Overview

India—South Asia's dominant actor with about 1.3 billion citizens and the world's third-largest economy by purchasing power—has been characterized as a nascent great power and "indispensable partner" of the United States.1 Many analysts view India as a potential counterweight to China's growing international clout.2 For more than a decade, Washington and New Delhi have pursued a "strategic partnership." In 2005, the United States and India signed a ten-year defense framework agreement to expand bilateral security cooperation; in 2015, the agreement was renewed for another decade. Bilateral trade in goods and services has grown significantly, valued at over $115 billion in 2016, more than double the amount in 2006. Indians accounted for 70% of all H1-B (non-immigrant work) U.S. visas issued in FY2016, and more than 165,000 Indian students are attending U.S. universities, second only to Chinese. The influence of a relatively wealthy community of about 3 million U.S. residents of Indian descent is reflected in Senate and House India caucuses, among Congress's largest country-specific caucuses.3

President Barack Obama sought to build upon the deepened U.S. engagement with India that began under President Bill Clinton in 2000 and expanded under President George W. Bush. An annual, bilateral Strategic Dialogue, established in 2009, met five times before its September 2015 "elevation" as the "Strategic and Commercial Dialogue" (S&CD). Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi—the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader who took office in May 2014—made his first visit to the United States as prime minister in September 2014, when U.S. and Indian leaders issued a vision statement entitled "Forward Together We Go." President Obama made his second state visit to India in 2015, becoming the first U.S. President to visit India twice while in office. The resulting Joint Statement's 59 points were the most extensive and detailed ever produced by the two countries.4 The two countries issued a new "Joint Strategic Vision for the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean Region," which affirms the importance of safeguarding maritime security and includes language that could be seen as directed at a Chinese audience, with direct reference to the disputed South China Sea.5

Following the second S&CD in August 2016, U.S. officials issued a Joint Statement with their Indian counterparts that expressed "deep satisfaction" with the course of bilateral ties.6

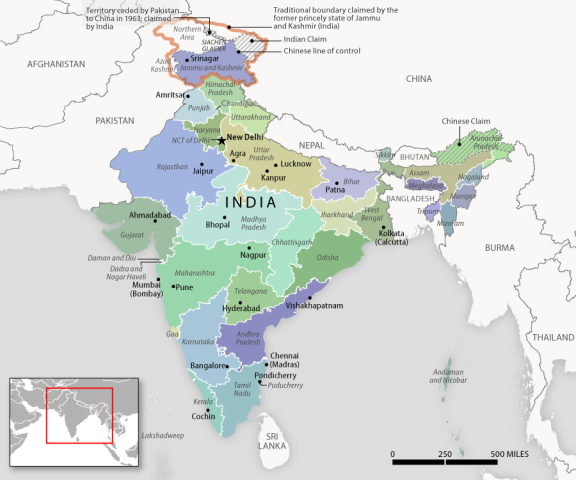

|

|

Source: Graphic created by CRS. Map information generated by [author name scrubbed], Information Research Specialist, using data from personal conversations with the Department of State (2016); Department of State international boundary files (2015); Esri (2014); and DeLorme (2014). Note: Boundary representations are not necessarily authoritative. |

Cooperation has come through dozens of institutionalized dialogue mechanisms, as well as through people-to-people contacts; investment partnerships, infrastructure and "smart cities" collaboration; environment; science, technology, and space; health and education; persistent efforts to bolster a growing defense partnership through trade and joint exercises; and myriad cooperative initiatives in energy and climate.7

India's decades of economic growth and new status as a donor government have contributed to a reduction in U.S. foreign assistance to India over time, from more than $150 million in FY2005 to $85 million in FY2016. President Donald Trump's Administration has requested $33.3 million in aid for FY2018 (see Table 2). To date, the Administration has made public only one major policy change likely to affect aspects of the course and scope of the U.S.-India partnership: a June announcement of U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on climate change, discussed below. New Delhi is closely monitoring other potential shifts in U.S. policy.

Notable Current Developments

The New U.S. Administration and India

While the Trump Administration has yet to name key policy figures for South Asia—including an Ambassador to New Delhi and relevant assistant secretaries for the region at the Departments of State and Defense—analysts have speculated on President Donald Trump's potential approach to the region. To date, the President himself has offered only limited indicators of how he might engage India going forward, but in an initial telephone conversation with Prime Minister Modi he referred to India as "a true friend and partner in addressing challenges around the world."8 In a February phone conversation with his Indian counterpart, Defense Secretary James Mattis said the Trump Administration would build upon the "tremendous progress in bilateral defense cooperation made in recent years." During an April visit to New Delhi and other regional capitals, the President's National Security Advisor, H.R. McMaster, met with Prime Minister Modi and other top Indian leaders to convey to them "the importance of the U.S.-India strategic relationship" and to reaffirm India's designation as a Major Defense Partner.9 President Trump is scheduled to meet with the visiting Indian leader in the White House in late June.

Numerous Indians appear to perceive President Trump as a "strong leader" with strident views on the threat posed by Islamist militancy. In this respect, many reportedly see in him a worthy partner for their own leader, one who may take a more adversarial posture toward India's key rival, Pakistan (recent reporting suggests that the President's Afghanistan policy may entail just this10). Some observers have thus anticipated what they refer to as a Trump-Modi "bromance" rooted in the two leaders' status as strong nationalists and their emphases on "majority grievance politics."11

However, expectations some have of personal bonhomie between the two leaders may be thwarted by substantive differences over immigration, trade, and relations with other countries, not least Iran, a major energy supplier for India. India's interest in continued immigration flows—especially as related to the movement of information technology (IT) professionals, and issuance of related H1-B and other visas to Indian nationals—has New Delhi wary of any restrictive new U.S. policies. Some Indians variously express concerns that the Trump Administration could strike a broad "G-2"-like deal with Beijing, that India may rank low on the White House's priority list, and that the U.S. President's India team may be thin and ill-prepared.12

Some observers have been comfortable with the Trump Administration's relative "silence" and "slow start" on India to date, with expectations that long-standing strategic considerations will continue to obtain and bring the two countries closer. Others note President Trump's sometimes combative style and warn that his "America First" policies and Prime Minister Modi's "Make in India" policies may prove difficult to reconcile.13

From a broad perspective, many independent analysts in both capitals express hope that the current U.S. Administration will continue the India-friendly approach taken by its two predecessors, perhaps especially to include an avoidance of the kinds of "transactional" expectations that, these observers argue, may impede progress.14 Regardless of policy preferences, most analysts in India stress the importance of having a consistent and credible U.S. actor in the region.15

U.S. Withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on Climate Change

President Trump's June announcement of U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on climate change generally was received poorly in India, where both government and private sector are focused in earnest on developing renewable energy sources (see the "Energy and Climate Issues" section below).16 During his announcement, President Trump singled out India, claiming that the country "makes its participation contingent on receiving billions and billions and billions of dollars in foreign aid from developed countries." The claim was later discredited.17 India's external affairs minister responded by telling reporters there was "absolutely no reality" in the U.S. President's allegations.18

U.S. Immigration Policy and Anti-Immigrant Sentiment in the United States

U.S. immigration policies and laws, and signs of anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States, receive headline coverage in India, where concerns about new restrictions on the former and increasing incidence of the latter are acute.

Immigration and H-1B Visas

The U.S. Administration's immigration policies, especially as related to the H-1B visa for highly-skilled foreign workers, are watched closely in India (see also the "Temporary Workers in the United States" section below). In recent years, Indian nationals have accounted for the great majority of such U.S. visa issuances—70% in FY2016—as well as work visas for their spouses.19 Critics of the H-1B program, a grouping that has included President Trump, contend that there is no shortage of qualified American workers to fill domestic jobs and that technology companies could be more energetic in efforts to recruit them.20 This argument is contested by many sector executives, who report that the number of Americans with necessary skills is insufficient.21 The President's April Executive Orders that seek to ensure only the "most skilled and highest-paid" foreign workers receive U.S. visas are aimed at protecting American jobs in the IT sector.22 Indian opposition parties have urged Prime Minister Modi to press the American leader to reconsider his decision on limiting the issuance of H-1-Bs.23

Representatives of India's IT sector—which employs some 4 million Indians and finds 60% of its business in the U.S. market—seek to promote the idea that it is a net generator of American jobs and raises billions of dollars in annual U.S. local, state, and federal tax revenue.24 According to one widely-cited 2011 analysis published by the American Enterprise Institute, "Immigrants with advanced degrees boost employment for U.S. natives," with each H-1B worker creating an average of 1.83 jobs for Americans.25 Any relevant U.S. policy shifts raise new concerns for some Indian technology companies, as well as some other observers who see a link between any efforts to slow and/or reduce the issuance of such nonimmigrant work visas and the broader anti-immigrant advocacy seen in politics.26

Pending legislation in Congress would raise the minimum annual wage for H-1B holders, currently $65,000 (H.R. 670, for example, would double that to $130,000, but IT firms resistant to such increases reportedly seek to keep the level closer to $75,000). Some analysts argue that the higher wages could erode U.S. competitiveness and so result in a net loss of jobs.27

Anti-Immigrant Sentiment

In February, an inebriated man in a Kansas bar reportedly verbally harassed two Indian nationals who were in the United States as tech workers on H-1B visas. The man reprtedly suggested they did not belong in the country before allegedly shooting both with a handgun, killing one and injuring the other. The incident sparked a wave of outrage in the Indian media, with many linking it to a perceived xenophobic populism in Donald Trump's presidential campaign (a similar incident in Washington state in March left a Sikh U.S. citizen of Indian origin with a gunshot wound).28 Alleged anti-immigrant hate crimes in the United States capture the attention of many in India, with attendant worries that the United States may be becoming less safe for India's visiting, students, scholars, and tech workers. Many prospective 2017 graduate students reportedly adjusted their plans as a result.29

India's Economy, "Demonetization," and the Goods and Services Tax (GST)

Early 2017 growth data have dented India's claims to be the world's fastest-growing major economy, with China reclaiming the title, at least temporarily. India's growth rate in the first quarter of 2017 was 6.1%, bringing an annual rate of 7.1%, down from 8% the previous fiscal year.30 May 2017 marked the third anniversary of Narendra Modi's seating as India's prime minister, spurring numerous assessments of the self-proclaimed reformer's progress at the national level. Conclusions on Modi's performance to date are decidedly mixed; one representative accounting finds little movement on the opening of markets, but sees considerable progress on liberalization and the reduction of FDI restrictions.31 Moreover, the rapid expansion of India's work force—roughly 1 million new workers enter the market each month—lead to complaints of "jobless growth" and persistent worries that India's "demographic dividend" could become a "demographic debacle."32

In part, India's economic slowdown resulted from the Modi government's demonetization policy—implemented with two-hour's notice in November 2016—which was meant to cleanse the national economy of counterfeit and black market currency. It entailed the government's announcement that 500 and 1,000 rupee notes would cease to be legal tender.33 The policy likely was harmful to India's short-term economic growth. In the longer term, however, lack of consistently robust investment, traceable largely to the existence of large-scale nonproductive loans, may be behind an apparent sputtering in India's growth rate. Some analysts contend that only deeper reforms will allow the economy to expand faster, and that the federal government needs to further remove bureaucratic obstacles, strengthen judicial and dispute resolution bodies, and ease restrictive land and labor laws.34

India's domestic commerce has long been complicated by inconsistent levies among the myriad state governments. After years of debate, the federal government succeeded in passing new legislation to establish a uniform Goods and Services Tax (GST). In May, following lengthy negotiations among all state finance ministers, the federal Finance Ministry finalized the GST rate schedule for more than 1,200 items in 5 brackets, effectively creating a single market with a greater population than the United States, Europe, Brazil, Mexico, and Japan combined.35 Implementation is expected to begin within months, with many analysts optimistic about the potential spike in interstate trade that could result.36 Moreover, a newly implemented bankruptcy law may improve the attractiveness of India's credit markets, which currently house more than $100 billion in gross nonperforming loans.37

Indian State Elections, BJP Dominance, and Hindu Nationalism

India's federal system provides significant power to the various states, and state-level politics has significant influence on both the course of national politics and on the relative levels of legal and regulatory constraints on commerce within the states. Elections to seat legislatures in five Indian states took place in March 2017, most notably in Uttar Pradesh (UP), the country's most populous state with more than 200 million residents and nearly 15% of parliamentary seats (see Figure 1). In an unexpected sweep, the BJP had won 71 of those 80 seats in the 2014 national elections—up from only 10 in 2009. The March polls were widely expected to provide a crucial measure of existing political support for the federal government of Prime Minister Modi and his party, especially in the wake of its controversial autumn 2016 "demonetization" policy.

The long-dominant Indian National Congress Party, which had been ousted at the federal level in 2014, looked to the March elections as an opportunity to recover from recent setbacks. The relatively new and corruption-focused Aad Aami Party, which runs the Delhi state government, hoped to expand its base. Meanwhile, the large caste-based regional parties traditionally strong in UP saw the elections as a chance to push back against the "BJP wave."38

All of these contenders were disappointed when the BJP took 325 of UP's 403 legislature seats (the Congress Party was able to find some solace in displacing the BJP-allied government in Punjab). The win solidified the BJP's status as the country's dominant political party, as well as Modi's apparent status as the country's most popular politician.39 It also appeared to indicate that Modi in a strong position for reelection in 2019 federal elections. The UP win will most likely lead to a BJP majority in Parliament's upper house in coming years, potentially facilitating passage of pending economic reform legislation. Meanwhile, the results brought into high relief the weakened position of India's opposition parties.40

Numerous commentators argue that apparent the new dominance of Prime Minister Modi and the BJP bode poorly for the future of India's democratic and pluralist traditions.41 This relates to some of the human rights concerns expressed by some in the U.S. Congress, among others. Modi, a self-avowed Hindu nationalist, had a controversial past as chief minister of Gujarat, but as a national politician has postured himself as a provider of economic growth and development rather than as a religious ideologue. That posture may be changing in 2017: his decision to install a Hindu cleric and hardliner, Yogi Adityanath, as UP chief minister surprised and baffled analysts, with one U.S.-based observer calling it a "regressive choice" and another labeling it "interesting and risky."42 There are new fears of rising Hindu chauvinism among many in the country's large Muslim minority of roughly 200 million persons, as well as significant Christian and other minority communities.43 (See also the "Human Rights Concerns in India" section below.)

India's Foreign Relations and U.S. Interests

India's long-held focus on maintaining "non-alignment" in the international system—more recently conceived by Indian officials as "strategic autonomy"—is, in the current century, shifting toward increased bilateral engagements, perhaps especially with the United States and with greater energy under the Modi government. At present, the most important state actors when India looks outward are Pakistan (which is often described by New Delhi as "an epicenter of terrorism" and urgent "threat") and China (a growing "challenge" now increasingly present in India's neighborhood).44 India shares lengthy disputed borders with both countries and sits astride vital sea lanes.45

New Delhi has long sought a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, a goal for which the U.S. government indicated support in 2010, when President Obama told a joint session of India's Parliament that he looked forward, "in the years ahead ... to a reformed UN Security Council that includes India as a permanent member." New Delhi today insists that it has all necessary credentials, as well as support from four of the five current permanent members (the outlier, China, has not publicly opposed).46

What follows is a brief review of five key Indian bilateral relations having direct bearing on perceived U.S. national interests, those with Pakistan, Afghanistan, China, Japan, and Iran.47 New Delhi is also pursuing an "Act East" policy in Southeast and East Asia that in some aspects dovetailed with the Obama Administration's policy of "rebalance" toward Asia.48

India-Pakistan Relations and Kashmir

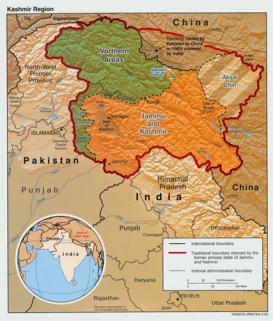

|

|

Source: Adapted by CRS. Notes: Boundary representations are not necessarily authoritative. |

The India-Pakistan border and disputed territory of Kashmir have been sites for multiple wars and are regularly identified as a potential nuclear "flashpoint." Both countries formally claim sovereignty over the former princely state, with India controlling roughly two-thirds of that territory, including the Muslim-majority Valley region (see Figure 2). New Delhi has long been wary of close U.S.-Pakistan relations, especially those involving significant transfers of funds and equipment to the Pakistani military. The decades-long history of India-Pakistan rivalry and conflict is again in a delicate phase in the early 2017, with lethal gun and artillery duels across the Kashmiri Line of Control (LOC) that separates Indian and Pakistan forces more frequent.49

Since taking office in 2014, Prime Minster Modi's government has tread cautiously with Pakistan while some of his Hindu nationalist ministers have issued belligerent rhetoric about Pakistan's assumed status as a hotbed of anti-India terrorists. Sporadic high-level engagement was cut off in mid-2015, but year's end saw new signs of Indian willingness to negotiate, culminating with Modi's surprise Christmas Day 2015 visit to Pakistan. The opening of 2016, however, again brought the fragile process into question following a January attack on an Indian military base at Pathankot, Kashmir, by Pakistan-based militants that left seven Indian soldiers dead. Then, in September, 4 heavily-armed militants raided an Indian base in Uri, Kashmir, and killed 19 soldiers before dying themselves after a day-long gun battle. Following the latter attack, New Delhi claimed to have launched a "surgical strike" against militant targets in Pakistan-held Kashmir, spurring Islamabad to condemn India's alleged "naked aggression."50

New Delhi blamed both the Pathankot and Uri attacks on the Pakistan-based Jaish-e-Mohammed terrorist group and insists that the Islamabad government cooperate in bringing alleged conspirators to justice. Many analysts saw the attacks as expressions of opposition to the India-Pakistan peace process emanating at least in part from Pakistan's military and intelligence institutions. A top Trump Administration official recently noted Pakistan's "failure to curb support to anti-India militants" and made note of "New Delhi's growing intolerance of this policy."51

Violent street protests in India's Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir state spiked after the mid-2016 killing of well-known young militant leader Burhan Wani in a firefight with Indian security forces (the region's sovereignty is disputed by Pakistan, which has actively supported armed separatist militants there). Scores of protesters were killed and many others maimed by police using controversial "non-lethal" pellet ammunition.52 In the spring of 2017, new discord is emerging with apparently rising levels of anger among youth in the Kashmir Valley, as well as civilian support for insurgency. A new spike in street protests came in May with the killing of another well-known militant commander and childhood friend of Wani's.53 Most recently, India's military says it destroyed several militant outposts on the Pakistani side of the LOC (Islamabad denies the claim) and Pakistan says five Indian soldiers were killed in a June gun battle at the LOC (New Delhi denies the claim).54

The long-standing U.S. position on Kashmir is that the issue should be resolved between India and Pakistan while taking into account the wishes of the Kashmiri people. In April 2017, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley told reporters that the Trump Administration would seek to "find its place to be a part of" efforts to de-escalate India-Pakistan tensions, suggesting that the United States might alter its policy of not engaging in the bilateral dispute. While Pakistan welcomed the statement, India quickly rejected any notion of third-party mediation of what New Delhi insists is a strictly bilateral dispute.55

India-Afghanistan Relations

The U.S.-led effort to stabilize Afghanistan has faced numerous setbacks, and a top U.S. military commander told a Senate panel in February that U.S. and allied forces there face a "stalemate."56 New Delhi takes a keen interest in maintaining positive relations with the Kabul government, and India is the largest regional contributor to Afghan reconstruction, pledging at least $2 billion toward that effort since 2001. Indian leaders say they envisage a peaceful Afghanistan that can serve as a hub for regional trade and energy flows. Geography dictates that Afghanistan serve as India's trade and transit gateway to Central Asia, but Pakistan blocks a direct route, so India has sought to develop Iran's Chabahar Port on the Arabian Sea as a means of bypassing Pakistan (see Iran discussion below).

By many accounts, India and Pakistan are vigorously jockeying for influence in Afghanistan, and high-visibility Indian targets have come under attack there, allegedly from Pakistan-based and possibly -supported militants. Indian leaders remain deeply skeptical of an apparent U.S. reliance on Pakistani interlocutors there and have taken some moves toward providing security-related assistance to the Kabul government.57 Many Indians now welcome a substantive and lasting U.S. presence in Afghanistan, a notable shift from only a few years ago.58

India-China Relations

India's relations with China have been fraught for decades, with signs of increasing enmity in recent years. A brief, but bloody 1962 India-China War left in place what is among the world's longest disputed international borders, with Beijing today formally claiming the entirety of India's Arunachal Pradesh state as its territory, calling it "South Tibet." The Chinese also take issue with the presence of the Dalai Lama and a self-described "Central Tibetan Administration" and "Tibetan Parliament in Exile" on Indian soil. The Dalai Lama's April 2017 visit to the Buddhist temple in Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh, spurred Beijing to issue a formal protest, demanding that New Delhi "stop using the Dalai Lama to do anything that undermines China's interests." It was the first such protest in nine years, and India's insistence on allowing the visit may reflect a Modi government response to China's newly expanded investment in Pakistan.59

China has long been a major supporter of Pakistan—providing advanced weapons, nuclear technology, and fulsome foreign investment—and is increasing its presence in the Indian Ocean region in ways that could potentially constrain India's regional influence. The China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a Chinese initiative to develop energy, commercial, and infrastructure links between its western Xinxiang province and Pakistan's Arabian Sea coast. CPEC is a major facet of China's broader Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also known as the One Belt One Road (OBOR).60 Formally launched in late 2014, the effort may see Beijing invest up to $60 billion in Pakistan. India formally objects to the BRI and refrains from any participation due to complaints that the transit lines run across territory claimed by India.61

Combined with ongoing Chinese outreach to other South Asian littoral states, notably including port projects in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh—and a recent sale of a pair of Chinese-built diesel-electric submarines to the latter—the CPEC and BRI have New Delhi watchful for further signs that Beijing seeks to "contain" Indian influence. By some accounts, China has shifted from establishing a presence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region to seeking preeminence there, as manifested in the BRI, thus sharpening India-China competition.62

In 2017, two key issues appear to be obstructing a turn to friendlier India-China ties. One entails Beijing's status as the sole member of the UN Security Council refusing to allow the United Nations to designate Pakistani national Masood Azhar, leader of the anti-Indian terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammed, as a "global terrorist" (China claims there is insufficient evidence to do so). Another grows from China's role as the most influential state to oppose India's accession to the Nuclear Suppliers Group, which many Indian analysts view as another of China's numerous efforts to prevent India from increasing its global influence and prestige.63

Despite these multiple sources of bilateral friction, China has emerged as India's largest trade partner in recent years. Greater Chinese investment capital, technology, and management skills is welcomed by many in India, and China has pledged to invest hundreds of billions of yuan in India over the next five years. New Delhi officials regularly state a desire to maintain non-adversarial, if not friendly relations with Beijing. In June, India (along with Pakistan) became a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).64

India-Japan Relations

India's deepening engagement with Japan is an aspect of New Delhi's broader "Act East" policy.65 Relations only began to blossom in the current century after being significantly undermined by India's 1998 nuclear weapons tests. Today, leaders from both countries acknowledge numerous common values and interests as they engage in a "strategic and global partnership" formally launched in 2006. A bilateral free trade agreement was finalized in 2011. Japanese companies have made major investments in India over the past decade, most notably with the $100 billion Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor project.

U.S., Indian, and Japanese naval vessels held unprecedented combined naval exercises in the Bay of Bengal in 2007, trilateral exercises that continue. In 2015, then-Secretary of State Kerry hosted his Indian and Japanese counterparts for the inaugural U.S.-India-Japan Trilateral Ministerial, a dialogue that has sought to highlight the growing convergence of the countries' respective interests in the Indo-Pacific region and to be a platform for strengthened three-way cooperation.66 Indian Defense Minister Arun Jaitley was in Tokyo in May to discuss with his Japanese counterpart ways to further bolster their bilateral military engagement.67

India-Iran Relations

India's relations with Iran traditionally have been positive and are marked by what successive governments in both capitals call "civilizational ties." As India has grown closer to the United States and other Western countries in recent decades, however, its Iran policy has become more nuanced. New Delhi fully cooperated with U.S.-led sanctions by significantly reducing its importation of Iranian oil before 2016, at some cost to its relationship with Tehran,68 and had previously withdrawn from a project to construct a pipeline to deliver Iranian natural gas to India through Pakistan (the "IPI" pipeline). Yet Iran remains a vital source of hydrocarbon fuels to meet India's booming energy needs, and New Delhi has committed some $500 million to develop Iran's Chabahar port, in large part to provide India with access to Central Asian markets bypassing Pakistan. Current uncertainty about U.S. policy may be causing significant delays in Chabahar's development, with international bankers reportedly unwilling to finance contracts that could run afoul of unilateral U.S. sanctions.69

U.S.-India Security Relations

The Obama Administration focused increased attention on development of closer U.S.-India defense relations during 2016; then-Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter was in India in mid-year for his fourth meeting with his Indian counterpart. The visit produced a Joint Statement reviewing "important steps" taken over the preceding year and identifying priorities for the next, including expanding collaboration under the Defense Technology and Trade Initiative (DTTI), supporting New Delhi's "Make in India" efforts to boost indigenous manufacturing, and new opportunities to deepen cooperation in maritime security and maritime domain awareness, among others.70 Before leaving office, Secretary Carter met with his Indian counterpart twice more, and departed lauding the strategic and technological progress made during his tenure.71

Proponents of deeper bilateral defense engagement—government officials and independent analysts, alike, in both capitals—expressed appreciation for the principal-level attention Carter brought to India within the U.S. government; some privately express alarm that may not be the case going forward. While DTTI engagement remains robust at the middle levels, the absence of senior-level confirmed appointees in several leadership positions in the U.S. administration is seen by some as likely to obstruct better progress, and there currently are no new arms sales in the pipeline meeting the threshold for congressional notification.72

President Obama recognized India as a "major defense partner" during Prime Minister Modi's June 2016 visit to Washington, DC, a designation allowing India to receive license-free access to dual-use American technologies that was formalized by Congress in December.73 The DTTI and Joint Technical Group (JTG) both met in New Delhi in mid-2016, with U.S. officials accompanied by representatives of several American defense firms. During the visit India inked a $1.1 billion contract to purchase an additional four Boeing P-8I Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft.74

The India-U.S. Defense Policy Group—moribund after India's 1998 nuclear tests and ensuing U.S. sanctions—was revived in 2001 and has met annually since. Its four subgroups—a Military Cooperation Group, a Joint Technology Group, a Senior Technology Security Group, and a Defense Procurement and Production Group—have met throughout the year. In 2005, the United States and India signed a ten-year defense pact outlining planned collaboration in multilateral operations, expanded two-way defense trade, increased opportunities for technology transfers and co-production, and expanded collaboration related to missile defense. In 2015, the pact was both enhanced and renewed for another ten-year period.75

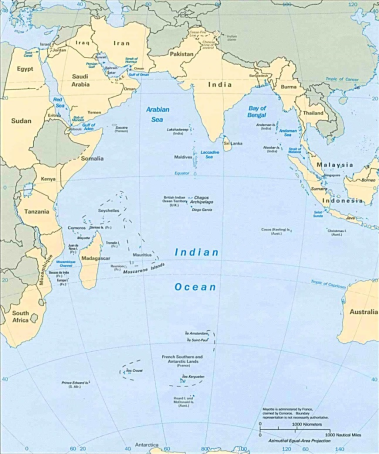

U.S.-India security cooperation has blossomed in the 21st century in a relatively new dynamic of both Asian and global geopolitics. This new U.S defense engagement with India has developed despite a concurrent U.S. rapprochement and military alliance with India's main rival, Pakistan. U.S. diplomats have rated military cooperation among the most important aspects of transformed bilateral relations, viewed the bilateral defense partnership as "an anchor of global security," and extoled India's growing role as a net provider of security in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR, see Figure 3). However, other observers call attention to what they view as significant and ongoing limitations on India's ability to fully embrace this role.76

Despite general optimism among U.S. officials and independent boosters about India's potential in this realm, some analysts contend that India's ability to influence regional security dynamics significantly will continue to remain limited in coming years and decades.77 Moreover, signs that "New Delhi remains a priggish suitor in the face of Washington's ardent embrace," as articulated by one analyst—a perceived Indian hesitance rooted largely in wariness about U.S.-Pakistan ties and an aversion to antagonizing China—may present further obstacles.78

Some Indian observers continue to express concern that the United States is a fickle partner on which India may not always rely to provide the reciprocity, sensitivity, and high-technology transfers it seeks, and that may act intrusively in defense affairs. This contributed to New Delhi's years-long political resistance to signing three "foundational" defense cooperation accords with the United States (more recently called "facilitating" agreements by U.S. officials): the Communications Interoperability and Security Memorandum of Agreement (CISMoA), the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement for Geospatial Cooperation (BECA), and the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMoA).79 In what could represent a meaningful step forward in confidence-building between the two defense establishments, New Delhi in August 2016 signed a LEMoA. The accord has yet to be operationalized, however, and reports suggest that New Delhi is showing little interest in finalizing a CISMoA or BECA.80

|

|

Source: Adapted by CRS. |

Combined Military Exercises

Since 2002, the United States and India have held a series of increasingly complex combined bilateral exercises involving all military services. Such engagement has been a key aspect of U.S.-India relations in recent years—India now conducts more exercises and personnel exchanges with the United States than with any other country. Navy-to-navy collaboration—with annual, large-scale, and now multilateral "Malabar" joint exercises—appears to be the most robust in terms of exercises and personnel exchanges. Operational readiness focuses on humanitarian relief and disaster assistance in the IOR. The 2015 iteration saw Japanese naval units rejoin the exercise after an eight-year hiatus, establishing a more formal trilateral effort; 2016 Malabar exercises saw phases in both the East China and Philippine Seas, near contested South China Sea waters. With renewed talk of a "maritime quadrilateral" that would incorporate Australian naval forces, Chinese analysts have taken an even more acute interest in the development, and the Beijing government has made its displeasure known.81

Along with major annual naval exercises, regular "Red Flag" air-to-air combat exercises allow U.S. air forces to engage late-model Russian-built Indian platforms, and "Yudh Abhyas" Special Forces simulations, held annually in jungle or mountain settings to mutually develop counterinsurgency and counterterrorism combat skills, have grown from platoon- to battalion-level exercises since their 2004 inception. Pentagon officials typically praise Indian performance in such engagements.82

Defense Trade

Defense trade is another key new aspect of the bilateral relationship, with India now a major purchaser in the global arms market and a lucrative potential customer for U.S. companies. Under the Obama Administration, the United States sought to help India modernize its defense capabilities and technologies so that New Delhi could "carry out its expanding global role." India's military is the world's third-largest, and New Delhi seeks to transform it into one with advanced technology and global reach, reportedly planning up to $100 billion on new procurements over the next decade to update its mostly Soviet-era arsenal.83 The two nations have signed defense contracts worth about $11 billion since 2008, up from $500 million in all previous years combined. U.S.-based firms Lockheed Martin and Boeing have made proposals to the Indian government on the potential co-production on Indian soil of advanced F-16 or F/A-18 combat aircraft (see text box below). In November, India signed a long-awaited $737 million contract to purchase 145 M777A2 ultralight howitzers built primarily by a Mississippi-based subsidiary of Briton's BAE systems.

|

F-16 Fighting Falcon Combat Aircraft for India? The New Delhi government has for a decade been in the market for a fleet of new fighter aircraft to replace the country's aging fleet of Soviet-era MiGs. In 2007, it launched a Medium Multi-Role Combat Aircraft (MMRCA) program to purchase 126 aircraft from a foreign supplier for about $12 billion. After reviewing bids from several suppliers, in 2011 the government settled on the French-made Dassault Rafale, but the deal fell through due to pricing disputes. In 2016, the program was officially re-launched, with Maryland-based Lockheed Martin's F-16 and Sweden's Saab Gripen as leading candidates. In this iteration, New Delhi is insisting that the winning bidder must build the aircraft in India. This condition may not be welcomed by Trump Administration officials guided by efforts to preserve American jobs, but numerous boosters of closer U.S.-India defense relations argue in favor of establishing an F-16 production line in India, contending that it would bolster bilateral interoperability and provide the two countries with an opportunity to work together on a strategically and technically significant project, thus building trust. Senator John Cornyn and Senator Mark Warner, co-chairs of the Senate India Caucus, penned a March 2017 letter to Secretary of Defense Mattis urging him to approve an F-16 production line in India, as well as approve the export of nonlethal maritime reconnaissance drones. In June, Lockheed and India-based Tata Advanced Systems announced having signed an agreement to co-produce the most advanced (Block 70) F-16s at an Indian site.84 |

Washington has in recent years sought to identify sales that can proceed under the technology-sharing and co-production model sought by New Delhi while also urging reform in India's defense offsets policy.85 In 2016, New Delhi announced a new policy—"Defense Procurement Procedure 2016"—that is geared toward creating new partnerships for indigenous defense firms, rather than mere weapons purchase agreements. Under the rubric of "Make in India," priority will be given to indigenously designed, developed, and manufactured hardware.86

For many observers, reform of India's defense procurement and management systems—including an opening of Indian firms to more effective co-production and technology sharing initiatives—is key to continued bilateral security cooperation, making high-level engagement on the DTTI a priority. Former Secretary Carter—who led the U.S. DTTI delegation in his previous role as Deputy Secretary—called the initiative complementary with India's Make in India effort.87 Progress has been identified in the areas of jet engine manufacturing, and aircraft carrier design and construction, among others.88

Intelligence and Counterterrorism Cooperation

Both Washington and New Delhi have reported effective cooperation in the areas of counterterrorism and intelligence sharing, and the January 2015 Joint Statement included a bilateral commitment to make the partnership "a defining counterterrorism relationship for the 21st century" that will combat the full spectrum of terrorist threats. Homeland security cooperation has included growing engagement between respective law enforcement agencies, especially in the areas of mutual legal assistance and extradition, and on cyberterrorism. Terrorist groups operating from Pakistani territory are of special interest, with Washington and New Delhi pursuing "joint and concerted efforts to disrupt" those entities.89

The inaugural U.S.-India S&CD of 2015 had seen then-Secretary of State Kerry and Indian Minister of External Affairs Swaraj issue a stand-alone "U.S.-India Joint Declaration on Combatting Terrorism" meant to pave the way for greater intelligence sharing and capacity-building.90 With the August 2016 S&CD summit, the Joint Statement even more directly than before emphasized bilateral attention to Pakistan-based threats, as the two sides

reiterated their condemnation of terrorism in all its forms and reaffirmed their commitment to dismantle safe havens for terrorist and criminal networks such as Da'esh/ISIL, Al-Qa'ida, Lashkar-e-Taiba, Jaish-e-Mohammad, D Company and its affiliates and the Haqqani Network. [They] called on Pakistan to bring the perpetrators of the 2008 Mumbai and 2016 Pathankot terrorist attacks to justice.91

In mid-2016, both governments welcomed cooperative initiatives to combat the threat of terrorists accessing and using nuclear and other radiological materials, exchange terrorist screening information, expedite mutual legal assistance requests, and develop further counterterrorism exchanges and programs. Bilateral law enforcement cooperation has come through the India-U.S. Homeland Security Dialogue, an engagement deferred several times in 2016.92 The U.S.-India Cyber Dialogue's fifth meeting, in September 2016, was a whole-of-government session to "exchange and discuss international cyber policies, compare national cyber strategies, enhance efforts to combat cybercrime, and foster capacity building and R&D, thus promoting cybersecurity and the digital economy."93

The U.S. and Indian governments have seen a shared threat emanating from at least one indigenous Indian terrorist organization: the Indian Mujahideen (IM), described as having close links to other U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) based in Pakistan.94 Myriad Islamist militant and terrorist groups—most of them operating from Pakistan or Afghanistan—also are identified as mutual threats. These include Al Qaeda (with an Indian-oriented affiliate, Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS)), and the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIL, ISIS, or the Arabic acronym Da'esh), with a foothold in eastern Afghanistan and active across the Afghanistan-Pakistan border as ISIL-Khorasan, but appearing to have a nominal presence in India to date.95 Numerous anti-India FTOs originate and continue to be active in Pakistan.96

Despite some reports of progress in the areas of intelligence and counterterrorism cooperation—in 2016, Secretary Kerry told an Indian audience that American and Indian intelligence agencies "now exchange information constantly"97—there has been asymmetry in the willingness of the two governments to move forward: Washington has tended to want more cooperation from India and is willing to give more in return, while it appears that officials in New Delhi remain hesitant and their aspirations are more modest. Indian wariness is likely to some degree rooted in lingering distrust of U.S. intentions, not least in Washington's ongoing security cooperation with Pakistan. Structural impediments to future cooperation also exist, according to observers in both countries. Perhaps leading among these is that India's state governments are the primary domestic security actors, and there is no significantly resourced and capable national-level body with which the U.S. federal government can coordinate.

Nuclear Weapons Proliferation and Multilateral Export Controls98

India conducted what it termed a "peaceful" nuclear explosive device in 1974; New Delhi tested such devices again in 1998. According to public estimates, the country appears to have been increasing its nuclear arsenal, which currently consists of approximately 110-120 warheads, and continues to produce weapons-grade plutonium.99 Its ballistic missile arsenal can deliver warheads on targets more than 5,000-km away—a range that encompasses China's eastern population centers. It includes air, sea, and land-based platforms, with India having completed this triad with successful submarine launches in late 2016. New Delhi has stated that it will not engage in a nuclear arms race and needs only a "credible minimum deterrent," but India has never defined precisely what this language means.

New Delhi has neither acceded to the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) nor accepted International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards on all of its nuclear material and facilities. U.N. Security Council Resolution 1172, adopted after New Delhi's 1998 nuclear tests, called on India to accede to the NPT and take other actions which New Delhi has refused, such as ratifying the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) and refraining from developing nuclear-capable ballistic missiles.

According to an Indian official, "India attaches the highest priority to global, non-discriminatory, verifiable nuclear disarmament and the complete elimination of nuclear weapons in a time-bound manner."100 Indeed, New Delhi has issued proposals for achieving global nuclear disarmament. For example, a 2007 working paper to the Conference on Disarmament (CD) called for the "[n]egotiation of a Nuclear Weapons Convention prohibiting the development, production, stockpiling and use of nuclear weapons and on their destruction, leading to the global, non-discriminatory and verifiable elimination of nuclear weapons with a specified timeframe." India's Permanent Representative to the CD reiterated this proposal in March 2017.101 Additionally, India has, despite its refusal to sign the CTBT, committed itself to a voluntary unilateral moratorium on nuclear testing.

Some observers see a "slow-moving" nuclear arms race between India and Pakistan. Islamabad is expanding its nuclear arsenal, which probably consists of approximately 130-140 nuclear warheads, according to one estimate.102 U.S. officials have expressed concern that a conventional conflict between India and Pakistan could result in those countries' use of nuclear weapons.103 India and Pakistan do have some measures in place designed to help prevent nuclear conflict. For example, the two governments agreed in 2004 to establish a "dedicated and secure hotline" between the two Foreign Secretaries "to prevent misunderstandings and reduce risks relevant to nuclear issues." The two countries also notify each other of imminent missile test in advance in accordance with an October 2005 bilateral missile pre-notification agreement.104

Following Washington's urging, the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) decided in 2008 to exempt India from the portions of its export guidelines that required India to have comprehensive IAEA safeguards.105 The United States subsequently agreed to support India's membership in the group. According to a November 8, 2010, White House fact sheet, the United States "intends to support India's full membership" in the NSG, as well as the Missile Technology Control regime (MTCR), the Australia Group, and the Wassenaar Arrangement106 "in a phased manner and to consult with regime members to encourage the evolution of regime membership criteria, consistent with maintaining the core principles of these regimes."107 India became a member of the MTCR in June 2016. The United States has continued to express support for India's membership in the other three export control regimes.108 The Trump Administration is reviewing this policy.109

The NSG has discussed India's membership on several occasions, but has not yet decided on the matter. New Delhi appears not to meet the group's membership criteria. "Factors taken into account for participation" in the NSG include adherence to and compliance with the NPT, one of the treaties establishing Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones, or "an equivalent international nuclear non-proliferation agreement," according to the NSG.110 Similarly, the Wassenaar Arrangement's Guidelines and Procedures specify a number of factors for consideration "[w]hen deciding on the eligibility of a state for participation," one of which is "adherence" to the NPT.111 Participation in the Australia Group does not appear to include this requirement.112

U.S.-India Bilateral Trade and Investment Relations

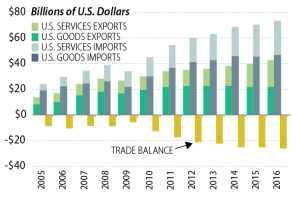

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Notes: Trade balance is for U.S. goods and services trade with India. |

The United States has viewed India—one of the world's fastest-growing economies and its third-largest on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis—as an important strategic partner in advancing common interests regionally and globally.113 In a January 2017 call between President Trump and Prime Minister Modi, the two sides discussed "opportunities to strengthen the partnership between the United States and India, including the economy.... "114

Despite its large economy and population, India is a relatively small U.S. trading partner. Two-way goods and services trade between the United States and India stood at about $115 billion in 2016 (Figure 1)—about one-fifth of U.S.-China goods and services trade that year. India ranked as the 9th largest source of U.S. goods imports and 18th largest goods export market. It is also a top U.S. partner for trade in services.115 Meanwhile, the United States is India's largest country destination for goods exports (the EU as a whole is India's largest destination) and second largest source of goods imports after China. Many observers contend there would be potential for greater bilateral trade between the United States and India if India's extensive trade and investment barriers were lessened. In 2013, the two countries expressed interest increasing their annual bilateral trade five-fold to $500 billion, including through increased engagement and initiatives.116 However, India's uneven economic reform and the limited effectiveness of bilateral engagement present potential obstacles to further expanding U.S.-India commercial ties.

India has made strides in trade liberalization since it began adopting market-oriented reforms in the 1990s. Under the Modi government, India's Foreign Trade Policy for 2015-2020 aims to increase India's exports of goods and services globally from $466 billion in 2013-2014 to about $900 billion by 2019-2020 and to raise India's share in world exports from 2% to 3.5%.117 The Modi government has announced a number of domestic initiatives, such as Make in India, Digital India, and Smart Cities, to support India's manufacturing sector and promote jobs. These initiatives may support new foreign investment opportunities. Nevertheless, protectionist policies persist in India. Some observers have attributed this to India's poverty challenges, concerns about the international competitiveness of its manufacturing and agriculture sectors, and regional economic competition with China, with which India has a large merchandise trade deficit.118

President Trump's call for a shift in the direction of certain aspects of U.S. trade policy raises further questions about the prospects for enhancing bilateral trade and investment.119 Enforcement of U.S. trade laws is a key trade priority for the Administration, with a focus on addressing "unfair" trade practices.120 In one development, on March 31, 2017, President Trump directed key agencies to prepare a report within 90 days on significant trade deficits with U.S. trading partners, including a focus on unfair trade practices and the impact of the trade deficit on U.S. production, employment, wages, and national security. The U.S. merchandise trade deficit with India was $24.4 billion in 2016—the 10th largest.121

Potential Avenues for Engagement

The United States and India have engaged on trade and investment issues internationally in a number of ways. The Trump Administration may continue past forms of engagement and/or pursue new ones.122 Potential avenues for moving forward include the following.

Bilateral Dialogues

The Trade Policy Forum (TPF), chaired by the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) and the Indian Minister of Commerce and Industry, has been a prominent bilateral dialogue in the relationship. The USTR's 2017 Trade Policy Agenda states that the United States plans to partner with India on issues of mutual interest ahead of the 2017 TPF.123 The TPF could provide a key forum to engage on bilateral trade issues. Some stakeholders see dialogues themselves as progress in a trade relationship that can sometimes be fractious, while others are keen to see dialogues yield more tangible outcomes. Other bilateral dialogues include the CEO Forum, which allows U.S. and Indian business leaders to discuss issues of joint interest and develop recommendations to both governments on commercial issues.

Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) Negotiations

Since 2009, the United States and India have engaged in negotiations on a BIT, though momentum has been uneven and negotiations presently appear to be stalled. The United States pursues BITs to obtain commitments on market access and rules to promote investment and protect investors, enforced by investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), which enables investors to take host states to arbitration for alleged violations of obligations. In recent years, each side has reviewed and revised its model BIT, the template it uses for investment negotiations. India's Model BIT, for instance, requires investors to exhaust domestic judicial remedies before seeking ISDS arbitration, which the U.S. approach has not required, in part due to the potential bias foreign investors may face when seeking redress in the host state's domestic court. If negotiations resume under the Trump Administration, questions persist about whether the two countries can bridge key differences in their model BIT templates.124

Separately, India announced its intention to replace its existing BITs with new treaties based on its new Model BIT.125 India's posture may reflect, in part, ISDS claims it has faced in recent years under current investment treaties.

Multilateral and Plurilateral Engagement

As World Trade Organization (WTO) members, the United States and India negotiate multilaterally to liberalize trade, but their differing views on key issues have impeded the Doha Round. Many issues remain outstanding. One breakthrough was the 2013 WTO "Bali package" which included a new Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) to remove customs barriers. The TFA entered into force in February 2017 with ratification by two-thirds of WTO members, including the United States (January 2015) and India (April 2016).

In other developments, India proposed negotiating a new WTO "services TFA" to address temporary entry and stay of natural persons, cross-cutting issues of transparency, and other services trade issues.126 Such issues could touch on especially politically sensitive aspects of U.S.-India trade relations. Yet, India is not participating in the plurilateral Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) negotiations outside the WTO among the United States and 22 other WTO members, as India favors engaging under the WTO framework and the Doha Round.

Outcomes for the 11th WTO Ministerial in December 2017 are uncertain. The Trump Administration's position on potential WTO issues is unclear. India's priorities include reaching a permanent solution on public stockholding for food security purposes.

The United States and India also are active users of the WTO dispute settlement process to address trade-related complaints with each other based on their WTO obligations. (See examples below.)

Bilateral Free Trade Agreement (FTA) Negotiations

The United States has 14 FTAs in force with 20 countries, but not with India, which has its own network of trade agreements. The two sides have been involved in separate regional integration efforts. The United States and 11 other Asia-Pacific countries (not including India) signed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in February 2016, but the Trump Administration, which has stated a preference for negotiating bilateral rather than multi-party FTAs, withdrew the United States as a signatory in January 2017. India reportedly viewed TPP with caution, wary of potential trade diversion such as for the apparel and textiles sector and labor-intensive sectors.

India, for its part, has been involved in ongoing negotiations for a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) with China, the ASEAN countries, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand.127 RCEP is not expected to be as extensive commitments as TPP on tariff liberalization and other areas. Some observers hold that India's cautious approach to RCEP, motivated in part by concerns about expanding market access to China, may dilute any final agreement. While TPP partners may move forward with an agreement similar to TPP, some analysts contend that a lack of U.S. participation may mean that RCEP (if completed) could take a more prominent role in establishing regional trade norms.128

Key Issues in Trade and Investment Relations

Through these various avenues, the United States and India have sought to address a range of issues present in their bilateral trade and investment relationship. Key issues include the following.129

Tariffs

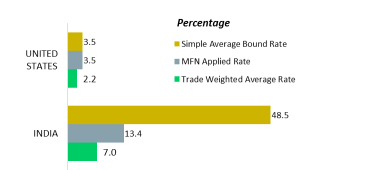

India has comparatively high average tariff rates. Under WTO commitments, India's simple average bound tariff rate is significantly higher than its simple average most-favored-nation (MFN) applied rate (Figure 5), which fuels uncertainty for U.S. businesses because India can make adjustments to its tariff regime.130 For example, India has adjusted upwards the tariffs it applies on telecommunications equipment imports in recent years (from 0% to 7.5% or 10%). India also maintains high duties on medicines (over 20% in some cases).131 India's agricultural tariffs are much higher than its non-agricultural tariffs.132 For example, by product group, India's average MFN rate is 68.6% for beverages and tobacco and in the 30% range for animal products, dairy products, and cereals and preparations.133 India's central government has been working with state governments to adopt a national goods and services tax (GST) to replace various central and state-level indirect taxes, including charges on imports, which could streamline India's complex tax structure. India plans to implement the GST in mid-2017.

|

|

Source: CRS, data from WTO, Tariff Profiles. Notes: Bound rate and MFN applied rate data are for 2015. Trade weighted average tariff rate data are for 2014. |

Services

U.S. firms face various barriers to accessing India's services market. These include India's limits on foreign ownership, such as in financial services and retail; local presence requirements, such as in banking and insurance; restrictions on foreign participation, including in education and legal services; and other regulatory issues. India also remains critical of the effect of U.S. temporary visa and social security policies on Indian nationals working in the United States. In March 2016, India filed a WTO dispute settlement case against the United States, alleging that certain U.S. fees for worker visas violate WTO General Agreement on Services (GATS) obligations. The United States has asserted that its visa program is WTO-consistent. As noted above, Indian officials have expressed concerns about legislation pending in the 115th Congress to revise H-1B visa categories for professional specialty workers.134

India continues to seek a "totalization agreement" with the United States to avoid dual taxation of income of Indian workers in the United States. A Social Security ("totalization") agreement would allow the United States and India to coordinate the collection of payroll taxes and payment of benefits under each country's Social Security system for workers who split their careers between the two countries.135 The two sides, under the Obama Administration, resolved to continue discussing the elements required for such an agreement.136

Agriculture

In addition to tariff and non-tariff barriers, including sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) standards in India, limit market access for U.S. agricultural exports. The United States challenges SPS barriers when they are not based on a scientific, risk-based perspective. The WTO Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) decided in 2015 that India's ban on importing U.S. poultry and live swine due to avian influenza concerns violated the WTO SPS Agreement.137 India's purported compliance with the decision remains a point of debate in WTO proceedings, as the United States has argued that India's revised import measures are not based on a scientific risk assessment or international standards. Other issues include each side's views of the other's agricultural support programs as market-distorting. India's view of its subsidies as a food security issue complicates matters.

Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)

The treatment of IPR is a major bilateral trade issue. Many U.S. business groups and some Members of Congress remain concerned about what they see as the inadequacy of India's IPR protection and enforcement. U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer said he was committed to addressing India IPR issues during his nomination hearing for the USTR position.138

Both countries adhere to the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement), but their views differ on the approach to IPR protection. India remained in 2017 on the Priority Watch List of the "Special 301" annual report by USTR tracking U.S. trading partners' IP protection and enforcement practices.139 The 2017 Special 301 Report acknowledged some developments in India welcomed by the United States, such as India's efforts to improve its trade secrets regime and state-level IP enforcement actions. At the same time, the report emphasized ongoing concerns with India's IP regime. In the case of patents, the report highlighted U.S. concerns with India's standards limiting the patentability of potentially beneficial pharmaceutical innovations, burdensome patent administration and dispute resolution system, and insufficient protection against unfair commercial use and unauthorized disclosure of test or other data used to obtain marketing approval for patents. The risk of compulsory licensing140 or revocation of patents by the Indian government remains a concern. Compulsory licensing concerns have intensified since 2012, when India allowed a local pharmaceutical company to produce a generic version of a kidney cancer drug by German pharmaceutical Bayer. The Indian government notes its right to use flexibilities provided under the WTO TRIPS Agreement to issue compulsory licenses subject to certain conditions.141 One reason for India's views on IPR with respect to pharmaceutical products is that it has sought to balance IPR protections with the need to provide access to medicines for its 1.3 billion people. This can be in tension with the U.S. approach, which has tended to view protection of IP as advancing access to medicines through stimulating pharmaceutical innovations.

The prevalence of counterfeit and pirated goods in India, both in physical markets and over the Internet, raises concerns about protection of copyrights and trademarks. India has not yet completed enactment of anti-camcording legislation addressing illicit videotaping of movies in theaters. India also has not joined the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) "Internet Treaties," which has provisions on IP protection in the digital environment not addressed in the TRIPS Agreement.

In May 2016, India published a new National IPR Policy to promote IP for growth and development while protecting the public interest. Some U.S. industry groups, while welcoming of the policy, say it fails to address India's biggest IP issues.142 USTR characterized the National IPR Policy as "largely avoiding discussing specific legal and policy issues" raised by U.S. and other stakeholders while devoting resources to improving IP administration and promotion commercialization and public awareness. USTR also noted that the current policy does not preclude India from adopting "more concrete reforms."143

Localization Barriers to Trade

A mounting issue is "forced" localization barriers to trade and indigenous innovation trends in India (e.g., requirements for in-country testing and data or server localization). These are measures designed to protect, favor, or stimulate domestic industries, service providers, or IP at the expense of imported goods, services, or foreign-owned or developed IP. While some localization measures may serve privacy or national security objectives, they also can be discriminatory barriers to trade.144

- In November 2011, India issued a "National Manufacturing Policy" to develop its manufacturing base and boost its employment. The policy calls for greater use of local content requirements in government procurement in certain sectors, such as information communications technology and clean energy. India's Preferential Market Access mandate, which is based on this policy, imposes local content requirements for electronic products. These and other developments continue to raise concerns for the U.S. regarding localization barriers to trade in India.

In September 2016, the WTO Appellate Body upheld a decision in favor of the United States that India's local content requirements on solar technology violated WTO non-discrimination rules.145 Separately, a WTO panel formed in March 2017 to examine India's complaint that U.S. state-level renewable energy measures are contingent on domestic content requirements and inconsistent with WTO rules.

Investment

|

|

Source: CRS, Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) data. |

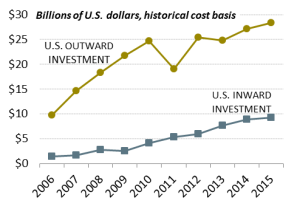

The bilateral investment relationship is small but growing (Figure 6), with India representing a fraction of U.S. outward and inward foreign direct investment (FDI). India has pursued reforms to attract FDI, such as steps to increase foreign investment limits in the insurance and defense sectors, but barriers remain. Key services industries in India, such as banking and insurance, are heavily dominated by the Indian government. Although India increased the cap on foreign investment in Indian insurance companies from 26% to 49%, it also imposed a new requirement for "Indian control" of such companies (e.g., conditions on Board of Directors members). There continue to be limits on foreign ownership in other sectors as well, such as financial services, retail, and audiovisual services. India's business environment presents barriers to FDI in sectors such as education and architecture. Foreign participation is prohibited in some sectors, such as legal services.146 India's limited regulatory transparency and judicial infrastructure for resolving investment disputes further challenges U.S. investors. U.S. FDI in India and Indian FDI in the United States are associated with U.S. jobs and exports in a range of economic sectors, but the former have prompted concerns among some analysts about offshoring of U.S. jobs to India. U.S.-India BIT negotiations (see above), if continued, may address these issues.

APEC Membership

India has long sought membership in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), a grouping of 21 economies, including the United States and China. Under the Obama Administration, the United States stated that it welcomed India in APEC.147 Some bills introduced in the 114th Congress aimed to facilitate India's membership (H.R. 4830, S. 2857), yet questions have arisen about whether India demonstrates sufficient commitment to economic liberalization to warrant APEC membership.

Generalized System of Preferences (GSP)

The U.S. GSP program provides non-reciprocal, duty-free access to the U.S. market for certain products from eligible developing countries. The program was most recently extended until December 31, 2017 (P.L. 114-27). India was GSP's largest beneficiary in 2016, with about 10% of U.S. goods imports from India under GSP. Debate exists over removing India from GSP due to U.S. concerns about shortfalls in India's IPR regime and other issues.148 The extent to which a country is providing adequate and effective IPR protection is a discretionary requirement for designating a country as a GSP beneficiary.149

Trade Financing and Promotion

Some U.S. commercial exports to and direct investment in India have benefited from U.S. government trade financing and promotion assistance, including through the agencies below, which provide support on a demand-driven basis (see Table 1).

- Export-Import Bank (Ex-Im Bank) activities in India have included support for solar technologies and power turbine exports. In more recent years limited Ex-Im Bank activity in India may reflect, in part, that the agency has not been fully operational since 2014.150

- Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) activities in India include support for microfinance lending, lending for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and solar power projects.151

- U.S. Trade and Development Agency (TDA) funding in India has spanned sectors such as aviation, energy, and infrastructure (e.g., India's Smart Cities project).152

The institutional structures of all three agencies could be subject to congressional consideration, the outcomes of which could have implications for federal support for U.S.-India trade and investment.

Table 1. Selected U.S. Trade Promotion Agencies, FY2013-2016 Activity

Millions of U.S. Dollars and India's Share of U.S. Program

|

Export-Import Bank |

Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) |

U.S. Trade and Development Agency (TDA) |

|||||||

|

Year |

India |

Global |

India Share |

India |

Global |

India Share |

India |

Global |

India Share |

|

2013 |

2,102.2 |

27,347.6 |

7.7% |

7.3 |

3,722.0 |

0.2% |

5.2 |

41.4 |

12.6% |

|

2014 |

0.5 |

20,467.9 |

< 0.01% |

84.4 |

2,643.5 |

3.2% |

4.6 |

48.8 |

9.5% |

|

2015 |

0.5 |

12,383.0 |

< 0.01% |

285.6 |

4,013.0 |

7.1% |

4.3 |

51.1 |

8.4% |

|

2016 |

1.2 |

5,037.1 |

0.02% |

494.6 |

3,126.0 |

15.8% |

6.9 |

58.5 |

11.8% |

Source: CRS, data from FY2016 annual reports of the agencies.

Notes: "India Share" refers to the share of the agency's total activity for which India accounts. OPIC activity consists of its financing (other than investment funds support) and insurance commitment. OPIC's annual report does not provide individual commitment amounts for its investment funds support.

U.S.-India Civil Nuclear Cooperation

Obstacles to initiating bilateral nuclear energy commerce have been a years-long challenge for both U.S. officials and for U.S. companies eager to enter the Indian market, but wary of exposure to regulation by strict liability laws.153 During meetings in New Delhi in 2015, President Obama and Prime Minister Modi announced a "breakthrough" compromise in the form of an Indian Memorandum of Law, which required no new legislation. Yet the announcement came with few details, and many analysts predicted that India's legal labyrinth would continue to deter American suppliers from entering the market. However, late in 2015, Pennsylvania-based Westinghouse Electric (a unit of Japan's Toshiba Corporation) moved to sign a contract for construction of six new nuclear reactors in India's southern Andhra Pradesh state. The 2016 U.S.-India Joint Statement indicated that contractual arrangements would be finalized by mid-2017, with work underway to establish "a competitive financing package based on the joint work by India and the U.S. Export-Import Bank."154 However, Westinghouse's March 2017 bankruptcy declaration has dealt a major blow to these plans.

Temporary Workers in the United States155

As noted above, an issue of keen interest to some potential workers from India is access to visas for temporary work in the United States, also referred to as nonimmigrant visas.156 Reforming the H-1B visa has been of interest to Congress for a number of reasons. Some are concerned that employers hiring H-1B nonimmigrants are displacing U.S. workers and that there are not sufficient mechanisms in place to protect U.S. workers. However, others argue that the need for more H-1B nonimmigrant workers is justified because there may not be enough qualified U.S. workers to fill open positions. Another criticism of the H-1B visa stems from an apparent lack of accountability and oversight of employers. This concern has been exacerbated by companies that contract H-1B workers through staffing companies.157

Those concerned about fraud and abuse within the H-1B visa category have cited a need for more stringent requirements for employers, the closing of perceived legislative "loopholes" that may disadvantage American workers, and increased oversight and investigative authority for relevant agencies, such as the Department of Labor.158 In April, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) announced that the agency will be taking "multiple measures to further deter and detect H-1B visa fraud and abuse."159 USCIS stated that it will continue its site visits to H-1B petitioners and the worksite of H-1B employees. More specifically, apart from random site visits, USCIS will be targeting employers with larger proportions of H-1B employees in their workforce, employers that place H-1B workers off-site (i.e., at another location or with another company), and cases where the employer's information cannot be validated through commercially available information. In addition, USCIS has created an email address that allows individuals to submit reports of suspected H-1B fraud or abuse.160 Most recently, the Department of Labor published a brief highlighting recent cases of H-1B fraud that have been successfully investigated; the cases involved several Indian nationals.161

Energy and Climate Issues162

India's large economy and its leader's aspirations to lift millions out of poverty make for growing energy demands, and India remains highly dependent on imported energy sources. Coal-fired capacity continues to account for the bulk (more than two-thirds) of India's total power installation.163 While India has embarked on a plan to dramatically increase renewable energy sourcing, it is also seeking to extend access to electricity to the roughly 20% of citizens who lack it. This effort, along with rapidly expanding Indian demand for space cooling capabilities, indicates that the country's power usage rates will continue to grow into the foreseeable future. It remains unclear whether significant U.S.-India cooperation on clean energy development and other related projects pursued under the Obama Administration will continue under the Trump Administration. The U.S.-India Energy Dialogue, through which such projects as the eight-year-old Partnership to Advance Clean Energy (PACE) were coordinated, was considered by Indian officials to be a vital forum for bilateral engagement.164

Many experts have argued that India's status among the world's emitters of greenhouse gases—by one accounting it contributed 6.8% of global CO2 emissions in 2015165—makes it a necessary participant in any comprehensive solution to the problems posed by climate change. India's CO2 emissions increased 67% from 1990 to 2012 and today are roughly the same as Russia's, meaning the country can variously be ranked third, fourth, or fifth in the world depending on the aggregation or disaggregation of European Union member-state data. However, India's large population makes it the world's tenth-largest emitter on a per capita basis.

India signed the Paris Agreement on climate change in April 2016 and ratified the Agreement in October. By some metrics, India and China are outpacing the United States on efforts to address climate change.166 During a visit to Paris shortly after the June announcement of U.S. withdrawal from the Agreement, Prime Minister Modi reportedly told the French president that India intended to "go above and beyond" the agreement's targets.167 New Delhi has pledged to boost India's use of non-fossil fuel energy to 40% by 2030.168

Within this renewables mix will be greatly expanded power generation from solar, wind, and nuclear sources. India may be in the midst of one of history's largest energy transformation project, with a rapidly growing renewables sector.169 Indians are also working to address the huge power losses that come through wastage.170 The country has seen at drastic decline in the cost of generation from solar and wind sources; a kilowatt hour of solar power that recently cost 12 cents now costs less than 4, about one-quarter cheaper than the same amount of energy from coal. This has led the Indian government to cancel some planned new coal plant projects and cut its coal production target by nearly 10%.171

Human Rights Concerns in India