Introduction

Medicare is a federal program that pays for covered health care services of qualified beneficiaries. It was established in 1965 under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act to provide health insurance to individuals 65 and older, and has been expanded over the years to include permanently disabled individuals under 65. The program is administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).1

Medicare consists of four distinct parts:

- Part A (Hospital Insurance, or HI) covers inpatient hospital services, skilled nursing care, hospice care, and some home health services. The HI trust fund is mainly funded by a dedicated payroll tax of 2.9% of earnings, shared equally between employers and workers. Since 2013, workers with income of more than $200,000 per year for single tax filers (or more than $250,000 for joint tax filers) pay an additional 0.9% on income over those amounts.

- Part B (Supplementary Medical Insurance, or SMI) covers physician services, outpatient services, and some home health and preventive services. The SMI trust fund is funded through beneficiary premiums (set at 25% of estimated program costs for the aged) and general revenues (the remaining amount, approximately 75%).

- Part C (Medicare Advantage, or MA) is a private plan option for beneficiaries that covers all Parts A and B services, except hospice. Individuals choosing to enroll in Part C must also enroll in Part B. Part C is funded through the HI and SMI trust funds.

- Part D covers outpatient prescription drug benefits. Funding is included in the SMI trust fund and is financed through beneficiary premiums, general revenues, and state transfer payments.

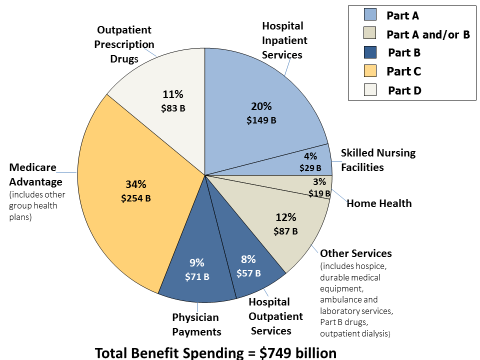

Medicare serves approximately one in six Americans and virtually all of the population aged 65 and older.2 In 2019, the program will cover an estimated 61 million persons (52 million aged and 9 million disabled).3 The Congressional Budget Office (CBO)4 estimates that total Medicare spending in 2019 will be about $772 billion; of this amount, approximately $749 billion will be spent on benefits.5 About 28% of Medicare benefit spending is for hospital inpatient and hospital outpatient services (see Figure 1). CBO also estimates that federal Medicare spending (after deduction of beneficiary premiums and other offsetting receipts) will be about $637 billion in 2019, accounting for about 14% of total federal spending and 3% of GDP.6 Medicare is required to pay for all covered services provided to eligible persons, so long as specific criteria are met. Spending under the program (except for a portion of administrative costs) is considered mandatory spending and is not subject to the appropriations process.

Medicare is expected to be a high-priority issue in the current Congress. The program has a significant impact on beneficiaries and other stakeholders as well as on the economy in general through its coverage of important health care benefits for the aged and disabled, the payment of premiums and other cost sharing by those beneficiaries, its payments to providers who supply those health care services, and its interaction with other insurance coverage. Projections of future Medicare expenditures and funding indicate that the program will place increasing financial demands on the federal budget and on beneficiaries. In response to these concerns, Congress may consider a range of Medicare reform options, from making changes within the current structure, including modifying provider payments and revising existing oversight and regulatory mechanisms, to restructuring the entire program. The committees of jurisdiction for the mandatory spending (benefits) portion of Medicare are the Senate Committee on Finance, the House Committee on Ways and Means, and the House Committee on Energy and Commerce. The House and Senate Committees on Appropriations have jurisdiction over the discretionary spending used to administer and oversee the program.

Medicare History

Medicare was enacted in 1965 (P.L. 89-97) in response to the concern that only about half of the nation's seniors had health insurance, and most of those had coverage only for inpatient hospital costs. The new program, which became effective July 1, 1966, included Part A coverage for hospital and posthospital services and Part B coverage for doctors and other medical services. As is the case for the Social Security program, Part A is financed by payroll taxes levied on current workers and their employers; persons must pay into the system for 40 quarters to become entitled to premium-free benefits. Medicare Part B is voluntary, with a monthly premium required of beneficiaries who choose to enroll. Payments to health care providers under both Part A and Part B were originally based on the most common form of payment at the time, namely "reasonable costs" for hospital and other institutional services or "usual, customary and reasonable charges"7 for physicians and other medical services.

Medicare is considered a social insurance program and is the second-largest such federal program, after Social Security. The 1965 law also established Medicaid, the federal/state health insurance program for the poor; this was an expansion of previous welfare-based assistance programs. Some low-income individuals qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid.

In the ensuing years, Medicare has undergone considerable change. P.L. 92-603, enacted in 1972, expanded program coverage to certain individuals under 65 (the disabled and persons with end-stage renal disease (ESRD)),8 and introduced managed care into Medicare by allowing private insurance entities to provide Medicare benefits in exchange for a monthly capitated payment. This law also began to place limitations on the definitions of reasonable costs and charges in order to gain some control over program spending which, even initially, exceeded original projections.

During the 1980s and 1990s, a number of laws were enacted that included provisions designed to further stem the rapid increase in program spending through modifications to the way payments to providers were determined, and to postpone the insolvency of the Medicare Part A trust fund. This was typically achieved through tightening rules governing payments to providers of services and limiting the annual updates in such payments. The program moved from payments based on reasonable costs and reasonable charges to payment systems under which a predetermined payment amount was established for a specified unit of service. At the same time, beneficiaries were given expanded options to obtain covered services through private managed care arrangements, typically health maintenance organizations (HMOs). Most Medicare payment provisions were incorporated into larger budget reconciliation bills designed to control overall federal spending.

This effort culminated in the enactment of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA 97; P.L. 105-33).9 This law slowed the rate of growth in payments to providers and established new payment systems for certain categories of providers, including establishing the sustainable growth rate (SGR) methodology for determining the annual update to Medicare physician payments. It also established the Medicare+Choice program, which expanded private plan options for beneficiaries and changed the way most of these plans were paid. BBA 97 further expanded preventive services covered by the program.

Subsequently, Congress became concerned that the BBA 97 cuts in payments to providers were somewhat larger than originally anticipated. Therefore, legislation was enacted in both 1999 (Balanced Budget Refinement Act of 1999, or BBRA; P.L. 106-113) and 2000 (Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP Benefits Improvement and Protection Act of 2000, or BIPA; P.L. 106-554) to mitigate the impact of BBA 97 on providers.

In 2003, Congress enacted the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA; P.L. 108-173),10 which included a major benefit expansion and placed increasing emphasis on the private sector to deliver and manage benefits. The MMA included provisions that (1) created a new voluntary outpatient prescription drug benefit to be administered by private entities; (2) replaced the Medicare+Choice program with the Medicare Advantage (MA) program and raised payments to plans in order to increase their availability for beneficiaries; (3) introduced the concept of income testing into Medicare, with higher-income persons paying larger Part B premiums beginning in 2007;11 (4) modified some provider payment rules; (5) expanded covered preventive services; and (6) created a specific process for overall program review if general revenue spending exceeded a specified threshold.12

During the 109th Congress, two laws were enacted that incorporated minor modifications to Medicare's payment rules. These were the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA; P.L. 109-171) and the Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 (TRHCA; P.L. 109-432). In the 110th Congress, additional changes were incorporated in the Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP Extension Act of 2007 (MMSEA; P.L. 110-173)13 and the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008 (MIPPA; P.L. 110-275).14

In the 111th Congress, comprehensive health reform legislation was enacted that, among other things, made statutory changes to the Medicare program. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148), enacted on March 23, 2010, included numerous provisions affecting Medicare payments, payment rules, covered benefits, and the delivery of care. The Health Care and Education Affordability Reconciliation Act of 2010 (the Reconciliation Act, or HCERA; P.L. 111-152), enacted on March 30, 2010, made changes to a number of Medicare-related provisions in the ACA and added several new provisions.15 Included in the ACA, as amended, are provisions that (1) constrain Medicare's annual payment increases for certain providers; (2) change payment rates in the MA program so that they more closely resemble those in fee-for-service; (3) reduce payments to hospitals that serve a large number of low-income patients; (4) create an Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB) to make recommendations to adjust Medicare payment rates;16 (5) phase out the Part D prescription drug benefit "doughnut hole"; (6) increase resources and enhance activities to prevent fraud and abuse; and (7) provide incentives to increase the quality and efficiency of care, such as creating value-based purchasing programs for certain types of providers, allowing accountable care organizations (ACOs) that meet certain quality and efficiency standards to share in the savings,17 creating a voluntary pilot program that bundles payments for physician, hospital, and post-acute care services,18 and adjusting payments to hospitals for readmissions related to certain potentially preventable conditions.

In the 112th and 113th Congresses, the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240), the Continuing Appropriations Resolution of 2014 (P.L. 113-67), and the Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 (PAMA; P.L. 113-93) primarily made short-term modifications to physician payment updates and payment adjustments for certain types of providers. PAMA also established a new skilled nursing facility (SNF) value-based purchasing program and a new system for determining payments for clinical diagnostic laboratory tests. The Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014 (IMPACT; P.L. 113-185) required that post-acute care providers—defined in the law as long-term care hospitals (LTCHs), inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), SNFs, and home health agencies (HHAs)—report standardized patient assessment data and data on quality measures and resource use. IMPACT also modified the annual update to the hospice aggregate payment cap and required that hospices be reviewed every three years to ensure that they are compliant with existing regulations related to patient health and safety and quality of care.

In the 114th Congress, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA; P.L. 114-10) repealed the SGR formula for calculating updates to Medicare payment rates to physicians and other practitioners and established an alternative set of methods for determining the annual updates.19 MACRA also introduced alternatives to the current fee-for-service (FFS) based physician payments by creating a new merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS) and put in place processes for developing, evaluating, and adopting alternative payment models (APMs). Additionally, MACRA reduced updates to hospital and post-acute care provider payments, extended several expiring provider payment adjustments, made adjustments to income-related premiums in Parts B and D, and prohibited using Social Security numbers on beneficiaries' Medicare cards. Among other changes, the Increasing Choice, Access, and Quality in Health Care for Americans Act (Division C of the 21st Century Cures Act; P.L. 114-255) made adjustments to LTCH reimbursement and modified the average length of stay criteria, which determines whether a hospital qualifies as an LTCH. It also delayed payment reductions and required the Secretary of Health and Human Services (the Secretary) to make changes to how payments are determined for certain durable medical equipment, prosthetics, orthotics, and supplies (DMEPOS). Lastly, it allowed beneficiaries with ESRD to enroll in MA beginning January 1, 2021.20

In the 115th Congress, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 18; P.L. 115-123) made a number of changes to federal health care programs, including Medicare.21 For example, BBA 18 included provisions designed to expand care for beneficiaries with chronic health conditions, such as promoting team-based care by providers, increasing the use of telehealth services, and expanding certain MA supplemental benefits. In addition, BBA 18 extended for five years a number of existing Medicare provisions that were set to expire (or that had temporarily expired), including the Medicare dependent hospital program and add-on payments for low-volume hospitals, rural home health services, and certain ambulance services. BBA 18 also specified payment updates for the Medicare physician fee schedule, SNFs, and home health services; reduced payments for non-emergency ambulance transports; and required modification of the home health prospective payment system starting in 2020. In addition, the act provided for indefinite authority for MA special needs plans, repealed limits on outpatient therapy services, and eliminated the IPAB.22 Starting in 2019, the act will require that pharmaceutical manufacturers participating in Medicare Part D provide a larger discount on brand-name drugs purchased by enrollees in the coverage gap and will create a new high-income premium category under Parts B and D.

Eligibility and Enrollment

Most persons aged 65 or older are automatically entitled to premium-free Part A because they or their spouse paid Medicare payroll taxes for at least 40 quarters (about 10 years) on earnings covered by either the Social Security or the Railroad Retirement systems. Persons under the age of 65 who receive cash disability benefits from Social Security or the Railroad Retirement systems for at least 24 months are also entitled to Part A. (Since there is a five-month waiting period for cash payments, the Medicare waiting period is effectively 29 months.)23 The 24-month waiting period is waived for persons with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, "Lou Gehrig's disease"). Individuals of any age with ESRD who receive dialysis on a regular basis or a kidney transplant are generally eligible for Medicare. Medicare coverage for individuals with ESRD usually starts the first day of the fourth month of dialysis treatments. In addition, individuals with one or more specified lung diseases or types of cancer who lived for six months during a certain period prior to diagnosis in an area subject to a public health emergency declaration by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as of June 17, 2009, are also deemed entitled to benefits under Part A and eligible to enroll in Part B.

Persons over the age of 65 who are not entitled to premium-free Part A may obtain coverage by paying a monthly premium ($437 in 2019) or, for persons with at least 30 quarters of covered employment, a reduced monthly premium ($240 in 2019).24 In addition, disabled persons who lose their cash benefits solely because of higher earnings, and subsequently lose their extended Medicare coverage, may continue their Medicare enrollment by paying a premium, subject to limitations.

Generally, enrollment in Medicare Part B is voluntary. All persons entitled to Part A (and persons over the age of 65 who are not entitled to premium-free Part A) may enroll in Part B by paying a monthly premium.25 In 2019, the monthly premium is $135.50; however, about 3.5% of Part B enrollees pay less, due to a "hold-harmless" provision in the Social Security Act.26 Since 2007, higher-income Part B enrollees pay higher premiums. (See "Part B Financing.") Although enrollment in Part B is voluntary for most individuals, in most cases, those who enroll in Part A by paying a premium also must enroll in Part B. Additionally, ESRD beneficiaries and Medicare Advantage enrollees (discussed below) also must enroll in Part B.

Together, Parts A and B of Medicare comprise "original Medicare," which covers benefits on a fee-for-service basis. Beneficiaries have another option for coverage through private plans, called the Medicare Advantage (MA or Part C) program. When beneficiaries first become eligible for Medicare, they may choose either original Medicare or they may enroll in a private MA plan. Each fall, there is an annual open enrollment period during which time Medicare beneficiaries may choose a different MA plan, or leave or join the MA program.27 Beneficiaries are to receive information about their options to help them make informed decisions.28 In 2019, the annual open enrollment period runs from October 15 to December 7 for plan choices starting the following January. Since 2012, MA plans with a 5-star quality rating have been allowed to enroll Medicare beneficiaries who are either in traditional Medicare or in an MA plan with a lower quality rating at any time.

Finally, each individual enrolled in either Part A or Part B is also entitled to obtain qualified prescription drug coverage through enrollment in a Part D prescription drug plan. Similar to Part B, enrollment in Part D is voluntary and the beneficiary pays a monthly premium. Since 2011, some higher-income enrollees pay higher premiums, similar to enrollees in Part B. Generally, beneficiaries enrolled in an MA plan providing qualified prescription drug coverage (MA-PD plan) must obtain their prescription drug coverage through that plan.29

In general, individuals who do not enroll in Part B or Part D during an initial enrollment period (when they first become eligible for Medicare) must pay a permanent penalty of increased monthly premiums if they choose to enroll at a later date. Individuals who do not enroll in Part B during their initial enrollment period may enroll only during the annual general enrollment period, which occurs from January 1 to March 31 each year. Coverage begins the following July 1. However, the law waives the Part B late enrollment penalty for current workers who have primary coverage through their own or a spouse's employer-sponsored plan. These individuals have a special enrollment period once their employment ends; as long as they enroll in Part B during this time, they will not be subject to penalty.30

Individuals who do not enroll in Part D during their initial enrollment period may enroll during the annual open enrollment period, which corresponds with the Part C annual enrollment period—from October 15 to December 7, with coverage effective the following January. Individuals are not subject to the Part D penalty if they have maintained "creditable" drug coverage through another source, such as retiree health coverage offered by a former employer or union. However, once employees retire or have no access to "creditable" Part D coverage, a penalty will apply unless they sign up for coverage during a special enrollment period. Finally, for persons who qualify for the low-income subsidy for Part D, the delayed-enrollment penalty does not apply.

Benefits and Payments

Medicare Parts A, B, and D each cover different services, with Part C providing a private plan alternative for all Medicare services covered under Parts A and B, except hospice. The Parts A-D covered services are described below, along with a description of Medicare's payments.

Part A

Part A provides coverage for inpatient hospital services, posthospital skilled nursing facility (SNF) services, hospice care, and some home health services, subject to certain conditions and limitations. Approximately 20% of fee-for-service enrollees use Part A services during a year.31

Inpatient Hospital Services

Medicare inpatient hospital services include (1) bed and board; (2) nursing services; (3) use of hospital facilities; (4) drugs, biologics, supplies, appliances, and equipment; and (5) diagnostic and therapeutic items and services. (Physicians' services provided during an inpatient stay are paid under the physician fee schedule and discussed below in the "Physicians and Nonphysician Practitioner Services" section.) Coverage for inpatient services is linked to an individual's benefit period or "spell of illness" (defined as beginning on the day a patient enters a hospital and ending when he or she has not been in a hospital or skilled nursing facility for 60 days). An individual admitted to a hospital more than 60 days after the last discharge from a hospital or SNF begins a new benefit period. Coverage in each benefit period is subject to the following conditions:32

- Days 1-60. Beneficiary pays a deductible ($1,364 in 2019).

- Days 61-90. Beneficiary pays a daily co-payment charge ($341 in 2019).

- Days 91-150. After 90 days, the beneficiary may draw on one or more of 60 lifetime reserve days, provided they have not been previously used. (Each of the 60 lifetime reserve days can be used only once during an individual's lifetime.) For lifetime reserve days, the beneficiary pays a daily co-payment charge ($682 in 2019); otherwise the beneficiary pays all costs.

- Days 151 and over. Beneficiary pays for all costs for these days.

Inpatient mental health care in a psychiatric facility is limited to 190 days during a patient's lifetime. Cost sharing is structured similarly to that for stays in a general hospital (above).

Medicare makes payments to most acute care hospitals under the inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS), using a prospectively determined amount for each discharge. Medicare's payments to hospitals is the product of two components: (1) a discharge payment amount adjusted by a wage index for the area where the hospital is located or where it has been reclassified, and (2) the weight associated with the Medicare severity-diagnosis related group (MS-DRG) to which the patient is assigned. This weight reflects the relative costliness of the average patient in that MS-DRG, which is revised annually, generally effective October 1st of each year.

Additional payments are made to hospitals for cases with extraordinary costs (outliers), for indirect costs incurred by teaching hospitals for graduate medical education, and to disproportionate share hospitals (DSH) which provide a certain volume of care to low-income patients. Additional payments may also be made for qualified new technologies that have been approved for special add-on payments.

Medicare also makes payments outside the IPPS system for direct costs associated with graduate medical education (GME) for hospital residents, subject to certain limits. In addition, Medicare pays hospitals for 65% of the allowable costs associated with beneficiaries' unpaid deductible and co-payment amounts as well as for the costs for certain other services.

IPPS payments may be reduced by certain quality-related programs based on a hospital's quality performance. These quality-related programs include the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program, and the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program. Further, hospitals may receive Medicare payment reductions for failing to demonstrate meaningful use of certified electronic health record (EHR) technology.

Additional payment adjustments or special treatment under the IPPS may apply for hospitals meeting one of the following designations: (1) sole community hospitals (SCHs), (2) Medicare dependent hospitals, (3) rural referral centers, and (4) low-volume hospitals.

Certain hospitals or distinct hospital units are exempt from IPPS and paid on an alternative basis,33 including (1) inpatient rehabilitation facilities, (2) long-term care hospitals, (3) psychiatric facilities including hospitals and distinct part units, (4) children's hospitals, (5) cancer hospitals, and (6) critical access hospitals.

Skilled Nursing Facility Services

Medicare covers up to 100 days of posthospital care for persons needing skilled nursing or rehabilitation services on a daily basis.34 The SNF stay must be preceded by an inpatient hospital stay of at least 3 consecutive calendar days, and the transfer to the SNF typically must occur within 30 days of the hospital discharge. Medicare requires SNFs to provide services for a condition the beneficiary was receiving treatment for during his or her qualifying hospital stay (or for an additional condition that arose while in the SNF). There is no beneficiary cost sharing for the first 20 days of a Medicare-covered SNF stay. For days 21 to 100, beneficiaries are subject to daily co-payment charges ($170.50 in 2019).35 The 100-day limit begins again with a new spell of illness.

SNF services are paid under a prospective payment system (PPS), which is based on a per diem urban or rural base payment rate, adjusted for case mix (average severity of illness) and area wages. The per diem rate generally covers all services, including room and board, provided to the patient that day. The case-mix adjustment is made using the resource utilization groups (RUGs) classification system, which uses patient assessments to assign a beneficiary to one of 66 groups that reflect the beneficiary's expected use of services. Patient assessments are done at various times during a patient's stay and a beneficiary's designated RUG category can change with changes in the beneficiary's condition. Extra payments are not made for extraordinarily costly cases ("outliers").36

Hospice Care

The Medicare hospice benefit covers services designed to provide palliative care and management of a terminal illness; the benefit includes drugs and medical and support services. These services are provided to Medicare beneficiaries with a life expectancy of six months or less for two 90-day periods, followed by an unlimited number of 60-day periods. The individual's attending physician and the hospice physician must certify the need for the first benefit period, but only the hospice physician needs to recertify for subsequent periods. Since January 1, 2011, a hospice physician or nurse practitioner must have a face-to-face encounter with the individual to determine continued eligibility prior to the 180th day recertification, and for each subsequent recertification. Hospice care is provided in lieu of most other Medicare services related to the curative treatment of the terminal illness. Beneficiaries electing hospice care from a hospice program may receive curative services for illnesses or injuries unrelated to their terminal illness, and they may disenroll from the hospice at any time. Nominal cost sharing is required for drugs and respite care.

Payment for hospice care is based on one of four prospectively determined rates (which correspond to four different levels of care) for each day a beneficiary is under the care of the hospice. The four rate categories are routine home care,37 continuous home care, inpatient respite care, and general inpatient care. Payment rates are adjusted to reflect differences in area wage levels, using the hospital wage index. Payments to a hospice are limited by two caps; the first limits the number of days of inpatient care to 20% or less of total patient care days, and the second limits the average annual payment per beneficiary.38

Parts A and B

Home health services and services for individuals with end-stage renal disease are covered under both Parts A and B of Medicare.

Home Health Services

Medicare covers visits by participating home health agencies for beneficiaries who (1) are confined to home and (2) need either skilled nursing care on an intermittent basis or physical or speech language therapy. After establishing such eligibility, the continuing need for occupational therapy services may extend the eligibility period. Covered services include part-time or intermittent nursing care, physical or occupational therapy or speech language pathology services, medical social services, home health aide services, and medical supplies and durable medical equipment. The services must be provided under a plan of care established by a physician, and the plan must be reviewed by the physician at least every 60 days. There is no beneficiary cost sharing for home health services (though some other Part B services provided in connection with the visit, such as durable medical equipment, may be subject to cost-sharing charges).

Home health services are covered under both Medicare Parts A and B. There are special eligibility requirements and benefit limits for home health services furnished under Part A to beneficiaries who are enrolled in both Parts A and B. For such a beneficiary, Part A pays for only postinstitutional home health services furnished for up to 100 visits during a spell of illness,39 while Part B covers any medically necessary home health services that exceed the 100-visit limit, as well as medically necessary home health services that do not qualify as "postinstitutional."

For beneficiaries enrolled in only Part A or only Part B, the requirements described above do not apply. Part A or Part B, as applicable, covers all medically necessary episodes of home health care, without a visit limit, regardless of whether the episode follows a hospitalization. Regardless of whether the beneficiary is enrolled in Part A only, in Part B only, or in both parts, the scope of the Medicare home health benefit is the same, Medicare's payments to HHAs are calculated using the same methods, and beneficiaries have no cost-sharing. Home health services are paid under a home health PPS, based on 60-day episodes of care; a patient may have an unlimited number of episodes.40 The physician's certification of an initial 60-day episode of home health must be supported by a face-to-face encounter with the patient related to the primary reason that the patient needs home health services. Under the PPS, for episodes with five or greater visits, a nationwide base payment amount is adjusted by differences in wages (using the hospital wage index). This amount is then adjusted for case mix using the applicable Home Health Resource Group (HHRG) to which the beneficiary has been assigned. The HHRG applicable to a beneficiary is determined following an assessment of the patient's condition and care needs using the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS); there are 153 HHRGs. For episodes with four or fewer visits, the PPS reimburses the provider for each visit performed. Further payment adjustments may be made for services provided in rural areas, outlier visits (for extremely costly patients), a partial episode for beneficiaries that have an intervening event during their episode, or an agency's failure to submit quality data to CMS.

Since January 1, 2016, home health agencies in nine states are being reimbursed under a home health value-based purchasing (HHVBP) model.41 These home health agencies can receive increased or decreased home health reimbursements depending on their performance across certain quality measures.

End-Stage Renal Disease

Individuals with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are eligible for all services covered under Parts A and B.42 Kidney transplantation services, to the extent they are inpatient hospital services, are subject to the inpatient hospital PPS and are reimbursed by both Parts A and B. However, kidney acquisition costs are paid on a reasonable cost basis under Part A. Dialysis treatments, when an individual is admitted to a hospital, are covered under Part A. Part B covers their dialysis services,43 drugs, biologicals (including erythropoiesis stimulating agents used in treating anemia as a result of ESRD), diagnostic laboratory tests, and other items and services furnished to individuals for the treatment of ESRD.

In effect since January 1, 2011, the ESRD prospective payment system (PPS) makes no payment distinction as to the site where renal dialysis services are provided. With the implementation of the ESRD PPS, Medicare dialysis payments provide a single "bundled" payment for Medicare renal dialysis services that includes (1) items and services included in the former payment system's base rate as of December 31, 2010; (2) erythropoiesis stimulating agents (ESAs) for the treatment of ESRD; (3) other drugs and biologicals for which payment was made separately (before bundling); and (4) diagnostic laboratory tests and other items and services furnished to individuals for the treatment of ESRD. The system is case-mix adjusted based on factors such as patient weight, body mass index, comorbidities, length of time on dialysis, age, race, ethnicity, and other appropriate factors as determined by the Secretary. Under the ESRD Quality Incentive Program, dialysis facilities that fail to meet certain performance standards receive reduced payments.

Part B

Medicare Part B covers physicians' services, outpatient hospital services, durable medical equipment, and other medical services. Initially, over 98% of the eligible population voluntarily enrolled in Part B, but in recent years the percentage has fallen to about 91%.44 About 89% of enrollees in original (FFS) Medicare use Part B services during a year.45 The program generally pays 80% of the approved amount (most commonly, a fee schedule or other predetermined amount) for covered services in excess of the annual deductible ($185 in 2019). The beneficiary is liable for the remaining 20%.

Most providers and practitioners are subject to limits on amounts they can bill beneficiaries for covered services. For example, physicians and some other practitioners may choose whether or not to accept "assignment" on a claim. When a physician signs a binding agreement to accept assignment for all Medicare patients, the physician accepts the Medicare payment amount as payment in full and can bill the beneficiary only the 20% coinsurance plus any unmet deductible. The physician agrees to accept assignment on all Medicare claims in a given year and is referred to as a "participating physician." There are several advantages to being a participating provider, including higher payment under the Medicare fee schedule, a lower beneficiary co-payment, and automatic forwarding of Medigap claims.

Physicians who do not agree to accept assignment on all Medicare claims in a given year are referred to as nonparticipating physicians. Nonparticipating physicians may or may not accept assignment for a given service. If they do not, they may charge beneficiaries more than the fee schedule amount on nonassigned claims; however, these "balance billing" charges are subject to certain limits.46 Alternatively, physicians may choose not to accept any Medicare payment and enter into private contracts with their patients where no Medicare restrictions on payment or balance billing apply; however, this requires that physicians "opt out" of Medicare for two years.47

For some providers, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, assignment is mandatory; these providers can only bill the beneficiary the 20% coinsurance and any unmet deductible. For other Part B services, such as durable medical equipment, assignment is optional; for these services, applicable providers may bill beneficiaries for amounts above Medicare's recognized payment level and may do so without limit.48

Physicians and Nonphysician Practitioner Services

Medicare Part B covers medically necessary physician services and medical services provided by some nonphysician practitioners. Covered nonphysician practitioner services include, but are not limited to, those provided by physician assistants, nurse practitioners, certified registered nurse anesthetists, and clinical social workers. Certain limitations apply for services provided by chiropractors and podiatrists. Beneficiary cost sharing is typically 20% of the approved amount, although most preventive services require no coinsurance from the beneficiary.

A number of Part B services are paid under the Medicare physician fee schedule (MPFS), including services of physicians, nonphysician practitioners, and therapists. There are over 7,000 service codes under the MPFS.

The fee schedule assigns relative values to each service code. These relative values reflect physician work (based on time, skill, and intensity involved), practice expenses (e.g., overhead and nonphysician labor), and malpractice expenses. The relative values are adjusted for geographic variations in the costs of practicing medicine. These geographically adjusted relative values are converted into a dollar payment amount by a national conversion factor. Annual updates to payments are determined through changes in the conversion factor.

MACRA made several fundamental changes to how Medicare pays for physician and practitioner services by (1) changing the methodology for determining the annual updates to the conversion factor, (2) establishing a merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS) to consolidate and replace several existing incentive programs and to apply value and quality adjustments to the MPFS, and (3) establishing the development of, and participation in, alternative payment models (APMs). Prior to MACRA, the SGR system, which had been in place since BBA 97, tied annual updates to the Medicare fee schedule to cumulative Part B expenditure targets.49 MACRA repealed the SGR methodology, established annual fee schedule updates in the short term, and put in place a new method for determining updates thereafter. As a result of the MACRA changes, the update to physician payments under the MPFS was 0% from January 2015 through June 2015; for the remainder of that year—July 2015 through December 2015—the payments were increased by 0.5%. In each of the next four years, 2016 through 2019, the payments were to increase by 0.5% each year; however, the BBA 18 reduced the 2019 update to 0.25%. For the next six years, from 2020 through 2025, the payment update will be 0%.

In addition to changes to the annual update, MACRA established two pathways for payment reform, collectively referred to as the Quality Payment Program (QPP). Medicare payment to all physicians and other practitioners will be determined by which conditions of the QPP, either MIPS or APM, the participant satisfies. The MIPS is a new program that remains based on FFS rates but combines four categories of performance measures (quality of care, cost/resource use, clinical practice improvement activities, and promoting interoperability) into a single adjustment to the base MPFS payment.50 Following several years of data collection and feedback on measures, the MIPS adjustments will affect actual payments for the first time in 2019.

In contrast, qualified advanced APMs51 are intended to be alternatives to FFS, incorporating new approaches to paying for medical care that reward quality and efficiency while de-emphasizing the number of services billed (volume of care). Proposed advanced APMs are evaluated by an ad hoc committee (the Physician-Focused Payment Models Technical Advisory Committee), which provides comments and recommendations to the Secretary as to whether new payment models meet the criteria of APMs. For 2019, there are 13 advanced APMs under the QPP, though not all are available to all physicians and practitioners, as some are restricted to certain special services (e.g., oncology care, joint replacement) or geographic locations (e.g., Vermont's Medicare ACO Initiative, Maryland's Total Cost of Care Model).

MACRA established incentives to make APMs more attractive than MIPS. First, qualifying participants in advanced APMs are eligible for an annual prepaid bonus (paid 2019-2024).52 Second, beginning in 2026, there will be two update factors, one for items and services furnished by a participant in an advanced APM and another for those electing to remain in the modified FFS payment system (MIPS) that do not participate in an advanced APM. The update factor for the advanced APM participants will be 0.75%, and the update factor for MIPS will be 0.25%,53 causing a difference between the payment levels that will grow over time.

Therapy Services

Medicare covers medically necessary outpatient physical and occupational therapy and speech-language pathology services. Beginning in 1997 and for many years subsequently but intermittently,54 beneficiaries faced limits (therapy caps) on how much Medicare would pay for outpatient therapy services in a calendar year.

BBA 18 permanently repealed the outpatient therapy caps beginning January 1, 2018, and established a requirement that therapy services exceeding $3,000 would trigger a manual medical review (MMR) of the medical necessity of these services, in years 2018-2028. Beginning with 2029, the annual MMR threshold limit is to be increased by the percentage increase in the MEI, and it is to be applied separately for (1) physical therapy services and speech-language pathology services combined and (2) occupational therapy services.

Preventive Services55

Medicare statute prohibits payments for covered items and services that are "not reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member,"56 which would effectively exclude the coverage of preventive and screening services. However, Congress has explicitly added and expanded Medicare coverage for a number of such services through legislation, including through MMA, MIPPA, and ACA. Under current law, if a preventive service is recommended for use by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF, an independent evidence-review panel) and Medicare covers the service,57 all cost sharing must be waived. Also, the Secretary may add coverage of a USPSTF-recommended service that is not already covered. Coverage for preventive and screening services currently includes, among other services, (1) a "welcome to Medicare" physical exam during the first year of enrollment in Part B and an annual visit and prevention plan thereafter; (2) flu vaccine (annual), pneumococcal vaccine, and hepatitis B vaccine (for persons at high risk); (3) screening tests for breast, cervical, prostate, and colorectal cancers; (4) screening for other conditions such as depression, alcohol misuse, heart disease, glaucoma, and osteoporosis; and (5) intensive behavioral therapy for heart disease and for obesity.58 Payments for these services are provided under the physician fee schedule and/or the clinical laboratory fee schedule.

Clinical Laboratory and Other Diagnostic Tests

Part B covers outpatient clinical laboratory tests, such as certain blood tests, urinalysis, and some screening tests, provided by Medicare-participating laboratories. These services may be furnished by labs located in hospitals and physician offices, as well as by independent labs. Beneficiaries have no co-payments or deductibles for covered clinical lab services.

From 1984 until recently, payments for outpatient clinical laboratory services were made on the basis of the Medicare clinical laboratory fee schedule (CLFS), which set payment amounts as the lesser of the amount billed, the local fee for a geographic area, or a national limit amount. Most clinical lab services were paid at the national limit amount. The national limits were set at a percentage (74%) of the median of all local fee schedule amounts for each laboratory test code; therefore, fee schedule amounts may differ by region. In general, annual increases in clinical lab fees have been based on the percentage change in the CPI-U. However, since 1987, Congress has specified lower updates. Beginning in 2014, with certain exceptions, laboratory tests provided in hospital outpatient departments are no longer paid separately under the CLFS and are instead included in the OPPS payments.

PAMA introduced a new method for determining clinical laboratory payments and required CMS to base Medicare CLFS reimbursement on reported private insurance payment amounts. Medicare has been using weighted median private insurer rates to calculate Medicare payment rates for laboratory tests paid under the CLFS since January 1, 2018.59 These payment rates are national and do not vary by geographic area.

Part B also covers diagnostic nonlaboratory x-ray tests and other diagnostic tests, as well as x-ray, radium, and radioisotope therapy. Generally, these services are paid for under the physician fee schedule, with beneficiaries responsible for a 20% coinsurance payment.

Durable Medical Equipment, Prosthetics, Orthotics, and Supplies

Medicare covers a wide variety of equipment and devices under the heading of durable medical equipment (DME), prosthetics, and orthotics (PO) if they are medically necessary and are prescribed by a physician. DME is defined as equipment that (1) can withstand repeated use, (2) has an expected life of at least three years (effective for items classified as DME after January 1, 2012), (3) is used primarily to serve a medical purpose, (4) is not generally useful in the absence of an illness or injury, and (5) is appropriate for use in the home. DME includes such items as hospital beds, wheelchairs, blood glucose monitors, and oxygen and oxygen equipment. It also includes related supplies (S), such as drugs and biologics that are necessary for the effective use of the product. Prosthetics (P) are items that replace all or part of a body organ or its function, such as colostomy bags, pacemakers, and artificial eyes, arms, or legs. Orthotics (O) are braces that support a weak or deformed body member, such as leg or back braces.

Except in competitive bidding areas (CBAs, described below), Medicare pays for most durable medical equipment, prosthetics, orthotics, and supplies (DMEPOS) based on fee schedules. Medicare pays 80% of the lower of the supplier's charge for the item or the fee schedule amount. The beneficiary is responsible for the remaining 20%. In general, fee schedule amounts are updated each year by a (1) measure of price inflation, and (2) a measure of economy-wide productivity, which may result in lower fee schedule amounts from one year to the next. Since 2016, the fee schedule rates that applied outside of competitive bidding areas for certain DMEPOS have been reduced based on price information from the competitive bidding program. The reductions were phased in during 2016, and fully phased in starting in January 2017. In response to concerns that the adjusted rates were too low, the Secretary again applied the phase-in rate for rural and noncontiguous areas not subject to competitive bidding starting in June 2018. Currently, two different fee schedules apply outside of CBAs. First, in rural or noncontiguous areas, the fee schedule is a 50/50 blend of the fee schedule with and without the reductions based on information from competitive bidding (i.e., the phase-in methodology). Second, in nonrural and contiguous areas, the fee schedule amounts are fully adjusted by information from the competitive bidding program.

Numerous studies and investigations indicated that Medicare paid more for certain items of DME and PO than some other health insurers and some retail outlets.60 Such overpayments were attributed, in part, to the fee schedule mechanism of payment. MMA required the Secretary to establish a Competitive Acquisition Program for certain DMEPOS in specified areas. Instead of paying for medical equipment based on a fee schedule established by law, payment for items in competitive bidding areas was based on the supplier bids. The program started in 9 metropolitan areas in January 2011 and had expanded to 130 competitive bidding areas in 2018. However, the program has been suspended while a new bidding methodology is established. During the gap, the payments for previously competitively bid items in competitive bidding areas will be the amounts that applied on December 31, 2018, increased, yearly, by a measure of inflation.61

Part B Drugs and Biologics

Certain specified outpatient prescription drugs and biologics are covered under Medicare Part B.62 (However, most outpatient prescription drugs are covered under Part D, discussed below.) Covered Part B drugs and biologics include drugs furnished incident to physician services, immunosuppressive drugs following a Medicare-covered organ transplant, erythropoietin for treatment of anemia for individuals with ESRD when not part of the ESRD composite rate, oral anticancer drugs (provided they have the same active ingredients and are used for the same indications as chemotherapy drugs that would be covered if furnished incident to physician services), certain vaccines under selected conditions, and drugs administered through DME. Generally, Medicare reimburses physicians and other providers, such as hospital outpatient clinics, for covered Part B drugs and biologics at 106% of the volume weighted average sales price of all drugs billed under the same billing code, although some Part B drugs, such as those administered through DME, are reimbursed at 95% of the drug's average wholesale price. Health care providers also are paid separately for administering Medicare Part B drugs. Medicare pays 80% of the amount paid to providers, and beneficiaries are responsible for the remaining 20%.

Hospital Outpatient Department Services

A hospital outpatient is a person who has not been admitted by the hospital as an inpatient but is registered on the hospital records as an outpatient.63 Generally, payments under the hospital outpatient prospective payment system (OPPS) cover the operating and capital-related costs that are directly related and integral to performing a procedure or furnishing a service on an outpatient basis. These payments cover services such as the use of an operating suite, treatment, procedure, or recovery room; use of an observation bed as well as anesthesia; certain drugs or pharmaceuticals; incidental services; and other necessary or implantable supplies or services. Payments for services such as those provided by physicians and other professionals as well as therapy and clinical diagnostic laboratory services, among others, are separate.

Under the OPPS, the unit of payment for acute care hospitals is the individual service or procedure as assigned to an ambulatory payment classification (APC). To the extent possible, integral services and items (excluding physician services paid under the physician fee schedule) are bundled within each APC. Specified new technologies are assigned to "new technology APCs" until clinical and cost data are available to permit assignment into a "clinical APC." Medicare's hospital outpatient payment is calculated by multiplying the relative weight associated with an APC by a conversion factor. For most APCs, 60% of the conversion factor is geographically adjusted by the wage index used for the inpatient prospective payment system. Except for new technology APCs, each APC has a relative weight that is based on the median cost of services in that APC. The OPPS also includes pass-through payments for new technologies (specific drugs, biologicals, and devices) and payments for outliers.

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has recommended site-neutral payment policies that base payments on the resources needed to provide high-quality care in the most efficient setting.64 The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 15; P.L. 114-74) gave CMS the authority to add new restrictions on Medicare payments for services furnished in provider-based off-campus hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) to address discrepancies between payments under the MPFS and the OPPS for similar services. In its 2019 OPPS Final Rule, CMS explicitly applies the site-neutral policy to clinic visits, the most commonly billed service in hospital outpatient departments.65

Ambulatory Surgical Center Services

An ambulatory surgical center (ASC) is a distinct entity that furnishes outpatient surgical procedures to patients who do not require an overnight stay after the procedure. According to MedPAC, most ASCs are freestanding facilities rather than part of a larger facility, such as a hospital. Medicare covers surgical and medical services performed in an ambulatory surgical center that are (1) commonly performed on an inpatient basis but may be safely performed in an ASC; (2) not of a type that are commonly performed or that may be safely performed in physicians' offices; (3) limited to procedures requiring a dedicated operating room or suite and generally requiring a postoperative recovery room or short-term (not overnight) convalescent room; and (4) not otherwise excluded from Medicare coverage.

Medicare pays for surgery-related facility services provided in ASCs using a prospective payment system based on the OPPS. (Associated physician fees are paid for separately under the physician fee schedule.) Each of the approximately 3,500 procedures approved for payment in an ASC is classified into an APC group on the basis of clinical and cost similarity. The ASC system primarily uses the same payment groups as the OPPS; however, ASC payment rates are generally lower. The ASC weights are scaled (reduced) to account for the different mix of services in an ASC, and the ASC conversion factor (the base payment amount) is lower. A different payment method is used to set ASC payment for office-based procedures, separately payable radiology services, separately payable drugs, and device-intensive procedures.66 In addition, separate payments are made for certain ancillary items and services when they are integral to surgical procedures, including corneal tissue acquisition, brachytherapy sources, certain radiology services, many drugs, and certain implantable devices. The application of the site-neutral payment policy to clinic visits also affects such payments to ASCs (see discussion above).

Ambulance

Medicare Part B covers emergency and nonemergency ambulance services to or from a hospital, a critical access hospital, a skilled nursing facility, or a dialysis facility for End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) beneficiaries who require dialysis when other modes of transportation could endanger the Medicare beneficiary's health.67 In most cases, the program covers 80% of the allowed amount for the service, and the beneficiary is responsible for the remaining 20%.

Generally, ambulance services are covered if (1) transportation of the beneficiary occurs; (2) the beneficiary is taken to an appropriate location (generally, the closest appropriate facility); (3) the ambulance service is medically necessary (other forms of transportation are contraindicated); (4) the ambulance provider or supplier meets state licensing requirements; and (5) the transportation is not part of a Medicare Part A covered stay.68

Medicare covers both scheduled and nonscheduled nonemergency transports if the beneficiary is bed-confined or meets other medical necessity criteria. Medicare may also cover emergency ambulance transportation by airplane or helicopter if the beneficiary's location is not easily reached by ground transportation or if long distance or obstacles, such as heavy traffic, would prevent the individual from obtaining needed care.69

Medicare pays for ambulance services according to a national fee schedule. The fee schedule establishes seven categories of ground ambulance services and two categories of air ambulance services. Medicare pays for different levels of ambulance services, which reflect the staff training and equipment required to meet the patient's medical condition or health needs.70 Generally, basic life support is provided by emergency medical technicians (EMTs). Advanced life support is provided by EMTs with advanced training or by paramedics.

Some rural ground and air ambulance services may qualify for increased payments. Also, ambulance providers that are CAHs, or that are entities that are owned and operated by a CAH, are paid on a reasonable-cost basis rather than the fee schedule if they are the only ambulance provider within a 35-mile radius.71

Rural Health Clinics and Federally Qualified Health Centers

Medicare covers Part B services in rural health clinics (RHCs) and federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) provided by (1) physicians and specified nonphysician practitioners; (2) visiting nurses for homebound patients in home health shortage areas; (3) registered dieticians or nutritional professionals for diabetes training and medical nutrition therapy; and (4) others, as well as certain drugs administered by a physician or nonphysician practitioner.

RHCs are paid based on an "all-inclusive" cost-based rate per beneficiary visit subject to a per visit upper limit, adjusted annually for inflation. For cost-reporting periods that began on or after October 1, 2014, FQHCs are paid a base payment rate per visit (with a limit, in most cases, of one billable visit per day) under a PPS methodology. Each FQHC's PPS rate is adjusted based on the location where the service is furnished using geographic adjustment factors, which are the geographic practice cost indices (GPCI) used in Medicare's physician fee schedule (MPFS). This rate is increased by 34% for new patients (those not seen in the FQHC organization within the past three years). The 34% increase also applies when a beneficiary receives a comprehensive initial Medicare visit (an initial preventive physician examination or an initial annual wellness visit) or a subsequent annual wellness visit. Effective January 1, 2017, the FQHC PPS base rate is updated annually using an FQHC-specific market basket. Medicare's payment to the FQHC is equal to 80% of the lesser of the adjusted PPS rate or the FQHC's actual charges associated with the visit, and the beneficiary is responsible for a 20% coinsurance.

Part C, Medicare Advantage

Medicare Advantage (MA) is an alternative way for Medicare beneficiaries to receive covered benefits. Under MA, private health plans are paid a per-person amount to provide all Medicare covered benefits (except hospice) to beneficiaries who enroll in their plan. Medicare beneficiaries who are eligible for Part A, enrolled in Part B, and do not have ESRD are eligible to enroll in an MA plan if one is available in their area.72 Some MA plans may choose their service area (local MA plans), while others agree to serve one or more regions defined by the Secretary (regional MA plans). In 2019, nearly all Medicare beneficiaries have access to an MA plan and approximately a third of beneficiaries are enrolled in one.73 Private plans may use different techniques to influence the medical care used by enrollees. Some plans, such as health maintenance organizations (HMOs), may require enrollees to receive care from a restricted network of medical providers; enrollees may be required to see a primary care physician who will coordinate their care and refer them to specialists as necessary. Other types of private plans, such as private fee-for-service (PFFS) plans, may look more like original Medicare, with fewer restrictions on the providers an enrollee can see and minimal coordination of care.

In general, MA plans offer additional benefits or require smaller co-payments or deductibles than original Medicare. Sometimes beneficiaries pay for these additional benefits through a higher monthly premium, but sometimes they are financed through plan savings. The extent of extra benefits and reduced cost sharing varies by plan type and geography. However, MA plans are seen by some beneficiaries as an attractive alternative to more expensive supplemental insurance policies found in the private market.

By contract with CMS, a plan agrees to provide all required services covered in return for a capitated monthly payment adjusted for the demographics and health history of their enrollees. The same monthly payment is made regardless of how many or few services a beneficiary actually uses. In general, the plan is at-risk if costs, in the aggregate, exceed program payments; conversely, the plan can retain savings if aggregate costs are less than payments. Payments to MA plans are based on a comparison of each plan's estimated cost of providing Medicare covered services (a bid) relative to the maximum amount the federal government will pay for providing those services in the plan's service area (a benchmark). If a plan's bid is less than the benchmark, its payment equals its bid plus a rebate. The size of the rebate is dependent on plan quality and ranges from 50% to 70% of the difference between the bid and the benchmark. The rebate must be returned to enrollees in the form of additional benefits, reduced cost sharing, reduced Part B or Part D premiums, or some combination of these options. If a plan's bid is equal to or above the benchmark, its payment will be the benchmark amount and each enrollee in that plan will pay an additional premium, equal to the amount by which the bid exceeds the benchmark.

The MA benchmarks are determined through statutorily specified formulas that have changed over time. Since BBA 97, formulas have increased the benchmark amounts, in part, to encourage plan participation in all areas of the country. As a result, however, the benchmark amounts (and plan payments) in some areas have been higher than the average cost of original FFS Medicare. The ACA changed the way benchmarks are calculated by tying them closer to (or below) spending in FFS Medicare, and adjusting them based on plan quality. In a recent analysis, MedPAC found that "over the past few years, plan bids and payments have come down in relation to FFS spending while MA enrollment continues to grow. The pressure of lower benchmarks has led to improved efficiencies and more competitive bids that enable MA plans to continue to increase enrollment by offering benefits that beneficiaries find attractive."74

In 2006, the MA program began to offer MA regional plans. Regional MA plans must agree to serve one or more regions designated by the Secretary. There are 26 MA regions consisting of states or groups of states. Regional plan benchmarks include two components: (1) a statutorily determined amount (comparable to benchmarks described above) and (2) a weighted average of plan bids. Thus, a portion of the benchmark is competitively determined. Similar to local plans, plans with bids below the benchmark are given a rebate, while plans with bids above the benchmark require an additional enrollee premium.

In general, MA eligible individuals may enroll in any MA plan that serves their area. However, some MA plans may restrict their enrollment to beneficiaries who meet additional criteria. For example, employer-sponsored MA plans are generally only available to the retirees of the company sponsoring the plan. In addition, Medicare Special Needs Plans (SNPs) are a type of coordinated care MA plan that exclusively enrolls, or enrolls a disproportionate percentage of, special needs individuals. Special needs individuals are any MA eligible individuals who are either institutionalized as defined by the Secretary, eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid, or have a severe or disabling chronic condition and would benefit from enrollment in a specialized MA plan.

Part D

Medicare Part D provides coverage of outpatient prescription drugs to Medicare beneficiaries who choose to enroll in this optional benefit.75 (As previously discussed, Part B provides limited coverage of some outpatient prescription drugs.) In 2019, about 47 million (about 77%) of eligible Medicare beneficiaries are estimated to be enrolled in a Part D plan.76 Prescription drug coverage is provided through private prescription drug plans (PDPs), which offer only prescription drug coverage, or through Medicare Advantage prescription drug plans (MA-PDs), which offer prescription drug coverage that is integrated with the health care coverage they provide to Medicare beneficiaries under Part C. Plans must meet certain minimum requirements; however, there are significant variations among them in benefit design, including differences in premiums, drugs included on plan formularies, and cost sharing for particular drugs.

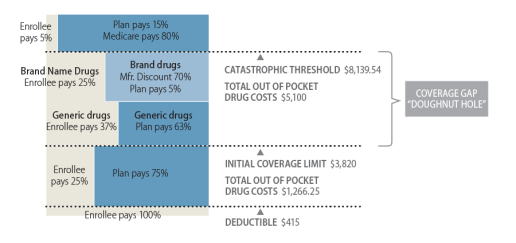

Part D prescription drug plans are required to offer either "standard coverage" or alternative coverage that has actuarially equivalent benefits. In 2019, "standard coverage" has a $415 deductible and a 25% coinsurance for costs between $415 and $3,820. From this point, there is reduced coverage until the beneficiary has out-of-pocket costs of $5,100 (an estimated $8,139.54 in total spending); this coverage gap has been labeled the "doughnut hole."77 Once the beneficiary reaches the catastrophic limit, the program pays all costs except for the greater of 5% coinsurance or $3.40 for a generic drug and $8.50 for a brand-name drug. As required by the ACA, in 2010, Medicare sent a tax-free, one-time $250 rebate check to each Part D enrollee who reached the doughnut hole. Additionally, starting in 2011, the coverage gap is being gradually reduced each year. Under the ACA, the coverage gap for both brand-name and generic drugs was to be eliminated in 2020, but Congress moved up the date to 2019 for brand-name drugs as part of BBA 18.78 In 2019, a 70% discount is provided by drug manufacturers and Medicare pays an additional 5% of the cost of brand-name drugs dispensed during the coverage gap. In 2019, Medicare also pays 63% of the cost of generic drugs dispensed during the coverage gap and enrollees pay 37%. (See Figure 2.) By 2020, through a combination of manufacturer discounts and increased Medicare coverage, Part D enrollees will be responsible for 25% of the costs for brand-name and generic drugs in the coverage gap (the same as during the initial coverage period). Most plans offer actuarially equivalent benefits rather than the standard package, including alternatives such as reducing or eliminating the deductible, or using tiered cost sharing with lower cost sharing for generic drugs.

Medicare's payments to plans are determined through a competitive bidding process, and enrollee premiums are tied to plan bids. Plans are paid a risk-adjusted monthly per capita amount based on their bids during a given plan year. Part D plan sponsors determine payments for drugs and are expected to negotiate prices. The federal government is prohibited from interfering in the price negotiations between drug manufacturers, pharmacies, and plans (the so-called "non-interference clause").

Part D also provides enhanced coverage for low-income enrolled individuals, such as persons who previously received drug benefits under Medicaid (known as "dual eligibles"—enrollees in both Medicare and Medicaid). Additionally, certain persons who do not qualify for Medicaid, but whose incomes are below 150% of poverty, may also receive assistance for some portion of their premium and cost-sharing charges.

|

|

Sources: Figure by CRS based on data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), "Announcement of CY2019 Medicare Advantage Capitation Rates and Medicare Advantage and Part D Payment Policies and Final Call Letter and Request for Information," Attachment VI, April 2, 2018. Notes: Enrollees need to spend $5,100 in 2019 in out-of-pocket costs to reach the catastrophic threshold. Based on average spending patterns, the estimated amount of total spending needed to reach the catastrophic threshold is $8,139.54; however, total spending at the catastrophic threshold (beneficiary payments and amounts covered by the plans and manufacturer discounts) may vary depending on the portion of brand-name drugs and generic drugs used in the coverage gap since a greater portion of the cost of brand-name drugs counts toward the out-of-pocket spending total. Amounts paid by the enrollee and the 70% manufacturer discount count as out-of-pocket costs, whereas the 5% coverage by Medicare of the cost of brand-name drugs and the 63% coverage of the cost of generic drugs do not. |

The MMA included significant incentives for employers to continue to offer coverage to their retirees by providing a 28% federal subsidy. In 2019, the maximum potential subsidy per covered retiree is $2,264 for employers or unions offering drug coverage that is at least actuarially equivalent (called "creditable" coverage) to standard coverage.79 Employers or unions may select an alternative option (instead of taking the subsidy) with respect to Part D, such as electing to pay a portion of the Part D premiums. They may also elect to provide enhanced coverage, though this has some financial consequences for the employer or union. Alternatively, employers or unions may contract with a PDP or MA-PD to offer the coverage or become a Part D plan sponsor themselves for their retirees.

Administration

A variety of public and private entities are involved in carrying out Medicare administrative and oversight functions. CMS, an agency within HHS, has primary operational responsibilities. Such responsibilities include managing program finances, developing policies and regulations, setting payment rates, and developing the program's information-technology infrastructure. CMS conducts its activities through its headquarters and 10 regional offices.80 The Social Security Administration, however, enrolls beneficiaries into the program and issues Medicare beneficiary cards.81

CMS also contracts with various private entities, including private health insurance companies, to help administer the program.82 For example, Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) process and pay Parts A and B reimbursement claims, enroll providers and suppliers, educate providers and suppliers on billing requirements, support appeal processes, and answer provider and supplier inquiries through call centers, as well as other activities.83 Qualified Independent Contractors (QICs) perform second-level reviews on appeals initially reviewed by MACs.84

Medicare's quality assurance activities are primarily handled by State Survey Agencies and Quality Improvement Organizations (QIOs), which operate in all states and the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The State Survey Agencies are responsible for inspecting Medicare provider facilities (e.g., nursing homes, home health agencies, and hospitals) to ensure that they are in compliance with federal safety and quality standards referred to as Conditions (or Requirements) of Participation.85 Alternatively, some types of providers, including hospitals, may receive certification through private accrediting agencies, such as the Joint Commission.86 QIOs are mostly private, not-for-profit organizations that monitor the quality of care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries and educate providers on the latest quality-improvement techniques.87

Medicare program integrity activities, such as audits, provider education, medical review, and predictive data analysis, also are carried out by a variety of government and private entities. For example, the Center for Program Integrity within CMS works together with the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and the HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) to identify and prevent fraud, waste, and abuse in Medicare.88 CMS also works with private contractors to carry out certain program-integrity functions. Unified Program Integrity Contractors (UPICs) perform integrity-related activities including data analysis to identify potentially fraudulent claims (bills) for Medicare Parts A and B, home health and hospice services, and DME.89 Similarly, the National Benefit Integrity Medicare Drug Integrity Contractor (MEDIC) is responsible for identifying and investigating fraud, waste, and abuse in Medicare Advantage and Part D.90 When appropriate, the UPICs and MEDIC work with and refer cases to law enforcement, including OIG and DOJ.

In addition, Recovery Audit Contractors (RACs) are responsible for identifying improper Medicare payments, including both underpayments and overpayments, and for recouping any overpayments made to providers.91 Each year, the Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT) program quantifies a national improper Medicare payment rate by examining a random sample of claims.92 In turn, the Supplemental Medical Review Contractor targets medical reviews in areas where OIG, RACs, and CERT have identified vulnerabilities and/or questionable billing patterns to identify ways to lower improper payment rates.93

As required by the ACA, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) was established in January 2011 to test and evaluate innovative payment and service delivery models to reduce program expenditures under Medicare.94 Examples of these models include providing payment incentives for groups of doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers (Accountable Care Organizations, or ACOs) to coordinate the services they provide to Medicare beneficiaries; bundling payments for services provided in different settings during a beneficiary's episode of care; and reimbursing health providers based on the quality of care rather than on the volume of services.95 CMMI also plays an important role in developing and implementing the new physician payment models required by MACRA.96

Medicare beneficiary education and outreach duties are shared between CMS and the Social Security Administration. Each year, CMS mails out a "Medicare and You" handbook to beneficiaries, which provides information on their benefits for the upcoming year.97 Additional educational materials and responses to frequently asked questions may be found on the CMS-maintained "Medicare.gov" website,98 and beneficiaries may call a CMS-operated 1-800 number for assistance with specific questions and help with selecting and enrolling in a Medicare Advantage and/or Part D plan.99 A Medicare beneficiary ombudsman is also available to provide assistance to Medicare consumers with their complaints, grievances, and requests.100

The Social Security Administration is responsible for notifying low-income Medicare beneficiaries about programs that may be able to assist them with their medical and prescription drug expenses. The Social Security Administration also provides general Medicare eligibility and enrollment information on its webpage and on Social Security benefit statements.101 Finally, CMS partners with community-based organizations, such as State Health Insurance Assistance Programs, in every state to provide educational resources and personalized assistance to Medicare beneficiaries.102

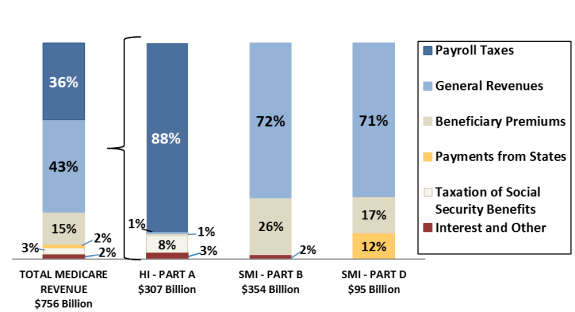

Financing

Medicare's financial operations are accounted for through two trust funds maintained by the Department of the Treasury—the Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund for Part A and the Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) trust fund for Parts B and D. For beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage (Part C), payments are made on their behalf in appropriate portions from the HI and SMI trust funds. HI is primarily funded by payroll taxes, while SMI is primarily funded through general revenue transfers and premiums. (See Figure 3.) The HI and SMI trust funds are overseen by a Board of Trustees that provides annual reports to Congress.103

|

|

Source: 2019 Report of the Medicare Trustees, Table II.B1. Notes: Totals may not add to 100% due to rounding. HI is the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, and SMI is the Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund. |

The trust funds are accounting mechanisms. Income to the trust funds is credited to the fund in the form of interest-bearing government securities. Expenditures for services and administrative costs are recorded against the fund. These securities represent obligations that the government has issued to itself. As long as a trust fund has a balance, the Department of the Treasury is authorized to make payments for it from the U.S. Treasury.

Medicare expenditures are primarily paid for through mandatory spending—generally Medicare pays for all covered health care services provided to beneficiaries. Aside from certain constraints in HI described below, the program is not subject to spending limits. Additionally, most Medicare expenditures (aside from premiums paid by beneficiaries) are paid for by current workers through income taxes and dedicated Medicare payroll taxes, that is, current income is used to pay current expenditures. Medicare taxes paid by current workers are not set aside to cover their future Medicare expenses.

Part A Financing

The primary source of funding for Part A is payroll taxes paid by employees and employers. Each pays a tax of 1.45% on the employee's earnings; the self-employed pay 2.9%. Beginning in 2013, some higher-income employees pay higher payroll taxes.104 Unlike Social Security, there is no upper limit on earnings subject to the tax. Other sources of income include (1) interest on federal securities held by the trust fund, (2) a portion of federal income taxes that individuals pay on their Social Security benefits, and (3) premiums paid by voluntary enrollees who are not automatically entitled to Medicare Part A. Income for Part A is credited to the HI trust fund. Part A expenditures for CY2019 are estimated to reach approximately $330 billion.105 Revenue to the trust fund is expected to consist of about $285 billion in payroll tax income and another $38 billion in interest and other income. The Medicare Trustees project that in CY2019, the HI trust fund will incur a deficit of approximately $7 billion.