Iran Sanctions

Changes from January 24, 2020 to April 14, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Overview

and Objectives - Blocked Iranian Property and Assets

- Executive Order 13599 Impounding Iran-Owned Assets

- Sanctions for Iran's Support for Armed Factions and Terrorist Groups

- Sanctions Triggered by Terrorism List Designation

- Exception for U.S. Humanitarian Aid

- Sanctions on States "Not Cooperating" Against Terrorism

- Executive Order 13224 Sanctioning Terrorism-Supporting Entities

- Use of the Order to Target Iranian Arms Exports

- Application of CAATSA to the Revolutionary Guard

- Implementation of E.O. 13224

- Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) Designations

- Other Sanctions on Iran's "Malign" Regional Activities

- Executive Order 13438 on Threats to Iraq's Stability

- Executive Order 13572 on Repression of the Syrian People.

- The Hizballah International Financing Prevention Act (P.L. 114-102) and Hizballah International Financing Prevention Amendments Act of 2018 (

S. 1595,P.L. 115-272). - Ban on U.S. Trade and Investment with Iran

- JCPOA-Related Easing and Subsequent Reversal

- What U.S.-Iran Trade Is Allowed or Prohibited?

- Application to Foreign Subsidiaries of U.S. Firms

- Sanctions on Iran's Energy Sector

- The Iran Sanctions Act

- Key Sanctions "Triggers" Under ISA

- Mandate and Time Frame to Investigate ISA Violations

- Interpretations of ISA and Related Laws

- Implementation of Energy-Related Iran Sanctions

- Iran Oil Export

ReductionSanctions: Section 1245 of the FY2012 NDAA Sanctioning Transactions with Iran's Central Bank - Implementation/SREs Issued and Ended

- Waiver and Termination

Iran Foreign Account "Restriction" Provision- Sanctions on Weapons of Mass Destruction, Missiles, and Conventional Arms Transfers

- Iran-Iraq Arms Nonproliferation Act and Iraq Sanctions Act

- Implementation

- Waiver

Banning Aid to Countries that Aid or Arm Terrorism List States: Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996- Implementation

- Proliferation-Related Provision of the Iran Sanctions Act

- Iran-North Korea-Syria Nonproliferation Act

- Implementation

- Waiver and Termination

Executive Order 13382 on Proliferation-Supporting Entities- Implementation

- Arms Transfer and Missile Sanctions: The Countering America's Adversaries through Sanctions Act (CAATSA, P.L. 115-44)

- Implementation

- Foreign Aid Restrictions for Named Suppliers of Iran

- Sanctions on "Countries of Diversion Concern"

- Implementation

- Waiver and Termination

- Financial/Banking Sanctions

- Targeted Financial Measures

- Ban on Iranian Access to the U.S. Financial System/Use of Dollars

- Punishments/Fines Implemented against Some Banks.

- CISADA: Sanctioning Foreign Banks That Conduct Transactions with Sanctioned Iranian Entities

- Implementation

- Waiver and Termination

Iran Designated a Money-Laundering Jurisdiction/FATF- FATF

- Use of the SWIFT System

- Sanctions on Iran's Non-Oil Industries and Sectors

- The Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act (IFCA)

- Implementation

- Waiver and Termination

Executive Order 13645/13846: Iran's Automotive Sector, Rial Trading, and Precious Stones- Executive Order 13871 on Iran's Minerals and Metals Sectors (May 8, 2019)

- Executive Order 13902 on the Construction, Mining, Manufacturing, and Textiles Sector (January 10. 2020)

- Executive Order 13608 on Sanctions Evasion

- Sanctions on Cyber and Criminal Activities

- Executive Order 13694

- Executive Order 13581

- Implementation of E.O. 13694 and 13581

- Divestment/State-Level Sanctions

- Sanctions Supporting Democracy/Human Rights

- Expanding Internet and Communications Freedoms

- Countering Censorship of the Internet: CISADA, E.O. 13606, and E.O. 13628

- Laws and Actions to Promote Internet Communications by Iranians

- Measures to Sanction Human Rights Abuses/Promote Civil Society

- Non-Iran Specific Human Rights Laws

- Sanctions on Iran's Leadership

- Executive Order 13876

- U.N. Sanctions

- Resolution 2231 and U.N. Sanctions Eased

- Sanctions Application under Nuclear Agreements

- Sanctions Eased by the JPA

- Sanctions Easing under the JCPOA and U.S. Reimposition

- U.S. Laws and Executive Orders Affected by the JCPOA

- U.S. Sanctions that Remained in Place despite the JCPOA

- International Implementation and Compliance

- European Union (EU)

- EU Divestment in Concert with Reimposition of U.S. Sanctions

- European Special Purpose Vehicle/INSTEX and Credit Line Proposal

- EU Antiterrorism and Anti-proliferation Actions

- SWIFT Electronic Payments System

- China and Russia

- Russia

- China

- Japan/Korean Peninsula/Other East Asia

- North Korea

- Taiwan and Singapore

- South Asia

- India

- Pakistan

- Turkey/South Caucasus

- Turkey

- Caucasus and Caspian Sea

- Persian Gulf States and Iraq

- Iraq

- Syria and Lebanon

- International Financial Institutions/World Bank/IMF

World Bankand WTO - WTO Accession

- Effectiveness of Sanctions

- Effect on Iran's Nuclear Program and Strategic Capabilities

- Effects on Iran's Regional Influence

- Internal Political Effects

- Economic Effects

- Iran's Economic Coping Strategies

- Effect on Energy Sector Development

- Human Rights-Related Effects

- Humanitarian Effects

- U.S. COVID Response

Air SafetyPost-JCPOARecent Sanctions Legislation- Key Legislation in the 114th Congress

- Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act (P.L. 114-17)

- Visa Restriction

- Iran Sanctions Act Extension

- Reporting Requirement on Iran Missile Launches

Other114th Congress Legislation not Enacted

- The Trump Administration and Major Iran Sanctions Legislation

- The Countering America's Adversaries through Sanctions Act of 2017 (CAATSA, P.L. 115-44)

- Legislation in the 115th Congress Not Enacted

- 116th Congress

- Other Possible U.S. and International Sanctions

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Iran Crude Oil Sales

- Table 2. Major Settlements/Fines Paid by Banks for Violations

- Table 3. Summary of Provisions of U.N. Resolutions on Iran Nuclear Program (1737, 1747, 1803, 1929, and 2231)

- Table

A-1. Comparison Between U.S., U.N., and EU and Allied Country Sanctions (Prior to Implementation Day) - Table B-1. Post-1999 Major Investments in Iran's Energy Sector

- Table C-1. Entities Sanctioned Under U.N. Resolutions and EU Decisions

TableD-1. Entities Designated Under U.S. Executive Order 13382 (Proliferation)- Table D-2. Iran-Related Entities Sanctioned Under Executive Order 13224 (Terrorism Entities)

- Table D-3. Determinations and Sanctions under the Iran Sanctions Act

- Table D-4. Entities Sanctioned Under the Iran North Korea Syria Nonproliferation Act or Executive Order 12938 for Iran-Specific Violations

- Table D-5. Entities Designated under the Iran-Iraq Arms Non-Proliferation Act of 1992

- Table D-6. Entities Designated as Threats to Iraqi Stability under Executive Order 13438 (July 17, 2007)

- Table D-7. Iranians Designated Under Executive Order 13553 on Human Rights Abusers (September 29, 2010)

- Table D-8. Iranian Entities Sanctioned Under Executive Order 13572 for Repression of the Syrian People (April 29, 2011)

- Table D-9. Iranian Entities Sanctioned Under Executive Order 13606 (GHRAVITY, April 23, 2012))

- Table D-10. Entities Sanctioned Under Executive Order 13608 Targeting Sanctions Evaders (May 1, 2012)

- Table D-11. Entities Named as Iranian Government Entities Under Executive Order 13599 (February 5, 2012)

- Table D-12. Entities Sanctioned Under Executive Order 13622 for Oil and Petrochemical Purchases from Iran and Precious Metal Transactions with Iran (July 30, 2012)

- Table D-13. Entities Sanctioned under the Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act (IFCA, P.L. 112-239)

- Table D-14. Entities Designated as Human Rights Abusers or Limiting Free Expression under Executive Order 13628 (October 9, 2012, E.O pursuant to Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act)

- Table D-15. Entities Designated under E.O. I3645 on Auto production, Rial Trading, Precious Stones, and Support to NITC (June 3, 2013)

- Table D-16. Entities Designated under Executive Order 13581 on Transnational Criminal Organizations (July 24, 2011)

- Table D-17. Entities Designated under Executive Order 13694 on Malicious Cyber Activities (April 1, 2015)

- Table D-18. Entities Designated under Executive Order 13846 Reimposing Sanctions (August 6, 2018)

- Table D-19. Executive Order 13871 on Metals and Minerals (May 8, 2019)

- Table D-20. Entities Designated as Gross Human Rights Violators under Section 7031(c) of Foreign Aid Appropriations

- Table D-21. Entities Designated under E.O. 13876 on the Supreme Leader and his Office (June 24, 2019)

- Table D-22. Executive Order 13818 Implementing the Global Magnitsky Act (December 20, 2017)

Summary

Successive Administrations have used economic sanctions to try to change Iran's behavior. U.S. sanctions, including on Iran, which are primarily "secondary sanctions" on firms that conduct certain transactions with Iran, have adversely affected Iran's economy but have had little observable effect on. The sanctions arguably have not, to date, altered Iran's pursuit of core strategic objectives such asincluding its support for regional armed factions and its development of ballistic and cruise missiles.

During 2012-2015, when the global community was relatively united in pressuring Iran economically, missiles. Arguably, sanctions did contribute to Iran's decision to enter into a 2015 agreement that put limits on its nuclear program.

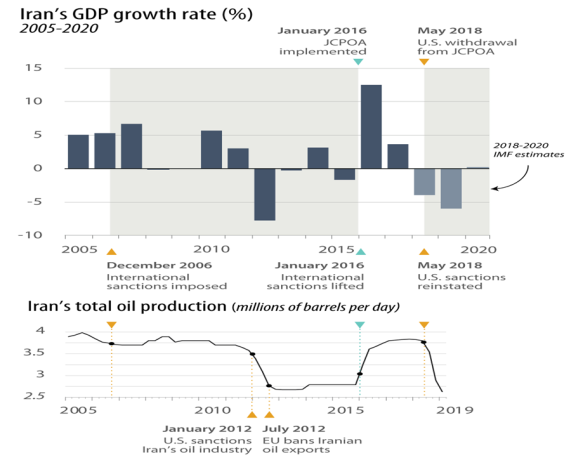

During 2011-2015, the global community pressured Iran economically, and Iran's economy shrank as its crude oil exports fell by more than 50%, and Iran had limited access to its $120 billion inwas rendered unable to access its foreign exchange assets abroad. Iran accepted the 2015 multilateral nuclear accord (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA) in part because it brought broad relief through the waiving of relevant sanctions, revocation of relevant executive orders (E.O.s), and the lifting of U.N. and EU sanctions. Remaining in place were a U.S. sanctions onthe agreement brought broad sanctions relief. The Obama Administration waived relevant sanctions and revoked relevant executive orders (E.O.s). United Nations and European Union sanctions were lifted as well. Remaining in place were U.S. sanctions on: U.S. trade with Iran, Iran's support for regional governments and armed factions, its human rights abuses, its efforts to acquire missile and advanced conventional weapons capabilitiestechnology, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Under U.N. Security Council Resolution 2231, which enshrined the JCPOA, there were nonbinding U.N. restrictionsendorsed the JCPOA, provided for a non-binding restriction on Iran's development of nuclear-capable ballistic missiles and a bindingkept in place an existing ban on its importation or exportation of arms remained in place. The later. The latter ban expires on October 18, 2020. The sanctions relief enabled Iran to increase its oil exports to nearly pre-sanctions levels, regain access to its foreign exchange reserve funds and reintegrate into the international financial system, achieve about 7% yearly economic growth (2016-2017), attract foreign investment, and buy new passenger aircraft.

Sanctions arefunds, and order some new passenger aircraft.

On May 8, 2018, President Trump announced that the United States would no longer participate in the JCPOA. All U.S. secondary sanctions were re-imposed as of November 6, 2018. Sanctions have since been at the core of Trump Administration policy to apply "maximum pressure" on Iran, with the stated purpose of compelling Iran to negotiate a revised JCPOA that takes into account the broad range of U.S. concerns about Iran. On May 8, 2018, President Trump announced that the United States would no longer participate in the JCPOA and all U.S. secondary sanctions were reimposed as of November 6, 2018. The effect of the reinstatement has been to drive Iran's economy into severe recession as major companies have exited the Iranian economy. Iran's oil exports have decreased dramatically—beyond Iran's nuclear program. The policy has caused major companies to exit the Iran market, and Iran's economy fell into severe recession. Iran's oil exports decreased dramatically, particularly after the Administration in May 2019 ended sanctions exceptions for the purchase of Iranian oil—and the value of Iran's currency has declined sharply. Since the summer of 2019, the Administration has sanctioned numerous entities that are supporting Iran's remaining oil trade, added sanctions on Iran's Central Bank, and sanctioned several senior Iranian officials. In 2019, the Administration ended several of the waivers under which foreign governments provided technical assistance to some JCPOA-permitted aspects of Iran's nuclear program. The Administration has also sanctioned several senior Iranian officials. Iran has continued to develop its missile force and to provide arms and support to a broad array of armed factions operating throughout the region, while refusing, to date, to begin talks with the United States on a revised JCPOA.

The European Union and other countries have sought to keep the economic benefits of the JCPOA flowing to Iran in order to persuade Iran to remain in the nuclear accord. In Januaryearly 2019, the European countries created a trading mechanism (Special Purpose Vehicle) that circumvents U.S. secondary sanctions, and the EU countries are contemplating providing Iran with $15 billion in credits, secured by future oil deliveries, to facilitate the use of that mechanism. However, the vehicle has not succeeded, to date, in its economic objectives, and Iran has responded by decreasing its compliance with some of the nuclear commitments of the JCPOA and by conducting provocations in the Persian Gulf. Iran has, to date, refused to begin talks with the United States on a revised JCPOAmechanism to facilitate trade with Iran but the vehicle only completed one transaction in its first year of operations. Since mid-2019, Iran has responded to the increasing sanctions by decreasing its compliance with some of the nuclear commitments of the JCPOA and by conducting provocations in the Persian Gulf and in Iraq.

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted international criticism that U.S. sanctions on Iran might be hindering Iran's response to the outbreak. Iran has reported more cases and more deaths from the illness than any other country in the region. Numerous accounts indicate that sanctions have hindered Iran's ability to finance the purchase of medical equipment, even though U.S. sanctions do not apply to humanitarian transactions. In March 2020, the Administration revised public sanctions guidance to prompt foreign companies to proceed with sales of humanitarian items to Iran. The Administration has also offered assistance to help Iran deal with COVID-19, but Iran has refused the U.S. aid. Iran has applied to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a $5 billion loan.

See also CRS Report R43333, Iran Nuclear Agreement and U.S. Exit, by Paul K. Kerr and Kenneth Katzman; and CRS Report R43311, Iran: U.S. Economic Sanctions and the Authority to Lift Restrictions, by Dianne E. Rennack.

Overview and Objectives

Sanctions have been a significant component of U.S. Iran policy since Iran's 1979 Islamic Revolution that toppled the Shah of Iran, a U.S. ally. In the 1980s and 1990s, U.S. sanctions were intended to try to compel Iran to cease supporting acts of terrorism and to limit Iran's strategic power in the Middle East more generally. After the mid-2000s, U.S. and international sanctions focused largely on ensuring that Iran's nuclear program is for purely civilian uses. During 2010-2015, the international community cooperated closely with a U.S.-led and U.N.-authorized sanctions regime in pursuit of the goal of persuadingtrying to persuade Iran to agree to limits to its nuclear program. Still, sanctions against Iran havehave had multiple objectives and sought to address multiple perceived threats from Iran simultaneously.

This report analyzes U.S. and international sanctions against Iran. CRS has no way tocannot independently corroborate whether any individual or other entity might be in violation of U.S. or international sanctions against Iran. The report tracks implementation of the various U.S. laws and executive orders. Some sanctions, some of which require the blocking of U.S.-based property of sanctioned entities, but no. No information has been released from the executive branch indicating the extent, if any, to which any such property has beenis currently blocked.

The sections below are grouped by function, in the chronological order in which these themes have emerged.1

Blocked Iranian Property and Assets

Post-JCPOA Status: Iranian Assets Still Frozen, but Some Issues Resolved

U.S. sanctions on Iran were first imposed during the U.S.-Iran hostage crisis of 1979-1981, in the form of executive orders issued by President Jimmy Carter blocking nearly all Iranian assets held in the United States. These included E.O. 12170 of November 14, 1979, blocking all Iranian government property in the United States, and E.O 12205 (April 7, 1980) and E.O. 12211 (April 17, 1980) banning virtually all U.S. trade with Iran. The latter two orders were issued just prior to the failed April 24-25, 1980, U.S. effort to rescue the U.S. Embassy hostages held by Iran. President Jimmy Carter also broke diplomatic relations with Iran on April 7, 1980. The trade-related orders (12205 and 12211) were revoked by Executive Order 12282 of January 19, 1981, following the "Algiers Accords" (hereafter: "Accords") that resolved the U.S.-Iran hostage crisis. Iranian assets still frozen are analyzed below.

U.S.-Iran Claims Tribunal

The Accords established a "U.S.-Iran Claims Tribunal" at the Hague that continues to arbitrate government-to-government cases resulting from the 1980 break in relations and freezing of some of Iran's assets. All of the 4,700 private U.S. claims against Iran were resolved in the first 20 years of the Tribunal, resulting in $2.5 billion in awards to U.S. nationals and firms.

The major government-to-government cases involvedinvolve Iranian claims for compensation for hundreds of foreign military sales (FMS) cases that were halted in concert with the rift in U.S.-Iran relations when the Shah's government fell in 1979. In 1991, the George H. W. Bush Administration paid $278 million from the Treasury Department Judgment Fund to settle FMS cases involving weapons Iran had received but which were in the United States undergoing repair and impounded when the Shah fell and were then impounded.

On January 17, 2016 (the day after the JCPOA took effect), the United States announced it had settled with Iran for FMS cases involving weaponry the Shah's government was paying for but that was not completed and delivered to Iran when the Shah fell. Iran deposited itson additional FMS cases that were frozen when the Shah's government fell. Iran had been depositing its FMS payments into a DoD-managed "Iran FMS Trust Fund," and, after 1990, the Fund had a balance of about $400 million. In 1990, $200 million was paid from the Fund to Iran to settle some FMS cases. Under the 2016 settlement, the United States sent Iran the $400 million balance in the Fund, plus $1.3 billion in accrued interest, paid from the Department of the Treasury's "Judgment Fund." In order not to violate U.S. regulations barring direct U.S. dollar transfers to Iranian banks, the funds were remitted to Iran in late January andby early February 2016 in foreign hard currency from the central banks of the Netherlands and of Switzerland. Some remaining claims involving the FMS program with Iran remain under arbitration at the Tribunal.

Other Iranian Assets Frozen

Iranian assets in the United States areremain blocked under several provisions, including Executive Order 13599 of February 2010. The United States did not unblock any of these assets as a consequence of the JCPOAJCPOA did not commit the United States to release any of these assets.

- About $1.9 billion in blocked Iranian assets are bonds belonging to Iran's Central Bank,

frozenin a Citibank account in New York belonging to Clearstream, a Luxembourg-based securities firm, in 2008. The funds were blocked on the grounds that. In 2008, Clearstreamhadallegedly improperly allowed those funds to access the U.S. financial system.AnotherClearstream transferred $1.67 billion in principal and interest paymentson that account were moved to Luxembourg and are not blockedto its accounts in Luxembourg and those proceeds have been deemed by Luxembourg courts as outside U.S. jurisdiction. - About $50 million of Iran's assets frozen in the United States consists of Iranian diplomatic property and accounts, including the former Iranian embassy in Washington, DC, and 10 other properties in several states, and related accounts.

21 - Among other frozen Iranian assets are real estate holdings of the Assa Company, a UK-chartered entity, which allegedly was maintaining the interests of Iran's Bank Melli in a 36-story office building in New York City and several other properties around the United States (in Texas, California, Virginia, Maryland, and other parts of New York City). An Iranian foundation, the Alavi Foundation, allegedly is an investor in the properties. The U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York blocked these properties in 2009. The Department of the Treasury report avoids valuing real estate holdings

, but public sources assess these blocked real estate assets at nearly $1 billion. In June 2017, litigation won the U.S. government. In June 2017, the United States won control over the New York City office building through litigation.

Use of Iranian Assets to Compensate U.S. Victims of Iranian Terrorism

There are a total of about $462

Nearly $50 billion in court awards that have been made to victims of Iranian terrorism. These include the families of the 241 U.S. soldiers killed in the October 23, 1983, bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut. U.S. funds equivalent to the $400 million balance in the DOD account (see above) have been used to pay a small portion of these judgments. The Algiers Accords apparently precluded compensation for the 52 U.S. diplomats held hostage by Iran from November 1979 until January 1981. The FY2016 Consolidated Appropriation (Section 404 of P.L. 114-113) set up a mechanism for paying damages to the U.S. embassy hostages and other victims of state-sponsoredIranian terrorism using settlement payments paid by various banks for concealing Iran-related transactions, and proceeds from other Iranian frozen assets.

In April 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court determined the Central Bank assets, discussed above, could be used to pay the terrorism judgments, and the proceeds from the sale of the frozen real estate assets mentioned above will likely be distributed to victims of Iranian terrorism as well.3 On the other hand, in March 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that U.S. victims of an Iran-sponsored terrorist attack could not seize a collection of Persian antiquities on loan to a University of Chicago museum to satisfy a court judgment against Iran.

Other past financial disputes include the errant U.S. shoot-down on July 3, 1988, of an Iranian Airbus passenger jet (Iran Air flight 655), for which the United States paid Iran $61.8 million in compensation ($300,000 per wage-earning victim, $150,000 per non-wage earner) for the 248 Iranians killed. The United States did not compensate Iran for the airplane itself, although officials involved in the negotiations told CRS in November 2012 that the United States later arranged to provide a substitute used aircraft to Iran.

For more detail on the use of Iranian assets to compensate victims of Iranian terrorism, see CRS Report RL31258, Suits Against Terrorist States by Victims of Terrorism, by Jennifer K. Elsea and CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10104, It Belongs in a Museum: Sovereign Immunity Shields Iranian Antiquities Even When It Does Not Protect Iran, by Stephen P. Mulligan.

Executive Order 13599 Impounding Iran-Owned Assets

Post-JCPOA Status: Still in Effect

Executive Order 13599, issued by President Obama on February 5, 2012, directs the blocking of U.S.-based assets of entities determined to be "owned or controlled by the Iranian government." The order was issued to implement Section 1245 of the FY2012 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 112-81) that imposed secondary U.S. sanctions on Iran's Central Bank. The order requires that U.S. banks block any U.S.-based assets of the Central Bank of Iran, or of any Iranian government-controlled entity, be blocked by U.S. banks. The order goes beyond the regulations issued pursuant to the 1995 imposition of the U.S. trade ban with Iran, in which U.S. banks are required to refuse such transactions but to return funds to Iran. Even before the issuance of the order, and in order to implement the ban on U.S. trade with Iran (see below) successive Administrations had designated many entities as "owned or controlled by the Government of Iran."

Numerous designations have been made under Executive Order 13599, including the June 4, 2013, naming of 38 entities (mostly oil, petrochemical, and investment companies) that are components of an Iranian entity called the "Execution of Imam Khomeini's Order" (EIKO).4 EIKO was characterized by the3 The Department of the Treasury characterizes EIKO as an Iranian leadership entity that controls "massive off-the-books investments."

Implementation of the JCPOA and U.S. Withdrawal from the JCPOA. To implement the JCPOA, many 13599-designated entities (in JCPOA "Attachment 3") were "delisted" from U.S. secondary sanctions (no longer considered "Specially Designated Nationals," SDNs), and referred to as "designees blocked solely pursuant to E.O 13599."54 That characterization permitted foreign entities to conduct transactions with the listed entities without U.S. sanctions penalty but continued to bar U.S. persons (or foreign entities owned or controlled by a U.S. person) from conducting transactions with these entities. In concert with the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, virtually all of the 13599-designated entities that were delisted as SDNs were relisted as SDNs on November 5, 2018.65

Civilian Nuclear Entity Exception. TheWhen the Trump Administration reinstated sanctions, the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI), and 23 of its subsidiaries, were relisted under E.O. 13599 but they were not relisted as entities . However, the Administration did not relist these entities as subject to secondary sanctions (SDNs) under E.O. 13382. This listing decision was made, in order to facilitate continued IAEA and EU and other country engagementinternational involvement with Iran's civilian nuclear program permitted under the JCPOA.76 The May 2019 ending of twosome waivers for nuclear technical assistance to Iran again modified this stance to prohibitprohibits work with some AEOI entities.

Sanctions for Iran's Support for Armed Factions and Terrorist Groups

Most of the U.S.-Iran hostage crisis sanctions were lifted upon release of the hostages in 1981. The United States began imposing sanctions against Iran again in the mid-1980s for itsAfter about five years during which no U.S. sanctions were imposed on Iran, the United States imposed sanctions for Iran's support for regional groups committing acts of terrorism. The Secretary of State designated Iran a "state sponsor of terrorism" on January 23, 1984, following the October 23, 1983, bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks in Lebanon by elements that later established Lebanese Hezbollah. This designation triggers substantial sanctions. on any nation so designated.

None of the laws or executive ordersorders in this section were waived or revoked to implement the JCPOA. No, and no entities discussed in this section were "delisted" from sanctions under the JCPOA..

Sanctions Triggered by Terrorism List Designation

The U.S. naming of Iran as a "state sponsor of terrorism"—commonly referred to as Iran's inclusion on the U.S. "terrorism list"—triggers several sanctions. The designation is made under the authority of Section 6(j) of the Export Administration Act of 1979 (P.L. 96-72, as amended), sanctioning countries determined to have provided repeated support for acts of international terrorism. The sanctions triggered by the designation are as follows:

- Restrictions on sales of U.S. dual use items. The Export Administration Act, as superseded by the Export Control Reform Act of 2018 (in P.L. 115-232), requires

there bea presumption of denial of any license applications to sell dual use items to Iran. The restrictions are enforced through Export Administration Regulations (EARs) administered by the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) of the Commerce Department. - Ban on direct U.S. financial assistance and arms sales to Iran. Section 620A of the Foreign Assistance Act, FAA (P.L. 87-95) and Section 40 of the Arms Export Control Act (P.L. 95-92, as amended), respectively, bar any U.S. foreign assistance (U.S. government loans, credits, credit guarantees, and Ex-Im Bank loan guarantees) to terrorism list countries. Successive foreign aid appropriations laws since the late 1980s have banned direct assistance to Iran, and with no waiver provisions. The FY2012 foreign operations appropriation (Section 7041(c)(2) of P.L. 112-74) banned the Ex-Im Bank from using funds appropriated in that act to finance any entity sanctioned under the Iran Sanctions Act.

- Requirement to oppose multilateral lending. U.S. officials are required to

vote againstuse the country's "voice and vote" to oppose multilateral lending to any terrorism list country by Section 1621 of the International Financial Institutions Act (P.L. 95-118, as amended [added by Section 327 of the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-132)]).Waiver authority is providedThe law provides waiver authority, for example to support an international loan to Iran in humanitarian circumstances. - Withholding of U.S. foreign assistance to countries that assist or sell arms to terrorism list countries. Under Sections 620G and 620H of the Foreign Assistance Act (FAA), as added by Sections 325 and 326 of the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-132), the President is required to withhold foreign aid from any country that aids or sells arms to a terrorism list country. Waiver authority is provided. Section 321 of

that actP.L. 104-132 makes it a crime for a U.S. person to conductfinancialtransactions with terrorism list governments. - Withholding of U.S. Aid to Organizations That Assist Iran. Section 307 of the FAA (added in 1985) names Iran as unable to benefit from U.S. contributions to international organizations, and require proportionate cuts if these institutions work in Iran. For example, if an international organization spends 3% of its budget for programs in Iran, then the United States is required to withhold 3% of its contribution to that international organization. No waiver option is provided

for.

Exception for U.S. Humanitarian Aid

The terrorism list designation, and other U.S. sanctions laws barring assistance to Iran, do not bar U.S. disaster aid. The United States donated $125,000, through relief agencies, to help victims of two earthquakes in Iran (February and Mayin 1997); $350,000 worth of aid to the victims of a June 22, 2002, earthquake; and $5.7 million in assistance for victims of the December 2003 earthquake in Bam, Iran, which killed 40,000. The U.S. military flew 68,000 kilograms of supplies to Bam.

|

Requirements for Removal from Terrorism List Terminating the sanctions triggered by Iran's terrorism list designation would require Iran's removal from the terrorism list. The Arms Export Control Act spells out two different requirements for a President to remove a country from the list, depending on whether the country's regime has changed. If the country's regime has changed: the President can remove a country from the list immediately by certifying that regime change in a report to Congress. If the country's regime has not changed: the President must report to Congress 45 days in advance of the effective date of removal. The President must certify that (1) the country has not supported international terrorism within the preceding six months, and (2) the country has provided assurances it will not do so in the future. In this latter circumstance, Congress has the opportunity to block the removal by enacting a joint resolution to that effect. The President has the option of vetoing the joint resolution, and blocking the removal |

Sanctions on States "Not Cooperating" Against Terrorism

Section 40A to the Arms Export Control Act (added by Section 330 of the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (P.L. 104-132)) added a Section 40A to the Arms Export Control Act that prohibits the sale or licensing of U.S. defense articles and services to any country designated (by each May 15) as "not cooperating fully with U.S. anti-terrorism efforts." The President can waive the provision upon determinationdetermining that a defense sale to a designated country is "important to the national interests" of the United States.

Every May since the enactment of this lawyear since enactment, Iran has been designated as a country that is "not fully cooperating" with U.S. antiterrorism efforts. However, the effect of the designation is largely mooted by the many other authoritiesprovision is largely redundant with other laws that prohibit U.S. defense sales to Iran.

Executive Order 13224 Sanctioning Terrorism-Supporting Entities

Executive Order 13324 (September 23, 2001) mandates the freezing of the U.S.-based assets of, and a ban on U.S. transactions with, entities determined by the Administration to be supporting international terrorism. ThisThe order was issued two weeks after the September 11, 2001, attacks on the United States, under the authority of the IEEPA, the National Emergencies Act, the U.N. Participation Act of 1945, and Section 301 of the U.S. Code, initially targeting Al Qaeda.

On September 10, 2019, the Administration amended E.O. 13224. A major amendment was to authorize the barring from the U.S. financial system any foreign bank determined to have "conducted or facilitated any significant transaction" with any person or entity designated under the order.8

Use of the Order to Target Iranian Arms Exports

E.O. 13224 is not specific to Iran and does not explicitly target Iranian arms exports to movements, governments, or groups in the Middle East region. However, successive Administrations have used the order—and the orders discussed immediately below—to sanction such Iranian activity by designating persons or entities that are involved in the delivery or receipt of such weapons shipments. Some persons and entities that have been sanctioned for such activity have been cited for supporting groups such as the Afghan Taliban organization and the Houthi rebels in Yemen, which are not named as terrorist groups by the United States.

Application of CAATSA7

Application by CAATSA of E.O. 13224 to the Revolutionary Guard

Section 105 of the Countering America's Adversaries through Sanctions Act (CAATSA, P.L. 115-44, August 2, 2017), mandates the imposition of E.O. 13324 penalties on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)IRGC and its officials, agents, and affiliates by October 30, 2017 (90 days after enactment). The Treasury Department made the designation of the IRGC as a terrorism-supporting entity under that E.O. E.O. 13224 on October 13, 2017.

Implementation of E.O. 13224

No entities designated under E.O. 13224 were delisted to implement the JCPOAE.O. 13224 is not specific to Iran. Successive Administrations have used the Order extensively to sanction persons or entities that are involved in Iranian weapons shipments. Numerous Iran-related entities, including members of Iran-allied organizations such as Lebanese Hezbollah and several Iraqi Shia militias, have been designated under E.O. 13224, as shown in the tables later in the report. Some persons and entities that have been sanctioned for such activity have been cited for supporting groups which are not named as terrorist groups by the United States, such as the Afghan Taliban organization and the Houthi rebels in Yemen. The Trump Administration has used the Order to sanction Iranian economic entities that furnish funds for the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and its regional activities. No entities designated under E.O. 13224 were delisted to implement the JCPOA. E.O. 13224, as shown in the tables later in the report.

Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) Designations

Sanctions similar to those of E.O. 13224 are imposed on Iranian and Iran-linked entities through the State Department authority under Section 219 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8.U.S.C. 1189) to designate an entity as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO). In addition to the sanctions of E.O. 13224, any U.S. person (or person under U.S. jurisdiction) who "knowingly provides material support or resources to an FTO, or attempts or conspires to do so" is subject to fine or up to 20 years in prison. A bank that commits such a violation is subject to fines.

Implementation: The following organizations have been designated as FTOs for acts of terrorism on behalf of Iran or are organizations assessed as funded and supported by Iran:

- Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Designated April 8, 2019. On April 22, 2019, the State Department issued guidelines for implementing the IRGC FTO designation, indicating that it would not penalize routine diplomatic or humanitarian-related dealings with the IRGC by U.S. partner countries or nongovernmental entities.

98 See CRS Insight IN11093, Iran's Revolutionary Guard Named a Terrorist Organization, by Kenneth Katzman. - Lebanese Hezbollah.

- Kata'ib Hezbollah (KAH). Iran-backed Iraqi Shi'a militia.

- Asa'ib Ahl Al Haq (AAH). Iran-backed Iraqi Shi'a militia (designated Jan. 3, 2020)

- Hamas. Sunni, Islamist Palestinian organization that essentially controls the Gaza Strip.

- Palestine Islamic Jihad. Small Sunni Islamist Palestinian militant group.

- Al Aqsa Martyr's Brigade. Secular Palestinian militant group.

- Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC). Leftwing secular Palestinian group based mainly in Syria.

- Al Ashtar Brigades. Bahrain militant opposition group.

Other Sanctions on Iran's "Malign" Regional Activities

Some sanctions have been imposed to try to curtail Iran's destabilizing influence in the region.

Executive Order 13438 on Threats to Iraq's Stability

- Issued on July 7, 2007, the order blocks U.S.-based property of persons who are determined by the Administration to "have committed, or pose a significant risk of committing" acts of violence that threaten the peace and stability of Iraq, or undermine efforts to promote economic reconstruction or political reform in Iraq. The order extends to persons designated as materially assisting such designees. The order was clearly directed at Iran for its provision of arms or funds to Shiite militias there. Persons sanctioned under the order include IRGC-Qods Force officers, Iraqi Shiite militia-linked figures, and other entities. Some of these sanctioned entities worked to defeat the Islamic State in Iraq and are in prominent roles in Iraq's parliament and political structure.

Executive Order 13572 on Repression of the Syrian People.

- Issued on April 29, 2011, the order blocks the U.S.-based property of persons determined to be responsible for human rights abuses and repression of the Syrian people. The IRGC-Qods Force (IRGC-QF), IRGC-QF commanders, and others are sanctioned under this order.

The Hizballah International Financing Prevention Act (P.L. 114-102) and Hizballah International Financing Prevention Amendments Act of 2018 (S. 1595, P.L. 115-272).

- The latter act was signed by President Trump on October 23, 2018—the 25th anniversary of the Marine barracks bombing in Beirut. The original law, modeled on the 2010 Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act ("CISADA," see below), excludes from the U.S. financial system any bank that conducts transactions with Hezbollah or its affiliates or partners. The

more recent law expands the authority of the original law by authorizing2018 amendments expand also authorize the blocking of U.S.-based property of and U.S. transactions with any "agency or instrumentality of a foreign state" that conducts joint operations with or provides financing or arms to Lebanese Hezbollah. These latter provisions clearly refer to Iran, but are largely redundant with other sanctions on Iran.

Ban on U.S. Trade and Investment with Iran

Status: Trade ban eased for JCPOA, but back in full effect on August 6, 2018

In 1995, the Clinton Administration expanded U.S. sanctions against Iran by issuing Executive Order 12959 (May 6, 1995) banning U.S. trade with and investment in Iran. The order was issued primarily under the authority primarily of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA, 50 U.S.C. 1701 et seq.),109 which gives the President wide powers to regulate commerce with a foreign country when a "state of emergency" is declared in relations with that country. E.O. 12959 superseded and broadened Executive Order 12957, which was issued two months earlier (March 15, 1995) barringand barred U.S. investment in Iran's energy sector, which. The March 1995 order accompanied President Clinton's declaration of a "state of emergency" with respect to Iran. Subsequently, E.O 13059 (August 19, 1997) added a prohibition on U.S. companies' knowingly exporting goods to a third country for incorporation into products destined for Iran. Each March since 1995, the U.S. AdministrationAdministration in power has renewed the "state of emergency" with respect to Iran. IEEPA gives the President the authority to alter regulations to license transactions with Iran—regulations enumerated in Section 560 of the Code of Federal Regulations (Iranian Transactions Regulations, ITRs).

Section 103 of the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act of 2010 (CISADA, P.L. 111-195) codified the trade ban and reinstated the full ban on imports that had earlier been relaxed by April 2000 regulations. That relaxation allowed importation into the United States of Iranian nuts, fruit products (such as pomegranate juice), carpets, and caviar. U.S. imports from Iran after that time were negligible.11 10

Section 101 of the Iran Freedom Support Act (P.L. 109-293) separately codified the ban on U.S. investment in Iran, but gives the President the authority to terminate this sanction with presidential notification to Congress of such a decision 15 days in advance (or 3 days in advance if there are "exigent circumstances").

JCPOA-Related Easing and Subsequent Reversal

In accordance with U.S. commitments under the JCPOA, the ITRs were relaxed to allow U.S. importation of the Iranian luxury goods discussed above (carpets, caviar, nuts, etc.), but not to permit general U.S.-Iran trade. U.S. regulations were also altered to permit the sale of commercial aircraft to Iranian airlines that are not designated for sanctions. The modifications were made in the Departments of State and of the Treasury guidance issued on Implementation Day and since.12non-sanctioned Iranian airlines.11 In concert with the May 8, 2018, U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, the easing of the regulations to allow for importation of Iranian carpets and other luxury goods was reversed on August 6, 2018.

What U.S.-Iran Trade Is Allowed or Prohibited?

The following provisions apply to the U.S. trade ban on Iran as specified in regulations (Iran Transaction Regulations, ITRs) writtenformulated pursuant to the executive orders and laws discussed above and enumerated in. The regulations are administered by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the Department of the Treasury.

- Oil Transactions.

AllU.S. transactions with Iran in energy products are banned. The 1995 trade ban (E.O. 12959) expanded a 1987 ban on imports from Iran that was imposed by Executive Order 12613 of October 29, 1987. The earlier import ban, authorized by Section 505 of the International Security and Development Cooperation Act of 1985 (22 U.S.C. 2349aa-9), barred the importation of Iranian oil into the United States but did not ban the trading of Iranian oil overseas. The 1995 ban prohibits that activity explicitly, but provides for U.S. companies to apply for licenses to conduct "swaps" of Caspian Sea oil with Iran. These swaps have been prohibited in practice; a Mobil Corporation application to do so was denied in April 1999, and no applications have been submitted since.The ITRsHowever: the regulations do not ban the importation, from foreign refiners, of gasoline or other energy products in which Iranian oil is mixed with oil from other producers. (The product of a refinery in any country, because such refined oil is considered to be a product of the country wherethat refinery is located, even if some Iran-origin crude oil is present.)it is refined. - Transshipment and Brokering. The ITRs prohibit U.S. transshipment of prohibited goods across Iran, and ban any activities by U.S. persons to broker commercial transactions involving Iran.

- Iranian Luxury Goods. Pursuant to the JCPOA, Iranian luxury goods, such as carpets and caviar, could be imported into the United States after January 2016.

ThisBut, this prohibition went back into effect on August 6, 2018. - Shipping Insurance. Obtaining external shipping insurance facilitates Iran's exports

, including oil. A pool of 13 major insurance organizations, called the International Group of P & I (Property and Indemnity) Clubs, dominates the shipping insurance industry and is based in New York. The U.S.presencelocation of this pool renders it subject to the U.S. trade ban,which complicatedthus complicating Iran's ability to obtain reinsurance for Iran's shipping afterImplementation Day. On January 16, 2016, in concert with implementation of the JCPOA, the Obama Administration issued waivers of Sections 212 and 213 of the ITRSHRA to allow numerous suchthe January 16, 2016 start of JCPOA implementation ("Implementation Day"). During the U.S. implementation of the JCPOA, waivers of Sections 212 and 213 of the Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act (ITRSHRA) were issued to enable numerous insurers to give Iranian ships insurance.1312 This waiver ended on August 6, 2018. - Civilian Airline Sales. The ITRs have always permitted the licensing of goods related to the safe operation of civilian aircraft for sale to Iran (§560.528 of Title 31, C.F.R.), and spare parts sales have always been licensed periodically. However, from June 2011 until

Implementation DayJCPOA implementation, Iran's largest state-owned airline, Iran Air, was sanctioned under Executive Order 13382(see below), rendering licensing of parts or repairs for that airline impermissible. Several, and several other Iranian airlines were sanctioned under that order and Executive Order 13224. In accordance with the JCPOA, the United States relaxed restrictionsonto allow for the sale to Iran of finished commercial aircraft, including to Iran Air, which was "delisted" from sanctions.1413 A March 2016 general licenseallowed for U.S. aircraft and parts suppliers to negotiate sales with Iranian airlines that are not sanctioned, and Boeing and Airbuswas issued to permit those sales, and Boeing and Airbus, as well as other manufacturers, subsequently concluded major sales toIran Air. PreexistingIranian airlines. Pre-existing licensing restrictions went back into effect on August 6, 2018, and the Boeing and Airbus licenses to sell aircraft to Iran were revoked. Sales of some aircraft spare parts ("dual use items") to Iran also require a waiver of the relevant provision of the Iran-Iraq Arms Non-Proliferation Act, discussed below. In April 2019, OFAC granted a license for Franco-Italian aircraft maker ATR to supply spare parts (with U.S. content) to the ATR aircraft used by Iran.1514 - Personal Communications, Remittances, and Publishing. The ITRs permit personal communications (phone calls, emails) between the United States and Iran, personal remittances to Iran, and Americans to engage in publishing activities with entities in Iran (and Cuba and Sudan).

- Information Technology Equipment. CISADA exempts from the U.S. ban on exports to Iran information technology to support personal communications among the Iranian people and goods for supporting democracy in Iran. In May 2013, OFAC issued a general license for the exportation to Iran of goods (such as cell phones) and services, on a fee basis, that enhance the ability of the Iranian people to access communication technology.

- Food and Medical Exports. Since April 1999, sales to Iran by U.S. firms of food and medical products have been permitted, subject to OFAC stipulations. In October 2012, OFAC permitted the sale to Iran of specified medical products, such as scalpels, prosthetics, canes, burn dressings, and other products, that could be sold to Iran under "general license" (no specific license application required). This list of general license items list was expanded in 2013 and 2016

1615 to include more sophisticated medical diagnostic machines and other medical equipment. Licenses for exports of medical products not on the general license list are routinely expedited for sale to Iran, according to OFAC. The regulations have a specific definition of "food" that can be licensed for sale to Iran,(which excludes alcohol, cigarettes, gum, or fertilizer).16.17 - Humanitarian and Related Services. Donations by U.S. residents directly to Iranians (such as packages of food, toys, clothes, etc.) are not prohibited

, but donations through relief organizations broadly. However, U.S. relief organizations operating in Iran require those organizations' obtainingto obtain a specific OFAC license to do so. On September 10, 2013,the Department of the Treasury eliminated licensing requirements for relief organizations to (1) provide toGeneral License E was issued that allows relief organizations to conduct activities (up to a value of $500,000 in one year) without a specific licensing requirement, including (1) providing Iran services for health projects, disaster relief, wildlife conservation; (2)conductconducting human rights projects there; or (3)undertakeundertaking activities related to sports matches and events. The amended policy also allowed importation from Iran of services related to sporting activities, including sponsorship of players, coaching, referees, and training. In some cases, such as the earthquake in Bam in 2003 and the 2012 earthquake in northwestern Iran, OFAC has issued blanket temporary general licensing for relief organizations to work in Iran. - Payment Methods, Trade Financing, and Financing Guarantees. U.S. importers are allowed to pay Iranian exporters, but the payment cannot go directly to Iranian banks, and must instead pass through third-country banks.

In accordance with the ITRs' provisions thatRegulations proved for transactions that are incidental to an approved transaction are allowed, meaning that financing ("letter of credit") for approved transactions are normally approved, but no financing by(as long as there is no involvement of an Iranian bankis permitted). Title IX of the Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-387) bans the use of official credit guarantees (such as the Ex-Im Bank) for food and medical sales to Iran and other countries on the U.S. terrorism list, except Cuba, although allowing for a presidential waiver to permit such credit guarantees. The Ex-Im Bank is prohibited from guaranteeing any loans to Iran because of Iran'scontinued inclusionpresence on the terrorism list, and the. The JCPOA did not commit the United States to provide credit guarantees for Iran.

Application to Foreign Subsidiaries of U.S. Firms

The ITRs do not ban subsidiaries of U.S. firms from dealing with Iran, as long as the subsidiary is not "controlled" by the parent company. Most foreign subsidiaries are legally considered foreign persons subject to the laws of the country in which the subsidiaries are incorporated. Section 218 of the Iran Threat Reduction and Syrian Human Rights Act (ITRSHRA, P.L. 112-158) holds "controlled" foreign subsidiaries of U.S. companies to the same standards as U.S. parent firms, defining a controlled subsidiary as (1) one that is more than 50% owned by the U.S. parent; (2) one in which the parent firm holds a majority on the Board of Directors of the subsidiary; or (3) one in which the parent firm directs the operations of the subsidiary. There is no waiver provision.

JCPOA Regulations and Reversal. To implement the JCPOA, the United States licensed "controlled" foreign subsidiaries to conduct transactions with Iran that are permissible under JCPOA (almost all forms of civilian trade). The Obama Administration asserted that the President has authority under IEEPA to license transactions with Iran, the ITRSHRA notwithstanding. This was implemented withimplementation was accomplished in the Treasury Department's issuance of "General License H: Authorizing Certain Transactions Relating to Foreign Entities Owned or Controlled by a United States Person."18 With the Trump Administration reimposition of sanctions, the17 The Obama Administration asserted that the President has authority under IEEPA to license transactions with Iran, the ITRSHRA notwithstanding. The Trump Administration revoked that general license and restore the pre-JCPOA licensing policy ("Statement of Licensing Policy," SLP) returned to pre-JCPOA status on November 56, 2018.

|

Trade Ban Easing and Termination Termination: Section 401 of the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act of 2010 (CISADA, P.L. 111-195) provides for the President to terminate the trade ban if the Administration certifies to Congress that Iran no longer satisfies the requirements to be designated as a state sponsor of terrorism and that Iran has ceased pursuing and has dismantled its nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons and ballistic missiles and related launch technology. Alternatively, the trade ban provision in CISADA could be repealed by congressional action. Waiver Authority: Section 103(b)(vi) of CISADA allows the President to license exports to Iran if he determines that doing so is in the national interest of the United States. There is no similar provision in CISADA to ease the ban on U.S. imports from Iran. |

Sanctions on Iran's Energy Sector

18Status: Energy sanctions waived for JCPOA, back in effect November 56, 2018

In 1996, Congress and the executive branch began a long process of pressuring Iran's vital energy sector in order to deny, with the stated aim of denying Iran the financial resources to support terrorist organizations and other armed factions or to further its nuclear and WMD programs. Iran's oil sector is as old as the petroleum industry itself (early 20th century), and Iran's onshore oil fields are in need of substantial investment. Iran has 136.3 billion barrels of proven oil reserves, the third largest after Saudi Arabia and Canada, and in early November 2019 it announced discovery of the Namavaran oilfield with an estimated 53 billion barrels of crude oil. Iran has large natural gas resources (940 trillion cubic feet), exceeded only by Russia. However, Iran's gas export sector is still emerging—rudimentary and most of Iran's gas is injected into its oil fields to boost their production. The energy sector still generatesIran has, since 2011, reduced its dependence on oil and gas sales, but, prior to the re-imposition of U.S. sanctions, the energy sector was still generating about 20% of Iran's GDP and as much as 30% of government revenue.

The Iran Sanctions Act

This sections includes sanctions triggers under the Act that were added by laws enacted subsequent to the original versionsubsequent laws.

The Iran Sanctions Act (ISA) has been a pivotal component of U.S. sanctions against Iran's energy sector. Since its enactment in 1996, ISA's provisions have been expanded and extended to other Iranian industries. ISA sought to thwart Iran's 1995 opening of the sector to foreign investment in late 1995 through a "buy-back" program in which foreign firms gradually recoup their investments as oil and gas is produced. It was first enacted as the Iran and Libya Sanctions Act (ILSA, P.L. 104-172, signed on August 5, 1996) but was later retitled the Iran Sanctions Act after it terminated with respect to Libya in 2006. ISA was the first major "extra-territorial sanction" on Iran—a sanction that authorizes U.S. penalties against third country firms.

Key Sanctions "Triggers" Under ISA

ISA consists of a number of "triggers"—transactions with Iran that would be considered violations of ISA and could cause a firm or entity to be sanctioned under ISA's provisions. The triggers, as added by amendments over time, are detailed below:

Trigger 1 (Original Trigger): "Investment" To Develop Iran's Oil and Gas Fields

The core trigger of ISA when it was first enacted was a requirement that the President sanction companies (entities, persons) that make an "investment"19 of more than $20 million20 in one year in Iran's energy sector.21 The definition of "investment" in ISA (§14 [9]) includes not only equity and royalty arrangements but any contract that includes "responsibility for the development of petroleum resources" of Iran. The definition includes additions to existing investment (added by P.L. 107-24) and pipelines to or through Iran and contracts to lead the construction, upgrading, or expansions of energy projects (added by CISADA).

Trigger 2: Sales of WMD and Related Technologies, Advanced Conventional Weaponry, and Participation in Uranium Mining Ventures

This provision of ISA was not waived under the JCPOA.

The Iran Freedom Support Act (P.L. 109-293, signed September 30, 2006) added Section 5(b)(1) of ISA, subjecting to ISA sanctions firms or persons determined to have sold to Iran (1) "chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons or related technologies" or (2) "destabilizing numbers and types" of advanced conventional weapons. Sanctions can be applied if the exporter knew (or had cause to know) that the end-user of the item was Iran. The definitions do not specifically include ballistic or cruise missiles, but those weapons could be considered "related technologies" or a "destabilizing type" of advanced conventional weapon.

The Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act (ITRSHRA, P.L. 112-158, signed August 10, 2012) created Section 5(b)(2) of ISA subjecting to sanctions entities determined by the Administration to participate in a joint venture with Iran relating to the mining, production, or transportation of uranium.

Implementation: No ISA sanctions have been imposed on any entities under these provisionsthis provision.

Trigger 3: Sales of Gasoline to Iran

Section 102(a) of the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act of 2010 (CISADA, P.L. 111-195, signed July 1, 2010) amended Section 5 of ISA to exploit Iran's dependency on imported gasoline (40% dependency at that time). It followed legislation such as P.L. 111-85 that prohibited the use of U.S. funds to fill the Strategic Petroleum Reserve with products from firms that sell gasoline to Iran; and P.L. 111-117 that denied Ex-Im Bank credits to any firm that sold gasoline or related equipment to Iran. The section sanctions:

- Sales to Iran of over $1 million worth in a single transaction (or $5 million in multiple transactions a one-year period) of gasoline and related aviation and other fuels. (Fuel oil, a petroleum by-product, is not included in the definition of refined petroleum.)

- Sales to Iran of equipment or services (same dollar threshold as above) which would help Iran make or import gasoline. Examples include equipment and services for Iran's oil refineries or port operations.

Trigger 4: Provision of Equipment or Services for Oil, Gas, and Petrochemicals Production

Section 201 of the Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act of 2012 (ITRSHA, P.L. 112-158, signed August 10, 2012) codified an Executive Order, 13590 (November 21, 2011), by adding Section 5(a)(5 and 6) to ISA sanctioning firms that: Provide

provideto Iran $1 million or more(or $5 million inin a single transaction (or a total of $5 million in multiple transactions in a one-year period) worth of goods or services that Iran could use to maintain or enhance its oil and gas sector. This subjects to sanctions, for example, transactions with Iran by global oil services firms and the sale to Iran of energy industry equipment such as drills, pumps, vacuums, oil rigs, and like equipment.- provide to Iran $250,000 in a single transaction (or $1 million in multiple transactions in a one-year period) worth of goods or services that Iran could use to maintain or expand its production of petrochemical products.22 This provision was not altered by the JPA.

Trigger 5: Transporting Iranian Crude Oil

Section 201 of the ITRSHRA amends ISA by sanctioning entities the Administration determines

- to haveowned a vessel that was used to transport Iranian crude oil. The section also authorizes but does not require the President, subject to regulations, to prohibit a ship from putting to port in the United States for two years, if it is owned by a person sanctioned under this provision (adds Section 5[a][7] to ISA). This sanction does not apply in cases of transporting oil to countries that have received exemptions under P.L. 112-81 (discussed below).

- participated in a joint oil and gas development venture with Iran, outside Iran, if that venture was established after January 1, 2002. The effective date exempts energy ventures in the Caspian Sea, such as the Shah Deniz oil field

there(adds Section 5[a][4] to ISA).

Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act (ITRSHRA): ISA sanctions for insuring Iranian oil entities, purchasing Iranian bonds, or engaging in transactionson shipping insurance, Iranian bonds, and dealings with the IRGC

Separate provisions of the ITRSHR Act—which do not amend and were not formally incorporated into ISA—require the application of ISA sanctions (5five out of the 12 sanctions on the ISA sanctions menu) on any entity that

- provides insurance or reinsurance for the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) or the National Iranian Tanker Company (NITC) (Section 212).

- purchases or facilitates the issuance of sovereign debt of the government of Iran, including Iranian government bonds (Section 213).

This sanction went back into effect on August 6, 2018 (90-day wind-down period). - assists or engages in a significant transaction with the IRGC or any of its sanctioned entities or affiliates. (Section 302). This section

of ITRSHRAwas not waived to implement the JCPOA.

Implementation. Section 312 of ITRSHRA required an Administration determination, within 45 days of enactment (by September 24, 2012) whether NIOC and NITC are IRGC agents or affiliates. The determination would subject financial transactions with NIOC and NITC to sanctions under CISADA (prohibition on opening U.S.-based accounts). On September 24, 2012, the Department of the Treasury determined that NIOC and NITC are affiliates of the IRGC. On November 8, 2012, the Department of the Treasury named NIOC as a proliferation entity under Executive Order 13382—a designation that, in accordance with Section 104 of CISADA, bars any foreign bank determined to have dealt directly with NIOC (including with a NIOC bank account in a foreign country) from opening or maintaining a U.S.-based account.

Sanctions on dealings with NIOC and NITC were waived in accordance with the interim nuclear agreement of late 2013. Their designations under Executive Order 13382 were rescinded in accordance with the JCPOA. These entities, but they were "relisted" again on November 5, 2018.

Executive Order 13622/13846: Sanctions on the Purchase of Iranian Crude Oil and Petrochemical Products, and Dealings in Iranian Bank Notes

Status: 13622 (July 30, 2012) Revokedrevoked (by E.O. 13716), January 2016) but was put back into effect by E.O. 13846 of August 6, 2018

Executive Order 13622 (July 30, 2012) imposed specified sanctions on the ISA sanctions menu, and bars banks from the U.S. financial system, for the following activities (E.O. 13622 did not amend ISA itself):

- the purchase of oil, other petroleum, or petrochemical products from Iran.23

The sanction was reinstated by E.O. 13846, and took effect on November 7, 2018. - transactions with the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) or Naftiran Intertrade Company (NICO)

(180-day wind-down period).

E.O. 13622 also blocked U.S.-based property of entities determined to have

- assisted or provided goods or services to NIOC, NICO, the Central Bank of Iran. This sanction was reinstated

by E.O. 13846, effectiveas of November76, 2018. - assisted the government of Iran in the purchase of U.S. bank notes or precious metals, precious stones, or jewels. (The provision for precious stones or jewels was added to this order by E.O. 16345 below.) This sanction was reinstated by E.O. 13846, effective as of August 7, 2018.

E.O. 13622 sanctions do not apply if the parent country of the entity has received an oil importation exception under Section 1245 of P.L. 112-81, discussed below. An exception also is provided for projects that bring gas from Azerbaijan to Europe and Turkey, if such project was initiated prior to the issuance of the order.

Mandate and Time Frame to Investigate ISA Violations

In the original version of ISA, there was no firm requirement, and no time limit, for the Administration to investigate potential violations and determine that a firm has violated ISA's provisions. The Iran Freedom Support Act (P.L. 109-293, signed September 30, 2006) added a provision calling forrecommending, but not requiring, a 180-day time limit for a violation determination.24 CISADA (Section 102[g][5]) mandated that the Administration begin an investigation of potential ISA violations when there is "credible information" about a potential violation, and made mandatory the 180-day time limit for a determination of violation.

The Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act (P.L. 112-158)ITRSHRA defines the "credible information" needed to begin an investigation of a violation to include a corporate announcement or corporate filing to its shareholders that it has undertaken transactions with Iran that are potentially sanctionable under ISA. It also says the President may (not mandatory) use as credible information reports from the Government Accountability Office and the Congressional Research Service. In addition, Section 219 of ITRSHRA requires that an investigation of an ISA violation begin if a company reports in its filings to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) that it has knowingly engaged in activities that would violate ISA (or Section 104 of CISADA or transactions with entities designated under E.O 13224 or 13382, see below).

ISA Sanctions Menu ITRSHRA added several mechanisms for Congress to oversee whether the Administration is investigating ISA violations. Section 223 of that law required a Government Accountability Office report, within 120 days of enactment, and another such report a year later, on companies that have undertaken specified activities with Iran that might constitute violations of ISA. Section 224 amended a reporting requirement in Section 110(b) of CISADA by requiring an Administration report to Congress every 180 days on investment in Iran's energy sector, joint ventures with Iran, and estimates of Iran's imports and exports of petroleum products. ISA Sanctions Menu 1. denial of Export-Import Bank loans, credits, or credit guarantees for U.S. exports to the sanctioned entity (original ISA) 2. denial of licenses for the U.S. export of military or militarily useful technology to the entity (original ISA) 3. denial of U.S. bank loans exceeding $10 million in one year to the entity (original ISA) 4. if the entity is a financial institution, a prohibition on its service as a primary dealer in U.S. government bonds; and/or a prohibition on its serving as a repository for U.S. government funds (each counts as one sanction) (original ISA) 5. prohibition on U.S. government procurement from the entity (original ISA) 6. prohibition on transactions in foreign exchange by the entity (added by CISADA) 7. prohibition on any credit or payments between the entity and any U.S. financial institution (added by CISADA) 8. prohibition of the sanctioned entity from acquiring, holding, using, or trading any U.S.-based property which the sanctioned entity has a (financial) interest in (added by CISADA) 9. restriction on imports from the sanctioned entity, in accordance with the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA; 50 U.S.C. 1701) (original ISA) 10. a ban on a U.S. person from investing in or purchasing significant amounts of equity or debt instruments of a sanctioned person (added by ITRSHRA) 11. exclusion from the United States of corporate officers or controlling shareholders of a sanctioned firm (added by ITRSHRA) 12. imposition of any of the ISA sanctions on principal offices of a sanctioned firm (added by ITRSHRA). Mandatory Sanction: Prohibition on Contracts with the U.S. Government CISADA (§102[b]) added a requirement in ISA that companies, as a condition of obtaining a U.S. government contract, certify to the relevant U.S. government agency that the firm—and any companies it owns or controls—are not violating ISA. Regulations to implement this requirement were issued on September 29, 2010. Executive Order 13574 of May 23, 2011 and E.O. 13628 of October 9, 2012, specify which sanctions are to be imposed. E.O. 13574 stipulated that, when an entity is sanctioned under Section 5 of ISA, the penalties to be imposed are numbers 3, 6, 7, 8, and 9, above. E.O. 13628 updated that specification to also include ISA sanctions numbers 11 and 12. The orders also clarify that it is the responsibility of the Department of the Treasury to implement those ISA sanctions that involve the financial sectors. E.O. 13574 and 13628 were revoked by E.O. 13716 on Implementation Day, in accordance with the JCPOA. They were reinstated, and superseded, by E.O. 13846 of August 6, 2018, which mandated that, when ISA sanctions are to be imposed, that the sanctions include ISA sanctions numbers 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 12. |

Oversight

Several mechanisms for Congress to oversee whether the Administration is investigating ISA violations were added by ITRSHRA. Section 223 of that law required a Government Accountability Office report, within 120 days of enactment, and another such report a year later, on companies that have undertaken specified activities with Iran that might constitute violations of ISA. Section 224 amended a reporting requirement in Section 110(b) of CISADA by requiring an Administration report to Congress every 180 days on investment in Iran's energy sector, joint ventures with Iran, and estimates of Iran's imports and exports of petroleum products. The GAO reports have been issued; there is no information available on whether the required Administration reports have been issued as well.

Interpretations of ISA and Related Laws

The sections below provide information on how some key ISA provisions have been interpreted and implemented.

Application to Energy Pipelines

ISA's definition of "investment" that is subject to sanctions has been consistently interpreted by successive Administrations to include construction of energy pipelines to or through Iran. Such pipelines are deemed to help Iran develop its petroleum (oil and natural gas) sector. This interpretation was reinforced by amendmentsAmendments to ISA in CISADA, which specifically included in the definition of petroleum resources "products used to construct or maintain pipelines used to transport oil or liquefied natural gas." In March 2012, then-Secretary of State Clinton made clearclarified that the Obama Administration interpretsinterpreted the provision to be applicable from the beginning of pipeline construction.25

Application to Crude Oil Purchases/Shipments

ISA does not sanction purchasing crude oil from Iran, but other laws, such as the Iran Freedom and Counterproliferation Act (IFCA, discussed below) and executive orders, do. No U.S. sanction requires any country or person to actually seize, intercept, inspect on the high seas, or impound any Iranian ship suspected of carrying oil or other cargo subject to sanctions.

However, as discussed further elsewhere in this paper, as of below, in August 2019, the Trump Administration has begunbegan using various terrorism-related provisions to sanction some Iranian oil shipments. The Administration has argued that the shipments were organized by and for the benefit of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). On September 4, 2019, the Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) updated its sanctions guidance to state that "bunkering services" (port operational support) for Iranian oil shipments could subject firms and individuals involved in such support to U.S. sanctions.

Application to Purchases from Iran of Natural Gas

ISA and other laws, such as IFCA, exclude from sanction purchases of natural gas from Iran or natural gas transactions with Iran. However, construction of gas pipelines involving Iran is subject to ISA sanctions.

Moreover, sanctions on financial transactions with Iran (see throughout) can impede implementation of purchase agreements for Iranian gas.Exception for Shah Deniz and other Gas Export Projects

The effective dates of U.S. sanctions laws and orders exclude long-standing joint natural gas projects that involve some Iranian firms—particularly the Shah Deniz natural gas field and related pipelines in the Caspian Sea. These projects involve a consortium in which Iran's Naftiran Intertrade Company (NICO) holds a passive 10% share, and in Shah Deniz, which also includes BP, Azerbaijan's natural gas firm SOCAR, Russia's Lukoil, and other firms. NICO was sanctionedis a sanctioned entity under ISA and other provisions (until JCPOA Implementation Day), but an OFAC factsheet of November 28, 2012, stated that the Shah Deniz consortium, as a whole, is not determined to be "a person owned or controlled by" the government of Iran and transactions with the consortium are permissible.

Application to Iranian Liquefied Natural Gas Development

The original version of ISA did not apply to the development by Iran of a liquefied natural gas (LNG) export capability. Iran has no LNG export terminals, in part because the technology for such terminals is patented by U.S. firms and unavailable for sale to Irannot developed an LNG export capability to date. CISADA specifically included LNG in the ISA definition of petroleum resources and therefore made subject to sanctions LNG investment in Iran, and supply of LNG tankers to Iran, and construction of pipelines linking to Iran.

Application to Private Financing but Not Official Credit Guarantee Agencies

The definitions of investment and other activity that can be sanctioned under ISA include financing for investment in Iran's energy sector, or for sales of gasoline and refinery-related equipment and services. Therefore, banks and other financial institutions that assist energy investment and refining and gasoline procurement activities could be sanctioned under ISA.

However, the definitions of financial institutions are interpreted not to apply to official credit guarantee agencies—, such as France's COFACE and Germany's Hermes. These credit guarantee agencies are arms of their parent governments, and ISA does not provide for sanctioning governments or their agencies.

Implementation of Energy-Related Iran Sanctions

Entities sanctioned under the executive orders or laws cited in this section are listed in the tables at the end of this report. As noted, some of the orders cited provide for blocking U.S.-based assets of the entities designated for sanctions. OFAC has not announced the blocking of any U.S.-based property of the sanctioned entities, likely indicating that those entities sanctioned do not have a presence in the United States.

|