Navy Constellation (FFG-62) and FF(X) Class Frigate Programs: Background and Issues for Congress

Changes from May 4, 2020 to June 8, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background

Background and Issues for Congress

Updated June 8, 2020

Congressional Research Service

https://crsreports.congress.gov

R44972

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Summary

The FFG(X) program is a Navy program to build a class of 20 guided-missile frigates (FFGs).

Congress funded the procurement of the first FFG(X) in FY2020 at a cost of $1,281.2 million

(i.e., about $1.3 billion). The Navy’s proposed FY2021 budget requests $1,053.1 million (i.e.,

about $1.1 billion) for the procurement of the second FFG(X). The Navy estimates that

and Issues for Congress

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Navy's Force of Small Surface Combatants (SSCs)

- U.S. Navy Frigates in General

- FFG(X) Program

- Meaning of Designation FFG(X)

- Procurement Quantities and Schedule

- Ship Capabilities, Design, and Crewing

- Procurement Cost

- Acquisition Strategy

- U.S. Content Requirements for Components

- Competing Industry Teams

- Detail Design and Construction (DD&C) Contract

- Contract Award

- Design Selected for FFG(X) Program

- Program Funding

- Issues for Congress

- Potential Impact of COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Situation

- Accuracy of Navy's Estimated Unit Procurement Cost

- Number of FFG(X)s to Procure in FY2021

- Number of FFG(X) Builders

- U.S. Content Requirements

- Required Capabilities and Growth Margin

- Analytical Basis for Desired Ship Capabilities

- Number of VLS Tubes

- Growth Margin

- Technical Risk

- May 2019 GAO Report

- Guaranty vs. Warranty in Construction Contract

- Potential Industrial-Base Impacts of FFG(X) Program

- Legislative Activity for FY2021

- Summary of Congressional Action on FY2021 Funding Request

Figures

Tables

Summary

The FFG(X) program is a Navy program to build a class of 20 guided-missile frigates (FFGs). Congress funded the procurement of the first FFG(X) in FY2020 at a cost of $1,281.2 million (i.e., about $1.3 billion). The Navy's proposed FY2021 budget requests $1,053.1 million (i.e., about $1.1 billion) for the procurement of the second FFG(X). The Navy estimates that subsequent ships in the class will cost roughly $940 million each in then-year dollars.

subsequent ships in the class will cost roughly $940 million each in then-year dollars.

Four industry teams were competing for the FFG(X) program. On April 30, 2020, the Navy

announced that it had awarded the FFG(X) contract to the team led by Fincantieri/Marinette

Marine (F/MM) of Marinette, WI. F/MM was awarded a fixed-price incentive (firm target)

contract for Detail Design and Construction (DD&C) for up to 10 ships in the program—the lead

ship plus nine option ships.

The other three industry teams reportedly competing for the program were led by Austal USA of

Mobile, AL; General Dynamics/Bath Iron Works (GD/BIW) of Bath, ME; and Huntington Ingalls

Industries/Ingalls Shipbuilding (HII/Ingalls) of Pascagoula, MS.

Under the DD&C contact awarded to F/MM, Navy has the option of recompeting the FFG(X)

program after the lead ship (if none of the nine option ships are exercised), after the 10th10th ship (if

all nine of the option ships are exercised), or somewhere in between (if some but not all of the

nine option ships are exercised).

All four competing industry teams were required to submit bids based on an existing ship

design—an approach called the parent-design approach. F/MM'’s design is based on an Italian

frigate design called the FREMM (Fregata Europea Multi-Missione).

As part of its action on the Navy'’s FY2020 budget, Congress passed two legislative provisions

relating to U.S. content requirements for certain components of each FFG(X).

The FFG(X) program presents several potential oversight issues for Congress, including the

following:

-

the potential impact of the COVID-19 (coronavirus) situation on the execution of

-

the accuracy of the Navy

'’s estimated unit procurement cost for the FFG(X), -

whether to fund the procurement in FY2021 of one FFG(X) (the Navy

'’s request), -

whether to build FFG(X)s at a single shipyard at any one time (the Navy

's’s baseline plan), or at two or three shipyards; -

whether the Navy has appropriately defined the required capabilities and growth

-

whether to take any further legislative action regarding U.S. content requirements

- technical risk in the FFG(X) program;

-

the potential industrial-base impacts of the FFG(X) program for shipyards and

programs.

Introduction

This report provides background information and discusses potential issues for Congress

regarding the Navy'’s FFG(X) program, a program to procure a new class of 20 guided-missile

frigates (FFGs). The Navy'’s proposed FY2021 budget requests $1,053.1 million (i.e., about $1.1

billion) for the procurement of the second FFG(X).

The FFG(X) program presents several potential oversight issues for Congress. Congress's ’s

decisions on the program could affect Navy capabilities and funding requirements and the

shipbuilding industrial base.

This report focuses on the FFG(X) program. Other CRS reports discuss the strategic context

within which the FFG(X) program and other Navy acquisition programs may be considered.1

Background

Navy'1

Background

Navy’s Force of Small Surface Combatants (SSCs)

In discussing its force-level goals and 30-year shipbuilding plans, the Navy organizes its surface

combatants into large surface combatants (LSCs), meaning the Navy'’s cruisers and destroyers,

and small surface combatants (SSCs), meaning the Navy'’s frigates, LCSs, mine warfare ships,

and patrol craft.2 2 SSCs are smaller, less capable in some respects, and individually less expensive

to procure, operate, and support than LSCs. SSCs can operate in conjunction with LSCs and other

Navy ships, particularly in higher-threat operating environments, or independently, particularly in

lower-threat operating environments.

In December 2016, the Navy released a goal to achieve and maintain a Navy of 355 ships,

including 52 SSCs, of which 32 are to be LCSs and 20 are to be FFG(X)s. Although patrol craft

are SSCs, they do not count toward the 52-ship SSC force-level goal, because patrol craft are not

considered battle force ships, which are the kind of ships that count toward the quoted size of the

Navy and the Navy'’s force-level goal.3

3

At the end of FY2019 the Navy'’s force of SSCs totaled 30 battle force ships, including 0 frigates,

19 LCSs, and 11 mine warfare ships. Under the Navy'’s FY2020 30-year (FY2020-FY2049)

shipbuilding plan, the SSC force is to grow to 52 ships (34 LCSs and 18 FFG[X]s) by FY2034.

U.S. Navy Frigates in General

In contrast to cruisers and destroyers, which are designed to operate in higher-threat areas,

frigates are generally intended to operate more in lower-threat areas. U.S. Navy frigates perform

many of the same peacetime and wartime missions as U.S. Navy cruisers and destroyers, but

since frigates are intended to do so in lower-threat areas, they are equipped with fewer weapons,

1

See CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by

Ronald O'Rourke; CRS Report R43838, Renewed Great Power Competition: Implications for Defense—Issues for

Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke; and CRS Report R44891, U.S. Role in the World: Background and Issues for

Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke and Michael Moodie.

2

See, for example, CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for

Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

3

For additional discussion of battle force ships, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding

Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Congressional Research Service

1

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

less-capable radars and other systems, and less engineering redundancy and survivability than

cruisers and destroyers.4

4

The most recent class of frigates operated by the Navy was the Oliver Hazard Perry (FFG-7) class (

(Figure 1). A total of 51 FFG-7 class ships were procured between FY1973 and FY1984. The

ships entered service between 1977 and 1989, and were decommissioned between 1994 and 2015.

In their final configuration, FFG-7s were about 455 feet long and had full load displacements of

roughly 3,900 tons to 4,100 tons. (By comparison, the Navy'’s Arleigh Burke [DDG-51] class

destroyers are about 510 feet long and have full load displacements of roughly 9,700

tons.)55 Following their decommissioning, a number of FFG-7 class ships, like certain other

decommissioned U.S. Navy ships, have been transferred to the navies of U.S. allied and partner

countries.

countries.

Figure 1. Oliver Hazard Perry (FFG-7) Class Frigate |

|

Source: Photograph accompanying Dave Werner, |

.

4

Compared to cruisers and destroyers, frigates can be a more cost -effective way to perform missions that do not require

the use of a higher-cost cruiser or destroyer. In the past, the Navy’s combined force of higher -capability, higher-cost

cruisers and destroyers and lower-capability, lower-cost frigates has been referred to as an example of a so -called highlow force mix. High-low mixes have been used by the Navy and the other military services in recent decades as a

means of balancing desires for individual platform capabilit y against desires for platform numbers in a context of

varied missions and finite resources.

Peacetime missions performed by frigates can include, among other things, engagement with allied and partner navies,

maritime security operations (such as anti-piracy operations), and humanitarian assistance and disaster response

(HA/DR) operations. Intended wartime operations of frigates include escorting (i.e., protecting) military supply and

transport ships and civilian cargo ships that are moving through potentially dangerous waters. In support of intended

wartime operations, frigates are designed to conduct anti-air warfare (AAW—aka air defense) operations, anti-surface

warfare (ASuW) operations (meaning operations against enemy surface ships and craft), and ant isubmarine warfare

(ASW) operations. U.S. Navy frigates are designed to operate in larger Navy formations or as solitary ships. Operations

as solitary ships can include the peacetime operations mentioned above.

5

T his is the displacement for the current (Flight III) version of the DDG-51 design.

Congressional Research Service

2

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

FFG(X) Program

FFG(X) Program

Meaning of Designation FFG(X)

In the program designation FFG(X), FF means frigate,6 6 G means guided-missile ship (indicating a

ship equipped with an area-defense anti-air warfare [AAW] system),77 and (X) indicates that the

specific design of the ship has not yet been determined. FFG(X) thus means a guided-missile

frigate whose specific design has not yet been determined.8

8 Procurement Quantities and Schedule

Total Procurement Quantity

The Navy wants to procure 20 FFG(X)s, which in combination with the Navy'’s required total of

32 LCSs would meet the Navy'’s 52-ship SSC force-level goal. Thirty-five (rather than 32) LCSs

were procured through FY2019, but Navy officials have stated that the Navy nevertheless wants

to procure 20 FFG(X)s.

The Navy'’s 355-ship force-level goal is the result of a Force Structure Analysis (FSA) that the

Navy conducted in 2016. The Navy conducts a new or updated FSA every few years, and it is

currently conducting a new FSA that is scheduled to be released sometime during 2020. Navy

officials have stated that this new FSA will likely not reduce the required number of small surface

combatants, and might increase it. Navy officials have also suggested that the Navy in coming

years may shift to a new surface force architecture that will include, among other things, a larger

proportion of small surface combatants.

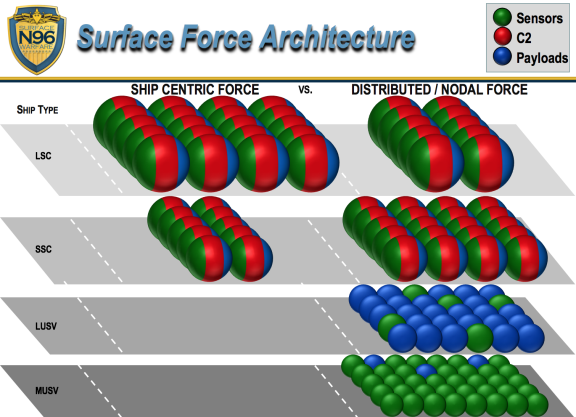

Figure 2 shows a Navy briefing slide depicting the potential new surface force architecture, with

each sphere representing a manned ship or an unmanned surface vehicle (USV). Consistent with

Figure 2, the Navy'’s 355-ship goal, reflecting the current force architecture, calls for a Navy with

twice as many large surface combatants as small surface combatants. Figure 2 suggests that the

potential new surface force architecture could lead to the obverse—a planned force mix that calls

for twice as many small surface combatants than large surface combatants—along with a new

third tier of numerous USVs.9 9 Such a force mix, in theory at least, suggests that the Navy might

increase the total planned number of FFG(X)s from 20 to some higher number.

An April 20, 2020, press report stated (emphasis added):

An internal Office of the Secretary of Defense assessment calls for the Navy to cut two

aircraft carriers from its fleet, freeze the large surface combatant fleet of destroyers and

cruisers around current levels and add dozens of unmanned or lightly manned ships to the

inventory, according to documents obtained by Defense News.

The study calls for a fleet of nine carriers, down from the current fleet of 11, and for 65

unmanned or lightly manned surface vessels. The study calls for a surface force of between

80 and 90 large surface combatants, and an increase in the number of small surface

combatants—between 55 and 70, which is substantially more than the Navy currently

operates.

The assessment is part of an ongoing DoD-wide review of Navy force structure and seem

to echo what Defense Secretary Mark Esper has been saying for months: the Defense

Department wants to begin de-emphasizing aircraft carriers as the centerpiece of the Navy's

Congressional Research Service

4

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

force projection and put more emphasis on unmanned technologies that can be more easily

sacrificed in a conflict and can achieve their missions more affordably….

There are about 90 cruisers and destroyers in the fleet: the study recommended retaining at

least 80 but keeping about as many as the Navy currently operates at the high end.

The Navy'’s small surface combatant program is essentially the 20 littoral combat

ships in commission today, with another 15 under contract, as well as the 20 next-generationnextgeneration frigates, which would get to the minimum number in the assessment of 55

small combatants, with the additional 15 presumably being more frigates.10

10 Annual Procurement Quantities

Congress funded the procurement of the first FFG(X) in FY2020. The Navy'’s FY2021 budget

submission calls for the next nine to be procured during the period FY2021-FY2025 in annual

quantities of 1-1-2-2-3.

Table 1 compares programmed annual procurement quantities for the FFG(X) program in

FY2021-FY2025 under the Navy'’s FY2020 and FY2021 budget submissions. The programmed

quantity of three ships in FY2025 under the Navy'’s FY2021 budget submission suggests that the

Navy, perhaps as a consequence of a potential new surface architecture like that shown in Figure 2Figure

2, might increase FFG(X) procurement to a sustained rate of 3 or more ships per year starting in

FY2025.

FY2025.

Table 1. Programmed Annual FFG(X) Procurement Quantities

As shown in Navy'’s FY2020 and FY2021 budget submissions

FY21

FY22

FY23

FY24

FY25

Total FY21-FY25

FY2020 budget

2

2

2

2

2

10

FY2021 budget

1

1

2

2

3

9

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Navy’s FY2020 and FY2021 budget submissions

|

FY21 |

FY22 |

FY23 |

FY24 |

FY25 |

Total FY21-FY25 |

|

|

FY2020 budget |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

10 |

|

FY2021 budget |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

9 |

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Navy's FY2020 and FY2021 budget submissions.

s FY2020 and FY2021 budget submissions.

Ship Capabilities, Design, and Crewing

Crew ing Ship Capabilities and Design

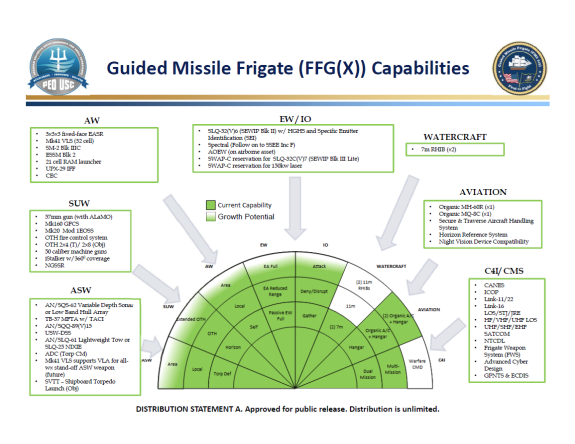

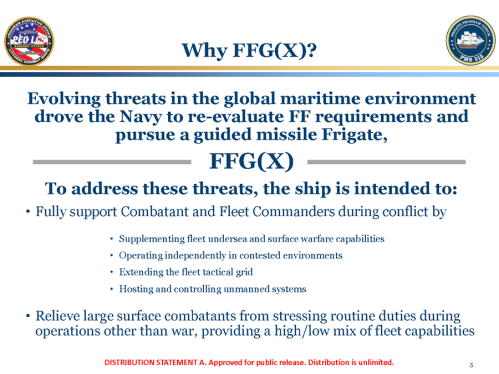

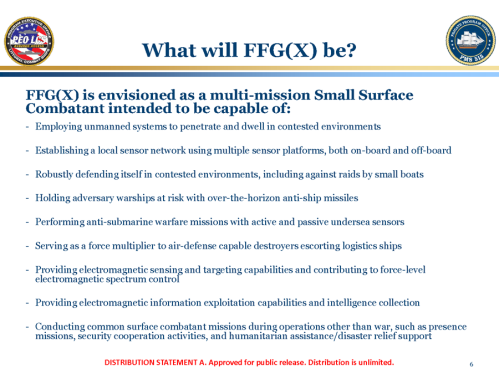

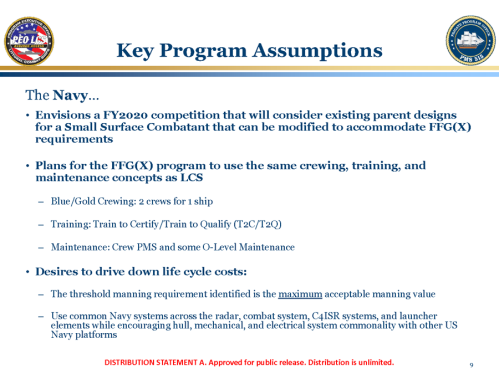

The Navy envisages the FFG(X) as follows:

-

The ship is to be a multimission small surface combatant capable of conducting

-

Compared to an FF concept that emerged under a February 2014 restructuring of

-

The ship

'’s area-defense AAW system is to be capable of local area AAW,area-defenseareadefense AAW that can be provided by the Navy'’s cruisers and destroyers. -

David B. Larter, “ Defense Department Study Calls for Cutting 2 of the US Navy’s Aircraft Carriers,” Defense News,

April 20, 2020.

10

Congressional Research Service

5

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

The ship is to be capable of operating in both blue water (i.e., mid-ocean) and

-

The ship is to be capable of operating either independently (when that is

Figure 3 shows a January 2019 Navy briefing slide summarizing the FFG(X)'’s planned

capabilities. For additional information on the FFG(X)'’s planned capabilities, see Appendix A.11

Dual Crewing

2019.

11

RFI: FFG(X) - US Navy Guided Missile Frigate Replacement Program, accessed August 11, 2017, at

https://www.fbo.gov/index?s=opportunity&mode=form&tab=core&id=d089cf61f254538605cdec5438955b8e&

_cview=0.

Congressional Research Service

6

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Dual Crewing

To help maximize the time that each ship spends at sea, the Navy reportedly is considering

operating FFG(X)s with dual crews—an approach, commonly called blue-gold crewing, that the

Navy uses for operating its ballistic missile submarines and LCSs.12

Procurement Cost

12

Procurement Cost

Congress funded the procurement of the first FFG(X) in FY2020 at a cost of $1,281.2 million

(i.e., about $1.3 billion). The lead ship in the program will be more expensive than the follow -on

ships in the program because the lead ship'’s procurement cost incorporates most or all of the

detailed design/nonrecurring engineering (DD/NRE) costs for the class. (It is a traditional Navy

budgeting practice to attach most or all of the DD/NRE costs for a new ship class to the

procurement cost of the lead ship in the class.)

The Navy wants the follow-on ships in the FFG(X) program (i.e., ships 2 through 20) to have an

average unit procurement cost of $800 million to $950 million each in constant 2018 dollars.13 By 13 By

way of comparison, the Navy estimates the average unit procurement cost of the three LCSs

procured in FY2019 at $523.7 million (not including the cost of each ship'’s embarked mission

package), and the average unit procurement cost of the two DDG-51 class destroyers that the

Navy has requested for procurement in FY2021 at $1,918.5 million.

As shown in Table 3, the Navy'’s proposed FY2021 budget requests $1,053.1 million (i.e., about

$1.1 billion) for the procurement of the second FFG(X), and estimates that subsequent ships in

the class will cost roughly $940 million each in then-year dollars. The Navy'’s FY2021 budget

submission estimates the total procurement cost of 20 FFG(X)s at $19,814.8 million (i.e., about

$19.8 billion) in then-year dollars, or an average of about $990.7 million each. Since the figure of $19,814.8 million is a then-year dollar figure, it incorporates estimated annual inflation for

See, for example, David B. Larter, “T he US Navy Is Planning for Its New Frigate to Be a Workhorse,” Defense

News, January 30, 2018.

12

See Sam LaGrone, “NAVSEA: New Navy Frigate Could Cost $950M Per Hull,” USNI News, January 9, 2018;

Richard Abott, “Navy Confirms New Frigate Nearly $1 Billion Each, 4 -6 Concept Awards By Spring,” Defense Daily,

January 10, 2018: 1; Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “Navy Says It Can Buy Frigate For Under $800M: Acquisition Reform

T estbed,” Breaking Defense, January 12, 2018; Lee Hudson, “Navy to Downselect to One Vendor for Future Frigate

Competition,” Inside the Navy, January 15, 2018; Richard Abott, “Navy Aims For $800 Million Future Frigate Cost,

Leveraging Modularity and Commonality,” Defense Daily, January 17, 2018: 3. T he $800 million figure is the

objective cost target; the $950 million figure is threshold cost target. Regarding the $950 million figure, the Navy states

that

13

T he average follow threshold cost for FFG(X) has been established at $950 million (CY18$). T he

Navy expects that the full and open competition will provide significant downward cost pressure

incentivizing industry to balance cost and capability to provide the Navy with a best value solution.

FFG(X) cost estimates will be reevaluated during the Conceptual Design phase to ensure the

program stays within the Navy’s desired budget while achieving the desired warfighting

capabilities. Lead ship unit costs will be validated at the time the Component Cost Position is

established in 3 rd QT R FY19 prior to the Navy awarding the Detail Design and Construction

contract.

(Navy information paper dated November 7, 2017, provided by Navy Office of Legislative Affairs

to CRS and CBO on November 8, 2017.)

T he Navy wants the average basic construction cost (BCC) of ships 2 through 20 in the program to be $495 million per

ship in constant 2018 dollars. BCC excludes costs for government furnished combat or weapon systems and change

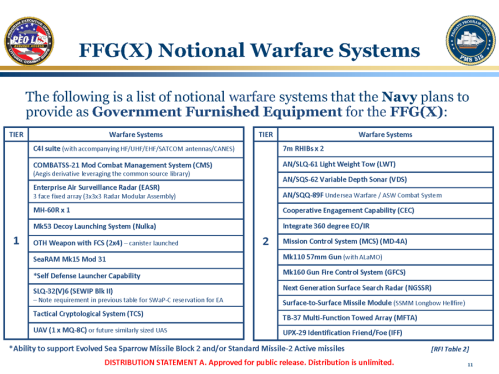

orders. (Source: Navy briefing slides for FFG(X) Industry Day, November 17, 2017, slide 11 of 16, entitled “ Key

Framing Assumptions.”)

Congressional Research Service

7

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

$19,814.8 million is a then-year dollar figure, it incorporates estimated annual inflation for

FFG(X)s to be procured several years into the future.

Acquisition Strategy

FFG(X)s to be procured several years into the future.

Acquisition Strategy

Parent-Design Approach

The Navy'’s plan to procure the first FFG(X) in FY2020 did not allow enough time to develop a

completely new design (i.e., a clean-sheet design) for the FFG(X).14 14 Consequently, the FFG(X) is

to be built to a modified version of an existing ship design—an approach called the parent-design

approach. The parent design can be a U.S. ship design or a foreign ship design.15

15

Using the parent-design approach can reduce design time, design cost, and cost, schedule, and

technical risk in building the ship. The Coast Guard and the Navy are currently using the parent-designparentdesign approach for the Coast Guard'’s Polar Security Cutter (i.e., polar icebreaker) program.16 16

The parent-design approach has also been used in the past for other Navy and Coast Guard ships,

including Navy mine warfare ships17 17 and the Coast Guard'’s new Fast Response Cutters (FRCs).18

18 No New Technologies or Systems

As an additional measure for reducing cost, schedule, and technical risk in the FFG(X) program,

the Navy envisages developing no new technologies or systems for the FFG(X)—the ship is to

use systems and technologies that already exist or are already being developed for use in other

programs.

Number of Builders

The Navy'’s baseline plan for the FFG(X) program envisages using a single builder at any one

time to build the ships. The Navy has not, however, ruled out the option of building the ships at

two or three shipyards at the same time. Consistent with U.S. law,19 19 the ship is to be built in a

shipyard located in the United States, even if it is based on a foreign design.

14

T he Navy states that using an acquisition strategy involving a lengthier requirements-evaluation phase and a cleansheet design would defer the procurement of the first ship to FY2025. (Source: Slide 3, entitled “Accelerating the

FFG(X),” in a Navy briefing entitled “Designing & Building the Surface Fleet: Unmanned and Small Co mbatants,” by

Rear Admiral Casey Moton at a June 20, 2019, conference of the American Society of Naval Engineers [ASNE].)

15

For articles about reported potential parent designs for the FFG(X), see, for example, Chuck Hill, “OPC Derived

Frigate? Designed for the Royal Navy, Proposed for USN,” Chuck Hill’s CG [Coast Guard] Blog, September 15, 2017;

David B. Larter, “BAE Joins Race for New US Frigate with Its T ype 26 Vessel,” Defense News, September 14, 2017;

“BMT Venator-110 Frigate Scale Model at DSEI 2017,” Navy Recognition, September 13, 2017; David B. Larter, “As

the Service Looks to Fill Capabilities Gaps, the US Navy Eyes Foreign Designs,” Defense News, September 1, 2017;

Lee Hudson, “HII May Offer National Security Cutter for Navy Future Frigate Competition,” Inside the Navy, August

7, 2017; Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “ Beyond LCS: Navy Looks T o Foreign Frigates, National Security Cutter ,” Breaking

Defense, May 11, 2017.

16

For more on the polar security cutter program, including the parent -design approach, see CRS Report RL34391,

Coast Guard Polar Security Cutter (Polar Icebreaker) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald

O'Rourke.

T he Navy’s Osprey (MCM-51) class mine warfare ships are an enlarged version of the Italian Lerici-class mine

warfare ships.

17

18

T he FRC design is based on a Dutch patrol boat design, the Damen Stan Patrol Boat 4708.

10 U.S.C. 8679 requires that, subject to a presidential waiver for the national security interest, “no vessel to be

constructed for any of the armed forces, and no major component of the hull or superstructure of any such vessel, may

19

Congressional Research Service

8

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

U.S. Content Requirements for Components

FY2020 Legislation

U.S. Content Requirements for Components

FY2020 Legislation

As part of its action on the Navy'’s FY2020 budget, Congress passed two provisions relating to

U.S. content requirements for certain components of each FFG(X).

Section 856 of the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 1790//P.L. 116-92 of

December 20, 2019) states

SEC. 856. APPLICATION OF LIMITATION ON PROCUREMENT OF GOODS

OTHER THAN UNITED STATES GOODS TO THE FFG–FRIGATE PROGRAM.

Notwithstanding any other provision of law, amounts authorized to carry out the FFG–

Frigate Program may be used to award a new contract that provides for the acquisition of

the following components regardless of whether those components are manufactured in the

United States:

(1) Auxiliary equipment (including pumps) for shipboard services.

(2) Propulsion equipment (including engines, reduction gears, and propellers).

(3) Shipboard cranes.

(4) Spreaders for shipboard cranes.

Section 8113(b) of the FY2020 DOD Appropriations Act (Division A of H.R. 1158//P.L. 116-93 of

December 20, 2019) states

SEC. 8113….

(b) None of the funds provided in this Act for the FFG(X) Frigate program shall be used to

award a new contract that provides for the acquisition of the following components unless

those components are manufactured in the United States: Air circuit breakers;

gyrocompasses; electronic navigation chart systems; steering controls; pumps; propulsion

and machinery control systems; totally enclosed lifeboats; auxiliary equipment pumps;

shipboard cranes; auxiliary chill water systems; and propulsion propellers: Provided, That

the Secretary of the Navy shall in corporate United States manufactured propulsion engines

and propulsion reduction gears into the FFG(X) Frigate program beginning not later than

with the eleventh ship of the program.

Additional Statute and Legislation

In addition to the two above provisions, a permanent statute—10 U.S.C. 2534—requires certain

components of U.S. Navy ships to be made by a manufacturer in the national technology and

industrial base.

In addition, the paragraph in the annual DOD appropriations act that makes appropriations for the Navy'

Navy’s shipbuilding account (i.e., the Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy, or SCN, appropriation

account) has in recent years included this proviso:

…

be constructed in a foreign shipyard.” In addition, the paragraph in the annual DOD appropriations act that makes

appropriations for the Navy’s shipbuilding account (the Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy account) typically contains

these provisos: “ ... Provided further, T hat none of the funds provided under this heading for the construction or

conversion of any naval vessel to be constructed in shipyards in the United States shall be expended in foreign facilities

for the construction of major components of such vessel: Provided further, T hat none of the funds provided under this

heading shall be used for the construction of any naval vessel in foreign shipyards.... ”

Congressional Research Service

9

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

… Provided further, That none of the funds provided under this heading for the

construction or conversion of any naval vessel to be constructed in shipyards in the United

States shall be expended in foreign facilities for the construction of major components of

such vessel….

10 U.S.C. 2534 explicitly applies to certain ship components, but not others. The meaning of "

“major components"” in the above proviso from the annual DOD appropriations act might be

subject to interpretation.

Navy Perspective on FY2020 Legislative Provisions

Regarding the two FY2020 legislative provisions discussed above, the Navy states:

In order to comply with the law, the FFG(X) Detail Design & Construction (DD&C)

Request For Proposal (RFP) Statement of Work (SOW) was amended to include the

following requirements:

C.2.21 Manufacture of Certain Components in the United States

"

“Per Section 8113(b) of Public LawP.L. 116-93: Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, the

Contractor shall ensure that the following components are manufactured in the United

States for each FFG(X) ship: air circuit breakers; gyrocompasses; electronic navigation

chart systems; steering controls; pumps; propulsion and machinery control systems; totally

enclosed lifeboats; auxiliary equipment pumps; shipboard cranes; auxiliary chill water

systems; and propulsion propellers."

” C.2.22 Engine and Reduction Gear Study (Item 0100 only)

"

“The Contractor shall conduct and develop an Engine and Reduction Gear Study

(CDRL A019) documenting the impacts of incorporating United States manufactured

propulsion engines and propulsion reduction gears into the FFG(X) design starting

with the fourth, sixth, eighth, tenth, and eleventh FFG(X) ship."

”

The Navy has assessed the impact of implementing the first part of Section 8113(b) of Public Law P.L.

116-93: Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, which states "“None of the funds provided

in this Act for the FFG(X) Frigate program shall be used to award a new contract that

provides for the acquisition of the following components unless those components are

manufactured in the United States: Air circuit breakers; gyrocompasses; electronic

navigation chart systems; steering controls; pumps; propulsion and machinery control

systems; totally enclosed lifeboats; auxiliary equipment pumps; shipboard cranes; auxiliary

chill water systems; and propulsion propellers,"” for prospective shipbuilders and has

determined the impact is low. The impact of the second part of Section 8113(b) of Public Law P.L.

116-93: Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, which states "“That the Secretary of the

Navy shall incorporate United States manufactured propulsion engines and propulsion

reduction gears into the FFG(X) Frigate program beginning not later than with the eleventh

ship of the program,"” is unknown at this time. After DD&C contract award, the impact

study from the selected FFG(X) shipbuilder will be delivered to the Navy. The Navy will

use these impacts to develop the requested report to Congress no later than six months after

contract award.20

20 Competing Industry Teams

As shown in Table 2, four industry teams competed for the FFG(X) program. Two of the teams—

one including Fincantieri/Marinette Marine (F/MM) of Marinette, WI, and another including

20

Navy information paper on FFG(X) program dated March 27, 2020, provided to CRS and CBO by Navy Office of

legislative Affairs, April 14, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

10

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

General Dynamics/Bath Iron Works (GD/BIW) of Bath, ME—used European frigate designs as

their parent design. A third team—a team including Austal USA of Mobile, AL—used the Navy's ’s

Independence (LCS-2) class Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) design, which Austal USA currently

builds, as its parent design. A fourth team—a team including Huntington Ingalls Industries/Ingalls

Shipbuilding (HII/Ingalls) of Pascagoula, MS—has not disclosed what parent design it used.

For additional background information on the competing industry teams, see Appendix B.

|

Industry team leader |

Parent design |

Shipyard that would build the ships |

|

Austal USA |

Industry team leader Parent design Shipyard that would build the ships Austal USA Independence (LCS-2) class LCS design |

Austal USA of Mobile, AL

Fincantieri Marine

Group

|

|

Fincantieri Marine Group |

Italian Fincantieri FREMM (Fregata |

Fincantieri/Marinette Marine (F/MM) of |

General Dynamics/Bath | Spanish Navantia Álvaro de Bazán-class | General Dynamics/Bath Iron Works |

|

Huntington Ingalls Industries |

[Not disclosed] |

Huntington Ingalls Industries/ Ingalls |

Source: Sam LaGrone and Megan Eckstein, "“Navy Picks Five Contenders for Next Generation Frigate FFG(X)

Program," ” USNI News, February 16, 2018; Sam LaGrone, "“Lockheed Martin Won'’t Submit Freedom LCS Design

for FFG(X) Contest,",” USNI News, May 28, 2019. See also David B. Larter, "“Navy Awards Design Contracts for

Future Frigate," ” Defense News, February 16, 2018; Lee Hudson, "“Navy Awards Five Conceptual Design Contracts

for Future Frigate Competition," ” Inside the Navy, February 19, 2018.

Detail Design and Construction (DD&C) Contract

The FFG(X) contract that the four industry teams competed for is a Detail Design and

Construction (DD&C) contract for up to 10 ships in the program—the lead ship plus nine option

ships. Under such a contract, the Navy has the option of recompeting the program after the lead

ship (if none of the nine option ships are exercised), after the 10th10th ship (if all nine of the option

ships are exercised), or somewhere in between (if some but not all of the nine option ships are

exercised).

As a means of reducing their procurement cost, the Navy may convert the DD&C contract into a

multiyear contract known as a block buy contract to procure the ships.2121 The request for proposals

(RFP) for the DD&C contract stated: "“Following contract award, the Government may designate

any or all of [the nine option ships] as part of a '‘Block Buy.'’ In the event that a Block Buy is

enacted under the National Defense Authorization Act in future fiscal years, the Contractor shall

enter into negotiations with the Government to determine a fair and reasonable price for each

item under the Block Buy. The price of any ship designated as part of the Block Buy shall not

exceed the corresponding non-Block Buy price."22

Contract Award

Under the Navy'”22

21

For more on block buy contracting, see CRS Report R41909, Multiyear Procurement (MYP) and Block Buy

Contracting in Defense Acquisition: Background and Issues for Co ngress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

22 FFG(X) Guided Missile Frigate Detail Design & Construction, Solicitation Number: N0002419R2300 , June 20,

2019, p. 51 of 320, accessed June 25, 2019, at https://www.fbo.gov/index?s=opportunity&mode=form&id=

d7203a2dd8010b79ef62e67ee7850083&tab=core&_cview=1.

Congressional Research Service

11

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Contract Award

Under the Navy’s FY2021 budget submission, the DD&C contract was scheduled to be awarded

in July 2020. The Navy, however, moved up the date for awarding the contract and announced on

April 30, 2020, that it had awarded the FFG(X) contract to the industry team led by F/MM. The

contract award announcement states:

Marinette Marine Corp., Marinette, Wisconsin, is awarded a $795,116,483 fixed-price

incentive (firm target) contract for detail design and construction (DD&C) of the FFG(X)

class of guided-missile frigates, with additional firm-fixed-price and cost reimbursement

line items. The contract with options will provide for the delivery of up to 10 FFG(X) ships,

post-delivery availability support, engineering and class services, crew familiarization,

training equipment and provisioned item orders. If all options are exercised, the cumulative

value of this contract will be $5,576,105,441. Work will be performed at multiple locations,

including Marinette, Wisconsin (52%); Boston, Massachusetts (10%); Crozet, Virginia

(8%); New Orleans, Louisiana (7%); New York, New York (6%); Washington, D.C. (6%),

Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin (3%), Prussia, Pennsylvania (3%), Minneapolis, Minnesota

(2%); Cincinnati, Ohio (1%); Atlanta, Georgia (1%); and Chicago, Illinois (1%). The base

contract includes the DD&C of the first FFG(X) ship and separately priced options for nine

additional ships…. Fiscal 2020 shipbuilding and conversion (Navy) funding in the amount

of $795,116,483 will be obligated at time of award and will not expire at the end of the

current fiscal year. This contract was competitively procured via the Federal Business

Opportunities website and four offers were received. The Navy conducted this competition

using a tradeoff process to determine the proposal representing the best value, based on the

evaluation of non-price factors in conjunction with price. The Navy made the best value

determination by considering the relative importance of evaluation factors as set forth in

the solicitation, where the non-price factors of design and design maturity and objective

performance (to achieve warfighting capability) were approximately equal and each more

important than remaining factors.23

23 Design Selected for FFG(X) Program

Figure 4 shows an artist'’s rendering of F/MM'’s design for the FFG(X). As shown in Table 2, ,

F/MM'’s design for the FFG(X) is based on the design of Fincantieri'’s FREMM (Fregata Europea

Multi-Missione) frigate, a ship that has been built in two variants, one for the Italian navy and one

for the French navy. F/MM officials state that its FFG(X) design is based on the Italian variant,

which has a length of 474.4 feet, a beam of 64.6 feet, a draft of 28.5 feet (including the bow sonar

bulb), and a displacement of 6,900 tons.24 24 F/MM'’s FFG(X) design is slightly longer and

heavier—it has a length of 496 feet, a beam of 65 feet, a draft of 23 to 24 feet (there is no bow

sonar bulb), and an estimated displacement of 7,400 tons, or about 76% as much as the

displacement of a Flight III DDG-51 destroyer.25

Program Funding

, April 30, 2020.

Program Funding

Table 3 shows procurement funding for the FFG(X) program under the Navy'’s FY2021 budget

submission.

Table 3. FFG(X) Program Procurement Funding

Millions of then-year dollars, rounded to nearest tenth.

FY21

Funding

FY23

FY24

FY25

1,053.1

954.5

1,865.9

1,868.8

2,817.3

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

1,053.1

954.5

933.0

934.4

939.1

(Quantity)

Avg. unit cost

FY22

Source: Millions of then-year dollars, rounded to nearest tenth.

|

FY21 |

FY22 |

FY23 |

FY24 |

FY25 |

|

|

Funding |

1,053.1 |

954.5 |

1,865.9 |

1,868.8 |

2,817.3 |

|

(Quantity) |

(1) |

(1) |

(2) |

(2) |

(3) |

|

Avg. unit cost |

1,053.1 |

954.5 |

933.0 |

934.4 |

939.1 |

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Navy FY2021 budget submission.

Table prepared by CRS based on Navy FY2021 budget submission. Issues for Congress

Potential Impact of COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Situation

One issue for Congress concerns the potential impact of the COVID-19 (coronavirus) situation on

the execution of U.S. military shipbuilding programs, including the FFG(X) program. For

additional discussion of this issue, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and

Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Accuracy of Navy'

Congressional Research Service

13

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Accuracy of Navy’s Estimated Unit Procurement Cost

Another potential issue for Congress concerns the accuracy of the Navy'’s estimated unit

procurement cost for the FFG(X), particularly when compared to the known unit procurement

costs of other recent U.S. surface combatants. As detailed by CBO26CBO26 and GAO,27 27 lead ships in

Navy shipbuilding programs in many cases have turned out to be more expensive to build than

the Navy had estimated. If the lead ship in a shipbuilding program turns out to be intrinsically

more expensive to build than the Navy estimated, the follow -on ships in the program will likely

also be more expensive to build than the Navy estimated.

As discussed earlier, the Navy'’s FY2021 budget submission estimates that the third and

subsequent ships in the FFG(X) program will cost roughly $940 million each in then-year dollars

to procure. This equates to a cost of about $127 million per thousand tons of full load

displacement, a figure that is

-

about 36% less than the cost per thousand tons of full load displacement of the

-

about 15% less than the cost per thousand tons of full load displacement of the

-

about 15% less than the cost per thousand tons of full load displacement of the

'’s National Security Cutter (NSC).28

28 Put another way, the FFG(X) has

-

an estimated full load displacement that is about 76% as great as that of the

-

an estimated full load displacement that is about 120% greater than that of the

-

an estimated full load displacement that is about 64% greater than that of the

'’s National Security Cutter (NSC), and an estimated unit29

29

Ships of the same general type and complexity that are built under similar production conditions

tend to have similar costs per weight and consequently unit procurement costs that are more or

less proportional to their displacements. Setting the estimated cost per thousand tons of

displacement of the FFG(X) about equal to those of the LCS-1 variant of the LCS or the NSC

would increase the estimated unit procurement cost of the third and subsequent FFG(X)s from the Navy'

Navy’s estimate of about $940 million to an adjusted figure of about $1,100 million, an increase

of about 17%. Setting the estimated cost per thousand tons of displacement of the FFG(X) about

equal to that of the Flight III DDG-51 would increase the estimated unit procurement cost of the third and subsequent FFG(X)s from the Navy's estimate of about $940 million to an adjusted

See Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the Navy’s Fiscal Year 2019 Shipbuilding Plan, October 2018, p.

25, including Figure 10.

26

27

See Government Accountability Office, Navy Shipbuilding[:] Past Performance Provides Valuable Lessons for

Future Investments, GAO-18-238SP, June 2018, p. 8.

28

For more on the NSC program, see CRS Report R42567, Coast Guard Cutter Procurement: Background and Issues

for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

29 Source: CRS analysis of full load displacements and unit procurement costs of FFG(X), Flight III DDG-51, LCS-1

variant of the LCS, and the NSC.

Congressional Research Service

14

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

third and subsequent FFG(X)s from the Navy’s estimate of about $940 million to an adjusted

figure of about $1,470 million, an increase of about 56%.

figure of about $1,470 million, an increase of about 56%.

Potential oversight questions for Congress include the following:

-

What is the Navy

'’s basis for its view that the FFG(X)—a ship aboutthree-quartersthreequarters as large as the Flight III DDG-51, and with installed capabilities that areone-halfonehalf the cost of the Flight III DDG-51? -

DDG-51s are procured using multiyear procurement (MYP), which reduces their

3030 Would adjusting for this difference by assuming the use of -

What is the Navy

'’s basis for its view that the FFG(X)—a ship with a full31 - 31

What is the Navy

'’s basis for its view that the FFG(X)—a ship built to Navymore-modestmoremodest collection of combat system equipment? -

To what degree can differences in costs for building ships at F/MM compared to

'’s lower estimated cost per thousand tons displacement? -

To what degree can the larger size of the FFG(X) compared to the LCS-1 variant

'’s lower estimated cost per -

To what degree will process improvements at F/MM, beyond those that were in

'’s estimated cost -

How much might the cost of building FFG(X)s be reduced by converting the

Regarding the Navy's estimated cost for procuring FFG(X)s, an August 2019 Government

30

For additional discussion of the savings that are possible with MYP contracts, see CRS Report R41909, Multiyear

Procurement (MYP) and Block Buy Contracting in Defen se Acquisition: Background and Issues for Congress, by

Ronald O'Rourke.

31

Some of the combat system equipment of a deployed LCS consists of a modular mission package is not permanently

built into the ship. T hese modular mission packages are procured separately from the ship, and their procurement costs

are not included in the unit procurement costs of LCSs. For additional discussion, see CRS Report RL33741, Navy

Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Congressional Research Service

15

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Regarding the Navy’s estimated cost for procuring FFG(X)s, an August 2019 Government

Accountability Office (GAO) report on the FFG(X) program states:

Accountability Office (GAO) report on the FFG(X) program states:

The Navy undertook a conceptual design phase for the FFG(X) Guided Missile Frigate

program that enabled industry to inform FFG(X) requirements, identify opportunities for

cost savings, and mature different ship designs. The Navy also streamlined the FFG(X)

acquisition approach in an effort to accelerate the timeline for delivering the ships to the

fleet…. [H]owever, the Navy has requested funding for the FFG(X) lead ship even though

it has yet to complete key cost estimation activities, such as an independent cost estimate,

to validate the credibility of cost expectations. Department of Defense (DOD) cost

estimators told GAO the timeline for completing the independent cost estimate is uncertain.

Specifically, they stated that this estimate will not be finalized until the Navy

communicates to them which FFG(X) design is expected to receive the contract award.

GAO-identified best practices call for requisite cost knowledge to be available to inform

resource decisions and contract awards.32

32

An October 2019 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report on the cost of the Navy's ’s

shipbuilding programs stated the following about the FFG(X) (emphasis added):

The four shipbuilders in the [FFG(X)] competition are using existing designs that have

displacements of between 3,000 tons and almost 7,000 tons.

The Navy'’s cost goal for the program is currently set at $1.2 billion for the first ship of the

class and an average cost of $800 million to $950 million for the remaining 19 ships.

Because the 2020 shipbuilding plan estimates an average cost of slightly more than $850

million each for all 20 ships—an amount near the lower end of the Navy'’s cost goal—

actual costs would probably exceed the estimates. Historically, the costs of lead ships have

grown by 27 percent, on average, over the Navy'’s initial estimates…. Taking into account

all publicly available information, CBO'CBO’s estimate reflects an assumption that the

FFG(X) would displace about 4,700 tons, or the median point of the four proposed ship

designs in competition for the program contract. As a result, CBO estimates the average

cost of the FFG(X)s at $1.2 billion each, for a total cost of $23 billion, compared with the Navy'

Navy’s estimate of $17 billion. Uncertainty about the frigate design makes that estimate

difficult to determine.33

33 Number of FFG(X)s to Procure in FY2021

Another issue for Congress is whether to fund the procurement in FY2021 of one FFG(X) (the Navy'

Navy’s request), no FFG(X), or two FFG(X)s.

Supporters of procuring no FFG(X) in FY2021 could argue that traditionally there has often been

a so-called gap year in Navy shipbuilding programs—a year of no procurement between the year

that the lead ship is procured and the year that the second ship is procured. This gap year, they

could argue, is intended to provide some time to discover through the ship'’s construction process

problems in the ship'’s design that did not come to light during the design process, and fix those

problems before they are built into one or more follow-on ships in the class. Given the Navy's ’s

experience with its previous small surface combatant shipbuilding program—the Littoral Combat

Ship (LCS) program—they could argue, inserting a gap year into the FFG(X)'’s procurement

profile would be prudent.

32

Government Accountability Office, Guide Missile Frigate[:] Navy Has Taken Steps to Reduce Acquisition Risk, but

Opportunities Exist to Improve Knowledge for Decision Makers, GAO-19-512, August 2019, summary page.

33 Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the Navy’s Fiscal Year 2020 Shipbuilding Plan , October 2019,

pp. 252-26.

Congressional Research Service

16

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Supporters of procuring one FFG(X) in FY2021 (rather than none) could argue that although

including a gap year is a traditional practice in Navy shipbuilding programs, it has not always

been used; that the era of computer-aided ship design (compared to the earlier era of paper

designs) has reduced the need for gap years; that the need for a gap year in the FFG(X) program

is further reduced by the program'’s use of a parent design rather than a clean-sheet design; and

that a gap year can increase the cost of the second and subsequent ships in the program by

causing an interruption in the production learning curve and a consequent loss of learning at the

shipyard and supplier firms in moving from production of the first ship to the second. Supporters

of procuring one FFG(X) (rather than two) could argue that immediately moving from one ship in

FY2020 to two ships in FY2021 could cause strains at the shipyard and thereby increase program

risks, particularly given the challenges that shipyards have often encountered in building the first

ship in a shipbuilding program, and that the funding needed for the procurement of a second

FFG(X) in FY2021 could be better spent on other Navy program priorities.

Supporters of procuring two FFG(X)s in FY2021 could argue that the Navy'’s FY2020

shipbuilding plan (see Table 1) called for procuring two FFG(X)s in FY2021; that procuring one

FFG(X) rather than two in FY2021 reduces production economies of scale in the FFG(X)

program at the shipyard and supplier firms, thereby increasing unit procurement costs; and that

procuring two FFG(X)s rather than one in FY2021 would help close more quickly the Navy's ’s

large percentage shortfall in small surface combatants relative to the Navy'’s force-level goal for

such ships.

Number of FFG(X) Builders

Another issue for Congress is whether to build FFG(X)s at a single shipyard (the Navy'’s baseline

plan), or at two or three shipyards. The Navy'’s FFG-7 class frigates, which were procured at

annual rates of as high as eight ships per year, were built at three shipyards.

In considering whether to build FFG(X)s at a single shipyard (the Navy'’s baseline plan), or at two

or three shipyards, Congress may consider several factors, including but not limited to the annual

FFG(X) procurement rate, shipyard production capacities and production economies of scale, the

potential costs and benefits in the FFG(X) program of employing recurring competition between

multiple shipyards, and how the number of FFG(X) builders might fit into a larger situation

involving the production of other Navy and Coast Guard ships, including Navy DDG-51

destroyers, Navy amphibious ships, Coast Guard National Security Cutters (NSCs), and Coast

Guard Offshore Patrol Cutters (OPCs).34

34 U.S. Content Requirements

Another issue for Congress is whether to take any further legislative action regarding U.S. content c ontent

requirements for FFG(X)s. Potential options include amending, repealing, or replacing one or

both of the two previously mentioned U.S. content provisions for the FFG(X) program that

Congress passed in FY2020, passing a new, separate provision of some kind, or doing none of

these things.

34

For more on the DDG-51 program, see CRS Report RL32109, Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs:

Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke. For more on Navy amphibious shipbuilding programs, see

CRS Report R43543, Navy LPD-17 Flight II and LHA Amphibious Ship Programs: Background and Issues for

Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke. For more on the NSC and OPC programs, see CRS Report R42567, Coast Guard

Cutter Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Congressional Research Service

17

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

In considering whether to take any further legislative action on the issue, Congress may consider

several factors, including the potential impacts of the two U.S. content provisions that Congress

passed in FY2020. Some observers view these two provisions as being in tension with one

another.35 35 In instances where differences between two enacted laws might need to be resolved,

one traditional yardstick is to identify the legislation that was enacted later, on the grounds that it

represents the final or most-recent word of the Congress on the issue. Although FY2020 National

Defense Authorization Act and the FY2020 DOD Appropriations Act were signed into law on the

same day (December 20, 2019), the P.L. numbers assigned to the two laws appear to indicate that

the FY2020 DOD Appropriations Act was enacted later than the FY2020 National Defense

Authorization Act. It can also be noted that Section 8113(b) of the FY2020 DOD Appropriations

Act is a provision relating to the use of FY2020 funds, while Section 856 of the FY2020 National

Defense Authorization Act refers to amounts authorized without reference to a specific fiscal year.

Required Capabilities and Growth Margin

Another issue for Congress is whether the Navy has appropriately defined the required

capabilities and growth margin of the FFG(X).

Analytical Basis for Desired Ship Capabilities

One aspect of this issue is whether the Navy has an adequately rigorous analytical basis for its

identification of the capability gaps or mission needs to be met by the FFG(X), and for its

decision to meet those capability gaps or mission needs through the procurement of a FFG with

the capabilities outlined earlier in this CRS report. The question of whether the Navy has an

adequately rigorous analytical basis for these things was discussed in greater detail in earlier

editions of this CRS report.36

36 Number of VLS Tubes

Another potential aspect of this issue concerns the planned number of Vertical Launch System

(VLS) missile tubes on the FFG(X). The VLS is the FFG(X)'’s principal (though not only) means

of storing and launching missiles. As shown in Figure 3 (see the box in the upper-left corner

labeled "“AW,"” meaning air warfare), the FFG(X) is to be equipped with 32 Mark 41 VLS tubes.

(The Mark 41 is the Navy'’s standard VLS design.)

Supporters of requiring the FFG(X) to be equipped with a larger number of VLS tubes, such as

48, might argue that the FFG(X) is to be roughly half as expensive to procure as the DDG-51

destroyer, and might therefore be more appropriately equipped with 48 VLS tubes, which is one-halfonehalf the number on recent DDG-51s. They might also argue that in a context of renewed great

power competition with potential adversaries such as China, which is steadily improving its naval

capabilities,37 37 it might be prudent to equip the FFG(X)s with 48 rather than 32 VLS tubes, and

that doing so might only marginally increase the unit procurement cost of the FFG(X).

Supporters of requiring the FFG(X) to have no more than 32 VLS tubes might argue that the

analyses indicating a need for 32 already took improving adversary capabilities (as well as other

See, for example, Ben Werner and Sam LaGrone, “ FY 2020 Defense Measures Almost Law; Bills Contain

Conflicting Language on FFG(X),” USNI News, December 20, 2019.

35

36

See, for example, the version of this report dated February 4, 2019.

For more on China’s naval modernization effort, see CRS Report RL33153, China Naval Modernization:

Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

37

Congressional Research Service

18

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

U.S. Navy capabilities) into account. They might also argue that F/MM'’s design for the FFG(X),

in addition to having 32 VLS tubes, will also to have separate, deck-mounted box launchers for

launching 16 anti-ship cruise missiles, as well as a separate, 21-cell Rolling Airframe Missile

(RAM) AAW missile launcher; that the Navy plans to deploy additional VLS tubes on its planned

Large Unmanned Surface Vehicles (LUSVs), which are to act as adjunct weapon magazines for

the Navy'’s manned surface combatants;3838 and that increasing the number of VLS tubes on the

FFG(X) from 32 to 48 would increase (even if only marginally) the procurement cost of a ship

that is intended to be an affordable supplement to the Navy'’s cruisers and destroyers.

A May 14, 2019, Navy information paper on expanding the cost impact of expanding the FFG(X)

VLS capacity from 32 cells to 48 cells states

To grow from a 32 Cell VLS to a 48 Cell VLS necessitates an increase in the length of the

ship with a small beam increase and roughly a 200-ton increase in full load displacement.

This will require a resizing of the ship, readdressing stability and seakeeping analyses, and

adapting ship services to accommodate the additional 16 VLS cells.

A change of this nature would unnecessarily delay detail design by causing significant

disruption to ship designs. Particularly the smaller ship designs. Potential competitors have

already completed their Conceptual Designs and are entering the Detail Design and

Construction competition with ship designs set to accommodate 32 cells.

The cost is estimated to increase between $16M [million] and $24M [million] per ship.

This includes ship impacts and additional VLS cells.39

39

Compared to an FFG(X) follow-on ship unit procurement cost of about $900 million, the above

estimated increase of $16 million to $24 million would equate to an increase in unit procurement

cost of about 1.8% to about 2.7%.

Growth Margin

Grow th Margin

Another potential aspect of this issue is whether the Navy more generally has chosen the

appropriate amount of growth margin to incorporate into the FFG(X) design. As shown in the

Appendix A, the Navy wants the FFG(X) design to have a growth margin (also called service life

allowance) of 5%, meaning an ability to accommodate upgrades and other changes that might be

made to the ship'’s design over the course of its service life that could require up to 5% more

space, weight, electrical power, or equipment cooling capacity. As shown in the Appendix A, the

Navy also wants the FFG(X) design to have an additional growth margin (above the 5% factor)

for accommodating a future directed energy system (i.e., a laser or high-power microwave

device) or an active electronic attack system (i.e., electronic warfare system).

Supporters could argue that a 5% growth margin is traditional for a ship like a frigate, that the

FFG(X)'’s 5% growth margin is supplemented by the additional growth margin for a directed

energy system or active electronic attack system, and that requiring a larger growth margin could

make the FFG(X) design larger and more expensive to procure.

Skeptics might argue that a larger growth margin (such as 10%—a figure used in designing

cruisers and destroyers) would provide more of a hedge against the possibility of greater-than-anticipatedthananticipated improvements in the capabilities of potential adversaries such as China, that a limited

38

For additional discussion, see CRS Report R45757, Navy Large Unmanned Surface and Undersea Vehicles:

Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Navy information paper entitled “FFG(X) Cost to Grow to 48 cell VLS,” dated May 14, 2019, received from Navy

Office of Legislative Affairs on June 14, 2019.

39

Congressional Research Service

19

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

growth margin was a concern in the FFG-7 design, 40growth margin was a concern in the FFG-7 design,40 and that increasing the FFG(X) growth

margin from 5% to 10% would have only a limited impact on the FFG(X)'’s procurement cost.

A potential oversight question for Congress might be: What would be the estimated increase in

unit procurement cost of the FFG(X) of increasing the ship'’s growth margin from 5% to 10%?

Technical Risk

Technical Risk

Another potential oversight issue for Congress concerns technical risk in the FFG(X) program.

The Navy can argue that the program'’s technical risk has been reduced by use of the parent-designparentdesign approach and the decision to use only systems and technologies that already exist or are

already being developed for use in other programs, rather than new technologies that need to be

developed. Skeptics, while acknowledging that point, might argue that lead ships in Navy

shipbuilding programs inherently pose technical risk, because they serve as the prototypes for

their programs.

May 2019 GAO Report

A May 2019

June 2020 GAO Report

A June 2020 GAO report on the status of various Department of Defense (DOD) acquisition

programs states the following about the FFG(X) program:

Technology Maturity

The Navy completed a technology readiness assessment for FFG(X) in March 2019. The

assessment, which Navy officials said included a review of about 150 systems, identified

no critical technology elements that pose major technological risk during development.

DOD has yet to complete an independent technical risk assessment for FFG(X). An official

from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering who is

participating in the FFG(X) risk assessment said that delays in obtaining required

information from the Navy make it unlikely the assessment will be completed before the

program’s development start decision. If incomplete, information available to inform

decision makers on the sufficiency of the Navy’s efforts to account for technical risk factors

will be diminished.

The FFG(X) design approach includes the use of many existing combat and mission

systems to reduce technical risk. However, one key system—the Enterprise Air

Surveillance Radar (EASR)—is still in development by another program. EASR, which is

a scaled down version of the Navy Air and Missile Defense Radar program’s AN/SPY6(V)1 radar currently in production, is expected to provide long -range detection and

engagement of advanced threats. The Navy is currently conducting land-based testing on

an EASR advanced prototype, with FFG(X)-specific testing planned to begin in 2022. The

Navy also expects to integrate versions of the radar on other ship classes beginning in 2021,

which may reduce integration risk for FFG(X) if the Navy is able to incorporate lessons

learned from integration on other ships during FFG(X) detail design activities.

Design Stability

The Navy used the results from an FFG(X) conceptual design phase to inform the

program’s May 2019 preliminary design review as well as the ongoing contract award

process for detail design and construction of the lead ship. In early 2018, the Navy

competitively awarded FFG(X) conceptual design contracts to five industry teams.

40

See, for example, See U.S. General Accounting Office, Statement of Jerome H. Stolarow, Director, Procurement and

Systems Acquisition Division, before the Subcommittee on Priorities and Economy in Government, Joint Economic

Committee on T he Navy’s FFG-7 Class Frigate Shipbuilding Program, and Other Ship Program Issues, January 3,

1979, pp. 9-11.

Congressional Research Service

20

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Conceptual design was intended to enable industry to mature parent ship designs for

FFG(X)—designs based on ships that have been built and demonstrated at sea—as well as

inform requirements and identify opportunities for cost savings. Navy officials said the

specific plan for detail design will be determined based on the winning proposal.

Software and Cybersecurity

According to the FFG(X) acquisition strategy, the program is structured to provide mission

systems and associated software to the shipbuilder as government-furnished equipment.

These systems, which are provided by other Navy programs, include a new version of the

Aegis Weapon System—FFG(X)’s combat management system—to coordinate radar and

weapon system interactions from threat detection to target strike. Navy officials said

FFG(X)’s Aegis Weapon System will leverage at least 90 percent of its software from the

Aegis common source software that supports combat systems found on other Navy ships,

such as the DDG 51-class destroyers.

The Navy approved the FFG(X) cybersecurity strategy in March 2019. The strategy states

the program’s cyber survivability requirement was a large driver in the development of

network architecture. The Navy’s strategy also emphasizes the importance of the ability of

the ship to operate in a cyber-contested environment. The Navy will consider cybersecurity

for the systems provided by the shipbuilder—which control electricity, machinery, damage

control, and other related systems—as part of selecting the FFG(X) design.

Other Program Issues

In October 2019, DOD confirmed that the Navy did not request that prospective

shipbuilders include warranty pricing to correct defects after ship deliveries in their

proposals for the competitive FFG(X) detail design and construction contract award, as we

previously recommended. Instead, the Navy required that the proposals include guaranty

pricing with limited liability of at least $5 million to correct defects, which could allow for

a better value to the government than has been typical for recent shipbuilding programs.

However, warranty pricing could have provided the Navy with complete information on

the cost-effectiveness of a warranty versus a guaranty. Our prior work has found that using

comprehensive ship warranties instead of guarantees could reduce the Navy’s financial

responsibility for correcting defects and foster quality performance by linking the

shipbuilder’s cost to correct deficiencies to its profit.

programs states the following about the FFG(X) program:

Current Status

The FFG(X) program continues conceptual design work ahead of planned award of a lead ship detail design and construction contract in September 2020. In May 2017, the Navy revised its plans for a new frigate derived from minor modifications of an LCS design. The current plan is to select a design and shipbuilder through full and open competition to provide a more lethal and survivable small surface combatant.

As stated in the FFG(X) acquisition strategy, the Navy awarded conceptual design contracts in February 2018 for development of five designs based on ships already demonstrated at sea. The tailoring plan indicates the program will minimize technology development by relying on government-furnished equipment from other programs or known-contractor-furnished equipment.

In November 2018, the program received approval to tailor its acquisition documentation to support development start in February 2020. This included waivers for several requirements, such as an analysis of alternatives and an affordability analysis for the total program life cycle. FFG(X) also received approval to tailor reviews to validate system specifications and the release of the request for proposals for the detail design and construction contract….

Program Office Comments

Program Office Comments

We provided a draft of this assessment to the program office for review and comment. The program office did not have any comments.41

program office provided technical comments, which we incorporated where appropriate.

The program office stated that the Navy is working to satisfy the requirement for an

independent technical risk assessment requirement prior to development start. Regarding

warranties, the program office stated the solicitation allows shipbuilders to propose a limit

of liability beyond the $5 million requirement. It said this arrangement represents an

appropriate balance between price and risk; ensures that the shipbuilder is accountable for

the correction of defects that follow acceptance; and allows shipbuilders to use their own

judgment in proposing the value of the limit of liability. The program office also said the

Navy will evaluate the extent to which any additional liability amount proposed above the

minimum requirement provides a meaningful benefit to the government, and will evaluate

favorably a higher proposed limitation of liability value, up to an unlimited guaranty. 41

41

Government Accountability Office, Defense Acquisitions Annual Assessment[:] Drive to Deliver Capabilities Faster

Increases Importance of Program Knowledge and Consistent Data for Oversight GAO-20-439, p. 124.

Congressional Research Service

21

Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Guaranty vs. Warranty in Construction Contract

Guaranty vs. Warranty in Construction Contract

Another aspect of this issue concerns the Navy'’s use of a guaranty rather than a warranty in the

Detail Design and Construction (DD&C) contract for the FFG(X) program. An August 2019

GAO report on the FFG(X) program states

The Navy plans to use a fixed-price incentive contract for FFG(X) detail design and

construction. This is a notable departure from prior Navy surface combatant programs that

used higher-risk cost-reimbursement contracts for lead ship construction. The Navy also

plans to require that each ship has a minimum guaranty of $5 million to correct shipbuilder-responsibleshipbuilderresponsible defects identified in the 18 months following ship delivery. However, Navy

officials discounted the potential use of a warranty—another mechanism to address the

correction of shipbuilder defects—stating that their use could negatively affect

shipbuilding cost and reduce competition for the contract award. The Navy provided no

analysis to support these claims and has not demonstrated why the use of warranties is not

a viable option. The Navy'’s planned use of guarantees helps ensure the FFG(X) shipbuilder

is responsible for correcting defects up to a point, but guarantees generally do not provide

the same level of coverage as warranties. GAO found in March 2016 that the use of a

guaranty did not help improve cost or quality outcomes for the ships reviewed. GAO also

found the use of a warranty in commercial shipbuilding and certain Coast Guard ships

improves cost and quality outcomes by requiring the shipbuilders to pay to repair defects.

The FFG(X) request for proposal offers the Navy an opportunity to solicit pricing for a

warranty to assess the cost-effectiveness of the different mechanisms to address ship

defects.42

42

As discussed in another CRS report,43 43 in discussions of Navy (and also Coast Guard)

shipbuilding, a question that sometimes arises is whether including a warranty in a shipbuilding

contract is preferable to not including one. The question can arise, for example, in connection

with a GAO finding that "“the Navy structures shipbuilding contracts so that it pays shipbuilders

to build ships as part of the construction process and then pays the same shipbuilders a second

time to repair the ship when construction defects are discovered."44

”44

Including a warranty in a shipbuilding contract (or a contract for building some other kind of

defense end item), while potentially valuable, might not always be preferable to not including

one—it depends on the circumstances of the acquisition, and it is not necessarily a valid criticism

of an acquisition program to state that it is using a contract that does not include a warranty (or a

weaker form of a warranty rather than a stronger one).

Including a warranty generally shifts to the contractor the risk of having to pay for fixing

problems with earlier work. Although that in itself could be deemed desirable from the government'

government’s standpoint, a contractor negotiating a contract that will have a warranty will

incorporate that risk into its price, and depending on how much the contractor might charge for

doing that, it is possible that the government could wind up paying more in total for acquiring the

item (including fixing problems with earlier work on that item) than it would have under a

contract without a warranty.

42

Government Accountability Office, Guide Missile Frigate[:] Navy Has Taken Steps to Reduce Acquisition Risk, but

Opportunities Exist to Improve Knowledge for Decision Makers, GAO-19-512, August 2019, summary page.

43

See CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by

Ronald O'Rourke.

44