Introduction

The United States has played a leading role in global efforts to alleviate hunger and improve food security. Current food assistance programs originated in 1954 with the passage of what is now named the Food for Peace Act (FFPA, P.L. 83-480).1 This legislation, commonly referred to as "P.L. 480," established the Food for Peace program (FFP). Originally, FFP had multiple aims: (1) to provide food to undernourished people abroad, (2) to reduce U.S. stocks of surplus grains that had accumulated under U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) commodity support programs, and (3) to expand potential markets for U.S. food commodities. Since the end of the Cold War, U.S. food assistance goals have shifted away from the latter two aims and more toward emergency response and supporting recipient country agriculture markets.

|

Food Assistance Terminology As the understanding of hunger and its causes has evolved over time, so have the terms used to discuss hunger and food assistance. In this report, terms are defined as follows: Food aid refers to in-kind food transfers, whether used directly or monetized. Food assistance refers to both in-kind food transfers and cash-based programs that provide the means to acquire food. Food security encompasses food assistance but includes agricultural and rural economic development projects, nutritional well-being projects, and other activities that enhance food access and nutrition at the household, village, and country levels. |

For example, in 2018 the United States provided food assistance to food-insecure people in Ethiopia. This food assistance targeted those affected by flooding in spring 2018 as well as refugees who had fled to Ethiopia from neighboring countries, such as South Sudan.2

For most of its existence, U.S. international food assistance provided exclusively in-kind aid—commodities sourced in the United States and shipped to recipient countries. In recent decades, U.S. food assistance programs have shifted from exclusively in-kind to a combination of in-kind and cash-based assistance, such as locally procured food, cash transfers, or vouchers. More recently, Feed the Future (FTF), a government-wide initiative that coordinates U.S. agriculture and food assistance, has increasingly aligned non-emergency food assistance with other food-security-related programs such as agricultural development and global health programs.

U.S. law requires federal international food assistance to be provided primarily through in-kind aid.3 Opinions among policymakers and interested parties differ over whether such requirements make food assistance programs less efficient or whether they have substantive benefits, such as lowering the risk of recipients using assistance for unintended purposes and preserving the coalition of nonprofit organizations, farmers, and shippers who support these programs.

This report provides an overview of U.S. international food assistance programs, including authorizing legislation, historical funding trends, and common program features and requirements. It also discusses issues for congressional consideration and recent legislative proposals. This report focuses on international food assistance programs that currently receive funding from Congress.4

International Food Assistance Programs5

Two main legislative tracks authorize international food assistance programs, each with different authorizing histories and congressional committees responsible for funding. First, the FFPA authorizes traditional food assistance programs based primarily on in-kind aid. These programs (explained later in this section) include FFP Title II, FFP Title V,6 the McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program, the Bill Emerson Humanitarian Trust, and Food for Progress. Congress has reauthorized the FFPA through periodic farm bills, most recently the 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79). These programs are under the jurisdiction of the House and Senate Agriculture Committees. Second, Congress permanently authorized the Emergency Food Security Program (EFSP) as part of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (FAA, P.L. 87-195) in the Global Food Security Act of 2016 (GFSA, P.L. 114-195). EFSP is under the jurisdiction of the House Foreign Affairs and Senate Foreign Relations Committees. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) implement international food assistance programs. USDA procures commodities for all food assistance programs, regardless of which agency implements the program. Table 1 lists each active food assistance program along with its primary delivery method, statutory authority, source of funding, and implementing agency.

|

Program |

Delivery Method |

Statutory Authority |

Funding Source |

Agency |

|

Food for Peace Title II |

In-kind |

FFPA |

Agriculture appropriations bills |

USAID |

|

Farmer-to-Farmer (Food for Peace Title V) |

Technical assistancea |

FFPA |

Agriculture appropriations bills |

USAID |

|

McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition |

In-kind |

FFPA |

Agriculture appropriations bills |

USDA |

|

Bill Emerson Humanitarian Trust |

In-kind |

FFPA |

Mandatory appropriationsb |

USDA |

|

Food for Progress |

In-kind |

FFPA |

Mandatory appropriationsb |

USDA |

|

Emergency Food Security Program |

Cash-based |

FAA |

SFOPS appropriations bills |

USAID |

Source: Compiled by CRS. FFPA = Food for Peace Act of 1954, as amended; FAA = Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended; SFOPS = State and Foreign Operations.

Notes:

a. The Farmer-to-Farmer program does not provide in-kind or cash-based assistance but is included here because it is part of the suite of programs the FFPA authorizes, and its annual funding is tied to total funding for Food for Peace programs.

b. The authorizing legislation established mandatory funding, financed through the USDA Commodity Credit Corporation's borrowing authority.

Other key participants in delivering international food assistance are:

- Nongovernmental or intergovernmental organizations (NGOs or IOs): An NGO is a private organization that provides services or advocates on public policy issues, such as an organization that works to solve development problems at the local level. An IO is a multilateral institution such as the U.N. World Food Program. NGOs and IOs implement food assistance projects in countries of need, with oversight and program funding from USAID or USDA.

- The Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC): The CCC is a government-owned financial institution, overseen by USDA, which procures commodities, processes financial transactions, and finances domestic and international programs to support U.S. agriculture.7

The U.S. government provides food assistance through two distinct methods:

- 1. In-kind contributions are commodities produced in the United States and shipped to the target region. Some shelf-stable (i.e., not easily spoiled) U.S. commodities can be prepositioned in storage facilities in the United States and abroad to enable quicker response to emergencies.

- Monetization is a form of in-kind aid in which the entity sells U.S. commodities on local markets in developing countries and uses the proceeds to fund development projects.8

- 2. Cash-based assistance provides direct cash transfers or food vouchers to beneficiaries. Under local and regional procurement (LRP), NGOs or IOs purchase food in the country or region where it is to be distributed to beneficiaries rather than in the United States.

The Obama Administration created Feed the Future (FTF) in 2010. FTF is a government-wide initiative that aims to improve U.S. international food security efforts by uniting all food-security related programs under common goals and evaluation criteria. Because FTF focuses on long-term food security, it does not coordinate emergency food assistance activities. However, non-emergency food assistance activities—such as McGovern-Dole, Food for Progress, Farmer-to-Farmer, and non-emergency assistance provided under FFP Title II—are part of FTF. Under FTF, non-emergency food assistance programs coordinate activities with other food security efforts, such as global health and agricultural development programs. Non-emergency food assistance programs also submit data to collaborative FTF evaluations.9

Food for Peace Title II

Under FFP Title II, the federal government donates U.S.-sourced commodities to a qualifying IO or NGO to be distributed directly to beneficiaries or monetized to fund development projects.10 Congress provides funding for Title II annually through agriculture appropriations bills. The majority of Title II funds are used for emergency assistance, such as responding to conflicts or natural disasters. In FY2017, 76% of Title II funds supported emergency assistance, and the remaining 24% supported non-emergency assistance.11

USAID administers FFP Title II. NGOs and IOs apply to USAID to implement a project under FFP Title II. Once USAID approves a Title II project, the implementing organization requests commodities. USDA procures U.S.-produced commodities on the open market. The implementing organization works with USAID to arrange shipment of commodities by ocean freight in accordance with agricultural cargo preference laws discussed in the "Common Features and Requirements" section.12

Farmer-to-Farmer (Food for Peace Title V)

Congress established the John Ogonowski and Doug Bereuter Farmer-to-Farmer program13 in the 1966 FFPA reauthorization (P.L. 89-808). Congress first funded the program in 1985, when it established minimum required funding in the 1985 farm bill (P.L. 99-198). This minimum funding was 0.1% of the annual funds appropriated for Food for Peace programs. The Farmer-to-Farmer program's funding is discretionary and tied to annual total funding for Food for Peace programs. Congress has periodically updated minimum required funding levels in the farm bill. The 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79) authorized minimum funding of the greater of $15 million or 0.6% of the funds appropriated for Food for Peace programs. From FY2014 to FY2017, Congress provided $15 million per year in funding for the program.

USAID administers the Farmer-to-Farmer program, which finances short-term (typically two- to four-week) volunteer placements in developing countries to provide technical assistance to farmers. Volunteers are U.S. citizens drawn from farming, agribusiness, universities, and nonprofit organizations. USAID selects eligible NGOs to coordinate volunteer placements. Potential volunteers apply directly to the coordinating NGOs and are selected based on the needs of the individual or organization in the developing country. The Farmer-to-Farmer program does not provide in-kind or cash-based food assistance. It is included in this discussion because it is part of the suite of programs the FFPA authorizes and receives funding through appropriations for Food for Peace programs.

McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition

Congress established the McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program in the 2002 farm bill (P.L. 107-171). USDA administers the McGovern-Dole program, and Congress funds the program through annual agriculture appropriations bills. The McGovern-Dole program aims to advance food security, nutrition, and education for children—especially girls—by providing school meals. The program also focuses on improving children's health before they enter school by providing food to pregnant and nursing mothers, infants, and children under school age. In addition to providing food, the program encourages governments in recipient countries to establish national school feeding programs and provides technical assistance to help them do so.

USDA chooses priority countries for McGovern-Dole projects each year based on criteria including per-capita income, literacy, and malnutrition rates. The program primarily uses in-kind aid, but in recent years it was authorized to use LRP.14 In FY2016 and FY2017, Congress authorized that up to $5 million of the funds appropriated to the McGovern-Dole program may be used for LRP activities within existing McGovern-Dole projects. In FY2018, Congress authorized that up to $10 million of the funds appropriated to the McGovern-Dole program may be used for LRP activities.

Bill Emerson Humanitarian Trust

Congress first authorized the Bill Emerson Humanitarian Trust (BEHT) in its current form in the Africa: Seeds of Hope Act of 1998 (P.L. 105-385).15 USDA administers the BEHT. It is a reserve of U.S. commodities or funds held by the CCC. These commodities or funds can supplement FFP Title II, especially when FFP Title II funds alone cannot meet emergency food needs in developing countries. Congress reimburses the CCC for the value of any commodities released from the BEHT through either FFPA appropriations or direct appropriations to the CCC. The CCC may either use these reimbursement funds to replenish the released commodities or hold the funds for BEHT against future need to purchase U.S. commodities for emergency assistance. In 2008 USDA sold the BEHT's remaining commodities—about 915,000 metric tons (mt) of wheat—and currently the BEHT holds only funds. BEHT funds were used in FY2014 to purchase 189,970 mt of U.S. agricultural commodities to supply FFP Title II projects in South Sudan.16

Food for Progress

Under the Food for Progress program, USDA donates U.S. agricultural commodities to partner IOs, NGOs, foreign governments, or private entities, which then monetize the commodities by selling them locally to raise funds for development projects. Food for Progress projects focus on improving agricultural productivity through agricultural, economic, or infrastructure development. Recipient country governments must make commitments to introduce or expand free enterprise elements in their agricultural economies. In FY2017, USDA funded seven Food for Progress projects in nine different countries.17

Congress first authorized the Food for Progress program in the 1985 farm bill (P.L. 99-198). It may receive funding through either Food for Peace Title I appropriations or CCC financing. Congress has not appropriated Title I program funds since FY2006. Food for Progress now relies entirely on CCC financing. Statute requires that the program provide a minimum of 400,000 mt of commodities each fiscal year.18 However, this minimum has not been met in recent years, with actual totals averaging 255,418 mt per year between FY2007 and FY2016 and ranging from as little as 160,120 mt in FY2013 to as much as 341,820 mt in FY2015.19 Statute limits the program to pay no more than $40 million annually for freight costs,20 which limits the amount of shipped commodities, particularly in years with high shipping costs.

Emergency Food Security Program

Unlike FFP Title II, EFSP is a cash-based program. It can complement Title II when significant barriers exist to providing in-kind aid—for example, when in-kind food would not arrive soon enough or could potentially disrupt local markets or when it is unsafe to operate in zones of civil conflict. For example, from FY2013 to FY2015, more than half of EFSP outlays were used to respond to the conflict in Syria.21 This includes assistance provided to internally displaced persons and refugees who fled to neighboring countries such as Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey.

USAID administers EFSP. USAID first employed EFSP in FY2010 based on authority in the FAA to provide disaster assistance. In 2016, Congress permanently authorized EFSP in the GFSA. Congress funds EFSP through the International Disaster Assistance (IDA) account within State and Foreign Operations appropriations bills.

Food Assistance Funding

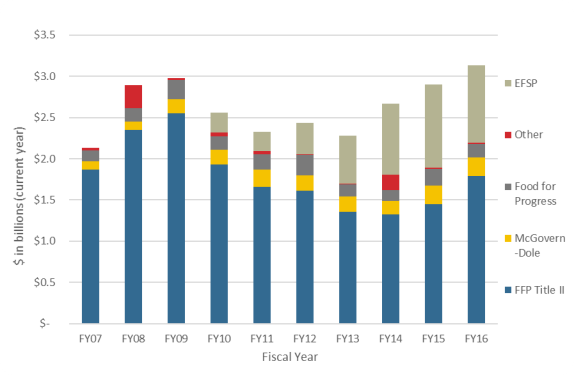

U.S. international food assistance outlays for these and other related programs have fluctuated over the past 10 years, rising in FY2008 and FY2009 partly in response to the global food price crisis of 2007-200822 and subsequently declining in the years following FY2009 (Figure 1). Outlays increased again between FY2013 and FY2016 partly in response to conflicts in Syria and Yemen and the Ebola epidemic in West Africa. While FFP Title II has comprised the bulk of food assistance outlays since the mid-1980s, cash-based EFSP assistance has grown from approximately 10% of total international food assistance in FY2010 to 30% in FY2016. During that same period, the share of Title II food assistance outlays decreased from 75% to 57%.

Common Features and Requirements

U.S. international food assistance programs share a number of common features and requirements, including agricultural cargo preference restrictions, commodity sourcing requirements, and labeling of commodity donations. Statutory requirements also mandate analyses to ensure that adequate storage facilities are available in recipient countries, assistance does not disrupt local markets in recipient countries, and assistance does not compete with U.S. agricultural exports. FFP Title II assistance also has specific requirements in addition to the requirements that apply to all international food assistance programs. These features and requirements are detailed below.

Agricultural Cargo Preference

In accordance with the Cargo Preference Act of 1954 (P.L. 83-644) and Section 901 of the Merchant Marine Act of 1936 (P.L. 74-835), both as amended, at least 50% of the gross tonnage of U.S. agricultural commodities provided under U.S. food aid programs must ship via U.S.-flag commercial vessels.23 This requirement is known as "agricultural cargo preference" (ACP). ACP is part of broader cargo preference requirements that apply to other government cargo, such as Department of Defense cargo. According to the Department of Transportation's Maritime Administration (MARAD), the main purpose of cargo preference laws is to sustain a privately owned, U.S.-flag merchant marine to provide sealift capability in wartime and national emergencies and to protect U.S. ocean commerce from foreign control.24 Under ACP, qualifying U.S.-flag ships must be privately owned and employ a crew consisting of at least 75% U.S. citizens. ACP applies to all in-kind aid provided under international food aid programs. It does not apply to LRP or other cash-based assistance.

U.S. Sourcing of Commodities

Statute requires all agricultural commodities distributed under food assistance programs authorized in the FFPA to be produced in the United States.25 However, there are some exceptions to this requirement. The requirement does not apply to food assistance provided under the LRP program authorized in the FFPA.26 It also does not apply to EFSP or other food assistance provided through authority in the FAA. Lastly, FFPA Section 202(e) allows a portion of FFP Title II funds to be used for storage, transportation, and administrative costs. The 2014 farm bill expanded eligible uses of these funds—referred to as 202(e) funds—to include "enhancing" FFP Title II projects, including through the use of cash-based assistance. Since 2014, 202(e) funds can be used to fund cash-based assistance that enhances existing FFP Title II in-kind assistance.27

Publicity and Labeling of Commodities

The FFPA requires foreign governments, NGOs, or IOs receiving U.S. commodities to widely publicize, to the extent possible, "that such commodities are being provided through the friendship of the American people as food for peace."28 In particular, governments and organizations must label FFP Title II commodities, "in the language of the locality in which such commodities are distributed, as being furnished by the people of the United States of America."29

Bellmon Analysis

Through the International Development and Food Assistance Act of 1977 (P.L. 95-88), Congress amended the FFPA to prohibit use of U.S. commodities for international food assistance if (1) the recipient country lacks adequate storage facilities to prevent spoilage or waste of commodities or (2) distribution of U.S. commodities in the recipient country would result in substantial disincentive to, or interference with, domestic production or marketing of agricultural commodities in that country. Cooperating organizations providing international food assistance must now conduct a "Bellmon analysis"—named for Senator Henry Bellmon, who sponsored the amendment to the FFPA. The analysis assesses whether the recipient country has adequate storage facilities and whether assistance would interfere with the recipient country's agricultural economy.30

Bumpers Amendment

An amendment to the Urgent Supplemental Appropriations Act, 1986 (P.L. 99-349, §209), offered by Senator Dale Bumpers, prohibited the use of U.S. foreign assistance funds for any activities that would encourage the export of agricultural commodities from developing countries that might compete with U.S. agricultural products on international markets.31 Exceptions to the Bumpers amendment include food-security-related activities, research activities that directly benefit U.S. producers, and activities in a country that the President determines is recovering from a widespread conflict, humanitarian crisis, or complex emergency.

Food for Peace Title II Requirements

In addition to the requirements listed above, FFP Title II assistance has specific requirements identified in Table 2.

|

Requirement |

U.S. Code Section |

Detail |

|

Minimum Tonnage (Total and Non-Emergency) |

7 U.S.C §1724(a) |

Title II must distribute a minimum of 2.5 million mt of commodities each year, of which 1.875 million mt (75%) must be distributed as non-emergency (development) assistance.a |

|

Minimum Allocation for Non-Emergency Aid |

7 U.S.C §1736f(e) |

Not less than 20% nor more than 30% of Title II funds shall be used for non-emergency assistance, with a minimum of at least $350 million programmed for non-emergency assistance each fiscal year. |

|

Value-Added Requirement |

7 U.S.C §1724(b) |

At least 75% of Title II non-emergency aid must be in the form of processed, fortified, or bagged commodities. Not less than 50% of bagged commodities that are whole-grain commodities must be bagged in the United States.b |

|

Monetization Requirement |

7 U.S.C §1723(b) |

Not less than 15% of all Title II non-emergency commodities must be monetized (sold on local markets to generate proceeds for development projects). Proceeds can be used to fund development projects or transportation, storage, and distribution of Title II commodities. |

Source: Compiled by CRS

Notes:

a. The USAID administrator has discretion to waive the minimum tonnage requirement in order to meet emergency needs or if such quantities cannot be used effectively as non-emergency assistance. The administrator has waived this requirement every year in recent decades. In FY2017, Title II assistance totaled 1.5 million mt of commodities, 279,400 mt of which were non-emergency assistance.

b. The USAID administrator may waive this requirement if he/she determines that the program goals will not be best met by enforcing it. In FY2017, 24.2% of non-emergency commodities were value-added, and 100% of whole-grain, bagged commodities were bagged in the United States.

Issues for Congress

In-Kind vs. Cash-Based Food Assistance

Historically, the United States provided international food aid exclusively via in-kind commodities. The United States remains one of the few major donor countries that relies primarily on in-kind aid. Many other donors—such as Canada, the European Union, and the United Kingdom—have switched to primarily cash-based assistance.32 U.S. use of cash-based assistance has increased in recent years under EFSP and to support the use of LRP in the McGovern-Dole program.

Proponents of in-kind aid emphasize that it supports American jobs. Providing U.S.-grown commodities supports the agricultural sector, and shipping those commodities on U.S.-flag ships supports the transportation sector. In-kind aid also supports American companies that produce ready-to-use therapeutic and supplementary foods, foods that are specially formulated to address malnutrition. Proponents also maintain that the visibility of in-kind food with U.S labels fosters good will between the United States and recipient countries.33

In-kind aid may be especially appropriate when local food availability is scarce. For example, in 2012 during a severe drought in the Sahel region of Africa, USAID provided in-kind aid to recipients during the "lean season" when markets were not well stocked. According to USAID, in-kind aid allowed local farmers to plant and tend to crops instead of having to migrate in search of food.34 Prepositioning food at warehouses in the United States and abroad allows aid to reach recipients sooner than traditional in-kind aid in emergency situations. In 2014, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that prepositioning shortened delivery time frames for in-kind aid by one to two months compared to standard delivery methods.35

Critics of in-kind aid emphasize that it takes longer to reach recipients than cash-based assistance. Although prepositioning in-kind aid shortens delivery times, GAO found that it can involve additional costs due to storage costs and additional shipping costs. Prepositioned commodities can also cost more than traditional in-kind commodities due to a limited supply of commodities available for domestic prepositioning.36

In 2011, GAO found that in-kind aid may not provide adequate nutrition to recipients during long-term emergencies. In some instances, lack of adequate nutrition led to micronutrient deficiencies. USAID and USDA can use specialized, nutrient-dense food products to supplement traditional commodities, but these products are costly and may be difficult to direct to intended recipients. GAO's analysis also found vulnerabilities in quality control of the food aid supply chain. In some instances, these vulnerabilities led to contamination of food aid commodities.37

Critics also contend that in-kind aid can be difficult to deliver in situations with geographic and security challenges. In multiple instances, food aid has reportedly been stolen from warehouses near conflict zones in South Sudan.38 In 2015, Dina Esposito, former director of USAID's Office of Food for Peace, testified that many Syrian refugees who had fled to neighboring countries to escape conflict were widely dispersed rather than congregated in refugee camps. According to Esposito, without the use of cash-based assistance, USAID "would not be able to feed people inside Syria and would have great difficulty feeding those displaced within the region, particularly where refugees are dispersed within host communities."39 Critics of in-kind aid also assert that in-kind commodities can disrupt local markets and cause price distortions.40

Cash-based assistance can take the form of direct cash transfers, food vouchers, or LRP. Proponents of cash-based assistance emphasize that it allows for quicker response times than shipping in-kind aid via ocean freight. This response time may be especially relevant to emergencies, when food needs are immediate. Research shows that LRP can arrive 14-16 weeks sooner than in-kind aid.41 Proponents also contend that cash-based assistance is less costly than in-kind aid, allowing donors to reach more people in need with less funding. The cost savings of cash-based assistance can vary widely based on target destination and current commodity prices. According to GAO, USDA and USAID recover 58%-76% of every dollar spent on monetizing in-kind aid. GAO also concluded that LRP costs 25% less, on average, than in-kind aid.42

Some research also found that cash-based assistance can better meet local dietary preferences and can support local agricultural markets and producers, both of which may be fragile in the wake of conflict or disaster.43 According to USAID, cash-based assistance is appropriate in situations in which people are physically spread out or highly mobile or when there are security concerns about transporting in-kind aid.44

Cash-based assistance may have policy or implementation challenges. Cost differences between LRP and in-kind aid can vary based on the specific commodity involved. For example, one study found that while LRP was less costly than in-kind aid when purchasing bulk cereals and beans, it was more expensive for processed foods such as vegetable oils or corn-soy blends.45 In addition, using LRP in food-deficit regions or underdeveloped markets could cause local or regional price spikes or provide insufficient access to food due to local unavailability. Lack of reliable suppliers and poor infrastructure can also limit the efficiency of LRP.46

Critics of cash-based assistance contend that in poorly controlled settings, cash transfers or food vouchers could be stolen or used to purchase nonfood items. In 2015, GAO found instances of fraud and theft in EFSP projects. GAO also determined that USAID risk assessments for EFSP projects did not fully address risks specific to cash-based food assistance.47 Additionally, in cases of particularly acute malnutrition, local foods may not offer adequate nutritional quality for therapeutic treatment and rehabilitation, especially for highly vulnerable populations such as children and pregnant or lactating women.48 Under these circumstances, providing fortified or specialized in-kind foods may be preferable. Critics of cash-based assistance also argue that it could undermine the coalition of commodity groups, NGOs, and shippers that advocate for food aid funding, potentially resulting in reductions in total U.S. food assistance funding.

Agricultural Cargo Preference

The Cargo Preference Act of 1954 (P.L. 83-164), as amended, mandates that at least 50% of U.S. food aid commodities must ship on U.S.-flag vessels. MARAD monitors and enforces ACP. Congress increased the share of food aid commodities required to ship on U.S.-flag vessels from 50% to 75% in the 1985 farm bill (P.L. 99-198) and subsequently lowered it to 50% in a 2012 surface transportation reauthorization act (P.L. 112-141).

According to MARAD, the main purpose of cargo preference laws is to sustain a privately owned, U.S.-flag merchant marine to provide sealift capability in wartime and national emergencies and to protect U.S. ocean commerce from foreign control.49 USA Maritime—an organization representing shipper and maritime unions—asserts that maintaining a U.S.-flag fleet and supply of U.S. mariners through cargo preference is a cost-effective alternative to the U.S. government building ships and hiring employees to maintain sealift capacity.50

MARAD contends that cargo preference is critical to the financial viability of U.S.-flag vessels and maintaining the supply of qualified U.S. mariners.51 According to a 2017 report by MARAD's Maritime Workforce Working Group, the current supply of qualified U.S. mariners is sufficient to crew the fleet of government and privately owned U.S.-flag ships necessary during an initial activation (for example, during wartime or a national emergency). However, there are not enough U.S. mariners to support a sustained activation of this fleet for a period longer than 180 days.52

Shipping on U.S.-flag vessels typically costs more than on foreign-flag vessels. A 2011 study by MARAD found that average daily operating costs for U.S.-flag vessels were 2.7 times higher than for foreign-flag vessels.53 USA Maritime maintains that a primary reason for the higher cost is that U.S.-flag ships have better working conditions and pay higher wages than foreign-flag ships.54 Ship owners surveyed by MARAD noted that "the standard of living in the U.S. and the social benefits provided to mariners contribute to U.S.-flag wages being significantly higher than foreign-flag wages."55

When shipping costs on U.S.-flag ships are higher than foreign-flag ships, ACP can increase food aid costs. This could potentially reduce the volume of food aid provided and, therefore, the number of people aided. According to GAO, "USAID officials stated that for each $40 million increase in shipping costs, its food aid reaches one million fewer recipients each year."56 USAID officials also noted that in some instances the agency has had to ship food aid on types of vessels that are not meant to carry bulk food cargo and are not compatible with equipment typically used to load and unload bulk grains. They asserted that this has resulted in increased costs and delays. USAID officials also expressed concerns about the appearance and health of bulk food transported on vessels that typically carry cargo such as oil or other fuels.57

Some opponents of ACP question its contributions to U.S. sealift capacity. They assert that few U.S.-flag ships depend on food aid shipments, and only some of those ships are capable of carrying military cargo. They also argue that ACP often benefits U.S. subsidiaries of foreign shipping companies rather than U.S. shipping companies.58 A 2010 study asserted that ACP increased food aid costs and contributed little to national security because 70% of ACP vessels did not meet the criteria that would deem them militarily useful.59

In 2015, GAO found that from April 2011 through July 2014, ACP increased the overall cost of shipping food aid by an average of 23%, or $107 million in total. GAO also concluded that ACP contributions to Department of Defense sealift capacity were uncertain, because in the preceding 13 years, including during conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the entire reserve sealift fleet was not activated. Additionally, MARAD had not fully assessed the potential availability of U.S. mariners needed for a full and prolonged activation.60 In 2018, GAO analyzed the assessment of U.S. mariner availability in the above-mentioned Maritime Workforce Working Group report. GAO found that although "the working group concluded that there is a shortage of mariners for sustained operations, its report also details data limitations that cause some uncertainty regarding the actual number of existing qualified mariners and, thus, the extent of this shortage."61

Administrative Proposals and Legislation

The Trump Administration and some Members of Congress proposed changes to the structure and intent of U.S. international food assistance programs during the 115th Congress. The Administration proposed changes through its FY2018 and FY2019 budget requests. Some Members of Congress proposed changes in the House and Senate 2018 farm bills (H.R. 2). Members also proposed changes in the Global Food Security Reauthorization Act of 2017 (P.L. 115-266), which became law in October 2018, and the Food for Peace Modernization Act (S. 2551/H.R. 5276). These administrative and legislative proposals are detailed below.

Administrative Proposals

FY2018 Budget Request

The Trump Administration's FY2018 budget request proposed a major reorganization of international food assistance funding. The request would have eliminated funding for the McGovern-Dole program and FFP Title II. Instead, it would have funded all international food assistance through the IDA subaccount within the state and foreign operations appropriations. The Trump Administration requested $2.5 billion for IDA, of which $1.1 billion would be allocated for emergency food assistance. Compared to FY2017 appropriated levels, the request would have reduced total IDA funding by 39% and total emergency food assistance funding by 38%.62 Congress did not enact any of the Administration's proposed changes but instead increased funding for McGovern-Dole, FFP Title II, and IDA.

FY2019 Budget Request

In its FY2019 budget request,63 the Trump Administration repeated its proposals from FY2018 to eliminate McGovern-Dole and FFP Title II funding and instead to fund all food assistance through the IDA subaccount. The request would decrease the IDA subaccount by 17% from FY2018-enacted levels. The House FY2019 agriculture appropriations bill (H.R. 5961) was reported by the House Appropriations Committee in May 2018. It would decrease FFP funding by $100 million and maintain McGovern-Dole funding at FY2018-enacted levels. The Senate approved an agricultural appropriations bill for FY2019 (H.R. 6147) in August 2018. The Senate-passed bill would maintain FFP funding at FY2018-enacted levels and increase McGovern-Dole funding by $2.6 million, or 1%. In September 2018, President Trump signed a continuing resolution (P.L. 115-245) funding agriculture-related programs through December 7, 2018.

Legislation in the 115th Congress

The House and Senate 2018 Farm Bills (H.R. 2)

On June 21, 2018, the House passed the Agriculture and Nutrition Act of 2018 (H.R. 2). The Senate subsequently passed its version of H.R. 2, the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, on June 28, 2018.64 Both the House and Senate farm bills would make changes to U.S. international food assistance programs. Both bills would amend FFP Title II by removing the requirement to monetize a minimum of 15% of Title II non-emergency commodities. The bills would also increase the minimum annual funding allocation for FFP Title II non-emergency assistance from $350 million to $365 million of the annual funds appropriated for FFP Title II. Both bills would include outlays for food security activities authorized by the FAA as part of the minimum non-emergency allocation. The Senate bill would also include Farmer-to-Farmer outlays as part of the minimum non-emergency allocation.

The House and Senate farm bills would amend the McGovern-Dole program by directing the Secretary of Agriculture to ensure, to the extent practicable, that assistance coincides with the beginning of the school year and other relevant times during the school year. The Senate bill would authorize USDA to provide locally and regionally procured foods under the McGovern-Dole program in addition to U.S.-sourced foods. It would authorize up to 10% of funds appropriated to the McGovern-Dole program to be used for LRP activities. The Senate bill would also amend the Food for Progress program by designating the Secretary of Agriculture, rather than the President, as having program authority. The bill would authorize a portion of Food for Progress funds to directly fund food security projects in recipient countries rather than monetization proceeds funding all food security projects.

Both the House and Senate bills would also amend reporting requirements to allow USAID and USDA to submit annual reports on international food assistance activities either jointly or separately. Current law requires the two agencies to jointly prepare and submit an annual report.

The House bill would extend the labeling requirement—that all food aid be labeled as provided by the United States—to apply to food procured outside the United States. The House bill would also amend the requirement that food aid not interfere with markets in recipient countries to apply to all forms of food assistance, including cash-based assistance. The Senate bill does not contain such provisions.

The Senate bill would create a new initiative—International Food Security Technical Assistance—that would provide technical assistance to NGOs, IOs, foreign governments, or U.S. government agencies to implement projects to improve international food security. The initiative would prioritize projects related to developing food and nutrition safety net systems in food-insecure countries. The Senate bill authorizes $1 million in annual funding for this initiative. The House bill does not contain such provisions.

The Global Food Security Reauthorization Act of 2017

In October 2018, President Trump signed the Global Food Security Reauthorization Act of 2017 (P.L. 115-266) into law. The bill reauthorizes the GFSA—and therefore EFSP and the Feed the Future initiative—through 2023. The bill authorizes appropriations of $2.8 billion per year for EFSP and $1.0 billion per year for the Department of State and USAID to carry out the Global Food Security Strategy (GFSS).65 The Obama Administration created the GFSS in 2016 in response to the passage of the original GFSA.66

The Food for Peace Modernization Act (S. 2551/H.R. 5276)

In March 2018, S. 2551/H.R. 5276, the Food for Peace Modernization Act, was introduced. Both bills would change FFPA requirements by reducing the share of aid that must be U.S. commodities from 100% to 25%. The remaining 75% could be in the form of U.S. commodities or cash-based assistance. The bills would also eliminate the requirement that 15% of food aid be monetized, replacing this required minimum with the option to monetize up to 15% of food aid. S. 2551 and H.R. 5276 would also add the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and the House and Senate Appropriations Committees as committees receiving reports on international food assistance activities from USAID and USDA.67 Lastly, the bills would remove references in statute to using abundant U.S. agricultural productivity to deliver aid, emphasizing instead the goals of promoting agricultural-led growth in developing countries and reducing long-term reliance on U.S. foreign assistance. S. 2551 was referred to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and H.R. 5276 was referred to the House Agriculture Committee.

Appendix. U.S. International Food Assistance Programs

|

Program |

Year Began |

Statutory Authority |

Funding |

E or NE |

Delivery Method |

Implementing Agency |

|

Food for Peace Title II |

1954 |

FFPA |

Agriculture appropriations |

E+NE |

In-kind |

USAID |

|

Bill Emerson Humanitarian Trust (BEHT) |

1980a |

FFPA |

Mandatory appropriationsb |

E |

In-kind |

USDA |

|

Food for Peace Title V (Farmer-to-Farmer) |

1985c |

FFPA |

Agriculture appropriations |

NE |

Technical assistance |

USAID |

|

Food for Progress |

1985 |

FFPA |

Mandatory appropriationsb |

NE |

In-kind |

USDA |

|

McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition |

2002 |

FFPA |

Agriculture appropriations |

NE |

In-kind |

USDA |

|

Emergency Food Security Program (EFSP) |

2010d |

FAA |

SFOPS appropriations |

E |

Cash-based |

USAID |

Source: Compiled by CRS

Notes: E = Emergency; NE = Non-emergency; FFPA = Food for Peace Act of 1954, as amended (P.L. 83-480); FAA = Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended (P.L. 87-195); SFOPS = State and Foreign Operations; USAID = U.S. Agency for International Development; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture.

a. Congress first authorized BEHT in its current form in the Africa: Seeds of Hope Act of 1998 (P.L. 105-385), but Congress authorized its predecessor, the Food Security Wheat Reserve, in the Agricultural Trade Act of 1980 (P.L. 96-494).

b. Authorizing legislation establishes mandatory funding and the borrowing authority of USDA's Commodity Credit Corporation finances program activities.

c. Congress authorized Food for Peace Title V in the Food for Peace Act of 1966 (P.L. 89-808) but did not fund the program until 1985.

d. USAID first used EFSP in FY2010 based on authority in the FAA. Congress permanently authorized EFSP in the Global Food Security Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-195).