Introduction

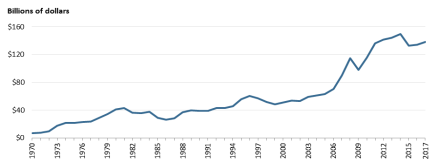

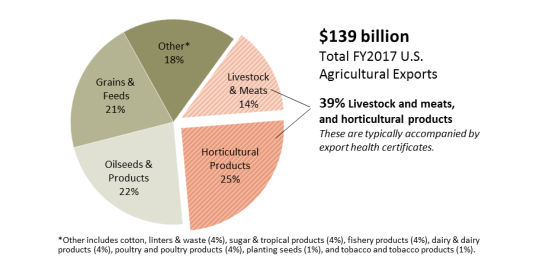

The United States exports agricultural products to nearly every country in the world. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reports that U.S. agricultural exports reached nearly $139 billion in FY2017 (Figure 1).1 To successfully ship agricultural products, exporters must conform to importer requirements. USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is the U.S. government authority tasked with regulating most animal and plant product exports. Export health certificates are commonly necessary for the export of horticultural products (e.g., fruits and vegetables) and livestock, which represent over one-third ($53 billion)2 of U.S. agricultural exports in FY2017 (Figure 2). APHIS is also responsible for informing the international community of U.S. animal or plant disease outbreaks.

|

Figure 1. Total U.S. Agricultural Exports, FY1970-FY2017 Values have not been adjusted for inflation. |

|

|

Source: USDA, GATS, and U.S. Census Bureau trade data. Date accessed: 3/30/2018. |

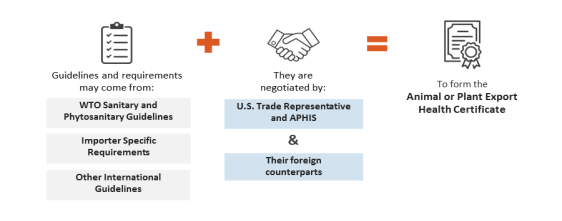

To meet the health standards required by U.S. trading partners, APHIS and other U.S. federal agencies negotiate "export health certificates" with each partner country (Figure 3). Export health certificates are also part of broader agreements between the United States and its trading partners on the World Trade Organization's (WTO) established "sanitary and phytosanitary" (SPS) measures. These measures protect against diseases, pests, toxins, and other contaminants. APHIS technical personnel, often working with other federal agencies, negotiate with their foreign counterparts on SPS measures. APHIS maintains a public website with import requirements by product and country to assist U.S exporters.3 Without these certificates, shipments could be delayed or rejected.4 Neither APHIS nor any other U.S. agency enforces or requires the usage of export health certificates, but failure to obtain an importer-required specific certificate would likely lead to a rejected shipment by the importing country.

This report discusses APHIS's role in export health certificate issuance to facilitate agricultural trade. APHIS is not the sole issuer of export health certificates; many food and agricultural products (i.e., that are not horticultural products or livestock) have oversight by other federal agencies that are outside the scope of this report.

|

|

Source: USDA, GATS, and U.S. Census Bureau trade data. Date accessed: 3/30/2018. |

|

Figure 3. Components Included in Animal or Plant Export Health Certificates |

|

|

Source: CRS. Notes: WTO = World Trade Organization. APHIS= Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. |

|

Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Measures SPS measures are the rules that protect against diseases, pests, toxins, and other contaminants. Examples include specific product or processing standards, requirements for products to be produced in disease-free areas, quarantine and inspection procedures, sampling and testing requirements, residue limits for pesticides and drugs in foods, and prohibitions on certain food additives. Export health certificates follow international SPS measures established by the WTO. The WTO recognizes the right of countries to maintain standards that are stricter than international standards. However, the WTO recommends that stricter import standards should be justified by science or by a nondiscriminatory lower level of acceptable risk that does not selectively target imports. For more information, see CRS Report R43450, Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) and Related Non-Tariff Barriers to Agricultural Trade. |

Commodity Jurisdiction

Many of the U.S. agricultural and food products for export fall under APHIS's jurisdiction. An APHIS export health certificate informs the importing country that the U.S. product is free of certain diseases, and it includes additional information required by the importer.

In FY2017, APHIS issued close to 675,000 federal export health certificates for international agricultural shipments.5 APHIS manages programs on a national basis through two regional offices and 433 field offices.6 APHIS performs work in all U.S. states and territories, Mexico, Central America, South America, the Caribbean, Western Europe, Asia, and Africa.

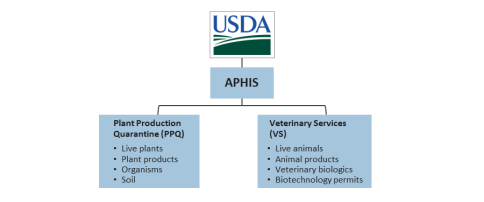

In particular, APHIS has jurisdiction over the following agricultural products:

- Live animals, animal products, veterinary biologics (vaccines, bacterins,7 antisera,8 diagnostic kits, and other products of biological origin), and biotechnology permits for genetically engineered organisms.

- Live plants, plant products (nursery stock; small lots of seed; fruits and vegetables; timber; cotton; cut flowers; and protected, threatened, and endangered plants), organisms (arthropods and mollusks, fungi, bacteria, nematodes, mycoplasma, viroids and viruses, biological control agents, bees, Plant Pest Diagnostic Laboratories, federal noxious weeds,9 and parasitic plants), and soil.

APHIS is not the only issuer of export health certificates. For example, the Department of Commerce has jurisdiction over the administration of health certificates for fish and seafood. A listing of agencies and their commodity responsibilities is provided in Table 1.

|

Department |

Agency and Commodity Jurisdiction |

|

|

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service |

Export Health Certificate:

|

|

Food Safety and Inspection Service |

Export Certificate of Wholesomeness:

|

|

|

Agricultural Marketing Service |

Export Verification Programs:

|

|

|

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

Food and Drug Administration |

Certificate of Free Sale:

|

|

U.S. Department of Commerce |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

Export Health Certification:

|

Source: CRS, using information from CRS Report RS22600, The Federal Food Safety System: A Primer.

Notes: Processed eggs are used in baking or other processed foods. Hatching eggs are live avian commodities (eggs) that require a controlled environment and take roughly 21 days to hatch.

A number of other agencies, not included in this table, issue export certificates for certain niche agricultural or food products.

Depending on a trade agreement's SPS chapter, more than one type of certificate could accompany a particular agricultural product. For example, an importing country may require two certificates from a U.S. exporter of hatching eggs,10 including one requiring the exporter to participate in the Agricultural Marketing Service's "export verification program" and a second requiring the exporter to obtain an APHIS export health certificate.

Other Certificates and Programs

APHIS export health certificates do not apply to certain food and agricultural products. Table 1 introduces the commodity jurisdictions and the types of attestation other federal agencies provide to U.S. exporters. The following list describes the most common types of certificates and programs—outside of the APHIS export health certificates—that facilitate agricultural exports.

- 1. Certificate of Free Sale. The Department of Health and Human Services' Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has jurisdiction over a wide range of food products. FDA provides an importing country with a Certificates of Free Sale to meet the requirements regarding a product's regulatory or marketing status.11 FDA issues this certificate for conventional foods for human consumption, dietary supplements, infant formula, medical foods,12 and foods for special dietary use.

- 2. Export Certificate of Wholesomeness. USDA's Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) issues13 Export Certificates of Wholesomeness14 for meat, poultry, and egg products that are exported from the United States. These certificates verify that the accompanying products have been inspected by FSIS at official FSIS slaughter and processing establishments and approved cold storage facilities.15

- 3. Export Verification (EV) Program. USDA's Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) reviews and approves companies as eligible suppliers of certain products for export under the USDA EV Programs.16 The EV Program outlines the specified product requirements for individual countries that must be met through an approved Quality System Assessment Program.17 Only eligible suppliers may supply products for the applicable EV Program. Eligible products must be produced under an approved EV Program.

Other USDA programs not discussed in this report also support U.S. agricultural exports including export promotion and financing programs. For more information, see CRS Report R44985, USDA Export Market Development and Export Credit Programs: Selected Issues.

Memoranda of Understanding (MOU)

It is common for federal agencies to write memoranda of understanding (MOU) to facilitate cooperation among federal agencies to better support U.S. exports. For example, in 2008 the Department of Commerce's National Marine Fisheries Service—housed within National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)—and the Department of the Interior's Fish and Wildlife Service entered into an MOU with APHIS to recognize the legal authorities and mandates for the management of aquatic animal health.18 In this case, all three of the agencies have the ability to endorse export health certificates for aquatic animals.19 This MOU describes the responsibilities of each agency and clarifies that they may request assistance from one another upon issuing an export health certificate from within their respective legal jurisdictions. Further, the MOU states that all three agencies have authority to attest to the health and pathogen status of the aquatic animals to be exported as required by an importing country.

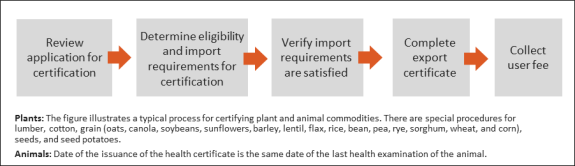

Obtaining a Plant or Animal Health Certificate

An exporter must collaborate with APHIS to obtain a plant or animal export health certificate. APHIS's Plant Production Quarantine (PPQ) and Veterinary Services (VS) oversee the health certificate endorsement process for a "plant health certificate" or "animal health certificate," respectively (Figure 4). APHIS cooperates with many federal agencies, including AMS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Customs and Border Protection, Fish and Wildlife Service, FDA, and FSIS to facilitate the verification process (Figure 5).

|

|

Source: CRS, using information from APHIS, Export Program Manual and Animal Product Manual. |

|

Figure 5. Summary of the Plant or Animal Export Health Certification Process |

|

|

Source: CRS using information from APHIS, Export Program Manual and Animal Product Manual. |

Plant Health Certificates

PPQ is the U.S. government authority that issues export plant heath certificates20 for plants, bulbs and tubers, seeds for propagation, fruits and vegetables, cut flowers and branches, grain, and growing medium.21 PPQ's plant health attestation assists exporters in meeting the importers' food safety requirements. The process of obtaining an export plant health certificate requires cooperation between the exporter and PPQ as follows:

- 1. The exporter must submit an application to PPQ.22

- 2. PPQ technical staff performs specific tests on the plant products and determines certification based on country-specific import requirements.23

- 3. After PPQ verifies the import requirements, the exporter receives a completed export certificate and pays a fee for the service.

If the exporter provides PPQ with all of the necessary information, an exporter may receive APHIS's endorsement (digitally or in hard copy) within a few days. Export certificates are to be issued within 30 days of the phytosanitary inspection.24

Animal Health Certificates

VS is the authority for issuing export animal health certificates for live animals (including semen and embryos), pets, animal products, and biologics (vaccines, bacterins, antisera, diagnostic kits, and other products of biological origin).25 The process of obtaining an export animal health certificate requires cooperation between the exporter and VS

- 1. The exporter submits an application requesting export animal health certification from VS.26

- 2. A USDA-accredited veterinarian or technical staff inspects and approves the facility where the live animals were raised.

- 3. USDA-accredited veterinarians and special laboratories perform all of the tests and/or animal examinations to verify that the exporter meets importer requirements before issuing a signed export health certificate.

- 4. The completed export animal health certificate is then sent to the exporter and the fee is collected.27

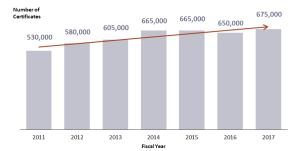

Current Volume of APHIS-Issued Export Health Certificates

USDA's Office of Budget and Program Analysis provides an estimated number of APHIS-issued export certificates each year in the USDA Congressional Budget Justifications. Figure 6 shows an upward trend in the number of APHIS-issued export certificates between FY2011 and FY2017, with an increase of 27%.28

|

Figure 6. Number of APHIS-issued Federal Export Certificates (FY2011-FY2017) |

|

|

Source: CRS, using data from USDA's Office of Budget and Program Analysis. The USDA Congressional Budget Justifications provide an estimated APHIS-issued export certificates each year: https://www.obpa.usda.gov/explan_notes.html. |

APHIS personnel may oversee the provision of an increased number of export health certificates. The President's FY2019 budget proposes to reduce the overall APHIS budget by 25%, which could impact the resources available to process the current volume of APHIS export health certificates.29

How Export Health Certificates Facilitate Trade

Export health certificates facilitate trade by verifying that U.S. agricultural exports meet importers' health and safety standards.30 APHIS, in collaboration with the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), is primarily responsible for resolving disputes that arise between U.S. exporters and importing countries over health-certificate-related issues.31 In FY2017, APHIS negotiated or renegotiated 110 export protocols for animal products involving 24 new markets, three expanded markets, and 83 retained markets. APHIS also negotiated 126 export protocols for live animals.32 In particular, export health certificate discussions among scientific authorities contributed to opening markets for beef to China, poultry to Korea, and potatoes to Japan in FY2017.

Export health certificates and the process underlying them may help facilitate trade in certain animal health situations. For example, following an outbreak of particular cases of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI), or "bird flu," member countries of the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE)33 are obligated to report particular such incidents to OIE. The HPAI-affected country is expected to alert the international community and follow the OIE's disease control guidelines.34 In addition, they would likely have an altered relationship with their trading partners concerning poultry and poultry product exports (including certain eggs) following notification of the outbreak. Typically, importers would either ban poultry imports from the affected country or ban poultry from certain regions from the country—a negotiated "regionalization agreement."35 In this situation, regionalization protocols in the agreement may facilitate exports by limiting the ban to a particular region.36

Export health certificates may facilitate market-opening opportunities for U.S. exports, as in the case of U.S. pork exports to Argentina. Until 2017, the United States had for over 25 years neither access to export pork to Argentina nor a pork health certificate for Argentina because of animal health concerns Argentina cited in U.S. pork production. After Argentine food safety officials conducted an on-site verification of the U.S. meat inspection system in late 2017, the United States finalized a pork SPS agreement and export health certificate with Argentina.37 According to USDA, Argentina is a potential $10 million per year market for U.S. pork producers.38

Considerations for Congress

Congress has direct interest in export health certificates—both through annual appropriations for APHIS activities and through congressional oversight. Examples of potential oversight issues include preparation for animal disease outbreaks, export-market openings, and potential U.S. agricultural trade barriers.

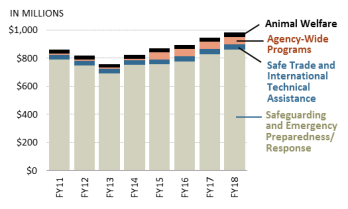

In terms of annual appropriations, APHIS's mission is carried out in their budget: (1) Safeguarding and Emergency Preparedness/Response, (2) Agency Wide Programs, (3) Safe Trade and International Technical Assistance, and (4) Animal Welfare (Figure 7). The Safeguarding and Emergency Preparedness/Response portion of the APHIS budget is responsible for monitoring animal and plant health in the United States and throughout the world, representing roughly 85% of APHIS's budget. Most of the export health certificate activities are housed in this mission area.

|

|

Source: CRS, using USDA, Office of Budget and Program Analysis, USDA Congressional Budget Justifications, and P.L. 115-141. Notes: Discretionary appropriated budget only. Excludes user fees. |

In February 2018, the Office of Management and Budget released the President's FY2019 proposed budget.39 The FY2019 APHIS proposed budget totaled $742 million, down 25% from FY2018 funding. This proposed reduction would affect all major area activities, particularly Safeguarding and Emergency Preparedness/Response. The President's FY2019 APHIS budget proposal for this line item is $623.6 million, a decrease of nearly $200 million from FY2018. This proposed budget reduction for FY2019 could affect APHIS's ability to issue health certificates for both exports and imports of agricultural products. Limiting APHIS's ability to issue export health certificates could negatively impact U.S. agricultural exports. Likewise, APHIS funding for this budget line item also supports APHIS's ability to enforce animal and/or plant health requirements that protect the United States against the unintended introduction of animal and/or plant pests and diseases. As such, a reduction in funding to support these APHIS activities could slow the agency's ability to respond to a disease or pest outbreak in the future while also negatively impacting trade. These APHIS activities also administer certain U.S. commitments to the WTO.40

In contrast to the President's budget proposal for FY2019, both the House and the Senate proposed roughly $1 billion for the FY2019 APHIS budget, or roughly $260 million over the Administration's request and an increase from FY2018 (Table 2). On May 16, 2018, the House Appropriations Committee reported H.R. 5961 with an increase of $16 million (+1.7%) year-over-year. On May 24, 2018, the Senate Appropriations Committee reported S. 2976 with an increase of $19 million (+1.9%) year-over-year.

|

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

Percent Change FY2018 to FY2019 |

||||

|

Admin. Request |

House H.R. 5961 |

Senate S. 2976 |

Enacted |

House |

Senate |

|

|

742.0 |

1,001.5 |

1,003.7 |

— |

+16.5 |

+18.6 |

|

Source: CRS Report R45230, Agriculture and Related Agencies: FY2019 Appropriations.

Finally, as the United States has entered into, or is currently negotiating or renegotiating, certain regional and bilateral free trade agreements that address agricultural trade, APHIS's health certificates would be expected to be a component of any SPS chapter included as part of a free trade agreement or trade negotiation that includes agriculture. These SPS chapters adhere to WTO guidelines and generally include additional specific importer requirements. Each importing country is allowed to have different import requirements—and some are stricter than others—which sometimes result in "non-tariff measures," as explained in the text box below. SPS requirements by individual countries can become the source of a trade dispute and may be used by some countries as a way to protect local markets, thereby discouraging U.S. exports. In these instances APHIS typically seeks to address U.S. exporters' concerns with the importing country's scientific authorities.

|

Non-Tariff Measures "Non-tariff measures" are defined as "policy measures other than ordinary customs tariffs that can potentially have an economic effect on international trade in goods, changing quantities traded, or prices or both." USTR has identified cases where importing countries present unscientific testing requests for U.S. agricultural exports. USTR asserts that these requests are not in line with the WTO Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade, commonly referred to as the TBT agreement. The TBT agreement established rules and procedures to prevent the use of technical requirements as unnecessary barriers to trade. For example, USTR has identified that the United States remains unable to export seed potatoes to Egypt because the Ministry of Agriculture's Central Administration for Plant Quarantine (CAPQ) has failed to officially designate the United States as an approved origin. According to Ministry of Agriculture regulations, CAPQ approves origins only after completing a pest risk analysis. While this risk analysis for U.S. seed potatoes was completed in 2016, Egypt continues to raise concerns over the United States as an origin for seed potatoes. Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. International Classification of Non-Tariff Measures, 2012; and USTR, 2018 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Barriers, March 2018. See also P. Ferrier, "Non-Tariff Measure and Agricultural Trade," presentation for the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, November 28, 2017. |