Introduction

Water infrastructure issues, particularly regarding funding, continue to receive attention from some Members of Congress and a wide array of stakeholders. Localities are primarily responsible for providing wastewater and drinking water infrastructure services. According to the most recent estimates by states and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), expected capital costs for such facilities total $744 billion over a 20-year period.1 While some analysts and stakeholders debate whether these estimates understate or overstate capital needs, most agree that the affected communities face formidable challenges in providing adequate and reliable water infrastructure services.

Capital investments in water infrastructure are necessary to maintain high quality service that protects public health and the environment, and capital facilities are a major investment for local governments. The vast majority of public capital projects are debt-financed (i.e., they are not financed on a pay-as-you-go basis from ongoing revenues to the water utility). The principal financing tool that local governments use is the issuance of tax-exempt municipal bonds. At least 70% of U.S. water utilities rely on municipal bonds and other debt to some degree to finance capital investments.2 Beyond municipal bonds, federal assistance through grants and loans is available for some projects but is insufficient to meet all needs. Finally, public-private partnerships (P3s), which are long-term contractual arrangements between a public utility and a private company, currently provide only limited capital financing in the water sector. Although they are increasingly used in transportation and some other infrastructure sectors, especially P3s that involve private sector debt or equity investment in a project, most P3s for water infrastructure involve contract operations for operation and maintenance. Numerous drinking water utilities are privately owned and make significant private capital investments in water infrastructure,3 unlike the wastewater sector, in which facilities are generally owned by municipalities.

In recent years, Congress has considered several legislative options to help finance water infrastructure projects, including projects to build and upgrade wastewater and drinking water treatment facilities. Some Members have offered proposals that would amend, supplement, and/or complement the existing clean water and drinking water State Revolving Fund (SRF) programs.4 Other proposals would address water infrastructure issues outside the framework of the SRF programs.

In 2014, Congress established the Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) program, which creates a new mechanism of providing financial assistance for water infrastructure projects. The first section of this report provides an overview of the WIFIA program, including its origins, scope, and applicability. The second section describes WIFIA program appropriation levels and estimates of the amount of credit assistance the federal funding would provide. The third section discusses EPA's implementation of the WIFIA program, including recent developments. The fourth section identifies selected issues that may be of interest to policymakers.

Program Overview

The WIFIA approach for supporting investment in water infrastructure is modeled after the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program, which was established in 1998 (see textbox below for further details). As the name suggests, only transportation projects are eligible for TIFIA assistance. The TIFIA program generated interest in creating a similar program for water infrastructure.

As discussed below, the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (WRRDA 2014) established and authorized appropriations for the WIFIA program. Congress provided the first appropriations for EPA to offer credit assistance, such as direct loans, under the WIFIA program in FY2017. In 2018, America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 (AWIA) reauthorized appropriations for the program and amended certain WIFIA provisions.5

|

Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) TIFIA was enacted as part of the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21; P.L. 105-178) and was reauthorized in 2012 in the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21; P.L. 112-141). TIFIA provides federal credit assistance up to a maximum of 49% of project costs in the form of secured loans, loan guarantees, and lines of credit (23 U.S.C. 601 et seq.). Transportation projects costing at least $50 million (or at least $25 million in rural areas) are eligible for TIFIA financing. The threshold for Intelligent Transportation Systems projects is $15 million. Projects must also have a dedicated revenue stream to be eligible for credit assistance. TIFIA can provide senior or subordinated debt. With the enactment of MAP-21, funding authorized for the TIFIA program increased from $122 million annually to $750 million in FY2013 and $1 billion in FY2014 and FY2015. However, the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act (FAST Act, P.L. 114-94), enacted in December 2015, reduced the amount available to support TIFIA loans and other credit assistance. Under the FAST Act, the annual amount is $275 million in each of FY2016 and FY2017, $285 million in FY2018, and $300 million in each of FY2019 and FY2020. |

WRRDA 2014

WRRDA 2014 established a five-year WIFIA pilot program.6 The act authorized (1) EPA to provide credit assistance (loans or loan guarantees)7 for a range of drinking water and wastewater projects and (2) the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to provide similar assistance for water resource projects, such as flood control or hurricane and storm damage reduction.

Congress provided appropriations to EPA to administer the WIFIA program in FY2014. Congress has not appropriated analogous funds to the Corps (nor has the Administration requested funds for a Corps WIFIA program) that would enable the Corps to implement a WIFIA program as laid out in WRRDA 2014. Regardless, this section identifies WIFIA provisions relating to both EPA and the Corps.

To implement the program, the act authorized appropriations of $175 million over five years to both EPA and the Corps (beginning with $20 million for each agency in FY2015 and increasing to $50 million in FY2019). Project costs must generally be $20 million or larger to be eligible for credit assistance. For projects in less populous communities (defined by WIFIA as populations of 25,000 or less), project costs must be $5 million or more. WIFIA credit assistance is available to

- state infrastructure financing authorities;8

- a corporation;

- a partnership;

- a joint venture;

- a trust; or

- a federal, state, local, or tribal government (or consortium of tribal governments).

In the case of projects carried out by private entities, such projects must be publicly sponsored. To meet this requirement, WIFIA allows a project applicant to demonstrate to the EPA or the Corps that the affected state, local, or tribal government supports the project. The maximum amount of a loan is 49% of eligible project costs, but the act authorizes EPA or the Corps to make available up to 25% of available funds each year for credit assistance in excess of 49% of project costs. Except for certain projects in rural areas, the total amount of federal assistance (i.e., WIFIA and other sources combined) may not exceed 80% of a project's cost.

Activities eligible for assistance under the WIFIA pilot program include project development and planning, construction, acquisition of real property, and carrying costs during construction. Categories eligible for assistance by EPA include

- projects eligible for assistance through the clean water state revolving fund (CWSRF) and drinking water state revolving fund (DWSRF) programs (i.e., wastewater treatment and community drinking water facilities);

- enhanced energy efficiency of a public water system or wastewater treatment works;

- repair or rehabilitation of aging wastewater and drinking water systems;

- desalination, water recycling, aquifer recharge, or development of alternative water supplies to reduce aquifer depletion;

- prevention, reduction, or mitigation of the effects of drought;9 or

- a combination of eligible projects.

Categories eligible for assistance by the Corps include

- flood control or hurricane and storm damage reduction projects,

- environmental restoration,

- coastal or inland harbor navigation improvement, or

- inland and intracoastal waterways navigation improvement.

The EPA Administrator or Secretary of the Army, as appropriate, determines project eligibility based on creditworthiness and dedicated revenue sources for repayment. Selection criteria include

- the national or regional significance of the project,

- extent of public or private financing in addition to WIFIA assistance,

- use of new or innovative approaches,

- the amount of budget authority required to fund the WIFIA assistance,

- the extent to which a project serves regions with significant energy development or production areas, and

- the extent to which a project serves regions with significant water resources challenges.

Responding to concerns from some groups that WIFIA could impair and diminish support for clean water and drinking water SRF programs under the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act (see discussion below), the act requires the EPA Administrator, when the agency receives applications for WIFIA assistance, to notify state infrastructure financing authorities and give them the opportunity to commit funds to the project.

WIFIA-assisted projects must use American-made iron and steel products. Projects must also comply with the prevailing wage requirements of the Davis-Bacon Act in the same manner that they would under the SRF provisions of the Clean Water Act.10

In addition, the act directed EPA and the Corps to provide information on a website concerning applications and projects that have received assistance, and the Government Accountability Office must report to Congress (four years after enactment, i.e., June 10, 2018) on the program and provide recommendations for continuing, changing, or terminating the WIFIA program.11 As discussed below, AWIA extended the deadline for this report.

AWIA 2018

AWIA, enacted on October 23, 2018, amended WIFIA in several ways:12

- It removed WIFIA's designation as a pilot program.

- It authorized appropriations of $50.0 million for each of FY2020 and FY2021 for EPA program implementation.

- It authorized EPA to administer the WIFIA program for relevant agencies (through an interagency agreement), specifically directing EPA to enter into such an agreement with the commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation within the Department of the Interior.

- It required the Government Accountability Office to prepare a report for Congress by October 23, 2021.

In addition, AWIA authorized an additional $5 million in WIFIA appropriations to provide credit assistance to state finance authorities to support combined projects eligible for assistance from the CWSRF and DWSRF. This additional appropriation authority is available for FY2020 and FY2021 and is available only if (1) Congress appropriates funding for both the CWSRF and the DWSRF at FY2018 levels or 105% or more of the previous year's funding, whichever is greater, and (2) EPA receives at least $50.0 million in WIFIA appropriations. State financing authorities may use funding from WIFIA appropriations to cover 100% of project costs, in contrast to the 80% federal financial assistance cap that applies to most WIFIA-financed projects.13

Appropriations

For each of FY2015 and FY2016, Congress provided $2.2 million for EPA to hire staff and design the new water infrastructure assistance program. In FY2017, Congress provided the first appropriations to cover the subsidy cost of the program, thus allowing implementation of WIFIA (i.e., making project loans). Congress provided a total of $30 million for the WIFIA program for FY2017 through two appropriations acts:

- The Further Continuing and Security Assistance Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 114-254), enacted on December 10, 2016, provided the first appropriation of funds to cover the subsidy cost of the program. P.L. 114-254 appropriated $20 million to EPA to begin making loans and allowed the agency to use up to $3 million of the total for administrative purposes. The act authorized EPA to use these appropriations to subsidize costs to provide credit assistance not to exceed $2.1 billion.14

- The Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), enacted on May 5, 2017, provided an additional $8 million for EPA to apply toward loan subsidy costs and $2 million for EPA's administrative expenses.15 The act authorized EPA to use funds to guarantee as much as $976 million in direct loans.16

For FY2018, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), provided $63 million for the WIFIA program (including $8 million for administrative costs).17 The act authorized EPA to use funds to guarantee as much as $6.71 billion in direct loans.18 EPA estimated that its budget authority ($55 million) would provide approximately $5.5 billion in credit assistance.19

For FY2019, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6) provided $68 million for the WIFIA program, including $8 million for administrative costs.20 The act authorized EPA to use funds to guarantee as much as $7.31 billion in direct loans.21 EPA estimated that its budget authority ($60 million) would provide approximately $6 billion in credit assistance.22

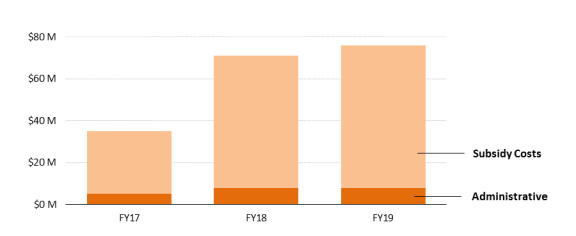

Figure 1 illustrates the WIFIA appropriations for administrative purposes and for loan subsidy costs between FY2017 and FY2019. The appropriations acts for FY2017 through FY2019 state that the appropriations for the subsidy costs would be available until expended. In contrast, fiscal year appropriations for WIFIA administrative costs are not available after specific dates.

|

Figure 1. WIFIA Appropriations in millions of dollars |

|

|

Source: Prepared by CRS. FY2017 appropriations from P.L. 114-254 and P.L. 115-31. FY2018 appropriations from P.L. 115-141. FY2019 appropriations from P.L. 116-6. |

As discussed above, WRRDA 2014 authorized a parallel program for water resources projects to be administered by the Corps. Congress has not yet appropriated funds (nor has the Administration requested funds for a Corps WIFIA program) that would enable the Corps to begin preparations or begin making WIFIA loans under the authority in the 2014 statute.

EPA Implementation

EPA began preparing for implementation of the WIFIA program, including through a series of public listening sessions in several U.S. cities, in 2014. The intended audience was municipal, state, and regional water utility officials; private sector financing professionals; and other interested organizations and parties. The purpose was to discuss project ideas, potential selection and evaluation criteria, and numerous other implementation issues.

In 2016, EPA issued two rules intended to explain and clarify some provisions of the program and establish guidelines for the application process. One was an interim final rule that sets guidelines for the application and selection of projects, defines the requirements for credit assistance, and defines reporting requirements and a fee collection structure.23 In this rule, EPA said that it would initially give funding priority to four types of projects:

- 1. adaptation to extreme weather and climate change;

- 2. enhanced energy efficiency of wastewater treatment works and public water systems;

- 3. green infrastructure;24 and

- 4. repair, rehabilitation, and replacement of infrastructure and conveyance systems.

Through the second rulemaking, EPA proposed a fee structure for WIFIA (application fee, credit processing fee, and servicing fee).25 EPA finalized this rule in June 2017.26 WIFIA authorizes EPA to charge fees to recover all or a portion of the agency's costs administering the program.27 EPA's final rule requires a nonrefundable fee for each project that is invited to submit a full WIFIA application. The application fee is $100,000, or $25,000 for projects serving small communities. The fees are not required in connection with submission of letters of interest but would be required for projects that EPA expects might reasonably proceed to closing on a credit assistance agreement. Enacted December 16, 2016, the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation (WIIN) Act (P.L. 114-322, Section 5008(c)) amended WIFIA to allow fees to be financed as part of the loan at the request of an applicant.28 In 2018, AWIA amended WIFIA to clarify that state financing authorities cannot pass along application fees on to the parties that utilize WIFIA assistance.

After EPA received its first appropriations to cover loan subsidy costs, it announced its first round of funding for the WIFIA program in January 2017.29 Additional rounds of funding have followed with each fiscal year's enacted appropriations.

Table 1 provides details for each of EPA's funding rounds, including the project priorities EPA listed in its annual funding notices, the number of letters of interest submitted, selected projects, and loans closed.

|

Fiscal Year |

Notice of Funding Availability |

Letters of Interest |

Selected Projects |

Loans Closed |

|

2017 |

Project priorities: Adaption to extreme weather events and climate change, enhanced energy efficiency of water utilities, green infrastructure, rehabilitation, and replacement of water infrastructure. Published: January 10, 2017 |

43 |

12 |

8 In aggregate, the closed loans account for $1.39 billion in federal financing |

|

2018 |

Project priorities: Provide clean and safe drinking water, including reducing exposure to lead; repair, rehabilitate, and replace aging water infrastructure and conveyance systems. Published: April 12, 2018 |

62 |

39 |

0 |

|

2019 |

Project priorities: Readiness to proceed; provide safe drinking water, including reducing exposure to lead and addressing emerging contaminants such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances; repair, rehabilitate, and replace aging water infrastructure and conveyance systems; water reuse and recycling. Published: April 5, 2019 |

Not yet available (NYA) |

NYA |

NYA |

Source: Compiled by CRS from EPA, "Notice of Funding Availability for Applications for Credit Assistance Under the WIFIA Program," 82 Federal Register 2933, January 10, 2017; EPA, "Notice of Funding Availability for Applications for Credit Assistance Under the WIFIA Program," 83 Federal Register 15828, April 12, 2018; EPA, "Notice of Funding Availability for Applications for Credit Assistance Under the WIFIA Program," 84 Federal Register 13657, April 5, 2019; https://www.epa.gov/wifia/wifia-selected-projects and https://www.epa.gov/wifia/wifia-letters-interest.

Notes: This information is current as of the date of this report.

Selected Issues

Subsidy Amount for Credit Assistance

From the federal perspective, an advantage of the WIFIA program is that it can provide a large amount of credit assistance relative to the amount of budget authority provided. In federal budgetary terms, WIFIA assistance has less of an impact than a grant, which is not repaid to the U.S. Treasury.

The volume of loans and other types of credit assistance that the program can provide is determined by the size of congressional appropriations and calculation of the subsidy amount. WIFIA defines the "subsidy amount" as follows:

The amount of budget authority sufficient to cover the estimated long-term cost to the Federal Government of a Federal credit instrument, as calculated on a net present value basis, excluding administrative costs and any incidental effects on governmental receipts or outlays in accordance with the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (2 U.S.C. 661 et seq.).30

The subsidy amount, which is often expressed in percentage terms or as a ratio (i.e., subsidy rate), largely determines the amount of credit assistance that can be made available to project sponsors.31 For example, if a project's subsidy rate is 10% and is the only charge against available budget authority, a $20 million budgetary allocation could theoretically support a $200 million loan. A lower subsidy rate would support a larger loan amount.

As a reference point, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) identified a TIFIA subsidy rate of 6.30% for direct loans in FY2020.32 Proponents of WIFIA have argued that loans for water projects are likely to be less risky than transportation projects, because water utility collections for services (i.e., water rates) provide an established revenue stream and repayment mechanism; thus the subsidy cost would be lower and the amount of credit assistance higher (per dollar of budget authority).33 Adding caution, however, analysts note that, even with stable revenue mechanisms, some communities and water utilities have recently experienced problems with borrowing and bond repayments, so repayment of a WIFIA loan is not a certainty.34

In the Trump Administration's FY2020 budget proposal, OMB estimated a 0.91% subsidy rate for WIFIA.35 This equates to a 1:110 ratio. At this subsidy rate, a $10 million appropriation could support a direct loan (or loans) totaling $1.10 billion. However, this subsidy rate is an estimate for budgetary purposes. In the context of WIFIA implementation, subsidy rates are project-specific.36 EPA stated that the subsidy rate

is used for budgetary purposes and provides an estimate for what will be available for loans each year based on the anticipated riskiness of the future loan portfolio. The actual ratio will be determined for each project at the time of loan obligation. Project A with a higher credit quality would consume less of the credit subsidy than Project B with a lower credit quality, even if the projects are otherwise identical. Each applicant will be scored independently.37

Loan Interest Rates and Default Risk

The WIFIA program provides capital at a low cost to the borrower, because even though the interest on 30-year Treasury securities is taxable, Treasury rates can be less expensive than rates on traditional tax-exempt municipal debt. Moreover, WIFIA financing may be characterized as patient capital, because loan repayment does not need to begin until five years after substantial completion of a project, the loan can be for up to 35 years from substantial completion, and the amortization schedule can be flexible. In addition, there is less perceived investment risk, because the project has been determined to be creditworthy (i.e., there is a revenue stream for repayment).

Additionally, the WIFIA program has the potential to limit the federal government's exposure to default by relying on market discipline through creditworthiness standards and encouraging private capital investment.

On the other hand, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has argued38 that the federal government underestimates the cost of providing credit assistance under such programs because it excludes

the cost of market risk—the compensation that investors require for the uncertainty of expected but risky cash flows. The reason is that the [Federal Credit Reform Act] requires analysts to calculate present values by discounting expected cash flows at the interest rate on risk-free Treasury securities (the rate at which the government borrows money). In contrast, private financial institutions use risk-adjusted discount rates to calculate present values.39

In an effort to encourage nonfederal and private sector financing, WIFIA funding assistance generally cannot exceed 49% of project costs. In addition, WIFIA limits all sources of federal assistance to no more than 80% of a project's cost.

Interactions with Existing Water Financing Programs

In general, the WIFIA program is designed to support larger infrastructure projects with eligible costs exceeding $20 million. For this reason, some have argued that the WIFIA program complements existing water infrastructure financing tools—SRF programs under the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act—which are often used for smaller-scale projects.

Policymakers set a lower minimum threshold for project costs ($5 million) for WIFIA projects in communities with populations less than 25,000. One of 12 projects selected in the FY2017 funding round is located in a less populous community (Morro Bay, CA).40 Two of the 39 projects in the FY2018 funding round are located in less populous communities (Frontenac, KS, and Cortland, NY).

Generally, the level of interest from less populous communities in WIFIA financing is uncertain, particularly considering the other financing options that may be available. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has a variety of water and waste disposal programs to provide loans and grants for wastewater and drinking water infrastructure in rural communities (10,000 people or fewer). In addition, both of the SRF programs authorize states to provide subsidized financial assistance—such as principal forgiveness, negative interest loans, or a combination—under certain conditions.41 Appropriations acts in recent years have required states to use minimum percentages of their federal grant amounts to provide additional subsidization. The FY2019 appropriations act requires 10% of the CWSRF grants and 20% of the DWSRF grants to be used "to provide additional subsidy to eligible recipients in the form of forgiveness of principal, negative interest loans, or grants (or any combination of these)."

WIFIA financing can potentially support smaller projects by grouping, or aggregating, them through a single application for financial assistance. For example, during the first round of WIFIA funding (FY2017), one of the 12 entities selected to submit a loan application was the Indiana Finance Authority, which administers the clean water and drinking water SRF programs in Indiana. Indiana's prospective WIFIA loan would provide $436 million to support multiple projects in the state.

A major source of debate among opponents and proponents has been and continues to be potential impacts of WIFIA on funds for the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act SRF programs. Several groups representing state environmental officials opposed the establishment of a WIFIA program (in the 113th Congress). They argued that WIFIA funding could result in reduced spending on the SRF programs, which are capitalized by federal appropriations. States are concerned that WIFIA would likely be funded (through congressional appropriations) to the detriment of the SRF programs.42

On the other hand, water utility groups that support WIFIA have argued that it would complement, not harm, existing SRF programs. In their view, WIFIA will provide a new funding opportunity for large water infrastructure projects that are unlikely to receive SRF assistance.43 As described above, in part to address concerns about impacts of WIFIA on the SRF programs, WIFIA requires EPA to notify state infrastructure financing authorities about WIFIA application and gives state infrastructure financing authorities an opportunity to commit funds to the project. Nevertheless, some states and environmental advocacy groups remain concerned that WIFIA will compete with SRFs for congressional funding and that WIFIA will not prioritize public health or affordability, as the SRFs can. The 2016 Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act includes a "sense of the Congress" that WIFIA funding should be in addition to robust funding for the SRFs.44

Potential Federal Revenue Loss from Tax-Exempt Bonds

Enacting the WIFIA program raised a federal budgetary and revenue issue. Legislation reported by congressional committees is typically scored by the CBO for the effects on discretionary and mandatory, or direct, spending and by the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) for effects on revenue. The initial CBO cost estimate for S. 601, as approved by the Environment and Public Works Committee in April 2013, concluded that the WIFIA provisions would cost $260 million over five years. In addition, it would result in certain revenue loss to the U.S. Treasury; thus, pay-as-you-go procedures would have applied to the bill.45 CBO cited the JCT estimate that enactment of the bill would reduce revenues by $135 million over 10 years, because states would be expected to issue tax-exempt bonds for water projects in order to acquire additional funds not covered by WIFIA assistance.46 To avoid the pay-as-you-go requirement in the bill, the committee added a provision to S. 601 to prohibit recipients of WIFIA assistance from issuing tax-exempt bonds for the non-WIFIA portions of project costs. CBO re-estimated the bill and concluded that, because the change would make the WIFIA program less attractive to entities, most of which rely on tax-exempt bonds for project financing, the cost of the bill would be $200 million less over five years. CBO also said that the bill would have no impact on revenues, because the demand for federal credit would be lower without the option of using tax-exempt financing.47 WRRDA 2014 retained the bar on tax-exempt financing for WIFIA-assisted projects. Thus, the apparent solution to one issue in the legislation—potential revenue loss to the U.S. Treasury—raised a different kind of issue for entities seeking WIFIA credit assistance, because tax-exempt municipal bonds are the principal mechanism used by local governments to finance water infrastructure projects.

The restriction was widely criticized by potential users of WIFIA assistance. In their view, the bond financing restriction in WRRDA 2014, together with the provision that caps WIFIA assistance at 49% of project costs, would make it very difficult to finance needed projects. Congressional interest in addressing the tax-exempt bond restriction was soon evident. For example, H.R. 1710 in the 114th Congress proposed to make an exception from the limitation on use of tax-exempt bonds for WIFIA loans made to finance water infrastructure projects in states in which the governor has issued a state of drought emergency declaration.

More generally, in July 2015, the Senate passed H.R. 22, a bill to reauthorize highway and transportation programs for six years. It included repeal of the provision in P.L. 113-121 that limits any project receiving federal credit assistance under the WIFIA program from being financed with tax-exempt bonds. However, repeal of the provision raised similar revenue questions to those that arose in connection with P.L. 113-121. CBO's report on S. 1647 (the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee's bill, which was the basis of Senate-passed H.R. 22)48 stated that the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that repealing the WIFIA limitation would increase states' issuance of tax-exempt bonds for water projects and would decrease federal revenues by $17 million over the FY2016-FY2025 period. Further, CBO estimated that the change would increase demand for federal credit under the WIFIA program, resulting in additional spending stemming from the appropriation levels authorized in P.L. 113-121. Consequently, CBO estimated that implementing the WIFIA program would cost $146 million over the FY2016-FY2025 period.49

The issue of identifying offsets, or "pay-fors," for the estimated federal revenue loss was addressed in the conference agreement on H.R. 22, the FAST Act (P.L. 114-94). CBO estimated that the conference agreement included offsets to fully cover the cost of the bill by reducing spending or raising revenues.50 Thus, the enacted bill retained the provision repealing the tax-exempt bond financing restriction on WIFIA assistance.