Introduction

For 30 years, the Nunn-McCurdy Act (10 U.S.C. §2433) has served as one of the principal mechanisms for notifying Congress of cost overruns in Major Defense Acquisition Programs (MDAPs).1 The act establishes thresholds to determine if an MDAP or designated major subprogram of an MDAP experiences a cost overrun.2 (For purposes of this report, the term program refers to MDAPs as well as designated major subprograms.) Nunn-McCurdy thresholds are based on a comparison between a program's actual costs and the current baseline estimate or original baseline estimate (defined below). A program that has cost growth that exceeds any of these thresholds is said to have a Nunn-McCurdy breach and the Department of Defense (DOD) must notify Congress of the breach.

Background

In the early days of the Reagan Administration, a number of high-profile weapon systems, including the Black Hawk helicopter and the Patriot missile system, experienced substantial cost overruns. Responding to public concern over escalating cost growth, Senator Sam Nunn and Representative David McCurdy spearheaded the passage of the Nunn-McCurdy Act, which was intended to create a reporting requirement for programs experiencing cost overruns.3 It was believed that publicly exposing cost overruns would force DOD to rein in cost growth. According to Representative McCurdy,

The assumption behind the Nunn-McCurdy provision of the fiscal 1983 defense authorization bill was that the prospect of an adverse reaction from the Office of Management and Budget, Congress, or the public would force senior Pentagon officials to address the question of whether the program in question—at their newly reported, higher costs—were worth continuing.4

Nunn-McCurdy was not originally intended to create a mechanism for managing programs or allocating funds. The rationale for an after-the-fact report was a matter of some debate. During floor debate on the original amendment in 1981, Senator John Tower, then chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, said that the reporting requirements were like "closing the gate after the horse has galloped off into the boondocks."5

What is a Nunn-McCurdy Breach?

Nunn-McCurdy Thresholds

There are two categories of breaches: significant breaches and critical breaches. As shown in Table 1, a "significant" Nunn-McCurdy breach occurs when the Program Acquisition Unit Cost or the Procurement Unit Cost increases 15% or more over the current baseline estimate or 30% or more over the original baseline estimate. A "critical" breach occurs when the Program Acquisition Unit Cost (PAUC) or Procurement Unit Cost (PUC) increases 25% or more over the current baseline estimate or 50% or more over the original baseline estimate.6

|

Significant Breach |

Critical Breach |

|

|

Current Baseline Estimate |

≥15% |

≥25% |

|

Original Baseline Estimate |

≥30% |

≥50% |

Source: 10 U.S.C. §2433.

What Is a Program Acquisition Unit Cost and Procurement Unit Cost?

A Program Acquisition Unit Cost is defined as the total cost of development, procurement, and construction divided by the number of units. A Procurement Unit Cost is defined as the total procurement cost divided by the number of units to be procured. DOD sometimes uses the term Average Procurement Unit Cost (APUC) instead of Program Unit Cost, which is the term used in the statute.

The PAUC is an effort to track cost growth at a program level whereas the PUC is an effort to track cost growth at the per-unit level.

What Is a Current Baseline Estimate and an Original Baseline Estimate?

According to Title 10 of the U.S. Code, DOD is required to establish a baseline description of all MDAPs when the program is officially started. This baseline description includes information on the program's planned cost, schedule, and performance.7 The cost information is referred to as the "baseline estimate." The baseline description (including the cost estimate) is contained in the Acquisition Program Baseline (APB).8

APBs are required to initiate a program, and can only be revised

- 1. at the milestone reviews or when full rate production begins,9

- 2. if there is a major program restructuring that is fully funded,

- 3. as a result of a program breach, or

- 4. if the program has changed so significantly that the current baseline is impractical to achieve.10

Under current DOD policy, current APBs cannot be revised to avoid a Nunn-McCurdy breach.11

An original baseline estimate is the cost estimate included in the original (first) APB that is prepared prior to the program entering "engineering and manufacturing development" (also known as "Milestone B"), or at program initiation12, whichever occurs later.13 An original baseline estimate can only be revised if the program has a critical Nunn-McCurdy breach.14

A current baseline estimate is the baseline estimate that is included in the most recently revised APB. If the original baseline estimate has never been revised, the original baseline estimate is also the current baseline estimate.

How Many Nunn-McCurdy Breaches Have There Been?

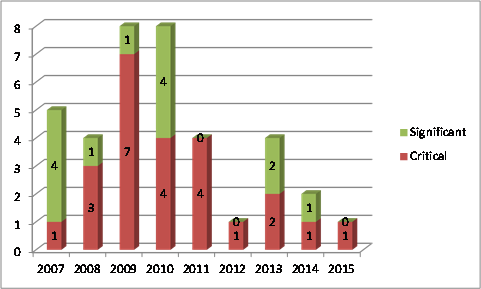

In June 2015, DOD released a formal list of all Nunn-McCurdy breaches since 1997 (see Appendix A). According to DOD, from 2007-2015 there have been 37 total Nunn-McCurdy breaches: 13 significant breaches and 24 critical breaches (see Figure 1).

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of DOD data. Notes: For a discussion on the methodology used to determine breaches, see Appendix A. |

At What Point in the Acquisition Process do Breaches Occur?15

Generally, there are three phases in the acquisition process:

- 1. Technology Maturation & Risk Reduction (Milestone A to Milestone B),

- 2. Engineering & Manufacturing Development (EMD-Milestone B to Milestone C), and

- 3. Production & Deployment (Post-Milestone C).16

Historically, most cost growth occurs during the Engineering & Manufacturing Development Phase.17 However, as reflected in Table 2, more than half of the Nunn-McCurdy breaches occurred in the production phase (post-Milestone C). This can be due in part to a decision during production to cut the number of units procured or to the nature of the Nunn-McCurdy thresholds. Although most of a program's cost growth may occur in the EMD phase, the threshold for total cost growth may not be surpassed until the program is in production.

|

Engineering & Manufacturing Development |

Production |

|

|

2007 |

3 |

2 |

|

2008 |

2 |

2 |

|

2009 |

6 |

2 |

|

2010 |

3 |

5 |

|

2011 |

2 |

2 |

|

2012 |

- |

1 |

|

2013 |

1 |

3 |

|

2014 |

- |

2 |

|

2015 |

- |

1 |

|

Total |

17 |

20 |

Source: CRS analysis using published SAR data and the official DOD Nunn-McCurdy Breach list.

Why Have There Been Fewer Breaches in Recent Years?

The number of Nunn-McCurdy breaches have decreased in recent years, dropping from an average of six breaches annually from 2007-2010, to just two breaches from 2011-2015 (see Figure 1). There is much debate as to why this is happening. It may be the result of a unique confluence of a factors, which may include18

- constrained budgets,

- improved cost estimating (influenced by the Weapon System Acquisition Reform Act of 2009),

- fewer new starts,

- the cancellation or curtailment in recent years of troubled programs,

- the impact of a generation of acquisition professionals who rose through the system under the Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act, and

- the continuity and consistency of actions taken by the office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (AT&L).

This trend is consistent with recent DOD data that seems to indicate that MDAPs are experiencing less cost growth.19 As one analyst argued, a combination of recent statutory, regulatory, and cultural changes "have had profoundly positive influences on acquisition program results."20 Regarding culture, some analysts have argued that the frequent leadership turnover at AT&L allowed military services to wait out new initiatives until a new AT&L leadership was put in place.21 Under Secretary Frank Kendall and his team are the longest serving AT&L leadership since the position was created. And his predecessor, Ashton Carter, is the current Secretary of Defense.22 This continuity of leadership and consistency of policies could be having an effect on the culture of the acquisition workforce.

It remains to be seen if this trend of less cost growth will continue if the Budget Control Act expires,23 a new administration takes over, and new acquisition programs get underway, including the next-generation bomber and the Ohio‐class submarine replacement program.

How Does the Nunn-McCurdy Act Operate?

Nunn-McCurdy Timelines

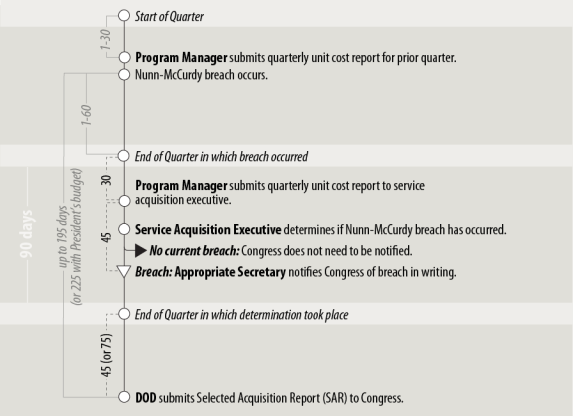

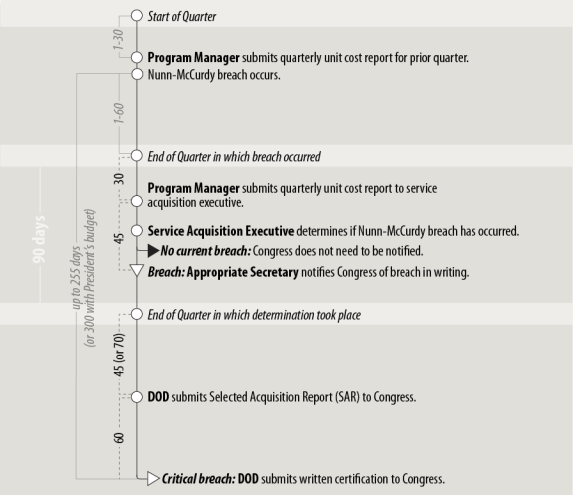

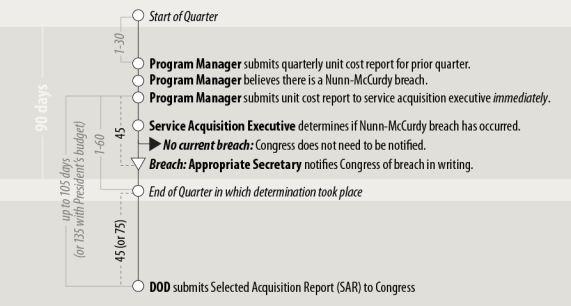

Program managers are required to submit quarterly unit cost reports to the service's acquisition executive within 30 days of the end of the quarter.24 If a program manager has reasonable cause to believe that a program has a significant Nunn-McCurdy breach, they must immediately submit a unit cost report.25 This report is generally the first official indication that a program may have a Nunn-McCurdy breach.26

When a service acquisition executive receives a unit cost report, they must determine whether a Nunn-McCurdy breach has occurred. If the service acquisition executive determines that there was a breach:

- and the determination is based on a quarterly unit cost report, the notification to Congress must be submitted within 45 days of the end of the quarter (see Figure 2).27

- and the determination is based on a unit cost report submitted in the middle of a quarter, then the written notification to Congress must be submitted within 45 days of when the program manager submitted the unit cost report to the service acquisition executive (see Figure 3).

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of 10 U.S.C. §2433. Notes: Assumes that a Nunn-McCurdy breach does not occur within the first 30 days of the quarter, when the prior quarter's unit cost report has not yet been filed. A SAR must be submitted within 45 days from the end of a quarter except for the first fiscal quarter, when the SAR must be submitted within 45 days from the time when the President submits the budget to Congress (10 U.S.C. §2432(f)). The President's budget is generally submitted the first week of February. For purposes of this figure, it is assumed that the President's budget is submitted 30 days after the end of the quarter. |

The notification to Congress must include 17 different data elements, including

- 1. an explanation of the reasons for the cost increase,

- 2. the completion status of the program and designated major subprograms,

- 3. changes in the projected cost of the program,

- 4. names of the military and civilian personnel responsible for program management and cost control,

- 5. any changes in performance or schedule that contributed to cost growth,

- 6. action taken and proposed to be taken to control cost growth,

- 7. changes in the performance or schedule milestones and how such changes have affected the cost of the program, and

- 8. prior cost estimating information.28

In addition to the notification, DOD must also submit to Congress a Selected Acquisition Report for the fiscal quarter in which the breach occurred or in the quarter in which it was determined that a breach occurred.29 For a significant breach, no further action is required. However, if a program experiences a critical breach, DOD is required to take a number of additional steps.

Consequences of a Critical Nunn-McCurdy Breach

In the event of a critical breach, the Secretary of Defense is required to conduct a root-cause analysis to determine what factors caused the cost growth that led to a critical breach, and, in consultation with the Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation, assess

- 1. the estimated cost of the program if no changes are made to the current requirements,

- 2. the estimated cost of the program if requirements are modified,

- 3. the estimated cost of reasonable alternatives to the program, and

- 4. the extent to which funding from other programs will need to be cut to cover the cost growth of this program.30

After the reassessment, the program must be terminated unless the Secretary of Defense certifies in writing no later than 60 days after a SAR is provided to Congress that the program will not be terminated because it meets certain requirements.31 A certification, which uses the exact wording as found in 10 U.S.C. Section 2433a(b), certifies that

- 1. the program is essential to national security,

- 2. the new cost estimates have been determined by the Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation to be reasonable,

- 3. the program is a higher priority than programs whose funding will be reduced to cover the increased cost of this program, and

- 4. the management structure is sufficient to control additional cost growth.32

A certification must be accompanied by a copy of the root-cause analysis report.33 A program that is not terminated must

- 1. be restructured in a manner that addresses the root cause of the cost growth,

- 2. have its prior milestone approval rescinded, and

- 3. receive a new milestone approval before taking any contract action—including signing new contracts or exercising options—without approval from the Milestone Decision Authority.

DOD must also (1) notify Congress of all funding changes made to other programs to cover the cost growth of the program in question and (2) hold regular reviews of the program.34

Quantity-Related Breach Exception to Rescinding Prior Milestone Approval

A Program can have a Nunn-McCurdy breach for reasons that are not related to program management. For example, DOD originally planned to buy 24,000 Small Diameter Bomb Increment I units but cut the order almost in half to 12,600. According to DOD officials, the reduction was based on "updated inventory assessment and usage projection for this weapon." The actual per unit cost of buying each small diameter bomb decreased from $24,000 to $23,000. However, in calculating program acquisition unit costs, Nunn-McCurdy includes fixed development, production, and military construction costs that have already been committed to the program. Cutting the number of units means that these sunk costs are amortized, or spread out, over fewer units, which in this case increased program acquisition unit cost by 17%, triggering a significant breach.35

In the National Defense Authorization Act of 2012, Congress provided an exception to the requirement to rescind milestone approval for programs whose cost growth is due primarily to a strategic decision to change the number of items purchased.36 Under the amended statute, a critical Nunn-McCurdy breach does not have to have its prior milestone approval rescinded if

- 1. but for the change in the number of units being acquired, the program acquisition unit cost or procurement unit cost would not have increased by more than 5% of the current baseline estimate or 10% of the original baseline estimate and

- 2. the change in quantity was not made as a result of increasing costs, a delay in the schedule, or problems with meeting the requirements.

For DOD to invoke this exception, the Secretary of Defense must provide Congress (within 60 days of the SAR being submitted to Congress) a written determination, along with an explanation of the basis for the determination, that

- 1. based on the root-cause analysis, but for the change in the number of units being acquired, the program acquisition unit cost or procurement unit cost would not have increased by more than 5% of the current baseline estimate or 10% of the original baseline estimate and

- 2. the change in quantity was not made as a result of increasing costs, a delay in the schedule, or problems with meeting the requirements.

Timeline for Critical Nunn-McCurdy Breach

As reflected in Figure 4, from the time a program manager reasonably believes that a critical breach occurs to the time the Secretary of Defense certifies the program to Congress could be as long as 255 days (and as long as 285 days if the SAR is filed 45 days after the President's budget).37

How the Nunn-McCurdy Act Has Evolved

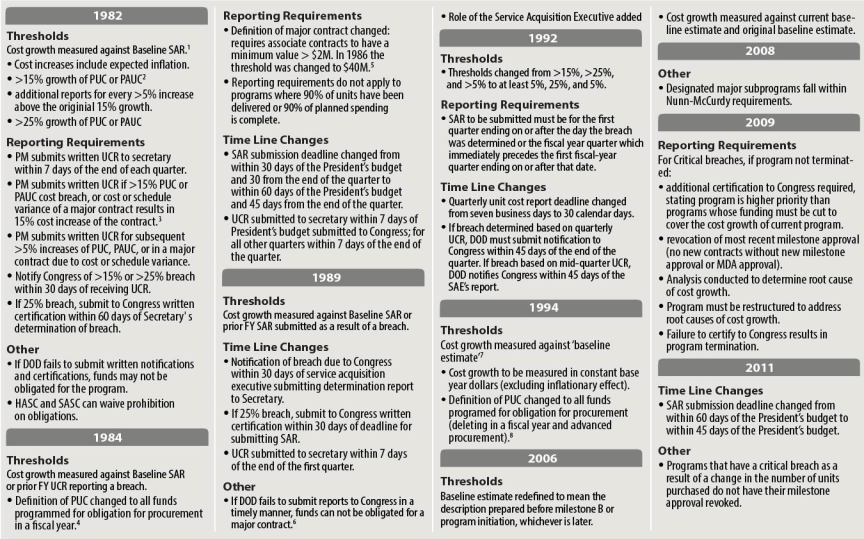

The Nunn-McCurdy Act has been amended nine times over the years (see Figure 5). One of the most significant changes to the reporting requirements occurred in the FY2006 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 109-163), when added the requirement to measure cost growth against an original baseline. The new standard, which prevents DOD from avoiding a Nunn-McCurdy breach by simply re-baselining a program, increased the number of programs breaching Nunn-McCurdy.38 According to DOD, 11 programs that did not have a Nunn-McCurdy breach prior to the new FY2006 requirements were re-categorized as having significant breaches as a result of this legislative change.39 Congress believed that the FY2006 changes to Nunn-McCurdy would help "encourage the Department of Defense both to establish more realistic and achievable cost and performance estimates at the outset of MDAPs and to more aggressively manage MDAPs to avoid undesirable cost growth on these programs."40

Another significant change occurred in the FY2009 Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform (P.L. 111-23), when Congress included a requirement that programs with critical breaches be presumed terminated unless the Secretary of Defense certifies the program. For programs that are certified, DOD must (1) revoke the prior milestone approval, (2) restructure the program, and (3) provide Congress a written explanation of the root-cause of the cost growth. These changes were fueled in part over congressional concerns that programs with chronic cost growth and schedule delays were not being terminated and Congress was not being provided specific information on what was causing the cost growth.

The most recent significant change occurred in the FY2012 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 112-81), when Congress waived the requirement to rescind the milestone approval for programs whose critical cost growth is due primarily to a strategic decision to change the quantity of items purchased.41 There have been no substantive changes to the Nunn-McCurdy Act since the FY2012 NDAA. (For an expanded discussion on the legislative evolution of Nunn-McCurdy, see Appendix B.)

|

Figure 5. Evolution of the Nunn-McCurdy Act 1982-Present |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of legislative history, based on year of enactment. See Appendix B for full citations. Notes: 1 Baseline SAR—First SAR containing program information or comprehensive annual SAR for prior fiscal year. 2 PUC—total procurement funds appropriated in a fiscal year minus advanced procurement appropriated for future years, plus advanced procurement appropriated in prior years for use in the current fiscal year divided by number of units procured with such funds in the same fiscal year; PAUC—total cost of development, procurement, and construction divided by the number of units. 3 Major Contract—each prime contract and the six largest associate contracts measured by dollar value. 4 PUC (1984 definition)—total funds programmed to be available for obligation for procurement for a fiscal year, minus funds programmed to be available in current fiscal year for obligation for advanced procurement in future years, plus advanced procurement appropriated in prior years for use in the current fiscal year, divided by number of units procured with such funds in the same fiscal year. 5 P.L. 99-500 and P.L. 99-591 §101(c). 6 If DOD subsequently submits the SAR report, prohibition ends 30 days after continuous session of Congress. 7 Baseline Estimate—DOD required to develop a baseline description for MDAPs that includes a cost estimate. The description must be prepared before major milestones. 8 PUC (1994 definition)—total funds programmed to be available for obligation for procurement for the program divided by number of units procured. |

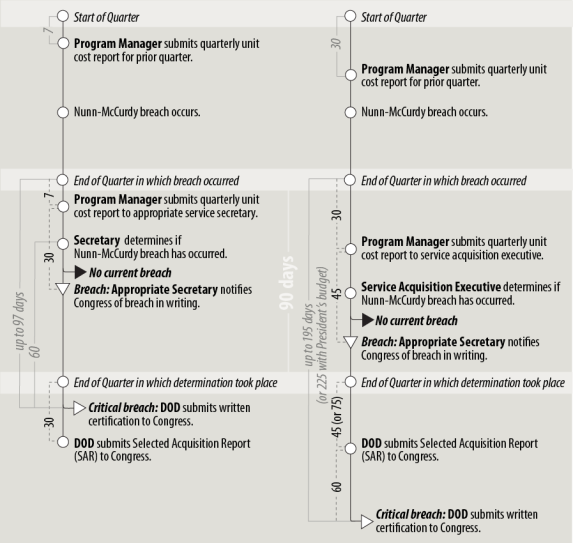

The reporting timelines for Nunn-McCurdy have been amended numerous times since the act was first enacted. In 1983, no more than 97 days could elapse from the end of the quarter in which a critical breach occurred to when the Secretary of Defense certified the program to Congress. Today, it could take as long as 195 days (6.5 months), or 225 days in a quarter when the SAR is filed following the submission of the President's budget (see Figure 6).

Effectiveness of the Nunn-McCurdy Act

The Nunn-McCurdy Act was originally intended to serve as a reporting mechanism. In recent years, Congress has also tried to use the act as a mechanism for managing cost growth.

Nunn-McCurdy as a Reporting Mechanism

Some analysts believe that Nunn-McCurdy has been effective as a reporting mechanism for informing Congress of cost overruns in MDAPs. As discussed above, Congress is

- 1. notified when the cost of a program increases beyond established thresholds and

- 2. provided with additional information on such programs (i.e., Selected Acquisition Reports or root-cause analysis reports).42

As a result of the Nunn-McCurdy process, Congress has substantial visibility into the cost performance of the acquisition stage of MDAPs that experience certain levels of cost growth. To the extent that Nunn-McCurdy increases visibility into—and an understanding of what causes—cost growth, the act can help efforts to improve weapon system acquisitions.

However, some analysts suggest that Nunn-McCurdy is not a sufficiently comprehensive reporting mechanism because program managers can sometimes take steps to avoid informing Congress of cost growth. For example, according to a media report, the Marine Corps AH-1Z attack helicopter program reduced the number of helicopters it planned to buy in order to lower the overall program cost and avoid a breach.43 The program manager reportedly stated that the program reduced its planned purchase from 105 to 58 helicopters "to avoid a critical Nunn-McCurdy breach."44 Reducing the planned purchase to avoid reporting cost growth to Congress could deprive Congress of information that it needs to make budgetary decisions.

Nunn-McCurdy Does Not Require Reporting on Operations and Support (O&S) Costs

Some analysts suggest that Nunn-McCurdy is not a sufficiently comprehensive reporting mechanism because it does not apply to all elements of a weapon system's life-cycle costs, such as operations, support, or disposal.45 Analysts have estimated that O&S costs account for two-thirds or more of a system's total life-cycle cost.46

Many of the decisions that determine O&S costs are made early in the acquisition process, prior to significant O&S costs being incurred. Because O&S costs are not incurred until much later in the life cycle, these costs may not always receive the same attention as acquisition costs at Milestone B and Milestone C. Decisions made at these key decision points could result in lower acquisition costs at the expense of higher long term O&S costs—and ultimately higher overall life-cycle costs.

Without good data on O&S costs, DOD and Congress may not have important information upon which to make budget decisions. While gathering O&S data may not help manage costs for fielded systems, the data can be used to gauge the reliability of DOD O&S cost estimates for future programs. Such data can also give Congress insight into the impact of trade-offs that are being made during the acquisition process that affect both short-term and long-term cost.

Nunn-McCurdy as a Mechanism for Controlling Cost Growth

Some analysts and government officials have sought to use Nunn-McCurdy as a vehicle to manage MDAPs, with one analyst reportedly arguing for a "Nunn-McCurdy on steroids that really punishes programs that have failed."47 Others have argued that while Nunn-McCurdy is a good reporting mechanism, it is not set up to be an effective program management tool. While recent data appear to indicate that cost growth in MDAPs have decreased in recent years; few analysts attribute the trend to the Nunn-McCurdy Act itself.48

While Congress has been active in pursuing acquisition reform in recent years, there has been little effort to try to use the Nunn-McCurdy Act as a mechanism to manage cost growth in MDAPs.

Have Critical Nunn-McCurdy Breaches Led to Program Cancellations?

Generally, a Nunn-McCurdy breach does not result in a program being cancelled. However, there have been some exceptions. In December 2001, the Navy Area Defense (NAD) program was cancelled.49 According to DOD, "the cancellation came, in part, as a result of a Nunn-McCurdy Selected Acquisition Report breach of the existing program."50 This was the first acquisition program that analysts and officials recalled having been cancelled as a result of a Nunn-McCurdy breach.51

In July 2008, Congress was notified that the Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter (ARH) program had suffered a critical Nunn-McCurdy breach. Shortly thereafter, John Young, then Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, in consultation with senior Army officials, cancelled the ARH program. Secretary of the Army Pete Geren justified the cancellation, stating "The cost and schedule that were the focus of the decision to award the contract to Bell Helicopter are no longer valid. We have a duty to the Army and the taxpayer to move ahead with an alternative course of action to meet this critical capability for our soldiers at the best price and as soon as possible."52

In the Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act of 2009, Congress amended the Nunn-McCurdy Act, stating that there is a "presumption of termination" for programs that experience a critical breach.53 According to the statute, "the Secretary shall terminate the program unless the Secretary" submits a certification to Congress. Since then, two programs (VH-71 and Joint Tactical Radio System-Ground Mobile Radios) were terminated following a Nunn-McCurdy critical breach.

Case Study: Unrealistic Cost Estimates as a Root Cause of Cost Growth that Leads to Nunn-McCurdy Breaches

While there are a number of factors that lead to cost growth in MDAPs, for some 30 years, various DOD officials, analysts, and industry officials have argued that a primary cause of cost growth is unrealistically low cost estimates at the inception of programs.54 Unrealistically optimistic cost estimates can make future cost growth almost inevitable, setting the stage for future Nunn-McCurdy breaches.55 In 2006, Gary Payton, Air Force Deputy Under Secretary for Space Programs, made a direct link between unrealistically optimistic estimates and Nunn-McCurdy breaches. In a presentation entitled Nunn-McCurdys Aren't Fun, he argued that "Unbridled optimism regarding cost, schedule, performance, and risks is a recipe for failure."56 As set forth in the presentation,

Understated costs leads to lower budget → leads to industry bidding price less than budget → leads to lower award price → leads to government repeatedly changing scope, schedule, budget profile → leads to five to ten years later recognition "real" cost multiple of bid → leads to Nunn-McCurdy Breach.

Given the connection between unrealistic cost estimates and Nunn-McCurdy breaches, more realistic cost estimates could be a factor in having fewer programs breach the Nunn-McCurdy thresholds.

Applying Nunn-McCurdy to Other Agencies

Because of the perceived effectiveness of Nunn-McCurdy, there have been proposals to apply the Nunn-McCurdy approach to other types of acquisitions or other agencies.57 While some of these efforts have failed,58 the Intelligence Authorization Act for FY2010 (P.L. 111-259) includes provisions that are substantially similar to the Nunn-McCurdy Act. Sections 323 (Reports on the Acquisition of Major Systems) and 324 (Critical Cost Growth in Major Systems) outline the reporting requirements for major intelligence programs whose total acquisition costs have grown 15% or 25% above the baseline estimate. According to a Senate report, "Section 324 is intended to mirror the Nunn-McCurdy provision in Title 10 of the United States Code that applies to major defense acquisition programs."59

More recently, in October 2015, the House passed the Department of Homeland Security Headquarters Reform and Improvement Act of 2015 (H.R. 3572) which, among other reforms, would implement a Nunn-McCurdy-type approach for DHS acquisitions. Included in the bill are notifications to Congress for major DHS acquisition programs that exceed 15% and 20% cost growth or 180 days and 365 days schedule slip.60

Issues for Congress

Nunn-McCurdy as a Reporting and Management Tool

One issue for Congress is to determine whether Nunn-McCurdy should be used as

- 1. only a reporting mechanism to provide information on cost growth to Congress or

- 2. both a reporting and management tool.

Congress appears to have used Nunn-McCurdy as both a reporting and a management tool. To enhance the effectiveness of the act as a reporting tool, Congress has amended it over the last 25 years to increase visibility into MDAP cost growth and improve the reliability of the data reported. For example, as discussed above, in the FY2006 National Defense Authorization Act, Congress added an additional threshold against which to measure cost growth to improve visibility into the cost growth experienced by a program from its inception.

At the same time, Congress has taken actions which imply that Nunn-McCurdy is also a management tool. For example, in the Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act of 2009, Congress mandated that a program that has a critical breach must be restructured to address the root causes of cost growth and have its most recent milestone approval revoked.

Clarifying what role Nunn-McCurdy should play in helping Congress exercise its oversight role could help Congress determine how best to amend the act in the future.

Designating Individual Ships in Carrier Programs as Major Subprograms for Purposes of Nunn-McCurdy Reporting

The first two ships in the Ford-class nuclear-powered aircraft carrier program, the Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) and John F. Kennedy (CVN-79), have estimated procurement cost growth of 22.9% and 24.0%, respectively (since the submission of the FY2008 budget).61 Because each ship is part of a larger multi-ship acquisition program, the full program has not breached the Nunn-McCurdy thresholds. Given that aircraft carriers are estimated to cost on average in excess of $11.5 billion,62 Congress may consider designating individual carrier procurement efforts as major subprograms for purposes of Nunn-McCurdy reporting requirements.

In the FY2012 NDAA,63 Congress took a similar approach with the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle, when it required the Secretary of Defense to either

- redesignate the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle program as a major defense acquisition program not in the sustainment phase under section 2430 of title 10, United States Code; or

- provide Congress with the information that would have been statutorily required if EELV were designated as a major defense acquisition program not in the sustainment phase, as it relates to

- cost, schedule, and performance;

- Select Acquisition Reports, including updated program life-cycle cost estimates; and

- unit cost reports.

Shortening the Nunn-McCurdy Timeline

Some analysts have argued that under the current statute, too much time elapses from when a critical breach is first identified to when the Secretary of Defense certifies the program to Congress. According to these analysts, the Nunn-McCurdy timelines often span two budget cycles, and in some cases can exceed 300 days from when a program manager accurately suspects that a critical Nunn-McCurdy breach has taken place Figure 6. One option for Congress could be to consider shortening some of the Nunn-McCurdy timeframes. Condensing the timeframes could give Congress a greater opportunity to consider budgeting options for troubled programs.

Some analysts have gone further, arguing that the time it takes to report a breach to Congress could be shortened by notifying Congress when a Unit Cost Report or when a Contract Performance Report (which is used in Earned Value Management) indicates that a program has breached a Nunn-McCurdy threshold.64

However, according to DOD, "The timing of breach determinations is one of the most difficult parts of Nunn-McCurdy." Within the department, there is a great deal of discussion and deliberation at all levels prior to the formal breach determination and notification to Congress. Initial breach indications from the contractor or program manager could be premature. For example, even if the program manager has reasonable cause to believe there is a Nunn-McCurdy breach, senior leadership could initiate cost reductions or descope the program.65 Using the Unit Cost Reports or Contractor Performance Reports to determine a Nunn-McCurdy breach could deprive DOD of the opportunity to manage programs and take steps to rein in cost growth.

Applying Nunn-McCurdy-Type Reporting Requirements to O&S Costs

Given the costs associated with operations and support, Congress may consider applying Nunn-McCurdy-type reporting requirements to O&S costs. Applying a reporting requirement to O&S costs might help Congress set its budgetary priorities, as well as gather and track cost data for future analysis. Another option for Congress could be to require the Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation office to include in its annual report to Congress a comparison of original O&S cost estimates to current actual costs (adjusted for inflation) for ongoing programs. The extent to which these options may be viable depends on the reliability of the data available.

Appendix A. Data on Nunn-McCurdy Breaches

|

Year |

Critical Breach |

Significant Breach |

|

2007 |

|

|

|

2008 |

|

|

|

2009 |

|

|

|

2010 |

|

|

|

2011 |

|

— |

|

2012 |

|

— |

|

2013 |

|

|

|

2014 |

|

|

|

2015 |

|

|

Source: Department of Defense, June 9, 2015.

Notes:

a. DOD did not submit a December 2008 Annual SAR to Congress. As a result, the VH-71 breach was incorporated into the March 2009 SAR even though the breach occurred in the 2008 reporting period.

b. This program was originally classified as having a significant breach, and shortly thereafter reclassified as having had a critical breach. The reclassification accounts for the discrepancy between this table and the GAO report GAO-11-295R (discussed below).

c. The September 2010 SAR indicated a significant breach for this program. The office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation determined that the program had a critical breach, not a significant breach, as reported to Congress. Information on the critical breach was subsequently included in the December 2010 SAR. The significant breach notification is not included in the above list because for purposes of this analysis, CRS deems the December SAR as a correction of the record, akin to an errata sheet.

d. In section 838 of the FY2012 NDAA, Congress designated EELV as an MDAP, triggering a Nunn-McCurdy breach.

Selected Acquisition Reports are not reliable sources for analyzing Nunn-McCurdy breaches. In some instances, SAR data is subsequently amended. For example, Chemical Demilitarization-Assembled Chemical Weapons Alternatives (Chem Demil-ACWA) was reported to Congress in the September 2010 SAR as a significant breach, prompting then USD (AT&L) Ashton Carter to direct CAPE to examine the program. CAPE determined that the program had a critical breach, not a significant breach, as reported to Congress. Information on the critical breach was subsequently included in the December 2010 SAR. The significant breach notification is not included in Table A-1 because for purposes of this analysis, CRS deems the December SAR as a correction of the record, akin to an errata sheet, and not a result of a second breach.

In other instances, SAR data does not accurately reflect the timing of Nunn-McCurdy breaches. For example, DOD did not submit a SAR in December 2008. As a result, the VH-71 breach that would have been reported in a December 2008 SAR was reported in the March 2009 SAR. For purposes of this analysis, CRS is categorizing VH-71 based on when the breach occurred (2008) and not on when the SAR was sent to Congress.

In its 2013 Annual Report: Performance of the Defense Acquisition System, DOD published data on the number of programs that had Nunn-McCurdy breaches. However, this data was derived from the SARs and therefore does not contain the most comprehensive and up-to-date information.

In 2011, the Government Accountability Office published the report Trends in Nunn-McCurdy Cost Breaches for Major Defense Acquisition Programs,66 which contained data on the number of programs that had Nunn-McCurdy breaches. The data contained in the GAO report was the most comprehensive at the time. Subsequent to GAO's audit work, program data was restated. As a result, the GAO list does not include updated or restated data.

Appendix B. Legislative History

On September 8, 1982, President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Department of Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1983 (P.L. 97-252), which included what has come to be known as the Nunn-McCurdy Act.67 This Appendix traces the most significant changes to the Nunn-McCurdy Act.

Department of Defense Authorization Act, 1982

(P.L. 97-86)

Antecedents of the Nunn-McCurdy Act

On May 14, 1981, Senator Sam Nunn offered a floor amendment to the Department of Defense Authorization Act of 1982 requiring DOD to notify Congress if the cost growth of an MDAP (referred to in the amendment as a major defense system) exceeded certain thresholds.68 The purpose of the measure was to "help control the increasing costs of major defense systems."69 In arguing for the amendment, Senator Nunn raised a number of issues, including the need to ensure that DOD's "spending priorities are being established within the context of a coherent national strategy." He argued that "the unit costs of major defense weapon systems are increasing at rates far beyond the rate of inflation, adding billions to the budget just to buy the same quantities of weapons that were planned before."70 Senator Nunn believed that the amendment "holds the appropriate Pentagon officials and defense contractors publicly accountable and responsible for managing costs."71 But ultimately, the amendment was intended to inform Congress whether DOD's acquisition process is working effectively. In arguing in support of the amendment, Senator Nunn concluded

If the system works, if the cost estimates and the inflation estimates are anywhere near accurate, giving a 15% margin on R. & D., a 10% margin on inflation in the procurement accounts, then the reports will not be necessary. If the system does not work, then, of course, we should know and we should be alerted.

Despite initial opposition by Senator John Tower,72 then chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, the amendment passed by a vote of 94-0 and was included in the Department of Defense Authorization Act of 1982.73

As shown in Table B-1, the thresholds set forth in the 1982 act were similar to the significant and critical breach levels that exist in the Nunn-McCurdy Act today (the original statute did not use the terms significant or critical breach; these terms are used below for comparison with the current statute). According to the act, a significant breach occurred when the Program Acquisition Unit Cost (PAUC—total cost of development, procurement, and construction divided by the number of units) or the Procurement Unit Cost (PUC—total procurement funds appropriated in a fiscal year divided by the number of end units to be procured with such funds in the same fiscal year) for an MDAP increased by more than 15%. A "critical" breach occurs when the PAUC or PUC increased by more than 25%. Inflation costs were included in the cost growth analysis.

|

Significant Breach |

Critical Breach |

|

|

UAC or PAUC |

> 15% |

>25% |

Source: P.L. 97-86 Section 917.

Under the act, a program manager was required to submit a quarterly unit cost report to the appropriate secretary within seven days of the end of the quarter. However if a program manager had "reasonable cause" to believe that a program had a breach, the program manager was required to immediately submit a report to the service secretary concerned. If the secretary concerned determined that a breach had occurred, he had to "promptly" notify Congress of the breach in writing and submit a written report to Congress within 30 days that included

- 1. an explanation of the reasons for the cost increase,

- 2. the names of the military and civilian personnel responsible for program management and cost control,

- 3. action taken and proposed to control future cost increases,

- 4. any changes in performance or schedule that contributed to cost growth,

- 5. the identities of the principal contractors, and

- 6. an index of all testimony and documents previously provided to Congress on the program's estimated costs.

If the secretary concerned determined that a critical breach had occurred, in addition to the above requirements, the secretary had to certify to Congress in writing within 60 days of the determination that

- 1. the program was essential to national security,

- 2. there was no viable cost effective alternative to the program,

- 3. the new cost estimate was reasonable, and

- 4. the management structure was sufficient to control additional cost growth.

If the secretary did not submit the 30- or 60-day reports in a timely manner, then no additional funds were allowed to be obligated for the program. The statute only applied to programs with cost overruns that occurred in FY1982.

Department of Defense Authorization Act, 1983

(P.L. 97-86)

Passage of the Nunn-McCurdy Act

In 1981, Representative Dave McCurdy, then chairman of the House Armed Services Committee Special Panel on Defense Procurement Procedures, held a series of hearings examining weapon system cost growth.74 According to Representative McCurdy, the intent of the panel was "to identify and recommend a method which will allow the Congress to more effectively review and evaluate cost categories for major weapons systems."75

Subsequently, Senator Nunn and Representative McCurdy led an effort to permanently enact the reporting requirements established in the FY1982 Defense Authorization Act. In the Department of Defense Authorization Act of 1983 (96 Stat. 718), Congress passed a modified version of the FY1982 reporting requirements. On September 8, 1982, President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Department of Defense Authorization Act, 1983 (P.L. 97-252), which included what has come to be known as the Nunn-McCurdy Act.

Statutory Structure of the FY1983 Nunn-McCurdy Act

The Nunn-McCurdy Act made a number of modifications to the reporting requirements that were included in the FY1982 act.

Definition of Program Acquisition Unit Cost and Procurement Unit Cost

The Nunn-McCurdy Act changed the definition of PUC to mean (changes in italics) total procurement funds appropriated in a fiscal year minus advanced procurement funds appropriated that year for use in future fiscal years, plus advanced procurement funds appropriated in prior years for use in the current fiscal year divided by the number of end units to be procured with such funds in the same fiscal year.76 PAUC continued to be defined as the total cost of development, procurement, and construction divided by the number of units.

Thresholds

The Nunn-McCurdy Act established the baseline for measuring cost growth as the "baseline selected acquisition report," defined as the Selected Acquisition Report in which information on the program is first included or the comprehensive annual Selected Acquisition Report for the prior fiscal year, whichever is later.77

The thresholds remained unchanged from the original Nunn Amendment of the FY1982 authorization act (the terms "significant" and "critical" breach were not included in the statute but are used below for comparison with the current statute). Unlike the current Nunn-McCurdy statute, the original act included inflation in determining if a breach had occurred.78

|

Significant Breach |

Critical Breach |

|

|

UAC or PAUC |

> 15% |

>25% |

Source: 10 U.S.C. §139b(d)(1),(2), 1982.

Reporting

Under the act, a program manager was required to submit a written quarterly unit cost reports to the appropriate secretary within seven days of the end of each quarter.79 However if a program manager had "reasonable cause" to believe that a program had a breach, the program manager was required to immediately submit a report to the secretary concerned.80 The program manager was also required to submit a unit cost report if a cost or schedule variance of a major contract under the program resulted in more than 15% cost growth compared to the date the contract was signed.81 After a breach occurred, if the program subsequently experienced additional cost growth of more than 5% in PUC or APUC, or additional cost growth of a major contract of at least 5% (due to cost or schedule variance), then the program manager was required to submit an additional unit cost report.82

The FY1983 NDAA changed some of the information required for the 30-day report to Congress, removing the requirement to provide an index of all testimony and documents previously provided to Congress on the program's estimated costs and adding a number of other requirements, including

- 1. cost and schedule variance information,

- 2. changes to the performance or schedule milestones of the program that have contributed to cost growth, and

- 3. prior cost estimating information.

Timelines

The service secretary was required to review the unit cost reports and determine whether there was a breach. If the secretary determined that a breach occurred, he was required to notify Congress of the breach in writing and submit a written report to Congress within 30 days of the unit cost report being submitted to him (the FY1982 act required the secretary to "promptly" notify Congress of the determination).83

If the secretary did not submit the 30- or 60-day report in a timely manner, then additional funds could not be obligated for the program. The funding prohibition could be waived by consent of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees.

FY1985 Department of Defense Authorization Act

(P.L. 98-525)

Definition of Procurement Unit Cost and Major Contract

The FY1985 Department of Defense Authorization Act changed the meaning of procurement unit cost to mean total funds programmed to be available for obligation for procurement for a fiscal year, minus funds programmed to be available in the current fiscal year for obligation for advanced procurement in future years, plus advanced procurement appropriated in prior years for use in the current fiscal, divided by number of units procured with such funds in the same fiscal year.84

The authorization act also changed the definition of a major contract (changes in italics) to mean each prime contract and each of the six largest associate contracts (including for government-furnished equipment) that is in excess of $2,000,000.85 In 1986 the threshold was changed to $40 million.86

Reporting Requirements

Prior to the FY1985 Authorization Act, SARs did not need to include a status report for an MDAP for the second, third, and fourth fiscal quarters if such a report was included in a previous SAR for that fiscal year and there were no changes in program cost, performance, or schedule. The FY1985 act changed the standard, stating that a SAR did not need to include a status report if there was less than a 5% change in the total program cost and less than a three-month delay in the milestone schedule as shown in a previous SAR for the same fiscal year.87

The act also added that reporting requirements under Nunn-McCurdy do not apply to a program that has delivered 90% of the end units or expended 90% of planned expenditures.88

The baseline against which to measure a breach was amended slightly (changes in italics) to be the baseline SAR submitted in the previous fiscal year, or if there was a breach in the previous fiscal year, the unit cost report that reported the breach.89

Timeline Changes

The FY1985 act changed the timeline for requiring the submission of a SAR to Congress. Previously, SARs had to be submitted to Congress within 30 days of when the President submitted the budget to Congress and within 30 days after the end of the quarter for all other quarters. The act extended the SAR submission date to within 60 days after the President sends the budget to Congress and 45 after the end of all other quarters.90 The act also changed the deadline by which a program manager must submit a unit for the first quarter of a fiscal year from within seven days of the end of the quarter to within seven days of the submission of the President's budget.91

FY1990 and 1991 National Defense Authorization Act

(P.L. 101-189)

The FY1990 and 1991 NDAA added the role of the Service Acquisition Executive to the Nunn-McCurdy Act. Under Title X, as amended, the program manager submits unit cost reports to the Service Acquisition Executive, who then determines whether a Nunn-McCurdy breach has taken place. A determination of a breach by the service acquisition executive is sent to the secretary concerned for a further determination.92

Reporting Requirements

The FY1990 and 1991 act amended Section 2432 of Title X to state that a SAR did not need to include a status report if there was less than a 15% increase in program acquisition unit cost and current acquisition unit cost as shown in a previous SAR for the same fiscal year.93 Previously, a SAR had to include a status report if there was a 5% change in the total program cost.

The baseline against which to measure a breach was amended slightly (changes in italics) to be the baseline SAR submitted in the previous fiscal year, or if there was a breach in the previous fiscal year, the SAR submitted to Congress in connection with the breach.94

The other significant change to Nunn-McCurdy in the act is the consequence of DOD failing to submit a SAR for a 15% breach or a certification for a 25% breach. Previously, if DOD failed to provide the required reports in a timely manner, no funds could be obligated for the program unless the House and Senate Armed Services Committees waived the funding prohibition. The act changed the penalty, stating that if the required reports are not filed in a timely manner, appropriated funds could not be obligated for construction, RDT&E, and procurement for a major contract under the program. However, once DOD submits the required reports, the prohibition ends at the end of 30 days of continuous session of Congress.95

Timeline Changes

The act changed the deadline by which a program manager must submit a unit cost report for the first quarter of a fiscal year from within seven days of the submission of the President's budget to within seven days of the end of the quarter.96 The act also changed the timeline for the secretary to submit notifications and certifications to Congress. Specifically, the Secretary must submit a notification of a breach to Congress within 30 days of the service acquisition executive submitting his determination report to the Secretary.97 For a 25% breach, DOD must submit the written certification to Congress within 30 days of the deadline for submitting the SAR.98

FY1993 National Defense Authorization Act

(P.L. 102-484)

Threshold Changes

In the FY1993 NDAA, Congress slightly modified the Nunn-McCurdy thresholds from more than 15% and 25% to at least 15% and at least 25%.99

Reporting Requirements

When a program breaches the Nunn-McCurdy thresholds, DOD is required to submit a SAR to Congress. The FY1993 NDAA provided some flexibility to this requirement (changes in italics), stating that a SAR shall be submitted to Congress for the quarter in which the determination is made that a breach occurred, or for the quarter which immediately precedes the quarter in which the determination is made.100 This added flexibility means that if a program has a breach in one quarter but the determination that a breach occurred does not happen until the next quarter, the Secretary can submit a SAR for either quarter.

Timeline Changes

The FY1993 NDAA changed the deadline for the program manager submitting a quarterly unit cost report to the service acquisition executive from seven business days to 30 calendar days after the end of the quarter.101 In addition, the act changed the timeline for notifying Congress of a breach if the breach was determined based on a quarterly unit cost report. Previously, the Secretary had to notify Congress of a breach within 30 days of the service acquisition executive reporting his determination to the secretary. Under the amended statute, the secretary must notify Congress within 45 days of the end of the quarter in which the breach took place.102

Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act of 1994

(P.L. 103-355)

Definition of Procurement Unit Cost and Baseline Estimate

The Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act of 1994 (FASA) changed the definition of Procurement Unit Cost to mean total funds programmed to be available for obligation for procurement for the program divided by number of units procured.103 FASA also changed the benchmark against which cost growth is to be measured. FASA required the Secretary of the department managing an MDAP to develop a baseline description for the program.104 The description must include a cost estimate. The baseline description must be prepared prior to each major milestone.105

Threshold Changes

FASA changed the way cost growth is measured, stating that cost growth should be measured in constant base year dollars, thereby excluding inflation as a factor for calculating cost growth.106

FY2006 National Defense Authorization Act

(P.L. 109-163)

The FY2006 National Defense Authorization Act amended Nunn-McCurdy to include the original baseline estimate as a standard against which to measure cost growth.107 The FY2006 NDAA also introduced the terms significant and critical cost growth that are used in the current Nunn-McCurdy Act. The new standard was intended to prevent DOD from avoiding a Nunn-McCurdy breach by simply re-baselining a program. Congress believed that these changes to Nunn-McCurdy would help "encourage the Department of Defense both to establish more realistic and achievable cost and performance estimates at the outset of MDAPs and to more aggressively manage MDAPs to avoid undesirable cost growth on these programs."108

The introduction of the original baseline threshold increased the number of programs triggering a reporting requirement to Congress. For example, according to DOD, 11 programs that did not have a Nunn-McCurdy breach prior to the new FY2006 requirements were re-categorized as having significant breaches as a result of the FY2006 legislation. The first SAR submitted by DOD after enactment of the FY2006 NDAA contained 36 programs that were in breach of one of the Nunn-McCurdy thresholds.109

FY2007 John Warner National Defense Authorization Act

(P.L. 109-364)

The FY2007 NDAA added to the definition of the baseline estimate, stating that the original baseline estimate is the description established for the program prepared before it enters system development and demonstration (Milestone B) or at program initiation, whichever is later, without adjustment or revision.110

FY2009 Duncan Hunter National Defense Authorization Act

(P.L. 110-417)

The FY2007 NDAA applied Nunn-McCurdy to all major subprograms of MDAPs designated by the Secretary of Defense as major subprograms. To qualify as a major subprogram, an MDAP must have "two or more categories of end items which differ significantly from each other in form and function."111

Weapon System Acquisition Reform Act of 2009

(P.L. 111-23)

This act introduced a number of changes to the Nunn-McCurdy Act, primarily by adding Section 2433a to Title X.112 Pursuant to Section 2433a, whenever a program suffers a critical breach, an analysis must be conducted to determine the root cause of the critical cost growth, as well as an assessment projecting the cost for

- completing the program as is,

- completing the program with modifications to the requirements, and

- alternative systems or capabilities.

The assessment must also include the extent to which funding for other programs needs to be reduced to cover the increased cost of the breaching program.113

According to Section 2433a, the program must be terminated unless the Secretary of Defense submits the required certifications and the root-cause analysis to Congress, including a new certification—that the program is a higher priority than those programs whose funding is reduced to cover the cost increases of the breaching program.114 If the program is not terminated, the program must

- 1. be restructured to address the root causes of cost growth,

- 2. have its most recent milestone approval revoked and have a new approval before entering into a new contract or exercising a contract option (the milestone decision authority can approve necessary contract actions),

- 3. include in the report all funding changes, including reductions in funding in other programs, to cover the cost growth.115

FY2012 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 112-81)

In this act, Congress waived the requirement to rescind the milestone approval for programs whose cost growth is due primarily to a strategic decision to change the quantity of items purchased.116 Under the amended statute, a program experiencing a critical Nunn-McCurdy breach does not have to have its prior milestone approval rescinded if

- 1. but for the change in the number of units being acquired, the program acquisition unit cost or procurement unit cost would not have increased by more than 5% of the current baseline estimate or 10% of the original baseline estimate and

- 2. the change in quantity was not made as a result of increasing costs, a delay in the schedule, or problems with meeting the requirements.

For DOD to invoke this exception, within 60 days of the SAR being submitted to Congress, the Secretary of Defense must submit to Congress a written determination, along with an explanation of the basis for the determination, that

- 1. based on the root-cause analysis, but for the change in the number of units being acquired, the program acquisition unit cost or procurement unit cost would not have increased by more than 5% of the current baseline estimate or 10% of the original baseline estimate and

- 2. the change in quantity was not made as a result of increasing costs, a delay in the schedule, or problems with meeting the requirements.

Timeline Changes

Previously, SARs had to be submitted with 60 days of when the President submitted the budget to Congress. The FY2012 NDAA decreased the time DOD has to submit the SAR to 45 days after the submission of the President's budget.117