Introduction

This report is part of a suite of reports that address appropriations for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for FY2017. It specifically discusses appropriations for the components of DHS included in the third title of the homeland security appropriations bill—the National Protection and Programs Directorate (NPPD), the Office of Health Affairs (OHA), and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Collectively, Congress has labeled these components in recent years as "Protection, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery."

The report provides an overview of the Obama Administration's FY2017 request for these components, the appropriations proposed by the appropriations committees in response, and those enacted in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31; Division F is the Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2017), and the Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-56, Division B). The report includes information on provisions throughout the bills and reports that directly affect these components.

The suite of CRS reports on homeland security appropriations tracks legislative action and congressional issues related to DHS appropriations, with particular attention paid to discretionary funding amounts. The reports do not provide in-depth analysis of specific issues related to mandatory funding—such as retirement pay—nor do they systematically follow other legislation related to the authorization or amending of DHS programs, activities, or fee revenues.

Discussion of appropriations legislation involves a variety of specialized budgetary concepts. The Appendix to CRS Report R44621, Department of Homeland Security Appropriations: FY2017, explains several of these concepts, including budget authority, obligations, outlays, discretionary and mandatory spending, offsetting collections, allocations, and adjustments to the discretionary spending caps under the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25). A more complete discussion of those terms and the appropriations process in general can be found in CRS Report R42388, The Congressional Appropriations Process: An Introduction, coordinated by [author name scrubbed], and the Government Accountability Office's A Glossary of Terms Used in the Federal Budget Process.1

Note on Data and Citations

All amounts contained in the suite of CRS reports on homeland security appropriations represent budget authority. For precision in percentages and totals, all calculations were performed using unrounded data, which is presented in the report's tables. However, amounts in narrative discussions are generally rounded to the nearest million, unless noted otherwise.

Data used in this report for FY2016 and FY2017 amounts are derived from a single source. Normally, this report would rely on previous fiscal year enacted legislation and reports, as well as House and Senate legislative efforts in response to the Administration's budget request. However, due to the implementation of the Common Appropriations Structure for DHS (see below), this report relies on the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), Division F of which is the Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2017, and the accompanying explanatory statement, which was printed in the May 3, 2017 Congressional Record.2 Information on the second supplemental appropriation for DHS components is drawn from P.L. 115-56.

The "Common Appropriations Structure"3

Section 563 of Division F of P.L. 114-113 (the FY2016 Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act) provided authority for DHS to submit its FY2017 appropriations request under the new common appropriations structure, and implement it in FY2017. Under the act, the new structure was to have four categories of appropriations:

- Operations and Support;

- Procurement, Construction, and Improvement;

- Research and Development; and

- Federal Assistance.4

Most of the FY2017 DHS appropriations request categorized its appropriations in this fashion. The exception was the Coast Guard, which was in the process of migrating its financial information to a new system.

The House Appropriations Committee made its funding recommendation using the CAS (although it chose to implement it slightly differently than the Administration had envisioned in Title I), but the Senate Appropriations Committee did not, instead drafting its annual DHS appropriations bill and report using the same structure as was used in FY2016. No authoritative crosswalk between the House Appropriations Committee proposal in the CAS structure and Senate Appropriations Committee proposal in the legacy structure is publicly available.

The explanatory statement for Division F of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017, included a "detail table," outlining the new structure of DHS appropriations, as well as Programs, Projects, and Activities (PPAs)—the next level of funding detail below the appropriation level. The table showed the FY2016 enacted and FY2017 requested funding for DHS in the new structure as well, enabling the comparisons in this report.5

Summary of DHS Appropriations

Generally, the homeland security appropriations bill includes all annual appropriations provided for DHS, allocating resources to every departmental component. Discretionary appropriations6 provide roughly two-thirds to three-fourths of the annual funding for DHS operations, depending how one accounts for disaster relief spending and funding for overseas contingency operations. The remainder of the budget is a mix of fee revenues, trust funds, and mandatory spending.7

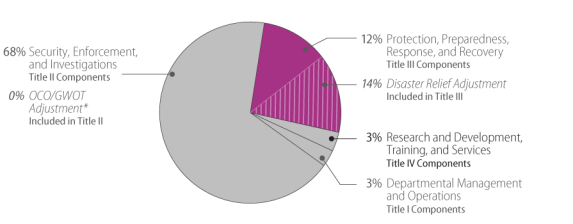

Appropriations measures for DHS typically have been organized into five titles.8 The first four are thematic groupings of components: Departmental Management and Operations; Security, Enforcement, and Investigations; Protection, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery; and Research and Development, Training, and Services. A fifth title contains general provisions, the impact of which may reach across the entire department, impact multiple components, or focus on a single activity. For FY2017, a sixth title responded to the Trump Administration's supplemental appropriations request submitted in March 2017.

The following pie chart presents a visual representation of the share of annual appropriations requested by the Obama Administration for the components funded in each of the first four titles, highlighting the components discussed in this report.9

Protection, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery

As noted above, the Protection, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery title (Title III) of the FY2017 DHS appropriations bill is the second largest of the four titles that carry the bulk of the funding in the bill, and includes most of the grant funding provided by DHS. In FY2016, Title III provided funds for NPPD, OHA, and FEMA. The Obama Administration requested $5.69 billion in FY2017 net discretionary budget authority for NPPD and FEMA (including the effect of transfers), and $6.71 billion in specially designated funding for disaster relief as part of a total budget for these components of $20.00 billion for FY2017.10 The appropriations request for the two components funded in this title was $718 million (11.2%) less than was provided for FY2016 in net discretionary budget authority.

Part of the reason for the reduction in the request for Title III was that, as part of the request, the Obama Administration proposed consolidating OHA (along with several other parts of DHS) into a new Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives Office, funded in Title IV. OHA had been funded at $125 million in Title III in FY2016.

The Senate Appropriations Committee, in S. 3001, would have provided the components included in this title $6.58 billion in net discretionary budget authority. This would have been $898 million (15.8%) more than requested, and $180 million (2.8%) more than was provided in FY2016. S. 3001 did not include the proposed reorganization of OHA, but included the requested disaster relief funding.

The House Appropriations Committee, in H.R. 5634, would have provided the components included in this title $6.44 billion in net discretionary budget authority. This would have been $753 million (13.2%) more than requested, and $34 million (0.5%) more than was provided in FY2016. H.R. 5634 included both the reorganization of OHA and the requested disaster relief funding.

No annual appropriations bill for DHS was enacted prior to the end of FY2016. On September 29, 2016, President Obama signed into law P.L. 114-223, which contained a continuing resolution (CR) funding the government through December 9, 2017, at the same rate of operations as FY2016, minus 0.496%. A second continuing resolution was signed into law on December 10, 2016 (P.L. 114-254), funding the government through April 28, 2017, at the same rate of operations as FY2016, minus 0.1901%. A third (P.L. 115-30) extended the second continuing resolution through May 5, 2017. The continuing resolutions were superseded by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), which includes the Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2017 as Division F. For details on these continuing resolutions and their impact on DHS, see CRS Report R44621, Department of Homeland Security Appropriations: FY2017.

The committee-reported bills expired January 3, 2017, at the end of the 114th Congress.

On March 16, 2017, the Trump Administration submitted an amendment to the FY2017 budget request, which included a request for $3 billion in additional funding for DHS. Congress addressed this request at the same time as it resolved annual appropriations for the federal government, through the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (signed into law as P.L. 115-31 on May 5, 2017). The act included both annual and supplemental appropriations for DHS as Division F.11 It provided $41.3 billion in adjusted net discretionary budget authority in annual appropriations, as well as $6.7 billion in funding for the costs of major disaster under the Stafford Act and $163 million in funding for overseas contingency operations.

The explanatory statement accompanying the act noted that "the language and allocations contained in the House and Senate reports [H.Rept. 114-668 and S.Rept. 114-264] carry the same weight as language included in this explanatory statement unless specifically addressed to the contrary" in the act or the statement.12 Such language is common in appropriations conference reports, but it is especially important in cases like this one where there is no direct procedural link between the House and Senate committee-reported bills from a previous Congress and the consolidated appropriations act.

On September 1, 2017, the Trump Administration requested $7.85 billion in supplemental funding for FY2017, including $7.4 billion for the DRF.13 On September 6, the House passed the relief package requested by the Administration as an amendment to H.R. 601. On September 7, the Senate passed an amended version, which included the House-passed funding as well as an additional $7.4 billion for disaster relief through HUD's Community Development Fund, a short-term increase to the debt limit, and a short-term continuing resolution that would fund government operations into FY2018. The House passed the Senate-amended version of the bill on September 8, 2017, which became P.L. 115-56.

Table 1 shows a brief the funding history for the individual components funded under Protection, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery. It shows the funding level provided for the previous fiscal year, as well as the amounts requested for these accounts for FY2017 by the Obama and Trump Administrations, and the final level enacted in Division F of P.L. 115-31. The table includes information on funding under Title III as well as other provisions in the bill, and supplemental appropriations enacted as a part of P.L. 115-56 for FEMA's DRF.

As some annually appropriated resources are provided for the Federal Emergency Management Agency from outside Title III, a separate line is included showing a total for what is provided within Title III, above the line providing the total annual appropriation. The additional supplemental appropriations for the DRF is only noted in the enacted column. Because it is designated as emergency funding, it is only included in accounting for total budgetary resources, rather than discretionary budget authority (which counts against the discretionary spending limits).

Table 1. Budgetary Resources for Protection, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery Components, FY2016 and FY2017, Common Appropriations Structure

(budget authority in thousands of dollars)

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

|||||

|

Component/Appropriation |

Enacted |

Requesta |

Enacted |

|||

|

National Protection and Programs Directorate |

|

|

|

|||

|

Operations and Support |

1,295,963 |

1,147,502 |

1,372,268 |

|||

|

Cybersecurity |

595,906 |

682,340 |

669,414 |

|||

|

Cyber Readiness and Response |

152,433 |

208,851 |

196,904 |

|||

|

Cyber Infrastructure Resilience |

42,190 |

38,251 |

44,053 |

|||

|

Federal Cybersecurity |

401,283 |

435,238 |

428,457 |

|||

|

Infrastructure Protection |

192,455 |

177,866 |

186,292 |

|||

|

Infrastructure Capacity Building |

115,846 |

100,990 |

116,735 |

|||

|

Infrastructure Security Compliance |

76,609 |

76,876 |

69,557 |

|||

|

Emergency Communications |

101,303 |

100,632 |

102,041 |

|||

|

Emergency Communications Preparedness |

44,306 |

43,260 |

44,097 |

|||

|

Priority Telecommunications Service |

56,997 |

57,372 |

57,944 |

|||

|

Integrated Operations |

114,319 |

111,637 |

109,684 |

|||

|

Cyber and Infrastructure Analysis |

40,255 |

37,436 |

41,880 |

|||

|

Critical Infrastructure Situational Awareness |

13,702 |

16,344 |

16,176 |

|||

|

Stakeholder Engagement and Requirements |

46,603 |

43,150 |

41,959 |

|||

|

Strategy, Policy and Plans |

13,759 |

14,707 |

9,669 |

|||

|

Office of Biometric Identity Management |

215,253 |

0 |

235,429 |

|||

|

Identity and Screening Program Operations |

69,828 |

0 |

71,954 |

|||

|

IDENT/Homeland Advanced Recognition Technology |

145,425 |

0 |

163,475 |

|||

|

Mission Support |

76,727 |

75,027 |

69,408 |

|||

|

Procurement, Construction, and Improvements |

333,523 |

436,797 |

440,035 |

|||

|

Cybersecurity |

189,173 |

348,742 |

299,180 |

|||

|

Continuous Diagnostics and Mitigation |

97,435 |

266,971 |

217,409 |

|||

|

National Cybersecurity Protection System |

91,738 |

81,771 |

81,771 |

|||

|

Emergency Communications |

78,550 |

88,055 |

88,055 |

|||

|

Next Generation Networks Priority Services |

78,550 |

88,055 |

88,055 |

|||

|

Biometric Identity Management |

65,800 |

0 |

52,800 |

|||

|

IDENT/Homeland Advanced Recognition Technology |

65,800 |

0 |

52,800 |

|||

|

Research and Development |

6,119 |

4,469 |

6,469 |

|||

|

Cybersecurity |

2,030 |

2,030 |

2,030 |

|||

|

Infrastructure Protection |

4,089 |

2,439 |

4,439 |

|||

|

Federal Protective Service |

1,443,449 |

1,451,078 |

1,451,078 |

|||

|

Offsetting Collections |

1,443,449 |

1,451,078 |

1,451,078 |

|||

|

Federal Protective Service (net) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|||

|

Total Annual Discretionary Appropriations |

1,635,605 |

1,588,768 |

1,818,772 |

|||

|

Fees, Mandatory Spending, and Trust Funds |

1,443,449 |

1,451,078 |

1,451,078 |

|||

|

Total Budgetary Resources |

3,079,054 |

3,039,846 |

3,269,850 |

|||

|

Office of Health Affairsb |

||||||

|

Operations and Support |

125,369 |

0 |

123,548 |

|||

|

Chemical and Biological Readiness |

82,902 |

- |

82,689 |

|||

|

Health and Medical Readiness |

4,495 |

- |

4,352 |

|||

|

Integrated Operations |

10,962 |

- |

11,809 |

|||

|

Mission Support |

27,010 |

- |

24,698 |

|||

|

Total Annual Discretionary Appropriations |

125,369 |

0 |

123,548 |

|||

|

Total Budgetary Resources |

125,369 |

0 |

123,548 |

|||

|

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

||||||

|

Operations and Support |

918,954 |

1,038,480 |

1,048,551 |

|||

|

Regional Operations |

151,460 |

157,134 |

157,134 |

|||

|

Mitigation |

27,957 |

24,887 |

28,213 |

|||

|

Preparedness and Protection |

149,281 |

146,356 |

146,356 |

|||

|

Response and Recovery |

222,387 |

237,187 |

243,932 |

|||

|

Response |

172,624 |

178,500 |

187,806 |

|||

|

(Urban Search and Rescue) |

35,180 |

27,153 |

38,280 |

|||

|

Recovery |

49,763 |

58,687 |

56,126 |

|||

|

Mission Support |

367,869 |

472,916 |

472,916 |

|||

|

Procurement, Construction, and Improvements |

43,300 |

35,273 |

35,273 |

|||

|

Operational Communications / Information Technology |

2,800 |

2,800 |

2,800 |

|||

|

Construction and Facility Improvements |

29,000 |

21,050 |

21,050 |

|||

|

Mission Support, Assets, and Infrastructure |

11,500 |

11,423 |

11,423 |

|||

|

Federal Assistance |

2,992,500 |

2,407,321 |

2,983,458 |

|||

|

Grants |

2,717,000 |

2,209,016 |

2,709,531 |

|||

|

State Homeland Security Grant Program |

467,000 |

200,000 |

467,000 |

|||

|

(Operation Stonegarden) |

55,000 |

0 |

55,000 |

|||

|

Urban Area Security Initiative |

600,000 |

330,000 |

605,000 |

|||

|

(Nonprofit Security) |

20,000 |

0 |

25,000 |

|||

|

Public Transportation Security Assistance |

100,000 |

85,000 |

100,000 |

|||

|

(Amtrak Security) |

10,000 |

10,000 |

10,000 |

|||

|

(Over-the-Road Bus Security) |

0 |

0 |

2,000 |

|||

|

Port Security Grants |

100,000 |

93,000 |

100,000 |

|||

|

Emergent Threats |

0 |

49,000 |

0 |

|||

|

Regional Competitive Grant Program |

0 |

100,000 |

0 |

|||

|

Assistance to Firefighter Grants |

345,000 |

335,000 |

345,000 |

|||

|

Staffing for Adequate Fire and Emergency Response (SAFER) Grants |

345,000 |

335,000 |

345,000 |

|||

|

Emergency Management Performance Grants |

350,000 |

350,000 |

350,000 |

|||

|

National Predisaster Mitigation Fund |

100,000 |

54,485 |

100,000 |

|||

|

Flood Hazard Mapping and Risk Analysis Program |

190,000 |

177,531 |

177,531 |

|||

|

Emergency Food and Shelter |

120,000 |

100,000 |

120,000 |

|||

|

Education, Training, and Exercises |

275,500 |

198,305 |

273,927 |

|||

|

Center for Domestic Preparedness |

64,991 |

63,939 |

63,939 |

|||

|

Center for Homeland Defense and Security |

18,000 |

18,000 |

18,000 |

|||

|

Emergency Management Institute |

20,569 |

19,643 |

20,569 |

|||

|

U.S. Fire Administration |

42,500 |

40,812 |

42,500 |

|||

|

National Domestic Preparedness Consortium |

98,000 |

36,000 |

101,000 |

|||

|

Continuing Training Grants |

11,521 |

0 |

8,000 |

|||

|

National Exercise Program |

19,919 |

19,911 |

19,919 |

|||

|

Disaster Relief Fundc |

||||||

|

Base |

661,740 |

639,515 |

615,515 |

|||

|

Major Disasters |

6,712,953 |

6,709,000 |

6,713,000 |

|||

|

Transfer to DHS Office of Inspector General |

(24,000) |

(24,000) |

0 |

|||

|

Subtotal: Net disaster relief funding |

7,350,693 |

7,324,515 |

7,328,515 |

|||

|

National Flood Insurance Fund |

181,198 |

181,799 |

181,799 |

|||

|

Offsetting Fee Collections |

181,198 |

181,799 |

181,799 |

|||

|

Radiological Emergency Preparedness Program (Administrative Provisions) |

(305) |

(265) |

(265) |

|||

|

Title III Discretionary Appropriations |

4,797,387 |

4,302,123 |

4,864,331 |

|||

|

Emergent Threats (Title V) |

50,000 |

0 |

0 |

|||

|

Presidential Residence Protection (Title V) |

0 |

0 |

41,000 |

|||

|

Total Annual Net Discretionary Appropriationsd |

4,847,387 |

4,302,123 |

4,905,331 |

|||

|

Supplemental Appropriations |

||||||

|

Disaster Relief Fund (Emergency; P.L. 115-56) |

7,400,000 |

7,400,000 |

||||

|

Fees, Mandatory Spending, and Trust Fundse |

5,038,444 |

5,972,680 |

5,972,680 |

|||

|

Total Budgetary Resources |

16,775,982 |

16,778,004 |

24,809,212 |

|||

|

Net Discretionary Budget Authority: Title IIId |

6,377,163 |

5,709,092 |

6,624,852 |

|||

|

Net Discretionary Budget Authority: General Provisions for Protection, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery Components |

50,000 |

0 |

41,000 |

|||

|

Net Discretionary Budget Authority: Total for Protection, Preparedness, Response and Recovery Components |

6,427,163 |

5,709,092 |

6,665,852 |

|||

|

Projected Total Gross Budgetary Resources for Protection, Preparedness, Response and Recovery Components |

19,960,405 |

19,817,850 |

28,202,610 |

|||

Source: CRS analysis of DHS FY2017 Budget-in-Brief; Division F of P.L. 115-31 and its explanatory statement as printed in the Congressional Record of May 3, 2017, pp. H3807-H3873; and P.L. 115-56.

Notes: Fee revenues included in the "Fees, Mandatory Spending, and Trust Funds" lines are projections, and do not include budget authority provided through general provisions.

a. This column reflects the FY2017 budget request by the Obama Administration for annual appropriations, and the Trump Administration's requests for FY2017 supplemental appropriations from its letters of March 16, 2017, and September 1, 2017.

b. As part of the FY2017 budget request, the Administration proposed moving the Office of Health Affairs into a new Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives Office, under Title IV. This reorganization was not approved.

c. This line is a subtotal of the "Base" line and the "Major Disasters" line (also known as the disaster relief adjustment)—it represents the total resources provided to the DRF. Amounts covered by the disaster relief adjustment are not included in appropriations totals, but are included in budget authority totals, per appropriations committee practice.

d. For consistency across tables, this line does not include the $24 million transfer from the DRF—its impact is reflected in the budgetary resource totals below.

National Protection and Programs Directorate (NPPD)14

The National Protection and Programs Directorate (NPPD) is the component within the Department of Homeland Security responsible for leading national efforts on information sharing, risk mitigation, and protection efforts for the resilience of national infrastructure, and for cybersecurity.

NPPD is currently organized into five offices: the Office of Biometric Identity Management (OBIM), the Office of Cybersecurity and Communications (CS&C), the Office of Cyber and Infrastructure Analysis (OCIA), the Office of Infrastructure Protection (IP), and the Federal Protective Service (FPS). The majority of the net discretionary budget for NPPD focuses on cybersecurity and critical infrastructure protection, which are reflected in CS&C and IP.15 Other responsibilities for NPPD include providing biometric identity services to the department, providing all-hazard consequence and interdependency analysis on critical infrastructure, and securing federal facilities.

The Obama Administration's FY2017 budget proposed moving two elements of NPPD to other parts of DHS: OBIM was to be transferred to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (funded in Title II), and the Office of Bombing Prevention was to be transferred from IP to the new Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives (CBRNE) Office funded in Title IV. However, Congress did not authorize the transfers, so funding for those offices remains in the NPPD appropriations in Title III.

Summary of Appropriations

For FY2016, the Obama Administration requested $3.04 billion in discretionary budget authority for NPPD. $1.45 billion of this was for FPS, whose budget is offset by fees. The budget request for the rest of NPPD was $1.59 billion in net discretionary budget authority, $47 million (2.9%) less than was provided in FY2016. Note that these figures do not include the $306 million request for OBIM, which the Administration proposed transferring to CBP in the request, nor the $14 million request for the Office of Bombing Prevention (OBP), which the Administration proposed transferring to the new Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives (CBRNE) office. The total FY2017 request for all of the FY2016 elements of NPPD including OBIM and OBP was $1.91 billion in net discretionary budget authority—$272 million (16.6%) more than was provided in FY2016.

Senate Appropriations Committee-reported S. 3001 included $1.82 billion in net discretionary budget authority for NPPD, not including FPS. This was $230 million (14.5%) more than was requested by the Administration, although the Administration's request for NPPD did not include the $320 million for OBIM and OBP, while S. 3001 continued to include it in NPPD. The net funding level for NPPD in S. 3001 was $183 million (11.2%) more than was provided in FY2016. FPS was funded at the requested level in the bill and fully offset.

House Appropriations Committee-reported H.R. 5634 included $1.76 billion in net discretionary budget authority for NPPD, not including FPS. This is $167 million (10.5%) more than was requested by the Administration, although the House bill continued to include the $306 million for OBIM that the Administration had proposed moving to a new DHS component.16 The net funding level for NPPD in H.R. 5634 was $120 million (7.4%) more than was provided in FY2016. The House committee-reported funding level is $62 million (3.4%) less than was proposed in the Senate committee-reported bill. FPS would be funded at the requested level in H.R. 5634 and fully offset.

The enacted annual DHS appropriations bill (P.L. 115-31, Division F) included $1.82 billion in net discretionary budget authority for NPPD, not including FPS. This is $230 million (14.5%) more than what was requested by the Administration. FY2017 funding is $183 million (11.2%) more than NPPD's FY2016 appropriation. As noted above, P.L. 115-31 does not provide for the reorganization of NPPD, so funding for OBIM and OBP remains in NPPD.

Issues in NPPD's Appropriations

NPPD Reorganization

DHS requested that Congress authorize NPPD to reorganize into the Cyber and Infrastructure Protection Agency (CIPA) to focus its efforts and achieve greater operational efficiencies.17 DHS proposed elevating the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC) to a direct reporting element within the agency with responsibilities for all of NPPD's cybersecurity activities, renaming the "Office of Infrastructure Protection" to be "Infrastructure Security," keeping FPS as is. In all, the new structure would contain three primary elements with seven support elements.18

Both the House and the Senate committee-reported appropriation bills would have funded NPPD within its current structure without authorizing reorganization, and as noted above, P.L. 115-31 did not authorize reorganization.

The 114th Congress considered an alternative proposal for NPPD reorganization in H.R. 5390, but it was never voted on in the House. The "Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Protection Agency Act of 2016" would have altered the composition of the directorate by creating four subelements: the Cybersecurity Division; the Infrastructure Protection Division; the Emergency Communications Division; and FPS. General responsibilities for the reorganized "agency" would have been similar to the currently structured directorate.

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency Act of 2017 (H.R. 3359) would establish the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) as a new agency in DHS to carry out the cybersecurity and infrastructure security responsibilities NPPD. Under the bill, the Office of Biometric Identity Management would be transferred to the Management Directorate and the Federal Protective Service would be transferred out of NPPD to another component of the Secretary's choice.

Office of Biometric Identity Management (OBIM)

OBIM is responsible for providing biometric identification services across DHS, and to other federal, state, local, and international government partners. OBIM does this by providing the government and international partners technology they may use to collect and store biometric data to identify individuals, and by ensuring the integrity of that data.

Under the Obama Administration's proposed NPPD reorganization OBIM would be transferred to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. However, neither the House nor the Senate appropriation bills authorize the reorganization, and both committee reports explicitly denied funding for such a move until the reorganization is authorized.

Both committees expressed concern over the governance of the office. The House report withheld $122 million from obligation, calling for stakeholder input to be addressed. The Senate report explicitly stated that no less than $52 million could be used for the next developmental stage of OBIM's new technology platform, and expressed similar concerns about stakeholder engagement. The Senate report called for periodic briefings on the subject to the committee.

P.L. 115-31 provided $235 million in appropriations for OBIM, which was $11.6 million below the requested level because of delays in the Homeland Advanced Recognition Technology (HART) program and savings from contracts. Appropriators withheld $20 million in funding until the department briefs the appropriations committees on the implementation of facial recognition and multimodal biometrics, establishing a new governance structure, and demonstrating the ability to fuse intelligence with biometric data.19

Staffing

Both committees noted that the department has been unable to recruit and retain staff at its authorized level. As such, both committees recommended lower than requested position authorizations and would have reduced funding, accordingly, to allow the department to align its hiring and attrition.

The House committee report noted that "NPPD continues to suffer from an inability to fill key vacancies ... especially in hiring and retaining personnel with the requisite cyber skills." The House Appropriations Committee recommended providing the requested funding for special cyber pay and bonuses, but recommended overall funding that was almost $6 million and 345 FTE below the request because of the "expected under-execution of funding for new personnel."20 The Senate committee report also cited "unrealistically optimistic staffing levels" in their explanation for recommending funding less than the requested 2,289 FTEs for non-FPS elements of NPPD.21

The explanatory statement accompanying the appropriations act notes that funding was reduced for NPPD Operations and Support by almost $38 million and 386 FTEs because NPPD has been underexecuting against previously authorized personnel levels. However, the statement notes that the appropriations act keeps funding in place, with pay flexibilities to help recruit and retain a cybersecurity workforce.22

Cybersecurity Programs

Both committees recommended increases for cybersecurity-related activities from the FY2016 level, but at a level that is lower than the Obama Administration's FY2017 request. Two major programs—in both budget and scope—related to cybersecurity for NPPD are the National Cybersecurity Protection System (NCPS) and the Continuous Diagnostics and Mitigations program (CDM).

NCPS is a system intended to improve the security of federal agencies at the point where they connect to the public Internet. It includes three tools (network packet traffic capture, intrusion detection, and intrusion prevention services) more commonly known as EINSTEIN, and a separate computer network to analyze signatures and other identifiers for EINSTEIN. The Senate Appropriations Committee did not explicitly detail a funding level for NCPS, which it included in the Network Security Deployment subappropriation. The House Appropriations Committee report recommended funding NCPS at the requested level of $471 million.

CDM is a program under which NPPD procures sensors for other federal agencies to deploy on their networks. These sensors scan the agency's network to understand the state of the information technology on their network. The results of those scans are reported to an agency dashboard, which, combined with data from the NCCIC, helps agencies prioritize which issues to address. The Senate Appropriations Committee recommended $247 million for CDM, $18 million below the request. Although it would fully fund the requested operational costs for CDM, the House Appropriations Committee recommended reducing procurement funding for CDM by $102 million relative to the request.23

The National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC) is NPPD's most visible cybersecurity program. The NCCIC is a continuously operating watch center that collects, analyzes, and disseminates cybersecurity risk information to critical infrastructure and government partners. While the NCCIC is funded and staffed through multiple accounts, it now submits a consolidated budget request to provide greater transparency into NCCIC activities. The Senate Appropriations Committee recommended an increase for overall NCCIC activities which is reflected when examining funding for all the programs and activities associated with NCCIC funding. However, the increase is less than was requested, which the Senate report attributed to slower than anticipated hiring.24 The House report recommended a reduction in NCCIC funding of $26 million, citing budget constraints.25

P.L. 115-31 provides a total of $970 million for cybersecurity divided among Operations and Support ($669 million), Procurement ($299 million), and Research and Development ($2 million) appropriations. FY2017 funding levels are higher than the FY2016 amounts for cybersecurity, but less than the department-requested amount. Cybersecurity Operations and Support funding is 12.3% greater than in FY2016, but 1.9% lower than requested. Procurement funding is 58.2% greater than in FY2016, largely due to a 123.1% increase in funding for the purchase of CDM tools and sensors in FY2017. Research and development funding is flat for NPPD across the time reviewed in this report. The explanatory statement accompanying the annual appropriations act notes continued efforts by NPPD to secure federal networks, and provides guidance that NPPD-provided tools should "supplement but not supplant" agency IT security appropriations. NPPD is directed to develop, in conjunction with OMB and partner agencies, a strategic plan on securing federal network which shall include a plan for agencies to assume the costs of security from NPPD.26

Office of Health Affairs (OHA)27

The Office of Health Affairs (OHA) coordinates or consults on DHS programs that have a public health or medical component.28 These include FEMA operations, homeland security grant programs, and medical care provided at Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention facilities. OHA also has operational responsibility for several programs, including the BioWatch program, the National Biosurveillance Integration Center (NBIC), the department's occupational health and safety programs, and the department's implementation of Homeland Security Presidential Directive-9 (HSPD-9), "Defense of United States Agriculture and Food."

In its request for FY2017, the Obama Administration proposed reorganizing OHA into a new Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosives (CBRNE) Office, which would also incorporate the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (DNDO), as well as a small part of the National Protection and Programs Directorate, and part of the Office of Policy from Title I. More discussion of the reorganization proposal can be found in CRS Report R44658, DHS Appropriations FY2017: Research and Development, Training, and Services, coordinated by [author name scrubbed].

Summary of Appropriations

As noted above, for FY2017, the Obama Administration requested reorganizing OHA into a new CBRNE Office. While funding for some OHA programs could be identified in the CBRNE Office request, no explicit OHA request was made.29

S. 3001, as reported by the Senate Appropriations Committee, did not fund the proposed CBRNE Office. Rather, it recommended funding levels for components as organized in the current DHS structure. S. 3001 would have provided $108 million in discretionary budget authority for OHA. This is $17 million (13.6%) less than was provided in FY2016 and, according to the Senate Committee Report, it is $12 million (10.0%) less than less than the Administration's request for comparable activities.30

House Appropriations Committee-reported H.R. 5634 did not specify an appropriations amount for OHA as it conformed to the requested reorganization into the CBRNE Office.

Division F of P.L. 115-31 did not reorganize OHA. It provided $124 million for OHA, about $2 million (1.5%) less than was provided in FY2016. The act withholds $2 million of the appropriation until OHA provides the appropriations committees a plan to advance early detection of bioterrorism events.

Issues in OHA Appropriations

BioWatch

The BioWatch program deploys sensors in more than 30 U.S. cities to detect the possible aerosol release of a bioterrorism pathogen, to aid in the distribution of medications before exposed individuals became ill. The operation of BioWatch accounts for most of OHA's budget. The program had sought for several years to deploy more sophisticated autonomous sensors that could detect airborne pathogens in a few hours, rather than the day or more that is currently required. However, DHS announced the termination of further procurement activities in April 2014 after several years of unsuccessful efforts to procure a replacement for the existing system.31

The Obama Administration requested $82 million for BioWatch, approximately the same amount as was provided in FY2016. The Senate committee recommended $12 million (14.6%) less than the requested amount for BioWatch for FY2017. It recommended redirecting this $12 million to the S&T Directorate to "speed the development of a new bio-detection technology" rather than funding the "recapitalization, training, and other support activities of the current system."32

The House committee recommended providing the requested amounts for BioWatch for FY2017, including $1 million to support the replacement and recapitalization of current generation BioWatch equipment. However, the committee expressed concern about the effectiveness of the current system and DHS progress toward improving this system. The committee report directed DHS to "more clearly articulate future technology requirements for the program to the private sector and innovators who are being called upon to help address those needs."33

Division F of P.L. 115-31 provides $83 million for BioWatch, approximately the same amount as was provided in FY2016. Section 302 of the act withholds $2 million of the separate $25 million appropriation for OHA Mission Support until OHA, in conjunction with the Science and Technology Directorate, provides the appropriations committees a "comprehensive strategy and project plan to advance the Nation's early detection capabilities related to a bioterrorism event."34

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

The primary mission of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is to reduce the loss of life and property, and protect the nation from all hazards. It is responsible for leading and supporting the nation's preparedness for manmade and natural disasters through a risk-based and comprehensive emergency management system of preparedness, protection, response, recovery, and mitigation.35

FEMA executes its mission through a number of activities. It provides incident response, recovery, and mitigation assistance to state and local governments, primarily appropriated through the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) and the Pre-Disaster Mitigation Fund. It also supports disaster preparedness through a series of homeland security and emergency management grant programs.

Summary of Appropriations

For FY2017, the Obama Administration requested $4.12 billion in net discretionary budget authority for FEMA. This would have been $546 million (11.7%) less than was provided in FY2016. FEMA's budget includes two large elements that do not count toward the total net discretionary budget authority: funding for major disasters declared by the President under the authority of the Stafford Act, which is accommodated under an adjustment to the discretionary spending limits; and the National Flood Insurance Fund, which is considered mandatory spending. The Administration requested $6.7 billion for the cost of major disasters as a part of FEMA's overall budget.

S. 3001 included $4.68 billion in net discretionary budget authority for FEMA. This would have been $560 million (13.6%) more than was requested by the Administration, and $14 million (0.3%) more than was provided in FY2016. The Senate bill also included the requested $6.7 billion for the cost of major disasters.

H.R. 5634 included $4.71 billion in net discretionary budget authority for FEMA. This would have been $585 million (14.2%) more than was requested by the Administration, and $39 million (0.8%) more than was provided in FY2016. The House committee-reported funding level was $26 million (0.5%) more than was proposed in the Senate committee-reported bill. The House bill also included the requested $6.7 billion for the cost of major disasters.

Division F of P.L. 115-31 included $4.72 billion in net discretionary budget authority for FEMA. This is $602 million (14.0%) above the level requested by the Obama Administration, and $58 million (1.2%) above the enacted level for FY2016. The act also included $6.7 billion for the cost of major disasters.

On September 1, 2017, the Trump Administration requested $7.85 billion in supplemental funding for FY2017, including $7.4 billion for the FEMA's DRF.36 On September 6, the House passed the relief package requested by the Administration as an amendment to H.R. 601. On September 7, the Senate passed an amended version, which included the House-passed funding as well as an additional $7.4 billion for disaster relief through HUD's Community Development Fund, a short-term increase to the debt limit, and a short-term continuing resolution that would fund government operations into FY2018. The House passed the Senate-amended version of the bill on September 8, 2017, and it became P.L. 115-56.

Issues in FEMA Appropriations

Disaster Relief Fund (DRF)37

The Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) is the main account used to fund a wide variety of programs, grants, and other forms of emergency and disaster assistance to states, local governments, certain nonprofit entities, and families and individuals affected by disasters. The DRF expends funds in response to current incidents, as well as to meet recovery needs from previous incidents.38 As a result, the DRF is a no-year account—unused budget authority from the previous fiscal year is carried over to the next fiscal year.

Funding currently provided to the DRF can be broken out into two categories. The first is funding for activities not directly tied to major disasters under the Stafford Act (including activities such as assistance provided to states for emergencies and fires). This category is sometimes referred to as the DRF's "base" funding. The second (and significantly larger) category is for disaster relief costs for major disasters under the Stafford Act. This structure reflects the impact of the Budget Control Act (P.L. 112-25, hereinafter referred to as the BCA), which allows these costs incurred by major disasters to be paid through an "allowable adjustment" to the discretionary spending caps, rather than having them count against the discretionary spending allocation for the bill.

|

The Disaster Relief Fund, Disaster Relief, and the Budget Control Act (BCA) It is important to note that "disaster relief" funding under the BCA and the Disaster Relief Fund are not the same. The BCA defines funding for "disaster relief" as funding for activities carried out pursuant to a major disaster declaration under the Stafford Act. This funding comes not only from FEMA, but from accounts across the federal government. While a portion of funding for the DRF is eligible for the allowable adjustment under the BCA, it is not wholly "disaster relief" by the BCA definition. For more detail on the allowable adjustment, see the appendix of CRS Report R44621, Department of Homeland Security Appropriations: FY2017, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]; CRS Report R42352, An Examination of Federal Disaster Relief Under the Budget Control Act, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed]; or CRS Report R44415, Five Years of the Budget Control Act's Disaster Relief Adjustment, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]. |

For FY2017, the Obama Administration requested $7,348 million in discretionary budget authority for the DRF. The requested amount for the base was $639 million, while $6,709 million was requested for the costs of major disasters. In addition, the Administration requested a $24 million transfer from the DRF to the DHS Office of Inspector General (DHS OIG) for oversight of disaster relief activities. The requested amount is $26 million less than was provided in FY2016.

The House- and Senate-reported bills included the amount requested by the Administration for the DRF ($639 million for the base, and $6,709 million for disaster relief) including the $24 million transfer to the DHS OIG. Division F of P.L. 115-31 included the requested DRF funding, but did not transfer any resources to the DHS OIG.

On September 1, 2017, the Trump Administration requested $7.85 billion in supplemental funding for FY2017, including $7.4 billion for the DRF.39 This amount was requested, and ultimately provided in P.L. 115-56, with an emergency funding designation, since the allowable adjustment for disaster relief had been exhausted for FY2017.

Balances in the DRF

Prior to the enactment of the BCA, funds in the DRF often ran too low to meet federal disaster assistance needs before being replenished by annual appropriations. When the account neared depletion, Congress usually provided additional funding through supplemental appropriations.40 In some fiscal years, Congress passed two or three supplemental appropriations to fund the DRF. Since the passage of the BCA, an increase in the annual funding level for the DRF may have decreased the need for supplemental funding.41 As demonstrated in Table 2, annual appropriations for the DRF have been significantly larger since FY2011, the last year appropriations were provided for the DRF without benefit of the mechanisms of the BCA.

Table 2. Annual Appropriations for the Disaster Relief Fund in Annual Appropriations Acts, FY2007-FY2017

(in millions of nominal dollars)

|

Fiscal Year |

Annual Appropriation |

|

2007 |

$1,487 |

|

2008 |

$1,324 |

|

2009 |

$1,278 |

|

2010 |

$1,600 |

|

2011 |

$2,645 |

|

2012 |

$7,100 |

|

2013 |

$7,007 |

|

2014 |

$6,220 |

|

2015 |

$7,033 |

|

2016 |

$7,374 |

|

2017 |

$7,329 |

Source: CRS Report R43537, FEMA's Disaster Relief Fund: Overview and Selected Issues, by [author name scrubbed].

Notes: Table does not include transfers, rescissions, or supplemental appropriations for the DRF, with the exception of $6.4 billion in supplemental appropriations in FY2012, when supplemental appropriations for the DRF were provided in a process that paralleled the enactment on omnibus appropriations. Bolded text refers to appropriations after the enactment of the BCA.

Since the FY2012 appropriations cycle, only two supplemental appropriations bills have been enacted with funding for the Disaster Relief Fund. The first, P.L. 113-2, provided relief in the wake of Hurricane Sandy. When Hurricane Sandy made landfall, the existing balance of more than $7.5 billion in the DRF helped fund the immediate assistance needs in the wake of the storm without an immediate supplemental appropriation. Six weeks later, the Obama Administration requested supplemental appropriations for a range of response, recovery, and mitigation activities.

The second, P.L. 115-56, provided supplemental appropriations at the end of FY2017, and was noted above. Before Hurricane Harvey made landfall in Texas on August 25, 2017, the DRF had roughly $3.5 billion in total unobligated resources available. In order to conserve resources needed for time-sensitive disaster assistance, on August 28, FEMA implemented "immediate needs funding restrictions," which delay funding for all longer-term projects until additional resources are available. Even with this restriction, according to FEMA, as of the morning of September 1, the DRF had less than $2 billion in total unobligated resources.42 That same day, the Trump Administration requested supplemental appropriations for response and immediate recovery needs.43

Arguably, the larger balance provided the Obama Administration and Congress with more time to assess the need for federal assistance and target it rather than requiring immediate legislative action to fund the DRF, as was the case at the end of FY2017.

Some may argue a relatively healthy balance is beneficial compared to years prior to the BCA when a large disaster or active hurricane season (or both) could have quickly depleted the remaining unobligated amount, necessitating a supplemental appropriation for additional funds for disaster relief. Others may question the budgetary practices used to appropriate funds for the DRF and argue that large carryovers from previous fiscal years indicate that the account is being funded at too high a level. They may also be concerned that any excess funds not used for an emergency or disaster could be transferred or rescinded for purposes other than disaster assistance.

Mitigation44

The Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) Grant Program, authorized under Section 203 of the Stafford Act,45 provides funding for mitigation actions at the state and local level without the need for a preceding disaster event. The program is cost-shared on a 75% federal and 25% state and local basis. PDM funds can be used for both mitigation projects and planning.

The level of funding requested over the years for PDM has varied in a broad range. The program had been zeroed out by the Obama Administration in their base budget request in FY2013 and FY2014. In FY2016, the Obama Administration-requested level for the PDM program increased substantially to the $200 million level—$100 million was ultimately appropriated.

The FY2017 request from the Obama Administration continued the trend of fluctuation, with the requested funding level for PDM dropping to just over $54 million.46 The Senate-reported bill included $100 million for PDM, while the House-reported bill included the requested level. The House Appropriations Committee report observed that "FEMA projects to have more than $50 million in carryover funding available in FY2017 from prior year appropriations."47 In P.L. 115-31, Congress provided $100 million for PDM, equivalent to the funding provided in FY2016.

Both of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees' reports contained language related to FEMA's mitigation efforts. In particular, the House committee questioned whether states are giving "appropriate consideration to disaster mitigation projects proposed by counties when developing state mitigation plans that inform the allocation of post-disaster mitigation grants, or when submitting applications for pre-disaster mitigation grants to FEMA."48 The postdisaster grants referenced are the funds made available under the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP), Section 404 of the Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act,49 and the PDM Grant Program.50 To address these concerns FEMA was directed to brief the committee on the guidance it gives to states on the matter, within 90 days of passage. According to the committee report, the briefing should emphasize whether FEMA's current guidance encourages appropriate consideration of those local mitigation projects that benefit large population centers.

The House committee report also addressed the "safe room" concept—specially designed protective structures developed in tornado-prone areas, often using both FEMA HMGP and PDM funds. The House Appropriations Committee noted that the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) model codes have helped to improve "safe rooms" for new school buildings and other assembly areas. However, the committee expressed a concern that even these improvements may not be sufficient given the severity of recent storms. The House Appropriations Committee recommended that "FEMA consider the adoption of uniform national guidelines for safe room design and construction, as well as a requirement that safe rooms be incorporated into the design and construction of federally-funded structures located in areas prone to severe weather hazards."51

The Senate Appropriations Committee report also addressed multiple areas of mitigation policy. The report called for FEMA and the Mitigation Federal Leadership Group (MitFLG) to create

a strategy which helps guide decision-makers across the Federal Government … on how to best prioritize Federal resources aimed at enhancing disaster resilience; an actionable and measurable investment strategy supported by predictive financial and risk data; and how Federal programs can be better integrated and coordinated with State and local mitigation efforts.52

This direction from the Senate committee responded to concerns raised by GAO following an investigation into federal efforts to strengthen disaster resilience during Hurricane Sandy recovery.53

The Senate report also noted that while planning still is an eligible mitigation expenditure under PDM, the committee wanted to see more emphasis on actual projects. Toward that end the Senate Appropriations Committee report directed FEMA to develop an annual report that will identify "the end users of these grants, how funding is utilized, and the cost-benefit analysis completed demonstrating the larger impact of these grants."54 The Senate report further cited that mitigation funding can be maximized by private-public partnerships, especially in "very high risk areas like the Cascadia subduction zone." FEMA was directed to brief the appropriations committee "prior to making PDM grant applications available on how public-private partnerships will be specifically evaluated when considering projects."55

P.L. 115-31 and the explanatory statement that accompanied it did not address these matters. As the House and Senate committee-reported directions are not in conflict, both committees' directions stand.

DHS State and Local Preparedness Grants

State and local governments have primary responsibility for most domestic public safety functions, which includes state and local homeland security operations. Homeland security preparedness has become a significant issue for states and localities due to the increase in international and domestic terrorist threats. When facing difficult fiscal conditions, state and local governments may reduce resources allocated for homeland security preparedness, due to increasing pressure to address tight budgetary constraints and competing priorities. Since state and local governments fund the largest percentage of homeland security expenditures, this may have a significant impact on the national preparedness level.

Prior to 9/11, three federal grant programs were available to state and local governments to address homeland security: the State Domestic Preparedness Program administered by the Department of Justice; the Emergency Management Performance Grant (EMPG) administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA); and the Metropolitan Medical Response System (MMRS) administered by the Department of Health and Human Services. Since then, several additional homeland security grant programs were added to amplify state and local preparedness, including the State Homeland Security Grant Program (SHSGP), Citizen Corps Program (CCP), Urban Area Security Initiative (UASI), Driver's License Security Grants Program (REAL ID), Operation Stonegarden grant program (Stonegarden), Regional Catastrophic Preparedness Grant Program (RCPG), Public Transportation Security Assistance and Rail Security Assistance grant program (Transit Security Grants), Port Security Grants (Port Security), Over-the-Road Bus Security Assistance (Over-the-Road), Buffer Zone Protection Program (BZPP), Interoperable Emergency Communications Grant Program (IECGP), and Emergency Operations Center Grant Program (EOC). While some of these programs are no longer funded, some still receive explicit mention in appropriations reports, while others have become allowable uses for funding provided under a larger umbrella grant program, without explicit congressional action.

Summary of Preparedness Grant Funding

With the implementation of the new Common Appropriations Structure (CAS), these grants are funded in the Federal Assistance appropriations category. As has been mentioned previously, a modified CAS was adopted in P.L. 115-31, after the House Appropriations Committee adopted the CAS, but the Senate Appropriations Committee did not. Despite these structural differences in the legislation, it is still possible to compare the funding proposed by the Obama Administration and recommended by the House and Senate appropriations committees with the funding provided in the enacted FY2017 DHS appropriations act.

The Obama Administration requested $857 million for state and local grant programs for FY2017. This is $460 million (32.3%) less than was appropriated in FY2016 ($1.32 billion: $1.27 billion in Title III, and $50 million for grants to address emergent threats in a general provision). The Obama Administration proposed a new regional competitive grant program alongside the established grant programs. However, for the first time since FY2012, the Obama Administration did not propose creating a single block grant for preparedness grants.

S. 3001 included $1.32 billion for state and local preparedness grant programs for FY2017. H.R. 5634 included $1 million less than S. 3001. P.L. 115-31 appropriated $1.31 billion for preparedness grant programs, including a $41 million in a new general provision to reimburse extraordinary law enforcement personnel costs for protection of Presidential residences.56 It did not include the regional competitive grant program.

Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of preparedness grant funding by program for FY2016 and FY2017. Lines in italics represent carveouts from the plain text amounts for the umbrella grant programs immediately above them.

Table 3. FEMA Preparedness Grants, FY2016-FY2017

(Thousands of dollars of discretionary budget authority)

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

|||||||||

|

Enacted |

Request |

Senate Committee-Reported |

House Committee-Reported H.R. 5634 |

Enacted P.L. 115-31, Division F |

||||||

|

State Homeland Security Grant Program |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Operation Stonegarden (carveout) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Urban Area Security Initiative |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Nonprofit Security Grants (carveout) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Public transportation security assistance and railroad security assistance |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Amtrak (carveout) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Over-the-road bus security assistance (carveout) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Port security grants |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Countering Violent Extremism |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Regional Competitive Grant Program |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Presidential Residence Protection Assistancea |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total State and Local Preparedness Grant Programs |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

Source: CRS analysis of Division F of P.L. 114-113 and its explanatory statement as printed in the Congressional Record of December 17, 2015, pp. H10161-H10210; S. 3001 and S.Rept. 114-264; H.R. 5634 and H.Rept. 114-668, and Division F of P.L. 115-31 and its explanatory statement as printed in the Congressional Record of May 3, 2017, pp. H3807-H3873.

Notes: Table displays rounded numbers, but all operations were performed with unrounded data. Amounts, therefore, may not sum to totals.

Assistance to Firefighters Grant Program (AFG)57

The Obama Administration's FY2017 budget proposed $670 million for firefighter assistance, including $335 million for AFG and $335 million for Staffing for Adequate Fire and Emergency Response (SAFER) grants, a 2.9% reduction from the FY2016 level. Under the proposed budget, the AFG and SAFER grant accounts would be transferred to the Preparedness and Protection activity under FEMA's broader Federal Assistance account. According to the budget request, Federal Assistance programs will "assist Federal agencies, States, Local, Tribal, and Territorial jurisdictions to mitigate, prepare for and recover from terrorism and natural disasters."58 Fire service groups have opposed this transfer, arguing that it could reorient the firefighter assistance program toward responding to terrorism and other major incidents rather than maintaining its current all-hazards focus.

The Senate Appropriations Committee-reported bill would have provided $680 million in firefighter assistance, including $340 million for AFG and $340 million for SAFER, a 1.4% reduction from the FY2016 level. The committee bill retained a separate budget account for Firefighter Assistance and did not transfer it to the Federal Assistance account as proposed in the Administration budget request. The committee report directed DHS to continue the present practice of funding applications according to local priorities and those established by the USFA, and to continue direct funding to fire departments and the peer review process. The committee stated its expectation that funding for rural fire departments would remain consistent with their previous five-year history, and directed FEMA to brief the committee if there is a fluctuation.

The House Appropriations Committee-reported bill would have provided $690 million in firefighter assistance, including $345 million for AFG and $345 million for SAFER. This matched the FY2016 level and was a 1.5% increase over the Senate Appropriations Committee level. Unlike the Senate, the House committee bill transferred the Firefighter Assistance budget account into a broader Federal Assistance account in FEMA. The committee report directed FEMA to continue administering the fire grants programs as directed in prior year committee reports, and encouraged FEMA to ensure that the formulas used for equipment accurately reflect current costs.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 provided $690 million for firefighter assistance in FY2017, including $345 million for AFG and $345 million for SAFER. Similar to the House bill, the firefighter assistance account was transferred to FEMA's broader Federal Assistance account as part of the CAS realignment of appropriations. The other direction from the House and Senate committee reports stands unchanged.

Budget Authority for the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP)59

While the majority of funding for the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is mandatory budget authority, the DHS appropriations act provides important direction in the use of those funds, as well as discretionary budget authority for key accounts within the NFIP. Funding for the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is primarily maintained in an authorized account called the National Flood Insurance Fund (NFIF).60

As provided for in law, all premiums from the sale of NFIP insurance are transferred to FEMA and deposited in the NFIF.61 Congress then authorizes FEMA to withdraw funds from the NFIF, and use those funds for specified purposes needed to operate the NFIP. In addition to premiums, Congress has also provided discretionary appropriations to supplement floodplain mapping activities. Table 4 provides the budget authority authorized by Congress in FY2016 and FY2017. Both Senate and House appropriations committees recommended the requested levels of funding and conditions for NFIP activities.

Table 4. Budget Authority for the NFIP, FY2016-FY2017

(thousands of dollars of budget authority, available for the fiscal year unless otherwise indicated)

|

Form of Budgetary Authority |

Activity |

FY2016 |

FY2017 (P.L. 115-31) |

|||

|

Discretionary appropriation |

Flood hazard mapping and risk analysis programa (available until expended) |

|

|

|||

|

Authorized offsetting receipts, available until end of fiscal year |

Salaries and expenses associated with flood management and insurance operationsb |

|

|

|||

|

Floodplain management and flood mappingc |

|

|

||||

|

Authorized offsetting receipts, no funds in excess of amount stipulated |

Operating expenses and salaries and expenses associated with flood insurance operations |

|

|

|||

|

Commissions and taxes of agents |

|

|

||||

|

Interest on Treasury borrowingsd |

Such sums as necessary |

Such sums as necessary |

||||

|

Flood mitigation assistancee |

|

|

||||

|

Flood Insurance Advocatef |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of P.L. 114-113 and P.L. 115-31.

Notes:

a. Generally, for necessary expenses, including administrative costs, related to the Risk Mapping, Assessment, and Planning (Risk MAP) process authorized by 42 U.S.C. §§4101, 4101a, 4101b, 4101c, 4101d, and 4101e.

b. The FY2017 budget request includes the amount of offsetting collections for flood insurance operations within the "operating expenses" activity, instead of the broader "salaries and expenses associated with flood management and flood insurance operations" activity as was done in P.L. 114-113.

c. Offsetting receipts for "floodplain management and flood mapping" have generally been viewed as supplementing the discretionary appropriation for "flood hazard mapping and risk analysis program."

d. The amount of interest paid on borrowed amounts for the U.S. Treasury fluctuates annually based on a number of factors, including the interest rate of the borrowing; the available funds for interest and principal payments after claims payments; the amount borrowed; how the debt is being serviced in loans; and fiscal decisions by FEMA to build the Reserve Fund as opposed to paying off principal and interest on the debt. FEMA reported interest payments of approximately $345.3 million for FY2016 (email correspondence from FEMA Congressional Affairs Staff, January 17, 2017).

e. Flood Mitigation Assistance is authorized by 42 U.S.C. §4104c.

f. The Flood Insurance Advocate is authorized by 42 U.S.C. §4033.

In addition to the budget authority indicated in Table 4, fluctuating levels of mandatory spending occur annually in the NFIP in order to pay claims on affected NFIP policies.62 Congress has authorized FEMA to borrow no more than $30.425 billion from the U.S. Treasury for the purposes of the NFIP, principally to pay insurance claims in excess of available premium revenues. Under the terms of the continuing resolution in P.L. 115-56, the authorization for this borrowing is reduced to $1 billion after December 8, 2017. In the wake of the hurricanes of August and September 2017, FEMA notified Congress that the NFIP had exhausted its borrowing authority on September 20, 2017.63

Emergency Food and Shelter Program (EFS)

The EFS program was established in 1985, and placed at FEMA. The rationale at that time was that the charitable groups that make up the National Board of the program wanted to emphasize that homelessness was a daily emergency. In addition, those same organizations had an established working relationship with FEMA through their disaster response and recovery work.64 While previous Administrations have suggested moving the EFS program to the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Senate Appropriations Committee's approval of such a transfer in their committee-reported FY2015 appropriations legislation was the first time the move gained any approval in Congress.

The Obama Administration's budget for FY2017 requested $100 million for the EFS program, a reduction of $20 million. The Senate Appropriations Committee concurred with the Administration's funding request while the House Appropriations Committee recommended funding the EFS program at the FY2016 level of $120 million. P.L. 115-31 included $120 million for the program.

The Senate Appropriations Committee agreed to the Obama Administration proposal to shift the program from FEMA to HUD, as long as an Interagency Agreement was executed within 60 days of the date of enactment and that the FY2018 budget included language "effectuating the transfer." The House Appropriations Committee report noted that FEMA and HUD had failed to submit a plan as required by the FY2016 DHS Appropriations Act. In the absence of a comprehensive plan "informed by comprehensive stakeholder outreach," the House did not recommend transferring the funds or administrative authority for EFS from FEMA to HUD. The House also noted that if the Administration wanted this change it could propose funding the program directly through HUD. The explanatory statement accompanying P.L. 115-31 noted that:

If future budget requests again propose moving EFSP to HUD, they should do so directly within the HUD budget, including the justification for moving the program; a plan for funds transfer, including previously obligated amounts and recoveries; a five-year strategic outlook for the program within HUD; a timeline for an interagency agreement effecting the transfer; and a description of efforts to consult with the EFSP National Board on the proposed move.65