Low Oil Prices: Prospects for Global Oil Market Balance

Changes from April 13, 2020 to April 17, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Reduced travel, slowing economic activity, and petroleum-product demand suppression related to the COVID-19 outbreak, combined with announced plans to increase crude oil supplies, have created expectations of an imbalanced and significantly oversupplied near-term petroleum market. Oversupply expectations have contributed to oil prices declining nearly 60% since January. Some regional oil prices have been less than $10 per barrel. While low oil prices are generally positive for consumers, current price levels are causing financial stress for the U.S. oil sector and several policy options could be explored that might provide some degree of relief.

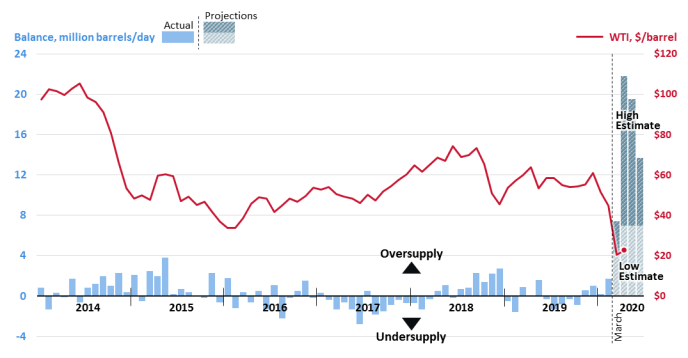

Market balance—supply minus demand—is one important factor that influences oil prices, refinery crude oil acquisition cost, and the price of consumer petroleum products (e.g., gasoline). Oil market characteristics—generally inelastic supply and demand in the short term—can contribute to market conditions that could result in volatile price movements (both up and down) when supply and demand are imbalanced by 1 to 2 million barrels per day (Mbpd) for a brief or extended period. Preliminary projections—subject to revision—indicate that global imbalance could be as high as 21.815 Mbpd in Aprilthe second quarter (2Q) of 2020 (see Figure 1), including the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) crude oil production agreement (see details below) that takes effect in May. Prolonged oversupply periods at this level could test petroleum storage and logistical limits and could further depress oil prices. However, current projections—that include uncertain assumptions about demand recovery—indicate that balance could move to an undersupplied state as early as 3Q2020. 2020 (see Figure 1). Prolonged oversupply periods at this level could test petroleum storage and logistical limits and could further depress oil prices.

Market Balancing Options

Balancing petroleum markets during normal periods of economic activity is challenging due to demand uncertainties, unplanned supply outages, and geopolitical events. Generally, Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)OPEC production decisions aim to manage oil supply in order to achieve its stated mission to stabilize markets. Since 2017, OPEC and a group of non-OPEC countries (collectively OPEC+), including Russia, have engaged in agreements to reduceadjust production. Current oversupply expectations are primarily the result of demand suppression related to COVID-19.

Market balance in the short-term would largely depend on economic activity returning to pre-outbreak levels, the timeframe for which is uncertain as actual demand impacts are unknown. Addressing the supply side of estimated market imbalances could take the form of price-responsive adjustments, an OPEC+ production agreement, or some sort of government intervention.

Price-Responsive Supply Adjustments

Current market and price conditions create challenges for all oil companies and oil-producing countries, including the U.S. oil sector. In the short-term, oil supply could be reduced by decreasing production from existing assets should price levels decline below marginal production costs. Efforts to manage financial impacts are reportedly happening at the company (e.g., capital expenditure reductions and employment adjustments) and country (e.g., budget/ and spending reductions) level. Additionally, reportsReports indicate that U.S. drilling activity is declining, and EIA projects U.S. crude oil production in 2020 will be 500,000 bpd lower than 2019. While price-responsive adjustments could motivate efficiency within the oil sector, such an approach—due to the uncertain timeframe for demand and price recovery—could also have long-term adverse effects on some companies and the locations in which they operate.

OPEC+ Production Agreement

OPEC+ could resume its collective supply management activities in an effort to stabilize oil markets. In March 2020, the group failedAfter failing to agree on an OPEC recommendation to further reduce oil production through 2020. On April 10, 2020, OPEC+ , OPEC+ subsequently announced an oil production agreement with the intent of stabilizing the oil market. Using October 2018 production levels as a baseline for most countries (Saudi Arabia and Russia are baselined at 11 Mbpd), the agreement would collectively reduce crude oil production by different amounts over various periods:

- May 1-June 30, 2020: 9.7 Mbpd

- July 1-December 31, 2020: 7.7 Mbpd

- January 1, 2021-April 30, 2022: 5.8 Mbpd

The agreement also calls on non-OPEC+ oil producers to contribute to market stabilization.

Government Supply Intervention: Historical Perspective

Among countries outside of the OPEC+ group, some governments (state, provincial, and federal) have intervened to manage production levels. These efforts have generally aimed to address domestic or regional market imbalances. For example, the government of Alberta, Canada, has an active oil production limit program. Instituted in December 2018, the curtailment policy aims to match production volumes with transportation—pipeline and rail—capacity in order to support regional prices that influence producer revenues and provincial royalties.

Historically, the U.S. federal government and some oil-producing states have engaged in efforts to curtail oil supply, including deployment of state militia and the National Guard, state-level prorationing, interstate oil transport prohibitions, and federal production targets. In the 1930s—a domestic oversupply period with regional prices as low as 10¢ per barrel—Congress enacted laws aimed at managing domestic oil output. Some examples include:

- National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA, P.L. 73-67): enacted in 1933 and held unconstitutional in 1935, NIRA authorized the President to prohibit interstate transportation of petroleum in excess of volumes allowed by state laws and regulations ("contraband oil"). NIRA authorities were invoked to impose federal oil production quotas for each oil-producing state.

- Hot Oil Act (P.L. 74-14, 15 U.S. Code §715): reinstated federal regulation of interstate transportation of "contraband oil."

- Public Resolution 74-64: provided congressional consent for an interstate compact to conserve oil and gas. The Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission (IOGCC)—originally conceived to address overproduction and depressed prices—engages in resource conservation and its charter indicates that limiting production to stabilize prices is not an intended purpose.

Regulatory agencies in Oklahoma, Texas, Louisiana, and other states have prorationed oil supply within their respective jurisdictions. Those efforts, which inherently provided some level of price support, essentially ended in the early 1970s as domestic demand exceeded domestic production. Reinstituting these authorities to address current oil market conditions—a concept recently revisited—could raise policy, legal, and administrative questions.

Historically, the U.S. federal government and some oil-producing states have engaged in efforts to curtail oil supply. Regulatory agencies in Oklahoma, Texas, Louisiana, and other states have prorationed—similar to quotas—oil supply within their respective jurisdictions. Those efforts, which are generally based on conservation and waste prevention authorities, essentially ended in the early 1970s as domestic demand exceeded domestic production. However, efforts are underway to consider reinstituting these state-level authorities. The Railroad Commission (RRC) of Texas held an open meeting—in response to a filed complaint—to discuss many different stakeholder views about prorationing oil production in the state. A similar appeal has been submitted to the Oklahoma Corporation Commission (OCC) and a hearing is reportedly scheduled for May 11, 2020.

Oil curtailment efforts at the federal level have generally been limited to prohibiting interstate transportation of oil volumes that exceed state production limits ("contraband oil"), an existing Presidential authority (15 U.S.C. §715).