Recent Developments

On May 29, 2019, the government of Norway confirmed that the representatives of the main political actors in Venezuela had returned to Oslo "to move forward in the search for an agreed-upon and constitutional solution for the country." (See "Foreign Involvement in Venezuela's Political Crisis," below.)

On May 25, 2019, the U.S. Department of State stated that "the only thing to negotiate with Nicolás Maduro is the conditions of his departure.… [If] the talks in Oslo will focus on that objective … we hope progress will be possible." (See "U.S. Policy," below.)

On May 22, 2019, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee ordered S. 1025, a comprehensive bill to address the crisis in Venezuela, to be reported with an amendment to include three House-passed measures: H.R. 854 would authorize expanded humanitarian aid, H.R. 920 would restrict arms transfers to Maduro, and H.R. 1102 would require an assessment of Russian-Venezuelan security cooperation. (See Appendix A, below.)

On May 22, 2019, the House Judiciary Committee ordered reported H.R. 549 to make certain Venezuelans in the United States eligible for Temporary Protected Status. A companion bill (S. 636) has been introduced in the Senate. (See Appendix A, below.)

On May 19, 2019, the interim government led by Juan Guaidó hired a prominent sovereign debt lawyer, Lee Buchheit, on a pro bono basis to help restructure the country's $150 billion in outstanding debt should it obtain complete control in Venezuela. (See "Economic Crisis," below.)

On May 16, 2019, an ad hoc board of directors of Petróleos de Venezuela, S. A. (PdVSA)—Venezuela's state-owned oil company—appointed by Venezuela's interim government made a $71 million interest payment on PdVSA bonds maturing in 2020. Defaulting on the PdVSA 2020 bonds could have resulted in legal challenges by creditors and the seizure of U.S. refiner Citgo, owned by PdVSA. (See "Energy Sector Concerns and U.S. Economic Sanctions," below.)

On May 15, 2019, the U.S. Department of Transportation ordered flights between the United States and Venezuela to be suspended due to information the agency obtained from the Department of Homeland Security that "conditions in Venezuela threaten the safety and security of passengers, aircraft, and crew traveling to or from that country." (See "U.S. Policy," below.)

On May 8, 2019, Venezuelan intelligence agents arrested the vice president of the National Assembly, Edgar Zambrano, reportedly for his involvement in a failed uprising against authoritarian leader Nicolás Maduro on April 30, 2019 (See "Human Rights," below.)

On April 30, 2019, Guaidó and Leopoldo López, a former political prisoner and head of the Popular Will (VP) party who had been released from house arrest by pro-Guaidó military officials, called for a civil-military rebellion against Maduro. Forces loyal to Maduro violently put down pro-Guaidó supporters and attacked journalists. López sought refuge in the Spanish embassy. (See "Maduro's Second Term Deemed Illegitimate; Interim Government Formed," below.)

On April 10, 2019, United Nations humanitarian experts updated the U.N. Security Council on the humanitarian situation in Venezuela, estimating that some 7 million Venezuelans were in need of humanitarian assistance. (See "Humanitarian Situation" below.)

Introduction

|

Venezuela at a Glance Population: 28 million (2019 est., IMF) Area: 912,050 square kilometers (slightly more than twice the size of California) GDP: $76.5 billion (2019, current prices, IMF est.) GDP Growth: 18% (2018, IMF est.) GDP Per Capita: $2,724 (2019, current prices, IMF est.) Key Trading Partners: Exports—U.S.: 35.2%, India: 21.4%, China: 15.2%. Imports—U.S.: 51.5%, China: 15.7%, Brazil: 13.8% (2019, EIU) Unemployment: 44.3% (2019, IMF) Life Expectancy: 74.7 years (2017, UNDP) Literacy: 97.1% (2016, UNDP) Legislature: National Assembly (unicameral), with 167 members; National Constituent Assembly, with 545 members (United States does not recognize) Sources: Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU); International Monetary Fund (IMF); United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). |

Venezuela, long one of the most prosperous countries in South America with the world's largest proven oil reserves, continues to be in the throes of a deep political, economic, and humanitarian crisis. Whereas populist President Hugo Chávez (1999-2013) governed during a period of generally high oil prices, his successor, Nicolás Maduro of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), exacerbated an economic downturn caused by low global oil prices through mismanagement and corruption. According to Freedom House, Venezuela fell from "partly free" under Chávez to "not free" under Maduro.1 On January 10, 2019, Maduro took office for a second term after winning an election in May 2018 that was deemed illegitimate within Venezuela and by the United States and more than 50 other countries.2 Maduro has resisted domestic and international pressure to leave office and allow an interim government led by Juan Guaidó, president of the National Assembly, to serve until free and fair elections can be convened.3

U.S. relations with Venezuela, a major oil supplier, deteriorated during Chávez's rule, which undermined human rights, the separation of powers, and freedom of expression. U.S. and regional concerns have deepened as the Maduro government has manipulated democratic institutions; cracked down on the opposition, media, and civil society; engaged in drug trafficking and corruption; and refused most humanitarian aid. Efforts to hasten a return to democracy in Venezuela have failed thus far, but efforts to find a political solution to the crisis continue.4

This report provides an overview of the overlapping political, economic, and humanitarian crises in Venezuela, followed by an overview of U.S. policy toward Venezuela.

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS). |

Political Situation

Legacy of Hugo Chávez: 1999-20135

In December 1998, Hugo Chávez, a leftist populist representing a coalition of small parties, received 56% of the presidential vote (16% more than his closest rival). Chávez's commanding victory illustrated Venezuelans' rejection of the country's two traditional parties, Democratic Action (AD) and the Social Christian party (COPEI), which had dominated Venezuelan politics for the previous 40 years. Most observers attribute Chávez's rise to power to popular disillusionment with politicians who were judged to have squandered the country's oil wealth through poor management and corruption. Chavez's campaign promised constitutional reform; he asserted that the system in place allowed a small elite class to dominate Congress and waste revenues from the state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S. A. (PdVSA).

Venezuela had one of the most stable political systems in Latin America from 1958 until 1989. After that period, however, numerous economic and political challenges plagued the country. In 1989, then-President Carlos Andres Pérez (AD) initiated an austerity program that fueled riots in which several hundred people were killed. In 1992, two attempted military coups threatened the Pérez presidency, one led by Chávez, who at the time was a lieutenant colonel railing against corruption and poverty. Chávez served two years in prison for that failed coup attempt. In May 1993, the legislature dismissed Pérez from office for misusing public funds. The election of former President Rafael Caldera (1969-1974) as president in December 1993 brought a measure of political stability, but the government faced a severe banking crisis. A rapid decline in the world price of oil caused a recession beginning in 1998, which contributed to Chávez's landslide election.

Under Chávez, Venezuela adopted a new constitution (ratified by plebiscite in 1999), a new unicameral legislature, and a new name for the country—the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, named after the 19th century South American liberator Simón Bolívar. Buoyed by windfall profits from increases in the price of oil, the Chávez government expanded the state's role in the economy by asserting majority state control over foreign investments in the oil sector and nationalizing numerous private enterprises. Chávez's charisma, use of oil revenue to fund domestic social programs and provide subsidized oil to Cuba and other Central American and Caribbean countries, and willingness to oppose the United States captured global attention.6

After Chávez's death, his legacy has been debated. President Chávez established an array of social programs and services known as missions that helped reduce poverty by some 20% and improve literacy and access to health care.7 Some maintain that Chávez also empowered the poor by involving them in community councils and workers' cooperatives.8 Nevertheless, his presidency was "characterized by a dramatic concentration of power and open disregard for basic human rights guarantees," especially after his brief ouster from power in 2002.9 Declining oil production, combined with massive debt and high inflation, have shown the costs involved in Chávez's failure to save or invest past oil profits, tendency to take on debt and print money, and decision to fire thousands of PdVSA technocrats after an oil workers' strike in 2002-2003.10

Venezuela's 1999 constitution, amended in 2009, centralized power in the presidency and established five branches of government rather than the traditional three branches.11 Those branches include the presidency, a unicameral National Assembly, a Supreme Court, a National Electoral Council (CNE), and a "Citizen Power" branch (three entities that ensure that public officials at all levels adhere to the rule of law and that can investigate administrative corruption). The president is elected for six-year terms and can be reelected indefinitely; however, he or she also may be made subject to a recall referendum (a process that Chávez submitted to in 2004 and survived but Maduro cancelled in 2016). Chávez exerted influence over all the government branches, particularly after an outgoing legislature dominated by chavistas appointed pro-Chávez justices to control the Supreme Court in 2004 (a move that Maduro's allies would repeat in 2015).

In addition to voters having the power to remove a president through a recall referendum process, the National Assembly has the constitutional authority to act as a check on presidential power. The National Assembly consists of a unicameral Chamber of Deputies with 167 seats whose members serve for five years and may be reelected once. With a simple majority, the legislature can approve or reject the budget and the issuing of debt, remove ministers and the vice president from office, overturn enabling laws that give the president decree powers, and appoint the five members of the CNE (for seven-year terms) and the 32 members of the Supreme Court (for one 12-year term). With a two-thirds majority, the assembly can remove judges, submit laws directly to a popular referendum, and convene a constitutional assembly to revise the constitution.12

Maduro Government: 2013-201813

|

Nicolás Maduro A former trade unionist who served in Venezuela's legislature from 1998 until 2006, Nicolás Maduro held the position of National Assembly president from 2005 to 2006, when he was selected by President Chávez to serve as foreign minister. Maduro retained that position until mid-January 2013, concurrently serving as vice president beginning in October 2012, when President Chávez tapped him to serve in that position following his reelection. Maduro often was described as a staunch Chávez loyalist. Maduro's partner since 1992 is well-known Chávez supporter Cilia Flores, who served as the president of the National Assembly from 2006 to 2011; the two were married in July 2013. |

After Chávez's death in March 2013, Venezuela held presidential elections in April. Acting President Nicolás Maduro defeated Henrique Capriles of the Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD) of opposition parties by 1.5%. The opposition alleged significant irregularities and protested the outcome.

After his razor-thin victory, Maduro sought to consolidate his authority. Security forces and allied civilian groups violently suppressed protests and restricted freedom of speech and assembly. In 2014, 43 people died and 800 were injured in clashes between pro-government forces and student-led protesters concerned about rising crime. President Maduro imprisoned opposition figures, including Leopoldo López, head of the Popular Will (VP) party, who was sentenced to more than 13 years in prison for allegedly inciting violence. In February 2015, the government again cracked down.

In the December 2015 legislative elections, the MUD captured a two-thirds majority in Venezuela's National Assembly—a major setback for Maduro. The PSUV-aligned Supreme Court blocked three MUD deputies from taking office, which deprived the opposition of a two-thirds majority. From January 2016 through August 2017 (when the National Constituent Assembly discussed below voted to give itself legislative powers), the Supreme Court blocked laws and assumed the legislature's functions.

In 2016, opposition efforts focused on attempts to recall President Maduro in a national referendum. The government used delaying tactics to slow the process. In October 2016, the CNE suspended the recall effort after five state-level courts issued rulings alleging fraud in a signature collection drive that had amassed millions of signatures. In late 2016, most of the opposition (with the exception of Popular Will) agreed to talks with the government mediated by the Vatican; the former leaders of the Dominican Republic, Spain, and Panama; and the head of the Union of South American Nations. By December 2016, the opposition had left the talks due to a lack of progress on the part of the government in meeting its commitments.14

In 2017, the Maduro government continued to harass and arbitrarily detain opponents. In addition, President Maduro appointed a hardline vice president, Tareck el Aissami, former governor of the state of Aragua and designated by the United States as a drug kingpin. Popular protests, which were frequent between 2014 and 2016, had dissipated. In addition to restricting freedom of assembly, the government cracked down on media outlets and journalists.15

Despite these obstacles, the MUD became reenergized in response to the Supreme Court's March 2017 rulings to dissolve the legislature and assume all legislative functions. After domestic protests, a rebuke by then-Attorney General Luisa Ortega (a Chávez appointee), and an outcry from the international community, President Maduro urged the court to revise those rulings, and it complied. In April 2017, the government banned opposition leader and two-time presidential candidate Henrique Capriles from seeking office for 15 years, which fueled more protests.

From March to July 2017, the opposition conducted large, sustained protests against the government, calling for President Maduro to release political prisoners, respect the separation of powers, and hold an early presidential election. Clashes between security forces (backed by armed civilian militias) and protesters left more than 130 dead and hundreds injured (See "Human Rights" below).

Constituent Assembly Established. In May 2017, President Maduro announced that he would convene a constituent assembly to revise the constitution and scheduled July 30 elections to select delegates to that assembly. The Supreme Court ruled that Maduro could convoke the assembly without first holding a popular referendum (as the constitution requires). The opposition boycotted, arguing that the elections were unconstitutional; a position shared by then-Attorney General Luisa Ortega and international observers (including the United States). In an unofficial plebiscite convened in mid-July by the MUD, 98% of some 7.6 million Venezuelans cast votes rejecting the creation of a constituent assembly; the government ignored that vote. Despite an opposition boycott and protests, the government orchestrated the July 30, 2017, election of a 545-member National Constituent Assembly (ANC) to draft a new constitution.16

Many observers viewed the establishment of the ANC as an attempt by the ruling PSUV to ensure its continued control of the government even though many countries have refused to recognize its legitimacy. The ANC dismissed Attorney General Ortega, voted to approve its own mandate for two years, and declared itself superior to other branches of government. Ortega fled Venezuela in August 2017 and, since then, has spoken out against the Maduro government.17 The ANC also approved a decree allowing it, not the National Assembly, to pass legislation.

From mid-2017 to May 2018, President Maduro strengthened his control over the PSUV and gained the upper hand over the MUD despite international condemnation of his actions. In October 2017, the PSUV won 18 of 23 gubernatorial elections. Although fraud likely took place given the discrepancies between opinion polls and the election results, the opposition could not prove that it was widespread.18 There is evidence that the PSUV linked receipt of future government food assistance to votes for its candidates by placing food assistance card registration centers next to polling stations, a practice also used in subsequent elections.19 The MUD coalition initially rejected the election results, but four victorious MUD governors took their oaths of office in front of the ANC (rather than the National Assembly), a decision that fractured the coalition.

With the opposition in disarray, President Maduro and the ANC moved to consolidate power and blamed U.S. sanctions for the country's economic problems. Maduro fired and arrested the head of PdVSA and the oil minister for corruption. He appointed a general with no experience in the energy sector as oil minister and head of the company, further consolidating military control over the economy. The ANC approved a law to further restrict freedom of expression and assembly.

Although most opposition parties did not participate in municipal elections held in December 2017, a few, including A New Time (UNT), led by Manuel Rosales, and Progressive Advance, led by Henri Falcón, fielded candidates. The PSUV won more than 300 of 335 mayoralties. The CNE required parties that did not participate in those elections to re-register in order to run in the 2018 presidential contest, a requirement that many of them subsequently rejected.

May 2018 Elections and Aftermath. The Venezuelan constitution established that the country's presidential elections were to be held by December 2018. Although many prominent opposition politicians had been imprisoned (Leopoldo López, under house arrest), barred from seeking office (Henrique Capriles), or in exile (Antonio Ledezma20) by late 2017, some MUD leaders sought to unseat Maduro through elections. Those leaders negotiated with the PSUV to try to obtain guarantees, such as a reconstituted CNE and international observers, to help ensure the elections would be as free and fair as possible. In January 2018, the ANC ignored those negotiations and called for elections to be moved up from December to May 2018, violating a constitutional requirement that elections be called with at least six months anticipation.21 The MUD declared an election boycott, but Henri Falcón, former governor of Lara, broke with the coalition to run.

Venezuela's presidential election proved to be minimally competitive and took place within a climate of state repression. President Maduro and the PSUV's control over the CNE, courts, and constituent assembly weakened Falcón's ability to campaign. State media promoted government propaganda. There were no internationally accredited election monitors. The government coerced its workers to vote and placed food assistance card distribution centers next to polling stations.

The CNE reported that Maduro received 67.7% of the votes, followed by Falcón (21%) and Javier Bertucci, a little-known evangelical minister (10.8%). Voter turnout was much lower in 2018 (46%) than in 2013 (80%), perhaps due to the MUD's boycott. After independent monitors reported widespread fraud, Falcón and Bertucci called for new elections to be held.22

Since the May 2018 election, President Maduro has faced mounting economic problems, coup attempts, and increasing international isolation. His government has released some political prisoners, including U.S. citizen Joshua Holt, former Mayor Daniel Ceballos, opposition legislators (Gilber Caro and Renzo Prieto), and, in October 2018, former student leader Lorent Saleh. He reshuffled his Cabinet to establish Delcy Rodriguez, former head of the ANC and former foreign minister, as executive vice president in June 2018 and made additional changes within the judiciary and the intelligence services to increase his control.

With the opposition relatively weak and divided, Maduro focused on quashing coup plots and dissent within the military. His government arrested those perceived as threats, including military officers, an opposition legislator accused of involvement in an August 2018 alleged assassination attempt against Maduro, and a German journalist accused of being a spy.23 Foro Penal and Human Rights Watch have documented several cases in which those accused of plotting coups were subjected to "beatings, asphyxiation and electric shocks" by the intelligence services.24 The October 2018 death in custody of Fernando Albán, an opposition politician, provoked domestic protests and international concern.25

Maduro's Second Term Deemed Illegitimate; Interim Government Formed

On January 10, 2019, Maduro began a second term after winning reelection on May 20, 2018, in a contest deemed illegitimate by the opposition-controlled National Assembly and most of the international community. The United States, the European Union (EU), the Group of Seven (G-7), and most Western Hemisphere countries do not recognize the legitimacy of his mandate. They view the National Assembly as Venezuela's only democratic institution.

Under the leadership of Juan Guaidó, a 35-year-old industrial engineer from the VP party who was elected president of the National Assembly on January 5, 2019, the opposition has been reenergized. In mid-January, Guaidó announced he was willing to serve as interim president until new presidential elections are held. Buoyed by the massive turnout for protests he called for, Guaidó took the oath of office on January 23, 2019. Since then, the National Assembly has enacted resolutions declaring Maduro's mandate illegitimate, establishing a framework for a transition government, drafting a proposal to offer amnesty for officials who support the transition, and creating a strategy for receiving humanitarian assistance.

Guaidó and his supporters have organized two high-profile efforts to encourage security (military and police) forces to abandon Maduro, neither of which has succeeded.26 On February 23, they sought to bring emergency supplies into the country that had been positioned on the Colombia- and Brazil-Venezuela borders by the United States and other donors. Venezuelan national guard troops and armed civilian militias (colectivos) loyal to Maduro killed seven individuals and injured hundreds as they prevented the aid convoys from crossing the border.27 The rest of the military did not attack civilians. While that aid remains blocked, U.N. agencies are ramping up their efforts in Venezuela, and both Guaidó and Maduro agreed in late March to allow the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) to begin providing assistance in Venezuela (see "International Response Inside Venezuela" below).28

By April 2019, more than 1,000 Venezuelan security forces (mostly from the national guard and police) had defected into Colombia. The Colombian military has disarmed and placed them in hotels near the border along with their family members.29 In May 2019, Colombia's migration agency signed an agreement with the interim government of Venezuela to grant security forces that have defected from Maduro temporary legal status to work and receive assistance from the Colombian government.30 Prospects for those who have defected is reportedly difficult, as they have become among the more than 1.2 million Venezuelans in Colombia.31

On April 30, 2019, Guaidó and Leopoldo López, head of the VP party who had been released from house arrest by pro-Guaidó military officials, called for a civil-military rebellion against Maduro. National guard and militias loyal to Maduro violently put down pro-Guaidó supporters and attacked journalists. Social media accounts and independent media were blocked.32 U.S. officials asserted that top Maduro officials, including the head of the Supreme Court and the defense minister, had pledged to support the uprising but changed their minds.33 As the day ended, López and other opposition lawmakers sought refuge in various foreign embassies.

Guaidó and his allies continue to hope that sustained protests and international pressure will lead to military defections that will compel Maduro to leave office and allow elections to be held. Nevertheless, they have also sent envoys to Norway for talks on a political solution to the crisis.34 Maduro's harassment of the National Assembly and the Maduro-aligned Supreme Court's efforts to arrest and prosecute lawmakers involved in the uprising could derail those efforts.

Many observers regard the military's participation as essential for the opposition's transition plan to work. Aside from the former head of the national intelligence agency (General Manuel Christopher Figuera), who supported the uprising on April 30, the military high command remains loyal to Maduro. Top military leaders have enriched themselves through corruption, drug trafficking, and other illicit industries (see "Organized Crime-Related Issues" below).35 This illicit income, they argue, has blunted the impact of U.S. sanctions on Maduro's closest allies.36 Some military leaders may fear that they could face prosecution for human rights abuses under a new government, even though the opposition has proposed amnesty for those who join their side. The U.S. government has also said that it may remove sanctions on officials who abandon Maduro and side with Guaidó (as they did with General Figuera), but that process could be more difficult, depending upon the individual and type of sanctions involved.37

Human Rights

Human rights organizations and U.S. officials have expressed concerns for more than a decade about the deterioration of democratic institutions and threats to freedom of speech and press in Venezuela.38 Human rights conditions in Venezuela have deteriorated even more under President Maduro than under former President Chávez. Abuses have increased, as security forces and allied armed civilian militias (colectivos) have been deployed to violently quash protests. In August 2017, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNOCHR) issued a report on human rights violations perpetrated by the Venezuelan security forces against protestors earlier that year. According to the report, credible and consistent accounts indicated that "security forces systematically used excessive force to deter demonstrations, crush dissent, and instill fear."39 The U.N. report maintained that many of those detained were subject to cruel, degrading treatment and that in several cases, the ill treatment amounted to torture.

In June 2018, UNOCHR issued another report documenting abuses committed by units involved in crime fighting, the scale of the health and food crisis, and the continued impunity in cases involving security officers who allegedly killed people during the protests.40 Selected human rights reports from 2018 to 2019 include the following:

- In June 2018, PROVEA, one of Venezuela's leading human rights organizations, asserted that 2017 was the worst year for human rights in Venezuela since the report was first published in 1989. In addition to violating political and civil rights, PROVEA denounces the Maduro government's failure to address the country's humanitarian crisis, citing its "official indolence" as causing increasing deaths and massive emigration.41

- In May 2018, an independent panel of human rights experts added a legal assessment to a report containing information and witness testimonies gathered by the Organization of American States (OAS) recommending that the International Criminal Court (ICC) investigate credible reports that the Venezuelan government committed crimes against humanity.42

- In February 2019, the Venezuelan Human Rights group Foro Penal documented seven deaths, 107 arbitrary detentions, and 58 bullet injuries that resulted from the use of force by state security forces and colectivos that blocked aid from entering the country on February 22-23, 2019.43

- In March 2019, the U.S. State Department's Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 2018 cited "extrajudicial killings by security forces, including colectivos; torture by security forces; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; and political prisoners" as the most serious human rights abuses in Venezuela. According to the report, the government did not investigate officials alleged to have committed abuses amidst widespread impunity.44

Analysts predict increasing repression, as Maduro has called for the arrest of Leopoldo López and opposition lawmakers involved in the April 30 uprising. The Supreme Court has stripped several lawmakers' immunity from prosecution, increasing the likelihood that they may be arrested and possibly tortured if they do not seek protection in a foreign embassy or go into exile. Maduro's intelligence police is currently holding and reportedly torturing Juan Requesens (a legislator detained in August 2018), Roberto Marrero (Guaidó's chief of staff detained in March 2019), and Edgar Zambrano (the vice president of the National Assembly detained May 9).45 Some fear that Guaidó himself could face arrest or exile.

For other sources on human rights in Venezuela, see Appendix B.

Investigations into Human Rights Abuses. In September 2017, several countries urged the U.N. Human Rights Council to support the High Commissioner's call for an international investigation into the abuses described in the U.N.'s August 2017 report on Venezuela.46 In June 2018, the High Commissioner for Human Rights urged the U.N. Human Rights Council to launch a commission of inquiry to investigate the abuses it documented in that and a follow-up report. It referred the report to the prosecutor of the ICC. On September 26, 2018, the U.N. Human Rights Council adopted a resolution on Venezuela expressing "its deepest concern" about the serious human rights violations described in the June 2018 report, calling upon the Venezuelan government to accept humanitarian assistance and requiring a UNOCHR investigation on the situation in Venezuela to be presented in 2019. In March 2019, a technical team from UNOCHR visited Venezuela, possibly paving the way for a visit by High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet.

In addition to the UNOCHR, former Venezuelan officials, the OAS, and neighboring countries have asked the ICC to investigate serious human rights violations committed by the Maduro government; the ICC prosecutor opened a preliminary investigation in February 2018.47 In November 2017, former Attorney General Luisa Ortega presented a dossier of evidence to the ICC that the police and military may have committed more than 1,800 extrajudicial killings as of June 2017. In the dossier, Ortega urged the ICC to charge Maduro and several officials in his Cabinet with serious human rights abuses. An exiled judge appointed by the National Assembly to serve on the "parallel" supreme court of justice also accused senior Maduro officials of systemic human rights abuses before the ICC. On September 26, 2018, the governments of Argentina, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Paraguay, and Peru requested an investigation of Venezuela's actions by the ICC—the first time fellow states party to the Rome Statute asked for an investigation into the situation of another treaty member.

Economic Crisis48

For decades, Venezuela was one of South America's most prosperous countries. Venezuela has the world's largest proven reserves of oil, and its economy is built on oil. (See also "Energy Sector Concerns and U.S. Economic Sanctions" below.) Oil traditionally has accounted for more than 90% of Venezuelan exports, and oil sales have funded the government budget. Venezuela benefited from the boom in oil prices during the 2000s. President Chávez used the oil windfall to spend heavily on social programs and expand subsidies for food and energy, and government debt more than doubled as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) between 2000 and 2012.49 Chávez also used oil to expand influence abroad through PetroCaribe, a program that allowed Caribbean Basin countries to purchase oil at below-market prices.

Although substantial government outlays on social programs helped Chávez curry political favor and reduce poverty, economic mismanagement had long-term consequences. Chávez moved the economy in a less market-oriented direction, with widespread expropriations and nationalizations, as well as currency and price controls. These policies discouraged foreign investment and created market distortions. Government spending was not directed toward investment to increase economic productivity or diversify the economy from its reliance on oil. Corruption proliferated.

When Nicolás Maduro took office in 2013, he inherited economic policies reliant on proceeds from oil exports. When world oil prices crashed by nearly 50% in 2014, the Maduro government was ill-equipped to soften the blow. The fall in oil prices strained public finances. Instead of adjusting fiscal policies through tax increases and spending cuts, the Maduro government tried to address its growing budget deficit by printing money, which led to inflation. The government also tried to curb inflation through price controls, although these controls were largely ineffective in restricting prices, as supplies dried up and transactions moved to the black market.50

Meanwhile, the government continued to face a substantial debt burden, with debt owed to private bondholders, China, Russia, multilateral lenders, importers, and service companies in the oil industry. Initially, the government tried to service its debt, fearing legal challenges from bondholders. To service its debt, it cut imports, including of food and medicine, among other measures. By late 2017, the government had largely stopped paying its bondholders, and Maduro announced plans to restructure its debt with private creditors. It also restructured its debt with Russia in 2017.51 The Trump Administration has increased economic pressure on the Maduro government through sanctions. (See "U.S. Sanctions on Venezuela.") For example, in August 2017, it restricted Venezuela's ability to access U.S. financial markets, which exacerbated the government's fiscal situation, and in January 2019, it imposed new restrictions on Venezuela's oil sector.

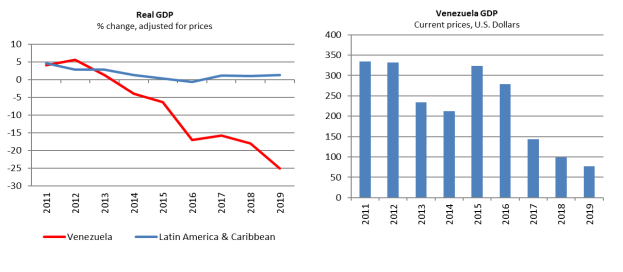

Over the past several years, Venezuela's economy has collapsed, and it is difficult to overstate the extent of its challenges. According to some economists, it is the single largest economic collapse outside of war in at least 45 years.52 According to forecasts by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Venezuela's economy in 2019 will contract for the sixth year in a row (Figure 2).53 The IMF projects that Venezuela's gross domestic product in U.S. dollars fell from $331 billion in 2012 to $98 billion in 2018 and will fall again to $76 billion in 2019 (Figure 2).

|

|

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook, April 2019. Notes: 2019 data are forecasts. |

Hyperinflation has devastated the economy. The Maduro government rapidly expanded the money supply to finance budget deficits, which led to one of the worst cases of hyperinflation in history, comparable to Germany in 1923 or Zimbabwe in the late 2000s.54 The IMF forecasts that inflation in Venezuela will reach 10 million percent in 2019.55 Hyperinflation, as well as low foreign exchange reserves, which make it difficult for Venezuela to import goods and services, has created shortages of critical supplies (including food and medicine), leading to a humanitarian disaster and fueling massive migration (see "Humanitarian Situation" below).

Despite pledges to restructure the country's debt, the government has made no progress in negotiations with private creditors and the country remains in default on most of its sizeable debt. The government has continued payments on a few select debts, including loans from Russia, a geopolitically and financially important supporter for the Maduro government, and some bonds held by private creditors that, if defaulted on, could result in legal challenges by investors and seizure of U.S. refiner Citgo (owned by PdVSA). Meanwhile, the government continues to run large budget deficits, forecast at 30% of GDP in 2018 and 2019, amid high debt levels (estimated to reach 214% of GDP in 2019).56 By one measure, debt relative to exports, Venezuela is the world's most heavily indebted country.57

In general, the government has been slow to address the economic crisis or acknowledge the government's role in creating it. Instead, the government has largely blamed the country's struggles on a foreign "economic war," a thinly veiled reference to U.S. sanctions.58 In February 2018, as a way to raise new funds, the cash-strapped government launched a new digital currency, the "petro," backed by oil and other commodities, although there are serious questions about the petro's operational viability.59 In August 2018, the government acknowledged, for the first time, its role in creating hyperinflation and announced a new set of policies for addressing the economic crisis, such as introducing a new "sovereign bolívar," which removed five zeros from the previous currency (the bolívar); cutting the government budget deficit from 30% in 2018 to zero; speeding up tax collection; and increasing the minimum salary by more than 3,000%.60 However, the government has been slow to enact even these modest reforms, and Maduro has offered few new proposals since starting his second term.61

Venezuela's economic situation has become more difficult following the rollout of new U.S. oil sanctions in January 2019, although it has worked with Russia, Turkey, and other countries to mitigate the sanctions' impact.62 The Venezuelan government has turned to selling gold reserves in a desperate attempt to raise funds, with nearly $800 million sold to Turkey in 2018.63 As the United States has since sanctioned Venezuela's central bank and state-run gold mining company, analysts maintain that Maduro will likely increase illicit gold shipments sent through neighboring countries, a key revenue stream for the military.64

Venezuela's economic crisis has been ongoing for a number of years, and the outlook is bleak. There is neither a clear nor a quick resolution on the horizon, particularly given the concurrent political crisis. The government's policy responses to the economic crisis have been widely criticized as inadequate. The government appears loathe to adopt policies widely viewed by economists as necessary to restoring the economy: removing price controls, creating an independent central bank, entering an IMF program that could unlock broader international assistance, and restructuring its debt with private bondholders.

The Maduro government is particularly resistant to assistance from the IMF, which would be a key component of any multi-donor international financial assistance package. Venezuela has not allowed the IMF to conduct routine surveillance of its economy since 2004, and the IMF has found the government in violation of its commitments as an IMF member. Although the Venezuelan government provided it with some economic data as required by all IMF members in late 2018, it has hardly been a turning point in the Maduro government's willingness to engage with the international organization. Some analysts believe major change in Venezuela's overall economic strategy will come only if and when there is a change in government. Even then, analysts have projected it could take several years to address, including what is expected to be the most complex sovereign debt restructuring in history and an international financial assistance package of $100 billion to help the country's economy to recover.65

Humanitarian Situation66

Before the political upheaval in Venezuela began in January 2019, Venezuelans were already facing a humanitarian crisis due to a lack of food, medicine, and access to social services. Political persecution, hyperinflation, loss of income, and oppressive poverty also contributed to a dire situation. According to household surveys, the percentage of Venezuelans living in poverty increased from 48.4% in 2014 to 87% in 2017.67 U.N. officials estimate that approximately 7 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance, with pregnant and nursing women, those with chronic illnesses, indigenous people, migrants, children under five, and people with disabilities particularly in need.68 Successive electrical blackouts in March 2019 made conditions worse inside Venezuela, limiting people's access to power and clean water and further contributing to health risks. While power has been restored in many parts of the country, rationing in many states continues to take place.69

As of April 2019, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimated that approximately 3.7 million Venezuelans (roughly 12% of the population) had left the country (see Figure 3). Of those, most (an estimated 3 million Venezuelans) remained in Latin America and the Caribbean, including in Colombia (1.2 million), Peru (728,000), Chile (288,000), Ecuador (221,000), Argentina (130,000), Brazil (96,000), and Panama (94,000).70 UNHCR and IOM estimate that by the end of 2019, the number of Venezuelan refugees and migrants could reach over 5.3 million.71 Although UNHCR does not consider most Venezuelans to be refugees, it asserts that a significant number need humanitarian assistance, international protection, and opportunities to regularize their status.

|

Figure 3. Venezuelan Migrants and Asylum Seekers: Flows to the Region and Beyond |

|

|

Source: UNHCR. |

The crisis in Venezuela is affecting the entire region. Neighboring countries, particularly Colombia, are straining to absorb arrivals often malnourished and in poor health.72 The spread of previously eradicated diseases, such as measles, is also a major concern.73 Responses to the Venezuelan arrivals vary by country and continue to evolve with events on the ground. Humanitarian experts are most concerned about the roughly 60% of Venezuelans in neighboring countries who lack identification documents, which makes them vulnerable to arrest and deportation by governments and to abuse by criminal groups, including human trafficking.74

Venezuela's exodus is an unprecedented displacement crisis for the Western Hemisphere, which has in place some of the highest protection standards in the world for displaced and vulnerable persons. Countries in the region are under pressure to examine their respective migration and asylum policies and to address, as a region, the legal status of Venezuelans who have fled their country. It remains to be seen how events unfolding inside Venezuela will continue to the impact the ongoing humanitarian situation and response.

International Response Inside Venezuela

In 2018, Maduro publicly rejected offers of international aid, although some humanitarian assistance was provided.75 Since then, U.N. humanitarian entities and partners have made progress in scaling up their humanitarian and protection activities. The number of U.N. staff in the country has doubled since 2017, and the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) has set up regional hubs in the country. The Cooperation and Assistance Coordination Team, led by the U.N. Resident Coordinator, was established in February 2019 to facilitate humanitarian coordination in Venezuela. A needs overview for Venezuela was completed in March and indicated significant humanitarian needs exist across sectors. Based on this data, UNOCHA and other humanitarian partners are developing a Humanitarian Response Plan for Venezuela, which will focus on six sectors and two sub-sectors: health; food security and agriculture; nutrition; water, sanitation, and hygiene; protection (including child protection and gender-based violence); and education.76

In addition, on March 29, 2019, IFRC announced plans to scale up humanitarian activities inside Venezuela in coordination with the Venezuelan Red Cross and with the agreement of both the interim government and Maduro.77 On April 11, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which has been present in Venezuela since 1966, announced an expansion of its work on four pressing humanitarian issues: migration, health, water and sanitation, and detention.78

International Humanitarian Response in the Region

The U.N. Secretary-General appointed UNHCR and IOM to coordinate the international response to the needs of displaced Venezuelans and host communities in the region, which includes governments, U.N. entities, nongovernmental organizations (national and international), the Red Cross Movement, faith-based organizations, and civil society in the region. The U.S. government is also providing humanitarian assistance and helping to coordinate regional response efforts. (See "U.S. Humanitarian and Related Assistance," below.) Former Guatemalan Vice President Eduardo Stein, the U.N. Joint Special Representative for Venezuelan Refugees and Migrants, is charged with promoting dialogue and consensus in the region and beyond on the humanitarian response.

In mid-December 2018, UNHCR and IOM launched the Regional Refugee and Migrant Response Plan, which is the first of its kind in the Americas: an operational and coordination strategy and an appeal for $738 million in funding to support over 2 million Venezuelans in the region and half a million people in host communities.79 According to the Financial Tracking Service, as of May 24, 2019, the appeal was 20.7% funded.80 Protection and assistance needs are significant for arrivals and host communities. Services provided vary by country but include support for reception centers and options for shelter; emergency relief items, such as emergency food assistance, safe drinking water, and hygiene supplies; legal assistance with asylum applications and other matters; protection from violence and exploitation; and the creation of temporary work programs and education opportunities.

Foreign Involvement in Venezuela's Political Crisis81

The international community remains divided over how to respond to the political crisis in Venezuela. One group of countries supports the Guaidó government, another supports Maduro, and a third group of countries—including Mexico, Norway, Uruguay, and some Caribbean nations—has remained neutral in the crisis.

These divisions have thus far stymied action by the U.N. and the OAS to help facilitate a political solution to Venezuela's crisis. Within the U.N. Security Council, Russia and (to a lesser extent) China support Maduro. The United States, France, and the United Kingdom (UK) support Guiadó. At the OAS, recent resolutions have amassed enough votes (19 of 34 member states) to declare Maduro's 2018 reelection illegitimate.82 The OAS remains divided, however, over what role it should play in hastening a return to democracy in Venezuela. Countries in the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), many of which used to receive subsidized oil from Venezuela, have been particularly reluctant to intervene in Venezuela's internal affairs.

The United States and 53 other countries have formally recognized the interim government of Juan Guaidó. These countries include most members of the EU, Canada, 14 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, Australia, Israel, Japan, and South Korea, among others. Some of those countries have undertaken initiatives to increase pressure on Maduro to leave office. Canada, the EU, Panama, and Switzerland have placed targeted sanctions on Maduro officials and have frozen reserves formerly controlled by the Maduro government and/or blocked suspicious financial transactions involving Maduro.83 Other countries have withdrawn their diplomats from Caracas and/or accepted the credentials of diplomats representing the Guaidó government.

While they back a transition leading to Maduro leaving power, the EU and many Western Hemisphere countries (including Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Brazil, and Peru) have opposed the prospect of U.S. military intervention in Venezuela.84 They and others fear the regional implications that instability and violence spawned by the use of military force could cause, particularly given the armed civilian militias and illegally armed groups in Venezuela, many of which are not under Maduro's control.85 Among countries that back a political transition in Venezuela that involves Maduro leaving office, two groups have emerged: the Lima Group and the International Contact Group.

Lima Group

On August 8, 2017, 12 Western Hemisphere countries signed the Lima Accord, a document rejecting what it described as the rupture of democracy and systemic human rights violations in Venezuela.86 The signatory countries included Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, and Peru. In 2018, Guyana and St. Lucia joined the Lima Group, which did not recognize Maduro's May 2018 reelection.

On January 4, 2019, 13 members of the Lima Group signed a declaration urging President Maduro not to assume power on January 10, 2019.87 The countries resolved to reassess their level of diplomatic engagement with Venezuela, implement travel bans or sanctions on Maduro officials (as Canada and Panama have), suspend military cooperation with Venezuela, and urge others in the international community to take similar actions. Under leftist President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Mexico is no longer participating in the Lima Group. El Salvador is likely to join the Lima Group after President-elect Nayib Bukele's June 1 inauguration.

The group has denounced human rights violations by the Maduro government and urged Venezuelan armed forces to demonstrate their loyalty to Guaidó but opposed U.S. or regional military intervention in the crisis. On May 3, 2019, the Lima Group issued a declaration signed by 12 countries (excluding St. Lucia and Guyana but including the interim government of Venezuela) asking the ICG to meet to coordinate efforts and pledging to seek Cuba's help in resolving Venezuela's crisis.88 Representatives from the Lima Group and the ICG met at the ministerial level on June 3.

International Contact Group (ICG)

The EU-backed ICG—composed of Costa Rica, Ecuador, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Uruguay—first convened on February 7, 2019. The group aimed to "establish necessary guarantees for a credible electoral process, within the earliest time frame possible" and to hasten the delivery of humanitarian aid into Venezuela.89 U.S. officials have expressed skepticism at the proposal, noting that Maduro has used past attempts at dialogue (brokered by the Vatican and others) as a delaying tactic. ICG supporters maintain that the "necessary guarantees" include naming a new electoral council, releasing political prisoners, and ending all bans on political parties and candidates.90

Since February, the ICG has met twice, most recently on May 6-7 in Costa Rica. At that meeting, also attended by Chile from the Lima Group and representatives from CARICOM and the Vatican, the ICG decided to send a political mission to Caracas (which they did) and to work with the Lima Group to hasten a political solution to the crisis.91 The ICG backs the dialogue process (discussed below) that has gotten underway in Norway.92 China has pledged to work with the EU and others for a political settlement to the Venezuela crisis.93

Cuba, Russia, and China

Within Latin America, Cuba, Nicaragua, Bolivia, and a few other countries have provided various kinds of support to Maduro and have sought to block anti-Maduro actions within international organizations. Among Maduro's supporters in Latin America, the most significant is Cuba. Cuba's close relationship with Venezuela was solidified in 2000, when the countries signed an agreement for Venezuela to provide Cuba oil in exchange for technical assistance and other services. Estimates of the number of Cuban personnel in Venezuela vary, but a 2014 study estimated that there were 40,000, 75% of whom were health care workers.94 It is unclear how many of those professionals have stayed in the country, but Cuban intelligence officers have reportedly helped the Maduro government identify and disrupt coup plots, a role that the Trump Administration has frequently denounced.95 Although Cuba has imported oil from other sources to make up for dwindling Venezuelan supplies, the Maduro government remains committed to providing what it can, even if it has to be purchased from other sources.96 In April 2019, the Department of the Treasury moved to shut down that flow (and Cuban support for Maduro) by sanctioning 44 vessels and six shipping companies involved in transporting Venezuelan oil, including five companies that have transported Venezuelan oil to Cuba (see "U.S. Sanctions on Venezuela").97

Russia has remained a strong ally of the Maduro government. 98 Russia's trade relations with Venezuela are currently not significant. However, Venezuela was a major market for Russian arms between 2006 and 2013, with an estimated $4 billion in sales (mostly on credit).99 Venezuela reportedly had more than 5,000 Russian-made surface-to-air missiles as of 2017, raising concern about the potential for them being stolen or sold to criminal or terrorist groups.100 Russian state oil company Rosneft has also invested billions of dollars in Venezuela.101 Russia's 2017 decision to allow Venezuela to restructure $3 billion in debt provided much-needed financial relief to the Maduro government.102

Russia has called for the political crisis in Venezuela to be resolved peacefully and without outside interference. It reportedly views support for Maduro as a way to simultaneously oppose U.S. efforts at "regime change" and maintain influence in a region close to the United States.103 In December 2018, Maduro visited Russia after which news reports suggested that Rosneft had lent PdVSA $6.5 billion, partly as a prepayment for crude oil.104 That month, Russia also sent two nuclear-capable bombers to Venezuela to conduct joint exercises (the third such deployment since 2008).105 The Russian government congratulated Maduro on his inauguration and has blocked U.N. Security Council action against Maduro. In March 2019, Russia sent an estimated 100 military personnel and associated equipment to Venezuela, a move the United States denounced.106

While Russia has both economic and geo-strategic interests in Venezuela and opposes what it views as U.S.-backed efforts at "regime change," China's interest in Venezuela is primarily economic, and the Chinese government has reportedly been in contact with the Guaidó government.107 From 2007 through 2016, China provided some $62.2 billion in financing to Venezuela.108 The funds have mostly been for infrastructure and other economic development projects, but China has also provided loans for military equipment to be repaid by oil deliveries.109 Although the Chinese government has been patient when Venezuela has fallen behind on its oil deliveries, Beijing reportedly stopped providing new loans to Venezuela in fall 2016.110 As previously stated, China, unlike Russia, has signaled a willingness to support dialogue efforts that could result in the convening of new presidential elections in Venezuela.111

Dialogue Facilitated by Norway

On May 29, 2019, the Norwegian government, which has remained neutral in the Venezuela crisis, announced that both Maduro and Guaidó representatives had demonstrated a "willingness" to continue trying to reach a political agreement to respond to the country's multifaceted crisis.112 At least two rounds of exploratory talks have been held that have reportedly focused on the convening of new presidential elections with a new electoral authority.113 Guaidó's supporters argue that Maduro should step down and allow a transitional government to organize those elections, a proposal he has thus far refused.114 Other issues reportedly include political prisoners, the degree to which chavistas can participate in a transition government, humanitarian aid, disarming the colectivos, and how to balance the need for justice for past abuses with a potential amnesty law for those who back a political transition.115

U.S. Policy

The United States has historically had close relations with Venezuela, a major U.S. foreign oil supplier, but friction in relations increased under the Chávez government and has intensified under the Maduro government. For more than a decade, U.S. policymakers have had concerns about the deterioration of human rights and democratic conditions in Venezuela and the lack of bilateral cooperation on counternarcotics and counterterrorism efforts. During this time, Congress has provided funding to support democratic civil society in Venezuela. As Maduro has become increasingly authoritarian, the Obama and Trump Administrations have increasingly turned to sanctions, first targeted on specific officials and then aimed at broader portions of the Venezuelan economy, to encourage a return to democracy in the country. More recently, U.S. humanitarian assistance has supported Venezuelans who have fled to neighboring countries.

Since January 2019, the United States has coordinated its efforts with Guaidó. On January 10, 2019, the U.S. State Department condemned Maduro's "illegitimate usurpation of power." President Trump recognized Guaidó as interim president of Venezuela on January 23 and has encouraged other governments to do the same. The Administration has imposed targeted sanctions (visa bans and sanctions blocking access to assets) on additional Maduro officials and their families, blocked the Maduro government's access to revenue from Venezuela's state oil company, and employed broader sanctions aimed at choking off other sources of revenue. In response to the interim government's request, the Administration has pre-positioned emergency assistance for Venezuelans on the country's borders. President Trump and other Administration officials have repeatedly asserted that "all options are on the table" to address the Venezuela situation, including the use of U.S. military force.116 Most analysts agree that a U.S. military intervention is unlikely. Some Members of Congress have expressed serious concerns about any U.S. military action in Venezuela, and such a policy is opposed by virtually all U.S. allies in the region.117

U.S. Sanctions on Venezuela118

The United States has increasingly employed sanctions as a policy tool in response to activities of the Venezuelan government and Venezuelan individuals. As the political and economic crisis in Venezuela has deepened, the Trump Administration has significantly expanded sanctions on Venezuela, relying on both existing sanctions and new executive orders. In particular, recent U.S. sanctions on Venezuela have targeted specific Venezuelan officials, the Maduro government's access to the U.S. financial system, and Venezuela's oil and gold sectors, which are key sectors and sources of financing for the Maduro government. The Trump Administration has cited a number of serious concerns about the Maduro government in expanding sanctions including, among others, human rights abuses, usurpation of power from the democratically elected National Assembly, rampant public corruption, degradation of Venezuela's infrastructure and environment through economic mismanagement and confiscatory mining and industrial practices, and its role in creating a regional migration crisis by neglecting the needs of the Venezuelan people.119

Targeted Sanctions on Venezuelan Officials

The Trump Administration has used existing authorities to sanction a number of Venezuelan officials. In particular, the Trump Administration has sanctioned 75 Venezuelan government and military officials pursuant to E.O. 13692, issued by President Obama in March 2015 to implement the Venezuela Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-278).120 Among its provisions, the law requires the President to impose sanctions (asset blocking and visa restrictions) against those whom the President determines are responsible for significant acts of violence or serious human rights abuses associated with protests in February 2014 or, more broadly, against anyone who has directed or ordered the arrest or prosecution of a person primarily because of the person's legitimate exercise of freedom of expression or assembly. In 2016, Congress extended the 2014 act through 2019 in P.L. 114-194.

Under the Obama Administration, the Department of the Treasury froze the assets of seven Venezuelans—six members of Venezuela's security forces and a prosecutor involved in repressing antigovernment protesters—pursuant to E.O. 13692. Under the Trump Administration, the Department of the Treasury designated for sanctions an additional 75 Venezuelan government and military officials. These officials include Maduro and his wife, Cecilia Flores; Executive Vice President Delcy Rodriguez; PSUV First Vice President Diosdado Cabello; eight Supreme Court members; the leaders of Venezuela's army, national guard, and national police; four state governors; the director of the Central Bank of Venezuela; and the foreign minister.

The Trump Administration has also blocked the assets and travel of two high-ranking officials in Venezuela, including then-Vice President Tareck el Aissami and Pedro Luis Martin (a former senior intelligence official) pursuant to Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act (P.L. 106-120, Title VIII; 21 U.S.C. 1901 et seq.). Including those individuals, the Department of the Treasury has now imposed economic sanctions on at least 22 individuals with connections to Venezuela and 27 companies by designating them as Specially Designated Narcotics Traffickers pursuant to the Kingpin Act.

For a discussion on terrorism-related sanctions related to Venezuela, see "Terrorism" section below.

Sanctions Restricting Venezuela's Access to U.S. Financial Markets

Starting in 2017, President Trump has sought to cut off U.S. sources of financing for the Venezuelan government. In August 2017, President Trump issued E.O. 13808 to prohibit access to U.S. financial markets by the Venezuelan government, including PdVSA, with certain exceptions to minimize the impact on the Venezuelan people and U.S. economic interests.121 The sanctions restrict the Venezuelan government's access to U.S. debt and equity markets, traditionally an important source of capital for the government and PdVSA.

In 2018, the Trump Administration issued two additional executive orders to further tighten Venezuela's access to U.S. currency. E.O. 13827, issued in March 2018, prohibits U.S. investors from purchasing or transacting in Venezuela's new digital currency, the petro. This is designed to help the government raise funds and circumvent U.S. sanctions.122 E.O. 13835, issued in May 2018, prohibits U.S. investors from buying debt or accounts receivable with the Venezuelan government, including PdVSA. This is devised to close off an "avenue for corruption" used by Venezuelan government officials to enrich themselves.123

Sanctions on Venezuela's Oil and Gold Sectors

Beginning in late 2018, the Trump Administration has rolled out a series of new sanctions focused on Venezuela's oil, gold, financial, defense, and security sectors. In November 2018, President Trump issued E.O. 13850, which blocks the assets of, and prohibits transactions with, those entities operating in Venezuela's gold sector (or any other sector of the economy as determined in the future by the Treasury Secretary) or responsible for or complicit in transactions involving deceptive practices or corruption in the Venezuelan government.124 Three subsequent determinations issued by Secretary of the Treasury Mnuchin expanded the reach of E.O. 13850 to include the other sectors.125

Over subsequent months, a number of individuals and entities have been sanctioned pursuant to E.O. 13850, including five individuals involved in a corruption scheme involving Venezuela's currency exchange practices, PdVSA (with general licenses issued by Office of Foreign Assets Control [OFAC] to allow certain transactions and activities related to PdVSA and its subsidiaries), the Moscow-based Evrofinance Mosnarbank (jointly owned by Russia and Venezuela) for helping PdVSA funnel its cash flow from oil sales, Venezuela's state-owned gold sector company—Minerven—for using illicit gold operations to help Maduro financially, state-affiliated Venezuelan Economic and Social Development Bank and five of its subsidiaries that the Maduro government uses to move money outside of Venezuela, 44 vessels and six shipping companies involved in transporting Venezuelan oil, and Venezuela's central bank in order to cut off its access to U.S. currency and limit its ability to conduct international financial transactions.

Debate over the Efficacy of U.S. Sanctions on Venezuela

The Trump Administration has significantly ratcheted up sanctions on Venezuela, hitting key targets including Maduro himself, the state-owned oil and gold companies, and the Venezuelan central bank, among others. The Administration has also started targeting foreign firms doing business with Venezuela ("secondary sanctions") in its sanctions on foreign shipping companies transporting Venezuelan oil. At the same time, the Administration is starting to demonstrate some flexibility in its sanctions policy with the lifting of sanctions against the former head of Venezuela's intelligence service, General Manuel Cristopher Figuera, in May 2019 after he broke ranks with Maduro. To date, the Administration to date has stopped short of more aggressive sanctions, including on companies in other countries that purchase Venezuelan oil, although such sanctions have reportedly been considered.126

In terms of economic effects of the sanctions, the results are mixed. The sanctions have contributed to the Maduro government's financial problems, including default on most of its loans and inability to raise new financing.127 However, the Maduro government has, to some extent, been able to work with Chinese and Russian governments to help fill financing gaps and continue to sell gold reserves to raise funds despite U.S. sanctions.128 Some analysts are also concerned that the stronger sanctions on PdVSA are further exacerbating Venezuela's difficult humanitarian crisis, already marked by shortages of food and medicines and mass migration, by limiting the country's key source of revenue.129 This is a particular concern in the event that Maduro remains in power over an extended period of time.

In terms of the sanctions' political effects, the imposition of targeted sanctions on individuals in the Maduro government has not encouraged many of those who were not yet sanctioned to abandon Maduro or changed the behavior of the sanctioned individuals. Instead, some officials (such as former vice president Tareck el Aissami and interior minister Nester Reverol) received promotions after being designated for sanctions by the United States, making their futures more dependent on remaining loyal to Maduro. While some have praised the Administration for removing the sanctions on General Figuera after he backed Guaidó, others have questioned how willing or able the U.S. government will be to lift sanctions on others, particularly in cases involving the Kingpin Act or for those who face U.S. criminal indictments.130 Observers have urged the Administration to coordinate the imposition or removal of future sanctions, including travel restrictions, with allies such as the EU and Canada, which have enacted similar sanctions.131 Broader U.S. sanctions adopted since 2017 have yet to compel Maduro to leave office despite the country's increasingly dire economic situation. They have also provided a foil on which Maduro has blamed the country's economic problems.

Energy Sector Concerns and U.S. Economic Sanctions132

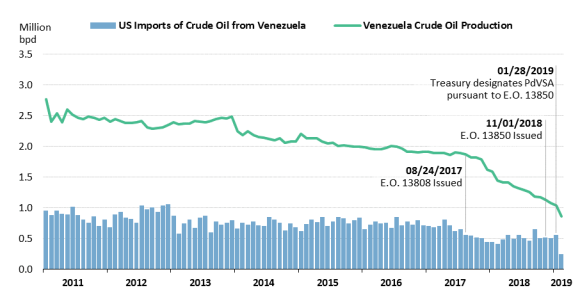

Venezuela's petroleum sector has experienced a general decline since the beginning of 2011, when crude oil production averaged approximately 2.5 million barrels per day (bpd) for the year. Prior to financial sanctions being imposed on PdVSA in August 2017 (E.O. 13808), oil production had already declined to approximately 1.8 million bpd.

Sanctions included in E.O. 13808 place limits on the maturity of new debt that U.S. entities can extend to PdVSA to 90 days. This limitation made it more difficult for PdVSA to pay for oil-related services and acquire certain oil production equipment. PdVSA has dealt with its fiscal problems by delaying payments and paying service providers with promissory notes in lieu of payments.133 There are concerns that delayed payments and promissory notes would count as new credit and, if their maturity exceeds 90 days, would violate sanctions. These payment issues have contributed to the slowdown in oil production, although they have not halted it.134 The financial sanctions also prevent PdVSA from receiving cash distributions from its U.S.-based Citgo refining subsidiary. While it is difficult to accurately quantify the impact of E.O. 13808 financial sanctions, data in Figure 4 suggest that Venezuela's oil production decline accelerated following the imposition of financial access restrictions on PdVSA.

As previously described, the Secretary of the Treasury determined on January 28, 2019 that persons (e.g., individuals and companies) operating in Venezuela's oil sector are subject to sanctions—pursuant to E.O. 13850—the goal being to apply economic pressure on the Maduro government. Subsequently, Treasury's OFAC added PdVSA—including all entities in which PdVSA has a 50% or more ownership position—to its Specifically Designated Nationals list. This designation blocks PdVSA's U.S. assets and prohibits U.S. persons from dealing with the company. These sanctions will affect several areas in which U.S. companies have business interests (e.g., debt/financial transactions and oil field services) and will effectively terminate U.S.-Venezuela petroleum (crude oil and petroleum products) trade. This is significant for Venezuela, as the United States was the primary cash buyer for exported crude oil.

Petroleum trade between the United States and Venezuela has been bilateral but has historically been dominated by Venezuela crude oil exports to the United States. Similar to oil production trends in Venezuela, U.S. oil imports of Venezuelan crude oil have been steadily declining since at least 2011 (see Figure 4) when import volumes were approximately 1 million bpd during certain months. When sanctions were imposed on PdVSA in January 2019, U.S. oil imports of Venezuelan crude oil were approximately 500,000 bpd. General licenses issued by OFAC allowed for U.S. entities to continue purchasing Venezuelan crude oil until April 28, 2019.135 However, payments made to PdVSA for imported petroleum during the wind-down period had to be made into a U.S.-based blocked account. This element of the petroleum trade sanctions motivated PdVSA to immediately seek alternative cash buyers.136 U.S. imports declined by 50% to approximately 250,000 bpd in the first month following the PdVSA designation.

Venezuela's oil production since January 2019 has been further challenged by access to petroleum blending components—referred to as diluents—and ongoing power outages that have affected oil production operations.137 PdVSA sanctions imposed in January 2019 prohibited U.S. diluent exports to Venezuela immediately. There was no wind-down period for this trade element. The characteristics of a large portion of Venezuela's crude oil—generally a heavy, low-viscosity, high-sulfur crude oil type—requires blending this crude oil with lighter petroleum materials in order to achieve a viscosity sufficient for transportation and processing. Typical diluents used for crude oil blending include naphtha and condensate, both light petroleum liquids that Venezuela has been importing from the United States. There are other non-U.S. diluent sources, and PdVSA will have to source diluent materials from alternative suppliers. However, it may take some time to secure alternative suppliers, and this constraint causes additional difficulty for PdVSA to continue its oil production operations. Furthermore, power outages in Venezuela have been reported since the January sanctions took effect.138 Limited power access is also creating difficulties for PdVSA oil production activities as pumping and processing equipment require power to operate.139

Direct impacts to U.S. oil refineries are somewhat difficult to assess due to the wind-down period provided by general licenses, opportunities to source similar crude oil types from other nonsanctioned countries, and refinery maintenance activities during the first half of 2019 that limited demand for oil import volumes. Mexico, Colombia, Canada, and Iraq are examples of countries that export crude oil with similar quality characteristics to that of Venezuela's heavy crude oil. However, movements in oil price benchmarks since January indicate that the differential between light sweet (low sulfur) and heavy sour (high sulfur) crude oil has narrowed. This price behavior can affect profit margins for refineries optimally configured to process heavy crude oil.140

|

Citgo's Uncertain Future: Multiple Creditors, Legal Claims, and New Management PdVSA's U.S.-based Citgo subsidiary owns and operates oil refineries in Texas, Louisiana, and Illinois. The company also owns 48 petroleum product terminals and a pipeline network that delivers these products to various customers. Citgo is arguably one of the most valuable assets in the PdVSA portfolio. PdVSA has looked to leverage that value to support its borrowing activities, as described below. All of Citgo's ownership has been used as collateral for two separate debt issuances (bonds and a loan to Rosneft, as described below). Additionally, companies that have sued Venezuela—such as Crytallex, discussed below—for expropriation actions have been awarded legal judgments that include taking possession of and liquidating Citgo assets.141 Furthermore, the U.S.-recognized Guaidó government appointed a new board of directors in February 2019 to manage Citgo, thereby removing Maduro's PdVSA from management decision-making of the U.S.-based company. Some of the financial and legal challenges facing Citgo are described below. PdVSA 2020 bonds (50.1% of Citgo as collateral): PdVSA issued bonds totaling approximately $3.4 billion in October 2016 to various creditors.142 A majority ownership stake in Citgo was pledged as collateral for the bonds, and the creditors could have legal claim to the company should the bonds enter into default.143 An interest payment for the bonds came due in April 2019.144 The payment was missed, but there is a 30-day grace period for the missed payment.145 The Maduro-controlled PdVSA—the original bond issuer—is prevented from making bond payments due to U.S. sanctions on PdVSA. However, a PdVSA board appointed by Guaidó voted to pay the $71 million interest payment, thus preserving Citgo ownership in the event that the opposition takes control of the Venezuela government. An additional $913 million payment is due in October 2019. Rosneft loan to PdVSA (49.9% of Citgo as collateral): PdVSA pledged 49.9% of Citgo ownership as collateral for a $1.5 billion loan from Russian oil company Rosneft that was issued in December 2016.146 The potential for a Russian company to own a significant portion of the U.S.-based Citgo operation has been noted by Members of Congress as a potential national security concern.147 In the 116th Congress, S. 1025 has been introduced and includes Section 609, which express concerns about Citgo ownership pledged as collateral for the Rosneft loan and requires the President to prevent Rosneft from taking control of U.S. energy infrastructure. Crystallex legal judgment ($1.2 billion judgment against PDV Holding, Citgo's parent company): In 2018, a U.S. district court ruled that Canada-based Crystallex could take shares of PDV Holding, the U.S.-based parent company of Citgo, as a means of collecting a $1.2 billion arbitration award made to Crystallex.148 The award stems from Venezuela's seizure of the Canadian miners' assets in 2011. Crystallex has indicated its intent to take ownership of Citgo shares and sell them for cash as a means of collecting the arbitration award. |

U.S. Humanitarian and Related Assistance149

The U.S. government is providing humanitarian and emergency food assistance and helping to coordinate and support regional response efforts. As of April 10, 2019 (latest data available), the United States has committed to providing more than $213.3 million since FY2017 for Venezuelans who have fled to other countries and for the communities hosting Venezuelan refugees and migrants, including nearly $130 million to Colombia.150 (Humanitarian funding is drawn primarily from the global humanitarian accounts in annual Department of State/Foreign Operations appropriations acts.) From October through December 2018, the U.S. Navy hospital ship USNS Comfort was on an 11-week medical support deployment to work with government partners in Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, and Honduras, in part to assist with arrivals from Venezuela. The Comfort is scheduled to deploy for another five-month deployment in June.151

In Colombia, the U.S. response aims to help the Venezuelan arrivals as well as the local Colombian communities that are hosting them. In addition to humanitarian assistance, the United States is providing $37 million in bilateral assistance to support medium and longer-term efforts by Colombia to respond to the Venezuelan arrivals.