Introduction

U.S. security sector assistance to foreign countries is funded primarily in the foreign affairs and defense budgets. As the 115th Congress considers its spending priorities for the coming fiscal year, the magnitude, trends, and uses of such assistance may be examined and debated. The Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations; the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA); and the Department of Defense (DOD) appropriations all contain provisions that could affect security assistance funding in FY2018 and beyond. While the Department of State (DOS) and the Department of Defense (DOD) are the primary actors in the provision of such assistance to foreign countries—and the primary focus of this CRS report―other U.S. agencies may also conduct related programs, including the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID); the Departments of Energy (DOE), Homeland Security (DHS), Justice (DOJ), and the Treasury; and parts of the intelligence community.

With the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (FAA, P.L. 87-195) and later the Arms Export Control Act of 1976 (AECA, P.L. 90-629), as amended, Congress established the foundational authorities for contemporary U.S. security assistance programs. These authorities charged the Secretary of State with responsibility to provide "continuous supervision and general direction" of foreign assistance and contained specific reference to "military assistance, including military education and training," to ensure its coherence with foreign policy. Over time, the Secretary of State's security assistance authorities expanded to include international narcotics control, peacekeeping operations, antiterrorism assistance, and nonproliferation and export control assistance. The State Department's authorities were codified in Title 22 of the U.S. Code (Foreign Relations and Intercourse), and funds for such assistance programs are largely appropriated through State Department accounts. Such assistance to foreign governments, security forces, and militaries covers a wide spectrum of activities, including the transfer of conventional arms, training and equipping regular and irregular forces for combat, law enforcement training, defense institution reform, humanitarian assistance, and engagement and educational activities. These activities may serve multiple purposes for both the United States and the recipient country.

DOD has long played a crucial role in the implementation of Title 22 security assistance programs and activities, but for many decades, it otherwise relegated the training, equipping, and assisting of foreign military forces as a secondary mission on its list of priorities, far below war-fighting.1 Beginning in the 1980s, Congress began providing DOD with additional authority in Title 10 of the U.S. Code and annual NDAAs to conduct a range of programs and activities funded by DOD appropriations. Congress began providing such authorities in the 1980s for counternarcotics and humanitarian assistance; authority for nonproliferation and counterterrorism programs was subsequently added in the 1980s and 1990s.

In recent years, the international security environment, and the associated perceived threats to the United States homeland, has led DOD increasingly to give greater priority to building and strengthening security partnerships in a variety of contexts around the world. Particularly since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Congress has granted DOD new authorities in annual NDAAs and in Title 10 (Armed Services) of the U.S. Code to engage in "security cooperation" with foreign militaries and other security forces—now considered by DOD to be an "important tool" for executing its national security responsibilities and "an integral element of the DOD mission."2 This trend underlies a significant expansion of DOD direct engagements with foreign security forces and an accompanying increase in DOD's role in foreign policy decisionmaking. As the United States undertook military action and increased the scope of its foreign counterterrorism operations, Congress provided a number of DOD crisis and wartime authorities, some providing new global authority and some specific to certain geographic areas.3

In enacting these new authorities and appropriations, Congress has bolstered an expanding global DOD role in building foreign partner capacity through programs to train and equip foreign security forces, notably in the realms of counterterrorism, counternarcotics, and defense institution building. In addition, DOD is authorized to carry out various security cooperation and logistical support activities, as well as advise and assist missions that may have the added impact of boosting partner country capabilities. DOD's security cooperation authorities were most recently and significantly modified in the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) (P.L. 114-328; signed December 23, 2016), which enacted several new provisions that modify the budgeting, execution, administration, and evaluation of DOD security cooperation programs and activities. Implementation of these provisions remains a work in progress.

The expansion of DOD's engagement with foreign partner militaries over the past decade has both policy and budgetary implications. These include the overall size and scope of U.S. security assistance activities worldwide, the geographic distribution of such activities, and the relative influence of DOS and DOD in interagency security policymaking processes. Another implication relates to congressional committees of jurisdiction, as primary oversight and funding prerogatives have progressively extended and migrated from foreign relations to defense authorizers and appropriators. Yet, challenges continue to exist in the development of consistent interagency action and terminology to describe the range of security assistance and cooperation programs and activities funded by the U.S. government.

Moreover, funding data for security assistance and data on historical security assistance funding are incomplete. Although DOS has long been required to track most security assistance funding by aid account and on an individual country basis, DOD has not. As a result, comparisons between security assistance funding provided by both departments are challenging, and totaling the two may leave gaps.4

The 115th Congress is continuing scrutiny and debate on security assistance matters. Within the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs FY2018 budget request, the Administration is seeking to reduce international security assistance by about $2.3 billion, or 24.4%. Each of the security assistance programs would be reduced by amounts ranging from 9% to more than 54%. In addition, the Administration proposes making changes to security assistance programs, such as designating 95% of the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) program to four countries. The remaining 5% of the funds, rather than being made available on a grant basis globally as FMF is currently implemented, would be made available to all other countries with a combination of grant and loan assistance to be coordinated with DOD. Congress is also debating a possible increase of Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funds for defense and nondefense, including for funding security assistance activities in FY2018.5

Currently, there is no DOD budget request for security cooperation programs and activities that is comparable to the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs FY2018 budget request for State Department-managed security assistance accounts. Soon, however, this may change; Section 1249 of the FY2017 NDAA added a new section to Title 10 of the U.S. Code, requiring the President, beginning with the FY2019 budget, to submit a formal, consolidated budget request for all DOD's security cooperation efforts, including the military departments and, as practicable, by country or region and by authority.

For further background on U.S. security assistance and cooperation policies, see CRS Report R44444, Security Assistance and Cooperation: Shared Responsibility of the Departments of State and Defense; CRS Report R44602, DOD Security Cooperation: An Overview of Authorities and Issues; CRS Report R44313, What Is "Building Partner Capacity?" Issues for Congress; and CRS In Focus IF10582, Security Cooperation Issues: FY2017 NDAA Outcomes.

Security Assistance Funding Trends Overview

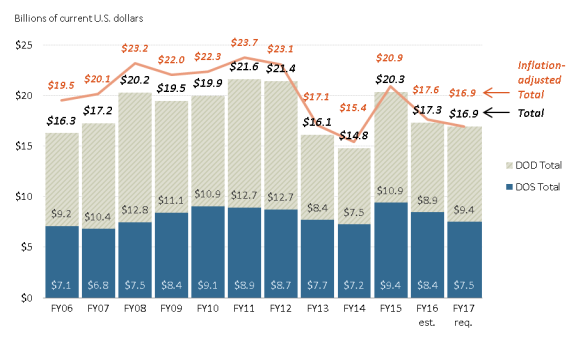

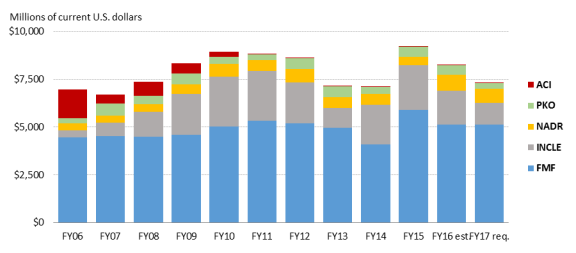

Based on DOS and DOD funding data, the U.S. government has provided at least $204.6 billion to provide security assistance and cooperation to allied countries abroad between FY2006 and FY2016. In that timeframe, DOD funded approximately $115.4 billion in security cooperation activities worldwide, averaging $10.5 billion annually, while the State Department funded approximately $89.2 billion in security assistance worldwide, averaging $8.1 billion annually. Overall funding peaked in FY2011, when a total of $21.6 billion was obligated, largely due to the surge in support activities in Afghanistan. Security assistance funding managed by DOS peaked at $9.4 billion in FY2015 because of increased funds to counter the Islamic State terrorist organization and security aid to the Middle East. For DOD, funding peaked at $12.8 billion in FY2008, with funding increases for Afghanistan and Iraq security.

After adjusting for inflation, the constant dollar total trend line illustrates the same peaks and troughs as the current dollar trend. However, it illustrates a general decline overall in recent years as compared with the funding levels of earlier years―FY2006-FY2012 funding levels (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Security Assistance Funding Trends, FY2006-FY2017 Request |

|

|

Source: For DOS FY2006-FY2015 data: USAID Foreign Assistance Database, prepared by USAID Economic Analysis and Data Services, April 5, 2017. For PCCF, GSCF, FY2016 estimate, and FY2017 request: the Budget of the U.S. Government, Appendix, Fiscal Years FY2015-2017. For DOD data, Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS), https://www.dfas.mil/dodbudgetaccountreports.html; DOD Budget Justification Materials, (http://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials) Note: Inflation-adjusted Total (constant dollars) were calculated using the 2017 GDP price index from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis and the July 2017 Congressional Budget Office data and projections. |

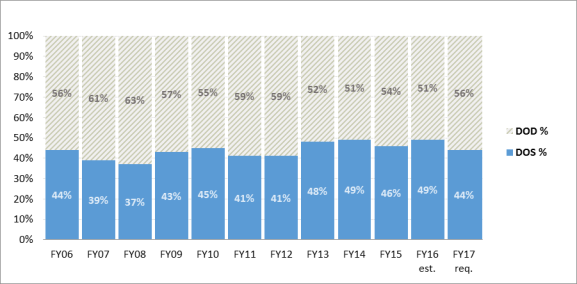

In the past decade, DOD has typically obligated a larger portion of overall security cooperation funding compared to DOS, though State obligated nearly half of U.S. security assistance funding in FY2013, FY2014, and FY2016. The highest share of DOD obligations occurred in FY2007 (61%) and FY2008 (63%). (See Figure 2 below.)

|

Figure 2. DOS and DOD Security Assistance and Cooperation Funding: Annual Proportions, FY2006-FY2017 (req.) (Proportions based on current U.S. dollar data) |

|

|

Source: For DOS FY2006-FY2015 data: USAID Foreign Assistance Database, prepared by USAID Economic Analysis and Data Services, April 5, 2017. For PCCF, GSCF, FY2016 estimate, and FY2017 request: the Budget of the U.S. Government, Appendix, Fiscal Years FY2015-2017. For DOD data, Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS), https://www.dfas.mil/dodbudgetaccountreports.html; DOD Budget Justification Materials, http://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials. |

Top Recipients

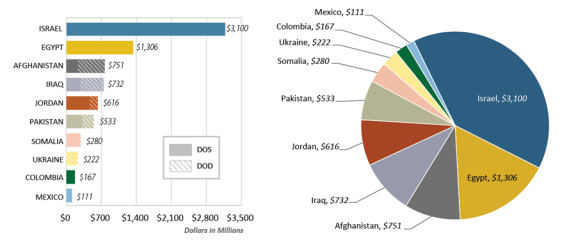

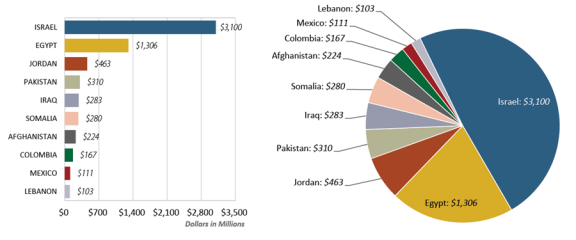

In FY2016 (the most recent year for which complete country allocations are available), the top 10 recipients of U.S. security assistance and cooperation accounted for $7.8 billion (45%) of the combined funding provided by DOS and DOD for that year. Figure 3 illustrates the dollar amount and share of the top 10 recipients of U.S. security assistance and cooperation.

|

Figure 3. Top 10 Recipients of DOS/DOD Security Assistance and Cooperation Programs, FY2016 |

|

|

Source: For DOS information, email communication on September 20, 2017, from State's Legislative Affairs office. For DOD information, email communication from Defense Office of Legislative Affairs on September 19, 2017. Note: DOD funding includes train and equip activities and Defense Security Cooperation Agency's (DSCA's) Coalition Support Fund (CSF) account, but not counternarcotics. DOS funding does not include regional funding that goes to multiple countries. See Table 1 and Table 2 below for included accounts. |

Of the $7.8 billion that went to the top 10 recipients in FY2016, Israel had the largest share at 40%, followed by Egypt at 17%, Afghanistan at 10%, and Iraq at 9%. Combined, Israel and Egypt received 57% of the top 10 share. The amount of FY2016 security assistance and cooperation funding for Pakistan is $533 million; it had been more than double that level as recently as FY2011, when it was $1.3 billion; Pakistan is the sixth-largest recipient of U.S. security assistance and cooperation funds in FY2016 with 6% of the $7.8 billion.

Key Accounts

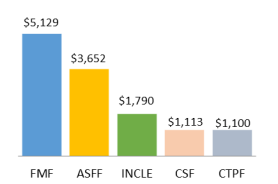

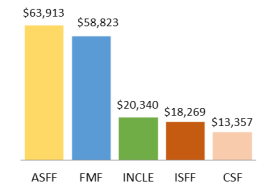

The top five DOS/DOD appropriations accounts through which security assistance has been funded from FY2006 to the FY2017 request are Afghanistan Security Forces Fund (ASFF), Foreign Military Financing (FMF), International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE), Iraq Security Forces Fund (ISFF), and Coalition Support Funds (CSF). (See Figure 4.)

|

Figure 4. Top Five DOS/DOD Security Assistance and Cooperation Accounts, FY2006 to FY2017 Request Summation of Annual Data in Millions of Current U.S. Dollars |

|

|

Source: For DOS FY2006-FY2015 data: USAID Foreign Assistance Database, prepared by USAID Economic Analysis and Data Services, April 5, 2017. For PCCF, GSCF, FY2016 estimate, and FY2017 request: the Budget of the U.S. Government, Appendix, Fiscal Years FY2015-2017. For DOD data, Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS), https://www.dfas.mil/dodbudgetaccountreports.html; DOD Budget Justification Materials, http://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials. Notes: ASFF=Afghanistan Security Forces Fund; FMF=Foreign Military Financing; INCLE=International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement; ISFF=Iraq Security Forces Fund; and CSF=Coalition Support Funds. For program descriptions, see Appendix A and Appendix B. |

Figure 5 and Figure 6 show a comparison of the top-ranking DOS and DOD accounts for FY2016 compared with the FY2017 request. FMF is the highest-funded account for both years. Other top accounts include ASFF, INCLE, CSF, and the Counterterrorism Partnerships Fund (CTPF).

|

|

|

||||||

State Department and USAID Security Assistance Funding Levels

DOS and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) security assistance programs are authorized by the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (FAA, P.L. 87-195) and the Arms Export Control Act of 1976 (AECA, P.L. 90-629), as amended, and codified in Title 22 of the U.S. Code. Congress appropriates a significant amount of security assistance funding within the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations. Although funds are appropriated to the State Department or USAID, some of the programs themselves are administered by DOD under the direction and oversight of the Secretary of State. For program descriptions, see Appendix A. State Department security assistance program obligations for the past 10 years are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. U.S. Department of State (DOS)/Agency for International Development (USAID): Security Assistance Program Funding, FY2006-FY2015 Obligations, FY2016 Estimate, and FY2017 Request

(In millions of current U.S. dollars)

|

Program |

FY06 |

FY07 |

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 est. |

FY17 req. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

INCLE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

NADR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

PKO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

ACI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

IMET |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

FMF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

PCCF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

GSCF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: For FY2006-FY2015 data: USAID Foreign Assistance Database, prepared by USAID Economic Analysis and Data Services, April 5, 2017. For PCCF, GSCF, FY2016 estimate, and FY2017 request: the Budget of the U.S. Government, Appendix, Fiscal Years FY2015-2017.

Notes: INCLE = International Narcotics and Law Enforcement; NADR = Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs; PKO = Peacekeeping Operations; ACI = Andean Counterdrug Initiative; IMET = International Military Education and Training; FMF = Foreign Military Financing (FMF); PCCF = Pakistan Counterinsurgency Capability Fund; GSCF = Global Security Contingency Fund. For program descriptions, see Appendix A.

Top DOS Security Assistance Accounts and Recipient Countries

Of the security assistance accounts within the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs since FY2006, FMF is the largest, with typically 55%-65% of annual DOS security assistance funding. INCLE follows with about 20%-30% of State's security assistance funding. In FY2016, FMF and INCLE represent more than 80% of all DOS security assistance obligated that year. (See annual funding for the five major DOS security assistance accounts in Figure 7.)

|

Figure 7. U.S. Department of State (DOS)/Agency for International Development (USAID) Leading Security Assistance Program Funding, FY2006-FY2015 Obligations, FY2016 Estimate, and FY2017 Request |

|

|

Source: For FY2006-FY2015 data: USAID Foreign Assistance Database, prepared by USAID Economic Analysis and Data Services, April 5, 2017. For PCCF, GSCF, FY2016 estimate, and FY2017 request: the Budget of the U.S. Government, Appendix, Fiscal Years FY2015-2017. Notes: ACI = Andean Counterdrug Initiative; PKO = Peacekeeping Operations; NADR = Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs; INCLE = International Narcotics and Law Enforcement; and FMF = Foreign Military Financing. For program descriptions, see Appendix A. |

Israel and Egypt are the top recipients of DOS security assistance, accounting for 52% of State's security assistance obligations in FY2016. FMF accounted for all of the $3.1 billion to Israel and $1.3 billion of the U.S. security assistance to Egypt (see Figure 8).

|

Figure 8. Top 10 Recipients of State Department Security Assistance, FY2016 |

|

|

Source: For DOS information, email communication on September 20, 2017, from State's Legislative Affairs office. |

Department of Defense Security Cooperation Funding Levels

DOD security cooperation programs are authorized by Title 10 of the U.S. Code and provisions in NDAAs. Not all Title 10 and NDAA authorities have funding levels specified by authorization and/or appropriations legislation.6 Funding for some security cooperation authorities may be incorporated into a larger budget category or simply drawn from the defense-wide operations and maintenance budget.7 As a result, accurate accounting of DOD funding levels for all security cooperation programs and activities, in addition to comparison of funding data between the two agencies, remains a challenge. Table 2 provides 10-year obligations data for a majority of significant security cooperation authorities and programs. Table 3 reflects DOD's approximations of counternarcotics support to foreign countries, including both base and OCO funds. DOD funding for foreign counternarcotics support peaked in FY2010, largely due to additional commitments to combat Afghanistan's opium cultivation and opiate trafficking.

Table 2. Department of Defense Security Cooperation Authorities/Programs, FY2006-FY2015 Obligations, FY2016 Appropriations, FY2017 Request or Estimate

(In millions of current U.S. dollars)

|

Program |

FY06 |

FY07 |

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 Req. or Estimate |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

ASFFa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

CERPc |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

CCIFe |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

CTPFf |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

ERIf |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

ITEFa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Building Capacity of Foreign Security Forcesh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

DIRIh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

MODAh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

MSIh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

RCSSh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

CTFPh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

USAIh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

WIh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

CSF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

OCO Lift and Sustain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS), https://www.dfas.mil/dodbudgetaccountreports.html), DOD Budget Justification Materials (http://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials.

Notes: Data are current as of the stated reporting dates. Depending on the account status, slight revisions in these data could occur due to reporting adjustments. Italicized figures reflect outlays. For additional information on authorization levels for authorities not presented in the table see Table A-2 of CRS Report R44602, DOD Security Cooperation: An Overview of Authorities and Issues, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

Abbreviations: ASFF = Afghanistan Security Forces Fund; AIF = Afghanistan Infrastructure Fund; CCIF = Combatant Commanders Initiative Fund; CERP = Commander's Emergency Response Program; CSF=Coalition Support Funds; CTPF = Counterterrorism Partnerships Fund; CTR = Cooperative Threat Reduction; ERI = European Reassurance Initiative; CTFP = Regional Defense Combating Terrorism Fellowship Program; DIRI = Defense Institutional Reform Initiative; ISFF = Iraq Security Forces Fund; ITEF = Iraq Train and Equip Fund; MODA = Ministry of Defense Advisors; MSI = Southeast Asia Maritime Security Initiative; RCSS = Regional Centers for Security Studies USAI = Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative; WIF = Wales Initiative Fund.

For program descriptions, see Appendix B.

a. Data for ASFF, AIF, ISFF, ITEF, and CTR are sourced for the end-of-year (September) AR(M) 1002 Appropriation Status by FY Program and Subaccounts execution reports. The Department of Defense (DOD) Budget Execution and Accounting Reports are available on the Defense Finance and Accounting Service website at https://www.dfas.mil/dodbudgetaccountreports.html.

b. AIF is an expired authority.

c. Data for CERP are sourced from the Army's Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Budget Request justification materials for Overseas Contingency Operations for Fiscal Years (FYs) 2009- 2015. These documents are available on the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) Budget Material public website at http://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials. Data for FYs 2006-2008 are sourced from historical execution documentation.

d. Data for FY2006-FY2008 are sourced from the CTR, O&M, Defense-Wide Budget Request justification materials. These documents are available on the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) Budget Material public website at http://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials.

e. Data for CCIF are sourced from the Joint Staff O&M, Defense-Wide Budget Request justification materials. These documents are available on the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller) Budget Material public website at http://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials.

f. Data for ERI and CTPF are sourced from the Overseas Contingency Operations Train and Equip Funds and Accounts Execution Report as of September 30, 2015. The congressional defense committees received this report on January 11, 2016.

g. ISFF is an expired authority that authorized assistance to the Iraqi security forces. (Original legislation: Section 1512, P.L. 110-181 , as amended.)

h. Data are sourced from DSCA, O&M, Defense-wide budget justification materials for FY2006-FY2017.

Table 3. DOD Counterdrug Support to Foreign Countries, FY2006-FY2017 Estimate

In millions of current U.S. dollars

|

FY06 |

FY07 |

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 est. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: For FY2006-FY2010 data, DOD response to CRS, March 21, 2011; for FY2011-FY2018, DOD drug interdiction and counterdrug activities budget request data on counternarcotics support to foreign countries, provided to CRS annually.

Notes: The data reflect nonbudget quality estimates of DOD counternarcotics support to foreign countries and regions; the DOD drug interdiction and counterdrug activities budget is based on programs, not countries.

Top DOD Security Cooperation Accounts and Recipient Countries

Of the DOD security cooperation accounts in Table 2, Afghanistan Security Forces Fund (ASFF) is the largest, with most years receiving more than 50% of the security cooperation funding, and in FY2011 receiving 74%. Coalition Support Fund (CSF) follows, often between 12%-17% and as much as 26% of the funds. Figure 9 represents the top budget accounts of obligated funds since FY2006. Top recipient countries of DOD security cooperation differ from those of DOS; Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan make up the top DOD country recipients. Figure 10 shows the top defense security cooperation recipients in FY2016. For program descriptions, see Appendix B.

|

Figure 9. Top Five Department of Defense Security Cooperation Authorities/Programs, FY2006-FY2015 Obligations, FY2016 Appropriations, FY2017 Request or Estimate |

|

|

Source: Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS), https://www.dfas.mil/dodbudgetaccountreports.html; DOD Budget Justification Materials, http://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials. Note: Excludes DOD counternarcotics funding. FY17* is requested funds. |

Obligations data disaggregated for DOD's multiple authorities for providing counternarcotics support to foreign security forces were not available for a comparable timeframe. Some reports required by provisions within NDAAs show allocations or expenditures for security cooperation counternarcotics authorities for some fiscal years.8

Selected Issues for Congress

Interagency Terminology

Discussion of military and related assistance to foreign countries is sometimes hindered by a lack of a standard terminology.9 The following terms are frequently used to describe assistance to foreign governments, security services, and militaries:

- Security Assistance (Title 22). Although not defined in Title 22 of U.S. Code, the term security assistance is commonly used to refer to the six budget accounts for which the State Department requests international security assistance appropriations and whose underlying authorities reside in the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (FAA, P.L. 87-195) and Arms Export Control Act of 1976 (AECA, P.L. 90-629), as amended.10

- Security Cooperation (Title 10). DOD uses the term security cooperation to refer to activities authorized by provisions in Title 10 and National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAAs). The FY2017 NDAA defines security cooperation as "any program, activity (including an exercise), or interaction of the Department of Defense with the security establishment of a foreign country to achieve a purpose as follows:

- To build and develop allied and friendly security capabilities for self-defense and multinational operations.

- To provide the armed forces with access to the foreign country during peacetime or a contingency operation.

- To build relationships that promote specific United States security interests."11

- Security Sector Assistance. In April 2013, the Obama Administration issued Presidential Decision Directive 23 (PPD-23). The directive called for an overhaul of U.S. security sector assistance policy and for the creation of a new interagency framework for planning, implementing, assessing, and overseeing security sector assistance. The term security sector assistance refers to all State Department security assistance programs and virtually all DOD security cooperation programs, exercises, and engagements, as well as related activities of USAID, DOJ, and other agencies.12

Security Assistance and Cooperation Funding Transparency

Challenges exist in identifying funding data for security assistance, and data on historical funding are incomplete. Although the State Department has long been required to track most security assistance funding by aid account and on an individual country basis, the Defense Department has not.13 In the latter case, DOD's security cooperation programs and activities were not consistently planned for and budgeted by authority or funding account at the country level; moreover, existing security cooperation authorities may be subject to different congressional notification requirements that may report funding in different formats. As a result, comparisons between security assistance funding provided by both departments have been methodologically fraught.

This report addresses several challenges in securing and analyzing funding information for security sector assistance programs by obtaining obligations over the past decade—the longest historical period for which obligations data are available.14 The report includes obligations data for major DOD security cooperation authorities and programs but not all DOD security cooperation programs.

Prior obstacles to data collection and harmonization between departments on security assistance and cooperation funding may be remedied by provisions of the FY2017 NDAA, which incorporated new or extended existing mechanisms for congressional oversight and public accountability of DOD's security cooperation programs and activities. Beginning with the FY2019 budget, due in 2018, the President is required to submit a formal, consolidated budget request for DOD's security cooperation efforts. Already, DOD is submitting quarterly reports to Congress on the obligation and expenditure of some security cooperation funds. As DOD begins to submit a consolidated security cooperation budget, Congress many consider monitoring DOD's progress in implementing congressional requirements that it more rigorously track security cooperation programs and resources and assess whether funding data provided by DOD will allow for comparisons between agencies and on a per-country basis.

Foreign Military Financing (FMF) Loans

As part of its FY2018 budget proposal, the Trump Administration announced its support for modifications to the structure of some security assistance programs. For example, the Administration proposed shifting some foreign military assistance from grants to loans. Such a change, the Administration argues, would allow "recipients to purchase more American-made weaponry with U.S. assistance, but on a repayable basis."15

To date, Congress has explored the feasibility of transitioning the FMF program from grants to loans. Pursuant to Section 7034(b)(8)(D) of the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), Congress requested the Secretary of State, in coordination with the Secretary of Defense, to provide a report on the impact of transitioning the FMF from grants to loans.16 The Administration's report, delivered to Congress in August 2017, concluded that although such a transition may theoretically allow some recipients to potentially purchase more U.S.-made defense equipment and services, not all foreign countries may qualify for loans due to budget constraints or other factors. Furthermore, the report notes some FMF recipients may be inclined to seek out loans or other type of assistance under more favorable terms from other countries, such as China or Russia, while others may view the use of loans as a signal of declining U.S. commitment.

In S.Rept. 115-152 accompanying S. 1780, Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2018, the Senate Committee on Appropriations concluded it did not support the transition of the FMF program from grants to loans due to lack of study of the Administration's proposal and its unknown impact on U.S. national security interests and on foreign countries receiving U.S. security sector assistance.17 Congress may consider whether a transition to FMS loans would have an effect on the overarching U.S. security sector assistance structure.

State Department Reorganization Plans

In its FY2018 budget proposal, the Trump Administration announced its intention to restructure the use of appropriated funds for diplomatic and development aid and to pursue structural changes at the State Department and USAID. Some Members of Congress have expressed concern about the effects of such a restructuring on U.S. diplomatic and development efforts. The committee reports accompanying the House and Senate versions of the State Department and Foreign Operations Appropriations Acts for FY2018 noted that reorganization could improve efficiency and effectiveness, but raised concern that the process not be undertaken with predetermined targets. Other Members of Congress have also expressed their concerns about the Administration's plans and requested additional information about the role of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in the State Department and USAID reorganization.18 As debates continue, Congress may consider how a State Department reorganization (or realignment) might affect the ability of various bureaus within the department to plan, develop, implement, and coordinate security sector programs.

Implementation of FY2017 NDAA Security Cooperation Provisions

Since December 2016, DOD and State Department officials have begun the process of implementing various provisions under newly established Chapter 16 (Security Cooperation) of Title 10 in U.S. Code. In discussions with CRS, officials have noted that this is a lengthy process, involving several stakeholders, and may take years to be fully realized.

A DOD-State Security Sector Assistance Steering Committee has been established to identify how to best use existing Title 22 and Title 10 authorities in the provision of security sector assistance and ensure that programs are clearly aligned with the core goals of those authorities. A potential hurdle to more efficient coordination identified by both DOD and State Department officials stems from existing budget and planning timelines. Various State Department security assistance and DOD security cooperation programs have dissimilar timelines, posing a challenge for more efficient coordination between activities conducted by the two agencies. For instance, budget planning for the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) program is for two out-years, while some DOD authorities are subject to more immediate planning timelines. DOD officials note that discussions are under way to possibly bridge the gap between planning and budget timelines. DOD officials have also identified budget planning and funding challenges resulting from the lack of a central funding account for security cooperation activities. Staffing requirements at both the State Department and DOD also remain in flux. As the State Department and DOD continue to implement various FY2017 NDAA security cooperation authorities, Congress may consider continuing to evaluate the roles and responsibilities of the Departments of State and Defense in the coordination, budgeting, and approval of U.S. security assistance and cooperation programs and activities.

As Congress considers authorization and appropriations legislation for security assistance and cooperation programs and agencies, questions on improving DOS and DOD coordination, cooperation, and data collection may be important for improved oversight going forward.

Appendix A. DOS/USAID Security Assistance Programs19

This appendix describes the security assistance programs funded through the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations:

- International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INCLE). The INCLE account funds international counternarcotics activities, anticrime programs, and anti-human trafficking programs. In addition, activities conducted under INCLE include rule of law programs, such as law enforcement support and justice sector capacity building. For example, funds support efforts to enhance bilateral and regional cooperation to combat drug trafficking and organized crime in Mexico, drug interdiction and alternative development in Colombia and the Andean region, and judicial system reform and counternarcotics activities in Afghanistan. Although programs authorized under INCLE generally provide nonmilitary support, DOD may play a role if defense articles or services are provided through the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA). State Department authority for counternarcotics programs is contained in Chapter 8 of Part I of the FAA (22 U.S.C. 2291 et seq.).

- Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs (NADR). The NADR account funds a variety of State Department-managed activities aimed at countering proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, supporting antiterrorism training and related activities, and promoting demining operations in developing countries. Programs conducted include border security activities and may involve law enforcement and military personnel. If necessary, DOD, through DSCA, may provide defense articles and services for some NADR programs. DOD may also provide other support, including conducting DOD-funded programs in conjunction with NADR-funded programs.20 NADR is authorized by several provisions of law (Part I, §301, and Part II, Chapters 8-9, of the FAA; §23 of AECA; §504, FREEDOM Support Act (FSA) of 1992 [P.L. 102-511]).

- Peacekeeping Operations (PKO).The PKO account funds programs to provide articles, services, and training for countries participating in international peacekeeping operations, including United Nations (U.N.) and regional operations. Most support under PKO is provided to foreign militaries. PKO programs include efforts to diminish and resolve conflicts, address terrorism threats, and reform military establishments. In addition, PKO funds U.S. military participation in the Multilateral Force and Observers (MFO) in the Sinai.

- DOD sometimes uses its own funds to complement or assist PKO-funded programs. In addition, DOD provides support to the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI) to train, equip, and support the deployment of foreign military troops and police for U.N. and regional peacekeeping missions. DOD, through DSCA, may also contribute defense articles and services to other PKO-funded missions such as maritime security and counterpoaching activities. PKO programs are authorized by FAA Sections 551-553 (22 U.S.C. 2348).

- Andean Counterdrug Initiative (ACI). The ACI account provided assistance from FY2002 to FY2008 (although some obligations continue to flow) to Colombia, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela to address drug trafficking and economic development issues. ACI was authorized by 22 U.S.C. 2291a-j (Chapter 8, Part I, §§481-490, FAA, as amended).

- International Military Education and Training (IMET). IMET provides grant financial assistance to selected foreign military and civilian personnel for training and education on U.S. military practices and standards, including democratic values. For example, IMET sends foreign personnel to the military service senior-level war colleges and the National Defense University, as well as to military service Command and Staff Colleges, where they take basic and advanced officer training. In 1990, the program was expanded (E-IMET) to provide opportunities for foreign civilian defense and related personnel to attend educational programs promoting responsible defense resource management, in addition to other purposes. The State Department controls the funds and has policy authority; DOD, through DSCA, administers this program. IMET is authorized by FAA Sections 541-543 (22 U.S.C. 2347).

- Foreign Military Financing (FMF). The FMF program provides financing of the purchase of defense articles, services, and training (usually on a grant basis) through the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) system—the U.S. government's conduit for selling weapons, equipment, and associated training to friendly foreign countries—or through Direct Commercial Sales (DCS). The State Department is primarily responsible for determining which nations are to receive military assistance. DOD, through the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), implements this program. FMF is authorized by Section 23 of the AECA (22 U.S.C. 2763).

- Pakistan Counterinsurgency Capability Fund (PCCF). Section 1224 (NDAA FY2010, P.L. 111-84), as amended, authorized the Pakistan Counterinsurgency Fund (PCF) and permitted the Secretary of Defense, with Secretary of State concurrence, to provide assistance for Pakistan's security forces to bolster their counterinsurgency efforts. Title III of the Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2009 (P.L. 111-32) appropriated $400 million for PCF. After authorization expired, the Secretary of State assumed responsibility in subsequent fiscal years under the name Pakistan Counterinsurgency Capability Fund with funding from State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs appropriations. PCCF was authorized by 22 U.S.C. 2291, 22 U.S.C. 2311, 22 U.S.C. 2347, 22 U.S.C. 2348, 22 U.S.C. 2349aa, and 22 U.S.C. 2763.

- Global Security Contingency Fund (GSCF). GSCF is a joint DOD-DOS fund to provide assistance to enhance the capabilities of a country's military or other national security forces to conduct border and maritime security, internal defense, and counterterrorism operations, or participate in military, stability, or peace support operations. It is also authorized to support the justice sector in countries where conflict or instability challenges the capacity of civilian providers. The GSCF authority provides authority for DOD to transfer up to $200 million per fiscal year to the fund, but caps DOD contributions to each project at 80% of the cost. GSCF is authorized by Section 1207 (NDAA FY2012, P.L. 112-81), as amended. GSCF authority expired on September 30, 2017.21

Appendix B. Major DOD Security Cooperation Authorities/Programs22

This appendix describes DOD security cooperation programs:

- Afghanistan Security Forces Fund (ASFF). ASFF permits the Secretary of Defense to provide assistance to the security forces of Afghanistan, which may include provision of equipment, supplies, services, training, facility and infrastructure repair, renovation, and construction and funding. It also authorizes the Secretary of Defense to accept contributions to the ASFF from non-U.S. government sources, and to transfer ASFF funds to other accounts. ASFF is authorized by Section 1513 (FY2008 NDAA, P.L. 110-181), as amended.

- Afghanistan Infrastructure Fund (AIF). AIF allows the Secretary of Defense and Secretary of State jointly to develop and carry out infrastructure projects in Afghanistan. The authority expired on September 30, 2015, but FY2017 appropriations legislation (P.L. 115-31) makes funds appropriated to the Afghanistan Security Forces Fund (ASFF) available for additional costs associated with existing projects funded under AIF. AIF was authorized by Section 1217 (FY2011 NDAA, P.L. 111-383).

- Building Capacity of Foreign Security Forces. Commonly described as DOD's "Global Train and Equip" authority, the Secretary of Defense may build the capacity of a foreign country's national military forces to enable such forces to conduct counterterrorism operations or to support or participate in military, stability, and peace support operations that benefit U.S. national security interests. The Secretary may also authorize activities to enable a foreign country's maritime or border security forces, and other national-level security forces with counterterrorism responsibilities, to conduct counterterrorism operations.

- DOD's global train and equip activities were originally authorized by Section 1206 (FY2006 NDAA, P.L. 109-163), as amended. Section 1206 was the first major DOD authority to be used expressly for the purpose of training and equipping the national military forces of foreign countries worldwide. The authority was later codified as 10 U.S.C. 2282 in the FY2015 NDAA (P.L. 113-291). Activities permitted under 10 U.S.C. 2282 have been incorporated into a new, broader global train and equip authority established by Section 1241(c) of the FY2017 NDAA: 10 U.S.C. 333.23

- Commander's Emergency Response Program (CERP). CERP authorizes U.S. military commanders in Afghanistan to carry out small-scale projects to address urgent humanitarian relief or urgent reconstruction needs within their areas of responsibility. CERP is authorized by Section 1201 (FY2012 NDAA P.L. 112-81), as amended.

- Combatant Commanders Initiative Fund (CCIF). CCIF provides discretionary funding for combatant commanders to conduct various activities, especially in response to unforeseen contingencies. A few permitted uses are related to foreign assistance. These include humanitarian and civic assistance, urgent and unanticipated humanitarian relief, and reconstruction. Permitted activities also include force training, contingencies, selected operations, command and control, joint exercises, military education and training for military and related civilian personnel of foreign countries, including transportation, translation, and administrative expenses (up to $5 million per year). Up to $10 million per year may be spent to sponsor the participation of foreign countries in joint exercises. 10 U.S.C. 166a authorizes the fund, but activities are carried out under other authorities.

- Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR). The purpose of CTR is to (1) facilitate the elimination and safe and secure transport and storage of chemical, biological, or other weapons (and weapons components, related materials, and delivery vehicles), and (2) facilitate the safe and secure transport and storage of nuclear weapons, nuclear weapons-usable or high-threat radiological materials, nuclear weapons components, and delivery vehicles, as well as the elimination of nuclear weapons, components, and delivery vehicles. CTR also authorizes the Secretary to prevent the proliferation of nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons, components, and related materials, technology, and expertise, as well as of weapons of mass destruction-related materials. The FY2017 NDAA authorized $325.6 million to be available for obligation in FY2017, FY2018, and FY2019. CTR is authorized by Sections 1301-1352 (FY2015 NDAA, P.L. 113-291), as amended.

- Counterterrorism Partnerships Fund (CTPF). CTPF provides support and assistance to foreign security forces or other groups or individuals to conduct, support, or facilitate counterterrorism and crisis response activities pursuant to Section 1534 of the FY2015 NDAA. Section 1534 of FY2015 NDAA stipulates that funds may be transferred to other accounts for use under existing DOD authority established by "any other provision of law." DOD may conduct CTPF activities only in areas of responsibility of the U.S. CENTCOM and AFRICOM, unless the Secretary of Defense determines that authority needs to be applied elsewhere to address threats to U.S. national security.24 Section 1510 (FY2016 NDAA, P.L. 113-235), as amended, authorizes the appropriation of funds for CTPF.

- Coalition Support Fund (CSF). CSF Authorizes the Secretary of Defense to reimburse key cooperating countries for logistical, military, and other support, including access, to or in connection with U.S. military operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Syria and to assist such nations with U.S.-funded equipment, supplies, and training. Aggregate amount of reimbursements may not exceed $1.1 billion between October 1, 2016, and December 31, 2017. Additional reimbursement restrictions apply to Pakistan for certain counterterrorism activities and activities along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region. CSF is authorized by Section 1233 (FY2008 NDAA, P.L. 110-181), as amended.

- Defense Institutional Reform Initiative (DIRI). The Defense Institution Reform Initiative (DIRI) is conducted through the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) Rule of Law program under 10 U.S.C. 168, military-to-military contacts authority, and 10 U.S.C. 1051, developing country participation in multilateral, bilateral, or regional events. DIRI supports foreign defense institutions and related agencies by determining institutional needs and developing projects to meet them. DIRI both scopes out projects for execution under the MODA and conducts its own military-to-military informational engagements.25

- European Reassurance Initiative (ERI). ERI permits the Secretary of Defense to provide assistance to reassure NATO allies and improve the security and capacity of U.S. partners. ERI permits an increased U.S. military presence in Europe, additional exercises and training with allies and partners, improvements to infrastructure to enhance responsiveness, prepositioning U.S. equipment in Europe, and increasing efforts to build partner capacity for new NATO members and other partners. ERI is authorized by Section 1535 (FY2015 NDAA, P.L. 113-291).

- Iraq Train and Equip Fund (ITEF). ITEF authorizes the Secretary of Defense to provide up to $630 million in assistance to Iraq and partner nations to defend against the Islamic State and its allies, which may include training, equipment, logistics support, supplies, services, stipends, facility and infrastructure repair, renovation, and sustainment. ITEF is authorized by Section 1236 (FY2015 NDAA, P.L. 113-291), as amended.

- Logistic Support for Allied Forces in Combined Operations: 10 U.S.C. 127d (Global Lift and Sustain) authorizes the Secretary of Defense to provide logistics, supplies, and services to allied forces participating in a combined operation with the United States, as well as to a nonmilitary logistics, security, or similar agency of an allied government if it would benefit U.S. Armed Forces.26

- Ministry of Defense Advisors Program (MODA). The MODA program allows the Secretary of Defense to assign civilian Department of Defense employees as advisors to foreign ministries of defense or security agencies serving a similar defense function to provide advice and other training and to assist in building core institutional capacity, competencies, and capabilities. MODA is authorized by Section 1081 (FY2012 NDAA, P.L. 112-81), as amended.27

- Regional Centers for Security Studies (RCSS). DOD Regional Centers for Security Studies function to provide bilateral and multilateral research, communications, and exchange of ideas involving military and civilian participants. 10 U.S.C. 184 authorizes the administration of Regional Centers.28

- Regional Defense Combating Terrorism Fellowship Program (CTFP). The program allows the Secretary of Defense to use funds appropriated to DOD to pay any costs associated with the education and training of foreign military officers, ministry of defense officials, or security officials at military or civilian educational institutions, regional centers, conferences, seminars, or other training programs conducted under the Regional Defense Combating Terrorism Fellowship Program. The total amount of funds spent under this authority may not exceed $35 million per fiscal year. The program is authorized by 10 U.S.C. 2249c.

- Southeast Asia Maritime Security Initiative (MSI). MSI permits the Secretary of Defense to increase maritime security and maritime domain awareness of specific foreign countries along the South China Sea by providing assistance and training to national military or other security forces whose functional responsibilities include maritime security missions.

- Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI). The USAI permits the Secretary of Defense to provide up to $300 million in FY2016 and $350 million in FY2017 for security assistance and intelligence support, including training, equipment, logistics support, and supplies and services to military and other security forces of Ukraine. USAI is authorized by Section 1250 (FY2016 NDAA, P.L. 114-92), as amended.

- Wales (formerly Warsaw) Initiative Fund (WIF). The WIF was formerly named the Warsaw Initiative Fund, but was renamed after the Wales NATO summit in September 2014. It supports the participation of 16 developing countries in the State Department-led Partnership for Peace Program. This fund has enabled a wide range of assistance, including equipment and training, but is currently used primarily for defense institution building, according to DSCA officials. Activities funded by WIF are conducted using the authority of three statutes (10 U.S.C. 168, 10 U.S.C. 1051, and 10 U.S.C. 2010).29