Overview

Congress plays a significant role in U.S. policymaking toward the Palestinians. Since the United States established ties with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) during the 1990s, the United States has sought to help facilitate a negotiated solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, counter Palestinian terrorist groups, and provide certain types of assistance to Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. After the signing of the Israel-PLO Declaration of Principles in 1993, Congress has committed more than $5 billion in bilateral assistance to the Palestinians. See CRS Report RS22967, U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians, by Jim Zanotti, for more information.

Palestinian National Identity and Aspirations

The Palestinians are Arabs who live in the geographical area comprising present-day Israel, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip, or who have historical and cultural ties to that area. Since the early 20th century, the dominant Palestinian national goal has been to establish an independent state in historic Palestine (the area covered by the British Mandate until the British withdrawal in 1948). Over time, Palestinians have debated among themselves, with Israelis, and with others over the nature and extent of such a state and how to achieve it. (For additional background, see Appendix A.)

|

Palestinian Views on Statehood and Methods of Pursuing It (based on September 5-8, 2018, poll held among Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza)

Source: Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PCPSR), Public Opinion Poll No. 69. |

Today, Fatah and Hamas are the largest Palestinian political movements (see Appendix B and "Hamas" for profiles of both groups).1 The positions that their leaders express reflect two basic cleavages in Palestinian society:

- 1. Between those (several in Fatah, including its leader Mahmoud Abbas) who seek to establish a state in the West Bank and Gaza by nonviolent means—negotiations, international diplomacy, civil disobedience—and those (Hamas) who insist on maintaining violence against Israel as an option;2 and

- 2. Between those (Fatah) who favor a secular model of governance and those (Hamas) who call for a society governed more by Islamic norms.

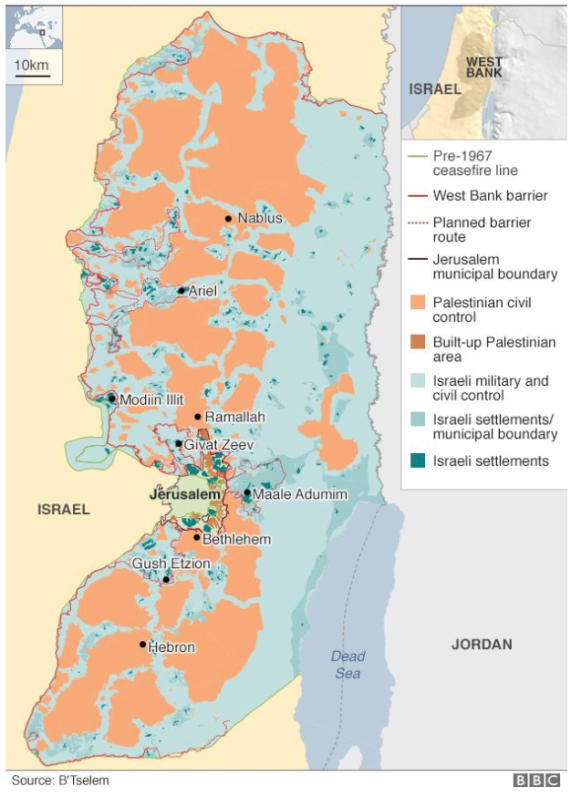

The differences between these two factions are reflected in Palestinian governance. In the West Bank, a Fatah-led Palestinian Authority (PA) exercises limited self-rule in specified urban areas (where Israel maintains overarching control). In Gaza, Hamas maintains de facto control. See Figure 1 and Figure 2 for maps of both territories.

International diplomacy aimed at resolving Israeli-Palestinian disputes and advancing Palestinian national goals has stalled. Many Palestinians assert that U.S. policy reflects a pro-Israel bias and a lack of sensitivity to PLO Chairman and Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas's domestic political rivalry with Hamas.3 Since a wave of unrest that started in 2011 presented Arab leaders with a range of domestic and other regional concerns, Arab states that had traditionally championed the Palestinian cause have focused on it less. Many have built or strengthened informal ties with Israel based on common concerns regarding Iran and its regional influence.

Citing the lack of progress in negotiations with Israel, Abbas and his colleagues have sought support for Palestinian national aspirations in the United Nations and other international fora. Some Palestinian and international intellectuals advocate the idea of a binational or one-state idea as an alternative to a negotiated two-state solution with Israel. However, when asked to choose between different scenarios in a September 2018 poll, 53% of Palestinians supported a two-state solution and only 24% supported a "one-state solution."4

The "Palestinian question" is important not only to Palestinians, Israelis, and their Arab state neighbors, but also to many countries and nonstate actors in the region and around the world—including the United States—for a variety of religious, cultural, and political reasons. For more than 70 years, the issue has been one of the most provocative in the international arena.

U.S.-Palestinian Tensions

The Trump Administration's relations with the PLO are tense. After President Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel's capital in December 2017 and announced that the U.S. embassy would move there from Tel Aviv, PLO Chairman and PA President Abbas broke off high-level political contacts with the United States. The following have taken place since:

- U.S. funding reductions. In September 2018, $231.5 million in FY2017 U.S. bilateral economic aid originally intended for the West Bank and Gaza was reprogrammed elsewhere, and the Administration announced an end to U.S. contributions to the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA).5

- PLO office closure. In September 2018, the Administration announced the closure of the PLO's representative office in Washington, DC.

- International Court of Justice (ICJ) case on Jerusalem. In September 2018, the PLO filed suit to have the ICJ order the United States to remove its embassy from Jerusalem, based on a requirement in the 1961 Vienna Convention of Diplomatic Relations for a country to locate its embassy on the territory of a host state.

- U.S. consulate general in Jerusalem merges into embassy. In October 2018, the Administration announced that the U.S. consulate general in Jerusalem would merge into the U.S. embassy to Israel.6 The consulate general had been an independent diplomatic mission responsible for ties with Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza.

In September, President Trump also indicated for the first time that his preferred outcome to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a two-state solution—a goal that previous Administrations pursued either implicitly or explicitly since the peace process of the 1990s. He also anticipated releasing a peace plan that his Administration has been developing sometime in the following two to four months.7 Previously, some former U.S. officials had cautioned against presenting a plan given Palestinian opposition.8 The President and his advisors express confidence that the Palestinians will ultimately renew ties with them and consider joining negotiations based on U.S. proposals.

Some Administration advisors have asserted that they are discarding failed diplomatic frameworks of the past and helping the Palestinians come to terms with the realities they will face in a future negotiation. For example, White House special advisor (and President Trump's son-in-law) Jared Kushner has said, "All we're doing is dealing with things as we see them and not being scared out of doing the right thing. I think, as a result, you have a much higher chance of actually achieving a real peace."9 For more information on Israeli-Palestinian diplomacy, see CRS Report R44245, Israel: Background and U.S. Relations in Brief, by Jim Zanotti.

To date, President Abbas and other PLO/PA officials have not shown willingness to resume contacts with the Administration in the context of their dealings with Israel, other than on working-level consultations on matters such as security. Instead the PLO/PA has focused its public efforts on rallying support for the Palestinians within the United Nations and other international fora in opposition to U.S. and Israeli policies.10 Additionally, in a September 2018 poll, 62% of Palestinians opposed resuming dialogue with the Trump Administration.11

Changes to Diplomatic Facilities

During 2018, the Trump Administration has instituted changes affecting both the PLO's representative office in the United States and the U.S. diplomatic facility in Jerusalem with responsibility for Palestinian relations.

Closure of PLO Office in Washington, DC

On September 10, 2018, the State Department announced that the office maintained by the PLO in Washington, DC, would cease operating. Though not diplomatically accredited, the office had functioned since the 1990s as a focal point for U.S.-Palestinian relations.

Timeline of Key Events

|

1978 |

PLO opens office in Washington to disseminate information about itself and the Palestinian cause. |

|

1987 |

Congress passes the Anti-Terrorism Act of 1987 (Title X of P.L. 100-204), which (under Section 1003) prohibits the PLO from maintaining an office in the United States. President Reagan signs P.L. 100-204 in December but adds a signing statement saying that "the right to decide the kind of foreign relations, if any, the United States will maintain is encompassed by the President's authority under the Constitution, including the express grant of authority in Article II, Section 3, to receive ambassadors."12 The State Department instructs the PLO to close its office. |

|

1994 |

As the Oslo peace process gets underway, the PLO opens a representative office in Washington. Despite the prohibition of a PLO office in P.L. 100-204, Congress provides waiver authority to the executive branch. |

|

1997 |

The PLO office briefly closes after a lapse in waiver authority, and reopens after Congress reinstitutes the waiver and the executive branch exercises it. |

|

2017 |

The State Department announces in November that it cannot renew the waiver (required every six months) because of statements made by Palestinian leaders about the International Criminal Court,13 but allows the PLO office to remain open so long as its activities are limited "to those related to achieving a lasting, comprehensive peace between the Israelis and Palestinians."14 A State Department spokesperson justifies the actions by saying that they "are consistent with the president's authorities to conduct the foreign relations of the United States."15 |

|

2018 |

The State Department announces the closure of the PLO office in September. |

The State Department announcement from September 10 read as follows:

The Administration has determined after careful review that the office of the General Delegation of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in Washington should close. We have permitted the PLO office to conduct operations that support the objective of achieving a lasting, comprehensive peace between Israelis and the Palestinians since the expiration of a previous waiver in November 2017. However, the PLO has not taken steps to advance the start of direct and meaningful negotiations with Israel. To the contrary, PLO leadership has condemned a U.S. peace plan they have not yet seen and refused to engage with the U.S. government with respect to peace efforts and otherwise. As such, and reflecting Congressional concerns, the Administration has decided that the PLO office in Washington will close at this point. This decision is also consistent with Administration and Congressional concerns with Palestinian attempts to prompt an investigation of Israel by the International Criminal Court.

The United States continues to believe that direct negotiations between the two parties are the only way forward. This action should not be exploited by those who seek to act as spoilers to distract from the imperative of reaching a peace agreement. We are not retreating from our efforts to achieve a lasting and comprehensive peace.16

The next day at a press briefing, the State Department spokesperson suggested that the "office could reopen in the future" if the Palestinians take meaningful steps in the "direction of advancing peace."17

Merger: U.S. Consulate General in Jerusalem into U.S. Embassy to Israel

On October 18, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that the U.S. consulate general in Jerusalem and the U.S. embassy to Israel would merge into a single diplomatic mission. Secretary Pompeo said the following:

This decision is driven by our global efforts to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of our operations. It does not signal a change of U.S. policy on Jerusalem, the West Bank, or the Gaza Strip. As the President proclaimed in December of last year, the United States continues to take no position on final status issues, including boundaries or borders. The specific boundaries of Israeli sovereignty in Jerusalem are subject to final status negotiations between the parties.18

Secretary Pompeo also said that the United States would "continue to conduct a full range of reporting, outreach, and programming in the West Bank and Gaza as well as with Palestinians in Jerusalem through a new Palestinian Affairs Unit inside U.S. Embassy Jerusalem."19 This unit is to operate from the building that previously functioned as the consulate general. In a subsequent briefing, a State Department spokesperson said that the merger has not taken place yet, and did not announce a specific timeline.20

The consulate general, established in 1928, had for decades served as an independent diplomatic mission that engaged with the Palestinians and worked in parallel with, rather than as a part of, the U.S. embassy to Israel.

Perhaps because the merger happened a few months after the U.S. embassy opened in Jerusalem, and one month after the announcement of the PLO office's closure in Washington, DC, many observers view the end of the consulate general's independent status as an additional downgrade in U.S. relations with the Palestinians. A former U.S. official has argued that the merger works against Palestinian aspirations for a capital in East Jerusalem and will harm U.S. diplomatic reporting on the Palestinians by subjecting it to the embassy's scrutiny.21 A close advisor to PLO Chairman and PA President Abbas responded to the merger by saying that President Trump was "cutting the last connection he is said to have with the Palestinian people. He is practically saying Jerusalem is for Israel."22

Issues for Congress

While the Administration has had difficulties dealing with the PLO/PA in 2018, congressional actions also have affected U.S. relations with the Palestinians. Although Congress still permits some funding for the Palestinians, its passage of the Taylor Force Act (Title X of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018, or P.L. 115-141) in March 2018 placed a number of conditions on that funding.23 As Congress considers legislative options—including on annual appropriations for the Palestinians—and exercises oversight over Israeli-Palestinian developments, Members may consider a number of issues, including the following:

- various aspects of U.S.-Palestinian relations;

- the status of Israeli-Palestinian diplomacy and Palestinian international initiatives;

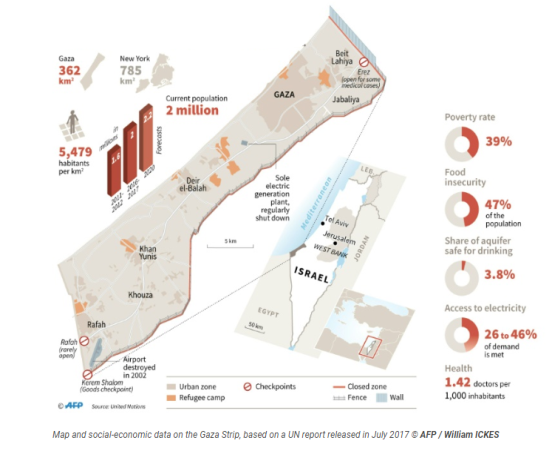

- humanitarian and economic development concerns, especially in Gaza;

- countering terrorism from Hamas and other groups, including rocket attacks from Gaza that have escalated during fall 2018;

- the surrounding region's effects on the West Bank and Gaza, and vice versa; and

- Palestinian domestic leadership and civil society.

|

|

Notes: All boundaries and depictions are approximate. |

|

|

Notes: All boundaries and depictions are approximate. |

Domestic Matters

Demographic Profile

An estimated 4.82 million Palestinians live in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem—approximately 2.94 million in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, and 1.88 million in Gaza.24 Of these, more than 2 million are registered as refugees in their own right or as descendants of the original refugees from the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. In addition, approximately 593,000 Jewish Israeli citizens live in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. More than 3 million Palestinians are registered as refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria,25 in addition to nonrefugees living in these states and elsewhere around the world.

|

Country or Region |

Population |

|

|

West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem |

|

|

|

Israel |

|

|

|

Arab states |

|

|

|

Other states |

|

|

|

Total |

|

Source: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. The figure for West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem is as of 2016; the other figures are as of 2015.

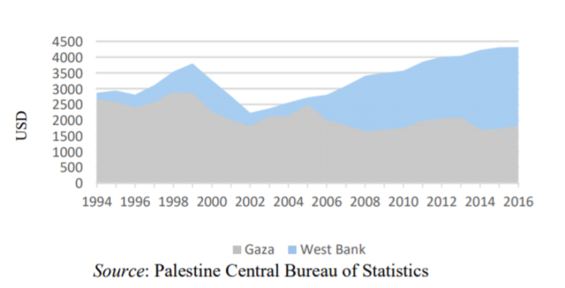

West Bank Palestinians generally are wealthier, better educated, and more secular than their Gazan counterparts. Palestinians are relatively well educated compared with other Arab populations, with an adult literacy rate of 97%.26 The Palestinian population in the West Bank and Gaza is approximately 98% Sunni Muslim; approximately 1% is Christian of various denominations.27

|

Statistic |

West Bank |

Gaza Strip |

Combined |

|

Population |

2,940,000 |

1,880,000 |

4,820,000 |

|

Refugees |

810,000 |

1,300,000 |

2,110,000 |

|

Median age (2017 est.) |

21.1 |

16.9 |

- |

|

Population growth rate |

1.8% |

2.3% |

- |

|

Real GDP growth rate |

4.7% |

0.0% |

|

|

GDP per capita (2016 est.) |

$2,279 |

$1,038 |

|

|

Unemployment rate (2018 est.) |

19.0% |

53.7% |

|

|

Inflation rate (2017 est.) |

- |

- |

0.2% |

|

Exports (2017 est.) |

- |

- |

$2.1 bil |

|

Export commodities |

stone, olives, fruits, vegetables |

fruits, vegetables, flowers, fish |

- |

|

Export partners |

- |

- |

Israel 79.8%, |

|

Imports (2017 est.) |

$6.6 bil |

||

|

Import commodities |

food, consumer goods, construction materials, petroleum, chemicals |

food, consumer goods, fuel |

- |

|

Import partners |

- |

- |

Israel 58.1%, European Union 12.4%, Arab States 6.2% |

Sources: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook, World Bank, Economist Intelligence Unit, UNRWA.

Notes: Population figures exclude Israeli settlers.

Palestinian Leadership

Fatah Leader Mahmoud Abbas (aka "Abu Mazen")

Abbas, by virtue of his status as the current PLO chairman, PA president, and head of Fatah, is generally regarded as the leader of the Palestinian national movement, despite Hamas's large measure of control over Gaza. In the 1970s and 1980s, Abbas became a top deputy to Yasser Arafat when Arafat headed Fatah and the PLO. He is widely seen as one of the main architects of the peace process, having led the Palestinian negotiating team at the secret Oslo talks with Israel in the early 1990s.28

|

Mahmoud Abbas: Biography Abbas was born in 1935 in Safed in what is now northern Israel. Abbas and his family left for Syria as refugees in 1948 when Israel was founded. He earned a B.A. in law from Damascus University and a Ph.D. in history from Moscow's Oriental Institute.29 Abbas was an early member of Fatah, joining in Qatar, and became head of the PLO's national and international relations department in 1980. Following the Oslo agreements of the mid-1990s, Abbas returned to the Palestinian territories in 1995 and took residences in Gaza and Ramallah. Together with Yossi Beilin (then an Israeli Labor Party government minister), Abbas drafted a controversial "Framework for the Conclusion of a Final Status Agreement Between Israel and the PLO" (better known as the "Beilin-Abu Mazen Plan") in October 1995.30 In March 2003, Abbas was named as the first PA prime minister, but never was given full authority because Arafat (then the PA president) insisted on retaining ultimate decisionmaking authority and control over security services. Abbas resigned as prime minister in September 2003, apparently as a result of frustration with Arafat, the United States, and Israel.31 |

Following Arafat's death in November 2004, Abbas succeeded Arafat as chairman of the PLO's Executive Committee, and he won the election to succeed Arafat as PA president in January 2005 with 62% of the vote. His presidency has been marked by events that include

- Israel's 2005 unilateral withdrawal from Gaza;

- the January 2006 Hamas legislative electoral victory;

- the June 2007 Hamas takeover of Gaza; and

- subsequent diplomatic efforts that have alternated between U.S.-supported negotiations with Israel and Palestinian initiatives in various international fora.

Abbas appears motivated by a complex combination of factors that include safeguarding his personal authority and legacy, preventing destabilization and violence, and protecting his family members.32 Some observers have argued that after the Hamas takeover of Gaza left the PA without a functioning legislature or realistic prospects for future elections, Abbas's rule became more authoritarian and corrupt.33 According to a September 2018 poll, 62% of Palestinians want Abbas to resign as PA president.34

For additional background on Abbas, see Appendix B.

Hamas

Hamas (a U.S.-designated terrorist organization) is Fatah's main rival for leadership of the Palestinian national movement. Countering Hamas is a focal point for Israel and the United States.

Hamas's ideology combines Palestinian nationalism with Islamic fundamentalism. Hamas's founding charter committed the group to the destruction of Israel and the establishment of an Islamic state in all of historic Palestine.35 A 2017 document updated Hamas's founding principles. It clarified that Hamas's conflict is with the "Zionist project" rather than the Jews, and expressed willingness to accept a Palestinian state within the 1948-1967 armistice lines if it results from "national consensus."36 Since Hamas's inception during the first Palestinian intifada (or uprising) in 1987 (see Appendix A for more on the intifada), it has maintained its primary base of support and particularly strong influence in the Gaza Strip. It also has a significant presence in the West Bank and in various Arab countries.

The leadership structure of Hamas is opaque, and much of the open source reporting available on it cannot be independently verified. It is unclear who controls strategy, policy, and financial decisions. In previous years, some external leaders reportedly sought to move toward a less militant stance in exchange for Hamas obtaining a significant role in the PLO, which represents Palestinians internationally.

Overall policy guidance comes from a Shura (or consultative) Council, with reported representation from the West Bank, Gaza, and other places. Gaza-based Ismail Haniyeh is the overall leader of Hamas's political bureau (politburo). Yahya Sinwar, previously a top commander from Hamas's military wing, is the movement's leader for Gaza.37 The militia, known as the Izz al Din al Qassam Brigades,38 is led by Muhammad Deif,39 and may seek to drive political decisions via its control over security. Haniyeh, Sinwar, and Deif have all been named by the Treasury Department as Specially Designated Global Terrorists.

Sinwar's prominence has grown in 2018. In May, after Israeli soldiers killed tens of Palestinians around barriers at the Israel-Gaza frontier, he said that Hamas would pursue "peaceful, popular resistance" at a time when he faced pressure to respond more violently.40 Then, in October, Sinwar gave a lengthy interview in which he stated a desire for a cease-fire with Israel (which Egypt is trying to broker) in exchange for an end to the "siege" (access restrictions on Gaza) currently in place.41 According to a Gazan journalist, Hamas may consider a long-term cease-fire with Israel to be a better option than losing its control over Gaza—either via a large-scale conflict with Israel or a national unity agreement with the Abbas-led PA—and the domestic prestige that goes with it.42

For additional background on Hamas, see Appendix B.

Possible PLO/PA Succession Scenarios

Abbas's age and reports of his deteriorating health have contributed to widespread speculation about who might lead the PLO and PA next.43 Abbas could give up either the PLO position or the PA position and retain the other for some period of time. Possible successors to Abbas from Fatah/PLO circles include the following:

- Marwan Barghouti often leads in opinion polls,44 but is imprisoned by Israel for terrorist-related offenses allegedly committed during the second Palestinian intifada that started in 2000 (see Appendix A for more on the intifada).

- Muhammad Dahlan was a top security figure in Gaza under Arafat who enjoys support from some Arab states, but he was expelled from Fatah in 2011 after a falling out with Abbas and is currently based in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

- Majid Faraj (arguably Abbas's most trusted security figure), Saeb Erekat (a top PLO negotiator), and Salam Fayyad (a previous PA prime minister) have some prominence with outside actors, but questionable political clout with domestic constituencies. Mahmoud al Aloul and Jibril Rajoub have political heft within Fatah, but relatively less international experience.

A succession could present Hamas with opportunities to increase its influence, especially if the process does not definitively concentrate power around one or more non-Hamas figures. Though Hamas members have not run in past presidential elections, one or more could potentially run in future elections.

Under Article 37 of the Palestinian Basic Law,45 it appears that if Abbas were to leave office, the speaker of the Palestinian Legislative Council (currently Aziz Dweik, a member of Hamas) would take over duties as president for a period not to exceed 60 days, by which time elections for a more permanent successor are supposed to take place. The Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) has not been in session since Hamas forcibly took control of Gaza in 2007 and Abbas dismissed the Hamas-led PA government in response.

Succession to the PA presidency could be determined by elections or under the Palestinian Basic Law. Abbas's term of office was supposed to be four years, with a new round of elections initially planned for 2009 that would have allowed Abbas to run for a second and final term. However, the split between the Abbas-led PA in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza has indefinitely postponed PA elections, with the last presidential election having taken place in 2005 and the last legislative election in 2006. In December 2009, the PLO's Central Council voted to extend the terms of both Abbas and the current PLC until elections can be held. This precedent could lead to PLO action in selecting or attempting to select a successor to Abbas as PA president if elections are not held shortly after he leaves office.

Palestinian Governance

Achieving effective and transparent governance over the West Bank and Gaza and preventing Israeli-Palestinian violence has proven elusive since the limited self-rule experiment began in 1994. The split established in 2007 between the Abbas-led PA in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza arguably exacerbated these difficulties.

Palestinian Authority (PA)

The Palestinian National Authority (or Palestinian Authority, hereafter PA) was granted limited rule under Israeli occupational authority in the Gaza Strip and parts of the West Bank in the mid-1990s, pursuant to the Oslo agreements.46 Although not a state, the PA is organized like one—complete with executive, legislative, and judicial organs of governance, as well as security forces. Ramallah is its de facto seat, but is not considered to be the PA capital because of Palestinian political consensus that Jerusalem (or at least the part east of the 1967 lines) should be the capital of a Palestinian state.

The executive branch has both a president and a prime minister-led cabinet, and the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) is the PA's legislature (sidelined since Hamas's takeover of Gaza in 2007). The judicial branch has separate high courts to decide substantive disputes and to settle controversies regarding Palestinian basic law. There are also a High Judicial Council and separate security courts. The electoral base of the PA is composed of Palestinians from the West Bank, Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. One of the PLO's options is to restructure or dissolve the PA (either in concert with Israel or unilaterally) pursuant to the claim that the PA is a constitutional creature of PLO agreements with Israel.47

West Bank

The PA administers densely populated Palestinian areas in the West Bank subject to supervening Israeli control under the Oslo agreements (see Figure 1 above for map).48 Israel Defense Forces (IDF) soldiers regularly mount arrest operations to apprehend wanted Palestinians or foil terrorist plots. They maintain permanent posts throughout the West Bank and along the West Bank's administrative borders with Israel and Jordan to protect Jewish settlers and broader security interests. The IDF sometimes takes measures that involve the expropriation of West Bank land or dispossession of Palestinians from their homes and communities.

Coordination between Israeli and PA authorities generally takes place discreetly, given the political sensitivity for PA leaders to be seen as collaborating with Israeli occupiers. In 2002, at the height of the second intifada, Israel demonstrated its ability to reoccupy PA-controlled areas of the West Bank in what it called Operation Defensive Shield. The IDF demolished many official PA buildings, Palestinian neighborhoods, and other infrastructure.49

Since 2007, when the West Bank-Gaza split took place and Western efforts to bolster PA security forces in the West Bank resumed, some observers have noted signs of progress with PA security capabilities and West Bank economic development.50 It is less clear whether the progress they cite can be self-sustaining absent a broader political solution with Israel. According to one analysis, "With peace talks stalled and no genuine political horizon visible, many Palestinians simply do not buy the claim by [PA] General Intelligence head Majid Faraj that the PA [security forces are] a force for stability 'that should lead us to our independence.'"51

Gaza

Hamas's security control of Gaza (see Figure 2 above for map) presents a conundrum for the Abbas-led PA, Israel, and the international community. They have been unable to establish a durable political-security framework for Gaza that assists Gaza's population without bolstering Hamas. Breaking the deadlock on Gaza could include one or more of the following: (1) a political reunification of Gaza with the West Bank, (2) reducing restrictions on access and commerce, (3) a long-term Hamas-Israel cease-fire (such as the one that the two sides have reportedly sought for much of 2018). For more information, see "The Gaza Strip: Challenges" below.

Prospects for ending the West Bank-Gaza split are unclear. They appear to depend on Hamas's willingness to cede control of security in Gaza to the PA. PA President Abbas has insisted that he will not accept a situation where PA control is undermined by Hamas's militia.52 Hamas-PA relations worsened in March 2018 when a roadside bomb targeted PA Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah's motorcade during a rare visit by Hamdallah to Gaza. Hamas condemned the attack, but the PA blamed Hamas because of its overall control over security in Gaza.53

Hamas's preeminence in Gaza can be traced to 2006-2007. After victory in the 2006 PA legislative elections, Hamas consolidated its power in Gaza—while losing it in the West Bank—through violent struggle with Fatah in June 2007. Hamas's security forces have maintained power in Gaza ever since, even after its de facto government relinquished nominal responsibility to the PA in June 2014.

Since Hamas's 2007 takeover of Gaza, Israeli and Egyptian authorities have maintained strict control over Gaza's border crossings.54 Israel justifies the restrictions it imposes as a way to deny Hamas materials to reconstitute its military capabilities. However, the restrictions also limit commerce, affect the entire economy, and delay humanitarian assistance.55 For several years, Hamas compensated somewhat for these restrictions by routinely smuggling goods into Gaza from Egypt's Sinai Peninsula through a network of tunnels. However, after Egypt's military regained political control in July 2013, it disrupted the tunnel system.

Observers routinely voice concerns that if current arrangements continue, the dispiriting living conditions that have persisted since Israel's withdrawal in 2005 could feed radicalization within Gaza and pressure its leaders to increase violence against Israel for political ends.56 Israel disputes the level of legal responsibility for Gaza's residents that some international actors claim it retains—given its continued control of most of Gaza's borders, airspace, maritime access, and various buffer zones within the territory.

Within limited parameters amid Gaza's political uncertainties and access restrictions, UNRWA and other international organizations and nongovernmental organizations take care of many Gazans' day-to-day humanitarian needs. These groups play significant roles in providing various forms of assistance and trying to facilitate reconstruction from previous conflicts. For more information on Palestinian refugees, see Appendix B.

Economy

The economy in the West Bank and Gaza Strip faces structural difficulties—with Gaza's woes significantly worse (see Figure 3 below). Palestinians' livelihoods largely depend on their ties to Israel's relatively strong economy. Israel is the market for about 80% of West Bank/Gaza exports, and the source for about 60% of West Bank/Gaza imports.57 Palestinians are constrained from developing other external ties because of the layers of control that Israel has put in place to enforce security.

Because the PA has been unable to become self-sufficient, it has been acutely dependent on foreign assistance. Facing a regular annual budget deficit of over $1 billion, PA officials have traditionally sought aid from international sources to meet the PA's financial commitments.58 Part of the problem is a PA payroll that has become increasingly bloated over the PA's 24-year existence. Domestic corruption and inefficiency also appear to pose difficulties.59 Absent fundamental changes in revenue and expenses, which do not appear probable in the near term, the PA's fiscal dependence on external sources is likely to continue.

Lacking sufficient private sector employment opportunities in the West Bank and Gaza, many Palestinians have historically depended on easy entry into and exit out of Israel for their jobs and goods. Yet, the second intifada in 2000 reduced this access considerably. Israel constructed a West Bank separation barrier and increased security at crossing points, and unilaterally "disengaged" (withdrew its settlements and official military contingent) from Gaza in 2005. Israel now issues permits to control access. Its security forces generally allow very few people or goods to flow between Israel and Gaza, while periodically halting these flows between Israel and the West Bank.60

|

Figure 3. West Bank and Gaza: Real per Capita Gross National Income |

|

|

Source: World Bank. |

The Palestinians' alternatives to functional dependence on Israel's economy include

- attracting investment and building a self-sufficient economy (discussed below);

- looking to neighboring Egypt and Jordan (which struggle with their own political and economic problems) for economic integration; or

- depending indefinitely on external assistance.

For the West Bank and Gaza to attract enough long-term investment to become more self-sufficient, most observers agree that uncertainties regarding the political and security situation and Israeli restrictions on the movement of goods, people, and capital would need to be significantly reduced.61 Such changes may be untenable absent an overall resolution of Israeli-Palestinian disputes. In the meantime, donors and lenders occasionally provide emergency funding to stave off fiscal crisis.

For information on PA dealings in recent years with Israel to secure access to discounted fresh water, and how those dealings relate to Israeli dealings on water with Jordan, see CRS Report RL33546, Jordan: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jeremy M. Sharp.

The Regional and International Context

Almost every aspect of Palestinian existence has some connection with Israel. Israel occupies the West Bank and effectively annexed East Jerusalem after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War; and it maintains significant control over administrative borders, resources, and trade in both the West Bank and Gaza. Israelis and Palestinians vie for advantages in addressing these issues within regional and international foreign policy frameworks.

The Gaza Strip: Challenges

Gaza presents complicated challenges for the Palestinians who live there. Hamas, Israel, the PA, and several outside actors affect Gaza's difficult security, political, and humanitarian situations.

Past Conflicts and Current Security Concerns

Over the past decade, these situations have fueled cyclical conflicts between Israel and Hamas (along with other Palestinian militants based in Gaza) that could recur in the future.

|

Major Israel-Hamas Conflicts Since 2008 December 2008-January 2009: Israeli codename "Operation Cast Lead"

November 2012: "Operation Pillar of Defense (or Cloud)"

July-August 2014: "Operation Protective Edge/Mighty Cliff"

|

In the aftermath of each conflict, significant international attention focused on the still largely elusive tasks of

- improving humanitarian conditions and economic opportunities for Palestinians in Gaza; and

- preventing Hamas and other militants from reconstituting arsenals and military infrastructure.

No significant breakthrough has occurred to reconcile civilian infrastructure needs with security considerations.

Threats to Israel from Hamas and other militant groups based in Gaza have changed over time. Although Palestinian militants maintain rocket and mortar arsenals, Israel's Iron Dome defense system reportedly has decreased the threat to Israel from projectiles during this decade.62 Additionally, tunnels that Palestinian militants used somewhat effectively in the 2014 conflict have been neutralized to some extent by systematic Israeli efforts, with some financial and technological assistance from the United States.63 An Israeli military officer was cited in September 2018 as saying that Hamas is investing fewer resources in tunnels that cross into Israel, but continuing to strengthen tunnels within Gaza that could present difficulties for Israeli soldiers deployed inside the territory during a future conflict.64

Palestinian protests and violence along security fences that divide Gaza from Israel have attracted international attention in 2018. Some Gazans have demonstrated "popular resistance" in which crowds gather near the fences, and some people try to breach the fences or use rudimentary weapons (slingshots, basic explosives, burning tires) against Israeli security personnel. Others have used incendiary kites or balloons to set fires to arable land in southern Israel.65 The purpose of these tactics may be to provoke Israeli responses that evoke international sympathy for Palestinians and criticism of Israel—a dynamic that bolstered Palestinian national aspirations in the late 1980s during the first intifada.66 While some of these protests and riots have been organized on a grass-roots level, Hamas has reportedly become more directly involved as they have continued.67

Israel has used force in efforts to contain the protests and violence near the Gaza frontier. In spring 2018, Israeli personnel killed more than 120 Palestinians in Gaza, given their use of live fire to patrol the security fences around the territory. This led the U.N. Human Rights Council to call in May for an "independent, international commission of inquiry" to produce a report.68 In June, U.N. General Assembly Resolution ES-10/20 condemned Israeli actions against Palestinian civilians, as well as the firing of rockets from Gaza against Israeli civilians.69

Subsequently, Israel-Gaza altercations and occasional spikes in violence (including rocket barrages from Gaza and Israeli air strikes inside Gaza) have continued, fueling speculation about the possibility of a fourth major conflict and its regional implications.70 According to the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, as of October 22, during 2018 Israeli personnel had killed more than 200 Gazans and injured thousands more.71 In mid-November, Israel and Hamas narrowly averted all-out conflict after an Israeli raid uncovered by Hamas contributed to a major escalation that required Egyptian intervention to quiet.72

Humanitarian Conditions and External Assistance

The precarious security situation in Gaza is linked to humanitarian conditions, and because Gaza does not have a self-sufficient economy, external assistance largely drives humanitarian welfare. Recent U.S. and PA reductions in funding for Gaza have affected the humanitarian assessment. Much of the focus from international organizations has been on the possibility that funding cuts could make a difficult situation in Gaza worse.73 Gazans already face chronic economic difficulties and shortages of electricity and safe drinking water.74 According to the World Bank, large transfers of aid and PA money historically have kept Gaza's economy afloat, but those transfers have significantly declined since 2017. Furthermore:

In this environment the USD30 million per month reduction in PA payments in 2018, the winding down of the USD50-60 million per year [bilateral economic aid] operation of the US Government, and the cuts being made in the UNRWA program are having a significant effect on economic growth and unemployment.75

The possibility that humanitarian crisis could destabilize Gaza has prompted discussions and some efforts among U.S., Israeli, and Arab leaders aimed at improving living conditions and reducing spillover threats.76 In fall 2018, Israel started allowing shipments of Qatari fuel and cash into Gaza to partially alleviate the electricity shortages and compensate for the PA funding reductions.77

Public statements from Administration officials and some Members of Congress suggest differences of opinion on how U.S. policy should link humanitarian assistance with Israel-Hamas-PA political considerations. For example:

- On August 24, a State Department official defended the U.S. decision to reprogram bilateral economic aid away from the West Bank and Gaza by saying that "this decision takes into account the challenges the international community faces in providing assistance in Gaza, where Hamas control endangers the lives of Gaza's citizens and degrades an already dire humanitarian and economic situation."78

- On September 6, President Trump stated that he "stopped massive amounts of money we were paying to the Palestinians" and said that "we're not paying [them] until we make a [diplomatic] deal."79

- Later in September, 34 Senators and 112 Representatives sent letters to Trump Administration officials urging them to reverse the U.S. funding reductions with respect to bilateral economic aid and humanitarian contributions to UNRWA.80 Both letters expressed concern that the funding reductions would undermine, rather than advance, prospects for a negotiated solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.81

Threats Presented by Palestinian Terrorist Organizations

Hamas and seven other Palestinian groups have been designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) by the State Department: Abu Nidal Organization, Al Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades, Army of Islam, Palestine Liberation Front-Abu Abbas Faction, Palestine Islamic Jihad, Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command. Additional information on some of these organizations is available in Appendix B.

Since the Israel-PLO agreements of the 1990s, these groups have engaged in a variety of methods of violence, killing hundreds of Israelis—both military and civilian.82 Palestinians who insist that they are engaging in asymmetric warfare with a stronger enemy point to the thousands of deaths inflicted on Palestinians by Israelis since 1993,83 some through acts of terrorism aimed at civilians.84

Palestinian militants in Gaza periodically fire rockets and mortars into Israel indiscriminately. The possibility that a rocket threat could emerge from the West Bank is one factor some Israelis cite in explaining their reluctance to consider a full withdrawal from there.85

Isolated attacks still occur within Israel and the West Bank. Some are perpetrated by Palestinians who are unaffiliated with terrorist groups and who use small arms or vehicles as weapons. Antipathy between Jewish settlers and Palestinian residents in the West Bank leads to occasional attacks on both sides. Militants also stage attacks and attempt to capture Israeli soldiers, including at or near Gaza border crossings.

International Organizations

The PLO has pursued a number of international initiatives—opposed by the United States and Israel—that are part of a broader effort to obtain greater international recognition of Palestinian statehood. Some 137 out of 193 U.N. member states reportedly have formally recognized the state of Palestine that the PLO declared in 1988. These do not include the most politically and economically influential Western countries.

Efforts to Join Various International Fora (Including the U.N. and U.N. Entities)

The PLO's international initiatives are centered on the United Nations. In September 2011, PLO Chairman Abbas applied for Palestinian membership in the United Nations. Officially, the application remains pending in the Security Council's membership committee, whose members did not achieve consensus during 2011 deliberations.86 The application for Palestinian membership would likely face a U.S. veto if it came to a future vote in the Security Council. In fall 2011, the Palestinians obtained membership in the U.N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).87

Under U.S. laws passed in 1990 and 1994,88 Palestinian admission to membership in UNESCO in 2011 triggered the withholding of U.S. assessed and voluntary financial contributions to the organization. If the Palestinians were to obtain membership in other U.N. entities, the 1990 and 1994 U.S. laws might trigger withholdings of U.S. financial contributions to these entities.89 Such withholdings could adversely affect these entities' budgets and complicate the conduct of U.S. foreign policy within the U.N. system and other multilateral settings.

The following are some other significant steps for the PLO in international fora:

- On November 29, 2012, the U.N. General Assembly adopted Resolution 67/19. The resolution changed the permanent U.N. observer status of the PLO (recognized as "Palestine" within the U.N. system) from an "entity" to a "non-member state."90

- In 2016, the Palestinians acceded to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).91 Some Members of Congress called for U.S. funding of UNFCCC to be cut off under the 1994 law,92 but the State Department replied that no cutoff was required because UNFCCC is a treaty and the Palestinians had not joined an international organization.93

- In September 2017, the Palestinians obtained membership in Interpol.

- In May 2018, the Palestinians applied to join the U.N. Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)94 and deposited an instrument of accession to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) with the U.N. Secretary General.95 A U.S. official was quoted as saying that the Administration would "review the application of US legislative restrictions related to Palestinian membership in certain UN agencies and organizations," presumably referring to both UNCTAD and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (which implements the CWC).96

International Criminal Court Actions97

The Palestinians have taken various actions relating to the ICC since late 2014:

- In January 2015, Palestinian leaders deposited an instrument of accession for the "State of Palestine" to become party to the Rome Statute of the ICC, after declaring acceptance in December 2014 of ICC jurisdiction over crimes allegedly "committed in the occupied Palestinian territory, including East Jerusalem, since June 13, 2014."

- Later in January 2015, the U.N. Secretary-General, acting as depositary, stated that the Rome Statute would enter into force for the "State of Palestine" on April 1, 2015.98

- Later that same month, the ICC Prosecutor opened a preliminary examination into the "situation in Palestine" to determine "whether there is a reasonable basis to proceed with an investigation" against Israelis, Palestinians, or others, having found that the Palestinians had the proper capacity to accept ICC jurisdiction in light of the November 2012 adoption of U.N. General Assembly Resolution 67/19.99

- Palestinian leaders have provided information to the ICC on alleged Israeli crimes regarding both the summer 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict and settlement activity in the West Bank. In May 2018, Palestinian leaders made a formal referral of the "situation in Palestine" to the Prosecutor.100

As referenced above, the State Department cited Palestinian actions relating to the ICC in connection with the 2018 closure of the PLO office in Washington, DC. Various U.S. and Israeli officials have denounced Palestinian efforts that could subject Israelis to ICC investigation or prosecution.101

The ICC can exercise jurisdiction over alleged genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity ("ICC crimes") that occur on the territory of or are perpetrated by nationals of an entity deemed to be a State

- after the Rome Statute enters into force for a State Party;

- during a period of time in which a nonparty State accepts jurisdiction; or

- pursuant to a U.N. Security Council resolution referring the situation in a State to the ICC.

Palestinian accession and acceptance of jurisdiction grant the ICC Prosecutor authority to investigate all alleged ICC crimes committed after June 13, 2014, by any individual—Israeli, Palestinian, or otherwise—on "occupied Palestinian territory." However, Palestinian actions do not ensure any formal ICC investigation or prosecution of alleged ICC crimes. A party to the Rome Statute can refer a situation to the Court and is required to cooperate with the Prosecutor in her investigations, but it is the role of the Prosecutor to determine whether to bring charges against and prosecute an individual. In addition, a case is inadmissible before the ICC if it concerns conduct that is the subject of "genuine" legal proceedings (as described in Article 17 of the Statute) brought by a state with jurisdiction, including a state (such as Israel) that is not party to the Statute.

The ICC Prosecutor is required to notify all states with jurisdiction over a potential case, and such states are afforded the opportunity to challenge ICC jurisdiction over a case on inadmissibility grounds.

International Court of Justice Suit over U.S. Embassy in Jerusalem

In September 2018, the PLO filed suit to have the International Court of Justice (ICJ) order the United States to remove its embassy from Jerusalem.102 The suit is based on the PLO's argument that the 1961 Vienna Convention of Diplomatic Relations requires a country to locate its embassy on the territory of a host state. In response, the Trump Administration withdrew in October from the Convention's optional protocol, which gives the ICJ jurisdiction to hear disputes arising from the Convention. The U.S. withdrawal will not terminate the suit because it had already been filed. Questions surrounding how the ICJ will handle the suit may include whether "Palestine" is a state for purposes of having standing to pursue a case, and whether Israeli consent to ICJ jurisdiction is required given Israel's claims to Jerusalem.103

Appendix A. Historical Background

Palestinian political identity emerged during the British Mandate period (1923-1948), began to crystallize with the 1947 United Nations partition plan (General Assembly Resolution 181), and grew stronger following Israel's conquest and occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip in 1967. Although in 1947 the United Nations intended to create two states in Palestine—one Jewish and one Arab—only the Jewish state came into being. Varying explanations for the failure to found an Arab state alongside a Jewish state in mandatory Palestine place blame on the British, the Zionists, neighboring Arab states, the Palestinians themselves, or some combination of these groups.104

As the state of Israel won its independence in 1947-1948, roughly 700,000 Palestinians were driven or fled from their homes, an occurrence Palestinians call the nakba ("catastrophe"). Many ended up in neighboring states (Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan) or in Gulf states such as Kuwait. Palestinians remaining in Israel became Israeli citizens. Those who were in the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and Gaza were subject to Jordanian and Egyptian administration, respectively. With their population in disarray, and no clear hierarchical structure or polity to govern their affairs, Palestinians' interests were largely represented by Arab states who had conflicting interests.

1967 was a watershed year for the Palestinians. In the June Six-Day War, Israel decisively defeated the Arab states who had styled themselves as the Palestinians' protectors, seizing East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip (as well as the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt and the Golan Heights from Syria). Thus, Israel gained control over the entire area that constituted Palestine under the British Mandate. Israel's territorial gains provided buffer zones between Israel's main Jewish population centers and its traditional Arab state antagonists. These buffer zones remain an important part of the Israeli strategic calculus to this day.

After the 1967 war, Israel only effectively annexed East Jerusalem (as well as the Golan Heights), leaving the West Bank and Gaza under military occupation. However, both territories became increasingly economically linked with Israel. Furthermore, Israel presided over the settlement of thousands of Jewish civilians in both territories (although many more in the West Bank than Gaza)—officially initiating some of these projects and assuming security responsibility for all of them. Settlement of the West Bank increased markedly once the Likud Party, with its vision of a "Greater Israel" extending from the Mediterranean Sea to the Jordan River, took power in 1977. Having Israelis settle in the West Bank presented some economic and cultural opportunities for Palestinians, but also new challenges to their identity and cohesion, civil rights, and territorial contiguity. These challenges persist and have since intensified.

The Arab states' defeat in 1967, and Israeli rule and settlement of the West Bank and Gaza, allowed the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) to emerge as the representative of Palestinian national aspirations. Founded in 1964 as an umbrella organization of Palestinian factions and militias in exile under the aegis of the League of Arab States (Arab League), the PLO asserted its own identity after the Six-Day War by staging guerrilla raids against Israel from Jordanian territory. The late Yasser Arafat and his Fatah movement gained leadership of the PLO in 1969, and the PLO subsequently achieved international prominence on behalf of the Palestinian national cause—representing both the refugees and those under Israeli rule in the West Bank and Gaza. Often this prominence came infamously from acts of terrorism and militancy.

Although Jordan forced the PLO to relocate to Lebanon in the early 1970s, and Israel forced it to move from Lebanon to Tunisia in 1982, the organization and its influence survived. In 1987, Palestinians inside the West Bank and Gaza rose up in opposition to Israeli occupation (the first intifada, or uprising), leading to increased international attention and sympathy for the Palestinians' situation. In December 1988, as the intifada continued, Arafat initiated dialogue with the United States by renouncing violence, promising to recognize Israel's right to exist, and accepting the "land-for-peace" principle embodied in U.N. Security Council Resolution 242.105 Arafat's turn to diplomacy with the United States and Israel may have been partly motivated by concerns that if the PLO's leadership could not be repatriated from exile, its legitimacy with Palestinians might be overtaken by local leaders of the intifada in the West Bank and Gaza (which included Hamas). These concerns intensified when Arafat lost much of his Arab state support following his political backing for Saddam Hussein's 1990 invasion of Kuwait.

After direct secret diplomacy with Israel brokered by Norway, the PLO recognized Israel's right to exist in 1993, and through the "Oslo agreements" gained limited self-rule for Palestinians in Gaza and parts of the West Bank. The agreements were gradually and partially implemented during the 1990s, but the expectation that they would lead to a final-status peace agreement has not been realized.

Many factors have contributed to the failure to complete the Oslo process. A second Palestinian intifada from 2000 to 2005 was marked by intense terrorist violence inside Israel. In response, Israel took actions that it asserted were necessary to safeguard its citizens' security, rendering unusable much of the PA infrastructure built over the preceding decade. During the second intifada, U.S.- and internationally supported efforts to restart peace negotiations under various auspices failed to gain traction.

After Arafat's death in 2004 and his succession by Mahmoud Abbas, Israel unilaterally withdrew its settlers and military forces from Gaza in 2005. Despite forswearing responsibility for Gaza, Israel has continued to control most of Gaza's borders, airspace, maritime access, and even various buffer zones within the territory. The limited self-rule regime of the PA was undermined further by Hamas's legislative election victory in 2006, and its takeover of Gaza in 2007. Having different Palestinian leaders controlling the West Bank and Gaza since then has complicated the question of who speaks for the Palestinians both domestically and internationally.

Appendix B. Key Palestinian Factions and Groups

Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO)

The PLO is recognized by the United Nations (including Israel since 1993) as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, wherever they may reside. It is an umbrella organization that includes 10 Palestinian factions (but not Hamas or other Islamist groups). As described above, the PLO was founded in 1964, and, since 1969, has been dominated by the secular nationalist Fatah movement. Organizationally, the PLO consists of an Executive Committee, the Palestinian National Council (or PNC, its legislature), and a Central Council.106

After waging guerrilla warfare against Israel under the leadership of Yasser Arafat, the PNC declared Palestinian independence and statehood in 1988. This came at a point roughly coinciding with the PLO's decision to publicly accept the "land-for-peace" principle of U.N. Security Council Resolution 242 and to contemplate recognizing Israel's right to exist. The declaration had little practical effect, however, because the PLO was in exile in Tunisia and did not define the territorial scope of its state.107 The PLO recognized the right of Israel to exist in 1993 upon the signing of the Declaration of Principles between the two parties.

While the Palestinian Authority (PA) maintains a measure of self-rule over various areas of the West Bank, as well as a legal claim to self-rule over Gaza despite Hamas's security presence,108 the PLO remains the representative of the Palestinian people to Israel and other international actors. Under the name "Palestine," the PLO maintains a permanent observer mission to the United Nations in New York and in Geneva as a "non-member state," and has missions and embassies in other countries—some with full diplomatic status. The PLO also is a full member of both the Arab League and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation.

Fatah

Fatah, the secular nationalist movement formerly led by Yasser Arafat, has been the largest and most prominent faction in the PLO for decades. Since the establishment of the PA and limited self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza in 1994, Fatah has dominated the PA, except during the period of partial Hamas rule in 2006-2007. Yet, popular disillusionment has come from the failure to establish a Palestinian state, internecine violence, corruption, and poor governance. Arafat's 2004 death removed a major unifying symbol, further eroding Fatah's support under Mahmoud Abbas.

Fatah's 1960s charter has never been purged of its clauses calling for the destruction of the Zionist state and its economic, political, military, and cultural supports.109 Abbas routinely expresses support for "legitimate peaceful resistance" to Israeli occupation under international law, complemented by negotiations. However, some of the other Fatah Central Committee members are either less outspoken in their advocacy of nonviolent resistance than Abbas, or reportedly explicitly insist on the need to preserve the option of armed struggle.110

Other PLO Factions and Leaders

Factions other than Fatah within the PLO include secular groups such as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP, a U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization), the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and the Palestinian People's Party. All of these factions have minor political support relative to Fatah and Hamas.

A number of Palestinian politicians and other leaders without traditional factional affiliation have successfully gained followings domestically and in the international community under the PLO's umbrella, even some who are not formally affiliated with the PLO. These figures—such as Salam Fayyad, Hanan Ashrawi (a female Christian), and Mustafa Barghouti—often have competing agendas. Several of them support a negotiated two-state solution, generally oppose violence, and appeal to the Palestinian intellectual elite and to prominent Western governments and organizations.

Non-PLO Factions

Hamas111

Overview

Hamas grew out of the Muslim Brotherhood, a religious and political organization founded in Egypt in 1928 with branches throughout the Arab world. Hamas's emergence as a major political and military group can be traced to the first Palestinian intifada, which began in the Gaza Strip in 1987 in resistance to what Hamas terms the Israeli occupation of Palestinian-populated lands. The group presented an alternative to Yasser Arafat and his secular Fatah movement by using violence against Israeli civilian and military targets just as Arafat began negotiating with Israel. Hamas took a leading role in attacks against Israelis—including suicide bombings targeting civilians—during the second intifada (between 2000 and 2005). Shortly after Arafat's death in 2004, the group decided to directly involve itself in politics. In 2006, a year after the election of Fatah's Mahmoud Abbas as PA president, and just a few months after Israel's military withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, Hamas defeated Fatah in Palestinian Legislative Council elections. Subsequently, Israel, the United States, and others in the international community have sought to neutralize or marginalize Hamas.

According to the State Department's Country Reports on Terrorism for 2017, Hamas "is comprised of several thousand Gaza-based operatives."

External Support

Hamas reportedly receives support from a number of sources, including some states. Along with some other non-PLO factions, Hamas has historically received much of its political and material support (including funding, weapons, and training) from Iran. Hamas became distant from Iran when it broke with Syria's government in the early years of the country's civil war. However, the Hamas-Iran relationship reportedly revived—including financially—around 2017.112

Additionally, in 2014, a Treasury Department official stated publicly that Qatar "has for many years openly financed Hamas."113 Qatari officials have denied that their government supported Hamas financially and have argued that their policy is to support the Palestinian people.

In addition to external assistance from states, Hamas has other sources of support. According to the State Department's profile of Hamas in its Country Reports on Terrorism for 2017, the group "raises funds in Gulf countries" and "receives donations from Palestinian expatriates as well as its own charity organizations."

Other Rejectionist Groups

Several other small Palestinian groups continue to reject the PLO's decision to recognize Israel's right to exist and to conduct negotiations. They remain active in the West Bank and Gaza and retain some ability to carry out terrorist attacks and other forms of violence to undermine efforts at cooperation and conciliation. In Gaza, some observers speculate that Hamas permits or even supports the operations of some of these groups, including those with a presence in Egypt's Sinai Peninsula, without avowing ties to them. Such groups provide Hamas opportunities to tacitly acquiesce to attacks against Israel while avoiding direct responsibility.

Palestine Islamic Jihad (PIJ) 114

The largest of these other groups is Palestine Islamic Jihad (PIJ), a U.S.-designated FTO that, like Hamas, is an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood and receives support from Iran. PIJ emerged in the 1980s in the Gaza Strip as a rival to Hamas.

Since 2000, PIJ has conducted several attacks against Israeli targets (including suicide bombings), killing scores of Israelis.115 As demonstrated by events in fall 2018, PIJ militants in Gaza sometimes take the lead in firing rockets into Israel—perhaps to pressure Hamas into matching its hardline tactics or to demonstrate its credentials as a resistance movement to domestic audiences and external supporters.116

PIJ's ideology combines Palestinian nationalism, Sunni Islamic fundamentalism, and Shiite revolutionary thought (inspired by the Iranian revolution). PIJ seeks liberation of all of historic Palestine through armed revolt and the establishment of an Islamic state, but unlike Hamas has not established a social services network, formed a political movement, or participated in elections. Perhaps largely for these reasons, PIJ has never approached the same level of support among Palestinians as Hamas. Some PIJ leaders reside in Syria, Lebanon, or other Arab states.

According to the State Department's Country Reports on Terrorism for 2017, PIJ "has close to 1,000 members."

Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC)

Another—though smaller—Iran-sponsored militant group designated as an FTO is the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC). PFLP-GC is a splinter group from the PFLP, and its founder and secretary-general is Ahmed Jibril. According to the State Department's 2017 Country Reports on Terrorism, PFLP-GC's political leadership "is headquartered in Damascus, with bases in southern Lebanon and a presence in the Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon and Syria. The group also maintains a small presence in Gaza."

According to the State Department's Country Reports on Terrorism for 2017, PFLP-GC has several hundred members.

Salafist Militant Groups

A number of small Palestinian Salafist-Jihadist militant groups evincing affinities toward groups such as Al Qaeda or the Islamic State have arisen in the Gaza Strip. Some Salafist groups reportedly include former Hamas militia commanders who became disaffected by actions from Hamas that they deemed to be overly moderate. Salafist groups do not currently appear to threaten Hamas's rule in Gaza.

Palestinian Refugees

Of the some 700,000 Palestinians displaced before and during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, about one-third ended up in the West Bank, one-third in the Gaza Strip, and one-third in neighboring Arab countries. According to the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), there are roughly 5.4 million registered refugees (comprising original refugees and their descendants) in UNRWA's areas of operation—the West Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon.117 Jordan offered Palestinian refugees citizenship, partly owing to its previous unilateral annexation of the West Bank (which ended in 1988), but the other refugees in the region are generally stateless and therefore limited in their ability to travel. Many of the refugees remain reliant on UNRWA for food, health care, and education.

For political and economic reasons, Arab host governments generally have not actively supported the assimilation of Palestinian refugees into their societies. Even if able to assimilate, many Palestinian refugees hold out hope of returning to the homes they or their ancestors left behind or possibly to a future Palestinian state. Many assert a sense of dispossession and betrayal over never having been allowed to return to their homes, land, and property. Some Palestinian factions have organized followings among refugee populations, and militias have proliferated at various times in some refugee areas in Lebanon and Syria. The refugees seek to influence both their host governments and the PLO/PA to pursue a solution to their claims as part of any final status deal with Israel.

For additional information on Palestinian refugees and UNRWA (including recent developments regarding U.S. contributions), see CRS Report RS22967, U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians, by Jim Zanotti.