Introduction

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) are international institutions that provide financial assistance, typically in the form of loans and grants, to developing countries in order to promote economic and social development. The United States is a member and significant donor to five major MDBs. These include the World Bank and four smaller regional development banks: the African Development Bank (AfDB); the Asian Development Bank (AsDB); the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD); and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).1 Congress plays a critical role in shaping U.S. policy at the MDBs through funding and oversight of U.S. participation in the institutions.

This report provides an overview of the MDBs and highlights major issues for Congress. The first section discusses how the MDBs operate, including the history of the MDBs, their operations and organizational structure, and the effectiveness of MDB financial assistance. The second section discusses the role of Congress in the MDBs, including congressional legislation authorizing and appropriating U.S. contributions to the MDBs and congressional oversight of U.S. participation in the MDBs. The third section discusses broad policy debates about the MDBs, including their effectiveness, the trade-offs between providing aid on a multilateral or bilateral basis, the changing landscape of multilateral aid, and U.S. commercial interests in the MDBs.

Overview of the Multilateral Development Banks

MDBs provide financial assistance to developing countries, typically in the form of loans and grants, for investment projects and policy-based loans. Project loans include large infrastructure projects, such as highways, power plants, port facilities, and dams, as well as social projects, including health and education initiatives. Policy-based loans provide governments with financing in exchange for agreement by the borrower country government that it will undertake particular policy reforms, such as the privatization of state-owned industries or reform in agriculture or electricity sector policies. Policy-based loans can also provide budgetary support to developing country governments. In order for the disbursement of a policy-based loan to continue, the borrower must implement the specified economic or financial policies. Some have expressed concern over the increasing budgetary support provided to developing countries by the MDBs. Traditionally, this type of support has been provided by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Most of the MDBs have two major funds, often called lending windows or lending facilities. One type of lending window is primarily used to provide financial assistance on market-based terms, typically in the form of loans, but also through equity investments and loan guarantees.2 Non-concessional assistance is, depending on the MDB, extended to middle-income governments, some creditworthy low-income governments, and private-sector firms in developing countries.3 The other type of lending window is used to provide financial assistance at below market-based terms (concessional assistance), typically in the form of loans at below-market interest rates and grants, to governments of low-income countries. In recent years, two MDBs (the AsDB and the IDB) have transferred concessional lending to their main, non-concessional lending facilities to increase their lending capacities.

Historical Background

World Bank

The World Bank is the oldest and largest of the MDBs. The World Bank Group comprises three subinstitutions that make loans and grants to developing countries: the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the International Development Association (IDA), and the International Finance Corporation (IFC).4

The 1944 Bretton Woods Conference led to the establishment of the World Bank, the IMF, and the institution that would eventually become the World Trade Organization (WTO). The IBRD was the first World Bank affiliate created, when its Articles of Agreement became effective in 1945 with the signatures of 28 member governments. Today, the IBRD has near universal membership with 189 member nations. Only Cuba and North Korea, and a few microstates such as the Vatican, Monaco, and Andorra, are nonmembers. The IBRD lends mainly to the governments of middle-income countries at market-based interest rates.

In 1960, at the suggestion of the United States, IDA was created to make concessional loans (with low interest rates and long repayment periods) to the poorest countries. IDA also now provides grants to these countries. The IFC was created in 1955 to extend loans and equity investments to private firms in developing countries. The World Bank initially focused on providing financing for large infrastructure projects. Over time, this has broadened to also include social projects and policy-based loans.

Regional Development Banks

Inter-American Development Bank

The IDB was created in 1959 in response to a strong desire by Latin American countries for a bank that would be attentive to their needs, as well as U.S. concerns about the spread of communism in Latin America.5 Consequently, the IDB has tended to focus more on social projects than large infrastructure projects, although the IDB began lending for infrastructure projects as well in the 1970s. From its founding, the IDB has had both non-concessional and concessional lending windows. The IDB's concessional lending window was called the Fund for Special Operations (FSO), whose assets were largely transferred to the IDB in 2016. The IDB Group also includes the Inter-American Investment Corporation (IIC) and the Multilateral Investment Fund (MIF), which extend loans to private-sector firms in developing countries, much like the World Bank's IFC.

African Development Bank

The AfDB was created in 1964 and was for nearly two decades an African-only institution, reflecting the desire of African governments to promote stronger unity and cooperation among the countries of their region. In 1973, the AfDB created a concessional lending window, the African Development Fund (AfDF), to which non-regional countries could become members and contribute. The United States joined the AfDF in 1976. In 1982, membership in the AfDB non-concessional lending window was officially opened to non-regional members. The AfDB makes loans to private-sector firms through its non-concessional window and does not have a separate fund specifically for financing private-sector projects with a development focus in the region.

Asian Development Bank

The AsDB was created in 1966 to promote regional cooperation. Similar to the World Bank, and unlike the IDB, the AsDB's original mandate focused on large infrastructure projects, rather than social projects or direct poverty alleviation. The AsDB's concessional lending facility, the Asian Development Fund (AsDF), was created in 1973. In 2017, concessional lending was transferred from the AsDF to the AsDB, although the AsDF still provides grants to low-income countries. Like the AfDF, the AsDB does not have a separate fund specifically for financing private-sector projects, and makes loans to private-sector firms in the region through its non-concessional window.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

The EBRD is the youngest MDB, founded in 1991. The motivation for creating the EBRD was to ease the transition of the former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and the former Soviet Union from planned economies to free-market economies. The EBRD differs from the other regional banks in two fundamental ways. First, the EBRD has an explicitly political mandate: to support democracy-building activities. Second, the EBRD does not have a concessional loan window. The EBRD's financial assistance is heavily targeted on the private sector, although the EBRD does also extend some loans to governments in CEE and the former Soviet Union.

Table 1 summarizes the different lending windows for the MDBs, noting what types of financial assistance they provide, who they lend to, when they were founded, and how much financial assistance they committed to developing countries in 2017.6 The World Bank Group accounted for half of total MDB financial assistance commitments to developing countries in 2017.7 Also, about three-quarters of the financial assistance provided by the MDBs to developing countries was on non-concessional terms.

|

MDB |

Type of |

Type of |

Year Founded |

New Commitments, 2017 |

|

World Bank Group |

||||

|

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) |

Non-concessional loans and loan guarantees |

Primarily middle-income governments, also some creditworthy low-income countries |

1944 |

22.6 |

|

International Development Association (IDA) |

Concessional loans and grants |

Low-income governments |

1960 |

19.5 |

|

International Finance Corporation (IFC) |

Non-concessional loans, equity investments, and loan guarantees |

Private-sector firms in developing countries (middle- and low-income countries) |

1956 |

11.8 |

|

African Development Bank (AfDB) |

Non-concessional and concessional loans, equity investments, and loan guarantees |

Middle-income governments, some creditworthy low-income governments, and private-sector firms in the region |

1964 |

6.3 |

|

African Development Fund (AfDF) |

Grants |

Low-income governments in the region |

1972 |

1.4 |

|

Asian Development Bank (AsDB) |

Non-concessional loans, equity investments, and loan guarantees |

Middle-income governments, some creditworthy low-income governments, and private-sector firms in the region |

1966 |

17.2 |

|

Asian Development Fund (AsDF) |

Concessional loans and grants |

Low-income governments in the region |

1973 |

2.9 |

|

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) |

Non-concessional loans equity investments, and loan guarantees |

Primarily private-sector firms in developing countries in the region, also developing-country governments in the region |

1991 |

11.6 |

|

Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) |

Non-concessional and concessional loans and loan guarantees |

Middle-income governments, some creditworthy low-income governments, and private-sector firms in the region |

1959 |

13.0 |

Source: MDB Annual Reports and Financial Statements.

Note: Throughout the report, World Bank data are for the July-June fiscal year and regional bank data are for the calendar year, unless otherwise noted. Most of the MDBs also have additional funds that they administer, typically funded by a specific donor and/or targeted toward narrowly defined projects. Data in report converted to U.S. dollars using year-end exchange rates.

a. IFC new commitments only include long-term commitments.

b. Excludes guarantees issued under the Trade Finance Facilitation Program and non-sovereign-guaranteed loan participations, and exposure and exchange arrangements.

c. AsDB data are for loans only.

Operations: Financial Assistance to Developing Countries

Financial Assistance over Time

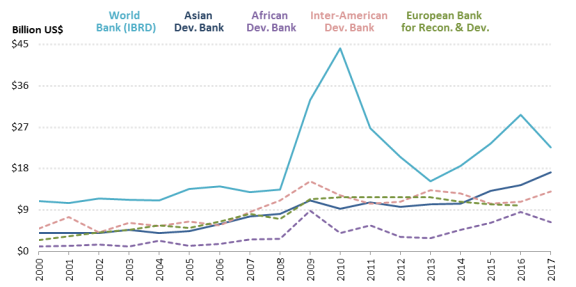

Figure 1 shows MDB financial commitments to developing countries since 2000 financed from their ordinary capital resources (OCR), the lending facility traditionally focused on non-concessional financial assistance. As a whole, financial assistance funded out of OCR resources was relatively stable in nominal terms until the global financial crisis prompted major member countries to press for increased financial assistance. In response to the financial crisis and at the urging of its major member countries, the IBRD dramatically increased lending between FY2008 and FY2009. Regional development banks also had upticks in lending between 2008 and 2009. MDB non-concessional assistance, particularly by the IBRD, fell to pre-crisis levels as the financial crisis stabilized, but has been rising again in the past few years.

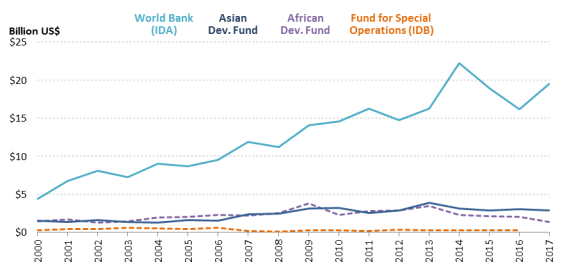

Figure 2 shows concessional financial assistance provided by the MDBs to developing countries since 2000. The World Bank's concessional lending arm, IDA, has grown steadily over the decade in nominal terms, although it has decreased over the past two years, while the regional development bank concessional lending facilities, by contrast, have remained relatively stable in nominal terms.

Recipients of MDB Financial Assistance

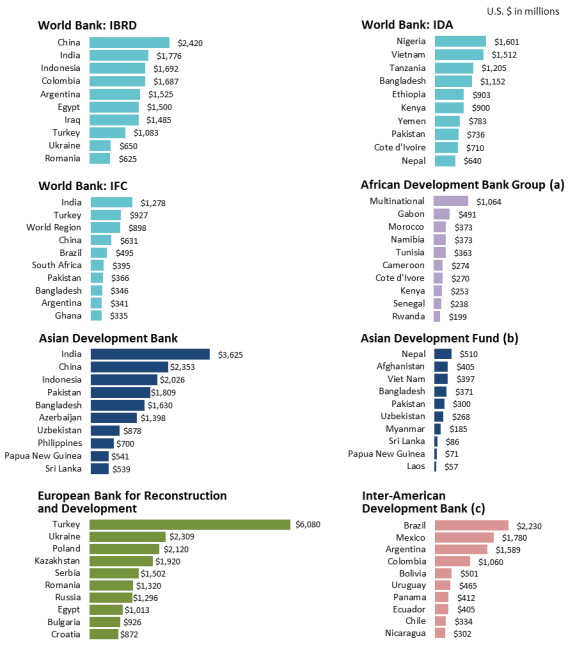

Figure 3 lists the top recipients of MDB financial assistance in 2017. It shows that several large, emerging economies, such as Brazil, India, China, and Turkey, receive a steady flow of financial assistance from the MDBs. Figure 3 also shows the top recipients of concessional financial assistance. In 2017, Nigeria and Vietnam were top recipients of financial assistance from IDA, and Nepal and Afghanistan were top recipients of financial assistance from the AsDF.

|

MDB Financial Assistance to Emerging Markets Financial assistance from the MDBs to emerging economies is controversial. Some argue that, instead of using MDB resources, these countries should rely on their own resources, particularly countries like China, which has substantial foreign reserves holdings and can easily get loans from private capital markets to fund development projects. MDB assistance, it is argued, would be better suited to focusing on the needs of the world's poorest countries, which do not have the resources to fund development projects and cannot borrow these resources from international capital markets. Others argue that MDB financial assistance provided to large, emerging economies is important, because these countries have substantial numbers of people living in poverty and MDBs provide financial assistance for projects for which the government might be reluctant to borrow. Additionally, MDB assistance helps address environmental issues, promotes better governance, and provides important technical assistance to which emerging economies might not otherwise have access. Finally, supporters argue that because MDB assistance to emerging economies takes the form of loans with market-based interest rates, rather than concessional loans or grants, this assistance is relatively inexpensive to provide and generates income to cover the MDBs' operating costs. |

Funding: Donor Commitments and Contributions

MDBs are able to extend financial assistance to developing countries due to the financial commitments of their more prosperous member countries. This support takes several forms, depending on the type of assistance provided. The MDBs use money contributed or "subscribed" by their member countries to support their assistance programs. They fund their operating costs from money earned on non-concessional loans to borrower countries. Some of the MDBs transfer a portion of their surplus net income annually to help fund their concessional aid programs.

Non-concessional Lending Windows

To offer non-concessional loans, the MDBs borrow money from international capital markets and then relend the money to developing countries. MDBs are able to borrow from international capital markets because they are backed by the guarantees of their member governments. This backing is provided through the ownership shares that countries subscribe as a consequence of their membership in each bank.8 Only a small portion (typically less than 5%-10%) of the value of these capital shares is actually paid to the MDB ("paid-in capital").

The bulk of these shares are a guarantee that the donor stands ready to provide to the bank if needed. This is called "callable capital," because the money is not actually transferred from the donor to the MDB unless the bank needs to call on its members' callable subscriptions. Banks may call upon their members' callable subscriptions only if their resources are exhausted and they still need funds to repay bondholders. To date, no MDB has ever had to draw on its callable capital. In recent decades, the MDBs have not used their paid-in capital to fund loans. Rather it has been put in financial reserves to strengthen the institutions' financial base.

Due to the financial backing of their member country governments, the MDBs are able to borrow money in world capital markets at the lowest available market rates, generally the same rates at which developed country governments borrow funds inside their own borders. The banks are able to relend this money to their borrowers at much lower interest rates than the borrowers would generally have to pay for commercial loans, if, indeed, such loans were available to them. As such, the MDBs' non-concessional lending windows are self-financing and even generate net income.

Periodically, when donors agree that future demand for loans from an MDB is likely to expand, they increase their capital subscriptions to an MDB's non-concessional lending window in order to allow the MDB to increase its level of lending. This usually occurs because the economy of the world or the region has grown in size and the needs of their borrowing countries have grown accordingly, or in response to a financial crisis. An across-the-board increase in all members' shares is called a "general capital increase" (GCI). This is in contrast to a "selective capital increase" (SCI), which is typically small and used to alter the voting shares of member countries. The voting power of member countries in the MDB is determined largely by the amount of capital contributed and through selective capital increases; some countries subscribe a larger share of the new capital stock than others to increase their voting power in the institutions. GCIs happen infrequently. Quite unusually, all the MDBs had GCIs following the global financial crisis of 2008-2009; simultaneous capital increases for all the MDBs had not occurred since the mid-1970s.9

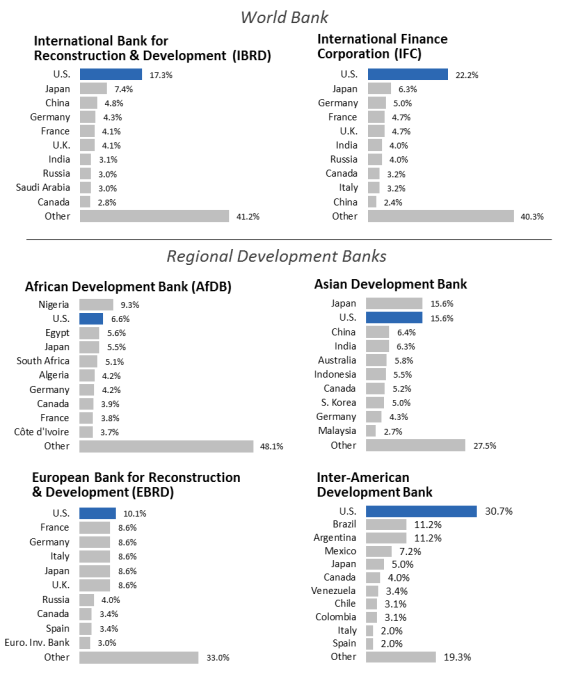

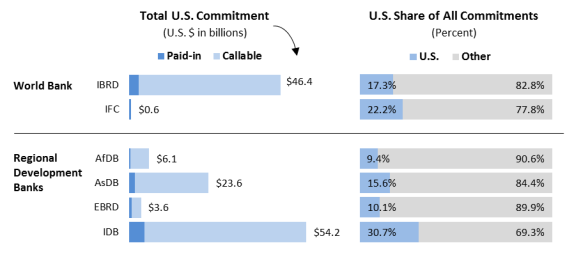

Figure 4 summarizes current U.S. capital subscriptions to the MDB non-concessional lending windows. Currently, the largest U.S. share of subscribed MDB capital is with the IDB at 30%, while its smallest share among the MDBs is with the AfDB at 6.6%.

|

Figure 4. MDB Non-concessional Lending Windows: U.S. Financial Commitments |

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS using MDB Annual Reports and Financial Statements. Notes: Values may not add due to rounding. |

Figure 5 lists the top donors to the MDBs's non-concessional facilities. The United States is the largest donor to the non-concessional lending windows to the IBRD, the IFC, the EBRD, and the IDB. The United States is tied with Japan for the largest financial commitment to the AsDB and is the second-largest donor to the AfDB.

Other top donor states include Western European countries, Japan, and Canada. Additionally, several regional members have large financial stakes in the regional banks. For example, among the regional members, China and India are large contributors to the AsDB; Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa, and Algeria are major contributors to the AfDB; Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela are large contributors to the IDB; and Russia is a large contributor to the EBRD.

Concessional Lending Windows

Concessional lending windows do not issue bonds; their funds are contributed directly from the financial contributions of their member countries. Most of the money comes from the more prosperous countries, while the contributions from borrowing countries are generally more symbolic than substantive. The MDBs have also transferred some of the net income from their non-concessional windows to their concessional lending windows in order to help fund concessional loans and grants.

As the MDB extends concessional loans and grants to low-income countries, the window's resources become depleted. The donor countries meet together periodically to replenish those resources. Thus, these increases in resources are called replenishments, and most occur on a planned schedule ranging from three to five years. If these facilities are not replenished on time, they will run out of lendable resources and have to reduce their levels of aid to poor countries.

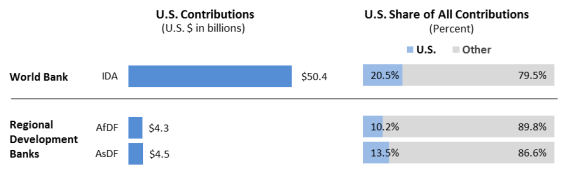

Figure 6 summarizes cumulative U.S. contributions to the MDB concessional lending windows. The United States has made the largest financial commitment to IDA over time, relative to the other concessional lending facilities.

|

Figure 6. MDB Concessional Lending Windows: Cumulative U.S. Contributions |

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS using MDB Annual Reports and Financial Statements. Notes: Data are for cumulative commitments. |

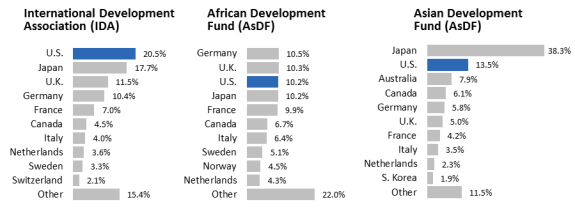

Figure 7 shows the top donor countries to the MDB concessional facilities. The United States is been the largest donor to IDA and is a major donor to the AsDF and the AsDB. Other top donor states include the more prosperous member countries, including Japan, Canada, and those in Western Europe.

Structure and Organization

Relation to Other International Institutions

The World Bank is a specialized agency of the United Nations. However, it is autonomous in its decisionmaking procedures and its sources of funds. It also has autonomous control over its administration and budget. The regional development banks are independent international agencies and are not affiliated with the United Nations system. All the MDBs must comply with directives (for example, economic sanctions) agreed to (by vote) by the U.N. Security Council. However, they are not subject to decisions by the U.N. General Assembly or other U.N. agencies.

Internal Organization and U.S. Representation

The MDBs have similar internal organizational structures. Run by their own management and staffed by international civil servants, each MDB is supervised by a Board of Governors and a Board of Executive Directors. The Board of Governors is the highest decisionmaking authority, and each member country has its own governor. Countries are usually represented by their Secretary of the Treasury, Minister of Finance, or Central Bank Governor. The United States is represented by the Treasury Secretary. The Board of Governors meets annually, though it may act more frequently through mail-in votes on key decisions.

While the Boards of Governors in each of the banks retain power over major policy decisions, such as amending the founding documents of the organization, they have delegated day-to-day authority over operational policy, lending, and other matters to their institutions' Board of Executive Directors. The Board of Executive Directors in each institution is smaller than the Board of Governors. There are 24 members on the World Bank's Board of Executive Directors, and fewer for some of the regional development banks. Some major donors, including the United States, are represented by their own Executive Director. Other Executive Directors represent groups of member countries. Each MDB Executive Board has its own schedule, but they generally meet at least weekly to consider MDB loan and policy proposals and oversee bank activities.

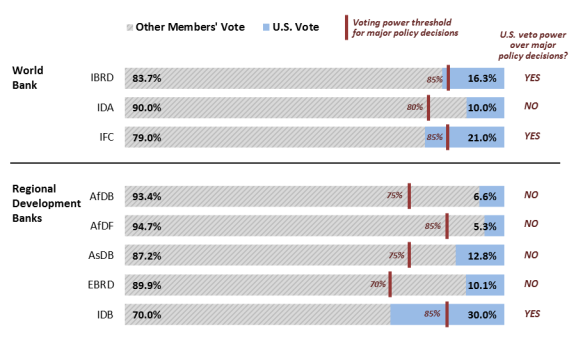

Decisions are reached in the MDBs through voting. Each member country's voting share is weighted on the basis of its cumulative financial contributions and commitments to the organization.10 Figure 8 shows the current U.S. voting power in each institution. The voting power of the United States is large enough to veto major policy decisions at the World Bank and the IDB. However, the United States cannot unilaterally veto more day-to-day decisions, such as individual loans.

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS using MDB Annual Reports and Financial Statements. |

The Role of Congress in U.S. Participation

Congress plays an important role in authorizing and appropriating U.S. contributions to the MDBs and exercising oversight of U.S. participation in these institutions. For more details on U.S. policymaking at the MDBs, see CRS Report R41537, Multilateral Development Banks: How the United States Makes and Implements Policy, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

Authorizing and Appropriating U.S. Contributions to the MDBs

Authorizing and appropriations legislation is required for U.S. contributions to the MDBs. The Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and the House Committee on Financial Services are responsible for managing MDB authorization legislation. During the past several decades, authorization legislation for the MDBs has not passed as freestanding legislation. Instead, it has been included through other legislative vehicles, such as the annual foreign operations appropriations act, a larger omnibus appropriations act, or a budget reconciliation bill. The Foreign Operations Subcommittees of the House and Senate Committees on Appropriations manage the relevant appropriations legislation. MDB appropriations are included in the annual foreign operations appropriations act or a larger omnibus appropriations act.

In recent years, the Administration's budget request for the MDBs has included three major components: funds to replenish the concessional lending windows, funds to increase the size of the non-concessional lending windows (the "general capital increases"), and funds for more targeted funds administered by the MDBs, particularly those focused on climate change and food security.11 Replenishments of the MDB concessional windows happen regularly, while capital increases for the MDB non-concessional windows occur much more infrequently. Quite unusually, all the MDBs increased their non-concessional windows in response to the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 and the resulting increased demand for financing.

Congressional Oversight of U.S. Participation in the MDBs

As international organizations, the MDBs are generally exempt from U.S. law. The President has delegated the authority to manage and instruct U.S. participation in the MDBs to the Secretary of the Treasury. Within the Treasury Department, the Office of International Affairs has the lead role in managing day-to-day U.S. participation in the MDBs. The President appoints the U.S. Governors and Executive Directors, and their alternates, with the advice and consent of the Senate. Thus, the Senate can exercise oversight through the confirmation process.

Over the years, Congress has played a major role in U.S. policy toward the MDBs. In addition to congressional hearings on the MDBs, Congress has enacted a substantial number of legislative mandates that oversee and regulate U.S. participation in the MDBs. These mandates generally fall into one of four major types. More than one type of mandate may be used on a given issue area.

First, some legislative mandates direct how the U.S. representatives at the MDBs can vote on various policies. Examples include mandates that require the U.S. Executive Directors to oppose (a) financial assistance to specific countries, such as Burma, until sufficient progress is made on human rights and implementing a democratic government;12 (b) financial assistance to broad categories of countries, such as major producers of illicit drugs;13 and (c) financial assistance for specific projects, such as the production of palm oil, sugar, or citrus crops for export if the financial assistance would cause injury to United States producers.14 Some legislative mandates require the U.S. Executive Directors to support, rather than oppose, financial assistance. For example, a current mandate allows the Treasury Secretary to instruct the U.S. Executive Directors to vote in favor of financial assistance to countries that have contributed to U.S. efforts to deter and prevent international terrorism.15

Second, legislative mandates direct the U.S. representatives at the MDBs to advocate for policies within the MDBs. One example is a mandate that instructs the U.S. Executive Director to urge the IBRD to support an increase in loans that support population, health, and nutrition programs.16 Another example is a mandate that requires the U.S. Executive Directors to take all possible steps to communicate potential procurement opportunities for U.S. firms to the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Commerce, and the business community.17 Mandates that call for the U.S. Executive Director to both vote and advocate for a particular policy are often called "voice and vote" mandates.

Third, Congress has also passed legislation requiring the Treasury Secretary to submit reports on various MDB issues (reporting requirements). Some legislative mandates call for one-off reports; other mandates call for reports on a regular basis, typically annually. For example, current legislation requires the Treasury Secretary to submit an annual report to the appropriate congressional committees on the actions taken by countries that have borrowed from the MDBs to strengthen governance and reduce the opportunity for bribery and corruption.18

Fourth, Congress has also attempted to influence policies at the MDBs through "power of the purse," that is, withholding funding from the MDBs or attaching stipulations on the MDBs' use of funds. For example, the FY2010 Consolidated Appropriations Act stipulates that 10% of the funds appropriated to the AsDF will be withheld until the Treasury Secretary can verify that the AsDB has taken steps to implement specific reforms aimed at combating corruption.19

Policy Issues for Congress

The United States has historically played a strong leadership role at the MDBs, including key roles in creating the institutions and shaping their policies and lending to developing countries. Under a number of Administrations, the MDBs have been viewed as critical to promoting U.S. foreign policy, economic interests, and national security interests abroad, although various Administrations have had different views on the appropriate level of U.S. funding for the MDBs and policy reforms to improve the effectiveness of the MDBs.

There are a number of MDB policy issues that Congress may consider during the 115th Congress, particularly as it considers U.S. funding levels for the MDBs and confirmations for U.S. Governors and Executive Directors at the MDBs. Some of these issues are discussed below.

U.S. Funding for the MDBs

U.S. funding for the MDBs may shift under President Trump, who campaigned on an "America First" platform and has signaled a reorientation of U.S. foreign policy. In March 2017, the Trump Administration proposed cutting $650 million over three years compared to the commitments made under the Obama Administration.20

In the FY2019 budget request, the Trump Administration requested a 20% cut ($354 million) from Treasury's international programs, which includes the multilateral development banks, compared to the amount enacted in FY2017.21 The bulk of the Treasury international programs request (over 90%) would fund U.S. commitments to concessional lending facilities at the MDBs. The request would provide $1.1 billion to IDA, compared to $1.2 billion in FY2017. It would also provide funding $47 million to the AsDF and $171 million to the AfDF, among other funding initiatives.

In April 2018, the World Bank members, including the United States, endorsed a capital increase for the IBRD, which would require congressional legislation and appropriations to implement.22 This commitment is not reflected in the FY2019 budget request, but would require appropriations and authorization to implement. Congress sets U.S. funding for the MDBs as part of the State and Foreign Operations authorization and appropriations process.23

Effectiveness of MDB Financial Assistance

There is a broad debate about the effectiveness of foreign aid, including the aid provided by the MDBs. Many studies of foreign aid effectiveness examine the effects of total foreign aid provided to developing countries, including both aid given directly by governments to developing countries (bilateral aid) and aid pooled by a multilateral institution from multiple donor countries and provided to developing countries (multilateral aid). The results of these studies are mixed, with conclusions ranging from (a) aid is ineffective at promoting economic growth;24 (b) aid is effective at promoting economic growth;25 and (c) aid is effective at promoting growth in some countries under specific circumstances (such as when developing-country policies are strong).26 The divergent results of these academic studies make it difficult to reach firm conclusions about the overall effectiveness of aid.

Critics of the MDBs argue that they are international bureaucracies focused on getting money "out the door" to developing countries, rather than on delivering results in developing countries; that the MDBs emphasize short-term outputs like reports and frameworks but do not engage in long-term activities like the evaluation of projects after they are completed; and that they put enormous administrative demands on developing-country governments.27 Many of the MDBs were also created when developing countries had little access to private capital markets. With the globalization and the integration of capital markets across countries, some analysts have expressed concerns that MDB financing might "crowd out" private-sector financing, which developing countries now generally have readily accessible. Some analysts have also raised questions about whether there is a clear division of labor among the MDBs.

Proponents of the MDBs argue that, despite some flaws, such aid at its core serves vital economic and political functions. With about 767 million people living on less than $1.90 a day in 2013 (most recent estimate available),28 they argue that not providing assistance is simply not an option; they argue it is the "right" thing to do and part of "the world's shared commitments to human dignity and survival."29 These proponents typically point to the use of foreign aid to provide basic necessities, such as food supplements, vaccines, nurses, and access to education, to the world's poorest countries, which may not otherwise be financed by private investors. Additionally, proponents of foreign aid argue that, even if foreign aid has not been effective at raising overall levels of economic growth, foreign aid has been successful in dramatically improving health and education in developing countries over the past four decades.30

Some analysts have also highlighted a number of reforms that they believe could increase the effectiveness of the MDBs.31 For example, it has been proposed that the MDBs adopt more flexible financing arrangements, for example to allow crisis lending or lending at the subnational level, and more flexibility in providing concessional assistance to address poverty in middle-income countries. There are also arguments that, as countries continue to develop, there need to be clearer guidelines on when countries should "graduate" from receiving concessional and/or non-concessional financial assistance from the MDBs.

Multilateral vs. Bilateral Aid

There has been debate about whether U.S. policymakers should prioritize bilateral or multilateral aid.32 Bilateral aid gives donors more control over where the money goes and how the money is spent. For example, donor countries may have more flexibility to allocate funds to countries that are of geopolitical strategic importance, but not facing the greatest development needs, than might be possible by providing aid through a multilateral organization. By building a clear link between the donor country and the recipient country, bilateral aid may also garner more goodwill from the recipient country toward the donor than if the funds had been provided through a multilateral organization.

Providing aid through multilateral organizations offers different benefits for donor countries. By pooling the resources of several donors, multilateral organizations allow donors to share the cost of development projects (often called burden-sharing). Additionally, donor countries may find it politically sensitive to attach policy reforms to loans or to enforce these policy reforms. Multilateral organizations can usefully serve as a scapegoat for imposing and enforcing conditionality that may be politically sensitive to attach to bilateral loans. Additionally, because MDBs can provide aid on a larger scale than many bilateral agencies, they can generate economies of scale in knowledge and lending.33

Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) show that in 2017, 14% of U.S. foreign aid disbursed to developing countries with the purpose of promoting economic and social development was provided through multilateral institutions, while 86% was provided bilaterally.34

The Changing Landscape of the MDBs

In recent years, several countries have taken steps to launch two new multilateral development banks. First, Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (the BRICS countries) signed an agreement in July 2014 to establish the New Development Bank (NDB), often referred to as the "BRICS Bank."35 The agreement outlines the bylaws of the bank and a commitment to a capital base of $100 billion. Headquartered in Shanghai, the NDB was formally launched in July 2015. The BRICS leaders have emphasized that the bank's mission is to mobilize resources for infrastructure and sustainable development projects in BRICS and other emerging and developing economies.36

Second, China has led the creation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).37 Launched in October 2014, the AIIB focuses on the development of infrastructure and other sectors in Asia, including energy and power, transportation and telecommunications, rural infrastructure and agriculture development, water supply and sanitation, environmental protection, urban development, and logistics. The AIIB currently has 66 members, and 21 prospective members. Members include several advanced European and Asian economies, such as France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and South Korea. The United States and Japan are not members. The AIIB's initial total capital is expected to be $100 billion.

These two institutions are the first major MDBs to be created in decades, and there is debate about how they will fit in with existing international financial institutions. Proponents of the new MDBs argue that the infrastructure and financing needs of developing countries are beyond what can be met by existing MDBs and private capital markets, and that new institutions to meet the financing needs of developing institutions should be welcomed. Proponents also argue that the new MDBs address the long-held frustrations of many emerging markets and developing countries that the governance of existing institutions, including the World Bank and the IMF, has not been reformed to reflect their growing importance in the global economy.38 For example, the NDB has stressed that, unlike the World Bank and the IMF, each participant country will have equivalent voting rates and none of the countries will have veto power.

Other analysts and policymakers have been more concerned about what the new MDBs could mean for the existing institutions and whether they will diminish the influence of existing institutions, where the United States for decades has held a powerful leadership. They point to an already crowded landscape of MDBs, and express concerns that new MDBs could exacerbate existing concerns about mission creep and lack of clear division of labor among the MDBs. Some analysts have also raised questions about whether the new institutions will adopt the best practices on transparency, procurement, and environmental and social safeguards of the existing MDBs that have been developed over the past several decades. Some analysts have also raised questions about why many emerging markets are top recipients of non-concessional financial assistance from the World Bank and regional development banks, if they have the resources to capitalize new MDBs.

The Obama Administration initially lobbied several key allies to refrain from joining the AIIB. Ultimately, these lobbying efforts were largely unsuccessful, as several key allies in Europe and Asia, including the United Kingdom and South Korea, joined.39 The tone of the Obama Administration shifted, most notably during Chinese President Xi's visit to Washington in September 2015 when the White House emphasized that "the United States welcomes China's growing contributions to financing development and infrastructure in Asia and beyond."40 During the visit, Xi also reportedly committed that the AIIB would abide by the highest international environmental and governance standards.41 Xi also pledged to increase China's financial contributions to the World Bank and regional development banks, signaling its continuing commitment to existing institutions. Congress may want to exercise oversight of the Trump Administration's policy on and engagement with these new MDBs.

U.S. Commercial Interests

Billions of dollars of contracts are awarded to private firms each year in order to acquire the goods and services necessary to implement projects financed by the MDBs. MDB contracts are awarded through international competitive bidding processes, although most MDBs allow the borrowing country to give some preference to domestic firms in awarding contracts for MDB-financed projects in order to help spur development.

U.S. commercial interest in the MDBs has been and may continue to be a subject of congressional attention, particularly if the banks expand their lending capacity for infrastructure projects through the GCIs. One area of focus may be the Foreign Commercial Service (FCS) representatives to the MDBs, who are responsible for protecting and promoting American commercial interests at the MDBs.42 Some in the business community are concerned about the impacts of possible budget cuts to the U.S. FCS, particularly if other countries are taking a stronger role in helping their businesses bid on projects financed by the MDBs.