Since the 1970s, policymakers have increasingly used the tax code to promote energy policy goals. Long-term energy policy goals include providing a secure supply of energy, providing energy at a low cost, and ensuring that energy production and consumption is consistent with environmental objectives.1 A range of federal policies, including various research and development programs, mandates, and direct financial support such as tax incentives or loan guarantees, promote various energy policy objectives. This report focuses on tax incentives that support the production of or investment in various energy resources.2

Through the mid-2000s, the majority of revenue losses associated with energy tax incentives have resulted from provisions benefitting fossil fuels. At present, the balance has shifted, such that the bulk of federal revenue losses associated with energy tax provisions are from incentives for renewable energy production and investment.3 While there has been growth in the amount of energy from renewable resources, the majority of domestic energy produced continues to be from fossil energy resources. This has raised questions regarding the value of energy tax incentives relative to production and the relative subsidization of various energy resources.

Although the numbers in this report may be useful for policymakers evaluating the current status of energy tax policy, it is important to understand the limitations of this analysis. This report evaluates energy production relative to the value of current energy tax expenditures. It does not, however, seek to analyze whether the current system of energy tax incentives is economically efficient, effective, or otherwise consistent with broader energy policy objectives.4 Further, analysis in this report does not include information on federal spending on energy that is not linked to the tax code.5

Tax Incentives Relative to Energy Production

The following sections estimate the value of tax incentives relative to the level of energy produced using fossil and renewable energy resources. Before proceeding with the analysis, some limitations are outlined. The analysis itself requires quantification of energy production and energy tax incentives. Once data on energy production and energy tax incentives have been presented, the value of energy tax incentives can be evaluated relative to current levels of energy production.

Limitations of the Analysis

The analysis below provides a broad comparison of the relative tax support for fossil fuels as compared with the relative support for renewables. Various data limitations prevent a precise analysis of the amount of subsidy per unit of production across different energy resources. Limitations associated with this type of analysis include the following:

- Current-year tax incentives may not directly support current-year production

Many of the tax incentives available for energy resources are designed to encourage investment, rather than production. For example, the expensing of intangible drilling costs (IDCs) for oil and gas provides an incentive to invest in capital equipment and exploration. Although the ability to expense IDCs does not directly support current production of crude oil and natural gas, such subsidies are expected to increase long-run supply.

- Differing levels of federal financial support may or may not reflect underlying policy rationales

Various policy rationales may exist for federal interventions in energy markets. Interventions may be designed to achieve various economic, social, or other policy objectives. Although analysis of federal financial support per unit of energy production may help inform the policy debate, it does not directly consider why various energy sources may receive different levels of federal financial support.

- Tax expenditures are estimates

The tax expenditure data provided by the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) are estimates of federal revenue losses associated with specific provisions.6 These estimates do not provide information on actual federal revenue losses, nor do these estimates reflect the amount of revenue that would be raised should the provision be eliminated.7 Additionally, the JCT advises that tax expenditures across provisions not be summed, due to interaction effects.

- Tax expenditure data are not specific to energy source

Many tax incentives are available to a variety of energy resources. For example, the tax expenditure associated with the expensing of IDCs does not distinguish between revenue losses associated with natural gas versus those associated with oil. The tax expenditure for five-year accelerated depreciation also does not specify how much of the benefit accrues to various eligible technologies, such as wind and solar.

- A number of tax provisions that support energy are not energy specific

The U.S. energy sector benefits from a number of tax provisions that are not targeted at energy. For example, the production activities deduction (Section 199) benefits all domestic manufacturers.8 For the purposes of the Section 199 deduction, oil and gas extraction is considered a domestic manufacturing activity.9 Certain energy-related activities may also benefit from other tax incentives that are available to non-energy industries, such as the ability to issue tax-exempt debt,10 the ability to structure as a master limited partnership,11 or tax incentives designed to promote other activities, such as research and development.

Energy Production

The Energy Information Administration (EIA) provides annual data on U.S. primary energy production. EIA defines primary energy as energy that exists in a naturally occurring form, before being converted into an end-use product. For example, coal is considered primary energy, which is typically combusted to create steam and then electricity.12

This report relies on 2016 data on U.S. primary energy production (see Table 1).13 Coal and natural gas are the two largest primary energy production sources, representing 17.6% and 32.6% respectively of primary energy production in 2016. Crude oil constituted 22.1% of primary energy production. Taken together, fossil energy sources were used for 77.9% of 2016 primary energy production.

The remaining U.S. primary energy production is attributable to nuclear electric and renewable energy resources. Overall, 10.0% of 2016 U.S. primary energy was produced as nuclear electric energy. Renewables (including hydroelectric power) constituted 12.1% of 2016 U.S. primary energy production.

Biomass was the largest source of production among the renewables in 2016, accounting for 5.6% of overall primary energy production or nearly half of renewable energy production. This was followed by hydroelectric power at 2.9% of primary energy production. The remaining three resources, wind, solar, and geothermal, were responsible for 2.5%, 0.7%, and 0.3% of 2016 primary energy production, respectively (see Table 1).

Primary energy produced using biomass can be further categorized as biomass being used to produce biofuels (e.g., ethanol) and biomass being used to generate biopower.14 Of the 4.7 quadrillion Btu of energy produced using biomass, about 2.3 quadrillion Btu was used in the production of biofuels.15,16

|

Source |

Quadrillion Btua |

Percent of Total |

||

|

Fossil Fuels |

||||

|

Coal |

14.8 |

17.6% |

||

|

Natural Gas |

27.4 |

32.6% |

||

|

Crude Oil |

18.6 |

22.1% |

||

|

Natural Gas Plant Liquids |

4.7 |

5.6% |

||

|

Nuclear |

|

|||

|

Nuclear Electric |

8.4 |

10.0% |

||

|

Renewable Energy |

|

|||

|

Biomassb |

4.7 |

5.6% |

||

|

Hydroelectric Power |

2.5 |

2.9% |

||

|

Wind |

2.1 |

2.5% |

||

|

Solar/PV |

0.6 |

0.7% |

||

|

Geothermal |

0.2 |

0.3% |

||

|

Total |

88.0 |

100.0% |

||

Source: CRS analysis of data from Energy Information Administration, Table 1.2 Primary Energy Production by Source, April 25, 2017, available at https://www.eia.gov/totalenergy/.

Notes: Columns may not sum due to rounding.

a. A British thermal unit (Btu) is the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of one pound of water 1 degree Fahrenheit.

b. Within the biomass category, 2.3 quadrillion Btu can be attributed to biofuels. Biofuels constituted 2.7% of total primary energy production in 2015.

Energy Tax Incentives

The tax code supports the energy sector by providing a number of targeted tax incentives, or tax incentives only available for the energy industry. In addition to targeted tax incentives, the energy sector may also benefit from a number of broader tax provisions that are available for energy- and non-energy-related taxpayers.17 These broader tax incentives are not included in the analysis, since tax expenditure estimates do not indicate how much of the revenue loss associated with these generally available provisions is associated with energy-related activities.

Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) tax expenditure estimates are used to tabulate federal revenue losses associated with energy tax provisions.18 The tax expenditure estimates provided by the JCT are forecasted revenue losses. These revenue losses are not reestimated on the basis of actual economic conditions. Thus, revenue losses presented below are projected, as opposed to actual revenue losses.

The JCT advises that individual tax expenditures cannot be simply summed to estimate the aggregate revenue loss from multiple tax provisions. This is because of interaction effects. When the revenue loss associated with a specific tax provision is estimated, the estimate is made assuming that there are no changes in other provisions or in taxpayer behavior. When individual tax expenditures are summed, the interaction effects may lead to different revenue loss estimates. Consequently, aggregate tax expenditure estimates, derived from summing the estimated revenue effects of individual tax expenditure provisions, are unlikely to reflect the actual change in federal receipts associated with removing various tax provisions.19 Thus, total tax expenditure figures presented below are an estimate of federal revenue losses associated with energy tax provisions, and should not be interpreted as actual federal revenue losses.

Table 2 provides information on revenue losses and outlays associated with energy-related tax provisions in FY2016.20 In 2016, the tax code provided an estimated $18.2 billion in support for the energy sector. Roughly one-third of the 2016 total, $6.0 billion, was due to tax credits supporting renewables.21 The largest provision in Table 2 is the $3.6 billion for biodiesel tax credits, which includes the effects of both income and excise tax provisions. The biodiesel tax credits, along with a number of other energy tax provisions, expired at the end of 2016.22

Nine different provisions supporting fossil fuels had an estimated cost of $5.2 billion, collectively, in 2016. While the majority of federal tax-related support for energy in 2016 can be attributed to either fossil fuels or renewables, provisions supporting energy efficiency, alternative technology vehicles, nuclear energy, and other energy-related activities did result in foregone revenue in 2016.23

|

Provision |

2016 Cost |

|

|

Fossil Fuels |

||

|

Credits for investments in Clean Coal Facilities |

0.2 |

|

|

Expensing of Exploration and Development Costs: Oil and Gas |

1.8 |

|

|

Excess of Percentage over Cost Depletion: Oil and Gas |

0.7 |

|

|

Excess of Percentage over Cost Depletion: Other Fuels |

0.2 |

|

|

Amortization of Geological and Geophysical Expenditures Associated with Oil and Gas Exploration |

0.1 |

|

|

Amortization of Air Pollution Control Facilities |

0.5 |

|

|

15-year Depreciation Recovery Period for Natural Gas Distribution Lines |

0.2 |

|

|

Exceptions for Publicly Traded Partnerships with Qualified Income Derived from Certain Energy-Related Activities |

0.9 |

|

|

Alternative Fuel Mixture Credit |

0.6 |

|

|

Subtotal, Fossil Fuels |

5.2 |

|

|

Renewables |

||

|

Energy Credit, Investment Tax Credit (ITC) |

2.6 |

|

|

Production Tax Credit (PTC) |

3.4 |

|

|

Residential Energy-Efficient Property Credit |

1.1 |

|

|

Credit for Investment in Advanced Energy Property |

0.3 |

|

|

5-year Depreciation Recovery Period for Certain Energy Property (solar, wind, etc.) |

0.3 |

|

|

Treasury Grant in Lieu of Tax Credit |

0.1 |

|

|

Subtotal, Renewables |

7.8 |

|

|

Efficiency |

||

|

Credit for New Energy-Efficient Homes |

0.4 |

|

|

Deduction for Energy-Efficient Commercial Buildings |

0.2 |

|

|

Credit for Energy-Efficient Improvements to Existing Homes |

0.5 |

|

|

Subtotal, Efficiency |

1.1 |

|

|

Renewable Fuels |

||

|

Biodiesel Tax Credits |

3.6 |

|

|

Subtotal, Renewable Fuels |

3.6 |

|

|

Alternative Technology Vehicles |

||

|

Credit for Plug-In Electric Vehicles |

0.3 |

|

|

Subtotal, Alternative Technology Vehicles |

0.3 |

|

|

Nucleara |

||

|

Special Tax Rate for Nuclear Decommissioning Reserve Fund |

0.2 |

|

|

Subtotal, Nuclear |

0.2 |

|

|

Other |

||

|

Special Rule to Implement Electric Transmission Restructuring |

-0.2 |

|

|

10-year Depreciation Recovery Period for Smart Electric Distribution Property |

0.1 |

|

|

15-year Depreciation Recovery Period for Certain Electric Transmission Property |

0.1 |

|

|

Subtotal, Other |

0.0 |

|

|

Total |

18.2 |

|

Source: Congressional Budget Office, Federal Support for Developing, Producing, and Using Fuels and Energy Technologies, Washington, DC, March 29, 2017, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/52521-energytestimony.pdf and Joint Committee on Taxation, Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2016 – 2020, JCX-3-17, January 30, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4971.

Notes: Provisions with a revenue score of less than $50 million during all years are omitted from the table.

a. The JCT tax expenditure list includes the special tax rate for nuclear decommissioning reserve funds in the "National Resources and Environment" budget function. Other tax expenditures for nuclear were either classified as de minimis (the advanced nuclear power production tax credit) or non-quantifiable (accelerated deductions for nuclear decommissioning costs) in the 2017 tax expenditure publication.

Fossil Fuels Versus Renewables: Relative Production and Tax Incentive Levels

Table 3 provides a side-by-side comparison of fossil fuel and renewable production, along with the cost of tax incentives supporting fossil fuel and renewable energy resources.24 During 2016, 77.9% of U.S. primary energy production could be attributed to fossil fuel sources. Of the federal tax support targeted to energy in 2016, an estimated 28.6% of the value went toward supporting fossil fuels. During 2016, an estimated 12.1% of U.S. primary source energy was produced using renewable resources. Of the federal tax support targeted to energy in 2016, an estimated 62.6% went toward supporting renewables.

Since current energy production is the result of past investment decisions, some of which may not have benefitted from targeted tax incentives, it may not always be appropriate to compare the current value of tax incentives to current levels of energy production. For example, energy generated using hydroelectric power technologies might be excluded from the renewables category, as most existing hydro-generating capacity was installed before the early 1990s.25 Thus, there is no current federal tax benefit for most electricity currently generated using hydropower.26 Further, with many of the best hydro sites already developed, there is limited potential for growth in conventional hydropower capacity. There is, however, potential for development of additional electricity-generating capacity through smaller hydro projects that could substantially increase U.S. hydroelectric generation capacity.27 Excluding hydro from the renewables category, non-hydro renewables accounted for 8.7% of 2016 primary energy production.

|

Production |

Tax Incentives |

|||

|

Quadrillion Btu |

% of Total |

Billions of Dollars |

% of Total |

|

|

Fossil Fuels |

65.6 |

77.9% |

$5.2 |

28.6% |

|

Renewables |

10.1 |

12.1% |

$11.4 |

62.6% |

|

7.7 |

8.7% |

$11.4 |

62.6% |

|

|

Renewables (excluding biofuels and related tax incentives) |

7.9 |

9.0% |

$7.8 |

42.9% |

|

Renewables (excluding hydroelectric and biofuels and related tax incentives) |

5.4 |

6.1% |

$7.8 |

42.9% |

|

Nuclear |

8.4 |

10.0% |

$0.2 |

1.1% |

Source: Calculated using data presented in Table 1 and Table 2 above.

Notes: Tax incentive shares do not sum to 100% as some incentives are for efficiency or alternative technology vehicles.

a. Renewables tax incentives include targeted tax incentives designed to support renewable electricity and renewable fuels.

b. The value of total tax incentives for renewables excluding hydroelectric power is less than the total value of tax incentives when those available for hydropower are included. However, the difference is small. JCT estimates that in 2016, the tax expenditures for qualified hydropower under the PTC are less than $50 million.

During 2016, certain tax expenditures for renewable energy did, however, benefit taxpayers developing and operating hydroelectric power facilities. Certain hydroelectric installations, including efficiency improvements or capacity additions at existing facilities, may be eligible for the renewable energy production tax credit (PTC). Given that hydro is supported by 2016 tax expenditures, one could also argue that hydro should not be excluded from the renewables category.

It may also be instructive to consider incentives that generally support renewable electricity separately from those that support biofuels.28 Of the estimated $18.2 billion in energy tax provisions in 2016, an estimated $3.6 billion, or 19.8%, went toward supporting biofuels. Excluding tax incentives for biofuels, 42.9% of energy-related tax incentives in 2016 were attributable to renewables. In other words, excluding biofuels from the analysis reduces the share of tax incentives attributable to renewables from 62.6% to 42.9%. Excluding biofuels from the analysis has a smaller impact on renewables' share of primary energy production. When biofuels are excluded, the share of primary energy produced in 2016 attributable to renewables falls by 3.1 percentage points, from 12.1% to 9.0%.

In 2016, 10.0% of primary energy produced was from nuclear resources.29 The one tax benefit for nuclear with a positive tax expenditure in 2016 was the special tax rate for nuclear decommissioning reserve funds. At $0.2 billion in 2016, this was 1.1% of the value of all tax expenditures for energy included in the analysis. Like many other energy-related tax expenditures, the special tax rate for nuclear decommissioning reserve funds is not directly related to current energy production. Instead, this provision reduces the cost of investing in nuclear energy by taxing income from nuclear decommissioning reserve funds at a preferred rate (a flat rate of 20%).

Energy Tax Incentive Trends30

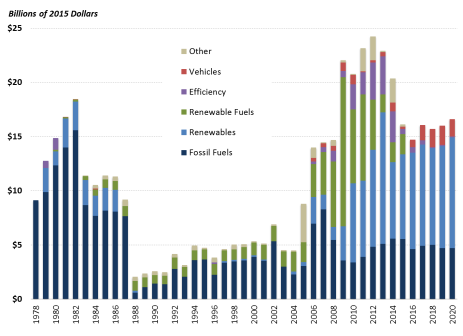

Over time, there have been substantial shifts in the proportion of energy-related tax expenditures benefitting different types of energy resources. Figure 1 illustrates the projected value of energy-related tax incentives since 1978.31 Energy tax provisions are categorized as primarily benefitting fossil fuels, renewables, renewable fuels, efficiency, vehicles, or some other energy purpose.

Until the mid-2000s, most of the value of energy-related tax incentives supported fossil fuels. In recent years, tax expenditures for fossil fuels have remained stable, while tax expenditures for other types of energy resources have increased.32

From the 1980s through 2011, most of the tax-related federal financial support for renewable energy was for renewable fuels, mainly alcohol fuels (i.e., ethanol).33 The tax credits for alcohol fuels (including ethanol) expired at the end of 2011. Starting in 2008, the federal government incurred outlays associated with excise tax credits for biodiesel and renewable diesel. Under current law, the tax credits for biodiesel and renewable diesel expired at the end of 2016. Thus, after 2016, there are no projected costs associated with tax incentives for renewable fuels.34 Expired tax incentives may be extended, however, as part of the "tax extenders."35

Beginning in the mid-2000s, the cost of energy tax incentives for renewables began to increase. Beginning in 2009, the Section 1603 grants in lieu of tax credits contributed to increased costs associated with tax-related benefits for renewable energy.36 Through 2014, Section 1603 grants in lieu of tax credits exceeded tax expenditures associated with the production tax credit (PTC) and investment tax credit (ITC) combined.37 The Section 1603 grant option is not available for projects that began construction after December 31, 2011. However, since grants are paid out when construction is completed and eligible property is placed in service, outlays under the Section 1603 program are expected to continue through 2017.

Tax expenditures for the ITC and PTC have increased substantially in recent years. As a result of the extensions for wind and solar enacted in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113), ITC and PTC tax expenditures are projected to continue to increase in the coming years. Under current law, the PTC will not be available to projects that begin construction after December 31, 2019. However, since the PTC is available for the first 10 years of renewable electricity production, PTC tax expenditures will continue after the provision expires. The ITC for solar, currently 30%, is scheduled to decline to 26% in 2020, and 22% in 2021, before returning to the permanent rate of 10% after 2021. Thus, the recent increase in PTC and ITC tax expenditures does not reflect a permanent policy change.

Tax expenditures for tax incentives supporting energy efficiency increased in the late 2000s, but are projected to decline in coming years. Most of the increase in revenue losses for efficiency-related provisions was associated with tax incentives for homeowners investing in certain energy-efficient property.38 The primary tax incentive for energy efficiency improvements to existing homes expired at the end of 2016.39 Extension of expired tax incentives for energy efficiency would increase the cost of energy efficiency-related tax incentives.

As was noted above, much of the projected cost of energy-related tax incentives in the out years is associated with expired or expiring provisions. Costs for certain provisions may extend beyond expiration for a number of reasons. In the case of the Section 1603 grant program, since outlays occur when property is placed in service, costs for this program will continue to be incurred long past its 2011 expiration date. Another example is the renewable energy PTC. The PTC is available for the first 10 years of production from a qualified facility. Thus, property placed in service in 2016 may claim production tax credits into 2026. Revenue losses associated with tax provisions can also extend beyond a provision's expiration when taxpayers are allowed to carry forward unused tax credits, using credits to offset liability in future tax years.

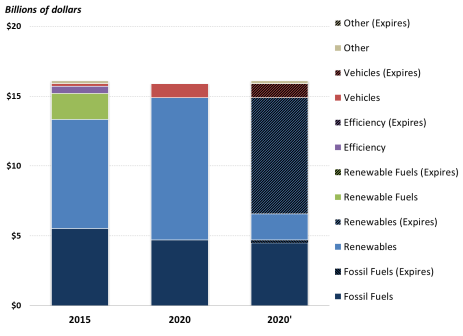

Figure 2 illustrates the relative importance of permanent versus temporary tax incentives for different types of energy resources. The first column shows the projected cost of energy tax provisions in 2015 (the same as the column for 2015 in Figure 1). The second column shows the projected cost of current law energy tax provisions in 2020 (again, the same as the column for 2020 in Figure 1). The third column in Figure 2 (2020') illustrates what proportion of the projected cost of energy tax incentives in 2020 is associated with provisions that have an expiration date or are otherwise limited.40

Most of the projected cost of energy tax incentives in 2020 is associated with incentives for renewables (under current law, renewable fuels incentives have expired, and thus are not scheduled to be available in 2020). However, much of this cost in 2020 is associated with the PTC, which will have expired but can still be claimed by taxpayers in the 10-year period of qualifying production. With most of the budget cost arising from expired tax provisions, there will be limited incentives for new investment in renewables.

In contrast to tax incentives for renewables, most of the tax incentives that support fossil fuels are permanent features of the tax code. Thus, the cost associated with fossil-fuels-related tax incentives is projected to be stable over the next few years.

|

Figure 2. Projected Cost of Energy Tax Provisions: FY2015 and FY2020 Changes Associated with Limited or Expiring Provisions |

|

|

Source: CRS using data from the Joint Committee on Taxation and Office of Management and Budget. Notes: See Figure 1 notes. Shaded sections in the 2020' column are tax expenditures associated with provisions that either expired or are subject to an allocation limit (or similar type of limitation). |

Concluding Remarks

The energy sector is supported by an array of tax incentives reflecting diverse policy objectives. As a result, the amount of tax-related federal financial support for energy differs across energy sectors, and is not necessarily proportional to the amount of energy production from various energy sectors. The total amount of energy-related tax incentives is projected to remain stable, between $15 billion and $16 billion per year through 2020, although extensions of expired energy tax provisions, or modifications to energy tax provisions through tax reform, could change these figures. Over the longer term, the amount of tax-related support for the energy sector could decline if provisions are allowed to expire as scheduled under current law.