Introduction

The federal government supports the charitable sector by providing charitable organizations and donors with favorable tax treatment. A primary source of support is allowing a tax deduction for charitable contributions made by individuals who itemize deductions, by estates, and by corporations. For charitable organizations, earnings on funds held by such organizations are exempt from the federal income tax.

The tax revision enacted in late 2017, popularly known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (P.L. 115-97), made some temporary changes that, while not specifically aimed at charitable deductions, reduced the scope of the tax benefit for charitable giving. These changes have caused more individuals to take the standard deduction, rather than itemizing deductions, and exempted more estates from the estate tax, eliminating the benefit of deducting charitable contributions in these cases. These changes are expected to lead to a reduction in charitable giving. There were other more minor changes, some enhancing the charitable deduction and some imposing more taxes on charitable organizations.

The report begins with a description of the charitable sector and tax provisions affecting the sector. The following sections discuss the magnitude of charitable deductions, including sources and beneficiaries, with historical data. The report then discusses the incentive effects of the deductions and the consequences for charitable giving, including potential effects of the 2017 tax revision. The report concludes with a discussion of policy options.

The Charitable Sector

Definitions and Overview

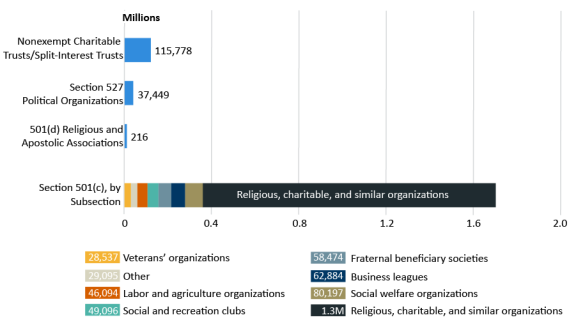

The focus of this report is the charitable sector. Charities are one type of tax-exempt organization. Specifically, they are organizations with 501(c)(3) public charity status.1 As illustrated in Figure 1, most 501(c) organizations are 501(c)(3) "religious, charitable, and similar organizations." Charitable organizations fall within the broader nonprofit sector. In public policy discussions, the term nonprofit sector is often intended to include all organizations with federal tax-exempt status.2

The Internal Revenue Code (IRC) describes approximately 30 types of tax-exempt organizations. Other types of tax-exempt organizations, in addition to charities, include social welfare organizations, labor unions, trade associations, chambers of commerce, fraternal societies, and political organizations. Within the nonprofit tax-exempt sector, the bulk of organizations are exempt from tax under IRC Section 501(c)(3) (they are "religious, charitable, or similar organizations"). Most of the tax-exempt sector's financial activity also takes place in 501(c)(3) organizations.

|

|

Source: Internal Revenue Service, IRS Data Book Table 25, at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-tax-exempt-organizations-and-nonexempt-charitable-trusts-irs-data-book-table-25. Notes: Religious, charitable, and similar organizations are exempt from federal income tax under IRC §501(c)(3). The "Religious, charitable, and similar organizations" category includes private foundations. Social welfare organizations are exempt under IRC §501(c)(4). Labor and agriculture organizations are exempt under §501(c)(5). Business leagues are exempt under §501(c)(6). Social and recreation clubs are exempt under §501(c)(7). Fraternal beneficiary societies are exempt under §501(c)(8). Veterans' organizations are exempt under §501(c)(19). |

Every 501(c)(3) organization is classified as either a "public charity" or "private foundation." Public charities have broad public support and tend to provide charitable services directly to the intended beneficiaries. Private foundations often are tightly controlled, receive significant portions of their funds from a small number of donors or a single source, and make grants to other organizations rather than directly carry out charitable activities. 501(c)(3) organizations are presumed to be private foundations unless they qualify for public charity status based on support and control tests.

IRS Filing Requirements for 501(c)(3) Charities and Foundations

In 2015, there were 1,088,447 registered 501(c)(3) public charities.3 Of this total, 314,744 were reporting public charities, and filed a Form 990.4 Form 990 collects information about the organization's finances, assets, and activities. Organizations with gross receipts of $50,000 or more are generally required to file a Form 990 or Form 990-EZ. Private foundations file a Form 990-PF. Smaller organizations are not required to file an annual return, but may be required to file an annual electronic notice, the "e-postcard."5 Churches and other qualifying religious organizations are exempt from the annual information-reporting requirements.6 The informational returns (i.e., Form 990s) of exempt organizations are public, unlike individual and corporate income tax returns.7

In addition to the information return, there are situations when tax-exempt organizations must file an income tax return. For example, tax-exempt organizations are subject to tax on income from business activities unrelated to their exempt purpose.8 Organizations subject to this tax, known as the unrelated business income tax (UBIT), must file a tax return using the Form 990-T. Two recent changes to UBIT became effective in 2018 (see the shaded box "UBIT Changes for 2018" below). Additionally, tax-exempt organizations must generally pay the same employment taxes (i.e., withhold income and payroll taxes of their employees) as for-profit employers. Finally, an organization's activities might require it to file other returns, such as an excise tax return.

|

UBIT Changes Effective for 2018 The 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97), commonly called the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), made two permanent changes to UBIT. Both changes were effective for the 2018 tax year.

|

Current Tax Treatment

Federal statute includes multiple tax preferences for nonprofit and charitable organizations. Donations to charitable organizations may be tax deductible, which subsidizes charitable giving. Additionally, nonprofit and charitable organizations are generally exempt from tax on most income, including investment income.

Some of the tax benefits are considered "tax expenditures" by the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), meaning the JCT provides an estimate of the amount of forgone revenue associated with the provision.9 Other tax benefits confer financial benefits to the sector, although the value of those benefits is not regularly estimated by the JCT.

In addition to the federal tax benefits discussed here, there may also be state and local tax benefits associated with nonprofit or charitable status. For example, in addition to income tax benefits that mirror federal income tax benefits, state and local governments may provide property or sales tax exemptions.

The Tax Deduction for Charitable Contributions

The primary tax expenditure for charities is the charitable deduction.10 Individual taxpayers who itemize their deductions can—subject to certain limitations—deduct charitable donations to qualifying organizations.11 The JCT estimated that in 2019, approximately 13% of taxpayers will itemize deductions.12 Corporations may also be able to deduct charitable contributions.

Organizations qualified to receive tax-deductible charitable contributions include public charities and private foundations; federal, state, or local governments; and other less common types of qualifying organizations.13 Contributions to civic leagues, labor unions, most foreign organizations, lobbying organizations, political contributions, and contributions directly made to individuals are not deductible as charitable contributions.

There are limits on the deduction for charitable contributions for both individuals and corporations. For individuals, the deduction for gifts of cash or short-term capital gain property given to a public charity; private operating foundation; or federal, state, or local government is 60% of the taxpayer's adjusted gross income (AGI) (these limitations are summarized in Table 1).14 Gifts of cash or short-term capital gain property to private nonoperating foundations or certain other qualifying organizations are generally limited to 30% of AGI.

|

Type of Donation |

Recipient |

Valuation Rules for Property |

Limitation |

|

Cash or short-term capital gain property |

Public charity; private operating foundation; federal, state, local government |

Basis of the property |

60% of AGIa |

|

Private nonoperating foundation; otherb |

Basis of the property |

30% of AGI |

|

|

Long-term capital gain property |

Public charity; private operating foundation; federal, state, local government |

Fair market value |

30% of AGI |

|

Private nonoperating foundation; otherb |

Basis of the property |

20% of AGI |

Source: Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §170.

Note: These are general rules, and there are exceptions.

a. Temporarily increased from 50% to 60% through 2025.

b. Includes qualifying contributions to veterans organizations, fraternal societies, and nonprofit cemeteries. Not all nonoperating foundations are subject to the 30% limit.

The contribution of appreciated assets has particularly beneficial treatment, as the value of most appreciated assets can be deducted without including the capital gains in income that would be subject to tax. Thus, gifts of appreciated property are generally subject to lower deduction limits. Donations of long-term capital gain property to public charities; private operating foundations; or federal, state, or local government are limited to 30% of AGI, while contributions to private nonoperating foundations or certain other qualifying organizations are generally limited to 20% of AGI. Individuals are allowed to carry forward charitable contributions that exceed the percentage limits for up to five years.

Corporate charitable contributions are generally limited to 10% of a corporation's taxable income. For a corporation, transfer of property to a charity might qualify as a deductible charitable contribution or a deductible business expense, but cannot be both. Like individuals, corporations are allowed to carry forward charitable contributions that exceed the percentage limits for up to five years.

Valuation Rules for Charitable Contributions

There are several rules related to the valuation of charitable contributions (also summarized in Table 1). For cash contributions, the value is simply the amount donated. However, when property is donated, the charitable deduction may be limited to the fair market value of the property, the taxpayer's tax basis in the property, or some other amount. Generally, as noted above, taxpayers can deduct the full fair market value of long-term capital gain property. Taxpayers may also be able to deduct the full fair market value of tangible personal property donated to a charity whose use of the property is related to their tax-exempt purpose.

In some cases, the amount that can be deducted is limited to the donor's tax basis in the property. Specifically, deductions for contributions of property may be limited to basis for contributions of inventory or short-term capital gain property, contributions of tangible personal property that are used by a recipient organization for a purpose unrelated to the recipient's exempt purpose, or contributions to private foundations (other than certain private operating foundations).15 Donations of appreciated stock to private nonoperating foundations are not subject to this limit, and may be deducted using fair market value. Contributions of patents or other intellectual property may also be limited to the donor's basis in the property. Deductions are generally limited to the fair market value of the donated property, if the fair market value is less than the tax basis.

Special Rules for Certain Types of Contributions

There are a number of special rules related to donations of certain types of property, not all of which are discussed here. Special rules provide an enhanced deduction for C corporations contributing inventory to 501(c)(3) organizations for the care of the ill, the needy, or infants. There is also an enhanced deduction for businesses' contributions of food inventory.16 There are special rules associated with donations of vehicles,17 intellectual property,18 and clothing and household items.19 Another special provision allows for tax-free distributions from individual retirement accounts (IRAs) for charitable purposes.20 The IRA distribution provision is especially beneficial to nonitemizers because it excludes the distribution from income, which is equivalent to receiving the distribution and making a charitable deduction.

Generally, a charitable deduction can be claimed only if the donor transfers their full interest in the property to a qualified recipient organization. This partial interest rule generally prohibits charitable deductions for contributions of income interests, remainder interest, or rights to use property. There is an exception to the partial interest rule for conservation contributions. Conservation contributions allow for charitable donations of conservation easements, where land, natural habitats, open space, or historically important sites are protected from development without the owner having to give up ownership of the property. Additionally, special rules increase the limit for appreciated property contributed for conservation purposes to 50% of AGI for individuals.21 For farmers and ranchers, including individuals and corporations that are not publicly traded, the limit is increased to 100% of income. Conservation contributions that exceed the 50% or 100% of income giving limits can be carried forward for 15 years, instead of the usual 5 years.

Individuals can take a deduction for donations of property in the future with rights to the income stream for themselves or others, through a charitable remainder trust. In a charitable remainder trust, assets are transferred to a trust and a deduction taken for the present value of the future donation. The donor or other designated individual can receive a stream of income from the trust, for example, until death. Appreciated assets can be donated to the trust, which is tax exempt and pays no tax on the gain from the sale of assets.

Recent Changes to Charitable Giving Tax Incentives

Due to the 2017 tax revision (TCJA), the tax expenditure associated with the charitable deduction has fallen. Under TCJA, however, there were limited direct changes in tax policies affecting charities. The one change to the charitable deduction expanded the deduction, raising the AGI limit for individual cash contributions to public charities from 50% to 60% through 2025. However, other changes that reduced the number of itemizers, such as the expanded standard deduction and the limit on state and local tax deductions, reduced the number of itemizers and reduced the marginal incentive to give to charity for many taxpayers.22

At times, Congress had passed legislation eliminating the percentage of AGI limit for charitable contributions made for disaster relief purposes. Recently, the Disaster Tax Relief and Airport and Airway Extension Act of 2017 (P.L. 115-63) eliminated the limit for charitable contributions of cash for Hurricane Harvey, Irma, or Maria disaster relief. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123) eliminated the limit for charitable contributions of cash associated with the 2017 California wildfires.23

Charitable Tax Expenditures

JCT's tax expenditure budget includes several charitable tax expenditures: the deduction for charitable giving, tax expenditures for certain tax-exempt bonds, and the exclusion for ministers housing allowance. The JCT provides charitable deduction tax expenditure estimates separately for contributions to 501(c)(3) educational institutions and health organizations. In FY2019, the tax expenditure for charitable deductions associated with giving to organizations other than education institutions or health organizations was $32.6 billion, while the tax expenditures for giving to educational institutions and health organizations were $8.2 billion and $4.3 billion, respectively (see Table 2).

|

Provision |

Individual |

Corporate |

Total |

|

|

Deduction for Charitable Contributions (total) |

40.9 |

4.2 |

45.1 |

|

|

Educational Institutions |

7.2 |

1.0 |

8.2 |

|

|

Health Organizations |

3.2 |

1.1 |

4.3 |

|

|

Other than Education and Health |

30.5 |

2.1 |

32.6 |

|

|

Tax-Exempt Bonds (total for educational facilities and hospitals) |

4.7 |

1.3 |

6.0 |

|

|

Private Nonprofit and Qualified Public Educational Facilities |

2.8 |

0.8 |

3.6 |

|

|

Private Nonprofit Hospitals |

1.9 |

0.5 |

2.4 |

|

|

Ministers Housing Allowance Exclusion |

0.7 |

— |

0.7 |

|

Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures, FY2018-FY2022, JCX-81-18, October 4, 2018.

|

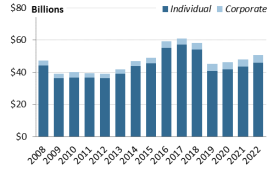

Figure 2. Charitable Deduction Tax Expenditures, FY2008–FY2022 |

|

|

Source: Joint Committee on Taxation. Notes: All tax expenditure estimates are projections. |

Tax expenditures for the charitable deduction have recently declined. For FY2019, it is estimated that the charitable deduction will be associated with $45.1 billion in forgone revenue (see Figure 2).24 This is down from the estimated $61.0 billion in forgone revenue for FY2017, and $58.1 billion for FY2018.25 The decline in the charitable deduction tax expenditure is the result of (1) fewer taxpayers itemizing deductions following the 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97); and (2) lower tax rates following the 2017 tax revision.

Most of the forgone revenue associated with the charitable deduction is from individual giving, as opposed to corporate giving. The charitable deduction does not reflect forgone revenue associated with giving from bequests (which is discussed further below).

There are also revenue effects associated with allowing nonprofit educational institutions and hospitals to issue tax-exempt bonds, and for the provision exempting the housing allowance of ministers from tax. Tax expenditures for charities in FY2019 are reported in Table 2.

The Tax Treatment of Investment Income

For charities, most investment income is exempt from tax (there is a tax on the investment income of certain endowments, which is discussed below). The JCT does not consider the exemption of charities' investment income from tax a tax expenditure, and thus does not provide an estimate of the forgone revenue associated with this tax treatment.

Data from IRS Form 990 informational returns can be used to understand the magnitude of 501(c)(3)s' exemption for investment income. In 2015, charities had $32.6 billion in investment income, $35.8 billion in net capital gains (mostly from the sale of securities), $4.0 billion in net rental income, and $3.9 billion in royalties.26 If this income had been subject to a 35% income tax (the corporate income tax rate in 2015), $26.7 billion in revenue would have been raised.27 This number does not include religious organizations.28

IRS data for 2015 reported assets of $3.8 trillion held by charities, with about $1 trillion of that amount in land, buildings, and equipment.29 Private foundations had $0.8 trillion in assets, with $0.7 trillion in investment assets.30 A significant share of investment assets held in charities is held in university endowments, with an estimated value of $0.6 trillion in FY2018.31 Assets do not include assets of nonreporting religious organizations.

Private Foundations

Most private foundations differ from operating charities in that they often have a single donor or small group of donors. In addition, while a gift to a foundation is deductible for income (and estate and gift) tax purposes, the donated funds are not immediately used for active charitable purposes. Rather, funds are invested and donations are often made to charitable organizations from earnings that may allow the corpus of the foundation to be maintained and grow. Contributions to foundations benefit from both the charitable deduction, when the contribution is made, as well as the exemption on investment earnings, as earnings accrue on invested contributions over time.

To address concerns that foundations could retain earnings and grow indefinitely, and because foundations are often closely tied to a family or specific group of donors, tax laws require a minimum payout rate (5% of assets) and restrict activities that may benefit donors. The tax code imposes taxes and/or penalties for self-dealing, for failure to distribute income on excess business holdings, for investments that jeopardize the charitable purposes, and for taxable expenditures (such as lobbying or making open-ended grants to institutions other than charities).

Private foundations are subject to a 2% excise tax on their net investment income.32 However, the rate is reduced to 1% if qualifying charitable distributions are increased.33 In FY2017, excise taxes on private foundations generated $643.6 million in revenue.34

Donor-Advised Funds (DAFs) and Supporting Organizations

Donor-advised funds (DAFs) allow individuals to make a gift to a fund in a sponsoring organization. Sponsoring organizations are charities that are allowed to receive tax-deductible donations. The gift is irrevocable, as in the case of a gift to a foundation or any other charity. The donor does not legally oversee the payment of grants to charities from the fund, which is determined by the sponsoring organizations. Donors make recommendations for grants (hence donor advised), and there is general agreement that these recommendations determine, with few exceptions, the contributions.35 DAFs, like private foundations, can accumulate assets and earn a return tax free, but they are not subject to many of the restrictions on foundations, including the minimum payout rate.

These funds have been growing rapidly, in part through funds set up by major financial institutions.36 According to the National Philanthropic Trust, in 2017 there were 463,622 individual DAFs, with contributions of $29.2 billion, assets of $110.0 billion, and recommended grants of $19.1 billion. The DAFs were managed by 53 national charities, 604 community foundations, and 345 single-issue charities.37 In 2018, more than 200,000 donors had accounts at Fidelity Charity, with grants of over $5.2 billion.38

Supporting organizations are organized for the benefit of public charities, and they provide grants to these charities. There are several types of supporting organizations (DAFs are themselves supporting organizations). Type I and Type II organizations support a single charity and are supervised or controlled by the supported charity (with Type I similar to a parent-subsidiary relationship and Type II similar to a brother-sister relationship). A Type III organization supports more than one charity and falls into the category of a functionally integrated supporting organization, or FISO (either through performing certain activities directly or exercising governance and direction) and nonfunctionally integrated (non-FISO). A Type III non-FISO has a number of additional restrictions, including a requirement to distribute the greater of 85% of net income or 3.5% of nonexempt-use assets.39

College and University Endowments

A college or university endowment fund—often referred to simply as an endowment—is an investment fund maintained for the benefit of the educational institution. University endowments have been the subject of some scrutiny, in part because of the juxtaposition of growing endowment sizes with increasing tuition at private universities.40 The 2017 tax revision, P.L. 115-97, added a 1.4% excise tax on net investment income of nonprofit colleges and universities with assets of at least $500,000 per full-time student and more than 500 full-time students. The revenue gain was projected to be $0.2 billion per year.41

Tax-Exempt Hospitals

For private nonprofit hospitals to be eligible for tax-exempt status, to be able to receive tax-deductible charitable contributions, and to be eligible for tax-exempt bond financing, they must meet a community benefit standard. Health care is not by itself a stated objective in the tax provisions determining charitable (501(c)(3)) status. Generally, the community benefit standard requires the hospital to show that it has provided benefits that promote the health of a broad class of persons in the community. One way hospitals may demonstrate that they have met the community benefit standard is by providing charity care (free or discounted services to charity patients). Other types of community benefit include participation in means-tested programs such as Medicaid; providing health professions education, conducting health services research, providing subsidized health services, funding community health improvement, and donating cash or in-kind contributions to other health-related community groups.42 Community-building activities (such as for housing and the environment) may qualify if a link to community health can be shown. The IRS does not count shortfalls associated with Medicare or bad debts from those not qualifying for charity care as part of the community benefit standard.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA; P.L. 111-148) added additional requirements for 501(c)(3) tax-exempt hospitals. Specifically, 501(r) requires these hospitals to conduct community health needs assessments, establishing a written financial assistance policy, limit charges to financial-assistance-eligible patients to amounts billed to insured patients, and not engage in extraordinary billing collections until an effort is made to determine eligibility for financial assistance. Tax-exempt hospitals report their community benefit actions on their Form 990.43 In 2014, total net community benefit expenses were $63.0 billion (8.84% of expenses); of that amount, $12.7 billion was for charity care (1.78% of expenses) and $26.3 billion for unreimbursed means-tested costs (3.7%, almost entirely Medicaid).44 One study estimated the cost of all federal, state, and local subsidies for tax-exempt hospitals (income, sales, and property tax benefits) to be $24.6 billion in 2011.45 Another study using 2012 data found that nonprofit hospitals' community benefit expenses were 7.63% of total expenses, while the value of nonprofit hospitals' tax exemption was 5.87% of total expenses.46 The study also evaluated incremental community benefits, or community benefits beyond those provided by for-profit hospitals. Incremental community benefits provided by nonprofit hospitals were estimated to be 5.71% of expenses in 2012.

Tax Treatment of Charitable Bequests

Charitable donations made by an estate are generally referred to as charitable bequests. Decedents potentially subject to the estate tax can deduct charitable contributions.47 Estates are effectively subject to a 40% rate on amounts above the statutorily exempted value, which was set at $11.18 million per decedent for 2018. The estate tax exemption was doubled temporarily through 2025 by the 2017 tax revision, P.L. 115-97.

Transfers to a spouse at death are also excluded from the estate tax, and any unused exemption can be added to the exemption of the second spouse. Because of the large exemption, a small share of estates are subject to the estate tax, although a significant share of charitable contributions made by bequests appear on estate tax returns. The increase in the exemption decreased the amount of bequests that receive a benefit from the charitable deduction.

The data from decedents dying in 2013 showed $18.1 billion of bequests reported on all estate tax returns, with $10.2 billion reported on taxable returns.48 Some of the bequests reported on nontaxable returns may benefit from the tax deduction, indicating a range of revenue costs from $4.0 billion to $7.2 billion.49 While there are no data available for the effects after the 2017 tax revision, estimates suggest a revenue cost of around $4 billion to $5 billion.50

Data Describing the Charitable Sector

The following sections describe the charitable sector. Specifically, data are presented on the size of the sector and the sector's revenues (including charitable contributions). Since the potential effect of the 2017 tax revision on charitable giving is a policy issue of interest, changes in charitable giving between 2017 and 2018 are examined in more detail.

The Size of the Charitable Sector

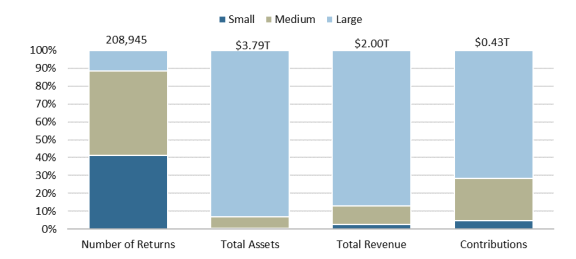

For 2015, 501(c)(3) organizations reported $3.8 trillion in total assets ($2.3 trillion in net assets) and total revenues of $2.0 trillion (or approximately 11% of GDP).51 Most of IRS Form 990 filers are small (assets of less than $500,000) or medium-sized (assets of $500,000 up to $10 million) charities (41.2% and 47.2%, respectively). Large organizations, those with at least $10 million in assets, were 11.6% of Form 990 filers. Assets and revenues, and to a lesser extent contributions, are concentrated in these larger organizations. While large organizations are 11.6% of charitable organizations filing Form 990s, 93.1% of assets are held by, 87.1% of revenues are received by, and 71.5% of contributions are made to these large organizations.

|

Figure 3. 501(c)(3) Organizations: Returns, Assets, and Revenue by Organization Size, 2015 |

|

|

Source: IRS Statistics of Income, Charities & Other Tax-Exempt Organization Statistics, Table 1. Form 990 Returns of 501(c)(3) Organizations: Balance Sheet and Income Statement Items, by Asset Size, Tax Year 2015, at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-charities-and-other-tax-exempt-organizations-statistics. Notes: Large organizations include those with assets over $10 million. Small organizations are those with assets under $500,000. Contributions includes all forms of gifts and grants, including charitable contributions, government grants, as well as contributions from related organizations and funds raised from fundraising events, through membership dues, or from federated campaigns. |

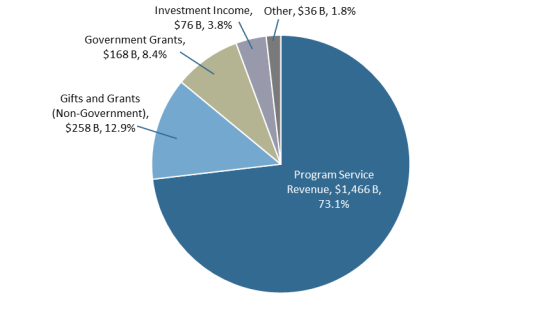

Charitable contributions are a small share of revenues of 501(c)(3) organizations reporting to the IRS, accounting for 12.9% of revenue in 2015 (Figure 4). The primary source of revenue (73.1%) is program services, such as tuition paid by college and university students, payments for hospital stays, and entry fees. Charitable organizations' revenue sources depend on the type of charity, with charitable giving, for example, being much less important for fee-for-service organizations such as educational institutions and hospitals. (These data represent those filing Form 990 returns. This excludes nonfiling religious organizations, which are likely to rely more on contributions.)

|

Figure 4. Sources of 501(c)(3) Organization Revenue, 2015 (in billions of dollars) |

|

|

Source: IRS Statistics of Income, Charities & Other Tax-Exempt Organization Statistics, Table 1. Form 990 Returns of 501(c)(3) Organizations: Balance Sheet and Income Statement Items, by Asset Size, Tax Year 2015, at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-charities-and-other-tax-exempt-organizations-statistics. Notes: Program service revenue includes fee-for-service revenue, such as tuition payments or hospital service revenue. Hospital service revenue may come from private or public sources. Gifts and grants include private contributions, as well as contributions from related organizations. |

Magnitude, Sources, and Beneficiaries of Charitable Giving

In absolute terms, charitable giving has increased over time. In 2015, total giving was $375.9 billion, including data not represented in the IRS data (primarily gifts to religious organizations). When considering the magnitude of the charitable sector in the economy, one metric is charitable giving as a share of GDP. In 2018, estimated total giving was $427.7 billion, or 2.1% of GDP.52

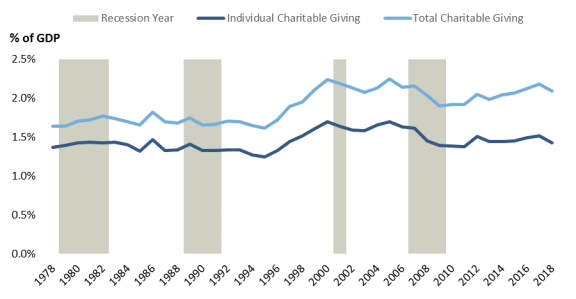

Charitable giving since 1978 has averaged 1.9% of GDP. However, as seen in Figure 5, this average obscures variation over time and across business cycles. The smallest share of charitable giving occurred in 1995 (1.6% of GDP) while the largest share occurred five years later in 2000 (2.2% of GDP).

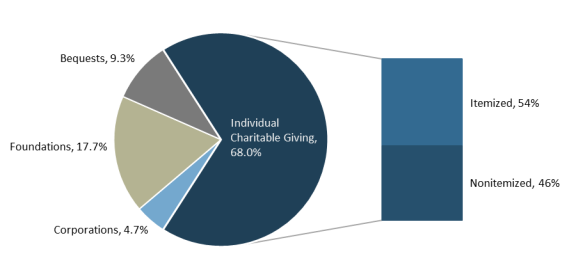

Private contributions to charitable organizations come from four different sources: individuals, foundations, bequests, and corporate giving. As shown in Figure 6, individuals were the largest source of charitable giving in 2018 and totaled $292.1 billion, or 68.0%. As estimated subsequently in this report, 54% of that giving received a tax benefit from itemized deductions. Grants from foundations were the second-largest source of charitable contributions in 2018 at ($75.9 billion, or 17.7%), followed by charitable bequests ($39.7 billion, or 9.3%) and corporate giving ($20.1 billion, or 4.7%).

|

|

Source: The Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University, Giving USA 2019; with CRS calculations for share of itemized and nonitemized giving. |

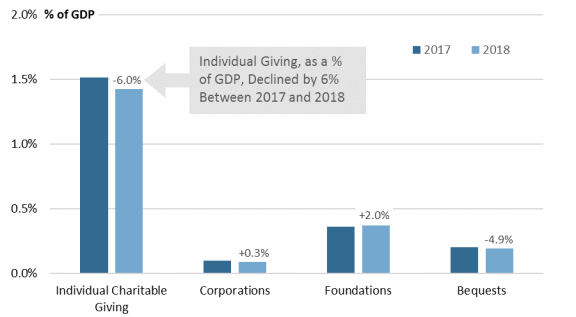

Changes in giving from different sources are consistent with expectations following the changes in incentives for giving resulting from the 2017 tax revision. As illustrated in Figure 7, individual giving as a percentage of GDP fell by 6.0% between 2017 and 2018. Individual giving was expected to fall as (1) fewer taxpayers itemized deductions; and (2) lower marginal tax rates reduced the incentive to give. Taxpayers may also have shifted the timing of gifts, making gifts late in 2017 instead of 2018 to take advantage of larger deductions in 2017, when tax rates were higher and more taxpayers itemized deductions.

Giving from bequests as a percentage of GDP fell by 4.9% between 2017 and 2018. The share of bequests on taxable estate tax returns declined following the tax law changes. In contrast, there was little change in corporate charitable giving as a percentage of GDP (an increase of 0.3%). For corporations, the large change in the corporate tax rate might have reduced the incentive to give. Giving from foundations as a percentage of GDP increased by 2.0% between 2017 and 2018. Foundation giving was less likely to be directly affected by the tax policy changes between 2017 and 2018 (although contributions to foundations and future foundation giving might be affected).

|

Figure 7. Charitable Giving by Source as a Percentage of GDP, 2017 and 2018 |

|

|

Source: The Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University, Giving USA 2019; and CRS. |

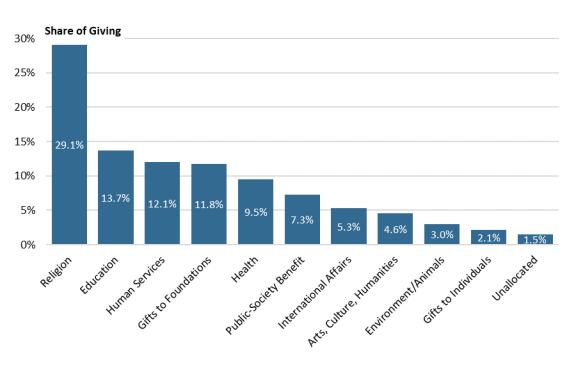

Religious charities receive the largest share of charitable giving, receiving 29.1% of total giving in 2018 (Figure 8). Education ranked next, at 13.7%, with human services 12.1%, gifts to foundations 11.8%, and health 9.5%. Other beneficiaries each accounted for less than 9.5%.53

|

Figure 8. Shares of Charitable Giving by Type of Recipient, 2018 |

|

|

Source: The Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University, Giving USA 2019. |

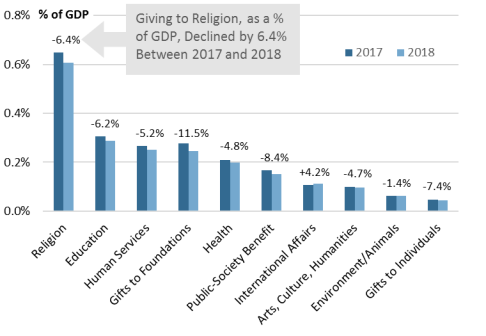

Giving to most beneficiaries as a percentage of GDP fell between 2017 and 2018, as shown in Figure 9, with the exception of gifts to international affairs.54 Giving to public-society benefit organizations as a percentage of GDP fell by 8.4%. Giving to religious organizations as a percentage of GDP fell by 6.4%, while giving to education as a percentage of GDP fell by 6.2%. Gifts to foundations as a share of GDP experienced a larger decline that other categories, falling by 11.5%.

|

Figure 9. Charitable Giving by Type of Recipient as a Percentage of GDP, 2017 and 2018 |

|

|

Source: The Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University, Giving USA 2019; and CRS. |

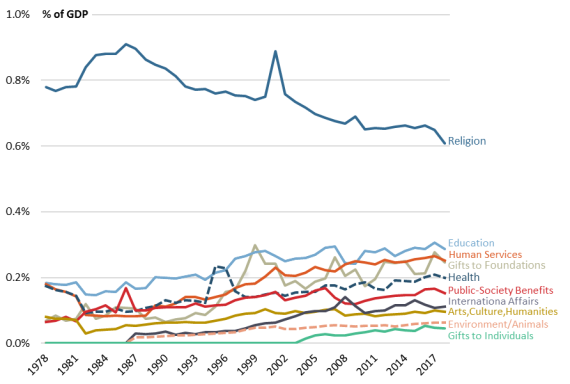

Giving to religion as a percentage of GDP and as a share of total giving has declined over time, as shown in Figure 10. Giving to most other beneficiaries has increased as a share of GDP, with the largest increases (in absolute terms) in giving to foundations and education. The decline in giving to religion from 2017 to 2018 may have just been part of a continuing trend, while the decline in giving to foundations may have reflected effects of the estate tax, or have been part of regular fluctuations in giving to foundations.

|

Figure 10. Trends in Charitable Giving by Type of Recipient, 1978-2018 |

|

|

Source: The Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University, Giving USA 2019. |

The Incentive Effects of Tax Benefits for Charitable Contributions and Organizations

To understand how much charitable giving is induced by tax incentives, it is important to understand how donors respond to tax incentives. Individuals give for a variety of reasons (e.g., altruism); research indicates that tax benefits may also influence charitable giving. Tax benefits encourage charitable giving by reducing the cost of giving, with the federal government effectively subsidizing charitable giving.

For ordinary donations during donors' lifetimes (inter-vivos giving) and for donors not claiming the standard deduction, their marginal income tax rate determines the incentive effect by lowering the cost of giving. Donors who do not claim itemized deductions do not receive an incentive effect from the tax code. For gifts of appreciated property, subsidies are affected by the capital gains tax rate as well, regardless of whether itemized deductions are used. For bequests, the tax rate is the estate tax rate, but only a small fraction of estates are subject to tax. Corporate giving is potentially affected by the corporate tax rate.

Taxes also have income effects, which may be important for wealthy donors who donate large shares of income or leave large shares of their estates to charity; taxes reduce charitable giving by reducing disposable income. Deductions for charitable contributions not only provide a tax incentive for donating or leaving bequests, but also have an income effect that increases giving.

Tax Subsidies for Charitable Giving, Inter-Vivos Giving

Taxpayers who itemize their deductions face a lower cost of giving than other taxpayers. Prior to the 2017 tax revision, the majority of individuals' charitable giving was deducted. For the most recent year of tax data available, 2016, charitable deductions of $233.9 billion were reported on tax returns, although $12.3 billion of that number was on returns with no ultimate tax liability.55 According to Giving USA, in that same year individuals donated $279.4 billion,56 indicating that approximately 80% of charitable deductions benefited from some subsidy in that year. Taxpayers with $500,000 of adjusted gross income or more, representing slightly under 1% of returns, accounted for 38% of charitable contributions. Taxpayers with $100,000 to $500,000 of income, slightly over 16% of returns, accounted for 38% of itemized charitable contributions as well.

The amount of giving that benefits from tax reductions through itemized deductions is expected to have declined substantially in 2018 due to provisions of the 2017 tax revision.57 (Actual data on charitable deductions claimed from the IRS based on 2018 tax returns are not yet available.) This legislation is expected to decrease the share of itemizers due to a significant increase in the standard deduction58 and restrictions on itemized deductions, most importantly a $10,000 cap on deductions for state and local taxes. The Tax Policy Center (TPC) estimated the share of households reporting a benefit from deducting charitable contributions would fall from 21% to 9.1%.59 (This share reflects the share of the entire population, including nonfilers.)

Data from the TPC that estimate itemized charitable contributions can be used to estimate the share of individual charitable contributions that would be claimed as itemized deductions. For 2018, TPC estimates that itemized charitable deductions would have been $212.1 billion without the 2017 tax revision, with itemized deductions for charitable giving being an estimated $143.1 billion as a result of the 2017 tax revision.60 In other words, charitable contributions itemized on individual income tax returns are estimated to have fallen by about one-third as a result of the 2017 tax revision. Assuming a similar level of itemized deductions in 2018 under prior law as reflected in actual data for 2016 (80%), the share of charitable contributions itemized would be projected at 54%.61

The tax savings from charitable contributions reflecting both the decline in itemizing and the small decline in tax rates also fell by about a third. The steepest declines were in the middle and upper middle of the income distribution (the benefit fell by 62% in the fourth quintile, while the benefit fell by 1.4% in top 0.1%). The TPC reported that taking into account all returns (including those not itemizing before the tax change), the average marginal tax rate across all donations fell from 20.7% to 15.2%.62

Gifts of Cash

About two-thirds of charitable contributions in 2016 were in cash, and high-income taxpayers have a smaller share of cash contributions (47% in 2016 for taxpayers with income greater than $1 million).63 The price of charitable contributions for itemizers is (1-t), where t is the taxpayer's tax rate at which contributions are deducted.64 For example, if the individual is in a 25% tax bracket, every dollar the taxpayer donates and deducts from their income reduces their taxes by 25 cents. Hence, the tax price is 0.75, indicating that a taxpayer has to give up 75 cents for each dollar of charitable contributions. That is, if the taxpayer in that bracket contributes a dollar, he or she saves 25 cents in taxes and loses 75 cents that could have been used for other purposes.

Charitable giving is concentrated at higher income levels, and the effect of the incentive depends on the tax rate. Consider the top tax rate (applicable for taxpayers with very high income levels), which has fluctuated substantially since the income tax was introduced in 1913, beginning at rates as low as 7% and rising as high as 92%. Starting in the mid-1960s, the top rate was 70% for many years (although it rose slightly with the Vietnam War surcharge). Beginning with legislation in 1981, the top tax rate has been reduced substantially. Effective in 1982, it was reduced from 70% to 50%. In 1986, it was further reduced to 28%. Rate increases occurred in 1990 and 1993, decreases in 2001, increases in 2013, and decreases in 2017. Table 3 compares the magnitude of those past changes in tax price. Importantly, as marginal tax rates fall, the tax price of giving increases—in effect, the subsidy from the charitable deduction is reduced. Conversely, when marginal rates increase, the tax price of giving falls, and the subsidy of the charitable deduction increases. There were very large percentage changes in the 1981 and 1986 tax cuts, with much smaller changes subsequently. The effect of the top rate change in 2017 is relatively small compared to these earlier changes.

The TPC estimated that across all taxpayers the tax price rose by 6.9%, to reflect the change in itemized deductions as well as the small change in tax brackets.

|

Original Tax Rate (%) |

Enacted Tax Rate (%) |

Percentage Change in Tax Price |

|||||||

|

2017 Tax Cut |

|

|

|

||||||

|

2013 Tax Increase |

|

|

|

||||||

|

2001 Tax Cut (Effective 2003) |

|

|

|

||||||

|

1993 Tax Increase |

|

|

|

||||||

|

1990 Tax Increase |

|

|

|

||||||

|

1986 Tax Cut |

|

|

|

||||||

|

1981 Tax Cut |

|

|

|

Source: CRS calculations.

Gifts of Appreciated Property

The value of donating property differs from the value of cash donations; most property is appreciated property such as stocks and other property gaining value. Taxpayers with incomes of $500,000 or more account for 69% of these contributions. Currently, taxpayers are allowed to deduct the entire cost of donated property, without paying the capital gains tax. Since the cost of a dollar of consumption from sale of an appreciated asset is 1/(1-atg), where tg is the capital gains tax rate and a is the share of value that would be taxed as a gain, the tax price of charitable giving of appreciated property is (1-t)/(1-atg). The tax price effects in Table 3 reflect tax prices of assets with no appreciation. Table 4 shows the effects at the top rates for cases with appreciation of 50% of the value and 100% of the value. An appreciation approaching the full value would occur with assets that have been held for a long time and had a faster growth rate.

Although changes in capital gains tax rates in isolation can affect the price of giving (for example, causing an increase in the price of giving by up to 10% in 1997), they sometimes offset the effects of a change in ordinary rates (as in 1986) and at other times exacerbate the effects. As with cash gifts, however, the largest changes to the tax price of appreciated property occurred in 1981 followed by 1986, where the price of charitable giving increased; the largest price decrease remains in 1993.

|

Year |

Prior-Year Ordinary Tax Rate (%) |

Enacted Ordinary Tax Rate (%) |

Prior-Year Capital Gains Tax Rate (%) |

Enacted Capital Gains Tax Rate (%) |

Price Change with 50% of Value in Appreciation (%) |

Price Change with 100% of Value in Appreciation (%) |

||||||||||||

|

2017 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2003 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

2001 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

1997 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

1993 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

1990 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

1986 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

1981 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

1978 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: CRS calculations.

Tax Incentives for Bequests

A small share of estates are subject to the estate tax, and that share has been further reduced by the 2017 tax revision, which doubled the estate tax exemption. According to the TPC, 0.2% of deaths were subject to the estate tax before the change, which fell to 0.1% after the increase in the exemption.65

The latest IRS estate tax data are for decedents dying in 2013, before enactment of the 2017 tax revision. These data showed $18.1 billion of bequests reported on all estate tax returns, with $10.2 billion reported on taxable returns.66 The amount potentially benefiting from the estate tax deduction presumably fell between those two values, as the charitable deduction could have resulted in some estates not being taxable. Giving USA reported bequests of $26.3 billion in 2013 and $28.1 billion in 2014;67 thus, between 30% and 53% of bequests received the benefits of estate tax deductions.

The tax price of a bequest is (1-te), where te is the estate tax rate. The capital gains tax rate does not apply because the capital gain on assets passed on at death is not recognized. The current estate tax rate is 40%. The estate tax rate has fluctuated over time. From the post-World War II period to 1976, the top rate was 77%, when it was reduced to 70%. In 1981, the rate was reduced over a three-year period to 55% from 1982 to 1984, an increase in tax price of 50%. The estate tax rate was lowered from 55% to 45% over the period from 2002 to 2007, a 22% price increase. The estate tax was repealed for 2010, an 82% increase in the tax price (although individuals were retroactively allowed to pay an estate tax at 2011 rates of 35% to avoid a provision that would have required future capital gains to be recognized on sale by heirs, called carryover basis). For those electing the 2011 tax rate, the price increase was 18%. The tax rate was reduced to 35% temporarily for 2011 and 2012; in 2013, the rate was set at 40%, a decrease in the tax price compared to the temporary rates of 8%. Aside from the year of repeal in 2010, the largest price increase was 50%, and significant price changes were fewer than for inter-vivos gifts.

The benefits of the subsidy for bequests are also affected by the exemption, and the recent increases in exemptions make the tax subsidy less applicable—reducing the tax incentive for charitable bequests. Nevertheless, for bequests reported on estate tax returns, these bequests are concentrated in large estates. The 2013 estate tax data report only estates of $5 million or more, since smaller estates would be exempt, but 57% of contributions on these estates were in estates of $50 million or more, and 74% were reported for estates of $20 million or more. For taxable estates, 78% were reported on estates of $50 million or more, and 92% were reported on estates of $20 million or more. Thus, it appears that most charitable contributions that benefited from the tax subsidy would continue to do so under the new exemption level.

Incentives for Corporate Giving

Corporate giving is a relatively small share of total giving. In 2013, the last year for which tax data were available, tax statistics indicated total contributions of $15.9 billion, while Giving USA reported $20.05 billion in 2018.68

The incentive effects for corporate giving depend on the motivation. If charitable contributions are an expenditure for purposes of advertising and public relations, the deduction is like any other cost, and the corporate tax rate does not matter. If the contribution increases the welfare of managers, the donation reduces profit, and the corporate tax matters.69

To the extent that the corporate tax price affects charitable giving, the tax price has changed infrequently. In 1981, the corporate tax rate was 46%. The 1986 legislation phased the rate down over two years to 34%, increasing the tax price by 22%. In 1993, the corporate tax rate increased to 35%, for a small tax price reduction of less than 2%. The corporate tax rate stayed at that level, until 2018, when the rate was reduced to 21%, for a tax price increase of 25%.

Accumulating Earnings Tax Free

Numerous opportunities are available for adding to the tax benefit of a charitable contribution by accumulating earnings that are not subject to tax. In effect, the deduction for the charitable contribution is provided before it is actually spent on charitable activity. An example illustrates this point. If the interest rate is 10%, a dollar donated today and spent a year later by a tax-exempt charity will provide $1.10 in resources. If a taxpayer is subject to the 37% top tax rate on the earnings, the amount available to give to charity after paying taxes is $1.063. In the tax-exempt case, the tax price of giving is $0.61, while the tax price of giving in the taxable case is $0.63.70 The longer the asset is held by a tax-exempt entity, the greater the benefit to the charitable organizations: after 10 years tax-exempt accumulation leads to $2.69, while the amount available after paying tax is $1.84.

There are a number of ways to accumulate funds without paying taxes on earnings, most notably through foundations, although they are required to pay out a minimum amount each year in charitable purposes. Other methods of delaying the payment of taxes is through private charities' endowment funds and supporting organizations, and well as DAFs, none of which is subject to payout restrictions. A DAF can act, in many ways, as a private foundation but without many of the restrictions of a private foundation. Taxing these earnings directly at the corporate rate would reduce the tax incentive for those subject to high individual marginal tax rates, but not eliminate it, given the lower corporate rate now in place.

The Aggregate Effect of Tax Incentives on Giving

As previously discussed, the effect of changes in tax incentives on giving depends on the behavioral response to changes in tax rates. The measure is a price elasticity, which is the percentage change in charitable contributions divided by the percentage change in the tax price (in the case of individual cash giving, the tax price is one minus the tax rate).

Given the large changes in tax price that have occurred over time, it is useful to examine some historical data. Figure 5 above shows the pattern of giving as a percentage of GDP over the period 1978-2018. There is little indication of significant shifts in giving due to tax rate changes. Contributions after 1981, despite pronounced tax price increases at higher incomes, remained relatively stable as a percentage of GDP. The small peak around 1986 is generally attributed by most researchers to a temporary rise in deductions reflecting a timing shift as tax cuts for 1987 and 1988 were preannounced in the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA86; P.L. 99-514), but by 1989 contributions had returned to their previous levels. Contributions following enactment of the 1993 tax increase fell rather than increased. Thus, there is little in the historical record to suggest a significant response to changes in tax incentives.

Economists have employed a variety of statistical methods to try to formally estimate the effects of tax incentives on charitable giving. The effects can be measured by estimating a price elasticity, which is the percentage change in charitable contributions divided by the percentage change in tax price. Since increasing the price of giving will reduce the amount of giving (and vice versa), the price elasticity is a negative number. For example, if the elasticity is -0.7, a 10% increase in the tax price (1-t) will result in a 7% decrease in the amount of charitable contributions.

Individual Charitable Contributions

Some early statistical estimates indicated that giving was very responsive to the tax rate. The temporary increase in individual charitable contributions following the 1986 tax revision, where lower tax rates were announced in advance, caused researchers to suspect that some of these estimated effects were due to transitory changes. The most common instance of this transitory effect would be when income fluctuated: the periods when income rises and individuals are in higher tax brackets would be the best time to concentrate charitable giving. Thus, some of the relationship between high tax rates and higher contributions reflected timing and would overstate the response (i.e., the elasticity) to a permanent tax change. Statistical estimates are also made more difficult because charitable giving responds to income, so that higher incomes lead both to higher charitable contributions and, in a progressive tax rate system, to higher tax rates.

Appendix A contains a review of studies of the price elasticity of charitable giving that control for transitory effects. The elasticities in those studies range from close to 0 to -1.2. The review of that evidence points to an elasticity of around -0.5. That elasticity would imply that the percentage change in individual charitable contributions due to the 2017 tax revision (where the price rose by 7%) was a 3.5% decline in individual charitable contributions. For 2017, individual giving was $302.5 billion,71 suggesting a decline in charitable contributions of around $11 billion as a result of the 2017 tax revision. With a current average tax rate for individual contributions of 15.2%, the tax price would rise by 9% if all charitable deductions were eliminated. These effects would be twice as large with an elasticity of -1.0. The National Council on Nonprofits has estimated a similar effect of the 2017 tax change for individual contributions, a decline in charitable giving of $13 billion or more.72

As a percentage of GDP, individual giving declined by about 6% from 2017 to 2018. Some of that decline might reflect a shift in giving from 2018 to later in 2017, to take advantage of the higher tax rates or the expectation of taking the standard deduction in the following year. Contributions as a percentage of GDP grew about 1.4% from 2016 to 2017.73 Many other factors, however, influence giving as a percentage of GDP, and individual giving as a share of GDP in 2018 was about the same as in 2015.

A Note on Beneficiaries of Charitable Tax Incentives

The 2017 tax revision eliminated many charitable deductions taken for the middle and upper-middle-income taxpayers, leaving a charitable tax incentive mostly claimed by high-income individuals. The TPC estimates that in 2018 91.5% of the benefit for charity accrues to the top quintile (taxpayers with incomes of $153,300 or more), 83.5% is received by the top 10% (taxpayers with incomes of $222,900 or more), 56.4% is received by the top 1% (taxpayers with incomes of $754,800 or more), and 35% accrues to the top 0.1% (taxpayers with income of $3,318,600).74

The 2017 Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) can be used to examine the patterns of giving by income class to different types of charitable organizations and also to examine the share of contributions likely to benefit low-income individuals (i.e., that go to charities and foundations that serve the poor).75 According to CRS's analysis of the PSID data, higher-income individuals give a larger share of their contributions to organizations that focused on health, education, arts, the environment, and international aid relative to contributions by lower-income individuals, while giving a smaller share to organizations focused on religion, youth and family services, community improvement, and directly providing basic necessities. For example, nearly two-thirds of contributions of those with incomes under $200,000 went to religious organizations, compared to roughly 47% for those with incomes over $200,000. In contrast, just over 5% of giving from families with income under $200,000 was directed to education purposes, compared to almost 19% for those with income over $200,000.

The PSID data can also be used to estimate the share of various charitable benefits focused on the needs of the poor.76 Nearly 36% of charitable giving made by families with income under $200,000 was focused on the poor, compared to nearly 33% for families with income over $200,000. While the PSID sample sizes limit the ability to draw conclusions about charitable giving at very high income levels (greater than $1,000,000), they are suggestive that the share focused on the poor may further decline as income levels increase.

As the changes from the TCJA resulted in a further concentration of charitable incentives toward high-income taxpayers, they also focused incentives on charitable giving less likely to benefit the poor and more likely to benefit organizations that focus on health, education, arts, the environment, and international aid.

Although it is difficult to separate various causal factors, the recipient organizations that experienced the largest decline in giving in 2018 were foundations, although there was also extraordinary growth in giving to foundations in 2017. Foundations may be the most likely beneficiary of transitory giving (in this instance, making of gifts that otherwise might be made in 2018 into 2017). Other recipient organizations that saw larger declines in donations were public society benefit (an umbrella for many types of organizations),77 religious organizations, and educational organizations. Beneficiary organizations that saw an increase in donations or smaller declines were international affairs, environment and animals, arts, and health.78 Again, it is difficult to determine any causal relationships; for example, religious giving has been declining as a share of total giving for many years.

Bequests

Empirical estimates of the price elasticities for bequests are also reported in Appendix A. These estimates also vary significantly, although the evidence suggests they are more responsive to taxes than inter-vivos contributions. In the following calculations, an elasticity of -2.0 is used.

It is difficult to determine the effect of the recent changes in the exemption in the 2017 act because the share of bequests reported on estate tax returns differs substantially from the share represented by taxable returns (30%) and the share represented by all returns (53%). Some returns that would have been taxable without the charitable deduction but are not taxable without the deduction benefit from the incentive. In addition, a much smaller share of taxable estate returns would fall below the exemption for taxable returns. Assuming that the share with an estate of less than $20 million would no longer be subject to the estate tax, that share is 92% for taxable returns, indicating 2.4% of bequests would lose the tax incentive (8% of 30%). For all estates the share is 74%, which suggests 13.8% of bequests would lose the benefit of the charitable deduction (26% of 53%).

The tax price increase for those estates affected by the TCJA is 66%. Such a large price increase does not permit the use of a point elasticity estimate, so the underlying exponential formula is used, leading to a reduction in affected estates of 64% with an elasticity of -2.0.79 These calculations produce a range of percentage reductions in total bequests of 1.5% (0.64 times 2.4%) to 8.8% (0.64 times 13.8%). Bequests were $39.7 billion in 2017,80 suggesting a decline in bequests ranging from $0.6 billion to $3.5 billion. This same methodology can be used to estimate the effect on bequests of either eliminating the charitable deduction or repealing the estate tax, which would result in a further reduction of $7.0 billion to $10.0 billion.81 These estimates depend, however, on the elasticity. Excluding the one study that found no effect, the smallest elasticity estimated (-0.6) would result in an effect 30% smaller, and the largest (-3.0) would result in an effect 22% larger than these amounts.

The National Council on Nonprofits has estimated a decline in bequests of $4 billion as a result of the 2017 tax revision.82 Because bequests vary considerably from year to year (and can be affected by very wealthy decedents as well as economic factors), examining changes from the previous year provides a limited amount of information.

Corporate Giving

As noted above, some theories of corporate giving suggest that taxes do not affect a decision that is made for purposes of maximizing profits by generating advertising and goodwill. Empirical studies of the response are limited, dated, and quite mixed, including findings of large responses, small responses, no responses, and responses that are positive rather than negative.83 All of these findings make estimated effects on giving responses difficult to determine, although the corporate rate cut in 2017 substantially increased the tax price (by 22%) to the extent giving provided a benefit to managers. Corporate giving constituted the smallest share of total giving, amounting to $19.5 billion in 2017; therefore, the effects of the TCJA on overall corporate giving are likely small.

Policy Options

Some proposals to revise the tax treatment of charitable giving are aimed at increasing the incentive to give or changing the distribution of incentives across donors, while others are aimed at what may be perceived as abuses.

Options Related to Tax Incentives for Charitable Giving

Deduction for Nonitemizers

As mentioned previously, tax incentives for giving are largely confined to higher-income households because these taxpayers are more likely to itemize their deductions (largely deductions for state and local taxes, mortgage interest, and charitable contributions), which tend to rise with income, or choose the standard deduction of a fixed dollar amount. This concentration of tax benefits on higher-income individuals also tends to favor the charities they favor, such as those pertaining to health, education, and the arts, while disfavoring religion and charities aimed at human services. The concentration of charitable giving incentives to those with higher incomes has increased as a result of the 2017 tax revision.

Nonitemizers were able to claim a deduction for charitable contributions in the early 1980s. A temporary charitable deduction for itemizers was adopted in the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (P.L. 97-34), initially allowing a deduction for 25% of contributions in 1982-1984, 50% in 1985, and a full deduction in 1986, with the provision then expiring. The deduction was also capped in the first three years, at $100 in the first two years and $300 in the third year.

Over time, policymakers have continued to propose policies that would extend charitable tax benefits to all taxpayers, either by allowing a deduction for nonitemizers (often termed an above-the-line deduction, reflecting its position on the tax form) or by replacing the itemized deduction with a credit available to all taxpayers.84 In the 116th Congress, Representative Danny Davis has introduced legislation that would allow an above-the-line deduction for charitable giving H.R. 1260), as have Representatives Henry Cuellar and Christopher Smith (H.R. 651). (A similar bill was introduced in the 115th Congress as H.R. 5771.) Earlier proposals for an above-the-line charitable deduction include the Universal Charitable Giving Act of 2017 (H.R. 3988/S. 2123) in the 115th Congress, introduced by Representative Mark Walker in the House and Senator James Lankford in the Senate.85 In the 116th Congress, Representative Danny Davis has introduced legislation that would allow an above-the-line deduction for charitable giving (H.R. 1260), as have Representatives Henry Cuellar and Christopher Smith (H.R. 651). (A similar bill was introduced in the 115th Congress as H.R. 5771.)

Different models have been used to estimate the budgetary cost of a nonitemizer deduction. Using the Penn-Wharton Budget Model, the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy estimates a nonitemizer deduction would cost between $14.4 billion and $16.1 billion in 2020 (see Table 5 for a summary of the revenue and charitable giving effects of the policy options evaluated in the study).86 Building on the Open Source Policy Center's Tax Calculator, Brill and Choe estimated such a change would cost $25.8 billion at 2018 levels (the revenue and charitable giving effects of the policy options in the study are summarized in Table 6).87

These studies also estimated the effect of the proposals on charitable giving. One concern is whether further encouraging charitable contributions is an efficient way of achieving the benefits such charitable giving might bring. In general, if the price elasticity of giving is less than 1.0, the induced charitable giving will be less than the revenue cost, and more charitable giving could be obtained by making direct expenditures. If the elasticity is greater than 1.0, charitable giving will be greater than the revenue loss. (This argument also applies to existing charitable deductions.)

Table 5. Revenue Loss and Induced Charitable Giving in Various Policy Scenarios: Indiana University Study/Penn-Wharton Budget Model

(in billions of dollars)

|

Projected Revenue Loss |

Estimated Increase in Charitable Giving |

||||||||||||

|

2020 |

2020-2029 |

2020 |

2020-2029 |

||||||||||

|

Nonitemizer Deduction |

|||||||||||||

|

Static |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Low Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

High Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Income-Based Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Enhanced Nonitemizer Deduction |

|||||||||||||

|

Static |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Low Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

High Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Income-Based Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Nonrefundable 25% Nonitemizer Credit |

|||||||||||||

|

Static |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Low Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

High Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Income-Based Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Nonitemizer Deduction with Cap |

|||||||||||||

|

Static |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Low Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

High Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Income-Based Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Nonitemizer Deduction with AGI Floor |

|||||||||||||

|

Static |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Low Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

High Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Income-Based Elasticity |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

Source: The Indiana University Lilly School of Philanthropy, Charitable Giving Tax Incentives: Estimating Changes in Charitable Dollars and Number of Donors Resulting From Five Policy Proposals, 2019, at http://hdl.handle.net/1805/19515; and John Ricco and Mariko Paulson, Policy Options to Increase Charitable Giving Using Tax Incentives, Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, June 24, 2019, at https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2019/6/24/policy-options-to-increase-charitable-giving-using-tax-incentives.

Notes: The "low" tax price elasticity is -0.5. The "high" tax price elasticity is -1.0. The "income-based" elasticity is -2.236 for tax units under $50,000 in 2017 AGI, -1.49 under $100,000, and -1.182 over $100,000.

Brill and Choe used a unitary elasticity (an elasticity of -1.0) in their study, but found a smaller increase in charitable contributions ($21.5 billion) than the lost revenue (the absolute value of lost revenue) when evaluating an above-the-line or nonitemizer deduction. Presumably some additional revenue beyond the amount of induced giving is lost because some itemizers would move to the standard deduction, causing a loss of revenue unrelated to the charitable incentive. (Even very-high-income individuals who had no mortgages might be better off moving to a standard deduction because of the $10,000 cap on state and local tax deductions; the standard deduction for a married couple is $24,000).

Table 6. Options to Increase Charitable Giving and the Associated Revenue Loss: Brill and Choe/Open Source Policy Center's Tax Calculator

(in billions of dollars)

|

Projected Revenue Loss, 2018 |

Estimated Increase In Charitable Giving, 2018 |

|||||

|

Nonitemizer Deduction |

|

|

||||

|

Nonitemizer Deduction with Floor |

|

|

||||

|

Nonrefundable 25% Credit for All |

|

|

||||

|

Nonrefundable 25% Credit with Floor |

|

|

Source: Alex Brill and Derick Choe, Charitable Giving and the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, AEI Economic Perspectives, June 2018, at http://www.aei.org/publication/charitable-giving-and-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act/.

Note: The price elasticity of charitable giving is assumed to be -1.0.

The Indiana University study looks at giving under a "low-elasticity" scenario (an elasticity of -0.5), a high-elasticity scenario (an elasticity of -1.0), and an income-based elasticity scenario. The increase in giving in 2020 under each scenario was $8.4 billion, $16.8 billion, and $24.9 billion, respectively. Under the low-elasticity scenario, an above-the-line deduction for giving would reduce revenues by $15.0 billion in 2020, while generating $8.4 billion in additional charitable giving. Under the high-elasticity scenario, the revenue reduction in 2020 is estimated at $15.5 billion, with additional charitable giving estimated at $16.8 billion.88 In the income-based elasticity scenario, the revenue reduction in 2020 is $16.1 billion, while additional charitable giving is $24.9 billion in 2020.89 Thus, if elasticities are less than 1.0, as the survey of studies accounting for transitional effects in Appendix A indicates, charitable deductions would likely be smaller than the revenue cost.

In evaluating the trade-off between revenue loss and charitable contributions, the charitable contributions from an above-the-line deduction would tend to go to charitable causes favored by lower- and middle-income taxpayers. These include religion, youth and family services, community improvement, and directly providing basic necessities. If the desired objective is to increase resources devoted to these activities, additional resources could be provided directly by the federal government, instead of induced via charitable giving incentives (which result in a loss in federal revenue).

The Indiana University study also looks at a scenario that would provide an enhanced nonitemizer deduction. In this policy, single filers with less than $20,000 in income ($40,000 for joint filers) would be able to deduct 200% of their charitable contributions. Taxpayers making less than $40,000 ($80,000 for joint filers) would be able to deduct 150% of their contributions. Under this policy, revenue losses would be between $15.9 billion and $18.2 billion in 2020, depending on the elasticities assumed. Charitable giving would increase by an estimated $9.2 billion to $27.7 billion, with the rise in giving greater than the loss in revenue in both the high-elasticity and income-based-elasticity case.90 This policy would tend to encourage additional giving by lower-income taxpayers.

Adding a deduction for nonitemizers (or replacing the existing itemized deduction with a credit, as discussed below) would increase the complexity of the tax code for the individuals now taking the standard deduction. Charitable deductions require various types of substantiation and recordkeeping, and it is difficult for the IRS to monitor these contributions, especially with respect to small contributions where audit and investigation by the IRS are not cost effective. Charitable deductions are among the items with no third-party reporting, which makes enforcement more costly and difficult.

Allowing a charitable deduction or credit to be taken regardless of whether a taxpayer itemizes or takes the standard deduction would further increase the share of taxpayers who take the standard deduction rather than itemizing deductions. The remaining major itemized deductions are state and local taxes and mortgage interest. Such a move would, for example, reduce the incentives for owner-occupied housing even further than the effects of the 2017 tax revision, which some might see as desirable and others as undesirable.

A Tax Credit for Charitable Giving

An alternative to a nonitemizer deduction is to provide for a nonrefundable tax credit. It could either be as a substitute for or an addition to the current itemized deduction. Both the Indiana University and Brill and Choe studies estimate revenue effects and increased charitable contributions for a 25% credit. Indiana University considers a credit as an addition to the current itemized deduction, with an estimated revenue cost in 2020 of $20.6 billion to $24.6 billion, depending which elasticity is assumed.91 Brill and Choe consider a 25% credit that replaces the current itemized deduction, costing $31.1 billion at 2018 levels.

Brill and Choe estimate the credit would (at their assumed -1.0 price elasticity) increase charitable giving by $23.3 billion. The Indiana University study estimates increased contributions in 2020 of $35.1 billion for the higher income-based elasticities, $22.8 billion for the elasticity of -1.0, and $11.4 billion for an elasticity of -0.5.

The induced contributions associated with the elasticities of -1.0 and -0.5 are smaller than the revenue losses and raises the basic concerns about the tradeoff between revenue loss and contributions. If the credit replaced the itemized deduction, it would shift more of the incentive to lower- and middle-income individuals by creating the same tax price for all taxpayers and thus to their preferred beneficiaries. Expanding the scope of the benefit for charitable contributions would, like a deduction, tend to increase complexity in compliance and tax administration, as well as potentially reduce the incentive for home ownership by reducing the number of itemizers.

If a credit substituted for the itemized deduction, it would be possible to set the credit so as not to lose revenue while equalizing the treatment of the charitable contribution incentive across taxpayers. For example, in a 2011 report by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), an option of a 15% credit was considered, which, compared to a 25% credit, would have cost $20.4 billion less in 2006 dollars, and a larger amount at current income levels.92

Modifying Charitable Giving Incentives: Caps and Floors

Some proposals would cap expanded deductions. For example, the Universal Charitable Giving Act of 2017 (H.R. 3988/S. 2123) in the 115th Congress would have limited the nonitemizer deduction to be one-third of the standard deduction that was available at that time. When a nonitemizer deduction was available in the early 1980s, it was limited to a certain percentage of contributions in the first three years of the temporary policy. Proposals have also been made to provide a floor, either under nonitemizer deductions or all deductions.

Caps