Introduction

The rapid growth of digital technologies in recent years has created new opportunities for U.S. consumers and businesses but also new challenges in international trade. For example, consumers today access e-commerce, social media, telemedicine, and other offerings not imagined thirty years ago. Businesses use advanced technology to reach new markets, track global supply chains, analyze big data, and create new products and services. New technologies facilitate economic activity but also create new trade policy questions and concerns. Data and data flows form a pillar of innovation and economic growth.

The "digital economy" accounted for 6.9% of U.S. GDP in 2017, including (1) information and communications technologies (ICT) sector and underlying infrastructure, (2) digital transactions or e‐commerce, and (3) digital content or media.1 The digital economy supported 5.1 million jobs, or 3.3% of total U.S. employment in 2017, and almost two-thirds of jobs created in the United States since 2010 required medium or advanced levels of digital skills.2 As digital information increases in importance in the U.S. economy, issues related to digital trade have become of growing interest to Congress.

While there is no globally accepted definition of digital trade, the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) broadly defines digital trade as follows:

The delivery of products and services over the Internet by firms in any industry sector, and of associated products such as smartphones and Internet-connected sensors. While it includes provision of e-commerce platforms and related services, it excludes the value of sales of physical goods ordered online, as well as physical goods that have a digital counterpart (such as books, movies, music, and software sold on CDs or DVDs).3

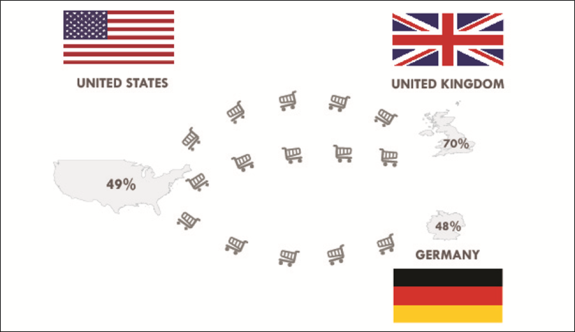

The rules governing digital trade are evolving as governments across the globe experiment with different approaches and consider diverse policy priorities and objectives. Barriers to digital trade, such as infringement of intellectual property rights (IPR) or protective industrial policies, often overlap and cut across sectors. In some cases, policymakers may struggle to balance digital trade objectives with other legitimate policy issues related to national security and privacy. Digital trade policy issues have been in the spotlight recently, due in part to the rise of new trade barriers, heightened concerns over data privacy, and an increasing number of cybertheft incidents that have affected U.S. consumers and companies. These concerns may raise the general U.S. interest in promoting, or restricting, cross-border data flows and in enforcing compliance with existing rules. Congress has an interest in ensuring the global rules and norms of the internet economy are in line with U.S. laws and norms.

Trade negotiators continue to explore ways to address evolving digital issues in trade agreements, including in the proposed U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Congress has an important role in shaping digital trade policy, including oversight of agencies charged with regulating cross-border data flows, as part of trade negotiations, and in working with the executive branch to identify the right balance between digital trade and other policy objectives.

This report discusses the role of digital trade in the U.S. economy, barriers to digital trade, digital trade agreement provisions and negotiations, and other selected policy issues.

Role of Digital Trade in the U.S. and Global Economy

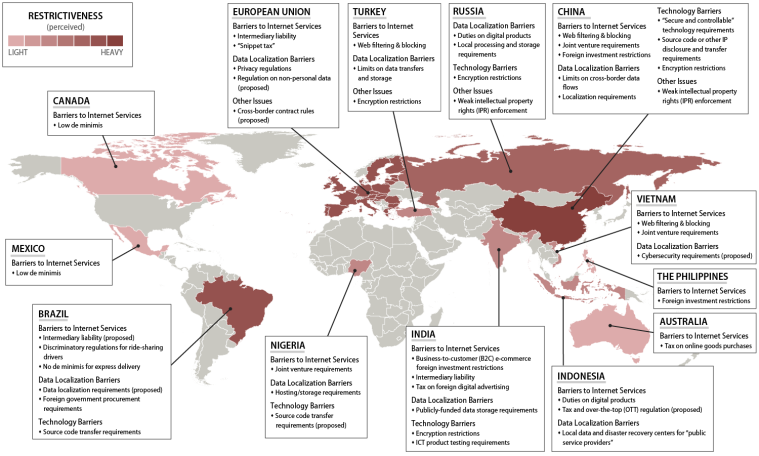

The internet is not only a facilitator of international trade in goods and services, but is itself a platform for new digitally-originated services. The internet is enabling technological shifts that are transforming businesses. According to one estimate, the volume of global data flows (sending of digital data such as from streaming video, monitoring machine operations, sending communications) is growing faster than trade or financial flows. One analysis forecasts the global flows of goods, foreign direct investment (FDI), and digital data will add 3.1% to gross domestic product (GDP) from 2015-2020. The volume of global data flows is growing faster than trade or financial flows, and its positive GDP contribution offsets the lower growth rates of trade and FDI (see Figure 1).4 Focusing domestically, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) estimates that, from 1997-2017, real value added for the digital economy outpaced overall growth in the economy each year and, in 2017, the real value-added growth of the digital economy accounted for 25% of total real GDP growth.5

|

|

Source: Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Zhiyao Lu, "Can Digital Flows Compensate for Lethargic Trade and Investment?," Peterson Institute for International Economics, November 28, 2018. Notes: Global internet traffic, measured in petabyte per month. Merchandise trade and FDI are normalized by dividing flows by world GDP; data flow is normalized by dividing flows by world population. |

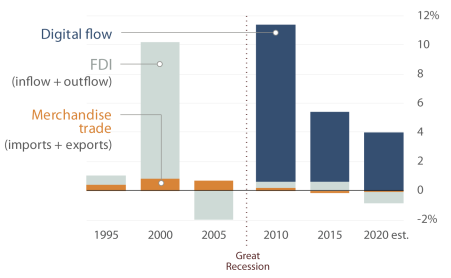

The increase in the digital economy and digital trade parallels the growth in internet usage globally. According to one study, over half of the world's population use the internet, including 95% of people in North America.6 As of 2017, 75% of U.S. households use wired internet access, but an increasing number rely on mobile internet access as the internet is integrated into people's everyday lives; 72% of U.S. adults own a smartphone.7 As of the end of 2018, approximately 40% of internet traffic in the United States came from mobile devices.8 Each day, companies and individuals across the United States depend on the internet to communicate and transmit data via various media and channels that continue to expand with new innovations (see Figure 2).

|

Figure 2. Snapshot of Most Popular Websites December 2018, Millions of unique U.S. visitors |

|

|

Source: Statistica.com. Note: * Examples of web properties owned by multinational companies. |

Cross-border data and communication flows are part of digital trade; they also facilitate trade and the flows of goods, services, people, and finance, which together are the drivers of globalization and interconnectedness. The highest levels reportedly are those flows between the United States and Western Europe, Latin America, and China. Efforts to impede cross-border data flows could decrease efficiency and other potential benefits of digital trade.

Powering all these connections and data flows are underlying ICT.9 ICT spending is a large and growing component of the international economy and essential to digital trade and innovation. According to the United Nations, world trade in ICT physical goods grew to $2 trillion in 2017 with U.S. ICT goods exports over $146 billion.10

Semiconductors, a key component in many electronic devices, are a top U.S. ICT export. Global sales of semiconductors were $468.8 billion in 2018, an increase of 6.81% over the prior year.11 U.S.-based firms have the largest global market share with 45% and accounted for 47.5% of the Chinese market. Given the importance of semiconductors to the digital economy and continued advances in innovation, countries such as China are seeking to grow their own semiconductor industry to lessen their dependence on U.S. exports.

ICT services are outpacing the growth of international trade in ICT goods. The OECD estimates that ICT services trade increased 40% from 2010 to 2016. The United States is the fourth-largest OECD exporter of ICT services, after Ireland, India, and the Netherlands.12 ICT services include telecommunications and computer services, as well as charges for the use of intellectual property (e.g., licenses and rights). ICT-enabled services are those services with outputs delivered remotely over ICT networks, such as online banking or education. ICT services can augment the productivity and competitiveness of goods and services. In 2017, exports of ICT services grew to $71 billion of U.S. exports while services exports that could be ICT-enabled were another $439 billion, demonstrating the impact of the internet and digital revolution.13

ICT and other online services depend on software; the value added to U.S. GDP from support services and software has increased over the past decade relative to that of telecommunications and hardware.14 According to one estimate, software contributed more than $1.14 trillion to the U.S. value added to GDP in 2016, an increase of 6.4% over 2014, and the U.S. software industry accounted for 2.9 million jobs directly in 2016.15 Internet-advertising, an industry that would not exist without ICT, generated an additional 10.4 million U.S. jobs.16

Economic Impact of Digital Trade

As the internet and technology continue to develop rapidly, increasing digitization affects finance and data flows, as well as the movement of goods and people. Beyond simple communication, digital technologies can affect global trade flows in multiple ways and have broad economic impact (see Figure 3). First, digital technology enables the creation of new goods and services, such as e-books, online education, or online banking services. Digital technologies may also add value by raising productivity and/or lowering the costs and barriers related to flows of traditional goods and services. For example, companies may rely on radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags for supply chain tracking, 3-D printing based on data files, or devices or objects connected via the Internet of Things (see text box). In addition, digital platforms serve as intermediaries for multiple forms of digital trade, including e-commerce, social media, and cloud computing. In these ways, digitization pervades every industry sector, creating challenges and opportunities for established and new players.

Looking at digital trade in an international context, approximately 12% of physical goods are traded via international e-commerce.17 Global e-commerce grew from $19.3 trillion in 2012 to $27.7 trillion in 2016, of which 86% was business-to-business (B2B).18 One source estimates that cross-border business-to-consumer (B2C) e-commerce sales will reach approximately $1 trillion by 2020.19

These estimates do not quantify the additional benefits of digitization upon business efficiency and productivity, or of increased customer and market access, which enable greater volumes of international trade for firms in all sectors of the economy. Digitization efficiencies have the potential to both increase and decrease international trade. For example, one analysis found that logistics optimization technologies could reduce shipping and customs processing times by 16% to 28%, boosting overall trade by 6% to 11% by 2030; at the same time, however, automation, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and 3-D printing could enable more local production, thereby reducing global trade by as much as 10% by 2030.20 The overall impact of digitization has yet to be seen.

One study coined the term "digital spillovers" to fully capture the digital economy and estimated the global digital economy, including such spillovers, was $11.5 trillion in 2016, or 15.5% of global GDP.21 Their analysis indicated that the long-term return on investment (ROI) for digital technologies is 6.7 times that of nondigital investments.22

Blockchain is one emerging software technology some companies are using to increase efficiency and transparency and lower supply chain costs that depends on open data flows of digital trade.23 For example, in an effort to streamline processes, save costs, and improve public health outcomes, Walmart and IBM built a blockchain platform to increase transparency of global supply chains and improve traceability for certain imported food products.24 The initiative aims to expand to include several multinational food suppliers, farmers, and retailers and depends on connections via the Internet of Things and open international data flows. With increased applications, the Internet of Things may have a global economic impact of as much as $11.1 trillion per year, according to one study.25

|

Key Emerging Technologies Internet of Things (IoT) "encompass(es) all devices and objects whose state can be read or altered via the internet, with or without the active involvement of individuals.... The internet of things consists of a series of components of equal importance—machine-to-machine communication, cloud computing, big data analysis, and sensors and actuators. Their combination, however, engenders machine learning, remote control, and eventually autonomous machines and systems, which will learn to adapt and optimise themselves."26 Blockchain "is a distributed record-keeping system (each user can keep a copy of the records) that provides for auditable transactions and secures those transactions with encryption. Using blockchain, each transaction is traceable to a user, each set of transactions is verifiable, and the data in the blockchain cannot be edited without each user's knowledge. Compared to traditional technologies, blockchain allows two or more parties without a trusted relationship to engage in reliable transactions without relying on intermediaries or central authority (e.g., a bank or government)."27 Artificial Intelligence (AI) "AI can generally be thought of as computerized systems that work and react in ways commonly thought to require intelligence, such as solving complex problems in real-world situations."28 |

Because of its ubiquity, the benefits and economic impact of digitization are not restricted to certain geographic areas, and businesses and communities in every U.S. state feel the impact of digitization as new business models and jobs are created and existing ones disrupted.29 One study found that the more intensively a company uses the internet, the greater the productivity gain. The increase in internet usage is also associated with increased value and diversity of products being sold.30

The internet, and cloud services specifically, has been called the great equalizer, since it allows small companies access to the same information and the same computing power as large firms using a flexible, scalable, and on-demand model. For example, Thomas Publishing Co., a U.S. mid-sized, private, family-owned and -operated business, is transporting data from its own computer servers to data centers run by Amazon.com Inc.31 Digital platforms can minimize costs and enable small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to grow through extended reach to customers or suppliers or integrating into a global value chain (GVC). More than 50% of businesses globally rely on data flows for cloud computing (see text box).32

Digitization of customs and border control mechanisms also helps simplify and speed delivery of goods to customers. Regulators are looking to blockchain technology to improve efficiency in managing and sharing data for functions such as border control and customs processing of international shipments.33 With simpler border and customs processes, more firms are able to conduct business in global markets (or are more willing to do so). A study of U.S. SMEs on the e-commerce platform eBay found that 97% export, while that number is a full 100% in countries as diverse as Peru and Ukraine.34 Netflix, a U.S. firm offering online streaming services, increased its international revenue from $4 million in 2010 to more than $5 billion in 2017.35

|

A Local Manufacturer Grows Through Digital Trade Kirk Anton and Tricia Hudson launched their business in 2010 as a one-stop shop for heat transfer materials, importing heat-applied materials and creating customized products for clients. The company moved online and converted to completely digital in 2013, using services such as Google Analytics to inform their marketing campaigns. Growing by more than 70% over four years, in 2017 the company employed forty people in Florida, Kentucky, Nevada, and North Dakota, and boasted over 85,000 customers across the globe.36 |

A similar argument has been made for firms and governments in low- and middle-income countries who can take advantage of the power of the internet to foster economic development. According to one official of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum (APEC), technology has enabled SMEs to open in new sectors such as ride-sharing and online order delivery services, and provides them with a "bigger, better opportunity to grow and learn that to join a global value chain."37 Another study of SMEs estimated that the internet is a net creator of jobs, with 2.6 jobs created for every job that may be displaced by internet technologies; companies that use the internet intensively effectively doubled the average number of jobs.38 However, the costs of digital trade can be concentrated on particular sectors (see next section).

Digitization Challenges

The U.S. digital economy supported 3.3% of total U.S. employment in 2017, and those jobs earned approximately one and a half times the average annual worker compensation of the overall U.S. economy, making them attractive source for future growth.39 Software, and the software industry, contributes to the GDP in all 50 states, with the value-added GDP of the software industry growing more than 40% in Idaho and North Carolina.40 Industries, such as media and firms in urban centers, account for a larger share of the benefits. Many in business and research communities are only beginning to understand how to take advantage of the vast amounts of data being collected every day.

However, sources of "e-friction" or obstacles can prevent consumers, companies, and countries from realizing the full benefits of the online economy.41 Causes of e-friction can fall into four categories: infrastructure, industry, individual, and information. Government policy can influence e-friction, from investment in infrastructure and education to regulation and online content filtering. According to some experts, economies with lower amounts of e-friction may be associated with larger digital economies.42

While there are numerous positive digital dividends, there are also possible negative and uneven results across populations, such as the displacement of unskilled workers, an imbalance between companies with and without internet access, and the potential for some to use the internet to establish monopolies.43 While new technologies and new business models present opportunities to enhance efficiency and expand revenues, innovate faster, develop new markets, and achieve other benefits, new challenges also arise with the disruption of supply chains, labor markets, and some industries. For example, one study found a mismatch between workforce skills and job openings such as in Nashville, TN, which has an abundance of workers with music production and radio broadcasting skills but a scarcity of workers with IT infrastructure, systems management, and web programming skills.44 Another source notes over 11,000 open computing jobs in Michigan, with average salaries of over $80,000.45

The World Bank identified policy areas to try to ensure, and maintain, the potential benefits of digitization. Policy areas include establishing a favorable and competitive business climate, developing strong human capital, ensuring good governance, investing to improve both physical and digital infrastructure, and raising digital literacy skills. According to the World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Index 4.0, the United States is ranked at the top with a score of 85.6% compared to the global median score of 60%.46 The study identifies the key drivers of productivity as human capital, innovation, resilience, and agility, noting that future productivity depends not only on investment in technology but investment in digital skills. While the United States is considered a "super innovator," the report also notes "indications of a weakening social fabric … and worsening security situation … as well as relatively low checks and balances, judicial independence, and transparency."47

With the rapid pace of technology innovation, more jobs may become automated, with digital skills becoming a foundation for economic growth for individual workers, companies, and national GDP.48 Over two-thirds of U.S. jobs created since 2010 require some level of digital skills.49 The OECD found that generic ICT skills are insufficient among a significant percentage of the global workforce and few countries have adopted comprehensive ICT skills strategies to help workers adapt to changing jobs.50

Digital Trade Policy and Barriers

Policies that affect digitization in any one country's economy can have consequences beyond its borders, and because the internet is a global "network of networks," the state of a country's digital economy can have global ramifications. Protectionist policies may erect barriers to digital trade, or damage trust in the underlying digital economy, and can result in the fracturing, or so-called balkanization, of the internet, lessening any gains. What some policymakers see as protectionist, however, others may view as necessary to protect domestic interests. For examples of the types of digital trade barriers that are in place around the globe, please see Appendix.

Despite common core principles such as protecting citizen's privacy and expanding economic growth, governments face multiple challenges in designing policies around digital trade. The OECD points out three potentially conflicting policy goals in the internet economy: (1) enabling the internet; (2) boosting or preserving competition within and outside the internet; and (3) protecting privacy and consumers more generally.51

Ensuring a free and open internet is a stated policy priority for the U.S. government.52 Like other cross-cutting policy areas, such as cybersecurity or privacy, no one federal entity has policy primacy on all aspects of digital trade, and the United States has taken a sectoral approach to regulating digitization. According to an OECD study, the United States is the only OECD country that uses a decentralized, market-driven approach for a digital strategy rather than having an overarching national digital strategy, agenda, or program.53

|

Protect a Free and Open Internet54 Protecting a free and open internet is a policy priority as stated in President Trump's 2017 National Security Strategy. "The United States will advocate for open, interoperable communications, with minimal barriers to the global exchange of information and services. The United States will promote the free flow of data and protect its interests through active engagement in key organizations, such as the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), the UN, and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU)." |

The Department of Commerce works to promote U.S. digital trade policies domestically and abroad. In 2015, Commerce launched a Digital Economy Agenda that identifies four pillars:55

- 1. "Promoting a free and open Internet worldwide, because the Internet functions best for our businesses and workers when data and services can flow unimpeded across borders";

- 2. "Promoting trust online, because security and privacy are essential if electronic commerce is to flourish";

- 3. "Ensuring access for workers, families, and companies, because fast broadband networks are essential to economic success in the 21st century"; and

- 4. "Promoting innovation, through smart intellectual property rules and by advancing the next generation of exciting new technologies."

Commerce's digital attaché program under the foreign commercial service helps U.S. businesses navigate regulatory issues and overcome trade barriers to e-commerce exports in key markets.56

The Administration also works to promote U.S. digital priorities by identifying and challenging foreign trade barriers and through trade negotiations. As with traditional trade barriers, digital trade constraints can be classified as tariff or nontariff barriers. Tariff barriers may be imposed on imported goods used to create ICT infrastructure that make digital trade possible or on the products that allow users to connect, while nontariff barriers, such as discriminatory regulations or local content rules, can block or limit different aspects of digital trade. Often, such barriers are intended to protect domestic producers and suppliers. Some estimates indicate that removing foreign barriers to digital trade could increase annual U.S. real GDP by 0.1%-0.3% ($16.7 billion-$41.4 billion), increase U.S. wages up to 1.4%, and add up to 400,000 U.S. jobs in certain digitally intensive industries.57

|

2015 U.S. Digital Trade Negotiating Objectives Congress enhanced its digital trade policy objectives for U.S. trade negotiations in the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-26), or Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), signed into law in June 2015.58 TPA 2015 objectives related to digital trade direct the Administration to negotiate agreements that

|

Tariff Barriers

Historically, trade policymakers focused on overt trade barriers such as tariffs on products entering countries from abroad. Tariffs at the border impact goods trade by raising the prices of products for producers or end customers, if tariff costs are passed down, thus limiting market access for U.S. exporters selling products, including ICT goods. Quotas may limit the number or value of foreign goods, persons, suppliers, or investments allowed in a market. Since 1998, WTO countries have agreed to not impose customs duties on electronic transmissions covering both goods (such as e-books and music downloads) and services.

While the United States is a major exporter and importer of ICT goods, tariffs are not levied on many of the products due to free trade agreements (FTAs) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) Information Technology Agreement (see below). Tariffs may still serve as trade barriers for those countries or products not covered by existing FTAs or the WTO ITA.

U.S. ICT services are often inputs to final demand products that may be exported by other countries, such as China. U.S. ICT services have shown increasing growth rates since the middle of 2014.59

|

ICT Goods Tariff Barriers: Selected Examples Brazil, Mexico, and Vietnam are key participants in the ICT goods market and impose high tariffs on non-FTA partners. According to the United Nations Statistics Division, in 2015 Brazil reported $1.3 billion in medical ICT equipment imports, such as electrocardiographs, ultrasound devices, and magnetic resonance imaging devices,60 despite tariffs of up to 16% on these products.61 In 2014, Vietnam reportedly imported $10.3 billion worth of electronic integrated circuits (microchips) and parts, including approximately 4% or $398 million from the United States.62 While Vietnam imposes no tariffs on these product categories, several ICT items in Vietnam's tariff schedule have high applied rates, including multiple categories of radio equipment, which have an applied rate as high as 30% according to the WTO.63 |

Nontariff Barriers

|

|

Nontariff barriers (NTBs) are not as easily quantifiable as tariffs. Like digital trade, NTBs have evolved and may pose significant hurdles to companies seeking to do business abroad. NTBs often come in the form of laws or regulations that intentionally or unintentionally discriminate and/or hamper the free flow of digital trade.

Nondiscrimination between local and foreign suppliers is a core principle encompassed in global trading rules and U.S. free trade agreements. While WTO agreements cover physical goods, services, and intellectual property, there is no explicit provision for nondiscrimination for digital goods. As such, NTBs that do not treat digital goods the same as physical ones could limit a provider's ability to enter a market.

Broader governance issues, including rule of law, transparency, and investor protections, can pose barriers and limit the ability of firms and individuals to successfully engage in digital trade. Similarly, market access restrictions on investment and foreign ownership, or on the movement of people, whether or not specific to digital trade or ICT sectors, may limit a company's ability enter a foreign market. Other NTBs are more specific to digital trade.

Localization Requirements

Localization measures are defined as measures that compel companies to conduct certain digital-trade-related activities within a country's borders.64 Governments often use privacy protection or national security arguments as justifications for these measures. Though localization policies can be used to achieve legitimate public policy objectives, some are designed to protect, favor, or stimulate domestic industries, service providers, or intellectual property at the expense of foreign counterparts and, in doing so, function as nontariff barriers to market access. In recent free trade agreements, the United States has aimed to ensure an open internet and eliminate digital trade barriers, while preserving flexibility for governments to pursue legitimate policy objectives (see below).

Cross-Border Data Flow Restrictions

According to a 2017 USITC report, data localization was the most cited policy measure impeding digital trade, and the number of data localization measures globally has doubled in the last six years.65 One study found that over 120 countries have laws related to personal data protection, often requiring data localization.66 Regulations limiting cross-border data flows and requiring local storage are a type of localization requirement that prohibit companies from exporting data outside a country.

Such restrictions can pose barriers to companies whose transactions rely on the internet to serve customers abroad and operate more efficiently. For example, data localization requirements can limit e-commerce transactions that depend on foreign financial service providers or multinational firms' full analysis of big data from across an entire company or global value chain. Regulations limiting cross-border data flows may force companies to build local server infrastructure within a country, not only increasing costs and decreasing scale, but also creating data silos that may be more vulnerable to cybersecurity risks. According to some analysts, computing costs in markets with localization measures can be 30%-60% higher than in more open markets.67

Data localization requirements pose barriers to companies' efforts to operate more efficiently by migrating to the cloud or to SMEs attempting to enter new markets. According to some estimates, cloud computing accounted for 70% of related IT market growth between 2012 and 2015, and is expected to represent 60% of growth through 2020.68 Most of the largest global providers of cloud computing services are U.S. companies (Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and IBM).

Regulations or policies that limit data flows create barriers to firms and countries seeking to consume cloud services. One U.S. business group noted increased forced localization measures, citing examples in China, Colombia, the European Union (EU), Indonesia, South Korea, Russia, and Vietnam.69 The Business Software Alliance's 2018 Global Cloud Computing Scorecard highlighted barriers to cloud services in Indonesia, Russia, and Vietnam.70 For example, to comply with localization requirements and continue to serve consumers of Google's many cloud services (e.g., Gmail, search, maps) globally, the company is opening more data centers in the United States and internationally.71

Finding a global consensus on how to balance open data flows, cybersecurity, and privacy protection may be key to maintaining trust in the digital environment and advancing international trade.72 Countries are debating how to achieve the right balance and potential paths forward in plurilateral and multilateral forums and trade negotiations (see "U.S. Bilateral and Plurilateral Agreements").

Other Localization Requirements

In addition to cross-border data flow restrictions, localization policies include requirements to use local content, whether hardware or software, as a condition for manufacturing or access to government procurement contracts; use local infrastructure or computing facilities; or partner with a local company and transfer technology or intellectual property to that partner. Localization requirements can also pose a threat to intellectual property (discussed below).

In April 2018, the Commerce Department announced plans to develop a "comprehensive strategy to address trade-related forced localization policies, practices, and measures impacting the U.S. information and communications technology (ICT) hardware manufacturing industry."73 In creating a strategic response to the increase in protectionist localization policies globally, Commerce aims to preserve the competitiveness of the U.S. ICT sector.74

|

Examples of Localization Barriers Examples of localization barriers include the following:

Source: 2019 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers, Office of the United States Trade Representative, March 2019. |

Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Infringement

While the internet and digital technologies have opened up markets for international trade, they also present ongoing and unique challenges for the protection and enforcement of intellectual property (IP), which are creations of the mind—such as an invention, literary/artistic work, design, symbol, name, or image—embodied in a physical or digital object. Intellectual property rights (IPR)75 are legal, private, enforceable, time-limited rights that governments grant to inventors and artists to exclude others from using their creations without their permission. Examples of IPR include patents, copyrights, trademarks, and trade secrets.

Innovations in digital technologies fuel IPR infringement by enabling the rapid duplication and distribution of content that is low-cost and high-quality, making it easy, for instance, to pirate music, movies, software, and other copyrighted works, and to share them globally. The internet provides "ease of conducting commerce through unverified vendors, inability for consumers to inspect goods prior to purchase, and deceptive marketing."76 Both copyright- and trademark-based industries face challenges tackling not only infringement in physical marketplaces, but increasingly also online marketplaces.77 Cyber-enabled theft of trade secrets is of growing concern. Trade secrets are essential to many businesses' operations and important assets, including those in ICT, services, biopharmaceuticals, manufacturing, and environmental and other technologies.

IPR infringement in the digital environment is particularly difficult to quantify but considered to be significant, potentially exceeding the volume of sales through traditional physical markets.78 A 2016 industry study estimated the value of digitally pirated music, movies, and software (not actual losses) to be $213 billion in 2013 and growing to as much as $384-$856 billion in 2022.79 The IP Commission estimated that the annual cost to the U.S. economy from counterfeit goods, pirated software, and theft of trade secrets continues to surpass $225 billion and could reach $600 billion.80

Efforts to address IPR infringement raise issues of balance about, on one hand, protecting and enforcing IPR to protect the rights of content holders and incentivize innovation in the digital environment and, on the other hand, setting appropriate limitations and exceptions to ensure other economically and socially valuable uses. Content industries say that IP theft costs them sales, detracts from legitimate services, harms investors in these businesses, damages their brand or reputation, and hurts "law-abiding" consumers. Some technology product and service companies, as well as some civil society groups, assert that overly stringent IPR policies may stifle information flows and legitimate digital trade and these groups support "fair use" exceptions and limitations to IPR.81

|

New EU Copyright Rules The EU's new copyright directive highlights the debate over balance, and has implications for U.S. digital trade. On April 15, 2019, the EU adopted the new rules to modernize its copyright laws to adapt to the digital environment. One objective of the directive is to create a fairer marketplace for online content for creators and press. The directive introduces an EU-wide "neighboring right" to allow news publishers to be compensated for the use of their articles by online platforms, as well provide for journalists to receive an appropriate share of the revenues generated. News platforms such as Google will have to negotiate licenses from newspapers and other publishers for showing content that is under two-years-old on their news feeds. Short extracts from press publications—sometimes called "snippets"—are outside of the scope of the rule.82 The directive also reinforces the position of creators and right holders to negotiate and secure compensation for online use of their content hosted in the EU by major content platforms such as YouTube. If no licensing agreement exists between creators and the online platforms, YouTube and other such platforms must demonstrate "best efforts" to remove copyright materials if they are notified of infringing uploads. Newer and smaller platforms are not subject to all of these requirements. The directive addresses other digital copyright issues as well. Some U.S. stakeholders, such as the publishing industry, support the new rules, while others, including U.S. businesses that are content-aggregators, have raised concerns about increased costs, market access barriers, and effects on the innovation environment of the new rules.83 After the publication of the directive in the Official Journal of the EU, member states will have 24 months to transpose the new rules into their national law. |

Other IPR-related barriers to digital trade include government measures, policies, and practices that are intended to promote domestic "indigenous innovation" (i.e., develop, commercialize, and purchase domestic products and technologies) but that can also disadvantage foreign companies. These measures can be linked to "forced" localization barriers to trade. China, for instance, conditions market access, government procurement, and the receipt of certain preferences or benefits on a firm's ability to show that certain IPR is developed in China or is owned by or licensed to a Chinese party. Another example is India's data and server localization requirements, which USITC firms assert hurt market access and innovation in their sector. (See above.)

National Standards and Burdensome Conformity Assessment

Local or national standards that deviate significantly from recognized international standards may make it difficult for firms to enter a particular market. An ICT product or software that conforms to international standards, for example, may not be able to connect to a local network or device based on a local or proprietary standard. Also, proprietary standards can limit a firm's ability to serve a market if their company practices or assets do not conform with (nor do their personnel have training in) those standards. As a result, U.S. companies may not be able to reach customers or partners in those countries.

Similarly, redundant or burdensome conformity assessment or local registration and testing requirements often add time and expense for a company trying to enter a new market, and serve as a deterrent to foreign companies. For example, India's Compulsory Registration Order (CRO) mandates that manufacturers register their products with laboratories affiliated with or certified by the Bureau of Indian Standards, even if the products have already been certified by accredited international laboratories, and is an often-cited concern for U.S. businesses facing delays getting products to market.84 If a company is required to provide the source code, proprietary algorithms, or other IP to gain market access, it may fear theft of its IP and not enter that market (see above).

Filtering, Blocking, and Net Neutrality

In some nations, government seeks strict control over digital data within its borders, such as what information people can access online, and how information is shared inside and outside its borders. Governments that filter or block websites, or otherwise impede access, form another type of nontariff barrier. For example, China has asserted a desire for "digital sovereignty" and has erected what is termed by some as the "Great Firewall." A change to China's internet filters also blocks virtual private network (or VPN) access to sites beyond the Great Firewall. VPNs have been used by Chinese citizens to use websites like Facebook and by companies to access data outside of China (e.g., information from foreign subsidiaries or partners).85

While China is the most well-known, it is not alone in seeking to control access to websites. For example, Thailand established a Computer Data Filtering Committee to use the court system to block websites that it views as violating public order and good order, as well as intellectual property.86 In Russia, citizens protested government censorship, including the blocking of a popular messaging application along with other websites and online tools.87

Several U.S. and foreign policymakers have expressed concern about the influence that violent or harmful content online may have upon those who view or read it. In response, some countries have introduced legislation to regulate internet content, for example, to fight the impact and spread of violent material and false information.88 In the United States, significant First Amendment freedom of speech issues are raised by the prospect of government restrictions on the publication and distribution of speech, even speech that advocates terrorism.89 As a result, what users can access online may vary across countries, depending on national policy and preferences. These differences illustrate the complexity of the internet and evolving technologies, and the lack of global standards that prevails in other areas of international trade.

National-level net neutrality policies also differ widely. Net neutrality rules govern the management of internet traffic as it passes over broadband internet access services, whether those services are fixed or wireless. Allowing internet access providers to limit or otherwise discriminate against content providers, foreign and domestic, may create a nontariff barrier.90 In the United States, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) classification of broadband internet service providers (ISPs) has been controversial domestically and may differ from how U.S. trading partners regulate ISPs.

Cybersecurity Risks

The growth in digital trade has raised issues related to cybersecurity, the act of protecting ICT systems and their contents from cyberattacks. Cyberattacks in general are deliberate attempts by unauthorized persons to access ICT systems, usually with the goal of theft, disruption, damage, or other unlawful actions. Cybersecurity can also be an important tool in protecting privacy and preventing unauthorized surveillance or intelligence gathering.91 Although there is overlap between data protection and privacy, the two are not equivalent. Cybersecurity measures are essential to protect data (e.g., against intrusions or theft by hackers). However, they may not be sufficient to protect privacy.

Cyberattacks can pose broad risks to financial and communication systems, national security, privacy, and digital trade and commerce. According to the White House Council of Economic Advisers, malicious cyberactivity (i.e., business disruption, theft of proprietary information) cost the U.S. economy up to $109 billion in 2016.92 Cybersecurity risks run across all industry sectors that rely on digital information. In the entertainment industry, for example, Iranian hackers stole unreleased episodes of HBO's "Game of Thrones" series, holding them for ransom, and potentially costing the company and risking intellectual property and harm to the corporate reputation.93 The Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) suspects Chinese hackers were behind a cyberattack on the Marriot's Starwood hotel chain that resulted in potentially stealing IPR and the personal information of up to 327 million hotel customers, including their birthdates and passport numbers.94 An FBI official testified to the Senate Judiciary Committee that Chinese espionage efforts have become "the most severe counterintelligence threat facing our country today."95

Cybersecurity threats can disrupt business operations or supply chains. The 2017 WannaCry ransomware attack impacted public and private sector entities in over 150 countries with direct costs of at least $8 billion due to computer downtime, according to one estimate.96 In the widespread attack, computers in homes, schools, hospitals, government agencies, and companies were hit. The United States publicly attributed the cyberattack to North Korea, stating that "these disruptions put lives at risk."97 Compromises of ITC supply chains can also pose a threat to organizations that rely on the tampered hardware as was alleged, for example, with some Supermicro microchips used in ITC manufacturing in China.98

Companies that rely on cloud services to store or transmit data may choose to use enhanced encryption to protect the communication and privacy, both internally and of their end customers. This, in turn, may impede law enforcement investigations if they are unable to access the encrypted data.99 However, restrictions on the ability for a firm to use encryption may make a company vulnerable to cyberattacks or cybertheft, demonstrating the need for policies and regulations to balance competing objectives.

U.S. Digital Trade with Key Trading Partners

The European Union (EU) and China are large U.S. digital trade partners and each has presented various challenges for U.S. companies, consumers, and policymakers.

European Union

Differences in U.S. and EU policies have ramifications on digital flows and international trade. The two partners' varying approaches to digital trade, privacy, and national security, have, at times, threatened to disrupt U.S.-EU data flows.

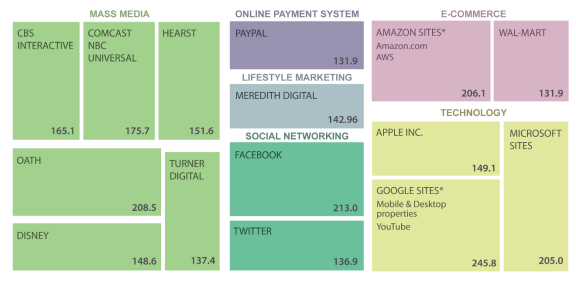

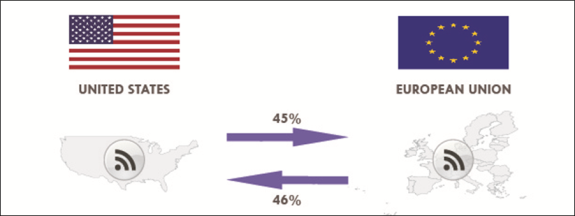

The transatlantic economy is the largest in the world, and cross-border data flows between the United States and EU are the highest in the world. In between 2003 and 2017, total U.S.-EU trade in goods and services (exports plus imports) nearly doubled from $594 billion to $1.2 trillion.100 ICT and potentially ICT-enabled services accounted for approximately $190 billion of U.S. exports to the EU in 2017.101 The two sides also account for a significant portion of each other's e-commerce trade (see Figure 4).

|

|

Source: Kati Souminen, "Where the Money Is: The Transatlantic Digital Market," CSIS, October 12, 2017. Notes: 48% of German and 70% of UK shoppers purchase from U.S. e-commerce sites. 49% of U.S. e-commerce purchases are from UK sites. |

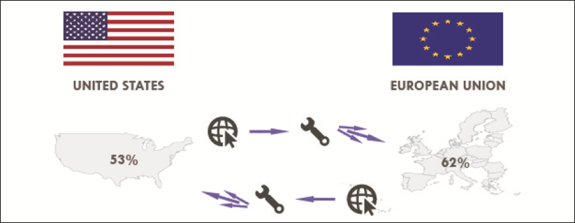

The United States and EU account for almost half of each other's digitally deliverable service exports (e.g., business, professional, and technical services) and many of these services are incorporated into exported goods as part of GVCs (see Figure 5 and Figure 6).102 The UK alone accounted for 23% of U.S. digitally deliverable services exports.103 Almost 40% of the data flows between the United States and EU are through business and research networks.104

|

|

Source: "Where the Money Is: The Transatlantic Digital Market," CSIS, October 12, 2017. |

|

Figure 6. Digitally Deliverable Services Incorporated into Global Value Chains |

|

|

Source: "Where the Money Is: The Transatlantic Digital Market," CSIS, October 12, 2017. |

Despite close economic ties, differences between the United States and EU in their approaches to data flows and digital trade have caused friction in U.S.-EU economic and security relations. To address some of these differences, in 2013, the United States and the EU began, but did not conclude, negotiating a broad FTA. Negotiations included a number of digital trade issues such as market access for digital products, IPR protection and enforcement, cybersecurity, and regulatory cooperation, among other things.105 On October 16, 2018, the Trump Administration notified Congress under Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) of its intent to enter into negotiations with the EU. The Administration's specific negotiating objectives envision a wide-ranging agreement, including addressing digital trade, along with trade in goods, services, agriculture, government procurement, and other rules, such as on IPR and investment.106 However, no agreement exists on the scope of the negotiations. The EU negotiating mandates, in contrast, are narrower; they authorize EU negotiations with the United States to address industrial tariffs (excluding agricultural products) and nontariff regulatory barriers to make it easier for companies to prove that their products meet U.S. and EU technical requirements.107

The Administration also notified Congress under TPA of its intent to negotiate a trade agreement with the UK post-Brexit, and the corresponding specific negotiating objectives likewise envision a broad agreement addressing digital trade issues. The UK cannot formally negotiate or conclude a new agreement until it exits the EU, which has exclusive competence over trade policy and negotiates trade deals on behalf of all EU member states. Details about the future UK-EU trade relationship remain largely unknown, and it is uncertain when and to what extent the UK will regain control of its national trade policy—a major objective for Brexit supporters. These factors directly shape prospects for a proposed bilateral U.S.-UK free trade agreement.108

EU-U.S. Privacy Shield

The United States and EU have different legal approaches to information privacy that extends into the digital world. After extensive negotiations, the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield entered into force on July 12, 2016, creating a framework to provide U.S. and EU companies a mechanism to comply with data protection requirements when transferring personal data between the EU and the United States.109 Under the Privacy Shield program, U.S. companies can voluntarily self-certify compliance with requirements such as robust data processing obligations. The agreement includes obligations on the U.S. government to proactively monitor and enforce compliance by U.S. firms, establish an ombudsman in the U.S. State Department, and set specific safeguards and limitations on surveillance. The United States and Switzerland also agreed to the Swiss-U.S. Privacy Shield, which will be "comparable" to the EU-U.S. agreement.110

The Privacy Shield also involves an annual joint review by the United States and the EU, the second of which was completed in October 2018.111 Under the review, the commission found that the Privacy Shield is working and that the United States had made improvements and changes since the first review. The Commission, however, also noted areas of concern and specific recommendations.

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

The EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), effective May 2018, established rules for EU member states to safeguard individuals' personal data. The GDPR is a comprehensive privacy regime that builds on previous EU data protection rules. It grants new rights to individuals to control personal data and creates specific new data protection requirements. The GDPR applies to (1) all businesses and organizations with an EU establishment that process (perform operations on) personal data of individuals (or "data subjects") in the EU, regardless of where the actual processing of the data takes place; and (2) entities outside the EU that offer goods or services (for payment or for free) to individuals in the EU or monitor the behavior of individuals in the EU. These measures have raised concerns about the GDPR's extraterritorial implications.

While the GDPR is directly applicable at the EU member state level, individual countries are responsible for establishing some national-level rules and policies as well as enforcement authorities, and some are still in the process of doing so. As a result, some U.S. stakeholders have voiced concern about a lack of clarity and inadequate country compliance guidelines, as well as about the potential high cost of data storage and processing needed for compliance. Despite the lack of precise guidance, many companies have taken steps to implement its requirements. For example, Amazon touts its compliance with GDPR requirements and aims to assist its Amazon Web Services (AWS) corporate customers, many of whom are small and medium businesses, with their own compliance.112 It can be more challenging for SMEs to fully understand GDPR and comply with its notification and other requirements such as an individual's "right to be forgotten" and on data portability; there are indications that some U.S. businesses have chosen to exit the EU market.113

Some experts contend that the GDPR may effectively set new global data privacy standards, since many companies and organizations are striving for GDPR compliance to avoid being shut out of the EU market, fined, or otherwise penalized. In addition, some countries outside of Europe are imitating all or parts of the GDPR in their own privacy regulatory and legislative efforts. European Data Protection Authorities may have reinforced U.S. companies' concerns by initiating several enforcement actions in the fall of 2018, including a €50 million (approximately $57 million) fine on Google.114

Digital Single Market (DSM)

Like the GDPR, EU policymakers are attempting to bring more harmonization across the region through the Digital Single Market (DSM). The DSM is an ongoing effort to unify the EU market, facilitate trade, and drive economic growth. The DSM's three pillars revolve around better online access to cross-border digital goods and services; a regulatory environment supporting investment and fair competition; and driving growth through investment in infrastructure, human capital, research, and innovation. Among its initiatives is a mandate to allow cross-border flows for nonpersonal data within the EU (with limited exceptions), but not necessarily externally.

China

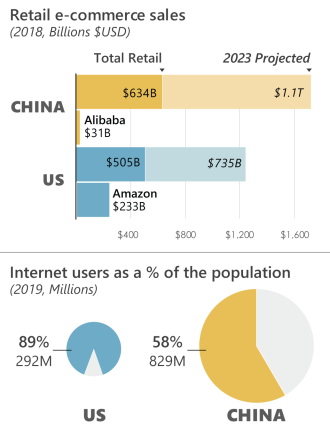

China presents a number of significant opportunities and challenges for the United States in digital trade. The modernization of the Chinese economy, coupled with a large and increasingly prosperous population, has led to a surge in the number of Chinese Internet users and made China a major source of global ecommerce. China's internet users grew from 21.5 million in 2000 to 829 million as of March 2019, and this trend will likely continue, given China's relatively low internet penetration rate (see Figure 7.)115 China's online retail sales in 2018 totaled $1.1 trillion (more than double the U.S. level at $505 billion) and were the world's largest.116 E-Marketer predicts that China's e-commerce retail sales will reach $1.99 trillion in 2019, accounting for 35.3% of total sales and 55.8% of global online sales.117

|

|

Source: U.N. population statistics, Statista.com, Internetworldstats.com. |

U.S. firms may benefit from expanding digital trade in China, but they may also face numerous challenges in the Chinese market. The USTR's 2019 report on foreign trade barriers included a digital trade fact sheet that cited countries and practices of "key concern."118 Three Chinese digital policies were listed, including its restrictions on cross-border data flows and data localization requirements; extensive web filtering and blocking of legitimate sites, including blocks 10 of the top 30 global sites and up to 10,000 sites in total, affecting billions of dollars in potential U.S. business; and cloud computing restrictions and requirements to partner with a Chinese firm to enter the market and to transfer technology and IP to the partner.119

The American Chamber of Commerce in China (AmCham China) 2019 business survey found that 73% of respondents who were engaged in technology and R&D-intensive industries stated that they faced significant or somewhat significant market barriers in China. The lack of sufficient IPR protection (cited by 35% of respondents) and restrictive cybersecurity-related policies (cited by 27% of respondents) ranked among the top three factors prohibiting firms from increasing innovation activities in China. The survey reflected significant concerns by member firms over eight Chinese ICT policies and restrictions (such as internet restrictions and censorship, IPR theft, and data localization requirements), with 72% to 88% of respondents stating that such measures impacted their competiveness and operations in China either somewhat or severely (see Table 1).

Table 1. AmCham China Business Survey: Percent of Respondents who said

Certain Chinese IT Policies Affected their Operations and

Competitiveness in China Somewhat or Severely

|

IT-related issues and practices |

% of respondents |

|

Slow cross border internet speed |

88 |

|

Restricted access to online tools such as software |

86 |

|

Cross-border internet access by virtual private networks (VPN) |

83 |

|

Data security/IP leakage |

79 |

|

Cybersecurity rules protecting critical information infrastructure/important data |

75 |

|

Data privacy regulations |

75 |

|

Internet censorship and restrictions on information publishing/sharing |

73 |

|

Data localization requirements |

72 |

Source: 2019 AmCham China Business Survey.

A Digital Trade Restrictiveness Index (DTRI) of 65 economies created by the European Centre for International Political Economy found China to have the most restrictive digital policies, followed by Russia, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam.120 The index report noted:

China applies the most restrictive digital trade measures in many areas, including public procurement, foreign investment, Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs), competition policy, intermediary liability, content access and standards. The restrictions do not only impose higher costs for trading digital goods and services, they can also block digital trade altogether in certain sectors. In addition, China's data policies are extremely burdensome for companies, and the country also applies some quantitative trade restrictions and restrictions on e-commerce.121

Internet Governance and the Concept of "Internet Sovereignty"

The Chinese government has sought to advance its views on how the internet should be expanded to promote trade, but also to set guidelines and standards over the rights of governments to regulate and control the internet, a concept it has termed "Internet Sovereignty."122 The Chinese government appears to have first advanced a policy of "Internet Sovereignty" around June 2010 when it issued a White Paper titled "the Internet of China," which stated the following:

Within Chinese territory the Internet is under the jurisdiction of Chinese sovereignty. The Internet sovereignty of China should be respected and protected. Citizens of the People's Republic of China and foreign citizens, legal persons and other organizations within Chinese territory have the right and freedom to use the Internet; at the same time, they must obey the laws and regulations of China and conscientiously protect Internet security.123

In 2014, the Chinese government established the Central Internet Security and "Informatization" Leading Group, headed by Chinese president Xi Jinping, to "strengthen China's Internet security and build a strong cyberpower." A year later, President Xi addressed an internet conference, stating "we should respect the right of individual countries to independently choose their own path of cyber development, model of cyber regulation and Internet public policies, and participate in international cyberspace governance on an equal footing."124

Some analysts contend that China's internet sovereignty initiative represents an assertion that the government has the right to fully control the internet within China. Some see this as an attempt by the government to control information that is deemed a threat to social stability, in violation of the right to freedom of speech, which is guaranteed in China's Constitution. Other critics of China's internet sovereignty policy view it as an attempt by the government to limit market access by foreign internet, digital, and high technology firms in China, in order to boost Chinese firms and reduce China's dependence on foreign technology.

Cyber-Theft of U.S. Trade Secrets

China is considered by most analysts to be the largest source of global theft of IP and a major source of cybertheft of U.S. trade secrets, including by government entities. To illustrate, a 2011 report by the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) stated: "Chinese actors are the world's most active and persistent perpetrators of economic espionage. U.S. private sector firms and cybersecurity specialists have reported an onslaught of computer network intrusions that have originated in China, but the IC (Intelligence Community) cannot confirm who was responsible." The report goes on to warn that

China will continue to be driven by its longstanding policy of "catching up fast and surpassing" Western powers. The growing interrelationships between Chinese and U.S. companies—such as the employment of Chinese-national technical experts at U.S. facilities and the off-shoring of U.S. production and R&D to facilities in China—will offer Chinese government agencies and businesses increasing opportunities to collect sensitive US economic information.125

In May 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice issued a 31-count indictment against five members of the People's Liberation Army for cyber-espionage and other offenses that allegedly targeted five U.S. firms and a labor union for commercial advantage, the first time the Federal government had initiated such action against state actors.126

In April 2015, President Obama issued Executive Order 13964 authorizing certain sanctions against "persons engaging in significant malicious cyber-enabled activates."127 This led to China sending a high-level delegation to Washington, DC, and, on September 25, 2015, Presidents Obama and Xi announced that they had reached an agreement on cyber-security and trade secrets that stated that neither country's government "will conduct or knowingly support cyber-enabled theft of IP, including trade secrets or other confidential business information, with the intent of providing competitive advantages to companies or commercial sectors."128 Specifically, the two sides agreed to

- Not conduct or knowingly support cyber-enabled theft of IP, including trade secrets or other confidential business information, with the intent of providing competitive advantages to companies or commercial sectors;

- Establish a high-level joint dialogue mechanism on fighting cybercrime and related issues;

- Work together to identify and promote appropriate norms of state behavior in cyberspace internationally; and

- Provide timely responses to requests for information and assistance concerning malicious cyber activities.129

The two sides also agreed to set up a high-level dialogue mechanism (which would take place twice a year) to address cybercrime and improve two-way communication when cyber-related concerns arise (including the creation of a hotline). The first meeting of the U.S.-China High-Level Joint Dialogue on Cybercrime and Related Issues was held in December 2015. China and the United States reached agreement on a document establishing guidelines for requesting assistance on cybercrime or other malicious cyber activities and for responding to such requests. Two more meetings were held in 2016. The dialogue was continued in October 2017 under the Trump Administration.130 The Administration's Section 301 trade dispute between the United States and China may have led to a suspension of the dialogue (see below).131

It is difficult to assess the effectiveness of the September 2015 U.S.-China cyber agreement in reducing the level of Chinese cyber intrusions against U.S. entities seeking to steal trade secrets as no official U.S. statistics on such activities are publicly available. In August 2018, the U.S. Deputy Director of the Cyber Threat Intelligence Integration Center stated that "the intelligence community and private-sector security experts continue to identify ongoing cyber activity from China, although at volumes significantly lower than before the bilateral U.S.-China cyber commitments of September 2015."132 In October 2018, CrowdStrike, a U.S. cybersecurity technology company, identified China as "the most prolific nation-state threat actor during the first half of 2018."133 It found that Chinese entities had made targeted intrusion attempts against multiple sectors of the economy. In December 2018, U.S. Assistant Attorney General John C. Demers stated at a Senate hearing that from 2011-2018, China was linked to more than 90% of the Justice Department's cases involving economic espionage and two-thirds of its trade secrets cases.134

Cybersecurity Laws

According to the USTR's 2017 report on China's WTO accession, China has not fulfilled all of its WTO market opening commitments. The USTR cited "significant declines in commercial sales of foreign ICT products and services in China," as evidence that China continued to maintain "mercantilist policies under the guise of cybersecurity."135

The Chinese government pledged not to use recently enacted cyber and national security laws and regulations to unfairly burden foreign ICT firms, or to discriminate against foreign ICT firms in the implementation of various policy initiatives to promote indigenous innovation in China. Some Chinese laws or proposals include language stating that critical information infrastructure should be "secure and controllable," an ambiguous term that has not been precisely defined by Chinese authorities. Other proposals of concern to U.S. firms appear to lay out policies that would require foreign ICT firms to hand over proprietary information.

Examples of measures of concern to foreign ICT firms include

- Cybersecurity Law, passed by the government on November 7, 2016 (effective June 1, 2017), ascertains the principles of cyberspace sovereignty;136 defines the security-related obligations of network product and service providers; further enhances the rules for protection of personal information; establishes a framework of security protection for "critical information infrastructure"; and establishes regulations pertaining to cross-border transmissions of important data by critical information infrastructure.137

Some analysts have expressed concerns that one of the main goals of the new law is to promote the development of indigenous technologies and impose restrictions on foreign firms, and many multinational companies continue to voice concerns about the lack of clarity of the law's requirements, how the law will be interpreted and implemented through subsequent regulations, and to what extent it will impact their operations in China. - National Security Law, enacted in July 2015, emphasizes the state's role in driving innovation and reviewing "foreign commercial investment, special items and technologies, internet information technology products and services, projects involving national security matters, as well as other major matters and activities, that impact or might impact national security."138

Such restrictions could have a significant impact on U.S. ICT firms. According to BEA, U.S. exports of ICT services and potentially ICT-enabled services (i.e., services that are delivered remotely over ICT networks) to China totaled $18.7 billion in 2017.139

Section 301 Action against China over Intellectual Property and Innovation Issues

Concerns over China's policies on IP, technology, and innovation policies led the Trump Administration, in August 2017, to launch a Section 301 investigation of those policies.140 On March 22, 2018, President Trump signed a Memorandum on Actions by the United States Related to the Section 301 Investigation that identified four broad IPR-related policies that justified U.S. action under Section 301, stating that China

- 1. Uses joint venture requirements, foreign investment restrictions, and administrative review and licensing processes to force or pressure technology transfers from American companies;

- 2. Uses discriminatory licensing processes to transfer technologies from U.S. companies to Chinese companies;

- 3. Directs and facilitates investments and acquisitions which generate large-scale technology transfer; and

- 4. Conducts and supports cyberintrusions into U.S. computer networks to gain access to valuable business information.

The USTR estimates such policies cost the U.S. economy at least $50 billion annually. Under the Section 301 action, the Administration proposed to (1) implement 25% ad valorem tariffs on certain Chinese imports (which in sum are comparable to U.S. trade losses); (2) initiate a WTO dispute settlement case against China's "discriminatory" technology licensing (which it did on March 23, 2018); and (3) propose new investment restrictions on Chinese efforts to acquire sensitive U.S. technology.141 The Administration did not act on the last issue after Congress passed the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA) (P.L. 115-232) in August 2018 to modernize the existing U.S. review process of foreign investments in terms of national security. Among its changes, FIRRMA expanded the types of investment subject to review, including certain noncontrolling investments in "critical technology."142

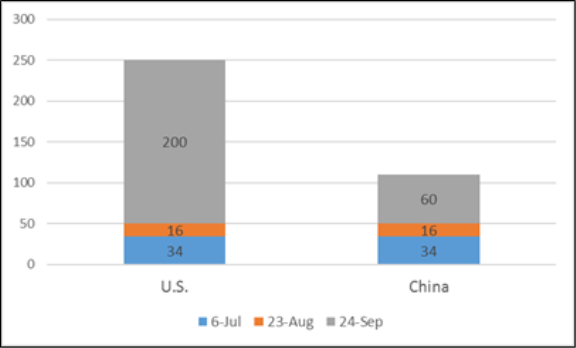

The Trump Administration subsequently imposed tariff hikes on $250 billion worth of imports from China in three separate stages in 2018, while China increased tariffs on $110 billion worth of imports from the United States (See Figure 8).143 In May 2019, the United States increased the tariff levels on the third tranche of products imported from China. China subsequently increased its tariff levels on its third tranche.

|

Figure 8. Three Rounds of U.S.-China Tariff Hikes in 2018 Estimated Value of Goods Impacted ($billions) and effective dates |

|

|

Source: USTR and Chinese Ministry of Commerce. Notes: Tariff rates vary. |

Digital Trade Provisions in Trade Agreements

As the above analysis of EU and China policies demonstrates, there is not a single set of international rules or disciplines that govern key digital trade issues, and the topic is treated inconsistently, if at all, in trade agreements. As digital trade has emerged as an important component of trade flows, it has risen in significance on the U.S. trade policy agenda and that of other countries.

Given the stalemate in comprehensive WTO multilateral negotiations, trade agreements have not kept pace with the complexities of the digital economy and digital trade is treated unevenly in existing WTO agreements. More recent bilateral and plurilateral deals have started to address digital trade policies and barriers more comprehensively. The use of digital trade provisions in bilateral and plurilateral trade negotiations may help spur interest in the creation of future WTO frameworks that focus on digital trade and provide input for ongoing plurilateral negotiations occurring in the aegis of the WTO (see below).

WTO Provisions

While no comprehensive agreement on digital trade exists in the WTO, other WTO agreements cover some aspects of digital trade and new plurilateral negotiations may set new rules and disciplines.

General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)

The WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) entered into force in January 1995, predating the current reach of the internet and the explosive growth of global data flows. GATS includes obligations on nondiscrimination and transparency that cover all service sectors. The market access obligations under GATS, however, are on a "positive list" basis in which each party must specifically opt in for a given service sector to be covered.144

As GATS does not distinguish between means of delivery, trade in services via electronic means is covered under GATS. While GATS contains explicit commitments for telecommunications and financial services that underlie e-commerce, digital trade and information flows and other trade barriers are not specifically included. Given the positive list approach of GATS, coverage across members varies and many newer digital products and services did not exist when the agreements were negotiated. To address advances in technology and services, the Committee on Specific Commitments is examining how certain new online services, such as platform services, or specific regulations, such as data localization, could be classified and scheduled within GATS.145

Declaration on Global Electronic Commerce

In May 1998, WTO members established the "comprehensive" Work Programme on Electronic Commerce and established a temporary customs duties moratorium on electronic transmission that has been extended multiple times.146 While multiple members submitted proposals to advance multilateral digital trade negotiations under the Work Programme, no clear path forward was identified.

Information Technology Agreement (ITA)

The WTO Information Technology Agreement (ITA) aims to eliminate tariffs on the goods that power and utilize the internet, lowering the costs for companies to access technology at all points along the value chain. Originally concluded in 1996, the ITA was expanded to further cut tariffs beginning in July 2016. The expanded ITA is a plurilateral agreement among 54 developed and developing WTO members who account for over 90% of global trade in these goods. Some WTO members, such as Vietnam and India, are party to the original ITA, but did not join the expanded agreement. Like the original ITA, the benefits of the expanded agreement will be extended on a most-favored nation (MFN) basis to all WTO members.

Under the expanded ITA, the parties agreed to review the agreement's scope in the future to determine if additional product coverage is warranted as technology evolves. While the WTO ITA has expanded trade in the technology products that underlie digital trade, it does not tackle the nontariff barriers that can pose significant limitations.

Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS)

The TRIPS Agreement, in effect since January 1, 1995, provides minimum standards of IPR protection and enforcement. The TRIPS Agreement does not specifically cover IPR protection and enforcement in the digital environment, but arguably has application to the digital environment and sets a foundation for IPR provisions in subsequent U.S. trade negotiations and agreements, many of which are "TRIPS-plus."

The TRIPS Agreement covers copyrights and related rights (i.e., for performers, producers of sound recordings, and broadcasting organizations), trademarks, patents, trade secrets (as part of the category of "undisclosed information"), and other forms of IP. It builds on international IPR treaties, dating to the 1800s, administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization, or WIPO (see below). TRIPS incorporates the main substantive provisions of WIPO conventions by reference, making them obligations under TRIPS. WTO members were required to fully implement TRIPS by 1996, with exceptions for developing country members by 2000 and least-developed-country (LDC) members until July 1, 2021, for full implementation.147

TRIPS aims to balance rights and obligations between protecting private rights holders' interests and securing broader public benefits. Among its provisions, the TRIPS section on copyright and related rights includes specific provisions on computer programs and compilations of data. It requires protections for computer programs—whether in source or object code—as literary works under the WIPO Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (Berne Convention). TRIPS also clarifies that databases and other compilations of data or other material, whether in machine readable form or not, are eligible for copyright protection even when the databases include data not under copyright protection.148

Like the GATS, TRIPS predates the era of ubiquitous internet access and commercially significant e-commerce. TRIPS includes a provision for WTO members to "undertake reviews in the light of any relevant new developments which might warrant modification or amendment" of the agreement. The TRIPS Council has engaged in discussions on the agreement's relationship to electronic commerce as part of the WTO Work Programme on Electronic Commerce, focusing on protection and enforcement of copyright and related rights, trademarks, and new technologies and access to these technologies; new activity by the TRIPS Council to this end appears to be limited in recent years.149

World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Internet Treaties

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) has been a primary forum to address IP issues brought on by the digital environment since the TRIPS Agreement. The WIPO Copyright Treaty and WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty—often referred to jointly as the WIPO "Internet Treaties"—established international norms regarding IPR protection in the digital environment. These treaties were agreed to in 1996 and entered into force in 2002, but are not enforceable, including under WTO dispute settlement. Shaped by TRIPS, the WIPO Internet Treaties are intended to clarify that existing rights continue to apply in the digital environment, to create new online rights, and to maintain a fair balance between the owners of rights and the general public.150