Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Changes from February 24, 2020 to July 6, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Contents

- Introduction

- Brazil's Political and Economic Environment

- Background

- Recession, Insecurity, and Corruption (2014-2018)

- Bolsonaro Administration (2019-Present)

- Amazon Conservation and Climate Change

- Brazilian Policies and Deforestation Trends

- Paris Agreement

- U.S.-Brazilian Relations

- Commercial Relations

- Recent Trade Negotiations

- Trade and Investment Flows

- Security Cooperation

- Counternarcotics

- Counterterrorism

- Defense Cooperation

- U.S. Support for Amazon Conservation

- Outlook

Summary

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

July 6, 2020

Occupying almost half of South America, Brazil is the fifth-largest and fifth-most-populous country in the world. Given its size and tremendous natural resources, Brazil has long had the

Peter J. Meyer

potential to become a world power and periodically has been the focal point of U.S. policy in

Specialist in Latin

Latin America. Brazil'’s rise to prominence has been hindered, however, by uneven economic

American Affairs

performance and political instability. After a period of strong economic growth and increased

international influence during the first decade of the 21st21st century, Brazil has struggled with a series of domestic crises in recent years. Since 2014, the country has experienced a deep

recession, record-high homicide rate, and massive corruption scandal. Those combined crises contributed to the controversial impeachment and removal from office of President Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016). They also discredited much of Brazil'’s political class, paving the way for right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro to win the presidency in October 2018.

Since taking office in January 2019, President Jair Bolsonaro has begun to implement economic and regulatory reforms favored by international investors and Brazilian businesses and has proposed hard -line security policies intended to reduce crime and violence. Rather than building a broad-based coalition to advance his agenda, however, Bolsonaro has sought to keep the electorate polarized and his political base mobilized by taking socially conservative stands on cultural issues and verbally attacking perceived enemies, such as the press, nongovernmental organizations, and other branches of government. This confrontational approach to governance has alienated potential allies within the conservative-leaning congress and hindered Brazil’s ability to address serious challenges, such as the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and

accelerating deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. It also has placed additional stress on the country’s already strained democratic institutions. With the novel coronavirus spreading rapidly throu ghout the country and the economy projected to contract 9.1% in 2020, Brazilians have taken to the streets both in opposition to, and in support of, Bolsonaro. According to a

poll conducted in late June 2020, 32% of Brazilians consider Bolsonaro’s performance in office “good” or “great,” 23%

consider it “average,” and 44% consider it “bad” or “terrible.”

In international affairs, the Bolsonaro Administration has moved away from Brazil’October 2018.

|

Brazil at a Glance Population: 210.7 million (2019 est.) Race/Ethnicity: White—47.7%, Mixed Race—43.1%, Black—7.6%, Asian—1.1%, Indigenous—0.4% (Self-identification, 2010) Religion: Catholic—65%, Evangelical Christian—22%, None—8%, Other—4% (2010) Official Language: Portuguese Land Area: 3.3 million square miles (slightly smaller than the United States) Gross Domestic Product (GDP)/GDP per Capita: $1.85 trillion/$8,797 (2019 est.) Top Exports: oil, soybeans, iron ore, meat, and machinery (2019) Life Expectancy at Birth: 76 years (2018) Poverty Rate: 11.2% (2017) Leadership: President Jair Bolsonaro, Vice President Hamilton Mourão, Senate President Davi Alcolumbre, Chamber of Deputies President Rodrigo Maia Sources: Population, race/ethnicity, religion, land area, and life expectancy statistics from the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; GDP estimates from the International Monetary Fund; export data from Global Trade Atlas; and poverty data from Fundação Getúlio Vargas. |

Since taking office in January 2019, President Bolsonaro has maintained the support of his political base by taking socially conservative stands on cultural issues and proposing hard-line security policies intended to reduce crime and violence. He also has begun implementing economic and regulatory reforms favored by international investors and Brazilian businesses. Bolsonaro's confrontational approach to governance has alienated many potential congressional allies, however, slowing the enactment of his policy agenda. Brazilian civil society groups also have pushed back against Bolsonaro and raised concerns about environmental destruction and the erosion of democratic institutions, human rights, and the rule of law in Brazil.

In international affairs, the Bolsonaro Administration has moved away from Brazil's traditional commitment to autonomy and toward alignment with the United States. Bolsonaro has coordinated closely with the Trump Administration on regional challenges such as the crisis in Venezuela. On other matters, such as commercial ties with China, Bolsonaro has adopted a pragmatic approach intended to ensure continued access to Brazil'’s major export markets. The Trump Administration has welcomed Bolsonaro'’s rapprochement and sought to strengthen U.S.-Brazilian relations. In 2019, the Trump Administration took steps to bolster bilateral cooperation on counternarcotics and counterterrorism efforts and designated Brazil as a major non-NATO allymajor non-NATO ally. The United States and Brazil also agreed to several measures intended to facilitate trade and investment. Nevertheless, some Brazilians have questioned the benefits of partnership with the United States, as the Trump Administration has maintained certain import restrictions and threatened to impose tariffs on other key Brazilian products.

The 116thBrazilian analysts and former officials have questioned whether alignment with the United States is the most effective way to advance Brazil’s national interests.

The 116th Congress has expressed renewed interest in Brazil and U.S.-Brazilian relations. Environmental conservation has been a major focus, with Congress appropriating $15 million for foreign assistance programs in the Brazilian Amazon, including $5 million to address fires in the region, in the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94). Likewise, Members introduced legislative proposals that would express support for Amazon conservation efforts (S.Res. 337337) and restrict U.S. defense and trade relations with Brazil in response to deforestation (H.R. 4263). Congress also has expressed concerns about the state of democracy and human rights in Brazil. A provision of the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2020 (P.L. 116-92) directs) directed the Secretary of Defense, in coordination with the Secretary of State, to submit a report to Congress regarding Brazil'’s human rights climate and U.S.-Brazilian security cooperation. Another resolution (H.Res. 594) would express concerns about threats to human rights, the rule of law, democracy , and the environment in Brazil.

Introduction

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 27 link to page 28 link to page 5 link to page 11 link to page 16 link to page 23 link to page 29 Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Brazil’s Political and Economic Environment ...................................................................... 3

Background .............................................................................................................. 3 Recession, Insecurity, and Corruption (2014-2018) ......................................................... 4 Bolsonaro Administration (2019-Present) ...................................................................... 6

Pandemic Response .............................................................................................. 7 Democracy, Human Rights, and the Rule of Law....................................................... 8

Economic Policy ................................................................................................ 10 Security Policy................................................................................................... 10

Amazon Conservation and Climate Change....................................................................... 11

Brazilian Policies and Deforestation Trends ................................................................. 12 Paris Agreement ...................................................................................................... 14

U.S.-Brazilian Relations................................................................................................. 15

Commercial Relations .............................................................................................. 17

Recent Trade Negotiations ................................................................................... 17 Trade and Investment Flows................................................................................. 19

Security Cooperation................................................................................................ 20

Counternarcotics ................................................................................................ 21 Counterterrorism ................................................................................................ 21

Defense Cooperation........................................................................................... 22

U.S. Support for Amazon Conservation....................................................................... 24

Outlook ....................................................................................................................... 25

Figures Figure 1. Map of Brazil .................................................................................................... 2 Figure 2. Confirmed Cases of COVID-19 ........................................................................... 8 Figure 3. Deforestation in Brazil’s Legal Amazon: 2004-2019 ............................................. 13 Figure 4. U.S. Trade with Brazil: 2008-2019 ..................................................................... 20

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 26

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Introduction

As the fifth-largest country and the ninth-

Brazil at a Glance

As the fifth-largest country and the ninth-largest economy in the world, Brazil plays an important role in global governance (see

Population: 211.6 mil ion (2020 est.)

an important role in global governance (see

Race/Ethnicity: White—47.7%, Mixed Race—43.1%,

Figure 1 for a map of Brazil). Over the past

Black—7.6%, Asian—1.1%, Indigenous—0.4% (Self-

20 years, Brazil has forged coalitions with

identification, 2010)

other large, developing countries to push

Religion: Catholic—65%, Evangelical Christian—22%,

for changes to multilateral institutions and

None—8%, Other—4% (2010)

to ensure that global agreements on issues

Official Language: Portuguese

ranging from trade to climate change

Land Area: 3.3 mil ion square miles (slightly smal er than

adequately protect their interests. Brazil

the United States)

also has taken on a greater role in

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)/GDP per Capita:

promoting peace and stability, contributing

$1.85 tril ion/$8,797 (2019 est.)

to U.N. peacekeeping missions and

Top Exports: oil, soybeans, iron ore, meat, and

other large, developing countries to push for changes to multilateral institutions and to ensure that global agreements on issues ranging from trade to climate change adequately protect their interests. Brazil also has taken on a greater role in promoting peace and stability, contributing to U.N. peacekeeping missions and mediating conflicts in South America and mediating conflicts in South America and

machinery (2019)

further afield. Although recent domestic challenges have led Brazil

Life Expectancy at Birth: 76 years (2018)

chal enges have led Brazil to turn inward

Poverty Rate: 11.0% (2018 est.)

to turn inward and weakened its appeal globally, the country continues to exert considerable influence on international policy issues that affect the United States.

U.S. policymakers have often viewed Brazil as a natural partner in regional and global affairs, given its status as a fellow global y, the

Leadership: President Jair Bolsonaro, Vice President

country continues to exert considerable

Hamilton Mourão, Senate President Davi Alcolumbre,

influence on international policy issues that

Chamber of Deputies President Rodrigo Maia

affect the United States.

Sources: Population, race/ethnicity, religion, land area, and life expectancy statistics from the Instituto

U.S. policymakers have often viewed

Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; GDP estimates

Brazil as a natural partner in regional and

from the International Monetary Fund; export data from Global Trade Atlas; and poverty data from

global affairs, given its status as a fel ow

Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Centro de Políticas Sociais.

multicultural democracy. Repeated efforts

multicultural democracy. Repeated efforts to forge a close partnership have left both countries frustrated, however, as their occasionallyoccasional y divergent interests and policy approaches have inhibited cooperation. The Trump Administration has viewed the 2018 election of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro as a fresh opportunity to deepen the bilateral relationship. Bolsonaro has begun to shift Brazil'’s foreign policy to bring the country into closer alignment with the United

States, and President Trump has designated Brazil a major non-NATO allymajor non-NATO ally. Nevertheless, ongoing differences over trade protections and relations with China threaten to leave both the United

States and Brazil with unmet expectations once again.

The 116th

The 116th Congress has expressed renewed interest in Brazil, recognizing Brazil'’s potential to affect U.S. initiatives and interests. Some Members view Brazil as a strategic partner for addressing regional and global challenges chal enges. They have urged the Trump Administration to forge stronger economic, security, and military ties with Brazil to bolster the bilateral relationship and counter the influence of extra-hemispheric powers, such as China and Russia.11 Other Members

have expressed reservations about a close partnership with the Bolsonaro Administration. They are concerned that Bolsonaro is presiding over an erosion of democracy and human rights in Brazil Brazil and that his environmental policies threaten the Amazon and global efforts to mitigate

1 See, for example, Letter from Senator Marco Rubio to President Donald J. T rump, December 20, 2019, at https://www.rubio.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/e6199a08-c4d2-424b-9e48-676585575e34/035E152B8835E8734AA978266554751D.20191220 -letter-to-potus-re-brazil-.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

1

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

climate change.2climate change.2 Congress may continue to assess these differing approaches to U.S.-Brazilian relations as it carries out its oversight responsibilities and considers FY2021 appropriations and

other legislative initiatives.

Figure 1. Map of Brazil

Source: Map Resources. initiatives.

|

|

Source: Map Resources. Adapted by CRS Graphics. |

Brazil'Adapted by CRS Graphics.

2 See, for example, Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, “Climate Change,” Remarks in the Senate, Congressional Record, vol. 165, part 148 (September 16, 2019), p. S5496; and Letter f rom Honorable Richard E. Neal, Chairman, House Committee on Ways and Means, et al. to Honorable Robert Lighthizer, U.S. T rade Representative, June 3, 2020, at https://waysandmeans.house.gov/sites/democrats.waysandmeans.house.gov/files/documents/20200603_WM%20Dem%20Ltr%20to%20Amb%20Lighthizer%20re%20Brazil.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

2

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Brazil’s Political and Economic Environment

Background Brazil s Political and Economic Environment

Background

Brazil declared independence from Portugal in 1822, initially initial y establishing a constitutional monarchy and retaining a slave-based, plantation economy. Although the country abolished slavery in 1888 and became a republic in 1889, economic and political power remained

concentrated in the hands of large rural landowners and the vast majority of Brazilians remained outside the political system. The authoritarian government of Getúlio Vargas (1930-1945) began the incorporation of the working classes but exerted strict control over labor as part of its broader push to centralize power in the federal government. Vargas also began to implement a state-led development model, which endured for much of the 20th20th century as successive governments

supported the expansion of Brazilian industry.

Brazil

Brazil experienced two decades of multiparty democracy from 1945 to 1964 but struggled with political and economic instability, which ultimately led the military to seize power. A 1964 military

military coup, encouraged and welcomed by the United States, ushered in two decades of authoritarian rule.33 Although repressive, the military government was not as brutal as the dictatorships established in several other South American nations. It nominally allowednominal y al owed the judiciary and congress to function during its tenure but stifled representative democracy and civic action, carefully preserving its influence during one of the most protracted transitions to

democracy to occur in Latin America. Brazilian security forces killed more than 8,000 indigenous people andkil ed at least 434 political dissidents

during the dictatorship, and they detained and tortured an estimated 30,000-50,000 others.4

Brazil 4

Brazil restored civilian rule in 1985, and a national constituent assembly, elected in 1986,

promulgated a new constitution in 1988. The constitution established a liberal democracy with a strong president, a bicameral congress consisting of the 513-member chamber of deputies and the 81-member senate, and an independent judiciary. Power is somewhat decentralized under the country'country’s federal structure, which includes 26 states, a federal district, and some 5,570 municipalities.

Brazil

municipalities.

Brazil experienced economic recession and political uncertainty during the first decade after its political transition. Numerous efforts to control runaway inflation failed, and two elected presidents did not complete their terms; one died before taking office, and the other was

impeached on corruption charges and resigned.

The situation began to stabilize, however, under President Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995-2002) of the

center-right Brazilian Social Democracy Party (Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira, or PSDB). Initially Initial y elected on the success of the anti-inflation Real Plan that he implemented as finance minister under President Itamar Franco (1992-1994), Cardoso ushered in a series of market-oriented economic reforms. His administration privatized some state-owned enterprises, graduallygradual y opened the economy to foreign trade and investment, and adopted the three main pillars pil ars of Brazil'’s macroeconomic policy: a floating exchange rate, a primary budget surplus, and an

3 For information on U.S. policy prior to and following the coup, see Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXXI, South and Central America; Mexico, eds. David C. Geyer and David H. Herschler (Washington: GPO, 2004), Documents 181-244, at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v31/ch5. 4 At least 8,350 indigenous Brazilians also were killed during the dictatorship, either directly by government agents or indirectly as a result of government policies. Ministério Público Federal, Procuradoria Federal dos Direitos do Cidadão, “PFDC Contesta Recomendação de Festejos ao Golpe de 64,” press release, March 26, 201 9; and Relatório da Com issão Nacional da Verdade, December 10, 2014, at http://cnv.memoriasreveladas.gov.br/.

Congressional Research Service

3

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

s macroeconomic policy: a floating exchange rate, a primary budget surplus, and an inflation-targeting monetary policy. Nevertheless, the Brazilian state maintained an influential

role in the economy.

The Cardoso Administration'’s economic reforms and a surge in international demand

(particularly from China) for Brazilian commodities—such as oil, iron, and soybeans—fostered a period of strong economic growth in Brazil during the first decade of the 21st21st century. The center-left Workers'’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, or PT) administration of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula, 2003-2010) used increased export revenues to improve social inclusion and reduce inequality. Among other measures, the PT-led government expanded social welfare

programs and raised the minimum wage by 64% above inflation.55 Between 2003 and 2010, the Brazilian Brazilian economy expanded by an average of 4.1% per year and the poverty rate fell fel from 28.2% to 13.6%.66 The growth of the middle class fueled a domestic consumption boom that reinforced Brazil'Brazil’s economic expansion. Although the poverty rate initially initial y continued to decline under the PT-led administration of President Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016)—reaching a low of 8.4% in

2014—socioeconomic conditions deteriorated during Rousseff'’s final two years in office.7

7 Recession, Insecurity, and Corruption (2014-2018)

After nearly two decades of relative stability, Brazil has struggled with a series of crises since 2014. The country fell fel into a deep recession in late 2014, due to a decline in global commodity prices and the Rousseff Administration'’s economic mismanagement.88 Brazil'’s real gross domestic product (GDP) contracted by 8.2% over the course of 2015 and 2016.99 Although Brazil emerged from recession in mid-2017, recovery has been slow. The economy expanded by just over 1% in 2017 and 2018, and unemployment, which peaked at 13.7% in the first quarter of 2017, has

remained above 1011% for nearly four years.1010 Largely due to the weak labor market, the real incomes of the bottom half of Brazilian workers have declined by 17% sincebetween the onset of the recession, pushing more than 6 million and mid-2019, pushing an estimated 6 mil ion people into poverty.1111 The downturn has disproportionately affected Afro-Brazilians, who comprise about halfcomprised an estimated 56% of the Brazilian population but 64% of the unemployed.12 in 2018.12 Large fiscal deficits at all al levels of government have exacerbated the

situation, limiting the resources available to provide social services.

The deep recession also has hindered federal, state, and local government efforts to address serious challengeschal enges such as crime and violence. A record-high 64,000 Brazilians were killed kil ed in 2017, and

5 Cristiano Romero, “O Legado de Lula na Economia,” Valor Online, December 29, 2010. 6 International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Economic Outlook Database October 2019, October 11, 2019. T he poverty line is defined as the income necessary to cover basic expenses, such as food, clothing, housing, and transit. Marcelo Neri, A Escalada da Desigualdade, Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Centro de Políticas Sociais, August 2019, p. 15. Hereinafter, Neri, A Escalada da Desigualdade.

7 Neri, A Escalada da Desigualdade. 8 Alfredo Cuevas et al., “An Eventful T wo Decades of Reforms, Economic Boom, and a Historic Crisis,” in Brazil: Boom , Bust, and the Road to Recovery, IMF, 2018; and Pedro Mendes Loureiro and Alfredo Saad-Filho, “ T he Limits of Pragmatism: T he Rise and Fall of the Brazilian Workers’ Party (2002-2016),” Latin American Perspectives, vol. 46, no. 1 (2019).

9 IMF, Staff Report for the 2018 Article IV Consultation, June 20, 2018. 10 IMF, “World Economic Outlook Database: October 2019,” October 11, 2019; and Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), “ PNAD Contínua: T axa de Desocupação é de 12,6% e T axa de Subutilização é de 25,6% no T rimestre Encerrado em Abril de 2020,” press release, May 28, 2020.

11 Neri, A Escalada da Desigualdade, pp. 5, 15. 12 In 2018, 46.5% of Brazilians self-identified as mixed race and 9.3% self-identified as black. IBGE, Desigualdades Sociais por Cor ou Raça no Brasil, 2019, p. 2.

Congressional Research Service

4

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

in 2017, and the country'’s homicide rate of 30.9 per 100,000 residents was more than five times the global average. Although homicides declined by nearly 11% in 2018, feminicide (gender-motivated murders of women) and reports of sexual violence increased.1313 The deterioration in the security situation, like the economic crisis, has disproportionately affected Afro-Brazilians, who account for more than 75% of homicide victims, 75% of those killed by police, and 61% of feminicide victims.14

were the

victims of more than 75% of homicides and 61% of feminicides in 2017 and 2018.14

A series of corruption scandals have further discredited the country'’s political establishment. The so-calledcal ed Car Wash (Lava Jato) investigation, launched in 2014, has implicated politicians from across the political spectrum and many prominent business executives. The initial investigation revealed

that political appointees at the state-controlled oil company, Petróleo BrasileiroBrasileiro S.A. (Petrobras), colluded with construction firms to fix contract bidding processes. The firms then provided kickbacks to Petrobras officials and politicians in the ruling coalition. ParallelParal el investigations have discovered similar practices throughout the public sector, with businesses providing bribes and illegal il egal campaign donations in exchange for contracts or other favorable government treatment. The scandals sapped President Rousseff'’s political support, contributing to her controversial

impeachment and removal from office in August 2016.1515 Michael Temer, who presided over a center-right government for the remainder of Rousseff'’s term (2016-2018), was entangled in several corruption scandals but managed to hold on to power. Several other high-level politicians, including former President Lula, have been convicted for corruption and face potential yand face potentially lengthy

prison sentences (see the text box, below).

Lula’prison sentences (see the text box, below).

The inability of Brazil's political leadership to overcome these crises has undermined Brazilians' confidence in their democratic institutions. As of mid-2018, 33% of Brazilians expressed trust in the judiciary, 26% expressed trust in the election system, 12% expressed trust in congress, 7% expressed trust in the federal government, and 6% expressed trust in political parties. Moreover, only 9% of Brazilians expressed satisfaction with the way democracy was working in their country—the lowest percentage in all of Latin America.16

Lula's Imprisonment and Release s Imprisonment and Release

Brazilian prosecutors

Sources: Letter from |

The inability of Brazil’s political leadership to overcome these crises undermined Brazilians’ confidence in their democratic institutions. As of mid-2018, 33% of Brazilians expressed trust in the judiciary, 26% expressed trust in the election system, 12% expressed trust in congress, 7% expressed trust in the federal government, and 6% expressed trust in political parties. Moreover,

13 Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, Anuário Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, 2019; and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Study on Hom icide, 2019.

14 Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, “Violence Against Black People in Brazil,” infographic, 2019, at http://www.forumseguranca.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/infografico-consicencia-negra-2019-FINAL_ingl%C3%AAs_site.pdf.

15 Felipe Nunes and Carlos Ranulfo Melo, “Impeachment, Political Crisis and Democracy in Brazil,” Revista de Ciencia Política, vol. 37, no. 2 (2017).

Congressional Research Service

5

link to page 10 link to page 11 Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

only 9% of Brazilians expressed satisfaction with the way democracy was working in their

country—the lowest percentage in al of Latin America.16

Bolsonaro Administration (2019-Present) Brazilian Bolsonaro Administration (2019-Present)

Brazilian voters registered their intense dissatisfaction with the situation in the country in the 2018 elections. In addition to ousting 75% of incumbents running for reelection to the senate and 43% of incumbents running for reelection to the chamber of deputies, they elected as president, Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right congressman and retired army captain.1717 Prior to the election, most

observers considered Bolsonaro to be a fringe figure in the Brazilian congress. He exercised little influence over policy and was best known for his controversial remarks defending the country's ’s military dictatorship (1964-1985) and expressing prejudice toward marginalized sectors of Brazilian society.18Brazilian society.18 Backed by the small smal Social Liberal Party (PSL), Bolsonaro also lacked the finances and party machinery of his principal competitors. Nevertheless, his social media-driven campaign and populist, law-and-ordertough-on-crime message attracted a strong base of support. He outflanked

his opponents by exploiting anti-PT and antiestablishment sentiment and aligning himself with the few institutions that Brazilians still generally stil general y trust: the military and the churches.1919 Bolsonaro largely remained off the campaign trail in the weeks leading up to the election after being stabbed in an assassination attempt, but he easily defeated the PT'’s Fernando Haddad 55%-45% in a

second-round runoff. Bolsonaro'’s PSL also won the second-most seats in the lower house.

Since Bolsonaro began his four-year term on January 1, 2019, he has struggled to advance portions of his agenda due to cabinet infighting and the lack of a working majority in Brazil's ’s fragmented congress, which includes 24 political parties.2020 Whereas previous Brazilian presidents stitched together

stitched governing coalitions together by distributing control of government jobs and resources to parties in exchange for their support, Bolsonaro has refusedinitial y was unwil ing to enter into such arrangements. Moreover, he generallygeneral y has avoided negotiating the details of his proposed policies policy proposals with legislators. Instead, Bolsonaro has sought to keep his political base mobilized by frequently taking sociallytaking social y conservative stands on cultural issues and verballyverbal y attacking perceived enemies, such as

the press, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and other branches of government.21 Bolsonaro's confrontational approach to governance has21 Bolsonaro’s attacks have grown more strident since March 2020, as he has faced widespread scrutiny over his erratic response to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and his al eged attempts to interfere in law enforcement investigations to protect his family and al ies (see

“Pandemic Response” and “Democracy, Human Rights, and the Rule of Law,” below).

Bolsonaro’s confrontational approach to governance and recent scandals have alienated many of his potential alliesal ies within the conservative-leaning congress, as wel as some former supporters. . In November 2019, for example, Bolsonaro abandoned the PSL after a series of disagreements with the party's leadership; he intends to create a new Alliance In November 2019, for example, Bolsonaro abandoned the PSL after a series of disagreements 16 Corporación Latinobarómetro, Informe 2018, November 2018. 17 Sylvio Costa and Edson Sardinha, “O que Você Precisa Saber para Entender o Novo Congresso Brasileiro,” Congresso em Foco, October 9, 2018.

18 See, for example, Brian Winter, “System Failure: Behind the Rise of Jair Bolsonaro,” Americas Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 1, (January 2018). 19 Matias Spektor, “It’s Not Just the Right T hat’s Voting for Bolsonaro. It ’s Everyone.” Foreign Policy, October 26, 2018. As of mid-2018, 58% of Brazilians expressed trust in the military and 73% expressed trust in the churches, according to Corporación Latinobarómetro.

20 Câmara dos Deputados, “Bancada Atual,” accessed in June 2020. 21 See, for example, Andres Schipani, “Brazil: Jair Bolsonaro Pushes Cult ure War over Economic Reform,” Financial Tim es, August 24, 2019; and Paulo T revisani, “ Brazil’s President Hits the Street, Railing Against the Media,” Wall Street Journal, February 11, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

6

link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 11 link to page 11 Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

with the party’s leadership; he intends to create a new Al iance for Brazil party to contest future elections. In May 2020, Bolsonaro reportedly began distributing government positions to several large patronage-based parties in an attempt to ward off impeachment.22 Although Bolsonaro appears to have sufficient congressional support to hold onto the presidency for the time being, he stil lacks a working majority to advance his policy agenda (see “Economic Policy” and “Security Policy,” below). Public opinion remains polarized, with Brazilians taking to the streets both in

opposition to, and in support of, Bolsonaro. According to a poll conducted in late June 2020, 32% of Brazilians consider Bolsonaro’s performance in office “good” or “great,” 23% consider it

“average,” and 44% consider it “bad” or “terrible.”23

Pandemic Response

Brazil’s federal health ministry recognized the COVID-19 pandemic as a public health

emergency of national importance on February 3, 2020—nearly a month before Brazil confirmed its first coronavirus infection. By mid-March, the Bolsonaro Administration had begun to close Brazil’s international borders and had cal ed on the Brazilian Congress to declare a state of public

calamity in order to free up resources to address the pandemic’s health and economic effects.

Since then, however, President Bolsonaro has consistently downplayed the threat posed by COVID-19. He has criticized Brazilian states and municipalities for imposing containment measures and has argued that restrictions on economic activity are more damaging than the virus itself. He has issued several decrees to overturn local restrictions, but these decrees have been

blocked in court. Bolsonaro has repeatedly flouted public health guidelines, wading into crowds of supporters without a mask, even as nearly two dozen top officials in his government have tested positive for the virus.24 Bolsonaro also has clashed with members of his own administration, dismissing one health minister and provoking the resignation of another, due to his opposition to social distancing measures and his promotion of chloroquine and

hydroxychloroquine—two antimalarial drugs that have yet to be proven effective for treating

COVID-19.25

To date, Brazil’s efforts to contain the virus have been unsuccessful. As of July 5, 2020, Brazil

had recorded more than 1.6 mil ion cases and nearly 65,000 deaths from COVID-19 (see Figure 2).26 An epidemiological study based on antibody tests suggests the total number of Brazilians who have been infected by the virus may be six times higher than the number of official y confirmed cases. The study also found significant regional, socioeconomic, and ethnic/racial disparities in infection rates. For example, 1.1% of self-identified white Brazilians tested positive

for antibodies, compared to 2.1% of Brazilians of Asian descent, 2.5% of black Brazilians, 3.1% of mixed-race Brazilians, and 5.4% of indigenous Brazilians.27 Although Brazil has one of the strongest public health systems in Latin America, hospitals have been overwhelmed in some 22 André Shalders, “Bolsonaro terá ‘Centrão’, mas Impeachment pode Avançar se houver Apoio Popular, Dizem Autores de Pedido,” BBC News Brasil, May 7, 2020. 23 Datafolha, “Bolsonaro é Reprovado por 44%,” June 26, 2020. 24 “Unsealed Exams Confirm Bolsonaro Did Not Catch COVID-19,” Valor International, May 13, 2020; and “Bolsonaro Rallies with Supporters Amid Virus Surge,” Agence France Presse, May 24, 2020. 25 Mauricio Savarese, “Brazil’s Health Minister Resigns After One Month on the Job,” Associated Press, May 15, 2020; and Ernesto Londoño and Mariana Simões, “Defying Science, Brazil’s Leader T rumpets Unproven ‘Cure’,” New York Tim es, June 14, 2020.

26 Ministério da Saúde do Brasil, “Painel Coronavirus,” July 6, 2020, at https://covid.saude.gov.br/. 27 Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Centro de Pesquisas Epidemiológicas, “EPICOVID19-BR Divulga Novas Resultados Sobre o Coronavírus no Brasil,” July 2, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

7

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

cities, and the virus is now spreading rapidly throughout the interior of the country.28 The politicization of the pandemic and the lack of coordination among different levels of government

may have contributed to the country’s ineffective response.

Figure 2. Confirmed Cases of COVID-19

(new cases by date reported [February 26, 2020 – July 5, 2020])

Source: CRS presentation of data from the Brazilian government’s Ministério da Saúde, “Painel Coronavirus,” July 6, 2020, at https://covid.saude.gov.br/.

Democracy, Human Rights, and the Rule of Law

Many analysts argue there has been an erosion of democracy in Brazil under Bolsonaro.29 Since taking office, the president has continued to celebrate Brazil’s military dictatorship, and his

sons—who play an influential role in his government—have questioned democracy and suggested authoritarian measures may be necessary in certain circumstances.30 Bolsonaro also has attended ral ies in which some of his supporters have cal ed on the military to close congress and

the supreme court.31

28 Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Nuclear T hreat Initiative, and Economist Intelligence Unit, Global Health Security Index, 2019; and “ Cidades do Interior já Respondem por quase 60% dos Casos de Covid no País,” Folha de São Paulo, June 22, 2020. 29 Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, Autocratization Surges – Resistance Grows: Democracy Report 2020, March 20, 2020; and “ Brasil está em Processo de Erosão, Dizem Brasilianistas,” Valor, June 12, 2020.

30 Rodrigo Borges Delfim and T hais Arbex, “Carlos Bolsonaro Diz que País Não T erá T ransformação Rápida por Vias Democráticas,” Folha de São Paulo, September 9, 2019; and “ Eduardo Bolsonaro Fala em Novo AI-5 ‘se Esquerda Radicalizar’,” UOL, October 31, 2019 31 T errence McCoy and Heloísa T raiano, “As Brazil’s Challenges Multiply, Bolsonaro’s Fans Call for a Military T akeover,” Washington Post, May 11, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

8

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Civil-military relations have shifted as Bolsonaro has appointed retired and active-duty military officers to lead more than a third of his cabinet ministries and to approximately 3,000 other positions throughout the government.32 The Brazilian armed forces are now more involved in governance than they have been at any time since the end of the dictatorship. Although some analysts maintain that the officers have had a moderating influence on Bolsonaro, others are concerned about politicization of the armed forces. On several occasions, Bolsonaro and members

of his administration have appeared to suggest that the armed forces would back the president if

the Brazilian congress or judiciary sought to remove him from office.33

Bolsonaro also has exerted political influence over law enforcement agencies, potential y hindering investigations and cal ing into question the independence of Brazilian institutions. Minister of Justice and Public Security Sérgio Moro resigned in April 2020 after Bolsonaro dismissed the director-general of the Brazilian federal police, al egedly to push for certain appointments within the force and gain access to confidential information regarding ongoing investigations. Bolsonaro denied the al egations, but his newly appointed director-general

immediately replaced the head of the federal police office in Rio de Janeiro, which reportedly is investigating potential corruption and money laundering by two of Bolsonaro’s sons. The federal police also are investigating dozens of Bolsonaro’s political al ies—and reportedly at least one of his sons—for their al eged involvement in an il egal digital disinformation campaign.34 In addition to his federal police appointments, observers have questioned changes Bolsonaro has

made to Brazil’s tax collection agency, financial intel igence unit, and antitrust regulator, as wel as his decision to disregardelections.

During its first year in office, the Bolsonaro Administration began implementing key aspects of its market-oriented economic agenda. As part of a far-reaching privatization program, the Brazilian government began selling off assets, including subsidiaries of state-owned enterprises, stakes in private companies, and infrastructure and energy concessions, yielding revenues of approximately $66 billion in 2019.22 The Brazilian congress also enacted a major pension reform expected to reduce government expenditures by at least $194 billion over the next decade.23 Those policies build on a 2016 constitutional amendment that froze inflation-adjusted government spending for 20 years. Although the Bolsonaro Administration has proposed additional measures to simplify the tax system, cut and decentralize government expenditures, and decrease compensation and job security for government employees, political parties may be reluctant to enact austerity measures in the lead-up to Brazil's October 2020 municipal elections. The International Monetary Fund estimates that the Brazilian economy expanded by 1.2% in 2019 and will expand by 2.2% in 2020, due to improved business sentiment following recent market-oriented policy changes.24 About 11% of Brazilians remain unemployed,25 however, and some economists argue that rather than reducing the size of the state, Brazil should reorient expenditures to programs that protect the most vulnerable and to productivity-enhancing investments, such as education, training, and infrastructure.26

Bolsonaro has had difficulty advancing the hard-line security platform that was the centerpiece of his campaign. The Brazilian congress has blocked Bolsonaro's proposal to shield from prosecution police who kill suspected criminals and has pushed back against Bolsonaro's decrees loosening gun controls. Other Bolsonaro Administration proposals, including measures to modernize police investigations and impose stricter criminal sentences, were enacted in December 2019. Preliminary data suggest that security conditions in Brazil improved in 2019, but the number of individuals killed by police in states such as Rio de Janeiro increased significantly.27 The Bolsonaro Administration has claimed credit for falling crime rates, but some security analysts argue the situation has been improving since late 2017 due to state and municipal initiatives and reduced conflict between the country's largest criminal groups.28 (See the "Counternarcotics" section for more information.)

Anti-corruption efforts in Brazil have experienced a series of recent setbacks. Although President Bolsonaro campaigned on an anti-corruption platform, he has repeatedly interfered in law enforcement agencies, potentially hindering investigations and calling into question the political independence of Brazilian institutions. In August 2019, he dismissed the head of the Brazilian federal police office in Rio de Janeiro, which is investigating potential corruption and money laundering by Bolsonaro's son, Flávio. In September 2019, Bolsonaro disregarded a norm in place since 2003 of selecting an attorney general from a a norm in place since 2003 of selecting an attorney general from a

shortlist approved by the public prosecutors' association. Observers also have questioned changes Bolsonaro has made to Brazil's tax collection agency, financial intelligence unit, and antitrust regulator. At the same time, the Brazilian congress has been reluctant to adopt anti-corruption reforms and the supreme court has issued a series of rulings that could jeopardize convictions obtained in the Car Wash investigation and make it more difficult to investigate and prosecute corruption cases.29

Many analysts argue there has been an erosion of democracy in Brazil under Bolsonaro.30 During his first year in office, the president continued to celebrate Brazil's military dictatorship and those installed in other South American countries, and his sons and members of his administration occasionally suggested they could impose authoritarian measures under certain circumstances. Bolsonaro also took steps to weaken the press, exert control over civil society, and roll back rights previously granted to marginalized groups.31 Civil-military relations have shifted as Bolsonaro has appointed retired and active-duty officers to lead more than a third of his cabinet ministries and to dozens of other positions throughout the government. The Brazilian military is now more involved in politics than it has been at any time since the end of the dictatorship. Some analysts maintain, however, that the military has had a moderating influence on the government.32 Brazil's civil society, congress, and judiciary also have served as checks on Bolsonaro. Nevertheless, human rights advocates argue the president's statements and actions have fueled attacks against journalists and activists.33

Polls conducted at the conclusion of his first year in office suggest Brazilian public opinion toward Bolsonaro remains divided. About 32% of Brazilians consider Bolsonaro's government "good" or "great," 32% consider it "average," and 35% consider it "bad" or "terrible."34

’ association.35

Observers have raised serious concerns about human rights in Brazil as Bolsonaro has taken steps to weaken the press, exert control over NGOs, and roll back rights previously granted to marginalized groups.36 Brazil’s civil society has pushed back against such measures, many of which have been blocked by the Brazilian congress and judiciary. Nevertheless, human rights advocates argue the president’s statements and actions have fueled attacks against journalists,

activists, and indigenous and quilombola communities.37

32 Anthony Boadle, “ Analysis – T hreat of Brazil Military Coup Unfounded, Retired Generals Say,” Reuters, June 22, 2020.

33 “Bolsonaro: Forças Armadas Defendem a Pátria e ‘Não Cumprem Ordens Absurdas’,” UOL, June 12, 2020; and Ricardo Brito, “Brazil’s Bolsonaro Says Military Will Not Remove Elected President,” Reuters, June 15, 2020. 34 “Moro Plunges Knife into Bolsonaro as COVID-19 Swamps Brazil,” Latin American Weekly Report, April 30, 2020; “Brazil: Police Investigate Bolsonaro’s Allies, T ensions Rise,” Latin News Daily, May 28, 2020; and “De ‘Rachadinha’ a Fantasmas, Conheça Investigações que Envolvem o Entorno de Jair Bolsonaro,” Folha de São Paulo, June 18, 2020. 35 Ryan C. Berg, “Brazil’s Bolsonaro Continues to Be His Own Worst Enemy,” American Enterprise Institute, September 24, 2019; and Guilherme France, Brazil: Setbacks in the Legal and Institutional Anti-Corruption Fram eworks, T ransparency International, 2019. 36 “Brazil: Print Media T hreatened by Presidential Decree,” Latin News Daily, August 8, 2019; Mauricio Savarese, “Brazil’s Bolsonaro T argets Minorities on 1st Day in Office,” Associated Press, January 3, 2019; and Gabriel Stargardter, “Bolsonaro Presidential Decree Grants Sweeping Powers over NGOs in Brazil,” Reuters, January 2, 2019. 37 Quilombolas are a self-declared ethno-racial group, some of whom are the descendants of freed or escaped slaves. For more information, see Mariana Nozela Prado, “Quilombola Communities of Brazil,” Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Brazil Institute, infographic, August 13, 2018, at https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/quilombola-communities-brazil. “ Brazil: Journalists Denounce Increased Attacks,” Latin News Daily, January 17, 2020; Maria Elena Bucheli, “ Bolsonaro ‘T urned Me into a Pariah,’ Says Gay Lawmaker Who Fled Brazil,” Agence France Presse, March 20, 2019; and “Brazil: Indigenous Violence on the Rise,” Latin American Security & Strategic Review, January 2020.

Congressional Research Service

9

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Economic Policy

During its first year in office, the Bolsonaro Administration began implementing key aspects of its market-oriented economic agenda. As part of a far-reaching privatization program, the Brazilian government began sel ing off assets, including subsidiaries of state-owned enterprises, stakes in private companies, and infrastructure and energy concessions, yielding revenues of

approximately $66 bil ion in 2019.38 The Brazilian congress also enacted a major pension reform expected to reduce government expenditures by at least $194 bil ion over the next decade.39 Those policies built on a 2016 constitutional amendment that froze inflation-adjusted government spending for 20 years. Other Bolsonaro Administration proposals to simplify the tax system, cut and decentralize government expenditures, and decrease compensation and job security for government employees had yet to move forward in congress when legislators shifted their focus

to addressing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although the International Monetary Fund had expected Brazil’s economic growth to accelerate

from 1.1% in 2019 to 2.2% in 2020, it now forecasts a 9.1% contraction.40 According to one projection, the unemployment rate, which was already above 12% before the onset of the pandemic, wil average nearly 19% over the course of the year.41 The Brazilian congress has enacted a series of emergency measures to mitigate the economic and social impacts of the recession, including an expansion of a conditional cash transfer program for low-income Brazilians, new monthly cash transfers for informal and unemployed workers, credit and payroll

assistance for smal - and medium-sized businesses, and aid for state and municipal governments. Altogether, the government’s fiscal response is equivalent to more than 6% of GDP.42 The Brazilian Central Bank has provided additional support for the economy by cutting the benchmark interest rate to a historic low and implementing measures to increase the liquidity of

the financial system.

Bolsonaro Administration officials and some economists assert that Brazil should quickly withdraw the emergency measures and enact pending structural reforms once the economy begins to recover.43 They argue that reducing Brazil’s fiscal deficit and stabilizing public debt are

necessary to attract private investment and foster economic growth. Other economists argue that the pandemic and recession demonstrate the need for a stronger public health system, more comprehensive social safety net, and increased public investment in education, infrastructure, and

research and development.44

Security Policy

Bolsonaro has had difficulty advancing the hard-line security platform that was the centerpiece of his campaign. The Brazilian congress blocked Bolsonaro’s proposal to shield from prosecution

38 U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Brazil-U.S. Business Council, “What Can Brazil Expect from Concessions and Privatizations in 2020?,” Brazil Investment Monitor, February 14, 2020. 39 Andres Schipani and Bryan Harris, “Can Brazil’s Pension Reform Kick -Start the Economy?,” Financial Times, October 22, 2019.

40 IMF, Tentative Stabilization, Sluggish Recovery?, World Economic Outlook Update, January 2020; and IMF, A Crisis Like No Other, An Uncertain Recovery, World Economic Outlook, June 2020.

41 Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Insitituto Brasileiro de Economia, Boletim Macro, June 2020. 42 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), OECD Economic Outlook, June 2020. 43 “A Window of Opportunity for the Reforms,” Valor International, June 17, 2020; and OECD, OECD Economic Outlook, June 2020.

44 Laura Carvalho, “As Funçöes do Estado Reveladas pela Pandemia,” Nexo Jornal, April 30, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 24 Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

police who kil suspected criminals and pushed back against Bolsonaro’s decrees loosening gun controls. Other Bolsonaro Administration proposals, including measures to modernize police

investigations and impose stricter criminal sentences, were enacted in December 2019.

Preliminary data suggest that security conditions in Brazil improved in 2019, as the country registered a 19% decline in homicides. The number of individuals kil ed by police increased, however, including an 18% spike in the state of Rio de Janeiro.45 In recent years, more than 75% of those kil ed by police have been Afro-Brazilian.46 The Bolsonaro Administration has claimed credit for fal ing crime rates, but some security analysts argue the situation has been improving

since late 2017 due to state and municipal initiatives and reduced conflict between the country’s

largest criminal groups.47 (See the “Counternarcotics” section for more information.)

Amazon Conservation and Climate Change Amazon Conservation and Climate Change

A 30% increase in fires in the Brazilian Amazon in 2019 compared to the previous year led many Brazilians Brazilians and international observers to express concern about the rainforest and the extent to which its destruction is contributing to regional and global climate change.3548 Covering nearly 2.7 million

mil ion square miles across seven countries, the Amazon Basin is home to the largest and most biodiverse tropical forest in the world.3649 Scientific studies have found that the Amazon plays an important role in the global carbon cycle by absorbing and sequestering carbon. Although findings vary, one recent study estimated the forest absorbs 560 millionmil ion tons of carbon dioxide per year and its biomass holds 76 billion bil ion tons of carbon—an amount equivalent to seven years of

global carbon emissions.3750 The Amazon also pumps water into the atmosphere, affecting regional rainfall rainfal patterns throughout South America.3851 An estimated 17% of the Amazon basin has been deforested, however, and some scientists have warned that the forest may be nearing a tipping point at which it is no longer able to sustain itself and transitions to a drier, savanna-like ecosystem.39

ecosystem.52

45 “Número de Pessoas Mortas pela Polícia Cresce no Brasil em 2019; Assassinatos de Policiais Caem pela Met ade,” G1, Monitor da Violência, April 16, 2020; and Karina Nascimento, “ Principais Crimes Registraram Queda no Estado em 2019,” Governo do Rio de Janeiro, Instituto de Segurança Pública, January 21, 2020. 46 Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, “Violence Against Black People in Brazil,” infographic, 2019. 47 André Cabette Fábio, “A Queda da Criminalidade no Brasil. e o Discurso de Moro,” Nexo Jornal, January 6, 2020. 48 Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE), “Monitoramento dos Focos Ativos por Bioma,” at http://queimadas.dgi.inpe.br/queimadas/portal-static/estatisticas_estados/. For more information on the fires, see CRS In Focus IF11306, Fire and Deforestation in the Brazilian Am azon , by Pervaze A. Sheikh et al.

49 Portions of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, and Venezuela are located in the Amazon Basin. T he rainforest extends beyond the Amazon Basin into Suriname and French Guiana. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Global International Waters Assessm ent: Am azon Basin, GIWA Regional Assessment 40b, Kalmar, Sweden, 2004, p. 15.

50 Edna Rödig et al., “T he Importance of Forest Structure for Carbon Fluxes of the Amazon Rainforest,” Environmental Research Letters, vol. 13, no. 5 (2018), p. 9; Hemholtz Centre for Environmental Research, “ The Forests of the Amazon Are an Important Carbon Sink,” press release, November 8, 2019; and Pierre Friedlingstein et al., “Global Carbon Budget 2019,” Earth System Science Data, vol. 11, no. 4 (2019), p. 1803. 51 D. C. Zemp et al., “Deforestation Effects on Amazon Forest Resilience,” Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 44, no. 12 (2017).

52 T homas Lovejoy and Carlos Nobre, “Amazon T ipping Point: Last Chance for Action,” Science Advances, vol. 5, no. 12 (2019).

Congressional Research Service

11

link to page 5 link to page 16 Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Efforts to conserve the forest often focus on Brazil, since the country encompasses about 69% of the Amazon Basin.4053 Within Brazil, the government has established an administrative zone known as the Legal Amazon, which includes nine states: Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Maranhão, Mato Grosso, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima, and Tocantins (seeTocantins, and most of Maranhão (see Figure 1). Although rainforest covers most of the Legal Amazon, savanna (Cerrado) and wetlands (Pantanal) are present in portions of the region. The Legal Amazon was largely undeveloped until the 1960s, when the military-led

government began subsidizing the settlement and development of the region as a matter of national security. PartiallyPartial y due to those incentives, the human population in the Legal Amazon grew from 6 million mil ion in 1960 to 25 million mil ion in 2010. Forest cover in the Legal Amazon has declined by approximately 20% as settlements, roads, logging, ranching, farming, and other

activities have proliferated in the region.41

54 Brazilian Policies and Deforestation Trends

In 2004, the Brazilian government adopted an action plan to prevent and control deforestation in

the Legal Amazon.4255 It increased surveillancesurveil ance in the Amazon region, began to enforce environmental laws and regulations more rigorously, and took steps to consolidate and expand protected lands. Nearly 20% of the Brazilian Amazon now has some sort of federal or state protected status, and the Brazilian government has recognized an additional 22% of the Brazilian Amazon as indigenous territories.4356 Brazil'’s forest code also requires private landowners in the

Legal Amazon to maintain native vegetation on 80% of their properties.

Other Brazilian initiatives have sought to support sustainable development in the Amazon while limiting limiting the extent to which the country'’s agricultural sector drives deforestation. In 2008, the Brazilian

Brazilian government began conditioning credit on farmers'’ compliance with environmental laws; in 2009, the government banned new sugarcane plantations in the Legal Amazon. The Brazilian Brazilian government also supported private sector conservation initiatives. Those included a 2006 voluntary agreement among most major soybean traders not to purchase soybeans grown on lands deforested after 2006 (later revised to 2008) and a 2009 voluntary agreement among

meatpackers not to purchase cattle raised on lands deforested in the Amazon after 2008.

Brazil'

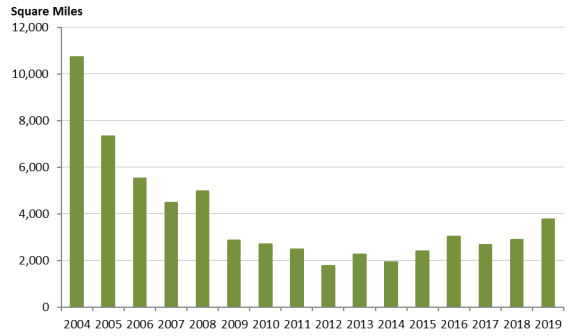

Brazil’s public and private conservation efforts, combined with economic factors that made agricultural commodity exports less profitable,4457 led to an 83% decline in deforestation in the

Legal Amazon between 2004 and 2012. Deforestation has been trending upward in recent years, however, rising from a low of 1,765 square miles in 2012 to 3,769911 square miles in the 12-month monitoring period that ended in July 2019 (seesee Figure 2)3). Analysts have linked the increase in deforestation to a series of policy reversals that have cut funding for environmental enforcement, reduced the size of protected areas, and relaxed conservation requirements.45 Market incentives, 58 Market incentives, 53 UNEP, Global International Waters Assessment: Amazon Basin, GIWA Regional Assessment 40b, Kalmar, Sweden, 2004, p. 16. 54 Eric A. Davidson et al., “ T he Amazon Basin in T ransition,” Nature, vol. 481 (2012), p. 321. 55 Presidência da República, Casa Civil, Plano de Ação para a Prevenção e Controle do Desmatamento na Amazônia Legal, March 2004. 56 Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information, “Amazonia 2019 – Protected Areas and Indigenous T erritories,” map, 2019. 57 Philip Fearnside, “Business as Usual: A Resurgence of Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon,” Yale Environment 360, April 18, 2017. Hereinafter, Fearnside, “ Business as Usual.”

58 Fearnside, “Business as Usual”; and William D. Carvalho et al., “Deforestation Control in the Brazilian Amazon: A Conservation Struggle Being Lost as Agreements and Regulations Are Subverted and Bypassed,” Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation, vol. 17, no. 3 (2019).

Congressional Research Service

12

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

such as the growth in Chinese imports of Brazilian beef and soybeans, also have contributed to recent deforestation trends.4659 For example, China purchased nearly 76% of its soybean imports from Brazil in 2018, up from roughly 50% in prior years, after imposing a retaliatory tariff on

U.S. soybeans.60

Figure 3U.S. soybeans.47

Although changes that weakened Brazil'’s environmental policies began under President Rousseff and continued under President Temer, some analysts argue that the Bolsonaro Administration's ’s approach to the Amazon has led to further increases in deforestation.4861 Bolsonaro has fiercely

defended Brazil'’s sovereignty over the Legal Amazon and its right to develop the region. Since taking office, his administration has lifted the ban on new sugarcane plantations in the Legal Amazon and calledcal ed for an end to the soy moratorium. It also has proposed measures to allowprovide property titles to individuals il egal y occupying public lands and to al ow commercial agriculture, mining, and hydroelectric projects in indigenous territories, arguing that such economic activities will . The Bolsonaro

59 Gustavo Faleiros, “China’s Brazilian Beef Demand Linked to Amazon Deforestation Risk,” Diálogo Chino, October 23, 2019; and Richard Fuchs et al., “U.S.-China T rade War Imperils Amazon Rainforest,” Nature, vol. 567 (March 28, 2019). 60 Marcos Caramuru de Paiva, “Brazil and China: A Brief Analysis of the State of Bilateral Relations,” in Brazil-China: The State of the Relationship, Belt and Road, and Lessons for the Future (Rio de Janeiro: Centro Brasileiro de Relações Internacionais, 2019), p. 122. Also see Fred Gale, Constanza Valdes, and Mark Ash, Interdependence of China, United States, and Brazil in Soybean Trade, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, June 2019.

61 Kathryn Hochstetler, “This Isn’t the First T ime Fires Have Ravaged the Amazon,” Foreign Policy, August 29, 2019; and Rubens Ricupero et al., Com unicado dos Ex-Ministros de Estado do Meio Am biente, May 8, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

13

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Administration argues that such economic activities wil benefit those living in the region and

benefit those living in the region and reduce incentives for illegal il egal deforestation.

At the same time, Bolsonaro has questioned the Brazilian government' government’s deforestation data and

scaled back environmental enforcement. He has removed several high-level officials from Brazil’s environmental monitoring and enforcement agencies, replacing them with appointees who al egedly have hampered enforcement efforts.62 In 2019, Brazil’s primary environmental enforcement agency reportedly issued 34% fewer environmental fines, reported 51% fewer

environmental crimes, and seized 61% less il egal y logged timber than it had in 2018.63

Thoses deforestation data and repeatedly criticized the agencies responsible for enforcing environmental laws.

Those statements and actions reportedly have emboldened some loggers, miners, and ranchers, contributing to the surge in fires in 2019 and a 3034% increase in deforestation in the annual monitoring period that included the first seven months of Bolsonaro'’s term.64 Bolsonaro initial ys term.49 Bolsonaro initially dismissed dismissed

environmental concerns about the Amazon, asserting that deforestation and burning are cultural practices that will wil never end.5065 In January 2020, however, he announced the creation of a new security force to protect the environment and a new Amazon Council, headed by Vice President Hamilton Mourão, to coordinate conservation and sustainable development efforts. As of the close of 2019, a majority (54%) of Brazilians disapproved of Bolsonaro's environmental policies.51

About 4,000 troops, police officers, and environmental agents have been deployed in the Amazon region as

part of an inter-agency enforcement operation since May 2020.66 The Bolsonaro Administration is

also reportedly drafting a new plan for combatting il egal deforestation.

Paris Agreement Paris Agreement

The rising levels of Amazon deforestation call cal into question whether Brazil will wil meet its Paris Agreement commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 37% below 2005 levels (to 1.3 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO₂e) by 2025.5267 According to a 2018 assessment by the U.N. Environment Program, Brazil'’s greenhouse gas emissions declined by 12% per year

from 2006 to 2016, as significant declines in deforestation offset slight increases in emissions from other sources.5368 Those reductions had put Brazil on track to meet its Paris Agreement commitment, but emissions have begun to rise again due to increased deforestation. In 2018, Brazil'

62 Jack Spring and Stephen Eisenhammer, “Exclusive: As Fires Race through Amazon, Brazil’s Bolsonaro Weakens Environment Agency,” Reuters, August 28, 2019. 63 Danielle Brant and Phillippe Watanabe, “Sob Bolsonaro, Multas Ambientais Caem 34% para Menor Nível em 24 Anos,” Folha de São Paulo, March 9, 2020; and Ernesto Londoño, Manuela Andreoni, and Letícia Casado, “Amazon Deforestation Soars as Pandemic Hobbles Enforcement,” International New York Times, June 12, 2020. 64 Fabiano Maisonnave, “Declarações Antiambientalistas de Políticos Aceleram Desmatamento, Diz Estudo,” Folha de São Paulo, December 16, 2019; Stephen Eisenhammer, “ ‘Day of Fire’: Blazes Ignite Suspicion in Amazon T own,” Reuters, September 11, 2019; Marina Lopes, “ Illegal Miners, Feeling Betrayed, Call on Bolsonaro to End Environmental Crackdown in Amazon,” Washington Post, September 10, 2019; and INPE, “A T axa Consolidada de Desmatamento por Corte Raso para os Nove Estados da Amazônia Legal (AC, AM , AP, MA, MT , PA, RO, RR e T O) em 2019 é de 10.129 km2,” press release, June 9, 2020.

65 “Bolsonaro Diz que Desmatamento é Cultural no Brasil e Não Acabará,” Folha de São Paulo, November 20, 2019. 66 Claudia Safatle, Fernando Exman, and Malu Delgado, “Society Reacts to Crisis and Mourão Rules Out Coup,” Valor International, May 31, 2020.

67 Federative Republic of Brazil, Intended Nationally Determined Contribution, September 21, 2016. “CO₂e” is a metric used to express the impact of emissions from differing greenhouse gasses in a common unit by converting each gas to the equivalent amount of CO₂ that would have the same effect on increasing global average temperature.

68 UNEP, Emissions Gap Report 2018, November 2018, p. 9.

Congressional Research Service

14

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions increased by an estimated 0.3% (to 1.9 GtCO₂e), even as

s greenhouse gas emissions increased by an estimated 0.3% (to 1.9 GtCO₂e), even as emissions from the energy sector declined by nearly 5%.54

69

President Bolsonaro had pledged to withdraw from the Paris Agreement during his 2018 election

campaign, but he reversed course following his inauguration, stating that Brazil would remain in the agreement "“for now."55”70 At the 25th25th Conference of Parties to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 25), Brazil pushed developed countries to meet their 2009 goal to mobilize $100 billion mobilize $100 bil ion from public and private sources, annuallyannual y, by 2020, to help developing countries mitigate and adapt to climate change. Brazil'’s environmental minister has asserted that Brazil

Brazil should receive at least 10% of those funds.5671 Brazil also insisted that carbon credits developed under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol should carry over into the Paris Agreement'’s new international carbon markets and that countries that host emissions-cutting projects should not have to report the transfers of those credits to other countries. Many other negotiators expressed concern that Brazil'’s proposals could allowal ow poorly validated credits from the Kyoto mechanisms to undermine the new Paris Agreement markets, as well wel as risk double-counting the credits both internationally

international y and toward the host countries'’ domestic mitigation goals. Those disagreements

reportedly impeded efforts to finalize rules for new carbon markets under the Paris Agreement.57

72

Even as the Brazilian government has calledcal ed for greater international financial support, it has deprioritized domestic efforts to combat climate change. During Bolsonaro's first year in office, his administration In 2019, the Bolsonaro Administration closed the climate change departments within the environment and foreign ministries and cut funding for the implementation of Brazil's National Plan on Climate Change by 95%.58 reduced spending on climate change initiatives by about 10% compared to 2018. Brazil’s 2020 federal budget authorizes 37% less funding for climate change initiatives than was expended in 2019.73 Moreover, the Bolsonaro Administration lost one of Brazil'’s primary sources of international

assistance when it unilaterallyunilateral y restructured the governance of the Amazon Fund—a mechanism launched in 2008 to attract funding for conservation and sustainable development efforts. In response, the governments of Norway and Germany, which have donated nearly $1.3 billionbil ion to the fund since 2009, suspended their contributions in August 2019.59 State74 Vice President Hamilton Mourão and state governments in the Legal Amazon have sought to negotiate directlyare negotiating with Norway and Germany

to restore the funding.

U.S.-Brazilian Relations

The United States and Brazil historicallyhistorical y have enjoyed robust political and economic relations, but the countries'’ divergent perceptions of their national interests have inhibited the development of a close partnership. Those perceptions have changed somewhat under President Bolsonaro. over the past year and a half.

Whereas the past several Brazilian administrations sought to maintain autonomy in foreign affairs, Bolsonaro has calledcal ed for close alignment with the United States. Within Latin America, for example, the Bolsonaro Administration has adopted a more confrontational approach toward

69 Observatório do Clima, “Estimativas de Emissões de Gases de Efeito Estufa do Brasil 1970-2018,” November 5, 2019.

70 “Brazil to Remain in Paris Agreement ‘for Now,’ Bolsonaro Says,” Valor International, January 22, 2019. 71 Luciana Amaral and Gustavo Uribe, “Ricardo Salles: Brasil Cobrará no Mínimo US$10 bi ao Ano dos Países Ricos,” UOL, November 29, 2019. 72 Simon Evans and Josh Gabbatiss, “COP25: Key Outcomes Agreed at the U.N. Climate T alks in Madrid,” Carbon Brief, December 15, 2019; and Jean Chemnick, “ U.N. T alks Limp to a Close with No D eal on Carbon T rading,” E&E News, December 16, 2019.

73 Senado Federal, “SIGA Brasil,” accessed in June 2020. 74 Amazon Fund, “Donations,” at http://www.amazonfund.gov.br/en/donations/.

Congressional Research Service

15

link to page 20 link to page 25 link to page 27 Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

for example, the Bolsonaro Administration has adopted a more confrontational approach toward Cuba and has closely coordinated with the Trump Administration on measures to address the crisis in Venezuela. The Trump Administration has welcomed Bolsonaro’s rapprochement, designating Brazil as a major non-NATO al y and concluding several smal -scale bilateral commercial agreements in 2019. The Trump Administration also has sought to support Brazil’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, providing the country with more than $12.5 mil ion of health and humanitarian assistance and—more controversial y—2 mil ion doses of

hydroxychloroquine.75

Bolsonaro’s realignment of Brazilian foreign policy has been contentious domestical y. Some

analysts argue thatcrisis in Venezuela. The Bolsonaro Administration also has expressed support for controversial U.S. actions outside the region, such as the killing of Iranian military commander Qaasem Soleimani.

Bolsonaro's realignment of Brazilian foreign policy has been controversial domestically, with some analysts arguing it has not resulted in many concrete benefits for Brazil.6076 They note, for example, that the Trump Administration maintained—has maintained, and threatened to impose—, trade barriers on key Brazilian exports despite recent bilateral agreements (see “Recent Trade Negotiations”). on key Brazilian exports, such as beef and steel, despite having signed several bilateral commercial agreements during Bolsonaro's official visit to the White House in March 2019 (see "Recent Trade Negotiations"). Likewise, U.S. officials reportedly have warned Brazil that the closer defense ties implied by President Trump's designation of Brazil as a major non-NATO allycloser bilateral defense ties could be in jeopardy if Brazil allows al ows Chinese telecommunications company Huawei to participate in Brazil's 5G cellularBrazil’s 5G cel ular network (see the "“Defense Cooperation"” section). Some Brazilian analysts

also argue that abandoning the country'’s commitment to autonomy in foreign affairs has weakened Brazil'’s international standing and caused tensions in its relations with other important partners, such as fellowfel ow members of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) group.6177 There does not appear to be public support for the Trump Administration'’s foreign policy within Brazil; in 2019, 60% of Brazilians expressed no confidence in President Trump to "“do the

right thing regarding world affairs."62

”78

In some cases, domestic opposition has prevented Bolsonaro from aligning Brazilian foreign policy more closely with the United States. For example, during his 2018 presidential campaign,

Bolsonaro indicated he would follow President Trump'’s lead in withdrawing from the Paris Agreement on climate change and taking a more confrontational approach toward Chinese trade and investment. He has backed away from those positions since taking office, reportedly due to concerns about losing access to foreign markets, particularly within the powerful agribusiness sector, which accounts for 21% of Brazil'’s GDP and is a major component of Bolsonaro's political base.63

’s

political base.79

Although some Members of the 116th116th Congress have urged the Trump Administration to seize on Bolsonaro's goodwill Bolsonaro’s goodwil to develop a strategic partnership with Brazil, others have expressed

reservations about the current Brazilian administration. They are concerned about Bolsonaro's ’s commitment to democracy, human rights, and the rule of law, as well wel as about changes to Brazil's ’s environmental policies that appear to have contributed to fires and deforestation in the Brazilian

Amazon (see "“U.S. Support for Amazon Conservation").

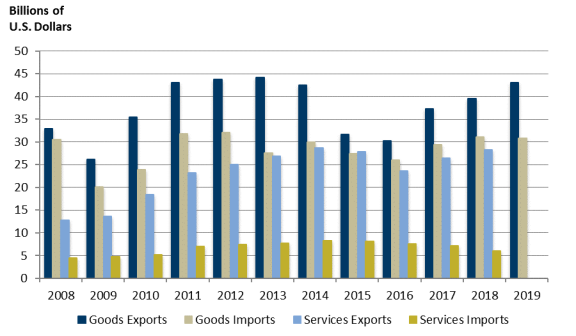

Commercial Relations

Trade policy often has been a contentious issue in U.S.-Brazilian relations. Since the early 1990s, Brazil'”).

75 U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Brazil, “Fact Sheet: U.S. Assistance to Brazil to Combat COVID-19,” May 31, 2020; and White House, “Joint Statement from the United States of America and the Federative Republic of Brazil Regarding Health Cooperation,” May 31, 2020. 76 T errence McCoy, “In Brazil, T rump T ariffs Show Bolsonaro’s ‘America First’ Foreign Policy Has Backfired,” Washington Post, December 2, 2019; and Oliver Stuenkel, “ Bolsonaro Placed a Losing Bet on T rump,” Foreign Policy, December 6, 2019. 77 Maria Herminia T avares, “Rumo a Lugar a Nenhum,” Folha de São Paulo, January 23, 2020; and “Alinhamento Automático do Brasil com EUA Causa Atritos na Cúpula dos BRICS,” Folha de São Paulo, November 13, 2019. 78 Richard Wike, “T rump Ratings Remain Low Around Globe, While Views of U.S. Stay Mostly Favorable,” Pew Research Center, January 8, 2020.