Libya: Transition and U.S. Policy

Changes from April 13, 2020 to June 26, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

Contents

- Overview

- Libya and COVID-19

- Status of Conflict and Diplomatic Efforts

- Key Issues in Libya's Troubled Transition

- Conflict Developments Since April 2019

- Political Dynamics and Considerations

- Oil, Fiscal Challenges, and Institutional Rivalry

- Oil Cutoff and Market Forces Create Fiscal Pressure

- Rivalries Persist Among Key Libyan Institutions

- Sanctions and Arms Embargo Provisions

- U.N. Security Council Measures

- U.S. and European Sanctions

- Arms Embargo Enforcement and Violations

- Human Rights and Migration

- Non-State Actors Violate Human Rights with Impunity

- Flows Decline, but Migrants Face Risks and Abuse

- U.S. Interests and Approaches

- Administration Policy and Initiatives

- Counterterrorism Operations and Strategic Competition

- U.S. Foreign Assistance and Humanitarian Aid

- Congress and Libya

- Debate in the 116th Congress

- Possible Scenarios and Issues for Congress

- If ceasefire initiatives show promise...

- If ceasefire initiatives falter and conflict intensifies...

- Outlook

Figures

Summary

Libya'Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

June 26, 2020

Libya’s political transition has been disrupted by armed non-state groups and threatened by the indecision and infighting of interim leaders. After aan uprising ended the 40-plus-year rule of

Christopher M. Blanchard

Muammar al Qadhafi in 2011, interim authorities proved unable to form a stable government,

Specialist in Middle

address security issues, reshape the country'’s finances, or create a viable framework for post-

Eastern Affairs

conflict justice and reconciliation. Insecurity spread as local armed groups competed for

influence and resources. Qadhafi compounded stabilization challenges by depriving Libyans of experience in self-government, stifling civil society, and leaving state institutions weak. Militias,

local leaders, and coalitions of national figures with competing foreign patrons remain the most powerful arbiters of public affairs. An atmosphere of persistent lawlessness has enabled militias, criminals, and Islamist terrorist groups to operate with impunity, while recurrent conflict has endangered civilians'’ rights and safety. Issues of dispute have included governance, military command, national finances, and control of oil infrastructure.

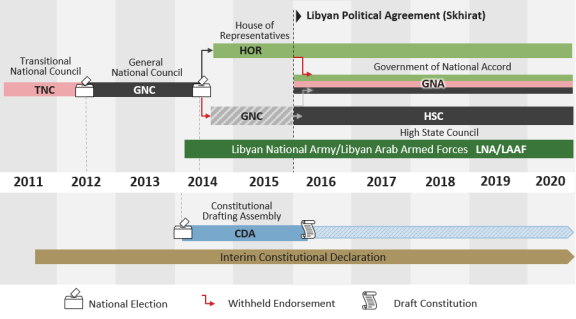

Key Issues and Actors in Libya. After a previous round of conflict in 2014, the country'’s transitional institutions fragmented. A Government of National Accord (GNA) based in the capital, Tripoli, took power under the 2015 U.N.-brokered Libyan Political Agreement. Leaders of the House of Representatives (HOR) that were elected in 2014 declined to endorse the GNA, and they and a rival interim government based in eastern Libya have challenged the GNA'’s authority with support from the Libyan National Army/Libyan Arab Armed Forces (LNA/LAAF) movement. The LNA/LAAF is a coalition of armed groups led by Qadhafi-era military officer Khalifa Haftar: it conducted military operations against Islamist groups in eastern Libya from 2014 to 2019 and upended U.N. mediation efforts by launching a surprise offensive in April 2019, seeking to wrest control of Tripoli from the GNA and local militias.

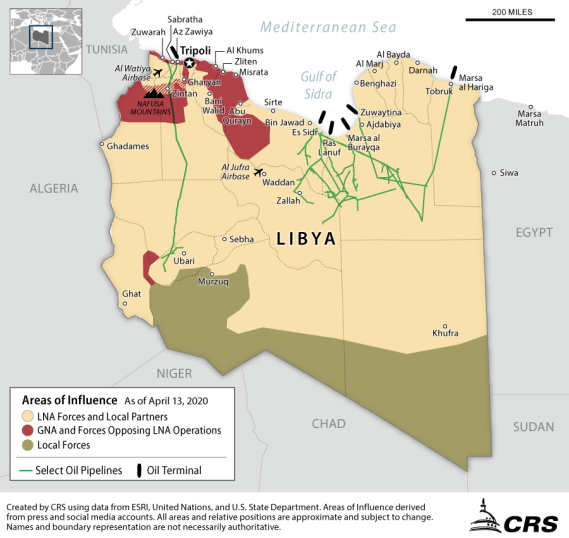

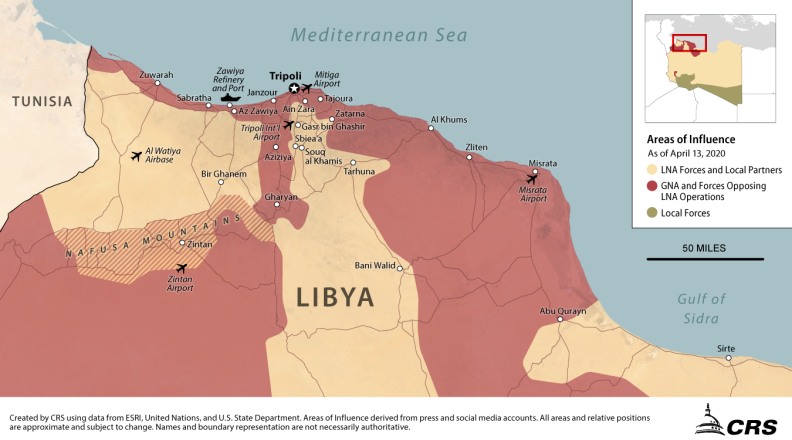

Fighters in western Libya rallied to blunt the LNA's advance, and inconclusive fighting has continued despite multilateral demands for a ceasefire. As of 2020, LNA forces and local partners control much of Libya's territory and key oil production and export infrastructure directly or through allies. GNA supporters and anti-LNA groups retain control of the capital and other key western areas.

’s advance and leveraged Turkish military support to force LNA fighters and foreign mercenaries to withdraw from northwestern Libya in May and June 2020. Inconclusive fighting has continued since then near the coastal city of Sirte and the Al Jufra air base in central Libya, despite multilateral demands for a ceasefire. Turkey has indicated its support for further GNA advances, and Egypt has warned that it would intervene if its leaders conclude Egyptian interests are threatened (see sources in report). LNA forces and local partners control eastern Libya and key oil production and export infrastructure directly or through allies. They and GNA supporters continue to compete for influence and control in the southwestern parts of the country.

Foreign actors, including U.S. partners in Europe and the Middle East, have long found themselves at odds over Libya's ’s conflict, and several countries have provided increased military assistance to warring Libyan parties since April 2019 in violation of a longstanding U.N. arms embargo. According to U.S. officials, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates arm the LNA. Conflict dynamics have shifted over time because of weapons shipments to both sides, the presence of Russian-national private contractors and Syrian and other foreign fighters among LNA forces, the conclusion of Turkey-GNA maritime and security agreements, and Turkish deployments of soldiers, equipment, and Syrian mercenaries on behalf of the GNA, and expanded weapons shipments to both sides.

.

Conflict, COVID-19, and U.S. Responses. Since April 2019, fighting has killed more than 2,200600 Libyans (including hundreds of civilians), and fighting in June 2020 has displaced nearly 28,000 people in western and central and displaced more than 149,000 people near Tripoli. U.N. officials report that nearly 345,000 people are in frontline areas. More than 650,000 foreign migrants also are present in Libya and remain vulnerable. In 2020, U.S. and U.N. officials have condemned new weapons shipments to Libya and called for a humanitarian ceasefire to allow Libyans to address the threats posed by the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)COVID-19 pandemic. Humanitarian access is restricted and parties to the conflict have shut down national oil production.

and national oil production remain restricted.

State Department officials have condemned what they regards as "“toxic foreign interference"” and have called for "“a sovereign Libya free of foreign intervention."” In March 2020, U.S. officials called on Libyans to cease fighting, bolster public finances, and prioritize support to the health system in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Visiting Libya in June 2020, U.S. Ambassador Richard Norland and U.S. Africa Command Commander General Stephen Townsend told GNA officials that “all sides need to return to U.N.-led ceasefire and political negotiations.” U.S. diplomats engage with Libyans and monitor U.S. aid programs via the Libya External Office (LEO) at the U.S. Embassy in Tunisia. Congress has conditionally appropriated funding for transition support, stabilization, security assistance, and humanitarian programs for Libya since 2011, and is considering proposals to authorize additional assistance (H.R. 4644 and S. 2934).

Overview

Libya's 2011 uprising and conflict brought Muammar al Qadhafi').

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 27 link to page 28 link to page 30 link to page 30 link to page 31 link to page 31 link to page 32 link to page 32 link to page 6 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 29 link to page 36 link to page 38 link to page 38 Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

Contents

Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Libya and COVID-19 ...................................................................................................................... 2 Status of Conflict and Diplomatic Efforts ....................................................................................... 3

Key Issues in Libya’s Troubled Transition ............................................................................... 3 Conflict Developments Since April 2019 .................................................................................. 3 Political Dynamics and Considerations ................................................................................... 10

Oil, Fiscal Challenges, and Institutional Rivalry ............................................................................ 11

Oil Cutoff and Market Forces Create Fiscal Pressure .............................................................. 11 Rivalries Persist Among Key Libyan Institutions ................................................................... 12

Sanctions and Arms Embargo Provisions ...................................................................................... 14

U.N. Security Council Measures ............................................................................................. 14 U.S. and European Sanctions .................................................................................................. 15 Arms Embargo Enforcement and Violations ........................................................................... 17

Human Rights and Migration ........................................................................................................ 18

Non-State Actors Violate Human Rights with Impunity ......................................................... 18 Flows Decline, but Migrants Face Risks and Abuse ............................................................... 19

U.S. Interests and Approaches ....................................................................................................... 21

Administration Policy and Initiatives ...................................................................................... 21 Counterterrorism Operations and Strategic Competition ........................................................ 23 U.S. Foreign Assistance and Humanitarian Aid ...................................................................... 24

Congress and Libya ....................................................................................................................... 26

Debate in the 116th Congress ................................................................................................... 26 Possible Scenarios and Issues for Congress ............................................................................ 27

If ceasefire initiatives show promise... .............................................................................. 27 If ceasefire initiatives falter and conflict intensifies... ...................................................... 28

Outlook .......................................................................................................................................... 28

Figures Figure 1. Libya’s Post-Qadhafi Transition, 2011-2020 ................................................................... 2 Figure 2. Libya’s Warring Coalitions .............................................................................................. 4

Tables Table 1. Libya Map and Facts ......................................................................................................... 5 Table 2. U.S. Foreign Assistance for Programs in Libya .............................................................. 25

Appendixes Appendix A. Libyan History, Civil War, and Political Change ..................................................... 32 Appendix B. Investigations into 2012 Attacks on U.S. Facilities and Personnel in

Benghazi ..................................................................................................................................... 34

Congressional Research Service

link to page 38 Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 34

Congressional Research Service

link to page 6 link to page 9 link to page 8 link to page 36 Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

Overview Libya’s 2011 uprising and conflict brought Muammar al Qadhafi’s four decades of authoritarian rule to an end. Competing factions and alliances—organized along local, regional, ideological, tribal, and personal lines—have jockeyed for influence and power in post-Qadhafi Libya, at times with the backing of rival foreign governments. In 2018, Ghassan Salamé, then-Special Representative of the U.N. Secretary-General (SRSG) and head of the U.N. Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), argued that Libyans were struggling to overcome a political "“discourse of hatred" and "hatred” and “mutual exclusion"” that had prevented the completion of the country'’s transition to date.11 This discourse is in part a legacy of Qadhafi'’s decades of divisive rule and in part a product of the divisiveness, insecurity, and zero-sum competition that have followed his downfall.

Although some observers attribute Libya'’s divisive politics to simple binaries—"“Islamist versus secular," "” “east versus west," "” “tribe versus tribe," "” “urban versus rural," "” “ethnic majority versus ethnic minority,"2”2 or "“old-regime officials versus newly empowered groups"”—many of these factors and others often interact to shape local and national dynamics. Since 2011, Libyans have endorsed a series of transitional arrangements in two national elections, a constitutional drafting assembly referendum, and local elections (Figure 1), but rates of participation have declined over time, and the intended tenure of all national level elected bodies have expired. The net result has been a de facto accrual of transitional leaders with competing, ever weaker claims of legitimacy. As their political struggle continues, allied militias are locked in a cycle of violent confrontation.

A brief conflict between Libyan rivals in 2014 and years of subsequent tension and mediation left a U.N.- and U.S.-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) with de jure control of key institutions in 2016, but the GNA'’s administrative and security weaknesses limited its effectiveness in the capital—Tripoli—and beyond. A rival interim government has operated in eastern Libya since 2014, with leaders of the House of Representatives (HOR) elected in 2014 operating from Tobruk. Leaders of the House of RepresentativesHOR leaders back the self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA)/Libyan Arab Armed Forces (LAAF) movement that has taken control overof most of Libya'’s east and south (Table 1). Inclusive U.N. mediation created the GNA, but the self-organized government in the east and the LNA have refused to endorse GNA leaders (Figure 2).

.

Among the range of external actors seeking to shape events in Libya, the United States has at times acted unilaterally and directly to protect its national security interests. Other countries have done the same. At the same time, the United States and other external parties have expressed support for multilateral initiatives to encourage compromise and consensus in support of Libya's ’s transition. The outbreak of LNA-GNA conflict in April 2019 derailed U.S.-backed U.N. plans to help Libyans end the extended post-2011 transition.

For the United States and other outsiders, key issues related to post-Qadhafi Libya have included

- transnational terrorist and criminal threats emanating from Libya;

- the security and continued export of Libyan oil and natural gas;

Libya' Libya’s role as a transit country for Europe-bound refugees and migrants;- the security of weapons stockpiles and unconventional weapons materials; and

- the country

'’s orientation in various region-wide political competitions.

For background on Libya'’s history and political development through 2011, see Appendix A.

|

|

|

Source: CRS. |

Libya and COVID-19

According toAppendix A.

1 Remarks of SRSG Ghassan Salamé to the United Nations Security Council, March 21, 2018. 2 Libya’s population includes an Arabic-speaking majority and Amazigh, Tuareg, and Tebu ethno-linguistic minorities.

Congressional Research Service

1

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

Figure 1. Libya’s Post-Qadhafi Transition, 2011-2020

Source: CRS.

Libya and COVID-19 On March 26, the U.N. Security Council expressed concern “at the possible impact of the COVID-19 pandemic” in Libya and called on parties to the conflict “to de-escalate the fighting urgently, to immediately cease hostilities and to ensure unhindered access of humanitarian aid throughout the country.” 3 In April, the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) judged that, “(OCHA), "Libya is at high risk of the virus spreading, given its levels of insecurity, weak health system and high numbers of migrants, refugees and internally displaced persons."3”4 Comprehensive data on the incidence of COVID-19 in Libya is lacking. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported on June 24 that Libyan National Centre for Disease Control data indicates that the number of COVID-19 cases in Libya has more than doubled since June 11, with 639 confirmed cases (mostly in the south).5 GNA officials and their eastern rivals have imposed different curfews and restrictions in their respective areas of control, and OCHA reports that the conflict and curfew measures "are hampering humanitarian access." humanitarian organizations and U.N. officials have reported that the conflict and curfew measures have hampered humanitarian access in some areas.

The capacity of the Libyan health system to provide critical care and the ability of authorities to control movements of people across the country'’s borders are limited. The U.S. government has , particularly in southern areas of the country. In March, the U.S. government made $6 million available to assist in the humanitarian response to COVID-19 in Libya, and U.S. Ambassador Richard Norland has addressed authorities across Libya to urge them to cease fighting, pay salaries, and facilitate flows of critical medical supplies.4 in the context of the pandemic.6 On April 10, Acting UNSMIL head Stephanie Williams said the continuation of thecontinued conflict was "reckless" and "“reckless” and “inhumane,"” adding that it is "“stretching the capacity of local authorities and the health infrastructure that is already decimated."

”

3 Permanent Mission of Germany to the U.N., U.N. Security Council Press Elements on UNSMIL, March 26, 2020. 4 Briefing by U.N. Secretary-General Spokesman Stephane Dujarric, April 1, 2020. 5 WHO Libya, Health Response to COVID-19 in Libya, Update # 9, June 25, 2020. 6 U.S. Embassy in Libya, A message from the United States to Libya’s leadership, March 27, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 8 Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

Status of Conflict and Diplomatic Efforts

Status of Conflict and Diplomatic Efforts

Key Issues in Libya'’s Troubled Transition

After years of rivalry and conflict, many Libyan actors make claims to some degree of political legitimacy and possess some means to assert themselves by force, but none have consolidated enough political support or military force to credibly provide national leadership or ensure durable security on a national scale.

In this context, key post-Qadhafi political issues for Libyans have included

-

the relative powers and roles of local, regional, and national government;

- the weakness of national government institutions and security forces;

- the role of Islam in political and social life;

- the involvement in politics and security of former regime officials; and

- the proper management of the country

'’s large energy reserves, related infrastructure, and revenues.

Factors that have shaped the relative degree of conflict, mutual accommodation, and reconciliation among Libyan factions since 2014 include

-

the relative ability of numerous factions to muster sufficient force or legitimacy

to assert dominance over each other;

- the inability of rival claimants to gain exclusive access to government funds controlled by the Central Bank or sovereign assets held overseas;

-

the U.N. arms embargo, U.N. mediation, and the application of U.N. sanctions;

- political, financial, and military interference by external actors; and

- the threats posed to Libyans and others by extremists, such as the Islamic State.

Some foreign observers have praised the role of the United Nations and some other third parties in promoting national reconciliation, but have argued that continuous and reinforcing efforts are needed to engage all Libyan actors with influence or direct control over security, natural resources, infrastructure, and sources of revenue if stability is to be achieved.57 Various Libyans have at times accused the U.N. and other third parties of unwarranted interference in Libya's ’s domestic affairs, particularly when they perceive outside interventions to undercut their interests or serve those of their rivals.6

8 Conflict Developments Since April 2019

Libyans have avoided full mobilization into civil war, but since April 2019 conflict has raged between rival coalitions of armed groups with thousands of personnel (Figure 2). Foreign powers arm parties to the conflict in violation of a U.N. arms embargo, providing weapons, advice, funding, and other support (see textbox below).79 Years of division and conflict already have weakened the Libyan health system'’s ability to mitigate COVID-19-related risks.

In April 2019, the LNA launched a surprise military campaign in western Libya, seeking to wrest control of Tripoli from the GNA and local militias. The LNA assault on Tripoli began on the eve of a planned U.N.-facilitated National Dialogue conference that had been intended to chart a new course for the country'’s political, economic, and security arrangements. The LNA and its backers have billed their campaigns since 2014 as an effort to save Libya from despotic criminal militias and Islamist extremists; critics paint the LNA as the abusive vanguard of a foreign conspiracy to install a pliant military dictatorship and suppress hard-won democratic self-determination.

Fighting since April 2019 has killed more than 2,200600 Libyans, including hundreds of civilians, and fighting in June 2020 displaced 28,000 people in western and central areas, bringing the total displaced to more than 401,000.10and has displaced more than 149,000 people in the capital region.8 LNA forces and partners control much of Libya'’s territory (see map in Table 1) and key oil production and export infrastructure directly or through local partners; GNA supporters and anti-LNA groups retain control of the capital and other key areas of the west (Figure 3). the northwest.

LNA forces made minimal gains in their assault on Tripoli, until support from Russian private military contractors with air defense equipment enabled some LNA advances in late 2019.

In November 2019, Turkey signed a maritime demarcation agreement with the GNA and activated new security cooperation arrangements.11 Turkish government infusions of air defense support, drones, uniformed advisors, equipment, weapons, and Syrian militia fightersand weapons, bolstered GNA defenses through January 2020, reestablishing stalemate conditions.912 According to U.S. officials, both sides have recruited and deployed Syrian militia fighters.13

Rahman Alageli, Emadeddin Badi, Mohamed Eljarh, and Valerie Stocker, The Development of Libyan Armed Groups Since 2014: Community Dynamics and Economic Interests, Chatham House (UK), March 17, 2020.

10 Non-governmental organization and International Organization for Migration estimates. 11 The Turkey-GNA maritime agreement could discourage private sector involvement in Eastern Mediterranean energy exploration and pipelines and appears to be further complicatingfurther complicate regional actors'’ security calculations. Selcan Hacaoglu and Firat Kozok, “Turkish Offshore Gas Deal with Libya Upsets Mediterranean Boundaries,” Bloomberg, December 6, 2019; Soner Cagaptay and Ben Fishman, “Turkey Pivots to Tripoli: Implications for Libya’s Civil War and U.S. Policy,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 19, 2019; and, International Crisis Group, Turkey Wades into Libya’s Troubled Waters, April 30, 2020. 12 See CRS Report R44000, Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations In Brief, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas. 13 Frederic Wehrey, “Among the Syrian Militiamen of Turkey’s Intervention in Libya,” New York Review of Books: NYRDaily (blog), January 23, 2020; State Department Briefing on Russian Engagement in the Middle East, May 7, 2020; and Kareem Fahim and Zakaria Zakaria, “These Syrian militiamen were foes in their civil war. Now they are battling each other in Libya,” Washington Post, June 25, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

4

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

In January 2020, renewed multilateral diplomatic initiatives sought to achieve a ceasefire between Libyan combatants as a precursor to restarting political reconciliation efforts. Russia and Turkey engineered a temporary truce, but did not achieve a formal ceasefire or comprehensive settlement.

Table 1. Libya Map and Facts

Land Area: 1.76 mil ion security calculations.10

In January 2020, renewed multilateral diplomatic initiatives sought to achieve a ceasefire between Libyan combatants as a precursor to restarting political reconciliation efforts. Russia and Turkey engineered a temporary truce on January 12, but did not achieve a formal ceasefire or comprehensive settlement. Meeting in Berlin, Germany, on January 19, the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council along with other key foreign actors made joint commitments with a goal of durably ending the conflict. Participants consulted with leading Libyan figures in Berlin, but GNA and LNA leaders did not commit to a ceasefire or formally sign the 55-point Berlin Communiqué (see textbox below). Notable aspects of the agreement include a call for a durable cessation of hostilities, a pledge of mutual respect for the U.N. arms embargo, and a set of shared post-conflict governance, economic, and security goals.

| |||

Population: 6,890,535 (July 2020 est., in 2015 the U.N. estimated 12% were immigrants), ~49% <25 years old GDP PPP: $61.97 Budget: $27.1 Public Debt: $69.8 Foreign Exchange Reserves: $77 Oil and natural gas reserves: 48.36 |

Source: Congressional Research Service using data from U.S. State Department, Esri, United Nations, and Google Maps. Country data from CIA World Factbook, Libyan government, United Nations, AprilJune 2020.

Congressional Research Service

5

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

Meeting in Berlin, Germany, on January 19, the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council along with other key foreign actors made joint commitments with a goal of durably ending the conflict. Participants consulted with leading Libyan figures in Berlin, but GNA and LNA leaders did not commit to a ceasefire or formally sign the 55-point Berlin Communiqué (see text box below). Notable aspects of the agreement include a call for a durable cessation of hostilities, a pledge of mutual respect for the U.N. arms embargo, and a set of shared post-conflict governance, economic, and security goals.

2020.

As of April 13, 2020 |

|

|

Source: Prepared by CRS using publicly available sources. |

Berlin Communiqué: Select Commitments Berlin Communiqué: Select Commitments Meeting in Berlin, the governments of Algeria, China, Egypt, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, Turkey, the Republic of the Congo, United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States, together with representatives of the United Nations, the African Union, the European Union, and the Arab League, made several pledges, including:

|

To establish a ceasefire and operationalize the security aspects of the Berlin agreement, the GNA and LNA were asked each to nominate five appointees to a U.N.-sponsored "“5+5"” Military Committee. U.N. SRSG and UNSMIL head Ghassan Salamé facilitated initial rounds of 5+5 talks but resigned in March as mediation faltered (see textbox below). U.N. officials hosted an initial round of political talks, but the High State Council (HSC) and HOR set preconditions on their delegates'delegates’ participation that limited discussions.1114 Economic talks beganwere held in Cairo. U.N. and 14 UNSMIL’s plans for the political dialogue call for 40 delegates be drawn from among the membership of the High

Congressional Research Service

6

link to page 9 link to page 9 Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

in Cairo in February.

In the wake of the agreement, fighting resumed in Tripoli's southern suburbs, in areas west of the capital, and near Abu Qurayn, south of the city of Misrata. U.N. and U.S. officials have condemned post-Berlin weapons shipments to both sides and have rejected the shutdown of oil and other infrastructure. Amid a flurry of diplomacy, an International Follow-Up Committee continues to meet, bringing external parties together for additional consultations.

The United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL)

shutdown of oil and other infrastructure in areas under LNA control. Since early March, U.S. and European officials have engaged leading Libyan figures in attempts to engineer a ceasefire. Khalifa Haftar and GNA Interior Minister Fathi Bashaga visited Europe for related discussions. Both LNA leaders and their rivals may struggle to maintain the coherence and unity of their coalitions if conditions worsen for civilians or if international actors intervene more dramatically.

Pressures created by the COVID-19 pandemic have the potential to influence the calculations of Libyan combatants. On March 26, the U.N. Security Council expressed concern "at the significant escalation of hostilities on the ground" and "at the possible impact of the COVID-19 pandemic."12 The Council called on parties to the conflict "to de-escalate the fighting urgently, to immediately cease hostilities and to ensure unhindered access of humanitarian aid throughout the country."13 U.S. Permanent Representative to the U.N. Ambassador Kelly Craft said, "This is not the time for violence, but rather for all actors to immediately suspend military operations, reject toxic foreign interference, and improve the ability of health authorities to combat this global pandemic."14

The U.N. Security Council created UNSMIL as an integrated special political mission in September 2011 (Resolution 2009) 15 In June 2017, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres named Ghassan Salamé of Lebanon as his Special Representative (SRSG) and head of UNSMIL. After political talks stalled and arms shipments to Libya continued, Salamé resigned on March 2, 2020, citing the negative effects of stress on his health. |

Political Dynamics and Considerations

At first glance, the conflict in Libya appears to pit two primary factions and their various foreign and local backers against each other in a relatively straightforward contest for control over territory, resources, and the organs of state power. However, beneath the surface, complicated local concerns, foreign agendas, personal grudges, ethnic and tribal identities, profit motives, and ideological rivalries shape politics and security. The principal Libyan coalitions each suffer from internal divisions and political legitimacy deficits exacerbated by the extended, fractious nature of the transition period. Foreign powers have manipulated Libyans' divisions and needs to pursue their own goals, raising the transnational stakes of intra-Libyan conflicts. These factors have repeatedly complicated negotiations, undermined security, and frustrated mediation efforts.

Past attempts to achieve consensus and motivate Libyan leaders to drop objections to the completion of the transition have been unsuccessful. The key outstanding issues include the security sector leadership, terms for government decentralization, the representation of various groups in national government bodies, and mechanisms for managing state finances, distributing energy sector proceeds, and ensuring adequate service delivery. Differences over security arrangements and their intersection with politics have proven particularly intractable.

The Roles and Concerns of External Actors in Libya The Roles and Concerns of External Actors in Libya

Several external actors seek to influence Libya The governments of UAE and Egypt oppose Turkey’s intervention and express concern about Islamist armed groups and Muslim Brotherhood figures operating among some anti-LNA forces.29 Turkish officials describe Haftar as a “putschist” and directly criticize governments backing the LNA.30 The governments of neighboring Algeria and Tunisia have called for an end to external intervention in Libya, and for an intra-Libyan political process to resolve the conflict, although some individual politicians in both countries appear supportive of one side or the other. Across the Mediterranean, European countries have shared concerns about the transit of migrants from Libya and the presence in Libya of terrorist groups. France, the United Kingdom, and Italy each support the implementation of the Berlin Communiqué and continue to engage with Libyan parties in support of Resolution 2510, but have appeared to differ in their 34 Russia had close ties to the Qadhafi government and has been more active in cultivating relationships with Libyan

actors since 2014. Russian officials portray their efforts as even-handed and open to all sides in Libya, but their ties with Haftar and the LNA appear to be more robust. These ties may serve a range of purposes, including addressing Russian counterterrorism concerns, restoring Russian military ties to Libya, and balancing Western European and U.S. influence. |

Since April 2019, western Libya-based militia forces have helped GNA authorities resist the LNA's assault, but these militias'U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) continues to express concern over Russian military and mercenary activity in Libya (see “Counterterrorism Operations and Strategic Competition” below).

24 Joint Declaration, June 25, 2020. 25 UAE Minister of State Anwar Gargash, Twitter (@AnwarGargash), May 1, 2019, 10:45 PM. 26 Office of the Presidential Spokesman, Facebook, May 9, 2019. 27 Reuters, “Turkish Military Units Moving to Libya, Erdogan Says,” January 5, 2020. 28 Reuters, “Qatar foreign Minister Says Libya’s Haftar Obstructing Dialogue Efforts,” April 16, 2019. 29 WAM (UAE), “UAE participates in Arab League meeting on Libya, GERD,” June 24, 2020. 30 Reuters, “Turkey vows more support to secure gains in Libya conflict,” Reuters, June 4, 2020. 31 Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian, “France Is in Libya to Combat Terrorism,” May 2, 2019. 32 Reuters, “France ‘will not tolerate’ Turkey's role in Libya, Macron says,” Reuters, June 22, 2020; and, “FM Çavuşoğlu slams French President Macron for remarks on Libya” Daily Sabah (Istanbul), June 25, 2020. 33 Francesca Sforza, “Di Maio’s Move: ‘A European Plan To Rebuild Libya,’” La Stampa (Turin), June 25, 2020. 34 “Khalifa Haftar Can Still Be Part of Future Libya Government, Says Hunt,” Guardian (UK), May 7, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

9

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

Political Dynamics and Considerations At first glance, the conflict in Libya appears to pit two primary factions and their various foreign and local backers against each other in a relatively straightforward contest for control over territory, resources, and the organs of state power. However, beneath the surface, complicated local concerns, foreign agendas, personal grudges, ethnic and tribal identities, profit motives, and ideological rivalries shape politics and security. The principal Libyan coalitions each suffer from internal divisions and political legitimacy deficits exacerbated by the extended, fractious nature of the transition period. Foreign powers have manipulated Libyans’ divisions and needs to pursue their own goals, raising the transnational stakes of intra-Libyan conflicts. These factors have repeatedly complicated negotiations, undermined security, and frustrated mediation efforts.

Past attempts to achieve consensus and motivate Libyan leaders to drop objections to the completion of the transition have been unsuccessful. The key outstanding issues include the security sector leadership, terms for government decentralization, the representation of various groups in national government bodies, and mechanisms for managing state finances, distributing energy sector proceeds, and ensuring adequate service delivery. Differences over security arrangements and their intersection with politics have proven particularly intractable. The threat of more intense, foreign intervention-fueled conflict could alter some Libyans’ calculations and motivate them to deescalate. At the same, the logic of foreign competition and parties’ insistence on nonnegotiable red lines could preclude progress and drive conflict toward de facto partition.

Since April 2019, western Libya-based militia forces have helped GNA authorities resist the LNA’s assault, but these militias’ reluctance to relinquish weaponry and abandon lucrative corruption schemes was one of the biggest obstacles to the GNA'’s efficient operation and authority prior to the recent conflict.2535 GNA figures such as Interior Minister Bashaga had made partial progress in reining in some militia actors during 2018 and 2019. However, resumption of conflict has re-empowered and emboldened many local armed groups, some of whom question the GNA'’s authority, reject the idea of compromise with the LNA, and challenge Bashaga'’s authority.26 Turkish support36 Turkey has stiffened the GNA's resistance, but it also has amplified the concerns of Egypt and the UAE, who view Turkey as supporting Libyan Muslim Brotherhood members.

’s resistance, but amplified Emirati and Egyptian concerns.

The LNA/LAAF and Khalifa Haftar have sought to harness the shared security and political concerns of a diverse coalition of supporters since 2014, but the unity of their movement remains in question.2737 Haftar'’s authoritarian leadership style and political ambitions alienate some Libyans, and forces under his command stand accused of several violations of international humanitarian law. Haftar and LNA officials do not distinguish between their opponents, suggesting that their enemies are "“terrorist militias and criminal gangs."28”38 Salafist and tribal militias participate in LNA operations, as do mercenaries from Sudan, Chad, and other countries.

The LNA’s battlefield setbacks in 2020 may lead to recriminations and divisions, though further GNA advances toward eastern Libya could generate some solidarity among eastern factions.

Forces opposed to the LNA channel nationalist sentiment and appeal to the anti-authoritarian principles of 2011 uprising to motivate their forces and recruit supporters. Some Islamist actors, including Muslim Brotherhood supporters, actively oppose the LNA, but they do not exclusively control the overall anti-LNA movement or the GNA. The locally organized nature of the opposition to the LNA creates potential fault lines between armed groups. Political leaders aligned with Haftar in eastern Libya claim political legitimacy stemming from Libya's 2014 election, but the LNA has stifled most political opposition in areas under its control. Members of the HOR—the national legislature last elected in 2014—have realigned themselves over time, with dozens of members active outside LNA territory and opposed to pro-Haftar

35 See Wolfram Lacher and Alaa al-Idrissi, “Capital of Militias: Tripoli’s Armed Groups Capture the Libyan State,” Small Arms Survey Briefing Paper, June 2018.

36 Xinhua (China), “Libya’s Interior Minister Says Armed Groups Obstruct Security Services,” February 24, 2020. 37 David Kirkpatrick, “A Police State with an Islamist Twist: Inside Hifter’s Libya,” New York Times, February 20, 2020.

38 Statements by LNA Spokesman Ahmed al Mismari, July 17, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

10

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

control the overall anti-LNA movement or the GNA. LNA information operations often describe former adversaries of the LNA’s campaigns in Benghazi and Derna as extremists. The locally organized nature of anti-LNA forces creates potential fault lines between them. Tribal politics shape both coalitions, but remain particularly relevant in Libya’s south and east.39

Political leaders aligned with Haftar in eastern Libya claim political legitimacy stemming from Libya’s 2014 election, but the LNA has stifled most political opposition in areas under its control. In April 2020, Haftar gave a speech asserting a popular mandate for political control over the country, but has since acknowledged the enduring relevance of the interim government and the HOR. Egypt has stated its view that the HOR could legitimately invite the Egyptian military to intervene in Libya if necessary.40 Members of the HOR have realigned themselves since 2014, with dozens of members active outside LNA territory and opposed to pro-LNA HOR leaders.

HOR leaders.

Oil, Fiscal Challenges, and Institutional Rivalry

Oil Cutoff and Market Forces Create Fiscal Pressure

Conflict and instability in Libya have taken a severe toll on the country'’s economy and weakened its fiscal stability and reserves since 2011. As of 2018, the U.S. government estimated that Libya had the largest proven crude oil reserves in Africa and the ninth largest globally. As of October 2019, the hydrocarbon sector supplied 91% of the government'’s fiscal revenue, and, according to the World Bank, were "“just enough to cover the high wage bill and subsidies."29 In January”41 In May 2020, UNSMIL described the situation as “increasingly tenuous,”42 and reported that, “with a looming budget deficit of 26 billion dinars ($18.5 billion at official rate) in 2020, the Central Bank of Libya has imposed austerity measures including limits on foreign exchange. All of this has led to a loss of income, food shortages and price spikes, including supply chain disruptions.”43

UNSMIL reported that since April 2019, "growth in gross domestic product has been cut by two thirds owing to the conflict."30

Oil dependence makes state revenue vulnerable to energy market changes and conflict-related disruptions. Nevertheless, state financial obligations to the population have increased since 2011, with public spending on salaries, imports, and subsidies all having expanded.3144 As of 2018, Libyan officials had identified more than 1.75 million state employees (equivalent to more than 25% of the population) and estimated that salaries then consumed nearly 60% of the state budget.3245 Government payments to civilians and militia members across the country have continued after conflict resumed in April 2019, and, until January 2020, Central Bank authorities had simultaneously paid salaries for forces and state employees on both sides of the conflict. Salary payments have slowed since in light of the curtailment of oil exportexports (see below).

Since 2011, oil production disruptions and global market forces intermittently have caused oil exports and/or revenue to plummet, with follow-on negative effects for state finances.33 Periods of fighting near the central oil crescent region (see map in Table 1)46 Periods

39 See Alison Pargeter, “Haftar, Tribal Power, and the Battle for Libya,” War on the Rocks (online), May 15, 2020. 40 Mahmoud Mourad, “Egypt has a legitimate right to intervene in Libya, Sisi says,” Reuters, June 20, 2020. 41 World Bank, “Macro Poverty Outlook—Libya,” October 2019. 42 U.N. Document S/2020/360, Report of the Secretary-General on UNSMIL, May 5, 2020. 43 U.N. Document S/2020/41, Report of the Secretary-General on UNSMIL, January 15, 2020. 44 Salaries and subsidies reportedly consumed 93% of the state budget as of September 2016. Statement of SRSG Martin Kobler to the United Nations Security Council, September 13, 2016.

45 “Serraj Spokesperson Promises 2018 Budget Details Will Be Revealed Next Week,” Libya Herald, April 9, 2018. 46 E.g., International Monetary Fund, “Arab Countries in Transition: Economic Outlook and Key Challenges,” Oct. 9, 2014; Sudarsan Raghavan “As oil Output Falls, Libya is on the Verge of Economic Collapse,” Washington Post, Apr. 16, 2016; and World Bank, “Libya’s Economic Outlook–April 2017 and Macro Poverty Outlook—Libya,” Oct. 2019.

Congressional Research Service

11

link to page 9 Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

of fighting near the central oil crescent region (see map in Table 1) and intermittent shutdowns of pipelines by militias, terrorist attacks, and labor and property disputes each have generated temporary disruptions and production declines at different times. In January 2020, the LNA and entities in territory under its control instituted a nearly complete cut-offcutoff of national oil production, sending a shockwave through the country'’s public finances. Oil output declined from more than 1 million barrels per day to less than 100,000 barrels per day.

The withdrawal of LNA forces from northwestern Libya was followed by a brief resumption of output from southwestern Libya, but production there has remained disrupted.

To cope, Libyan officials have drawn on state financial reserves, which had rebounded from previous shocks thanks to oil revenue and foreign currency exchange taxes. The GNA removed national fuel subsidies in October 2019, but serious challenges remain, and public salary payments have been limited. Drastic declineDeclines in global oil prices since February 2020 suggestssuggest that even under conditions of resumed oil production, prevailing market conditions could still reduce revenue and amplify fiscal pressure. The Finance Ministry projected in February that reserves could drop to as low as $63 billion by June 2020.34 In March, the Libyan National Oil Corporation (NOC)47 In June, U.S. Ambassador to Libya Richard Norland estimated revenue losses since mid-January at $3.5 billion, "with daily losses at more than $1.1 million."35more than $5 billion.48 In March, the GNA approved a $27.2 billion budget for 2020.

Rivalries Persist Among Key Libyan Institutions

Disputes over leadership of key national institutions such as the Central Bank, National Oil Corporation (NOC), and Libya'’s sovereign wealth fund—the Libya Investment Authority (LIA)—and its subsidiaries continue. These opaque but consequential rivalries have reflected the country'country’s underlying political competition over time and have created financial risks for the state that will likely outlast the current conflict. U.N. Security Council Resolution 2509 (2020) expresses "“concern about activities which could damage the integrity and unity of Libyan State financial institutions and the National Oil Corporation (NOC),"” and stresses "“the need for the Government of National Accord to exercise sole and effective oversight over the National Oil Corporation, the Central Bank of Libya, and the Libyan Investment Authority as a matter of urgency, without prejudice to future constitutional arrangements pursuant to the Libyan Political Agreement."

”

Central Bank of Libya. Central Bank officials in Tripoli and the eastern city of Bayda have become embroiled in the rivalry between the GNA Presidency Council and the HOR, with the United States and other backers of the GNA Presidency Council recognizing the Tripoli-based Central Bank as legitimate.3649 In May 2016, the Bayda-based branch of the bank moved to issue its own currency and accessed secured assets held at the branch, leading the U.S. government to warn against actions not authorized by the GNA Presidency Council that could undermine confidence among Libyan consumers and international trading partners.3750 When the HOR nominated a replacement for Tripoli-based Central Bank Chairman Sadiq al Kabir in December 2017, the High State Council (HSC) protested the nomination, noting that it hadn'’t been consulted pursuant to Article 15 of the 2015 Libyan Political Agreement (LPA), which provides for appointments to select sovereign positions. UNSMIL also rejected the move, but the HOR

47 “Conflict Could Drive Libya Currency Reserves to 2016 Levels,” Bloomberg News, March 9, 2020 48 State Department, Special Briefing via Telephone with Richard Norland, U.S. Ambassador to Libya, June 4, 2020. 49 Ministerial Meeting for Libya Joint Communiqué, May 16, 2016. 50 See U.S. Embassy Libya, Statement on Central Bank of Libya, May 25, 2016; and Hassan Morajea and Tamer El-Ghobashy, “Libya’s Central Bank Needs Money Stashed in a Safe; Problem Is, Officials Don’t Have the Code,” Wall Street Journal, May 13, 2016.

Congressional Research Service

12

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

confirmed Mohammed Shukri as head of the Bayda-based branch in January 2018. HOR leaders have since asserted their view that Al Kabir'’s continued tenure is illegitimate.

The Tripoli Central Bank invalidated Bayda-issued dinar coins in late 2017, but Bayda branch officials continued to print paper currency and issue loans to the eastern Libya-based rival government through 2019. In January 2020, UNSMIL reported that "“while debt directly managed by the Central Bank of Libya decreased to 56 billion Libyan dinars (~$39.5 billion), that of the parallel non-recognized Central Bank branch in eastern Libya increased to 43 billion Libyan dinars (~$30.3 billion), resulting in an overall gross domestic product-to-debt ratio of 150 per cent."38”51 In March 2020, the Bayda branch said future borrowing by the eastern government would be limited to loans to pay state employee salaries.3952 GNA officials on April 1 restated their willingness to proceed with internationally backed efforts to unify the Central Bank institutions and to audit and reconcile accounts. Nevertheless, in May, UNSMIL reported to the Security Council that, “lack of cooperation on the part of the Libyan authorities in facilitating the international audit review of the structure of the Central Bank also narrowed opportunities for the unification of that bank.”53and to audit and reconcile accounts. U.S. officials are encouraging Libyan Central Bank leaders to meet, unify the institution, and proceed with an internationally supported audit to increase transparency and public confidence in state finances.40

54

National Oil CorporationCorporation. Disputes involving the National Oil Corporation (NOC)NOC also have ebbed and flowed since early 2016. In April 2016, the U.N. Security Council blacklisted an oil tanker that had taken on hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil sold by national oil company officials operating in the east, but the sanctions were withdrawn at the GNA Presidency Council'’s request. Since March 2014, the U.N. Security Council has approved third-party military operations to interdict ships named by the U.N. Libya Sanctions Committee as being suspected of carrying unauthorized oil exports. Tripoli-based NOC Chairman Mustafa Sanalla has called for the NOC to be depoliticized and wrote in June 2017 that he and his colleagues "“intend to remain neutral until there is a single legitimate government we can submit to."41

”55

In September 2019, authorities in eastern Libya attempted to assert control over local operations of the Brega Petroleum Marketing Company, which distributes fuel in country, claiming that the company was not making sufficient jet fuel available. NOC Chairman Sanalla countered that "“fuel supply to the Eastern and Central regions is more than adequate for civilian purposes. The real motive behind this attempt is to set up a new illegitimate entity for the illegal export of oil from Libya."42”56 In response to the eastern authorities'’ moves, the U.S. government, France, Germany, Italy, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom said

We fully support Libya's National Oil Corporation (NOC) as the country's sole independent, legitimate and nonpartisan oil company. Now is the time to consolidate national economic institutions rather than break them apart. For the sake of Libya's political and economic stability, and the well-being of all its citizens, we

We fully support Libya’s National Oil Corporation (NOC) as the country’s sole independent, legitimate and nonpartisan oil company. Now is the time to consolidate national economic institutions rather than break them apart. For the sake of Libya’s

51 U.N. Document S/2020/41, Report of the Secretary-General on UNSMIL, January 15, 2020. 52 Reuters, “East Libyan central Bank Says It Will Not Lend to Parallel Govt Any More,” March 11, 2020. 53 U.N. Document S/2020/360, Report of the Secretary-General on UNSMIL, May 5, 2020. 54 U.S. Ambassador Richard Norland comments in Al Wasat (Libya), “Exclusive Q&A: U.S. Ambassador to Libya discusses Efforts to End Fighting, Coronavirus Response,” April 5, 2020.

55 Mustafa Sanalla, “How to Save Libya From Itself? Protect Its Oil from Its Politics,” New York Times, June 19, 2017. 56 Carla Sertin, “Partitioning Oil Sector Will Put Libya’s Integrity ‘at Grave Risk’: NOC Chairman,” Oil and Gas Middle East, September 22, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

13

link to page 36 Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

political and economic stability, and the well-being of all its citizens, we exclusively support the NOC and its crucial role on behalf of all Libyans.43

57

In March 2020, interim government officials in eastern Libya imported fuel from the United Arab Emirates outside the channel of the NOC, in light of disruptions to domestic refining because of the LNA-supported shutdown of national oil production.

Libya Investment Authority. A long-simmering dispute between rival board members and chairmen has paralyzed the Libya Investment Authority (LIA)LIA—Libya'’s sovereign wealth fund—for several years.4458 The LIA's ’s assets reportedly exceed $60 billion, much of which remain frozen pursuant to U.N. Security Council Resolutions 1970 and 1973 (2011), as modified by Resolution 2009 (2011). Legal proceedings in several jurisdictions have addressed disputes over the management of LIA assets and payment of fees. Libyan courts at times have intervened to overturn appointments and authorizations of LIA officials. U.N. reporting notes that Tripoli-based LIA officials have asserted control of the management of LIA assets, but the rival eastern government "“has a parallel board of trustees, which in turn appointed a board of directors."45”59 The U.N. Sanctions Committee panel of experts recommended in December 2019 that Member States be directed to freeze the assets of LIA subsidiaries, but LIA officials report that the Sanctions Committee has declined to alter its implementation guidance regarding subsidiaries.46

60 In March 2020, a court in the United Kingdom recognized Ali Mahmoud Hassan Mohamed as the LIA’s lawful chairman in the view of U.K. law, a decision that may have implications in other jurisdictions.61 Sanctions and Arms Embargo Provisions

U.N. Security Council Measures

Prior to and following the outbreak of conflict in Libya in 2011, the United Nations, the United States, and other actors adopted a range of sanctions measures intended to convince the Qadhafi government to end its military campaign against opposition forces and civilians. The measures also sought to dissuade third parties from providing arms or facilitating financial transactions for the benefit of Libyan combatants. U.N. Security Council Resolution 1970 established a travel ban on Qadhafi government leaders, placed an embargo on the unauthorized provision of arms to Libya, and froze certain Libyan state assets.

After Qadhafi'’s death in October 2011 (Appendix A), U.N. and U.S. sanctions measures were modified but remained focused on preventing former Qadhafi government figures from accessing Libyan state funds and undermining Libya'’s transition. Asset-freeze measures changed to give Libya'Libya’s new transitional leaders access to some state resources, but some limitations also remained in place to ensure that transitional authorities transparently and legitimately administered funds. U.S. Treasury officials issued a series of general licenses that gradually unblocked most Libyan state property and allowed for transactions with Libyan Central Bank and Libyan National Oil Company. U.N. arms embargo provisions were modified over time, but

57 Joint Statement on Libya’s National Oil Corporation (NOC), September 22, 2019. 58 Libya Herald, “Tripoli and Malta LIA Handover to PC/GNA Interim Steering Committee,” September 9, 2016. 59 Final Report, Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to resolution 1973 (2011), U.N. Document S/2019/914. 60 Final Report, Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to resolution 1973 (2011), U.N. Document S/2019/914; and, Sami Zaptia, “LIA seeks Minor Changes to UN Asset Freeze to Mitigate Losses,” Libya Herald, March 9, 2020. 61 Sami Zaptia, UK Court Confirms Ali Mahmoud Hassan Mohamed as lawful chairman of the Libyan Investment Authority, Libya Herald, March 25, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

14

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

Libyan National Oil Company. U.N. arms embargo provisions were modified over time, but remained in place in a bid to ensure that the transitional government had authorized weapons transfers to Libya.47

62

When fighting broke out among Libyan factions in 2014, the Security Council moved to expand the scope of the modified sanctions provisions to allow for the targeting of actors who were contributing to the conflict. Resolution 2174, adopted in August 2014, authorized the placement of U.N. financial and travel sanctions on individuals and entities found to be "“engaging in or providing support for other acts that threaten the peace, stability or security of Libya, or obstruct or undermine the successful completion of its political transition."” Resolution 2174 strengthened the arms embargo provisions by requiring advance approval by the sanctions committee for transfers of arms. Resolution 2213, adopted in March 2015, expanded the scope of sanctionable activities related to the standards articulated in Resolution 2174. At present, modified sanctions, arms embargo, and oil sale related provisions of Resolutions 1970, 2009, 2095, 2174, 2362, 2441, 2473, and 24732526 remain in force. A U.N. sanctions committee oversees implementation.48

63

The U.N. Security Council has recognized the GNA as Libya'’s governing authority since December 2015, in an effort to confer international legitimacy on its leaders and encourage unification efforts. Resolutions 2259 (2015), 2278 (2016), 2362 (2017), and 2441 (2018) expressed support for the GNA as the sole legitimate government of Libya and urged Member States to comply with Security Council efforts to enforce asset freeze, travel ban, and arms embargo measures. These resolutions further authorized the provision of security assistance to the GNA for counterterrorism purposes. Resolution 2509 (2020) does not refer to the GNA as Libya's ’s sole legitimate government, but calls on Member States "“to cease support to and official contact with parallel institutions outside of the [2015] Libyan Political Agreement."

”

U.S. and European Sanctions

In February 2011, President Barack Obama issued Executive Order 13566, declaring a national emergency and blocking the property under U.S. jurisdiction of the government of Libya, Qadhafi, his family, and other designated individuals. The Obama Administration modified U.S. sanctions measures in support of the Libya Political Agreement (LPA) in April 2016. The amendments (issued in Executive Order 13726) were based on President Obama'’s finding that

the ongoing violence in Libya, including attacks by armed groups against Libyan s finding that

the ongoing violence in Libya, including attacks by armed groups against Libyan state facilities, foreign missions in Libya, and critical infrastructure, as well as human facilities, foreign missions in Libya, and critical infrastructure, as well as human rights abuses, violations of the arms embargo imposed by United Nations Security abuses, violations of the arms embargo imposed by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1970 (2011), and misappropriation of Libya's Libya’s natural resources threaten the peace, security, stability, sovereignty, democratic transition, and territorial integrity of sovereignty, democratic transition, and territorial integrity of Libya and thereby constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States.

Under the modified executive order, property under U.S. jurisdiction may be blocked and entry to the United States may be prohibited for individuals and entities found to be engaging or to have engaged in a range of actions, including threatening the peace, stability, or security of Libya and

62 Resolution 2009 of 2011 allowed an exception to the arms embargo for the supply, sale, or transfer to Libya of “arms and related materiel of all types, including technical assistance, training, financial and other assistance, intended solely for security or disarmament assistance to the Libyan authorities and notified to the Committee in advance and in the absence of a negative decision by the Committee within five working days of such a notification.” Resolution 2095 (2013) further exempted the supply of nonlethal military equipment, training, and financial assistance for security and disarmament assistance to the Libyan government from notification requirements under the embargo.

63 See https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/1970.

Congressional Research Service

15

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

obstructing, undermining, delaying, or impeding the adoption of or transfer of power to a Government of National Accord or successor government. The Obama Administration placed related sanctions on former GNC government prime minister Khalifa Ghwell and HOR leader Aqilah Issa SalihSaleh in April and May 2016 for obstructing the implementation of the LPA.

President Trump has extended the national emergency with respect to Libya, most recently for one year on February 20, 2020.4964 In February 2018, the Trump Administration announced sanctions targeting six individuals accused of illicit oil smuggling from Libya and a number of related entities.5065 In September 2018, the Administration placed sanctions on Ibrahim Jadhran, an eastern Libya-based militia commander responsible for several attacks on oil facilities in central Libya,5166 and, in November 2018, placed sanctions on Salah Badi, a western Libya-based militia commander responsible for attacks on Tripoli.52

67

The European Union (EU) consolidated its sanctions on Libya in January 2016.5368 In April 2016, the EU imposed sanctions on SalihSaleh, Ghwell, and GNC official Nuri Abu Sahmain. The EU last extended its sanctions for six months in March 2020.69

extended its sanctions for six months in March 2020.54

Arms Embargo Enforcement and Violations

Under current U.N. Security Council resolutions, arms transfers to Libya may occur provided the GNA approves and the transfer is notified to the U.N. panel established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 1970. In practice, unauthorized arms transfers to Libya continue to take place, as documented in reports produced by the Resolution 1970 Sanctions Committee and its Panel of Experts. The Panel of Experts report released in December 2019 documents lethal and nonlethal foreign support in violation of the arms embargo for armed groups from across Libya.55 Resolution 2509 extended the Panel of Experts' mandate to March 15, 2021. In June 2016, the Security Council adopted Resolution 2292 authorizing member states to assist in the maritime enforcement of the arms embargo and has since amended and extended that authority, most recently through June 10, 2020, under Resolution 2473.

The EU previously authorized its migration-focused naval mission in the Mediterranean to assist in arms embargo enforcement, but later reduced both the migration and arms embargo focused aspects of the operation amid dissent over migration issues among member states. The EU relaunched maritime security operations in support of arms embargo enforcement in the eastern Mediterranean under the new Operation EUNAVFOR MED IRINI on April 1, 2020.56 U.S. Ambassador to Libya Richard Norland said in April 2020 that the United States supports the operation and understands that it "has not only a maritime dimension but also a satellite surveillance dimension so it should be possible to monitor arms embargo violations, not only on the maritime borders, but also across Libya's land borders as well."57

U.S. Travel Restrictions on Libyan Nationals U.S. Travel Restrictions on Libyan Nationals

Libya is among the countries identified in Executive Order 13780 of March 2017, which restricts the entry of nationals of certain countries to the United States, with some exceptions. In September 2017, the Trump Administration issued further guidance on the entry restrictions, and suspended the entry to the United States of Libyan nationals as immigrants and non-immigrants in business (B-1), tourist (B-2), and business/tourist (B-1/B-2) visa classes.

Although it is an important partner, 71

In April 2018, President Trump issued a new proclamation updating the September 2017 actions, and stated

Though remaining deficient, the State of Libya (Libya) is taking initial steps to improve its practices. DHS and State are currently working with the Government of Libya, which has designated a senior official in its Ministry of Foreign Affairs to serve as a central focal point for working with the United States. DHS and State presented Libya with a list of measures it can implement to rectify its deficiencies, and it has committed to do so. Despite this progress, Libya remains deficient in its performance against the

64 Notice of February 20, 2020: Continuation of the National Emergency with Respect to Libya, FR Doc. 2020-03810. 65 U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions International Network Smuggling Oil from Libya to Europe” February 26, 2018.

66 U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Militia Leader Responsible for Multiple Attacks on Libyan Oil Facilities,” September 18, 2018. 67 U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Militia Leader Responsible for Multiple Attacks on Libyan Capital,” November 19, 2018. 68 EU Council Regulation (EU) 2016/44, Concerning Restrictive Measures in View of the Situation in Libya and Repealing Regulation (EU) No 204/2011, January 18, 2016.

69 European Council, Council Decision (CFSP) 2020/458, March 27, 2020. 70 The White House, “Fact Sheet: Proclamation on Enhancing Vetting Capabilities and Processes for Detecting Attempted Entry into the United States by Terrorists or Other Public-Safety Threats,” September 24, 2017.

71 Ibid.

Congressional Research Service

16

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

72

President Trump left the restrictions on Libya in place in January 2020, acting to impose tailored entry restrictions and limitations on nationals from six additional countries. The United States issued 1,445 B-1, B-2, and B1/B-2 visas to Libyan nationals in FY2016, which was approximately 62% of the total number of U.S. visas issued for Libyans that year. |

Human Rights and Migration

Non-State Actors Violate Human Rights with Impunity

Average Libyans have faced tenuous economic and security circumstances for much of the post-2011 period amid unreliable state salary and subsidy support, weak state service provision and law enforcement, inflationary pressures, and hard currency shortages. Economic hardship has amplified the negative effects of deteriorations in local security and the weakening of the rule of law. In March 2018, then-SRSG Salamé tolddecried to the U.N. Security Council decried what he described as "“an economic system of predation"” and "“plundering."” The U.N. Panel of Experts documented indiscriminate use of explosive ordnance, human trafficking and migrant smuggling, abuses in detention centers, assassinations, and kidnapping among other human rights abuses in its December 2019 report.

The 2019 State Department report on human rights conditions in Libya notes the GNA's "’s “limited effective control over security forces"” (some of which are deputized militias) and concludes that, in 2019,

Impunity from prosecution was a severe and pervasive problem. Divisions in 2019,

Impunity from prosecution was a severe and pervasive problem. Divisions between political and security apparatuses in the west and east, a security vacuum in the south, and the presence of terrorist groups in some areas of the country severely inhibited the government'the presence of terrorist groups in some areas of the country severely inhibited the government’s ability to investigate or prosecute abuses. The government took limited steps to investigate abuses; however, constraints on the government'’s reach and resources, as well as political considerations, reduced its ability or willingness to prosecute and punish those who committed such abuses.

In June 2020, the U.N. Human Rights Council approved the creation of a Fact-Finding Mission to Libya (FFML) to investigate and preserve evidence of human rights abuses. In the wake of intense conflict in northwestern Libya, evidence has emerged of deliberate mining and booby-trapping of civilian homes south of Tripoli,82 extrajudicial killings in the city of Tarhuna,83 looting and forced displacement by anti-LNA forces,84 and the murder of migrants.85

79 Al Wasat (Libya), “Exclusive Q&A: U.S. Ambassador to Libya Discusses Efforts to End Fighting, Coronavirus Response,” April 5, 2020.

80 AFP, “Turkey criticizes EU’s Operation Irini to contain arms shipments to Libya,” June 19, 2020. 81 Lorne Cook, “Why is Turkey the key to unlocking a NATO-EU naval operation?” Associated Press, June 17, 2020; and AFP, “EU says NATO talks on Irini not prompted by Turkey incident,” June 13, 2020. 82 Human Rights Watch, Libya: Landmines Left After Armed Group Withdraws, June 3, 2020. 83 Declan Walsh, “U.N. Expresses Horror at Mass Graves in Libya,” New York Times, June 13, 2020. 84 Ulf Laessing, “’'Numerous' reports of looting in retaken Libyan towns, UN says,” Reuters, June 7, 2020. 85 Statement by Yacoub El Hillo, Humanitarian Coordinator for Libya, on the killing of migrants southwest of Tripoli, May 29, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

18

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

Flows Decline, but Migrants Face Risks and Abuse Flows Decline, but Migrants Face Risks and Abuse

Weak governance and conflict transformed Libya into a major staging area for the transit of non-Libyan migrants seeking to reach Europe from 2014 through 2018. Data collected by migration observers and immigration officials suggested that many migrants from sub-Saharan Africa have transited remote areas of southwestern and southeastern Libya to reach coastal urban areas for onward transit to Europe. Others, including Syrians, have entered Libya from neighboring Arab states seeking onward transit to refuge in Europe and beyond. According to the U.N. Panel of Experts, as of December 2019,

Human trafficking and migrant smuggling to and through Libya onward to Europe remains profitable, but the trade has all but collapsed compared with the pre-2018 period. Changing regulations in neighbouring countries and localized clashes along trafficking routes have forced changes to established routes in order to avoid these barriers. This makes migration to Libya longer, costlier and more dangerous. The volume of cross-border traffic into Libya through Chad and the Niger has dropped significantly over the past two years.

In March 2020, the

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported that more thanreports that nearly 654,000 migrants wereare in Libya, alongside more than 373401,000 internally displaced persons and more than 48,000 refugees and asylum seekers from other countries identified by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).63

86

In total, more than 11,000 migrants arrived by sea to Italy in 2019, with the vast majority having departed from western Libya. At least 1,262 died in transit in the central Mediterranean.6487 By comparison, in 2016, at least 181,436 migrants arrived by sea to Italy and at least 4,851 died on the central Mediterranean route, in what IOM estimates was the deadliest year for migrants ever recorded in the Mediterranean.6588 Observers attribute declines in migrant crossings and deaths to efforts by Italian and European Union authorities to work with government and nongovernment figures inside Libya to prevent migrant departures and patrol coastal waters (see textbox below).66

89

Some critics of the European approaches allege that the policies provide financial benefit and bestow political importance and security influence on unaccountable local militia groups, who may threaten the human rights and security of migrants subject to detention and economic hardship in Libya.90 A patchwork of Libyan local and national authorities and nongovernmental entities assume responsibility for responding to various elements of the migrant crisis, including the provision of humanitarian assistance and medical care, the patrol of coastal and maritime areas, and law enforcement efforts targeting migrant transport networks. Violence and insecurity in Libya complicate international attempts to assist Libyan partners in these efforts and to improve coordination among Libyan stakeholders. Airstrikes and shelling since April 2019 have killed and injured migrants in western Libya.91 Internal movement restrictions, limited local 86 IOM Libya, “Monthly Update—April 2020,” May 7, 2020, and UNHCR, “Libya Update,” June 19, 2020. 87 IOM Missing Migrants Project data, and ‘Arrivals to Italy’ as reported by IOM authorities as of December 2019. 88 IOM Missing Migrants Project data, and ‘Arrivals to Italy’ as reported by IOM and national authorities. 89 Declan Walsh and Jason Horowitz, “Italy, Going It Alone, Stalls the Flow of Migrants. But at What Cost?” New York Times, September 17, 2017; Giovanni Legorano and Jared Malsin, “Migration from Libya to Italy, Once Europe’s Gateway, Dwindles After Clampdown,” Wall Street Journal, March 10, 2019.

90 Sudarsan Raghavan, “Returned to a War Zone: One Boat. Dozens of Dreams. All Blocked by Europe’s Anti-Migrant Policies,” Washington Post, December 28, 2019.

91 In July 2019, an airstrike attributed by U.N. investigators to “aircraft belonging to a foreign State” destroyed a facility being used by an anti-LNA militia to house detained migrants and store weapons. The strike killed 53 migrants, including 6 children, and wounded 87 others. Press reports attributed the strike to a UAE aircraft. Libya: U.N. News, “U.N. report Urges Accountability for Deadly Attack Against Migrant Centre,” January 27, 2020; and Declan Walsh,

Congressional Research Service

19

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy

resources, and public fear of infection may make migrants present in Libya even more vulnerable in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Select European and International Responses

European countries have worked for years to limit the trafficking of individuals from Libya to southern Europe and have acted at times to save the lives of migrants at sea. In May 2015, the European Union created a naval force (Operation EUNAVFOR MED SOPHIA) In parallel to naval operations and training, the EU Trust Fund for Africa supports programs designed to protect migrants along the central Mediterranean route and to provide related management assistance in Libya. The EU funding supports Libyan municipalities that host migrants in Libya, and has engaged in border security support programming with few tangible results. A joint EU, African Union (AU), and U.N. Task Force works to improve migrant protection along migration routes to, from, and in Libya. With support from this Task Force, IOM has facilitated the return of more than 50,000 migrants to their home countries from Libya through a voluntary humanitarian returns program since December 2017. 95 COVID-19 concerns are shaping Libyan and international approaches to migration challenges. Libya |

Some critics of the European approaches allege that the policies provide financial benefit and bestow political importance and security influence on unaccountable local militia groups, who may threaten the human rights and security of migrants subject to detention and economic hardship in Libya.71 A patchwork of Libyan local and national authorities and nongovernmental entities assume responsibility for responding to various elements of the migrant crisis, including the provision of humanitarian assistance and medical care, the patrol of coastal and maritime areas, and law enforcement efforts targeting migrant transport networks. Violence and insecurity in Libya complicate international attempts to assist Libyan partners in these efforts and to improve coordination among Libyan stakeholders. Airstrikes and shelling since April 2019 have killed and injured migrants in western Libya.72 Internal movement restrictions, limited local resources, and public fear of infection may make migrants present in Libya even more vulnerable in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.