Background

Federal law provides that all aliens1 must enter the United States pursuant to the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). The two major categories of aliens in the INA are (1) immigrants, and (2) nonimmigrants, who are admitted for temporary reasons (e.g., students, tourists, temporary workers, or business travelers). Foreign nationals who lack proper immigration authorization generally fall into three categories: (1) those who are admitted legally and then overstay their nonimmigrant visas, (2) those who enter the country surreptitiously without inspection, and (3) those who are admitted on the basis of fraudulent documents. In all three instances, the aliens are in violation of the INA and subject to removal.

Temporary Protected Status (TPS), codified in INA §244,2 provides temporary lawful status to foreign nationals in the United States from countries experiencing armed conflict, natural disaster, or other extraordinary circumstances that prevent their safe return. This report begins by situating TPS in the context of humanitarian responses to migration. Another form of blanket relief from removal3—Deferred Enforced Departure (DED)—is also described, as is the historical use of these relief mechanisms. This report then provides data on the countries currently designated for TPS, including the conditions that have contributed to their designation. Past legislation to provide lawful permanent resident status to certain TPS-designated foreign nationals is also described. The report concludes with examples of activity in the 115th Congress related to TPS.

Humanitarian Response

As a State Party to the 1967 United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (hereinafter, U.N. Protocol),4 the United States agrees to the principle of nonrefoulement, which asserts that a refugee should not be returned to a country where he/she faces serious threats to his/her life or freedom. (This is now considered a rule of customary international law.) Nonrefoulement is embodied in several provisions of U.S. immigration law. Most notably, it is reflected in INA provisions requiring the government to withhold the removal of a migrant to a country in which the migrant's life or freedom would be threatened on the basis of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.5

The legal definition of a refugee in the INA, which is consistent with the U.N. Protocol, specifies that a refugee is a person who is unwilling or unable to return to his/her country of nationality or habitual residence because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.6 This definition also applies to individuals seeking asylum. Under the INA, refugees and asylees differ on the physical location of the persons seeking the status. Those who are displaced abroad to a country other than their home country apply for refugee status, while those who are in the United States or at a U.S. port of entry apply for asylum.7 Other migrants in the United States who may elicit a humanitarian response do not meet the legal definition for asylum; under certain circumstances these persons may be eligible for relief from removal through TPS or DED.

Temporary Protected Status

TPS is a blanket form of humanitarian relief. It is the statutory embodiment of "safe haven" for foreign nationals within the United States who may not meet the legal definition of refugee or asylee but are nonetheless fleeing—or reluctant to return to—potentially dangerous situations. TPS was established by Congress as part of the Immigration Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-649). The statute specifies that the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS),8 in consultation with other government agencies (most notably the Department of State), may designate a country for TPS under one or more of the following conditions: ongoing armed conflict in a foreign state that poses a serious threat to personal safety; a foreign state request for TPS because it temporarily cannot handle the return of nationals due to environmental disaster; or extraordinary and temporary conditions in a foreign state that prevent migrants from safely returning. A state may not be designated for TPS if the Secretary of DHS finds that allowing its migrants to temporarily stay in the United States is against the U.S. national interest.9

The Secretary of DHS can issue TPS for periods of 6 to 18 months and can extend these periods if conditions do not change in the designated country.10 To obtain TPS, eligible migrants within the United States must pay specified fees11 and submit an application to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) before the deadline set forth in the Federal Register notice announcing the TPS designation. The application must include supporting documentation as evidence of eligibility (e.g., a passport issued by the designated country and records showing continuous physical presence in the United States since the date established in the TPS designation).12 The statute specifies grounds of inadmissibility that cannot be waived, including those relating to criminal convictions and the persecution of others.13

Individuals granted TPS are not considered to be permanently residing in the United States "under color of law," may be deemed ineligible for public assistance by a state, and may travel abroad only with the prior consent of the DHS Secretary. TPS does not provide a path to lawful permanent residence or citizenship.14 DHS has indicated that information it collects when a migrant registers for TPS may be used to enforce immigration law or in any criminal proceeding.15 In addition, withdrawal of an alien's TPS may subject the alien to exclusion or deportation proceedings.16

Deferred Enforced Departure

In addition to TPS, there is another form of blanket relief from removal known as deferred enforced departure (DED),17 formerly known as extended voluntary departure (EVD).18 DED is a temporary, discretionary, administrative stay of removal granted to aliens from designated countries. Unlike TPS, a DED designation emanates from the President's constitutional powers to conduct foreign relations and has no statutory basis. DED was first used in 1990 and has been used a total of five times (see "Historical Patterns of Blanket Relief"). Currently, certain Liberian nationals are designated under DED through March 31, 2018.

DED and EVD have been used on a country-specific basis to provide relief from removal at the President's discretion, usually in response to war, civil unrest, or natural disasters.19 When Presidents grant DED, through an executive order or presidential memorandum, they generally provide eligibility guidelines, such as continuous presence in the United States since a specific date. Unlike TPS, the Secretary of State does not need to be consulted when DED is granted.

DED continues to be used to provide relief to nationals of countries the Administration deems appropriate. The executive branch's position has been that all blanket relief decisions require balancing foreign policy, humanitarian, and immigration concerns. In contrast to recipients of TPS, migrants who benefit from DED are not required to register for the status with USCIS unless they want work authorization.20 Instead, DED is triggered when a protected migrant is identified for deportation.

Historical Patterns of Blanket Relief

In 1990, when Congress enacted the TPS statute, it also granted TPS for 18 months to Salvadoran nationals who were residing in the United States. Since then, the Attorney General (and, later, the Secretary of DHS),21 in consultation with the State Department, has granted TPS to migrants in the United States from the following countries: Liberia, Kuwait, Rwanda, Lebanon, the Kosovo Province of Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Angola, Sierra Leone, Burundi, and Guinea; none of these 10 countries are currently designated for TPS.22

Rather than extending the initial Salvadoran TPS when it expired in 1992, the George H. W. Bush Administration granted DED to an estimated 190,000 Salvadorans through December 1994. This Administration also granted DED to about 80,000 Chinese nationals in the United States following the Tiananmen Square massacre in June 1989, and these individuals retained DED status through January 1994. In December 1997, President Bill Clinton instructed the Attorney General to grant DED to Haitian nationals in the United States for one year, providing time for the Administration to work with Congress on long-term legislative relief for Haitians.23 President George W. Bush directed that DED be provided to Liberian nationals whose TPS was expiring in September 2007; this status was extended several times by President Barack Obama and is currently set to expire on March 31, 2018.24

Countries Designated for Temporary Protections

Approximately 437,000 foreign nationals from the following 10 countries have TPS as of October 2017: El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. In addition, certain Liberian nationals are covered by a designation of DED (see "Liberia" section below). Table 1 shows the current TPS-designated countries, the date from which individuals are required to have continuously resided in the United States, and the designation's expiration date. In addition, Table 1 shows the approximate number of individuals from each country who registered during the previous registration period and the number of individuals with TPS as of October 12, 2017.

|

Country |

Arrival Datea |

Expiration Date |

Expected Reregistrantsb |

Individuals with TPSc |

|

El Salvador |

February 13, 2001 |

September 9, 2019 |

195,000 |

262,526 |

|

Haiti |

January 12, 2011 |

July 22, 2019 |

46,000 |

58,557 |

|

Honduras |

December 30, 1998 |

July 5, 2018 |

57,000 |

86,031 |

|

Nepal |

June 24, 2015 |

June 24, 2018 |

8,950 |

14,791 |

|

Nicaragua |

December 30, 1998 |

January 5, 2019 |

2,550 |

5,305 |

|

Somalia |

May 1, 2012 |

September 17, 2018 |

250 |

499 |

|

South Sudan |

January 25, 2016 |

May 2, 2019 |

70 |

77 |

|

Sudan |

January 9, 2013 |

November 2, 2018 |

1,040 |

1,048 |

|

Syria |

August 1, 2016 |

March 31, 2018 |

5,800 |

6,916 |

|

Yemen |

January 4, 2017 |

September 3, 2018 |

1,000 |

1,116 |

|

Total |

317,660 |

436,866 |

Source: CRS compilation of information from Federal Register announcements and USCIS data.

a. The arrival date represents the date from which individuals are required to have continuously resided in the United States in order to qualify for TPS and is determined by the most recent TPS designation for that country. A migrant is not considered to have failed this requirement for a "brief, casual, and innocent" absence. 8 U.S.C. §1254a(c) and 8 C.F.R. §244.1.

b. Data from Federal Register notices for each country. These data represent the number of individuals who registered during the previous registration period.

c. Data provided to CRS by USCIS. These data reflect individuals with TPS as of October 12, 2017; include some individuals who have since adjusted to another status, and may include individuals who have left the country or died; and do not necessarily include all migrants from the specified countries who are in the United States and are eligible for the status.

Central America

The only time Congress has granted TPS was in 1990 (as part of the law establishing TPS) to eligible Salvadoran nationals in the United States.25 In the aftermath of Hurricane Mitch in November 1998, then-Attorney General Janet Reno announced that she would temporarily suspend the deportation of migrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. On January 5, 1999, the Attorney General designated Honduras and Nicaragua for TPS due to extraordinary displacement and damage from Hurricane Mitch.26 Prior to leaving office in January 2001, the Clinton Administration said it would temporarily halt deportations to El Salvador because of a major earthquake. In 2001, the George W. Bush Administration decided to grant TPS to Salvadoran nationals following two earthquakes that rocked the country.27

Over the years, the George W. Bush Administration granted, and the Obama Administration extended, TPS to Central Americans from El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua on the rationale that it was still unsafe for nationals to return due to the disruption of living conditions from environmental disasters.

Beginning in late 2017, the Trump Administration announced decisions to terminate TPS for Nicaragua and El Salvador and to put on hold a decision about Honduras. On November 6, 2017, DHS announced that TPS for Nicaragua would end on January 5, 2019—12 months after its last designation would have expired—due to nearly completed recovery efforts following Hurricane Mitch.28 On the same day, DHS announced that more information was necessary to make a determination about TPS for Honduras; as a result, statute dictates that its status be extended for six months. Thus, the current expiration date for Honduras is July 5, 2018, and a decision to extend or terminate it is due in early May.29 On January 8, 2018, DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen announced her decision to terminate TPS for El Salvador—whose nationals account for about 60% of TPS recipients—after an 18-month transition period. El Salvador's TPS is now scheduled to end on September 9, 2019.30

The large number of Central Americans with TPS, along with their length of U.S. residence and resulting substantial economic and family ties, have led some to support extending TPS for Central Americans and Salvadorans in particular. Supporters have argued that ongoing violence and political unrest have left these countries unable to adequately handle the return of their nationals and that a large-scale return could have negative consequences for the United States economy and labor supply, American families, foreign relations, and the flow of remittances sent by Central Americans living in the United States to their relatives in Central America.31 Opponents have argued that ending TPS for these countries is a move toward correctly interpreting the original intent of the program—to provide temporary safe haven. There is some support in Congress for a legislative means of allowing TPS recipients with several years of U.S. residence to remain in the United States permanently; others argue that no special consideration should be given to allow these individuals to stay in the United States.

Haiti

The devastation caused by the January 12, 2010, earthquake in Haiti prompted calls for the Obama Administration to grant TPS to Haitian nationals in the United States.32 The scale of the humanitarian crisis after the earthquake—with estimates of thousands of Haitians dead and reports of the total collapse of Port au Prince's infrastructure—led DHS on January 15, 2010, to grant TPS for 18 months to Haitian nationals who were in the United States as of January 12, 2010. At the time, then-DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano stated: "Providing a temporary refuge for Haitian nationals who are currently in the United States and whose personal safety would be endangered by returning to Haiti is part of this Administration's continuing efforts to support Haiti's recovery."33 On July 13, 2010, DHS announced an extension of the TPS registration period for Haitian nationals, citing difficulties nationals were experiencing in obtaining documents to establish identity and nationality, and in gathering funds required to apply for TPS.34

DHS extended the TPS designation for Haiti on May 17, 2011, enabling eligible Haitian nationals who arrived in the United States up to one year after the earthquake to receive TPS. The redesignation targeted individuals who were allowed to enter the United States immediately after the earthquake on temporary visas or humanitarian parole,35 but were not covered by the initial TPS designation.36 The extension of Haiti's TPS designation was for 18 months, through January 22, 2013.37 Subsequently, then-Secretary Jeh Johnson extended Haiti's designation several times, through July 22, 2017.38

A May 2, 2017, letter from members of the Congressional Black Caucus to then-DHS Secretary John Kelly urged an 18-month extension of TPS for Haiti, citing continued recovery difficulties from the 2010 earthquake that killed over 300,000 people, an ongoing cholera epidemic, and additional damages from Hurricane Matthew in 2016.39 On May 24, 2017, then-Secretary Kelly extended Haiti's TPS designation for six months (the minimum allowed by statute), from its planned expiration on July 22, 2017, to January 22, 2018, and encouraged beneficiaries to prepare to return to Haiti should its designation be terminated after six months.40 An October 4, 2017, letter from the Haitian ambassador to Acting DHS Secretary Elaine Duke requested that Haiti's designation be extended for an additional 18 months.41 On November 20, 2017, DHS announced its decision to terminate TPS for Haiti, with an 18-month transition period. Its designation will now end on July 22, 2019.42

Liberia

Liberians in the United States first received TPS in March 1991 following the outbreak of civil war. Although that war ended, a second civil war began in 1999 and escalated in 2000.43 Approximately 10,000 Liberians in the United States were given DED in 1999 after their TPS expired. Their DED status was subsequently extended to September 29, 2002. On October 1, 2002, Liberia was redesignated for TPS for a period of 12 months, and that status continued to be extended. On September 20, 2006, the George W. Bush Administration announced that TPS for Liberia would expire on October 1, 2007, but that this population would be eligible for DED until March 31, 2009. On March 23, 2009, President Obama extended DED for those Liberians until March 31, 2010, and several times thereafter.44

As a result of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014, eligible Liberians were again granted TPS, as were eligible Sierra Leoneans and Guineans.45 On September 26, 2016, DHS issued a notice for Liberia providing a six-month extension of TPS benefits, to May 21, 2017, to allow for an "orderly transition" of affected persons' immigration status, and did the same for similarly affected Sierra Leoneans and Guineans. This action voided a previously scheduled November 21, 2016, expiration of TPS for all three countries.46

Liberia's DED status was last extended by President Obama through March 31, 2018, for a specially designated population of Liberians who had been residing in the United States since October 2002.47 Approximately 745 Liberians have approved employment authorization documents (EADs) under that DED directive.48 This number does not reflect all Liberians who might be covered under this DED announcement—only those who applied for and received an EAD.

Nepal

Nepal was devastated by a massive earthquake on April 25, 2015, killing over 8,000 people. The earthquake and subsequent aftershocks demolished much of Nepal's housing and infrastructure. Over half a million homes were reportedly destroyed.49 On June 24, 2015, citing a substantial but temporary disruption in living conditions as a result of the earthquake, then-DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson designated Nepal for TPS for an 18-month period.50 TPS for Nepal was extended in October 2016, and is set to expire on June 24, 2018.51 A decision to extend or terminate Nepal's TPS is due by the end of April 2018.

Somalia

Somalia has endured decades of chronic instability and humanitarian crises. Since the collapse of the authoritarian Siad Barre regime in 1991, it has lacked a viable central authority capable of exerting territorial control, securing its borders, or providing security and services to its people. 52 Somalia was first designated for TPS in 1991 based on extraordinary and temporary conditions "that prevent[ed] aliens who are nationals of Somalia from returning to Somalia in safety."53 Through 22 subsequent extensions or redesignations, Somalia has maintained TPS due to insecurity and ongoing armed conflict that present serious threats to the safety of returnees. DHS announced the latest extension—for 18 months—on January 17, 2017, and its current expiration date is September 17, 2018.54 A decision to extend or terminate Somalia's TPS is due in July 2018.

Sudan and South Sudan

Decades of civil war preceded South Sudan's secession from the Republic of Sudan in 2011.55 Citing both ongoing armed conflict and extraordinary and temporary conditions that would prevent the safe return of Sudanese nationals, the Attorney General designated Sudan for TPS on November 4, 1997. Since then, Sudan has been redesignated or had its designation extended 14 times.

On July 9, 2011, South Sudan became a new nation.56 With South Sudan's independence from the Republic of Sudan, questions arose about whether nationals of the new nation would continue to be eligible for TPS. In response, the DHS Secretary designated South Sudan for TPS on October 17, 2011.57 TPS has since been extended or redesignated four times due to ongoing armed conflict and extraordinary and temporary conditions in South Sudan, including "ongoing civil war marked by brutal violence against civilians, egregious human rights violations and abuses, and a humanitarian disaster on a devastating scale across the country." 58 The latest extension was for 18 months and expires on May 2, 2019.59

Meanwhile, citing improved conditions in Sudan, including a reduction in violence and an increase in food harvests, then-Acting DHS Secretary Elaine Duke announced in September 2017, that Sudan's TPS designation would expire on November 2, 2018.60

Syria

The political uprising of 2011 in Syria grew into an intensely violent civil war that displaced over 6 million people by 2014.61 On March 29, 2012, then-Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano designated the Syrian Arab Republic (Syria) for TPS through September 30, 2013, citing temporary extraordinary conditions that would make it unsafe for Syrian nationals already in the United States to return to the country.62 In that initial granting of TPS, Secretary Napolitano made clear that DHS would conduct full background checks on Syrians registering for TPS.63 TPS for Syrian nationals has since been extended, most recently on August 1, 2016, through March 31, 2018. The extension was also accompanied by a redesignation, which updated the required arrival date into the United States for Syrians from January 5, 2015, to August 1, 2016.64 A decision to extend or terminate Syria's TPS is due at the end of January 2018.

Yemen

On September 3, 2015, then-Secretary Jeh Johnson designated Yemen for TPS through March 3, 2017, due to ongoing armed conflict in the country.65 A 2015 DHS press release stated that "requiring Yemeni nationals in the United States to return to Yemen would pose a serious threat to their personal safety."66 The civil war in Yemen reached new levels in 2017. The United Nations estimated that the civilian death toll had reached 10,000, and the World Food Program reported that 60% of Yemenis, or 17 million people, were in "crisis" or "emergency" food situations.67 Relief efforts in the region have been complicated by ongoing violence and considerable damage to the country's infrastructure. On January 4, 2017, DHS extended and redesignated Yemen's current TPS designation through September 3, 2018. The redesignation updated the required arrival date into the United States for individuals from Yemen from September 3, 2015, to January 4, 2017.68 The Federal Register notice explained that the "continued deterioration of the conditions for civilians in Yemen and the resulting need to offer protection to individuals who have arrived in the United States after the eligibility cutoff dates" warranted the redesignation of TPS.69 A decision to extend or terminate Yemen's TPS is due in early July 2018.

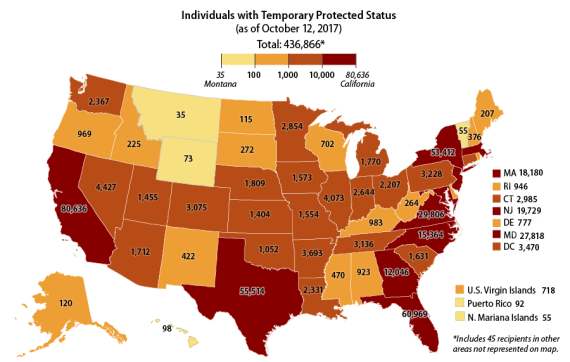

State of Residence of TPS Recipients

Individuals with TPS reside in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the territories. The highest populations live in traditional immigrant gateway states: California, Florida, Texas, and New York. In addition to these four, six other states had at least 10,000 TPS recipients as of October, 2017: Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Georgia. Hawaii, Wyoming, Vermont, and Montana had fewer than 100 individuals with TPS. See Figure 1 and Table 2.

|

State |

Individuals with TPS |

State |

Individuals with TPS |

|

Alabama |

923 |

Nevada |

4,427 |

|

Alaska |

120 |

New Hampshire |

376 |

|

Arizona |

1,712 |

New Jersey |

19,729 |

|

Arkansas |

3,693 |

New Mexico |

422 |

|

California |

80,636 |

New York |

53,412 |

|

Colorado |

3,075 |

North Carolina |

15,364 |

|

Connecticut |

2,985 |

North Dakota |

115 |

|

Delaware |

777 |

Ohio |

2,207 |

|

District of Columbia |

3,470 |

Oklahoma |

1,052 |

|

Florida |

60,969 |

Oregon |

969 |

|

Georgia |

12,046 |

Pennsylvania |

3,228 |

|

Hawaii |

98 |

Rhode Island |

946 |

|

Idaho |

225 |

South Carolina |

1,631 |

|

Illinois |

4,073 |

South Dakota |

272 |

|

Indiana |

2,644 |

Tennessee |

3,136 |

|

Iowa |

1,573 |

Texas |

55,514 |

|

Kansas |

1,404 |

Utah |

1,455 |

|

Kentucky |

983 |

Vermont |

55 |

|

Louisiana |

2,331 |

Virginia |

29,806 |

|

Maine |

207 |

Washington |

2,367 |

|

Maryland |

27,818 |

West Virginia |

264 |

|

Massachusetts |

18,180 |

Wisconsin |

702 |

|

Michigan |

1,770 |

Wyoming |

73 |

|

Minnesota |

2,854 |

U.S. Virgin Islands |

718 |

|

Mississippi |

470 |

Puerto Rico |

92 |

|

Missouri |

1,554 |

Northern Mariana Islands |

55 |

|

Montana |

35 |

Other |

45 |

|

Nebraska |

1,809 |

Total |

436,866 |

Source: CRS calculation of data provided by USCIS.

Notes: These data reflect individuals with TPS as of October 12, 2017; data include some individuals who have since adjusted to another status and may include individuals who have moved to another state, left the country, or died; data do not necessarily include all migrants from the specified countries who are in the United States and are eligible for the status.

Adjustment of Status

A grant of TPS does not provide a migrant with a designated pathway to lawful permanent resident (LPR) status; however, a TPS recipient is not barred from adjusting to nonimmigrant or immigrant status if he or she meets the requirements. There are statutory limitations on Congress providing adjustment of status to TPS recipients.70

Over the years, Congress has provided eligibility for LPR status to groups of nationals who had been given temporary relief from removal. In 1992, Congress enacted legislation allowing Chinese nationals who had DED following the Tiananmen Square massacre to adjust to LPR status (P.L. 102-404). The Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA) (Title II of P.L. 105-100), which became law in 1997, provided eligibility for LPR status to certain Nicaraguans, Cubans, Guatemalans, Salvadorans, and nationals of the former Soviet bloc who had applied for asylum and had been living in the United States for a certain period of time. The 105th Congress passed the Haitian Refugee Immigration Fairness Act, enabling Haitians who had filed asylum claims or who were paroled into the United States before December 31, 1995, to adjust to legal permanent residence (P.L. 105-277).

Legislation that would have allowed nationals from various countries that have had TPS to adjust to LPR status received action in past Congresses, but was not enacted. For instance, the Senate-passed comprehensive immigration reform bill in the 113th Congress (S. 744) did not include specific provisions for foreign nationals with TPS to adjust status, but many would have qualified for the registered provisional immigrant status that S. 744 would have established.71

Selected Activity in the 115th Congress

The 115th Congress has introduced various proposals related to TPS. Some bills would extend or expand TPS designation for certain countries,72 or provide adjustment to LPR status for TPS recipients who have been living in the United States for several years.73 Other bills seek to limit the program by transferring authority from DHS to Congress to designate foreign states; making unauthorized aliens and members of criminal gangs ineligible; restricting the criteria for designating a foreign state, and making TPS recipients subject to detention and expedited removal.74

Some Members of the 115th Congress have expressed support through resolutions75 or letters76 to the Administration for continuing the designation of certain countries for TPS. In addition, some Members have expressed support for designating additional countries for TPS.77