Introduction

International law consists of "rules and principles of general application dealing with the conduct of states and of international organizations and with their relations inter se, as well as with some of their relations with persons, whether natural or juridical."1 While the United States has long understood international legal commitments to be binding upon it both internationally and domestically since its inception,2 the role of international law in the U.S. legal system often implicates complex legal principles.3

The United States assumes international obligations most frequently when it makes agreements with other nations or international bodies that are intended to be legally binding upon the parties involved.4 Such legal agreements are made through treaty or executive agreement.5 The U.S. Constitution allocates primary responsibility for such agreements to the executive branch, but Congress also plays an essential role. First, in order for a treaty (but not an executive agreement) to become binding upon the United States, the Senate must provide its advice and consent to treaty ratification by a two-thirds majority.6 Secondly, Congress may authorize executive agreements.7 Thirdly, the provisions of many treaties and executive agreements may require implementing legislation in order to be judicial enforceable in U.S. courts.8

The effects of customary international law upon the United States are more ambiguous and difficult to decipher.9 While there is some Supreme Court jurisprudence finding that customary international law is incorporated into domestic law, this incorporation is only to the extent that "there is no treaty, and no controlling executive or legislative act or judicial decision" in conflict.10 This report provides an introduction to the role that international law and agreements play in the United States.

Forms of International Agreements

For purposes of U.S. law and practice, pacts11 between the United States and foreign nations may take the form of treaties, executive agreements, or nonlegal agreements, which involve the making of so-called "political commitments."12 In this regard, it is important to distinguish "treaty" in the context of international law, in which "treaty" and "international agreement" are synonymous terms for all binding agreements,13 and "treaty" in the context of domestic American law, in which "treaty" may more narrowly refer to a particular subcategory of binding international agreements that receive the Senate's advice and consent.14

|

Forms of International Pacts International Agreement: A blanket term used to refer to any agreement between the United States and a foreign state or body that is legally binding under international law.15 Treaty: An international agreement that receives the advice and consent of the Senate and is ratified by the President.16 Executive Agreement: An international agreement that is binding, but which the President enters into without receiving the advice and consent of the Senate.17 Nonlegal Agreement: A pact (or a provision within a pact) between the United States and a foreign entity that is not intended to be binding under international law, but may carry nonlegal incentives for compliance.18 |

Treaties

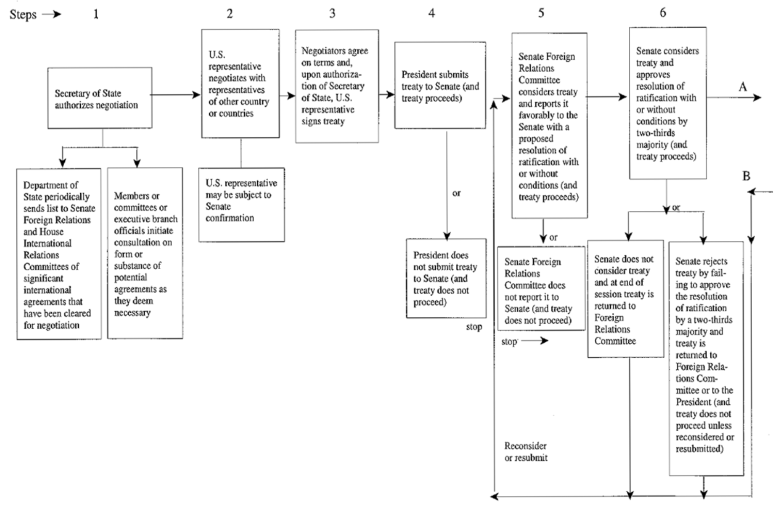

Under U.S. law, a treaty is an agreement negotiated and signed by a member of the executive branch that enters into force if it is approved by a two-thirds majority of the Senate and is subsequently ratified by the President.19 In modern practice, treaties generally require parties to exchange or deposit instruments of ratification in order for them to enter into force.20 A chart depicting the steps necessary for the United States to enter a treaty is in the Appendix.

The Treaty Clause—Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the Constitution—vests the power to make treaties in the President, acting with the "advice and consent" of the Senate. 21 Many scholars have concluded that the Framers intended "advice" and "consent" to be separate aspects of the treaty-making process.22 According to this interpretation, the "advice" element required the President to consult with the Senate during treaty negotiations before seeking the Senate's final "consent."23 President George Washington appears to have understood that the Senate had such a consultative role,24 but he and other early Presidents soon declined to seek the Senate's input during the negotiation process.25 In modern treaty-making practice, the executive branch generally assumes responsibility for negotiations, and the Supreme Court stated in dicta that the President's power to conduct treaty negotiations is exclusive.26

Although Presidents generally do not consult with the Senate during treaty negotiations, the Senate maintains an aspect of its "advice" function through its conditional consent authority.27 In considering a treaty, the Senate may condition its consent on reservations,28 declarations,29 understandings,30 and provisos31 concerning the treaty's application. Under established U.S. practice, the President cannot ratify a treaty unless the President accepts the Senate's conditions.32 If accepted by the President, these conditions may modify or define U.S. rights and obligations under the treaty.33 The Senate also may propose to amend the text of the treaty itself, and the other nations that are parties to the treaty must consent to the changes in order for them to take effect.34

Some international law scholars occasionally have criticized the Senate's use of certain reservations, understandings, and declarations (RUDs).35 For example, some critics have argued RUDs that conflict with the "object and purpose" of a treaty violate principles of international law.36 And scholars debate whether RUDs specifying that some or all provisions in a treaty are non-self-executing (meaning they require implementing legislation to be given judicially enforceable domestic legal effect) are constitutionally permissible.37

However much debate RUDs may have engendered among academics, they have produced little detailed discussion in courts. The Supreme Court has accepted the Senate's general authority to attach conditions to its advice and consent.38 And U.S. courts frequently interpret U.S. treaty obligations in light of any RUDs attached to the instrument of ratification.39 Where a treaty is ratified with a declaration that it is not self-executing, a court will not give its provisions judicially enforceable domestic legal effect.40

Executive Agreements

The great majority of international agreements that the United States enters into are not treaties, but executive agreements—agreements entered into by the executive branch that are not submitted to the Senate for its advice and consent.41 Federal law requires the executive branch to notify Congress upon entry of such an agreement.42 Executive agreements are not specifically discussed in the Constitution, but they nonetheless have been considered valid international compacts under Supreme Court jurisprudence and as a matter of historical practice.43 Although the United States has entered international compacts by way of executive agreement since the earliest days of the Republic,44 executive agreements have been employed much more frequently since the World War II era.45 Commentators estimate that more than 90% of international legal agreements concluded by the United States have taken the form of an executive agreement.46

Types of Executive Agreements

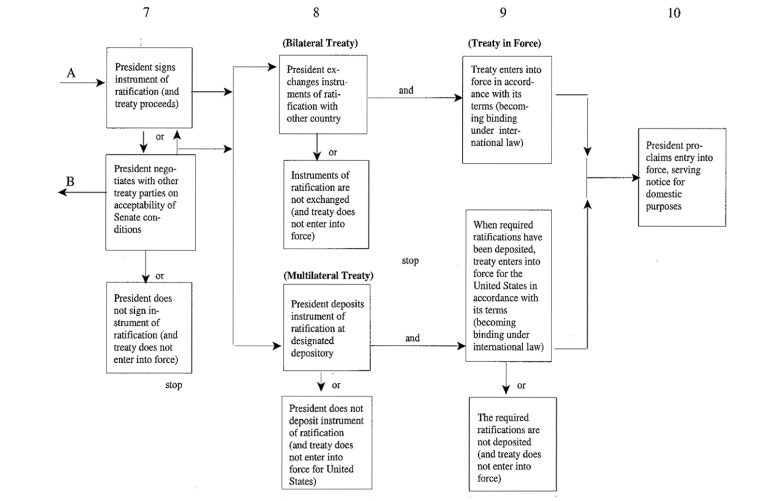

Executive agreements can be organized into three categories based on the source of the President's authority to conclude the agreement. In the case of congressional-executive agreements, the domestic authority is derived from an existing or subsequently enacted statute.47 The President also enters into executive agreements made pursuant to a treaty based upon authority created in prior Senate-approved, ratified treaties.48 In other cases, the President enters into sole executive agreements based upon a claim of independent presidential power in the Constitution.49 A chart describing the steps in the making of an executive agreement is in the Appendix.

The constitutionality of congressional-executive agreements is well-settled.50 Unlike in the case of treaties, where only the Senate plays a role in approving the agreement, both houses of Congress are involved in the authorizing process for congressional-executive agreements.51 Congressional authorization takes the form of a statute which must pass both houses of Congress. Historically, congressional-executive agreements have been made for a wide variety of topics, ranging from postal conventions to bilateral trade to military assistance.52 The North American Free Trade Agreement53 and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade54 are notable examples of congressional-executive agreements.

Agreements made pursuant to treaties are also well established as constitutional,55 though controversy occasionally arises as to whether a particular treaty actually authorizes the Executive to conclude an agreement in question.56 Because the Supremacy Clause includes treaties among the sources of the "supreme Law of the Land,"57 the power to enter into an agreement required or contemplated by the treaty lies within the President's executive function.58

Sole executive agreements rely on neither treaty nor congressional authority to provide their legal basis.59 The Constitution may confer limited authority upon the President to promulgate such agreements on the basis of his foreign affairs power.60 For example, the Supreme Court has recognized the power of the President to conclude sole executive agreements in the context of settling claims with foreign nations.61 If the President enters into an executive agreement addressing an area where he has clear, exclusive constitutional authority—such as an agreement to recognize a particular foreign government for diplomatic purposes—the agreement may be legally permissible regardless of congressional disagreement.62

If, however, the President enters into an agreement and his constitutional authority over the agreement's subject matter is unclear, a reviewing court may consider Congress's position in determining whether the agreement is legitimate.63 If Congress has given its implicit approval to the President entering the agreement, or is silent on the matter, it is more likely that the agreement will be deemed valid.64 When Congress opposes the agreement and the President's constitutional authority to enter the agreement is ambiguous, it is unclear if or when such an agreement would be given effect. Examples of sole executive agreements include the Litvinov Assignment, under which the Soviet Union purported to assign to the United States claims to American assets in Russia that had previously been nationalized by the Soviet Union, and the 1973 Vietnam Peace Agreement ending the United States' participation in the war in Vietnam.65

|

Standard Categories of Executive Agreements Congressional-Executive Agreement: An executive agreement for which domestic legal authority derives from a preexisting or subsequently enacted statute.66 Executive Agreement Made Pursuant to a Treaty: An executive agreement based on the President's authority in a treaty that was previously approved by the Senate.67 Sole Executive Agreement: An executive agreement based on the President's constitutional powers.68 |

Mixed Sources of Authority for Executive Agreements

Recently, some foreign relations scholars have argued that the international agreement-making practice has evolved such that some modern executive agreements no longer fit in the three generally recognized categories of executive agreements.69 These scholars contend that certain recent executive agreements are not premised on a defined source of presidential authority, such as an individual statute or stand-alone claim of constitutional authority.70 Nevertheless, advocates for a new form of executive agreement contend that identification of a specific authorizing statute or constitutional power is not necessary if the President already possesses the domestic authority to implement the executive agreement; the agreement requires no changes to domestic law; and Congress has not expressly opposed it.71 Opponents of this proposed new paradigm of executive agreement argue that it is not consistent with separation of powers principles, which they contend require the President's conclusion of international agreements be authorized either by the Constitution, a ratified treaty, or an act of Congress.72 Whether executive agreements with mixed or uncertain sources of authority become prominent may depend on future executive practice and the congressional responses.

Choosing Between a Treaty and an Executive Agreement

There has been long-standing scholarly debate over whether certain types of international agreements may only be entered as treaties, subject to the advice and consent of the Senate, or whether a congressional-executive agreement may always serve as a constitutionally permissible alternative to a treaty.73 A central legal question in this debate concerns whether the U.S. federal government, acting pursuant to a treaty, may regulate matters that could not be reached by a statute enacted by Congress pursuant to its enumerated powers under Article I of the Constitution.74 Adjudication of the propriety of congressional-executive agreements has been rare, in significant part because plaintiffs often cannot demonstrate that they have suffered a redressable injury giving them standing,75 or fail to make a justiciable claim.76 As a matter of historical practice, some types of international agreements have traditionally been entered as treaties in all or many instances, including compacts concerning mutual defense,77 extradition and mutual legal assistance,78 human rights,79 arms control and reduction,80 taxation,81 and the final resolution of boundary disputes.82

State Department regulations prescribing the process for coordination and approval of international agreements (commonly known as the "Circular 175 procedure")83 include criteria for determining whether an international agreement should take the form of a treaty or an executive agreement. Congressional preference is one of several factors (identified in the text box below) considered when determining the form that an international agreement should take. In addition, the Circular 175 procedure provides that "the utmost care" should be exercised to "avoid any invasion or compromise of the constitutional powers of the President, the Senate, and the Congress as a whole."84

In 1978, the Senate passed a resolution expressing its sense that the President seek the advice of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in determining whether an international agreement should be submitted as a treaty.85 The State Department subsequently modified the Circular 175 procedure to provide for consultation with appropriate congressional leaders and committees concerning significant international agreements.86 Consultations are to be held "as appropriate."87

|

Factors to Distinguish Treaties from Executive Agreements In determining whether a particular international agreement should be concluded as a treaty or an executive agreement, the State Department requires consideration to be given to the following factors: (1) The extent to which the agreement involves commitments or risks affecting the nation as a whole; (2) Whether the agreement is intended to affect state laws; (3) Whether the agreement can be given effect without the enactment of subsequent legislation by the Congress; (4) Past U.S. practice as to similar agreements; (5) The preference of the Congress as to a particular type of agreement; (6) The degree of formality desired for an agreement; (7) The proposed duration of the agreement, the need for prompt conclusion of an agreement, and the desirability of concluding a routine or short-term agreement; and (8) The general international practice as to similar agreements.88 |

Nonlegal Agreements

Not every pledge, assurance, or arrangement made between the United States and a foreign party constitutes a legally binding international agreement.89 In some cases, the United States makes "political commitments" with foreign States,90 also called "soft law" pacts.91 Although these pacts do not modify existing legal authorities or obligations, which remain controlling under both U.S. domestic and international law, such commitments may nonetheless carry significant moral and political weight.92 In some instances, a nonlegal agreement between States may serve as a stopgap measure until such time as the parties may conclude a permanent legal settlement.93 In other instances, a nonlegal agreement may itself be intended to have a lasting impact upon the parties' relationship.

The executive branch has long claimed the authority to enter such pacts on behalf of the United States without congressional authorization, asserting that the entering of political commitments by the Executive is not subject to the same constitutional constraints as the entering of legally binding international agreements.94 An example of a nonlegal agreement is the 1975 Helsinki Accords, a Cold War agreement signed by 35 nations, which contains provisions concerning territorial integrity, human rights, scientific and economic cooperation, peaceful settlement of disputes, and the implementation of confidence-building measures.95

Under State Department regulations, an international agreement is generally presumed to be legally binding in the absence of an express provision indicating its nonlegal nature.96 State Department regulations recognize that this presumption may be overcome when there is "clear evidence, in the negotiating history of the agreement or otherwise, that the parties intended the arrangement to be governed by another legal system."97 Other factors that may be relevant in determining whether an agreement is nonlegal in nature include the form of the agreement and the specificity of its provisions.98

The Executive's authority to enter such arrangements—particularly when those arrangements contemplate the possibility of U.S. military action—has been the subject of long-standing dispute between Congress and the Executive.99 In 1969, the Senate passed the National Commitments Resolution, stating the sense of the Senate that "a national commitment by the United States results only from affirmative action taken by the executive and legislative branches of the United States government by means of a treaty [or legislative enactment] . . . specifically providing for such commitment."100 The Resolution defined a "national commitment" as including "the use of the armed forces of the United States on foreign territory, or a promise to assist a foreign country . . . by the use of armed forces . . . either immediately or upon the happening of certain events."101

The National Commitments Resolution took the form of a sense of the Senate resolution, and accordingly had no legal effect.102 Although Congress has occasionally considered legislation that would bar the adoption of significant military commitments without congressional action,103 no such measure has been enacted.

Unlike in the case of legally binding international agreements, there is no statutory requirement that the executive branch notify Congress of every nonlegal agreement it enters on behalf of the United States.104 State Department regulations, including the Circular 175 procedure, also do not provide clear guidance for when or whether Congress will be consulted when determining whether to enter a nonlegal arrangement in lieu of a legally binding treaty or executive agreement.105 Congress normally exercises oversight over such non-binding arrangements through its appropriations power or via other statutory enactments, by which it may limit or condition actions the United States may take in furtherance of the arrangement.106

The Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act of 2015 is a notable exception where Congress opted to condition U.S. implementation of a political commitment upon congressional notification and an opportunity to review the compact.107 The act was passed during negotiations that culminated in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) between Iran, and six nations (the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, China, and Germany—collectively known as the P5+1).108 Under the terms of the plan of action, Iran pledged to refrain from taking certain activities related to the production of nuclear weapons, while the P5+1 agreed to ease or suspend sanctions that had been imposed in response to Iran's nuclear program.109 Because the JCPOA was not signed by any party and purported rely on a series of "voluntary measures," the Obama Administration considered it a political commitment that did not alter domestic or international legal obligations.110 Despite the JCPOA's nonbinding status, the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act provided a mechanism for congressional consideration of the JCPOA prior to the Executive being able to exercise any existing authority to relax sanctions to implement the agreement's terms.111

Effects of International Agreements on U.S. Law

The effects that international legal agreements entered into by the United States have upon U.S. domestic law are dependent upon the nature of the agreement; namely, whether the agreement (or a provision within an agreement) is self-executing or non-self-executing, and possibly whether the commitment was made pursuant to a treaty or an executive agreement.112

Self-Executing vs. Non-Self-Executing Agreements

Some provisions of international treaties or executive agreements are considered "self-executing," meaning that they have the force of domestic law without the need for subsequent congressional action.113 Provisions that are not considered self-executing are understood to require implementing legislation to provide U.S. agencies with legal authority to carry out the functions and obligations contemplated by the agreement or to make them enforceable in court.114 The Supreme Court has deemed a provision non-self-executing when the text manifests an intent that the provision not be directly enforceable in U.S. courts115 or when the Senate conditions its advice and consent on the understanding that the provision is non-self-executing.116

Although the Supreme Court has not addressed the issue directly, many courts and commentators agree that provisions in international agreements that would require the United States to exercise authority that the Constitution assigns to Congress exclusively must be deemed non-self-executing, and implementing legislation is required to give such provisions domestic legal effect.117 Lower courts have concluded that, because Congress controls the power of the purse, a treaty provision that requires expenditure of funds must be treated as non-self-executing.118 Other lower courts have suggested that treaty provisions that purport to create criminal liability119 or raise revenue120 must be deemed non-self-executing because those powers are the exclusive prerogative of Congress.

Until implementing legislation is enacted, existing domestic law concerning a matter covered by a non-self-executing provision remains unchanged and controlling law in the United States.121 While it is clear that non-self-executing provisions in international agreements do not displace existing state or federal law, there is significant scholarly debate regarding the distinction between self-executing and non-self-executing provisions, including the ability of U.S. courts to apply and enforce them.122 Some scholars argue that, although non-self-executing provisions lack a private right of action, litigants can still invoke non-self-executive provisions defensively in criminal proceedings or when another source for a cause of action is available.123 Other courts and commentators contend that non-self-executing provisions do not create any judicially enforceable rights, or that that they lack any status whatsoever in domestic law.124 At present, the precise status of non-self-executing treaties in domestic law remains unresolved.125

Despite the complexities of the self-execution doctrine in domestic, treaties and other international agreements operate in dual international and domestic law contexts.126 In the international context, international agreements traditionally constitute binding compacts between sovereign nations, and they create rights and obligations that nations owe to one another under international law.127 But international law generally allows each individual nation to decide how to implement its treaty commitments into its own domestic legal system.128 The self-execution doctrine concerns how a treaty provision is implemented in U.S. domestic law, but it does not affect the United States' obligation to comply with the provision under international law.129 When a treaty is ratified or an executive agreement concluded, the United States acquires obligations under international regardless of self-execution, and it may be in default of the obligations unless implementing legislation is enacted.130

Congressional Implementation of International Agreements

When an international agreement requires implementing legislation or appropriation of funds to carry out the United States' obligations, the task of providing that legislation falls to Congress.131 In the early years of constitutional practice, debate arose over whether Congress was obligated—rather than simply empowered—to enact legislation implementing non-self-executing provisions into domestic law.132 But the issue has not been resolved in any definitive way as it has not been addressed in a judicial opinion and continues to be the subject of debate occasionally.133

By contrast, the Supreme Court has addressed the scope of Congress's power to enact legislation implementing non-self-executing treaty provisions. In a 1920 case, Missouri v. Holland,134 the Supreme Court addressed a constitutional challenge to a federal statute that implemented a treaty prohibiting the killing, capturing, or selling of certain birds that traveled between the United States and Canada.135 In the preceding decade, two federal district courts had held that similar statutes enacted prior to the treaty violated the Tenth Amendment because they infringed on the reserved powers of the states to control natural resources within their borders.136 But the Holland Court concluded that, even if those district court decisions were correct, their reasoning no longer applied once the United States concluded a valid migratory bird treaty.137 In an opinion authored by Justice Holmes, the Holland Court concluded that the treaty power can be used to regulate matters that the Tenth Amendment otherwise might reserve to the states.138 And if the treaty itself is constitutional, the Holland Court held, Congress has the power under the Necessary and Proper Clause139 to enact legislation implementing the treaty into the domestic law of the United States without restraint by the Tenth Amendment.140

Commentators and jurists have called some aspects of the Justice Holmes's reasoning in Holland into question,141 and some scholars have argued that the opinion does not apply to executive agreements.142 But the Supreme Court has not overturned Holland's holding related to Congress's power to implement treaties.143 Nevertheless, principles of federalism embodied in the Tenth Amendment continue to impact constitutional challenges to U.S. treaties and their implementing statutes, including in the 2014 Supreme Court decision, Bond v. United States.144

Bond concerned a criminal prosecution arising from a case of "romantic jealously" when a jilted spouse spread toxic chemicals on the mailbox of a woman with whom her husband had an affair.145 Although the victim only suffered a "minor thumb burn," the United States brought criminal charges under the Chemical Weapons Convention Act of 1998—a federal statute that implemented a multilateral treaty prohibiting the use of chemical weapons.146 The accused asserted that the Tenth Amendment reserved the power to prosecute her "purely local" crime to the states, and she asked the Court to overturn or limit Holland's holding on the relationship between treaties and the Tenth Amendment.147

Although a majority in Bond declined to revisit Holland's interpretation of the Tenth Amendment,148 the Bond Court ruled in the accused's favor based on principles of statutory interpretation.149 When construing a statute interpreting a treaty, Bond explained, "it is appropriate to refer to basic principles of federalism embodied in the Constitution to resolve ambiguity . . . ."150 Applying these principles through a presumption that Congress did not intend to intrude on areas of traditional state authority, the Bond Court concluded that the Chemical Weapons Convention Act did not apply to the jilted spouse's actions.151 In other words, the majority in Bond did not disturb Holland's conclusion that the Tenth Amendment does not limit Congress's power to enact legislation implementing treaties, but Bond did hold that principles of federalism reflected in the Tenth Amendment may dictate how courts interpret such implementing statutes.152

Conflict with Existing Laws

Sometimes, a treaty or executive agreement will conflict with one of the three main tiers of domestic law—U.S. state law, federal law, or the Constitution. For domestic purposes, a ratified, self-executing treaty is the law of the land equal to federal law153 and superior to U.S. state law,154 but inferior to the Constitution.155 A self-executing executive agreement is likely superior to U.S. state law,156 but sole executive agreements may be inferior to conflicting federal law in certain circumstances (congressional-executive agreements or executive agreements pursuant to treaties are equivalent to federal law),157 and all executive agreements are inferior to the Constitution.158 In cases where ratified treaties or certain executive agreements are equivalent to federal law, the "last-in-time" rule establishes that a more recent federal statute will prevail over an earlier, inconsistent international agreement, while a more recent self-executing agreement will prevail over an earlier, inconsistent federal statute.159

Treaties and executive agreements that are not self-executing, on the other hand, have generally been understood not to displace existing state or federal law in the absence of implementing legislation.160 "The responsibility for transforming an international obligation arising from a non-self-executing treaty into domestic law falls to Congress."161 Accordingly, it appears unlikely that a non-self-executing agreement could be converted into judicially enforceable domestic law absent legislative action through the bicameral process.162

Interpreting International Agreements

When analyzing an international agreement for purposes of its domestic application, U.S. courts have final authority to interpret the agreement's meaning.163 As a general matter, the Supreme Court has stated that its goal in interpreting an agreement is to discern the intent of the nations that are parties to it.164 The interpretation process begins by examining "the text of the [agreement] and the context in which the written words are used."165 When an agreement provides that it is to be concluded in multiple languages, the Supreme Court has analyzed foreign language versions to assist in understanding the agreement's terms.166 The Court also considers the broader "object and purpose" of an international agreement.167 In some cases, the Supreme Court has examined extratextual materials, such as drafting history,168 the views of other state parties,169 and the post-ratification practices of other nations.170 But the Court has cautioned that consulting sources outside the agreement's text may not be appropriate when the text is unambiguous.171

The executive branch frequently is responsible for interpreting international agreements outside the context of domestic litigation.172 While the Supreme Court has final authority to interpret an agreement for purposes of applying it as domestic law in the United States, some questions of interpretation may involve exercise of presidential discretion or otherwise may be deemed "political questions" more appropriately resolved in the political branches. In Charlton v. Kelly, for example, the Supreme Court declined to decide whether Italy violated its extradition treaty with the United States, reasoning that, even if a violation occurred, the President "elected to waive any right" to respond to the breach by voiding the treaty.173 Moreover, the executive branch often is well-positioned to interpret an agreement's terms given its leading role in negotiating agreements and its understanding of other nations' post-ratification practices.174 Thus, even when a question of interpretation is to be resolved by the judicial branch, the Supreme Court has stated that the executive branch's views are entitled to "great weight"175—although the Court has not adopted the executive branch's interpretation in every case.176

Congress also possesses power to interpret international agreements by virtue of its power to pass implementing or other related legislation.177 And because the Constitution expressly divides the treaty-making power between the Senate and the President, the Supreme Court has examined sources that reflect these entities' shared understanding of a treaty at the time of ratification.178 The Senate's ability to influence treaty interpretation directly, however, may be limited to its role in the advice and consent process.179 The Senate may, and frequently does, condition its consent on a requirement that the United States interpret a treaty in a particular fashion.180 But after the Senate provides its consent and the President ratifies a treaty, resolutions passed by the Senate that purport to interpret the treaty are "without legal significance" according to the Supreme Court.181

Withdrawal from International Agreements

The Constitution sets forth a definite procedure whereby the President has the power to make treaties with the advice and consent of the Senate, 182 but it is silent as to how to terminate them.183 Although the Supreme Court has recognized directly the President's power to conclude certain executive agreements,184 it has not addressed presidential power to terminate those agreements. The following section discusses historical practice and jurisprudence related to the withdrawal from and termination of international agreements.185

Withdrawal from Executive Agreements and Political Commitments

In the case of executive agreements, it appears generally accepted that, when the President has independent authority to enter into an executive agreement, the President may also independently terminate the agreement without congressional or senatorial approval. 186 Thus, observers appear to agree that, when the Constitution affords the President authority to enter into sole executive agreements, the President also may unilaterally terminate those agreements.187 This same principle would apply to political commitments: to the extent the President has the authority to make nonbinding commitments without the assent of the Senate or Congress, the President also may withdraw unilaterally from those commitments.188

For congressional-executive agreements and executive agreements made pursuant to treaties, the mode of termination may be dictated by the underlying treaty or statute on which the agreement is based.189 For example, in the case of executive agreements made pursuant to a treaty, the Senate may condition its consent to the underlying treaty on a requirement that the President not enter into or terminate executive agreements under the authority of the treaty without senatorial or congressional approval.190 And for congressional-executive agreements, Congress may dictate how termination occurs in the statute authorizing or implementing the agreement.191

Congress also has asserted the authority to direct the President to terminate congressional-executive agreements. For example, in the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, which was passed over President Reagan's veto, Congress instructed the Secretary of State to terminate an air services agreement with South Africa.192 And in the Trade Agreements Extension Act of 1951, Congress directed the President to "take such action as is necessary to suspend, withdraw or prevent the application of" trade concessions contained in prior trade agreements regulating imports from the Soviet Union and "any nation or area dominated or controlled by the foreign government or foreign organization controlling the world Communist movement."193

Presidents also have asserted the authority to withdraw unilaterally from congressional-executive agreements, but there is an emerging scholarly debate over the extent to which the Constitution permits the President to act without the approval of the legislative branch in such circumstances. Some scholars assert that the President has the power to withdraw unilaterally from congressional-executive agreements, although he may not terminate the domestic effect of an agreements implementing legislation.194 But others argue that Congress must approve termination of executive agreements that implicate exclusive congressional powers, such as the power over international commerce, and that received congressional approval after they were concluded by the executive branch.195 Although this debate is still developing, unilateral termination of congressional-executive agreements by the President has not been the subject of a high volume of litigation, and prior studies have concluded that such termination has not generated large-scale opposition from the legislative branch.196

Withdrawal from Treaties

Unlike the process of terminating executive agreements, which historically has not generated extensive opposition from Congress, the constitutional requirements for the termination of Senate-approved, ratified treaties have been the subject of occasional debate between the legislative and executive branches. Some commentators have argued that the termination of treaties is analogous to the termination of federal statutes.197 Because domestic statutes may be terminated only through the same process in which they were enacted198—i.e., through a majority vote in both houses and with the signature of the President or a veto override—these commentators contend that treaties likewise must be terminated through a procedure that resembles their making and that includes the legislative branch.199

On the other hand, treaties do not share every feature of federal statutes. Whereas statutes can be enacted over the president's veto, treaties can never be concluded without the Senate's advice and consent. Moreover, whereas an enacted federal statute can only be rescinded by a subsequent act of Congress, some argue that, just as the President has some unilateral authority to remove executive officers who were appointed with senatorial consent, the President may unilaterally terminate treaties made with the Senate's advice and consent.200

The United States terminated a treaty under the Constitution for the first time in 1798. On the eve of possible hostilities with France, Congress passed, and President Adams signed, legislation stating that four U.S. treaties with France "shall not henceforth be regarded as legally obligatory on the government or citizens of the United States."201 Thomas Jefferson referred to the episode as support for the notion that only an "act of the legislature" can terminate a treaty.202 But commentators since have come to view the 1798 statute as a historical anomaly because it is the only instance in which Congress purported to terminate a treaty directly through legislation without relying on the President to provide a notice of termination to the foreign government.203 Moreover, because the 1798 statute was part of a series of congressional measures authorizing limited hostilities against the French Republic, some view the statute as an exercise of Congress's war powers rather than precedent for a permanent congressional power to terminate treaties.204

During the 19th century, government practice treated the power to terminate treaties as shared between the legislative and executive branches.205 Congress often authorized206 or instructed207 the President to provide notice of treaty termination to foreign governments during this time. On rare occasions, the Senate alone passed a resolution authorizing the President to terminate a treaty.208 Presidents regularly complied with the legislative branch's authorization or direction.209 On other occasions, Congress or the Senate approved the President's termination after-the-fact, when the executive branch had already provided notice of termination to the foreign government.210

At the turn of the 20th century, government practice began to change, and a new form of treaty termination emerged: unilateral termination by the President without approval by the legislative branch. During the Franklin Roosevelt Administration and World War II, unilateral presidential termination increased markedly.211 Although Congress occasionally enacted legislation authorizing or instructing the President to terminate treaties during the 20th century,212 unilateral presidential termination became the norm.213

The president's exercise of treaty termination authority did not generate opposition from the legislative branch in most cases, but there have been occasions in which Members of Congress sought to block unilateral presidential action. In 1978, a group of Members filed suit in Goldwater v. Carter214 seeking to prevent President Carter from terminating a mutual defense treaty with the government of Taiwan215 as part of the United States' recognition of the government of mainland China.216 A divided Supreme Court ultimately ruled that the litigation should be dismissed, but it did so without reaching the merits of the constitutional question and with no majority opinion.217 Citing a lack of clear guidance in the Constitution's text and a reluctance "to settle a dispute between coequal branches of our Government each of which has resources available to protect and assert its interests[,]" four Justices concluded that the case presented a nonjusticiable political question.218 This four-Justice opinion, written by Justice Rehnquist, has proven influential since Goldwater, and federal district courts have invoked the political question doctrine as a basis to dismiss challenges to unilateral treaty terminations by President Reagan219 and President George W. Bush.220

Customary International Law

Customary international law is defined as resulting from "a general and consistent practice of States followed by them from a sense of legal obligation."221 This means that all, or nearly all, nations consistently follow the practice in question and they must do so because they believe themselves legally bound, a concept often referred to as opinio juris sive necitatis (opinio juris).222 If nations generally follow a particular practice but do not feel bound by it, it does not constitute customary international law.223 Further, there are ways for nations to avoid being subject to customary international law. First, a nation that is a persistent objector to a particular requirement of customary international law is exempt from it.224 Second, under American law, the United States can exempt itself from customary international law requirements by passing a contradictory statute under the "last-in-time" rule.225 As a result, the impact of customary international law that conflicts with other domestic law appears limited.

In examining nations' behavior to determine whether opinio juris is present, courts might look to a variety of sources, including, inter alia, relevant treaties, unanimous or near-unanimous declarations by the United Nations General Assembly concerning international law,226 and whether noncompliance with an espoused universal rule is treated as a breach of that rule.227 Uncertainties and debate frequently arise concerning how customary international law is defined and how firmly established a particular norm must be in order to become binding.228

Some particularly prevalent rules of customary international law can acquire the status of jus cogens norms—peremptory rules which permit no derogation, such as the international prohibition against slavery or genocide.229 For a particular area of customary international law to constitute a jus cogens norm, State practice must be extensive and virtually uniform.230

Relationship Between Customary International Law and Domestic Law

For much of the history of the United States, courts231 and U.S. officials232 understood customary international law to be binding U.S. domestic law in the absence of a controlling executive or legislative act. By 1900, the Supreme Court stated in The Paquete Habana that international law is "part of our law[.]"233 Although this description seems straightforward, twentieth century developments complicate the relationship between customary international law and domestic law.

In a landmark 1938 decision, Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins, the Supreme Court rejected the then-longstanding notion that there was a "transcendental body of law" known as the general common law, which federal courts are permitted to identify and describe in the absence of a conflicting statute.234 Erie held that the "law in the sense in which courts speak of it today does not exist without some definite authority behind it" in the form of a state or federal statute or constitutional provision.235 Some jurists and commentators have argued that, because judicial application of customary international law requires courts to rely on the same processes used in discerning and applying the general common law, Erie should be interpreted to foreclose application of customary international law in U.S. courts.236 Many commentators, however, disagree with this view.237 Although the Supreme Court has not passed directly on the issue, in 1964, it discussed with approval a law review article in which then-professor and later judge of the International Court of Justice Philip C. Jessup argued that it would be "unsound" and "unwise" to interpret Erie to bar federal courts' application of customary international law.238 And in a 2004 case, the High Court rejected the view that federal courts have lost "all capacity" to recognize enforceable customary international norms as a result of Erie.239 Consequently, at present, the precise status of customary international law in the U.S. legal system remains the subject of debate. 240

While there is some uncertainty concerning the customary international law's role in domestic law, the debate has largely focused on circumstances in which customary international law does not conflict with an existing federal statute. When a federal statute does conflict with customary international law, lower courts consistently have concluded that the statute prevails.241 And there do not appear to be any cases in which a court has struck down a federal statute on the ground that it violates customary international law.242 Further, the Supreme Court's pre-Erie jurisprudence could be read to support the view that federal statutes prevail over customary international law. In The Paquete Habana, the Court explained that customary international law may be incorporated into domestic law, but only to the extent that "there is no treaty, and no controlling executive or legislative act or judicial decision" in conflict.243

While it appears that federal statutes will generally prevail over conflicting custom-based international law, customary international law can potentially affect how courts construe domestic law. Under the canon of statutory construction known as the Charming Betsy canon, when two constructions of an ambiguous statute are possible, one of which is consistent with international legal obligations and one of which is not, courts will often construe the statute so as not to violate international law, presuming such a statutory reading is reasonable.244

Statutory Incorporation of Customary International and the Alien Tort Statute

Customary international law plays a direct role in the U.S. legal system when Congress incorporates it into federal law via legislation. Some statutes expressly reference customary international law, and thereby permit courts to interpret its requirements and contours.245 For example, federal law prohibits "the crime of piracy as defined by the law of nations . . . ."246 And the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act removes the protections from lawsuits afforded to foreign sovereign nations in certain classes of cases in which property rights are "taken in violation of international law . . . ."247

Perhaps the clearest example of U.S. law incorporating customary international law is the Alien Tort Statute (ATS).248 The ATS originated as part of the Judiciary Act of 1789, and establishes federal court jurisdiction over tort claims brought by aliens for violations of either a treaty of the United States or "the law of nations."249 Until 1980, this statute was rarely used, but in Filártiga v. Pena-Irala, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit relied upon it to award a civil judgment against a former Paraguayan police official who had allegedly tortured the plaintiffs while still in Paraguay. In doing so, the Filártiga Court concluded that torture constitutes a violation of the law of nations and gives rise to a cognizable claim under the ATS.250

Filártiga was a highly influential decision that caused the ATS to "skyrocket" into prominence as a vehicle for asserting civil claims in U.S. federal courts for human rights violations even when the events underlying the claims occurred outside the United States.251 But the expansion of the claims grounded in the ATS was not long-lived. Beginning with a 2004 decision, Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain, the Supreme Court began to place outer limits on the statute's application.252 Sosa held that not all violations of international norms are actionable under the ATS—only those that "rest on a norm of international character accepted by the civilized world" and are defined with sufficient clarity and particularity.253 And even when a claim meets these standards, Sosa explained that federal courts must exercise "great caution" before deeming a claim actionable.254

Nine years later, in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co., the Supreme Court further limited the ATS's reach by holding that courts should apply the canon of construction known as the presumption against extraterritoriality to the statute.255 Under Kiobel, foreign plaintiffs cannot sue foreign defendants in ATS suits when the relevant conduct occurred overseas.256 And in Jesner v. Arab Bank, PLC, a 2018 decision, the High Court concluded that foreign corporations are not subject to the liability under the ATS.257 Although the ATS remains a clear example of a U.S. statute incorporating customary international law, the Supreme Court's narrowing of ATS jurisdiction in Sosa, Kiobel, and Jesner has caused some commentators to question its continued relevance.258

Conclusion

Although the United States has long understood international legal commitments to be binding both internationally and domestically, the relationship between international law and the U.S. legal system implicates complex legal dynamics. In some areas, courts have established settled rules. For example, courts clearly have recognized that the Constitution permits the United States to make binding international commitments through both treaties and executive agreements.259 And the Supreme Court has held that only self-executing international agreements have the status of judicially enforceable domestic law.260 But other issues concerning the status of international law in the U.S. legal system have never been fully resolved.261 The scope of presidential power to make executive agreements, the role of non-self-executing agreements and customary international law, and the division of power to withdraw from international agreements—like many international-law-related issues—have long been the subject of debate. Because the legislative branch possesses significant powers to shape and define the United States' international obligations, Congress is likely to continue to play a critical role in dictating the outcome of these debates in the future.

Appendix. Steps in the Making of a Treaty and in the Making of an Executive Agreement

|

|

|

Source: Reprinted from Treaties and Other International Agreements: The Role of the United States Senate, A Study Prepared for the Senate Comm. on Foreign Relations, S. Rep. 106-9, at 8-9 (Comm. Print 2001). |

|

|

Source: Reprinted from Treaties and Other International Agreements: The Role of the United States Senate, A Study Prepared for the Senate Comm. on Foreign Relations, S. Rep. 106-9, at 8-9 (Comm. Print 2001). |