The Congressional Review Act (CRA) allows Congress to review certain types of federal agency actions that fall under the statutory category of "rules."1 Enacted in 1996 as part of the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act, the CRA requires agencies to report the issuance of "rules" to Congress and provides Congress with special procedures under which to consider legislation to overturn those rules.2 A joint resolution of disapproval will become effective once both houses of Congress pass a joint resolution and it is signed by the President, or if Congress overrides the President's veto.3

For an agency's action to be eligible for review under the CRA, it must qualify as a "rule" as defined by the statute.4 The class of rules covered by the CRA is broader than the category of rules that are subject to the Administrative Procedure Act's (APA's) notice-and-comment requirements.5 As such, some agency actions, such as guidance documents, that are not subject to notice-and-comment rulemaking procedures may still be considered rules under the CRA and thus could be overturned using the CRA's procedures.

The 115th Congress used the CRA to pass, for the first time, a resolution of disapproval overturning an agency guidance document that had not been promulgated through notice-and-comment procedures.6 The resolution was signed into law by the President on May 21, 2018.7 In all of the previous instances in which the CRA was used to overturn agency actions, the disapproved actions were regulations that had been adopted through APA rulemaking processes.8 This recent congressional action has raised questions about the scope of the CRA and Congress's ability to use the CRA to overturn agency actions that were not promulgated through APA notice-and-comment procedures.

Under the CRA, the expedited procedures for considering legislation to overturn rules become available only when agencies submit their rules to Congress.9 In many cases in which agencies take actions that meet the legal definition of a "rule" but have not gone through notice-and-comment rulemaking procedures, however, agencies fail to submit those rules.10 Thus, questions have arisen as to how Members can use the CRA's procedures to overturn agency actions when an agency does not submit the action to Congress.

This report first describes what types of agency actions can be overturned using the CRA by providing a close examination and discussion of the statutory definition of "rule." The report then explains how Members can use the CRA to overturn agency rules that have not been submitted to Congress.

Overview of the CRA

Under the CRA, before a rule can take effect, an agency must submit to both houses of Congress and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) a report containing a copy of the rule and information on the rule, including a summary of the rule, a designation of whether the rule is "major," and the proposed effective date of the rule.11 For most rules determined to be "major," the agency must allow for an additional period to elapse before the rule can take effect—primarily to give Congress additional time to consider taking action on the most economically impactful rules—and GAO must write a report on each major rule to the House and Senate committees of jurisdiction within 15 days.12 The report is to contain GAO's assessment of the agency's compliance with various procedural steps in the rulemaking process.

After a rule is received by Congress, Members have the opportunity to use expedited procedures to overturn the rule.13 A Member must submit the resolution of disapproval and Congress must take action on it within certain time periods specified in the CRA to take advantage of the expedited procedures, which exist primarily in the Senate.14 Those expedited, or "fast track," procedures include the following:

- a Senate committee can be discharged from the further consideration of a CRA joint resolution disapproving the rule by a petition signed by at least 30 Senators;

- any Senator may make a nondebatable motion to proceed to consider the disapproval resolution, and the motion to proceed requires a simple majority for adoption; and

- if the motion to proceed is successful, the CRA disapproval resolution would be subject to up to 10 hours of debate, and then voted upon. No amendments are permitted and the disapproval resolution requires a simple majority to pass.15

If both houses pass the joint resolution, it is sent to the President for signature or veto. If the President were to veto the resolution, Congress could vote to override the veto under normal veto override procedures.16

If a joint resolution of disapproval is submitted and acted upon within the CRA-specified deadlines17 and signed by the President (or if Congress overrides the President's veto), the CRA states that the "rule shall not take effect (or continue)."18 In other words, if part or all of the rule had already taken effect, the rule would be deemed not to have had any effect at any time.19 If a rule is disapproved, the status quo that was in place prior to the issuance of the rule would be reinstated.

In addition, when a joint resolution of disapproval is enacted, the CRA provides that a rule may not be issued in "substantially the same form" as the disapproved rule unless it is specifically authorized by a subsequent law. The CRA does not define what would constitute a rule that is "substantially the same" as a nullified rule.20

Types of Agency Actions Covered by the CRA

The CRA governs "rules" promulgated by a "federal agency," using the definition of "agency" provided in the APA.21 That APA definition broadly defines an agency as "each authority of the Government of the United States, ... but does not include ... Congress; ... the courts of the United States; ... courts martial and military commissions."22 Accordingly, the CRA generally covers rules issued by most executive branch entities.23 In the context of the APA, however, courts have held that this definition excludes actions of the President.24

The more difficult interpretive issue is what types of agency actions should be considered "rules" under the CRA.25 The CRA adopts a broad definition of the word "rule" from the APA, but then creates three exceptions to that definition.26 This APA definition of "rule" encompasses a wide range of agency action, including certain agency statements that are not subject to the notice-and-comment rulemaking requirements outlined elsewhere in the APA:

"[R]ule" means the whole or a part of an agency statement of general or particular applicability and future effect designed to implement, interpret, or prescribe law or policy or describing the organization, procedure, or practice requirements of an agency and includes the approval or prescription for the future of rates, wages, corporate or financial structures or reorganizations thereof, prices, facilities, appliances, services or allowances therefor or of valuations, costs, or accounting, or practices bearing on any of the foregoing[.]27

The CRA narrows this definition by providing that the term "rule" does not include

(A) any rule of particular applicability, including a rule that approves or prescribes for the future rates, wages, prices, services, or allowances therefor, corporate or financial structures, reorganizations, mergers, or acquisitions thereof, or accounting practices or disclosures bearing on any of the foregoing;

(B) any rule relating to agency management or personnel; or

(C) any rule of agency organization, procedure, or practice that does not substantially affect the rights or obligations of non-agency parties.28

Determining whether any particular agency action is a rule subject to the CRA therefore entails a two-part inquiry: first, asking whether the statement qualifies as a rule under the APA definition and, second, asking whether the statement falls within any of the exceptions noted above to the CRA's definition of rule. This section of the report walks through these two inquiries in more detail. First, while the APA's definition of "rule" is expansive, courts have held that "Congress did not intend that the ... definition ... be construed so broadly that every agency action" should be encompassed under this provision.29 As a preliminary matter, courts have distinguished agency rulemaking actions from adjudicatory and investigatory functions.30 And under the statutory text, to qualify as a rule, an agency statement must meet three requirements: it must be "of general ... applicability," have "future effect," and be "designed to implement, interpret, or prescribe law or policy."31 Second, even if an agency statement does qualify as an APA "rule," the CRA expressly exempts three categories of rules from its provisions: rules "of particular applicability," rules "relating to agency management or personnel," and "any rule of agency organization, procedure, or practice that does not substantially affect the rights or obligations of non-agency parties."32 Both inquiries are heavily fact specific, and require looking beyond a document's label to the substance of the agency's action.33

Determining Whether an Agency Action Is an APA Rule

The CRA defines the word "rule" by incorporating in part the APA's definition of that term.34 Although there is very little case law interpreting the meaning of "rule" under the CRA,35 cases interpreting the APA's definition of "rule" may provide persuasive authority for interpreting the CRA because the CRA explicitly relies on that provision as the basis for its own definition of the term "rule."36 The APA provides a general framework governing most agency action—not only agency rulemaking,37 but also administrative adjudications.38 The APA accordingly distinguishes different types of agency actions, separating rules from orders and investigatory acts.39 These distinctions may also be relevant when deciding whether an agency action is a rule subject to the CRA.

Differentiating "Rules," "Orders," and "Investigative Acts" under the APA

The APA distinguishes a "rule" from an "order," defining an "order" as "the whole or a part of a final disposition, whether affirmative, negative, injunctive, or declaratory in form, of an agency in a matter other than rule making but including licensing."40 Orders are the product of agency adjudication, in contrast to rules, which result from rulemaking.41 To determine whether an agency action is a rule or an order in the context of the APA, courts look beyond the document's label to the substance of the action.42 One federal court of appeals described the distinction between rulemaking and adjudication as follows:

First, adjudications resolve disputes among specific individuals in specific cases, whereas rulemaking affects the rights of broad classes of unspecified individuals.... Second, because adjudications involve concrete disputes, they have an immediate effect on specific individuals (those involved in the dispute). Rulemaking, in contrast, is prospective, and has a definitive effect on individuals only after the rule subsequently is applied.43

Courts have also distinguished rules from agency investigations.44 A separate provision of the APA addresses an agency's authority to compel the submission of information and perform "investigative act[s] or demand[s]."45 When agencies conduct investigative actions such as requiring regulated parties to submit informational reports, courts have held that they are not subject to the APA's rulemaking requirements.46 However, courts have also noted that some actions related to investigations may qualify as rules.47 For instance, in one case, a federal court of appeals observed that the procedures governing an agency's decision to investigate "are separate from and precede the agency's ultimate act," concluding that the procedures at issue constituted a rule.48

"Rules" under the APA

An agency statement will qualify as a "rule" under the APA definition if it (1) is "of general or particular applicability,"49 (2) has "future effect," and (3) is "designed to implement, interpret, or prescribe law or policy."50 With regard to the first requirement, as the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (D.C. Circuit) has noted, most agency statements will be "of general or particular applicability" and will fulfill this condition.51

The second requirement—that a rule be "of ... future effect"52—is the subject of some ambiguity. Courts have largely agreed that this requirement is likely intended to distinguish agency rulemaking from agency adjudication.53 Courts often differentiate rules and orders by noting that orders are retrospective, while rules have "future effect."54 Rules operate prospectively,55 in the sense that they are intended to "inform the future conduct" of those subject to the rules.56

Additionally, courts have sometimes said that the "future effect" requirement excludes any agency statements that do not "bind the agency."57 Thus, for example, in a concurring opinion in a 1988 Supreme Court case, Justice Scalia suggested that the "future effect" requirement must be read to mean "that rules have legal consequences only for the future."58 He argued that the only way to distinguish rules from orders—which can have both future and past legal consequences—was to define rules as having only prospective operation.59 Judge Silberman of the D.C. Circuit, concurring in an opinion from that court, drew on Justice Scalia's interpretation of this requirement to argue that it would be unreasonable to conclude that every single agency statement with future effect is a rule under the APA.60 Instead, he argued that only agency statements that "seek to authoritatively answer an underlying policy or legal issue" should be considered rules.61

These opinions raise several unanswered questions, which could suggest some hesitation before reading the phrase "future effect" in the APA definition of a rule to mean "binding." First, these cases do not fully explain what it means for an agency statement to be binding or address the case law suggesting that the term "future effect" merely pertains to the prospective nature of the statement.62 Second, and perhaps more critical, this case law reading "future effect" to mean that APA "rules" must bind the agency does not explain how to distinguish this requirement from the separate inquiry into whether an agency action is subject to notice-and-comment rulemaking procedures. As discussed in more detail below,63 some (but not all) APA "rules" must go through procedures commonly known as notice-and-comment rulemaking.64 To distinguish so-called "legislative" rules that are subject to notice-and-comment procedures from "interpretive" rules, which are not, courts generally ask whether the rule has "the force of law"65—or stated another way, whether the rule is "legally binding."66 Arguably, then, this "legal effect" test for notice-and-comment rulemaking may be equivalent to asking whether a rule binds an agency.67 However, the "future effect" inquiry tests whether an agency action is a "rule" under 5 U.S.C. §551(4), and the "legal effect" inquiry tests whether such a rule is subject to the notice-and-comment procedures outlined in 5 U.S.C. §553. Because the tests are tied to two distinct statutory provisions, they arguably should not both turn on whether a rule is legally binding.68 This is especially true where courts have generally held that interpretive rules may not be subject to notice-and-comment but are nonetheless "rules" within the meaning of the APA.69 The fact that Congress expressly exempted "interpretative rules" from the rulemaking procedures applicable to "rules"70 may itself suggest that such agency actions are rules—otherwise, the exemption would be unnecessary.71

The third requirement for an agency action to be considered an APA rule is that it must be "designed to implement, interpret, or prescribe law or policy."72 The D.C. Circuit has held that agency documents that merely state an "established interpretation" and "tread no new ground" do not "implement, interpret, or prescribe law or policy" and therefore are not rules.73 Similarly, an agency statement is not a rule if it "does not change any law or official policy presently in effect."74 Thus, courts have concluded that "educational"75 documents that merely "reprint[]"76 or "restate"77 existing law are not rules under the APA. The D.C. Circuit has also held that an agency's budget request is not a rule.78

Notice-and-Comment Rulemaking and Guidance Documents

The APA outlines specific rulemaking procedures that agencies must follow when they formulate, amend, or repeal a rule.79 The APA generally requires publication in the Federal Register and institutes procedural requirements that are often referred to as notice-and-comment rulemaking.80 Under notice-and-comment rulemaking, agencies must notify the public of a proposed rule and then provide a meaningful opportunity for public comment on that rule.81 However, not all agency acts that qualify as "rules" under the APA definition are required to comply with the APA's rulemaking procedures.82 In particular, the APA provides that notice and comment is not required for "interpretative rules, general statements of policy, or rules of agency organization, procedure, or practice."83 Additionally, the APA's rulemaking procedures do not, in relevant part, apply to "matter[s] relating to agency management or personnel."84 Therefore, agency statements such as guidance documents or procedural rules may not be required to undergo notice-and-comment rulemaking, but may still be APA "rules."

Courts frequently hold that agency's guidance documents are exempt from APA notice-and-comment rulemaking requirements because those documents are properly classified either as interpretative rules or as general policy statements.85 Interpretive rules merely explain or clarify preexisting legal obligations without themselves "purport[ing] to impose new obligations or prohibitions,"86 while general policy statements simply describe how an agency "will exercise its broad enforcement discretion"87 without binding the agency.88 But as mentioned above, the critical factor distinguishing both interpretive rules and general policy statements from "legislative" rules that must be promulgated through notice-and-comment procedures is "whether the agency action binds private parties or the agency itself with the 'force of law,'"89 or whether the rule "has legal effect."90 General policy statements ordinarily are not legally binding,91 and accordingly are not "substantive" rules required to undergo notice-and-comment rulemaking procedures.92

It should be noted that some cases from the D.C. Circuit have suggested that general policy statements are not "rules" at all under the APA definition.93 For example, in one case, the D.C. Circuit said that the "primary distinction between a substantive rule—really any rule—and a general statement of policy, then, turns on whether an agency intends to bind itself to a particular legal position."94 As discussed above, courts have also sometimes held that where an agency statement does not "bind" an agency, it has no "future effect" and therefore cannot qualify as an APA "rule."95 This "binding effect" requirement has clear parallels to these cases holding that general policy statements are not rules because they do not bind the agency. However, these latter decisions do not explicitly ground this characterization of general policy statements in the text of the APA requiring rules to have "future effect."96 Accordingly, it is not clear how these two inquiries interrelate. Other cases have characterized general policy statements as APA rules, notwithstanding the fact that such a statement may not be legally binding in a future administrative proceeding.97

CRA Incorporation of APA Definition of "Rule"

The CRA incorporates the APA definition of "rule" by reference, and, consequently, should likely be read to incorporate judicial constructions of that definition.98 Thus, for example, although the CRA does not itself reference agency "orders," some courts have nonetheless imported the APA's distinction between rules and orders when interpreting the CRA.99 Accordingly, if an agency acts through an order or investigatory act, rather than a rule, the requirements of the CRA likely will not apply.100

During the 115th Congress, commentators have discussed using the CRA to revoke agencies' guidance documents,101 raising the question of which guidance documents qualify as CRA "rules."102 As a preliminary matter, it is important to note that "guidance document" is not a defined term under either the CRA or the APA.103 Even if an agency has characterized a statement as a guidance document rather than a rule, it still may qualify as a "rule" under the CRA.104 Instead, the relevant question is whether any agency statement labeled as guidance—which could include, for example, actions such as memoranda, letters, or agency bulletins—falls within the statutory definition of "rule," and if so, whether it is nonetheless exempt from the CRA under any of the exceptions to that definition.105

As discussed above, agency statements labeled as guidance are frequently exempt from the APA's notice-and-comment rulemaking procedures because they fall within the exceptions for interpretive rules or general policy statements.106 However, while the CRA adopts the APA's definition of rule, the CRA's exceptions to that definition are not identical to the APA's exemptions from its notice-and-comment procedures.107 Notably, the CRA does not exclude from its definition of rule either general policy statements or interpretative rules.108 Instead, the category of agency "rules" subject to the requirements of the CRA appears to encompass most "rules" that must go through the APA's notice-and-comment rulemaking procedures, along with some that do not.109 Consequently, agency guidance documents that are exempt from the APA's notice-and-comment procedural requirements may nonetheless be subject to the CRA, if they do not fall within one of the CRA's exceptions. But the effect of a disapproval resolution in such a case may be limited because such guidance documents generally lack legal effect in the first place.110

The post-enactment legislative history111 of the CRA indicates that the CRA was intended to encompass some agency statements that would not be subject to the APA's notice-and-comment rulemaking requirements. Following the enactment of the CRA in 1996, the law's sponsors inserted into the Congressional Record a statement112 in which they asserted that the law would cover a wide swath of agency actions:

The committees intend this chapter to be interpreted broadly with regard to the type and scope of rules that are subject to congressional review. The term "rule" in subsection 804(3) begins with the definition of a "rule" in subsection 551(4) and excludes three subsets of rules that are modeled on APA sections 551 and 553. This definition of a rule does not turn on whether a given agency must normally comply with the notice-and-comment provisions of the APA.... The definition of "rule" in subsection 551(4) covers a wide spectrum of activities.113

This statement suggests that Congress intended the CRA to reach a broad range of agency activities, including agency policy statements, interpretive rules, and certain rules of agency organization, despite the fact that those actions are not subject to the APA's requirements for notice and comment.114

However, as discussed above, there is some ambiguity regarding whether certain non-binding statements are rules at all. If general policy statements or other non-binding agency actions are not "rules" under the APA definition, then arguably, they are not rules under the CRA.115 But importantly, GAO has concluded that general policy statements should be considered "rules" under the CRA.116 As discussed in more detail below, GAO's resolution of this issue may stand as the last word on the matter, given the role that GAO has come to play in advising Congress on which agency actions are subject to the CRA.117

CRA Exceptions

Even if an agency action is a "rule" within the APA definition, it will not be subject to the CRA if it falls within one of the three exceptions to the CRA's definition of a "rule."118 The CRA incorporates the APA definition of rule,119 but exempts from that definition any rules "of particular applicability," rules "relating to agency management or personnel," and "any rule of agency organization, procedure, or practice that does not substantially affect the rights or obligations of non-agency parties."120 Some of these exemptions track language in the APA, and accordingly, cases interpreting those APA provisions may be useful to interpret the CRA exceptions.121 Additionally, the CRA does not "apply to rules that concern monetary policy proposed or implemented by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or the Federal Open Market Committee."122

The CRA also contains a partial exception for rules where an agency has, "for good cause," dispensed with notice-and-comment rulemaking procedures, as well as for rules related to "a regulatory program for a commercial, recreational, or subsistence activity related to hunting, fishing, or camping ."123 However, this section does not exempt rules from the CRA procedures entirely; it merely allows the agency to determine when the rule shall take effect, notwithstanding the CRA's requirements.124

Rules of Particular Applicability

While the APA's definition of "rule" includes agency statements "of general or particular applicability,"125 the CRA expressly exempts "any rule of particular applicability."126 Courts have said that this language refers to "legislative-type promulgations" that are "directed to" specifically named parties.127 In opinions from GAO analyzing whether various agency actions fall within the particular-applicability exception, GAO has stated that to be generally applicable, the CRA does not require a rule to "generally apply to the population as a whole."128 Instead, "all that is required is a finding" that a rule "has general applicability within its intended range, regardless of the magnitude of that range."129 For example, in one case, GAO concluded that an agency decision adopting and implementing a plan to counter decreased river flows in a certain river basin was not a matter of particular applicability.130 Although the decision applied to a specific geographic area, it would, in the view of GAO, nonetheless "have significant economic and environmental impact throughout several major watersheds in the nation's largest state."131

The CRA gives examples of some types of rules of particular applicability by specifying that this exemption includes any "rule that approves or prescribes for the future rates, wages, prices, services, or allowances therefor, corporate or financial structures, reorganizations, mergers, or acquisitions thereof, or accounting practices or disclosures bearing on any of the foregoing."132 Moreover, the post-enactment statement for the record written by the CRA's sponsors maintained that "IRS private letter rulings and Customs Service letter rulings are classic examples of rules of particular applicability."133 Under the APA, courts have also held, for example, that agency actions designating specific sites as covered by environmental laws are rules of "particular applicability."134

Rules Relating to Agency Management or Personnel

The second CRA exemption excludes "any rule relating to agency management or personnel."135 The APA contains a similar exemption from its general rulemaking requirements.136 Within the context of the APA, courts have concluded that this exemption covers agency statements such as policies for hiring employees.137 A rule will not fall within this exemption solely because it is "directed at government personnel."138 Instead, courts have viewed this APA exception to cover internal matters139 that do not substantially affect parties outside an agency.140

Notwithstanding the general presumption of courts that where Congress adopts language from another statute, it also intends to incorporate any settled judicial interpretations of that same language,141 it is unclear whether this substantial-effect requirement developed by courts in the context of the APA should be read into the CRA. The CRA's second exemption, for "any rule relating to agency management or personnel," does not expressly mention a rule's effect on third parties.142 By contrast, the CRA's third exemption does.143 This distinction in language could be read to mean that Congress intentionally chose to create a substantial-effect requirement for the third exception while omitting this limitation from the second one,144 so that the CRA's second exception excludes "any rule relating to agency management or personnel" regardless of its impact on third parties.145 On this view, this difference in phrasing would displace the ordinary presumption that Congress incorporates case law interpreting similar statutory provisions.146 This interpretation of the second exemption could mean that the CRA's exception for rules relating to agency management or personnel may be interpreted more broadly than the APA exception.

However, it is also possible that Congress chose not to include the substantial-effect requirement in this second exception because "prior judicial interpretation" of the identical phrases in the APA made such language unnecessary.147 Congress may have added a substantial-effect requirement to the third exception in order to settle some ambiguity in the cases interpreting the parallel provision of the APA, as described below.148

Rules of Agency Organization, Procedure, or Practice

Finally, the CRA exempts "any rule of agency organization, procedure, or practice that does not substantially affect the rights or obligations of non-agency parties."149 The APA also excludes "rules of agency organization, procedure, or practice" from notice-and-comment rulemaking procedures.150 Courts have held that this APA exception includes actions like agency decisions relating to how regulated entities must go about satisfying investigative requirements.151 Unlike the CRA, the APA does not explicitly limit this exception to those rules that do not "substantially affect the rights or obligations of non-agency parties."152 Nonetheless, because courts have read such a limitation into the APA exemption,153 the case law defining this requirement may be relevant to determine the scope of this CRA exemption.

However, in the cases interpreting this parallel APA exclusion, the impact of a rule on a third party is not the only factor courts use to distinguish between substantive rules, which are required to go through notice-and-comment procedures, and procedural rules, which are not.154 Instead, courts have engaged in two kinds of inquiries. The first is the "substantial impact test," which asks whether the agency action substantially impacts the regulated industry.155 However, the D.C. Circuit has noted that even rules best characterized as procedural measures may have a significant effect on regulated parties, and, accordingly, has held that "a rule with a 'substantial impact' upon the persons subject to it is not necessarily a substantive rule."156 Consequently, the D.C. Circuit has also asked whether the rule "encodes a substantive value judgment."157

Nonetheless, because the text of the CRA expressly excludes rules "of agency organization, procedure, or practice" that do not "substantially affect the rights or obligations of non-agency parties,"158 the CRA appears to mandate the use of something akin to the substantial impact test to determine whether a rule falls within this exception.159 In fact, one of the sponsors of the CRA emphasized prior to its passage that to determine whether a rule should be excluded under this provision, "the focus ... is not on the type of rule but on its effect on the rights or obligations of nonagency parties."160 He went on to say that the exclusion covered only rules "with a truly minor, incidental effect on nonagency parties."161 GAO has sometimes drawn on the APA case law described above in its own opinions analyzing whether various actions fall within the purview of the CRA.162 However, because the substantial-impact test and the substantive-value-judgment test were developed in the context of the APA to test whether rules "implicate the policy interests animating notice-and-comment rulemaking,"163 these judicially created tests might not be directly applicable to determine whether an agency statement is subject to the CRA.

CRA Requirement for Submission of Rules

The CRA requires that agencies submit actions that fall within the CRA's definition of a rule to both houses of Congress and to GAO before the actions may take effect. Thus, the submission requirement applies generally to rules that are promulgated through APA notice-and-comment procedures, as well as to other types of agency statements, as discussed above.

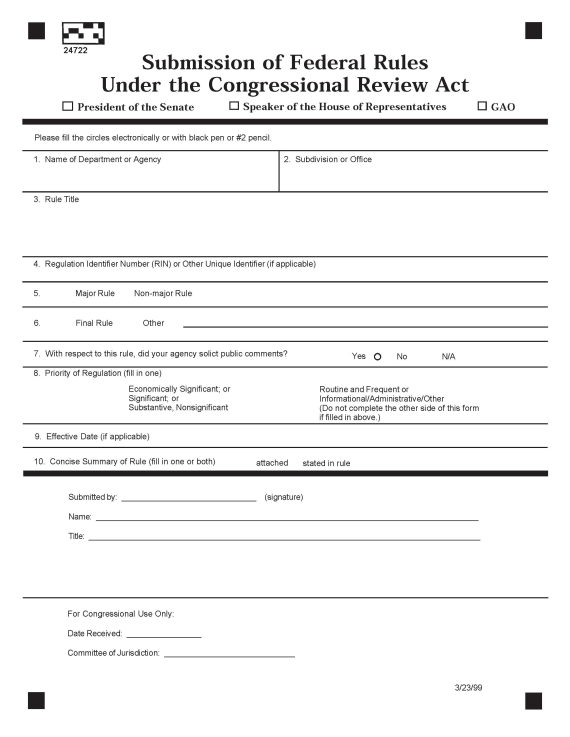

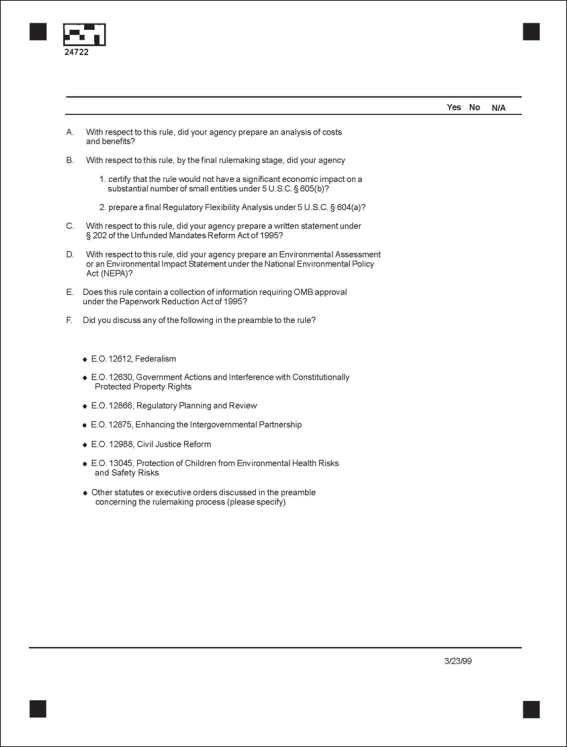

Specifically, Section 801(a)(1)(A) of the CRA requires the agency to submit a report containing a copy of the rule to each house of Congress and the Comptroller General; a concise general statement relating to the rule, including whether it is a major rule; and the proposed effective date of the rule.164 The agency is also required to submit additional information pertaining to any cost-benefit analysis the agency conducted, along with information on the agency's actions resulting from other regulatory impact analysis requirements, including the Regulatory Flexibility Act and the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act.165 For major rules, after receiving this information, GAO is then required to assess the agency's compliance with these additional informational requirements and include its assessment in the major rule report. The report is required to be submitted to the House and Senate committees of jurisdiction within 15 calendar days of the submission of the rule or its publication in the Federal Register, whichever date is later.166

The "report" that agencies are required to submit along with the rule, in practice, is a two-page form on which they provide the information required under Section 801(a)(1)(A) and, for major rules, most of the information required to be included in GAO's major rule report. In FY1999 appropriations legislation, Congress required the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to provide agencies with a standard form to use to meet this reporting requirement.167 OMB issued the form in March 1999 as part of a larger guidance to agencies on compliance with the CRA.168 A copy of the form is provided in Appendix A of this report.169

When final rules are submitted to Congress, notice of each chamber's receipt and referral appears in the respective House and Senate sections of the daily Congressional Record devoted to "Executive Communications." Notice of each chamber's receipt is also entered into a database that can be searched using the Legislative Information System of the U.S. Congress (LIS) or on Congress.gov.170 When the rule is submitted to GAO, a record of its receipt at GAO is noted in a database on GAO's website as well.171

Once the rule is received in Congress and published in the Federal Register, the time periods during which the CRA's expedited procedures are available begin, and Members can use the procedures to consider a resolution of disapproval. Thus, submission of rules to Congress under the CRA is critical because the receipt of the rule in Congress triggers the CRA's expedited procedures for introduction and consideration of a joint resolution disapproving the rule.172 In other words, if an agency fails to submit a rule to Congress, the House and Senate are unable to avail themselves of the special "fast track" procedures to consider a joint resolution striking down the rule.

Agency Compliance with Submission Requirement

Following enactment of the CRA in 1996, some Members of Congress and others raised concerns over agencies not submitting their rules on several occasions. At a hearing on the CRA in 1997, one year after its enactment, witnesses noted that agencies were not in full compliance with the submission requirement.173 It was also noted at the hearing, however, that it appeared agencies were seeking "in good faith" to comply with the statute.174 At a hearing in 1998 on implementation of the CRA, GAO's general counsel testified that agencies were often not sending their rules to GAO or Congress.175

Also in 1998, to further improve agency compliance with the CRA, Congress required OMB to issue guidance on certain provisions of the CRA, specifically including the submission requirement in 5 U.S.C. §801(a)(1).176 To meet this requirement, then-OMB Director Jacob J. Lew issued a memorandum for agencies in March 1999.177 The Lew memorandum provided information such as where agencies should send their rules in the House and Senate, including the addresses of the Office of the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House, the offices in each chamber that receive the rules; what information the agencies should include with the rule; and an explanation of what types of rules are required to be submitted.

Because agencies were initially inconsistent about fulfilling the submission requirement, GAO began to monitor agencies' compliance with the submission requirement by comparing the final rules that were published in the Federal Register with rules that were submitted to GAO.178 This was not a role that was required under the CRA; rather, GAO conducted these reviews voluntarily. As then-GAO general counsel Robert Murphy testified in 1998, GAO

conducted a review to determine whether all final rules covered by the Congressional Review Act and published in the Register were filed with the Congress and the GAO. We performed this review both to verify the accuracy of our own data base and to ascertain the degree of agency compliance with the statute. We were concerned that regulated entities may have been led to believe that rules published in the Federal Register were effective, when, in fact, they were not unless filed in accordance with the statute.179

After its review of agency compliance with the submission requirement, in November 1997, GAO submitted to OMB's Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) a list of the rules that had been published in the Federal Register but had not been submitted to GAO. According to GAO, OIRA distributed this list to affected agencies; GAO then followed up again with the agencies that had rules that remained un-submitted in February 1998. GAO stated in its March 1998 testimony that "In our view, OIRA should have played a more proactive role in assuring that the agencies were both aware of the statutory filing requirements and were complying with them."180

GAO continued to conduct similar reviews regularly, comparing the list of rules that agencies submitted to GAO against rules that were published in the Federal Register. Until 2012, GAO periodically sent letters to OIRA regarding rules that it had not received. In March 2012, GAO notified OIRA that, due to constraints on its resources, it would no longer be sending lists of rules not received. Instead, GAO decided to continue to track only major rules not received, not all final rules, as they had previously done.181

Submission of Notice-and-Comment Rules vs. Other Types of Documents

In general, although there have been exceptions noted by GAO, agencies appear to be fairly comprehensive in submitting rules to Congress and GAO when those rules have been promulgated through an APA rulemaking process. GAO's federal rules database lists thousands of such rules each year.182 In the case of rules that are not subject to notice-and-comment procedures, however, agencies often do not fulfill the submission requirement, and tracking compliance for these types of agency actions is more difficult.183

Although GAO has voluntarily tracked agency compliance with the submission requirement, its methodology for doing so did not result in a complete list of agency actions that should have been submitted. GAO's point of reference was to compare regulations that were published in the Federal Register against regulations it received pursuant to the CRA. Most rules that are required to be published in the Federal Register are indeed subject to the CRA, making this a potentially helpful method of identifying rules that were not submitted. However, many of the other agency actions that are not subject to notice-and-comment requirements are not generally published in the Federal Register and are also not submitted to GAO. Therefore, using this method, many rules that should have been submitted likely were undetected by GAO and thus not included in the lists of un-submitted rules it sent to OIRA and to the agencies. It is precisely this issue that led to Members requesting GAO's opinion on individual agency actions that were of specific interest to them and were not submitted to Congress (nor, in most cases, published in the Federal Register).184

The higher incidence of noncompliance with the CRA's submission requirement for agency actions that were conducted outside the notice-and-comment rulemaking process is likely due in large part to the practical difficulty of submitting the substantial number of agency statements that qualify as rules under the CRA. The CRA's submission requirement could potentially include a wide variety of items such as FAQs posted on agency websites, press releases, bulletins, information memoranda, and statements made by agency officials. In congressional testimony in 1997, one administrative law scholar argued that agencies "annually take tens of thousands of actions" that would fall under the CRA's definition of rule, and that

Were agencies to comply fully with [the CRA's] requirement that all these matters be filed with Congress as a condition of their effectiveness (as it appears, thus far, they are not doing), Congress and the GAO would be swamped with filings. Burying Congress in paper might even seem a useful means of diverting attention from larger, controversial matters; haystacks can be useful for concealing needles. No one believes many, if any, of these rules will be the subjects of resolutions of disapproval. Yet for them even simple accompanying documents to permit data analysis and tracking, such as GAO has been proposing, would impose significant aggregate costs, well beyond their possible benefit.185

In addition, it seems possible that many agencies are unaware of the breadth of the CRA's coverage. Reading through various agencies' responses to the GAO opinions discussed below suggests that many agencies appear to be aware that notice-and-comment rules are generally covered by the CRA, but they may be unaware that many other types of actions are covered. For example, in an opinion it issued in 2012 regarding an action taken by the Department of Health and Human Services, GAO stated that "We requested the views of the General Counsel of HHS on whether the July 12 Information Memorandum is a rule for purposes of the CRA by letter dated August 3, 2012. HHS responded on August 31, 2012, stating that the Information Memorandum was issued as a non-binding guidance document, and that HHS contends that guidance documents do not need to be submitted pursuant to the CRA."186 GAO concluded, however, "We cannot agree with HHS's conclusion that guidance documents are not rules for the purposes of the CRA and HHS cites no support for this position."187

GAO's Role in Determining Whether an Agency Action is Covered by the CRA

Because submission of rules is key to Congress's ability to use the CRA, if an agency does not submit a rule to Congress, this could potentially frustrate Congress's ability to review rules under the act. To avoid Congress being denied its opportunity for review of rules in this way, however, the Senate appears to have developed a practice that allows it to employ the CRA's review mechanism even when an agency does not submit a rule for review. That practice has involved seeking an opinion from GAO on whether an agency action should have been submitted under the CRA (i.e., whether the action is covered by the CRA's definition of "rule").

In several instances since the enactment of the CRA in 1996, Members of Congress sought an opinion from GAO as to whether certain agency actions were covered by the CRA, despite the agency not having undertaken notice-and-comment rulemaking or having submitted the action to Congress.188 GAO has issued 18 opinions of this type as of September 20, 2018. Generally, in these opinions, GAO has defined the term "rule" as used in the CRA expansively.189 In 11 of the 18 opinions, GAO opined that the agency statement in question was a rule under the CRA that should have been submitted to the House and Senate for review.190 These opinions are summarized below in this report and are listed in a table in Appendix B.

In recent years, the Senate has considered publication in the Congressional Record of a GAO opinion classifying an agency action as a rule as the trigger date for the initiation period to submit a disapproval resolution and for the action period during which such a joint resolution qualifies for expedited consideration in the Senate.191 Thus, the question of whether Congress may use the CRA's expedited parliamentary disapproval mechanism generally hinges upon the nature of GAO's opinion in such cases. By allowing the GAO opinion to serve as a substitute for the actual submission of a rule, the Senate can still avail itself of the CRA's expedited procedures to overturn rules.

Origin of GAO's Role

In responding to these requests from Members for opinions on whether certain agency actions are covered, GAO has played an important role in determining the applicability of the CRA. The specific role that GAO has played in this regard is not explicitly outlined in the statute, however. But a review of the history of the early implementation of the CRA, and a consideration of GAO's other activities under the CRA, suggests that the role GAO currently plays with regard to determining whether a specific agency action is a "rule" is linked to other activities GAO has engaged in regarding the CRA.

As has been noted, GAO's primary statutory requirement under the CRA is to provide a report to the committees of jurisdiction on each major rule, and to include in the report information about the agency's compliance with various steps of the rulemaking process for each major rule.192

For non-major rules, soon after the CRA was enacted, GAO voluntarily created an online database of rules submitted to it under the CRA, suggesting that it was willing to go beyond what was required of it by the statute to facilitate implementation.193 As GAO's general counsel explained in congressional testimony in 1998, "Although the law is silent as to GAO's role relating to the nonmajor rules, we believe that basic information about the rules should be collected in a manner that can be of use to Congress and the public. To do this, we have established a database that gathers basic information about the 15-20 rules we receive on the average each day."194 The database can be used to search for rules by elements such as the title, issuing agency, date of publication, type of rule (major or non-major), and effective date. The website also contains links to each of GAO's major rule reports.

Perhaps most notably, however, GAO's determination of whether agency actions are considered "rules" under the CRA appears to be closely linked to its monitoring of agency compliance with the submission requirement as discussed above. The question of whether an agency action is a rule under the CRA is also a question of whether it should be submitted; arguably, then, GAO is addressing a very similar question in its opinions on whether certain agency actions are covered as it was in its initial reports to OIRA on agency compliance with the submission requirement.

A discussion of GAO's role in a congressional hearing on the Tongass Land Management Plan in 1997 provides some evidence of the voluntary and, initially, ad hoc nature of GAO's role in this regard.195 One of the issues that was addressed at the hearing was whether the plan should be considered a rule under the CRA; GAO's general counsel was invited to testify at the hearing. Six days before the hearing, GAO issued its second opinion on the applicability of the CRA, in which it stated that the Tongass Land Management Plan should have been submitted as a rule under the CRA. Former Senator Larry Craig, who had requested the opinion, asked GAO's general counsel at the hearing about GAO's role:

It is our understanding of your testimony and our own reading of the Regulatory Flexibility Act that the General Accounting Office has been given the role of advising Congress and perhaps agencies on whether their policy decisions constitute rules. It is our understanding that the GAO's independent opinion is generally given considerable weight by the agencies. Is this also the GAO's understanding of its role?196

In response, GAO's general counsel, Robert Murphy, stated that the CRA

does not provide any identification of who is to decide what a rule is, unlike the issue of whether a rule is a major rule or not, which, as [OIRA Administrator] Ms. Katzen pointed out, has been assigned to her. So in that sense, I cannot say that GAO has a special role under the statute for making that determination. The decision, the opinion, that we issued last week on the question [of whether the Tongass Land Management Plan was a rule under the CRA] was done in our role as adviser to the Congress in response to the request of three chairmen of congressional committees.197

Thus, GAO acknowledged that its opinion was provided not pursuant to any specific provision of the statute, but in a more general, advisory capacity.

Congressional Response to GAO Opinions Since 1996

Although GAO has issued 18 opinions on the applicability of the CRA since 1996, Congress's response to those opinions has varied over time. Initially, the GAO opinions finding that the agency actions in question were rules under the CRA did not lead to the introduction of joint resolutions of disapproval—Members appear not to have introduced any joint resolutions of disapproval following a GAO opinion until 2008. In 2008, GAO issued an opinion stating that a letter from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to state health officials concerning the State Children's Health Insurance Program was a rule for the purposes of the CRA; in response, Senator John D. Rockefeller introduced S.J.Res. 44 to disapprove the guidance provided in the letter.198 According to a press release from the Committee on Finance at the time, however, the committee did not take further action on the resolution of disapproval because it had missed the window during which the action would have been required to be taken under the CRA to use its expedited procedures.199

The first time either chamber took action on a resolution of disapproval introduced following a GAO opinion was in 2012, when the House passed H.J.Res. 118 (112th Congress), a resolution of disapproval that would have overturned an information memorandum issued by the Department of Health and Human Services relating to the implementation of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. The first time the Senate took action on such a resolution of disapproval was on April 18, 2018, when it passed S.J.Res. 57, overturning guidance from the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB) pertaining to indirect auto lending and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act.200 The House passed S.J.Res. 57 on May 8, 2018, and the President signed it into law on May 21, 2018.

Consequences of GAO Opinions

Standing alone, a GAO opinion deciding whether an agency action is a "rule" covered by the CRA does not have legal effect.201 As discussed, GAO's role in determining whether actions are subject to the CRA is not provided for in the CRA,202 and its opinions are, in essence, advisory.203 The opinions do not have any immediate effect other than advising Congress as to whether GAO considers an agency action to meet the definition of rule under the CRA. As a matter of course, however, it appears that the Senate has chosen to treat the GAO opinions as dispositive on the issue. In several cases, individual Senators have stated that once a GAO opinion determining that an agency action is a rule is published in the Congressional Record, the time periods under the CRA commence and the agency action in question becomes subject to the CRA disapproval mechanism.204 The recent enactment of a joint resolution of disapproval that was introduced following a GAO opinion regarding a 2013 CFPB bulletin that had not been submitted by the agency indicates that Congress, in at least some cases, is willing to consider the GAO opinion as a substitute for the agency's submission of a rule to Congress.205

A CRA provision barring judicial review makes it unlikely that a GAO opinion or any other congressional determination stating that a rule is subject to the CRA would be subject to challenge in court.206 This provision states that "[n]o determination, finding, action, or omission under this chapter shall be subject to judicial review."207 Accordingly, most courts have refused to review any claims arguing that an agency action should have been submitted to Congress as a rule under the CRA.208 As a result, the question of whether an agency action is subject to the CRA and its fast-track procedures will likely be settled in the political arena rather than in the courts, and, if Congress continues to treat GAO opinions as determinative, those opinions likely will be the final word on the issue.209

The provision barring judicial review may mean that one other critical aspect of the CRA may be addressed outside of the courts and through GAO opinions: whether a rule has taken effect. As discussed previously, the CRA states that agencies must submit covered rules to Congress and the Comptroller General "before a rule can take effect,"210 suggesting that a rule may not become operative until the report required by the CRA is submitted to Congress. Indeed, the post-enactment statement inserted into the Congressional Record by the CRA's sponsors stated that, barring two exceptions listed in the CRA, "any covered rule not submitted to Congress and the Comptroller General will … not [take] effect until it is submitted pursuant to subsection 801(a)(1)(A)."211 However, courts have refused to adjudicate claims arguing that various rules are not in effect because an agency has failed to submit the rules to Congress.212 Accordingly, it is unlikely that a court would be willing to enforce this provision and declare that a rule lacks effect because it was not submitted to Congress.

If an agency has not submitted a disputed action to Congress, it is possible that this inaction was the result of the agency's view that the rule was not subject to the CRA. A GAO opinion stating that an agency action does constitute a rule, while not itself rendering a rule ineffective, may be the first indication to the agency that the rule did not "take effect" because the agency did not fulfill the CRA submission requirement.213 But in the context of agency rules that inherently lack legal effect, the determination that they lack "effect" under the CRA may not have much practical impact. In the context of rulemaking, to "take effect" usually means that something has become legally effective.214 As noted, however, the CRA encompasses some non-legislative rules that inherently lack legal effect.215 The fact that the CRA requires agencies to submit some agency statements that lack legal effect suggests that the term "effect," as used in the CRA's submission requirement, means something other than legal effect.216 While reviewing notice-and-comment rulemakings, some courts have held that the CRA suspends a rule's operation notwithstanding the fact that a rule may technically have become effective.217 With respect to rules such as general policy statements that generally lack legal force, however, even if an agency failed to comply with the CRA's submission requirement and erroneously regarded the rule as being operative, it is less likely that the operation of the statement had a discernible and independent effect on the agency's actions.218

Summary of GAO Opinions

This section briefly summarizes each of the 18 GAO opinions to date on whether certain agency actions were rules and, thus, were eligible for disapproval under the CRA. Where GAO appeared to consider one or more of the CRA exceptions to the definition of "rule" as fundamental to its analysis, the summaries identify which exception GAO focused on in its opinion. The opinions are listed in chronological order by the date on which GAO issued the opinion.

For a more concise summary of each of these opinions, see the table in Appendix B.

Department of Agriculture Memorandum Concerning the Emergency Salvage Timber Sale Program219

The Emergency Sale Timber Program was enacted as part of the Emergency Supplemental Appropriations and Rescissions Act of 1995.220 The program was intended to "increase the sales of salvage timber in order to remove diseased and damaged trees and improve the health and ecosystems of federally owned forests."221 On July 2, 1996, the Secretary of Agriculture sent a memorandum entitled "Revised Direction for Emergency Timber Salvage Sales Conducted Under Section 2001(b) of P.L. 104-19" to the Chief of the Forest Service, containing "clarifications in policy" for the program.

GAO concluded that the memorandum was a rule under the CRA because some of its contents "clearly are of general applicability and future effect in interpreting section 2001 of P.L. 104-19" and because, contrary to the argument the Department of Agriculture made to GAO when GAO requested its views on the matter, the memorandum "does not fall within the agency procedure or practice exclusion [in 5 U.S.C. §804(3)(C)]."222

U.S. Forest Service Tongass National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan223

On May 23, 2007, the Department of Agriculture's Forest Service issued the Tongass National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan, which "sets forth the management direction for the Tongass Forest and the desired condition of the Forest to be attained through Forest-wide multiple-use goals and objectives."224

GAO concluded that the plan was a rule under the CRA and was not excepted under 5 U.S.C. §804(3) because "decisions made in the Plan substantially affect non-agency parties and are, therefore, not 'agency procedures.'"225

American Heritage River Initiative, Created by Executive Order 13061226

President William Clinton signed Executive Order 13061 on September 11, 1997, announcing policies related to the American Heritage River Initiative (AHRI).227 The AHRI was intended to support American communities' efforts to restore and protect their rivers; the President was to designate, by proclamation, 10 rivers that would take part in the program.

GAO concluded that Executive Order 13061 was not a rule under the CRA because the President is not an "agency" for the purposes of the CRA (or, for that matter, under the APA).228 As such, actions taken by the President are not subject to the CRA.

Environmental Protection Agency "Interim Guidance for Investigating Title VI Administrative Complaints Challenging Permits"229

On February 5, 1998, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued its "Interim Guidance for Investigating Title VI Administrative Complaints Challenging Permits." According to EPA, the intent of the guidance was to update EPA's procedural and policy framework regarding complaints alleging discrimination in the environmental permitting context.

GAO concluded that "considered as a whole, the Interim Guidance clearly affects the rights of non-agency parties" and thus was a rule under the CRA and not exempt under 5 U.S.C. §804(3).230

Farm Credit Administration National Charter Initiative231

On May 3, 2000, the Farm Credit Administration (FCA) issued a booklet entitled "National Charters," and then the FCA published the booklet in the Federal Register on July 20, 2000.232 The booklet "provide[d] guidance on the national charter application process and the national charter territory. Specifically, the Booklet explain[ed] how a direct lender association can apply for a national charter; what the territory of a national charter will be; and what conditions the FCA will impose in connection with granting a national charter."233

GAO concluded that "we find that the Booklet, while labeled a statement of policy by the FCA, in actuality, meets the requirements of a legislative rule—which should have been issued using informal rulemaking procedures, including notice and comment."234 GAO then concluded that the booklet constituted a rule under the CRA and was not exempt under 5 U.S.C. §804(3) because the policies established in the booklet would have an effect on non-agency parties, and because statements made within the booklet clearly indicate that "the FCA recognizes the effect of the Booklet and national charters on other parties."235

Department of the Interior Record of Decision "Trinity River Mainstem Fishery Restoration"236

The Trinity River Record of Decision (ROD) was issued in December 2000 and documented the Department of the Interior's selection of the actions that it deemed necessary to "restore and maintain the anadromous fish in the Trinity River."237 The ROD identified the department's selected courses of action for addressing the decreased river flows in the Trinity River Basin.

GAO concluded that the ROD was a "rule" under the CRA because "its essential purpose is to set policy for the future," it was not a rule of agency procedure or practice under 5 U.S.C. §804(3), and "it will have broad effect on both rivers' ecosystems and potentially significant economic effect within the Sacramento and Trinity River basins."238

Department of Veterans Affairs Memorandum Regarding the VA's Marketing Activities to Enroll New Veterans in the VA Health Care System239

On July 18, 2002, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) issued a memorandum to network directors regarding the VA's marketing activities to enroll new veterans in the VA health care system. Specifically, the memorandum directed the network directors to no longer engage in trying to enroll new veterans through the use of certain types of activities, such as health fairs, veteran open houses, and enrollment displays at VSO meetings.

GAO concluded that the memorandum was not a rule under the CRA because it "is clearly excluded from the coverage of the CRA by one of the enumerated exceptions found in 5 U.S.C. §804(3)"—specifically, GAO considered the memorandum to be a statement of agency procedure or practice that did not affect the rights or obligations of non-agency parties.240 Rather, the memorandum governed internal agency procedures and did not affect the ability of veterans to enroll in the VA health care system.241

Department of Veterans Affairs Memorandum Terminating Vendee Loan Program242

On January 23, 2003, the VA issued a memorandum terminating the Vendee Loan Program, a program that allowed the VA to make loans for the sale of foreclosed VA-loan-guaranteed property. In the memorandum, which was addressed to all directors and loan guarantee officers, the VA Secretary announced that it would no longer finance the sale of acquired properties.

GAO concluded that the memorandum was not a rule under the CRA because it was a rule relating to agency management (i.e., excepted under 5 U.S.C. §804(3)(B)) or a rule of agency organization, procedure, or practice that does not substantially affect the rights or obligations of non-agency parties (i.e., excepted under 5 U.S.C. §804(3)(C)). GAO noted that "this is the type of management decision left to the discretion of the Secretary of VA in order to maintain the effective functioning and long-term stability of the program," and that "since the vendee loans were a purely discretionary method for VA to use to dispose of foreclosed properties, the change in the agency's 'organization' or 'practice' does not affect any party's right or obligation."243

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services Letter on the State Children's Health Insurance Program244

On August 17, 2007, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued a letter to state health officials concerning the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP).245 The letter "purports to clarify the statutory and regulatory requirements concerning prevention of crowd out for states wishing to provide SCHIP coverage to children with effective family incomes in excess of 250 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) and identifies a number of particular measures that these states should adopt."246

GAO concluded that the letter was a rule for the purposes of the CRA because it was a "statement of general applicability and future effect designed to implement, interpret, or prescribe law or policy with regard to the SCHIP program," and because GAO did "not believe that the August 17 letter comes within any of the exceptions to the definition of rule contained in the Review Act."247

Department of Health and Human Services Information Memorandum Concerning the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families Program248

On July 12, 2012, the Department of Health and Human Services' Administration for Children and Families issued an information memorandum concerning the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program.249 The memorandum notified states that HHS was willing to exercise waiver authority over some of the program's work requirements.

GAO concluded that the information memorandum was a rule for the purposes of the CRA because it was a "statement of general applicability and future effect, designed to implement, interpret, or prescribe law or policy with regard to TANF," and it did not fall within any of the three exceptions to the definition of a rule.250 As GAO stated, the memorandum applied to states and therefore was of general applicability, rather than particular applicability; it applied to the states and not agency management or personnel; and it established "the criteria by which states may apply for waivers from certain requirements of the TANF program. These criteria affect the obligations of the states, which are non-agency parties."251

Environmental Protection Agency Proposed Rule on Standards of Performance for Greenhouse Gas Emissions from New Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units252

On January 8, 2014, the Environmental Protection Agency issued a proposed rule entitled "Standards of Performance for Greenhouse Gas Emissions from New Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units."253 The proposed rule was intended to establish "standards for fossil fuel-fired electric steam generating units (utility boilers and Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) units) and for natural gas-fired stationary combustion turbines."254

GAO concluded that the proposed rule in question was not an action that was covered by the CRA, because the CRA was intended to apply only to final rules: "The issuance of a proposed rule is an interim step in the rulemaking process intended to satisfy APA's notice requirement, and, as such, is not a triggering event for CRA purposes."255 Furthermore, GAO stated "the precedent provided in our prior opinions underscores that proposed rules are not rules for CRA purposes, and GAO has no role with respect to them."256

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Federal Reserve Board, and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Interagency Guidance on Leveraged Lending257

On March 22, 2013, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, issued interagency guidance on leveraged lending.258 The guidance "outline[d] for agency-supervised institutions high-level principles related to safe-and-sound leveraged lending activities, including underwriting considerations, assessing and documenting enterprise value, risk management expectations for credits awaiting distribution, stress-testing expectations, pipeline portfolio management, and risk management expectations for exposures held by the institution."259

GAO concluded that the leveraged-lending guidance was a rule under the CRA because it was a general statement of policy that had future effect and because GAO could "readily conclude that the guidance does not fall within any of the three exceptions in the CRA."260 GAO's opinion, which was issued on October 19, 2017, was silent on the matter of the timing of its opinion relative to the guidance, which was issued in 2013.

U.S. Forest Service 2016 Amendment to the Tongass Land and Resource Management Plan261

On December 9, 2016, the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Forest Service approved an amendment to the Tongass Land and Resource Management Plan.262 The plan identified the uses that may occur in each area of the forest. The Forest Service is required under the National Forest Management Act of 1976 to update forest plans at least every 15 years and potentially more frequently.263

GAO concluded that the amendment to the plan was a rule under the CRA because the amendment "has a substantial impact on the regulated community such that it is a substantive rather than a procedural rule for purposes of CRA."264 As such, the plan could not be considered to fall within the exception in 5 U.S.C. §804(3)(C), despite the argument presented by USDA when GAO asked the agency its views on the matter.

Bureau of Land Management Eastern Interior Resource Management Plan265

On December 30, 2016, the Department of the Interior's Bureau of Land Management issued its resource management plan for four areas in Alaska: the Draanjik Planning Area, the Fortymile Planning Area, the Steese Planning Area, and the White Mountains Planning Area.266 Land management plans such as these are intended to provide specific information for the use of public lands and are required under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976.267

GAO concluded that the plan was a rule under the CRA because it was of general applicability, had future effect, and was designed to implement, interpret, or prescribe law or policy, and because it did not fit into any of the three exceptions. Of particular relevance appeared to be the exception in 5 U.S.C. §804(3): "Because the Eastern Interior Plan designates uses by nonagency parties that may take place in the four areas it governs, it is not a rule of agency organization, procedure or practice."268

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Bulletin on Indirect Auto Lending and Compliance with the Equal Credit Opportunity Act269

On March 21, 2013, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau issued a bulletin on "Indirect Auto Lending and Compliance with the Equal Credit Opportunity Act."270 The bulletin "provide[d] guidance about indirect auto lenders' compliance with the fair lending requirements of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) and its implementing regulation, Regulation B."271

GAO concluded that the bulletin was a rule under the CRA because it "is a statement of general applicability, since it applies to all indirect auto lenders; it has future effect; and it is designed to prescribe the Bureau's policy in enforcing fair lending laws," and because the bulletin "does not fall within any of the [CRA's] exceptions."272 GAO's opinion, which was issued on October 19, 2017, was silent on the matter of the timing of its opinion relative to the bulletin, which was issued in 2013.273

U.S. Agency for International Development Fact Sheet on Global Health Assistance and Revisions to Standard Provisions for U.S. Nongovernmental Organizations274

On January 23, 2017, President Donald J. Trump released a presidential memorandum establishing his Administration's policy on global health assistance funding, often referred to as the "Mexico City Policy."275 The policy prohibited assistance to foreign nongovernmental organizations and other entities that perform or promote abortion as a method of family planning. To implement this policy, the Department of State issued a fact sheet entitled "Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance" on May 15, 2017, and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) issued revisions to its "Standard Provisions for U.S. Nongovernmental Organizations" on March 2, 2017.276

GAO concluded that the two agency actions in question were not rules for the purposes of the CRA because, although the fact sheets were issued by federal agencies, they were merely implementing a decision of the President, under a statute that specifically granted broad policymaking authority to the President. GAO based this decision on a 1989 D.C. Circuit case, DKT Memorial Fund v. Agency for International Development, which held that agency actions implementing the decision of President Ronald Reagan to establish the Mexico City Policy were not reviewable under the APA.277 The court held that the disputed decision involved "not a rulemaking by an agency, but rather a policy-making at the highest level by the executive branch," concluding that it did not have authority under the APA "to review the wisdom of policy decisions of the President"278 where the relevant statute granted the President broad discretion in the area of foreign affairs.279 GAO determined that in accordance with this precedent, the agency actions implementing President Trump's policy decision were not subject to the CRA.280

Internal Revenue Service Statement on Health Care Reporting Requirements281

In guidance for the 2018 tax filing season, IRS announced on its website that it "would not accept electronically filed individual income tax returns where the taxpayer does not meet ACA reporting requirements, specifically to report full-year health coverage, claim a coverage exemption, or report a shared responsibility payment (known as 'silent returns')."282

GAO concluded that the agency statement was not a rule under the CRA because it "is a rule of agency procedure or practice that does not substantially affect taxpayers' rights or obligations," thus falling into the exception in 5 U.S.C. §804(3)(C).283 In effect, according to GAO, the "statement changes the timing of IRS compliance measures, but it does not change IRS's basis for assessing taxpayers' compliance with existing law—namely, the requirement to file a complete tax return and to meet ACA reporting requirements."284

Social Security Administration Hearings, Appeals, and Litigation Law Manual285

The Social Security Administration's (SSA) Hearings, Appeals, and Litigation Law Manual (HALLEX) describes how SSA will process and adjudicate claims for disability benefits under the Social Security Act. Two sections of the manual stated a policy under which an SSA adjudicator could not rely on information from the Internet, including from social media networks, in deciding a claim for benefits (with two exceptions).286

GAO concluded that these two sections of HALLEX were not rules under the CRA because they were merely "procedures that govern the use of evidence from the Internet during those proceedings" and they "do not impose new burdens on claimants or alter claimants' rights or obligations during the SSA appeal process."287 Thus, GAO concluded that "the HALLEX sections are procedural rules that meet the [5 U.S.C. §804(3)(C)] exception."288

Appendix A. Submission Form for Rules Under the CRA

|

|

|

Source: Form available on the White House website at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/information-regulatory-affairs/regulatory-matters/. |

Appendix B. Summary of GAO Opinions

Table 1. Government Accountability Office Opinions on Whether Certain Agency "Rules" Are Covered by the Congressional Review Act

As of September 20, 2018

|

Agency Action |

GAO Opinion Citation |

Date of Opinion |

Requested By |

GAO Determination |

|

Department of Agriculture memorandum concerning the Emergency Salvage Timber Sale Program |

B-274505 |

September 16, 1996 |

Senator Larry Craig |

Agency action is a rule under the CRA. |

|

U.S. Forest Service Tongass National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan |

B-275178 |

July 3, 1997 |

Senator Ted Stevens Senator Frank Murkowski Representative Don Young |

Agency action is a rule under the CRA. |

|

American Heritage River Initiative, created by Executive Order 13061 |

B-278224 |

November 10, 1997 |

Senator Conrad Burns |

Action is not a rule under the CRA because the President is not an agency under the CRA. |

|

Environmental Protection Agency "Interim Guidance for Investigating Title VI Administrative Complaints Challenging Permits" |

B-281575 |

January 20, 1999 |

Representative David McIntosh |

Agency action is a rule under the CRA. |

|

Farm Credit Administration national charter initiative |

B-286338 |

October 17, 2000 |

Representative James Leach |

Agency action is a rule under the CRA. |

|

Department of the Interior Record of Decision "Trinity River Mainstem Fishery Restoration" |

B-287557 |

May 14, 2001 |

Representative Doug Ose |

Agency action is a rule under the CRA. |

|

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) memorandum regarding the VA's marketing activities to enroll new veterans in the VA health care system |

B-291906 |

February 28, 2003 |

Representative Ted Strickland |

Agency action is not a rule under the CRA because it falls under the exception in 5 U.S.C. §804(3)(C). |

|

Department of Veterans Affairs memorandum terminating Vendee Loan Program |

B-292045 |

May 19, 2003 |

Representative Lane Evans |

Agency action is not a rule under the CRA because it falls under the exception in 5 U.S.C. §804(3)(B) or (C). |

|

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Letter on the State Children's Health Insurance Program |

B-316048 |

April 17, 2008 |

Senator John D. Rockefeller, IV Senator Olympia Snowe |

Agency action is a rule under the CRA. |

|

Department of Health and Human Services Information Memorandum concerning the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families Program |

B-323772 |

September 4, 2012 |