Introduction

The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) Act of 19651 was enacted to help preserve, develop, and ensure access to outdoor recreation resources. A main goal of the law was to facilitate participation in recreation and strengthen the "health and vitality" of U.S. citizens. The law sought to accomplish this goal by "providing funds" for federal land acquisition and for federal assistance to states for outdoor recreation, including for recreation planning, acquisition of lands and waters, and development of recreation facilities. The law created the Land and Water Conservation Fund in the Treasury as a funding source to implement its outdoor recreation goals.

Currently, the fund receives $900 million annually under the LWCF Act, but these credited monies cannot be spent unless appropriated by Congress. The level of annual appropriations has varied widely since the origin of the fund in 1965. This authority for the fund to accrue $900 million annually is scheduled to expire on September 30, 2018.2 While the LWCF Act initially did not specify the authorized level of funding, the law has been amended several times to specify and provide increasing levels of authorizations. The authorization was raised to $900 million for FY1978, and has remained at this level. The fund accrues revenues of $900 million annually from three specific sources, including the federal motorboat fuel tax and surplus property sales. The fund accumulates the majority of its revenues from oil and gas leases on the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS).

The LWCF receives additional money (beyond the $900 million) under the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act of 2006 (GOMESA),3 and these appropriations are mandatory. The authority for the LWCF to accrue revenues under GOMESA does not have an expiration date. Under GOMESA, the fund accrues revenue from certain OCS leasing, and these monies can be used only for grants to states for outdoor recreation. These mandatory appropriations had been relatively small through FY2017, but are estimated to have increased substantially in FY2018 and to remain relatively high at least over the next decade.

Of current debate is whether to reauthorize provisions of the LWCF Act beyond September 30, 2018, and alter the operation of the fund. Alterations under discussion include whether to permanently reauthorize the LWCF Act, make all or a portion of the appropriations under that law mandatory (rather than discretionary), direct monies to be used for particular purposes provided for in the LWCF Act, or amend the law to authorize the fund to be used for different purposes. These questions are being debated by authorizing committees and during consideration of the annual Interior appropriations legislation.

Perennial congressional issues include (1) deciding the total appropriation for federal land acquisition, determining the level of acquisition funds for each of the four agencies, and identifying which lands should be acquired; (2) deciding the level of funding for the state grant program; and (3) determining what, if any, other purposes should be funded through LWCF and at what level. The primary context for debating these issues traditionally has been the annual Interior appropriations legislation.

How the Fund Works

The LWCF is not a true trust fund as is generally understood in the private sector. For instance, the fund is credited with revenues totaling $900 million annually under the LWCF Act, but these credited monies cannot be spent unless appropriated by Congress, as noted. Further, interest is not accrued on the accumulated unappropriated balance that has been credited to the LWCF. While some supporters assert that the LWCF was originally intended to be a revolving fund, whereby the money would be maintained in an account separate from the General Treasury that could accrue interest, this has not been the case. Although the LWCF Act has been amended, the fund's basic purpose has not been altered. Over time, notable amendments have raised the authorization ceiling and mandated that offshore oil and gas leasing revenues should make up any shortfall from other specified financing sources.

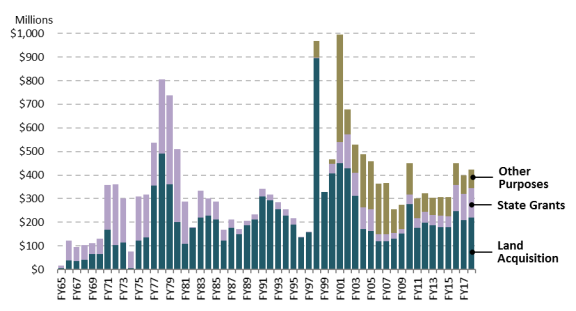

From FY1965 through FY2018, about $40.0 billion has been credited to the LWCF under both the LWCF Act and GOMESA.4 Less than half that amount—$18.4 billion—has been appropriated,5 leaving an unappropriated balance of $21.6 billion in the fund.6 (See Figure 1.)7

|

Figure 1. LWCF Total Receipts and Appropriations, FY1965-FY2018 (in billions of dollars, not adjusted for inflation) |

|

|

Source: Graphic created by CRS. The primary source for the data is the DOI Office of Budget. Additional sources of information include the annual DOI Budget in Brief and congressional documents accompanying the annual Interior appropriations bill. Notes: OCS receipts and appropriations for state grants reflect monies derived under the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act of 2006 (GOMESA; P.L. 109-432, Division C, §105). Recreation fees were not deposited into the fund after FY1990, and are thus shown differently from other revenues that currently accrue to the fund. |

Purposes of LWCF Appropriations

Appropriations from LWCF have been made for three general purposes: (1) federal acquisition of land and waters and interests therein;8 (2) the stateside grants for recreational planning; acquiring recreational lands, waters, or related interests; and developing outdoor recreational facilities; and (3) related purposes.9 Each year, Congress determines the total appropriations from the fund, and the amount provided for each of these three general purposes.

Division Between Federal and State Purposes

The LWCF Act currently states that not less than 40% of the appropriations from the fund are to be available for federal purposes.10 However, as enacted in 1964, the LWCF Act generally had provided for the appropriations from the LWCF to be 60% for state purposes and 40% for federal purposes. The 1964 law stated that "in the absence of a provision to the contrary in the Act making an appropriation from the fund," the appropriation from the fund was to be 60% for state purposes and 40% for federal purposes. It further specified that during the first five years in which appropriations were made from the fund, the President could vary these percentages by not more than 15 percentage points to meet the needs of states and the federal government.

The current language, providing for not less than 40% of funding for federal purposes, resulted from a 1976 amendment enacted as P.L. 94-422. In the conference report on the bill (S. 327), conferees expressed that "Generally, appropriations should continue to reflect the 60-40 allocation established by the Act." However, they noted the "inflexibility" of this division because "States may sometimes be unable to provide the amounts necessary to match their share of the appropriations from the fund," and thus might not be able to use their funding in a given year. In that case, additional funding should be provided to the federal agencies for acquisition in order "to preserve and protect" areas for future generations, according to the conferees.11 At the time of the 1976 amendment, funds were being appropriated for federal land acquisition and the stateside program. Funding for other purposes did not occur until FY1998.

Federal Land Acquisition

The LWCF is the principal source of funds for federal acquisition of lands. Most federal lands are acquired (and managed) by four agencies—the Forest Service (FS) in the Department of Agriculture, and the National Park Service (NPS), Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in DOI. These four agencies manage about 95% of all federally owned lands.12 Of these agencies, the FWS has another significant source of acquisition funding. Specifically, under the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund the FWS has a permanently appropriated source of funding for land acquisition.13 The BLM also has authority to keep the proceeds of certain land sales and use them for subsequent acquisitions and other purposes.

The LWCF Act provides that "unless otherwise allotted in the appropriation Act making them available," appropriations from the fund for federal purposes are to be allotted by the President for certain purposes.14 These purposes include "capital costs" for recreation and fish and wildlife at water resources development projects; land acquisition in recreation areas administered by the Secretary of the Interior for recreational purposes; and land acquisition in national park, national forest, and national wildlife refuge system units. In practice, the appropriations acts typically specify the purposes for which the federal funds are to be used.

In many respects, the process for appropriating funds for federal land acquisition is similar from year to year. The Administration's annual budget submission from each of the four major federal land management agencies generally identifies lands (or interests in lands) each agency seeks to acquire with LWCF funds. Each agency chooses among many potential options in making its annual request, through a three-level process involving identification and prioritization of acquisition projects by field, regional, and headquarters offices. However, the Administration sometimes does not seek funding for individual acquisition projects, as was the case initially in the FY2018 and FY2019 Trump Administration budget submissions to Congress.15 The Administration also might seek funding for certain types of acquisitions, such as those that would facilitate access to federal lands for recreation and sportsmen.16 Congress reviews agency requests, determines the total acquisition funding for each agency, and decides on the portion of funding (if any) for requested types of acquisition (e.g., access for recreation and sportsmen). Congress also typically identifies (in report language) the level of funding for each acquisition project sought by the Administration.

The LWCF Act restricts appropriations to those acquisitions that have been previously authorized by law. However, it allows LWCF appropriations to be used for pre-acquisition work where "authorization is imminent and where substantial monetary savings could be realized."17

Appropriations laws typically provide that LWCF funds for land acquisition remain available until expended, meaning the funds can be carried over from fiscal year to fiscal year. Often an appropriation is not used in the fiscal year provided, because the process for completing a land acquisition has many components and often takes more than one year. These components generally include an appraisal of the value of the parcels, evaluations of the resources contained within the parcels, and title research.

The Administration typically seeks, and appropriations laws have typically provided, a portion of each agency's acquisition funding for one or more related activities. For instance, funds have been provided for acquisition management, costs of land exchanges, and acquisition of lands within the boundaries of federal land units ("inholdings") that may become available throughout the year. Further, in some cases funds have been appropriated for "emergencies" or "hardships," for acquisition of lands from an owner who must sell quickly and where the agency determines there is a need to purchase the lands quickly.18

Stateside Program

Another portion of the LWCF consists of grants to states (including the District of Columbia and U.S. territories) for outdoor recreation purposes. There are two types of grants: traditional and competitive. Both programs are administered by the NPS. Under the traditional grant program, both discretionary and mandatory appropriations are divided among states by the Secretary of the Interior (acting through the NPS). Under the competitive grant program, begun in FY2014, the NPS awards discretionary grants to urbanized areas meeting certain criteria. Under both grant programs, states may "sub-award" grants to state agencies, local units of government, and federally recognized Indian tribes.

Traditional State Grants

The traditional grant program provides matching grants to states for outdoor recreation planning, acquisition of lands and waters, and facility development. Grants are provided for outdoor recreation purposes only, rather than for indoor facilities such as community centers. More than 42,000 grants have been provided throughout the history of the program (since FY1965), with a majority used for developing new recreation facilities or redeveloping older facilities. Acquisitions funded through LWCF state grants must remain in recreation use in perpetuity, unless the Secretary of the Interior approves of the conversion of the land to another use and acceptable replacement lands are substituted. Conversions occur due to changing state or local needs, such as to use park lands to build schools, widen roads, and develop civic facilities. The NPS approves roughly 50-75 conversions yearly nationwide, typically involving a portion of the area funded with an LWCF state grant.

The Secretary of the Interior apportions the appropriation for state grants in accordance with a formula set out in the LWCF Act.19 The formula calls for a portion of the appropriation to be divided equally among the states.20 The remaining appropriation is to be apportioned based on need, as determined by the Secretary.21 Under law, the determination of need is to include the population of the state relative to the population of the United States, the use of outdoor recreation resources within a state by people outside the state, and the federal resources and programs within states. In current practice, population is the biggest factor in determining state need. No state can receive more than 10% of the total appropriation.

Discretionary appropriations for traditional state grants typically are included in the annual Interior appropriations law, without earmarks or other directions to the NPS to guide how these funds should be distributed or spent. States have up to three years to use the discretionary appropriations—the federal fiscal year in which the apportionment is made and the next two fiscal years. It is rare for a state not to use the money during this time, according to the NPS. Under law, the Secretary is to reapportion any amount that is not paid or obligated during the three-year period.

In addition, mandatory appropriations are provided for the traditional state grants only. Specifically, under GOMESA, 12.5% of the revenues from certain OCS leasing in the Gulf of Mexico is directed to the stateside program to be used in accordance with the terms of the LWCF Act. States generally can receive up to $125.0 million in annual stateside appropriations through FY2056, except that the maximum is $162.5 million for each of FY2021 and FY2022. The money is to be in addition to any discretionary amounts appropriated by Congress for the LWCF. Further, these funds are available to the states until expended, unlike the three-year duration of the discretionary funds appropriated annually for the stateside program.22

To be eligible for a grant, a state must prepare and update a statewide outdoor recreation plan. This plan must address the needs and opportunities for recreation and include a program for reaching recreational goals. It generally does not include specific projects. Under law, the plan is required to be approved by the Secretary; this responsibility has been delegated to the NPS. The states award their grant money through a competitive, open project selection process based on their recreation plans and their own priorities and selection criteria. They can use the money for state projects or for pass-through to localities or tribes. States send their ranked projects to the NPS for formal approval and obligation of grant money. Under law, payments to states generally are limited to 50% or less of a project's total costs. The remaining cost is borne by the state project sponsor.23

Competitive State Grants

In FY2014, Congress first appropriated a portion of the LWCF (discretionary) stateside funds for a new nationally competitive outdoor recreation grant program to be developed by the NPS. Congress has continued to fund a competitive program each year, with funding increasing from $3.0 million in FY2014 to $20.0 million in FY2018. Currently, the NPS's "Outdoor Recreation Legacy Partnership Program" provides grants to states for land acquisition and development for outdoor recreation projects that are in or serve densely settled areas with populations of 50,000 or more.24 Priority is given to communities that are underserved in terms of outdoor recreation opportunities and that have sizable populations who are economically disadvantaged. Under the 2018 grant announcement, other factors for project selection include the extent to which the projects directly connect people to the outdoors; create jobs; engage community members; involve public-private partnerships; and require coordination among the public, government, and private sector.25 In 2018, the NPS expects to issue between 25 and 35 grants totaling $13.3 million,26 with individual grants ranging from $250,000 to $750,000. In addition to meeting the requirements in the grant announcement, projects are required to comply with the LWCF Act and other program requirements that apply to the traditional state grants. Such requirements include a nonfederal funding match (generally of at least 50% of project costs), and land use for outdoor recreation in perpetuity except with the approval of the Secretary of the Interior, as discussed above.

Other Purposes

As noted above, the LWCF Act lists the federal purposes to which the President is to allot LWCF funds "unless otherwise allotted in the appropriation Act making them available."27 A portion of the LWCF appropriation has been provided for other federal purposes (i.e., other than land acquisition) in FY1998 and each year since FY2000. Because there is no set of "other purposes" specified to be funded from LWCF, Presidents have sought funds for a variety of purposes and Congress has chosen which, if any, other purposes to fund from LWCF. For instance, for FY2008, President George W. Bush sought LWCF funds for 11 programs within the FWS, FS, and other agencies, and Congress provided funding for two of these programs. Since FY1998, the LWCF has been used for an array of other purposes related to lands and resources, such as maintenance of agency facilities (including deferred maintenance), the Historic Preservation Fund, the Payments in Lieu of Taxes program, the FS Forest Legacy program, FWS State and Tribal Wildlife grants, and FWS Cooperative Endangered Species grants. Since FY2008, however, funds have been appropriated annually for grants under two programs: Forest Legacy, and the Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund.28

Funding History

Overview of Total Appropriations, FY1965-FY2018

Nearly all of the $18.4 billion appropriated throughout the history of the LWCF was discretionary funding. Specifically, $75.0 million (0.4%) of the total was mandatory funding under GOMESA.

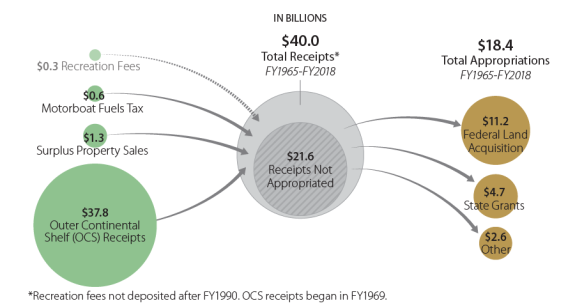

The $18.4 billion appropriated through FY2018 has been unevenly allocated among federal land acquisition, the stateside program, and other purposes, as shown in Figure 2. The largest portion of the total—$11.2 billion (61%)—has been appropriated for federal land acquisition. The four federal land management agencies have received differing portions of this $11.2 billion. Specifically, the NPS has received $4.6 billion (41%); the FS, $3.1 billion (27%); the FWS, $2.4 billion (22%); and the BLM, $1.0 billion (9%).29

The stateside program has received the second-largest portion of LWCF appropriations—$4.7 billion (25% of the total). In the early years, more funds generally went to the stateside program than to land acquisition of the four federal agencies combined. For instance, stateside appropriations exceeded federal land acquisition appropriations during 12 of the 16 years from FY1965 to FY1980. After the mid-1980s, the stateside program declined as a portion of total LWCF appropriations, and received no appropriations (except for program administration) from FY1996 through FY1999. Since that time, the program has received less than 20% of each year's total LWCF appropriations, except in FY2002 and FY2005 and during the most recent three years (FY2016-FY2018). Of these years, the largest percentage of funds for the stateside program was 38% for FY2018, in part due to the relatively large mandatory appropriation in that year.30 Over the last 10 years (FY2009-FY2018), stateside funding has averaged 19% of total LWCF appropriations.31

Other purposes have received the remaining portion of total LWCF appropriations—$2.6 billion (14%). No funds were provided for other purposes until FY1998. By contrast, 28% of total LWCF appropriations from FY1998 through FY2018 have been for other purposes. The FWS and FS have received the largest shares: about $1.4 billion and $1.0 billion, respectively, of the $2.6 billion appropriated for other purposes since FY1998.

|

Figure 2. LWCF Total Appropriations by Type and Agency, FY1965-FY2018 (in billions of dollars, not adjusted for inflation) |

|

|

Source: Graphic created by CRS. The primary source for the data is the DOI Office of Budget. Additional sources of information include the annual DOI Budget in Brief and congressional documents accompanying the annual Interior appropriations bill. Note: State grants reflect monies appropriated under the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act of 2006 (GOMESA; P.L. 109-432, Division C, §105). |

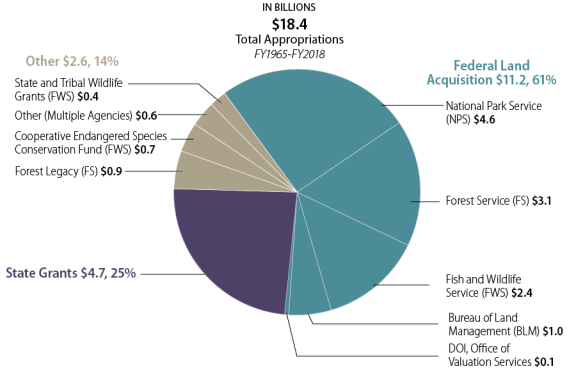

Overview of Mandatory Appropriations, FY2009-FY2018

Mandatory appropriations totaling $75.0 million were provided to the LWCF stateside program during a 10-year period—FY2009-FY2018. Of this total, $8.4 million was first appropriated to the stateside program in FY2009, from proceeds from OCS leasing collected in FY2008.32 Thereafter, disbursements to the stateside program decreased, exceeding $1 million in only one other year through FY2017. The appropriation for FY2018 increased significantly—to $62.6 million—as a result of additional revenue from expansion of the qualified program areas in the Gulf of Mexico. (See Table 1 and Figure 3.) DOI anticipates that mandatory appropriations will remain relatively high in the coming years. For instance, the NPS estimated appropriations to the stateside program at between $85 million and $104 million for each year from FY2019 through FY2029.33 However, these estimates are subject to change.

Table 1. LWCF Annual Mandatory Appropriations, FY2009-FY2018

(in millions of dollars, not adjusted for inflation)

|

Fiscal Year |

Mandatory Appropriations |

|

2009 |

$8.4 |

|

2010 |

0.9 |

|

2011 |

0.3 |

|

2012 |

0.1 |

|

2013 |

0.1 |

|

2014 |

1.4 |

|

2015 |

0.8 |

|

2016 |

0.1 |

|

2017 |

0.3 |

|

2018 |

62.6 |

Source: Annual budget justifications of the NPS at https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/budget.htm.

Notes: Under GOMESA, OCS receipts collected in one fiscal year are appropriated from the LWCF in the following fiscal year. This table shows the year in which the monies were appropriated. Figures are actual except that the FY2018 figure is estimated. Dollars represent the appropriations in the fiscal years indicated and thus are not adjusted for inflation.

|

Figure 3. LWCF Annual Mandatory Appropriations, FY2009-FY2018 (in millions of dollars, not adjusted for inflation) |

|

|

Source: Graphic created by CRS. This data was taken from the annual budget justification of the NPS at https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/budget.htm. Notes: Under GOMESA, OCS receipts collected in one fiscal year are appropriated from the LWCF in the following fiscal year. This graphic shows the year in which the monies were appropriated. Figures are actual except that the FY2018 figure is estimated. |

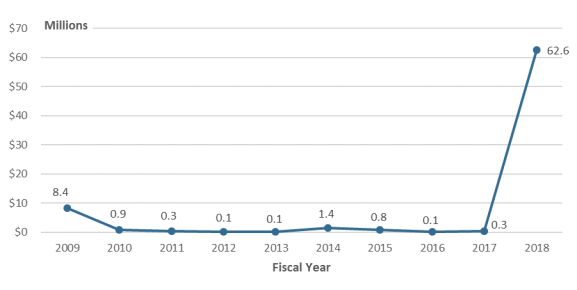

Overview of Discretionary Appropriations, FY1965-FY2018

Annual discretionary appropriations from the LWCF have fluctuated widely since the origin of the program more than 50 years ago. (See Figure 4 and Table 2.) From the origin of the LWCF in FY1965 until FY1998, the discretionary total seldom reached $400 million, surpassing this level only in four years. Specifically, from FY1977 to FY1980, funding varied between $509 million (in FY1980) and $805 million (in FY1978), and averaged $647 million annually. By contrast, annual discretionary appropriations reached or exceeded $400 million in 11 of the 21 most recent years—FY1998 through FY2018.

In FY1998, LWCF discretionary appropriations spiked dramatically—to $969 million—from the FY1997 level of $159 million. FY1998 was the first year that LWCF appropriations exceeded the level the fund was authorized to accumulate in a given year ($900 million).34 The total included $270 million in the usual funding titles for land acquisition by the four federal land management agencies; an additional $627 million in a separate title, funding both the acquisition of the Headwaters Forest in California and New World Mine outside Yellowstone National Park; and $72 million for other purposes.

Table 2. LWCF Annual Discretionary Appropriations by Type, FY1965-FY2018

(in millions of dollars, not adjusted for inflation)

|

Fiscal Year |

Land Acquisition |

State |

Other Purposes |

Total |

|

1965 |

$6 |

$10 |

$0 |

$16 |

|

1966 |

38 |

84 |

0 |

122 |

|

1967 |

36 |

59 |

0 |

95 |

|

1968 |

40 |

64 |

0 |

104 |

|

1969 |

64 |

48 |

0 |

112 |

|

1970 |

66 |

65 |

0 |

131 |

|

1971 |

168 |

189 |

0 |

357 |

|

1972 |

102 |

259 |

0 |

362 |

|

1973 |

113 |

187 |

0 |

300 |

|

1974 |

5 |

71 |

0 |

76 |

|

1975 |

122 |

186 |

0 |

307 |

|

1976 |

136 |

181 |

0 |

317a |

|

1977 |

356 |

182 |

0 |

538 |

|

1978 |

491 |

314 |

0 |

805 |

|

1979 |

361 |

376 |

0 |

737 |

|

1980 |

202 |

307 |

0 |

509 |

|

1981 |

108 |

180 |

0 |

289 |

|

1982 |

176 |

4 |

0 |

180 |

|

1983 |

220 |

115 |

0 |

335 |

|

1984 |

227 |

75 |

0 |

302 |

|

1985 |

213 |

74 |

0 |

287 |

|

1986 |

121 |

47 |

0 |

168 |

|

1987 |

176 |

35 |

0 |

211 |

|

1988 |

150 |

20 |

0 |

170 |

|

1989 |

186 |

20 |

0 |

206 |

|

1990 |

212 |

20 |

0 |

231 |

|

1991 |

308 |

33 |

0 |

342 |

|

1992 |

294 |

23 |

0 |

317 |

|

1993 |

256 |

28 |

0 |

284 |

|

1994 |

228 |

28 |

0 |

256 |

|

1995 |

189 |

28 |

0 |

217 |

|

1996 |

137 |

1 |

0 |

138 |

|

1997 |

158 |

1 |

0 |

159 |

|

1998 |

896 |

1 |

72 |

969 |

|

1999 |

328 |

0 |

0 |

328 |

|

2000 |

406 |

41 |

20 |

467 |

|

2001 |

449 |

90 |

456 |

995b |

|

2002 |

429 |

144 |

105 |

677 |

|

2003 |

313 |

97 |

118 |

529 |

|

2004 |

170 |

94 |

225 |

488 |

|

2005 |

164 |

91 |

203 |

459 |

|

2006 |

120 |

30 |

213 |

363 |

|

2007 |

120 |

30 |

216 |

366 |

|

2008 |

129 |

25 |

101 |

255 |

|

2009 |

152 |

19 |

104 |

275 |

|

2010 |

278 |

40 |

132 |

450 |

|

2011 |

177 |

40 |

84 |

301 |

|

2012 |

199 |

45 |

78 |

322 |

|

2013 |

187 |

43 |

74 |

303 |

|

2014 |

180 |

48 |

78 |

306 |

|

2015 |

178 |

48 |

80 |

306 |

|

2016 |

247 |

110 |

93 |

450 |

|

2017 |

209 |

110 |

81 |

400 |

|

2018 |

220 |

124 |

81 |

425 |

Sources: The primary source for the data is the DOI Office of Budget. Additional sources of information include the annual DOI Budget in Brief and congressional documents accompanying the annual Interior appropriations bill.

Notes: Figures do not reflect $76 million provided for the transition quarter from July 1, 1976, to September 30, 1976. Also, dollars represent the appropriations in the fiscal years indicated and thus are not adjusted for inflation.

a. The FY1976 total appropriation was approximately $393 million including the $76 million for the transition quarter.

b. This figure includes approximately $153 million of Forest Service appropriations in law that were not "warranted" from LWCF, and thus were not officially recorded as taken from this fund. The Government Accountability Office defines warrant as "An official document that the Secretary of the Treasury issues upon enactment of an appropriation that establishes the amount of moneys authorized to be withdrawn from the central accounts that the Department of the Treasury maintains." See U.S. Government Accountability Office, A Glossary of Terms Used in the Federal Budget Process, September 2005, p. 101, http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d05734sp.pdf. Excluding the $153 million that was not warranted, the FY2001 LWCF total was approximately $842 million.

Another spike occurred in FY2001, when discretionary appropriations again exceeded the authorized level and totaled nearly $1 billion. This record level of funding was provided partly in response to President Clinton's Lands Legacy Initiative, which sought $1.4 billion for 21 resource protection programs including the LWCF. It also was provided in response to some congressional interest in securing increased and more certain funding for the LWCF. The 106th Congress considered legislation to fully fund the LWCF and to make it operate like a private-sector trust fund. Such proposals sought to divert offshore oil and gas revenues to a Conservation and Reinvestment Act (CARA) Fund and to permanently appropriate receipts credited to the LWCF, among other related purposes. When it became clear that CARA legislation would not be enacted, Congress included aspects of the legislation in the FY2001 Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations law (P.L. 106-291).35

Over the last 10 years, FY2009 to FY2018, LWCF discretionary appropriations ranged from a low of $275.3 million in FY2009 to a high of $450.4 million in FY2010. (See Table 3 for annual discretionary appropriations, and the portions for acquisition of each agency, the stateside program, and other purposes, over the last 10 years.) The FY2010 high was about half the authorized level, and the $425.0 million appropriated for FY2018, the most recent fiscal year, was nearly half the authorized level. In the three most recent fiscal years (FY2016-FY2018) as well as in FY2010, the total appropriation was at least $400.0 million, and the portion dedicated to land acquisition for all agencies was at least $200.0 million. The land acquisition total ranged from $152.2 million in FY2009 to $277.9 million in FY2010, and it most recently was $220.3 million in FY2018.

During this 10-year period, appropriations for the stateside program fluctuated between $19.0 million for FY2009 and $124.0 million for FY2018. The appropriation for each of the last three fiscal years was at least $110.0 million, and was more than double the level of any prior year during the period.

The appropriations for other purposes were at a low of $74.2 million in FY2013 and a high of $132.5 million in FY2010. They exceeded $100.0 million only in each of the first two years of the period (FY2009-FY2010), with $80.7 million in FY2018.

Table 3. LWCF Annual Discretionary Appropriations by Type and Agency, FY2009-FY2018

(in millions of dollars, not adjusted for inflation)

|

Purpose |

FY2009 |

FY2010 |

FY2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

|

Land Acquisition |

||||||||||

|

Bureau of Land Management |

$14.8 |

$29.7 |

$22.0 |

$22.3 |

$21.2 |

$19.5 |

$19.7 |

$38.6 |

$31.4 |

$24.9 |

|

Fish and Wildlife Service |

42.5 |

86.3 |

54.9 |

54.6 |

50.8 |

54.4 |

47.5 |

68.5 |

60.0 |

63.8 |

|

National Park Service |

45.2 |

86.3 |

54.9 |

57.0 |

52.8 |

50.0 |

50.8 |

63.7 |

52.0 |

56.9 |

|

Forest Service |

49.8 |

63.5 |

32.9 |

52.5 |

49.8 |

43.5 |

47.5 |

63.4 |

54.4 |

64.3 |

|

DOI OVSa |

— |

12.1 |

12.1 |

12.7 |

12.0 |

12.2 |

12.0 |

12.6 |

11.0 |

10.2 |

|

Total Land Acquisition |

152.2 |

277.9 |

176.8 |

199.1 |

186.6 |

179.6 |

177.6 |

246.9 |

208.8 |

220.3 |

|

State Grants |

19.0 |

40.0 |

39.9 |

44.9 |

42.6 |

48.1 |

48.1 |

110.0 |

110.0 |

124.0 |

|

Other Purposes |

104.1 |

132.5 |

83.8 |

78.3 |

74.2 |

78.4 |

80.4 |

93.1 |

81.1 |

80.7 |

|

Total |

$275.3 |

$450.4 |

$300.5 |

$322.3 |

$303.3 |

$306.0 |

$306.1 |

$450.0 |

$400.0 |

$425.0 |

Sources: The primary source for the data is the DOI Office of Budget. Additional sources of information include the annual DOI Budget in Brief and congressional documents accompanying the annual Interior appropriations bill.

Notes: Dollars represent the appropriations in the fiscal years indicated and thus are not adjusted for inflation. Figures reflect any reductions due to the use of prior-year funds.

a. OVS is the Office of Valuation Services. Figures reflect appropriations from LWCF to DOI Departmental Management for land acquisition appraisal services.

Both the dollar amount and percentage of LWCF appropriations provided to other purposes have varied widely since FY1998, as shown in Table 4. The dollar value of the appropriations for other purposes was much higher in FY2001 than any other year, when these appropriations were used to fund programs in the Clinton Administration's Lands Legacy Initiative. The highest percentage of funds provided for other purposes occurred in FY2006 and FY2007, in response to President George W. Bush's request for funding for an array of other programs. In some years, Congress has appropriated significantly less for other purposes than the Administration has requested. For instance, for FY2008 the Bush Administration sought $313.1 million for other purposes of a total request of $378.7 million. Congress appropriated $101.3 million for other purposes of a total appropriation of $255.1 million.

Table 4. LWCF Discretionary Appropriations for Other Purposes, FY1998-FY2018

(in millions of dollars, not adjusted for inflation)

|

Fiscal Year |

LWCF Discretionary |

Appropriations for Other Purposes |

Other Purposes as % of Discretionary Appropriations |

|

FY1998 |

$969.1 |

$72.0 |

7% |

|

FY1999 |

328.2 |

0 |

0 |

|

FY2000 |

466.9 |

20.0 |

4 |

|

FY2001 |

995.4a |

456.0 |

46 |

|

FY2002 |

677.2 |

104.6 |

15 |

|

FY2003 |

528.9 |

118.4 |

22 |

|

FY2004 |

488.1 |

224.7 |

46 |

|

FY2005 |

459.0 |

203.5 |

44 |

|

FY2006 |

362.8 |

213.1 |

59 |

|

FY2007 |

366.1 |

216.1 |

59 |

|

FY2008 |

255.1 |

101.3 |

40 |

|

FY2009 |

275.3 |

104.1b |

38 |

|

FY2010 |

450.4 |

132.5 |

29 |

|

FY2011 |

300.5 |

83.8 |

28 |

|

FY2012 |

322.3 |

78.3 |

24 |

|

FY2013 |

303.3 |

74.2 |

24 |

|

FY2014 |

306.0 |

78.4 |

26 |

|

FY2015 |

306.1 |

80.4 |

26 |

|

FY2016 |

450.0 |

93.1 |

21 |

|

FY2017 |

400.0 |

81.1 |

20 |

|

FY2018 |

425.0 |

80.7c |

19 |

Sources: The primary source for the data is the DOI Office of Budget. Additional sources of information include the annual DOI Budget in Brief and congressional documents accompanying the annual Interior appropriations bill.

Notes: Dollars represent the appropriations in the fiscal years indicated and thus are not adjusted for inflation.

a. This figure includes approximately $153 million of Forest Service appropriations in law that were not "warranted" from LWCF.

b. This figure has been reduced by $8.0 million due to the use of prior-year funds.

c. This figure has been reduced by $5.9 million due to the use of prior-year funds.

Current Issues

Through authorizing and appropriations legislation, hearings, and other debates, Congress is considering an array of issues related to the LWCF. Several of these issues are summarized below.

Level of Funding

There are differing opinions as to the optimal level of LWCF appropriations. The LWCF has broad support from resource protection advocates, many of whom seek stable and predictable funding through consistent levels of appropriations. Most of these advocates seek higher appropriations in general. For instance, for several years the Obama Administration proposed appropriations of $900 million for LWCF. Some advocates have specific priorities, such as higher acquisition funding for one of the four federal agencies, the state grant program, or a particular site or area. Advocates of higher federal land acquisition funding promote a strong federal role in acquiring and managing sensitive areas and natural resources.

In contrast, there is broad opposition to the LWCF based on varied concerns, with opponents generally seeking reduced levels of funds for LWCF. Some opponents seek to reduce the size of the federal estate and minimize further federal acquisition of land either generally or at specific sites, especially in the West, where federal ownership is already concentrated. Other concerns involve preferences for private land ownership or state and local ownership and management of resources, potential impacts of federal land ownership on uses of private lands, and reduced local tax revenues that result from public ownership. For instance, the House Committee on the Budget has supported reducing the federal estate and giving state and local governments more control of resources within their boundaries.36 Others have sought LWCF reductions as part of a broader focus on reducing the federal deficit.

Reauthorization of LWCF Act Provisions

Under the LWCF Act, the authority for the LWCF to receive $900 million in revenues annually is scheduled to expire on September 30, 2018.37 Congress is debating whether to extend this authority, and if so whether to authorize a short, long, or permanent extension. Many LWCF advocates favor relatively long or permanent extension, on the assertion that the program has been successful across the nation for more than 50 years in protecting valuable lands and resources and providing lands and infrastructure needed for public health, recreation, and tourism. They contend that continuity and stability of the land protection and recreational opportunities that LWCF supports are important national goals, and ones that will help communities to attract businesses, new residents, and tourists. They note the sufficiency of LWCF's dedicated funding stream for supporting the program.

Some proponents of a short-term extension or of expiration assert that the LWCF currently has sufficient funds to meet the nation's land acquisition and recreation needs for many years to come. They point to the relatively large balance of unappropriated monies in the LWCF that Congress could appropriate, as well as to the substantial levels of mandatory funding that are anticipated under GOMESA for the stateside program. For others, structural reforms of the program would be needed before a long-term extension might be viable, such as to direct funding away from federal land acquisition and to other activities, such as maintenance of federal lands and facilities or programs that support states. Others favor depositing the OCS revenues in the General Fund of the Treasury (rather than in the LWCF) to support federal activities generally or specific priority programs.

Mandatory vs. Discretionary Appropriations

Some advocates of higher LWCF funding seek partial or full permanent appropriations of monies under the LWCF Act. For instance, the Obama Administration proposed $900 million for LWCF for FY2017 through a combination of discretionary ($475.0 million) and mandatory ($425.0 million) appropriations. Further, the Obama Administration proposed amending current law to appropriate mandatory funding of $900 million annually beginning in FY2018.38 As attributes of the mandatory approach, advocates cite the certainty and predictability of program funding generally and in particular in fostering the ability of agencies to undertake multiyear, large-scale, and collaborative acquisitions.39 They also note the existence of a dedicated funding stream for LWCF at the authorized level of $900 million and the original intent of Congress that revenues to the fund be used for the LWCF Act's purposes. Questions include how to offset any new permanent appropriations and how to allocate permanent appropriations among different LWCF programs and purposes.

Proponents of discretionary appropriations support retaining Congress's authority to determine annually the level of funding needed for LWCF overall and for the various program components. They note that through the discretionary process, the need for LWCF appropriations can be assessed in comparison with other natural resource programs and broader governmental needs. This approach also has been valued as providing recurring opportunities for program oversight. For instance, the House Committee on the Budget has supported keeping land acquisition funding as discretionary to allow for regular oversight.40

Maintenance vs. Acquisition

There are differing opinions as to how LWCF funds should be used. Some Members and others have asserted that maintaining (and rehabilitating) the land and facilities that federal agencies already own should take priority over further acquisitions. For instance, in an opening statement, the chair of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources expressed interest in shifting "the federal focus away from land acquisition, particularly in Western states, toward maintaining and enhancing the accessibility and quality of the resources that we have."41 Some cite the deferred maintenance needs of the agencies as a higher priority than acquisition, and one that requires funding through additional sources, including LWCF.42 As an example, the Trump Administration did not initially seek funding for individual acquisitions by agencies in FY2019, asserting that at a time when DOI has "billions of dollars in deferred maintenance, land acquisitions are lower priority activities than maintaining ongoing operations and maintenance."43

Supporters of retaining a strong LWCF role in acquisition cite a continued need to preserve iconic resources and provide additional opportunities for public recreation and other land uses. They assert economic benefits of federal land ownership and improvements of federal land management through consolidation of ownership.44 In addition, since federal agencies cannot use LWCF funds for maintenance, some supporters of this priority favor more funding to other accounts that can be used for maintenance while retaining the LWCF for acquisitions.45 Such accounts are within the land management agency budgets as well as within the Department of Transportation (for roads).

Access for Recreation

While the public has access to most federal lands, some areas have limited access or are unavailable to the public. This is sometimes the case because private or state lands, or geographical features such as mountains or rivers, limit or block public access. Proponents of enhanced recreational access have sought to amend the LWCF Act to set aside a portion of funding for federal acquisitions for access purposes. The focus has been on acquisition of lands and interests (e.g., easements and rights of way) that support recreational access for hunting and fishing, among other recreational pursuits. Proponents cite insufficient opportunity for recreating in some areas and broader health, economic, and other values of recreating on public lands.

Opposition to such a set-aside could relate to concerns about the extent of federal land ownership, preferences for prioritizing LWCF for other purposes, or satisfaction that the agencies are sufficiently prioritizing recreational access. According to BLM, for instance, "nearly 100 percent of LWCF funding over the past several years has been used for projects that enhance public access for recreation."46 For the Forest Service, 39 of the 40 acquisitions completed in FY2014 with LWCF funding provided improved access or legal access where none existed, according to the agency.47 However, the extent to which agencies prioritize acquisition funding for recreational access might vary among all agencies and from year to year.

Stateside Program

One area of congressional focus has been the level of funds for the stateside program. In some years, Congress and/or the Administration have not supported funds, or have supported relatively low levels of funds, for new stateside grants. Cited reasons have included that state and local governments have alternative sources of funding for parkland acquisition and development, the current program could not adequately measure performance or demonstrate results, the federal government supports states through other natural resource programs, and large federal deficits require a focus on core federal responsibilities.

Stateside supporters contend that the program contributes significantly to statewide recreation planning, state leadership in protection and development of recreation resources, and long-term outdoor recreation in areas that are readily accessible to communities. They see the program as a way to help fiscally constrained local governments and leverage state and local funds for recreation. Further, advocates assert that investments in recreation save money in other areas; for instance, they say that these investments promote healthier lifestyles and thus save health care expenditures.48 Some prefer state acquisition (and development) of lands with LWCF funds over federal acquisition of lands.

Whether to amend the LWCF Act to specify a percentage or dollar amount of the appropriations for the stateside program, and if so, the optimal level, are under debate. The level of discretionary funding for the stateside program is likely to be of continued interest in part due to the substantial increase in mandatory funds for the program under GOMESA, beginning in FY2018.

Another issue under consideration is whether to change the way that funds are apportioned to the states. Under the traditional state grant program, a portion of the appropriation is to be distributed equally among the states, with the percentage varying depending on the total amount of appropriations. Further, the Secretary of the Interior has discretion to apportion the balance based on need, and population has been the biggest factor in determining need. Since FY2014, Congress has approved a portion of the state grant funds for a competitive grant program. The extent to which the state grant program should be competitive, and the criteria that should be used in any competitive program, are of ongoing interest.

Other Programs

Another focus has been which, if any, purposes other than federal land acquisition and stateside grants should be funded through the LWCF. As discussed above, whether to use the fund for maintenance has been under examination. Some seek to channel LWCF funding to an array of land protection purposes. For instance, the George W. Bush Administration sought LWCF funds for cooperative conservation programs through which federal land managers partner with other landowners to protect natural resources and improve recreation on lands under diverse ownership. The Obama Administration also supported the use of LWCF funds for other purposes, although generally fewer than the Bush Administration. Some proposals seek to enhance funding for programs that benefit states, with a shift of resources from federal lands to state grant programs. Still other proposals would provide LWCF funding to a more diverse programs and activities.49

A factor in the debate has been the unappropriated balance in the fund, and whether to allow these funds to be used for broader purposes beyond those currently authorized. Traditional fund beneficiaries and others have expressed concern about expanding the uses of appropriations, particularly if that expansion is accompanied by reductions in the amount available for federal land acquisition or state grants.