Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Changes from February 20, 2020 to February 24, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Contents

- Introduction

- Brazil's Political and Economic Environment

- Background

- Recession, Insecurity, and Corruption (2014-2018)

- Bolsonaro Administration (2019-Present)

- Amazon Conservation and Climate Change

- Brazilian Policies and Deforestation Trends

- Paris Agreement

- U.S.-Brazilian Relations

- Commercial Relations

- Recent Trade Negotiations

- Trade and Investment Flows

- Security Cooperation

- Counternarcotics

- Counterterrorism

- Defense Cooperation

- U.S. Support for Amazon Conservation

- Outlook

Summary

Occupying almost half of South America, Brazil is the fifth-largest and fifth-most-populous country in the world. Given its size and tremendous natural resources, Brazil has long had the potential to become a world power and periodically has been the focal point of U.S. policy in Latin America. Brazil's rise to prominence has been hindered, however, by uneven economic performance and political instability. After a period of strong economic growth and increased international influence during the first decade of the 21st century, Brazil has struggled with a series of domestic crises in recent years. Since 2014, the country has experienced a deep recession, record-high homicide rate, and massive corruption scandal. Those combined crises contributed to the controversial impeachment and removal from office of President Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016). They also discredited much of Brazil's political class, paving the way for right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro to win the presidency in October 2018.

|

Brazil at a Glance Population: 210.7 million (2019 est.) Race/Ethnicity: White—47.7%, Mixed Race—43.1%, Black—7.6%, Asian—1.1%, Indigenous—0.4% (Self-identification, 2010) Religion: Catholic—65%, Evangelical Christian—22%, None—8%, Other—4% (2010) Official Language: Portuguese Land Area: 3.3 million square miles (slightly smaller than the United States) Gross Domestic Product (GDP)/GDP per Capita: $1.85 trillion/$8,797 (2019 est.) Top Exports: oil, soybeans, iron ore, meat, and machinery (2019) Life Expectancy at Birth: 76 years (2018) Poverty Rate: 11.2% (2017) Leadership: President Jair Bolsonaro, Vice President Hamilton Mourão, Senate President Davi Alcolumbre, Chamber of Deputies President Rodrigo Maia Sources: Population, race/ethnicity, religion, land area, and life expectancy statistics from the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; GDP estimates from the International Monetary Fund; export data from Global Trade Atlas; and poverty data from Fundação Getúlio Vargas. |

Since taking office in January 2019, President Bolsonaro has maintained the support of his political base by taking socially conservative stands on cultural issues and proposing hard-line security policies intended to reduce crime and violence. He also has begun implementing economic and regulatory reforms favored by international investors and Brazilian businesses. Bolsonaro's confrontational approach to governance has alienated many potential congressional allies, however, slowing the enactment of his policy agenda. Brazilian civil society groups also have pushed back against Bolsonaro and raised concerns about environmental destruction and the erosion of democratic institutions, human rights, and the rule of law in Brazil.

In international affairs, the Bolsonaro Administration has moved away from Brazil's traditional commitment to autonomy and toward alignment with the United States. Bolsonaro has coordinated closely with the Trump Administration on challenges such as the crisis in Venezuela. On other matters, such as commercial ties with China, Bolsonaro has adopted a pragmatic approach intended to ensure continued access to Brazil's major export markets. The Trump Administration has welcomed Bolsonaro's rapprochement and sought to strengthen U.S.-Brazilian relations. In 2019, the Trump Administration took steps to bolster bilateral cooperation on counternarcotics and counterterrorism efforts and designated Brazil as a major non-NATO ally. The United States and Brazil also agreed to several measures intended to facilitate trade and investment. Nevertheless, some Brazilians have questioned the benefits of partnership with the United States, as the Trump Administration has maintained certain import restrictions and threatened to impose tariffs on other key Brazilian products.

The 116th Congress has expressed renewed interest in Brazil and U.S.-Brazilian relations. Environmental conservation has been a major focus, with Congress appropriating $15 million for foreign assistance programs in the Brazilian Amazon, including $5 million to address fires in the region, in the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94). Likewise, Members introduced legislative proposals that would express support for Amazon conservation efforts (S.Res. 337) and restrict U.S. defense and trade relations with Brazil in response to deforestation (H.R. 4263). Congress also has expressed concerns about the state of democracy and human rights in Brazil. A provision of the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2020 (P.L. 116-92) directs the Secretary of Defense, in coordination with the Secretary of State, to submit a report to Congress regarding Brazil's human rights climate and U.S.-Brazilian security cooperation. Another resolution (H.Res. 594) would express concerns about threats to human rights, the rule of law, democracy, and the environment in Brazil.

Introduction

As the fifth-largest country and the ninth-largest economy in the world, Brazil plays an important role in global governance (see Figure 1 for a map of Brazil). Over the past 20 years, Brazil has forged coalitions with other large, developing countries to push for changes to multilateral institutions and to ensure that global agreements on issues ranging from trade to climate change adequately protect their interests. Brazil also has taken on a greater role in promoting peace and stability, contributing to U.N. peacekeepingpeacekeeping missions and mediating conflicts in South America and further afield. Although recent domestic challenges have led Brazil to turn inward and weakened its appeal globally, the country continues to exert considerable influence on international policy issues that affect the United States.

U.S. policymakers have often viewed Brazil as a natural partner in regional and global affairs, given its status as a fellow multicultural democracy. Repeated efforts to forge a close partnership have left both countries frustrated, however, as their occasionally divergent interests and policy approaches have inhibited cooperation. The Trump Administration has viewed the 2018 election of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro as a fresh opportunity to deepen the bilateral relationship. Bolsonaro has begun to shift Brazil's foreign policy to bring the country into closer alignment with the United States, and President Trump has designated Brazil a major non-NATO ally. Nevertheless, ongoing differences over trade protections and relations with China threaten to leave both the United States and Brazil with unmet expectations once again.

The 116th Congress has expressed renewed interest in Brazil, recognizing Brazil's potential to affect U.S. initiatives and interests. Some Members view Brazil as a strategic partner for addressing regional and global challenges. They have urged the Trump Administration to forge stronger economic, security, and military ties with Brazil to bolster the bilateral relationship and counter the influence of extra-hemispheric powers, such as China and Russia.1 Other Members have expressed reservations about a close partnership with the Bolsonaro Administration. They are concerned that Bolsonaro is presiding over an erosion of democracy and human rights in Brazil and that his environmental policies threaten the Amazon and global efforts to mitigate climate change.2 Congress may continue to assess these differing approaches to U.S.-Brazilian relations as it carries out its oversight responsibilities and considers FY2021 appropriations and other legislative initiatives.

|

|

Source: Map Resources. Adapted by CRS Graphics. |

Brazil's Political and Economic Environment

Background

Brazil declared independence from Portugal in 1822, initially establishing a constitutional monarchy and retaining a slave-based, plantation economy. Although the country abolished slavery in 1888 and became a republic in 1889, economic and political power remained concentrated in the hands of large rural landowners and the vast majority of Brazilians remained outside the political system. The authoritarian government of Getúlio Vargas (1930-1945) began the incorporation of the working classes but exerted strict control over labor as part of its broader push to centralize power in the federal government. Vargas also began to implement a state-led development model, which endured for much of the 20th century as successive governments supported the expansion of Brazilian industry.

Brazil experienced two decades of multiparty democracy from 1945 to 1964 but struggled with political and economic instability, which ultimately led the military to seize power. A 1964 military coup, encouraged and welcomed by the United States, ushered in two decades of authoritarian rule.3 Although repressive, the military government was not as brutal as the dictatorships established in several other South American nations. It nominally allowed the judiciary and congress to function during its tenure but stifled representative democracy and civic action, carefully preserving its influence during one of the most protracted transitions to democracy to occur in Latin America. Brazilian security forces killed more than 8,000 indigenous people and at least 434 political dissidents during the dictatorship, and they detained and tortured an estimated 30,000-50,000 others.4

Brazil restored civilian rule in 1985, and a national constituent assembly, elected in 1986, promulgated a new constitution in 1988. The constitution established a liberal democracy with a strong president, a bicameral congress consisting of the 513-member chamber of deputies and the 81-member senate, and an independent judiciary. Power is somewhat decentralized under the country's federal structure, which includes 26 states, a federal district, and some 5,570 municipalities.

Brazil experienced economic recession and political uncertainty during the first decade after its political transition. Numerous efforts to control runaway inflation failed, and two elected presidents did not complete their terms; one died before taking office, and the other was impeached on corruption charges and resigned.

The situation began to stabilize, however, under President Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995-2002) of the center-right Brazilian Social Democracy Party (Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira, or PSDB). Initially elected on the success of the anti-inflation Real Plan that he implemented as finance minister under President Itamar Franco (1992-1994), Cardoso ushered in a series of market-oriented economic reforms. His administration privatized some state-owned enterprises, gradually opened the economy to foreign trade and investment, and adopted the three main pillars of Brazil's macroeconomic policy: a floating exchange rate, a primary budget surplus, and an inflation-targeting monetary policy. Nevertheless, the Brazilian state maintained an influential role in the economy.

The Cardoso Administration's economic reforms and a surge in international demand (particularly from China) for Brazilian commodities—such as oil, iron, and soybeans—fostered a period of strong economic growth in Brazil during the first decade of the 21st century. The center-left Workers' Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, or PT) administration of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula, 2003-2010) used increased export revenues to improve social inclusion and reduce inequality. Among other measures, the PT-led government expanded social welfare programs and raised the minimum wage by 64% above inflation.5 Between 2003 and 2010, the Brazilian economy expanded by an average of 4.1% per year and the poverty rate fell from 28.2% to 13.6%.6 The growth of the middle class fueled a domestic consumption boom that reinforced Brazil's economic expansion. Although the poverty rate initially continued to decline under the PT-led administration of President Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016)—reaching a low of 8.4% in 2014—socioeconomic conditions deteriorated during Rousseff's final two years in office.7

Recession, Insecurity, and Corruption (2014-2018)

After nearly two decades of relative stability, Brazil has struggled with a series of crises since 2014. The country fell into a deep recession in late 2014, due to a decline in global commodity prices and the Rousseff Administration's economic mismanagement.8 Brazil's real gross domestic product (GDP) contracted by 8.2% over the course of 2015 and 2016.9 Although Brazil emerged from recession in mid-2017, recovery has been slow. The economy expanded by just over 1% in 2017 and 2018, and unemployment, which peaked at 13.7% in the first quarter of 2017, has remained above 10% for nearly four years.10 Largely due to the weak labor market, the real incomes of the bottom half of Brazilian workers have declined by 17% since the onset of the recession, pushing more than 6 million people into poverty.11 The downturn has disproportionately affected Afro-Brazilians, who comprise about half of the Brazilian population but 64% of the unemployed.12 Large fiscal deficits at all levels of government have exacerbated the situation, limiting the resources available to provide social services.

The deep recession also has hindered federal, state, and local government efforts to address serious challenges such as crime and violence. A record-high 64,000 Brazilians were killed in 2017, and the country's homicide rate of 30.9 per 100,000 residents was more than five times the global average. Although homicides declined by nearly 11% in 2018, feminicide (gender-motivated murders of women) and reports of sexual violence increased.13 The deterioration in the security situation, like the economic crisis, has disproportionately affected Afro-Brazilians, who account for more than 75% of homicide victims, 75% of those killed by police, and 61% of feminicide victims.14

A series of corruption scandals have further discredited the country's political establishment. The so-called Car Wash (Lava Jato) investigation, launched in 2014, has implicated politicians from across the political spectrum and many prominent business executives. The initial investigation revealed that political appointees at the state-controlled oil company, Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. (Petrobras), colluded with construction firms to fix contract bidding processes. The firms then provided kickbacks to Petrobras officials and politicians in the ruling coalition. Parallel investigations have discovered similar practices throughout the public sector, with businesses providing bribes and illegal campaign donations in exchange for contracts or other favorable government treatment. The scandals sapped President Rousseff's political support, contributing to her controversial impeachment and removal from office in August 2016.15 Michael Temer, who presided over a center-right government for the remainder of Rousseff's term (2016-2018), was entangled in several corruption scandals but managed to hold on to power. Several other high-level politicians, including former President Lula, have been convicted and face potentially lengthy prison sentences (see the text box, below).

The inability of Brazil's political leadership to overcome these crises has undermined Brazilians' confidence in their democratic institutions. As of mid-2018, 33% of Brazilians expressed trust in the judiciary, 26% expressed trust in the election system, 12% expressed trust in congress, 7% expressed trust in the federal government, and 6% expressed trust in political parties. Moreover, only 9% of Brazilians expressed satisfaction with the way democracy was working in their country—the lowest percentage in all of Latin America.16

|

Lula's Imprisonment and Release Brazilian prosecutors have brought charges against former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula; 2003-2010) in at least eight corruption cases, including two cases for which he has already been convicted. The first conviction was upheld by a circuit court panel and Brazil's Superior Court of Justice, which resulted in Lula being imprisoned and barred from running for a third presidential term in 2018. Press reports have raised concerns, however, that Judge Sérgio Moro and the prosecutors initially involved in Lula's case may have been politically biased and engaged in improper coordination; Moro now serves as President Jair Bolsonaro's minister of justice. Lula was released from prison in November 2019 after Brazil's supreme court ruled that most individuals convicted of nonviolent crimes should remain free until they have exhausted the appeals process. Nevertheless, Lula remains ineligible for elective office unless the convictions are overturned and ultimately may have to serve out the remainder of his sentences. Sources: Letter from Adriano Augusto Silvestrin Guedes, Brazilian Circuit Court Federal Prosecutor, et al. to a Group of International Jurists, published by the Global Anticorruption Blog, September 12, 2019; Glenn Greenwald and Victor Pougy, "Hidden Plot: Brazil's Top Prosecutors Who Indicted Lula Schemed in Secret Messages to Prevent His Party from Winning 2018 Election," Intercept, June 9, 2019; and Ernesto Londoño and Letícia Casado, "Ex-President of Brazil Is Freed from Prison After Ruling by Supreme Court," New York Times, November 9, 2019. |

Bolsonaro Administration (2019-Present)

Brazilian voters registered their intense dissatisfaction with the situation in the country in the 2018 elections. In addition to ousting 75% of incumbents running for reelection to the senate and 43% of incumbents running for reelection to the chamber of deputies, they elected as president, Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right congressman and retired army captain.17 Prior to the election, most observers considered Bolsonaro to be a fringe figure in the Brazilian congress. He exercised little influence over policy and was best known for his controversial remarks defending the country's military dictatorship (1964-1985) and expressing prejudice toward marginalized sectors of Brazilian society.18 Backed by the small Social Liberal Party (PSL), Bolsonaro also lacked the finances and party machinery of his principal competitors. Nevertheless, his social media-driven campaign and populist, law-and-order message attracted a strong base of support. He outflanked his opponents by exploiting anti-PT and antiestablishment sentiment and aligning himself with the few institutions that Brazilians still generally trust: the military and the churches.19 Bolsonaro largely remained off the campaign trail in the weeks leading up to the election after being stabbed in an assassination attempt, but he easily defeated the PT's Fernando Haddad 55%-45% in a second-round runoff. Bolsonaro's PSL also won the second-most seats in the lower house.

Since Bolsonaro began his four-year term on January 1, 2019, he has struggled to advance portions of his agenda due to cabinet infighting and the lack of a working majority in Brazil's fragmented congress, which includes 24 political parties.20 Whereas previous Brazilian presidents stitched together governing coalitions by distributing control of government jobs and resources to parties in exchange for their support, Bolsonaro has refused to enter into such arrangements. Moreover, he generally has avoided negotiating the details of his proposed policies with legislators. Instead, Bolsonaro has sought to keep his political base mobilized by frequently taking socially conservative stands on cultural issues and verbally attacking perceived enemies, such as the press, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and other branches of government.21 Bolsonaro's confrontational approach to governance has alienated many of his potential allies within the conservative-leaning congress. In November 2019, for example, Bolsonaro abandoned the PSL after a series of disagreements with the party's leadership; he intends to create a new Alliance for Brazil party to contest future elections.

During its first year in office, the Bolsonaro Administration began implementing key aspects of its market-oriented economiceconomic agenda. As part of a far-reaching privatization program, the Brazilian government began selling off assets, including subsidiaries of state-owned enterprises, stakes in private companies, and infrastructure and energy concessions, yielding revenues of approximately $66 billion in 2019.22 The Brazilian congress also enacted a major pension reform expected to reduce government expenditures by at least $194 billion over the next decade.23 Those policies build on a 2016 constitutional amendment that froze inflation-adjusted government spending for 20 years. Although the Bolsonaro Administration has proposed additional measures to simplify the tax system, cut and decentralize government expenditures, and decrease compensation and job security for government employees, political parties may be reluctant to enact austerity measures in the lead-up to Brazil's October 2020 municipal elections. The International Monetary Fund estimates that the Brazilian economy expanded by 1.2% in 2019 and will expand by 2.2% in 2020, due to improved business sentiment following recent market-oriented policy changes.24 About 11% of Brazilians remain unemployed,25 however, and some economists argue that rather than reducing the size of the state, Brazil should reorient expenditures to programs that protect the most vulnerable and to productivity-enhancing investments, such as education, training, and infrastructure.26

Bolsonaro has had difficulty advancing the hard-line security platform that was the centerpiece of his campaign. The Brazilian congress has blocked Bolsonaro's proposal to shield from prosecution police who kill suspected criminals and has pushed back against Bolsonaro's decrees loosening gun controls. Other Bolsonaro Administration proposals, including measures to modernize police investigations and impose stricter criminal sentences, were enacted in December 2019. Preliminary data suggest that security conditions in Brazil improved in 2019, but the number of individuals killed by police in states such as Rio de Janeiro increased significantly.27 The Bolsonaro Administration has claimed credit for falling crime rates, but some security analysts argue the situation has been improving since late 2017 due to state and municipal initiatives and reduced conflict between the country's largest criminal groups.28 (See the "Counternarcotics" section for more information.)

Anti-corruption efforts in Brazil have experienced a series of recent setbacks. Although President Bolsonaro campaigned on an anti-corruption platform, he has repeatedly interfered in law enforcement agencies, potentially hindering investigations and calling into question the political independence of Brazilian institutions. In August 2019, he dismissed the head of the Brazilian federal police office in Rio de Janeiro, which is investigating potential corruption and money laundering by Bolsonaro's son, Flávio. In September 2019, Bolsonaro disregarded a norm in place since 2003 of selecting an attorney general from a shortlist approved by the public prosecutors' association. Observers also have questioned changes Bolsonaro has made to Brazil's tax collection agency, financial intelligence unit, and antitrust regulator. At the same time, the Brazilian congress has been reluctant to adopt anti-corruption reforms and the supreme court has issued a series of rulings that could jeopardize convictions obtained in the Car Wash investigation and make it more difficult to investigate and prosecute corruption cases.29

Many analysts argue there has been an erosion of democracy in Brazil under Bolsonaro.30 During his first year in office, the president continued to celebrate Brazil's military dictatorship and those installed in other South American countries, and his sons and members of his administration occasionally suggested they could impose authoritarian measures under certain circumstances. Bolsonaro also took steps to weaken the press, exert control over civil society, and roll back rights previously granted to marginalized groups.31 Civil-military relations have shifted as Bolsonaro has appointed retired and active-duty officers to lead more than a third of his cabinet ministries and to dozens of other positions throughout the government. The Brazilian military is now more involved in politics than it has been at any time since the end of the dictatorship. Some analysts maintain, however, that the military has had a moderating influence on the government.32 Brazil's civil society, congress, and judiciary also have served as checks on Bolsonaro. Nevertheless, human rights advocates argue the president's statements and actions have fueled attacks against journalists and activists.33

Polls conducted at the conclusion of his first year in office suggest Brazilian public opinion toward Bolsonaro remains divided. About 32% of Brazilians consider Bolsonaro's government "good" or "great," 32% consider it "average," and 35% consider it "bad" or "terrible."34

Amazon Conservation and Climate Change

A 30% increase in fires in the Brazilian Amazon in 2019 compared to the previous year led many Brazilians and international observers to express concern about the rainforest and the extent to which its destruction is contributing to regional and global climate change.35 Covering nearly 2.7 million square miles across seven countries, the Amazon Basin is home to the largest and most biodiverse tropical forest in the world.36 Scientific studies have found that the Amazon plays an important role in the global carbon cycle by absorbing and sequestering carbon. Although findings vary, one recent study estimated the forest absorbs 560 million tons of carbon dioxide per year and its biomass holds 76 billion tons of carbon—an amount equivalent to seven years of global carbon emissions.37 The Amazon also pumps water into the atmosphere, affecting regional rainfall patterns throughout South America.38 An estimated 17% of the Amazon basin has been deforested, however, and some scientists have warned that the forest may be nearing a tipping point at which it is no longer able to sustain itself and transitions to a drier, savanna-like ecosystem.39

Efforts to conserve the forest often focus on Brazil, since the country encompasses about 69% of the Amazon Basin.40 Within Brazil, the government has established an administrative zone known as the Legal Amazon, which includes nine states: Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Maranhão, Mato Grosso, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima, and Tocantins (see Figure 1). Although rainforest covers most of the Legal Amazon, savanna (Cerrado) and wetlands (Pantanal) are present in portions of the region. The Legal Amazon was largely undeveloped until the 1960s, when the military-led government began subsidizing the settlement and development of the region as a matter of national security. Partially due to those incentives, the human population in the Legal Amazon grew from 6 million in 1960 to 25 million in 2010. Forest cover in the Legal Amazon has declined by approximately 20% as settlements, roads, logging, ranching, farming, and other activities have proliferated in the region.41

Brazilian Policies and Deforestation Trends

In 2004, the Brazilian government adopted an action plan to prevent and control deforestation in the Legal Amazon.42 It increased surveillance in the Amazon region, began to enforce environmental laws and regulations more rigorously, and took steps to consolidate and expand protected lands. Nearly 20% of the Brazilian Amazon now has some sort of federal or state protected status, and the Brazilian government has recognized an additional 22% of the Brazilian Amazon as indigenous territories.43 Brazil's forest code also requires private landowners in the Legal Amazon to maintain native vegetation on 80% of their properties.

Other Brazilian initiatives have sought to support sustainable development in the Amazon while limiting the extent to which the country's agricultural sector drives deforestation. In 2008, the Brazilian government began conditioning credit on farmers' compliance with environmental laws; in 2009, the government banned new sugarcane plantations in the Legal Amazon. The Brazilian government also supported private sector conservation initiatives. Those included a 2006 voluntary agreement among most major soybean traders not to purchase soybeans grown on lands deforested after 2006 (later revised to 2008) and a 2009 voluntary agreement among meatpackers not to purchase cattle raised on lands deforested in the Amazon after 2008.

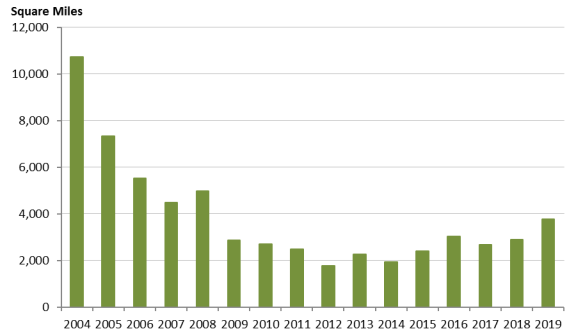

Brazil's public and private conservation efforts, combined with economic factors that made agricultural commodity exports less profitable,44 led to an 83% decline in deforestation in the Legal Amazon between 2004 and 2012. Deforestation has been trending upward in recent years, however, rising from a low of 1,765 square miles in 2012 to 3,769 square miles in the 12-month monitoring period that ended in July 2019 (see Figure 2). Analysts have linked the increase in deforestation to a series of policy reversals that have cut funding for environmental enforcement, reduced the size of protected areas, and relaxed conservation requirements.45 Market incentives, such as the growth in Chinese imports of Brazilian beef and soybeans, also have contributed to recent deforestation trends.46 For example, China purchased nearly 76% of its soybean imports from Brazil in 2018, up from roughly 50% in prior years, after imposing a retaliatory tariff on U.S. soybeans.47

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from the Brazilian government's Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, "Taxa PRODES Amazônia – 2004-2019," November 18, 2019. Notes: Annual monitoring periods run from August to July (e.g., 2019 data include deforestation from August 2018 to July 2019). |

Although changes that weakened Brazil's environmental policies began under President Rousseff and continued under President Temer, some analysts argue that the Bolsonaro Administration's approach to the Amazon has led to further increases in deforestation.48 Bolsonaro has fiercely defended Brazil's sovereignty over the Legal Amazon and its right to develop the region. Since taking office, his administration has lifted the ban on new sugarcane plantations in the Legal Amazon and called for an end to the soy moratorium. It also has proposed measures to allow commercial agriculture, mining, and hydroelectric projects in indigenous territories, arguing that such economic activities will benefit those living in the region and reduce incentives for illegal deforestation. At the same time, Bolsonaro has questioned the Brazilian government's deforestation data and repeatedly criticized the agencies responsible for enforcing environmental laws.

Those statements and actions reportedly have emboldened some loggers, miners, and ranchers, contributing to the surge in fires in 2019 and a 30% increase in deforestation in the annual monitoring period that included the first seven months of Bolsonaro's term.49 Bolsonaro initially dismissed environmental concerns about the Amazon, asserting that deforestation and burning are cultural practices that will never end.50 In January 2020, however, he announced the creation of a new security force to protect the environment and a new Amazon Council, headed by Vice President Hamilton MouraoMourão, to coordinate conservation and sustainable development efforts. As of the close of 2019, a majority (54%) of Brazilians disapproved of Bolsonaro's environmental policies.51

Paris Agreement

The rising levels of Amazon deforestation call into question whether Brazil will meet its Paris Agreement commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 37% below 2005 levels (to 1.3 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO₂e) by 2025.52 According to a 2018 assessment by the U.N. Environment Program, Brazil's greenhouse gas emissions declined by 12% per year from 2006 to 2016, as significant declines in deforestation offset slight increases in emissions from other sources.53 Those reductions had put Brazil on track to meet its Paris Agreement commitment, but emissions have begun to rise again due to increased deforestation. In 2018, Brazil's greenhouse gas emissions increased by an estimated 0.3% (to 1.9 GtCO₂e), even as emissions from the energy sector declined by nearly 5%.54

President Bolsonaro had pledged to withdraw from the Paris Agreement during his 2018 election campaign, but he reversed course following his inauguration, stating that Brazil would remain in the agreement "for now."55 At the 25th Conference of Parties to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 25), Brazil pushed developed countries to meet their 2009 goal to mobilize $100 billion from public and private sources, annually, by 2020, to help developing countries mitigate and adapt to climate change. Brazil's environmental minister has asserted that Brazil should receive at least 10% of those funds.56 Brazil also insisted that carbon credits developed under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol should carry over into the Paris Agreement's new international carbon markets and that countries that host emissions-cutting projects should not have to report the transfers of those credits to other countries. Many other negotiators expressed concern that Brazil's proposals could allow poorly validated credits from the Kyoto mechanisms to undermine the new Paris Agreement markets, as well as risk double-counting the credits both internationally and toward the host countries' domestic mitigation goals. Those disagreements reportedly impeded efforts to finalize rules for new carbon markets under the Paris Agreement.57

Even as the Brazilian government has called for greater international financial support, it has deprioritized domestic efforts to combat climate change. During Bolsonaro's first year in office, his administration closed the climate change departments within the environment and foreign ministries and cut funding for the implementation of Brazil's National Plan on Climate Change by 95%.58 Moreover, the Bolsonaro Administration lost one of Brazil's primary sources of international assistance when it unilaterally restructured the governance of the Amazon Fund—a mechanism launched in 2008 to attract funding for conservation and sustainable development efforts. In response, the governments of Norway and Germany, which have donated nearly $1.3 billion to the fund since 2009, suspended their contributions in August 2019.59 State governments in the Legal Amazon have sought to negotiate directly with Norway and Germany to restore the funding.

U.S.-Brazilian Relations

The United States and Brazil historically have enjoyed robust political and economic relations, but the countries' divergent perceptions of their national interests have inhibited the development of a close partnership. Those perceptions have changed somewhat under President Bolsonaro. Whereas the past several Brazilian administrations sought to maintain autonomy in foreign affairs, Bolsonaro has called for close alignment with the United States. Within Latin America, for example, the Bolsonaro Administration has adopted a more confrontational approach toward Cuba and has closely coordinated with the Trump Administration on measures to address the crisis in Venezuela. The Bolsonaro Administration also has expressed support for controversial U.S. actions outside the region, such as the killing of Iranian military commander Qaasem Soleimani.

Bolsonaro's realignment of Brazilian foreign policy has been controversial domestically, with some analysts arguing it has not resulted in many concrete benefits for Brazil.60 They note, for example, that the Trump Administration has maintained—and threatened to impose—trade barriers on key Brazilian exports, such as beef and steel, despite having signed several bilateral commercial agreements during Bolsonaro's official visit to the White House in March 2019 (see "Recent Trade Negotiations"). Likewise, U.S. officials reportedly have warned Brazil that the closer defense ties implied by President Trump's designation of Brazil as a major non-NATO ally could be in jeopardy if Brazil allows Chinese telecommunications company Huawei to participate in Brazil's 5G cellular network (see the "Defense Cooperation" section). Some Brazilian analysts also argue that abandoning the country's commitment to autonomy in foreign affairs has weakened Brazil's international standing and caused tensions in its relations with other important partners, such as fellow members of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) group.61 There does not appear to be public support for the Trump Administration's foreign policy within Brazil; in 2019, 60% of Brazilians expressed no confidence in President Trump to "do the right thing regarding world affairs."62

In some cases, domestic opposition has prevented Bolsonaro from aligning Brazilian foreign policy more closely with the United States. For example, during his 2018 presidential campaign, Bolsonaro indicated he would follow President Trump's lead in withdrawing from the Paris Agreement on climate change and taking a more confrontational approach toward Chinese trade and investment. He has backed away from those positions since taking office, reportedly due to concerns about losing access to foreign markets, particularly within the powerful agribusiness sector, which accounts for 21% of Brazil's GDP and is a major component of Bolsonaro's political base.63

Although some Members of the 116th Congress have urged the Trump Administration to seize on Bolsonaro's goodwill to develop a strategic partnership with Brazil, others have expressed reservations about the current Brazilian administration. They are concerned about Bolsonaro's commitment to democracy, human rights, and the rule of law, as well as about changes to Brazil's environmental policies that appear to have contributed to fires and deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon (see "U.S. Support for Amazon Conservation").

Commercial Relations

Trade policy often has been a contentious issue in U.S.-Brazilian relations. Since the early 1990s, Brazil's trade policy has prioritized integration with its South American neighbors through the Southern Common Market (Mercosur) and multilateral negotiations at the World Trade Organization (WTO).64 Brazil is the industrial hub of Mercosur, which it established in 1991 with Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Although the bloc was intended to advance incrementally toward full economic integration, only a limited customs union has been achieved thus far. Mercosur also has evolved into a somewhat protectionist arrangement, shielding its members from external competition rather than serving as a platform for insertion into the global economy, as originally envisioned. Within the WTO, Brazil traditionally has joined with other developing nations to push the United States and other developed countries to reduce their agricultural tariffs and subsidies while resisting developed countries' calls for increased access to developing countries' industrial and services sectors. Those differences blocked conclusion of the most recent round of multilateral trade negotiations (the WTO's Doha Round), as well as U.S. efforts in the 1990s and 2000s to establish a hemisphere-wide Free Trade Area of the Americas.65

Recent Trade Negotiations

The Bolsonaro and Trump Administrations have negotiated several agreements intended to strengthen the bilateral commercial relationship. During Bolsonaro's March 2019 official visit to Washington, the United States and Brazil agreed to take steps toward lowering trade barriers for certain agricultural products. Brazil agreed to implementadopt a tariff rate quota that would allow the import—implemented in November 2019—to allow the importation of 750,000 tons of U.S. wheat annually without tariffs and. Brazil also agreed to adopt "science-based conditions" that could enable imports of U.S. pork. In exchange, the United States agreed to send a U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) team to Brazil to audit the country's raw beef inspection system.66

The United States had suspended imports of raw beef from Brazil in June 2017, after Brazilian investigators discovered that some of the country's top meat processing companies, including JBS and BRF, had bribed food inspectors to approve the sale of tainted products. FSIS began inspecting all meat products arriving from Brazil and refused entry to 11% of Brazilian fresh beef products in the months leading up to the suspension.67 The Bolsonaro Administration had hoped an FSIS The Bolsonaro Administration had hoped the audit would quickly reopen the U.S. market to Brazilian beef and has expressed frustration that U.S. import restrictions remain in place.67 The United States has not allowed fresh beef imports from Brazil since 2017, when Brazilian investigators discovered that some of the country's top meat processing companies, including JBS and BRF, had bribed food inspectors to approve the sale of tainted products.68remained in place through the end of 2019.68 On February 21, 2020, however, the Trump Administration reportedly lifted the suspension after determining that "Brazil's food safety inspection system governing raw intact beef is equivalent to that of the [United States]."69 Some consumer advocates, industry groups, and Members of Congress remained concerned about Brazilian meat. A bill introduced in April 2019 (S. 1124, Tester) would suspend all beef and poultry imports from Brazil while a working group evaluates the extent to which those imports pose a threat to food safety.

The United States and Brazil announced several other agreements during Bolsonaro's March 2019 official visit. A technology safeguards agreement, which the Brazilian congress ratified in November 2019, will enable the launch of U.S.-licensed satellites from Alcântara space center in Brazil's northeastern state of Maranhão. The United States also endorsed Brazil's accession to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in exchange for Brazil agreeing to gradually give up its "special and differential treatment" status, which grants special rights to developing nations at the WTO.

Building on those measures, U.S. and Brazilian officials reportedly have begun discussing a more comprehensive trade agreement.6970 Barring changes to Mercosur's rules, any agreement to reduce tariffs would need to be negotiated with the broader bloc. In 2019, Mercosur signed free trade agreements with the European Union and the European Free Trade Association. Those agreements have yet to be ratified, however, and the recent political shift in Argentina could make the negotiation of new agreements more difficult.7071

It is not clear that the Bolsonaro and Trump Administrations would be willing to expose their domestic producers to increased foreign competition. Industry associations in Brazil reportedly have been lobbying the Bolsonaro Administration to focus on reducing costs for domestic business before pursuing trade liberalization.7172 U.S. businesses also have sought protections, and President Trump has occasionally threatened to impose tariffs on Brazilian products (see the text box, below).

|

Potential U.S. Tariffs on Brazilian Steel In December 2019, President Trump announced his intention to impose tariffs on steel imports from Brazil. The Trump Administration had imposed a 25% tariff on selected steel imports from most countries in March 2018, using the authority granted in Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 to take action to adjust imports that threaten to impair U.S. national security (19 U.S.C. §1862). The Administration ended up excluding Brazil from those additional duties after the Brazilian government agreed to a quota allotment that restricts the total amount of steel Brazil can export to the United States. In his December 2019 statement, President Trump appeared to argue that the steel tariffs were a response to Brazil devaluing its currency, which boosted the competitiveness of Brazil's agricultural exports and hurt U.S. farmers. Economists maintain that the Brazilian real has lost value compared to the U.S. dollar due to the comparative weakness of the Brazilian economy, not manipulation by Brazil's central bank. The Trump Administration's trade dispute with China also has led to increased Chinese purchases of Brazilian soy and other agricultural commodities. The Trump Administration has yet to impose tariffs on Brazilian steel, and President Bolsonaro asserts that President Trump reversed his decision after they discussed the issue. For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10667, Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, by Rachel F. Fefer and Vivian C. Jones. Sources: White House, "Presidential Proclamation in Adjusting Imports of Steel into the United States," March 8, 2018; White House, "Presidential Proclamation in Adjusting Imports of Steel into the United States," May 31, 2018; Ana Swanson, "Trump Says U.S. Will Impose Metal Tariffs on Brazil and Argentina," New York Times, December 2, 2019; and "Brazil: Bolsonaro Says Trump Backtracked on Tariffs," Latin News Daily, December 23, 2019. |

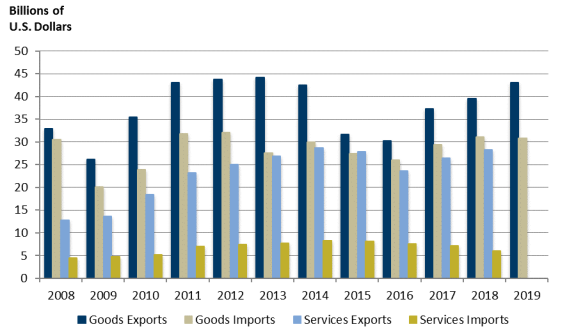

Trade and Investment Flows

U.S.-Brazilian trade has increased significantly over the past two decades but has suffered from economic volatility, such as the 2007-2008 global financial crisis and Brazil's 2014-2017 recession (see Figure 3). In 2019, total bilateral merchandise trade amounted to $73.9 billion. U.S. goods exports to Brazil totaled $43.1 billion, and U.S. goods imports from Brazil totaled $30.9 billion, giving the United States a $12.2 billion trade surplus. The top U.S. exports to Brazil were mineral fuels, aircraft, machinery, and organic chemicals. The top U.S. imports from Brazil included mineral fuels, iron and steel, aircraft, machinery, and wood and wood pulp. In 2019, Brazil was the 14th-largest trading partner of the United States.7273 The United States was Brazil's second-largest trading partner, accounting for 14.8% of Brazil's total merchandise trade, compared to 24.4% for China.73

Brazil benefits from the Generalized System of Preferences program, which provides nonreciprocal, duty-free tariff treatment to certain products imported from designated developing countries. Brazil was the fourth-largest beneficiary of the program in 2019, with duty-free imports to the United States valued at $2.3 billion—equivalent to 7.4% of all U.S. merchandise imports from Brazil.74

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of U.S. Department of Commerce data, as made available through Global Trade Atlas and the Bureau of Economic Analysis, accessed February 2020. Note: Services data are not yet available for 2019. |

U.S.-Brazilian services trade is also significant. In 2018 (the most recent year for which data are available), total bilateral services trade amounted to $34.4 billion. U.S. services exports to Brazil totaled $28.2 billion, and U.S. services imports from Brazil totaled $6.1 billion, giving the United States a $22.1 billion surplus. Travel, transport, and telecommunications were the top categories of U.S. services exports to Brazil, and business services was the top category of U.S. imports from Brazil.7576 In 2018, more than 2.2 million Brazilians visited the United States, spending $11.5 billion on travel and tourism.7677 Brazil began exempting U.S. citizens from the country's tourist and business visa requirements in June 2019, which could increase U.S. travel to Brazil in the coming years.

U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) in Brazil has increased by more than 60% since 2008. As of 2018 (the most recent year for which data are available), the accumulated stock of U.S. FDI in Brazil was $70.9 billion, with significant investments in manufacturing, finance, and mining, among other sectors.77

Security Cooperation

Although U.S.-Brazilian cooperation on security issues traditionally has been limited, law enforcement and military ties have grown closer in recent years. In 2018, the countries launched a new Permanent Forum on Security that aims to foster "strategic, intense, on-going bilateral cooperation" on a range of security challenges, including arms and drug trafficking, cybercrime, financial crimes, and terrorism.7879 The United States and Brazil also engage in high-level security discussions under the long-standing Political-Military Dialogue and a new Strategic Partnership Dialogue, which met for the first time in September 2019.

Counternarcotics

Brazil is not a major drug-producing country, but it is the world's second-largest consumer of cocaine hydrochloride and likely the world's largest consumer of cocaine base. It is also a major transit country for cocaine bound for Europe.7980 Organized crime in Brazil has increased in scope and scale over the past decade, as some of the country's large, well-organized, and heavily armed criminal groups—such as the Red Command (Comando Vermelho, or CV) and the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital, or PCC)—have increased their transnational operations. Security analysts have attributed much of the recent violence in Brazil, particularly in the northern portion of the country, to clashes among the CV, PCC, and their local affiliates over control of strategic trafficking corridors.80

The Brazilian government has responded to the challenges posed by organized crime by bolstering security along the 9,767-mile border it shares with 10 nations, including the region's cocaine producers—Bolivia, Colombia, and Peru. Under its Strategic Border Plan, introduced in 2011, the Brazilian government has deployed interagency resources, including unmanned aerial vehicles, to monitor illicit activity in high-risk locations along its borders and in the remote Amazon region. It also has carried out joint operations with neighboring countries. More recently, the Brazilian government has begun acquiring low-altitude mobile radars and other equipment to support its Integrated Border Monitoring System. That system was initially scheduled to be operational along the entire Brazilian border in 2022, but the Brazilian government now estimates that the system may not be completely in place until 2035 due to budget constraints.81

The United States supports counternarcotics capacity-building efforts in Brazil under a 2008 U.S.-Brazil Memorandum of Understanding on Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement. In 2018, the United States trained nearly 1,000 Brazilian police officers on combatting money laundering and community policing, among other topics.82

Counterterrorism

Despite having little history of terrorism, Brazil began working closely with the United States and other international partners to assess and mitigate potential terrorist threats in the lead-up to hosting the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympic Games. Among other support, U.S. authorities trained Brazilian law enforcement on topics such as countering international terrorism, preventing attacks on soft targets, and identifying fraudulent documents. The Brazilian government also enacted legislation that criminalized terrorism and terrorist financing in 2016, closing a long-standing legal gap that reportedly had hindered counterterrorism investigations and prosecutions.8384 Brazil further strengthened its legal framework for identifying and freezing terrorist assets in 2019 to address deficiencies identified by the intergovernmental Financial Action Task Force.8485

Brazilian officials have used the new legal framework several times in recent years. In the weeks leading up to the 2016 Olympics, they dismantled a loose, online network of Islamic State sympathizers; 12 individuals were detained, and 8 ultimately were convicted and sentenced to between 5 and 15 years in prison for promoting the Islamic State and terrorist attacks through social media.8586 In 2018, Brazilian prosecutors charged 11 individuals with planning to establish an Islamic State cell in Brazil and attempting to recruit fighters to send to Syria.8687 Although some observers have applauded such efforts, others argue that Brazilian authorities are improperly surveilling, and stoking prejudice toward, the country's small Muslim population.87

Brazil historically had been reluctant to adopt specific antiterrorism legislation due to concerns about criminalizing the activities of social movements and other groups that engage in actions of political dissent. President Bolsonaro has reinvigorated those concerns by comparing Brazil's Landless Workers' Movement (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Terra, or MST) and protesters in Chile to terrorists.8889 The Brazilian congress recently restricted the ability of the country's financial intelligence unit to report on terrorist financing, reportedly to prevent Bolsonaro from targeting political and social activists. That restriction could jeopardize Brazil's compliance with global anti-money laundering and antiterrorism financing standards.89

In December 2019, the U.S. Department of State allocated $700,000 of FY2019 Nonproliferation, Anti-Terrorism, Demining and Related Programs aid to Brazil to improve Brazilian law enforcement's capability to deter, detect, and respond to terrorism-related activities. The assistance will fund border security training and other initiatives, with a particular focus on preventing suspected terrorists and terrorist facilitators from transiting the so-called Tri-Border Area (TBA) of Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay.9091 The TBA has long been a haven for smuggling, money laundering, and other illicit activities. In September 2018, for example, Brazilian police arrested an alleged Hezbollah financier in the TBA who the U.S. Department of the Treasury had previously sanctioned as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist pursuant to Executive Order 13224. Brazil does not consider Hezbollah a terrorist organization, but the Bolsonaro Administration reportedly is considering measures to designate it as such.

Defense Cooperation

U.S.-Brazilian military ties have grown considerably over the past decade but have faced occasional setbacks. In the aftermath of a massive January 2010 earthquake in Haiti, U.S. and Brazilian military forces providing humanitarian assistance engaged in their largest combined operations since World War II.9192 Later in 2010, the countries signed a Defense Cooperation Agreement and a General Security of Military Information Agreement intended to facilitate the sharing of classified information. The Brazilian congress did not approve those agreements until 2015, however, due to a cooling of relations after press reports revealed that the U.S. National Security Agency had engaged in extensive espionage in Brazil. A Master Information Exchange Agreement, signed in 2017, implemented the two previous agreements and enabled the countries to pursue bilateral defense-related technology projects.

In July 2019, President Trump designated Brazil as a major non-NATO ally for the purposes of the Arms Export Control Act (22 U.S.C. 2751 et seq.).9293 Among other benefits, that designation offers Brazil privileged access to the U.S. defense industry and increased joint military exchanges, exercises, and training.9394 In FY2019, the U.S. government provided an estimated $666,000 in International Military Education and Training (IMET) assistance to Brazil to strengthen military-to-military relationships, increase the professionalization of Brazilian forces, and enhance the Brazilian military's capabilities. The U.S. government also delivered to Brazil $11.2 million of equipment under the Excess Defense Articles program and $96.7 million of equipment and services under the Foreign Military Sales program.9495 The Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94), does not specifically allocate any military assistance for Brazil, but the Trump Administration requested $625,000 in IMET for Brazil in FY2020.9596 The Trump Administration's FY2021 budget proposal also includes $625,000 in IMET for Brazil.96

Although recent bilateral agreements and the U.S. designation of Brazil as a major non-NATO ally have laid a foundation for closer military ties, the long-term trajectory of the defense relationship may depend on broader geopolitical considerations. For example, U.S. officials reportedly have warned that bilateral military and intelligence cooperation could be in jeopardy if Brazil allows the Chinese telecommunications company Huawei to participate in Brazil's5G cellular network.9798 Brazil may be reluctant to exclude Huawei, however, since the financial and economic benefits of using the company's lower cost components to deploy Brazil's 5G network more quickly may outweigh the less tangible benefits of closer defense ties with the United States. Moreover, the Bolsonaro Administration generally has sought to avoid confrontations with China—Brazil's top trade partner and an important source of foreign investment. During his first year in office, Bolsonaro shifted from expressing concern that China was exerting too much control over key sectors of the Brazilian economy to lauding the strategic partnership between Brazil and China and calling for closer bilateral cooperation in various areas, including science and technology.9899 More broadly, influential sectors of Brazil's military and foreign policy establishments are wary of becoming embroiled in global power rivalries or becoming technologically dependent on any one country.99

Congress has expressed interest in ensuring that U.S. military engagement with Brazil does not contribute to human rights abuses. The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (P.L. 116-92) directs the Secretary of Defense, in coordination with the Secretary of State, to submit a report to Congress regarding U.S.-Brazilian security cooperation. The report is to assess the capabilities of Brazil's military forces and describe the U.S. security cooperation relationship with Brazil, including U.S. objectives, ongoing or planned activities, and the Brazilian military capabilities that U.S. cooperation could enhance. The report is also to assess the human rights climate in Brazil, including the Brazilian military's adherence to human rights and an identification of any Brazilian military or security forces credibly alleged to have engaged in human rights violations that have received or purchased U.S. equipment or training. Moreover, the report is to describe ongoing or planned U.S. cooperation activities with Brazil focused on human rights and the extent to which U.S. security cooperation with Brazil could encourage accountability and promote reform through training on human rights, rule of law, and rules of engagement.

Some Members of Congress also have called for changes to U.S. security cooperation with Brazil. A resolution introduced in September 2019 expressing profound concerns about threats to human rights, the rule of law, democracy, and the environment in Brazil (H.Res. 594, Grijalva) would call for the United States to rescind Brazil's designation as a major non-NATO ally and suspend assistance to Brazilian security forces, among other actions. In contrast, other Members have called for closer U.S. security ties with Brazil, including its inclusion in NATO partnership programs.100

U.S. Support for Amazon Conservation

The U.S. government has supported conservation efforts in Brazil since the 1980s. Current U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) activities are coordinated through the U.S.-Brazil Partnership for the Conservation of Amazon Biodiversity (PCAB). Launched in 2014, the PCAB brings together U.S. and Brazilian governments, private sector companies, and NGOs to strengthen protected area management and promote sustainable development in the Amazon. In addition to providing assistance for federally and state-managed protected areas, USAID works with indigenous and quilombola communities to strengthen their capacities to manage their resources and improve their livelihoods.101102 USAID also supports the private sector-led Partnership Platform for the Amazon, which facilitates private investment in innovative conservation and sustainable development activities.102103 In November 2019, USAID helped establish the Athelia Biodiversity Fund, a Brazilian equity fund that aims to raise $100 million of mostly private capital to invest in similar efforts. In addition to those long-term development programs, USAID's Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance deployed a team of wildfire experts to assist Brazilian fire investigators in 2019.

Several other U.S. agencies are engaged in Brazil, often in collaboration with or with funding transferred from USAID. The U.S. Forest Service, for example, provides technical assistance to the Brazilian government, NGOs, and cooperatives intended to improve protected area management, reduce the threat of fire, conserve migratory bird habitat, and facilitate the establishment of sustainable value chains for forest products.103104 NASA also has provided data and technical support to Brazil to help the country better monitor Amazon deforestation.104

President Trump has not requested funding for environmental programs in Brazil in any of his budget proposals. Nevertheless, Congress has continued to fund conservation activities in the country. In the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94), Congress appropriated $15 million for the Brazilian Amazon, including $5 million to address fires in the region.

Some Members of Congress have called on the Brazilian and U.S. governments to do more to conserve the Amazon. For example, a resolution introduced in the Senate in September 2019 (S.Res. 337, Schatz) would express bipartisan concern about fires and illegal deforestation in the Amazon, call on the Brazilian government to strengthen environmental enforcement and reinstate protections for indigenous communities, and back continued U.S. assistance to the Brazilian government and NGOs. The Act for the Amazon Act (H.R. 4263, DeFazio), introduced in September 2019, would take a more punitive approach. It would ban the importation of certain fossil fuels and agricultural products from Brazil, prohibit certain types of military-to-military engagement and security assistance to Brazil, and forbid U.S. agencies from entering into free trade negotiations with Brazil.

Outlook

More than five years after the country fell into recession and more than three years after the controversial impeachment and removal from office of President Rousseff, Brazil remains mired in difficult domestic circumstances. There are some signs that economic growth may be accelerating slowly, but tens of millions of Brazilians continue to struggle with poverty and precarious employment conditions. Repeated budget cuts have reduced social services for the most vulnerable and have weakened the Brazilian government's capacity to address other challenges, such as high levels of crime and increasing deforestation. President Bolsonaro was elected, in part, on his pledge to clean up the political system, but his interference in justice sector agencies and frequent attacks on the press, civil society groups, and other branches of government have placed additional stress on the country's already-strained democratic institutions. Brazilian policymakers are likely to remain focused on these internal challenges for the next several years, limiting Brazil's ability to take on regional responsibilities or exert its influence internationally.

U.S.-Brazilian relations have grown closer since 2019, as President Bolsonaro's foreign policy has prioritized alignment with the Trump Administration. In addition to coordinating on international affairs, the U.S. and Brazilian governments have taken steps to bolster commercial ties and enhance security cooperation. Nonetheless, policy differences have emerged over sensitive issues, such as bilateral trade barriers and relations with China, which affect the economic and geopolitical interests of both countries. Those disagreements suggest the Trump and Bolsonaro Administrations may need to engage in more extensive consultations and confidence-building measures if they intend to avoid the historic pattern of U.S.-Brazilian relations, in which heightened expectations give way to mutual disappointment and mistrust.

The 116th Congress may continue to shape U.S.-Brazilian relations using its legislative and oversight powers. Although there appears to be considerable support in Congress for forging a long-term strategic partnership with Brazil, many Members may be reluctant to advance major bilateral commercial or security cooperation initiatives in the near term, given their concerns about democracy, human rights, and the environment in Brazil. For the time being, Congress may continue appropriating funding for programs with broad support, such as Amazon conservation efforts, while Members continue to advocate for divergent policy approaches toward the Bolsonaro Administration.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

See, for example, Letter from Senator Marco Rubio to President Donald J. Trump, December 20, 2019. |

|

| 2. |

See, for example, "Senate Foreign Relations Committee Holds Hearing on Pending Nominations," CQ Transcriptions, December 17, 2019; and Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, "Climate Change," Remarks in the Senate, Congressional Record, vol. 165, part 148 (September 16, 2019), p. S5496. |

|

| 3. |

For information on U.S. policy prior to and following the coup, see Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXXI, South and Central America; Mexico, eds. David C. Geyer and David H. Herschler (Washington: GPO, 2004), Documents 181-244, at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v31/ch5. |

|

| 4. |

Ministério Público Federal, Procuradoria Federal dos Direitos do Cidadão, "PFDC Contesta Recomendação de Festejos ao Golpe de 64," press release, March 26, 2019. |

|

| 5. |

Cristiano Romero, "O Legado de Lula na Economia," Valor Online, December 29, 2010. |

|

| 6. |

International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Economic Outlook Database October 2019, October 11, 2019. The poverty line is defined as the income necessary to cover basic expenses, such as food, clothing, housing, and transit. Marcelo Neri, A Escalada da Desigualdade, Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Centro de Políticas Sociais, August 2019, p. 15. Hereinafter, Neri, A Escalada da Desigualdade. |

|

| 7. |

Neri, A Escalada da Desigualdade. |

|

| 8. |

Alfredo Cuevas et al., "An Eventful Two Decades of Reforms, Economic Boom, and a Historic Crisis," in Brazil: Boom, Bust, and the Road to Recovery, IMF, 2018; and Pedro Mendes Loureiro and Alfredo Saad-Filho, "The Limits of Pragmatism: The Rise and Fall of the Brazilian Workers' Party (2002-2016)," Latin American Perspectives, vol. 46, no. 1 (2019). |

|

| 9. |

IMF, Staff Report for the 2018 Article IV Consultation, June 20, 2018. |

|

| 10. |

IMF, "World Economic Outlook Database: October 2019," October 11, 2019; and Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), "PNAD Contínua: Taxa de Desocupação é de 11,0% e Taxa de Subutilização é de 23,0% no Trimestre Encerrado em Dezembro," press release, January 31, 2020. |

|

| 11. |

Neri, A Escalada da Desigualdade, pp. 5, 15. |

|

| 12. |

According to Brazil's 2010 census, 43.1% of Brazilians self-identify as mixed race and 7.6% self-identify as black. IBGE, Censo Demográfico 2010, November 2011; and IBGE, Desigualdades Sociais por Cor ou Raça no Brasil, 2019. |

|

| 13. |

Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, Anuário Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, 2019; and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Study on Homicide, 2019. |

|

| 14. |

Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, "Violence Against Black People in Brazil," infographic, 2019, at http://www.forumseguranca.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/infografico-consicencia-negra-2019-FINAL_ingl%C3%AAs_site.pdf. |

|

| 15. |

Felipe Nunes and Carlos Ranulfo Melo, "Impeachment, Political Crisis and Democracy in Brazil," Revista de Ciencia Política, vol. 37, no. 2 (2017). |

|

| 16. |

Corporación Latinobarómetro, Informe 2018, November 2018. |

|

| 17. |

Sylvio Costa and Edson Sardinha, "O que Você Precisa Saber para Entender o Novo Congresso Brasileiro," Congresso em Foco, October 9, 2018. |

|

| 18. |

See, for example, Brian Winter, "System Failure: Behind the Rise of Jair Bolsonaro," Americas Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 1, (January 2018). |

|

| 19. |

Matias Spektor, "It's Not Just the Right That's Voting for Bolsonaro. It's Everyone." Foreign Policy, October 26, 2018. As of mid-2018, 58% of Brazilians expressed trust in the military and 73% expressed trust in the churches, according to Corporación Latinobarómetro. |

|

| 20. |

Câmara dos Deputados, "Bancada Atual," accessed in January 2020. |

|

| 21. |

See, for example, Andres Schipani, "Brazil: Jair Bolsonaro Pushes Culture War over Economic Reform," Financial Times, August 24, 2019; and Paulo Trevisani, "Brazil's President Hits the Street, Railing Against the Media," Wall Street Journal, February 11, 2020. |

|

| 22. |

U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Brazil-U.S. Business Council, "What Can Brazil Expect from Concessions and Privatizations in 2020?," Brazil Investment Monitor, February 14, 2020. |

|

| 23. |

Andres Schipani and Bryan Harris, "Can Brazil's Pension Reform Kick-Start the Economy?," Financial Times, October 22, 2019. |

|

| 24. |

IMF, Tentative Stabilization, Sluggish Recovery?, World Economic Outlook Update, January 20, 2020. |

|

| 25. |

IBGE, "PNAD Contínua: Taxa de Desocupação é de 11,0% e Taxa de Subutilização é de 23,0% no Trimestre Encerrado em Dezembro," press release, January 31, 2020. |

|

| 26. |

See, for example, Gray Newman, "Was It All Her Fault? An Economist Re-examines Brazil's Crisis," Americas Quarterly, October 13, 2016; and "Analysis – Brazil's Growth at Mercy of Hotly Disputed 'Expansionary Austerity,'" Reuters, January 21, 2020. |

|

| 27. |

"Número de Assassinatos Cai 19% no Brasil em 2019 e é o Menor da Série Histórica," G1, February 14, 2020; and Karina Nascimento, "Principais Crimes Registraram Queda no Estado em 2019," Governo do Rio de Janeiro, Instituto de Segurança Pública, January 21, 2020. |

|

| 28. |

André Cabette Fábio, "A Queda da Criminalidade no Brasil. E o Discurso de Moro," Nexo Jornal, January 6, 2020. |

|

| 29. |

Ryan C. Berg, "Brazil's Bolsonaro Continues to Be His Own Worst Enemy," American Enterprise Institute, September 24, 2019; and Guilherme France, Brazil: Setbacks in the Legal and Institutional Anti-Corruption Frameworks, Transparency International, 2019. |

|

| 30. |

See, for example, Naiara Galarraga Gortázar, "El Deterio de la Democracia en Brasil se Agrava Bajo el Mandato de Bolsonaro," El País, January 13, 2020. |

|

| 31. |

See, for examples, "Brazil: Print Media Threatened by Presidential Decree," Latin News Daily, August 8, 2019; Mauricio Savarese, "Brazil's Bolsonaro Targets Minorities on 1st Day in Office," Associated Press, January 3, 2019; and Gabriel Stargardter, "Bolsonaro Presidential Decree Grants Sweeping Powers over NGOs in Brazil," Reuters, January 2, 2019. |

|

| 32. |

Brian Winter, "'It's Complicated': Inside Bolsonaro's Relationship with Brazil's Military," Americas Quarterly, December 17, 2019; and Nathalia Passarinho, "Atuação de Militares é 'Surpresa Positiva' do Governo Bolsonaro, Dis Professor de Harvard que Estuda Brasil há 30 Anos," BBC News Brasil, April 14, 2019. |

|

| 33. |

See, for examples, "Brazil: Journalists Denounce Increased Attacks," Latin News Daily, January 17, 2020; Maria Elena Bucheli, "Bolsonaro 'Turned Me into a Pariah,' Says Gay Lawmaker Who Fled Brazil," Agence France Presse, March 20, 2019; and "Brazil: Indigenous Violence on the Rise," Latin American Security & Strategic Review, January 2020. |

|

| 34. |

Figures based on an average of three polls. Datafolha, "Avaliação do Presidente Jair Bolsonaro," December 2019; Confederação Nacional da Indústria (CNI), "Avaliação do Governo," Pesquisa CNI-Ibope, December 2019; and Confederação Nacional do Transporte (CNT), "Pesquisa CNT/MDA," January 2020. |

|

| 35. |

Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE), "Monitoramento dos Focos Ativos por Bioma," at http://queimadas.dgi.inpe.br/queimadas/portal-static/estatisticas_estados/. For more information on the fires, see CRS In Focus IF11306, Fire and Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, by Pervaze A. Sheikh et al. |

|

| 36. |

Portions of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, and Venezuela are located in the Amazon Basin. The rainforest extends beyond the Amazon Basin into Suriname and French Guiana. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Global International Waters Assessment: Amazon Basin, GIWA Regional Assessment 40b, Kalmar, Sweden, 2004, p. 15. |

|

| 37. |

Edna Rödig et al., "The Importance of Forest Structure for Carbon Fluxes of the Amazon Rainforest," Environmental Research Letters, vol. 13, no. 5 (2018), p. 9; Hemholtz Centre for Environmental Research, "The Forests of the Amazon Are an Important Carbon Sink," press release, November 8, 2019; and Pierre Friedlingstein et al., "Global Carbon Budget 2019," Earth System Science Data, vol. 11, no. 4 (2019), p. 1803. |

|

| 38. |

D. C. Zemp et al., "Deforestation Effects on Amazon Forest Resilience," Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 44, no. 12 (2017). |

|

| 39. |

Thomas Lovejoy and Carlos Nobre, "Amazon Tipping Point: Last Chance for Action," Science Advances, vol. 5, no. 12 (2019). |

|

| 40. |

UNEP, Global International Waters Assessment: Amazon Basin, GIWA Regional Assessment 40b, Kalmar, Sweden, 2004, p. 16. |

|

| 41. |

Eric A. Davidson et al., "The Amazon Basin in Transition," Nature, vol. 481 (2012), p. 321. |

|

| 42. |

Presidência da República, Casa Civil, Plano de Ação para a Prevenção e Controle do Desmatamento na Amazônia Legal, March 2004. |

|

| 43. |

Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information, "Amazonia 2019 – Protected Areas and Indigenous Territories," map, 2019. |

|

| 44. |

Philip Fearnside, "Business as Usual: A Resurgence of Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon," Yale Environment 360, April 18, 2017. Hereinafter, Fearnside, "Business as Usual." |

|

| 45. |

Fearnside, "Business as Usual"; and William D. Carvalho et al., "Deforestation Control in the Brazilian Amazon: A Conservation Struggle Being Lost as Agreements and Regulations Are Subverted and Bypassed," Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation, vol. 17, no. 3 (2019). |

|

| 46. |

Gustavo Faleiros, "China's Brazilian Beef Demand Linked to Amazon Deforestation Risk," Diálogo Chino, October 23, 2019; and Richard Fuchs et al., "U.S.-China Trade War Imperils Amazon Rainforest," Nature, vol. 567 (March 28, 2019). |

|

| 47. |

Marcos Caramuru de Paiva, "Brazil and China: A Brief Analysis of the State of Bilateral Relations," in Brazil-China: The State of the Relationship, Belt and Road, and Lessons for the Future (Rio de Janeiro: Centro Brasileiro de Relações Internacionais, 2019), p. 122. Also see Fred Gale, Constanza Valdes, and Mark Ash, Interdependence of China, United States, and Brazil in Soybean Trade, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, June 2019. |

|

| 48. |

See, for example, Kathryn Hochstetler, "This Isn't the First Time Fires Have Ravaged the Amazon," Foreign Policy, August 29, 2019; and Rubens Ricupero et al., Comunicado dos Ex-Ministros de Estado do Meio Ambiente, May 8, 2019. |

|

| 49. |

Fabiano Maisonnave, "Declarações Antiambientalistas de Políticos Aceleram Desmatamento, Diz Estudo," Folha de São Paulo, December 16, 2019; Stephen Eisenhammer, "'Day of Fire': Blazes Ignite Suspicion in Amazon Town," Reuters, September 11, 2019; Marina Lopes, "Illegal Miners, Feeling Betrayed, Call on Bolsonaro to End Environmental Crackdown in Amazon," Washington Post, September 10, 2019; and INPE, "Taxa PRODES Amazônia – 2004-2019," November 18, 2019. |

|

| 50. |

"Bolsonaro Diz que Desmatamento é Cultural no Brasil e Não Acabará," Folha de São Paulo, November 20, 2019. Humans intentionally set the majority of fires in the Amazon to burn recently cleared trees and woody debris, crop residue, overgrown pastures, and roadside vegetation. This practice, sometimes referred to as "slash and burn agriculture," transfers nutrients to poor tropical soils and helps prepare land for pastures and crops. |

|

| 51. |

Confederação Nacional da Indústria (CNI), "Avaliação do Governo," Pesquisa CNI-Ibope, December 2019, p. 6. |

|

| 52. |

Federative Republic of Brazil, Intended Nationally Determined Contribution, September 21, 2016. "CO₂e" is a metric used to express the impact of emissions from differing greenhouse gasses in a common unit by converting each gas to the equivalent amount of CO₂ that would have the same effect on increasing global average temperature. |

|

| 53. |

UNEP, Emissions Gap Report 2018, November 2018, p. 9. |

|

| 54. |

Observatório do Clima, "Estimativas de Emissões de Gases de Efeito Estufa do Brasil 1970-2018," November 5, 2019. |

|

| 55. |

"Brazil to Remain in Paris Agreement 'for Now,' Bolsonaro Says," Valor International, January 22, 2019. |

|

| 56. |