Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Data Challenges and Issues for Congress

Changes from April 2, 2020 to July 14, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Tracking China'’s Global Economic Activities:

July 14, 2020

Data Challenges and Issuess Global Economic Activities: Data Challenges and Issues for Congress

Contents

- Background

- Framing the Debate on China's Global Reach

- Data Limitations

- Issues and Options for Congress

Figures

Tables

Summary

The People' for Congress

Andres B. Schwarzenberg

The People’s Republic of China (PRC or China) has significantly increased its overseas

Analyst in International

investments since launching its "“Go Global Strategy"” in 1999 in an effort to support the overseas

Trade and Finance

expansion of Chinese firms and make them more globally competitive. Since then, these firms—

many of which are closely tied to the Chinese government—have acquired foreign assets and capabilities and pledged billions of dollars to developfinance infrastructure abroad. As a result, many in

Congress and the Trump Administration are focusing on the critical implications of China's ’s growing global economic reach for U.S. economic and geopolitical strategic interests.

Some analysts see these Chinese activities as primarily commercial in nature. Others contend that the surge in global economic activity is also part of a concerted effort by China'’s leaders to bolster China'’s position as a global power and ensure support for their foreign policy objectives. There is also growing concern about the terms of China'’s economic engagement, particularly over the ways that Chinese lending may be creating unsustainable debt burdens for some countries and over how much of China'’s lending is tied to commercial projects and Chinese state firms that benefit from the investment.

A major challenge to understanding the implications of China'’s growing global economic reach is the critical gap in the availability and accuracy of data and information. Most notable is the fact that no comprehensive, standardized, or authoritative data—from either the Chinese government or international organizations—are available on Chinese overseas economic activities. Given the complexity and multifaceted nature of the projects in which Chinese entities are involved, attempts to assess the size and scope of these projects are rough estimates, at best, and should be regarded as such. Figures cited in news articles, think-tank reports, and academic studies may not be entirely accurate and should be interpreted with caution. For instance, many publicly and privately available unofficial "trackers"“trackers”—from which these data are often sourced—are based on initial public announcements of Chinese overseas projects, which may differ significantly from actual capital flows because such projects may evolve or may never come to fruition.

In the absence of accurate and sufficient data, Members of Congress may seek ways to improve their own understanding by supporting U.S. and international efforts to better track, analyze, and publicize actual Chinese investment, construction, assistance, and lending activities. Congress, for example, may direct agencies within the executive branch to develop a whole-of-government approach to better assess the global economic activities of U.S., Chinese, and other major actors. Additionally, Congress could require these agencies to study the adequacy of data and information recording, collection, disclosure, reporting, and analysis at the U.S. and international levels. Better information could facilitate clearer, deeper, and better informed assessment of such activities and their (1) impact on U.S. interests and (2) ramifications for the norms and rules of the global economic system—a system whose chief architect and dominant player to date largely has been the United States.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4 link to page 5 link to page 7 link to page 13 link to page 4 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 19 link to page 16 link to page 19 link to page 19 Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Challenges and Issues for Congress

Contents

Background ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Framing the Debate on China’s Global Reach ................................................................................ 2 Data Limitations .............................................................................................................................. 4 Issues and Options for Congress ................................................................................................... 10

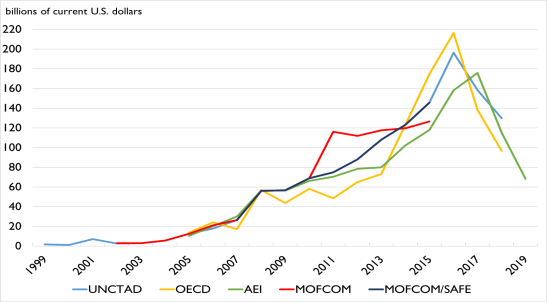

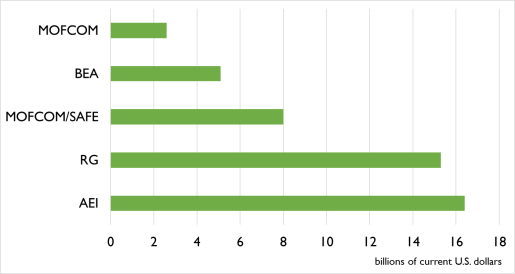

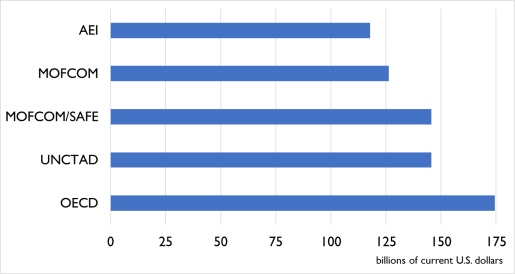

Figures Figure 1. China’s Total Outward Direct Investment Flows ............................................................. 1 Figure 2. China’s FDI Outflows to the United States in 2015 ........................................................ 6 Figure 3. China’s FDI Outflows to the World in 2015 .................................................................... 6

Tables Table 1. China’s FDI Outflows to the World ................................................................................... 7

Table A-1. Select Databases on China’s Global Investment, Construction, and Lending

Activities .................................................................................................................................... 13

Table B-1. China’s FDI Stock the United States ........................................................................... 16

Appendixes Appendix A. Databases and Resources ......................................................................................... 13 Appendix B. China’s FDI in the United States ............................................................................. 16

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 16

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4

Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Challenges and Issues for Congress

Background The People’States.

Background

The People's Republic of China (PRC or China) has significantly increased its overseas investments since launching its "“Go Global Strategy"” in 1999 in an effort to make Chinese firms more globally competitive and advance domestic economic development (Figure 1). Since then, Chinese firms have acquired foreign assets and pledged billions of dollars to develop finance infrastructure abroad. China'’s push overseas has been particularly visible in the Indo-Pacific region, a major focus of China'’s effort to increase global trade connectivity through the "“Belt and Road Initiative"” (BRI, initially known as "“One Belt, One Road"”), which launched in 2013.1 1 However, China'’s overseas, global economic activities include the purchase, financing, development, and operation of assets and infrastructure across Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, North America, and Oceania.

Links to Select Databases on China'

1 Mercator Institute for China Studies, “Mapping the Belt and Road Initiative: This is Where We Stand,” July 6, 2018.

Congressional Research Service

1

Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Challenges and Issues for Congress

Links to Select Databases on China’s Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

AEI

s Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

|

AEI |

American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation |

|

BEA |

BEA

U.S. Department of Commerce |

|

MOFCOM |

MOFCOM Ministry of Commerce People |

|

NBS |

NBS

National Bureau of Statistics of China |

|

OECD |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

|

RG |

RG

Rhodium Group |

|

SAFE |

SAFE

State Administration of Foreign Exchange of the People |

|

UNCTAD |

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development |

Many in Congress and the Trump Administration are focusing attention on possible critical implications of China'’s growing global economic reach for U.S. economic and geopolitical strategic interests. Some analysts view China'’s activities as largely commercial in nature, following the path that some Western multinational firms forged in the 1980s and 1990s in expanding and integrating into global markets.22 Others contend that China'’s activities are ultimately in support of alleged efforts by Beijing to challenge and undermine U.S. global influence.3

3

This report does not provide figures or estimates of China'’s global economic activities. Nor is it an in-depth analysis of recent trends and developments. Rather, it provides an overview of select issues and challenges encountered when compiling, interpreting, and analyzing statistics on Chinese investment, construction, financing, and development assistance around the world.

Framing the Debate on China'’s Global Reach

Economic- and resource-related imperatives play an important role in China'’s expanding global economic footprint. Analysts see strong domestic economic development as a primary objective for China'’s leaders for a number of reasons, including those leaders'’ desire to raise the living standards of the population, dampen social disaffection about economic and other inequities, and sustain regime legitimacy. In addition, China'’s rapid economic growth has created a domestic appetite for greater resources and technology, as well as for creating markets for Chinese goods—all of which have served as powerful drivers of China'’s integration into the global economy and 2 See, for example, The Economist Intelligence Unit, “China’s Expanding Investment in Global Ports,” October 11, 2017. In certain aspects, some of China’s economic activities may resemble development assistance.

3 There are three broad areas of concern: (1) rapid increase/expansion, (2) types of activities (e.g., sensitive areas like infrastructure and technology), and (3) the terms of engagement (e.g., state firms, the promotion of Chinese industrial policies, indebtedness of host governments). For more detail, see, for example, Thomas P. Cavanna, “Unlocking the Gates of Eurasia: China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Its Implications for U.S. Grand Strategy,” Texas National Security Review, Vol. 2, No. 3, May 2019; Melanie Hart and Kelly Magsamen, “Limit, Leverage, and Compete: A New Strategy on China,” Center for American Progress, April 3, 2019; and Catherine Trautwein, “All Roads Lead to China: The Belt and Road Initiative, Explained,” PBS Frontline, June 26, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

2

Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Challenges and Issues for Congress

s integration into the global economy and enthusiasm for international trade and investment agreements.44 For example, as China'’s energy demands have continued to rise, the Chinese government has sought bilateral agreements, oil and gas contracts, scientific and technological cooperation, and de-facto multilateral security arrangements with energy-rich countries, both in its periphery and around the world. Moreover, China'China’s recent relative economic slowdown (in the aftermath of the government-financed boom of the post-global recession years) has created excess capacity and the need to find overseas markets and employment opportunities for its infrastructure and construction sectors.55 In pursuing commercial opportunities abroad, Chinese firms—many of them state owned—have become global leaders in these sectors (e.g., transport infrastructure, such as ports and high-speed rail).

Some observers contend that these investment and construction trends may reflect an attempt by China to bolster its position as a global power, gain control of vital sea-lanes and energy-supply routes, secure key supply chains, aggregate control over communications infrastructure and standards, and build up geo-economic leverage to ensure support for its foreign policy objectives.66 In particular, some U.S. officials have expressed concerns that China'’s growing international economic engagement goes hand-in-hand with expanding political influence.77 The seemingly—though debatable—"“no strings attached"” nature and looser terms of Beijing's ’s overseas loans and investments may be attractive to foreign governments wanting swifter, more "“efficient,"” and relatively less intrusive solutions to their development problems than those offered by bilateral and international financial institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and Asian Development Bank (ADB).88 Unlike these institutions, many of the Chinese financial institutions and enterprises involved in China'’s overseas investment, lending and construction are owned or subsidized by the government. As such, they are not accountable to shareholders, do not generally impose safeguards or international standards related to transparency, human rights, and environmental protection, and can afford short-term losses in pursuit of longer-term, strategic goals.9

9

4 See, for example, Sam Ellis, “China’s Trillion-Dollar Plan to Dominate Global Trade,” Vox, April 6, 2018. Other motivations for China’s foreign investments include securing strategic resources, learning how to operate in a global marketplace, and currying favor with senior officials by advancing PRC initiatives, such as BRI. In terms of construction contracts, an important motivation is to provide employment for Chinese construction workers who now have insufficient projects on which to work within China’s borders. 5 In some cases, China’s activities have heightened cultural backlash and resentment by the style that Chinese overseas investments and construction projects have been pursued, particularly in regard to the use of Chinese—rather than local—companies and workers.

6 William Pacatte, “Be Afraid? Be Very Afraid?—Why the United States Needs a Counterstrategy to China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” International Security Program, Center for Strategic & International Studies, October 2018. 7 See, for example: James Swan, “Africa-China Relations: The View from Washington,” U.S. Department of State Archive, February 9, 2007; White House, Claudia E. Anyaso, “Implications of Chinese Economic Expansion in Africa,” U.S. Department of State Archive, October 31, 2008; “Remarks by Vice President Pence at the 2018 APEC CEO Summit, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea,” November 16, 2018; Eva Vergara, “Pompeo: China financing of Maduro prolongs Venezuela crisis,” AP News, April 12, 2019. 8 The Trump Administration and some Members of Congress have questioned the motives behind China’s actions in the case of several individual projects with strategic implications, notably the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka and a port in Djibouti. After Sri Lanka found itself unable to repay Chinese loans, a PRC company, China Merchants Port Holdings Company, Ltd., acquired a majority stake in the company that operates the Hambantota port, and signed a concession agreement to operate the port for 99 years from 2017.

9 Chinese projects typically involve a consortium of Chinese state firms who provide the full range of goods, labor and services for the projects that China finances. These projects are neither assistance—Chinese loans are typically not offered interest-free and tend to be issued at, or near, market terms—nor truly commercial, because repayments are often backed by collateral (e.g., energy, minerals, or commodities) commitments made to the Chinese government, including state firms designated by the Chinese government that might not even be party to the original transaction.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 16 Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Challenges and Issues for Congress

Although some analysts and policymakers suggest that Chinese officials and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) appear more comfortable working with undemocratic or authoritarian governments, China'’s outreach also has extended to the United States, key U.S. allies and partners, and regions where U.S. economic linkages and diplomatic sway have been, until recently, predominant. These developments have led some observers to conclude that Beijing intends to challenge—or is already challenging—U.S. global leadership directly.1010 As a result, some Members of Congress and Administration officials are focusing attention on the critical implications that China'’s increasing international economic engagements could have for U.S. economic and strategic interests.

Some observers have sought to compare China'’s activities to those of the United States. In contrast to China'’s, however, U.S. global economic engagements have tended to be more diverse and not government-directed or -funded.1111 They have been driven primarily by the U.S. private sector, whose global presence is long-standing and comprehensive.

Data Limitations

A major challenge when researching global investment and construction projects and related loans is the accuracy of the data.1212 While this challenge is not unique to projects involving Chinese players, it is exacerbated by the nature of many Chinese projects and loans, whose terms are not always publicly available or transparent. No comprehensive, standardized, or authoritative data are available on all Chinese overseas economic activities—from either the Chinese government or international organizations. A number of think tanks and private research firms have developed datasets to track investment, loans, and grants by Chinese-owned firms and institutions using commercial databases, news reports, and official government sources, when available (Appendix A). These datasets often record the value of projects, loans, and grants when they are publicly announced (e.g., at press conferences). However, many publicly announced projects are never formalized, and if they are, project and loan details may change, and projects may not always come to fruition for various reasons (e.g., changing economic and political conditions, or concerns about sovereignty, debt structure, or environmental impact).

Ministry of Commerce of the People

Many datasets leave out projects and loans below a certain threshold (e.g., under $25 It is difficult—if not impossible—to track Chinese investment that goes through offshore financial centers (e.g., Hong Kong, British Virgin Islands, and Cayman Islands)—which in some years has accounted for as much as three-quarters of China

Datasets by think tanks and private research firms often record the value of projects, loans, and grants when they are announced, and may not update that information to reflect if and when the projects come to fruition.

|

Despite these limitations, figures derived from such "“data trackers"” often drive the policy debate. Because U.S. policymakers may rely on them to assess the overall scope and magnitude of Chinese activities, it is important to recognize the problems with the data and the limitations of existing databases. While they might be valuable and informative, they may also provide vastly different figures that are not necessarily comparable. For example, for 2015—the most recent year for which complete annual data are available from all major sources—figures on China's ’s investment flows into the United States vary from $2.6 billion (which only includes nonfinancial gross foreign direct investment (FDI) flows and is reported by MOFCOM13))13 to $16.4 billion (which includes gross announced transaction flows of $100 million or more and is tracked by AEI/Heritage14) )14 (Figure 2). Similarly, China'’s total outward investment flows for the same year range from $117.9 billion (AEI/Heritage) to $174.4 billion (OECD15) )15 (Figure 3 andand Table 1). . Comparability issues also arise when trying to differentiate loan, investment, and construction projects that overlap, since datasets only capture a certain type of activity. Various datasets' ’ categorizations may not cover the full range of activity that is taking place.

Table 1. China'

Congressional Research Service

6

Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Challenges and Issues for Congress

Table 1. China’s FDI Outflows to the World

s FDI Outflows to the World

(in billions of current U.S. dollars)

|

Year |

MOFCOM |

MOFCOM/SAFE |

UNCTAD |

OECD |

AEI/HERITAGE |

|

2000 |

0.9 |

||||

|

2001 |

6.9 |

||||

|

2002 |

2.7 |

2.5 |

|||

|

2003 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

|||

|

2004 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

|||

|

2005 |

12.3 |

12.3 |

13.7 |

10.2 |

|

|

2006 |

21.2 |

17.6 |

23.9 |

20.3 |

|

|

2007 |

26.5 |

26.5 |

26.5 |

17.2 |

30.1 |

|

2008 |

55.9 |

55.9 |

55.9 |

56.7 |

56.3 |

|

2009 |

56.5 |

56.5 |

56.5 |

43.9 |

56.1 |

|

2010 |

68.8 |

68.8 |

68.8 |

58.0 |

66.0 |

|

2011 |

116.0 |

74.7 |

74.7 |

48.4 |

70.3 |

|

2012 |

111.7 |

87.8 |

87.8 |

65.0 |

78.5 |

|

2013 |

117.6 |

107.8 |

107.8 |

73.0 |

79.8 |

|

2014 |

119.6 |

123.1 |

123.1 |

123.1 |

102.3 |

|

2015 |

126.3 |

145.7 |

145.7 |

174.4 |

117.9 |

|

2016 |

196.1 |

216.4 |

158.2 |

||

|

2017 |

158.3 |

138.3 |

175.6 |

||

|

2018 |

129.8 |

96.5 |

115.2 |

||

|

2019 |

68.2 |

Source: Congressional Research Service with data from the AEI/Heritage Foundation's China Global Investment Tracker; MOFCOM's Foreign Direct Investment Statistics; MOFCOM/SAFE's 2015 Statistical Bulletin of China'(in billions of current U.S. dollars)

Year

MOFCOM

MOFCOM/SAFE

UNCTAD

OECD

AEI/HERITAGE

2000

0.9

2001

6.9

2002

2.7

2.5

2003

2.9

2.9

2004

5.5

5.5

2005

12.3

12.3

13.7

10.2

2006

21.2

17.6

23.9

20.3

2007

26.5

26.5

26.5

17.2

30.1

2008

55.9

55.9

55.9

56.7

56.3

2009

56.5

56.5

56.5

43.9

56.1

2010

68.8

68.8

68.8

58.0

66.0

2011

116.0

74.7

74.7

48.4

70.3

2012

111.7

87.8

87.8

65.0

78.5

2013

117.6

107.8

107.8

73.0

79.8

2014

119.6

123.1

123.1

123.1

102.3

2015

126.3

145.7

145.7

174.4

117.9

2016

196.1

216.4

158.2

2017

158.3

138.3

175.6

2018

129.8

96.5

115.2

2019

68.2

Source: Congressional Research Service with data from the AEI/Heritage Foundation’s China Global Investment Tracker;

MOFCOM’s Foreign Direct Investment Statistics; MOFCOM/SAFE’s 2015 Statistical Bul etin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment; OECD'’s International Direct Investment Statistics; and UNCTAD'’s UNCTADstat.

Notes: Not adjusted for inflation. AEI only includes reported transactions of $100 millionmil ion or more; MOFCOM only includes

nonfinancial FDI; OECD, UNCTAD, and MOFCOM/SAFE compile data based on the IMF'’s BPM6 and OECD'’s BD4 guidelines.

China'

China’s official foreign direct investment (FDI) statistics are compiled by two government agencies according to different criteria. The Ministry of Commerce of the People'’s Republic of China (MOFCOM)'’s data are based on officially approved investments by nonfinancial institutions—that is, information recorded during the approval process rather than through surveys or questionnaires as in the United States (see textbox below). They are generally separated out by country and industry. The State Administration of Foreign Exchange of the People'People’s Republic of China (SAFE), on the other hand, reports Balance of Payments (BoP) data at the aggregate level. SAFE, in theory, follows IMF guidelines. While both agencies are supposed to reconcile their figures in their annual revisions, discrepancies in the total amounts reported are common and significant.

Congressional Research Service 7 Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Challenges and Issues for Congress U.S. Inward and Outward Direct Investment Statistics

U.S. Department of Commerce

BEA publishes two broad sets of statistics on outward direct investment and on inward direct investment: (1) statistics on international transactions and direct investment positions and (2) statistics on the activities of multinational enterprises. Both sets are derived from information BEA conducts seven mandatory surveys to Reporting on BEA

Source: Excerpts from A Guide to BEA |

Much of China'’s official outbound FDI also has traditionally been registered in Hong Kong, the former British colony that has been a Special Administrative Region of the PRC since 1997, or in tax havens such as the Cayman Islands or British Virgin Islands. Chinese firms, in particular, are known to use holding companies and offshore vehicles to structure their investments. "“Round-tripping"tripping” (the practice of firms routing themselves funds through localities that offer beneficial tax policies or special incentives), "“trans-shipping"” (the practice of firms routing funds through countries that offer favorable tax policies to later reinvest these funds in third countries), and indirect holdings all make it difficult to track and disaggregate investments accurately. Chinese domestic investors have also been known to rely on these schemes to take advantage of favorable conditions granted only to foreign investors. As the Economist Intelligence Unit notes, "“Chinese statistics record approved projects rather than actual money transfers,"” and "“[c]ompanies often list the initial port of call of their capital, rather than its final destination, thus falsely inflating the importance of stop-over locations."16

”16 In addition to data reliability and comparability issues, it is not always possible to determine if an asset or project is wholly or partially owned, financed, built, or operated by a Chinese entity. Thus, the lack of consistent, disaggregated, and detailed information limits the proper assessment of the size, scope, and implications of these activities. Moreover, because major projects generally involve several phases and a sometimes-evolving cast of stakeholders, it is not always possible to distinguish between the phases of acquisition or construction and those of operations—as they are often blended in terms of time and firms involved.

Many of the overseas infrastructure projects in which Chinese entities are involved—particularly ports—also present distinct challenges not always encountered in the analysis of traditional foreign direct investments (e.g., multinational corporations building a new factory or acquiring an existing domestic firm). In the case of infrastructure, to attract foreign investment and transfer risks to the private sector, it is common for host countries to offer long-term concessions or

16 The Economist Intelligence Unit, “Chinese Investment in Developed Markets: An Opportunity for Both Sides?” 2015.

Congressional Research Service

8

Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Challenges and Issues for Congress

leases—for both construction and operation. These typically allow the grantee firm the right to use land and facilities (e.g., ports and highways) for a defined period in exchange for providing services. Because these lands and facilities tend to be owned by the host government, the investments can come in the form of use-rights through leases or joint ventures. These challenges, together with the opacity of China'’s terms and conditions, can limit the ability to assess accurately the extent of Chinese involvement.

Data availability limitations also may arise since China often finances infrastructure development through its export credit agencies and development banks.1717 China is not a member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) or part of its Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits, which includes rules on transparency procedures for government-backed export credit financing.1818 The United States, China, and other countries have been working to develop a new set of international rules, but progress reportedly has been limited.19

19

Finally, some of China'’s global economic activities are portrayed inaccurately as "“foreign aid"” or "“development assistance."” While certain aspects may resemble assistance in the conventional sense, they generally do not meet the OECD standards of "“official development assistance" ” (ODA).2020 The terms of China's "’s “ODA-like"” loans are less concessional than those of other major actors such as the United States and Japan, have large commercial elements with economic benefits accruing to Chinese actors, and are rarely government-to-government.2121 Details on specific Chinese deals and overall flows are opaque because the PRC government rarely releases data on any of its lending activities abroad or those of its state firms and entities. China also is not part of the OECD'’s Development Assistance Committee, which "“monitors development finance

17 Some of China’s development and infrastructure assistance programs have been termed “tied aid” or “mixed credits.” Tied aid credits and mixed credits are two of the primary methods whereby governments provide their exporters with official assistance to promote exports. Tied aid credits include loans and grants which reduce the financing costs for exporters below market rates and which are tied to the procurement of goods and services from the donor country. Mixed credits combine concessional government financing (funds at below-market rates or terms) with commercial or near-commercial funds to produce lower than market-based interest rates and more lenient loan terms. These types of credits typically are tied to the procurement of goods and services from the donor country, and through them, foreign governments use their overseas assistance programs to influence procurement decisions in favor of their own exporters. The OECD’s Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits—of which China is not a part—provides disciplines on tied aid.

18 These are financial terms and conditions, such as down payments, maximum repayment terms, minimum interest rates, and country risk classifications; provisions on tied aid; notification procedures; and sector-specific terms and conditions, covering the export credits for ships, nuclear power plants, civil aircraft, renewable energies, and water projects. Military equipment, agricultural goods, and untied development aid are not covered by the Arrangement.

19 In 2012, the United States and China established an International Working Group on Export Credits (IWG) to develop a new set of international guidelines for official export credit support. The White House, “White House Fact Sheet on U.S.-China Economic Relations,” Press Release, November 12, 2014. More broadly, there are no international rules governing development finance comparable to those in the OECD that govern export credit financing among its members and other countries willing to join the OECD arrangement.

20 According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), official development assistance (ODA) consists of disbursements of loans made on concessional terms and of grants by official agencies (including state and local governments) to promote economic development and welfare in recipient countries and territories. ODA includes loans with a grant element of at least 25%. It does not include military aid and transactions that have primarily commercial objectives (e.g., export credits).

21 China offers little aid, and when it does, it is often tied—that is, aid combined with other investments and projects supported by Chinese firms, goods and services. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), concessional loans are “loans that are extended on terms substantially more generous than market loans. The concessionality is achieved either through interest rates below those available on the market or by grace periods, or a combination of these.”

Congressional Research Service

9

Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Challenges and Issues for Congress

monitors development finance flows, reviews and provides guidance on development co-operation policies, promotes sharing of good practices,"” and helps set ODA standards.22

22 Issues and Options for Congress

Data limitations and lack of transparency, combined with the number of unknown variables that drive China'’s foreign economic policy decision-making processes, can affect how Members of Congress perceive and address the challenges that China'’s overseas economic activities pose to U.S. and global interests.2323 These limitations also complicate efforts to compare accurately the extent to which China'’s global economic reach differs from that of the United States.2424 Little consensus exists within the United States and the international community on China'’s ultimate foreign economic policy goals or what motivates and informs its economic activities abroad—either in general or with regard to specific regions or countries. Debate is ongoing over whether China'China’s global economic engagements have a pragmatic, overarching strategy, or are a series of marginally-related tactical moves to achieve specific economic and political goals. Similarly, some analysts argue that Beijing, through its global economic activities, is trying to supplant the United States as a global power, while others maintain that it is focused mainly on fostering its own national economic development.

In the absence of sufficient transparency in China'’s international economic activities, Members of Congress may seek to support current25current25 and new U.S. efforts to better track, analyze, and publicize actual Chinese investment, construction, assistance, and lending activities. Better data and information on China'’s activities may help U.S. policymakers assess the scope and address key questions over China'’s international engagements and growing economic role, including:

- How could the United States more accurately assess and respond to increasing competition by China for leverage and influence, both in countries where the United States is seeking to expand its economic and political ties, as well as in those with strong existing U.S. relationships?

-

To what extent are the terms of China

'’s global investments and economic assistance less restrictive than U.S. activities and how does this affect U.S. efforts to promote good governance around the world? -

What commercial advantages does China

'’s arguably unique approach to global economic engagement provide its companies, how does this affect the ability of U.S. companies to compete for international business, and what policies and agreements should the United States put in place to mitigate these effects? - How can the United States expose where China is in violation of the rules and norms of global institutions—particularly where it has or is seeking leadership positions—and use this knowledge to require China to adhere to international norms and condition its investments and assistance on widely accepted best practices?

-

22 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “Development Assistance Committee,” 2019. 23 See James Scott, Seeing Like a State (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), Chapter 1. 24 Some recent studies have concluded that the data may not be fully capturing the extent of activity, suggesting that at times U.S. observers may be either underestimating and/or overestimating China’s global economic reach. See, for example, Sebastian Horn, Carmen M. Reinhart, and Christoph Trebesch, “China Overseas Lending,” NBER Working Paper Series 26050 (July 2019).

25 See, for example, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)’s partnership with the College of William & Mary AidData Center for Development Policy.

Congressional Research Service

10

Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Challenges and Issues for Congress

What are the implications for the United States and international financial

What are the implications for the United States and international financialinstitutions (IFIs) that often promote good governance when China competes directly as an international lender and may offer less encumbered"assistance"“assistance” in ways that directly undermine U.S. and IFI values and principles? How should the IFIs and the United States respond to this challenge, particularly when China is seeking influence and leadership in both current IFIs and these alternative paths? Should China'’s leadership role be challenged if it is found to be undermining the goals and principles of the organizations it leads or seeks to lead, including with respect to transparency commitments? - How do differences in approach and scale of U.S. and Chinese global economic activities affect global perceptions of U.S. engagement around the world?

U.S. policymakers could seek to improve their own knowledge base in ways that may enable them to advance U.S. foreign economic interests more effectively, while at the same time encouraging more transparency by China. This could include:

- Collecting, maintaining, and publicizing—to the extent that is possible—a more accurate calculus of actual Chinese economic activities, particularly by tracking investment and assistance that is delivered, as opposed to that which is merely announced (e.g., either unilaterally or by encouraging or requiring greater disclosure through the international financial institutions and WTO).

-

Directing agencies within the executive branch to develop a whole-of-

government approach and guidance to better assess the global investment, construction, and lending activities of U.S., Chinese, and other major actors. As part of this effort, the U.S. government could harmonize U.S. programs for gathering information and streamline data centralization. In addition, it could study the adequacy of data and information recording, collection, disclosure, reporting, and analysis at the U.S. and international levels and recommend necessary improvements.

- Establishing a U.S. statistical office or program tasked with collecting current information on international capital flows and other information related to international investment, public procurement, and export and investment promotion, financing, and insurance by U.S., Chinese, and other major economic actors.

- Conducting oversight and examining more closely data collection and transparency commitments in various institutions, including the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) on investment, loans, and government procurement to determine if these mechanisms are sufficient and/or are being adhered to.

- Determining whether the World Trade Organization (WTO) should play a greater role to enhance transparency and set standards for dissemination of investment data through future reforms to key agreements or new agreements on investment.

- Examining the activities of international and regional organizations to determine if they are sufficient to address emerging data requirements or whether a major U.S. and/or internationally-coordinated effort is required.

- Supporting U.S. and international efforts to provide training courses, workshops, and technical assistance programs for countries to implement international Congressional Research Service 11 Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Challenges and Issues for Congress statistical guidelines and improve comparable data compilation and dissemination practices.

- Holding hearings on Chinese overseas lending and investment practices.

The United States could consider a combination of pressure and collaboration to strengthen its economic engagement efforts and encourage China to adopt international best practices. While the success of past efforts has arguably been limited, the United States could continue to:

- Work with other countries and international economic institutions to improve the collection and accuracy of data, address data deficiencies, and harmonize data reporting requirements by China and other major economies.

- Encourage China to participate more vigorously in adopting or developing rules on export credit financing and related areas, while urging China to sign on to public-private sector good governance initiatives and agreements.

-

Coordinate efforts with other countries to set terms for data transparency and best

practices for China to participate in multilateral and country-level donor foreign assistance dialogues and related efforts to prioritize key development goals and coordinate aid efforts in order to create synergies, avoid duplication and tied aid, and maximize each donor

'’s strengths. - Offer to work collaboratively with China—either bilaterally or through multilateral fora—to more clearly differentiate its official grant-based aid from its subsidization of trade and commerce credit; monitor the effectiveness of its aid strategies; harmonize aid reporting with other donor governments; and develop best practices in support of transparency and accountability.

Appendix A.

Congressional Research Service

12

Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Challenges and Issues for Congress

Appendix A. Databases and Resources

Databases and Resources

Table A-1. Select Databases on China'’s Global Investment, Construction, and

Lending Activities

Listed Alphabetically by Database Name

Geographic

Time

Database

Institution

Coverage

Scope

Coverage

Aid Data's Global Chinese

Wil iam & Mary's Global

Global

Loans and

2000-2014

Official Finance Dataset

Research Institute

Grants

CFR Belt and Road Tracker

Council on Foreign

Belt and Road

Imports,

2000-2017

Relations (CFR)

(67 countries)

Loans, and Investment

China-Canada Investment

University of Alberta’s

Canada

Investment

2014-2018

Tracker

China Institute (Edmonton, Canada)

China Global Investment

American Enterprise

Global

Investment and 2005-present

Tracker

Institute (AEI) and the

Construction

Heritage Foundation

Contracts

(Scissors 2020)

($100 mil ion and over)

China-Africa Research

Johns Hopkins

Africa

Loans, Trade,

2003-2018

Initiative

University’s School of

Investment,

(investment),

Advanced International

and Contracts

2000-2017

Studies

(loans), 1992-2018 (trade), 1987-2016 (agricultural investment), 1998-2018 (contracts)

China-Latin America Finance

Inter-American Dialogue

Latin America

Loans and

2005-2018

Database

and the Global

and the

Grants

Development Policy

Caribbean

s Global Investment, Construction, and Lending Activities

Listed Alphabetically by Database Name

|

Database |

Institution |

Geographic Coverage |

Scope |

Time Coverage |

|

Aid Data's Global Chinese Official Finance Dataset |

William & Mary's Global Research Institute |

Global |

Loans and Grants |

2000-2014 |

|

CFR Belt and Road Tracker |

Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) |

Belt and Road (67 countries) |

Imports, Loans, and Investment |

2000-2017 |

|

China-Canada Investment Tracker |

University of Alberta's China Institute (Edmonton, Canada) |

Canada |

Investment |

2014-2018 |

|

China Global Investment Tracker |

American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and the Heritage Foundation (Scissors 2020) |

Global |

Investment and Construction Contracts ($100 million and over) |

2005-present |

|

China-Africa Research Initiative |

Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies |

Africa |

Loans, Trade, Investment, and Contracts |

2003-2018 (investment), 2000-2017 (loans), 1992-2018 (trade), 1987-2016 (agricultural investment), 1998-2018 (contracts) |

|

China-Latin America Finance Database |

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

Loans and Grants |

2005-2018 |

|

China's Global Energy Finance |

Global Development Policy Center of Boston University (Gallagher 2018) |

Global |

Financing for Fossil Fuel, Nuclear Power, and Renewable Energy Projects |

2000-2019 |

|

China's Transport Infrastructure Investment in LAC |

Inter-American Dialogue |

Latin America and the Caribbean |

|

2002-2018 |

|

Chinese Investment in Australia (CHIIA) Database |

|

Australia |

Investment |

2014-2018 |

|

China's Overseas Lending |

Horn, Reinhart, Trebesch 2019 |

Global |

Loans and Grants |

1949-2017 |

|

Chinese Aid in the Pacific/ Pacific Aid Map |

Lowy Institute for International Policy (Sydney, Australia) |

Pacific |

Loans and Grants |

2002-2016 |

|

Chinese Export Credit Agency Project Database (Competitiveness Reports) |

Export-Import Bank of the United States |

Global |

Export Loans by China's Export-Import Bank |

2013-2017 |

|

IMF Coordinated Direct Investment Survey (CDIS) |

International Monetary Fund (IMF) |

Global |

Inward and Outward Direct Investment Positions (Derived) |

2009-2018 |

|

IMF Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey (CPIS) |

International Monetary Fund (IMF) |

Global |

Portfolio Assets and Liabilities (Derived) |

2015-2018 |

|

Mapping China's Tech Giants |

Australian Strategic Policy Institute, International Cyber Policy Centre (Barton, Australia) |

Global |

Tracks the international projects of 12 companies from across China's ICT and biotech sectors |

2000-present |

|

MERICS Belt and Road Tracker |

Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) (Berlin, Germany) |

Belt and Road Initiative |

Investment, Construction, Lending, and Grants ($25 million and over) |

2013-present |

|

Monitor of Chinese OFDI in Latin America and the Caribbean |

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

Investment |

2000-2018 |

|

Reconnecting Asia |

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) |

Asia, Middle East, and Europe |

|

2006-present |

|

Statistical Bulletin of China's Outward Foreign Direct Investment |

|

Global |

Inward and Outward Direct Investment Flows and Positions |

2007-2015 |

|

U.S.-China Investment Hub |

Rhodium Group |

United States and China |

Investment |

Varies (1990-present) |

|

UNCTAD Bilateral FDI Statistics |

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) |

Global |

|

2001-2012 |

Source: Congressional Research Service (2020).

Appendix B.

China'

Congressional Research Service

15

Tracking China’s Global Economic Activities: Challenges and Issues for Congress

Appendix B. China’s FDI in the United States

s FDI in the United States

Table B-1. China'’s FDI Stock the United States

(in billions of current U.S. dollars)

Year

BEA

BEA (UBO)

MOFCOM/SAFE

AEI/HERITAGE

RG

2000

0.3

0.1

2001

0.5

0.1

2002

0.4

0.2

2003

0.3

0.3

2004

0.4

0.5

2005

0.6

1.7

2.5

2006

0.8

1.7

2.7

2007

0.6

1.9

10.1

3.0

2008

1.1

1.2

2.4

15.1

3.8

2009

1.6

2.0

3.3

23.3

4.5

2010

3.3

5.4

4.9

32.1

9.1

2011

3.6

9.2

9.0

34.3

13.9

2012

7.1

14.0

17.1

43.3

21.4

2013

7.9

13.3

21.9

59.4

35.6

2014

10.1

29.0

38.0

76.5

48.3

2015

14.7

33.1

40.8

92.9

63.6

2016

40.4

59.0

145.9

110.1

2017

39.5

58.0

170.9

139.8

2018

39.5

60.2

179.1

145.2

2019

182.3

148.3

(in billions of current U.S. dollars)

|

Year |

BEA |

BEA (UBO) |

MOFCOM/SAFE |

AEI/HERITAGE |

RG |

|

2000 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

|||

|

2001 |

0.5 |

0.1 |

|||

|

2002 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

|||

|

2003 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

|||

|

2004 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

|||

|

2005 |

0.6 |

1.7 |

2.5 |

||

|

2006 |

0.8 |

1.7 |

2.7 |

||

|

2007 |

0.6 |

1.9 |

10.1 |

3.0 |

|

|

2008 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

2.4 |

15.1 |

3.8 |

|

2009 |

1.6 |

2.0 |

3.3 |

23.3 |

4.5 |

|

2010 |

3.3 |

5.4 |

4.9 |

32.1 |

9.1 |

|

2011 |

3.6 |

9.2 |

9.0 |

34.3 |

13.9 |

|

2012 |

7.1 |

14.0 |

17.1 |

43.3 |

21.4 |

|

2013 |

7.9 |

13.3 |

21.9 |

59.4 |

35.6 |

|

2014 |

10.1 |

29.0 |

38.0 |

76.5 |

48.3 |

|

2015 |

14.7 |

33.1 |

40.8 |

92.9 |

63.6 |

|

2016 |

40.4 |

59.0 |

145.9 |

110.1 |

|

|

2017 |

39.5 |

58.0 |

170.9 |

139.8 |

|

|

2018 |

39.5 |

60.2 |

179.1 |

145.2 |

|

|

2019 |

182.3 |

148.3 |

Source: Congressional Research Service with data from the American Enterprise Institute/Heritage Foundation (AEI/Heritage)'Source: Congressional Research Service with data from the American Enterprise Institute/Heritage Foundation

(AEI/Heritage)’s China Global Investment Tracker; Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China (MOFCOM)'s ’s

Foreign Direct Investment Statistics; Rhodium Group (RG)'’s U.S.-China Investment Hub; and U.S. Department of Commerce,

Bureau of Economic Research (BEA)'’s Direct Investment by Country and Industry.

Notes: Not adjusted for inflation. BEA reports China's "’s “direct investment position"” in the United States (the value of direct investors'

investors’ equity in, and net outstanding loans to, their affiliates). BEA defines ultimate beneficial owner (UBO) as that person

or entity proceeding up a foreign parent'’s ownership chain that is not owned more than 50% by another person or entity. MOFCOM/SAFE'’s data are based on the IMF'’s BPM6 and OECD'’s BD4 guidelines. AEI only includes cumulative gross

transactions of $100 millionmil ion or more since 2005; RG includes cumulative gross FDI since 2000.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Mercator Institute for China Studies, "Mapping the Belt and Road Initiative: This is Where We Stand," July 6, 2018. |

| 2. |

See, for example, The Economist Intelligence Unit, "China's Expanding Investment in Global Ports," October 11, 2017. In certain aspects, some of China's economic activities may resemble development assistance. |

| 3. |

There are three broad areas of concern: (1) rapid increase/expansion, (2) types of activities (e.g., sensitive areas like infrastructure and technology), and (3) the terms of engagement (e.g., state firms, the promotion of Chinese industrial policies, indebtedness of host governments). |

| 4. |

See, for example, Sam Ellis, "China's Trillion-Dollar Plan to Dominate Global Trade," Vox, April 6, 2018. Other motivations for China's foreign investments include securing strategic resources, learning how to operate in a global marketplace, and currying favor with senior officials by advancing PRC initiatives, such as BRI. In terms of construction contracts, an important motivation is to provide employment for Chinese construction workers who now have insufficient projects on which to work within China's borders. |

| 5. |

In some cases, China's activities have heightened cultural backlash and resentment by the style that Chinese overseas investments and construction projects have been pursued, particularly in regard to the use of Chinese—rather than local—companies and workers. |

| 6. |

William Pacatte, "Be Afraid? Be Very Afraid?—Why the United States Needs a Counterstrategy to China's Belt and Road Initiative," International Security Program, Center for Strategic & International Studies, October 2018. |

| 7. |

See, for example: James Swan, "Africa-China Relations: The View from Washington," U.S. Department of State Archive, February 9, 2007; White House, Claudia E. Anyaso, "Implications of Chinese Economic Expansion in Africa," U.S. Department of State Archive, October 31, 2008; "Remarks by Vice President Pence at the 2018 APEC CEO Summit, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea," November 16, 2018; Eva Vergara, "Pompeo: China financing of Maduro prolongs Venezuela crisis," AP News, April 12, 2019. |

| 8. |

The Trump Administration and some Members of Congress have questioned the motives behind China's actions in the case of several individual projects with strategic implications, notably the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka and a port in Djibouti. After Sri Lanka found itself unable to repay Chinese loans, a PRC company, China Merchants Port Holdings Company, Ltd., acquired a majority stake in the company that operates the Hambantota port, and signed a concession agreement to operate the port for 99 years from 2017. |

| 9. |

Chinese projects typically involve a consortium of Chinese state firms who provide the full range of goods, labor and services for the projects that China finances. These projects are neither assistance—Chinese loans are typically not offered interest-free and tend to be issued at, or near, market terms—nor truly commercial, because repayments are often backed by collateral (e.g., energy, minerals, or commodities) commitments made to the Chinese government, including state firms designated by the Chinese government that might not even be party to the original transaction. The Chinese government generally offers preferential terms and absorbs much of the commercial risk for Chinese firms participating in these projects. |

| 10. |

This could occur, for example, in international fora, where the United States has had a leading role in setting the rules for international economic relations, or with respect to global markets and resources that China anticipates it will need to sustain its economic progress. |

| 11. |

The nature of the Chinese political system and major role of the state in its economy make it easier for China, in comparison to the United States, to deploy economic resources abroad in pursuit of economic and foreign policy aims. |

| 12. |

This report differentiates between investment and construction activities. "Investment" entails ownership and includes greenfield investments and mergers and acquisitions (M&A), but it does not include portfolio investment (e.g., securities). "Construction," on the other hand, refers to Chinese construction services performed in the host country. |

| 13. |

Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China (MOFCOM). |

| 14. |

American Enterprise Institute/Heritage Foundation (AEI). |

| 15. |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). |

| 16. |

The Economist Intelligence Unit, "Chinese Investment in Developed Markets: An Opportunity for Both Sides?" 2015. |

| 17. |

Some of China's development and infrastructure assistance programs have been termed "tied aid" or "mixed credits." Tied aid credits and mixed credits are two of the primary methods whereby governments provide their exporters with official assistance to promote exports. Tied aid credits include loans and grants which reduce the financing costs for exporters below market rates and which are tied to the procurement of goods and services from the donor country. Mixed credits combine concessional government financing (funds at below-market rates or terms) with commercial or near-commercial funds to produce lower than market-based interest rates and more lenient loan terms. These types of credits typically are tied to the procurement of goods and services from the donor country, and through them, foreign governments use their overseas assistance programs to influence procurement decisions in favor of their own exporters. The OECD's Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits—of which China is not a part—provides disciplines on tied aid. |

| 18. |

These are financial terms and conditions, such as down payments, maximum repayment terms, minimum interest rates, and country risk classifications; provisions on tied aid; notification procedures; and sector-specific terms and conditions, covering the export credits for ships, nuclear power plants, civil aircraft, renewable energies, and water projects. Military equipment, agricultural goods, and untied development aid are not covered by the Arrangement. |

| 19. |

In 2012, the United States and China established an International Working Group on Export Credits (IWG) to develop a new set of international guidelines for official export credit support. The White House, "White House Fact Sheet on U.S.-China Economic Relations," Press Release, November 12, 2014. More broadly, there are no international rules governing development finance comparable to those in the OECD that govern export credit financing among its members and other countries willing to join the OECD arrangement.. |

| 20. |

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), official development assistance (ODA) consists of disbursements of loans made on concessional terms and of grants by official agencies (including state and local governments) to promote economic development and welfare in recipient countries and territories. ODA includes loans with a grant element of at least 25%. It does not include military aid and transactions that have primarily commercial objectives (e.g., export credits). |

| 21. |

China offers little aid, and when it does, it is often tied—that is, aid combined with other investments and projects supported by Chinese firms, goods and services. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), concessional loans are "loans that are extended on terms substantially more generous than market loans. The concessionality is achieved either through interest rates below those available on the market or by grace periods, or a combination of these." |

| 22. |

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), "Development Assistance Committee," 2019. |

| 23. |

See James Scott, Seeing Like a State (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998), Chapter 1. |

| 24. |

Some recent studies have concluded that the data may not be fully capturing the extent of activity, suggesting that at times U.S. observers may be either underestimating and/or overestimating China's global economic reach. See, for example, Sebastian Horn, Carmen M. Reinhart, and Christoph Trebesch, "China Overseas Lending," NBER Working Paper Series 26050 (July 2019). |

| 25. |

See, for example, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)'s partnership with the College of William & Mary AidData Center for Development Policy. |