The 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97) temporarily authorized Opportunity Zone (OZ) tax incentives for investments held by Qualified Opportunity Funds (QOFs) in qualified OZs.1 The Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund (hereinafter, the "Fund"), organized under the Department of the Treasury, designated qualified census tracts that are eligible for OZ tax incentives after receiving recommendations from the head executives at the state level. Qualified OZ designations are in effect through 2026. The tax benefits for these investments include (1) a temporary tax deferral for capital gains reinvested in a QOF, (2) a step-up in basis for any investment in a QOF held for at least five years (10% basis increase) or seven years (15% basis increase), and (3) a permanent exclusion of capital gains from the sale or exchange of an investment in a QOF held for at least 10 years.

This report briefly describes what census tracts have been designated as an OZ, what types of entities can are eligible as QOFs, the tax benefits of investments in QOFs, and what economic effects can be expected from OZ tax incentives.

For further reading on the Fund's other programs and analysis of related policy issues, see CRS Report R42770, Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund: Programs and Policy Issues, by Sean Lowry. For updated guidance regarding OZ tax incentives, including any IRS notices and proposed regulations, see websites created by the Fund and IRS.2

Opportunity Zone Designations

To become a qualified OZ, the CEO (e.g., governor) of the state must have nominated, in writing, a limited number of census tracts to the Secretary of the Treasury.3 A nominated tract must have been either (1) a qualified low-income community (LIC), using the same criteria as eligibility under the New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC),4 or (2) a census tract that was contiguous with a nominated LIC if the median family income of the tract does not exceed 125% of that contiguous, nominated LIC.5 Nominations were due to the Fund by March 21, 2018.6

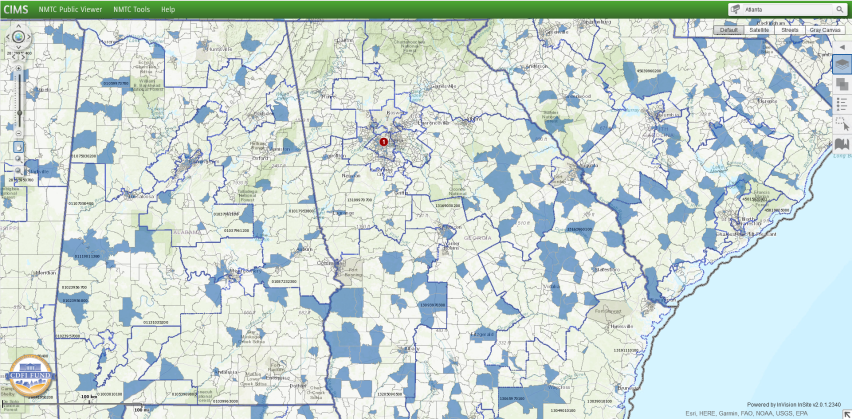

Figure 1 provides a screenshot of the Fund's online mapping tool, which displays census tracts that have been designated as a qualified OZ by the state or territory's CEO and approved by the Fund. A complete list of qualified OZs has been published as an IRS Internal Revenue Bulletin and is available on the Fund's "Opportunity Zone" website.7

|

Figure 1. CDFI Fund Mapping Tool Showing Designated Opportunity Zones (OZs) |

|

|

Source: CRS screenshot of CDFI Fund, CIMS mapping tool, accessed November 11, 2018, at https://www.cims.cdfifund.gov/preparation/?config=config_nmtc.xml. Notes: Designated OZs are shown in blue. Congressional district borders have been enabled in the above screenshot. |

P.L. 115-97 limits the number of census tracts within a state that can be designated as qualified OZs based on the following criteria:

- If the number of LICs in a state is less than 100, then a total of 25 census tracts may be designated as qualified OZs.

- If the number of LICs in a state is 100 or more, then the maximum number of census tracts that may be designated as qualified OZs is equal to 25% of the total number of LICs.

- Not more than 5% of the census tracts designated as qualified OZs in a state can be non-LIC tracts that are contiguous to nominated LICs.

Table 1 displays the maximum number of census tracts in each state or territory that were eligible for OZ designation under each of the two nomination criteria. These data, current as of February 27, 2018, were posted on the Fund's website before the qualified OZ recommendations issued by state or territory CEOs were certified.

Table 1. Maximum Number of Census Tracts Eligible

for Opportunity Zone Designation, by State or Territory

|

A |

B |

C |

|

|

State/Territory |

Total Number of Low-Income Community (LIC) Tracts in State |

Maximum Number of Tracts That Can Be Nominated (the Greater of 25% of All LICs or 25 If State Has Fewer Than 100 LICs) |

Maximum Number of Eligible Non-LIC Contiguous Tracts That Can Be Nominated (5% of Column B) |

|

Alabama |

629 |

158 |

8 |

|

Alaska |

55 |

25 |

2 |

|

American Samoa |

16 |

25 |

See Notes |

|

Arizona |

671 |

168 |

9 |

|

Arkansas |

340 |

85 |

5 |

|

California |

3,516 |

879 |

44 |

|

Colorado |

501 |

126 |

7 |

|

Connecticut |

286 |

72 |

4 |

|

Delaware |

80 |

25 |

2 |

|

District of Columbia |

97 |

25 |

2 |

|

Florida |

1,706 |

427 |

22 |

|

Georgia |

1,039 |

260 |

13 |

|

Guam |

31 |

25 |

2 |

|

Hawaii |

99 |

25 |

2 |

|

Idaho |

109 |

28 |

2 |

|

Illinois |

1,305 |

327 |

17 |

|

Indiana |

621 |

156 |

8 |

|

Iowa |

247 |

62 |

4 |

|

Kansas |

295 |

74 |

4 |

|

Kentucky |

573 |

144 |

8 |

|

Louisiana |

597 |

150 |

8 |

|

Maine |

128 |

32 |

2 |

|

Maryland |

593 |

149 |

8 |

|

Massachusetts |

550 |

138 |

7 |

|

Michigan |

1,152 |

288 |

15 |

|

Minnesota |

509 |

128 |

7 |

|

Mississippi |

399 |

100 |

5 |

|

Missouri |

641 |

161 |

9 |

|

Montana |

90 |

25 |

2 |

|

Nebraska |

176 |

44 |

3 |

|

Nevada |

243 |

61 |

4 |

|

New Hampshire |

105 |

27 |

2 |

|

New Jersey |

676 |

169 |

9 |

|

New Mexico |

249 |

63 |

4 |

|

New York |

2,055 |

514 |

26 |

|

North Carolina |

1,007 |

252 |

13 |

|

North Dakota |

50 |

25 |

2 |

|

Northern Mariana Islands |

20 |

25 |

See Notes |

|

Ohio |

1,280 |

320 |

16 |

|

Oklahoma |

465 |

117 |

6 |

|

Oregon |

342 |

86 |

5 |

|

Pennsylvania |

1,197 |

300 |

15 |

|

Puerto Rico |

835 |

See Notes |

See Notes |

|

Rhode Island |

78 |

25 |

2 |

|

South Carolina |

538 |

135 |

7 |

|

South Dakota |

69 |

25 |

2 |

|

Tennessee |

702 |

176 |

9 |

|

Texas |

2,510 |

628 |

32 |

|

Utah |

181 |

46 |

3 |

|

Vermont |

48 |

25 |

2 |

|

Virgin Islands |

13 |

25 |

See Notes |

|

Virginia |

847 |

212 |

11 |

|

Washington |

555 |

139 |

7 |

|

West Virginia |

220 |

55 |

3 |

|

Wisconsin |

479 |

120 |

6 |

|

Wyoming |

33 |

25 |

2 |

Source: CDFI Fund, "Opportunity Zones Information Resources," February 27, 2018, at https://www.cdfifund.gov/Pages/Opportunity-Zones.aspx.

Notes: These data are still available on the website, above, as of the publication date of this report.

Puerto Rico: The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123) deemed each population census tract in Puerto Rico that is a low-income community to be certified and designated as a qualified OZ. As of the time these data were being posted, the maximum number of tracts that can be nominated by Puerto Rico as well as the maximum number of Eligible Non-LIC Contiguous Tracts that could have been included in that nomination was being determined by the Fund.

USVI: The U.S. Virgin Islands could nominate Eligible Non-LIC Contiguous Tracts, provided that the nominated non-LIC tracts do not exceed 5% of all nominated tracts (both low-income communities and nominated contiguous tracts). Thus the Virgin Islands could nominate no more than one of its Eligible Non-LIC Contiguous Tracts.

Northern Mariana Islands and American Samoa: Neither the Northern Mariana Islands nor American Samoa had any Eligible Non-LIC Contiguous Tracts.

What Is a Qualified Opportunity Fund?

P.L. 115-97 defined QOFs as any investment vehicle which is organized as a corporation or partnership for the purpose of investing in qualified opportunity zone property (other than another QOF) that holds at least 90% of its assets in qualified OZ property. Qualified OZ property can be stock or partnership interest in a business located within a qualified OZ or tangible business property located in a qualified OZ. Qualified OZ property must have been acquired by the QOF after December 31, 2017. For each month that a QOF fails to meet the 90% requirement it must pay a penalty equal to the excess of the amount equal to 90% of its aggregate assets divided by the aggregate amount of qualified OZ property held by QOF multiplied by an underpayment rate (short-term federal interest rate plus three percentage points). There is an exception from this general penalty for reasonable cause.

The IRS instructs corporations or partnerships seeking to become QOFs to self-certify this status by filling out Form 8996 as part of their annual income tax filings.8 This self-certification process differs from the NMTC, in which the Fund takes prospective action to certify "community development entities" (CDE) before that CDE can receive an NMTC allocation.

What Are the Tax Benefits for Qualified Investments?

P.L. 115-97 provides for three main tax incentives to encourage investment in qualified OZs:

- 1. Temporary deferral of capital gains that are reinvested in qualified OZ property: Taxpayers can defer capital gains tax due upon sale or disposition of a (presumably non-OZ) asset if the capital gain portion of that asset is reinvested within 180 days in a QOF.9

- 2. Step-up in basis for investments held in QOFs: If the investment in the QOF is held by the taxpayer for at least five years, the basis on the original gain is increased by 10% of the original gain. If the OZ asset or investment is held by the taxpayer for at least seven years, the basis on the original gain is increased by an additional 5% of the original gain.

- 3. Exclusion of capital gains tax on qualified OZ investment returns held for at least 10 years: The basis of investments maintained (a) for at least 10 years and (b) until at least December 31, 2026, will be eligible to be marked up to the fair market value of such investment on the date the investment is sold. Effectively, this amounts to an exclusion of capital gains tax on any gains earned from the investment in the QOF (over 10 years) when the investment is sold or disposed.

Table 2 illustrates the tax benefits to a hypothetical investment of $100,000 in a QOF. This investment could be $100,000 in capital gains earned from the sale or disposition of another asset (e.g., real property) from outside of an OZ that is reinvested into a QOF within 180 days from the date of that sale or disposition. Taxes on these capital gains are deferred while the investment is held in a QOF.

Column A shows the investment's value over time, assuming a 7% annually compounded rate of return. This hypothetical investment is simplified to assume that an initial investment is made in a QOF in year one and the QOF constantly reinvests any returns to that initial investment (i.e., the QOF does not pay out a periodic dividends to the investor during the life of the investment).

Column B shows the increase in adjusted basis earned from holding that investment in a QOF over time: 10% of the original capital gain of $100,000 after the investment is held in a QOF for at least five years and 15% after the capital gain is held for at least seven years.

Column C shows the qualified OZ investment return. This is the 7% annual rate of return after the $100,000 in outside capital gains has been reinvested in a QOF. This return is subject to capital gains tax if the investment is sold or disposed within 10 years.

Column D shows the basis for capital gains tax if the investment in a QOF is sold or disposed in any of the 10 years shown. One of the three major economic incentives to investing in a QOF is the permanent exclusion of capital gains earned after the acquisition of the QOF investment.10 Put differently, in Year 10, the taxpayer pays no capital gains tax on earnings in column C and is subject to capital gains tax on $85,000 ($100,000*0.85) that was initially reinvested in a QOF. In contrast, if the investment in the QOF was sold in year nine, the taxpayer would have to pay capital gains tax on all of the QOF earnings (column C) but would still have the benefit of the step-up in basis on the initial investment in the QOF (column B).

Table 2. Illustration of Opportunity Zone (OZ) Tax Benefits

for a Hypothetical Investment of $100,000 in Reinvested Capital Gains

(Assuming an annual rate of return of 7%)

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

|

|

Year of Investment |

Investment Value |

Increase in Adjusted Basis |

Qualified OZ Investment Return |

Amount of Capital Gains Subject to Tax |

|

0 |

$100,000 |

$0 |

$0 |

$100,000 |

|

1 |

$107,000 |

$0 |

$7,000 |

$107,000 |

|

2 |

$114,490 |

$0 |

$14,490 |

$114,490 |

|

3 |

$122,504 |

$0 |

$22,504 |

$122,504 |

|

4 |

$131,080 |

$0 |

$31,080 |

$131,080 |

|

5 |

$140,255 |

$10,000 |

$40,255 |

$130,255 |

|

6 |

$150,073 |

$10,000 |

$50,073 |

$140,073 |

|

7 |

$160,578 |

$15,000 |

$60,578 |

$145,578 |

|

8 |

$171,819 |

$15,000 |

$71,819 |

$156,819 |

|

9 |

$183,846 |

$15,000 |

$83,846 |

$168,846 |

|

10 |

$196,715 |

$15,000 |

$96,715 |

$85,000a |

Source: CRS calculations.

Notes: This hypothetical calculates OZ tax benefits from $100,000 in capital gains earned from outside of an OZ (e.g., sale of appreciated real property) that is rolled over into a qualified opportunity fund (QOF), assuming constant reinvestment over the life of the OZ investment (i.e., no periodic dividends issued from the qualified opportunity fund to the investor). Generally, taxes on accrued capital gains (or losses) are not due in a particular tax year until the gain (or loss) is realized. This example does not include any economic benefit from the deferral of the capital gains of the initial $100,000 investment rolled into the OZ investment.

a. Investments maintained (a) for at least 10 years and (b) until at least December 31, 2026, will be eligible for permanent exclusion of capital gains tax on any gains from the qualified OZ portion of their investment when sold or disposed. In this hypothetical, the $96,715 in earnings over the 10 years that the investment is held in a QOF would be excluded from capital gains tax, and tax would be due on the initial $100,000 in outside capital gains rolled over into the QOF after applying the OZ adjusted basis increase benefit of 15% (i.e., tax due on $85,000 in capital gains).

Note that Table 2 only shows the tax-related benefits of investing in a QOF. It does not include the economic benefits of deferring capital gains tax on the initial $100,000 investment, which would depend on the time value of money. From an income tax perspective, though, deferral of capital gains tax just delays a tax liability from one period to another.

Actual QOF investment structures could differ from the arrangement in Table 2. As seen in the New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC), investors have developed financial structures that increase the amount of other funding from either private or public sources that are used with the NMTC (i.e., increasing leverage on the NMTC investment).11 Additional layers of financing structures could increase the complexity of investment arrangements and costs attributed to fees and transactional costs instead of development.12

OZ tax incentives are in effect from the enactment of P.L. 115-97 on December 22, 2017, through December 31, 2026. There is no gain or deferral available with respect to any sale or exchange made after December 31, 2026, and there is no exclusion available for investments in qualified OZs made after December 31, 2026.

What Economic Effects Can Be Expected?

OZs are an addition to the array of geographically targeted, federal programs and incentives for economic development. Examples of economic development incentives that are administered through the tax code include the NMTC,13 the low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC),14 and the tax credit for the rehabilitation of historic structures.15

Although any one of these tax incentives might not be sufficient enough to generate a positive investment return from an otherwise unprofitable development project, developers may be able to "stack" the benefits of multiple, federal tax incentives (as well as any state and local incentives) in order to make a project located in one area more profitable than competing alternatives. Studies find that place-based economic development incentives tend to shift investment from one area to another, rather than result in a net increase in aggregate economic activity.16

Comparisons may be made between the NMTC and OZ tax incentives. The OZ tax incentives provide relief from capital gains taxation, thereby directly benefiting owners of capital rather than low-income populations that live in OZs.17 Although the NMTC is an investment credit, it, like the OZ tax incentives, also directly benefits capital owners. The NMTC can be distinguished from the OZ tax incentives in several ways, though. First, Congress has capped the amount of NMTC allocations that the Fund may issue per year ($3.5 billion), thereby making these applications competitive because the demand for NMTC allocations exceeds the supply provided by Congress. In contrast, the maximum amount of tax benefits conferred by the OZ tax incentives are uncapped, much like many tax provisions—if a taxpayer qualifies for the special tax treatment, then they may claim it.

Second, the Fund evaluates NMTC applications based on a set of factors. One factor is the potential impact that the investments supported will have on "community outcomes," including benefits to low-income persons and jobs directly induced by the investments.18 Investments made by QOFs are eligible to benefit a broad range of potential projects, regardless of their potential "community outcomes."19

Third, NMTC recipients are required to adhere to a set of outcome-based reporting and compliance requirements.20 These metrics track the location and type of projects funded by NMTC allocations.21 No such outcome-based requirements are needed for OZ tax incentives.

Fourth, to become eligible for a NMTC allocation, a certified CDE must, among other criteria, have a primary mission of serving or providing investment capital to low-income communities. A governing or advisory board is supposed to hold the CDE accountable to that mission. QOFs are not required to be mission-oriented for the primary purposes of serving low-income communities or persons.

The Urban Institute analyzed the census tracts designated by the CEOs of the states and the District of Columbia, "scoring" each against measures of the investment flows they are receiving and the socioeconomic changes they have already experienced.22 Tracts that were selected by the state's respective CEO and designated as QOZs were compared with eligible, nondesignated tracts not selected by the CEO. CEOs in Montana, DC, Alaska, and Georgia selected areas with the lowest levels of preexisting investment.23 Conversely, CEOs in Hawaii, Vermont, Nebraska, and West Virginia selected areas with the highest levels of preexisting investment. The Urban Institute also found:

Designated tracks do have lower incomes, higher poverty rates, and higher unemployment rates than eligible nondesignated tracts (and the US overall average, which is as expected given eligibility criteria). Housing conditions trend in similar ways, with lower home values, rents, and homeownership rates. The designated tracts are also notably less white and more Hispanic and black than eligible nondesignated tracts. Age compositions are comparable. Education levels are somewhat lower among designated tracts than eligible nondesignated tracts…In terms of this program, there appears to be no targeting on the basis of urbanization. There is no difference in the share of designated and eligible nondesignated tracts that are located in metropolitan areas, in micropolitan areas, or in non-core-based statistical areas.24

The Joint Committee on Taxation initially estimated that the OZ tax incentives will result in a revenue loss to the federal government of $1.6 billion over 10 years.25 The revenue loss within the 10-year budget window is due to the relatively small revenue losses associated with the deferral of capital gains tax and the OZ basis adjustments in years five and seven. The largest tax benefit associated with OZ tax incentives, the exclusion of capital gains tax on qualified OZ investment returns in year 10, would fall outside of the 10-year budget window. Those revenue losses would not be expected until 2028 (i.e., FY2028-FY2029).