials |

Disclaimer |

|

DOD Classified |

Disclaimer |

|

Special Operations Command |

Disclaimer |

|

Medicare-Eligible Retiree Health Care Fund |

Modified |

|

Transportation Command |

Disclaimer |

|

Defense Information Systems Agency, General Fund |

Disclaimer |

|

Defense Information System Agency, Working Capital Fund |

Disclaimer |

|

Defense Commissary Agency |

Qualified |

|

Defense Finance and Accounting Service, Working Capital Fund |

Unmodified |

|

Defense Contract Audit Agency |

Unmodified |

|

DOD Office of Inspector General |

Unmodified |

Source: Department of Defense, Financial Improvement and Audit Remediation (FIAR) Report, June 2019, at https://comptroller.defense.gov/ODCFO/FIARPlanStatusReport.aspx.

Notes: A working capital fund is a type of revolving fund used to finance operations that function like commercial business activities, such as equipment maintenance, supply and storage activities, and transporting equipment and people. General Fund consists of receipt accounts used to account for collections not dedicated to specific purposes, and expenditure accounts used to record financial transactions arising primarily under congressional appropriations or authorizations to spend general revenues.

DOD expected to receive a disclaimer of opinion for FY2018 and FY2019.6 The department has stated it could take a decade to receive an unmodified (clean) audit opinion.7 The federal government as a whole is unable to receive a clean opinion on its financial report because agencies with significant assets and budgetary costs, such as DOD, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the Railroad Retirement Board, have each received a disclaimer of opinion in recent years.8 The federal government as a whole potentially could receive a clean audit opinion without all government agencies receiving a clean audit opinion; however, the size of the DOD budget—$708 billion in FY2019—prevents an overall clean opinion without DOD receiving a clean audit opinion.9

DOD employs 2.9 million military and civilian employees at approximately 4,800 DOD sites in 160 countries.10 DOD IG personnel and auditors from IPAs visited over 600 sites, sent over 40,000 requests for documentation, and tested over 90,000 sample items.11 DOD spent $413 million to conduct the FY2018 audit: $192 million on audit fees for the IPAs and $221 million on government costs to support the audit. DOD spent an additional $406 million on audit remediation and $153 million on financial system fixes.12

|

GAO's High-Risk List The FY2018 audit is not the first time DOD's financial management has been questioned. DOD has been on the Government Accountability Office's (GAO's) high-risk list since 1995.13 Agencies on the high-risk list are considered more vulnerable to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement. GAO's high-risk list is separate from the audit opinion issued by the independent public accounting firms; see Table 1. The high-risk list examines both financial management and programmatic issues, but it is not an audit. GAO issues the high-risk list every two years to keep attention on government operations that are vulnerable to "fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement, or that are in need of transformation to address economy, efficiency, or effectiveness challenges."14 GAO's efforts are supported by the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, and by the House Committee on Oversight and Reform. According to GAO, addressing the high-risk problems has the potential to save taxpayers billions of dollars, improve service to the public, and strengthen government performance and accountability.15 GAO uses five criteria to assess progress in addressing high-risk areas: (1) leadership commitment, (2) agency capacity, (3) an action plan, (4) monitoring efforts, and (5) demonstrated progress.16 In addition to DOD financial management, GAO has identified other issues at DOD on the high-risk list:

|

What Is a Financial Audit?

Financial statements are the primary way for an entity to communicate its financial performance to its stakeholders. How each line item on a financial statement (e.g., property) should be valued and reported is based on Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), an agreement among practitioners (i.e., accountants, auditors, and regulators).

In a financial audit, a private or public entity hires an independent auditor to provide reasonable assurance to all stakeholders that its financial statements are free of material misstatement, whether caused by error or fraud.17 Auditors form opinions by examining the types of risks an organization might face and the controls in place to mitigate those risks. Auditors give unbiased professional opinions on whether financial statements and related disclosures are fairly stated in all material18 respects for a given period of time in accordance with GAAP.

As mentioned previously, the CFO Act requires federal agencies' financial statements to be audited annually.19 The CFO Act assigns responsibility for audits to agency inspectors general (IGs), but an IG may contract with one or more external auditors to perform an audit. The annual audit can inform Congress and the agency about its business processes and areas for improvement.

An audit of DOD can provide benefits, such as (1) effective and efficient internal operations that can lead to reducing costs and improving operational readiness; (2) improved allocation of assets and financial resources that can enhance DOD's decisionmaking and ability to support the Armed Forces; and (3) improved compliance with statutes and financial regulations.20

For each line item on a financial statement and notes to the financial statement, an auditor will examine a sample of the underlying economic events to determine the reported information's accuracy. The Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB) promulgates financial reporting and accounting standards for federal government entities, and GAO establishes federal auditing standards, including for federal grant recipients in state and local governments.21

GAO issues the Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (GAGAS), also commonly known as the Yellow Book, to provide a framework for conducting federal government audits. The Yellow Book requires auditors to consider the visibility and sensitivity of government programs in determining the materiality threshold. Similar to requirements in the private sector, GAGAS requires federal financial reporting to disclose compliance with laws, regulations, contracts, and grant agreements that have a material effect on financial statements.

Before auditors examine an entity's financial statement, they first evaluate its Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems' (information technology systems') access control and reliability, as well as internal controls. ERP refers to an enterprise-wide information system used to manage and coordinate all of an entity's resources, information, and functions from shared data stores, including financial information.22 Auditing ERP systems is a critical aspect of evaluating an entity's internal controls.

Internal Control in the Federal Government

Internal control is a series of integrated actions that management uses to guide an entity's operations. Under GAO standards, effective internal controls should require management to use dynamic, integrated, and responsive judgment rather than rigidly adhering to past policies and procedures.23 The success or failure of an entity's internal controls depends on its personnel. Management is responsible for designing effective internal controls, but implementation depends on all personnel understanding, implementing, and operating an effective internal control system.24

Federal agencies have been required to report to Congress25 on internal controls since the Federal Managers' Financial Integrity Act of 1982.26 In addition, the Federal Financial Management Improvement Act of 199627 requires agencies to report to Congress on the effectiveness of internal control over financial management systems.

GAO's Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government (also known as the Green Book) provides the overall framework for designing, implementing, and operating an effective internal control system.28 An audit of an entity's internal controls includes computer systems at the entity-wide, system, and application levels. GAGAS recommends using specific frameworks for internal control policies and procedures, including certain evaluation tools created specifically for federal government entities.29 Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular No. A123, Management's Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control, provides additional guidance.30

The federal government's internal control framework is based on the framework created by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO),31 which is widely used in the private sector.32 The COSO framework is dedicated to improving organizational performance and governance through effective internal control, enterprise risk management, and fraud deterrence.33

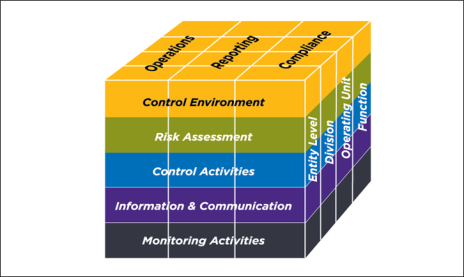

The COSO framework, depicted in Figure 1, was created to help practitioners assess internal controls not as an isolated issue, but rather as an integrated framework for how internal controls work together across an organization to help achieve objectives as determined by management. It represents the integrated perspective recommended by COSO for practitioners who are creating and assessing internal controls. The cube may be best understood by examining each set of components separately:

Categories of objectives. Operations, Reporting, and Compliance are represented by the columns. The objectives are designed to help an organization focus on different aspects of internal controls to help management achieve its objectives.

Components of internal control. Control Environment, Risk Assessment, Control Activities, Information and Communication, and Monitoring Activities are represented by the rows. The components represent what is required to achieve the three objectives.

Levels of organizational structure. Entity-Level, Division, Operating Unit, and Function are represented by the third dimension. For an organization to achieve its objectives, according to COSO, internal control must be effective and integrated across all organizational levels.34

|

|

Source: COSO, "Executive Summary," Internal Control - Integrated Framework, May 2013, p. 6, at https://www.coso.org/Pages/default.aspx. |

Internal Control at DOD

Internal controls can help DOD leadership achieve desired financial results through effective stewardship of public resources. Effective internal controls can increase the likelihood that DOD achieves its financial objectives, including getting a clean (i.e., unmodified) audit opinion. Properly designed internal controls can help reduce the amount of detail an auditor will examine, including the number of samples examined. Good internal controls could reduce the amount of time required to conduct an audit, thus reducing its cost.

At DOD, auditors identified 20 agency-wide internal control material weaknesses35and 129 DOD component-level material weaknesses that range from issues with financial management systems to inventory management.

A material weakness is a deficiency, or a combination of deficiencies, in internal control over financial reporting that results in a reasonable possibility that management will not prevent, or detect and correct, a material misstatement in the financial statements in a timely manner.36

Many of these material weaknesses are discussed later in this report under "Issues for Congress." Properly designed internal controls can also serve as the first line of defense in safeguarding assets.37 Internal controls help private and public entities achieve objectives, such as enterprise risk management, fraud deterrence, and sustained and improved performance, by designing processes that control risk.

The DOD IG identified multiple DOD components that do not have sufficient entity-level internal controls. The lack of entity-level internal controls directly contributed to an increased risk of material misstatements on the components' financial statements and the agency-wide financial statements.38

Until DOD resolves the many issues surrounding internal controls and establishes a better record-keeping system, it might be difficult for auditors to identify other material weaknesses that could prevent DOD from receiving a clean audit opinion. When the current set of internal control issues is resolved, and auditors are better able to analyze DOD records, they might discover additional issues, including new material weaknesses, that need to be resolved—a cascading effect—before DOD receives a clean audit opinion. This cycle might repeat a few times.

FY2018 Audit Results

The DOD auditors issued 2,377 notices of findings and recommendations (NFRs) that resulted in 20 agency-wide material weaknesses and 129 DOD component-level material weaknesses. Appendix A provides an overview of the 20 agency-wide material weaknesses.39 An auditor creates an NFR to capture issues that require corrective action. DOD then creates a corrective action plan (CAP) to address one or more NFRs. The NFR is later retested, and if the CAP sufficiently addresses the NFR, the auditor is to validate that the issue has been resolved.

As of June 2019, the majority of NFRs were related to three critical areas: approximately 48% were related to financial management systems and information technology; 30% were related to financial reporting and DOD's fund balance with Treasury; and 16% were related to property. Although the overall number of NFRs increased slightly between December 2018 and June 2019, the number has decreased significantly in certain categories (see Table 2, Other column). The increase in NFRs in certain categories is an expected result of the audit process. As auditors learn more about DOD and how it functions, they may continue to identify new NFRs, while DOD continues to address some of the previously identified NFRs.

|

Date |

Financial Management Systems & IT |

Financial Reporting & Fund Balance with Treasury |

Property |

Other |

Total FY2018 NFRs |

|

12/31/2018 |

1,085 |

521 |

385 |

367 |

2,358 |

|

06/20/2019 |

1,149 |

710 |

380 |

138 |

2,377 |

Source: Department of Defense Semiannual Corrective Action Plan Status Briefing, July 26, 2019.

The Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) has established an audit NFR database. DOD uses the database to consolidate and track the status of all auditor-issued NFRs and prioritize and link them to CAPs. The NFR and CAP component-based metrics are reported and reviewed monthly in the National Defense Strategy meeting with the Deputy Secretary of Defense and Military Service financial management leadership teams.40

The military service branches—Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force—account for over 60% of NFRs identified in the FY2018 audit (see Table 3).

Table 3. Number of FY2018 Notices of Findings and Recommendations (NFRs) by Functional Area and by Component

|

Component |

Financial Management Systems & IT |

Financial Reporting & Fund Balance with Treasury |

Property |

Other |

Total FY2018 NFRs |

|

Navy |

316 |

95 |

97 |

20 |

528 |

|

Marine Corps |

86 |

35 |

25 |

11 |

157 |

|

Army |

172 |

115 |

69 |

47 |

403 |

|

Air Force |

169 |

106 |

58 |

14 |

347 |

|

Other Reporting Entities and DOD Consolidated |

406 |

359 |

131 |

46 |

942 |

|

Total DOD |

1,149 (48%) |

710 (30%) |

380 (16%) |

138 (6%) |

2,377 |

Source: DOD, FIAR Report, June 2019, p. 3, at https://comptroller.defense.gov/ODCFO/FIARPlanStatusReport.aspx.

For DOD to receive a clean audit opinion, civilian leadership and uniformed Armed Forces personnel may need to improve collaboration. According to DOD, it is prioritizing CAPs that align with the National Defense Strategy and provide the greatest potential value to DOD operations and the warfighter. DOD has established actionable financial statement audit priorities at many levels within the department, including at the command level. Those FY2019 priorities include the following:41

- Real Property;

- Government Property in the Possession of Contractors;

- Inventory, and Operating Materials and supplies; and

- Access Controls for IT Systems.

Given the complexity of DOD operations, auditors began their work for the FY2019 financial audit in late 2018. Comprehensive data for the FY2019 audit are not currently available. However, the auditors issued an overall agency-wide disclaimer of opinion for FY2019.42 Most financial statement audits stop as soon as the auditor determines the reporting entity is not auditable. DOD, however, has asked the auditors to continue such audits to identify as many problems as possible, with the goals of identifying systemic issues and making faster progress toward business reform.43

Issues for Congress

Although the CFO Act required annual audits of federal agencies' financial statements, DOD did not complete an agency-wide audit until 2018—28 years later. One of DOD's strategic goals is to reform its business practices for greater performance and affordability.44 According to DOD, the annual audit process helps it reform its business practices consistent with the National Defense Strategy (NDS):45

The financial statement annual audit regimen is foundational to reforming the Department's business practices and consistent with the National Defense Strategy. Data from the audits is driving the Department's strategy, goals, and priorities and enabling leaders to focus on areas that yield the most value to the warfighter. The audits are already proving invaluable and have the potential to support long-term, sustainable reform that could lead to efficiencies, better buying power, and increased public confidence in DoD's stewardship of funds.46

Continued congressional oversight of DOD's plan to achieve a clean audit opinion could help DOD achieve a clean audit opinion. As more components receive a clean audit opinion, audit costs might eventually decrease.47 For FY2018, DOD incurred nearly $1 billion in total audit costs, which was less than 0.25% of DOD's FY2018 budget.48

Although the cost of an audit is a consideration, the more impactful benefits from an annual financial audit, arguably, are the changes in DOD business practices that directly impact the NDS while increasing transparency. The audits identified three critical areas of improvement that are consistent with the NDS: (1) financial management systems and information technology (IT), (2) financial reporting and fund balance with Treasury, and (3) property (real property, inventory, and supplies, and government property in the possession of contractors). Addressing the issues in these critical areas not only could help DOD improve its business practices, but it might also help resolve many of the NFRs, which could enable some audit components to receive clean audit opinions in the next few years instead of in another decade or more.

|

Congressional Interest in DOD Financial Audit Issues Listed below are a few recent examples of congressional interest in DOD financial audit readiness:

|

Financial Management Systems and Information Technology

According to DOD, its financial management systems and information technology provide a broad range of functionality to support agency financial management, supply chain management, logistics, and human resource management.54 Reliable systems are mission critical to DOD meeting its NDS and supporting the warfighter.

Also, DOD is required to comply with laws and regulations, such as the Federal Managers' Financial Integrity Act of 1982,55 the Federal Financial Management Improvement Act of 1996,56 and OMB Circular A-123.57 These laws and regulations collectively require DOD to maintain a system of internal controls that can produce reliable operational and financial information. The challenges DOD faces in financial management systems and information technology are twofold and compromise nearly half of all NFRs (see Table 2 or Table 3).58

First, DOD's initiatives to address the issues related to access controls for IT systems are partially implemented. A fully implemented plan to address access control issues would potentially restrict access rights to appropriate personnel, monitor user activity, and safeguard sensitive data from unauthorized access and misuse.59 As part of its corrective action plan, DOD is requiring financial system owners and owners of business systems that contribute financial information to review and limit access only to those who need it and only to the specific areas within the systems that they need to access.60

DOD has developed security controls and standardized test plans that align with the Federal Information Systems Control Audit Manual methodology used to test systems during an audit. Further, DOD management has directed components without a proper software maintenance policy to establish a baseline policy for those software systems and maintain a record of all software system changes.61 In addition to requiring components to develop reports on privileged users and transactions, including privileged user activities, the department has directed components to periodically review user access rights and remove unauthorized users.62

Second, the number and variety of financial systems complicate DOD's financial statement audits. In 2016, DOD reported more than 400 separate information technology systems were used to process accounting information to support DOD's financial statements.63 Many of these legacy systems were designed and implemented to support a particular function, such as human resource management, property management, or logistics management, and were not designed for financial statement reporting. These systems include newer ERP systems and custom-built legacy systems, financial systems, and nonfinancial feeder systems. Also, aging systems and technology that predate modern data standards and laws, as well as nonaccounting feeder systems, affect data exchange with modern ERPs to facilitate auditable financial reports.64

DOD's IT modernization program is investing in ERPs and aims to migrate 51 legacy systems to core modern ERPs by the end of 2023.65 How the remediation plans evolve and how they are implemented as DOD migrates to the new ERPs could be a significant determiner of DOD's ability to address nearly half of the NFRs.

Financial Reporting and Fund Balance with Treasury

According to DOD's auditors, its policies and procedures for compiling and reporting financial statements are not sufficient to identify, detect, and correct inaccurate and incomplete balances in the general ledger.66 Without an adequate process to identify and correct potential misstatements in the general ledger, balances reported on financial statements, accompanying footnotes, and related disclosures may not be reliable or useful for decisionmaking for Congress, including appropriating the DOD budget.67 The lack of accurate numbers, arguably, also presents challenges for DOD leadership in making agency financial decisions.

DOD's assets increased by nearly $200 billion in FY2018 over FY2017. Fund Balance with Treasury, one of the assets, increased by $78.6 billion. According to DOD, the increase in Fund Balance with Treasury resulted from additional appropriations received in FY2018.68 DOD is unable to effectively track and reconcile collection and disbursements activity from its financial systems, which resulted in DOD being unable to reconcile its general ledger and Treasury accounts.69

The fund balance with the Treasury Department is an asset account reported on DOD's general ledger, which shows a DOD component's available budget authority. Similar to a personal checking account, the fund's balance increases and decreases with collections and disbursements of new appropriations and other funding sources. Each DOD component should be able to perform a detailed monthly reconciliation that identifies all the differences between its records and Treasury's records.70 The reconciliations are essential to supporting the budget authority and outlays reported on the financial statements.71

The auditors identified several deficiencies in the design and operation of internal controls for fund balance with the Treasury that resulted in DOD-wide material weakness. DOD has undertaken business process improvements to streamline reporting, reduce differences to an insignificant amount, and support account reconciliations.72

Property and Inventory

The auditors report that DOD faces challenges with properly recording, valuing, and identifying the physical location of real property, inventory, and government property that is in the possession of contractors.73 DOD's challenges with property and inventory complicate Congress's ability to perform effective oversight and budget appropriations. Without accurate real estate counts and values, DOD will continue to face challenges in meeting the National Strategy for Efficient Use of Real Property.74

DOD faces similar issues with inventory. It is unable to provide assurance that inventory recorded in the financial statements exists and is valued properly.75 Without accurate inventory counts, DOD might not be able to support its missions without incurring additional costs. Some appropriated funds could be used to purchase extraneous inventory that DOD might already have on hand, or DOD might rely on inventory that appears in an inaccurate count but does not actually exist.

Real Property

The auditors report that DOD is unable to accurately account for all of its buildings and structures. This includes houses, warehouses, vehicle maintenance shops, aircraft hangars, and medical treatment facilities, among others. As an example, during the FY2018 audit, the Air Force identified 478 buildings and structures at 12 installations that were not in the real property system.76 DOD faces issues with demonstrating the right of occupancy or ownership through supporting documentation and with incomplete or out-of-date systems of record. Accurate property records, valuation, and right of ownership could potentially help inform DOD leadership as it considers any future base realignment and closure.77

According to DOD, military departments are executing real property physical inventories to reconcile with the systems of record. The Army has the largest real property portfolio in the department. All branches of the Armed Forces are facing challenges with obtaining source documents, establishing value for properties, and assessing and reporting expected maintenance costs.78

The Air Force is focused on correcting its records for buildings, which account for more than 90% of its real property value, first addressing its building inventory at its most significant bases.79 The Navy has completed its physical inventory and corrected its records. Initial results showed a 99.7% accuracy rate. The Marine Corps has undertaken a process of accurately counting and recording its physical inventory.80 The Armed Forces will be unable to obtain a clean audit opinion without determining the value of their real property and other assets.

Inventory, Materials, and Supplies

DOD manages inventory and other property at over 100,000 facilities located in more than 5,000 different locations.81 The military services and DOD components report inventory ownership on their financial statements, but this inventory can be in the custody of or managed by the military service or another DOD component. For example, as of FY2017 year end, the military services reported that the Defense Logistics Agency held approximately 46% of the Army's inventory, 39% of the Navy's inventory, and 45% of the Air Force's inventory, ranging from clothes to spare parts to engines.82

Given the vast geographic dispersion of DOD resources and the complexity of how they are managed, the system of records and physical inventory must agree with each other for DOD leadership to have an accurate understanding of available resources. GAO highlighted a few examples in its latest high-risk series:

- The Army found 39 Blackhawk helicopters that were not recorded in the property system;

- 107 Blackhawk rotor blades could not be used but were still in the inventory records;

- 20 fuel injector assemblies for Blackhawk helicopters did not have documentation to indicate ownership by any specific military service; and

- 24 gyro electronics for military aircraft that should not be used were still in the inventory records.83

Accurate inventory, materials, and supplies help DOD avoid purchasing materials it does not need and help ensure that the right parts, supplies, and other inventory are available to support mission readiness. Ensuring that parts, supplies, and inventory are usable not only helps with mission readiness but also helps avoid unnecessary warehousing costs. Many of the parts, supplies, and inventory are unique to DOD and require long lead times to contract and manufacture. An accurate physical count and system of records could help shorten the time before items are available for the warfighter.84

Government Property in the Possession of Contractors

At times, DOD might provide contractors with property for use on a contract, such as tooling, test equipment, items to be repaired, and spare parts held as inventory. The government-provided property and contractor-acquired property should be recorded in DOD's property system, and at the end of the contract, it might be disposed of, consumed, modified, or returned to DOD. The auditors report that the DOD property system should be able to accurately distinguish DOD property ownership and possession between DOD and the contractor.

For DOD to receive a clean audit opinion, it should consider requiring its contractors to maintain and provide auditors with accurate records. Transferring property from DOD to contractors, and from contractors to DOD, requires an accurate real-time system of record keeping.

Audit Costs

Total DOD audit-related costs for FY2018, including the cost of remediating audit findings, supporting the audits and responding to auditor requests, and achieving an auditable systems environment, were $973 million (see Table 4).85 DOD predicts that audit-related costs will remain relatively consistent for a few more years until more components begin to achieve unmodified opinions.86 In addition to the issues previously discussed, there are three agency-level issues or approaches that contribute to DOD audit costs remaining relatively constant in the near term: more substantive testing, completion of audit procedures even for those components that are likely to receive a disclaimer of opinion, and expansion of DOD service provider examinations.

While DOD's annual audit costs (i.e., excluding remediation costs) might remain close to FY2018 costs (nearly $413 million) or increase in the near term, the cost is expected to decrease after the first few years, as more components achieve a clean audit opinion. Eventually, DOD audit costs might increase as costs for travel and accounting increase with economic growth.

|

Overall DOD Costs |

Army |

Navy |

Marine Corps |

Air Force |

Other Reporting Entities |

|

|

Audit Services and Support |

413 |

77 |

72 |

13 |

71 |

180 |

|

Audit Remediation |

559 |

64 |

208 |

52 |

56 |

180 |

|

Total Costs |

973 |

141 |

280 |

66 |

127 |

360 |

Source: DOD, FIAR Report, June 2019, pp. 12-13, at https://comptroller.defense.gov/ODCFO/FIARPlanStatusReport.aspx.

Notes: Above figures may not sum due to rounding.

Substantive Testing

To reduce the risk of potential material misstatement without reliable internal controls, auditors seek other ways of validating financial information. Reliance on internal controls is not a pass-or-fail approach; rather, it is incremental. DOD received 20 agency-wide material weaknesses and 129 component-level material weaknesses in internal controls in the FY2018 audit; until those are resolved, DOD auditors must rely on substantive testing, which will keep audit costs relatively high. There are two categories of substantive testing:

- Analytical Procedures. Substantive testing through analytical procedures might include comparing current-year information with the prior year, examining trend lines, or reviewing various financial ratios. Because FY2018 was the first full financial audit of DOD and many systems of records are not reliable, auditors may have difficulty performing analytical procedures and must rely more on tests of details.87

- Tests of Details. An auditor selects individual items for testing and applies detail procedures, such as verifying that invoiced items from a vendor match payments made by DOD, physically locating an inventory item that is recorded in DOD's financial systems, and verifying mathematical accuracy by recalculating certain records.88

Completion of Audit Procedures

To gain a detailed understanding of the underlying issues that prevent DOD components from receiving clean audit opinions, the department has requested comprehensive completion of audit procedures even after auditors have determined components will receive disclaimers of opinion.89 While this approach might initially incur higher audit costs, in the long run it might enable DOD to resolve the component-specific issues more quickly and to gain a holistic perspective of system-wide issues. These benefits might help DOD lower its financial audit costs in the long run.

Service Provider Examinations

Some DOD organizations provide common information technology services to other organizations within DOD, such as the Defense Information Systems Agency's (DISA's) Automated Time Attendance and Production System. For FY2018, auditors completed 20 DOD service provider examinations; 14 resulted in unmodified opinions and 6 resulted in qualified opinions. See Table B-1 for more information, including auditors' opinions and the number of FY2018 NFRs issued. Service provider examinations assess whether information technology control activities were designed, implemented, and operated effectively to provide management reasonable assurance that control objectives function as designed or intended in all material respects.90 The procedures performed by the auditors for examinations are not meant to provide the same level of assurance as a full audit.91

These examinations' results can be used to reduce redundant testing of control by component-level auditors, saving time and money; see Table 1 for the list of audited DOD components.92 For FY2019, DOD expects to complete 23 common service provider examinations, compared to 20 in FY2018.93 The expanded service provider examinations for FY2019 might incrementally increase DOD audit costs over FY2018.

Financial Audit Limitations and Benefits

Since passing the CFO Act of 1990, Congress has continued to express interest in DOD completing an annual financial audit. Financial audits can help DOD increase transparency and accountability, improve business processes, and improve the visibility of assets and financial resources, but by design, audits are meant to accomplish a specific purpose, and therefore there are some inherent limitations on the benefits they can provide. Financial audits' limitations and benefits are discussed below.

Limitations of Financial Audits

A financial audit is a tool to help improve business processes and readiness on an annual basis. It does not address program effectiveness or efficiency, but it does consider whether an entity's assets, including its budget authority, are used to accomplish its programmatic purpose. To communicate the annual audit's benefits to Congress and other stakeholders, DOD may attempt to measure cost savings or business process improvements, but it may struggle to fully quantify the benefits, as many of the daily operational improvements are likely to be organic and informal.

Only the most significant issues will be identified in auditors' reports. DOD will likely benefit from auditors' NFRs, as well as ongoing informal dialogue between auditors and DOD personnel. When an auditor identifies an issue, DOD could seek to address the issue immediately rather than wait for a written report. It is inefficient for auditors or DOD to capture and write a report on all issues, large and small. In the private sector, generally, only critical audit matters that involve especially challenging or complex auditor judgments are included in audit reports. Many other issues are addressed in the normal course of business.94 Reporting or recording every instance of savings or process improvement based on auditors' informal feedback arguably detracts from the audit's purpose. Allowing a degree of flexibility to identify and report the cost savings and process improvements that DOD determines are the most significant may help the department focus effectively on responding to audit findings.

Independent audit opinions do not fully guarantee that financial statements are presented fairly in all material respects, but provide reasonable assurance for the following reasons:

- Auditors use statistical methods for random sampling and look at only a fraction of economic events or documents during an audit. It is cost- and time-prohibitive to recreate all economic events.

- Some line items on financial statements involve subjective decisions or a degree of uncertainty as a result of using estimates.

- Audit procedures cannot eliminate potential fraud, though an auditor may identify fraud.

- Financial audits are not specifically designed to detect fraud, but an auditor assesses the potential for fraud, including evaluating internal controls designed by management to prevent and identify potential fraud, waste, and abuse. Auditors are required to consider whether financial statements could be misstated as a result of fraud.95

- Effective internal controls could prevent or mitigate risks for fraudulent financial reporting, misappropriation of assets, bribery, and other illegal acts. Fraud risk factors do not necessarily indicate fraud exists, but risk factors often exist when fraud occurs.96

- In a few years, if DOD has improved its current business practices, future improvements might be less significant and more incremental. Even so, annual audits could potentially be a valuable tool to help DOD continue to improve its business processes.

Benefits of an Annual Financial Audit

The annual audit gives Congress an independent opinion on DOD's financial systems and business processes. It provides a way for DOD to continue to improve its performance and highlights areas that need to be fixed. DOD has identified four categories of how the annual audit improves its operations, along with some examples:97

- Increases Transparency and Accountability. Holds DOD accountable to Congress and the taxpayers that DOD takes spending taxpayer dollars seriously through efficient practices. Auditing DOD helps improve public confidence in DOD operations, similar to other Cabinet-level agencies that conduct an annual financial audit.

- Streamlines Business Processes. Audits help reduce component silos and help leadership better understand interdependencies within DOD. The department might be able to improve its buying power and reduce costs, as well as improve operational efficiencies.

- Improves Visibility of Assets and Financial Resources. More accurate data could enhance DOD readiness and decisionmaking. Getting the appropriate supplies to warfighters helps improve their fighting posture. If a service does not know whether it has enough spare parts to ensure that aircraft are able to fly, it may spend significant amounts of money to get spare parts quickly to meet operational requirements.

Accurate cost information related to assets, such as inventory and property, can help DOD make more informed decisions on repair costs and future purchases. - Strengthens Internal Controls. Strengthened internal controls help minimize fraud, waste, and abuse. In addition, they help improve DOD's cybersecurity and enhance national security.98

In addition to the previously described identification of Blackhawk helicopters and parts, DOD is starting to see gains by eliminating recurring annual costs. For example, strengthening internal controls to improve operations at the U.S. Pacific Fleet has freed up purchasing power to fund $4.4 million in additional ship repair costs.99 Also, the Army has implemented a materiality-based physical inventory best practice to count assets at Army depots. The Army estimates this process improvement could help avoid approximately $10 million in future costs.100

Conclusion

Since passing the CFO Act of 1990, which required 24 agencies101 to conduct an agency-wide annual financial audit, Congress has continued to express interest in DOD completing an annual audit. DOD completed its first agency-wide audit in FY2018 and a subsequent audit in FY2019. Both audits resulted in a disclaimer of opinion.

The ongoing independent assessment of DOD's financial systems, arguably, provides Congress and DOD leadership with an independent third-party assessment of DOD's financial and business operations. Reliable systems that produce auditable financial information, including an accurate count and valuation of real estate and inventory, could help Congress provide better oversight and ultimately determine how funds appropriated for DOD should be spent in support of the NDS.

Further, the annual financial audit of DOD by independent auditors might provide DOD with a competitive advantage when compared to other countries' defense agencies. In many other countries, financial information—including a financial audit of defense agencies—is nonexistent or opaque at best and not readily available to legislators or citizens.102

Many of DOD's financial management systems are also used for operational purposes. Testing of the financial management systems and other systems that interface with each other as part of the annual audit process can help identify and improve cybersecurity vulnerabilities and the conduct of military operations.103 DOD's efforts to fix its vulnerabilities and reduce wasteful practices, arguably, could enable it to respond to future threats more effectively.104

The implementation of new ERP systems and the complexity of auditing DOD might result in DOD not achieving a clean audit opinion within the next decade. Without each of the Armed Forces receiving a clean audit opinion, DOD will not be able to receive an agency-wide clean audit opinion even if all other DOD components receive a clean audit opinion.

Appendix A. DOD Agency-Wide Material Weaknesses

Weaknesses and inefficiencies in internal controls are classified based on severity. Auditors identified 20 material weaknesses at DOD (see Table A-1) related to internal controls that range from issues with financial management systems to inventory management.

A material weakness is a deficiency, or a combination of deficiencies, in internal control over financial reporting that results in a reasonable possibility that management will not prevent, or detect and correct, a material misstatement in the financial statements in a timely manner.105

In addition to material weaknesses, the auditors issue two types of deficiencies—a significant deficiency or a control deficiency—that are less severe than a material weakness, but a combination or multiple instances of either deficiency can result in material weaknesses.106

A significant deficiency is a deficiency or a combination of deficiencies that are less severe than a material weakness, but important enough to merit management's attention. A control deficiency is a noted weakness or deficiency that auditors typically bring to management's attention, but that does not have an impact on the financial statement unless a combination of them results in a material weakness.107 Improvements in either type of deficiency could improve the business process and help prevent waste, abuse, and fraud.

|

Material Weakness |

Description |

|

Financial Management Systems and Information Technology |

DOD was unable to collect and report financial and performance information that is accurate, reliable, and timely. |

|

Universe of Transactions |

DOD was unable to produce a complete, accurate, and reconcilable universe of transactions. The universe of transactions is compiled by combining all transactions from multiple accounting systems—a central repository of financial transactions. As an example, when DOD purchases an inventory item, it should be able to trace the information successfully from when the contract is issued and the item is received, maintain an accurate inventory record, record when the payment is made, and remove the item from the inventory system when it is disposed. |

|

Financial Statement Compilation |

DOD lacked processes and internal controls to ensure complete and accurate component financial statements could be prepared prior to the agency-wide annual financial report. |

|

Fund Balance with Treasury |

DOD was unable to reconcile its fund balance with Treasury, as it had ineffective processes and controls. |

|

Accounts Receivable |

DOD was unable to record and report accounts receivable transactions, as it had ineffective processes and controls. |

|

Operating Material and Supplies |

DOD was unable to issue a financial statement on operating materials and supplies in accordance with GAAP. |

|

Inventory and Related Property |

DOD did not have systems and controls necessary to assure the existence of certain inventory, value some of the inventory on record, or have records that accurately reflected what it had in its warehouses. |

|

General Property, Plant, and Equipment |

DOD was unable to report the value of property, plant, and equipment at acquisition or historical cost, establish or support ownership of the asset, or determine a value for the asset. |

|

Government Property in Possession of Contractors |

DOD lacked policies, procedures, controls, and supporting documentation over the acquisition, disposal, and tracking of government property in the possession of contractors. |

|

Accounts Payable |

DOD did not have financial management systems that were capable of properly recording accounts payable transactions. |

|

Environmental and Disposals Liabilities |

DOD was unable to develop accurate estimates and accurately account for environmental liabilities in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). |

|

Legal Contingencies |

DOD was unable to provide the auditors with supporting documentation to determine if DOD reported legal contingencies accurately in the notes to the financial statements. |

|

Beginning Balances |

DOD did not have historical data to support beginning balances. |

|

Journal Vouchers |

DOD recorded more than 1,200 journal vouchers for $175 billion that were not fully supported, affecting the financial statements. A journal voucher should have critical information such as transaction date, description, amount, affected accounts, and authorizing signatures before a journal entry is entered into a system. A journal entry is a record of the transaction in the financial management system. |

|

Intragovernmental Eliminations |

DOD could not accurately identify, provide supporting documentation, or fully reconcile its intragovernmental transactions. |

|

Statement of Net Costs |

DOD did not accumulate cost information or record transactions in agreement with GAAP. |

|

Reconciliation of Net Cost of Operations to Budget |

DOD was unable to reconcile its budgetary and proprietary data. |

|

Budgetary Resources |

DOD was unable to accurately determine its total budgetary resources available or the status of those resources. |

|

Entity-Level Controls |

DOD did not have sufficient entity-level controls (at the agency level) to establish an internal control system that would produce reliable financial reporting. |

|

Oversight and Monitoring |

DOD management did not provide effective oversight and monitoring to ensure that DOD components developed and implemented corrective action plans for all material weaknesses. |

Source: CRS; DOD IG, Understanding the Results of the Audit of the DOD FY2018 Financial Statements, January 8, 2019, pp. 20-21, at https://www.dodig.mil/reports.html/Article/1725880/understanding-the-results-of-the-audit-of-the-dod-fy-2018-financial-statements/.

Appendix B. Common Service Providers

Some organizations within DOD provide common information technology services to other organizations at DOD. These organizations report to higher-level organizations. For FY2018, auditors completed 20 DOD service provider examinations—14 resulted in unmodified opinions and 6 resulted in qualified opinions. See Table B-1 for more information, including auditors' opinions and the number of FY2018 NFRs issued. Service provider examinations provide a positive assurance as to whether information technology control activities were designed, implemented, and operate effectively to provide management reasonable assurance that control objectives function as designed or intended in all material respects.108 Examination procedures are limited in scope as compared to a financial audit.109 Component-level auditors can use these examinations' results to reduce redundant testing, saving time and money; see Table 1 for the list of audited DOD components.110 For FY2019, DOD expects to complete 23 common service provider examinations.111

|

Entity |

Examination Opinion |

# of NFRs Issued |

|

Army |

||

|

General Fund Enterprise Business Systems (GFEBS) |

Qualified |

10 |

|

Conventional Ammunition |

Qualified |

43 |

|

Defense Contract Management Agency |

||

|

Contract Pay |

Unmodified |

7 |

|

Defense Finance Accounting Service |

||

|

Civilian Pay |

Unmodified |

2 |

|

Military Pay |

Unmodified |

4 |

|

Vendor Pay |

Qualified |

12 |

|

Standard Disbursing Services |

Unmodified |

1 |

|

Contract Pay |

Unmodified |

2 |

|

Financial Reporting |

Qualified |

9 |

|

Defense Cash Accountability System/Fund Balance with Treasury (DCAS/FBWT) |

Qualified |

5 |

|

Enterprise Local Area Network (ELAN) |

Qualified |

3 |

|

Defense Information Systems Agency |

||

|

Enterprise Computing Services (ECS) |

Unmodified |

18 |

|

Automated Time Attendance and Production System (ATAAPS) |

Unmodified |

5 |

|

Defense Logistics Agency |

||

|

Invoicing, Receipt, Acceptance, and Property Transfer/Wide Area Work Flow (iRAPT/WAWF) |

Unmodified |

1 |

|

Defense Automatic Addressing System (DAAS) |

Unmodified |

0 |

|

Serviced Owned Items in the Custody of Defense Logistics Agency (SOIDC) |

Unmodified |

3 |

|

Defense Agencies Initiative (DAI) |

Unmodified |

0 |

|

Defense Property Accountability System (DPAS) |

Unmodified |

0 |

|

Defense Manpower Data Center |

||

|

Defense Civilian Personnel Data System (DCPDS) |

Unmodified |

2 |

|

Defense Travel System (DTS) |

Unmodified |

5 |

|

TOTAL |

132 |

|

Source: CRS; DOD, FIAR Report, June 2019, p. 5, at https://comptroller.defense.gov/ODCFO/FIARPlanStatusReport.aspx.