Introduction

Congress is currently considering reauthorization of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). The House passed a reauthorization bill (H.R. 2874) in November 2017, and three bills have been introduced in the Senate, but so far the NFIP has received a series of short-term reauthorizations. The debate over a longer reauthorization of the NFIP is taking place during the 2018 hurricane season, and in the aftermath of the 2017 hurricane season, which produced widespread flooding and renewed concern about the structure of the NFIP and its solvency in the face of catastrophic flood losses.

The NFIP is authorized by the National Flood Insurance Act of 19681 and was reauthorized until September 30, 2017, by the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012 (BW-12).2 Congress amended elements of BW-12, but did not extend the NFIP's authorization further in the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014 (HFIAA).3 The NFIP received a short-term reauthorization through December 8, 2017,4 a second short-term reauthorization through December 22, 2017,5 and a third short-term reauthorization through January 19, 2018.6 The NFIP lapsed between January 20 and January 22, 2018, and received a fourth short-term reauthorization until February 8, 2018.7 The NFIP lapsed for approximately eight hours during a brief government shutdown in the early morning of February 9, 2018, and was then reauthorized until March 23, 2018.8 The NFIP received a sixth reauthorization until July 31, 2018,9 and a seventh reauthorization until November 30, 2018.10

The NFIP is managed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), through its subcomponent Federal Insurance and Mitigation Administration (FIMA). The general purpose of the NFIP is both to offer primary flood insurance to properties with significant flood risk, and to reduce flood risk through the adoption of floodplain management standards. A longer-term objective of the NFIP is to reduce federal expenditure on disaster assistance after floods. The NFIP is discussed in more detail in CRS Report R44593, Introduction to the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. A brief overview of private flood insurance in the NFIP is given in CRS Insight IN10450, Private Flood Insurance and the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

The NFIP is the primary source of flood insurance coverage for residential properties in the United States. As of May 2018, the NFIP had over 5 million flood insurance policies providing over $1.28 trillion in coverage. The program collects nearly $3.6 billion in annual premium revenue.11 Nationally, as of July 2018, 22,322 communities in 56 states and jurisdictions participated in the NFIP.12 According to FEMA, the program saves the nation an estimated $1.87 billion annually in flood losses avoided because of the NFIP's building and floodplain management regulations.13 FEMA expects this amount to increase over time as additional new construction is built to increasingly better standards.14

Floods are the most common natural disaster in the United States, and in recent years all 50 states have experienced flood events.15 U.S. flood losses in 2016 were about $17 billion, with losses from five individual flood-related events in 2016 exceeding $1 billion.16 2017 was the most costly year for U.S. hurricane losses on record. Losses from the Midwest flooding in April and May 2017 are estimated at $1.7 billion and losses from the California flooding in February 2017 at $1.5 billion.17 The total for the 2017 hurricanes significantly exceeds the previous record of $214.8 billion (CPI-adjusted), from the 2005 hurricane season.18 Total losses (insured and uninsured) for the 2017 hurricane season are estimated at a record $270.3 billion, with losses for Hurricane Harvey estimated at $127.5 billion, Hurricane Maria at $91.8 billion, and Hurricane Irma at $51.0 billion.19

This report summarizes key insurance reform provisions in recent legislation and identifies key issues for congressional consideration as part of the possible reauthorization of the NFIP. It describes selected provisions in the bill to reauthorize the NFIP passed by the House (H.R. 2874, the 21st Century Flood Reform Act) and the bills introduced in the Senate that relate to the issues discussed in the report. The provisions discussed in the report are listed in Table 1 at the end of this report.

Expiration of Certain NFIP Authorities

The statute for the NFIP does not contain a comprehensive expiration, termination, or sunset provision for the whole of the program. Rather, the NFIP has multiple different legal provisions that generally tie to the expiration of key components of the program. Unless reauthorized or amended by Congress, the following will occur on November 30, 2018:

- The authority to provide new flood insurance contracts will expire.20 Flood insurance contracts entered into before the expiration would continue until the end of their policy term of one year.

- The authority for NFIP to borrow funds from the Treasury will be reduced from $30.425 billion to $1 billion.21

Other activities of the program would technically remain authorized following November 30, 2018, such as the issuance of Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) grants.22

Legislative Action in the 115th Congress

The House Financial Services Committee completed markup on June 21, 2017, of seven bills23 to reform and reauthorize the NFIP. The 21st Century Flood Reform Act (H.R. 2874) came to the House floor under H.Res. 616, and included provisions from the six other bills. H.R. 2874 passed the House on a vote of 237-189 on November 14, 2017. H.R. 2874 would authorize the NFIP until September 30, 2022.

Three bills have been introduced in the Senate that reauthorize the expiring provisions of the NFIP: S. 1313 (Flood Insurance Affordability and Sustainability Act of 2017), S. 1368 (Sustainable, Affordable, Fair, and Efficient [SAFE] National Flood Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2017),24 and S. 1571 (National Flood Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2017). None of these bills have yet been considered by the committee of jurisdiction. S. 1313 would authorize the NFIP until September 30, 2027; S. 1368 would authorize the NFIP until September 30, 2023; and S. 1571 would authorize the NFIP until September 30, 2023.

The remainder of this report will summarize relevant background information and proposed changes to selected areas of the NFIP in H.R. 2874, S. 1313, S. 1368, and S. 1571. The report does not examine every provision in detail, but focuses on selected provisions that would introduce significant changes to the NFIP, particularly those related to the issues identified by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) described below.

Potential Issues for Consideration by Congress

In a recent report, GAO examined actions which Congress and FEMA could take to reduce federal fiscal exposure and improve national resilience to floods, and recommended that Congress should consider comprehensive reform covering six areas: (1) outstanding debt; (2) premium rates; (3) affordability; (4) consumer participation; (5) barriers to private sector involvement; and (6) NFIP flood resilience efforts.25 This report will discuss the areas identified by GAO as well as additional issues which Congress may wish to consider.

As a public insurance program, the goals of the NFIP were originally designed differently from the goals of private-sector companies. As currently authorized, the NFIP also encompasses social goals to provide flood insurance in flood-prone areas to property owners who otherwise would not be able to obtain it, and reduce government's cost after floods.26 The NFIP also engages in many "non-insurance" activities in the public interest: it disseminates flood risk information through flood maps, requires communities to adopt land use and building code standards in order to participate in the program, potentially reduces the need for other post-flood disaster aid, contributes to community resilience by providing a mechanism to fund rebuilding after a flood, and may protect lending institutions against mortgage defaults due to uninsured losses. The benefits of such tasks are not directly measured in the NFIP's financial results from underwriting flood insurance.27

From the inception of the NFIP, the program has been expected to achieve multiple objectives, some of which may conflict with one another

- To ensure reasonable insurance premiums for all;

- To have risk-based premiums that would make people aware of and bear the cost of their floodplain location choices;

- To secure widespread community participation in the NFIP and substantial numbers of insurance policy purchases by property owners; and

- To earn premium and fee income that, over time, covers claims paid and program expenses.28

|

NFIP Issues For Consideration by Congress Discussed in This Report "NFIP Debt and Solvency of the Program" "Premium Subsidies and Cross-Subsidies" "NFIP Borrowing from Treasury" "Affordability of Flood Insurance" "Increasing Participation in the NFIP" "The Role of Private Insurance in U.S. Flood Coverage" "Properties with Multiple Losses" |

NFIP Debt and Solvency of the Program

GAO noted that competing aspects of the NFIP, notably the desire to keep flood insurance affordable while making the program fiscally solvent, have made it challenging to reform the program. Promoting participation in the program, while at the same time attempting to fund claims payments with the premiums paid by NFIP policyholders, provides a particular challenge.29 Throughout its history, the NFIP has been asked to set premiums that are simultaneously "risk-based" and "reasonable." Different Administrations and Congresses have placed varied emphases and priorities on those goals for premium setting.30

GAO has reported in several studies that NFIP's premium rates do not reflect the full risk of loss because of various legislative requirements, which exacerbates the program's fiscal exposure. GAO also noted in several reports that while Congress has directed FEMA to provide subsidized premium rates for policyholders meeting certain requirements, it has not provided FEMA with funds to offset these subsidies and discounts, which has contributed to FEMA's need to borrow from the U.S. Treasury to pay NFIP claims.31

NFIP Premiums and Surcharges

As of January 2018, the written premium on approximately 5 million policies in force was $3.5 billion.32 The maximum coverage for single-family dwellings (which also includes single-family residential units within a 2-4 family building) is $100,000 for contents and up to $250,000 for buildings coverage. The maximum available coverage limit for other residential buildings is $500,000 for building coverage and $100,000 for contents coverage, and the maximum coverage limit for non-residential business buildings is $500,000 for building coverage and $500,000 for contents coverage.

Included within NFIP premiums are several fees and surcharges mandated by law on flood insurance policies. First, the Federal Policy Fee (FPF) was authorized by Congress in 1990 and helps pay for the administrative expenses of the program, including floodplain mapping and some of the insurance operations.33 The amount of the Federal Policy Fee is set by FEMA and can increase or decrease year to year. As of October 2017, the fee is $50 for Standard Flood Insurance Policies (SFIPs), $25 for Preferred Risk Policies (PRPs),34 and $25 for contents-only policies.35 Second, a reserve fund assessment was authorized by Congress in BW-12 to establish and maintain a reserve fund to cover future claim and debt expenses, especially those from catastrophic disasters.36 By law, FEMA is required to maintain a reserve ratio of 1% of the total loss exposure through the reserve fund assessment.37 As of February 2018, the amount required for the reserve fund ratio was approximately $12.79 billion. However, FEMA is allowed to phase in the reserve fund assessment to obtain the ratio over time, with an intended target of not less than 7.5% of the 1% reserve fund ratio in each fiscal year (so, using February 2018 figures, not less than approximately $959 million each year). The reserve fund assessment has increased from its original status, in October 2013, of 5% on all Standard Flood Insurance Policies and 0% on Preferred Risk Policies.38 Since April 2016, FEMA has charged every NFIP policy a reserve fund assessment equal to 15% of the premium.39 However, FEMA has stated that as long as the NFIP maintains outstanding debt, it would expect that the reserve fund will not reach the required balance, as amounts collected may be periodically transferred to Treasury to reduce the NFIP's debt.40

In addition to the reserve fund assessment, all NFIP policies are also assessed a surcharge following the passage of HFIAA.41 The amount of the surcharge is dependent on the type of property being insured. For primary residences, the charge is $25; for all other properties, the charge is $250.42 Revenues from the surcharge are deposited into the reserve fund. The HFIAA surcharge is not considered a premium and is currently not included by FEMA when calculating limits on insurance rate increases.43

Premium Subsidies and Cross-Subsidies

Except for certain subsidies, flood insurance rates in the NFIP are directed to be "based on consideration of the risk involved and accepted actuarial principles,"44 meaning that the rate is reflective of the true flood risk to the property. However, Congress has directed FEMA not to charge actuarial rates for certain categories of properties and to offer discounts to other classes of properties in order to achieve the program's objective that owners of existing properties in flood zones could afford flood insurance. There are three main categories of properties which pay less than full risk-based rates.

Pre-FIRM Subsidy

Pre-FIRM properties are those which were built or substantially improved before December 31, 1974, or before FEMA published the first Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM) for their community, whichever was later.45 Therefore, by statute, premium rates charged on structures built before they were first mapped into a flood zone that have not been substantially improved, known as pre-FIRM structures, are allowed to have lower premiums than what would be expected to cover predicted claims. The availability of this pre-FIRM subsidy was intended to allow preexisting floodplain properties to contribute in some measure to pre-funding their recovery from a flood disaster instead of relying solely on federal disaster assistance. In essence, the flood insurance could distribute some the financial burden among those protected by flood insurance and the public.

BW-12 phased out almost all subsidized insurance premiums, requiring FEMA to increase rates on certain subsidized properties at 25% per year until full-risk rates46 were reached: these included secondary residences, businesses, severe repetitive loss properties,47 and properties with substantial cumulative damage.48 Subsidies were eliminated immediately for properties where the owner let the policy lapse, any prospective insured who refused to accept offers for mitigation assistance, and properties purchased after or not insured by NFIP as of July 6, 2012. All properties with subsidies not being phased out at higher rates, or already eliminated, were required to begin paying actuarial rates following a five-year period, phased in at 20% per year, after a revised or updated FIRM was issued for the area containing the property.49 Thus the subsidies on pre-FIRM properties would have been eliminated within five years following the issuance of a new FIRM to a community. As BW-12 went into effect, constituents from multiple communities expressed concerns about the elimination of lower rate classes, arguing that it created a financial burden on policyholders, risked depressing home values, and could lead to a reduction in the number of NFIP policies purchased.50 Concerns over the rate increases created by BW-12 led to the passage of HFIAA, which reinstated certain premium discounts and slowed down some of the BW-12 premium rate increases.51 HFIAA repealed the property-sale trigger for an automatic full-risk rate and slowed the rate of phaseout of the pre-FIRM subsidy for most primary residences, allowing for a minimum and maximum increase in the amount for the phaseout of pre-FIRM subsidies for all primary residences of 5%-18% annually.52 HFIAA retained the 25% annual phaseout of the subsidy from BW-12 for all other categories of properties.53 As of September 2016, approximately 16.1% of NFIP policies received a pre-FIRM subsidy.54 Historically, the total number of pre-FIRM policies is relatively stable, but the percentage of those policies by comparison to the total policy base has decreased.55

Newly Mapped Subsidy

HFIAA established a new subsidy56 for properties that are newly mapped into a Special Flood Hazard Area (SFHA)57 on or after April 1, 2015, if the applicant obtains coverage that is effective within 12 months of the map revision date. Certain properties may be excluded based on their loss history.58 The rate for eligible newly mapped properties is equal to the PRP rate, but with a higher Federal Policy Fee,59 for the first 12 months following the map revision. After the first year, the newly mapped rate begins to transition to a full-risk rate, with annual increases to newly mapped policy premiums calculated using a multiplier that varies by the year of the map change.60 As of September 2016, about 3.9% of NFIP policies receive a newly mapped subsidy.61

Grandfathering

Using the authority to set rate classes for the NFIP and to offer lower than actuarial premiums,62 FEMA allows owners of properties that were built in compliance with the FIRM in effect at the time of construction to maintain their old flood insurance rate class if their property is remapped into a new flood rate class. This practice is colloquially referred to as "grandfathering," "administrative grandfathering," or the "grandfather rule" and is separate and distinct from the pre-FIRM subsidy.63 FEMA does not consider the practice of grandfathering to be a subsidy for the NFIP, per se, because the discount provided to an individual policyholder is cross-subsidized by other policyholders in the NFIP. Thus, while grandfathering does intentionally allow policyholders to pay premiums that are less than their known actuarial rate, the discount is offset by others in the same rate class as the grandfathered policyholder.

Congress implicitly eliminated the practice of offering grandfathering to policyholders after new maps were issued in BW-12, but then subsequently reinstated the practice in HFIAA, which repealed the BW-12 provision that terminated grandfathering and allowed grandfathered status to be passed on to the new owners when a property is sold.64 FEMA does not have a definitive estimate on the number of properties that have a grandfathered rate in the NFIP, though data are being collected to fulfill a separate mandate of HFIAA.65 Unofficial estimates suggest that at least 10%-20% of properties are grandfathered, and these figures may increase with time as newer maps are introduced in high population areas.66

Summary

The current categories of properties which pay less than the full risk-based rate are determined by the date when the structure was built relative to the date of adoption of the FIRM, rather than the flood risk or the ability of the policyholder to pay. Other ways of reforming the premium structure to reflect full risk-based rates could address a number of the policy goals identified by GAO. For example, actuarially sound rates could place the NFIP on a more financially sustainable path, risk-based price signals could give policyholders a clearer understanding of their true flood risk, and a reformed rate structure could encourage more private insurers to enter the market. However, charging actuarially sound premiums may mean that insurance for some properties is considered unaffordable, or that premiums increase at a rate which may be considered to be politically unacceptable.

Provisions Related to Premiums and Surcharges in H.R. 2874

- Section 102 would phase out the pre-FIRM subsidy for primary residences at a rate of 6.5%-15% (compared to the current rate of 5%-18%), except that in the first year after enactment, the minimum rate increase would be 5%; in the second year after enactment, the minimum rate increase would be 5.5%; and in the third year of enactment, the minimum rate increase would be 6%. The phaseout of the pre-FIRM subsidy for other categories of properties (non-primary residences, non-residential properties, severe repetitive loss properties, properties with substantial cumulative damage, and properties with substantial damage or improvement after July 6, 2012) would remain at 25%. This section would make it possible, but not certain, for FEMA to raise premiums more rapidly than under current legislation by increasing the minimum rate at which the pre-FIRM subsidy could be removed for primary residences.

- Section 105 would require FEMA, not later than two years after enactment, to calculate premium rates based on a consideration of the differences in flood risk resulting from coastal flood hazards and riverine, or inland flood hazards. Six months prior to the effective date of risk premium rates, FEMA would be required to publish in the Federal Register an explanation of the bases for, and methodology used to determine, the chargeable premium rates to be effective for flood insurance coverage under this title. Certain aspects of coastal flood risk are already incorporated into NFIP rates, notably risk from wave action (known as the "V" zone); how this may change with this possible new requirement is not yet known.

- Section 111 would require FEMA to conduct a study to evaluate insurance industry best practice and develop a feasible implementation plan and projected timeline for including the replacement cost value of a structure in setting NFIP premium rates. FEMA would be required to begin gradually phasing in the use of replacement cost value in setting NFIP premium rates 12 months after enactment, with replacement cost value to be used in setting all NFIP premium rates by December 31, 2020. If this provision were enacted, it is anticipated that those structures with higher replacement costs than current local or national averages would begin paying more for their NFIP coverage than those structures that are below the average, which would pay less. How much more, or how much less, is uncertain.

- Section 112 would cap the premiums for 1-4 unit residential properties with elevation data meeting FEMA's standards at $10,000 per year, adjusted for inflation every five years. There is currently no statutory cap on premiums. This cap could affect approximately 800 properties, or 0.02% of NIFP policies,67 though that figure is subject to considerable change (likely increasing) as premium rates change in the future.

- Section 301 would require FEMA, not later than three years from enactment, to calculate premium rates based on both the risk identified by the applicable FIRMs and by other risk assessment data and tools, including risk assessment models and scores from appropriate sources. This provision would expand on the existing method of determining rates (the FIRM) and allow alternatives, such as a risk score methodology (for example, a scale of 1 to 10 or 1 to 100, where the premiums would increase with the numerical score). Until FEMA develops these new risk assessment tools, it is not possible to say how this would affect premiums.

- Section 502 would increase the HFIAA surcharge from $25 to $40 for primary residences and from $250 to $275 for non-residential properties and most non-primary residences. However, the HFIAA surcharge for non-primary residences which are eligible for a Preferred Risk Policy would drop from $250 to $125. This provision would increase the amount that most policyholders pay for flood insurance. FEMA does not include the HFIAA surcharge in their calculation of premium rate increases,68 so this increase would not be affected by the cap set out in Section 102.

- Section 503 would require FEMA, beginning in FY2018, to place in the reserve fund an amount equal to not less than 7.5% of the required reserve ratio. If in any given year FEMA does not do so, for the following fiscal year the Administrator would be required to increase the reserve fund assessment by at least one percentage point over the rate of the annual assessment (i.e., from the current 15% to 16%), and to continue such increases until the fiscal year in which the statutory reserve ratio is achieved. This provision would likely increase premiums for all NFIP policyholders.69

Provisions Related to Premiums and Surcharges in Senate Bills

- S. 1313, Section 207, would require FEMA to conduct a study to evaluate insurance industry best practice and develop a feasible implementation plan and projected timeline for including the replacement cost value of structures in setting NFIP premium rates. FEMA would be required to begin gradually phasing in the use of replacement cost value in setting NFIP premium rates 12 months after enactment, with replacement cost value to be used in setting all NFIP premium rates four years after enactment.

- S. 1313, Section 209, would establish a baseline amount that tracks the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) maximum loan limits for single-family dwellings.70 This section would set the contents coverage limits at 50% of the baseline amount. The coverage limit for single-family dwellings would be set at the baseline amount and the coverage limit for other residential and non-residential properties at 200% of the baseline amount. As the Fannie Mae loan limit increases, the NFIP building coverage limits would also increase.

- S. 1368, Section 102, would prohibit FEMA from increasing the amount of covered costs above 10% per year on any policyholder during the six-year period beginning on the date of enactment. Covered costs include premiums, surcharges (including the surcharge for Increased Cost of Compliance coverage71 and the HFIAA surcharge), and the Federal Policy Fee. This would limit the rate of increase of covered costs for all categories of policies, not just policies for primary residences, and would be particularly significant for those policies where the pre-FIRM subsidy is currently being phased out at 25% per year. This section would also amend the basis on which premiums are calculated so that an average historical loss year72 would exclude catastrophic loss years. This would probably lower premiums for all policyholders.

- S. 1368, Section 104, would raise the building coverage limits to $500,000 for single-family dwellings and $1,500,000 for non-residential buildings.

- S. 1571, Section 301, would require FEMA to conduct a study to evaluate insurance industry best practices and develop a feasible implementation plan and projected timeline for including the replacement cost value in setting NFIP premium rates. FEMA would be required to submit a report not later than 18 months after enactment, and implement the recommendations one year after submitting the report.

NFIP Borrowing from Treasury

The NFIP was not designed to retain funding to cover claims for truly extreme events; instead, the statute allows the program to borrow money from the Treasury for such events.73 For most of the NFIP's history, the program has generally been able to cover its costs, borrowing relatively small amounts from the U.S. Treasury to pay claims, and then repaying the loans with interest.74 However, Congress increased the level of NFIP borrowing to pay claims in the aftermath of the 2005 hurricane season (particularly Hurricanes Katrina, Rita and Wilma), increasing the borrowing limit to $18.5 billion in 2005,75 and increasing the borrowing limit again in 2006 to $20.775 billion.76 Following Hurricane Sandy, Congress increased the borrowing limit of the NFIP to the current $30.425 billion.77 In January 2017, the NFIP borrowed $1.6 billion due to losses in 2016 (the August 2016 Louisiana floods and Hurricane Matthew).78 On September 22, 2017, the NFIP borrowed the remaining $5.825 billion from the Treasury to cover claims from Hurricane Harvey, reaching the NFIP's authorized borrowing limit of $30.425 billion.79 On October 26, 2017, Congress cancelled $16 billion of NFIP debt, making it possible for the program to pay claims for Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria.80 FEMA borrowed another $6.1 billion on November 9, 2017, to fund estimated 2017 losses, including those incurred by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria and anticipated programmatic activities, bringing the debt up to $20.525 billion. The NFIP currently has $9.9 billion of remaining borrowing authority.81

If there were to be a lapse in authorization on or after November 30, 2018, and the borrowing authority is reduced to $1 billion, FEMA would continue to adjust and pay claims as premium dollars come into the National Flood Insurance Fund (NFIF)82 and reserve fund. If the funds available to pay claims in the NFIF and the reserve fund were to be depleted, claims would have to wait until sufficient premium dollars were received to pay them unless Congress were to appropriate supplemental funds to the NFIP to pay claims or increase the borrowing limit. In the event that Congress does not provide funding to cover unpaid claims, policyholders might avail themselves of judicial remedies to recover these funds from the U.S. Treasury.83

The NFIP's debt is conceptually owed by current and future participants in the NFIP, as the insurance program itself owes the debt to the Treasury and pays for accruing interest on that debt through the premium revenues of policyholders.84 Under its current authorization, the only means the NFIP has to pay off the debt is through the accrual of premium revenues in excess of outgoing claims, and from payments made out of the reserve fund. For example, since the NFIP borrowed funds following the 2005 hurricane season, the NFIP has paid $2.82 billion in principal repayments and $3.83 billion in interest to service the debt through the premiums collected on insurance policies.85 In a recent report, GAO noted that charging current policyholders to pay for debt incurred in past years is contrary to actuarial principles and insurers' pricing practices; according to actuarial principles, a premium rate is based on the risk of future losses and does not include past costs.86 GAO also argued that this creates a potential inequality because policyholders are charged not only for the flood losses that they are expected to incur, but also for losses incurred by past policyholders.87

The cancellation of $16 billion of NFIP debt in October 2017 represents the first time that NFIP debt has been cancelled, although Congress appropriated funds between 1980 and 1985 to repay NFIP debt.88 Earlier in 2017, GAO had considered the option of eliminating FEMA's debt to the Treasury, suggesting that if the debt were eliminated, FEMA could reallocate funds used for debt repayment for other purposes such as building a reserve fund and program operations, and arguing that this would also be more equitable for current policyholders and consistent with actuarial principles.89 Eliminating the entire NFIP debt would require Congress to cancel debt outright, to appropriate funds for FEMA to repay the debt, or to change the law90 to eliminate the requirement that FEMA repay the accumulated debt.

No projections of the NFIP debt have yet been made that take account of the cancellation of $16 billion of NFIP debt or the, as yet unknown, total claims of the 2017 hurricane season. As required by law,91 FEMA submitted a report to Congress in 2013 on how the borrowed amount from the U.S. Treasury could be repaid within a 10-year period. This report indicated that in most realistic scenarios, the debt would not be paid off for at least 20 years, and that period could increase considerably with future catastrophic incidents.92 FEMA estimated in March 2017 that the NFIP's $24.6 billion debt would require annual interest-only payments of nearly $400 million, noting that if interest rates were to rise, these payments would increase significantly and FEMA might not be able to retire any of its debt, even in low loss years.93 In April 2017, FEMA updated some of the assumptions in the October 2015 NFIP Semi-Annual Debt Repayment Progress Report and estimated that at the end of 20 years, the NFIP's net debt would increase by a further $9.4 billion.94 Also in April 2017, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the NFIP would have insufficient receipts to pay the expected claims and expenses over the 2018-2027 period and that FEMA would need to use about $1 billion of its borrowing authority to pay those expected claims.95 Although the debt cancellation means that the 2017 hurricane season will probably not require an increase in the borrowing limit, the NFIP will have a debt very similar to the debt after the 2005 hurricane season. Since 2005, the program has devoted more resources to interest payments than to repaying the debt, and it seems unlikely that this would be different in the future without congressional action.

Provisions Related to NFIP Debt in Senate Bills

- S. 1368, Section 301, would freeze interest accrual on the NFIP's debt to the Treasury for six years after enactment. This would make it possible for the NFIP to spend saved amounts from foregone interest payments for a variety of other purposes.

Affordability of Flood Insurance

Some stakeholders have expressed concern related to the perceived affordability of flood insurance premiums and the balance between actuarial soundness and other goals of the NFIP.96 Particularly following the increase in premiums associated with BW-12 and HFIAA, concerns were raised that risk-based premiums could be unaffordable for some households. Section 100236 of BW-12 called for an affordability study by FEMA and also a study by the National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences (NRC) regarding participation in the NFIP and the affordability of premiums. In HFIAA Section 9, Congress also required FEMA to develop a Draft Affordability Framework "that proposes to address, via programmatic and regulatory changes, the issues of affordability of flood insurance sold under the National Flood Insurance Program, including issues identified in the affordability study…."97 FEMA published their Affordability Framework on April 17, 2018.98

The NRC report was published in two parts.99 The first NRC report considered the many ways in which to define affordability and identify which households need financial assistance with premiums. They noted that there are no objective definitions of affordability for flood insurance, nor is there an objective threshold that separates affordable premiums from unaffordable premiums and thus defines affordability either for an individual property owner or renter, or for any group of property owners or renters.100 They suggested that if affordability were to be addressed through some form of government assistance, a number of questions would need to be answered by Congress or FEMA: (1) Who will receive assistance? (2) What assistance will be provided? (3) How will assistance be provided? (4) How much assistance will be provided? (5) Who will pay for the assistance? (6) How will assistance be administered?101

The NRC report suggested that eligibility for assistance could be based on (1) being cost-burdened by flood insurance, (2) the loss of pre-FIRM subsidies or grandfathered cross-subsidies, (3) the requirement to purchase flood insurance, (4) housing tenure, (5) household income, (6) mitigation, or (7) community characteristics.102 The first NRC report identified potential policy measures that might reduce the burden of premium payments, or that might direct mitigation assistance towards households that qualify for assistance, such as means-tested mitigation grants, mitigation loans, means-tested vouchers, federal tax deductions and credits, disaster savings account, expanding the variety of individual mitigation measures that reduce premiums, encouraging the selection of higher premium deductibles, reducing NFIP administrative cost loadings in premiums, eliminating the mandatory purchase requirement, or relying on the Treasury to help pay claims in catastrophic loss years.103 The report concluded that policymakers will need to decide whether they want to define cost burden with reference to income, housing costs in relation to income, premium paid in relation to property value, or some other measure.104

GAO also considered the issue of affordability, suggesting that an affordability program that addresses the goals of encouraging consumer participation and promoting resilience would provide means-tested assistance through appropriations rather than through discounted premiums, and prioritize it to mitigate risk. They argued that providing premium assistance through appropriations rather than discounted premiums would address the policy goal of making the fiscal exposure more transparent because any affordability discounts on premium rates would be explicitly recognized in the budget each year.105 GAO suggested that linking subsidies to ability to pay rather than the existing approach to subsidies would make premium assistance more transparent and thus more open to oversight by Congress and the public. They also argued that means-testing premium assistance would help ensure that only those who could not afford full-risk rates would receive assistance, which could lower the number of policyholders receiving a subsidy and thus increase the amount that the NFIP receives in premiums and reduce the program's federal fiscal exposure. GAO estimated that 47%-74% of policyholders could be eligible for subsidy if income eligibility was set at 80% or 140% of area median income, respectively.106 GAO also suggested that instead of premium assistance, it would be preferable to address affordability by providing assistance for mitigation measures that would reduce the flood risk of the property, thus enhancing resilience, and ultimately result in a lower premium rate. Reducing flood risk through mitigation could also reduce the need for federal disaster assistance, further decreasing federal fiscal exposure.107

Another approach to making premiums affordable, at least for policyholders in the relevant communities, would be to introduce policies to increase the number of communities participating in the Community Rating System (CRS) or to encourage communities already participating in the CRS to improve their rating. The CRS is a program offered by FEMA to incentivize the reduction of flood and erosion risk, as well as the adoption of more effective measures to protect natural and beneficial floodplain functions.108 FEMA awards points that increase a community's "class" rating in the CRS. Policyholders in the SFHA within a CRS community receive a 5%-45% discount on their SFIP premiums, depending on their community's rating. In order to participate in the CRS program, a community must apply to FEMA and document its creditable improvements through site visits and assessments. As of June 2017, FEMA estimated that only 5% of eligible NFIP communities participate in the CRS program. However, these communities have a large number of flood policies, so more than 69% of all flood policies are written in CRS-participating NFIP communities.109 Although the CRS discount reduces flood insurance premiums for individual communities, the CRS discount is cross-subsidized into the NFIP program, such that the discount for one community ends up being offset by increased premium rates in all communities across the NFIP. For example, the average 11.4% discount for CRS communities in April 2014 was cross-subsidized and shared across NFIP communities through a cost (or load) increase of 13.4% to overall premiums.110

FEMA does not currently have the authority to implement an affordability program, nor does FEMA's current rate structure provide the funding required to support an affordability program. If an affordability program were to be funded from NFIP funds, this would require either raising flood insurance rates for NFIP policyholders or diverting resources from another existing use. Alternatively, an affordability program could be funded fully or partially by congressional appropriation.

Provisions Related to Affordability in H.R. 2874

- Section 103 would authorize a state or a consortium of states to create a voluntary flood insurance affordability program for owner-occupants of 1-4 unit residences in communities participating in the NFIP. Eligibility would be determined by the state, but the affordability program would not be available to a household with income that exceeds the greater of (i) the amount equal to 150% of the poverty level for each state, or (ii) the amount equal to 60% of the median income of households residing in the state. Assistance could be only in the form of either establishing a limit on the amount of chargeable risk premium paid or limiting the rate of increase in the amount of chargeable premiums. The state affordability program would be funded through a surcharge on each policy within that state that is not eligible to participate in the affordability program. Because this approach to affordability would be funded by other NFIP policyholders, it would create a new cross-subsidy within the NFIP for any states that develop an affordability program. Because the affordability assistance is limited to single-family owner-occupiers, this surcharge could potentially be levied on policyholders with equally low, or lower incomes, who are renters with contents-only policies, or owner-occupiers who live in multiunit buildings.

Provisions Related to Affordability in Senate Bills

- S. 1313, Section 208, would provide affordability vouchers for owner-occupied households with NFIP policies in SFHAs with income less than 165% of area median income and for which the cost of flood insurance premiums, surcharges, and fees would result in excess costs for that year. Excess costs are defined as when the sum of the total amount of NFIP premiums, surcharges and fees plus the annual housing expenses exceed 40% of the total household income for the year. The voucher would offset excess costs and would be used towards payment of flood insurance premiums, surcharges, and fees. Policyholders with household incomes below 80% of the area median income would receive a voucher for 100% of the excess costs. Policyholders with household incomes of 81%-120% of area median income would receive vouchers for 80% of excess costs, and policyholders with household incomes of 121%-165% of area median income would receive vouchers for 60% of excess costs. It is unclear how these vouchers would be funded.

- S. 1368, Section 103, would require FEMA to establish an Affordability Assistance Fund which would be separate from other NFIP funds and available without fiscal year limitation. This Affordability Assistance Fund would be credited with the income from the HFIAA surcharge. Section 103 would require FEMA to offer zero or low-interest loans to fund mitigation projects by homeowners, and would also require FEMA to provide financial assistance in the form of a voucher, grant, or premium credit to an eligible household, defined as one where housing costs exceed 30% of the household's adjusted gross income for the year and the total assets owned by the household are not greater than $1 million. The voucher, grant or premium credit would provide an amount equal to the lesser of the difference between either the annual housing expenses or 30% of the annual adjusted gross income of the household and the costs of NFIP premiums plus principal and interest payments for a loan provided under this section.

Increasing Participation in the NFIP

A long-standing objective of the NFIP has been to increase purchases of flood insurance policies, and this objective of widespread NFIP purchase was one motivation for keeping NFIP premiums reasonable111 and for later introducing the requirement to purchase flood insurance as a condition of receiving a federally backed mortgage for properties in a SFHA, commonly referred to as the mandatory purchase requirement. Early in the program, the federal government found that making insurance available, even at subsidized rates, did not provide sufficient incentive for communities to join the NFIP or for individuals to purchase flood insurance. In response, Congress passed the Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973,112 which required the purchase of flood insurance and placed the responsibility for ensuring compliance on lending institutions. This mandatory purchase requirement was later strengthened by the National Flood Insurance Reform Act of 1994.113

In a community that participates or has participated in the NFIP, owners of properties in the mapped SFHA are required to purchase flood insurance as a condition of receiving a federally backed mortgage. By law and regulation, federal agencies, federally regulated lending institutions, and government-sponsored enterprises (GSE)114 must require these property owners to purchase flood insurance as a condition of any mortgage that these entities make, guarantee, or purchase.115 However, there are no official statistics available from the federal mortgage regulators responsible for compliance with the mandate, and no up-to-date data on national compliance rates with the mandatory purchase requirement. A 2006 study commissioned by FEMA found that compliance with this mandatory purchase requirement may be as low as 43% in some areas of the country (the Midwest), and as high as 88% in others (the West).116 A more recent study of flood insurance in New York City found that compliance with the mandatory purchase requirement by properties in the SFHA with mortgages increased from 61% in 2012 to 73% in 2016.117 The escrowing of insurance premiums, which began in January 2016, may increase compliance with the mandatory purchase requirement more widely, but no data are yet available.

Both the GAO and the NFIP report to Congress on options for privatizing the NFIP118 suggested that the mandatory purchase requirement could potentially be expanded to more (or all) mortgage loans made by federally regulated lending institutions for properties in communities participating in the NFIP. This would increase the consumer participation rate in the NFIP and potentially balance the NFIP portfolio with an increased number of lower risk properties.119 According to GAO, some private insurers have indicated that a federal mandate could help achieve the level of consumer participation necessary to make the private sector comfortable with providing flood insurance coverage by increasing the number of policyholders, which would allow private insurers to diversify and manage the risk of their flood insurance portfolio and address concerns about adverse selection.120 The Association of State Floodplain Managers also suggested that all properties within the SFHA should be required to have flood insurance, not just those with federally backed mortgages.121

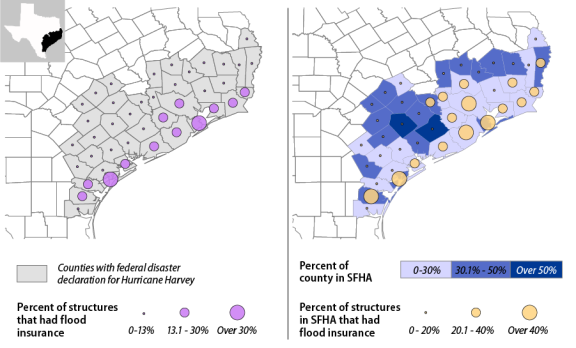

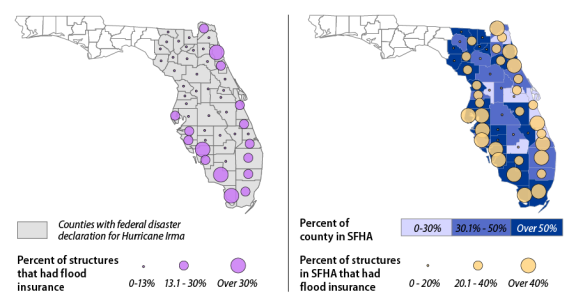

The flooding caused by the 2017 hurricanes highlighted the issue of low penetration rates122 of flood insurance. In the counties in Texas with a FEMA Individual Assistance declaration123 for Hurricane Harvey, the average penetration rate for all 41 counties was 10%, with a 21% penetration rate for structures within the SFHA in those counties. The counties with the highest penetration rate were on the coast (see Figure 1): Aransas County (72% penetration in SFHA, 43% penetration county-wide), Nueces County (70% in SFHA, 21% county-wide), and Galveston County (64% in SFHA, 47% county-wide). In the counties in Florida with a FEMA Individual Assistance declaration124 for Hurricane Irma, the average penetration rate for all 48 counties was 12%, with a 31% penetration rate for structures within the SFHA in those counties. The counties with the highest penetration rate (see Figure 2) were St. Johns County (73% in SFHA, 35% county-wide), Flagler County (72% in SFHA, 18% county-wide), Nassau County (62% in SFHA, 25% county-wide), and Palm Beach County (62% in SFHA, 22% county-wide). NFIP penetration rates were extremely low in Puerto Rico, with only 4,436 NFIP residential policies at the time Hurricane Maria hit, for an average penetration rate of 0.23%, and in the Virgin Islands, with only 1,412 NFIP policies, for an average penetration rate of 2.5%.125

NFIP policies are not distributed evenly around the country; about 37% of the policies are in Florida, with 11% in Texas and 9% in Louisiana, followed by California with 5% and New Jersey with 4%. These five states account for approximately 66% of all of the policies in the NFIP.126 NFIP participation rates are higher in coastal locations than in inland locations, and are highest in the most risky areas due to mandatory purchase requirements.127 The NFIP could potentially be financially improved with a more geographically diverse policy base and, in particular, through finding ways to increase coverage in areas perceived to be at lower risk of flooding than those in the SFHA.

FEMA has identified the need to increase flood insurance coverage across the nation as a major priority for the current reauthorization and beyond, and has set a goal of doubling flood insurance coverage by 2023, through the increased sale of both NFIP and private policies.128 Closing the insurance gap is one of the key strategic objectives of FEMA's 2018-2022 strategic plan.129

Provisions Related to Increasing NFIP Participation in H.R. 2874

- Section 507 would increase the civil penalties from $2,000 to $5,000 on federally regulated lenders for failure to comply with enforcing the mandatory purchase requirement. In addition, the federal entities for lending regulations, in consultation with FEMA, would be required jointly to update and reissue the guidelines on compliance with mandatory purchase.

- Section 513 would require a report by GAO on the implementation and efficacy of the mandatory purchase requirement within 18 months of enactment.

Provisions Related to Increasing NFIP Participation in Senate Bills

- S. 1313, Section 102, would require FEMA to conduct a study in coordination with the National Association of Insurance Commissioners to address how to increase participation in flood insurance coverage through programmatic and regulatory changes, and report to Congress no later than 18 months after enactment. This study would be required to include but not be limited to options to (1) expand coverage beyond the SFHA to areas of moderate flood risk; (2) automatically enroll customers in flood insurance while providing customers the opportunity to decline enrollment; and (3) create bundled flood insurance coverage that diversifies risk across multiple peril insurance.

- S. 1368, Section 410, would require FEMA to conduct a study and report to Congress within one year of enactment on the percentages of properties with federally backed mortgages located in SFHAs satisfy the mandatory purchase requirement, and the percentage of properties with federally backed mortgages located in the 500-year floodplain that would satisfy the mandatory purchase requirement if the mandatory purchase requirement applied to such properties.

- S. 1571, Section 303, would require the federal banking regulators to conduct an annual study regarding the rate at which persons who are subject to the mandatory purchase requirement are complying with that requirement. Section 303 would also require FEMA to conduct an annual study of participation rates and financial assistance to individuals who live in areas outside SFHAs.

The Role of Private Insurance in U.S. Flood Coverage

One of the reasons that the NFIP was originally created was because private flood insurance was widely unavailable in the United States.130 Generally, private companies could not profitably provide flood coverage at a price that consumers could afford, primarily because of the catastrophic nature of flooding and the difficulty of determining accurate rates.131 Until recently the role of the private market in primary residential flood insurance has been relatively limited. The main role of private insurance companies at the moment is in the operational aspect of the NFIP. FEMA provides the overarching management and oversight of the NFIP, and retains the actual financial risk of paying claims for the policy (i.e., underwrites the policy). However, the bulk of the day-to-day operation of the NFIP, including the marketing, sale, writing, and claims management of policies, is handled by private companies. The arrangement between the NFIP and private industry is authorized by statute and guided by regulation.132

There are two different arrangements that FEMA has established with private industry. The first is the Direct Servicing Agent (DSA), which operates as a private contractor on behalf of FEMA for individuals seeking to purchase flood insurance policies directly from the NFIP.133 The DSA also handles the policies of severe repetitive loss properties. The second arrangement is called the Write-Your-Own (WYO) Program, where private insurance companies are paid to write and service the policies themselves. Roughly 86% of NFIP policies are sold by the private insurance companies participating in the WYO Program.134 Companies participating in the WYO program are compensated through a variety of methods.135 Some have argued that the levels of WYO compensation are too generous, while others have argued that reimbursement levels are insufficient to cover all expenses associated with servicing flood policies under the procedures set by FEMA.136 A GAO study found that FEMA does not systematically consider actual flood expenses and profits when establishing WYO compensation, and has yet to compare WYO companies' actual expenses and compensation. Therefore, FEMA lacks the data to determine how much profit WYO companies make and whether the compensation payments are appropriate.137

In addition to the WYO program, there is a small private flood insurance market which most commonly provides commercial coverage, coverage above the NFIP maximums, or coverage in the lender-placed market.138 In general, the private flood market tends to focus on high-value properties, which command higher premiums and therefore the extra expense of flood underwriting can be more readily justified.139 At the moment very few private insurers compete with the NFIP in the primary voluntary flood insurance market. Some suggest that this is partly because the non-compete clause—the contractual restriction140 placed on WYO carriers against offering standalone private flood products that compete with the NFIP—curtails the potential involvement of the WYO companies.141 However, FEMA has announced proposed changes for FY2019 in which they would remove restrictions on WYO companies choosing to offer private flood insurance, while maintaining requirements that such private insurance lines remain entirely separate from a WYO company's NFIP insurance business.142 If implemented, this would effectively remove the non-compete clause without need for legislation.

Barriers to Private Sector Involvement

Private insurer interest in providing flood coverage has increased in recent years. Advances in the analytics and data used to quantify flood risk mean that a number of private insurance companies and insurance industry organizations have expressed interest in private insurers offering primary flood insurance in competition with the NFIP. Private insurance is seen by many as a way of transferring flood risk from the federal government to the private sector.

A reformed NFIP rate structure could have the effect of encouraging more private insurers to enter the primary flood market; FEMA's subsidized rates are often seen as the primary barrier to private sector involvement in flood insurance.143 Even without the subsidies mandated by law, the NFIP's definition of full-risk rates differs from that of private insurers. Whereas the NFIP's full-risk rates must incorporate expected losses and operating costs, a private insurer's full-risk rates must also incorporate a return on capital. As a result, even those NFIP policies which are considered to be actuarially sound from the perspective of the NFIP may still be underpriced from the perspective of private insurers.144

The rules on the acceptance of private insurance for the mandatory purchase requirement have had a significant impact on the market potential for private insurers. In BW-12, Congress explicitly allowed federal agencies to accept private flood insurance to fulfill the mandatory purchase mortgage requirement as long as the private flood insurance "provides flood insurance coverage which is at least as broad as the coverage" of the NFIP, among other conditions.145 The implementation of this requirement has proved challenging, with the responsible federal agencies issuing two separate Notices of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) addressing the issue in October 2013146 and November 2016.147 The crux of the implementation issue may be seen as answering the question of who would judge whether specific policies met the "at least as broad as" standard and what criteria would be used in making this judgment. The uncertainty about whether or not private policies would meet this standard has been viewed as a barrier to private sector participation in the flood insurance market, along with FEMA's policy on continuous coverage.148 Continuous coverage is required for property owners to retain any subsidies or cross-subsidies in their NFIP premium rates. A borrower may be reluctant to purchase private insurance if doing so means they would lose their subsidy should they later decide to return to NFIP coverage.

Many insurers also view the lack of access to NFIP data on flood losses and claims as a barrier to more private companies offering flood insurance. It is argued that increasing access to past NFIP claims data would allow private insurance companies to better estimate future losses and price flood insurance premiums, and ultimately to determine which properties they might be willing to insure.149 However, FEMA's view is that the agency would need to address privacy concerns in order to provide property level information to insurers, because the Privacy Act of 1974150 prohibits FEMA from releasing policy and claims data which contains personally identifiable information.

Potential Effects of Increased Private Sector Involvement on the NFIP

Private sector competition might increase the financial exposure and volatility of the NFIP, as private markets will likely seek out policies that offer the greatest likelihood of profit. In the most extreme case, the private market may "cherry-pick" (i.e., adversely select) the profitable, lower-risk NFIP policies that are "overpriced" either due to cross-subsidization or imprecise flood insurance rate structures.151 This could leave the NFIP with a higher density of actuarially unsound policies that are being directly subsidized or benefiting from cross-subsidization. Because the NFIP cannot refuse to write a policy, those properties that are considered "undesirable" by private insurers are likely to remain in the NFIP portfolio—private insurers will not compete against the NFIP for policies that are inadequately priced from their perspective.152 Private insurers, as profit-seeking entities, are unlikely to independently price flood insurance policies in a way that ensures affordable premiums as a purposeful goal, although some private policies could be less expensive than NFIP policies. It is likely that the NFIP would be left with a higher proportion of subsidized policies, which may become less viable in a competitive market.153

Any significant increase in private insurer writing that "depopulates" the NFIP may undermine the NFIP's ability to generate revenue, reducing the amount of borrowing that can be repaid or extending the time required to repay the debt. As the number of NFIP policies decreases, it may become increasingly difficult for the remaining NFIP policyholders to subsidize policies and repay NFIP debt. In the long term the program could be left as a residual market for subsidized or high-risk properties. While this may be a valid policy choice, a likely consequence is that the NFIP as a residual market would not be financially self-sustaining and would require support from the federal government in some form.154

If the number of NFIP policyholders were to decrease significantly, it might also be difficult to support the NFIP's non-insurance functions of reducing flood risk through floodplain management and mapping. Enforcement of flood mitigation standards could be more challenging within a private flood insurance system, as the current system makes the availability of NFIP insurance in a community contingent on the implementation of floodplain management standards. However, government investment in mitigation could increase private market participation by reducing the flood exposure of high risk properties and thereby increasing the number of properties that private insurers would be willing to cover.155 The Association of State Floodplain Managers (ASFPM) has expressed concerns that the widespread availability of private flood insurance could lead some communities to drop out of the NFIP and rescind some of the floodplain management standards and codes they had adopted, leading to more at-risk development in flood hazard areas.156 ASFPM suggested that this issue could be addressed by allowing private policies to meet the mandatory purchase requirement only if they were sold in participating NFIP communities.157

Reinsurance

In HFIAA, Congress revised the authority of FEMA to secure reinsurance for the NFIP from the private reinsurance and capital markets.158 In January 2017, FEMA purchased $1.042 billion of insurance, to cover the period from January 1, 2017, to January 1, 2018, for a reinsurance premium of $150 million. Under this agreement, the reinsurance covers 26% of losses between $4 billion and $8 billion arising from a single flooding event.159 Although it is too early to estimate the total claims, FEMA has so far paid over $8.6 billion in claims for Hurricane Harvey, triggering the 2017 reinsurance.160 In January 2018, FEMA purchased $1.46 billion of insurance to cover the period from January 1, 2018, to January 1, 2019, for a reinsurance premium of $235 million. The agreement is structured to cover losses above $4 billion for a single flooding event, covering 18.6% of losses between $4 billion and $6 billion, and 54.3% of losses between $6 billion and $8 billion.161 In April 2018, FEMA announced that it would seek to transfer additional NFIP risk to private markets through a reinsurance procurement in which the reinsurer acts as a transformer to transfer NFIP-insured flood risk through the issuance of a catastrophe bond, to be effective for a term of "likely" three years.162

The purchase of private market reinsurance reduces the likelihood of FEMA needing to borrow from the Treasury to pay claims. In addition, as GAO noted, reinsurance could be beneficial because it allows FEMA to recognize some of its flood risk and the associated risk up front through the premiums it pays to the reinsurers rather than after the fact borrowing from Treasury. From a risk management perspective, using reinsurance to cover losses in only the more extreme years could help the government to manage and reduce the volatility of its losses over time. However, because reinsurers understandably charge FEMA premiums to compensate for the risk they assume, the primary benefit of reinsurance is to transfer and manage risk rather than to reduce the NFIP's long-term fiscal exposure.163 For example, a reinsurance scenario which would provide the NFIP with $16.8 billion coverage (sufficient for Katrina-level losses) could cost an estimated $2.2 billion per year.164 However, the NFIP's finances do not offer room for expenditure of this amount on reinsurance, as the current premium income is only about $3.5 billion per year, and most of that is required to pay claims.

Provisions Related to Private Insurance in H.R. 2874

- Section 201 would revise the definition of private flood insurance previously defined in BW-12. This section would strike existing statutory language describing how private flood insurance must provide coverage "as broad as the coverage" provided by the NFIP. Instead, the definition would rely on whether the insurance policy and insurance company were in compliance in the individual state (as defined to include certain territories and the District of Columbia). Further, "private flood insurance" would be specifically defined as including surplus lines insurance.165 Though the majority of regulation of private flood insurance would then rest with individual states, federal regulators166 would be required to develop and implement requirements relating to the financial strength of private insurance companies from which such entities and agencies will accept private insurance, provided that such requirements shall not affect or conflict with any state law, regulation, or procedure concerning the regulation of the business of insurance. The dollar amount of coverage would still have to meet federal statutory requirements and the GSEs may implement requirements relating to the financial strength of such companies offering flood insurance. This section would also specify that if a property owner purchases private flood insurance and decides then to return to the NFIP, they would be considered to have maintained continuous coverage. This section would allow private insurers to offer policies that provide coverage that might differ significantly from NFIP coverage, either by providing greater coverage or potentially providing reduced coverage that could leave policyholders exposed after a flood.

- Section 202 would apply the mandatory purchase requirement only to residential improved real estate, thereby eliminating the requirement for other types of properties (e.g., all commercial properties) to purchase flood insurance from January 1, 2019. This would likely affect the policy base of the NFIP by reducing the number of commercial properties covered.167 However, it is uncertain how many would elect to forgo insurance coverage (public or private) entirely. To the extent that commercial properties no longer choose to carry insurance (or are allowed to do so by the conditions of their mortgages), there may be increased uninsured damages to these properties from floods.

- Section 203 would eliminate the non-compete requirement in the WYO arrangement with FEMA that currently restricts WYO companies from selling both NFIP and private flood insurance policies. This would allow the WYO companies to offer their own insurance policies while also receiving reimbursement for their participation in the WYO Program to administer the NFIP policies. It is unknown what criteria WYO companies would use to establish their own policies, and how they would choose to offer those policies rather than NFIP policies to potential customers.

- Section 204 would require FEMA to make publicly available all data, models, assessments, analytical tools, and other information that is used to assess flood risk or identify and establish flood elevations and premiums. This section would also require FEMA to develop an open-source data system by which all information required to be made publicly available may be accessed by the public on an immediate basis by electronic means. Within 12 months after enactment, FEMA would be required to establish and maintain a publicly searchable database that provides information about each community participating in the NFIP. This section provides that personally identifiable information would not be made available; the information provided would be based on data that identifies properties at the zip code or census block level. Ultimately, this data could be used to better inform the participation of private insurers in offering private flood insurance, as well as informing future flood mitigation efforts. However, the availability of NFIP data could make it easier for private insurers to identify the NFIP policies that are "overpriced" due to explicit cross-subsidization or imprecise flood insurance rate structures, and adversely select these properties, while the government would likely retain those policies that benefit from those subsidies and imprecisions, potentially increasing the deficit of the NFIP.168

- Section 506 would establish that the allowance paid to WYO companies would not be greater than 27.9% of the chargeable premium for such coverage. It would also require FEMA to reduce the cost of companies participating in the WYO program.

- Section 511 would require annual transfer of a portion of the risk of the NFIP to the private reinsurance or capital markets to cover a FEMA-determined probable maximum loss target that is expected to occur in the fiscal year, no later than 18 months after enactment.

Provisions Related to Private Insurance in Senate Bills

- S. 1313, Section 101, would require annual transfer of a portion of the risk of the NFIP to the private reinsurance or capital markets in an amount that is sufficient to maintain the ability of the program to pay claims, and limit the exposure of the NFIP to potential catastrophic losses from extreme events.

- S. 1313, Section 401, would allow any state-approved private insurance to satisfy the mandatory purchase requirement, and allow private flood insurance to count as continuous coverage. This section would also change the amount of insurance required169 for both private flood insurance policies and NFIP policies in order to satisfy the mandatory purchase requirement. The required coverage would be the lesser of 80% of the purchase price of the property, the maximum NFIP coverage for that type of property, or the outstanding balance of the loan (for multiunit structures only). This section would require FEMA, within two years of enactment, to report on the extent to which the properties for which private flood insurance is purchased tend to be at a lower risk than properties for which NFIP policies are purchased (i.e., the extent of adverse selection), by detailing the risk classifications of the private flood insurance policies. This data, while identifying adverse selection based on risk profiles, might not identify if there has been adverse selection based on subsidization.

- S. 1313, Section 402, would give temporary authority for sale of private flood insurance by WYO companies for certain properties during the first two years after enactment (e.g., non-residential properties, severe repetitive loss properties, business properties, or any property that has incurred flood-related damage in which the cumulative amount of payments equaled or exceeded the fair market value of the property).170 After two years and on completion of a study measuring the risk classification underwritten by participating WYO companies, if the FEMA Administrator determines that the provision of flood insurance to properties in addition to those categories above will not adversely impact the ability of the NFIP to maintain a diverse risk pool, the Administrator is authorized to expand (or limit) the participation of WYO companies in the broader flood insurance marketplace.

- S. 1313, Section 403, would require FEMA to study the feasibility of selling or licensing the use of historical structure-specific NFIP claims data to non-governmental entities, while reasonably protecting policyholder privacy, and report within a year of enactment. This section would also authorize FEMA to sell or license claims data as the Administrator determines is appropriate and in the public interest, with the proceeds to be deposited in the National Flood Insurance Fund.

- S. 1313, Section 602, would require FEMA, not later than one year from enactment, to create and maintain a publicly searchable database that includes the aggregate number of claims filed each month, by state; the aggregate number of claims paid in part or in full; and the aggregate number of claims denials appealed, denials upheld on appeal, and denials overturned on appeal; without making personally identifiable information available.

- S. 1368, Section 302, would establish that the total amount of reimbursement paid to WYO companies would not be greater than 22.46% of the chargeable premium for such coverage.

- S. 1368, Section 304, would require FEMA, within 12 months of enactment, to develop a schedule to determine the actual costs of WYO companies, including claims adjusters and engineering companies, and reimburse the WYO companies only for the actual costs of the service or products.

- S. 1571, Section 302, would specify that FEMA may consider any form of risk transfer, including traditional reinsurance, catastrophe bonds, collateralized reinsurance, resilience bonds, and other insurance-linked securities.

Properties with Multiple Losses

An area of controversy involves NFIP coverage of properties that have suffered multiple flood losses, which are at greater risk than the average property insured by the NFIP. One concern is the cost to the program; another is whether the NFIP should continue to insure properties that are likely to have further losses.171 The NFIP currently uses more than one definition of repetitive loss. The statutory definition of a repetitive loss structure172 is used for applications for Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) grants. A slightly different definition is used for Increased Cost of Compliance Coverage,173 and a third definition is used for internal tracking of insurance data and also for the Community Rating System.174 The statutory definition of a severe repetitive loss property is a property which has incurred four or more claim payments exceeding $5,000 each, with a cumulative amount of such payments over $20,000; or at least two claims with a cumulative total exceeding the value of the property.175 The definition of severe repetitive loss property is consistent across program elements in the NFIP.

According to FEMA, repetitive loss (RL) and severe repetitive loss (SRL) properties account for approximately $17 billion in claims, or approximately 30% of total claims over the history of the program. As of January 31, 2017, there were 90,000 currently insured repetitive loss properties and 11,000 currently insured severe repetitive loss properties. The currently insured repetitive loss and severe repetitive loss properties (which represent about 2% of the overall policies in the NFIP) have accounted for approximately $9 billion in claims, or approximately 16% of total claims over the history of the program.176 A study of all of the residential NFIP claims filed between January 1978 and December 2012 showed that the magnitude of claims for repetitive loss structures as a percentage of building value was higher than non-repetitive loss properties by 5%-20%.177

Provisions Related to Multiple-Loss Properties in H.R. 2874

- Section 402 would require certain NFIP communities with a history of flood loss to identify where repeatedly flooded properties are located and assess the continuing risks to such areas and develop a community-specific plan for mitigating flood risks in these areas or face possible sanctions from FEMA. Covered communities include those which participate in the NFIP within which such properties are located: (i) 50 or more repetitive loss structures178 for each of which, during any 10-year period, two or more claims for payment under flood insurance coverage have been made with a cumulative amount exceeding $1,000; (ii) five or more severe repetitive loss structures for which mitigation activities have not been conducted; or (iii) a public facility or a private nonprofit facility that has received assistance for repair, restoration, reconstruction, or replacement under Section 406 of the Stafford Act (P.L. 93-288)179 in connection with more than one flooding event in the most recent 10-year period. To assist communities in the preparation of plans, FEMA would be required to provide covered communities with appropriate data regarding property addresses and dates of claims associated with insured properties within the community. Before sanctioning a community for not fulfilling the requirements of this section, FEMA would be required to issue notice of noncompliance before sanctions and recommendations for actions to bring the community into compliance. FEMA would also be required to consider the resources available to the community affected, including federal funding, the portion of the community that lies within the SFHA, and other factors that make it difficult for the community to conduct mitigation activities for existing flood-prone structures. FEMA would be required to develop sanctions in future regulations. In making determinations regarding financial assistance for mitigation, FEMA may consider the extent to which a community has complied with this subsection. Although a community may incorporate plans required under this section into flood mitigation plans180 or hazard mitigation plans,181 which they may already be required to complete, covered communities may feel that this section imposes significant additional requirements.