Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Changes from February 6, 2020 to May 20, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Contents

- Political History

- Regime Structure, Stability, and Opposition

- Unelected or Indirectly Elected Institutions: The Supreme Leader, Council of Guardians, and Expediency Council

- The Supreme Leader

- Council of Guardians and Expediency Council

- Domestic Security Organs

- Elected Institutions/Recent Elections

- The Presidency

- The Majles

- The Assembly of Experts

- Recent Elections

- Periodic Unrest Challenges the Regime

- Human Rights Practices

- U.S.-Iran Relations, U.S. Policy, and Options

- Reagan Administration: Iran Placed on "Terrorism List"

- George H. W. Bush Administration: "Goodwill Begets Goodwill"

- Clinton Administration: "Dual Containment"

- George W. Bush Administration: Iran Part of "Axis of Evil"

- Obama Administration: Pressure, Engagement, and the JCPOA

- Trump Administration: JCPOA Exit and "Maximum Pressure"

- Withdrawal from the JCPOA and Subsequent Pressure Efforts

- Policy Elements and Options

- Engagement and Improved Bilateral Relations

- Military Action

- Authorization for Force Issues

- Economic Sanctions

- Regime Change

- Democracy Promotion and Internet Freedom Efforts

Summary

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and

May 20, 2020

Options

Kenneth Katzman

U.S.-Iran relations have been mostly adversarial since the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran,

Specialist in Middle

occasionally flaring into direct conflict while at other times witnessing negotiations or tacit

Eastern Affairs

cooperation on selected issues. U.S. officials have consistently identified Iran'’s support for

militant Middle East groups as a significant threat to U.S. interests and allies, and Iran'’s nuclear program took precedence in U.S. policy after 2002 as that program advanced.

During 2010-2016, the Obama Administration led a campaign of broad international economic pressure on Iran to persuade it to agree to strict limits on the program, producing the

The Obama Administration sought to change longstanding policy toward Iran by engaging it directly to obtain a limited July 2015 multilateral nuclear agreement known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). That agreement exchanged

sanctions relief for limits on Iran'’s nuclear program, but did not contain binding curbs on Iran'’s missile program or its regional interventions, or any reference to Iranian human rights abuses.

The Trump Administration cited the JCPOA's deficiencies in its May 8, 2018, announcement that the United States would exit the accord and reimpose all U.S. secondary sanctions. The stated intent of that step, as well as subsequent imposition of additional sanctions on Iran, is to apply "maximum pressure" on Iran to compel it to change its behavior, including negotiating a new JCPOA that takes into accountrequirements that the Iranian government end its human rights abuses. The Trump Administration largely returned to prior policies of seeking to weaken Iran strategically. Trump Administration officials cited

the JCPOA’s perceived shortcomings in a May 8, 2018 U.S. exit from the JCPOA and the subsequent re-imposition of all U.S. secondary sanctions to apply “maximum pressure” on Iran. The stated intent of Trump Administration policy is to compel Iran to change its behavior, including negotiating a new nuclear agreement that encompasses the broad range of U.S. concerns. Iran has responded to the maximum pressure campaign by undertaking actions against commercial shipping in the Persian Gulf, supporting attacks by allies in Iraq and Yemen to attack U.S., Saudi, and other targets in the region, and by exceeding nuclear limits set by the JCPOA. The Administration has added forces to the Gulf region, as well as explained the January 23, 2020, airstrike that killed a top Iranian commander, Qasem Soleimani, as efforts to deter further such Iranian or Iran -backed actions.

Along with the Trump Administration shift in policy, the United States and Iran have had minimal direct contact since 2017. However, President Trump continues to indicate-backed actions.

Before and since the escalation of U.S.-Iran tensions in May 2019, President Trump has indicated a willingness to meet with Iranian leaders without preconditions. Iranian leaders say there will be no direct high level U.S.-Iran meetings until the United States reenters the 2015 JCPOA and lifts U.S. sanctions as provided for in that agreement. Administration statements and reports detail a long officials have detailed a litany of objectionable behaviors that Iran must change for there to be a normalization of relations.

, most of which require Iran to cease arming and supporting armed factions in the region.

Some experts assert that the threat posed by Iran stems from the nature and ideology of Iran'’s regime, and that the underlying, if unstated, unstated goal of Trump Administration policy is to bring about regime collapse. In the context of escalating U.S.-Iran tensions, President Trump has specifically denied that this is his Administration's goalPresident Trump has specifically denied that t his is the U.S. objective. Any U.S. regime change strategy presumably would take advantage of divisions and fissures within Iran, as well as evident popular unrest resulting from political and economic frustration. Unrest in recent years has not appeared to threaten the regime's grip on power. However, significantSignificant protests and riots, including burning of some government installations and private establishments, broke out on November 15 in response to a government announcement of a reduction in fuel subsidies, as well as in January 2020 in response to the regime's concealment of responsibility for accidentally downing a Ukraine passenger aircraft.

U.S. pressure has widenedhave broken out since 2017. There has not been unrest

recently in response to the government’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak, which has affected Iran significantly and in which the official response has been widely criticized as ineffective.

There are also significant leadership differences in Iran. Hassan Rouhani, who seeks to improve Iran'’s relations with the West, including the United States, won successive presidential elections in 2013 and 2017, and reformist and moderate candidates won overwhelmingly in concurrent municipal council elections in all the major cities. YetHowever, the killing of Soleimani contributed to a significant victory bySoleimani might potentially improve prospects for hardliners in the February 21, 2020, Majles (parliamentary) elections. Hardliners also continue to control the state institutions that maintain internal security largely through suppression and by all accounts have been emboldened by U.S. policy to challenge the United States and pursue significantsignific ant U.S. concessions in order to avoid conflict.

See also CRS Report R43333, Iran Nuclear Agreement and U.S. Exit, by Paul K. Kerr and Kenneth Katzman; CRS Report RS20871, Iran Sanctions, by Kenneth Katzman; CRS Report R44017, Iran'’s Foreign and Defense Policies, by Kenneth Katzman; and CRS Report R45795, U.S.-Iran Conflict and Implications for U.S. Policy, by Kenneth Katzman, Kathleen J. McInnis, and Clayton Thomas.

Political History

Iran is a country of nearly 80 million

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 18 link to page 21 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 27 link to page 28 link to page 31 link to page 31 link to page 32 link to page 34 link to page 35 link to page 37 link to page 42 link to page 43 link to page 10 link to page 23 link to page 34 link to page 39 Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Contents

Political History.............................................................................................................. 1 Regime Structure, Stability, and Opposition ........................................................................ 2

Unelected or Indirectly Elected Institutions: The Supreme Leader, Council of

Guardians, and Expediency Council........................................................................... 4

The Supreme Leader ............................................................................................. 4 Council of Guardians and Expediency Council ......................................................... 4 Domestic Security Organs ..................................................................................... 6

Elected Institutions/Recent Elections ............................................................................ 7

The Presidency .................................................................................................... 7 The Majles .......................................................................................................... 8 The Assembly of Experts ....................................................................................... 8 Recent Elections .................................................................................................. 8

Periodic Unrest Chal enges the Regime ................................................................. 14

Human Rights Practices ................................................................................................. 17 U.S.-Iran Relations, U.S. Policy, and Options .................................................................... 19

Reagan Administration: Iran Placed on “Terrorism List” ................................................ 20 George H. W. Bush Administration: “Goodwil Begets Goodwill”................................... 20 Clinton Administration: “Dual Containment” ............................................................... 21 George W. Bush Administration: Iran Part of “Axis of Evil”........................................... 21 Obama Administration: Pressure, Engagement, and the JCPOA ...................................... 21

Trump Administration: JCPOA Exit and “Maximum Pressure” ....................................... 23

Withdrawal from the JCPOA and Subsequent Pressure Efforts .................................. 24

Policy Elements and Options .......................................................................................... 27

Engagement and Improved Bilateral Relations ............................................................. 27 Military Action........................................................................................................ 28 Economic Sanctions................................................................................................. 30 Regime Change ....................................................................................................... 31

Democracy Promotion and Internet Freedom Efforts................................................ 33

Figures

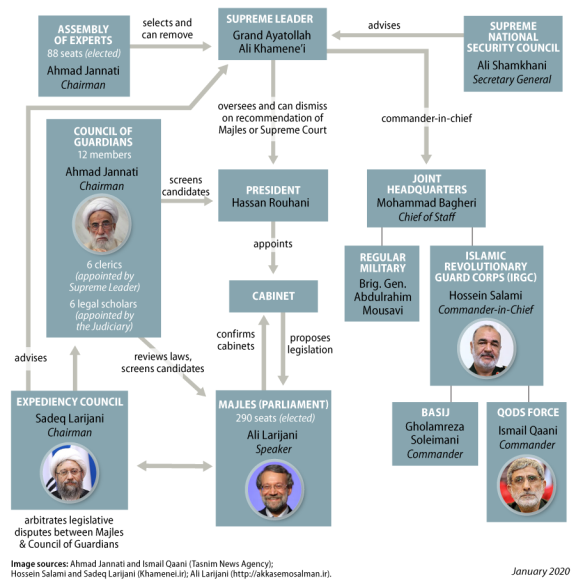

Figure 1. Structure of the Iranian Government ................................................................... 38 Figure 2. Map of Iran..................................................................................................... 39

Tables Table 1. Other Major Institutions, Factions, and Individuals ................................................... 6 Table 2. Human Rights Practices: General Categories ......................................................... 19 Table 3. Summary of U.S. Sanctions Against Iran .............................................................. 30 Table 4. Iran Democracy Promotion Funding..................................................................... 35

Congressional Research Service

link to page 43 Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 39

Congressional Research Service

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Political History Iran is a country of nearly 80 mil ion people, located in the heart of the Persian Gulf region. The United States was an allyal y of the late Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi ("“the Shah"”), who ruled from 1941 until his ouster in February 1979. The Shah assumed the throne when Britain and Russia forced his father, Reza Shah Pahlavi (Reza Shah), from power because of his perceived alignment with Germany in World War II. Reza Shah had assumed power in 1921 when, as an

officer in Iran'’s only military force, the Cossack Brigade (reflecting Russian influence in Iran in the early 20th20th century), he launched a coup against the government of the Qajar Dynasty, which had ruled since 1794. Reza Shah was proclaimed Shah in 1925, founding the Pahlavi dynasty. The Qajar dynasty had been in decline for many years before Reza Shah'’s takeover. That dynasty'dynasty’s perceived manipulation by Britain and Russia had been one of the causes of the 1906

constitutionalist movement, which forced the Qajar dynasty to form Iran'’s first Majles (parliament) in August 1906 and promulgate a constitution in December 1906. Prior to the Qajars, what is now Iran was the center of several Persian empires and dynasties whose reach shrank steadily over time. After the 16th16th century, Iranian empires lost control of Bahrain (1521), Baghdad (1638), the Caucasus (1828), western Afghanistan (1857), Baluchistan (1872), and what is now Turkmenistan (1894). Iran adopted Shia Islam under the Safavid Dynasty (1500-1722), which

ended a series of Turkic and Mongol conquests.

The Shah was anti-Communist, and

During the Cold War, the United States viewed his governmentthe Shah as a bulwark against the expansion of

Soviet influence in the Persian Gulf and a counterweight to pro-Soviet Arab regimes and movements. Israel maintained a representative office in Iran during the Shah'’s time and the Shah supported a peaceful resolution of the Arab-Israeli dispute. In 1951, under pressure from nationalists in the Majles (parliament) who gained strength in 1949 elections, he appointed a popular nationalist parliamentarian, Dr. Mohammad Mossadeq, as prime minister. Mossadeq was widely considered left-leaning, and the United States opposed his drive to nationalize the oil

industry, which had been controlled since 1913 by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. His followers began an uprising in August 1953 when the Shah tried to dismiss him, and the Shah fled. The Shah was restored to power in a CIA-supported uprising that toppled Mossadeq ("“Operation Ajax"

Ajax”) on August 19, 1953.

The Shah tried to modernize Iran and orient it toward the West, but in so doing he alienated the Shia clergy and religious Iranians. He incurred broader resentment by using his SAVAK intelligence intel igence service to repress dissent. The Shah exiled Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1964 because of Khomeini'’s active

opposition to what he asserted were the Shah'’s anticlerical policies and forfeiture of Iran's ’s sovereignty to the United States. Khomeini fled to and taught in Najaf, Iraq, a major Shia theological center. In 1978, three years after the March 6, 1975, Algiers Accords between the Shah and Iraq'’s Baathist leaders that temporarily ended mutual hostile actions, Iraq expelled expel ed Khomeini to France, where he continued to agitate for revolution that would establish Islamic government in Iran. Mass demonstrations and guerrillaguerril a activity by pro-Khomeini and other anti-

government forces caused the Shah'’s government to collapse. Khomeini returned from France on

February 1, 1979, and, on February 11, 1979, he declared an Islamic Republic of Iran.

Khomeini'

Khomeini’s concept of velayat-e-faqih (rule by a supreme Islamic jurisprudent, or "“Supreme Leader"Leader”) was enshrined in the constitution that was adopted in a public referendum in December 1979 (and amended in 1989). The constitution provided for the post of Supreme Leader of the Revolution. The regime based itself on strong opposition to Western influence, and relations between the United States and the Islamic Republic turned openly hostile after the November 4, 1979, seizure of the U.S. Embassy and its U.S. diplomats by pro-Khomeini radicals, which began

Congressional Research Service

1

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

the so-cal edthe so-called hostage crisis that ended in January 1981 with the release of the hostages.11 Ayatollah

Khomeini died on June 3, 1989, and was succeeded by Ayatollah Ali Khamene'i.

Khamene’i.

The regime faced serious unrest in its first few years, including a June 1981 bombing at the

headquarters of the Islamic Republican Party (IRP) and the prime minister'’s office that killed kil ed several senior elected and clerical leaders, including then-Prime Minister Javad Bahonar, elected President Ali Raja' Raja’i, and IRP head and top Khomeini disciple Ayatollah Mohammad Hussein Beheshti. The regime used these events, along with the hostage crisis with the United States, to justify purging many of the secular, liberal, and left-wing personalities that had been prominent in

the years just after the revolution. Examples included the regime'’s first Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan; the pro-Moscow Tudeh Party (Communist); the People'’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI, see below); and the first elected president, Abolhassan Bani Sadr. The regime was under economic and military threat during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War.

, in part due to the destruction of its oil export capacity and its need to ration goods. Regime Structure, Stability, and Opposition

The structure of authority in Iran defies easy categorization. There are elected leadership posts and a diversity of opinion among the ruling elite, but Iran'’s constitution—adopted in public referenda in late 1979 and again in 1989—reserves paramount decisionmaking authority for a "“Supreme Leader"” (known in Iran as "“Leader of the Revolution"”). The President and the Majles (unicameral parliament) are directly elected, and since 2013, there have been elections for

municipal councils that select mayors and set local development priorities. Throughout Iran's ’s power structure, there are disputes between those who insist on ideological purity and those considered more pragmatic. Nonetheless, the preponderant political power wielded by the Shia Islamic clergy and the security apparatus has contributed to the eruption of repeated periodic unrest from minorities, intellectualsintel ectuals, students, labor groups, the poor, women, and members of Iran's ’s

minority groups. (Iran'’s demographics are depicted in a text box below.)

U.S. officials in successive Administrations have accused Iran'’s regime of widespread corruption, both within the government and among its pillarspil ars of support. In a speech on Iran on July 22,

2018, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo characterized Iran'’s government as "“something that resembles the mafia more than a government."” 2 He detailed allegationsal egations of the abuse of privileges enjoyed by Iran'’s leaders and supporting elites to enrich themselves and their supporters at the expense of the public good.2 The State Department'’s September 2018 "“Outlaw Regime"” report (p. 41) states that "“corruption and mismanagement at the highest levels of the Iranian regime have

produced years of environmental exploitation and degradation throughout the country."

Policies

Earlier,

Photograph from http://www.leader.ir |

. Sources: various press Congressional Research Service 3 Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options Unelected or Indirectly Elected Institutions: The Supreme Leader, Council of Guardians, and Expediency Council

Iran'’s power structure consists of unelected or indirectly elected persons and institutions.

The Supreme Leader

At the apex of the Islamic Republic'’s power structure is the "“Supreme Leader."” He is chosen by an elected body—the Assembly of Experts—which also has the constitutional power to remove

him, as well wel as to redraft Iran'’s constitution and submit it for approval in a national referendum. The Supreme Leader is required to be a senior Shia cleric. Upon Ayatollah Khomeini' Khomeini’s death, the Assembly selected one of his disciples, Ayatollah Ali Khamene' Khamene’i, as Supreme Leader.34 Although he has never had Khomeini'’s undisputed political or religious authority, the powers of the office

ensure that Khamene'’i is Iran'’s paramount leader.

The Supreme Leader can remove an elected president, if the judiciary or the Majles (parliament) assert cause for removal. The Supreme Leader appoints half of the 12-member Council of

Guardians, al members of the Expediency Council, and the judiciary head.

Under the constitution, the Supreme Leader is commander-in-chief of the armed forces, giving him the power to appoint commanders.

Khamene'Khamene’i appoints five out of the nine members of the country'

country’s highest national security body, the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), on which sit the heads of the regime'’s top military, foreign policy, and domestic security organizations. In September 2013, seniorSenior IRGC leader and former Defense Minister Ali Shamkhani, who generally espouses

more moderate views than his IRGC peers, has headed that body since September 2013.5

Succession to Khamene’i

more moderate views than his IRGC peers, was named to head that body.4 The Supreme Leader can remove an elected president, if the judiciary or the Majles (parliament) assert cause for removal. The Supreme Leader appoints half of the 12-member Council of Guardians, all members of the Expediency Council, and the judiciary head.

Succession to Khamene'i

There is no designated successor or immediately obvious choice to succeed Khamene'’i. The Assembly of Experts could conceivably use a constitutional provision to set up a three-person leadership council as successor rather than select one new Supreme Leader. Khamene'’i reportedly favors Hojjat ol-Eslam Ibrahim Raisi, whom he appointed in March 2019 as head of the judiciary, and in 2016 to head the powerful Shrine of Imam Reza (Astan-e Qods Razavi) in Mashhad, which controls vast property and many businesses in the province. Raisi has served as state

prosecutor and was allegedlyal egedly involved in the 1988 massacre of prisoners and other acts of repression.5

repression.6 Raisi lost the May 2017 presidential election to Rouhani.

Raisi'

Raisi’s predecessor as judiciary chief, Ayatollah Sadeq Larijani,6 7 remains a succession candidate. Another contender is hardline Tehran Friday prayer leader Ayatollah Ahmad Khatemi, and some

consider President Rouhani as a contender as well.

wel . Council of Guardians and Expediency Council

Two appointed councils play a major role on legislation, election candidate vetting, and policy.

Council of Guardians

4 At the time of his selection as Supreme Leader, Khamene’i was generally referred to at the rank of Hojjat ol-Islam, one rank below Ayatollah, suggesting his religious elevation was political rather than through traditional mechanisms.

5 Shamkhani was sanctioned by the Administration in January 2020 as part of the Supreme Leader’s office. See CRS Report RS20871, Iran Sanctions, by Kenneth Katzman.

6 “Iran cleric linked to 1988 mass executions to lead judiciary.”Associated Press, March 7, 2019. 7 Larijani was sanctioned by the Administration in 2019.

Congressional Research Service

4

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Council of Guardians

The 12-member Council of Guardians (COG) consists of six Islamic jurists appointed by the Supreme Leader and six lawyers selected by the judiciary and confirmed by the Majles. Each councilor serves a six-year term, staggered such that half the body turns over every three years. Currently headed by Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati, who is over 90 years of age, the conservative-

controlled body reviews legislation to ensure it conforms to Islamic law. It also vets election candidates by evaluating their backgrounds according to constitutional requirements that each candidate demonstrate knowledge of Islam, loyalty to the Islamic system of government, and other criteria that are largely subjective. The COG also certifies election results. Municipal

council candidates are vetted not by the COG but by local committees established by the Majles.

Expediency Council

The Expediency Council was established in 1988 to resolve legislative disagreements between the Majles and the COG. It has since evolved into primarily a policy advisory body for the Supreme Leader, and it employs researchers and experts to develop policy options on various issues. Its members serve five-year terms. Longtime regime stalwart Ayatollah Ali Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani was reappointed as its chairman in February 2007 and served in that position served as the body’s chairman until his January 2017 death. In August 2017, the Supreme Leader named a new, expanded (

expanded the council from 42 to 45 members) Council, with, and former judiciary head Ayatollah Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi asbecame chairman. Shahroudi passed away in December 2018 and Sadeq Larijani, who was then head of the judiciary, was appointed by the Supreme Leader as his replacement. Iran’s president and speaker of Majles attend the body’s sessions in their official

capacities.

Congressional Research Service

5

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Table 1. Other Major Institutions, Factions, and Individuals

Regime/Pro-regime

The regime derives support from a network of organizations and institutions such as those discussed below.

Senior Shia

The most senior Shia clerics, most of whom are in Qom, are general y “quietists”—they

Clerics/Grand

assert that the senior clergy should general y refrain from replacement. President Hassan Rouhani and Majles Speaker Ali Larijani attend the body's sessions in their official capacities. The council includes former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

|

Regime/Pro-regime The regime derives support from a network of organizations and institutions such as those discussed below. |

|

|

Senior Shia Clerics/Grand Ayatollahs |

|

|

Religious Foundations ("Bonyads") |

Religious

Iran has several |

|

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) |

|

|

Society of Militant Clerics |

|

Sources: Various press accounts and author conversations with Iran experts in and outside Washington, DC. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo "“Supporting Iranian Voices,"” Reagan Library, California, July 22, 2018.

The IRGC is discussed extensively in CRS Report R44017, Iran’s Foreign and Defense Policies, by Kenneth Katzman. See also CRS Insight IN11093, Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Named a Terrorist Organization, by Kenneth Katzman.

Domestic Security Organs

Domestic Security Organs

The leaders and senior officials of a variety of overlapping domestic security organizations form a parallel paral el power structure that is largely under the direct control of the Supreme Leader in his capacity as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. State Department and other human rights reports on Iran repeatedly assert that internal security personnel are not held accountable for

human rights abuses. Several security organizations and their senior leaders are sanctioned by the

United States for human rights abuses and other violations of U.S. Executive Orders.

The domestic security organs include the following:

-

The IRGC and

BasijBasij. The IRGC'‘s domestic security role is implementedprimarilyprimarily through its volunteer militiaforce calledforce cal ed the Basij. To suppress large and violent antigovernment demonstrations, the Basij gets backing from the IRGC, whose bases are located mostly in urban areas and which can quickly intervene. In July 2019,Supreme Leader Khamene'i replaced Basij commander Gholmhossein Gheibparvar withKhamene’i replaced appointed a new Basij commander, Gholamreza Soleimani, who was sanctioned by the Administration in January2020.2020 and who is not related to the late IRGC-Qf commander Qasem Soleimani. Congressional Research Service 6 Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options The Basij is widely accused of arresting women who violate the regime'’s public dress codes and raiding Western-style partiesin whichthat serve alcohol, which isillegal in Iran, is available. - il egal in Iran.

Law Enforcement Forces. This body is an amalgam of regular police,

gendarmerie, and riot police that serve throughout the country.

It is the regime's first "line of defense" in suppressing generally smallerThese forces general y implement the regime’s initial response to non-violent demonstrations or unrest. -

Ministry of Interior. The ministry exercises civilian supervision of Iran

'’s police and domestic security forces. The IRGC and Basij do not report to the ministry. -

Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS). The MOIS conducts domestic

surveillancesurveil ance to identify regime opponentsand try to penetrate anti-regime cells. It also surveils anti-regime activists abroad through its network of agents placedunderin Iran'’s embassies. It works closely with IRGC-Qods Force agents outside Iran, although the two institutions sometimes differ in their approaches, as has been reportedly the case in deciding on which politicians to support in Iraq.

8

Elected Institutions/Recent Elections

Several major institutional positions are directly elected by the population, but international observers question the credibility of Iran'’s elections because of the role of the COG in vetting candidates and limiting the size and ideological diversity of the candidate field. Women can vote

and run for most offices, but the COG has consistently interpreted the Iranian constitution as prohibiting women from running for president. Candidates must receive more than 50% of the

vote to avoid a runoff that is usuallyusual y held several weeks later.

Another criticism of the political process is the relative absence of political parties. Establishing a party requires the permission of the Interior Ministry (Article 10 of Iran'’s constitution), but the standards to obtain approval are high. Since the regime was founded, numerous groups have filed for permission to operate as parties, but only a few—considered loyal to the regime—have been granted licenses to operate. Some have been licensed and then banned after their leaders opposed

regime policies, such as the Islamic Iran Participation Front and Organization of Mojahedin of the

Islamic Revolution, discussed in the text box below.

The Presidency

The main

The top directly -elected institution is the presidency, which is formallyformal y and in practice subordinate to the Supreme Leader. Virtually every successiveVirtual y every president has tried but failed to expand his

authority relative to the Supreme Leader. Presidential authority, particularly on matters of national security, is also often circumscribed by key clerics and the IRGC. However, the presidency is the most influential economic policymaking position and a source of patronage. The president appoints and supervises the cabinet, develops the budgets of cabinet departments, and imposes and collects taxes on corporations and other bodies. The presidency also runs oversight bodies

such as the Anticorruption Headquarters and the General Inspection Organization, to which government officials are required to submit annual financial disclosures, and it oversees the

various official pension funds and government-run social services agencies.

Prior to 1989, Iran had both an elected president and a prime minister selected by the elected Majles (parliament). However, the holders of the two positions were constantly in institutional 8 “Leaked Iranian intelligence reports illustrate the folly of the US’s Middle East strategy .” T he Strategist, November 20, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

7

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

conflict and a 1989 constitutional revision eliminated the prime ministership. In part because Iran'Iran’s presidents have often sought to expand their authority, Khamene'i has periodically raised ’i has periodical y raised

the possibility of eliminating the post of president and restoring the post of prime minister.

The Majles

Iran'

Iran’s Majles, or parliament, is a 290-seat, allal -elected, unicameral body. There are five "reserved seats" for "recognized"“reserved

seats” for “recognized” minority communities—Jews, Zoroastrians, and Christians (three seats of the fiveJew, Zoroastrian, and Christian (three seats). The Majles votes on each nominee to a cabinet post, and drafts and acts on legislation. Among its main duties is to consider and enact a proposed national budget (which runs from March 21 to March 20 each year, coinciding with Nowruz). It legislates on domestic economic and social issues, and tends to defer to executive and security institutions on defense and foreign policy issues. It is constitutionallyconstitutional y required to ratify major international agreements, and it ratified the

JCPOA in October 2015. The ratification was affirmed by the COG. Women regularly run and some general ysome generally are elected, and there is no "quota"“quota” for the number of women. Majles elections

occur in the year prior to the presidential elections.

The Assembly of Experts

A major but little publicized elected institution is the 88-seat Assembly of Experts. Akin to a

standing electoral college, it is empowered to choose a new Supreme Leader upon the death of the incumbent, and it formally "oversees"formal y “oversees” the work of the Supreme Leader. The Assembly can replace him if necessary, although invoking that power would, in practice, most likely occur only in the event of a severe health crisis. The Assembly is also empowered to draft amendments to the

constitution. It generallygeneral y meets two times a year.

Elections to the Assembly are held every 8-10 years, conducted on a provincial basis. Assembly candidates must be able to interpret Islamic law. In March 2011, the aging compromise candidate Ayatollah Mohammad Reza Mahdavi-Kani was named chairman, but he died in 2014. His

successor, Ayatollah Mohammad Yazdi, lost his seat in the Assembly of Experts election on February 26, 2016 (held concurrently with the Majles elections), and COG Chairman Ayatollah

Ahmad Jannati was appointed concurrently as the assembly chairman in May 2016.

Recent Elections

Following the presidency of regime stalwart Ali Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani during 1989-1997, a reformist, Mohammad Khatemi, won landslide victories in 1997 and 2001. However, hardliners marginalized him by the end of his term in 2005. Aided by widespread voiding of reformist candidacies by the COG, conservatives won a slim majority of the 290 Majles seats in the February 20, 2004, elections. In June 2005, the COG allowedal owed eight candidates to compete (out of the 1,014more than 1,000 who filed candidacies), including Rafsanjani,79 Ali Larijani, IRGC stalwart

Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, and Tehran mayor Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. With reported tacit backing from Khamene'’i, Ahmadinejad advanced to a runoff against Rafsanjani and then won by a 62% to 36% vote. Splits later erupted among hardliners, and pro-Ahmadinejad and pro-Khamene'

Khamene’i candidates competed against each other in the March 2008 Majles elections.

Disputed 2009 Election. Reformists sought to unseat Ahmadinejad in the June 12, 2009, presidential election by rallyingral ying to Mir Hossein Musavi, who served as prime minister during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War and, to a lesser extent, former Majles speaker Mehdi Karrubi. Musavi's generally ’s

9 Rafsanjani was constitutionally permitted to run because a third term would not have been consecutive with his previous two terms. In the 2001 presidential election, the Council permitted 10 out of the 814 registered candidates.

Congressional Research Service

8

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

general y young, urban supporters used social media to organize large ralliesral ies in Tehran, but pro-Ahmadinejad ralliesAhmadinejad ral ies were large as wellwel . Turnout was about 85%. The Interior Ministry pronounced Ahmadinejad the winner (63% of the vote) two hours after the polls closed, prompting Musavi supporters (who was announced as receiving 35% of the vote) to protest the results as fraudulent. But, some outside analysts said the results tracked preelection polls.810 Large antigovernment demonstrations occurred June 13-19, 2009. Security forces killedkil ed over 100

protesters (opposition figure—Iran government figure was 27), including a 19-year-old woman,

Neda Soltani, who became an icon of the uprising.

The opposition congealed into the "“Green Movement of Hope and Change."” Some protests in December 2009 overwhelmed regime security forces in some parts of Tehran, but the movement'movement’s activity declined after the regime successfully suppressed its demonstration on the February 11, 2010, anniversary of the founding of the Islamic Republic. As unrest ebbed, Ahmadinejad Ahmadinejad promoted his loyalists and a nationalist version of Islam that limits clerical authority, bringing him into conflict with Supreme Leader Khamene'’i. Amid that rift, in the

March 2012 Majles elections, candidates supported by Khamene'’i won 75% of the seats, weakening Ahmadinejad. Since leaving office in 2013, and despite being appointed by Khamene'Khamene’i to the Expediency Council, Ahmadinejad has emerged as a regime critic meanwhile

also returning to his prior work as a professor of civil engineering.

10 A paper published by Chatham House and the University of St. Andrews strongly questions how Ahmadinejad’s vote could have been as large as reported by official results, in light of past voting patterns throughout Iran. “Preliminary Analysis of the Voting Figures in Iran’s 2009 Presidential Election,” http://www.chathamhouse.org.uk.

Congressional Research Service

9

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Reformist Leaders and Organizations

The figures discussed below are Mir Hossein Musavi is the titular leader Mehdi Karrubi Mohammad Khatemi Pro-reformist Organizations

National Trust (Etemad-e- Islamic Iran Participation Mojahedin Combatant |

June 2013 Election of Rouhani

Congressional Research Service

10

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

June 2013 Election of Rouhani In the June 14, 2013, presidential elections, held concurrently with municipal elections, the major

candidates included the following:

-

Several hardliners that included Qalibaf (see above); Khamene

'’i foreign policy advisor Velayati;Jalilli. - Jalil i.

Former chief nuclear negotiator Hassan Rouhani, a moderate and Rafsanjani

ally. - al y. The COG denied Rafsanjani

'’s candidacy, which shocked many Iranians because of Rafsanjani'’s prominence, aswellwel as that of an Ahmadinejadally.

al y.

Green Movement supporters, who were first expected to boycott the vote, mobilized behind Rouhani after regime officials stressed that they were committed to a fair election. The vote produced a 70% turnout and a first-round victory for Rouhani, garnering about 50.7% of the 36 million

mil ion votes cast. Hardliners generallygeneral y garnered control of municipal councils in the major cities. Most prominent in Rouhani's first term cabinet were

Foreign Minister:Rouhani’s first term cabinet contained a mixture of hardliners and moderates, including the moderates Mohammad Javad Zarif, a former Ambassador to the United Nations in New York, appointed concurrently as chief nuclear negotiator.Oil Minister: Bijan Zanganeh, who, and Bijan Zanganeh as Oil Minister. Zanganeh served in the same post during the Khatemi presidency andattracted significant foreign investment to the sector. Hereplaced Rostam Qasemi, who was associated with the corporate arm of the IRGC.- The notable hardliners included Defense Minister

:Hosein Dehgan. An, an IRGC stalwart, he was anand early organizer of the IRGC'’s Lebanon contingent that evolved into the IRGC-Qods Force. He also was IRGC Air Force commander and deputy Defense Minister. (He is currently a military advisor to the Supreme Leader.) - Another hardliner was Justice Minister

:Mostafa Pour-Mohammadi. As deputy intelligencewho, as deputy intel igence minister in late 1980s,he was reportedlyreportedly was a decisionmaker in the 1988 mass executions of Iranian prisoners.He was interior minister under Ahmadinejad. In the 115th Congress, H.Res. 188 would have condemned Iran for the massacre.

Congressional Research Service

11

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Dr. Hassan Rouhani

Hassan Rouhani, a Career Background

Often nicknamed the Rouhani Presidency

Rouhani has sought to promote freedom Photograph from http://www.rouhani.ir |

.

Majles and Assembly of Experts Elections in 2016

2016 On February 26, 2016, Iran held concurrent elections for the Majles and for the Assembly of Experts. The CoG approved 6,200 candidatesExperts. A runoff round for 68 Majles seats was held on April 29. For the Majles, 6,200 candidates were approved, including 586 female candidates. Oversight bodies invalidated the candidacies of , and invalidated about 6,000, including all al but 100 reformists. Pro-Rouhani candidates won nearly half the seats,

Congressional Research Service

12

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

and the number of avowed hardliners in the body was reduced significantly. Independents, whose alignments vary by issue, won about 50 seats. Seventeen women were elected—the largest

number since the revolution. The body reelected Ali Larijani Larijani as Speaker.

For the Assembly of Experts election, 161 candidates were approved out of 800 who applied to run. Reformists and pro-Rouhani candidates defeated two prominent hardliners—the incumbent Assembly Chairman Mohammad Yazdi and Ayatollah Mohammad Taqi Mesbah-Yazdi. COG head Ayatollah Jannati retained his seat, but came in last for the 30 seats elected from Tehran Province. He was subsequently named chairman of the body.

Presidential Election

Presidential Election of May 19, 2017

In the latest presidential election on May 19, 2017, Rouhani won a first-round victory with about 57% of the vote. He defeated a major figure, Hojjat ol-Eslam Ibrahim Raisi—a close ally of Khamene'i. Even though other major hardliners had, a close al y of

Khamene’i, even though other hardliners dropped out of the race to improve Raisi's chances, Raisi received only about 38% of the vote.

’s prospects.

Municipal elections were held concurrently. After vetting by local committees established by the Majles, about 260,000 candidates competed for about 127,000 seats nationwide. More than 6% of the candidates were women. The allianceal iance of reformists and moderate-conservatives won control of the municipal councils of Iran'’s largest cities, including all al 21 seats on the Tehran municipal

council. The term of the existing councils expired in September 2017 and a reformist official, Mohammad Ali Najafi, replaced Qalibaf as Tehran mayor. However, Najafi resigned in March 2018 after criticism for his viewing of a dance performance by young girls celebrating a national

holiday. The mayor, as of November 2018, is Pirouz Hanachi.

Second-Term Cabinet

Rouhani was sworn into a second term in early August 2017. His second-

Rouhani’s second term cabinet nominations retained most of the same officials in key posts, including Foreign Minister Zarif. Since the Trump Administration withdrew from the JCPOA in May 2018, hardliners have threatened to try to impeach Zarif for his role in negotiating that accord. In late February 2019, after being excluded from a leadership meeting with visiting President Bashar Al Asad of Syria,

Zarif announced his resignation over the social media application Instagram. Rouhani did not accept the resignation and Zarif resumed his duties.

stayed on. Key changes to the second-term cabinet include the following:

-

Minister of Justice Seyed Alireza Avayee replaced Pour-Mohammadi. Formerly a

state prosecutor, Avayee oversaw trials of protesters in the 2009 uprising and is subject to EU travel ban and asset freeze.

-

Defense Minister Amir Hatami

, a regular military officer,became the first non-IRGC Defense Minister in more than 20 years and the first regular military officer in that position. -

The cabinet has two women vice presidents, and one other woman as a member

of the cabinet (but not heading any ministry).

Upcoming Elections: Majles

Majles Vote on February 21, 2020

The latest Majles elections were held on February 21, 2020 in the context of a balance of power that shifted to hardlinersVote on February 21, 2020

The next national elections will be for the Majles, scheduled for February 21, 2020. The next presidential elections, in which Rouhani will not be eligible to run again, will be in May or June of 2021.

The February 21, 2020, Majles elections might provide indications of the balance of power among Iran's major factions. Many experts assess that momentum shifted toward hardliners in 2019, at least in part as a result of the U.S. policy of exiting the Iran nuclear deal and placing economic pressure on Iran. The outpouring of public grieving for the U.S. killing kil ing

of IRGC-Qods Force commander Qasem Soleimani in January 2020 appeared to support the view that hardliners might have a political advantage in Iran as of the beginning of 2020. Yet, subsequent public anger at the government for initially concealing that it had accidentally shot down a Ukrainian passenger jet might indicate that hardliners will not necessarily prevail in the elections.

In preparations for the Majles elections, during December 1-7, 2019, about 15,000 candidates put their names forward for the 290 seats. However, the COG disqualified nearly half, narrowing the total candidate field to about 9,000 candidates. The COG disqualified 90 incumbents, most of which are professed moderates or reformists, and prompting criticism by Rouhani and others for excessive disqualifications. Among other reformists not allowed to run was Rouhani's son-in-law Kambiz Mehdizadeh.9 Speaker Larijani decided not to seek re-election, as did former speaker Gholam Haddad Adel.

Periodic Unrest Challenges the Regime10

As noted, the regime has faced periodic flare-ups of significant unrest, including several significant episodes in recent months.

suggested that hardliners in

Iran have been ascendant.

During December 2019, about 15,000 candidates filed candidacies for the 290 Majles seats. The COG disqualified nearly half, including 90 incumbents that were mostly professed moderates or reformists. Among the reformists not al owed to run was Rouhani’s son-in-law Kambiz

Congressional Research Service

13

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Mehdizadeh.11 Speaker Larijani decided not to seek re-election, as did former speaker Gholam Haddad Adel. The turnout was about 42%, lower than in most recent Iranian elections, and hardliners won an overwhelming 230 of the 290 seats, including sweeping Tehran’s 30 seats in the body.12 The hardliner victory has set up IRGC stalwart and former Tehran mayor Mohammad

Baqr Qalibaf as the favorite to selected Majles speaker when the body is inaugurated on May 28.

The next presidential elections, in which Rouhani wil not be eligible to run again, is scheduled

for May or June of 2021.

Periodic Unrest Challenges the Regime13

As noted, the regime has faced periodic flare-ups of significant unrest. In December 2017, protests erupted in more than 80 cities, mostly based on economic conditions but reflecting opposition to Iran'’s leadership and the expenditure of resources on interventions throughout the Middle East. Some protesters were apparently motivated by Rouhani'’s 2018-2019 budget proposals to increase funds for cleric-run businesses ("“bonyads"”) and the IRGC. The government

defused the unrest by coupling acknowledgment of the right to protest and the legitimacy of some demonstrator grievances with use of repressive force and a shut downshutdown of access to social media sites such as the messaging system cal ed “Telegram.”14messaging system called "Telegram." Khamene'i at first attributed the unrest to covert action by Iran's foreign adversaries, particularly the United States, but he later acknowledged unspecified "problems" in the administration of justice.11 Iranian official media reported that 25 were killedkil ed and

nearly 4,000 were arrested during that unrest.

During 2018-19, small smal protests and other acts of defiance took place, including shop closures in the Tehran bazaar in July 2018 and protests by some women against the strict public dress code. In addition, workers in various industries, including trucking and teaching, have conducted strikes to demand higher wages to help cope with rising prices. In early 2019, protests took place in

southwestern Iran in response to the government'’s missteps in dealing with the effects of significant flooding in that area. The regime tasked the leadership of the relief efforts to the IRGC and IRGC-QF, working with Iraqi Shia militias who are powerful on the Iraqi side of the border

where the floods took place.

In mid-2018, possibly to try to divert blame for Iran'’s economic situation, the regime established special "“anti-corruption courts"” that have, in some cases, imposed the death penalty on businessmen accused of taking advantage of reimposed sanctions for personal profit.1215 Iran also

has used military action against armed factions that are based or have support outside Iran.

November 2019 Unrest.

Significant unrest flared again on November 15, 2019, in response to a sudden government announcement of a reduction in subsidies for the price of gasoline. Prices rose 50% for amounts up to 15 gallonsgal ons per month, and 300% (to about $1 per gallongal on) for amounts purchased beyond that

amount. The government explained the subsidy reduction as a consensus government decision that was necessary in order to increase cash transfers to the poorest 75% of the population. To counter the protests, the government used a strategy similar to the one it used in 2017: allowingal owed peaceful protests, usingused repression against violent acts, and shuttingshut down access to the internet and social media. As he has done in past periods of unrest, Supreme Leader Khamene'’i blamed the protests on agitation by foreign powers, while 11 US Institute of Peace. Iran Primer. “ Iran’s 2020 Parliamentary Elections.” February 3, 2020. 12 “Factbox: T he outcome of Iran’s 2020 parliamentary elections.” Atlantic Council, February 26, 2020. 13 T he following information is derived from a wide range of press reporting in major newspapers and websites. Some Iranian activist sources report wide variations in protest sizes, cities involved, numbers killed or arrested, and other figures. CRS has no way to corroborate exact numbers cited.

14 National Council of Resistance, “Khamene’i’s Belated Confession to Injustice and Inability to Reform, a Desperate Attempt to Escape Overthrow,” February 19, 2018. 15 Erin Cunningham. “In Iran, Graft Can Lead to the Gallows.” Washington Post, December 1, 2018.

Congressional Research Service

14

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

i blamed the protests on agitation by foreign powers, while also accusing exiled opposition groups of involvement, and threatened a broad crackdown. He also stated that dissatisfaction over the fuel price hikes was "understandable" but he backed the increase as“understandable” but was necessary. On November 20, President 2019, President

Rouhani stated that the regime had achieved "victory"“victory” and had put down the unrest.

In mid-December 2019, based on surveys of persons inside Iran, Amnesty International asserted that over 300 protesters had been killedkil ed by security forces in the unrest, and thousands arrested.13 16 The Iranian government asserted the figure was "“fabricated."” U.S. officials said in January 2020 that, based on a Reuters report that said it had obtained information from security officials inside Iran, security forces had killedkil ed 1,500 protesters in the unrest.14In17In the aftermath of the unrest, the

State Department solicited Iranians to send photos and other information to the State Department

documenting the Iranian crackdown and any other instances of regime human rights abuses.

January 2020 Unrest. Unrest re-emerged briefly in January 2020. Demonstrators took to the

streets in mid-January 2020 after Iran admitted – after several days of concealment – that its military forces had mistakenly shot down a Ukrainian passenger jet in the hours after Iran launched its January 8, 2020, missile strike in Iraq that was retaliation for the U.S. killing of kil ing of IRGC-QF commander Soleimani. All Al 176 passengers, which included 82 Iranians, were killed.

kil ed. There have not been significant incidents of unrest reported to protest the government’s handling

of the COVID-19 outbreak in the winter-spring of 2020, even though many accounts indicate that

the government’s response to the outbreak has been ineffective and lacking in transparency.

The Trump Administration and other senior officials have supported each wave of protests by

warning the regime against using force and expressing solidarity with the protesters. In response to the 2017 unrest, the Administration requested U.N. Security Council meetings to consider Iran'Iran’s crackdown on the unrest, although no formal U.N. action was taken, and sanctioned then-judiciary chief Sadeq Larijani. On November 18, 2019, Secretary of State Pompeo stated, "“The United States is monitoring the ongoing protests closely. We condemn strongly any acts of

violence committed by this regime against the Iranian people and are deeply concerned by reports

of several fatalities. We'’ve been at that since the beginning of this administration."15

In the 115th”18

In the 115th Congress, several resolutions supported Iranian protestors, including H.Res. 676

(passed the House January 9, 2018), S.Res. 367, , H.Res. 675, and S.Res. 368. In the 116th 116th Congress, H.Res. 752 passed the House on January 28, 2020. The resolution, among other provisions: urges the Administration to work to convene emergency sessions of the United Nations Security Council and the United Nations Human Rights Council to condemn the ongoing human rights violations perpetrated by the Iranian regime and establish a mechanism by which

the Security Council can monitor such violations; and encourages the Administration to provide assistance to the Iranian people to have free and uninterrupted access to the internet, including by broadening General License D–1 (which allowsal ows for the exportation to Iran of equipment that

citizens can use to circumvent regime censorship of the Internet).

16“'Vicious crackdown': Iran protest death toll at 304, Amnesty says.” December 17, 2019. 17 “US Confirms Report Citing Iran Officials as Saying 1,500 Killed in Protests.” Voice of America. December 23, 2019. 18 Department of State. “Press Briefing by Secretary Pompeo.” November 18, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

15

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Demographics/Ethnic and Religious Minorities

General. Iran’

Azeris. Azeris, Christians. Christians, who number about 300,000, are a "protected minority" with three seats reserved in the Majles. The majority of Christians in Iran are ethnic Armenians, with Assyrian Christians contributing about 10,000-20,000 practitioners. The IRGC scrutinizes churches and Christian religious practice, and numerous Christians remain incarcerated for actions related to religious practice, including using wine in services. At times, there have been unexplained assassinations of pastors in Iran, as well as prosecutions for converting from Islam to Christianity and for proselytizing. One Pastor, Yousef Nadarkhani, has been repeatedly arrested. Kurds. Arabs. Ethnic Arabs are prominent in southwestern Iran, particularly Khuzestan Province, Baluchis. Iran has about 1.4

Sufis. In February 2018, Iran arrested 300 Sufis demanding the release |

Human Rights Practices16

” Sources: Various press reports, U.N. reports, and human rights organization reports.

Congressional Research Service

16

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Human Rights Practices19 U.S. State Department reports and reports from a U.N. Special Rapporteur have long cited Iran for a wide range of abuses—aside from its suppression of political opposition and use of force against protesters—including escalating. Such abuses include: use of capital punishment, executions of minors, denial of fair public trial, harsh and life-threatening conditions in prison, and unlawful detention and torture. Many of these abuses have been reported to be practices among Iran’s regional neighbors

as wel . torture. Other than the release of U.S. and dual-nationals held, curtailing Iran'’s human rights

abuses has not been named as a U.S. condition for improved relations.

State Department and U.N. Special Rapporteur reports have noted that the 2013 revisions to the

Islamic Penal Code and the 2015 revisions to the Criminal Procedure Code made some reforms, including eliminating death sentences for children convicted of drug-related offenses and protecting the rights of the accused. A "Citizen'“Citizen’s Rights Charter,"” issued December 19, 2016, at least nominallynominal y protects free expression and is intended to raise public awareness of citizen rights. It also purportedly commits the government to implement the charter's 120 articles. In August 2017, Rouhani appointed a woman, former vice president Shahindokht Molaverdi, to oversee implementation of the charter. The State Department's human rights report for 2018 says’s 120 articles. The State

Department’s recent human rights reports say that key charter protections for individual rights of

freedom to communicate and access information have not been implemented.

A U.N. Special Rapporteur on Iran human rights was reestablished in March 2011 by the U.N.

Human Rights Council (22 to 7 vote), resuming work done by a Special Rapporteur on Iran human rights during 1988-2002. The rapporteur appointed in 2016, Asma Jahangir, issued two Iran reports, the latest of which was dated August 14, 2017 (A/72/322), before passing away in February 2018. The Special Rapporteur mandate was extended on March 24, 2018, and British-Pakistani lawyer Javaid Rehman was appointed in July 2018. The U.N. General Assembly has

insisted that Iran cooperate by allowingal owing the Special Rapporteur to visit Iran, but Iran has instead

only responded to Special Rapporteur inquiries through agreed "“special procedures."

”

Despite the criticism of its human rights record, on April 29, 2010, Iran acceded to the U.N.

Commission on the Status of Women. It also sits on the boards of the U.N. Development Program

(UNDP) and UNICEF. Iran'’s U.N. dues are about $9 millionmil ion per year.

19 Much of the information in this section comes from the State Department Country Report on Human Rights for 2019; Iran.

Congressional Research Service

17

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Women’ per year.

Women's Rights

Women Women 20 In recent years, |

Iran has an official body, the High Council for Human Rights, headed by former Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Larijani (brother of the Majles speaker and the judiciary head). It generally). It general y defends the government's ’s

actions to outside bodies rather than oversees the government'’s human rights practices, but Larijani, according to the Special Rapporteur, has questioned the effectiveness of drug-related

executions and other government policies.

As part of its efforts to try to compel Iran to improve its human rights practices, the United States has imposed sanctions on Iranian officials allegedal eged to have committed human rights abuses, and on firms that help Iranian authorities censor or monitor the internet. Human rights-related sanctions

are analyzed in significant detail in CRS Report RS20871, Iran Sanctions, by Kenneth Katzman.

|

Media Freedoms |

|

|

Labor Restrictions |

for Iranians.

Labor Restrictions

Independent unions are legal but are restricted in practice. Many trade unionists remain in jail |

|

Religious Freedom |

Religious Freedom

Each year since 1999, the Secretary of State has designated Iran as a |

|

Executions Policy |

|

|

Human Trafficking |

Human Trafficking

Since 2005, State Department |

|

Corporal Punishments/Stoning |

|

Sources: Most recent State Department reports on human rights practices, on international religious freedom, and trafficking in persons.

and trafficking in persons. Trafficking in persons report for 2019, report on Iran: https://www.state.gov/reports/2019-trafficking-in-persons-report-2/iran/.

U.S.-Iran Relations, U.S. Policy, and Options

The February 11, 1979, fall fal of the Shah of Iran, who was a key U.S. ally, shattered led to a dissolution of U.S.-Iran relations. The Carter Administration'’s efforts to build a relationship with the new regime in Iran ended after the

November 4, 1979, takeover of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran by radical pro-Khomeini "“Students in the Line of the Imam."” The 66 U.S. diplomats there were held hostage for 444 days, and released

Congressional Research Service

19

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

pursuant to the January 20, 1981, Algiers Accords. Their release was completed minutes after President Reagan'’s inauguration on January 20, 1981.18The21The United States broke diplomatic relations with Iran on April 7, 1980, two weeks before the failed U.S. military attempt to rescue

the hostages ("“Desert One").

”).

Iran has since pursued policies that every successive U.S. Administration has considered inimical to U.S. interests in the Near East region and beyond.1922 Iran'’s authoritarian political system and

human rights abuses have contributed to the U.S.-Iran rift.

The two countries have minimal official direct contact. Iran has an interest section in Washington, D.C., under the auspices of the Embassy of Pakistan, and staffed by Iranian Americans. The former Iranian Embassy closed in April 1980 when the two countries broke diplomatic relations, and remains under the control of the State Department. Iran'’s Mission to the United Nations in

New York runs most of Iran'’s diplomacy inside the United States. The U.S. interests section in Tehran, under the auspices of the Embassy of Switzerland, has no American personnel. In 2014, Iran appointed one of those involved in the 1979 seizure of the U.S. embassy in Tehran—Hamid Aboutalebi—as ambassador to the United Nations. In April 2014, Congress enacted P.L. 113-100, authorizing the Administration to deny him a visa, and U.S. officials announced that he would not be admitted. In May 2015, the two governments granted each other permission to move their respective interests sections to more spacious locations. As ofSince April 2019, Iran'’s Ambassador to the United Nations ishas been Majid Takht Ravanchi. U.S. officials and U.S. government employees, including

Members of Congress and staff, generallygeneral y are not granted visas by Iran to visit.

The following sections analyze some key hallmarkshal marks of past U.S. policies toward Iran.

Reagan Administration: Iran Placed on "“Terrorism List"

” The Reagan Administration designated Iran a "“state sponsor of terrorism" in January 1984, under Section 6(j) of the Export Administration Act which established that "terrorism list" in 1979, ” in January 1984, largely in response to Iran'’s backing for the October 1983 bombing of the Marine Barracks in

Beirut.23 The Administration also "tilted"“tilted” toward Iraq in the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War.2024 During 1987-1988, at the height of that war, U.S. naval forces fought several skirmishes with Iranian naval elements while protecting oil shipments transiting the Persian Gulf from Iranian mines and other attacks. On April 18, 1988, Iran lost one-quarter of its larger naval ships in an engagement with the U.S. Navy ("“Operation Praying Mantis"”), including a frigate sunk. However, in 1986, the Administration

Administration provided some arms to Iran ("TOW"“TOW” anti-tank weapons and I-Hawk air defense batteries) in exchange for Iran'’s help in the releasing of U.S. hostages held by pro-Iranian Hezbollah Hezbollah in Lebanon ("“Iran-Contra Affair"”). On July 3, 1988, U.S. forces in the Gulf mistakenly shot down Iran Air Flight 655 over the Gulf, killing all kil ing al 290 on board, almost all al of whom were Iranian nationals, contributing to Iran'’s decision to accept U.N. Security Council Resolution 598

that provided for a cease-fire with Iraq in August 1988.

George H. W. Bush Administration: "“Goodwill Begets Goodwill"

” The George H.W. Bush Administration appeared to hold out prospects for improved U.S.-Iran relations. In his January 1989 inauguration speech, President George H.W. Bush, stated that "goodwill begets goodwill"“goodwil begets goodwil ” with respect to Iran, reportedly implying that U.S.-Iran relations could improve if Iran helped obtain the release of remaining U.S. hostages held by Hezbollah in Lebanon. Iran's apparent assistance led to the release of all in

21 T he text of the Algiers Accords can be found at https://www.nytimes.com/1981/01/20/world/text-of-agreement-between-iran-and-the-us-to-resolve-the-hostage-situation.html. T he technical name of the Accords was: “ T he Declaration of the Government of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria,” reflecting that it was a result of a request by Iran and the United States for Algerian mediation of the hostage crisis.

22 T hose policies are assessed in CRS Report R44017, Iran’s Foreign and Defense Policies, by Kenneth Katzman. 23 T he terrorism list was established in 1979 under Section 6(j) of the Export Administration Act . 24 Elaine Sciolino, The Outlaw State: Saddam Hussein’s Quest for Power and the Gulf Crisis (1991), p. 168.

Congressional Research Service

20

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

Lebanon. Iran’s apparent assistance led to the release of al remaining U.S. hostages by the end of 1991. No1991. However, no U.S.-Iran thaw followed, possibly because Iran continued to back violent groups opposed to the U.S.Administration’s push for Arab-Israeli peace that followed the 1991 U.S. liberation of Kuwait.

Clinton Administration: "Dual Containment"

. Iran benefited strategical y from the Bush Administration’s 1991 defeat of the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait, and pro-Iranian groups launched a significant but ultimately unsuccessful uprising against Saddam

Hussein’s regime in the aftermath of that war.

Clinton Administration: “Dual Containment” The Clinton Administration articulated a strategy of "“dual containment"” of Iran and Iraq—an attempt to keep both countries simultaneously weak rather than alternately tilting to one or the other. In25 As part of that policy, in 1995-1996, the Administration and Congress banned U.S. trade and investment with Iran and imposed penalties on foreign investment in Iran'’s energy sector, in response to Iran'’s support for terrorist groups seeking to undermine the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. The election of the moderate Mohammad Khatemi as president in May 1997 precipitated

a U.S. offer of direct dialogue, but no direct dialogue ensued. InKhatemi, possibly under pressure from Iran’s hardliner refused to enter into direct talks. As part of the unsuccessful attempt to reach out to Khatemi’s government, in June 1998, then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright calledcal ed for mutual confidence building measures that could lead to a "“road map"” for normalization. In a March 17,

2000, speech, Secretary Albright admitted past U.S. interference in Iran.

George W. Bush Administration: Iran Part of "“Axis of Evil"

” In his January 2002 State of the Union message, President Bush named Iran as part of an "“axis of evil"

evil” including Iraq and North Korea.26 However, the Administration enlisted Iran'’s diplomatic help in efforts to try to stabilize post-Taliban Afghanistan and post-Saddam Iraq.2127 The Administration rebuffed a reported May 2003 Iranian overture, transmitted by the Swiss Ambassador to Iran, for an agreement on all al major issues of mutual concern ("“grand bargain" proposal).22” proposal).28 State Department officials disputed that the proposal was fully vetted within Iran's ’s

leadership. The Administration aided victims of the December 2003 earthquake in Bam, Iran,

including through U.S. military deliveries into Iran.

As Iran'’s nuclear program advanced, the Administration worked with several European countries to persuade Iran to agree to limit its nuclear program. President Bush'’s January 20, 2005, second inaugural address and his January 31, 2006, State of the Union message stated that the United States would be a close allyal y of a "“free and democratic"” Iran—phrasing that suggested support for

regime change.23

29 Obama Administration: Pressure, Engagement, and the JCPOA

President Obama asserted that there was an opportunity to persuade Iran to limit its nuclear

program through diplomacy and to potentially rebuild a U.S.-Iran relationship after decades of mutual animositypotential y improve U.S.-Iran relations more broadly. The approach emerged in President Obama'’s first message to the Iranian people on the occasion of 25 Speech by NSC Senior Director for Near Eastern Affairs Martin Indyk, to the Soref Symposium of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “ T he Clinton Administration's Approach to the Middle East .” 1993. 26 T ext of President Bush's 2002 State of the Union Address. Washington Post, January 29, 2002. 27 Robin Wright, “U.S. In ‘Useful’ T alks with Iran,” Los Angeles Times, May 13, 2003. 28 “Bush T eam Snubbed `Grand Bargain' on Iran's Atomic Work in 2003 .” Bloomberg, December 10, 2007. 29 “Strategy on Iran Stirs New Debate at White House,” New York Times, June 16, 2007.

Congressional Research Service

21

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

s first message to the Iranian people on the occasion of Nowruz (Persian New Year, March 21, 2009), in which he stated that the United States "“is now committed to diplomacy that addresses the full range of issues before us, and to pursuing constructive ties among the United States, Iran, and the international community."”30 He referred to Iran as "“The Islamic Republic of Iran,"” appearing to reject a policy of regime change. The Administration reportedly also loosened restrictions on U.S. diplomats'’ meeting with their Iranian counterparts at international meetings. President Obama said that he exchanged several letters

with Supreme Leader Khamene'’i, expressing U.S. support for engaging Iran.

an intent to engage Iran.

In 2009, Iran'’s crackdown on the Green Movement uprising and its refusal to immediately accept

limits on its nuclear program contributed to an Administration shift to a "“two track"” strategy: stronger economic pressure coupled with offers of nuclear negotiations that would entail sanctions relief. The sanctions imposed sanctions relief if Iran accepted nuclear program limitations. International sanctions imposed on Iran during 2010-2013 received broad international cooperation and caused significant economic difficulty in Iran. In early 2013, the Administration began direct but unpublicized talks with Iranian officials in the Sultanate of Oman on a nuclear accord.2431 Apparently seeking to capitalize on the election of Rouhani in June 2013,

President Obama'’s September 24, 2013, U.N. General Assembly speech confirmed an exchange of letters with Rouhani stating U.S. willingnesswil ingness to resolve the nuclear issue peacefully and that the United States "“[is] not seeking regime change."25”32 The two presidents spoke by phone on

September 27, 2013—the first U.S.-Iran contact at that level since Iran'’s revolution.

After the JCPOA was finalized in July 2015, the United States and Iran held bilateral meetings at the margins of all al nuclear talks and in other settings, covering bilateral issues. President Obama expressed hope that the JCPOA would "“usher[] in a new era in U.S.-Iranian relations,"26”33 while at the same time asserting that the JCPOA benefitted U.S. national security even if there were no broader rapprochement. President Obama met Foreign Minister Zarif at the September 2015 General Assembly session. Stillon its own merits. Stil , a

, a broad warming of U.S.-Iran relations was elusive.

-

Coinciding with Implementation Day of the JCPOA (January 16, 2016), dual

Iranian-American citizens held by Iran were released and a long-standing Iranian claim for funds paid for undelivered military equipment from the Shah

'’s era was settled—resulting in $1.7billionbil ion in cash payments (euros, Swiss francs, and other non-U.S. hard currencies) to Iran—$400millionmil ion for the original DOD monies and $1.3billionbil ion for an arbitrated amount of interest. Administration officials asserted that the nuclear diplomacy provided an opportunity to resolve these outstanding issues, but some Members of Congress criticized the simultaneity of the financial settlement as paying"ransom"“ransom” to Iran. Obama Administration officials asserted that ithadwas longbeenassumed that the United Stateswould need to return monies to Iranwas liable for the Iranian funds paid for the undelivered military equipment and that the amount of interest agreed was likely less than what Iran might have been awarded by the U.S.-Iran Claims Tribunal. Iran subsequently jailed several other dual nationals (see box below). - Iran continued to provide support to allies and proxies in the region, and it continued "high speed intercepts" of U.S. warships in the Persian Gulf. Iran conducted at least four ballistic missile tests from the time the JCPOA was finalized in 2015 until the end of the Obama Administration, which termed the tests "defiant of" or "inconsistent with" Resolution 2231.

-

Iran did not discontinue any of its support to al ies and proxies in the region, its

chal enges to U.S. warships in the Persian Gulf, or its bal istic missile tests.

Iranian arms exports were banned by Resolution 2231 that endorsed the JCPOA, and the Resolution cal ed on Iran not to develop missiles capable of carrying a nuclear payload. The Obama Administration termed the missile tests “defiant of” or “inconsistent with” Resolution 2231.

30 “Barack Obama offers Iran 'new beginning' with video message.” The Guardian, March 20, 2009. 31 “Inside the secret US-Iran diplomacy that sealed nuke deal.” Al Monitor, August 11, 2015. 32 Remarks by President Obama in Address to the United Nations General Assembly, September 24, 2013. 33 Roger Cohen. “U.S. Embassy, T ehran.” New York Times, April 8, 2015.

Congressional Research Service

22

Iran: Internal Politics and U.S. Policy and Options

There was no expansion of diplomatic representation, such as the posting of U.S.

There was no expansion of diplomatic representation, such as the posting of U.S.nationals to staff the U.S. interests section in Tehran, nor did then-Secretary of State Kerry visit Iran. However, in January 2016, Kerry worked with Zarif to achieve the rapid release of 10 U.S. Navy personnel who the IRGC took into custody when their two riverine crafts strayed into what Iran considers its territorial waters. -

Iranian officials argued that new U.S. visa requirements in the FY2016

Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 114-113) would cause European businessmen to hesitate to travel to Iran and thereby limit Iran

'’s economic reintegration. Then-Secretary of State Kerry wrote to Foreign Minister Zarif on December 19, 2015, that the United States would implement the provision so as to avoid interfering with"“legitimate business interests of Iran."

”

Trump Administration: JCPOA Exit and "“Maximum Pressure"

” The Trump Administration shifted U.S. policy sharply from that of its predecessor by abrogating the JCPOA and applying "“maximum pressure,"” through U.S. sanctions on Iran'’s economy, to: (1) compel it to renegotiate the JCPOA to address the broad range of U.S. concerns and (2) deny Iran