Introduction

In recent years, Central American migrant families have been arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border in relatively large numbers, many seeking asylum.1 While some request asylum at U.S. ports of entry, others do so after attempting to enter the United States illegally between U.S. ports of entry.2 On May 7, 2018, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the Department of Justice (DOJ) implemented a "zero tolerance" policy toward illegal border crossing, both to discourage illegal migration into the United States and to reduce the burden of processing asylum claims that Administration officials contend are often fraudulent.3

Under the zero tolerance policy, DOJ prosecuted 100% of adult aliens4 apprehended crossing the border illegally, making no exceptions for whether they were asylum seekers or accompanied by minor children. Illegal border crossing is a misdemeanor5 for a first time offender and a felony6 for anyone who has previously been "denied admission, excluded, deported, or removed, or has departed the United States while an order of exclusion, deportation or removal is outstanding and thereafter enters, attempts to enter or is found in the U.S."7 Both such criminal offenses can be prosecuted by DOJ in federal criminal courts.

DOJ's "100% prosecution"8 policy represented a change in the level of enforcement of an existing statute rather than a change in statute or regulation.9 The recent Bush and Obama Administrations prosecuted illegal border crossings relatively infrequently, in part to avoid having DOJ resources committed to prosecuting sizeable numbers of misdemeanors. At different times during those Administrations, illegal entrants would be criminally prosecuted in an attempt to reduce illegal migration, but exceptions were generally made for families and asylum seekers.

Illegal border crossers who are prosecuted by DOJ are detained in federal criminal facilities. Because children are not permitted in criminal detention facilities with adults, detaining adults who crossed illegally requires that any minor children under age 18 accompanying them be treated as unaccompanied alien children (UAC)10 and transferred to the care and custody of the Department of Health and Human Services' (HHS's) Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR).

The widely publicized family separations were therefore a consequence of the Administration's policy of 100% prosecution of illegal border crossing, and not the result of a direct policy or law mandating family separation. Since the policy was implemented, "under 3,000" children may have been separated from their parents, including at least 100 under age 5.11

The family separations have garnered extensive public attention. The Trump Administration and immigration enforcement advocates maintain that the zero tolerance policy was necessary to dis-incentivize migrants from coming to the United States and clogging immigration courts with fraudulent requests for asylum.12 Immigrant advocates contend that migrant families are fleeing legitimate threats of violence and that family separations resulting from the zero tolerance policy were cruel and violated fundamental human rights.13

This report briefly reviews the statutory authority for prosecuting persons who enter the United States illegally between U.S. ports of entry, and the policies and procedures for processing apprehended illegal border entrants and any accompanying children. It explains enforcement policies under past Administrations and then discusses the Trump Administration's zero tolerance policy on illegal border crossers and the attendant family separations. The report concludes by presenting varied policy perspectives on the zero tolerance policy and briefly reviews recent related congressional activity. An Appendix examines recent trends in the apprehension of family units at the U.S. Southwest border.

This report describes policies and circumstances that continue to change. Information presented in it is current as of the publication date but may become outdated quickly.

Enforcement and Asylum Policy for Illegal Border Crossers

Aliens who wish to enter the United States may request admission legally14 at a U.S. port of entry or may attempt to enter illegally by crossing the border surreptitiously between U.S. ports of entry. Aliens who wish to request asylum may do so at a U.S. port of entry before an officer with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Office of Field Operations or upon apprehension between U.S. ports of entry before an agent with CBP's U.S. Border Patrol. DHS has broad statutory authority both to detain aliens not legally admitted, including asylum seekers, and to remove aliens who are found to be either inadmissible at ports of entry or removable once in the United States. Aliens requesting asylum at the border are entitled to an interview assessing the credibility of their asylum claims.15

Illegal U.S. Entry

Aliens who enter the United States illegally between ports of entry face two types of penalties. They face civil penalties for illegal presence in the United States, and they face criminal penalties for having entered the country illegally. Both types of penalties are explained below.

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) establishes civil penalties for persons who are in the United States unlawfully (i.e., without legal status). These penalties apply to foreign nationals who entered the United States illegally as well as those who entered legally but subsequently violated the terms of their admission, typically by "overstaying" their visa duration. Foreign nationals who are apprehended for such civil immigration violations are generally subject to removal (deportation) and are placed in formal or streamlined removal proceedings (described below in "Removal")

The INA also establishes criminal penalties for (1) persons who enter or attempt to enter the United States illegally between ports of entry, (2) persons who elude examination or inspection by immigration officers, or (3) persons who attempt to enter or obtain entry to the United States through fraud or willful misrepresentation.16 In addition, the INA provides criminal penalties for persons who unlawfully reenter the United States after they were previously removed from the country.17 Foreign nationals apprehended for criminal immigration violations are subject to prosecution by DOJ in federal criminal courts. This report only addresses criminal penalties for illegal entry and reentry between ports of entry.

Foreign nationals who attempt to enter the United States without authorization often do so between U.S. ports of entry on the U.S. border. If apprehended, they are processed by CBP. They are typically housed briefly in CBP detention facilities before being transferred to the custody of another federal agency or returned to their home country through streamlined removal procedures (discussed below). All apprehended aliens, including children, are placed into removal proceedings that occur procedurally after any criminal prosecution for illegal entry. Removal proceedings generally involve formal hearings in an immigration court before an immigration judge, or expedited removal without such hearings (see "Removal" below).

In general, CBP refers apprehended aliens for criminal prosecution if they meet criminal enforcement priorities (e.g., child trafficking, prior felony convictions, multiple illegal entries). Such individuals are placed in the custody of the U.S. Marshals Service (DOJ's enforcement arm) and transported to DOJ criminal detention facilities for pretrial detention. After individuals have been tried—and if convicted, have served any applicable criminal sentence—they are transferred to DHS Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody and placed in immigration detention.18 ICE, which represents the government in removal hearings, commences removal proceedings.

If CBP does not refer apprehended aliens to DOJ for criminal prosecution, CBP may either return them to their home countries using streamlined removal processes or transfer them to ICE custody for immigration detention while they are in formal removal proceedings.19

Asylum

Many aliens at the U.S.-Mexico border seek asylum in the United States. Asylum is not numerically limited and is granted on a case-by-case basis. Asylum can be requested by foreign nationals who have already entered the United States and are not in removal proceedings ("affirmative" asylum) or those who are in removal proceedings and claim asylum as a defense to being removed ("defensive" asylum). The process in each case is different.20

Arriving aliens who are inadmissible, either because they lack proper entry documents or because they attempt U.S. entry through misrepresentation or false claims to U.S. citizenship, are put into a streamlined removal process known as expedited removal (described below in "Removal").21 Aliens in expedited removal who express a fear of persecution are detained by ICE and given a "credible fear" interview with an asylum officer from DHS's U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).22 The purpose of the interview is to determine if the asylum claim has sufficient validity to merit an asylum hearing before an immigration judge. Those who receive a favorable credible fear determination are taken out of expedited removal, placed into formal removal proceedings, and given a hearing before an immigration judge, thereby placing the asylum seeker on the defensive path to asylum. Those who receive an unfavorable determination may request that an immigration judge review the case. Aliens in expedited removal who cannot demonstrate a credible fear are promptly deported.

Detention

The INA provides DHS with broad authority to detain adult aliens who are in removal proceedings.23 However, child detention operates under different policies than that of adults. All children are detained according to broad guidelines established through a court settlement agreement (applicable to all alien children) and two statutes (applicable only to unaccompanied alien children).

The 1997 Flores Settlement Agreement (FSA) established a nationwide policy for the detention, treatment, and release of all alien children, both accompanied and unaccompanied. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 charged ORR with providing temporary care and ensuring custodial placement of UAC with suitable and vetted sponsors.24 Finally, the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA) directed DHS to ensure that all UAC be screened by DHS for possible human trafficking.25 The TVPRA mandated that UAC from countries other than Mexico or Canada—along with all UAC apprehended in the U.S. interior—be transferred to the care and custody of ORR, and then be "promptly placed in the least restrictive setting that is in the best interest of the child."26 In the course of being referred to ORR, UAC are also put into formal removal proceedings, ensuring they can request asylum or other types of immigration relief before an immigration judge.

As a result of a 2015 judicial interpretation of the Flores Settlement Agreement, children accompanying apprehended adults cannot be held in family immigration detention with their parents for more than 20 days, on average. If the parents cannot be released with them, such children are typically treated as UAC and referred to ORR.

Removal

Under the formal removal process, an immigration judge from DOJ's Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) determines whether an alien is removable. The immigration judge may grant certain forms of relief (e.g., asylum, cancellation of removal), and removal decisions are subject to administrative and judicial review.

Under streamlined removal procedures, which include expedited removal and reinstatement of removal (i.e., when DHS reinstates a removal order for a previously removed alien), opportunities for relief and review are generally limited. Under expedited removal (INA §235(b)), an alien who lacks proper documentation or has committed fraud or willful misrepresentation to gain admission into the United States may be removed without any further hearings or review, unless he or she indicates a fear of persecution in their home country or an intention to apply for asylum.27

If apprehended foreign nationals are found to be removable, ICE and CBP share the responsibility for repatriating them.28 CBP handles removals at the border for unauthorized aliens from the contiguous countries of Mexico and Canada, and ICE handles all removals from the U.S. interior and removals for all unauthorized aliens from noncontiguous countries.29

Prosecution of Aliens Charged with Illegal Border Crossing in Prior Administrations

Prior to the Trump Administration, aliens apprehended between ports of entry who were not considered enforcement priorities (e.g., a public safety threat, repeat illegal border crosser, convicted felon, or suspected child trafficker) were typically not criminally prosecuted for illegal entry but would be placed directly into civil removal proceedings for unauthorized U.S. presence.30

In addition, aliens apprehended at and between ports of entry who sought asylum and were found to have credible fear generally were not held in immigration detention if DHS did not assess them as public safety risks. Rather, they were administratively placed into removal proceedings, instructed by DHS to appear at their immigration hearings, and then released into the U.S. interior. This policy became more prevalent after 2015 when a federal judge ruled that children could not be kept in immigration detention for more than 20 days.31

DHS officials justified the "catch and release" approach in the past because of the lack of detention bed space and the considerable cost of detaining large numbers of unauthorized aliens and family units for the lengthy periods, often stretching to years, between apprehension by CBP and removal hearings before an EOIR judge.32 Immigration enforcement advocates criticized the catch and release policy because of the failure of many apprehended individuals to appear subsequently for their immigration hearings.33

According to some observers, prior Administrations made more use of alternatives to detention that permitted DHS to monitor families who were released into the U.S. interior.34 Such practices are needed to monitor the roughly 2 million aliens in removal proceedings given that ICE's current budget funds less than 50,000 beds, which are prioritized for aliens who pose public safety or absconder risks.35

Data are not available on the rate and/or absolute number of family separations resulting from illegal border crossing prosecutions under prior Administrations, limiting the degree to which comparisons can be made with the Trump Administration's zero tolerance policy.36

DHS states that the agency referred an average of 21% of all illegal border crossing "amenable adults" for prosecution from FY2010 through FY2016.37 DHS maintains that it has an established policy of separating children from adults when it

- cannot determine the family relationship or otherwise verify identity,

- determines that the child is being smuggled or trafficked or is otherwise at risk with the parent or legal guardian, or

- determines that the parent or legal guardian may have engaged in criminal conduct and refers them for criminal prosecution.38

Prosecution of Aliens Charged with Illegal Border Crossing in the Trump Administration

On April 6, 2018, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced a "zero tolerance" policy under which all illegal border crossers apprehended between U.S. ports of entry would be criminally prosecuted for illegal entry or illegal reentry.39 This policy made no exceptions for asylum seekers and/or family units.40 To facilitate this policy, the Attorney General announced that he would send 35 additional prosecutors to U.S. Attorney's Offices along the Southwest border and 18 additional immigration judges to adjudicate cases in immigration courts near the Southwest border.41

Consequently, if a family unit was apprehended crossing illegally between ports of entry, the zero tolerance policy mandated that CBP refer all illegal adult entrants to DOJ for criminal prosecution. Accompanying children, who are not permitted to be housed in adult criminal detention settings with their parents, were to be processed as unaccompanied alien children in accordance with the TVPRA. They were transferred to the custody of ORR, which houses them in agency-supervised, state-licensed shelters. If feasible given the circumstances, ORR attempted to place them with relatives or legal guardian sponsors or place them in temporary foster care.42

ORR has over 100 shelters in 17 states,43 and during the implementation of the zero tolerance policy they were reportedly at close to full capacity.44 Consequently, at one point, the agency was evaluating options for housing children on Department of Defense (DOD) installations to handle the surge of separated children resulting from increased prosecution of parents crossing between ports of entry.45

As noted earlier, after adults have been tried in federal courts for illegal entry—and if convicted, have served their criminal sentences—they are transferred to ICE custody and placed in immigration detention. Typically, parents are then reunited in ICE family detention facilities with their children who have either remained in ORR custody or have been placed with a sponsor. Requests for asylum can also be pursued at this point.

Statistics and Timeline on Family Separation

In FY2017, CBP apprehended 75,622 alien family units and separated 1,065 (1.4%) of them. Of those separations, 46 were due to fraud and 1,019 were due to medical and/or security concerns. In the first five months of FY2018, prior to enactment of the zero tolerance policy, CBP apprehended 31,102 alien family units and separated 703 (2.2%), of which 191 resulted from fraud and 512 from medical and/or security concerns.46

Prior to Attorney General Sessions's announcement of the zero tolerance policy, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a lawsuit against ICE (referred to as "Ms. L. v. ICE") on behalf of two families separated at the Southwest border: a woman from the Democratic Republic of the Congo who was separated from her 6-year-old daughter at a port of entry for five months; and a woman from Brazil who had crossed into the United States illegally between ports of entry and was separated from her 14-year-old son for eight months.47 The lawsuit, filed in February, was subsequently expanded in March 2018 to a class-action lawsuit filed by the ACLU against ICE on behalf of all parents who were separated from their children by DHS.

In the early months of the policy, the Administration repeatedly revised the number of families that had been separated. According to CBP testimony in May 2018, 658 children were separated from 638 adults who were referred for prosecution between May 7 and May 21.48 DHS subsequently reported that 1,995 children had been separated from their parents between April 19 and May 31.49 DHS updated these figures in June 2018, reporting that 2,342 children were separated from their parents between May 5 and June 9.50 DHS then reported that CBP had since reunited with their parents 538 children who were never sent to ORR shelters.51 HHS Secretary Alex Azar then reported that "under 3,000" minor children (under age 18) had been separated from their families in total, including roughly 100 under age 5.52 As of July 13, 2018, HHS reported that 2,551 children ages 5 to 17 remained separated.53

On June 20, 2018, following considerable and largely negative public attention to family separations stemming from the zero tolerance policy, President Trump issued an executive order (EO) mandating that DHS maintain custody of alien families "during the pendency of any criminal improper entry or immigration proceedings involving their member," to the extent permitted by law and appropriations.54 The EO instructs DOD to provide and/or construct additional shelter facilities, upon request by ORR, and it instructs other executive branch agencies to assist with housing as appropriate to implement the EO.55 The EO mandates that the Attorney General prioritize the adjudication of detained family cases, and it requires the Attorney General to ask the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, which oversees the Flores Settlement Agreement, to modify the agreement to permit detained families to remain together.

On June 25, 2018, CBP announced that, because of ICE's lack of family detention bed space, it had temporarily halted the policy of referring adults who cross the border illegally with children to DOJ for criminal prosecution.56 According to a White House announcement, the zero tolerance policy may be reinstituted once additional family detention bed space becomes available.57 Also on June 25, 2018, DOD announced plans to permit four of its military bases to be used by other federal agencies to shelter up to 20,000 UAC and family units.58 DOD subsequently announced that 12,000 persons would be housed on its facilities,59 before another report appeared suggesting the number was 32,000 UAC and family units.60 Since these announcements, no efforts have been made to house apprehended UAC or family units on military installations.

On June 26, 2018, in response to the ACLU class action lawsuit, Judge Dana Sabraw of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California issued an injunction against the Administration's practice of separating families and ordered that all separated families be reunited within 30 days. The judge ruled that children under age 5 must be reunited with their parents within 14 days, all children must have phone contact with their parents within 10 days, children could be separated at the border only if accompanying adults presented an immediate danger to them, and parents were not to be removed unless they had been reunited with their separated children.61

In response to the June 26 injunction, the Trump Administration reportedly instructed DHS to provide all parents with final orders of removal and whose children were separated from them with two options.62 The first was to return to their countries of origin with their children. This option fulfilled the mandate from the June 26 court order to reunite families but also forced parents and children to abandon any claims for asylum. The second option was for parents to return alone to their country of origin. This option would leave the children in the United States to apply for asylum on their own. Parental decisions were to be recorded on a new ICE form.63

On July 9, 2018, Judge Dolly Gee of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, which oversees the Flores Settlement Agreement, ruled against a DOJ request to modify the agreement to permit children to remain with their parents in family detention. Judge Gee held that no basis existed for amending the court's original decision requiring the federal government to release alien minors in immigration detention after 20 days, regardless of any unlawful entry prosecution of the parents.64

On July 10, ICE officials reportedly indicated that parents reunited with their children would be enrolled in an alternative detention program, such as the use of ankle bracelets that permit electronic monitoring, and then released into the U.S. interior, essentially reverting to the prior policy that has been labeled by some as "catch and release."65 DOJ continued to maintain that its zero tolerance policy was in effect.66

On July 11, 2018, in response to the requirements of the ACLU lawsuit, ORR certified a list of 2,654 children that the agency stated were in its custody at the time of the June 26 injunction that it believed had been separated from their parents and whose parents met the lawsuit's class definition.67 According to a subsequent HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) report, one or more data sources showed that an additional 946 children may have been separated from family members at the time of apprehension, but their family members did not meet the criteria needed for inclusion in the lawsuit.68

On July 16, 2018, in response to concerns expressed by the ACLU about potential abrupt deportations following family reunification, Judge Sabraw temporarily halted, for one week, the deportations of parents who had been reunited with their children.69 The judge issued the stay of deportations to provide parents slated for removal with a week's time to better understand their legal rights regarding asylum or other forms of immigration relief for themselves and their children.

On July 16, 2018, Jonathan White, Deputy Director for Children's Programs at the Office of Refugee Resettlement, testified before Judge Sabraw that ORR had identified 2,551 separated children in its custody ages 5 to 17 and had matched 2,480 to their parents, while 71 children's parents remained unidentified.70 ORR was undertaking intensive background checks to ensure that separated children were reunited with their actual parents and did not face personal security risks such as child abuse.71 According to White, 1,609 parents of separated children remained in ICE custody. White noted that ICE was also conducting its own security checks and at that point had cleared 918 parents, failed 51 parents, and had 348 parents with pending clearances. As of July 16, 2018, ICE had approved about 300 children for release to be reunited with their parents.72

On July 18, 2018, HHS submitted a "Tri-Department Plan" in coordination with DHS and DOJ explaining actions the agencies were taking to reunify Ms. L v. ICE class members with their children. These steps include conducting and reviewing background checks of parents, confirming parentage, assessing child safety, interviewing parents, and reuniting families.73

As of July 19, 2018, the Administration had reportedly reunified 364 of the 2,551 children ages 5 to 17. Apart from the parents of those children, 1,607 parents were eligible to be reunited with their children, 719 of whom had final orders of deportation. Another 908 parents were not expected to be eligible for reunification because they possessed criminal backgrounds or required "further evaluation."74

On September 6, 2018, DHS and HHS proposed new regulations that would effectively terminate the Flores Settlement Agreement and replace it with formal regulations governing the "apprehension, processing, care, custody, and release" of minor children.75 The primary provision in these proposed regulations would be the authority to hold migrant children and their parents until their cases have been adjudicated. Whether federal courts will impose injunctions on or rule against the regulations based on their inconsistency with the Flores Settlement Agreement is not yet known.

In October 2018, it was widely reported that the Administration was considering alternative immigration enforcement policies involving family separation to reduce the persistent and relatively high level of unauthorized migrants seeking asylum at the Southwest border. One of these approaches, a "binary choice" policy, would give detained parents the option of keeping their children with them in immigration detention during the pendency of their immigration cases or being separated from their children, who would be referred to ORR shelters, including possible foster care.76 This option gained traction as a large and expanding migrant group originating from Honduras, referred to as the migrant "caravan," garnered extensive media attention as it made its way through Central America and Mexico. As of this writing, DHS has not taken any action with regard to this proposed policy.

Apart from the number of separated children who have been included in the Ms. L. v. ICE lawsuit, other figures emerged on the total number of family separations that have occurred more generally. For example, on October 12, 2018, Amnesty International (AI) published a report citing statistics provided to the organization by CBP indicating that 6,022 "family units" had been separated between April 19, 2018, and August 15, 2018.77 These cases, combined with the 1,768 family separations reported by DHS between October 1, 2016, and February 28, 2018 (the 1,065 in FY2017 plus the 703 in the first five months of FY2018 noted separately above) indicate that CBP has reported a total of 7,790 family separations to either CRS or AI. This total excludes an unknown number of family separations occurring between March 1 and April 18, 2018. According to AI, it also may exclude an unknown number of families that were separated after requesting asylum at U.S. ports of entry.

In January 2019, HHS's OIG issued a report on ORR's challenges identifying all separated children, ultimately concluding that "the total number of children separated from a parent or guardian by immigration authorities is unknown."78 The report cited limitations with both its information technology system for tracking such children as well as the complexity of determining which children should be classified as separated. According to this report, ORR's review of new information acquired between July and December 2018 indicated that an additional 162 children had met the criteria to be included in the Ms. L. v. ICE lawsuit, and that 79 previously included children had not actually been separated from a parent, changing the total from 2,654 to 2,737 children in the lawsuit.79

On February 7, 2019, a representative from HHS's OIG testified before Congress that DHS was continuing to separate children from their parents, although at a lower rate than during the zero tolerance policy of May-June 2018. The testimony noted that while DHS routinely separates families if parents have a criminal history, DHS had not provided HHS with sufficient information to facilitate appropriate placement within the ORR shelter system.80 The testimony also noted that "thousands more" children were likely separated prior to June 26, 2018, but, lacking any formal system for tracking such separations, the witness could not provide more precise figures.

On February 21, 2019, the Joint Status Report filed on the status of a revised total of 2,816 children (2,709 ages 5 and above and 107 under age 5)81 included in the Ms. L. v. ICE lawsuit indicated that 2,735 had been reunited with their parents.82 The statuses of the remaining children are described in the report largely as follows: being determined upon further review to have not been separated from their parents; not reunited because of potential safety issues with the parent; and not being reunited because deported parents confirmed they wanted to allow the child to remain in the United States.83 In addition, the report also indicated that up to 249 additional children not part of the Ms. L. v. ICE lawsuit had been separated between June 27, 2018 (the day after the lawsuit was filed), and January 31, 2019. According to ICE, the basis for separation was largely "parent criminality, prosecution, gang affiliation, or other law enforcement purpose."

On February 21, 2019, Texas Civil Rights Project released a report describing the findings from interviews with 272 adults who had experienced family separation subsequent to the President's executive order. The interviewees, a subset of almost 10,000 screened immigrants who were prosecuted for immigration violations at the Southwest border, had indicated to screeners that they had been separated from their children.84 The data, the first on family separation collected on a large scale by an organization outside the federal government, indicated that since the zero tolerance policy was terminated, a considerable number of family separations had occurred between minor children and relatives other than parents and legal guardians. As noted above, the INA defines an unaccompanied child as an unauthorized minor under age 18 who is not in the care and custody of a parent or legal guardian.85 According to DHS, minor children apprehended at the border who are accompanied by older siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and other relatives who are not parents or legal guardians must be treated as unaccompanied alien children, separated from their accompanying relatives, and turned over to the custody of ORR. DHS reportedly does not count such related pairs of individuals as family units in its statistics, raising concerns among advocates that current CBP statistics may not fully capture the extent of family separation among apprehended migrants.

Policy Perspectives

Perspectives on the zero tolerance policy generally divide into two groups. Those who support greater immigration enforcement point to recent surges in family unit migration and a substantial backlog of asylum cases that are straining DHS and DOJ resources, potentially compromising the agencies' abilities to meet their outlined missions. Those who advocate on behalf of immigrants decry the Administration's treatment of migrants as unnecessarily harsh and counterproductive.

Enforcement Perspectives

DHS and DOJ contend that the policy enforces existing law and is needed to reduce illegal immigration.86 DHS notes that foreign nationals attempting to enter the United States between ports of entry or "without inspection" are committing a crime punishable under the INA as a misdemeanor on the first occasion and a felony for every attempt thereafter.

DHS maintains that it has a long-standing policy of separating children from adults when children are at risk because of threats from human trafficking or because the familial relationship is suspect. DHS also maintains that it does not have a formal policy of separating parents from children for deterrence purposes, and it follows a standard policy of keeping families together "as long as operationally possible."87 According to DHS, the agency has "a legal obligation to protect the best interests of the child whether that is from human smugglings, drug traffickers, or nefarious actors who knowingly break [U.S.] immigration laws and put minor children at risk."88 Accordingly, DHS considers it appropriate to treat children of apprehended parents as UAC.89

DHS posits that while family separation is an unfortunate outcome of stricter enforcement of immigration laws and criminal prosecution of illegal entry and reentry, it is no different than the family separation that occurs in the U.S. criminal justice system when parents of minor children commit a crime and are taken into criminal custody.90 Attorney General Sessions has stated that parents who do not want to be separated from their children should simply not attempt to cross the U.S. border illegally.91

DHS Secretary Nielsen justified the zero tolerance policy with statistics showing a 223% increase in illegal border crossings and inadmissible cases along the Southwest border between April 2017 and April 2018.92 Similar increases in monthly apprehensions between years were cited for family units and unaccompanied alien children. Secretary Nielsen also stated that while the apprehension figures "are at times higher or lower than in years past, it makes little difference," characterizing them as unacceptable either way.93 DHS officials cite results of policies imposed at the Border Patrol's El Paso sector (covering West Texas and New Mexico) for part of 2017, where a similar family separation policy reduced the number of illegal family border crossings by 64%.94

DHS notes that its policy reflects President Trump's January 2017 Executive Order 1376795 on border security directing executive branch departments and agencies to "deploy all lawful means to secure the Nation's Southwest border, to prevent further illegal immigration into the United States, and to repatriate illegal aliens swiftly, consistently, and humanely."96 DHS further contends that parents who attempt to cross illegally into the United States with their children not only put their children at grave risk but also enrich transnational criminal organizations to whom they pay smuggling fees. DHS argues that some parents, aware of the limited amount of family detention space, intentionally use their children as shields from detention and anticipate that they will be viewed, as they had been in prior years, as low security risks.97 DHS points to unpublished intelligence reports describing cases where unrelated adults have used or trafficked children in order to avoid immigration detention.98 DHS and other observers also note that asylum requests have increased considerably, a trend that raises concerns about possible fraudulent asylum claims and the misuse of asylum claims to enter and remain in the United States.99

DHS notes that ICE and ORR both play a role in family reunification and characterizes the process as "well-coordinated."100 DHS maintains that it has procedures in place to connect separated family members and ensure that parents know the location of minors and can regularly communicate with them. Mechanisms to facilitate such communication include posted information notices in ICE detention facilities, an HHS Adult Hotline and email inquiry address, and an ICE call center and email inquiry address.101 DHS and ORR are using DNA testing to confirm familial ties between parents and children.102

Immigrant Advocacy Perspectives

Immigrant advocacy organizations argue that migrant families are fleeing a well-documented epidemic of gang violence from the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.103 They have criticized the practice of family separation because it seemingly punishes people for fleeing dangerous circumstances and seeking asylum in the United States. They posit that requesting asylum is not an illegal act,104 Congress created laws that require DHS to process and evaluate claims for humanitarian protection, DHS must honor congressional intent by humanely processing and evaluating such claims, and many who request asylum have valid claims and compelling circumstances that merit consideration.105

Immigrant advocates have also criticized the Administration for creating what they consider to be a debacle of its own making, characterized by frequently changing policies and justifications,106 what some describe as an uncoordinated implementation process, and the absence of an effective plan to reunify separated families.107 In some cases, records linking parents to children reportedly may have disappeared or been destroyed, hampering efforts to establish relationships between family members.108 Media reports have described obstacles to reuniting families after separation, including a lack of communication between federal agencies, the absence of information about accompanying children collected by CBP at the time of apprehension, the inability of ICE detainees to receive phone calls without special arrangements, and a cumbersome vetting process to ensure children's safe placement with parents.109 Similar observations have since been made by government agencies.110 In addition, while DOJ typically detains and prosecutes parents for illegal entry at federal detention centers and courthouses near the U.S.-Mexico border, ORR houses their children at shelters geographically dispersed in 17 states, in some cases thousands of miles away from the parents.

Child welfare professionals assert that family separation has the potential to cause lasting psychological harm for adults111 and especially for children.112 Some point to the findings of a DHS advisory panel as well as those of other organizations that discourage family detention as neither appropriate nor necessary for families and as not being in children's best interests.113

Some immigration observers question the Administration's ability to marshal resources required to prosecute all illegal border crossers given that Congress has not appropriated additional funding to support the zero tolerance policy. One news report, for example, noted that 3,769 foreign nationals were convicted of illegal entry in criminal courts during March 2018, a month in which 37,383 foreign nationals were apprehended for illegal entry.114 Given the relative size of the task they face, observers question how DOJ and DHS can channel fiscal resources to meet this objective without compromising their other missions. They contend that the policy is counterproductive because it prevents CBP from using risk-based strategies to pursue the most egregious crimes, thereby making the Southwest border region less safe and more prone to criminal activity.115 Some have suggested that the zero tolerance policy is diverting resources from, and thereby hindering, other DHS operations.116

Some in Congress have criticized the family separation policy because of its cost in light of alternative options, such as community-based detention programs. They cite, for example, the Family Case Management Program (FCMP), which monitored families seeking asylum and demonstrated reportedly high compliance rate with immigration requirements such as court hearings and immigration appointments.117 The FCMP, which began in January 2016,118 was terminated by the Trump Administration in April 2017.119 According to DHS, the FCMP average daily cost of $36 reportedly exceeded that of "intensive supervision" programs ($5-$7 daily),120 although both programs are considerably lower than the average daily cost of family detention ($319).121

More broadly, immigration advocates contend that the Administration is engaged in a concerted effort to restrict access to asylum and reduce the number of asylum claims.122 They caution that prosecuting persons who cross into the United States in order to present themselves before a CBP officer and request asylum raises concerns about whether the United States is abiding by human rights and refugee-related international protocols.123 They note a considerable current backlog of pending defensive asylum cases, which numbered almost 325,000 (45%) of the roughly 720,000 total pending immigration cases in EOIR's docket as of June 11, 2018.124 They also cite Attorney General Sessions's recent decision to substantially limit the extent to which immigration judges can consider gang or domestic violence as sufficient grounds for asylum.125 Such efforts could have the unintended effect of sustaining illegal immigration flows of desperate foreign nationals fleeing violent circumstances, particularly from Northern Triangle countries.

Congressional Activity

Given that this topic is developing rapidly, bills discussed below do not reflect all legislation or amendments introduced to date, or more recent developments. Instead, the bills presented here are intended to illustrate the range of legislative proposals to address family separation in the current context.

116th Congress

Bills introduced during the 116th Congress that are related to family separation are intended to prevent or limit the practice. These include H.R. 883/S. 271, the Families Belong Together Act, which would grant humanitarian parole and/or LPR status to separated parents and children upon request. Likewise, H.R. 541/S. 292, the Keep Families Together Act (similar to H.R. 6135/S. 3036 introduced in the 115th Congress) contains provisions to keep families together during all stages of processing following apprehension at a U.S. border, plus protections against the prosecution for illegal border crossing of asylum seekers and grantees. H.R. 1012, the REUNITE Act, includes provisions that would facilitate the expeditious reunification of separated families.

H.J.Res. 31, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019, included additional funding to increase the number of participants in Alternatives to Detention (ATD) programs; additional ICE staffing dedicated to the management of ATD immigration cases, particularly those of asylum applicants; and the Family Case Management Program (FCMP), an alternative to family detention. The legislation directs ICE to prioritize both the use of ATD programs for families and the adjudication timeline for cases of individuals enrolled in ATD, particularly those of families and asylum seekers.

115th Congress

A number of bills were introduced in the 115th Congress in response to family separation resulting from the Administration's zero tolerance policy regarding the prosecution of illegal border crossing. With the exception of H.R. 6136, which failed to pass in the House by a vote of 121-301, none of the bills introduced saw congressional action.

Bills that emphasized immigration enforcement included H.R. 6182, the Codifying President Trump's Affording Congress an Opportunity to Address Family Separation Executive Order Act, which would have provided statutory authority for President Trump's executive order within the INA; H.R. 6173, which would have clarified standards for family detention; and Section 3102 of H.R. 6136, the Border Security and Immigration Reform Act of 2018, which would have permitted children accompanied by parents to remain in DHS custody during the pendency of a parent's criminal prosecution, rather than being referred to ORR and treated as UAC. On July 11, 2018, similar amendment language was included in an appropriations bill to fund the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, that was approved by the House Appropriations Committee. H.R. 6204, the Families First Act of 2018, included similar provisions, asylum reforms, and provided increased funding for family unit facilities, personnel, and judges, among other provisions.

Bills that intended to prevent or limit family separation included H.R. 6135/S. 3036, the Keep Families Together Act, and H.R. 6236, the Family Unity Rights and Protection Act, both of which contained provisions to keep families together during all stages of processing following apprehension at a U.S. border; H.R. 6232, the Preventing Family Separation for Immigrants with Disabilities Act, which would have prohibited family separation for individuals with developmental disabilities; and H.R. 6172, the Reunite Children with Their Parents Act, which would have required DHS and DOJ to reunite minor children already separated from their parents.

Other bills, such as H.R. 6181/H.R. 6190/S. 3093, the Keep Families Together and Enforce the Law Act, would have maintained family unity by making the Flores Settlement Agreement and related laws and regulations inapplicable to children who are accompanied by adults when they are apprehended at a U.S. border. H.R. 6195/S. 3091, the Protect Kids and Parents Act, would have limited the separation of families seeking asylum by mandating that they be housed together, and facilitated asylum processing (e.g., by adding additional immigration judges and DHS personnel and establishing asylum processing deadlines), among other provisions.

Appendix. Trends in Alien Apprehensions

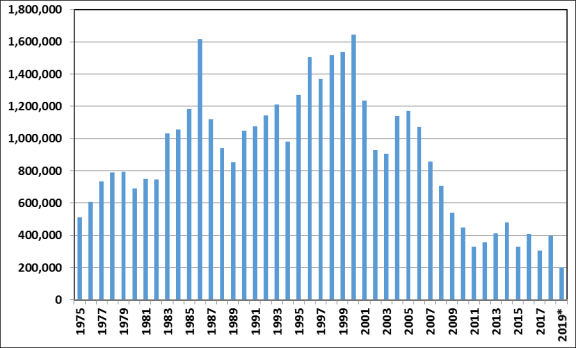

Increasing numbers of apprehensions of Central American families and children are occurring within the context of relatively low historical levels of total alien apprehensions (Figure A-1).

|

Figure A-1. Total Alien Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, FY1975-FY2019* |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, United States Border Patrol, "Stats and Summaries," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/media-resources/stats. Notes: *FY2019 includes October 2018 through January 2019, or one-third of the fiscal year. |

Apprehensions at the Southwest border had peaked at 1.62 million in 1986, the year Congress enacted the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), which gave legal status to roughly 2.7 million unauthorized aliens residing in the United States.126 After dropping for multiple years, apprehensions increased again, climbing from 0.85 million in FY1989 to an all-time high of 1.64 million in FY2000. Apprehensions generally fell after that (with the exception of FY2004-FY2006), reaching a 40-year low of 327,577 in FY2011. They have fluctuated since that point, declining even further in some years. For the first four months of FY2019, apprehensions at the Southwest border reached 201,497.127

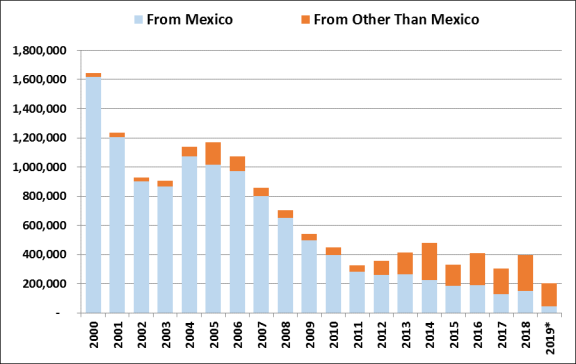

The national origins of apprehended aliens have shifted considerably during the past two decades (Figure A-2). In FY2000, for example, almost all aliens apprehended at the Southwest border (98%) were Mexican nationals. As recently as FY2011, Mexican nationals made up 84% of all apprehensions. However, beginning in FY2012, foreign nationals from countries other than Mexico made up a growing percentage of total apprehensions and for most years after FY2013, they made up the majority. In the first four months of FY2019, "other-than-Mexicans" comprised most (78%) of total alien apprehensions on the Southwest border.

|

Figure A-2. Total Alien Apprehensions at the Southwest Border by Country of Origin, FY2000-FY2019* (Country of origin is either Mexico or other-than-Mexico) |

|

|

Source: FY2000-FY2017: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, United States Border Patrol, "Stats and Summaries," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/media-resources/stats; FY2018-FY2019: CRS presentation of unpublished data received from CBP Leg Affairs. Notes: *FY2019 includes October 2018 through January 2019, or one-third of the fiscal year. |

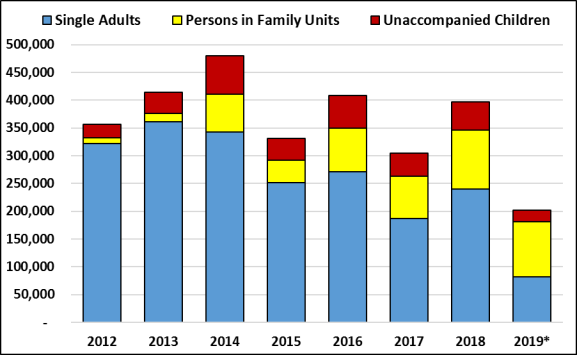

Among demographic categories, persons in family units and unaccompanied children currently make up the largest share of total alien apprehensions at the Southwest border (Figure A-3). According to CBP Commissioner Kevin McAleenan, single adult males made up over 90% of arriving aliens in the past.128 However, in the first four months of FY2019, family units and unaccompanied children comprised roughly 60% of all apprehended aliens.

CBP data on family unit apprehensions at the Southwest border are publicly available starting in FY2012, when they numbered just over 11,000. Since then, family unit apprehensions have increased considerably, reaching a peak of 107,212 in FY2018. In the first four months of FY2019, CBP apprehended 99,901 family units, which, if extrapolated to the remainder of FY2019, yields a projected estimate of almost 300,000 family unit apprehensions, exceeding the annual levels of all prior fiscal years.129 CBP data on apprehensions of unaccompanied alien children at the Southwest border from FY2012 onward indicate a peak of 68,541 apprehensions in FY2014 and 20,123 apprehensions in the first four months of FY2019.

|

Figure A-3. Total Alien Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, by Demographic Classification, FY2012-FY2019* |

|

|

Source: For FY2008-FY2013: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, United States Border Patrol, "Juvenile and Adult Apprehensions—Fiscal Year 2013." For FY2014-FY2016, "Customs and Border Protection, Southwest Border Unaccompanied Alien Children." For FY2017-FY2019, "U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2017," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions. Notes: *FY2019 includes October 2018 through January 2019, or one-third of the fiscal year. Family unit apprehensions represent apprehended individuals in family units, not apprehended families. |

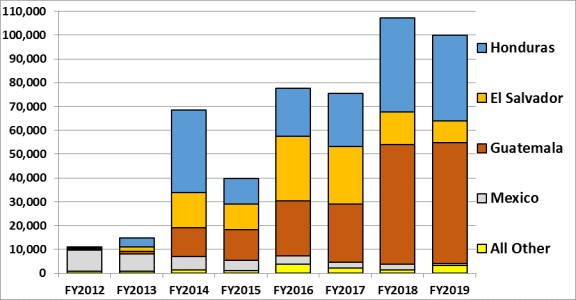

Since FY2012, the composition of family unit apprehensions by origin country has shifted from mostly Mexican (80%) to mostly El Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran (96%) (Figure A-4). Among these three Northern Triangle countries, the percentage of apprehensions from El Salvador, after increasing for several years, has recently declined, from 35% of all family unit apprehensions in FY2016 to 9% in the first four months of FY2019, while the percentage from Guatemala has increased steadily from 3% in FY2012 to 51% in FY2019.

Among unaccompanied alien children apprehended at the Southwest border, a similar country-of-origin compositional shift has also occurred. The percentage of apprehended unaccompanied children originating from Mexico declined from 57% in FY2012 to 15% in the first four months of FY2019, while the percentage of apprehended unaccompanied children from the Northern Triangle countries increased from 42% to 82% over the same period.130

|

Figure A-4. Total Alien Family Unit Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, FY2012-FY2019* |

|

|

Source: For FY2008-FY2013: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, United States Border Patrol, "Juvenile and Adult Apprehensions—Fiscal Year 2013." For FY2014-FY2016, "Customs and Border Protection, Southwest Border Unaccompanied Alien Children." For FY2017-FY2019, "U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2017," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions. Notes: *FY2019 includes October 2018 through January 2019, or one-third of the fiscal year. Family unit apprehensions represent apprehended individuals in family units, not apprehended families. |