Introduction

The U.S. Constitution provides Congress with powers over the Armed Forces, including the power "to make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces." As such, Congress has oversight of Department of Defense (DOD) policies and programs. Congressional efforts to address military sexual assault intensified in 2004 in response to rising public concern about the rate and number of assaults and perceptions of an inadequate response by the military to support the victims and to hold perpetrators accountable. In February of 2004, the Senate Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Personnel held a hearing on Policies and Programs for Preventing and Responding to Incidents of Sexual Assault in the Armed Services. In his opening statement, the ranking member, Senator E. Benjamin Nelson, stated,

We're greatly alarmed at reports of sexual assaults on our service women and the apparent failure of the military systems to respond appropriately to the needs of the victims. Women who choose to serve their Nation in military service should not have to fear sexual attacks by their fellow servicemembers. When they are victims of such an attack, they absolutely must have effective victim intervention services readily available to them, and they should not fear being punished for minor offenses when they report the attack, or being re-victimized through the investigative process.1

In the same year, Congress enacted law requiring the Secretary of Defense to develop a comprehensive policy on the prevention of sexual assaults involving servicemembers and to begin annual reporting on statistics and metrics related to sex-related violence in the military. Since 2004, Congress has enacted over 100 provisions intended to address various aspects of the problem as part of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).

The potential threat of sexual violence against military servicemembers has been part of the debates over whether women should be allowed to serve in the military and in certain combat roles, and whether they should be required to register for the selective service and be subject to a military draft. In these debates, a frequently cited concern has been the possibility that women could be captured, exposing them to potential sexual violence from enemy forces. However, the threat of sexual assault does not only come from enemy forces, nor is it only a threat for women in the military.

In the 1990s, several military sexual misconduct incidents (e.g., the Navy's 1991 Tailhook Conference, and the Army's Aberdeen Proving Ground scandal) garnered congressional attention.2 These events highlighted the internal threat of assault perpetrated by one servicemember on another. In 2003, a sexual assault scandal at the Air Force Academy again brought public attention to sexual assault in a training environment and called into question senior military leaders' efforts to establish an appropriate culture for prevention of and response to sexual assault. Shortly thereafter, allegations of sexual assaults by servicemembers on fellow servicemembers deployed to combat theaters in Iraq and Kuwait raised concerns that the prevalence of sexual violence in theater could have a negative effect on the morale and effectiveness of deployed units.3 More recently, statistics have shown that in absolute numbers, more men than women in the military report experiences with unwanted sexual contact. This has raised the profile of male sexual assault and DOD policies and programs to support male victims.4 Finally, the exposure of sexist comments and nonconsensual sharing of sexually explicit/intimate images among the Marines United social media group led many in Congress to question the impact of service culture on sexism and sexual violence.5

Sexual violence is not a problem confined to the military. Actual prevalence in the civilian sector is difficult to estimate as many experts believe sexual assault is an underreported crime. Some national surveys suggest that up to 19.3% of women and 1.7% of men in the United States have been victims of sexual assault at some point in their lives.6 There is a continued national dialogue with regard to sexual violence at universities, and other government and private organizations. Congress also has shown an interest in addressing society-wide issues through broad legal reforms. Nevertheless, there are particular aspects of military service (e.g., the possibility of remote assignments, the command structure, and the unique justice system) that may require different policy solutions than those that might apply in the civilian workplace.

Sexual assault can have both deleterious physical and psychological effects on the victim. This is particularly true if the alleged victim and perpetrator are in the same unit.7 According to a psychologist specializing in military sexual assault,

"When you are raped by a stranger, you don't have to deal with that in day-to-day life. [In the military, the victim] deals with the rape and the impact on her community and also the ongoing influence of the offender on her life outside of that specific assault."8

When an assault occurs in or around the workplace it can negatively affect the working environment and organizational functioning. In the military context, when the ability of a unit to work together effectively is impaired, it can ultimately impact mission success. Survey data from 2016 indicates that among those servicemembers who experienced sexual assault in the previous year, 73% of the incidents occurred at a military location.

What is Military Sexual Assault?

Major criminal sexual violence offenses in the military are defined in in the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), Chapter 47, Title 10 United States Code.9 Since 2006, Congress has made substantial changes to the UCMJ articles regarding these offenses. DOD policies further define sexual assault as intentional sexual contact characterized by the use of force, threats, intimidation, or abuse of authority or when the victim does not or cannot consent. While some of DOD's sexual violence policies and programs may apply to DOD civilians and military dependents, this report will focus primarily on sexual assaults involving uniformed servicemembers as alleged victims or perpetrators. This includes active component members, cadets and midshipmen, and Reserve Component members who are involved in an incident while performing active service or inactive duty training.10 Intimate partner and child sexual assaults involving military family members are typically handled by the DOD Family Advocacy Program.

The Department of Veterans Affairs handles health care needs for former servicemembers with trauma related to military sexual assault, often termed Military Sexual Trauma (MST), therefore veterans programs are beyond the scope of this report.11 Also not discussed in this report are policies and programs specific to the U.S. Coast Guard (while operating under the Department of Homeland Security), although much of the statute that applies to DOD servicemembers also applies to uniformed members of the Coast Guard and the Coast Guard Academy.12 Finally, this report does not address sexual assault at the Merchant Marine Academy, which falls under the Department of Transportation.13

Because sexual harassment can be associated with community risk factors for sexual assault, congressional efforts to combat sexual harassment in the military form part of this analysis. However, within DOD the process for handling sexual harassment complaints is separate and distinct from sexual assault allegation processes. Sexual harassment is considered a form of sex discrimination and falls under DOD military equal opportunity policies.14 DOD's Office of Diversity Management and Equal Opportunity oversees these issues.15

|

How are Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment Defined in the Military? Sexual Assault in the military is defined in DOD Instruction 6495.02 as intentional sexual contact characterized by the use of force, threats, intimidation, or abuse of authority or when the victim does not or cannot consent.16 As used in this Instruction, the term includes a broad category of sexual offenses consisting of the following specific UCMJ offenses (Articles 120 and 125): rape, sexual assault, aggravated sexual contact, abusive sexual contact, forcible sodomy, or attempts to commit these offenses (Article 80). Article 120 of the UCMJ (10 U.S.C. §920(b)) defines sexual assault punishable by court-martial for a servicemember who, (1) commits a sexual act upon another person by-- Sexual Harassment in the military is defined in 10 U.S.C. §156117 to include: (1) Conduct that— (A) involves unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and deliberate or repeated offensive comments or gestures of a sexual nature when— (i) submission of such conduct is made either explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of a person's job, pay, or career; (ii) submission to or rejection of such conduct by a person is used as a basis for career or employment decisions affecting that person; or (iii) such conduct has the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with an individual's work performance or creates an intimidating, hostile, or offensive environment; and (B) is so severe or pervasive that a reasonable person would perceive, and the victim does perceive, the environment as hostile or offensive. (2) Any use or condonation, by any person in a supervisory or command position, of any form of sexual behavior to control, influence, or affect the career, pay, or job of a member of the armed forces or a civilian employee of the Department of Defense. (3) Any deliberate or repeated unwelcome verbal comment or gesture of a sexual nature by any member of the armed forces or civilian employee of the Department of Defense. |

A Framework for Congressional Oversight

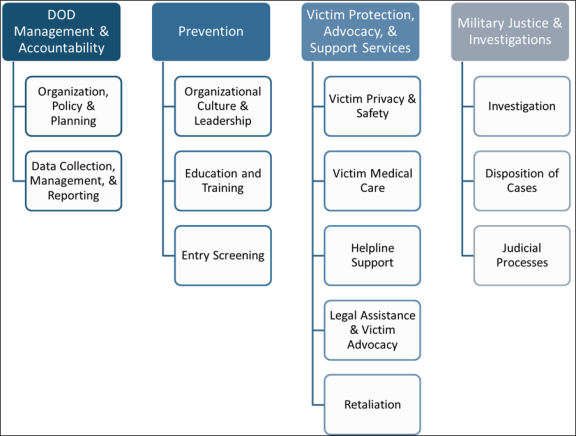

Given the extensive legislative and policy reform in this arena, CRS offers this framework for analysis and oversight. This framework may help congressional staff understand the legislative and policy landscape, link proposed policy solutions with potential impact metrics, and identify possible gaps that remain unaddressed. Congressional oversight and action on military sexual assault can be organized into four main categories.

DOD management and accountability.

Prevention.

Victim protection and support.

Military justice and investigations.

DOD management and accountability pertains to organization, monitoring, and evaluation of DOD's efforts in sexual assault prevention and response. Prevention efforts are aimed at "reducing the number of sexual assaults involving members of the Armed Forces, whether members are the victim, alleged assailant, or both."18 Victim protection and support focuses on DOD's response once an alleged assault has occurred, including actions to protect and support the victim. Finally, military justice and investigations addresses holding perpetrators accountable through military investigative and judicial processes.

|

Figure 1. Military Sexual Assault: Areas for Congressional Oversight |

|

DOD Management and Accountability

Subject to the direction of the President, the Secretary of Defense has "authority, direction, and control over the Department of Defense."19 This authority allows the Secretary to develop military personnel policies and programs. Congress, under its authority to regulate the armed forces, has taken considerable interest over the past 15 years in the effectiveness of DOD's sexual assault prevention and response initiatives, and in the disposition of military sexual assault investigations. Congress has raised questions about accountability and organization, which can generally be summarized as:

- Is DOD organized to manage and oversee sexual assault prevention and response programming effectively?

- Are appropriate policies and procedures in place and are they adequately communicated to the military departments?

- Do sufficient, rigorous, and objective data-collection processes and metrics exist to measure the extent of the problem and to evaluate DOD progress in addressing the issue?

DOD Organization, Policy, and Planning

On February 5, 2004, following allegations of sexual assault from servicemembers deployed to Iraq and Kuwait, the Secretary of Defense directed the establishment of the Care for Victims of Sexual Assault Task Force. This Task Force's report was released in April 2004. At this time, military departments and services had primarily managed sexual assault regulations and programs. One of the main findings from this report was that definitions, policies, and processes for sexual assault prevention and reporting across services were inconsistent and incomplete.20 This led the Task Force to recommend a single defense-wide point of accountability.

In response to this recommendation, DOD established the Joint Task Force for Sexual Assault Prevention and Response in October 2004.21 This Joint Task Force took responsibility for developing a new DOD-wide sexual assault policy as directed by Congress in the FY2005 NDAA (P.L. 108-375 §577). It delivered the new policy on January 1, 2005.22 At that same time, the Joint Task Force transitioned into the permanent structure that is now the Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office (SAPRO) under the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

The FY2005 NDAA also included a provision that established the Defense Task Force on Sexual Assault in the Military Services (SAMS) that renamed, expanded the scope, and extended the timelines of the existing Task Force on Sexual Harassment and Violence at the Military Service Academies.23

SAPRO Structure, Functions and Roles

The SAMS Task Force's December 2009 report made 30 recommendations for enhancing DOD SAPR programs and policies. In the area of SAPRO functions and structure, the task force noted the need for better coordination among stakeholders and improvement in staff experience levels. As such, the task force recommended

- revising the SAPRO structure to reflect the expertise necessary to lead and oversee its primary missions of prevention, response, training, and accountability;

- appointing a SAPRO director at the general or flag officer level, active duty military personnel from each Service, and an experienced judge advocate; and

- establishing a Victim Advocate position whose responsibilities and authority include direct communication with victims.24

Following this report, Subtitle A of the FY2011 NDAA formalized the role and functions of the SAPR office and programs. Section 1611 of the act provided statutory requirements and roles for the inspector general, SAPRO staff, and the director. Operating under the oversight of an Advisory Working Group the statutory duties of the SAPRO Director are to

(1) oversee implementation of the comprehensive policy for the Department of Defense sexual assault prevention and response program;

(2) serve as the single point of authority, accountability, and oversight for the sexual assault prevention and response program; and

(3) provide oversight to ensure that the military departments comply with the sexual assault prevention and response program.25

In particular, this provision required DOD to assign at least one officer from each of the Services (Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force) to the SAPRO office, and required those assigned officers to be in the grade of O-4 (Lieutenant Commander or Major) or above. The law also required at least one of the four officers assigned to be in the grade of O-6 (Captain or Colonel) or above. The FY2012 NDAA further required that the SAPRO director be a general or flag officer (GFO) or equivalent civilian employee.26

Strategic Planning and Evaluation

The SAMS Task Force 2009 report also recommended that DOD create a comprehensive sexual assault prevention strategy to aid in standardization and coordination across the Services.27 Subsequent provisions in the FY2011 NDAA (P.L. 111-383) required DOD to develop and implement a plan to evaluate sexual assault prevention and response programs and establish standards to assess progress on strategic goals.

In May 2013, DOD released its first Sexual Assault Prevention and Response (SAPR) strategic plan including five distinct lines of effort:

Prevention: deliver consistent and effective methods and programs.

Investigation: achieve high competence in the investigation of sexual assault.

Accountability: achieve high competence in holding offenders appropriately accountable.

Victim Assistance and Advocacy: deliver consistent and effective victim support, response, and reporting options.

Assessment: effectively standardize, measure, analyze, assess, and report program progress.28

DOD updated the strategic plan in January 2015 and again on December 1, 2016, for 2017-2021.29

Assessment: DOD Metrics and Non-Metrics

In 2014, in collaboration with subject matter experts, researchers and policy-makers, DOD developed a series of measurable metrics and non-metrics to "help illustrate and assess DOD progress in sexual assault prevention and response" (see Table 1).30 Metrics are included in DOD's data gathering and reporting as discussed in the next section. DOD leaders and Congress may use metrics to support oversight and to gauge whether outcomes are being met. For example, metrics such as "estimated prevalence versus reporting" may help Congress to assess whether reforms to support and protect victims of sexual assault are increasing the percentage of individuals willing to make reports and initiate investigative processes.

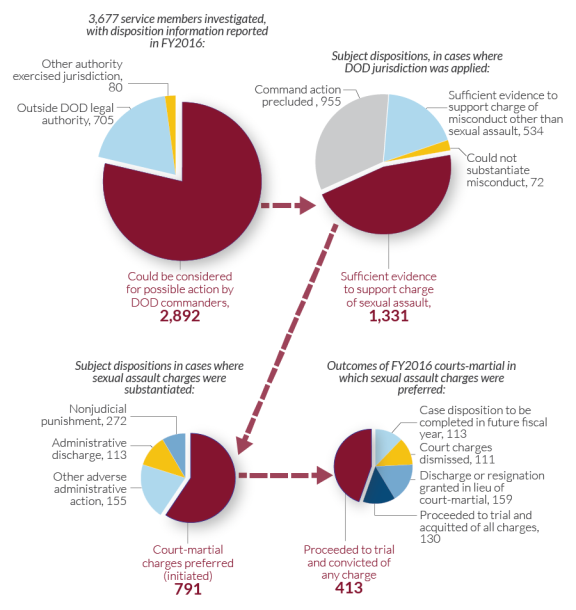

Non-metrics differ from metrics in that they are intended to be descriptive in nature only. These items address the military justice process. Any effort by military commanders to direct aspects or outcomes of the judicial process may constitute unlawful command influence in the military justice system.31 For example, if a military commander were observed trying to reduce the "time interval from report of sexual assault to nonjudicial punishment outcome" (non-metric 4), it could be perceived as pressuring investigators to forgo a thorough investigation in the interest of speed. These non-metrics may still be useful for congressional oversight, as they can indicate potential issues or trends within the military justice system.

|

Metrics |

Non-Metrics |

|

Metric 1: Past-year Prevalence of Unwanted Sexual Contact |

Non-metric 1: Command Action – Case Dispositions |

|

Metric 2: Estimated Prevalence versus Reporting |

Non-metric 2: Court-Martial Outcomes |

|

Metric 3: Bystander Intervention Experience in the Past-Year |

Non-metric 3: Time Interval from Report of Sexual Assault to Court Outcome |

|

Metric 4: Command Climate Index – Addressing Continuum of Harm |

Non-metric 4: Time Interval from Report of Sexual Assault to Nonjudicial Punishment Outcome |

|

Metric 5: Investigation Length |

Non-metric 5: Time Interval from Report of Investigation to Judge Advocate Recommendation |

|

Metric 6: All Full-time Certified Sexual Assault Response Coordinator and SAPR Victim Advocate Personnel Currently Able to Provide Victim Support |

|

|

Metric 7: Victim Experience – Satisfaction with Services Provided by Sexual Assault Response Coordinators, SAPR Victim Advocates, and Special Victims' Counsel/Victims' Legal Counsel during the Military Justice Process |

|

|

Metric 8: Percentage of Subjects with Victims Declining to Participate in the Military Justice Process |

|

|

Metric 9: Perceptions of Retaliation |

|

|

Metric 10: Victim Experience – Victim Kept Regularly Informed of the Military Justice Process |

|

|

Metric 11: Perceptions of Leadership Support for SAPR |

|

|

Metric 12: Reports of Sexual Assault over Time |

Source: DOD Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military, FY2016, Appendix C.

DOD Plan of Action for Male Sexual Assault

In 2015, in response to growing concerns about the prevalence and low reporting rates for male victims of sexual assault in the military, Congress, in the FY2016 NDAA, also required DOD to develop a plan to prevent and respond to cases of male sexual assault. DOD's plan, released in August 2016, outlined four key objectives:

Develop a unified communications plan tailored to men across the DOD.

Improve servicemember understanding of sexual assault against men.

Ensure existing support services meet the needs of males who experience sexual assault.

Develop metrics to assess prevention and response efforts pertaining to males who experience sexual assault.

In addition, DOD has put together a working group to oversee progress toward these objectives and intends to reevaluate outreach, response, and prevention efforts within three years of completion of the plan's objectives.32

Data Collection, Management, and Reporting

The availability and quality of sexual assault data are fundamental elements of accountability. DOD has provided annual reports to Congress related to sexual assault in the military since calendar year 2004—the statutory requirement for reporting was added in FY2011.33 In 2009, the SAMS Task Force report noted a lack of precision and reliability in annually reported data.34 In addition, the task force highlighted inconsistencies in terminology use among the services that could potentially affect data integration. As a result of these findings, the task force recommended several improvements to DOD's annual reporting processes. Congress has amended and expanded the statutory requirements for various elements of this report over the past decade in response to the 2009 Task Force recommendations and other information needs. For example, the FY2013 NDAA required reporting of additional case synopsis details (i.e., alcohol involvement, existence of moral waivers for offenders, etc.) and FY2015 NDAA required an analysis of the disposition of sexual assault offenses.35

DOD, Congress and other stakeholders use information from this annual report to analyze trends, evaluate SAPR program effectiveness, and develop evidence-based approaches to improve prevention and response. However, gathering data and measuring sexual assault prevalence and trends is challenging for a number of reasons. For one, sexual assault is widely considered to be the most underreported type of violent crime in the United States. According to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), Bureau of Justice Statistics' National Criminal Victimization Survey (NCVS), an estimated 34% of rapes and other sexual assaults were reported to police in 2014. This compares to robberies, of which roughly 61% were reported to the police, or domestic violence incidents, of which roughly 56% were reported.36 There are various reasons for underreporting, including personal embarrassment or shame, lack of trust in the criminal justice system, or fear of reprisals or stigmatization.37

Some researchers have cautioned against comparisons of military sexual assault statistics with civilian data, noting that, "rates of sexual assault are likely to be sensitive to the age distribution in the population, the gender balance, education levels, the proportions that are married, duty hours, sleeping accommodations, alcohol availability, and many other sexual assault risk factors that differ between the active-duty population and various candidate comparison groups." 38 In addition, data collection, comparisons, and analysis of trends are difficult when different organizations use inconsistent terminology or metrics. For example, until 2013, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) defined forcible rape as "the carnal knowledge of a female forcibly against her will."39 This definition excluded male victims and other sexual offenses that are criminal in most jurisdictions.40 In 2016, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report that highlighted the difficulties and lack of standardization across federal agencies in defining and collecting data on sexual assault. The review included four federal agencies—DOD, Department of Education, Department of Health and Human Services, and Department of Justice. According to the GAO report, these agencies,

[M]anage at least 10 efforts to collect data on sexual violence, which differ in target population, terminology, measurements, and methodology. […]These data collection efforts use 23 different terms to describe sexual violence.41

DOD definitions related to sexual assault have varied over time as has the methodology for DOD's data collection. To address the issue of consistency in definitions, Section 577 of the FY2005 NDAA required DOD to develop a uniform definition of sexual assault that applies to all the Armed Forces. Changes to the UCMJ in 2012 also affected categorization of incidents, creating a challenge for comparisons of incident indicators over time.

DOD uses various tools to collect, record, and manage sexual assault data. These tools include surveys, focus groups, and the Defense Sexual Assault Incident Database (DSAID) (see below). While some surveys are used to estimate prevalence of reported and unreported incidence of sexual violence and harassment, DSAID is used for recording actual reported incidents. As discussed above, sexual violence is often under-reported, so there are likely to be disparities between prevalence estimates and DSAID incident data.

Defense Sexual Assault Incident Database (DSAID)

Congressional actions in 2004 and subsequent legislation required DOD to enhance the collection and management of reported sexual assault incident data. In particular, Section 583 of the FY2007 NDAA required the Secretary of Defense to

[I]mplement a centralized, case-level database for the collection and maintenance of information regarding sexual assaults involving a member of the Armed Forces; including, nature of the assault, the victim, the offender, and the outcome of legal proceedings in connection with the assault.42

The provision required that this database be used to create the sexual assault-related congressional reports mandated in previous and subsequent NDAAs. The resulting database, known as the Defense Sexual Assault Incident Database (DSAID) has been in place since 2012 and was fully implemented in October 2013.43 It is the primary mechanism for tracking reported incidents, the associated circumstances, and the disposition of cases.44 DSAID has three primary functions: (1) to serve as a case management system for the maintenance of data on sexual assault cases and to track support for victims in each case; (2) to facilitate program administration and management for SAPR programs; and (3) to develop congressional reports, respond to ad hoc queries, and assist in trend analysis.45

The Defense Assault Incident Database Form is used to collect sexual assault incident data.46 This form is typically completed by a SAPR responder. The victim may choose to submit a restricted report, in which case no personally identifiable information for the victim or subject is captured on the report. If a victim selects to submit an unrestricted report, the form will include personally identifiable information, but other document privacy controls still apply.47 See Table 7 for selected aggregate incident data from FY2013 to FY2017.

In 2016 the GAO conducted a separate review of DSAID to examine the extent to which the database has met the mandated requirements.48 According to a 2017 GAO report, DOD has plans to spend $8.5 million over fiscal years 2017 and 2018 to improve DSAID, for a total expenditure of approximately $31.5 million on implementing and maintaining the database since its initial development.49

DOD Surveys and Focus Groups

DOD uses a variety of surveys and focus groups to collect data on the prevalence of and attitudes toward sexual violence and to provide feedback from servicemembers on the effectiveness of DOD prevention and response programs. These data are used for program assessment metrics and non-metrics. The Department has recently introduced additional surveys specifically for victims of sexual assault to better understand their experiences with sexual assault support programs and the military investigative and judicial processes.

|

Surveys and Focus Groups |

Target Population |

Frequency |

|

Workplace and Gender Relations Survey—Reserve Component (WGRR) |

Reserve Component servicemembers |

Biannual (even years) |

|

Workplace and Gender Relations Survey—Active Component (WGRA) |

Active Component servicemembers |

Biannual (odd years) |

|

Focus Groups on Sexual Assault Prevention and Response (FGSAPR) |

All servicemembers |

Biannual (odd years) |

|

Military Service Academy Survey |

Service Academy personnel |

Annually (academic program year) |

|

Service Academy Gender Relations Focus Groups (SAGR) |

Service Academy personnel |

Biannual (odd years) |

|

Survivor Experience Survey (SES) |

Sexual assault survivors who have made an unrestricted or restricted report of sexual assault at least 30 days prior |

Rolling basis |

|

Military Investigation and Justice Experience Survey (MIJES) |

Military servicemembers who made a formal report of sexual assault and have a closed case |

Annual, first survey complete in 2015 |

|

QuickCompass of Sexual Assault Prevention and Response-Related Responders (QSAPR) |

Sexual Assault Response Coordinators (SARCs) and Victim Advocates (VAs) |

Surveys completed in 2009, 2012, and 2015 |

|

Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute's Organizational Climate Survey (DEOCS) |

All servicemembers |

Rolling basis |

Source: Department of Defense Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office, Reports.

Notes: Participation in all surveys and focus groups is voluntary for the target population. Some metrics are captured by more than one survey.

Workplace and Gender Relations Survey

The NDAA for FY1997 (P.L. 104-201) first required DOD to include gender in mandated servicemember surveys on issues of harassment and discrimination in the military. In the FY2013 NDAA, Congress added assault to the survey requirements and mandated surveys of active duty and reserve component servicemembers every two years in alternating years beginning in 2014.50 DOD's Office of People Analytics (OPA) currently administers the Workplace and Gender Relations Survey (WGR) to measure the past-year prevalence of sexual assault, sexual harassment and gender discrimination. This survey is administered to random samples of active duty and reserve component members and used to assess the prevalence of self-reported "gender-based harassment, assault, and discrimination".51

There are some limitations to this survey. As noted by the Adult Sexual Crimes Panel in its 2014 report,

[…] this survey is not meant to—and does not—accurately reflect the number of sexual assault incidents that occur in a given year, nor can it be used to extrapolate crime victimization data. For example, the definition of unwanted sexual contact used in the survey covers a wide range of conduct that may not rise to the level of a crime.52

In particular, the survey measures "unwanted sexual conduct" and does not use the same definitions of sexual assault as those in the UCMJ. The reason for this approach is that it is assumed that the average servicemember completing the survey may not be familiar with the more technical UCMJ terms, and thus might not be able to accurately categorize the offense that they experienced.53

In 2014, a congressionally mandated panel, the Response Systems to Adult Sexual Assault Crimes Panel, recommended that DOD update its sexual assault survey language and metrics to align better with the UCMJ Article 120 definitions of rape and sexual assault. In response, DOD contracted with the RAND Corporation to review the survey methodology for the WGR and to conduct an independent assessment of sexual assault, sexual harassment, and gender discrimination in the military.54 RAND fielded two surveys; the first used the same questions as in the previous WGR survey. The second, the RAND Military Workplace Survey (RMWS) used a newly constructed crime victimization measure with more explicitly and anatomically defined terms.55 In particular, the new definitions removed the terms sex or sexual when describing an act, as the act does not need to be associated with sexual gratification to qualify as a crime under the UCMJ, but instead might be designed to humiliate or debase the person that is assaulted. RAND found that under the new survey methodology, the estimated number of self-reported assaults was higher than in previous surveys particularly in those classified as penetrative sexual assaults. The survey also pointed to a notably large difference from previous surveys in the number of assaults men reported. One of the clear findings from this survey was that men were more likely to describe a sexual assault as "hazing."56

To be measured as a sexual assault in the survey data, three requirements must be met. The member must indicate experiencing the following UCMJ-based actions by the perpetrator:

- At least one sexual assault behavior (i.e., rape, sexual assault, aggravated sexual contact, abusive sexual contact, forcible sodomy, or attempts to commit these offenses)

- At least one intent behaviors (i.e., sexual gratification, abuse, or humiliation), and

- At least one coercive mechanism (e.g., threats, use of force, inability to consent).57

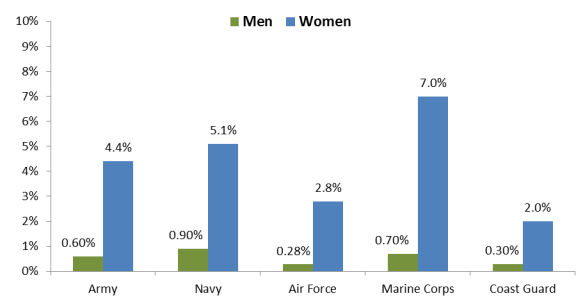

Selected results from the FY2016 survey by service are shown in Figure 2. In 2016, estimated prevalence rates across the active-duty population in DOD were 4.3% for women and 0.6% for men. These estimated prevalence rates were slightly lower than reported prevalence rates in 2014 (4.9% and 0.9% respectively).

To address findings from related civilian studies that showed higher rates of sexual assault in populations that identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT), DOD incorporated additional questions on sexual orientation in the 2016 WGRA survey.58 DOD's findings were consistent with civilian literature, indicating that LGBT members are statistically more likely to experience sexual assault than members who do not identify as LGBT (see Table 3).

|

Active Duty Servicemembers |

Identify as LGBT |

Do Not Identify as LGBT |

|

Men |

3.5% |

0.3% |

|

Women |

6.3% |

3.5% |

|

Total |

4.5% |

0.8% |

Source: DOD Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military, FY2016.

Notes: Data in this table does not include the Coast Guard.

Service Academy Gender Relations Survey and Focus Groups

Section 532 of the FY2007 NDAA, required the military departments to conduct annual assessments of the effectiveness of service academy policies, training, and procedures with respect to sexual harassment and sexual violence involving academy personnel.59 This law requires surveys be conducted in odd-numbered years. The military departments conduct focus groups at the academies in even-numbered years to supplement the annual assessment requirements.

Focus Groups on Sexual Assault Prevention and Response

Starting in 2015, DOD began including focus groups for active duty servicemembers in its assessment cycle. Like the service academy focus groups, the servicemember focus groups are conducted in alternate years to the WGRA survey to "provide deeper insights into the dynamics behind survey results and help better understand potential emerging trends."60 In the 2015 focus groups, 459 active duty members across the four services participated.

Survivor Experience Survey

The Survivor Experience Survey (SES) began in 2014 in response to a Secretary of Defense directive. DMDC's Survey Design, Analysis and Operations Branch, designed this survey in coordination with SAPRO experts. The survey gathers information related to a sexual assault survivor's awareness of, and experience with, DOD's reporting process and support services, including

- sexual assault response coordinators (SARCs),

- victims' advocates (VAs), and

- medical and mental health services.61

This survey was the first survey of survivors to be conducted across the active and reserve components. To maintain anonymity, the SES was distributed primarily through the SARCs, VAs, and legal counsels to all sexual assault survivors who had made an unrestricted or restricted report of sexual assault at least 30 days prior. The survey continues to be administered on a rolling basis.62

Military Investigation and Justice Experience Survey

The Military Investigation and Justice Survey (MIJES) is an anonymous survey first administered by DOD between August 31 and December 4, 2015. The purpose of this survey is to "provide the sexual assault victim/survivor the opportunity to assess and provide feedback on their experiences with SAPR victim assistance, the military health system, the military justice process, and other areas of support."63 The MIJES is focused only on those military servicemembers who made a formal (unrestricted) report of sexual assault and had the case closed during a specified time period.64 The survey excludes those victims whose alleged assailant was not a military member.

QuickCompass of Sexual Assault Prevention and Response-Related Responders

The QuickCompass of Sexual Assault Prevention and Response-Related Responders (QSAPR) survey is an evaluation tool administered by DMDC to provide insights on the effectiveness of DOD's sexual assault responder programs. The 2015 QSAPR was administered to all certified Sexual Assault Response Coordinators (SARCs) and Victim Advocates (VA). This is the third survey to be administered to the responder population with previous surveys in 2009 and 2012.65 The survey is intended to capture the experiences and perspectives of sexual assault responders. DOD uses the results of this survey to identify additional resource needs for responder programs, assess the degree of SAPR policy implementation across the services, and complement other surveys in understanding issues that "may discourage reporting or negatively affect perceptions of the SAPR program."66

Prevention

DOD uses the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) terminology to define prevention and prevention strategies as they apply to sexual violence.67 This section of the report mainly discusses primary prevention of sexual assault, characterized by the CDC as,

population-based and/or environmental and system-level strategies, policies, and actions that prevent sexual violence from initially occurring. Such prevention efforts work to modify and/or entirely eliminate the events, conditions, situations, or exposure to influences (risk factors) that result in the initiation of sexual violence and associated injuries, disabilities, and deaths.68

The CDC has identified four types of risk factors that are correlated with higher incidence of sexual assault, (1) individual risk factors (e.g., general aggressiveness and acceptance of violence, alcohol/drug use); (2) relationship risk factors (e.g., association with sexually aggressive, hypermasculine,69 and delinquent peers); (3) community risk factors (e.g., general tolerance of sexual violence, lack of institutional support); and (4) societal risk factors (e.g., weak gender-equity laws/policies).70 A full list of these risk factors is displayed in the Appendix in Table A-2.

Military leaders have repeatedly stated a "zero tolerance" philosophy toward military sexual assault. Nevertheless, DOD's prevention strategy acknowledges that the potential for assault exists,

"Individuals within the DoD come from a wide variety of backgrounds and their past experiences shape their attitudes and behavior in response to life events. Individuals may express themselves in different ways, and for some, violence may be a choice."71

DOD's prevention actions in this regard have been focused on reducing risk factors for sexual assault. Questions of congressional concern include:

- Are military leaders adequately trained for, committed to, and held accountable for developing an organizational culture that reduces risk factors for sexual assault?

- Are sexual assault prevention training programs in the military timely, effective, and appropriate for the target audiences?

- Does DOD have the appropriate authorities and are they taking adequate actions to screen out or deter potential perpetrators?

Organizational Culture and Leadership

Organizational culture is commonly defined as, "a pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems."72 The military's organizational culture varies both across the services (Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force) and within the services by occupational specialty (e.g., infantry, aviation, logistics). At the unit level, the organizational culture depends to a large degree on the "command climate" established by unit leadership. As such, while many of the policy changes to improve organizational culture are often initiated at a DOD-wide level, implementation of change is typically the responsibility of commanders at the unit level. These commanders may face unique community risk factors for sexual violence. For example, as stated by an Army representative:

Primary prevention is looking at what are the risks. And that differs based on the installation, unit makeup, the gender makeup, what types of units they are, and other factors. We need to understand […] the things that contribute to an environment for sexual harassment and sexual assault, […] and help those sexual assault response coordinators and victim advocates work with their commanders to understand what is the environment there, and then what they can do specifically to address those issues, to reduce incidence of sexual harassment and sexual assault."73

Identifying and Mitigating Community Risk Factors for Assault

Among active duty servicemembers who reported experiencing a sexual assault in 2016, 73% of all men and women reported that assault occurred at a military location, while 12% of women and 18% of men indicated that the assault occurred "while at an official military function."74 Research suggests that workplace culture is important in sexual assault prevention.75 While not all military assaults happen in the workplace, attitudes that are fostered in the workplace can influence servicemembers' off-duty actions.

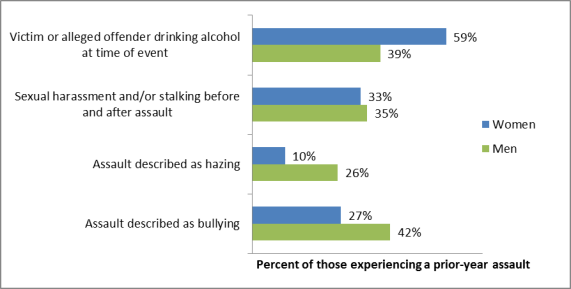

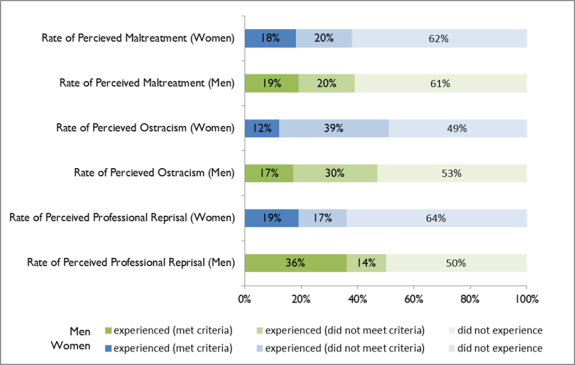

The connection between actions and circumstances leading to sexual violence are sometimes called the continuum of harm. DOD defines the continuum of harm as "inappropriate actions, such as sexist jokes, hazing, cyber bullying, that are used before or after the assault and or support an environment which tolerates these actions."76 By using existing data collected through the WGRA survey to identify the circumstances and leading indicators of sexual assaults, military commanders can take action to reduce community risk factors along this continuum and create a culture of early intervention (for selected indicators see Figure 3).

Sexual Harassment and Sexism

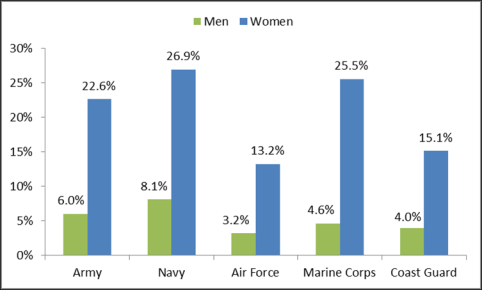

Studies have found strong positive correlations between the incidence of sexual assault within units and an environment permissive to sexism and sexual harassment. For example, a 2003 military study found that women reporting sexually hostile work environments had approximately six-fold greater odds of rape.77 The same study found that officers allowing or initiating sexually demeaning comments or gestures toward female soldiers was associated with a three-to-four-fold increase in likelihood of rape. In 2016, DOD reported that 8.1% of active duty members indicated experiencing a sexually hostile work environment in 2016, with women experiencing a sexually hostile work environment at over three times the rate as men (see Figure 4).78

The prevalence of sexual harassment in the military is estimated through survey responses and data on formal complaints. Results from the WGR surveys suggest that servicemembers experience a higher rate of sexual harassment than is actually reported. According to SAPRO data, in FY2016, there were a total of 601 formal complaints of sexual harassment across the active and reserve component;79 however, estimated prevalence rates would indicate that approximately 8% (over 100,000) servicemembers experienced sexual harassment.80 Previous reports suggest that a majority of individuals choose not to submit formal complaints with the belief that the incident "was not sufficiently serious to report or that the incident would not be taken seriously if reported."81

In 2010, in response to GAO questions about command climate and sexual harassment, a majority of servicemembers (75%) believed that their immediate supervisor made "honest and reasonable" efforts to stop sexual harassment. However, GAO also reported that 41% of servicemembers indicated that people in their workgroup would be able to get away with sexual harassment to some extent, even if it were reported. In addition 16.6% of women and 24% of males surveyed did not believe, or were unsure of whether their direct supervisor created a climate that discourages sexual harassment from occurring.82

Congress and DOD have taken actions to improve monitoring of sexual harassment. Section 579 of FY2013 NDAA (P.L. 112-239) required the Secretary of Defense to develop a comprehensive policy to prevent and respond to sexual harassment in the armed forces and to develop a plan to collect information and data regarding substantiated incidents of sexual harassment involving members of the armed forces. Congress has also sought to encourage commanders' visibility of unacceptable behavior at an early stage by requiring commanders to include documentation of substantiated sexual harassment incidents in a servicemember's performance evaluation.83

Stalking

DOD survey results from FY2014 indicated that approximately 9% of both male and female servicemembers who had experienced a sexual assault also experienced stalking prior to assault. Stalking or "grooming" behaviors are often associated with sexual harassment and sexual violence. Stalking is defined as

a pattern of repeated and unwanted attention, harassment, contact, or any other course of conduct directed at a specific person that would cause a reasonable person to feel fear.84

Outside of the military, both federal and state laws prohibit stalking. Those who violate federal stalking laws may be subject to certain criminal penalties.85 States' civil and criminal stalking laws vary. Stalking activities often include repeated nonconsensual communication (e.g., texts, phone calls), frequently following an individual, or making threats against someone or that person's family or friends. More recently, social media and technology tools have been used for stalking activities. Some examples of these are video-voyeurism—installing video cameras to give the stalker access to someone's private activities—posting threatening or private information about someone in public forums, or using spyware or GPS tracking systems to monitor someone without consent.86

In the FY2006 NDAA (P.L. 109-163), Congress added stalking to the punitive articles in the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) to "enhance the ability of the Department of Defense to prosecute offenses relating to sexual assault."87 A servicemember guilty of stalking is one,

(1) who wrongfully engages in a course of conduct directed at a specific person that would cause a reasonable person to fear death or bodily harm, including sexual assault, to himself or herself or a member of his or her immediate family;

(2) who has knowledge, or should have knowledge, that the specific person will be placed in reasonable fear of death or bodily harm, including sexual assault, to himself or herself or a member of his or her immediate family; and

(3) whose acts induce reasonable fear in the specific person of death or bodily harm, including sexual assault, to himself or herself or to a member of his or her immediate family.88

Hazing

Survey data also point to an association between hazing and sexual assault. For example, in recent surveys, 34.2% of male victims and 5.7% of female described a sexual assault they experienced as "hazing."89 In 2015, DOD defined hazing as

any conduct through which a military member or members, or a Department of Defense civilian employee or employees, without a proper military or other governmental purpose but with a nexus to military service or Department of Defense civilian employment, physically or psychologically injure or create a risk of physical or psychological injury to one or more military members, Department of Defense civilians, or any other persons for the purpose of: initiation into, admission into, affiliation with, change in status or position within, or as a condition for continued membership in any military or Department of Defense civilian organization.90

Hazing is prohibited by DOD policy and by law.91 Hazing has been associated with various military initiation rituals or ceremonies, for example the awarding of "blood wings" for completion of the Army's Air Assault School or elements of Navy's traditional "crossing the line"92 ceremony. While some argue that these are relatively harmless and fun traditions that help to build unit camaraderie, others argue that the rituals can quickly devolve into situations in which individuals may sustain physical and psychological injuries.93

A 2015 GAO report on male servicemember sexual assault found that in a group of 122 surveyed, 20% had heard of initiation-type activities that could be construed as sexual assault, and six of the respondents were able to provide first-hand accounts. Moreover, the GAO noted that two of the victim advocates they had interviewed at different installations believed that some commanders chose not to address hazing-type incidents that could have been sexual assault.94

Recently, Congress has taken measures to address hazing in the military. A provision in the FY2013 NDAA required service secretaries to report to the Armed Services Committees on hazing in their respective services to include any recommended changes to the UCMJ.95 The Senate report to accompany the bill noted,

The committee believes that preventing and responding to incidents of hazing is a leadership issue and that the service secretaries, assisted by their service chiefs, should be looked to for policies and procedures that will appropriately respond to hazing incidents.96

The FY2015 NDAA included a provision requiring a GAO report on hazing in the armed services.97 In February 2016, the GAO released its report, noting that although DOD and the Coast Guard have policies in place to address hazing, there is a lack of regular oversight and monitoring of policy implementation.98 To address some of these shortfalls, Congress included a provision in the FY2017 NDAA that required DOD to establish a hazing database, improve training, and submit annual reports on hazing to the Armed Services Committees.99

Alcohol Use

The CDC indicates alcohol use is an individual risk factor for potential perpetrators and is correlated with risk of victimization.100 For example, one study found that those who consume more than five drinks in one episode on a regular basis are at higher risk for falling victim to assault and aggressive behavior.101 It is important to note that alcohol use raises the risk of an assault occurring, but is not considered a defense for perpetrators of sexual assault under the UCMJ.102 Consumption of alcohol can impair an individual's ability to consent to sexual activities and can impair witness and bystander judgement in recognizing nonconsensual activities. In some instances alcohol may also be used as a weapon by sexual predators to reduce a victim's resistance or to fully incapacitate a victim.103

Data suggest that military servicemembers might be more prone to binge drinking than civilian counterparts, putting this demographic at higher risk. For example, survey data from 2008 found that 26% of active duty personnel aged 18 to 25 reported heavy alcohol use compared with 16% of civilians in the same age cohort.104 In 2014, nearly half of all military women and one-fourth of all military men who reported experiencing a sexual assault indicated that alcohol consumption (by the perpetrator, victim, or both) was involved in the incident.105 In addition, military service-reported sexual assault case synopses and assessments from FY2015 indicate that across DOD, alcohol use was associated with 43% of reported incidents of sexual assault. 106

DOD and the services encourage commanders to address alcohol use as part of their prevention strategies.107 For example the Navy's Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Commander's Guide suggests setting the example for responsible alcohol consumption, deglamorizing alcohol use, and developing liberty policies and strategies that limit opportunities for servicemembers to abuse alcohol. 108 Military commanders are also encouraged to create an environment where bystanders can recognize risky situations and are empowered to intervene. The Director of SAPRO described this type of intervention in a 2009 hearing before the House Armed Services Committee:

So what we are trying to do is to teach young people if they see predator-type behavior to intervene. Because we do know there are predators that will use alcohol as a weapon to reduce a woman's defenses in order in order to complete a sexual assault. So one of the things we were trying to do is to make young people aware if somebody is mixing really strong drinks for a young girl, stop it, intervene. Or if they walk out together and it just doesn't look like a good idea, they should take care of each other and maybe say we need to go in this direction. Let's not go home with him tonight or walk out with him tonight.109

Other interventions by commanders include reducing the hours of alcohol sales on military installations, increasing prices, or limiting purchase quantities. Some commands have instituted other policies such as limiting the amount of alcohol that individuals can have in the barracks or banning alcohol use for deployed units in certain areas.110 The Army and Air Force have also reported efforts to fund additional research on the role of alcohol use in sexual assault cases and on potential interventions to reduce alcohol abuse.111

Command Climate and Commander Accountability

Congress has taken some actions to hold military leadership accountable for their command climate. Section 572 of the NDAA for FY2013 required the commander of each military command to conduct a climate assessment for the purposes of preventing and responding to sexual assaults within 120 days of assuming command and at least annually thereafter.112 DOD uses the Defense Equal Opportunity Climate Survey (DEOCS) as a survey tool to measure factors associated with sexual harassment and sexual assault prevention and response, as well as other factors affecting organizational effectiveness and equal opportunity. The DEOCS may be administered to uniformed personnel and civilian employees of any DOD agency and is anonymous. The DEOCS is used at the unit level to establish a baseline assessment of the command climate. Subsequent surveys track progress relative to the baseline.113

|

Example SAPR Question on Command Climate Survey/DEOCS Response Scale: 1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Agree 4 = Strongly Agree 82. To what extent does your chain of command: a. Promote a unit climate based on "respect and trust." b. Refrain from sexist comments and behaviors. c. Actively discourage sexist comments and behaviors. d. Provide sexual assault prevention and response training that interests and engages you. e. Encourage bystander intervention to assist others in situations at risk for sexual assault or other harmful behavior. f. Disseminate information on the outcomes of sexual assault courts-martial occurring within your Service. g. Publicize sexual assault report resources (e.g., Sexual Assault Response Coordinator contact information; Victim Advocate contact information; awareness posters; sexual assault hotline phone number). h. Publicize the Restricted (confidential) Reporting option for sexual assault i. Encourage victims to report sexual assault. j. Create an environment where victims feel comfortable reporting sexual assault Source: For a full sample DEOCS survey, see https://www.deocs.net/DocDownloads/SampleDEOCSSurvey12Jan2016.pdf. |

The FY2014 NDAA imposed additional requirements on the command climate assessment by requiring the following:

- Dissemination of assessment results to the next higher level in the chain of command;

- Inclusion of evidence of compliance with command climate assessment in commanders' performance evaluations; and

- Departmental tracking of compliance with required assessments.114

Another provision in the FY2014 NDAA expressed a sense of Congress that

(1) commanding officers in the Armed Forces are responsible for establishing a command climate in which sexual assault allegations are properly managed and fairly evaluated and in which a victim can report criminal activity, including sexual assault, without fear of retaliation, including ostracism and group pressure from other members of the command;

(2) the failure of commanding officers to maintain such a command climate is an appropriate basis for relief from their command positions; and

(3) senior officers should evaluate subordinate commanding officers on their performance in establishing a command climate as described in paragraph (1) during the regular periodic counseling and performance appraisal process prescribed by the Armed Force concerned for inclusion in the systems of records maintained and used for assignment and promotion selection boards.

Education and Training

Sexual assault education and training are key components of DOD's prevention activities. According to SAPRO, education and training efforts are "designed to improve knowledge, impart a skill, and/or influence attitudes and behaviors of a target population."115 Oversight questions regarding military sexual assault training include the following:

- Is it tailored to the roles and responsibilities of the audience (commanding officers, first responders, new recruits, etc.)?

- Does the delivery and content meet the same standards across military departments?

- Is it designed based on best practices for effective training?

Standardized Training Requirements and Target Audiences

The 2009 report of the congressionally mandated Defense Task Force on Sexual Assault in the Military Services (SAMS) noted deficiencies in the curricula, design, and leadership involvement in SAPR training.116 The task force recommended tailoring training courses to better address the training needs of new recruits, responders, leadership, and peers. Subsequent congressional actions and DOD policy changes have addressed many of the task force's concerns.

In Section 585 of the FY2012 NDAA, Congress required DOD to develop sexual assault prevention training curricula for specific audiences and new modules for inclusion in each level of professional military education (PME) to better tailor the training for "new responsibilities and leadership requirements" as members are promoted.117 This provision also required that DOD consult experts in the development of the curricula and that training be consistently implemented across military departments. In fulfillment of the FY2012 NDAA requirements, DOD developed tailored SAPR training core competencies and learning objectives for specific audiences and coupled these with recommended adult learning strategies.118

In the FY2013 NDAA, Congress enacted additional training requirements for new or prospective commanders at all levels of command and for new active and reserve component recruits during initial entry training.

Further congressional action in the following year expanded certain sexual assault prevention training requirements to service academy cadets and midshipmen within 14 days after initial arrival and annually thereafter.119 In addition, Section 540 of the FY2016 NDAA required regular SAPR training for Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC) instructors and administrators.

|

Audience |

Frequency |

|

New recruits |

Within 14 days of initial entrance into active duty or duty status with a Reserve Component |

|

Service Academy cadets and midshipmen |

Within 14 days of arrival and annually while enrolled |

|

All active and reserve component members |

Annual refresher training, pre-deployment, post-deployment (within 30 days of return), as part of regular PME and leadership development training (LDT) |

|

Military recruiters |

Annually |

|

Responders |

Initially upon selection and annual responder refresher training (in addition to regular annual refresher training) |

|

DOD civilians who supervise servicemembers |

Annually |

|

New commanders |

Prior to filling a command position |

|

General/Flag Officers and Senior Executive Service |

Initial executive level program training and annually thereafter |

Source: DODI 6495.02, http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/649502p.pdf.

Notes: Covered responders include SARCs; SAPR VAs; health care personnel; DOD law enforcement; MCIOs; judge advocates; chaplains; firefighters and emergency medical technicians.

Commanders are responsible for ensuring that training is complete in accordance with all requirements. The 2009 report of the congressionally mandated Defense Task Force on Sexual Assault in the Military Services found that many servicemembers felt that leadership involvement in training is important both to reinforce the commander's zero tolerance stance and to clear up any misconceptions with regard to reporting processes and outcomes.120 In addition, the services have processes in place to monitor and report on the status of completing mandated SAPR training.121

Core Elements of Training

Section 1733 of the FY2014 NDAA (P.L. 113-66) required DOD to review and report on the adequacy of SAPR training and education provided to members of the Armed Forces. This provision also required the department to identify "common core elements" to be included in training or education programs. Current DOD policy requires all secretaries of the military departments and the Chief of the National Guard Bureau to submit a copy of their respective SAPR training elements through SAPRO to ensure consistency and compliance with standards.122

For new commanders, statutory training requirements related to prevention include

(1) Fostering a command climate that does not tolerate sexual assault.

(2) Fostering a command climate in which persons assigned to the command are encouraged to intervene to prevent potential incidents of sexual assault.

(3) Fostering a command climate that encourages victims of sexual assault to report any incident of sexual assault.

(4) Understanding the needs of, and the resources available to, the victim after an incident of sexual assault.

(5) Use of military criminal investigative organizations for the investigation of alleged incidents of sexual assault.

(6) Available disciplinary options, including court-martial, non-judicial punishment, administrative action, and deferral of discipline for collateral misconduct, as appropriate.123

DOD incorporated specialized leadership sexual assault prevention training for all military services and components as part of its 2015 strategic plan.124 Other selected elements included in annual training, new accession training, and professional military education, and, are below:

- Definitions of sexual assault and sexual harassment.

- Tips on how to recognize sexual assault.

- Strategies for bystander intervention.

- Penalties for offenders.

- Rape myths (see box below).

- Definitions of reprisal.

- Available resources for those who have been assaulted.

- Information on the impact of sexual assault on victims, units, and operational readiness.125

Pre-deployment sexual assault prevention training also includes instruction on the local history, culture, and religious practices of foreign countries and coalition partners that may be encountered on deployment.126

|

Studies on risk factors for sexual assault perpetration have found correlations with endorsement or acceptance of "rape myths."127 Rape myths are widely and persistently held attitudes or beliefs that are sometimes used to justify or excuse sexual aggression.128 Common rape myths include beliefs that, for example, women unconsciously desire to be raped or are "asking for it," that rape can only occur between strangers, or that the only victims of rape are women or gay men. Part of DOD's SAPR training is focused on dispelling these myths. |

Evaluating Training Effectiveness

There is very little literature that evaluates the quality or effectiveness of military sexual assault training programs. A 2015 analysis of Air Force training programs found that military training has adopted many of the generally accepted best practices (see "Principles of Effective Prevention Programs" box below), particularly in terms of tailoring the message to the Air Force cultural context and clearly communicating relevant information. The authors also noted that the Air Force improved the program between 2005 and 2014. The study, however, also found that a lack of program evaluation processes limited the ability to judge the effectiveness of training programs and modifications to those programs.129

|

Principles of Effective Prevention Programs130 Comprehensive. Multicomponent interventions that address critical domains (e.g., family, peers, and community) that influence the development and perpetuation of the behaviors to be prevented. Varied teaching methods. Programs involve diverse teaching methods that focus on increasing awareness and understanding of the problem behaviors and on acquiring or enhancing prevention skills. Sufficient dosage. Programs provide enough intervention to produce the desired effects and provide follow-up as necessary to maintain effects. Theory driven. Programs have a theoretical justification, are based on accurate information, and are supported by empirical research. Positive relationship. Programs provide exposure to adults and peers in a way that promotes strong relationships and supports positive outcomes. Appropriately timed. Programs are initiated early enough to have an impact on the development of the problem behavior and are sensitive to the developmental needs of participants. Socio-culturally relevant. Programs are tailored to the community and cultural norms of the participants and make efforts to include the target group in program planning and implementation. Outcome evaluation. Programs have clear goals and objectives and make an effort to systematically document their results relative to the goals. Well-trained staff. Program staff support the program and are provided with training regarding the implementation of the intervention. |

Entry Screening

Some academic literature suggests that those with a history of coerciveness or assault are at high risk of committing future assaults.131 Although few studies have been done in the military context, a study of Navy recruits based on survey data found that men who reported behavior that met the criteria for a completed sexual assault prior to their military service were over ten times more likely to commit or attempt to commit sexual assault in their first year of service than men who did not commit sexual assault prior to joining the military.132 DOD acknowledges there may be some servicemembers that may be at risk of "sexually coercive behavior." One of the goals of training is to help those individuals who may have coercive tendencies to identify appropriate behavior, recognize consequences of their actions, and dissuade them from committing sexual violence. For a smaller subset of individuals, training may not be sufficient to bring about behavioral change, and other approaches may be necessary to remove potential perpetrators from the applicant pool.133

Section 504 of Title 10 United States Code which has been in effect since 1968, prohibits any person who is "who is insane, intoxicated, or a deserter from an armed force, or who has been convicted of a felony," from enlisting in any armed force. However, the statute authorizes the Secretary of Defense to authorize exceptions in certain meritorious cases. This exercise of authority has historically been referred to as a moral waiver but may also be referred to as a conduct or character waiver.134

As military end-strength was increased to respond to conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the number of moral waivers authorized for new recruits also grew—particularly in the Army and Marine Corps. According to data provided by DOD in response to a FOIA request, approximately 18% (127,524) of new enlistees were granted a moral waiver between 2003 and 2007.135 Over half of these waivers were for traffic or drug offenses, while serious non-traffic misdemeanors (e.g., assault and petty larceny) accounted for 35%, and those with felony convictions accounted for approximately 3% of the waivers across all military services.136 These statistics raised concerns that, by enlisting those with a history of criminal activity, the military was unnecessarily putting the safety of other servicemembers at risk. Nevertheless, a 2009 report by the Defense Task Force on Sexual Assault in the Military Services found "no evidence of significantly increased disciplinary problems because of the use of waivers."137

In 2013, Congress enacted a provision in the FY2013 NDAA that amended 10 U.S.C. §504 to prohibit the Secretary of Defense from issuing a moral waiver for commissioning or enlistment in the armed forces of any individual who had been convicted of a felony offense of rape, sexual abuse, sexual assault, forcible sodomy, incest, or any other sexual offense. In the following year's NDAA, Congress enacted a new statute (10 U.S.C. §657) to prohibit the commissioning or enlistment of individuals who have been convicted of felony offenses of rape or sexual assault, forcible sodomy, incest, or of an attempt to commit these offenses.138

Victim Protection, Advocacy and Support Services

A third area of congressional focus is the provision of protection, advocacy and support services for victims of sexual assault— those currently serving and those who have been discharged or retired from military service. Although this analysis does not include congressional actions with relation to veteran services for victims of military sexual assault, it does include provisions associated with military discharges and the correction of discharge paperwork. While this section focuses on DOD services to victims of sexual assault, servicemembers may also be eligible for Department of Justice-funded programs in their respective states of residence.139

Congressional actions to protect and support victims of sexual assault fall under four main categories.

- Ensuring victim privacy and safety;

- Ensuring accessible and adequate medical and mental health services;

- Developing legal assistance programs for victims; and

- Protecting victims from retaliation or other adverse actions.

Victim Privacy and Safety

The 2004 DOD task force found that military victims of sexual assault were often reluctant to report the incident. One of the main reasons cited was a perceived lack of confidentiality.140 Victims also cited concerns about the impartiality of the command's response and the potential for retaliatory actions. Following this review, DOD implemented a number of policies and strategies to help improve confidentiality of reporting and to provide victims with a safe environment for seeking care and legal assistance. At the same time, Congress initiated a series of legislative requirements to strengthen victim support and protection.

Restricted vs. Unrestricted Reporting

In 2005, DOD instituted a restricted reporting option for sexual assault victims. This is intended to help victims receive needed support services while maintaining a certain level of privacy. When a victim chooses to make a restricted report, he or she discloses the incident to specified officials and may then gain confidential access to medical health, mental health, and victim advocacy services. Incident data is then reported by the official to SAPRO for inclusion in DOD sexual assault statistics. However, the individual's commander and law enforcement agents are not notified, nor is an official investigation initiated.141

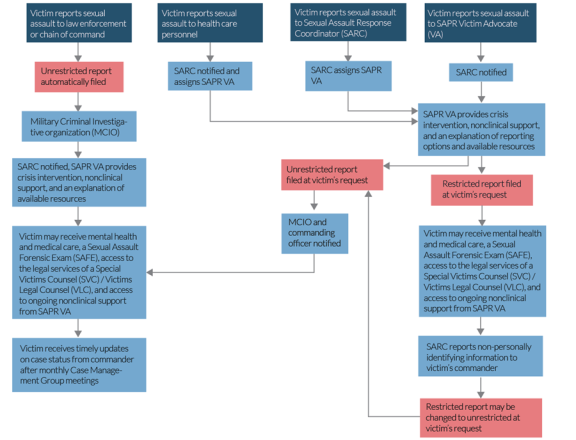

Either initially or after making a restricted report, victims may choose to make an unrestricted report of a sexual assault incident. When an unrestricted report is made, the servicemember's commanding officer is notified and a Military Criminal Investigative Office begins a formal investigation. Processes following a restricted or unrestricted report are shown in Figure 5.

DOD has deemed restricted reporting "critical" to the SAPR program.142 In addition, the availability of a restricted reporting option has generally garnered positive feedback from victims, health practitioners, and advocates. As stated by a rape victim advocate in a 2009 hearing of the House Armed Services Committee on Victim Support and Advocacy,

You heard earlier folks were talking about an increase in a number of reports, whether restricted or unrestricted is a good thing. […]We think that is a good thing. When those numbers are going up, those are fundamentally a positive move. Because it means that, number one, those folks are getting services. Number two, it means that there is an atmosphere and environment in which people believe that they can come forward, that they are safe in doing so. And so if restricted reporting enhances that, we are absolutely all for it.143

Some of the challenges that DOD has faced with protecting the victim's right to pursue the restricted reporting option include state mandatory reporting laws and other jurisdictional challenges. The FY2016 NDAA included a provision (Section 536) preempting state laws that require an individual who is a victim of sexual assault to disclose personally identifiable information except in cases when reporting "is necessary to prevent or mitigate a serious and imminent threat to the health or safety of an individual."144

Expedited Transfers and Military Protective Orders

In order to protect the safety and well-being of sexual assault victims, Congress has enacted a statute to encourage the development of policies and guidance for use of humanitarian transfers and military protective orders. Currently, when a victim makes a restricted report, he or she cannot receive a military protective order against the assailant or seek expedited transfer to a different unit or base. If the victim initiates an unrestricted report or changes his or her restricted report to an unrestricted report, he or she may then request an expedited transfer or military protective order (MPO).145

Expedited Transfers

In 2004, Congress noted that DOD did not have standard policies or protocols for removal or transfer of an alleged victim from a unit when the alleged attacker was part of the same unit or the victim's chain of command.146 The issue of transfers for victims of sexual assault was again raised by Representative Jane Harman in a 2010 hearing as a possible way to protect victims from retaliation and encourage victim reporting.147 In the FY2011 NDAA, Congress added a provision that required the Secretary concerned to provide timely consideration of an application for permanent change of station or change of duty assignment by a victim of sexual assault or related offense.148 DOD implemented this "expedited transfer" policy in February 2012149 with the stated purpose to,

[…] address situations where a victim feels safe, but uncomfortable. An example of where a victim feels uncomfortable is where a victim may be experiencing ostracism and retaliation. The intent behind the Expedited Transfer policy is to assist in the victim's recovery by moving the victim to a new location, where no one knows of the sexual assault.150

Under DOD policies, temporary or permanent transfers may be authorized to a new duty location on the same installation, or a different installation. The servicemember's transfer may include the member's dependents and military spouse for transfers to a different installation. If a servicemember's request for transfer is disapproved by the commanding officer, the individual has the right to have the request reviewed by a general or flag officer in their chain of command (or the civilian equivalent).

Although some advocacy groups have argued that the expedited transfer option is a positive support measure for victims, they have also raised concerns about the implementation, citing cases of delays and denials.151 In addition, some of the same groups have raised concerns that the transfer might actually be perceived as punishing the victim verse the alleged perpetrator. In a 2013 Senate Armed Services Committee hearing, a witness from the organization Protect Our Defenders described this problem,

We find while it is a good thing at times, expedited transfer requests, some victims say, yes, I was offered an expedited transfer, but to a job less than what I have now. Why am I being punished for being protected and trying to be sent off base? I am now being asked to make sandwiches for the pilots when once I was on another track in a successful career. Why do I have to leave? Why can't he leave?152