Introduction

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is an agency within the Department of Defense with both military and civil works responsibilities. The agency's civil works mission has evolved with the changing needs of the nation. It began with improving and regulating navigation channels thereby facilitating the movement of goods between states and for import and export. Congress then charged the agency to help in reducing the damages from floods. More recently, Congress has authorized the agency to restore aquatic ecosystems. USACE operates more than 700 dams; has built 14,500 miles of levees; and improves and maintains more than 900 coastal, Great Lakes, and inland harbors, as well as 12,000 miles of inland waterways.1

Congress directs and oversees the specific navigation, flood control, and ecosystem restoration projects that USACE plans and constructs through authorization legislation, annual and supplemental appropriations legislation, and oversight efforts. The agency typically is working with nonfederal project sponsors in the development of these water resource projects. The demand for USACE projects typically exceeds the federal appropriations for these projects.

Broadly, Congress is faced with considering how well the nation is addressing its water resource needs and what is the current and future role of USACE in addressing those needs. Part of the issue is how effective, efficient, and equitable is the USACE project delivery process in meeting the nation's needs. Unlike with federal funding for highways and municipal water infrastructure, the majority of federal funds provided to USACE for water resource projects are not distributed by formula to states or through competitive grant programs. Instead, USACE is directly engaged in the planning and construction of projects; the majority of its appropriations are used performing work on specific studies and contracting for construction of projects authorized by Congress.

Scope and Structure of Report

This report examines the standard development and delivery of a USACE water resource project (e.g., steps in the process, role of Congress, nonfederal project sponsor role). It also presents the evolving alternative project delivery and innovative finance options. This report provides an overview of USACE water resource authorization and project delivery processes and selected related issues. The report discusses the following topics:

- primer on the agency and its authorization legislation, typically titled as a Water Resources Development Act (WRDA);

- standard process for planning and construction of USACE water resource projects;

- interest in and authorities for alternative project delivery and innovative finance for water resource projects; and

- other USACE authorities, including its authorities for Continuing Authorities Programs (CAPs) and technical assistance, emergency response, and reimbursable work.

Appendix A describes the evolution of USACE water resource missions and authorities. Appendix B provides an overview of Water Resources Development Acts and other USACE civil works omnibus authorization bills enacted from 1986 through 2018, which are collectively referred to herein as WRDAs.

Primer on the Agency and Its Authorization

The civil works program is led by a civilian Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works, who reports to the Secretary of the Army.2 A military Chief of Engineers oversees the agency's civil and military operations and reports on civil works matters to the Assistant Secretary for Civil Works. A civilian Director of Civil Works reports to the Chief of Engineers. The agency's civil works responsibilities are organized under eight divisions, which are further divided into 38 districts.3 The districts and divisions perform both military and civil works activities and are led by Army officers.4 An officer typically is in a specific district or division leadership position for two to three years; a Chief of Engineers often serves for roughly four years. In 2018, the Trump Administration has expressed interest in the possibility of removing USACE from the Department of Defense;5 for more information on the status of this proposal, see "Proposals on Reorganizing USACE Functions" later in this report.

Local interests and Members of Congress often are particularly interested in USACE pursuing a project because these projects can have significant local and regional economic benefits and environmental effects. In recent decades, Congress has legislated on most USACE authorizations through WRDAs.6 Congress uses WRDA legislation to authorize USACE water resource studies, projects, and programs and to establish policies (e.g., nonfederal cost-share requirements). WRDAs generally authorize new activities that are added to the pool of existing authorized activities.7 The authorization can be project-specific, programmatic, or general. Most project-specific authorizations in WRDAs fall into three general categories: project studies, construction projects, and modifications to existing projects. WRDAs also have deauthorized projects and established deauthorization processes. A limited set of USACE authorizations expire unless a subsequent WRDA extends the authorizations.

Generally, a study or construction authorization by itself is insufficient for USACE to proceed. For the most part, the agency can only pursue what it is both authorized and funded to perform. Federal funding for USACE civil works activities generally is provided in annual Energy and Water Development appropriations acts and at times through supplemental appropriations acts. Over the last decade, annual USACE appropriations have ranged from $4.7 billion in FY2013 to $7.0 billion in FY2019. An increasing share of the appropriations has been used for operation and maintenance (O&M) of USACE owned and operated projects. In recent years, Congress has directed more than 50% of the enacted annual appropriations to O&M and limited the number of new studies and construction projects initiated with annual appropriations. For more on USACE appropriations, see the following:

- CRS Report R45326, Army Corps of Engineers Annual and Supplemental Appropriations: Issues for Congress, by Nicole T. Carter;

- CRS In Focus IF10864, Army Corps of Engineers: FY2019 Appropriations, by Nicole T. Carter; and

- CRS In Focus IF11137, Army Corps of Engineers: FY2020 Appropriations, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand.

The agency identified a $98 billion backlog of projects that have construction authorization that are under construction or are awaiting construction funding.8 That is, the rate at which Congress authorizes USACE to perform work has exceeded the work that can be accomplished with the agency's appropriations. For context, annual appropriations for construction funding in FY2018 and FY2019 were $2.1 billion and $2.2 billion, respectively. Given that USACE starts only a few construction projects using discretionary appropriations in a fiscal year (e.g., five using annual appropriations provided in FY2019), numerous projects authorized for construction in previous WRDAs remain unfunded. USACE may have hundreds of authorized studies that are not currently funded, and few new studies are funded annually. Congress allowed USACE to initiate six new studies using FY2019 appropriations.9

USACE Authorization Legislation: 1986 to Present Process

1986 to 2014

Beginning with WRDA 1986 (P.L. 99-662), Congress loosely followed a biennial WRDA cycle for a number of years. WRDAs were enacted in 1988 (P.L. 100-676), 1990 (P.L. 101-640), 1992 (P.L. 102-580), 1996 (P.L. 104-303), 1999 (P.L. 106-53), and 2000 (P.L. 106-541). Deliberations on authorization of particular USACE projects and interest in altering how the agency developed, economically justified, and mitigated for its projects resulted extended beyond the biennial cycle, Congress enacting the next WRDA in 2007 (P.L. 110-114). Congress did not enact a WRDA for a number of years following WRDA 2007. An issue that complicated enactment was devising a way to develop an omnibus water authorization bill that identified specific studies and projects to authorize and modify, as congressionally directed spending (known as earmarks) received increasing scrutiny.

2014

The Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (WRRDA 2014; P.L. 113-121) was enacted in June 2014.10 It authorized 34 construction projects that had received agency review, had Chief of Engineers reports (also known as Chief's reports), and had been the subject of a congressional hearing, thereby overcoming most concerns related to earmarks in the legislation. WRRDA 2014 also created a new process for identifying nonfederal interest in and support for USACE studies and projects. For more on WRRDA 2014, see CRS Report R43298, Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014: Comparison of Select Provisions, by Nicole T. Carter et al.

2016, 2018, and the Section 7001 Annual Report Process

In Section 7001 of WRRDA 2014, Congress called for the Secretary of the Army to submit an annual report to the congressional authorizing committees—the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee and the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee—of potential and publicly submitted study and project authorization proposals for Congress to consider for authorization.11 The process to develop and transmit this report, referred to as the Section 7001 process, provides Congress a means by which to identify new studies and other activities for potential inclusion in an omnibus authorization bill. The Assistant Secretary of the Army delivered to Congress a Section 7001 annual report in February 2015, February 2016, March 2017, and February 2018.12 A notice requesting public submissions for consideration for the fifth Section 7001 annual report was published on April 20, 2018.13 USACE accepted submissions through August 20, 2018. These submissions are to be considered for inclusion in the annual report expected to be delivered to the authorizing committees in mid-2019. USACE has indicated that the next call for submissions is expected to open in May 2019.

With WRDA 2016, which was Title I of the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act (WIIN; P.L. 114-322, enacted in December 2016), Congress returned enactment of USACE authorization legislation to a biennial timeframe. WRDA 2016 authorized new studies based on proposals in the Section 7001 reports and construction projects based on Chief's reports.

The 115th Congress enacted America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 (AWIA 2018, P.L. 115-270) in October 2018. AWIA 2018 includes the Water Resources Development Act of 2018 (WRDA 2018) as Title I of the bill.14 Like WRDA 2016, Congress used the Section 7001 reports to identify new studies, and Chief's reports to identify the construction projects that Congress authorized in WRDA 2018.

Future Authorization Legislation

Like previous Congresses, the 116th Congress may consider WRDA legislation. These deliberations are likely to be shaped by many factors, such as policy proposals by the President, congressional policies on earmarks, and development of an infrastructure initiative or other actions or developments that may alter the framework and context for federal and nonfederal investments. Congress also may have available various reports to inform its WRDA development and deliberations. In addition to the Section 7001 reports and Chief's reports, the authorizing committees receive annually a report required by Section 1002 of WRRDA 2014. The Section 1002 report identifies when USACE feasibility studies—the detailed studies of the water resource problem that are developed to inform the Chief's report and congressional authorization—are anticipated to reach various milestones.15 At the start of FY2019, USACE currently had roughly 100 active feasibility studies.16 In addition to feasibility studies, Congress may be presented with other types of studies recommending actions that require congressional authorization. These studies include postauthorization change reports for modifying an authorized project prior to or during construction, reevaluation reports for a modification to a constructed project, and reports recommending deauthorization of constructed projects that no longer serve their authorized purposes. Reports and analyses by Government Accountability Office (GAO), Inspector Generals, Congressional Budget Office, National Academy of Sciences (NAS), National Academy of Public Administration,17 Inland Waterway Users Board,18 Environmental Advisory Board to the Chief of Engineers, 19 advocacy and industry groups, and others also may influence congressional deliberations.

Efforts to Shape the Future of USACE

Proposals on Reorganizing USACE Functions

In June 2018, the Trump Administration proposed to move the civil works activities from the Department of Defense to the Department of Transportation and the Department of the Interior to consolidate and align the USACE civil works missions with these agencies.20 Although some Members of Congress have indicated support for looking at which USACE functions may not need to be in the Department of Defense,21 the conference report that accompanied the USACE appropriations for FY2019 (P.L. 115-244), H.Rept. 115-929, stated the following:

The conferees are opposed to the proposed reorganization as it could ultimately have detrimental impacts for implementation of the Civil Works program and for numerous non-federal entities that rely on the Corps' technical expertise, including in response to natural disasters.… Further, this type of proposal, as the Department of Defense and the Corps are well aware, will require enactment of legislation, which has neither been proposed nor requested to date. Therefore, no funds provided in the Act or any previous Act to any agency shall be used to implement this proposal.22

As previously noted, USACE's central civil works responsibilities are to support coastal and inland commercial navigation, reduce riverine flood and coastal storm damage, and protect and restore aquatic ecosystems in U.S. states and territories. Additional project benefits also may be developed, including water supply, hydropower, recreation, fish and wildlife enhancement, and so on. In addition, USACE has certain regulatory responsibilities that Congress has assigned to the Secretary of the Army; these responsibilities include issuing permits for private actions that may affect navigation, wetlands, and other waters of the United States. As part of its military and civil responsibilities and under the National Response Framework, USACE participates in emergency response activities (see "Natural Disaster and Emergency Response Activities" section of this report). For more information on USACE civil works responsibilities, see Appendix A.

The Trump Administration has not provided additional details on its June 2018 reorganization proposal for USACE in subsequent public documents. More recently, USACE and the Assistant Secretary of the Army have focused their attention on efforts to "revolutionize USACE civil works" as part of the Trump Administration's reform of how infrastructure projects are regulated, funded, delivered, and maintained.23 The three objectives of the effort are: (1) accelerate USACE project delivery, (2) transform project financing and budgeting, and (3) regulatory reform (e.g., improve the permitting process). For more on how USACE projects are delivered and how options for project delivery and financing have changed, see "Standard Project Delivery Process" and "Alternative Project Delivery and Innovative Finance," respectively.

WRDA 2018 Studies on Future of USACE and Economic Evaluation of Projects

The 115th Congress enacted provisions that support receiving information to inform discussions about improving the project delivery and budgeting for projects. In WRDA 2018, Congress included the following provisions: Section 1102, Study of the Future of the United States Army Corps of Engineers; and Section 1103, Study on Economic and Budgetary Analyses.

In Section 1102 of WRDA 2018, Congress required that the Secretary of the Army to contract with the National Academy of Sciences to evaluate the following:

- USACE's ability of carry out its mission and responsibilities and the potential effects of transferring functions and resources from the Department of Defense to a new or existing federal agency; and

- how to improve USACE's project delivery, taking into account the annual appropriations process, the leadership and geographic structure at the divisions and districts, and the rotation of senior USACE leaders.

The legislation requires that the study be completed within two years of enactment (which would be October 2020).

In Section 1103 of WRDA 2018, Congress required that the Secretary of the Army contract with the NAS to do the following:

- review the economic principles and methods used by the USACE to formulate, evaluate, and budget for water resources development projects, and

- recommend changes to improve transparency, return on federal investment, cost savings, and prioritization in USACE budgeting of these projects.

Standard Project Delivery Process

Standard USACE project delivery consists of the agency leading the study, design, and construction of authorized water resource projects. Nonfederal project sponsors typically share in study and construction costs, providing the land and other real estate interests, and identifying locally preferred alternatives. Since the 1950s, questions related to how project beneficiaries and sponsors should share in the cost and delivery of USACE projects have been the subject of debate and negotiation. Much of the basic arrangement for how costs and responsibilities are currently shared was established by Congress in the 1980s, with adjustments in subsequent legislation, including in recent statutes.

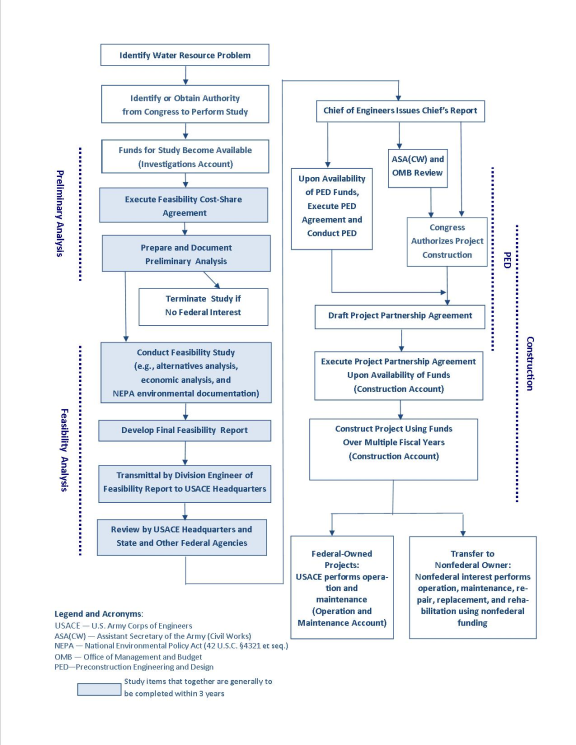

Congressional authorization and appropriations processes are critical actions in a multistep process to deliver a USACE project. This section describes the standard delivery process for most USACE projects, which consists of the following basic steps:

- Congressional study authorization is obtained in a WRDA or similar authorization legislation.24

- USACE performs a feasibility study, if funds are appropriated.

- Congressional construction authorization is pursued. USACE can perform preconstruction engineering and design while awaiting construction authorization, if funds are appropriated.

- Congress authorizes construction in a WRDA or similar authorization legislation, and USACE constructs the project, if funds are appropriated.25

The process is not automatic. Appropriations are required to perform studies and construction; that is, congressional study and construction authorizations are necessary but insufficient for USACE to proceed. Major steps in the process are shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1. Major Steps in USACE Project Development and Delivery Process |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS). |

For most water resource activities, USACE needs a nonfederal sponsor to share the study and construction costs. Since WRDA 1986, nonfederal sponsors have been responsible for funding a portion of studies and construction, and they may be 100% responsible for O&M and repair of certain types of projects (e.g., flood risk reduction and aquatic ecosystem restoration). Most flood risk reduction and ecosystem restoration projects are transferred to nonfederal owners after construction; many navigation and multipurpose dams are federally owned and operated.

Nonfederal sponsors generally are state, tribal, territory, county, or local agencies or governments. Although sponsors typically need to have some taxing authority, Congress has authorized that some USACE activities can have nonprofit and other entities as the nonfederal project sponsor; a few authorities allow for private entities as partners.

Table 1 provides general information on the duration and federal share of costs for various phases in USACE project delivery. Project delivery often takes longer than the combined duration of each phase shown in Table 1 because some phases require congressional authorization before they can begin and action on each step is subject to the availability of appropriations.

|

Feasibility Study |

Preconstruction Engineering and Design (PED) |

Construction |

Operation & Maintenance |

||||

|

Avg. Duration, Once Congressionally Authorized and Fundeda |

3 yearsb |

Approx. 2 years |

Varies |

Authorized project duration |

|||

|

Federal Share of Costs |

50%c (except 100% for inland waterways) |

Varies by |

Varies, see Table 2 |

Varies, see Table 2 |

Source: CRS.

a. Generally, projects take longer than the duration of the individual steps. Some steps require congressional authorization before they can begin, and action on each step is subject to availability of appropriations.

b. The Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (WRRDA 2014; P.L. 113-121) requires most feasibility studies to be completed within three years of initiation and to have a maximum federal cost of $3 million. It also deauthorizes any feasibility study not completed seven years after initiation (see "Deauthorization of Studies".

c. Prior to WRRDA 2014, the preliminary analysis was included within a reconnaissance study that was produced at 100% federal expense.

d. Generally, PED cost shares are the same as construction cost shares shown in Table 2.

Feasibility Study and Chief's Report

A USACE water resource project starts with a feasibility study (sometimes referred to as an investigation) of the water resource issue and an evaluation of the alternatives to address the issue. The purpose of the USACE study process is to inform federal decisions on whether there is a federal interest in authorizing a USACE construction project. USACE generally requires two types of congressional action to initiate a study—study authorization and then appropriations. Congress generally authorizes USACE studies in WRDA legislation.26

Once a study is authorized, appropriations are sought from monies generally provided in the annual Energy and Water Development appropriations acts. Within USACE, projects are largely planned at the district level and approved at the division level and USACE headquarters. Early in the study process, USACE assesses the level of interest and support of nonfederal entities that may be potential sponsors that share project costs and other responsibilities. USACE also investigates the nature of the water resource problem and assesses the federal government's interest.

If USACE recommends proceeding and a nonfederal sponsor is willing to contribute to the study, a feasibility study begins. The cost of the feasibility study (including related environmental studies) is split equally between USACE and the nonfederal project sponsor, as shown in Table 1. The objective of the feasibility study is to formulate and recommend solutions to the identified water resource problem. During the first few months of a feasibility study, the local USACE district formulates alternative plans, investigates engineering feasibility, conducts benefit-cost analyses, and assesses environmental impacts under the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA; 42 U.S.C. §4321). (For more information on NEPA compliance and cost-benefit analyses, see the box "USACE Feasibility Studies: National Environmental Policy Act Compliance and Economic Analyses.") The evaluation of USACE water resource projects is governed by the 1983 Principles and Guidelines for Water and Related Resources Implementation Studies (often referred to as the P&G) and by policy direction provided in WRDA bills and other enacted legislation.27 An important outcome of the feasibility analysis is determination of whether the project warrants further federal investment.28 Under the P&G, the federal objective in planning generally is to contribute to national economic development (NED) consistent with protecting the nation's environment.29 A feasibility study generally identifies a tentatively preferred plan, which typically is the plan that maximizes the NED consistent with protecting the environment (referred to as the NED plan). The Assistant Secretary of the Army has the authority to grant an exception and recommend a plan other than the NED plan. In some circumstances, the nonfederal sponsor may support an alternative other than the NED plan, which is known as the locally preferred plan (LPP). If the LPP is recommended and authorized, the nonfederal entity is typically responsible for 100% of the difference in project costs (construction and operation and maintenance costs) between the LPP and the NED plan.

Once the final feasibility study is available, the Chief of Engineers signs a recommendation on the project, known as the Chief's report. USACE submits the completed Chief's reports to the congressional authorizing committees (33 U.S.C. §2282a) and transmits the reports to the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for Administration review. Since the mid-1990s, Congress has authorized many projects based on Chief's reports prior to completion of the project review by the Assistant Secretary and OMB.

|

USACE Feasibility Studies: National Environmental Policy Act Compliance NEPA Compliance. The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA; 42 U.S.C. §4321) requires federal agencies to fully consider a federal action's significant impacts on the quality of the human environment, and to inform the public of those impacts, before making a final decision. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) integrates its NEPA compliance process with the development of a feasibility study. That is, during the study process, USACE identifies impacts of potential project alternatives and any environmental requirements that may apply as a result of those impacts, and it takes action necessary to demonstrate compliance with those requirements. In Section 1005 of the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (WRRDA 2014; P.L. 113-121), titled Project Acceleration, Congress directed USACE to expedite NEPA environmental documentation compliance for USACE studies. In March 2018, USACE issued implementation guidance for this provision. USACE published implementation guidance for the categorical exclusion portion of Section 1005 in August 2016; the provision called for the agency to survey its use of categorical exclusions and to identify and publish new categorical exclusion categories that merit establishment. USACE has not established new categorical exclusion categories pursuant to Section 1005 of WRRDA 2014. For more information how USACE's study process is combined with its NEPA documentation compliance, see CRS Report R43209, Environmental Requirements Addressed During Corps Civil Works Project Planning: Background and Issues for Congress, by Linda Luther. Economic Analyses. Congress established federal policy for evaluating USACE projects in the Flood Control Act of 1936 (49 Stat. 1570) by stating that a project should be undertaken "if the benefits to whomsoever they may accrue are in excess of the estimated costs" and if a project is needed to improve the lives and security of the people. For flood risk reduction projects and navigation projects, USACE performs a benefit-cost analysis (BCA) to compare the economic benefits of project alternatives to the investment costs of those alternatives. For ecosystem restoration projects, USACE performs a cost-effectiveness analysis to evaluate for each project alternative its associated costs and its anticipated environmental benefits. Disagreement persists about various aspects of these analyses, including the use of BCAs in decision-making, how (and which) benefits and costs are captured and monetized, and how to value future benefits and costs (which relates to the use of a discount rate to evaluate how future costs and benefits are valued in the present). The quality and reliability of BCAs shape federal decision-making and the efficacy of federal and nonfederal spending on federal water resource projects. Executive branch budget-development guidance for USACE over the last decade has used a benefit-cost ratio (BCR) threshold as one of the primary performance metrics for selecting which construction projects to propose for funding. Recent requests have included ongoing projects that have benefits that are at least 2.5 times the project costs (i.e., BCR>2.5) or address a significant risk to human safety. In contrast, the threshold for an Administration recommendation for construction authorization is typically that the benefits exceed the costs (i.e., BCR>1). An issue for Congress and nonfederal project sponsors is the uncertain prospects for construction for the suite of congressionally authorized projects that do not meet the budget-development BCR threshold. Sources: USACE, Implementation Guidance for Section 1005(b) of the Water Resources Development Act (WRRDA) of 2014, Categorical Exclusions in Emergencies, memorandum, August 5, 2016, at https://planning.erdc.dren.mil/toolbox/library/WRDA/WRRDA2014IGSection1005b.pdf; see CRS Report R44594, Discount Rates in the Economic Evaluation of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Projects, by Nicole T. Carter and Adam C. Nesbitt. |

Preconstruction Engineering and Design

USACE preconstruction engineering and design (PED) of a project may begin after the Chief's report subject to the availability of appropriations (33 U.S.C. §2287).30 PED consists of finalizing the project's design, preparing construction plans and specifications, and drafting construction contracts for advertisement. USACE work on PED is subject to the availability of USACE appropriations. Once funded, the average duration of PED is two years, but the duration varies widely depending on the size and complexity of a project. PED costs are distributed between the federal and nonfederal sponsor in the same proportion as the cost-share arrangement for the construction phase; see Table 2 for information on the cost-share requirements for construction.

|

Project Purpose |

Maximum Federal Share of Construction |

Maximum Federal Share of O&M |

||

|

Navigation |

||||

|

Harbors and Coastal Channels |

||||

|

improvements less than 20 ft. deep |

80%a |

100%b |

||

|

improvements between 20 ft. and 50 ft. deep |

65%a |

100%b |

||

|

improvements greater than 50 ft. deep |

40%a |

50%b |

||

|

Inland Waterways |

100%c |

100% |

||

|

Flood and Storm Damage Reduction |

||||

|

Inland Flood Control |

65% |

0% |

||

|

Coastal Hurricane and Storm Damage Reduction |

65% |

0% |

||

|

Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration |

65% |

0% |

||

|

Multipurpose Project Components |

||||

|

Hydroelectric Power |

0%e |

0% |

||

|

Municipal and Industrial Water Supply Storage |

0% |

0% |

||

|

Agricultural Water Supply Storage (typically irrigation water storage) |

65%f |

0% |

||

|

Recreation at USACE Facilities |

50% |

0% |

||

|

Aquatic Plant Control |

Not Applicable |

50% |

||

Source: CRS, using 33 U.S.C. §§2211-2215, unless otherwise specified below.

a. Percentages reflect that nonfederal sponsors pay the following: 10%, 25%, or 50% during construction, and an additional 10% over a period not to exceed 30 years.

b. For maintaining improvements up to 50 feet in depth, the maximum federal share is 100%; for maintaining the improvements that are at a depth over 50 feet, the costs are split 50% federal and 50% nonfederal. The majority of federal support for harbor maintenance is derived from the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund, which receives the collections from a harbor maintenance tax principally applied to commercial cargo imports at federally maintained ports.

c. Appropriations from the Inland Waterway Trust Fund, which is funded by a fuel tax on vessels engaged in commercial transport on designated waterways, are used for 50% of these costs. For more on this trust fund, see CRS In Focus IF10020, Inland Waterways Trust Fund, by Charles V. Stern and Nicole T. Carter.

d. Congressionally authorized beach nourishment components of coastal storm damage reduction projects consist of periodic placement of sand on beaches and dunes; most nourishment activities remain in the construction phase for 50 years.

e. Capital costs initially are federally funded and are to be 100% repaid by fees collected from power customers.

f. Unlike most other USACE project components, nonfederal agricultural water supply construction costs are initially federally funded if the USACE project is in the 17 western states where reclamation law applies. Repayment by nonfederal water users for agricultural water supply storage costs is subject to various conditions under the federal reclamation laws.

Construction and Operation and Maintenance

Once the project receives congressional construction authorization, federal funds for construction are sought in the annual appropriations process. Once construction funds are available, USACE typically functions as the project manager; that is, USACE staff, rather than the nonfederal project sponsor, usually are responsible for implementing construction. Although project management may be performed by USACE personnel, physical construction is contracted out to private engineering and construction contractors. When USACE manages construction, the agency typically pursues reimbursement of the nonfederal cost share during project construction.31 Post-construction ownership and operations responsibilities depend on the type of project. When construction is complete, USACE may own and operate the constructed project (e.g., navigation projects) or ownership and maintenance responsibilities may transfer to the nonfederal sponsor (e.g., most flood damage reduction projects).

The cost-share responsibilities for construction and O&M vary by project purpose, as shown in Table 2. Table 2 first provides the cost share for the primary project purposes of navigation, flood and storm damage reduction, and aquatic ecosystem restoration. Next, it provides the cost shares for additional project purposes, which can be added to a project that has at least one of the three primary purposes at its core. WRDA 1986 increased local cost-share requirements; some subsequent WRDAs further adjusted cost sharing. Deviation from the standard cost-sharing arrangements for individual projects is infrequent and typically requires specific authorization by Congress.32

Changes After Construction Authorization

A project may undergo some changes after authorization. If project features or estimated costs change significantly, additional congressional authorization may be necessary. Congressional authorization for a significant modification typically is sought in a WRDA. Requests for such modifications or for the study of such modifications also are solicited through the Section 7001 annual report process. For less significant modifications, additional authorization often is not necessary. Section 902 of WRDA 1986, as amended (33 U.S.C. §2280), generally allows for increases in total project costs of up to 20% (after accounting for inflation of construction costs) without additional congressional authorization.

Changes After Construction: Section 408 Permissions to Alter a USACE Project

If nonfederal entities are interested in altering USACE civil works projects after construction, the entity generally must obtain permission from USACE. The agency's authority to allow alterations to its projects derives from Section 14 of the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899, also known as Section 408 based on its codification at 33 U.S.C. §408. This provision states that the Secretary of the Army may "grant permission for the alteration or permanent occupation or use of any of the aforementioned public works when in the judgment of the Secretary such occupation or use will not be injurious to the public interest and will not impair the usefulness of such work."33 Pursuant to the regulations, USACE conducts a technical review of the proposed alteration's effects on the USACE project. Section 408 permissions may be required not only for projects operated and maintained by USACE, but also federally authorized civil works projects operated and maintained by nonfederal project sponsors (e.g., many USACE-constructed, locally maintained levees).34 At the end of the Section 408 process, USACE chooses to approve or deny permission for the alteration. USACE may attach conditions to its Section 408 permission.

Deauthorization Processes and Divestiture

Deauthorization of Projects

Most authorizations of USACE construction projects are not time limited. To manage the backlog of authorized projects that are not constructed, Congress has enacted various deauthorization processes.

- General Deauthorization Authority. Of the current deauthorization authorities for unconstructed projects, the oldest directs the Secretary of the Army to transmit to Congress annually a list of authorized projects and project elements that did not receive obligations of funding during the last five full fiscal years (33 U.S.C. §579a(b)(2)).35 If funds are not obligated for the planning, design, or construction of the project or project element during the following fiscal year, the project or project element is deauthorized.36 The final project deauthorization list is published in the Federal Register. The process is initiated when the Secretary of the Army transmits the list.

- WRDA 2018 One-Time Process. Section 1301 of WRDA 2018 created a one-time process to deauthorize at least $4 billion of authorized projects that are unconstructed and are "no longer viable for construction."37 This process can deauthorize unconstructed projects or project elements authorized prior to WRDA 2007, projects on the list produced pursuant to the general deauthorization authority (33 U.S.C. §579a(b)(2)), and unconstructed projects requested to be deauthorized by the nonfederal sponsor.

- WRDA 2016 One-Time Process. Section 1301 of WRDA 2016 created a one-time process to deauthorize projects with federal costs to complete of at least $10 billion that are "no longer viable for construction." This process can only deauthorize projects authorized prior to WRDA 2007.

- Projects Authorized in WRDA 2018, WRDA 2016, and WRRDA 2014. Section 1302 of WRDA 2018 requires that a project authorized in WRDA 2018 be automatically deauthorized if no funding had been obligated for its construction after 10 years of enactment (i.e., 10 years after October 2018), unless certain conditions apply). Section 1302 of WRDA 2016 requires that any project authorized in WRDA 2016 be automatically deauthorized if after 10 years of enactment (December 2026) no funding had been obligated for its construction, unless certain conditions apply. Section 6003 of WRRDA 2014, as amended by Sec. 1330 of WRDA 2018, requires that any project authorized in WRRDA 2014 be automatically deauthorized if after 10 years of enactment (June 2024) no funding had been obligated for its construction.38

USACE has not addressed uncertainties regarding how implementation of these authorities is to be coordinated.39

A separate divestiture process is used to dispose of constructed projects or project elements and other real property interests associated with civil works projects. Some divestitures also may require explicit congressional deauthorization. USACE divestitures historically either have been limited to projects or real property interests that no longer serve their authorized purposes (e.g., navigation channels that no longer have commercial navigation) or have been conducted pursuant to specific congressional direction. While Section 1301 of WRDA 2018 appears to provide a one-time opportunity for unconstructed projects to be deauthorized, there currently is no formal process similar to the Section 7001 annual report process for a nonfederal entity to propose that a constructed project be deauthorized.40 Congress has deauthorized unconstructed and constructed projects and project elements in WRDA legislation.

Deauthorization of Studies

There are two authorities for deauthorizing studies:

- The Secretary of the Army is directed to transmit to Congress annually a list of incomplete authorized studies that have not received appropriations for five full fiscal years (33 U.S.C. §2264). The study list is not required to be published in the Federal Register. Congress has 90 days after submission of the study list to appropriate funds for a study; otherwise, the study is deauthorized.

- WRRDA 2014, as amended by WRDA 2018, requires that a feasibility study that remains incomplete 10 years after initiation is automatically deauthorized.41

CRS has no data indicating that studies have been deauthorized through these processes in recent years. USACE has indicated that the agency is reviewing its 5,600 study authorities to identify studies for deauthorization.42

Alternative Project Delivery and Innovative Finance

Interest in Alternative Delivery

As nonfederal entities have become more involved in USACE projects and their funding, they have expressed frustration with the time it takes USACE to complete studies and construction. Delayed completion of water resource projects can postpone some or all of a project's anticipated benefits. The impact of these delays varies by the type of project. Delayed completion of flood risk reduction projects may prolong a community's vulnerability to certain coastal and riverine floods, thereby contributing to the potential cost of disaster response and recovery. Delayed investment in navigation projects may result in postponed transportation cost savings from improved efficiency and in greater reliance on road and rail transport. Delayed aquatic ecosystem restoration projects may result in missed opportunities to attenuate wetlands loss and realize related ecosystem benefits, such as those for water quality and fisheries.

Another concern with long project delivery is the potential for an increase in project costs. The Government Accountability Office in a 2013 report summarized its findings regarding cost growth at USACE flood control projects.43 GAO's detailed review of eight projects found that a factor contributing to cost increases at these USACE-led flood risk reduction projects was funding below the capability level. Other factors included design changes, initial USACE cost estimates being lower than later cost estimates, and differences in contract estimates and actual contract costs. When testifying in 2013, USACE Deputy Commanding General for Civil and Emergency Operations Major General Michael J. Walsh noted that how much funding is put toward a project significantly impacts the duration of project delivery.44

Although President Trump (as well as previous Presidents) and many Members of Congress have expressed interest in improving the nation's infrastructure, including its water resource infrastructure, balancing the potential benefits of such improvements and concerns about increased federal expenditures poses an ongoing challenge. While a subset of authorized USACE construction activities is included in the President's budget request and funded annually by congressional appropriations, numerous authorized USACE projects or project elements have not received federal construction funding.

Competition for USACE discretionary appropriations has increased interest in alternative project delivery and innovative financing, including private financing and public-private partnerships (P3s). In a June 21, 2017, memorandum, the agency's Director of Civil Works announced the initiation of a comprehensive review to identify opportunities to enhance project delivery, organizational efficiency, and effectiveness.45 Congress, particularly in WRRDA 2014, WRDA 2016, and WRDA 2018, has authorized and extended alternative ways to advance and deliver USACE studies and projects. To expand delivery options, Congress has increased the flexibility in the nonfederal funding of USACE-led activities, nonfederal leadership of USACE studies and projects, and P3s. It also has authorized new financing mechanisms for water resource projects. Some of these expanded delivery and financed options are discussed below.

Expansion of Delivery Options

WRRDA 2014 and WRDA 2016 expanded the authorities for nonfederal entities to perform studies and construct projects (or elements of projects) that typically would have been undertaken by USACE. These statutes also provided that the costs of these nonfederal-led activities are shared by the federal government largely as if USACE had performed them. That is, nonfederal entities advancing water resource projects may be eligible to receive credit or reimbursement (without interest) subject to the availability of federal appropriations for their investments that exceed the required nonfederal share of project costs.46 These authorities typically require that the nonfederal entity leading the project comply with the same laws and regulations that would apply if the work were being performed by USACE.

Private sector access to financing and expertise and experience with complex project management are all seen as potential advantages for the delivery of some types of public infrastructure. Interest has expanded in recent years in allowing private engagement in U.S. water resource projects, which would follow the models used in other U.S. infrastructure sectors, such as transportation, and in international examples of private provision of public infrastructure and related services. WRRDA 2014 directed USACE to establish pilot programs to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of allowing nonfederal applicants to carry out certain authorized projects. For example, WRRDA 2014 included the following:

- Section 5014 authorized a P3 pilot program,47 and

- Section 1043 authorized the transfer of federal funds to nonfederal entities to use for the construction of authorized USACE projects.48

The 116th Congress may consider water resource project financing and delivery during deliberations on USACE appropriations and authorization legislation, as well as during discussions of broader infrastructure initiatives. In H.Rept. 115-929, which accompanied USACE FY2019 appropriations, congressional appropriators directed USACE to continue to develop its policy approach for public-private partnerships. For a discussion of some of the issues that have impeded greater private-sector participation and P3 efforts for USACE and water resource projects (e.g., limitations on USACE entering into long-term contracts and challenges to assessing project-specific user fees) see CRS Testimony TE10023, America's Water Resources Infrastructure: Approaches to Enhanced Project Delivery, by Nicole T. Carter.

Under these authorities, additional nonfederal investments may, in the near term, achieve progress on some water resource projects, thereby potentially making federal funding available for other authorized USACE projects. However, additional nonfederal investment may have potential trade-offs for the federal government, including reduced federal influence over the set of studies and construction projects receiving, expecting, and eligible for federal support. Others raise concerns that these provisions alter how USACE funds are used by directing federal dollars toward projects with nonfederal sponsors that can provide more nonfederal funding upfront.49 A concern from the nonfederal perspective is the challenge of obtaining federal reimbursement.50

Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act

WRRDA 2014 in Sections 5021 through 5035 authorized the Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA), a program to provide direct loans and loan guarantees for identified categories of water projects. The WIFIA concept is modeled after a similar program that assists transportation projects: the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act, or TIFIA, program. Congress established WIFIA with roles for both USACE and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).51 EPA's WIFIA program is funded and operational; 52 USACE's WIFIA program remains in the development phase.

WIFIA authorized both agencies to provide assistance in the form of loans and loan guarantees, and it identified each agency to provide that assistance for certain types of water projects. Under the WIFIA program, USACE is authorized to provide WIFIA support for a number of different project types, such as flood damage reduction projects, hurricane and storm damage reduction projects, environmental restoration projects, coastal or inland harbor navigation improvement projects, inland and intracoastal waterways navigation projects, or a combination of these projects. WRRDA 2014 included a number of project selection criteria that would affect whether individual projects are eligible to receive USACE WIFIA funding.

WRDA 2018 amended the WIFIA authorization of appropriations provided by WRRDA 2014. WRRDA 2014 authorized WIFIA appropriations for each of FY2015 through FY2019 for $50 million for each of the EPA Administrator and the Secretary of the Army. WRDA 2018 added an authorization of appropriations for the EPA Administration for $50 million for each of FY2020 and FY2021.

Implementation of WIFIA requires congressional appropriations to cover administrative expenses (i.e., "start-up" costs) and subsidy costs (i.e., the presumed default rate on guaranteed loans). Each agency also must promulgate regulations for the implementation of its WIFIA program. EPA has developed its regulations; USACE has not. The Administration has requested and Congress has provided funds for EPA's WIFIA. EPA is implementing its WIFIA authority. In contrast, the Administration had not requested funding for USACE's WIFIA start-up costs. Congress has directed USACE to develop the structure for its WIFIA program; however, the USACE WIFIA program has not advanced sufficiently to be operational. In H.Rept. 115-929 for FY2019, congressional appropriators directed USACE to continue to develop its WIFIA proposals for future budget submissions and to allow for WIFIA development expenses to be funded through the USACE Expenses account. Similar to recent years, the President's FY2020 request did not request funding for USACE's WIFIA. For a discussion of issues related to USACE implementation of WIFIA, see CRS Testimony TE10023, America's Water Resources Infrastructure: Approaches to Enhanced Project Delivery, by Nicole T. Carter.

Other USACE Authorities and Activities

There are exceptions to the standard project delivery process described above. USACE has some general authorities to undertake small projects, technical assistance, and emergency actions. Congress also has specifically authorized USACE to undertake numerous municipal water and wastewater projects. USACE also performs work on a reimbursable basis for other agencies and entities. These additional authorities are described below.

Small Projects Under Continuing Authorities Programs

The agency's authorities to undertake small projects are called Continuing Authorities Programs (CAPs). Projects under these authorities can be conducted without project-specific congressional study or construction authorization and without project-specific appropriations; these activities are performed at USACE's discretion without the need for inclusion in the Section 7001 reports. According to USACE, once funded, CAP projects generally take three years from feasibility phase initiation to construction completion. For most CAP authorities, Congress has limited the project size and scope as shown in Table 3.53 The CAPs typically are referred to by the section number in the bill in which the CAP was first authorized. WRRDA 2014 requires the Assistant Secretary of the Army to publish prioritization criteria for the CAPs and an annual CAP report.54 For more information, see CRS In Focus IF11106, Army Corps of Engineers: Continuing Authorities Programs, by Anna E. Normand.

Table 3. Selected USACE Continuing Authorities Programs (CAPs) for Small Projects and Recent Enacted and Requested Appropriations

(in millions of dollars)

|

Common Name of CAP Authority |

Eligible Activities and U.S. Code Citation |

Max. Federal Cost Share |

Per-Project Federal Limit |

Annual Federal Program Limit |

FY2019, FY2018, and |

FY2020 Request |

|

§14 |

Streambank and shoreline erosion of public works and nonprofit services; |

65% |

$5.0 |

$25.00 |

$8.0 |

$0.0 |

|

§103 |

Beach erosion/hurricane storm damage reduction; |

65% |

$10.0 |

$37.50 |

$4.0 |

$0.0 |

|

§107 |

Navigation improvements; |

Varies |

$10.0 |

$62.50 |

$8.0 |

$0.0 |

|

§111 |

Prevention/mitigation of shore damage by federal navigation projects; |

Same as the project causing the damage |

$12.5 |

Not Applicable |

$8.0 |

$0.0 |

|

§204 |

Regional sediment management/beneficial use of dredged material; |

65% |

$10.0 |

$62.50 |

$10.0 |

$1.0 |

|

§205 |

Flood control (including ice jam prevention); |

65% |

$10.0 |

$68.75 |

$8.0 |

$1.0 |

|

§206 |

Aquatic ecosystem restoration; |

65% |

$10.0 |

$62.50 |

$12.0 |

$1.0 |

|

§1135 |

Project modifications for improvement of the environment; |

75% |

$10.0 |

$50.00 |

$8.0 |

$1.0 |

Source: CRS, using statutes and USACE Engineer Regulation 1105-2-100.

Notes: CAPs that have not been funded in the most recent five fiscal years (e.g., §208 CAP [33 U.S.C. §701g] for the removal of obstructions and clearing channels for flood control) are not shown.

Planning and Technical Assistance and Tribal Programs

Congress has granted USACE some general authorities to provide technical assistance related to water resources planning and for floodplain management. Congress also has authorized USACE to provide technical and construction assistance to tribes. Except where noted in Table 4, USACE does not need project-specific authority to undertake activities under the authorities listed in Table 4.

|

Program |

Activities Authorized |

Max. Federal Cost Share |

Per-Project Federal Limit |

Annual Federal Program Limit |

FY2019, FY2018, and FY2017 |

FY2020 Request |

|

Planning Assistance to States |

Technical assistance to states, communities, and other eligible entities for comprehensive water resources planning, and eligible levee system evaluations of federally authorized levees; |

Varies |

$5.0 annually per state for comprehensive plans |

$30.0 for comprehensive plans |

$9.0 |

$5.0 |

|

Flood Plain Management Service |

Technical assistance on flood and floodplain issues; |

100% for eligible activities |

Not Applicable |

$50.0 |

$17.0 |

$15.0 |

|

Tribal Partnership Program |

Studies and construction of water resource development projects that benefit Indian tribes; |

50% for construction; |

$12.5; for projects above $12.5 project- specific congressional authorization is required |

Not Applicable |

$2.5 |

$0.5 |

Source: CRS.

Natural Disaster and Emergency Response Activities

National Response Framework

For assistance for presidentially declared disasters pursuant to the Stafford Act (P.L. 93-288), USACE may be tasked with performing various response and recovery activities. These activities are funded through the Disaster Relief Fund and performed at the direction of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the President and at the request of the governor of a state or territory with an affected area. Under the National Response Framework, USACE coordinates emergency support for public works and engineering. This support includes technical assistance, engineering, and construction management as well as emergency contracting, power, and repair of public water and wastewater and solid waste facilities.55 USACE also assists in monitoring and stabilizing damaged structures and in demolishing structures designated as immediate hazards to public health and safety. In addition, the agency provides technical assistance in clearing, removing, and disposing of contaminated and uncontaminated debris from public property and in establishing ground and water routes into affected areas. USACE coordinates contaminated debris management with EPA.56

Flood Fighting and Emergency Response

In addition to work performed as part of the National Response Framework, Congress has given USACE its own emergency response authority. This is commonly referred to as the agency's P.L. 84-99 authority, based on the act in which it was originally authorized, the Flood Control and Coastal Emergency Act (P.L. 84-99, 33 U.S.C. §701n). The act authorizes USACE to perform emergency response and disaster assistance.57 It also authorizes disaster preparedness, advance measures, emergency operations (disaster response and post-flood response), rehabilitation of certain damaged flood control works, protection or repair of certain federally authorized shore protection works threatened by coastal storms, emergency dredging, and flood-related rescue operations. These activities are limited to actions to save lives and protect improved property (public facilities/services and residential or commercial developments). USACE also has some authorities to assist with selected activities during drought.58

Most of the agency's emergency response work (including the repair program described below) generally is funded through supplemental appropriations provided directly to USACE. Until supplemental appropriations are provided, Congress has provided USACE with authority to transfer money from ongoing USACE projects to emergency operations (33 U.S.C. §701n).

Repair of Damaged Levees and Other Flood and Storm Projects

In P.L. 84-99, Congress authorized USACE to rehabilitate damaged flood control works (e.g., levees) and federally constructed hurricane or shore protection projects (e.g., federal beach nourishment projects) and to conduct related inspections. This authority is referred to as the Rehabilitation and Inspection Program (RIP). To be eligible for rehabilitation assistance, the project must be in active status at the time of damage by wind, wave, or water action other than ordinary nature.59 Active RIP status is maintained by proper project maintenance as determined during an annual or semiannual inspection and by the correction of deficiencies identified during periodic inspections.60 As of early 2017, RIP included around 1,100 projects consisting of 14,000 miles of levees and 33 dams.61

For locally constructed projects, 80% of the cost to repair the damage is paid using federal funds and 20% is paid by the levee or dam owner. For federally constructed projects, the entire repair cost is a federal responsibility (except the nonfederal sponsor is responsible for the cost of obtaining the sand or other material used in the repair). For damage to be repaired, USACE must determine that repair has a favorable benefit-cost ratio.62 Local sponsors assume any rehabilitation cost for damage to an active project attributable to deficient maintenance. WRDA 2016 allows that in conducting repair or restoration work under RIP, an increase in the level of protection can be made if the nonfederal sponsor pays for the additional protection.

Assistance for Environmental Infrastructure/Municipal Water and Wastewater

Since 1992, Congress has authorized and provided for USACE assistance with design and construction of municipal drinking water and wastewater infrastructure projects. This assistance has included treatment facilities, such as recycling and desalination plants; distribution and collection works, such as stormwater collection and recycled water distribution; and surface water protection and development projects. This assistance is broadly labeled environmental infrastructure at USACE.

Most USACE environmental infrastructure assistance is authorized for a specific geographic location (e.g., city, county, multiple counties) under Section 219 of WRDA 1992 (P.L. 102-580), as amended; however, other similar authorities, sometimes covering regions or states, exist in multiple sections of WRDAs and in selected Energy and Water Development Appropriations acts. The nature of USACE's involvement (e.g., a grant from USACE to the project owner or USACE acting as the construction project manager) and nonfederal cost share vary according to the specifics of the authorization. Most USACE environmental infrastructure assistance requires cost sharing, typically designated at 75% federal and 25% nonfederal; however, some of the assistance authorities are for 65% federal and 35% nonfederal cost sharing. Under Section 219, USACE performs the authorized work; for environmental infrastructure projects authorized in other provisions, USACE often can use appropriated funds to reimburse nonfederal sponsors for work they perform.

Since 1992, Congress has authorized USACE to contribute assistance to more than 300 of these projects and to state and regional programs, with authorizations of appropriations totaling more than $5 billion. WRRDA 2014 expanded authorizations and authorization of appropriations for specific multi-state environmental infrastructure activities. In WRDA 2016 and WRDA 2018, Congress expanded the Section 7001 process, allowing nonfederal entities to propose modifications to existing authorities for environmental infrastructure assistance. (For more on Section 7001 process, see "2016, 2018, and the Section 7001 Annual Report Process.")

Although no Administration has included environmental infrastructure in a USACE budget request since the first congressional authorization in 1992,63 Congress regularly includes USACE environmental infrastructure funds in appropriations bills. Congress provided $50 million in FY2015, $55 million in each of FY2016 and FY2017, $70 million in FY2018, and $77 million in FY2019. These funds are part of the "additional funding" provided by Congress in enacted appropriations bills. After enactment of an appropriations bill, the Administration follows guidance provided in the bill and accompanying reports to direct its use of these funds on authorized environmental infrastructure assistance activities. The selected environmental infrastructure assistance activities are identified in the agency's work plan for the fiscal year, which is typically available within two months after enactment of appropriations.64 Recently, funds have been used to continue ongoing environmental infrastructure assistance.

Because environmental infrastructure activities are not traditional USACE water resource projects, they are not subject to USACE planning process (e.g., a benefit-cost analysis and feasibility study are not performed). USACE environmental infrastructure assistance activities, however, are subject to federal laws, such as NEPA.

Reimbursable Work

In addition to its work for the Department of the Army under USACE's military program, USACE under various authorities also may perform work on a reimbursable basis for other DOD entities, federal agencies, states, tribes, local governments, and foreign governments. Other departments and agencies often call upon USACE's engineering and contracting expertise, as well as experience with land and water restoration and research and development.65 USACE contracts with private firms to perform most of the work.66 According to the Chief of Engineers in March 2019 testimony, USACE only accepts requests for reimbursable work that are deemed consistent with USACE's core technical expertise, are in the national interest, and that can be executed without impacting USACE's primary military and civil works missions.67

An example of reimbursable work include USACE's execution of contracts for EPA's efforts to remediate contaminated sites. Another example is USACE's contract management for border barrier and road construction at the U.S.-Mexico border for the Department of Homeland Security's Customs and Border Protection. USACE may perform this reimbursable work pursuant to broad authorities (e.g., Economy in Government Act, 31 U.S.C. §1535; Intergovernmental Cooperation Act, 31 U.S.C. §6505) or agency-specific authorities (e.g., 10 U.S.C §3036(e) known as the Chief's Economy Act).

Appendix A. Evolution of USACE Civil Works Responsibilities

The civil responsibilities of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) began with creating and regulating navigable channels and later flood control projects. Navigation projects include river deepening, channel widening, lock expansion, dam operations, and disposal of dredged material. Flood control projects are intended to reduce riverine and coastal storm damage; these projects range from levees and floodwalls to dams and river channelization. Many USACE projects are multipurpose—that is, they provide water supply, recreation, and hydropower in addition to navigation or flood control. USACE environmental activities involve wetlands and aquatic ecosystem restoration and environmental mitigation activities for USACE facilities. The agency's regulatory responsibility for navigable waters extends to issuing permits for private actions that might affect navigation, wetlands, and other waters of the United States.

Navigation and Flood Control (1802-1950s)

The agency's civil works mission developed in the 19th century. In 1824, Congress passed legislation charging military engineers with planning roads and canals to move goods and people. In 1850, Congress directed USACE to engage in its first planning exercise—flood control for the lower Mississippi River. In 1899, Congress directed the agency to regulate obstructions of navigable waters (see box titled "USACE Regulatory Activities: Permits and Their Authorities). During the 1920s, Congress expanded USACE's ability to incorporate hydropower into multipurpose projects and authorized the agency to undertake comprehensive surveys to establish river-basin development plans. The Flood Control Act of 1928 (70 Stat. 391) authorized USACE to construct flood control projects on the Mississippi and Tributaries (known as the MR&T project), and modified a 1917 authority for flood control project on the Sacramento River in California. The modern era of federal flood control emerged with the Flood Control Act of 1936 (49 Stat. 1570), which declared flood control a "proper" federal activity in the national interest. The 1944 Flood Control Act (33 U.S.C. §708) significantly augmented the agency's involvement in large multipurpose projects and authorized agreements for the temporary use of surplus water. The Flood Control Act of 1950 (33 U.S.C. §701n) began the agency's emergency operations through authorization for flood preparedness and emergency operations.68 The Water Supply Act of 1958 (43 U.S.C. §390b) gave USACE authority to include some reservoir storage for municipal and industrial water supply in reservoir projects at 100% nonfederal cost.

|

USACE Regulatory Activities: Permits and Their Authorities The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) has several regulatory responsibilities and issues several different types of permits. Sections 10 and 13 of the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899 (22 U.S.C. §407) require that a permit be obtained from USACE for alteration or obstruction of navigation and refuse discharge in U.S. navigable waters. USACE also has regulatory responsibilities under other laws, notably Section 404 of the Clean Water Act (33 U.S.C. §1344), which requires a permit for dredging or filling activities into waters of the United States. Since the mid-1960s, court decisions and administrative actions have altered the jurisdictional reach of the agency's regulatory program. USACE also regulates and authorizes disposal of materials into the ocean under the Marine Protection Research and Sanctuaries Act (33 U.S.C. §§1401-1455). For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10125, Overview of the Army Corps and EPA Rule to Define "Waters of the United States" (WOTUS) and Recent Developments, by Laura Gatz; CRS Report 97-223, The Army Corps of Engineers' Nationwide Permits Program: Issues and Regulatory Developments, by Nicole T. Carter; and CRS Report RS20028, Ocean Dumping Act: A Summary of the Law, by Claudia Copeland. |

Changing Priorities (1960-1985)

From 1970 to 1985, Congress authorized no major water projects, scaled back several authorized projects, and passed laws that altered project operations and water delivery programs to protect the environment. The 1970s marked a transformation in USACE project planning. The 1969 National Environmental Policy Act (42 U.S.C. §4321) and the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (16 U.S.C. §1531) required federal agencies to consider environmental impacts, increase public participation in planning, and consult with other federal agencies. Enactment in 1972 of what became the Clean Water Act also expanded the USACE's regulatory responsibilities; for more on the USACE role in implementing Section 404 of the Clean Water Act (33 U.S.C. §1344), see the text box "USACE Regulatory Activities: Permits and Their Authorities."

Executive orders (E.O. 11988 and E.O. 11990) united the goals of reducing flood losses and decreasing environmental damage by recognizing the value of wetlands and by requiring federal agencies to evaluate potential effects of actions on floodplains and to minimize wetlands impacts. Various dam failures and safety concerns in the United States—Buffalo Creek Dam (private), West Virginia in 1972; Reclamation's Teton Dam (Bureau of Reclamation), Idaho in 1976; and Kelly Barnes Dam (private), Georgia in 1977; among others—drew public and elected officials' attention. Much of the current federal dam safety framework developed out of executive orders and policies in the late 1970s and legislation in the 1980s. These include the USACE's lead role in the National Inventory of Dams; for more information, see the text box "National Inventory of Dams."

|

National Inventory of Dams The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) maintains a database of over 90,000 dams. The information in the database is self-reported by states and federal agencies. After several dam failures in the early 1970s, Congress authorized the USACE to inventory dams, along with other dam safety responsibilities, with the National Dam Inspection Act of 1972 (P.L. 92-367). The National Inventory of Dams (NID) was first published in 1975. The Water Resources Development Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-303) tasked the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) with various dam safety responsibilities including maintaining a National Dam Safety Program that among other things assists development of state dam safety programs which have responsibility for overseeing nonfederal dam safety, The legislation retained the NID as a USACE responsibility. Multiple bills have reauthorized the NID, most recently the Water Resources Development Act of 2018 (Title I of P.L. 115-270) extended the NID's annual authorization of appropriations of $500,000 through FY2023. USACE collaborates closely with FEMA and state regulatory programs to improve the accuracy and completeness of information with more recent emphasis on Emergency Action Plans and dam condition. Similar to other federal agencies, USACE is responsible for the dams the agency owns and operates. The NID can be accessed at https://nid-test.sec.usace.army.mil/. |

Environmental Mission and Nonfederal Responsibility (1986-2000)

Congress changed the rules for USACE water projects and their funding through the 1986 Water Resources Development Act (WRDA 1986; 33 U.S.C. §2211). WRDA 1986 established new cost-share formulas, resulting in greater financial and decision-making roles for nonfederal stakeholders. It also reestablished the tradition of biennial consideration of an omnibus USACE water resource authorization bill.

WRDA 1990 (33 U.S.C. §§1252, 2316) explicitly expanded the agency's mission to include environmental protection and increased its responsibility for contamination cleanup, dredged material disposal, and hazardous waste management. WRDA 1992 (33 U.S.C. §2326) authorized USACE to use the "spoils" from dredging in implementing projects for protecting, restoring, and creating aquatic and ecologically related habitats, including wetlands. WRDA 1996 (33 U.S.C. §2330) gave USACE limited programmatic authority to undertake aquatic ecosystem restoration projects. Although USACE has been involved with numerous environmental restoration projects in recent years, WRDA 2000 approved a restoration program for the Florida Everglades that represented the agency's first multiyear, multibillion-dollar effort of this type.

Evolving Demands and Processes (2001-present)

The agency's aging infrastructure and efforts to enhance the security of its infrastructure from terrorism and natural threats have expanded USACE activities in infrastructure rehabilitation, maintenance, and protection. USACE has been involved in significant flood-related disaster response and recovery activities, including following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Hurricane Sandy in 2012, and the 2017 hurricane season. WRDA 2007 included provision to expand levee safety efforts. USACE also has redirected its flood control activities to incorporate concepts of flood risk management and, more recently, flood resilience. The regularity with which USACE has received congressional appropriations for natural disaster response has increased attention to its role in emergency response, infrastructure repair, and post-disaster recovery and to the potential for nature-based flood risk reduction measures.69

WRDA 2007 continued the expansion of the agency's ecosystem restoration activities by authorizing billions of dollars for these activities, including large-scale restoration efforts in coastal Louisiana and the Upper Mississippi River. WRRDA 2014, WRDA 2016, and WRDA 2018 have expanded opportunities for nonfederal public and private participation in project delivery and financing and aimed to improve the efficiency of USACE planning activities.

Appendix B. Water Resources Development Acts from 1986 through 2018

This appendix provides an overview of omnibus U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) authorization legislation from 1986 to 2016. It first presents a table with the various pieces of legislation that functioned as USACE omnibus authorization bills and identifies the titles relevant to USACE. The appendix next provides supplementary information to what was provided in "USACE Authorization Legislation: 1986 to Present Process" regarding the evolution of the bills and the contents of specific bills.

Overview Table

Table B-1 provides additional information on each of the bills that functioned as an omnibus USACE authorization bill often titled as a Water Resource Development Act (WRDA) since 1986. The table includes the following bills.

- WRDA 1986 (P.L. 99-662)

- WRDA 1988 (P.L. 100-676)

- WRDA 1990 (P.L. 101-640)

- WRDA 1992 (P.L. 102-580)

- WRDA 1996 (P.L. 104-303)

- WRDA 1999 (P.L. 106-53)

- WRDA 2000 (P.L. 106-541)

- WRDA 2007 (P.L. 110-114)

- Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (WRRDA 2014; P.L. 113-121)

- Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act (WIIN; P.L. 114-322)

- America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 (AWIA 2018, P.L. 115-270)

The table lists the titles used in the bills and the agency or department related to the majority of the provisions in each of those titles. The titles are shown in the table as being primarily associated with either USACE civil works or primarily associated with programs and activities of agencies or departments other than USACE (with the relevant agency or department shown in parentheses). The placement in one of the two columns of the table is a broad sorting and does not reflect the details of each provision within a title. For titles listed as primarily USACE, a few provisions in a title may relate principally to other agencies or departments while the bulk of the title is USACE related, and vice versa for titles listed as not primarily associated with USACE. Titles related to revenue and trust funds that are closely associated with USACE projects and USACE appropriations are shown in the table as USACE titles. As appropriate, clarifying notes are provided in the final column.

As shown in Table B-1, USACE was the focus of the majority of titles for all of the bills except WIIN and AWIA 2018. For two of the bills—WRDA 1992 and WRRDA 2014—there were titles for which the majority of the provisions were related to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) while also being related to USACE activities. For example, Title V of WRRDA 2014 included authorizations that included both EPA and USACE, authorities only related to EPA, and an authority only related to USACE. WRDA 1992 had a title with provisions that related most closely to EPA's role in sediment management; USACE, however, has a role in sediment management more broadly as well as being mentioned in a few of the provisions of Title V of WRDA 1992. In contrast, WIIN included titles on water-related programs and projects spanning various agencies and departments other than USACE. Title I of the bill—which had a short title designated as WRDA 2016—focused specifically on USACE water resource authorizations, while Titles II, III, and IV focused primarily on other agencies; many of the specific provisions in these titles had no or little relationship to USACE.

|

Titles with Provisions Primarily Related to USACE |

Titles with Provisions Primarily Related to Agencies and Departments Other than USACE |

Notes |

|

America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 |

||

|

Title I. Water Resources Development |